AgitationSedation 2018 SCCM Clinical Practice Guidelines for the

- Slides: 27

Agitation/Sedation 2018 SCCM Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU

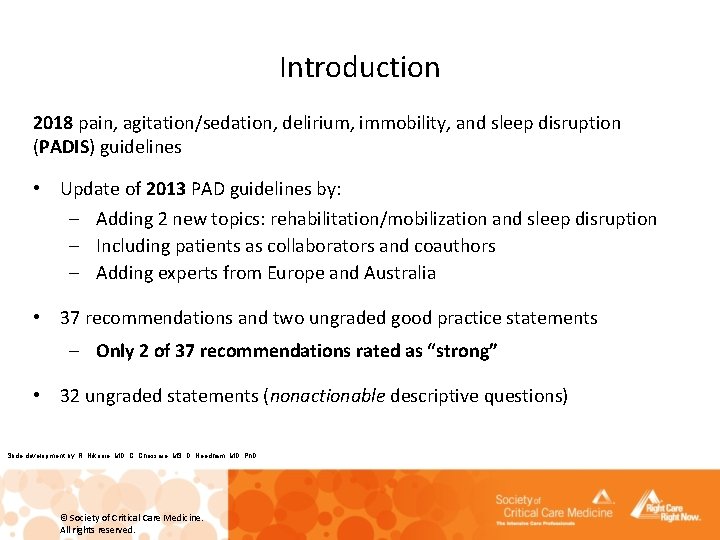

Introduction 2018 pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption (PADIS) guidelines • Update of 2013 PAD guidelines by: – Adding 2 new topics: rehabilitation/mobilization and sleep disruption – Including patients as collaborators and coauthors – Adding experts from Europe and Australia • 37 recommendations and two ungraded good practice statements – Only 2 of 37 recommendations rated as “strong” • 32 ungraded statements (nonactionable descriptive questions) Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

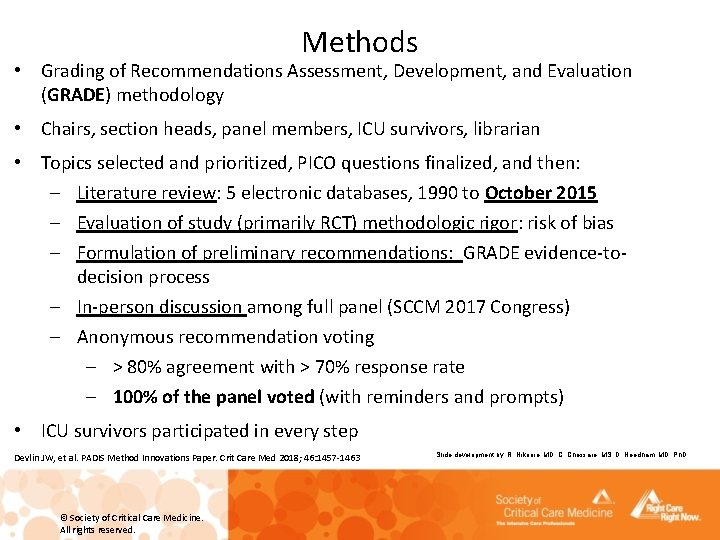

Methods • Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology • Chairs, section heads, panel members, ICU survivors, librarian • Topics selected and prioritized, PICO questions finalized, and then: – Literature review: 5 electronic databases, 1990 to October 2015 – Evaluation of study (primarily RCT) methodologic rigor: risk of bias – Formulation of preliminary recommendations: GRADE evidence-todecision process – In-person discussion among full panel (SCCM 2017 Congress) – Anonymous recommendation voting – > 80% agreement with > 70% response rate – 100% of the panel voted (with reminders and prompts) • ICU survivors participated in every step Devlin JW, et al. PADIS Method Innovations Paper. Crit Care Med 2018; 46: 1457 -1463 © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D

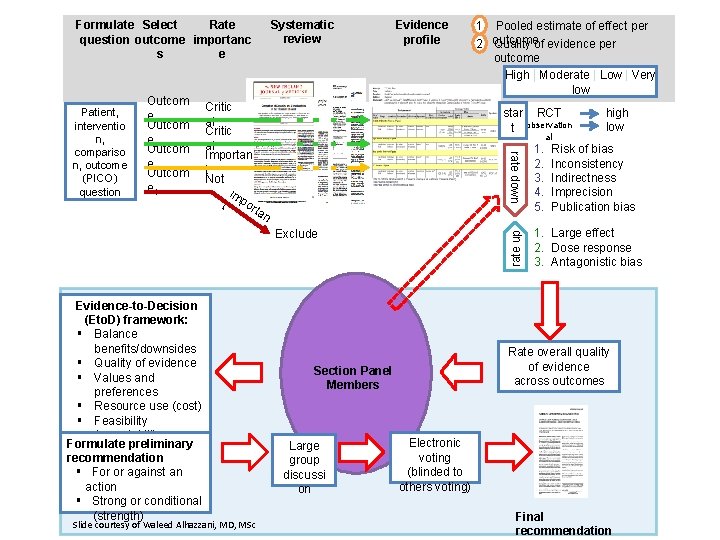

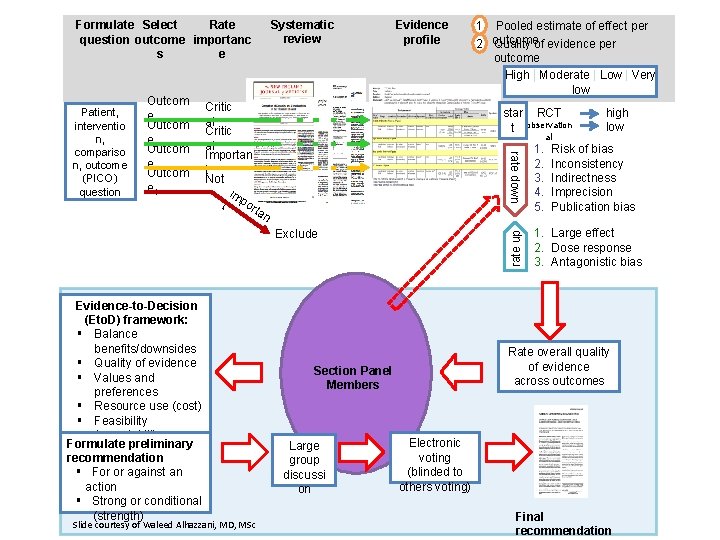

Systematic review Formulate Select Rate question outcome importanc s e Critic al Importan t Not im t port a star RCT t observation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 1. Large effect 2. Dose response 3. Antagonistic bias n Exclude al high low rate up Outcom e 1 Outcom e 2 Outcom e 3 Outcom e 4 1 Pooled estimate of effect per Quality of evidence per 2 outcome High | Moderate| Low | Very low Low Very low rate down Patient, interventio n, compariso n, outcome (PICO) question Evidence profile Risk of bias Inconsistency Indirectness Imprecision Publication bias systematic review of evidence Evidence-to-Decision (Eto. D) framework: § Balance benefits/downsides § Quality of evidence § Values and preferences § Resource use (cost) § Feasibility § Acceptability Formulate preliminary recommendation § For or against an action § Strong or conditional (strength) Slide courtesy of Waleed Alhazzani, MD, MSc Rate overall quality of evidence across outcomes Section Panel Members Large group discussi on Electronic voting (blinded to others voting) Final recommendation

