Gret was the sorwe and pleynte of Troilus

- Slides: 22

Gret was the sorwe and pleynte of Troilus; But forth hire cours Fortune ay gan to holde. Criseyde loveth the sone of Tideus, And Troilus moot wepe in cares colde. Swich is this world, whoso it kan byholde: In ech estat is litel hertes reste. God leve us forto take it for the beste! In many cruel bataille, out of drede, Of Troilus, this ilke noble knyght, As men may in thise olde bokes rede, Was seen his knyghthod and his grete myght; And dredeles, his ire, day and nyght Ful cruwely the Grekis ay aboughte, And alwey moost this Diomede he soughte. And ofte tyme, I fynde that they mette With blody strokes and with wordes grete, Assayinge how hire speres weren whette; And God it woot, with many a cruel hete Gan Troilus upon his helm to bete! But natheles, Fortune it naught ne wolde Of oothers hond that eyther deyen sholde.

And if I hadde ytaken for to write The armes of this ilke worthi man, Than wolde ich of his batailles endite; But for that I to writen first bigan Of his loue, I have seyd as I kan -- Hise worthi dedes, whoso list hem heere, Rede Dares, he kan telle hem alle ifeere -- Bysechyng every lady bright of hewe, And every gentil womman, what she be, That al be that Criseyde was untrewe, That for that gilt she be nat wroth with me: Ye may hire gilt in other bokes se, And gladlier I wol write, yif yow leste, Penelopees trouthe and good Alceste. N’y sey nat this al oonly for thise men, But moost for wommen that bitraised be Thorugh false folk; god yeve hem sorwe, amen! That with hire grete wit and subtilte Bytraise yow; and this commeveth me To speke, and in effect yow alle I preye, Beth war of men, and herkneth what I seye!

Go, litel boke, go, litel myn tragedye, Ther God thi makere yet, er that he dye, So sende myght to make in some comedye! But litel book, no makyng thow n’envie, But subgit be to alle poesye, And kis the steppes where as thow seest space Virgile, Ovide, Omer, Lucan and Stace. And for ther is so gret diuersite In Englissh and in writyng of oure tonge, So prey I God that non myswrite the, Ne the mysmetre for defaute of tonge. And red wherso thow, or elles songe, That thow be understonde, God I biseche. But 3 et to purpos of my rather speche:

The wrath, as I bigan yow for to seye, Of Troilus the Grekis boughten deere, For thousandes his hondes maden deye, As he that was withouten any peere, Save Ector, in his tyme, as I kan heere. But--weilawey, save only Goddes wille, Despitously hym slough the fierse Achille.

And whan that he was slayn in this manere, His light goost ful blisfully is went Up to the holoughnesse of the eighthe spere In convers letyng everich element; The erratik sterres, herkenyng armonye With sownes ful of hevenyssh melodie. And down from thennes faste he gan avyse This litel spot of erthe that with the se Embraced is, and fully gan despise This wrecched world, and held al vanite To respect of the pleyn felicite That is in hevene above; and at the laste, Ther he was slayn his lokyng doun he caste, And in hymself he lough right at the wo Of hem that wepten for his deth so faste, And dampned al oure werk that foloweth so The blynde lust, the which that may nat laste, And sholden al oure herte on heven caste; And forth he went, shortly for to telle, Ther as Mercurye sorted hym to dwelle.

Swich fyn hath, lo, this Troilus for love! Swich fyn hath al his grete worthynesse! Swich fyn hath his estat real above! Swich fyn his lust, swich fyn hath his noblesse! Swich fyn hath false worldes brotelnesse! And thus bigan his lovyng of Criseyde, As I have told, and in this wise he deyde. O yonge, fresshe folkes, he or she, In which that love up groweth with youre age, Repeyreth hom fro worldly vanyte, And of youre herte up casteth the visage To thilke God that after his ymage Yow made, and thynketh al nys but a faire, This world that passeth soone as floures faire And loveth hym the which that right for love Upon a crois, oure soules for to beye, First starf, and roos, and sit in hevene above; For he nyl falsen no wight, dar I seye, That wol his herte al holly on him leye. And syn he best to love is, and most meke, What nedeth feynede loves for to seke?

Lo here, of payens corsed olde rites! Lo here, what alle hire goddes may availle; Lo here, thise wrecched worldes appetites! Lo here, the fyn and guerdoun for travaille Of Jove, Appollo, of Mars, of swich rascaille! Lo here, the forme of olde clerkis speche In poetrie, if ye hire bokes seche. O moral Gower, this book I directe To the, and to the, philosophical Strode, To vouchen-sauf, ther nede is, to correcte, Of youre benignites and zeles goode. And to that sothfast Crist, that starf on rode, With al myn herte of mercy evere I preye, And to the Lord right thus I speke and seye: Thow oon, and two, and thre, eterne on lyue, That regnest ay in thre, and two, and oon, Uncircumscript, and al maist circumscrive, Us from visible and invisible foon Defende, and to thy mercy, euerichon, So make vs, Jesus, for thi mercy digne, For loue of mayde and moder thyn benigne. Amen.

