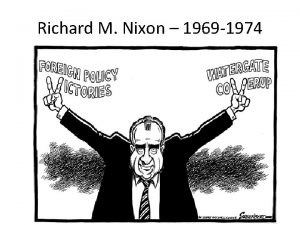

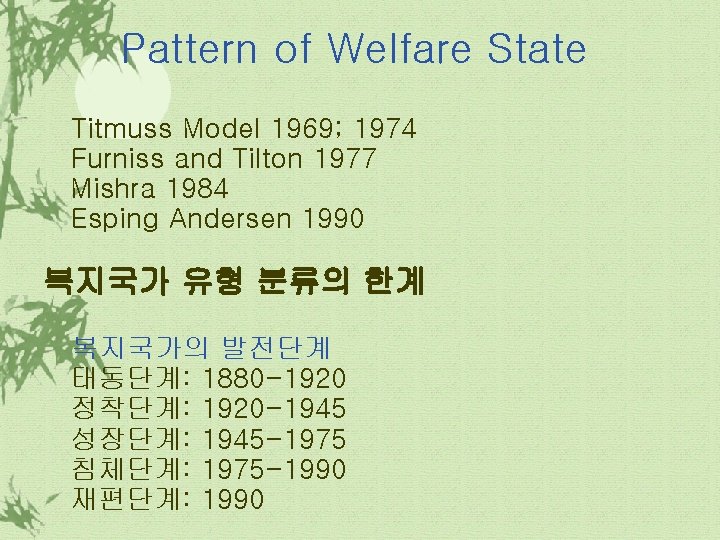

Pattern of Welfare State Titmuss Model 1969 1974

- Slides: 72

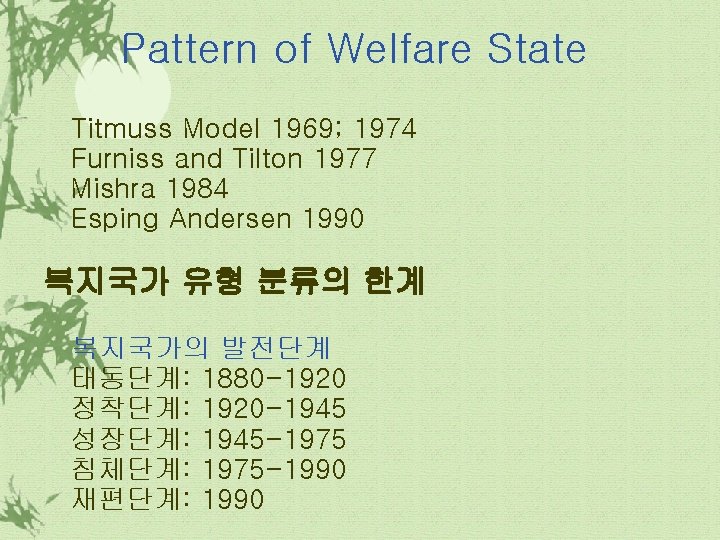

Pattern of Welfare State Titmuss Model 1969; 1974 Furniss and Tilton 1977 Mishra 1984 Esping Andersen 1990 복지국가 유형 분류의 한계 복지국가의 발전단계 태동단계: 1880 -1920 정착단계: 1920 -1945 성장단계: 1945 -1975 침체단계: 1975 -1990 재편단계: 1990

This is a problematic conclusion; the distinctive EAWM is not only related to a regional bloc but is beyond question related to the cultural norm of a ‘Confucianist group’ (Lin, 2001). Although Holliday (2000, p. 706) points out that many studies have focused mainly on the role of the state, neglecting the cultural dimension. Deyo (1992, pp. 289 -90) holds that, with few exceptions, ‘East Asian social policy has been driven primarily by the requirements and outcomes of economic development policy’.

Welfare pluralism The different forms of welfare regime to be found in other countries thus reveal that welfare policies develop in different ways in different social, economic and political contexts. These differences also reveal a varying balance within different regimes between the role of the state in the provision of welfare, for example with public welfare playing a major role in social democratic regimes like Sweden and the private market playing a major role in liberal regimes like the USA. It is not, however, only the balance between the state and the market which varies between different regimes.