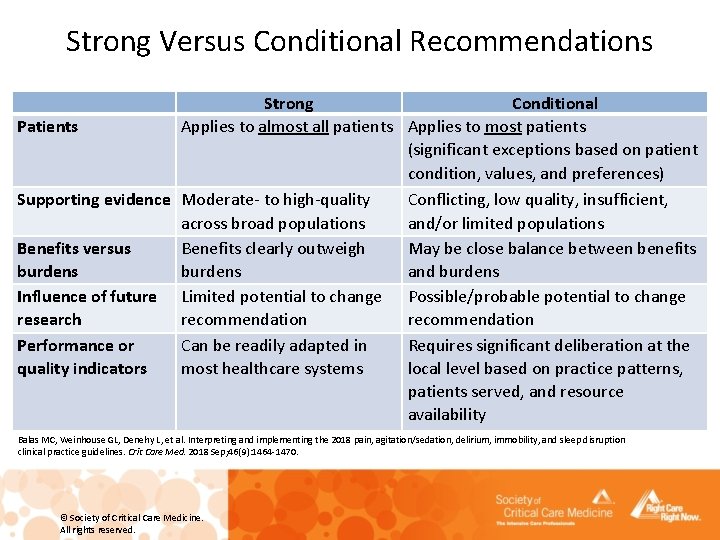

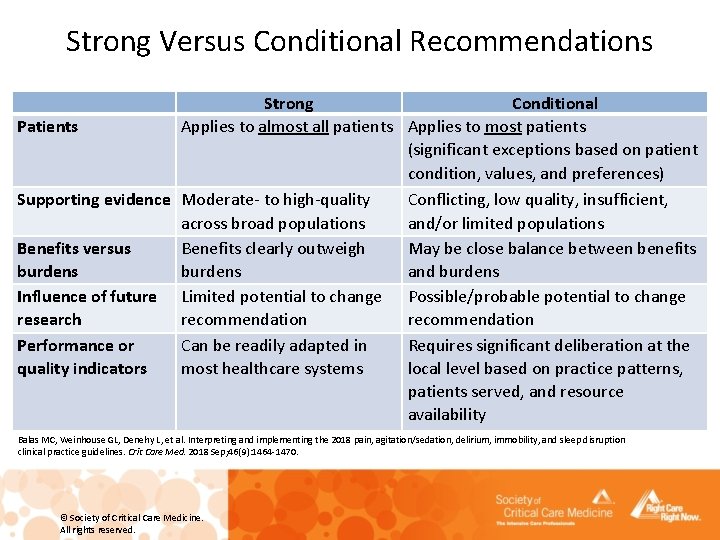

Strong Versus Conditional Recommendations Patients Strong Conditional Applies to almost all patients Applies to most patients (significant exceptions based on patient condition, values, and preferences) Supporting evidence Moderate- to high-quality Conflicting, low quality, insufficient, across broad populations and/or limited populations Benefits versus Benefits clearly outweigh May be close balance between benefits burdens and burdens Influence of future Limited potential to change Possible/probable potential to change research recommendation Performance or Can be readily adapted in Requires significant deliberation at the quality indicators most healthcare systems local level based on practice patterns, patients served, and resource availability Balas MC, Weinhouse GL, Denehy L, et al. Interpreting and implementing the 2018 pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption clinical practice guidelines. Crit Care Med. 2018 Sep; 46(9): 1464 -1470. © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