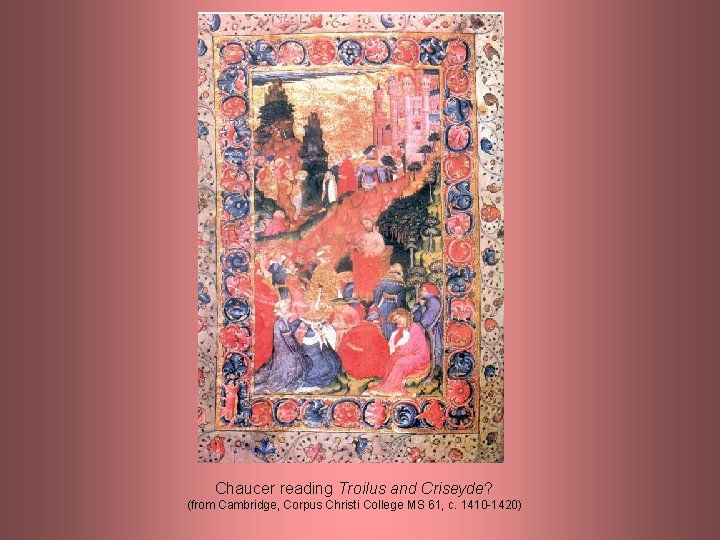

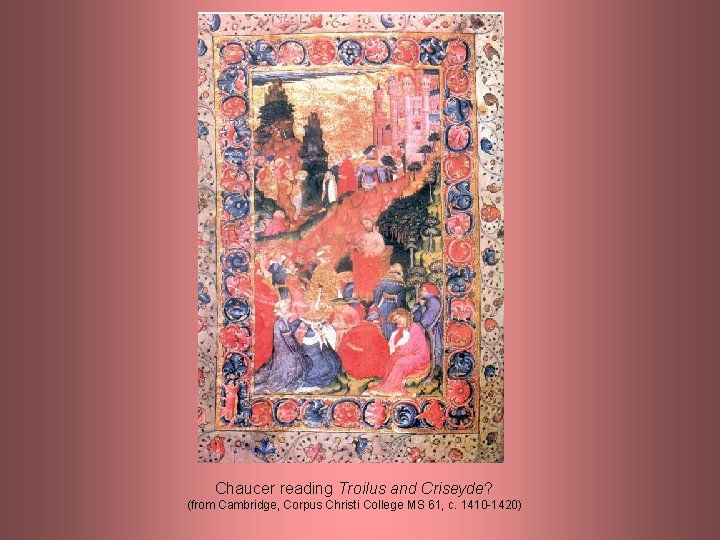

Chaucer reading Troilus and Criseyde? (from Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 61, c. 1410 -1420)

Once when the Roman emperor Trajan was hurrying off to war with all possible speed, a widow ran up to him in tears and said: "Be good enough, I beg you, to avenge the blood of my son, who was put to death though he was innocent!" Trajan answered that if he came back from the war safe and sound, he would take care of her case. "And if you die in battle, " the widow objected, "who then will see that justice is done? " "Whoever rules after me, " Trajan replied. "And what good will it do you, " the widow argued, "if someone else rights my loss? " "None at all!" the emperor retorted. "Then wouldn't it be better for you, " the woman persisted, "to do me justice yourself and receive the reward, than to pass it on to someone else? " Trajan, moved with compassion, got down from his horse and saw to it that the blood of the innocent was avenged. . . “The Justice of Trajan” Eugene Delacroix, 1840

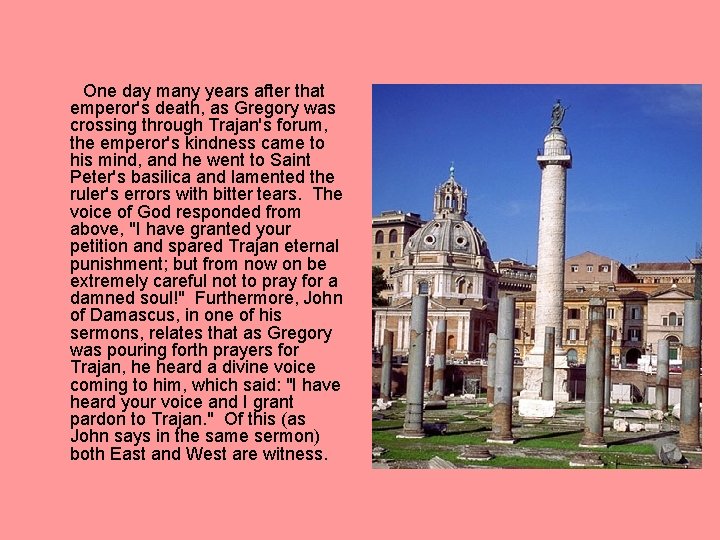

One day many years after that emperor's death, as Gregory was crossing through Trajan's forum, the emperor's kindness came to his mind, and he went to Saint Peter's basilica and lamented the ruler's errors with bitter tears. The voice of God responded from above, "I have granted your petition and spared Trajan eternal punishment; but from now on be extremely careful not to pray for a damned soul!" Furthermore, John of Damascus, in one of his sermons, relates that as Gregory was pouring forth prayers for Trajan, he heard a divine voice coming to him, which said: "I have heard your voice and I grant pardon to Trajan. " Of this (as John says in the same sermon) both East and West are witness.

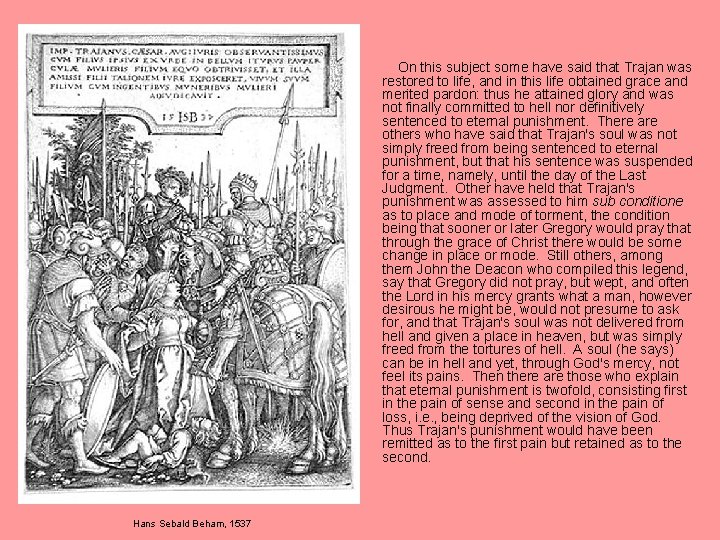

On this subject some have said that Trajan was restored to life, and in this life obtained grace and merited pardon: thus he attained glory and was not finally committed to hell nor definitively sentenced to eternal punishment. There are others who have said that Trajan's soul was not simply freed from being sentenced to eternal punishment, but that his sentence was suspended for a time, namely, until the day of the Last Judgment. Other have held that Trajan's punishment was assessed to him sub conditione as to place and mode of torment, the condition being that sooner or later Gregory would pray that through the grace of Christ there would be some change in place or mode. Still others, among them John the Deacon who compiled this legend, say that Gregory did not pray, but wept, and often the Lord in his mercy grants what a man, however desirous he might be, would not presume to ask for, and that Trajan's soul was not delivered from hell and given a place in heaven, but was simply freed from the tortures of hell. A soul (he says) can be in hell and yet, through God's mercy, not feel its pains. Then there are those who explain that eternal punishment is twofold, consisting first in the pain of sense and second in the pain of loss, i. e. , being deprived of the vision of God. Thus Trajan's punishment would have been remitted as to the first pain but retained as to the second. Hans Sebald Beham, 1537