In corporatist regimes like Germany, considerable emphasis is placed on the informal role of family structure in providing welfare support, for instance in the care of children or the long-term chronically sick. In other regimes, for example, the ‘welfare societies of some Mediterranean countries like Greece and Spain, many welfare services are provided by voluntary agencies such as church and other religious organisation (Alcock, 2003: pp 15 -16).

In other words, in different welfare states there is a variation between the roles of different sectors in the provision of welfare services. It is important to recognise here that it is not just that the balance between the different sectors varies between different welfare states, or welfare regimes, but also that this balance may vary within any one welfare state over time – especially, of course, if that welfare state is experiencing a move from one regime to another. Indeed, it is primarily upon the balance between the roles of the different sectors of welfare that the nature of the welfare regime in any one country at any one time can be determined.

Criticism of Welfare Pluralism Despite the success of the Fabian tradition of social policy and political reform in establishing state welfare in Western Europe. Despite the criticism of right-wing, left-wing and other critics of the problems resulting from this apparent state monopoly over welfare services, in practice welfare services in this country have always been delivered by a mixture of state, market, voluntary and informal means. Furthermore, the balance of this mixture has changed over time – for instance with the role of the voluntary sector declining in the early part of the twentieth century.

The general point, however, that there has always been a balance between the providers of services – or what some commentators have called a mixed economy of welfare. What is more, criticism of state welfare provision in the last two decades or so, and the attempt by the Conservative government of welfare, have made the importance of the mixed economy of welfare in Western Europe even more clear. The promotion of welfare pluralism does challenge the idea that any one sector should monopolies welfare provision.

Elitism theory Corporatism Theory Marxism Theory

Type of Esping-Andersen 은 decommodification 의 정도, 계층화 (stratification) 유형, 국가와 시 장의 상대적 비중이라는 세가지 기준을 사용 하여 복지국가를 분류 하였다. Liberal welfare State (자유주의 복지국가) Conservative-corporative welfare state (보수적 조합주의 복지국가) Social democratic welfare state (사회민주 주의 복지국가)

In one cluster we find the ‘liberal’ welfare state, in which means-tested assistance, modest universal transfers, or modest social insurance plans predominate. Benefit cater mainly to a clientele of lowincome, usually working-class, state dependents. In this model, the progress of social reform has been severely circumscribed by traditional, liberal work-ethic norms: it is one where the limits of welfare equal that marginal propensity to opt for welfare instead of work. Entitlement rules are therefore strict and often associated with stigma; benefits are typically modest. In turn, the state encourages the market, either passively – by guaranteeing only a minimum or actively –by subsidizing private welfare schemes

The consequence is that this type of regime minimizes decommodificationeffects, effectively contains the realm of social rights, and erects an order of stratification that is a blend of a relative equality of poverty among state-welfare recipients, market-differentiated welfare among the majorities, and a classpolitical dualism between the two. The archetypical examples of this model are the USA, Canada and Austria.

A second Type of Corporatist Regime (Conservative welfare state) A second regime type clusters nations such as Austria, France, Germany, and Italy. Here, the historical corporatist-statist legacy was upgrade to cater to the new ‘post-industrial class structure. In these, conservative and strongly ‘corporatist's welfare states, the liberal obsession with market efficiency and commodification was never preeminent and, such as the granting of social rights was hardly ever a seriously contested issue. What predominated was the preservative status differentials; right, therefore, were attached to class and status. On the other hand, the state; s emphasis on upholding status differences means that its redistribute impact is negligible.

But the corporatist regimes are also typically shaped by the Church, and hence strongly committed to the preservation of traditional family-hood. Social insurance typically excludes non-working wives, and family benefits encourage motherhood. Day car, and similar family services, are conspicuously underdeveloped; the principle of ‘subsidiarity’ service to emphasize that the state will only interfere when the family’s serves to serve its members is exhausted.

The third type of Social Democratic Regime The third, and clearly smallest, regimecluster is composed of those countries in which the principles of universalism and decommodification of social rights were extended also to the new middle classes. We may call it the ‘social democratic’ regime-type since, in these nations, social democracy was clearly the dominant force behind social reform.

