pain Department of Oral Medicine Faculty of Dentistry

- Slides: 35

pain Department of Oral Medicine, Faculty of Dentistry, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Pain • Pain, as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain, is "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. “ • Many different adjectives such as aching, throbbing, stabbing, pounding and burning have been used to describe a pain sensation. • "If it isn't unpleasant, it isn't pain. "

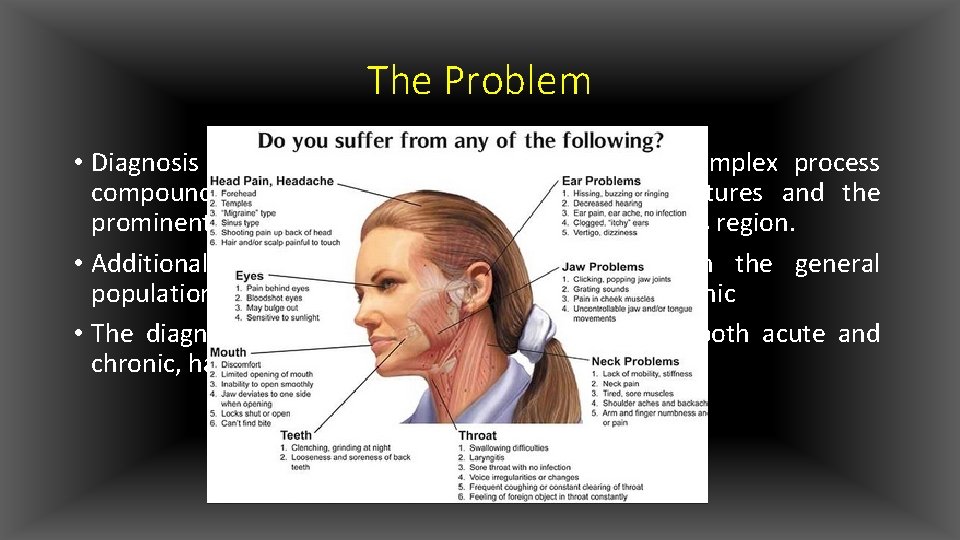

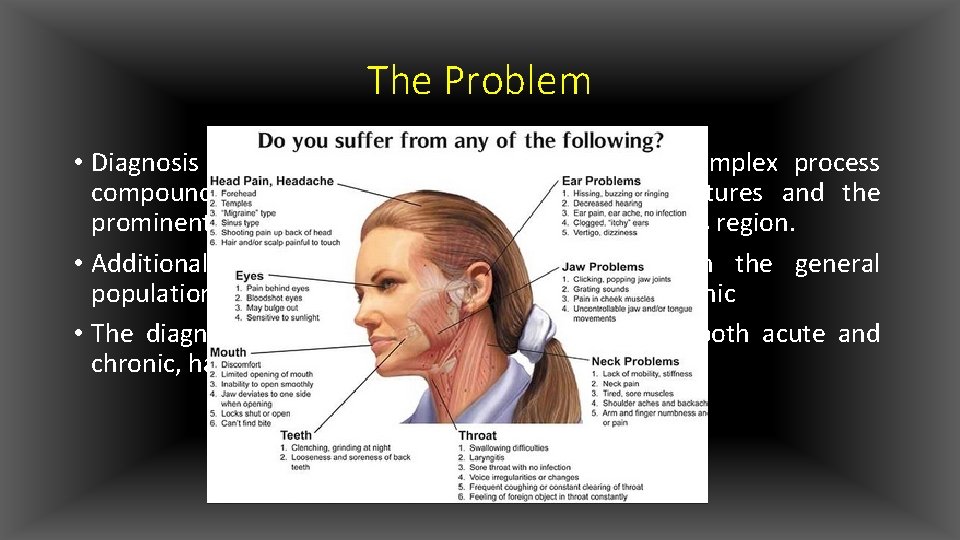

The Problem • Diagnosis and treatment of orofacial pain is a complex process compounded by the density of anatomical structures and the prominent psychological significance attributed to this region. • Additionally orofacial pain is quite prevalent in the general population: around 17– 26%, of which 7– 11% are chronic • The diagnosis and management of orofacial pain, both acute and chronic, have become important subjects in dentistry

