Dangerous Medication Events To err is human to

- Slides: 31

Dangerous Medication Events ‘To err is human; to fail to learn is inexcusable’ Susan Sheridan, Vice President, Consumers Advancing Patient Safety, 2004. Kirk Lalwani, MD, FRCA, MCR Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon, U. S. A. Updated 5/2017

Disclosure The author has no conflict of interest or disclosures.

Objectives List the different types of dangerous medication events. Distinguish between adverse drug events (ADEs), adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and medication errors (MEs). Describe current models for analyzing errors in clinical medicine Assess the scope of the problem of medication errors (MEs), especially in pediatric populations. List strategies to minimize medication errors in anesthesia practice.

Dangerous Medication Events or Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) Medication Errors (MEs)

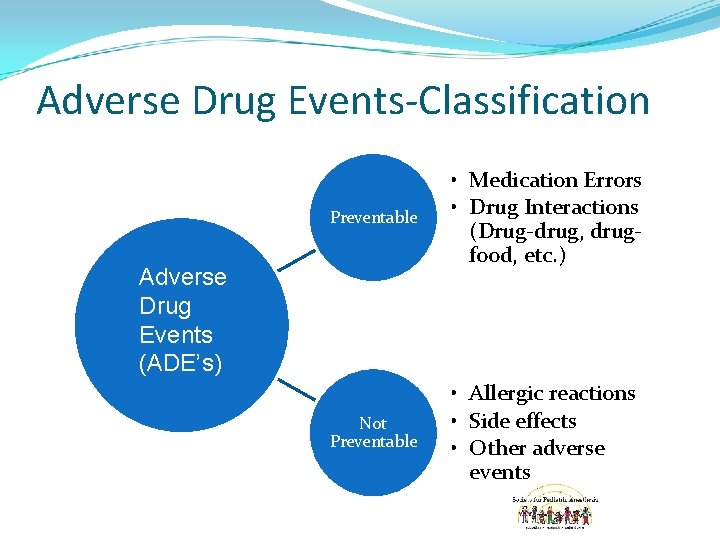

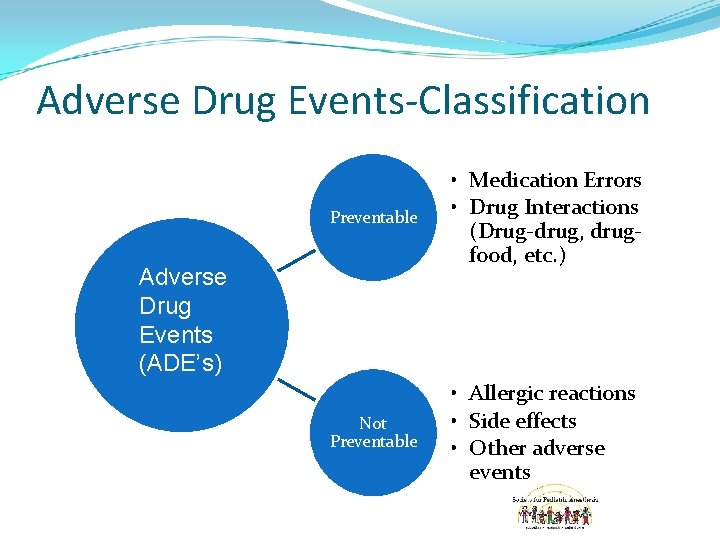

Adverse Drug Events-Classification Preventable • Medication Errors • Drug Interactions (Drug-drug, drugfood, etc. ) Not Preventable • Allergic reactions • Side effects • Other adverse events Adverse Drug Events (ADE’s)

