What are indicators Indicators are data or a

- Slides: 20

• What are indicators? • Indicators are data or a combination of data collected and processed for a clearly defined analytical or policy purpose. That purpose should be explicitly specified and taken into account when interpreting the value of an indicator. • Indicators generally simplify complex phenomena so that communication of information to policy-makers and other stakeholders is enabled or enhanced. • They are powerful tools that provide feedback and early warning signals about emerging issues.

A framework for Indicators of Sustainable Development • There is no doubt that there is a need for an indicator-policy cycle that includes monitoring of biodiversity, socioeconomic, and governance indicators, within an analytical decision framework applied to local and regional scales and for multiple resources • In order to succeed, some steps in the indicator-policy cycle need to be considered: – Defined broad policy goals: Clear goals need to be defined for the indicators. – Identified the sources of data: Are there enough data to evaluate de indicators? Without good data, based on monitoring, it is not possible to develop indicators • Select the indicators: Indicators need to be tested to determine their use and validity. Can they detect trend?

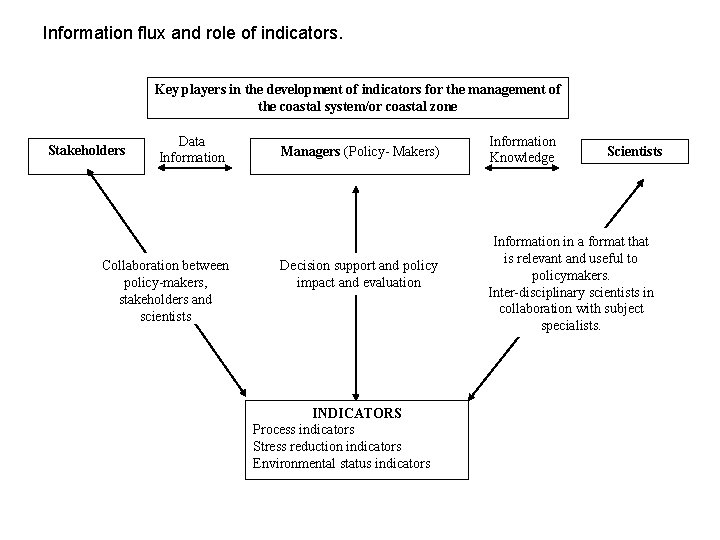

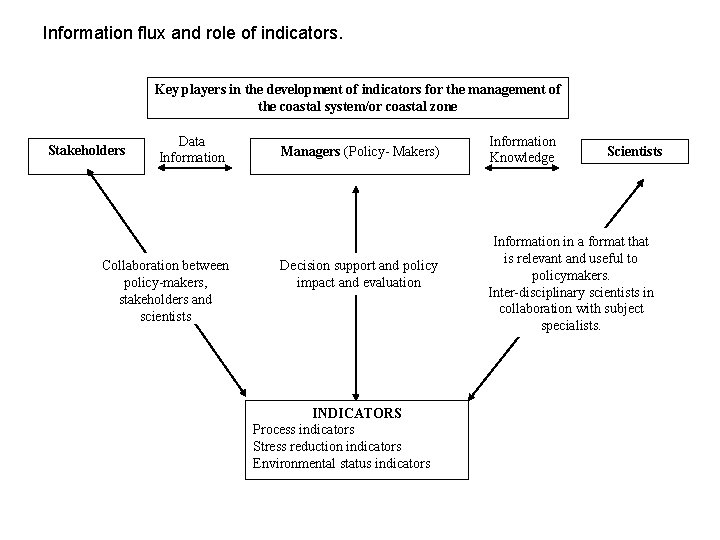

Information flux and role of indicators. Key players in the development of indicators for the management of the coastal system/or coastal zone Stakeholders Data Information Collaboration between policy makers, stakeholders and scientists Managers (Policy Makers) Decision support and policy impact and evaluation INDICATORS Process indicators Stress reduction indicators Environmental status indicators Information Knowledge Scientists Information in a format that is relevant and useful to policymakers. Inter disciplinary scientists in collaboration with subject specialists.