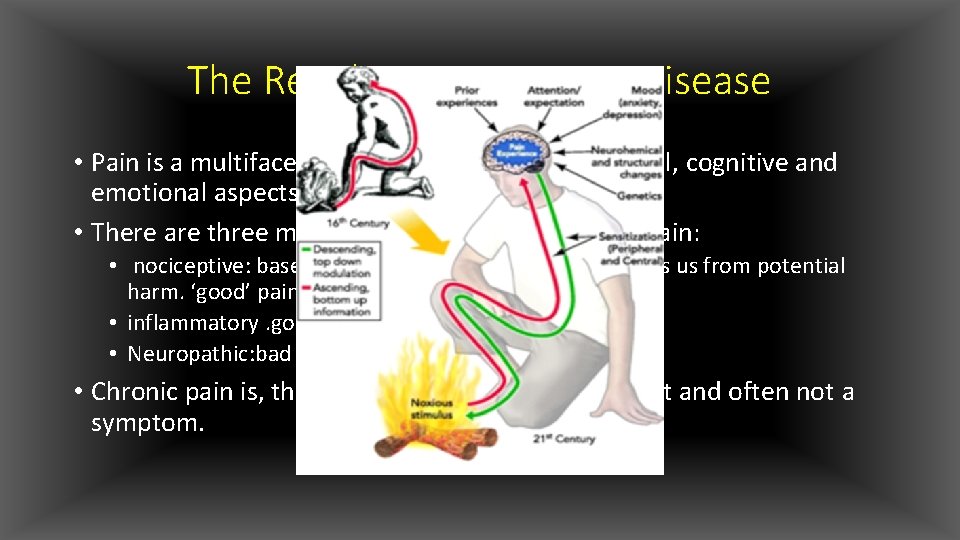

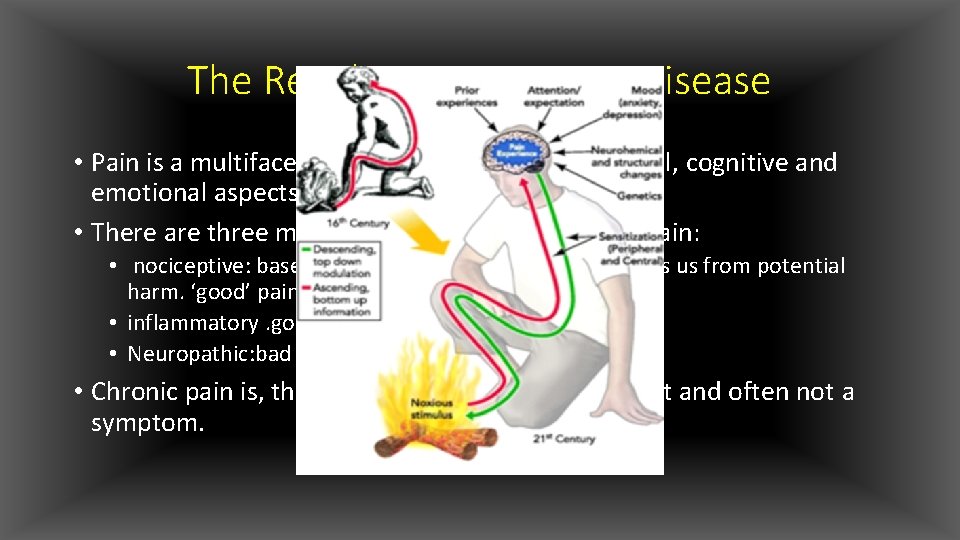

The Revolution: Pain as a Disease • Pain is a multifaceted experience involving physical, cognitive and emotional aspects • There are three mechanistically distinct types of pain: • nociceptive: baseline defence mechanism that protects us from potential harm. ‘good’ pain. • inflammatory. good pain • Neuropathic: bad pain • Chronic pain is, therefore, a disease in its own right and often not a symptom.