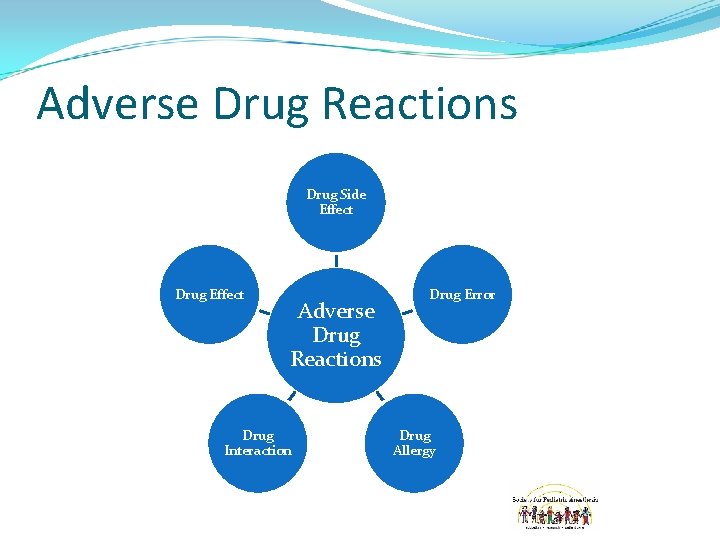

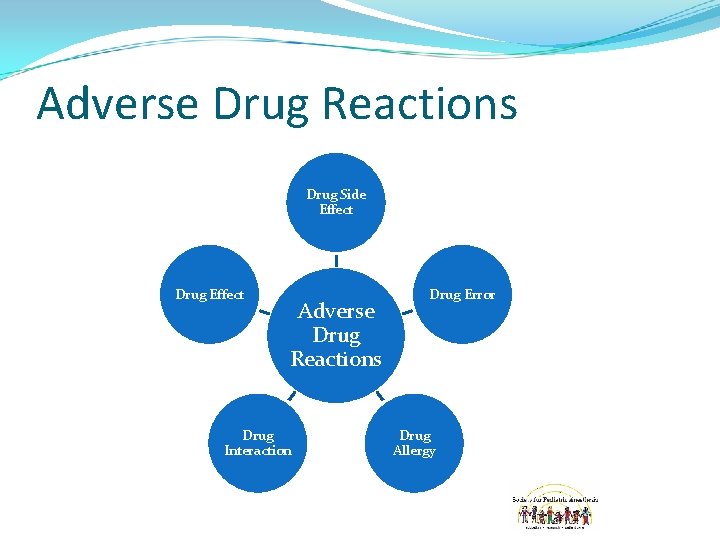

Adverse Drug Reactions Drug Side Effect Drug Effect Adverse Drug Reactions Drug Interaction Drug Error Drug Allergy

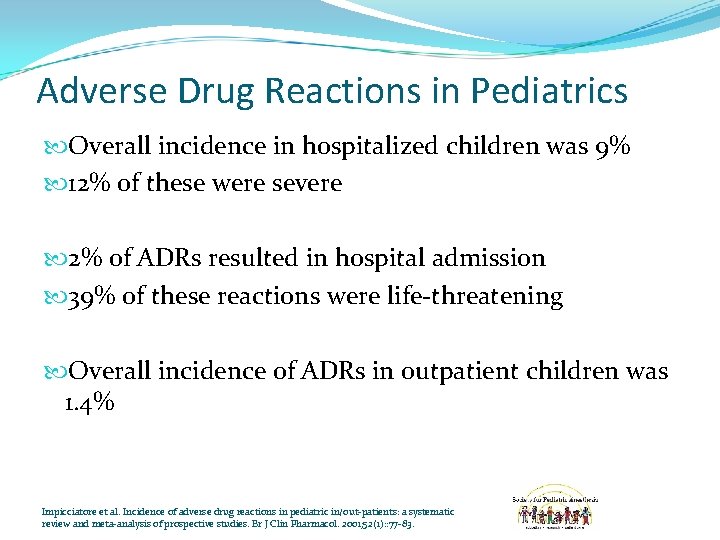

Adverse Drug Reactions in Pediatrics Overall incidence in hospitalized children was 9% 12% of these were severe 2% of ADRs resulted in hospital admission 39% of these reactions were life-threatening Overall incidence of ADRs in outpatient children was 1. 4% Impicciatore et al. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in pediatric in/out-patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001; 52(1): : 77 -83.

Models of Human Error Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model of Accident Causation Complex systems have barriers to protect against human error (alarms, protocols for double-checking, checklists, etc. ) Each barrier is like a slice of Swiss cheese (with holes in it) Each barrier has defects (holes in the cheese) often called ‘latent errors’ that are continually shifting Latent errors provide a route for active errors to penetrate the system’s defenses or barriers An active failure or error combined with latent errors allow a hazard to result in an accident Accidents typically occur as a result of the convergence of several latent and active errors as successive layers of barriers are breached A ‘near-miss’ event then converts to an ‘accident’ or ‘adverse event’ Reason et al. Diagnosing ‘vulnerable system syndrome': an essential prerequisite to effective risk management. Qual Health Care 2001; 10(Suppl II): ii 21 -5.