One does not have to subscribe fully to E. T. Donaldson's characterization of the end of the poem as "a kind of nervous breakdown in poetry" to see the last hundred lines as preserving a sequence of provisional and patently unsuccessful attempts at bringing things to a conclusion. As Lee Patterson observes, "Criticism has often described what Lowes long ago called 'the tumultuous hitherings and thitherings of mood and matter in the last dozen stanzas of the poem, ' descriptions that provide vivid evidence of the interpretive impasse to which the poem brings both its narrator and its readers. " That impasse arises, to put it most simply, from a problem of transition: how does a poet so deeply engaged with his portrait of pagan Troy that generations of critics have been induced to identify the narrator as virtually a fourth major character manage to disengage himself from that world and return to his own present in a way that won't do a kind of rhetorical violence to the preceding 8000 lines? And the solution to that problem is Troilus's apotheosis, which is what formally enables this transition to take place. If, as I have argued, literary representations of the righteous heathen are more than just exercises in popular theological casuistry--if they express an urgent cultural need to explore and understand the possibility of an ethical genealogy that connects the pre-Christian past with the post-revelation present--then thematically Chaucer's description of Troilus's flight occurs just at the point we might expect it to, at the moment when the poem moves definitively forward from its dream of pagan Troy to fourteenth-century England. Over the closing stanzas of the poem, as Troilus moves from the battlefield to the eighth sphere and beyond, we move with him from the past to the Christian present of the poem's composition and reception, but the various rhetorical gambits Chaucer employs in this concluding passage are apparently not in themselves sufficient to make the transition possible; what's required is the special effect represented by Troilus's apotheosis. To put it another way, the translatio of Troilus accomplishes in small what the "epilogue" of Troilus and Criseyde does for the poem as a whole, and its subject: it both recuperates (in the sense of making ideologically intelligible) and recovers (in the sense of claiming as one's own, out of desire and esteem) the Trojan past, its heroes and ladies and its anachronistically courtly and romantic culture.

And for ther is so gret diversite In Englissh and in writyng of oure tonge, So prey I God that non myswrite the, Ne the mysmetre for defaute of tonge. And red wherso thow be, or elles songe, That thow be understonde, God I biseche. But yet to purpos of my rather speche… TC 5. 1793 -99

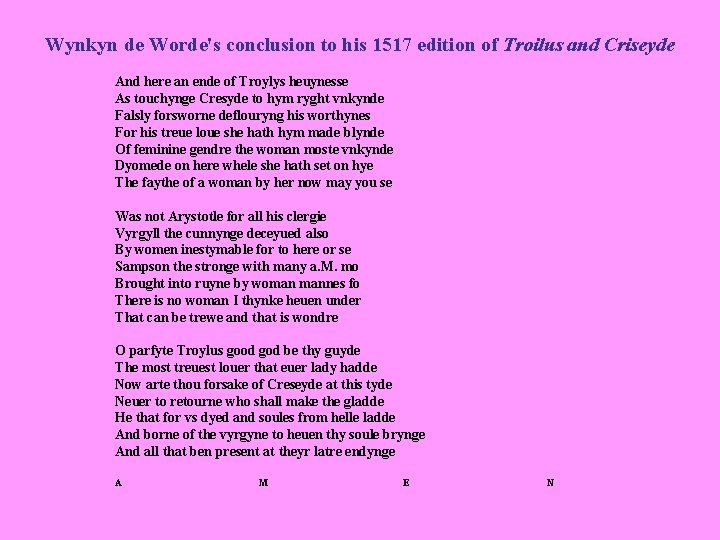

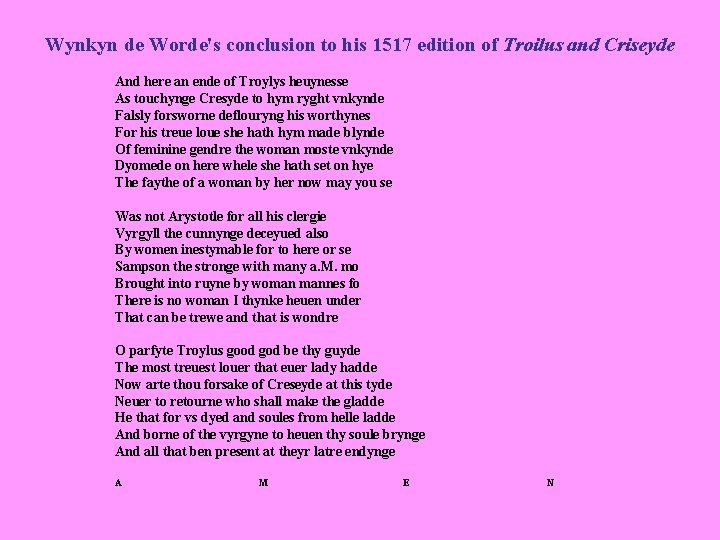

Wynkyn de Worde's conclusion to his 1517 edition of Troilus and Criseyde And here an ende of Troylys heuynesse As touchynge Cresyde to hym ryght vnkynde Falsly forsworne deflouryng his worthynes For his treue loue she hath hym made blynde Of feminine gendre the woman moste vnkynde Dyomede on here whele she hath set on hye The faythe of a woman by her now may you se Was not Arystotle for all his clergie Vyrgyll the cunnynge deceyued also By women inestymable for to here or se Sampson the stronge with many a. M. mo Brought into ruyne by woman mannes fo There is no woman I thynke heuen under That can be trewe and that is wondre O parfyte Troylus good god be thy guyde The most treuest louer that euer lady hadde Now arte thou forsake of Creseyde at this tyde Neuer to retourne who shall make the gladde He that for vs dyed and soules from helle ladde And borne of the vyrgyne to heuen thy soule brynge And all that ben present at theyr latre endynge A M E N