Rather than tolerate a dualism between state and market, between working class and middle class, the social democrats pursued a welfare state that would promote an equality of the highest standards, not an equality of minimal needs as was pursued elsewhere. This implied, first that services and benefits be upgrade to levels commensurate with even the most discriminating tastes of the new middle classes; and second, that equality of rights enjoyed by the better-off.

The social democratic regime’s policy of emancipation addresses both the market and the traditional family. In contrast to the corporatist-subsidiarity model, the principle is not to wait until the family’s capacity to aid is exhausted, but to preemptively socialize the costs of family-hood. The ideal is not to maximize dependence on the family, but capacities for individual independence.

이데올로기에 따른 사회복지정책의 내용 Ideologies of Welfare The New Right The Middle Way Democratic Socialism Marxism Feminism Greenism

The Ideology The concept of ideology is one of the most important in social science. However, it is also one of the most contested-and one of the most issued and misunderstood. For instance, ideology is sometimes taken to mean the adoption of a false or inaccurate perception of the real world; this is then contrasted with the correct perspective which is supposedly provided by scientific inquiry.

This is not the sense in which ideology is normally understood in social policy debate. Alcock (2005) use ideology more broadly as a concept that refers to the systems of beliefs within which all individuals perceive all social phenomena. In this usage no one system of beliefs is more correct, or more privileged, than any other.

He uses that shape and structure the way we see the world, and make judgements about it. And, of cause, each individual’s ideological perspective is different and unique. We do not agree with one another about everything. Indeed, it our disagreements and differences that make debate and development both desirable and possible. If we were all the same it would not only be a dull world –in terms of social developments, it would be dead one. Thus individual ideologies differ, and they are source of debate-and conflict.

Individual ideologies are also both critical and perspective-we know what is wrong with what we see, and we know what should be done about it. As a result of this they are therefore partial and value laden – we do not know or understand everything but we do know what we like and do not like. Ideological perspectives therefore condition the way in which all of us perspective the world in which we live, and they do so in a way that leaves all of us with a more or less restricted and biased perspective on it.

Individual ideologies are constructed within wider ideological perspectives in which views are shared and debated, and within which shared views held and disseminated (Alcock, 2005). It is important to recognise here, however, that ideological perspectives not only determine which policies we propose to develop or support but also influence how we view, and judge, policy developments that have already taken place. Take, for example, the introduction of the right of all tenants to buy their council houses by the Conservative government in 1980.

1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975

1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978

1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 Componentele pistolului

Componentele pistolului Pros and cons of welfare state

Pros and cons of welfare state Kilham and mann 1974

Kilham and mann 1974 Brenner 1974

Brenner 1974 National policy and legislation

National policy and legislation Body art marina abramovic

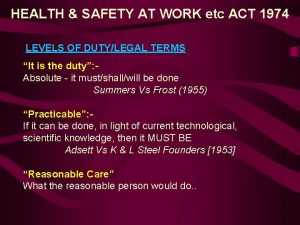

Body art marina abramovic Health and safety at work act 1974 section 2

Health and safety at work act 1974 section 2 Hasawa

Hasawa 1974-1942

1974-1942 Buaful v construction pioneer

Buaful v construction pioneer Herbert freudenberger burnout 1974

Herbert freudenberger burnout 1974 Voleibol

Voleibol Geoffrey leech 7 types of meaning

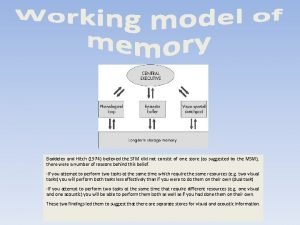

Geoffrey leech 7 types of meaning Baddeley and hitch 1974

Baddeley and hitch 1974 Loftus and palmer (1974)

Loftus and palmer (1974) Family educational rights and privacy act 1974

Family educational rights and privacy act 1974 Dutton aron 1974

Dutton aron 1974 Cubo de las 36 caras de morrill oetting y hurst (1974)