Models of Human Error The ‘Human Factors’ Approach Modern approach Less focus on the individual who made the error More on the pre-existing organizational factors Active failures Actions- picking up the wrong syringe, mislabeling a syringe etc Cognitive factors- memory lapses Violations- deviations from safe practice or protocols Latent failures Heavy workload Stressful environment Inadequate communication Inadequate maintenance of equipment Rapid organizational change Inadequate knowledge or experience Inadequate supervision Vincent et al. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ 1998: 316; 1154 -7.

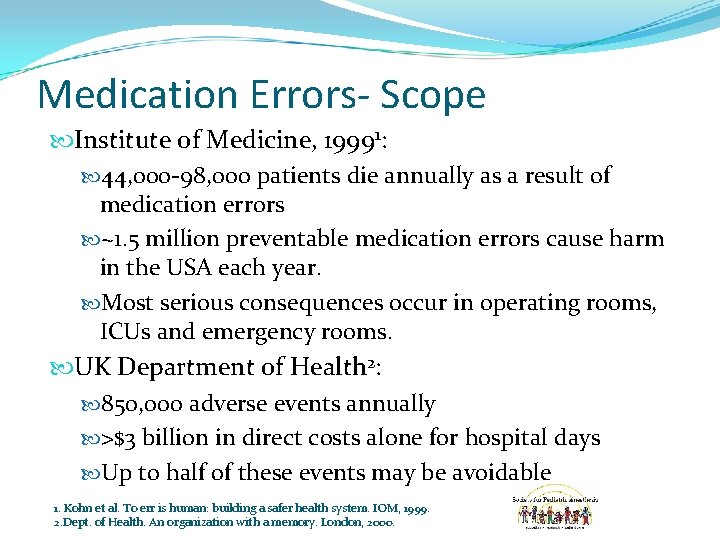

Medication Errors- Scope Institute of Medicine, 19991: 44, 000 -98, 000 patients die annually as a result of medication errors ~1. 5 million preventable medication errors cause harm in the USA each year. Most serious consequences occur in operating rooms, ICUs and emergency rooms. UK Department of Health 2: 850, 000 adverse events annually >$3 billion in direct costs alone for hospital days Up to half of these events may be avoidable 1. Kohn et al. To err is human: building a safer health system. IOM, 1999. 2. Dept. of Health. An organization with a memory. London, 2000.

Medication Error- Definition Any preventable event that may cause, or lead to, inappropriate medication use or patient harm, while the medication is in the control of the healthcare professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing, order communication, product labeling, packaging and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education’ monitoring; and use. National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 1996 (NCC MERP)