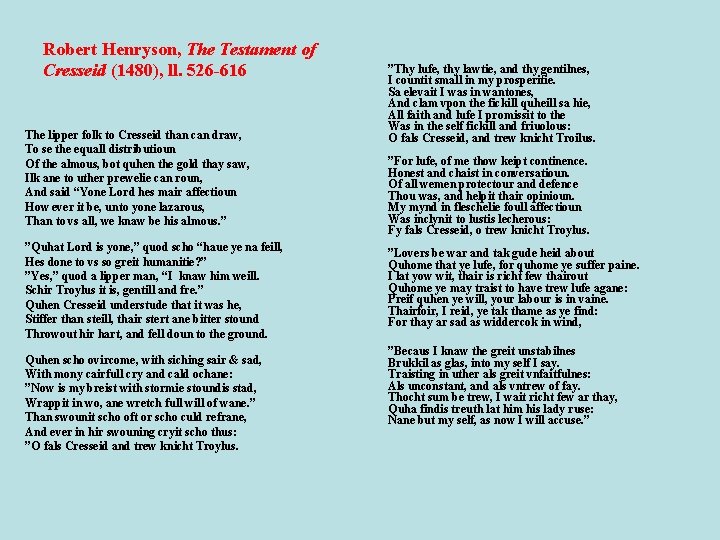

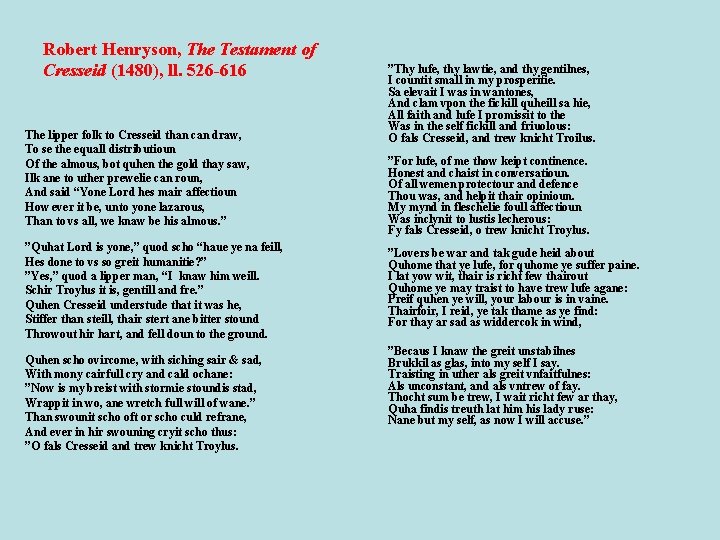

Robert Henryson, The Testament of Cresseid (1480), ll. 526 -616 The lipper folk to Cresseid than can draw, To se the equall distributioun Of the almous, bot quhen the gold thay saw, Ilk ane to uther prewelie can roun, And said “Yone Lord hes mair affectioun How ever it be, unto yone lazarous, Than to vs all, we knaw be his almous. ” ”Quhat Lord is yone, ” quod scho “haue ye na feill, Hes done to vs so greit humanitie? ” ”Yes, ” quod a lipper man, “I knaw him weill. Schir Troylus it is, gentill and fre. ” Quhen Cresseid understude that it was he, Stiffer than steill, thair stert ane bitter stound Throwout hir hart, and fell doun to the ground. Quhen scho ovircome, with siching sair & sad, With mony cairfull cry and cald ochane: ”Now is my breist with stormie stoundis stad, Wrappit in wo, ane wretch full will of wane. ” Than swounit scho oft or scho culd refrane, And ever in hir swouning cryit scho thus: ”O fals Cresseid and trew knicht Troylus. ”Thy lufe, thy lawtie, and thy gentilnes, I countit small in my prosperitie. Sa elevait I was in wantones, And clam vpon the fickill quheill sa hie, All faith and lufe I promissit to the Was in the self fickill and friuolous: O fals Cresseid, and trew knicht Troilus. ”For lufe, of me thow keipt continence. Honest and chaist in conversatioun. Of all wemen protectour and defence Thou was, and helpit thair opinioun. My mynd in fleschelie foull affectioun Was inclynit to lustis lecherous: Fy fals Cresseid, o trew knicht Troylus. ”Lovers be war and tak gude heid about Quhome that ye lufe, for quhome ye suffer paine. I lat yow wit, thair is richt few thairout Quhome ye may traist to have trew lufe agane: Preif quhen ye will, your labour is in vaine. Thairfoir, I reid, ye tak thame as ye find: For thay ar sad as widdercok in wind, ”Becaus I knaw the greit unstabilnes Brukkil as glas, into my self I say. Traisting in uther als greit vnfaitfulnes: Als unconstant, and als vntrew of fay. Thocht sum be trew, I wait richt few ar thay, Quha findis treuth lat him his lady ruse: Nane but my self, as now I will accuse. ”