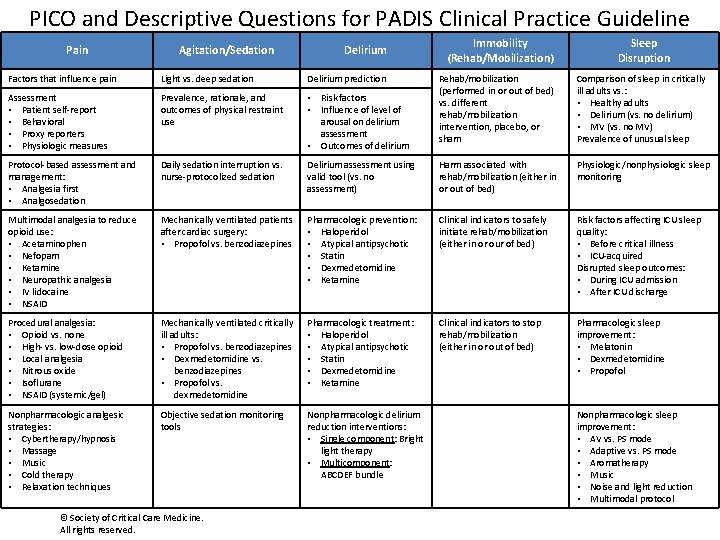

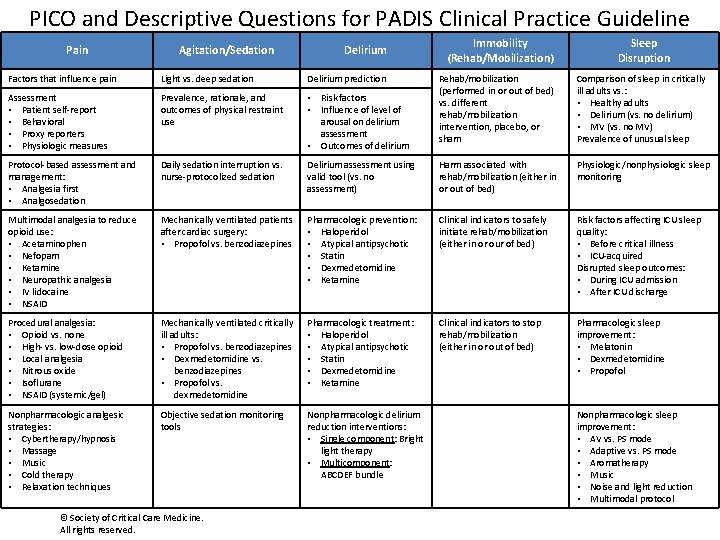

PICO and Descriptive Questions for PADIS Clinical Practice Guideline Pain Agitation/Sedation Delirium Immobility (Rehab/Mobilization) Sleep Disruption Rehab/mobilization (performed in or out of bed) vs. different rehab/mobilization intervention, placebo, or sham Comparison of sleep in critically ill adults vs. : • Healthy adults • Delirium (vs. no delirium) • MV (vs. no MV) Prevalence of unusual sleep Factors that influence pain Light vs. deep sedation Delirium prediction Assessment • Patient self-report • Behavioral • Proxy reporters • Physiologic measures Prevalence, rationale, and outcomes of physical restraint use • Risk factors • Influence of level of arousal on delirium assessment • Outcomes of delirium Protocol-based assessment and management: • Analgesia first • Analgosedation Daily sedation interruption vs. nurse-protocolized sedation Delirium assessment using valid tool (vs. no assessment) Harm associated with rehab/mobilization (either in or out of bed) Physiologic/nonphysiologic sleep monitoring Multimodal analgesia to reduce opioid use: • Acetaminophen • Nefopam • Ketamine • Neuropathic analgesia • IV lidocaine • NSAID Mechanically ventilated patients after cardiac surgery: • Propofol vs. benzodiazepines Pharmacologic prevention: • Haloperidol • Atypical antipsychotic • Statin • Dexmedetomidine • Ketamine Clinical indicators to safely initiate rehab/mobilization (either in or our of bed) Risk factors affecting ICU sleep quality: • Before critical illness • ICU-acquired Disrupted sleep outcomes: • During ICU admission • After ICU discharge Procedural analgesia: • Opioid vs. none • High- vs. low-dose opioid • Local analgesia • Nitrous oxide • Isoflurane • NSAID (systemic/gel) Mechanically ventilated critically ill adults: • Propofol vs. benzodiazepines • Dexmedetomidine vs. benzodiazepines • Propofol vs. dexmedetomidine Pharmacologic treatment: • Haloperidol • Atypical antipsychotic • Statin • Dexmedetomidine • Ketamine Clinical indicators to stop rehab/mobilization (either in or out of bed) Pharmacologic sleep improvement: • Melatonin • Dexmedetomidine • Propofol Nonpharmacologic analgesic strategies: • Cybertherapy/hypnosis • Massage • Music • Cold therapy • Relaxation techniques Objective sedation monitoring tools Nonpharmacologic delirium reduction interventions: • Single component: Bright light therapy • Multicomponent: ABCDEF bundle © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved. Nonpharmacologic sleep improvement: • AV vs. PS mode • Adaptive vs. PS mode • Aromatherapy • Music • Noise and light reduction • Multimodal protocol

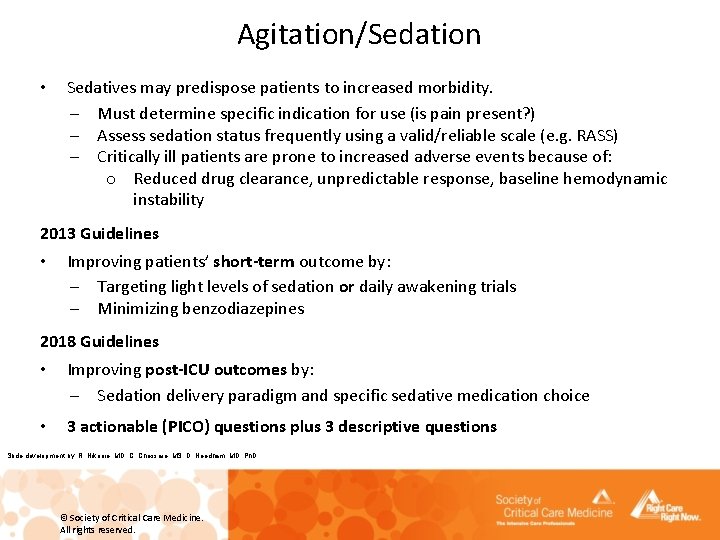

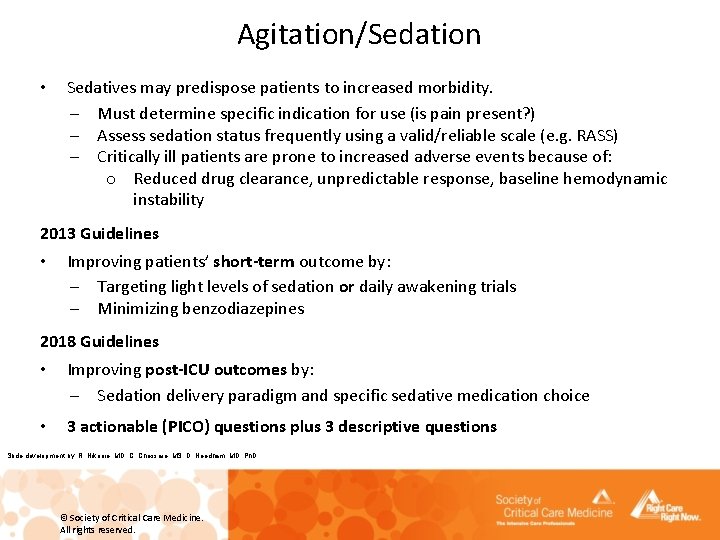

Agitation/Sedation • Sedatives may predispose patients to increased morbidity. – Must determine specific indication for use (is pain present? ) – Assess sedation status frequently using a valid/reliable scale (e. g. RASS) – Critically ill patients are prone to increased adverse events because of: o Reduced drug clearance, unpredictable response, baseline hemodynamic instability 2013 Guidelines • Improving patients’ short-term outcome by: – Targeting light levels of sedation or daily awakening trials – Minimizing benzodiazepines 2018 Guidelines • Improving post-ICU outcomes by: – Sedation delivery paradigm and specific sedative medication choice • 3 actionable (PICO) questions plus 3 descriptive questions Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