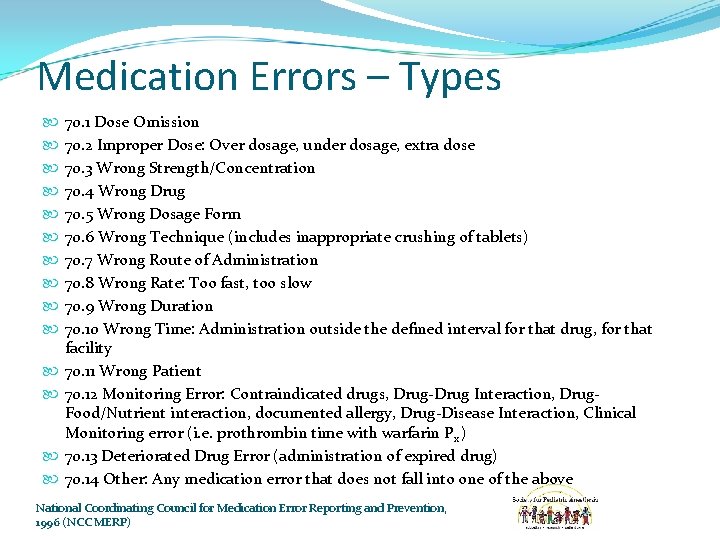

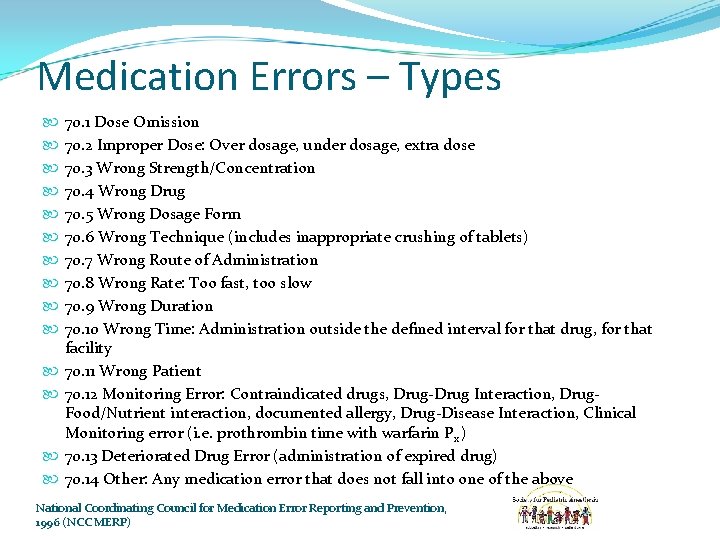

Medication Errors – Types 70. 1 Dose Omission 70. 2 Improper Dose: Over dosage, under dosage, extra dose 70. 3 Wrong Strength/Concentration 70. 4 Wrong Drug 70. 5 Wrong Dosage Form 70. 6 Wrong Technique (includes inappropriate crushing of tablets) 70. 7 Wrong Route of Administration 70. 8 Wrong Rate: Too fast, too slow 70. 9 Wrong Duration 70. 10 Wrong Time: Administration outside the defined interval for that drug, for that facility 70. 11 Wrong Patient 70. 12 Monitoring Error: Contraindicated drugs, Drug-Drug Interaction, Drug. Food/Nutrient interaction, documented allergy, Drug-Disease Interaction, Clinical Monitoring error (i. e. prothrombin time with warfarin Px ) 70. 13 Deteriorated Drug Error (administration of expired drug) 70. 14 Other: Any medication error that does not fall into one of the above National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 1996 (NCC MERP)

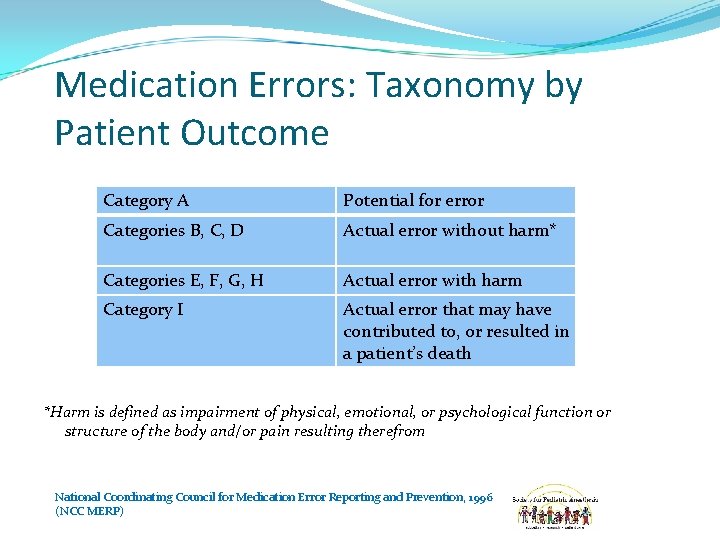

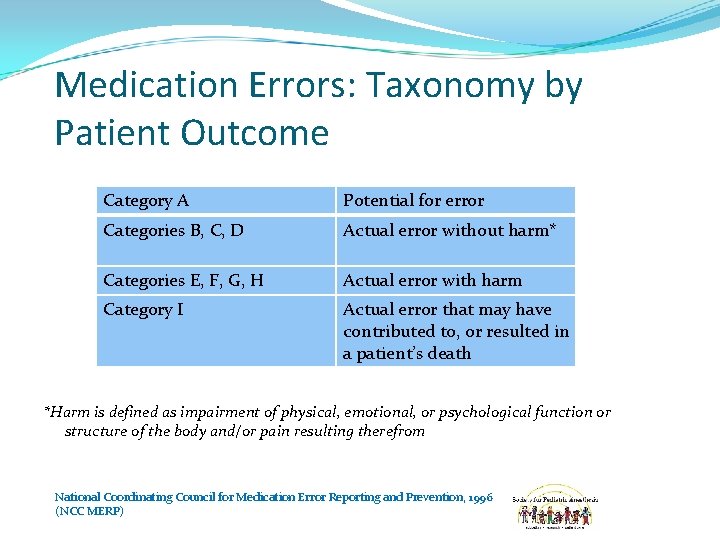

Medication Errors: Taxonomy by Patient Outcome Category A Potential for error Categories B, C, D Actual error without harm* Categories E, F, G, H Actual error with harm Category I Actual error that may have contributed to, or resulted in a patient’s death *Harm is defined as impairment of physical, emotional, or psychological function or structure of the body and/or pain resulting therefrom National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention, 1996 (NCC MERP)