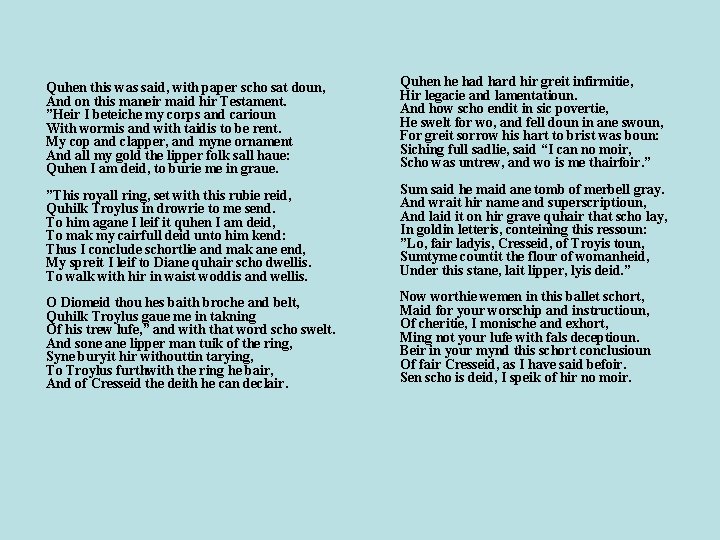

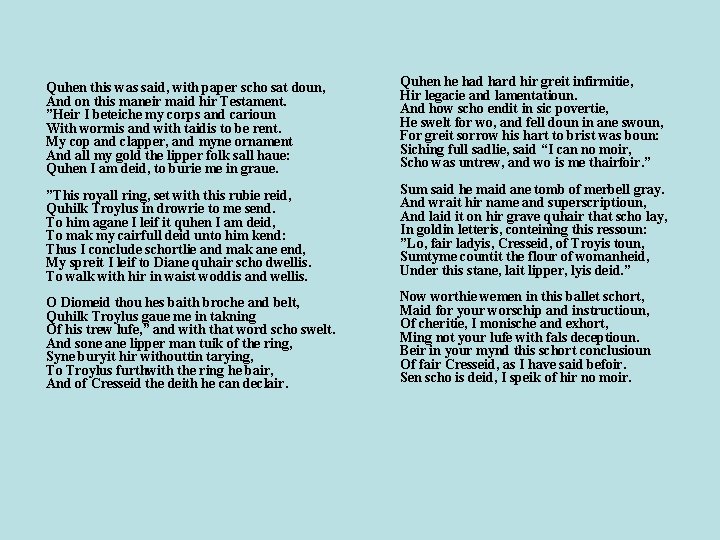

Quhen this was said, with paper scho sat doun, And on this maneir maid hir Testament. ”Heir I beteiche my corps and carioun With wormis and with taidis to be rent. My cop and clapper, and myne ornament And all my gold the lipper folk sall haue: Quhen I am deid, to burie me in graue. Quhen he had hard hir greit infirmitie, Hir legacie and lamentatioun. And how scho endit in sic povertie, He swelt for wo, and fell doun in ane swoun, For greit sorrow his hart to brist was boun: Siching full sadlie, said “I can no moir, Scho was untrew, and wo is me thairfoir. ” ”This royall ring, set with this rubie reid, Quhilk Troylus in drowrie to me send. To him agane I leif it quhen I am deid, To mak my cairfull deid unto him kend: Thus I conclude schortlie and mak ane end, My spreit I leif to Diane quhair scho dwellis. To walk with hir in waist woddis and wellis. Sum said he maid ane tomb of merbell gray. And wrait hir name and superscriptioun, And laid it on hir grave quhair that scho lay, In goldin letteris, conteining this ressoun: ”Lo, fair ladyis, Cresseid, of Troyis toun, Sumtyme countit the flour of womanheid, Under this stane, lait lipper, lyis deid. ” O Diomeid thou hes baith broche and belt, Quhilk Troylus gaue me in takning Of his trew lufe, ” and with that word scho swelt. And sone ane lipper man tuik of the ring, Syne buryit hir withouttin tarying, To Troylus furthwith the ring he bair, And of Cresseid the deith he can declair. Now worthie wemen in this ballet schort, Maid for your worschip and instructioun, Of cheritie, I monische and exhort, Ming not your lufe with fals deceptioun. Beir in your mynd this schort conclusioun Of fair Cresseid, as I have said befoir. Sen scho is deid, I speik of hir no moir.

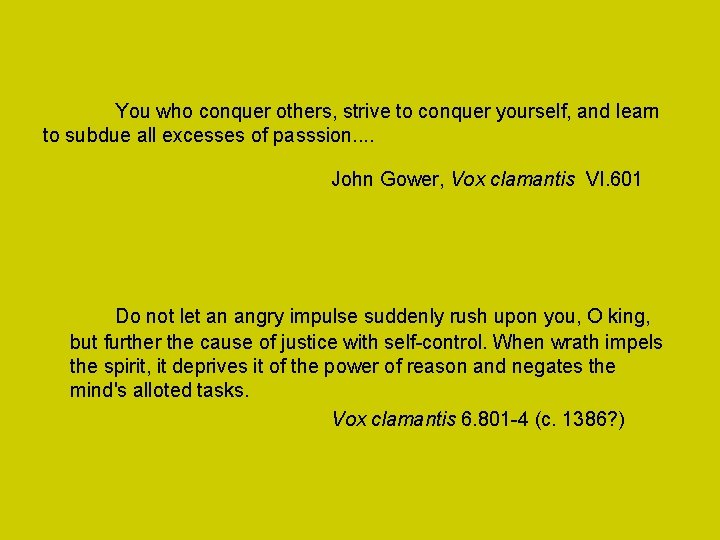

You who conquer others, strive to conquer yourself, and learn to subdue all excesses of passsion. . John Gower, Vox clamantis VI. 601 Do not let an angry impulse suddenly rush upon you, O king, but further the cause of justice with self-control. When wrath impels the spirit, it deprives it of the power of reason and negates the mind's alloted tasks. Vox clamantis 6. 801 -4 (c. 1386? )