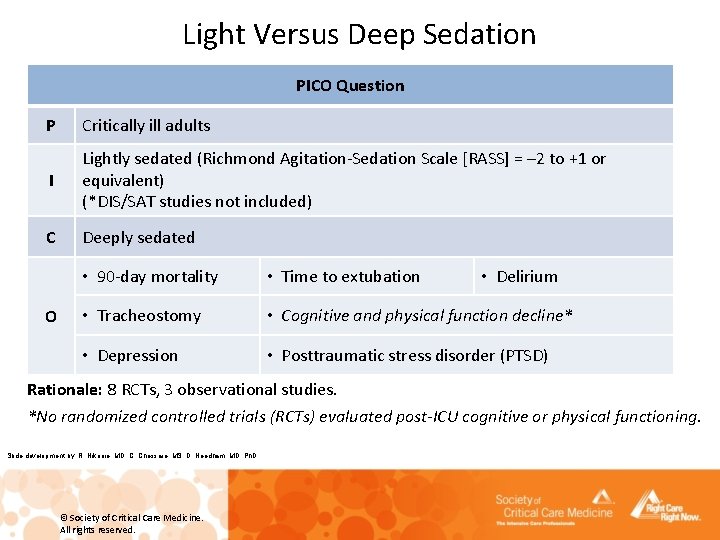

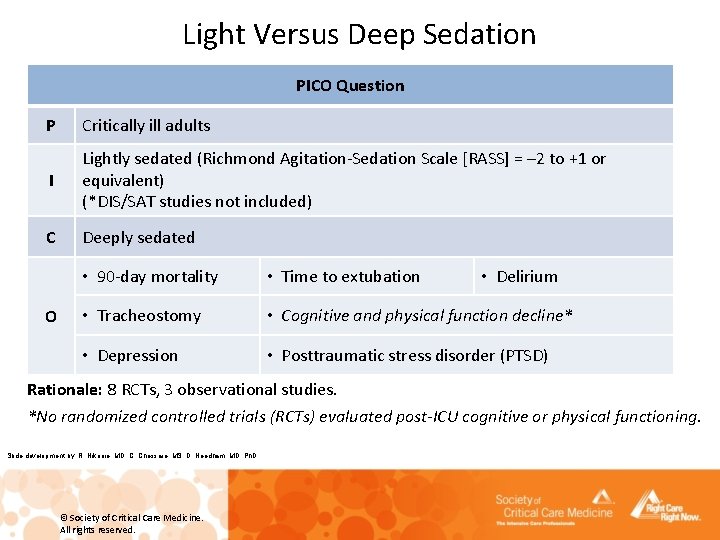

Light Versus Deep Sedation PICO Question P Critically ill adults I Lightly sedated (Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale [RASS] = – 2 to +1 or equivalent) (*DIS/SAT studies not included) C Deeply sedated O • 90 -day mortality • Time to extubation • Delirium • Tracheostomy • Cognitive and physical function decline* • Depression • Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Rationale: 8 RCTs, 3 observational studies. *No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluated post-ICU cognitive or physical functioning. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

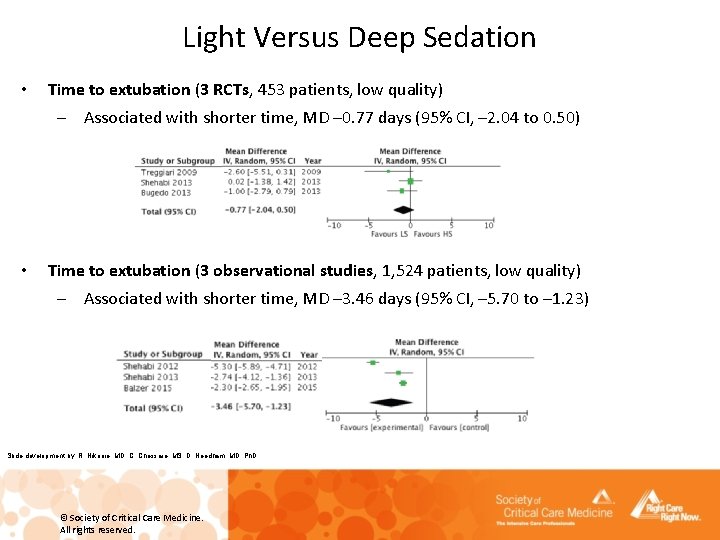

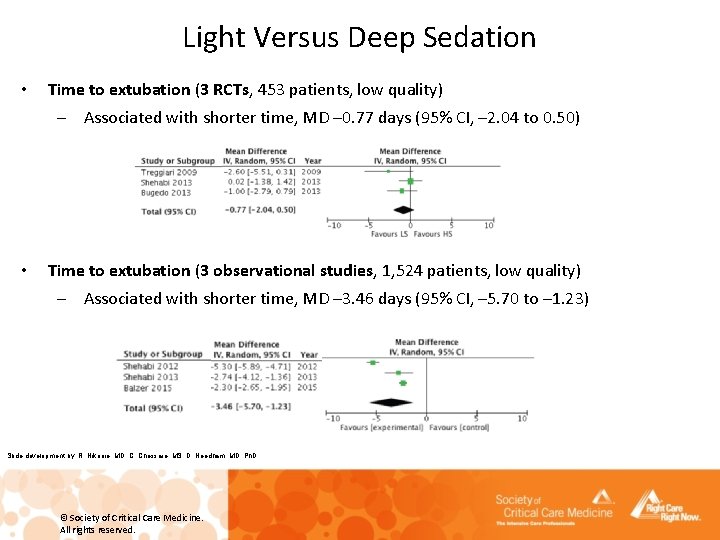

Light Versus Deep Sedation • Time to extubation (3 RCTs, 453 patients, low quality) – Associated with shorter time, MD – 0. 77 days (95% CI, – 2. 04 to 0. 50) • Time to extubation (3 observational studies, 1, 524 patients, low quality) – Associated with shorter time, MD – 3. 46 days (95% CI, – 5. 70 to – 1. 23) Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

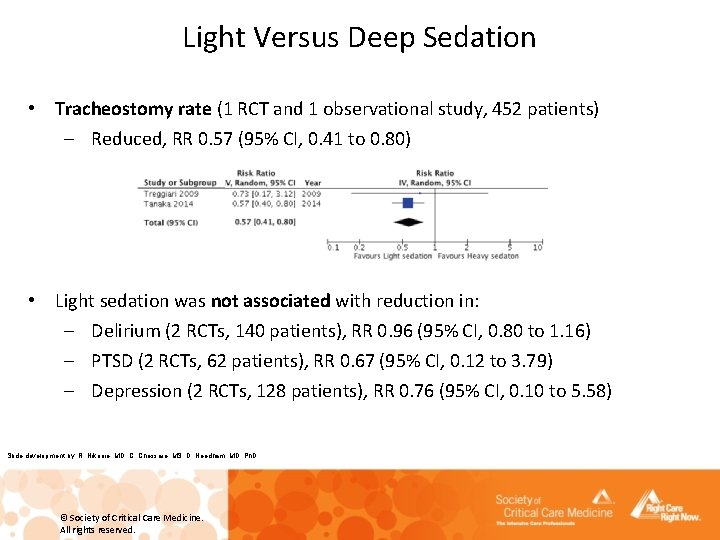

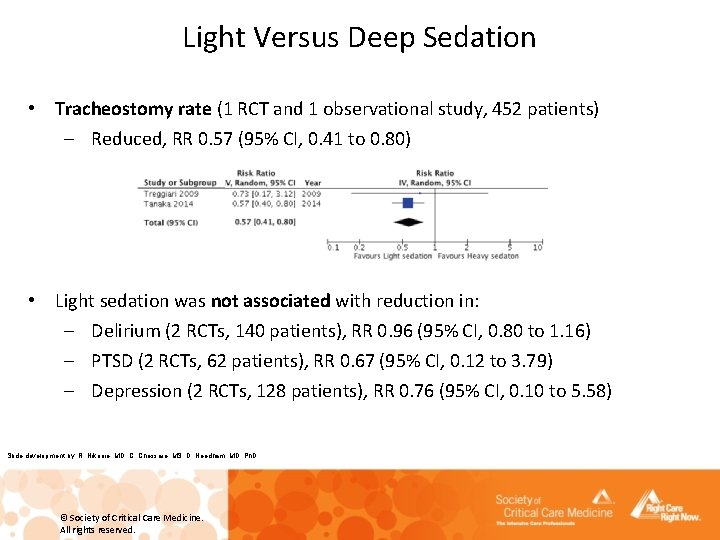

Light Versus Deep Sedation • Tracheostomy rate (1 RCT and 1 observational study, 452 patients) – Reduced, RR 0. 57 (95% CI, 0. 41 to 0. 80) • Light sedation was not associated with reduction in: – Delirium (2 RCTs, 140 patients), RR 0. 96 (95% CI, 0. 80 to 1. 16) – PTSD (2 RCTs, 62 patients), RR 0. 67 (95% CI, 0. 12 to 3. 79) – Depression (2 RCTs, 128 patients), RR 0. 76 (95% CI, 0. 10 to 5. 58) Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