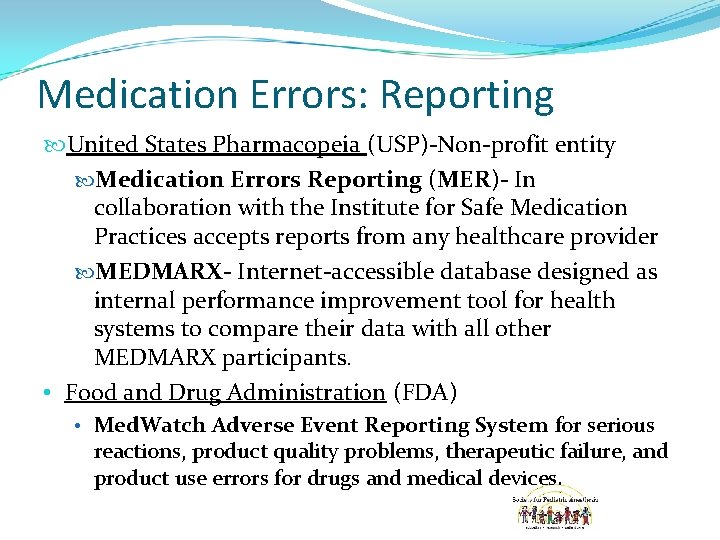

Medication Errors: Reporting United States Pharmacopeia (USP)-Non-profit entity Medication Errors Reporting (MER)- In collaboration with the Institute for Safe Medication Practices accepts reports from any healthcare provider MEDMARX- Internet-accessible database designed as internal performance improvement tool for health systems to compare their data with all other MEDMARX participants. • Food and Drug Administration (FDA) • Med. Watch Adverse Event Reporting System for serious reactions, product quality problems, therapeutic failure, and product use errors for drugs and medical devices.

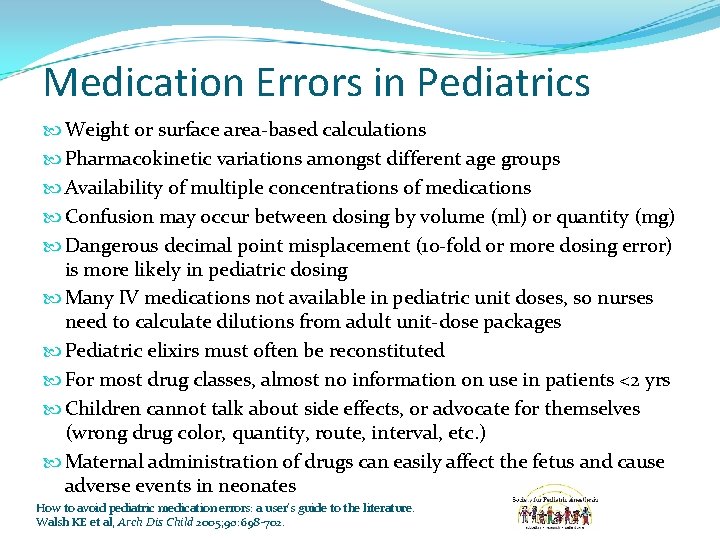

Medication Errors in Pediatrics Weight or surface area-based calculations Pharmacokinetic variations amongst different age groups Availability of multiple concentrations of medications Confusion may occur between dosing by volume (ml) or quantity (mg) Dangerous decimal point misplacement (10 -fold or more dosing error) is more likely in pediatric dosing Many IV medications not available in pediatric unit doses, so nurses need to calculate dilutions from adult unit-dose packages Pediatric elixirs must often be reconstituted For most drug classes, almost no information on use in patients <2 yrs Children cannot talk about side effects, or advocate for themselves (wrong drug color, quantity, route, interval, etc. ) Maternal administration of drugs can easily affect the fetus and cause adverse events in neonates How to avoid pediatric medication errors: a user’s guide to the literature. Walsh KE et al, Arch Dis Child 2005; 90: 698 -702.