• The development and election of the indicators for this report was based on the types of indicators defined by Duda (2002) as: • Process Indicators: Traditionally, process indicators have been a measure of progress in project activities involving procurement and production (inputs and outputs) of goods, physical structures and services. • Stress Reduction Indicators: Stress reduction indicators relate to the specific, on the ground measures implemented by the collaborat ing countries. They provide evidence that action occurred on the ground. • Environmental Status Indicators: Environmental status indicators provide measures of actual performance or success in restor ing and protecting the targeted ecosystem or community

• Process Indicators. 1 – Existence and/or adoption of various instruments (policies, management plans, programs) and their application. • The capacity to manage fisheries depends on available human and financial resources as well as on the existence of competent institutions. 2 – Global, regional and local efforts to promote sustainable coastal and marine development. • States should co-operate on bilateral, regional and multilateral levels to establish, reinforce and implement effective means and mechanisms to ensure sustainable coastal and marine development. The management system is consistent with relevant international conventions and agreements. 3 – Global warming and climate change. • To recognize threat of climate change to coastal habitats and to ensure appropriate and ecologically responsible response

• Stress Reduction Indicators 4 – Water quality. • Healthy waterways are necessary to maintain the variety of aquatic habitats, and the economic, social and environmental systems that rely on them. Degree of turbidity and changes in turbidity levels in coastal and estuarine waters are an indicator for the conditions of the marine resources. 5 – Levels of toxic substances in the marine environment (organic and inorganic contamination). • Monitoring major groups of contaminants (e. g. , persistent organic pollutants, hydrocarbons, heavy metals) dispersed/dissolved in the water column and/or accumulated on surface sediments provides a good indication of anthropogenic pollution pressure on the marine resources. 6– Level of restoration/recuperation of ecosystems and species. • Habitat measurements help identify and quantify habitat types (number and percent coverage) and spatial patterns of key habitats (diversity at the ecosystem-level). Such measurements are helpful to review the current status of coastal habitats in terms of natural versus impacted habitats.

• Environmental Status Indicators 7 – Changes in the spatial coverage of marine ecosystems. • Changes in the area of habitat can indicate changing conditions in the environment that could be caused by natural disturbances or by anthropogenic factors, such as habitat use and fishing. Geospatial information improves our understanding of our environment, allows for more comprehensive and transparent planning, and can help increase stakeholder participation in environmental management. 8 – Landings/catches from the populations of exploited fishing resources. • Fish abundance, age and size composition, and length and weight relationships are the primary parameters scientists require to describe the status of a fish population. In addition to static parameters (i. e. , those at a single point in time), dynamic parameters that quantify rates of population processes, such as survival, growth, reproduction and mortality, provide greater insight into a fish population’s ecological state. 9 – Levels of fishing effort. • Effective fishing effort” is a measure of fishing mortality. Landings (in terms of volume or value) and fishing efforts (e. g. , number of vessels, types and number of nets, gear, etc. ) may be a useful proxy to assess the quantity of resources harvested and it may be an indication, although indirect, of the status of local fisheries and fish stocks.

• The development of indicators and their use in evaluating progress is dependent on a data and information management and reporting system being put in place by government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil society, and the private sector. Within the CLME region there a several national, regional and international programs targeting the collection of environmental indicators. These include: CARICOM’s Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity Programme, Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), UNEP under different programs (such as Caribbean Environmental Program and Environmental Data Explorer GEO), United Nations (UNSD Environmental Indicators), World Resource Institute (Ecosystem Service Indicators database), Worldwide Governance Indicators, Latin American and Caribbean Initiative for Sustainable Development (ILAC), The World Bank, and The Nature Conservancy, among others.

Recommendations on Indicator Information • The process of establishing a set of indicators for the CLME in coastal and marine zones is not easy. • Significant scientific, technical and administrative effort, as well as, consensus with stakeholder groups must be achievement before the definition of indicators and targets are established. • It also implies agreement between governments (local and regional) on the intensity of monitoring, the goals and the resources required. • It is recommended to develop indicator factsheets based on the existing data. This fact sheets should be regional or country specific depending of the data available. • Communication is the key for success of an indicator policy. • A common framework is needed in the CLME region.