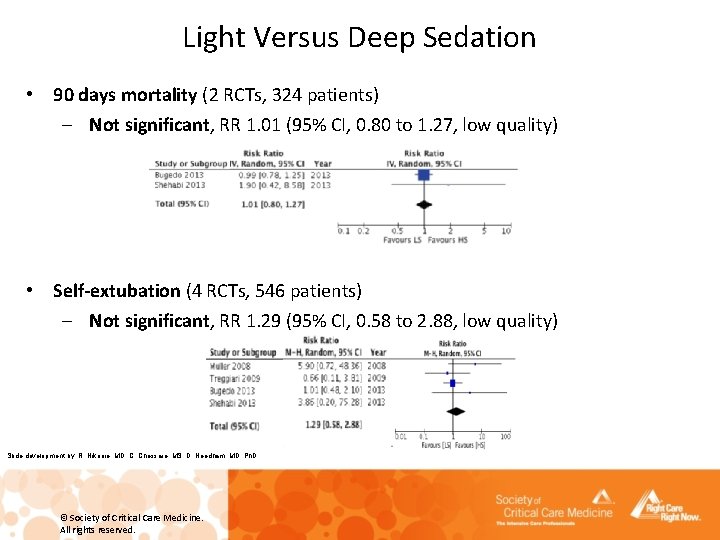

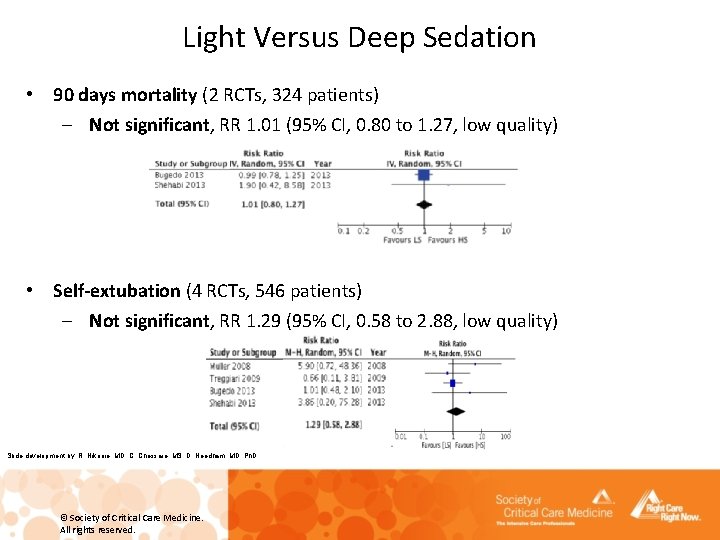

Light Versus Deep Sedation • 90 days mortality (2 RCTs, 324 patients) – Not significant, RR 1. 01 (95% CI, 0. 80 to 1. 27, low quality) • Self-extubation (4 RCTs, 546 patients) – Not significant, RR 1. 29 (95% CI, 0. 58 to 2. 88, low quality) Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

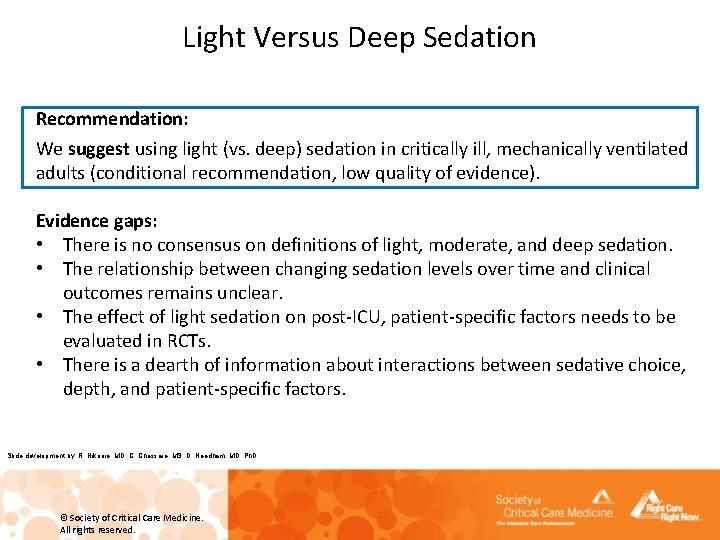

Light Versus Deep Sedation Recommendation: We suggest using light (vs. deep) sedation in critically ill, mechanically ventilated adults (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). Evidence gaps: • There is no consensus on definitions of light, moderate, and deep sedation. • The relationship between changing sedation levels over time and clinical outcomes remains unclear. • The effect of light sedation on post-ICU, patient-specific factors needs to be evaluated in RCTs. • There is a dearth of information about interactions between sedative choice, depth, and patient-specific factors. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Daily Sedation Interruption Versus Nurse-Protocolized Sedation Descriptive Question: In critically ill intubated adults, is there a difference between daily sedation interruption (DSI) protocols and nurse-protocolized targeted sedation in the ability to achieve and maintain a light level of sedation? A DSI or spontaneous awakening trial (SAT) is a period of time during which a patient’s sedative medication is discontinued so the patient can wake up and achieve arousal and/or alertness defined by objective actions (opening eyes in response to a voice, following simple commands, and/or RASS score of − 1 to +1. Nurse-protocolized targeted sedation is an an established protocol used by a bedside nurse to titrate sedatives to an established sedation goal. Note that the frequency of assessment and sedative titration often vary considerably. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Daily Sedation Interruption Versus Nurse-Protocolized Sedation Data: 5 unblinded RCTs compared DSI to either usual or nurse-protocolized targeted sedation (739 patients, usually a benzodiazepine with or without an opioid) – While differences exist among individual RCTs regarding the ability of DSI (vs. its comparator) to maintain light sedation, the overall ability of DSI and nurseprotocolized targeted sedation to achieve light sedation is similar. – Both DSI and nurse-protocolized targeted sedation are safe. Ungraded statement: DSI protocols and nurse-protocolized targeted sedation can achieve and maintain a light level of sedation. Evidence gaps: – Variability exists in nursing sedation assessment frequency and reporting. – Variability exists in sedative administrative routes among institutions. – Patient and family preferences and education should be considered. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