Medication Errors in Anesthesia Delivery of multiple potent drugs, often in rapid succession during high acuity situations 1 Providers have the unique responsibility of being responsible for the direct preparation, dosing, and delivery of medications to patients In contrast to inpatient prescribing, this scenario lacks safety mechanisms like pharmacist reviews of prescriptions, check by second provider etc. A survey of 687 anesthesiologists revealed 85% had a drug error or near-miss in clinical practice 2. 1. Hanna et al: Medication safety in the perioperative setting. Anesth Clin (2011) 135 -144. 2. Orser et al: Medication errors in anesthetic practice: a survey of 687 practitioners. Can J Anaesth 2001: 48: 139 -46.

Types of Medication Errors in Anesthesia ASA Closed-Claims Project 1 205 claims for drug errors (4% of all Closed Claims in 2003 report) 31%- incorrect dose 24% substitution 17% insertion 24% miscellaneous Webster et al, 20012 ~ 8000 anesthetics found 1 medication error in 133 anesthetics (0. 75%) 20% incorrect dosing 20% accidental substitutions 63% of all errors involved intravenous boluses These errors caused additional interventions and/or escalation of care No deaths or permanent morbidity 1. Bowdle TA. Drug administration errors from the ASA closed claims project. ASA Newslet 2003; 67: 11 -13. 2. Webster et al. The frequency and nature of drug administration error during anaesthesia. Anaesth Inten Care. 2001; 29494 -500

Common Drugs Implicated and Errors Anti-infective agents Electrolytes and fluids Analgesics and sedatives Insulin 4. 2% of reviewed reports were harmful (Categories E-I)* Commonest errors Improper dose/quantity Omission errors Prescribing errors Weight vs. volume errors (mg vs. ml) Infusion pump misprogramming (mg/kg/min instead of mg/kg/hr) Patient weight confusion (pounds instead of kilograms) Kaushal et al Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA 285, 2114 -20. *Hicks et al. Harmful medication errors in children: A 5 year analysis of the MEDMARX program. J Ped Nursing. 2006; 21: 290 -8

Heparin 3 rd most common implicated drug 1 Several high-profile heparin overdoses in babies. Indiana, 2006: 5 infants received heparin 10, 000 U/ml instead of 10 U/ml - 3 infants died 2 California, 2007: 3 infants received heparin 10, 000 U/ml instead of 10 U/ml, including the twins of a Hollywood celebrity – no lasting adverse effects 3 Pharmacy technicians had mistakenly restocked the clinical care areas with 1000 x more concentrated heparin Both concentrations of heparin had similar labels. Baxter has since repackaged them with different labels 1. Hicks et al. Harmful medication errors in children: A 5 year analysis of the MEDMARX program. J Ped Nursing. 2006; 21: 290 -8. 2. Supporting Staff Recovery and Reintegration After a Critical Incident Resulting in Infant Death. Roesler, R, Ward D, Short M. Adv. Neonatal Care. 2009: 9(4); 163– 171. 3. Another heparin error: Learning from mistakes so we don't repeat them. Institute for Safe Medication Practices Medication Safety Alert, 2007: Nov. 29. http: //www. ismp. org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20071129. asp (accessed 4/27/11).

ADEs in Pediatric Sedation In a landmark study of adverse events in pediatric sedation settings, the conclusions were: Frequent drug overdoses and interactions, especially when 3 or more drugs were used ADEs associated with all routes of administration Patients receiving drugs with long half-lives may benefit from a prolonged period of observation ADEs occurred when sedation was administered outside the safety net of medical supervision Uniform monitoring and training standards required regardless of subspecialty or venue Standards of care, scope of practice, resource management, and reimbursement should be based on depth of sedation achieved (vigilance and resuscitation skills required) Cote et al. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: analysis of medications sued for sedation. Pediatrics. 2000 Oct; 106(4): 633 -44

Safety Goals and Recommendations The Joint Commission For Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (TJC)1 Instructs providers to ‘label all medications, medication containers, or other solutions on and off the sterile field’ Frequent cause of citations on JCAHO surveys Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF, 2010)2 New paradigm based on label formatting and careful reading of labels STPC Paradigm- Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy, and Culture Suyderhoud JP. JCAHO requirements and syringe labeling systems Anesth Analg 2007; 104: 242 1. 2. Eichhorn JH. APSF hosts medication safety conference: APSF newsletter 2010; 25: 1 -20.