• Indicators must be established under baseline conditions. Indicators are most effectively assessed when baseline information on the governance, ecological and socioeconomic conditions of the management area is available. • Indicators should relate to the specific management issues, such as multiple user conflicts, ecological degradation, community interest, or a commitment to improve the management of a local marine area. • It is strongly recommended that stakeholders are consulted as early as possible in the indicator development process in order to determine the purpose of the indicator and its audience. • Transparency in the decision making process promotes credibility and provides opportunities for stakeholders to introduce new information.

• The indicators selected for use should be based on the best scientific understanding currently available and have been developed in consultation with international and country experts, other agencies and stakeholder groups. • The more an indicator meets a real decision-making need and it is effectively communicated, the greater the likelihood that a national or regional statistic agency will recognized the value of the indicator. • The calculation of an indicator must be accompanied by documentation of the methods used and data sources. This ensures that the calculation is transparent and open to scrutiny and can be repeated in the future for consistent production of the indicator. • The agreement on the indicator set and the standardization of methodology and formats for compilation and presentation of results ensures the comparability, correct assessment and aggregation of the results obtained in different countries and at different scales around the CLME. Furthermore, the identification of data gaps or limitations will allow prioritization of effort on the monitoring of required datasets.

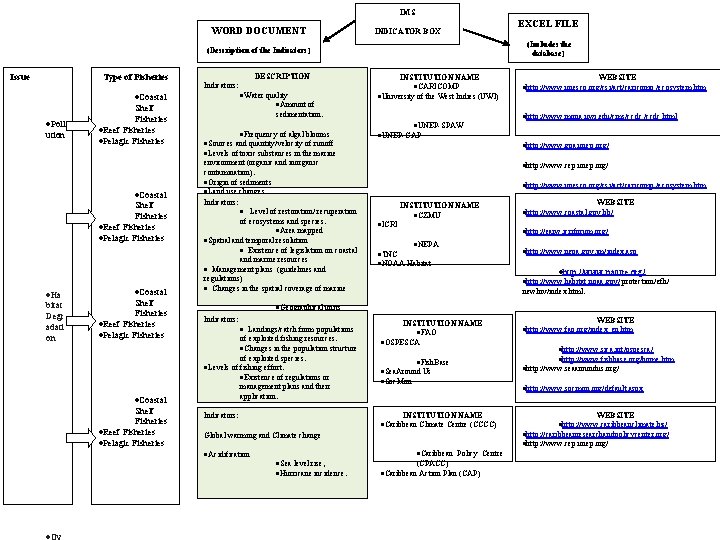

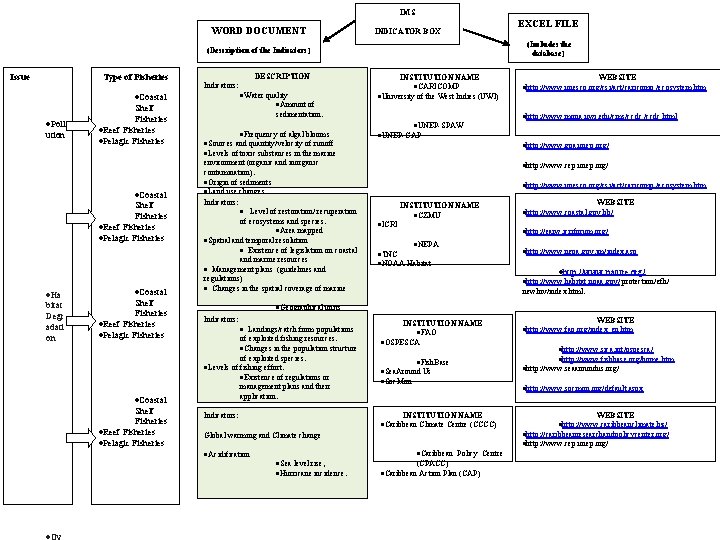