Cubo de las 36 caras de morrill oetting y hurst (1974) Elizabeth noelle neumann

Elizabeth noelle neumann Perintah am bab b elaun lebih masa

Perintah am bab b elaun lebih masa Section 33 hswa

Section 33 hswa Family educational rights and privacy act of 1974

Family educational rights and privacy act of 1974 Baddley and hitch

Baddley and hitch Rci act 1992

Rci act 1992 Perintah am bab f tahun 1974

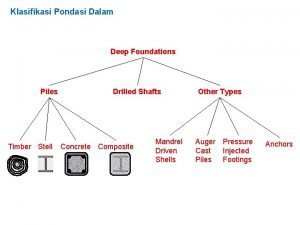

Perintah am bab f tahun 1974 Klasifikasi pondasi

Klasifikasi pondasi The longest yard cheerleaders 1974

The longest yard cheerleaders 1974 25 abril 1974

25 abril 1974 Smith 1974

Smith 1974 Haswa

Haswa Hswa section 7

Hswa section 7 Walter gropius (1883-1969)

Walter gropius (1883-1969) 1969 white paper

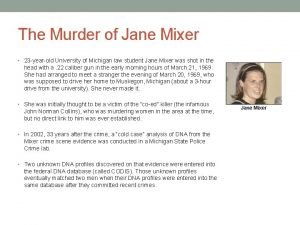

1969 white paper Jane mixer killer

Jane mixer killer Sistemas basados en unix

Sistemas basados en unix Ffa 1969

Ffa 1969 Dr. charles homer lane

Dr. charles homer lane Beckhard 1969

Beckhard 1969 Theodorson and theodorson 1969 communication

Theodorson and theodorson 1969 communication Rip curl 1969

Rip curl 1969 Bipartição

Bipartição Reicher 1969

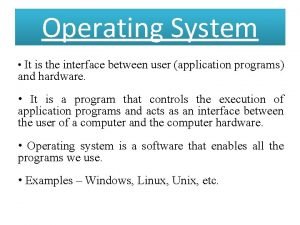

Reicher 1969 Which operating system is a multiuser os developed in 1969

Which operating system is a multiuser os developed in 1969 Fc united of manchester wiki

Fc united of manchester wiki 2012-1969

2012-1969 Cac/rcp 1-1969 rev 5 2020

Cac/rcp 1-1969 rev 5 2020 Grażyna skrzypaczka zm.1969 r

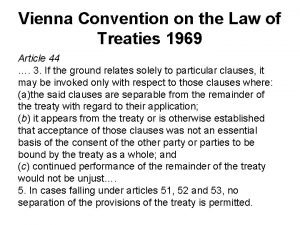

Grażyna skrzypaczka zm.1969 r Konvensi wina 1969

Konvensi wina 1969 What are the seven parts of the ffa emblem

What are the seven parts of the ffa emblem Vienna convention

Vienna convention July 1969

July 1969 Natura fundada em

Natura fundada em 24 juni 1969

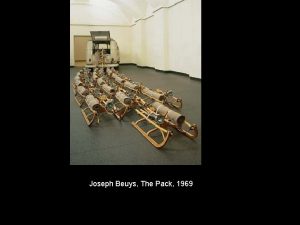

24 juni 1969 Joseph beuys auschwitz demonstration

Joseph beuys auschwitz demonstration Lyndon b johnson 1969

Lyndon b johnson 1969 2005 - 1969

2005 - 1969 Ihr 1969

Ihr 1969 Oms

Oms Nariman committee 1969

Nariman committee 1969 Brown v board of education of topeka

Brown v board of education of topeka The cold war heats up: 1945 - 1969

The cold war heats up: 1945 - 1969 Arpanet

Arpanet Copyright regulations 1969

Copyright regulations 1969 Vanavar bush

Vanavar bush Gardner and gardner 1969

Gardner and gardner 1969 Chapter 26 section 2 the cold war heats up

Chapter 26 section 2 the cold war heats up What is industrial achievement-performance model

What is industrial achievement-performance model California child welfare core practice model

California child welfare core practice model Spiral pattern with 2 deltals and many forms of pattern.

Spiral pattern with 2 deltals and many forms of pattern. Pattern and pattern classes in image processing

Pattern and pattern classes in image processing L

L