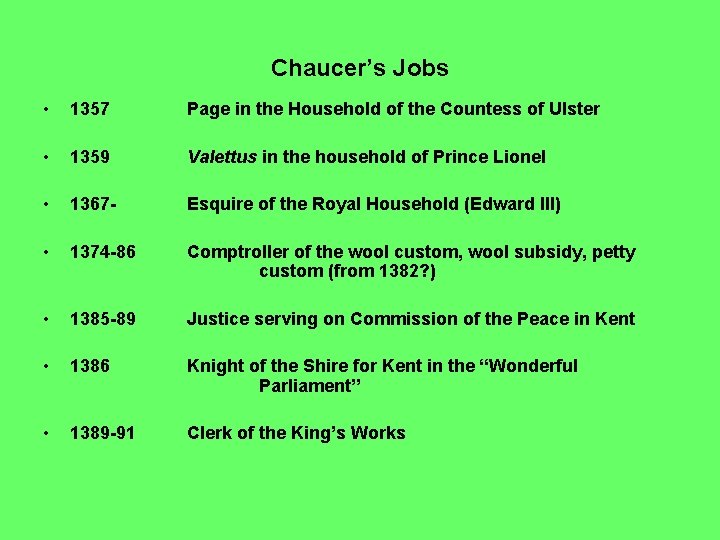

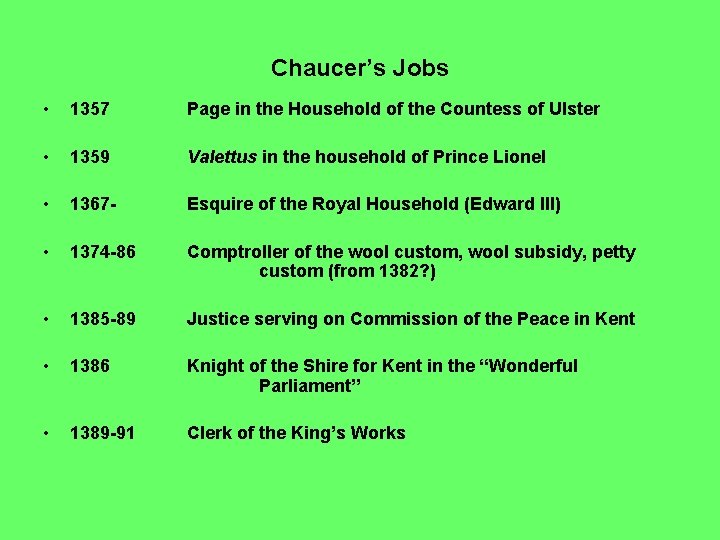

Chaucer’s Jobs • 1357 Page in the Household of the Countess of Ulster • 1359 Valettus in the household of Prince Lionel • 1367 - Esquire of the Royal Household (Edward III) • 1374 -86 Comptroller of the wool custom, wool subsidy, petty custom (from 1382? ) • 1385 -89 Justice serving on Commission of the Peace in Kent • 1386 Knight of the Shire for Kent in the “Wonderful Parliament” • 1389 -91 Clerk of the King’s Works

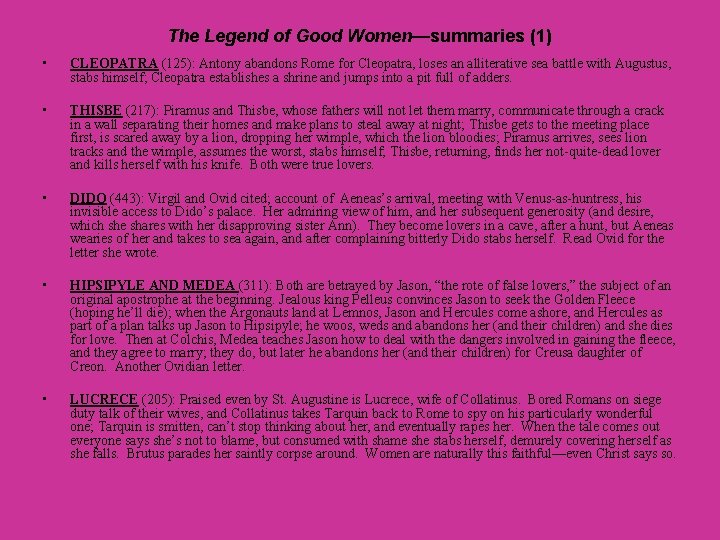

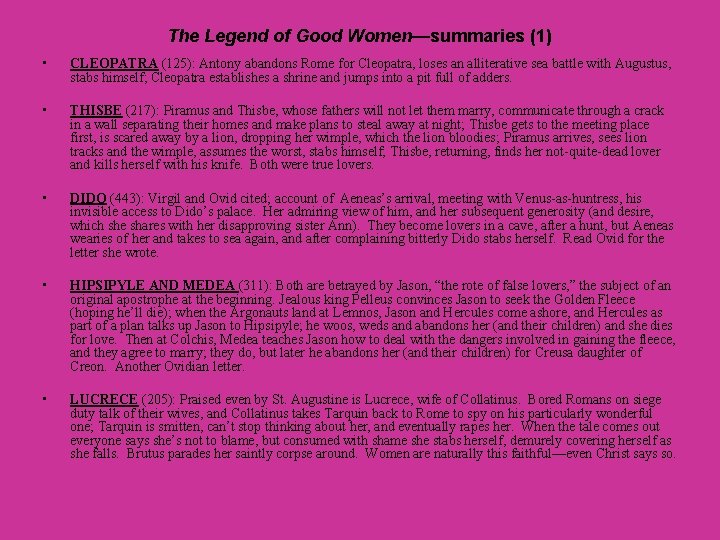

The Legend of Good Women—summaries (1) • CLEOPATRA (125): Antony abandons Rome for Cleopatra, loses an alliterative sea battle with Augustus, stabs himself; Cleopatra establishes a shrine and jumps into a pit full of adders. • THISBE (217): Piramus and Thisbe, whose fathers will not let them marry, communicate through a crack in a wall separating their homes and make plans to steal away at night; Thisbe gets to the meeting place first, is scared away by a lion, dropping her wimple, which the lion bloodies; Piramus arrives, sees lion tracks and the wimple, assumes the worst, stabs himself; Thisbe, returning, finds her not-quite-dead lover and kills herself with his knife. Both were true lovers. • DIDO (443): Virgil and Ovid cited; account of Aeneas’s arrival, meeting with Venus-as-huntress, his invisible access to Dido’s palace. Her admiring view of him, and her subsequent generosity (and desire, which she shares with her disapproving sister Ann). They become lovers in a cave, after a hunt, but Aeneas wearies of her and takes to sea again, and after complaining bitterly Dido stabs herself. Read Ovid for the letter she wrote. • HIPSIPYLE AND MEDEA (311): Both are betrayed by Jason, “the rote of false lovers, ” the subject of an original apostrophe at the beginning. Jealous king Pelleus convinces Jason to seek the Golden Fleece (hoping he’ll die); when the Argonauts land at Lemnos, Jason and Hercules come ashore, and Hercules as part of a plan talks up Jason to Hipsipyle; he woos, weds and abandons her (and their children) and she dies for love. Then at Colchis, Medea teaches Jason how to deal with the dangers involved in gaining the fleece, and they agree to marry; they do, but later he abandons her (and their children) for Creusa daughter of Creon. Another Ovidian letter. • LUCRECE (205): Praised even by St. Augustine is Lucrece, wife of Collatinus. Bored Romans on siege duty talk of their wives, and Collatinus takes Tarquin back to Rome to spy on his particularly wonderful one; Tarquin is smitten, can’t stop thinking about her, and eventually rapes her. When the tale comes out everyone says she’s not to blame, but consumed with shame she stabs herself, demurely covering herself as she falls. Brutus parades her saintly corpse around. Women are naturally this faithful—even Christ says so.