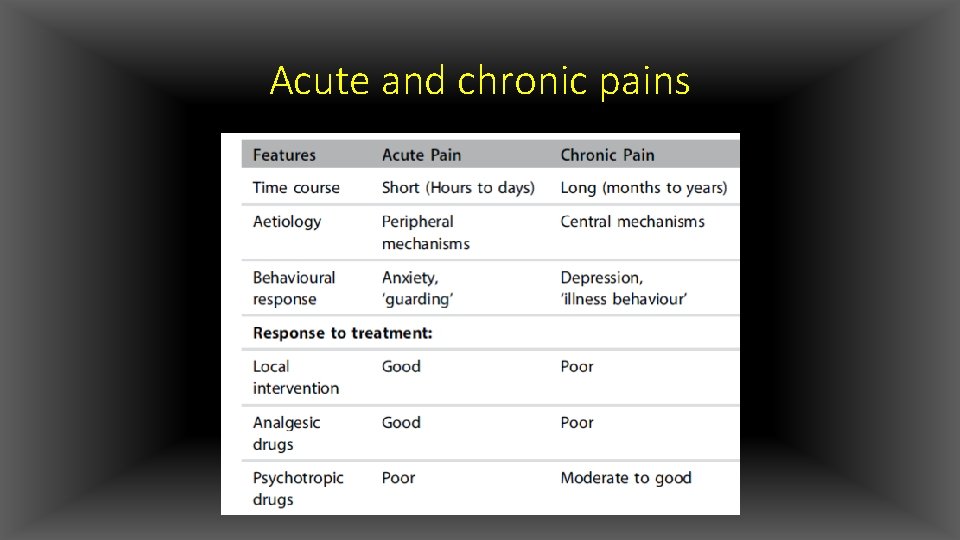

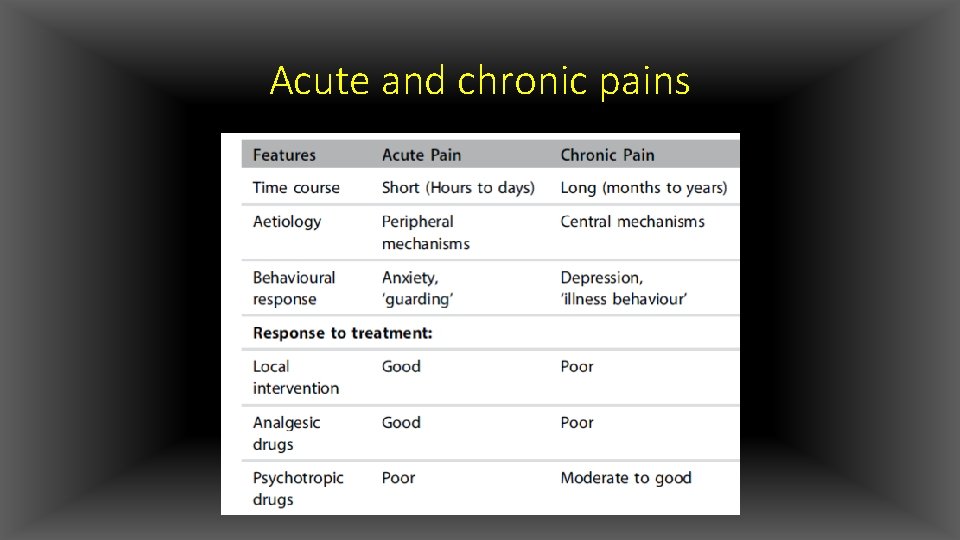

Acute and chronic pains

The Process: Diagnosis of Orofacial Pain • Faced with a patient with a pain complaint we must answer three major questions: • Where: such as the anatomical structure or system affected • What : deals primarily with the pathological process. • Why: is about the aetiology • We routinely start with history taking, the strongest tool when it comes to the diagnosis of pain • physical examination, supplemented by other tests as needed • Gathering information is a starting point, but on its own does not make a diagnosis