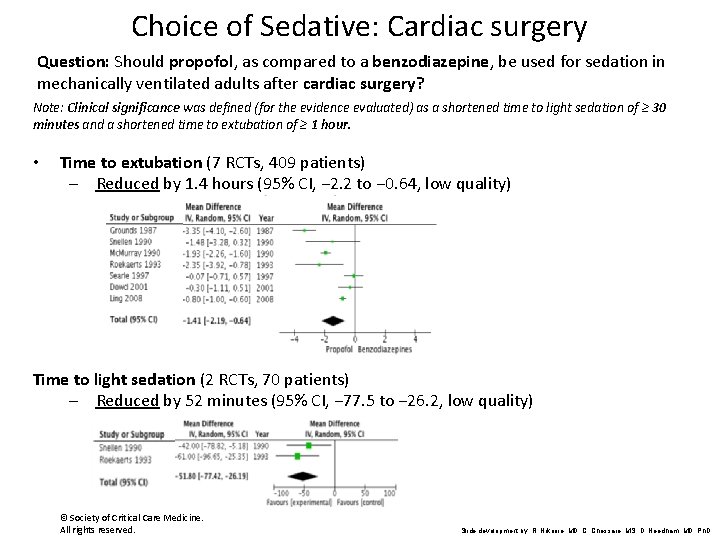

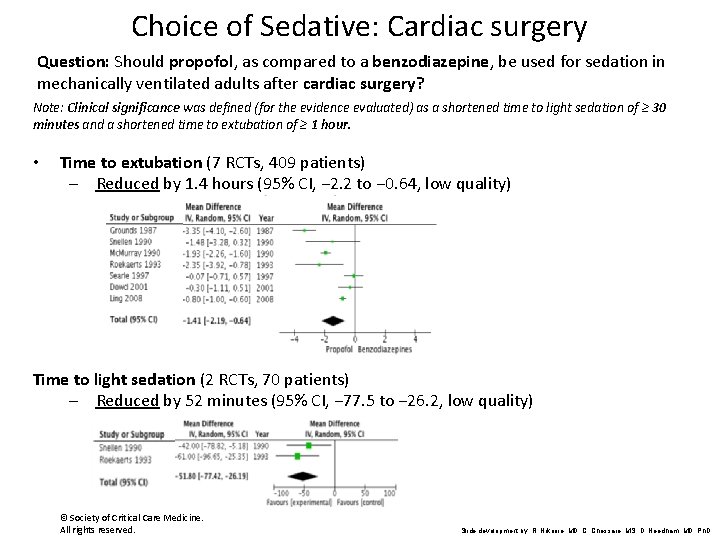

Choice of Sedative: Cardiac surgery Question: Should propofol, as compared to a benzodiazepine, be used for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults after cardiac surgery? Note: Clinical significance was defined (for the evidence evaluated) as a shortened time to light sedation of ≥ 30 minutes and a shortened time to extubation of ≥ 1 hour. • Time to extubation (7 RCTs, 409 patients) – Reduced by 1. 4 hours (95% CI, − 2. 2 to − 0. 64, low quality) Time to light sedation (2 RCTs, 70 patients) – Reduced by 52 minutes (95% CI, − 77. 5 to − 26. 2, low quality) © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D

Choice of Sedative: Cardiac surgery Recommendation: We suggest using propofol over a benzodiazepine for sedation in mechanically ventilated adults after cardiac surgery (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Choice of Sedative: Medical and Surgical Patients (Noncardiac Surgery) Question: For sedation in critically ill mechanically ventilated adults: 1. Should propofol, as compared to a benzodiazepine, be used? 2. Should dexmedetomidine, as compared to a benzodiazepine, be used? 3. Should dexmedetomidine, as compared to propofol, be used? Clinical significance was defined (for the evidence evaluated) as: • a shortened time to light sedation of ≥ 4 hours • a shortened time to extubation of ≥ 8 -12 hours (one nursing shift) Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

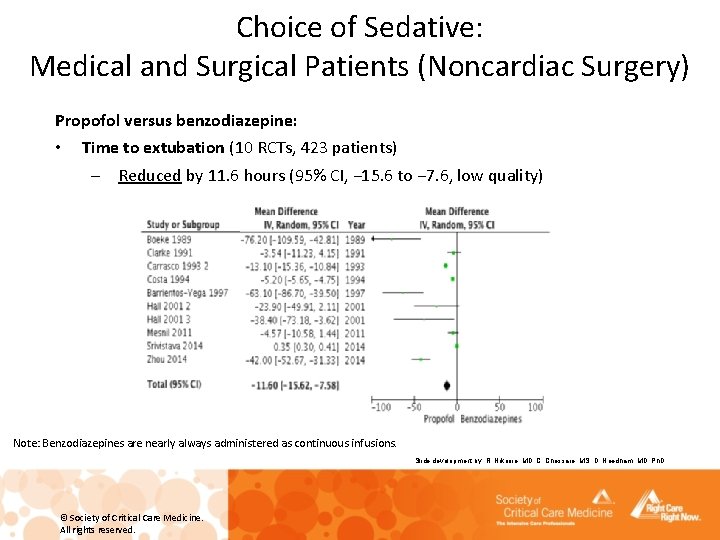

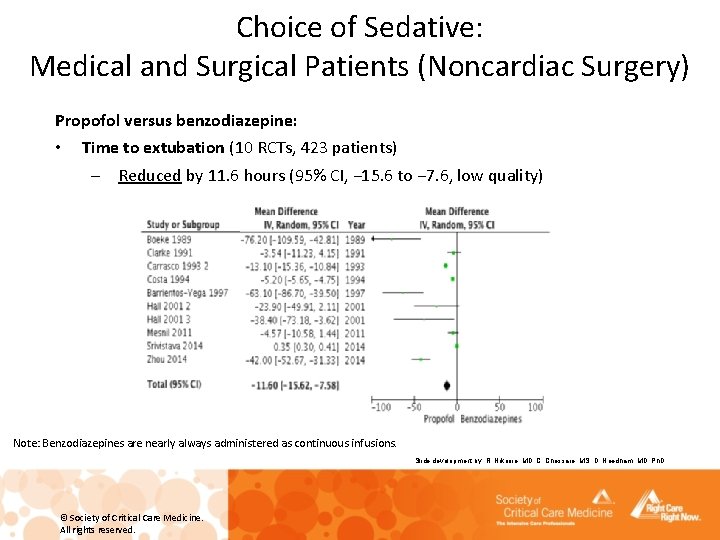

Choice of Sedative: Medical and Surgical Patients (Noncardiac Surgery) Propofol versus benzodiazepine: • Time to extubation (10 RCTs, 423 patients) – Reduced by 11. 6 hours (95% CI, − 15. 6 to − 7. 6, low quality) Note: Benzodiazepines are nearly always administered as continuous infusions. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

