Knowledge LarsGran Johansson Department of philosophy Uppsala University

- Slides: 34

Knowledge Lars-Göran Johansson Department of philosophy Uppsala University lars-goran. johansson@filosofi. uu. se Homepage: www. anst. uu. se/lajoh 623

Knowledge: Scientific and other • Two forms of knowledge: • Knowing that: the content of a belief. • Knowing how: an ability • Belief-contents can be expressed by declarative sentences!

Knowing that – knowing how • Compare: • Peter knows that Berlin is the capital of Germany • Susan knows how to ride a bicycle • N. B. The content of a belief is expressed by a complete sentence, the ability with a verb-phrase only.

Knowing that • In the sequel, I will talk only about knowing that, also called propositional knowledge. • Not because knowledge-how is unimportant; but because knowing-that is a much more controversial and problematic concept.

A posteriori- a priori knowledge • Knowledge a priori: knowledge which is independent of our senses • Knowledge a posteriori: knowledge which ultimately depends our senses. • Mathematical and logical knowledge consists of knowledge a priori • Empirical knowledge is a posteriori

A priori knowledge • How is it possible to have a priori knowledge? • Is it innate? • Do we have extra-sensoric abilities (intuiitons)? • Is it knowledge about our own constructed concepts? (My view: the last option is the true one. )

A priori knowledge • Logical and mathematical knowledge is knowledge about • • human constructions. Such knowledge is true by definition. To a mind with infinite cognitive capacity, all mathematical and logical truths would as trivial as 0+1=1 Logical truths are truths about how to use the logical constants consistently. Logic can never say anything about the real world

Belief and knowledge • People often distinguish belief and knowledge as if they were two completely different things. • But both are states of mind. • And one cannot say ‘I know such and so, but I don’t believe it’. • To know something is to believe it; but something more is needed.

Plato’s definition • X knows that p if and only if – P is true – X have good reasons for p – X believes p

Truth • Why make truth a condition of knowledge? • Isn’t knowledge simply everything we believe with good • • reasons? No; one can believe with very good reasons what is false. What’s the point of asking for knowledge, if truth is not the goal? Knowledge is more than mere opinion We are interested in more than beliefs; we want to know the facts!

Truth • Minimal requirement on the concept of truth: • ‘p’ is true if and only if p • In other words: • To say about a statement that it is true is the same as to ascertain that statement

Theories of truth • Correspondence • Coherence • Pragmatist • Minimal or deflationary

Beliefs • To belief something is a mental state • If we accept that a necessary condition for knowledge is belief, then no thing that lacks mentality can have knowledge. • Could a machine have knowledge? • Could an animal have knowledge?

Good reasons • Good reasons may be of two forms: • Justification • Evidence • (OBS. This is a distinction made by some philosophers; in ordinary discourse no distinction is made. )

Justification • Justification is a relation between beliefs • If you believe a proposition p and is asked for its justification, you should provide another proposition q, (or a set of propositions). • The proposition q justifies p • Typical example: mathematical proofs

Proof • A proof is a sequence of statements • The sequence begins with one or several • • • assumptions and ends with the proved sentence. Suppose A, B and C are the premises in the proof of Q, i. e. , A, B, C ⊢ Q Then: A, B and C together completely justifies Q!

Justification outside math and logic: Ex: scientific laws • The general law of gases, p. V=n. RT, is justified by individual observation reports, i. e. , sentences expressing that portions of gases satisfy this equation. • More instances increases the justification of the general law. • But no amount of instances will prove it. • Justifcation is not complete

Inductive reasoning • Inductive reasoning proceeds from singular • • • statements to a general statement, sometimes a scientific law. More instances makes the conclusion more trustworthy; but complete justification is never attained. Inductive reasoning is uncertain. We cannot prove anything by inductive reasoning!

Inductive reasoning: example • • • Hypothesis: All pieces of metal expand when heated. We observe many cases where this is true. We have never observed any counterinstance. But this does not guarantee the hypothesis. The inference from ‘All observed A: s are B’ to ‘All A: s are B’ is not logically valid. We cannot exclude the possibility that the next observed instance contradicts the hypothesis.

Observation- belief • When we perform an experiment we observe • • • certain outcomes. Most often we immediately believe the propositions expressing these observations. But observing the outcome and believing the proposition describing the outcome are different things. We can imagine saying ‘I see x, but I don’t believe it!’

Observation - belief • The belief in a proposition expressing an • • observation may justify another proposition, for example a scientific law. But the observation cannot justify the proposition expressing the observation! For an observation is not a belief; The following are different mental states! – I saw Zlatan in city center yesterday – I believe Zlatan was in city center yesterday

Observation - Belief • To observe something does not require any • • judgement. Observation is perceptual experience. We may occasionally doubt what we observe; We judge whether to believe the content of the observation or not! Hence, observing that p and believing that p are different things.