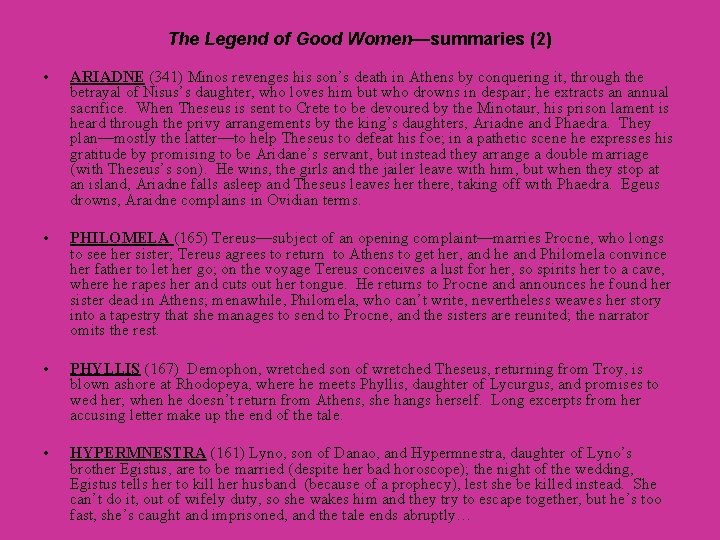

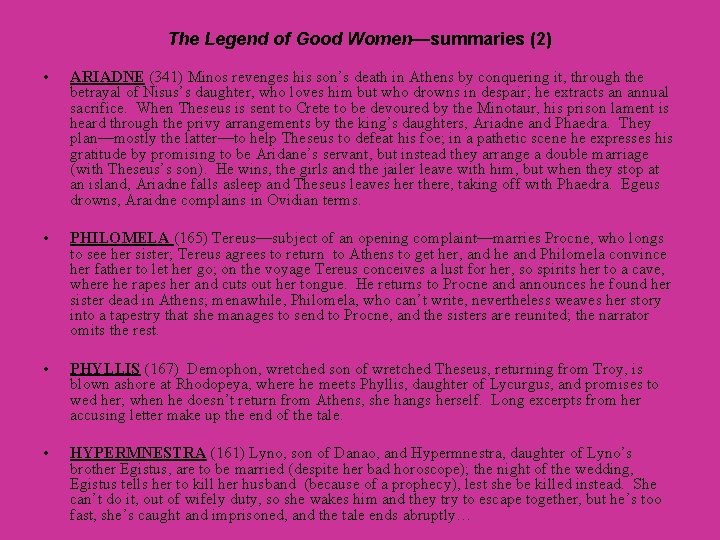

The Legend of Good Women—summaries (2) • ARIADNE (341) Minos revenges his son’s death in Athens by conquering it, through the betrayal of Nisus’s daughter, who loves him but who drowns in despair; he extracts an annual sacrifice. When Theseus is sent to Crete to be devoured by the Minotaur, his prison lament is heard through the privy arrangements by the king’s daughters, Ariadne and Phaedra. They plan—mostly the latter—to help Theseus to defeat his foe; in a pathetic scene he expresses his gratitude by promising to be Aridane’s servant, but instead they arrange a double marriage (with Theseus’s son). He wins, the girls and the jailer leave with him, but when they stop at an island, Ariadne falls asleep and Theseus leaves her there, taking off with Phaedra. Egeus drowns, Araidne complains in Ovidian terms. • PHILOMELA (165) Tereus—subject of an opening complaint—marries Procne, who longs to see her sister; Tereus agrees to return to Athens to get her, and he and Philomela convince her father to let her go; on the voyage Tereus conceives a lust for her, so spirits her to a cave, where he rapes her and cuts out her tongue. He returns to Procne and announces he found her sister dead in Athens; menawhile, Philomela, who can’t write, nevertheless weaves her story into a tapestry that she manages to send to Procne, and the sisters are reunited; the narrator omits the rest. • PHYLLIS (167) Demophon, wretched son of wretched Theseus, returning from Troy, is blown ashore at Rhodopeya, where he meets Phyllis, daughter of Lycurgus, and promises to wed her; when he doesn’t return from Athens, she hangs herself. Long excerpts from her accusing letter make up the end of the tale. • HYPERMNESTRA (161) Lyno, son of Danao, and Hypermnestra, daughter of Lyno’s brother Egistus, are to be married (despite her bad horoscope); the night of the wedding, Egistus tells her to kill her husband (because of a prophecy), lest she be killed instead. She can’t do it, out of wifely duty, so she wakes him and they try to escape together, but he’s too fast, she’s caught and imprisoned, and the tale ends abruptly…