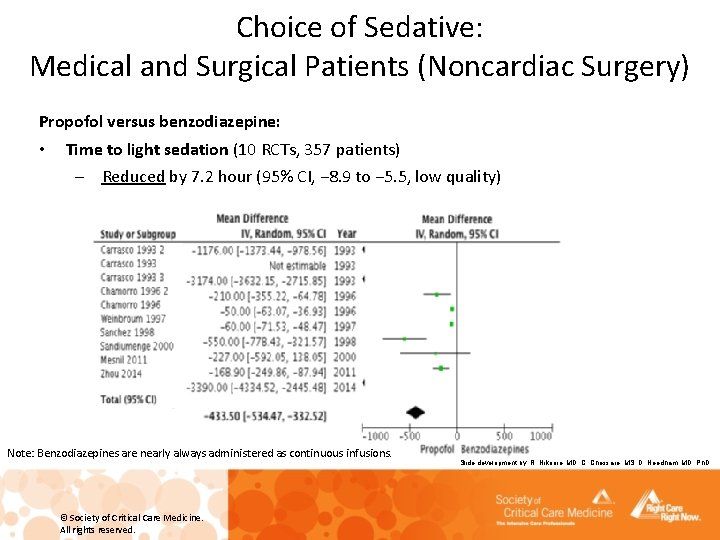

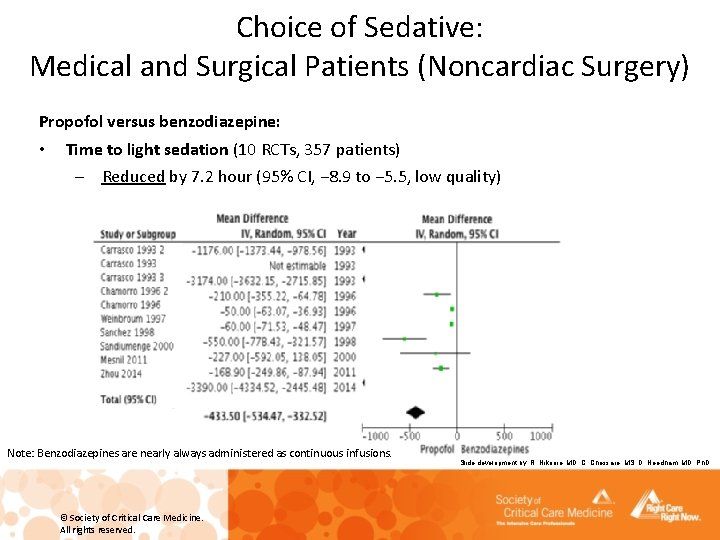

Choice of Sedative: Medical and Surgical Patients (Noncardiac Surgery) Propofol versus benzodiazepine: • Time to light sedation (10 RCTs, 357 patients) – Reduced by 7. 2 hour (95% CI, − 8. 9 to − 5. 5, low quality) Note: Benzodiazepines are nearly always administered as continuous infusions. © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D

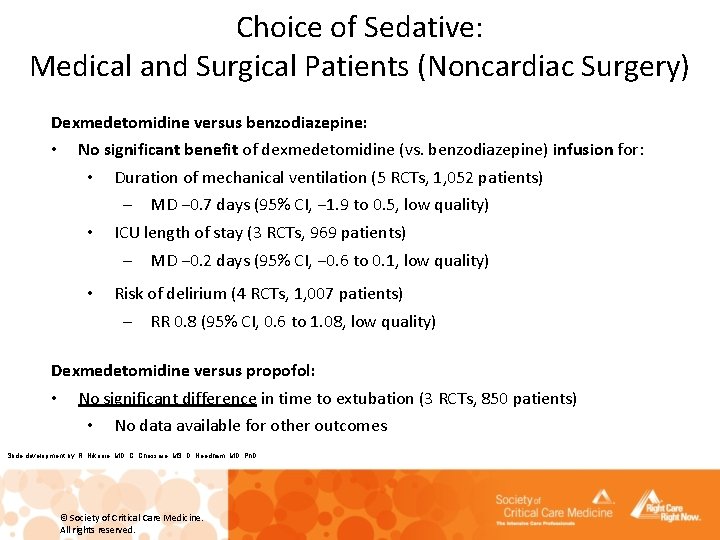

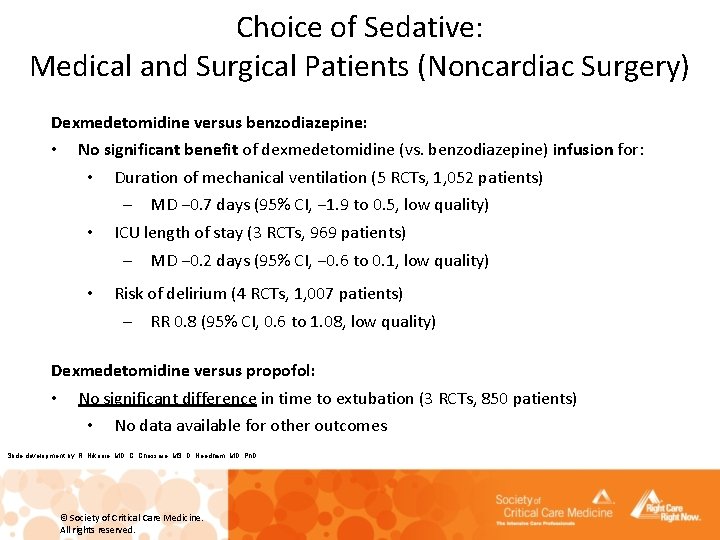

Choice of Sedative: Medical and Surgical Patients (Noncardiac Surgery) Dexmedetomidine versus benzodiazepine: • No significant benefit of dexmedetomidine (vs. benzodiazepine) infusion for: • Duration of mechanical ventilation (5 RCTs, 1, 052 patients) • – MD − 0. 7 days (95% CI, − 1. 9 to 0. 5, low quality) ICU length of stay (3 RCTs, 969 patients) – MD − 0. 2 days (95% CI, − 0. 6 to 0. 1, low quality) • Risk of delirium (4 RCTs, 1, 007 patients) – RR 0. 8 (95% CI, 0. 6 to 1. 08, low quality) Dexmedetomidine versus propofol: • No significant difference in time to extubation (3 RCTs, 850 patients) • No data available for other outcomes Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Recommendation: We suggest using either propofol or dexmedetomidine over benzodiazepines for sedation in critically ill mechanically ventilated adults (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). Evidence Gaps: • Effect of sedative choice on longer-term, patient-centered outcomes needs to be investigated; a reliance on evaluating faster extubation no longer suffices. • Patient perceptions, including their ability to communicate, while on different sedatives, needs to be evaluated. • Pharmacology of sedatives and their delivery methods needs to be considered. • Cost considerations are important and often vary among different countries. • Sedative choice in the context of analgosedation needs further evaluation. • Choice of sedative in certain patient subgroups needs further evaluation. – Neurologically injured hemodynamically unstable patients needing deep sedation Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Objective Sedation Monitoring Descriptive Question: Are objective sedation monitoring tools (EEG-based tools or tools such as heart rate variability, actigraphy, and evoked potentials) useful in managing sedation in critically ill intubated adults? Data: 32 ICU-based studies • • • Subjective scales have limited use in deep sedation (reach their minimum values). Objective tools have limited use in increasing agitation (reach their maximum values). Objective tools (such as bispectral index [BIS]) allow measurements without stimulating the patient. Ungraded statements: 1. BIS monitoring is best suited for sedative titration during deep sedation or neuromuscular blockade. 2. Sedation monitored with BIS compared to subjective scales may improve sedative titration when a sedative scale cannot be used. Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Physical Restraints Descriptive Question: What are the prevalence rates, rationale, and outcomes (harm and benefit) associated with physical restraint use in intubated or nonintubated critically ill adults? Rationale: • No RCTs have explored safety and efficacy. • Use varies from 0 in some European countries to 75% in North America. • Historically used to: – enhance patient safety and prevent falls – prevent self-extubation or tube or device dislodgement or removal – control patient behavior and protect staff from combative patients • Paradoxically higher event rate with restraint use found in some descriptive studies Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