APSF: STPC Standardization High alert drugs should be made by pharmacy Ready-to-use form appropriate for adults and/or kids Infusion pumps with drug libraries must be used Standardized fully compliant labels Technology Every location should have bar code readers to identify medications and a way to provide feedback, documentation and computerized decision support, i. e. anesthesia information systems Pharmacy Provider prepared medications should be discontinued in favor of preprepared kits. Clinical pharmacists should be part of the perioperative team Culture Establish a culture of education, accountability and error reporting with discussion of lessons learned.

American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Drugs and Committee on Hospital Care Policy Statement: ‘Prevention of Medication Errors in the Pediatric Inpatient Setting’ Detailed evidence-based recommendations to prevent medication errors, and education about medication errors for: Hospitals and organizations Prescribers Pharmacy staff Nursing staff Patients and families Stucky ER. Pediatrics 2003; 112(2): 431 -436.

Prevention of Medication Errors Presence of Clinical Pharmacists to Monitor Medication Orders (Ordering, Transcribing, and Administering) Ordering alone- Error rate reduction of 58% Transcribing and administering- additional 25% reduction Monitoring of all 3 functions- 81% error rate reduction Fortescue et al. Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 722 -729.

Prevention of Medication Errors Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE) with Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) Basic CPOE (ensures legibility and complete orders) prevented 65% of errors When CDSS added to CPOE, error reduction rate was 72% Fortescue et al. Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 722 -729.

Prevention of Medication Errors Improved Communication Between Healthcare Practitioners Specifically, physician-pharmacist communication could have prevented 47% of all medication errors Physician-nurse communication (i. e. nursing involvement in physician rounds) – 17% error reduction Fortescue et al. Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 722 -729

Prevention of Medication Errors 3 Strategies Combined (Presence of Clinical Pharmacists, CPOE with CDSS, and Improved Communication) Prevention of 98. 5% of medication errors Potentially harmful medication errors- 3 strategies combined could have prevented 96. 7% of errors Fortescue et al. Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 722 -729

Prevention of Medication Errors in Anesthesia The label on any ampule or syringe should be read carefully before drawing it up. Legibility and contents of labels should be optimized according to agreed standards. Syringes should always be labeled Formal organization of drug drawers and workspaces should be used Labels should be checked with a second person or device (e. g. barcode reader) before drug is drawn up or administered Avoidance of similar packaging and presentation of drugs Errors should be reported and reviewed for continuous quality improvement purposes Hanna et al: Medication safety in the perioperative setting. Anesth Clin (2011) 135 -144. Jensen et al. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2004; 59: 493 -504

Prevention of Medication Errors in Anesthesia: The Role of Technology Automated Anesthesia Information Management Systems (AIMS) CPOE with CDSS Prefilled, automated medication syringes (Intelli. Fill IV System, FHT Inc, USA) Automated ampule opening and syringe-labeling device (SAFERamp, Cambridge Enterprise, Ltd. , UK) Bar-coded labels with drug information, visual and auditory confirmation, and automated recording on the electronic record (SAFERsleep system, Safer Sleep Inc. , USA) Docu. Sys- Computerized interface for medication management and narcotic tracking with decision support (Docu. Sys Inc, Georgia, USA) Safe Label System (Codonics Inc. , Ohio, USA)- Barcode identification and labeling with safety checks, confirmation and label printing Hanna et al: Medication safety in the perioperative setting. Anesth Clin (2011) 135 -144.

Communication with the Family Patients unanimously desire to be told about any error that caused them harm Present results of how the incident occurred Thorough apology Information on how these events will be prevented in future No evidence to suggest full disclosure results in increased liability payments Disclosure by professionals more likely if they feel supported by organization Dissemination of findings to family and wider audience, i. e. other institutions/units nationally and internationally Stebbing et al. The role of communication in paediatric drug safety. Arch Dis Child 2007; 92: 440 -45.

Summary ADEs can be classified as preventable or non-preventable Children are at increased risk for medication errors as a result of several factors Anesthesia practice is a high-risk setting for medication errors Providers can utilize simple strategies to minimize the potential for medication errors. Adoption of technologies that decrease medication error is essential to make hospitals safer for patients Organizational culture must support and encourage the reporting of errors as a quality improvement tool A policy of full disclosure of errors to patients and family must occur at an organizational level Despite adoption of all measures, it is likely that we are a long way from achieving a zero-incidence of medication errors in clinical care