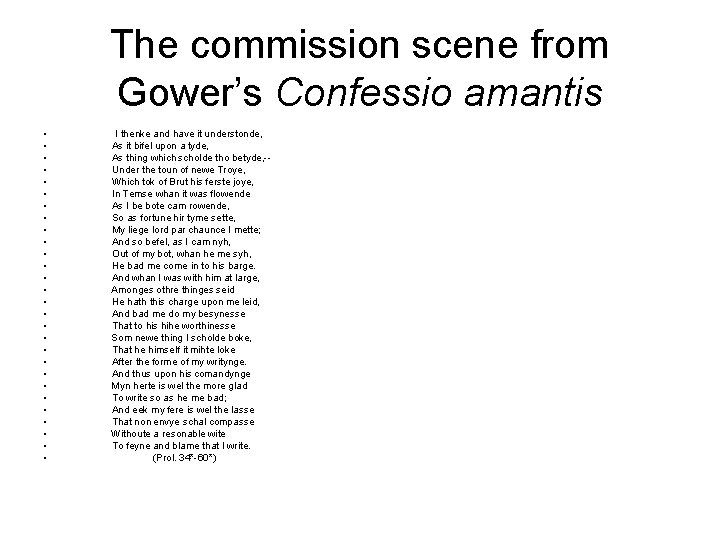

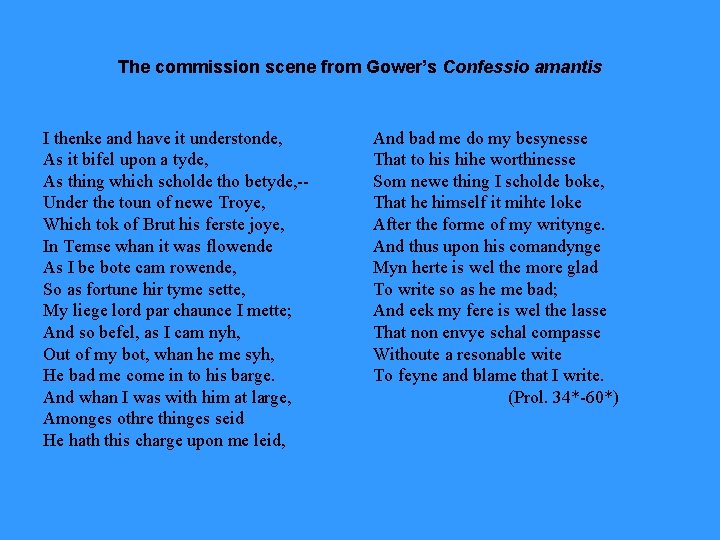

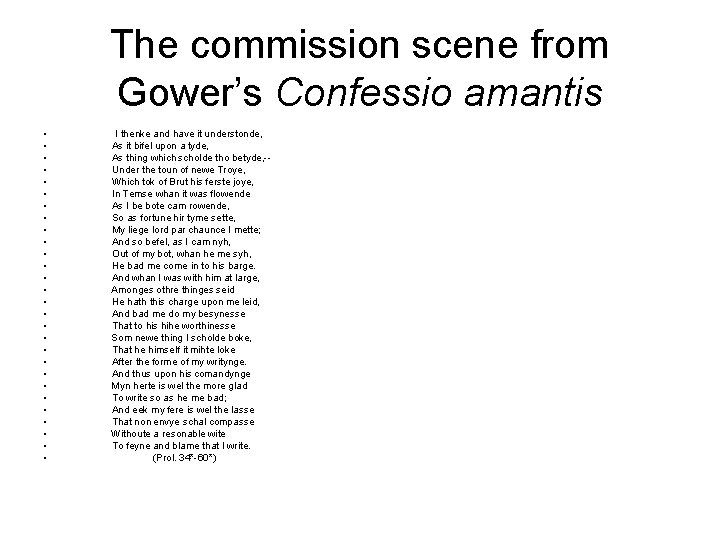

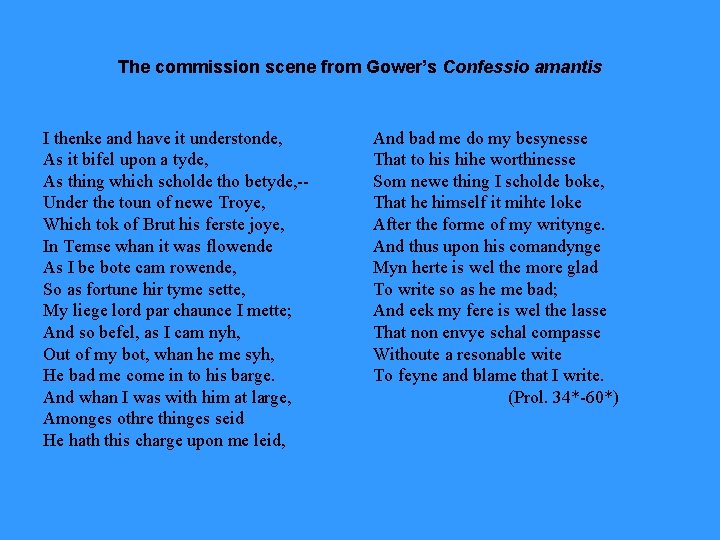

The commission scene from Gower’s Confessio amantis • • • • • • • I thenke and have it understonde, As it bifel upon a tyde, As thing which scholde tho betyde, -Under the toun of newe Troye, Which tok of Brut his ferste joye, In Temse whan it was flowende As I be bote cam rowende, So as fortune hir tyme sette, My liege lord par chaunce I mette; And so befel, as I cam nyh, Out of my bot, whan he me syh, He bad me come in to his barge. And whan I was with him at large, Amonges othre thinges seid He hath this charge upon me leid, And bad me do my besynesse That to his hihe worthinesse Som newe thing I scholde boke, That he himself it mihte loke After the forme of my writynge. And thus upon his comandynge Myn herte is wel the more glad To write so as he me bad; And eek my fere is wel the lasse That non envye schal compasse Withoute a resonable wite To feyne and blame that I write. (Prol. 34*-60*)

The commission scene from Gower’s Confessio amantis I thenke and have it understonde, As it bifel upon a tyde, As thing which scholde tho betyde, -Under the toun of newe Troye, Which tok of Brut his ferste joye, In Temse whan it was flowende As I be bote cam rowende, So as fortune hir tyme sette, My liege lord par chaunce I mette; And so befel, as I cam nyh, Out of my bot, whan he me syh, He bad me come in to his barge. And whan I was with him at large, Amonges othre thinges seid He hath this charge upon me leid, And bad me do my besynesse That to his hihe worthinesse Som newe thing I scholde boke, That he himself it mihte loke After the forme of my writynge. And thus upon his comandynge Myn herte is wel the more glad To write so as he me bad; And eek my fere is wel the lasse That non envye schal compasse Withoute a resonable wite To feyne and blame that I write. (Prol. 34*-60*)

Gret 05

Gret 05 Define gret

Define gret Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Frameset trong html5

Frameset trong html5 Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Chó sói

Chó sói Tư thế worms-breton

Tư thế worms-breton Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng bóng

Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng bóng Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

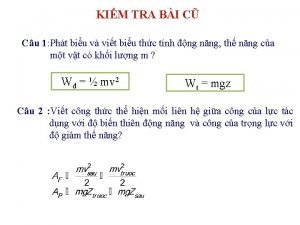

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Công thức tiính động năng

Công thức tiính động năng Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư tọa độ 5x5

Mật thư tọa độ 5x5 Phép trừ bù

Phép trừ bù Phản ứng thế ankan

Phản ứng thế ankan Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật

Thơ thất ngôn tứ tuyệt đường luật Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra Một số thể thơ truyền thống

Một số thể thơ truyền thống Cái miệng nó xinh thế

Cái miệng nó xinh thế Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau

Vẽ hình chiếu vuông góc của vật thể sau