The Methodology • Patients are normally willing to tell their ‘story’ or pain history, but there is usually a need to supplement this information with specific questions concerning the location, temporal behaviour, intensity and relation to function and to sensory modalities. • The intake systematically records the basic information needed in a pain history and examination procedures

The Pain History • Location: Precisely identifying location is a complex issue when specifically dealing with orofacial or craniofacial pain; • certain craniofacial pain syndromes have a propensity for particular areas and specific referral patterns. • In order to record location patients should point to the area where they feel the pain. • Pain should also be marked on pre-prepared drawings of extraoral and intraoral regions

Continue • The patient should describe, and outline by finger pointing, whether the pain is localized or diffuse. • Pain may radiate, which means that the pain felt in a certain point spreads in a vector- like fashion or itmay spread in all directions • When the source of pain is in one location but felt in another, remote location, the pain is called referred • .

Continue • Temporal behavior: • age of onset • Pain may occur at specific times of the day • pain onset may be associated with weekly (e. g. weekends), monthly (e. g. menstruation)or even yearly (e. g. seasonal) events • Pain can be intermittent, such as in pulpitis, or continuous, as in muscular pain • Episodic pain, also termed periodic, appears during certain periods; otherwise the patient is pain-free

Continue • Of diagnostic significance is whether the pain wakes the patient from sleep since this is common in neurovascular-type pain or pulpitis • Pain duration • Frequency is the number of attacks over a defined period; per day, week, month or months and in very frequent attacks in units of minutes to hours

Continue • Modes of Onset • When strong pain develops very rapidly in an aggressive fashion such as in pulpitis or trigeminal neuralgia, it is termed paroxysmal. • Pain is evoked when it occurs only after stimulation, e. g. cold application to a tooth with a carious • spontaneous when it occurs on its own with no external stimulus (e. g. pulpitis); or triggered when the pain response is out of proportion to the stimulus, such as is typical for trigeminal neuralgia. • Pain is termed progressive when it becomes more severe, or stronger, over time

Continue • Pain intensity • Pain quality • Trigeminal neuralgia ……sharp or electric • neuropathies ……. burning pain • Neurovascular and dental pain is usually throbbing • Aggravating or alleviating factors • chewing, ingestion of cold or hot drinks or more generalized stimuli such as exposure to cold air, bending down, physical activity, stress or excitement. • rest or sleep often alleviates pain for patients with migraine. The response to simple analgesics or specific medications may often aid in diagnosis

Continue • Impact on daily function and quality of life • chewing, speaking or even tooth brushing • Secondary results may include detrimental dietary changes, social isolation and dental neglect with ensuing pathology. • negative impact on the patient’s general physical function and quality of life. This may reduce the patient’s work capacity and affect the function of the surrounding family members

Continue • Sleep disruption • Prolonged periods of disturbed sleep induce daytime fatigue, sleepiness, difficulties with concentration and reduced coping abilities • may induce generalized muscle pain and reduced pain thresholds and endurance • Irreversible pulpitis or acute dentoalveolar abscess may cause disturbed sleep • fibromyalgia may be pathophysiologically related to specific sleep disorders • patients may often report getting a full night’s sleep but awaken feeling not rested or unrefreshed.

Continue • Associated features • swelling, redness, sweating, tearing, rhinorrhea, and ptosis, or generalized such as nausea, photophobia and dizziness. • Drug history as pertains to the pain condition • It is imperative to record what drugs the patient has tried to alleviate pain. These may be over-the-counter (OTC) drugs or physician-prescribed • Listening to the ‘language of pain • Patients most often describe their pain in the ‘physical’ dimension, • some patients may choose terms that describe an ‘emotional’ dimension

The Physical Examination • aims at identifying the source and cause of pain, i. e. the affected structure and the pathophysiological process. • A routine physical examination of the head and neck should include observation, clinical examination (e. g. palpation) and detection of functional and sensory deviations from the normal. • cervical and submaxillary lymph nodes, parotid and submandibular salivary glands, masticatory and neck muscles and the TMJ to detect any abnormality in texture, mobility or tenderness. • A routine, basic examination of the cranial nerves is also performed • An intraoral examination