Observation- -belief • From the movie ‘A beatiful mind’: • John Nash is approached by a person outside the lecture hall. Nash asks one of his students: “Do you see this man? ” • Obviously, Nash doubts his observation. • His reason for doing so: he knows he sometimes hallucinate.

Observation give evidence for beliefs • Some have thought that since the chain of justification must end somewhere, and since observations cannot justify any belief, we are left in the sceptical mood, it seems. • But certainly, seing rain somehow support the belief that it is raining.

Evidence –the relation between observations and beliefs • Following Susan Haack: • The relation between an observation and a belief (that the observation is true) is an evidential relation • An observation provides evidence for the belief: • I observe an elk in front of the wood, and that is evidence for my belief that there is an elk in front of the wood.

Good reason-Justification. Evidence • A certain belief is justified by other beliefs • This leads to an endless regress, unless – There are some beliefs that justifies themselves, or – There are some beliefs that do not need justification. Our good reasons for some beliefs consist in observational evidence, not that they are justified!

Good reason-Justification. Evidence • A belief is justified by other beliefs • The chains of justification ends with beliefs for which no other justifying beliefs exist. • Our good reasons for these beliefs consist in us having empirical evidence for them

Analogy- crossword puzzle • The starting points for the solution of a crossword puzzle are the clues. • When we are in the process we use letters from earlier guessed words as additional help. • Analogy: clues – observational evidence • Letters from earlier guessed words - other beliefs that justifies a certain guess, and is inconsistent with other guesses.

Analogy- crossword puzzle • The correctness of the solution judged by – Reasonable connection between clues their corresponding items – Everything fits together • Analogy: a true theory must both be supported by observational evidence and be coherent.

Justifcation in logic and math • Axioms in mathematics are not justified; neither do we have evidence for them. • But how can we say we know them? • Axioms may be viewed as implicit definitions of the concepts used in stating them. • A priori knowledge is knowledge about usage of concepts.

Empirical knowledge • Empirical knowledge is ultimately based on sensory evidence, i. e. observations. • Empirical knowledge is fallible and revisable. • Observations are not proofs; but they provide evidence to some degree.

Fallibilism • It is possible that we have made a mistake when • • • we claim to know p. If p is the conclusion of an inductive inference: no number of observations guarantee the conclusion. If p is the conclusion of a deductive inference: the premises might be false. If p is an empirical observation: Perceptions are not completely certain.

Fallible knowledge • Almost any claim of having knowledge might be wrong. • If so, we should not say that we have false knowledge. • Instead we should say: we believed that we knew, but, since content of the belief is false, we should withdraw the knowledge claim: we had no knowledge.

Is knowledge certain? • When someone claims to know p, she claims that: – P is true – She has good reasons for believing p – She believes p. The degree of subjective certainty is not relevant! It is supposed that for any p, either one believes p or one does not.

Stanford university philosophy department

Stanford university philosophy department Oefeningen sinding larsen johansson

Oefeningen sinding larsen johansson Per holmlund meteorolog

Per holmlund meteorolog Scarlett johansson 2014

Scarlett johansson 2014 Dr olga johansson

Dr olga johansson Cheerios scarlett johansson

Cheerios scarlett johansson Frans johansson medici effect

Frans johansson medici effect Toril johansson

Toril johansson Nina monsef johansson

Nina monsef johansson Natalia la porta wiki

Natalia la porta wiki Leif johansson religion

Leif johansson religion Frans johansson medici effect

Frans johansson medici effect Common misconceptions about philosophy

Common misconceptions about philosophy Sociologiska institutionen uppsala

Sociologiska institutionen uppsala Uppsala skidgymnasium

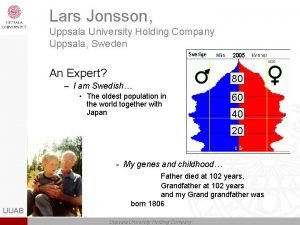

Uppsala skidgymnasium Lars jonsson uppsala

Lars jonsson uppsala Karuselldagen uppsala

Karuselldagen uppsala Anders berglund uppsala

Anders berglund uppsala Anna singer adoption

Anna singer adoption Region uppsala

Region uppsala Bodelning

Bodelning Filosofiska institutionen uppsala

Filosofiska institutionen uppsala Niclas abrahamsson uppsala

Niclas abrahamsson uppsala Barnskyddsteamet uppsala

Barnskyddsteamet uppsala Sjukanmälan katedralskolan uppsala

Sjukanmälan katedralskolan uppsala Uppsala theory

Uppsala theory Gunnar enlund uppsala

Gunnar enlund uppsala Olle lundin uppsala

Olle lundin uppsala Antagligen

Antagligen Uppsala uppsatser

Uppsala uppsatser Språkskolan uppsala

Språkskolan uppsala Läkarprogrammet uppsala

Läkarprogrammet uppsala Uppsala universitet teknisk fysik

Uppsala universitet teknisk fysik Scandinova modulator

Scandinova modulator Sydöstra uppsala

Sydöstra uppsala