Physical Restraints Ungraded statements: . . . frequently used for critically ill adults, although prevalence rates vary greatly by country. . . to prevent self-extubation and medical device removal, avoid falls, and to protect staff. . . despite a lack of studies demonstrating efficacy and the safety concerns associated with physical restraints (e. g. , unplanned extubation, greater agitation). Evidence gaps: • Effect of nursing staffing pattern, family and patient advocacy, and staff education • Necessity and ethics of physical restraint during end-of-life care • Effect on patient-important outcomes Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

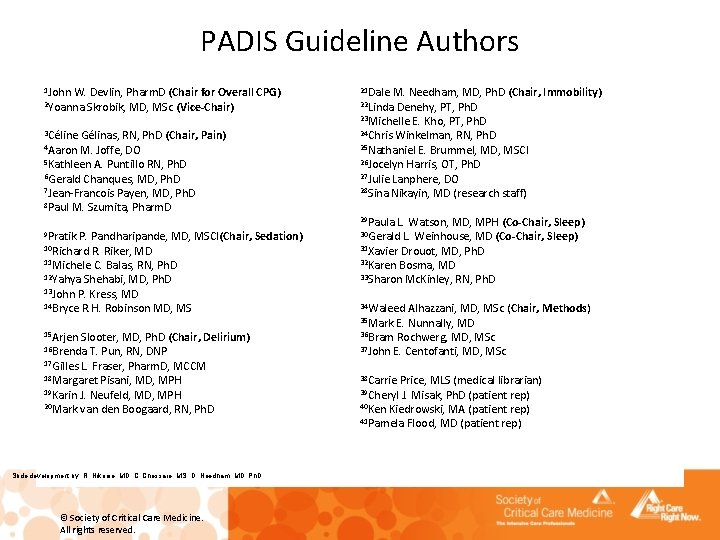

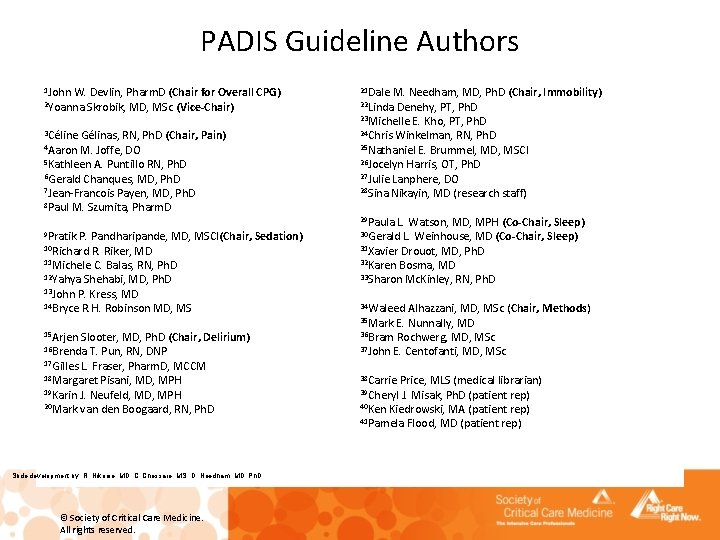

PADIS Guideline Authors 1 John W. Devlin, Pharm. D (Chair for Overall CPG) 2 Yoanna Skrobik, MD, MSc (Vice-Chair) 3 Céline Gélinas, RN, Ph. D (Chair, 4 Aaron M. Joffe, DO 21 Dale M. Needham, MD, Ph. D (Chair, 22 Linda Denehy, PT, Ph. D Immobility) 23 Michelle E. Kho, PT, Ph. D 24 Chris Winkelman, RN, Ph. D Pain) 25 Nathaniel E. Brummel, MD, MSCI 26 Jocelyn Harris, OT, Ph. D 5 Kathleen A. Puntillo RN, Ph. D 27 Julie Lanphere, DO 6 Gerald Chanques, MD, Ph. D 28 Sina Nikayin, MD (research staff) 7 Jean-Francois Payen, MD, Ph. D 8 Paul M. Szumita, Pharm. D 12 Yahya Shehabi, MD, Ph. D Sleep) 30 Gerald L. Weinhouse, MD (Co-Chair, Sleep) 31 Xavier Drouot, MD, Ph. D 32 Karen Bosma, MD 33 Sharon Mc. Kinley, RN, Ph. D 14 Bryce R. H. Robinson MD, MS 34 Waleed Alhazzani, MD, MSc (Chair, 9 Pratik P. Pandharipande, MD, MSCI(Chair, 10 Richard R. Riker, MD Sedation) 11 Michele C. Balas, RN, Ph. D 13 John P. Kress, MD 15 Arjen Slooter, MD, Ph. D (Chair, 16 Brenda T. Pun, RN, DNP Delirium) 17 Gilles L. Fraser, Pharm. D, MCCM 29 Paula L. Watson, MD, MPH (Co-Chair, 35 Mark E. Nunnally, MD 36 Bram Rochwerg, MD, MSc 37 John E. Centofanti, MD, MSc 18 Margaret Pisani, MD, MPH 38 Carrie Price, MLS (medical librarian) 20 Mark van den Boogaard, RN, Ph. D 40 Ken Kiedrowski, MA (patient rep) 19 Karin J. Neufeld, MD, MPH Slide development by: R. Nikooie, MD, C. Chessare, MS, D. Needham, MD, Ph. D © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved. 39 Cheryl J. Misak, Ph. D (patient rep) 41 Pamela Flood, MD (patient rep) Methods)

Acknowledgement Slide content has been provided by the PADIS Guideline Leadership. © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.

For more information on how to implement the 2018 PADIS guidelines, please visit the ICU Liberation Campaign website: http: //www. sccm. org/ICULiberation © Society of Critical Care Medicine. All rights reserved.