Confirmatory Tests • cold stimulus • Radiographs

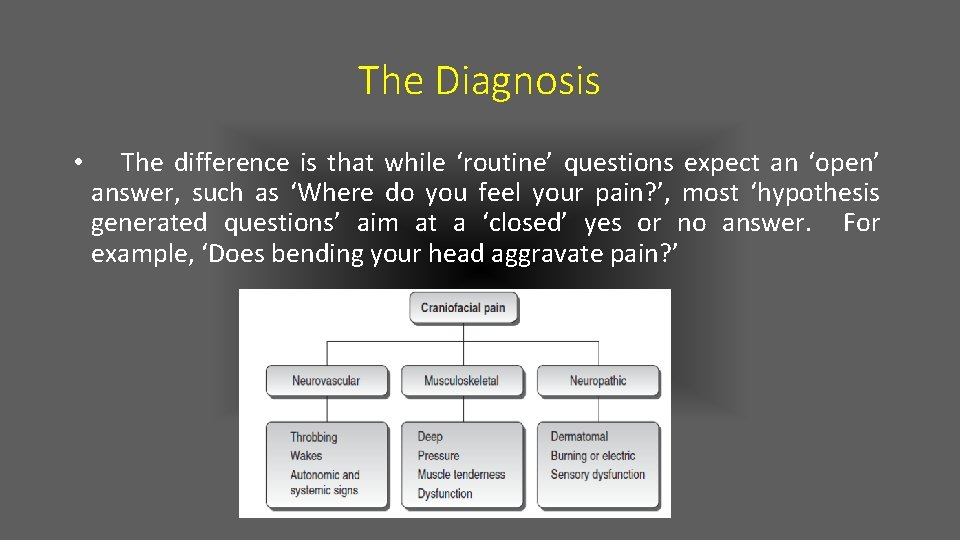

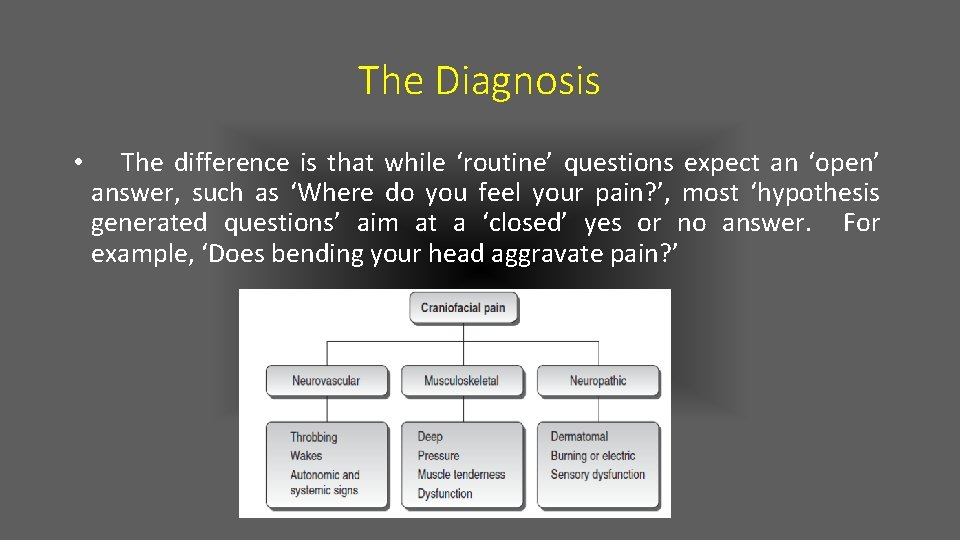

The Diagnosis • The difference is that while ‘routine’ questions expect an ‘open’ answer, such as ‘Where do you feel your pain? ’, most ‘hypothesis generated questions’ aim at a ‘closed’ yes or no answer. For example, ‘Does bending your head aggravate pain? ’

The Pain Patient • A high level of psychological distress is often a predictor of the onset of future pain or the development of chronic pain. Conversely, ongoing orofacial pain is often associated with psychological distress • chronic orofacial pain patients develop maladaptive or illness behaviour patterns that are important factors affecting their management and prognosis

• Genetics The Confounders: Patient Variability, Impact on Diagnosis and Therapy • For example, the analgesic potency of morphine is partly dictated by variations in the expression of mu-opioid receptors. Polymorphisms in this receptor lead to interindividual differences in responses to pain and its relief by opioid drugs • Gender • women consistently demonstrate a lowered pain threshold, often affected by the stage of the menstrual cycle and by exogenous hormones such as oral contraceptives • Women suffer significantly more from migraines, tension-type headaches, facial pains, fibromyalgia and TMDs

Cultural and social factors • These factors affect our patients’ experience of pain, behavioural responses, seeking of healthcare and adherence to treatment

The Aims: Treatment and Follow-up • The initial aim of the diagnostic process is to initiate the patient on a treatment plan; the ultimate, but elusive, aim is the eradication of pain. • Treatment of acute pain often includes physical intervention, e. g. tooth pulp extirpation, and the use of analgesics • the aims of therapy in chronic or recurrent pain cannot be limited to the alleviation of pain but must include the restoration of quality of life and function, and the prevention or elimination of drug abuse

Success • As much as pain is an individual experience, a ‘successful outcome’ is often an individual, highly personalized result

Follow-up • The diary is sufficient for 28 days and makes it possible to adjust treatment according to pain response and side effects

Summary

Refrensess • Orofacial Pain and Headache(Professor Yair Sharav). chap 1 • http: //drshoryabi. ir

Question

Thank you

Faculty of medicine dentistry and health sciences

Faculty of medicine dentistry and health sciences Faculty of veterinary medicine cairo university

Faculty of veterinary medicine cairo university King abdulaziz university faculty of medicine

King abdulaziz university faculty of medicine Dorsocranially

Dorsocranially Hubert kairuki memorial university faculty of medicine

Hubert kairuki memorial university faculty of medicine Coumadin clinic emory

Coumadin clinic emory Territorial matrix vs interterritorial matrix

Territorial matrix vs interterritorial matrix Semmelweis university faculty of medicine

Semmelweis university faculty of medicine Hyperparathyreosis

Hyperparathyreosis Cairo university faculty of veterinary medicine

Cairo university faculty of veterinary medicine Faculty of veterinary medicine cairo university logo

Faculty of veterinary medicine cairo university logo Department of medicine mcgill

Department of medicine mcgill Faculty of medicine nursing and health sciences

Faculty of medicine nursing and health sciences Hacettepe university faculty of medicine

Hacettepe university faculty of medicine Is pregnancy pain same as period pain

Is pregnancy pain same as period pain Pms symptoms

Pms symptoms Lewis mad pain and martian pain

Lewis mad pain and martian pain Dentistry & oral sciences source

Dentistry & oral sciences source Nit calicut chemistry

Nit calicut chemistry Oral medicine

Oral medicine Oral medicine and radiology day

Oral medicine and radiology day Department of medicine solna

Department of medicine solna Mendel university faculty of business and economics

Mendel university faculty of business and economics Integrated university management system

Integrated university management system Feinberg faculty portal

Feinberg faculty portal Singularity executive program

Singularity executive program Collective nouns singular or plural

Collective nouns singular or plural Fsu computer science department

Fsu computer science department University of montenegro faculty of law

University of montenegro faculty of law Matej bel university in banská bystrica

Matej bel university in banská bystrica University of bridgeport computer science faculty

University of bridgeport computer science faculty Motivated energized and capable faculty

Motivated energized and capable faculty Kfupm ee faculty

Kfupm ee faculty The faculty

The faculty Faculty of public health mahidol university

Faculty of public health mahidol university Masaryk university medical faculty

Masaryk university medical faculty