IMS WORD DOCUMENT INDICATOR BOX (Includes the database) (Description of the Indicators) Issue Type of Fisheries DESCRIPTION Indicators: ·Coastal ·Poll ution Shelf Fisheries ·Reef Fisheries ·Pelagic Fisheries ·Coastal Shelf Fisheries ·Reef Fisheries ·Pelagic Fisheries ·Ha bitat Degr adati on ·Coastal Shelf Fisheries ·Reef Fisheries ·Pelagic Fisheries ·Water quality ·Amount of environment (organic and inorganic contamination). ·Origin of sediments ·Land use changes. Indicators: · Level of restoration/ recuperation of ecosystems and species. ·Area mapped ·Spatial and temporal resolution · Existence of legislation on coastal and marine resources · Management plans (guidelines and regulations) · Changes in the spatial coverage of marine ·Geographical units ·Indicators: Zoning plan ·Mapping Essential Fish Habitat · Landings/catch from populations Demographic information of exploited fishing resources. ·Changes in the population structure of exploited species. ·Levels of fishing effort. ·Existence of regulations or management plans and their application. ·UNEP SPAW ·http: //www. mona. uwi. edu/cms/ccdc. html ·http: //www. gpa. unep. org/ ·http: //www. cep. unep. org/ ·http: //www. unesco. org/csi/act/caricomp /ecosystem. htm ·ICRI INSTITUTION NAME ·CZMU WEBSITE ·http: //www. coastal. gov. bb/ ·http: //earw. icriforum. org/ ·NEPA ·TNC ·NOAA Habitat ·http: //www. nepa. gov. jm/index. asp ·http: //www. nature. org/ ·http: //www. habitat. noaa. gov/ protection/efh/ new. Inv/index. html. WEBSITE INSTITUTION NAME ·FAO ·OSPESCA ·http: //www. fao. org/index_en. htm ·Fish. Base ·Sea. Around Us ·Soc. Mon ·http: //www. seaaroundus. org/ ·Caribbean Climate Centre (CCCC) Global warming and Climate change ·Sea level rise, ·Hurricane incidence. WEBSITE ·http: //www. unesco. org/csi/act/caricomp /ecosystem. htm ·UNEP GAP INSTITUTION NAME Indicators: ·Acidification ·Ov INSTITUTION NAME ·CARICOMP ·University of the West Indies (UWI) sedimentation. ·Frequency of algal blooms ·Sources and quantity/velocity of runoff ·Levels of toxic substances in the marine EXCEL FILE ·Caribbean Policy Centre (CPACC) ·Caribbean Action Plan (CAP) ·http: //www. sica. int/ospesca/ ·http: //www. fishbase. org/home. htm ·http: //www. socmon. org/default. aspx WEBSITE ·http: //www. caribbeanclimate. bz/ ·http: //caribbeanresearchandpolicycenter. org/ ·http: //www. cep. unep. org/

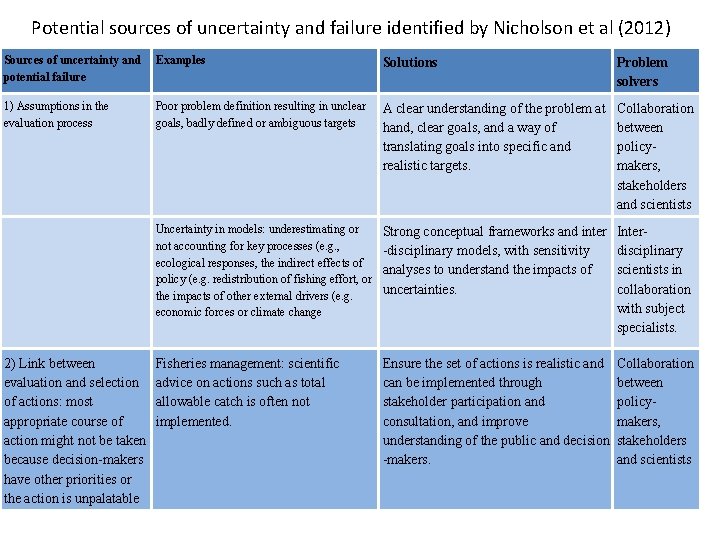

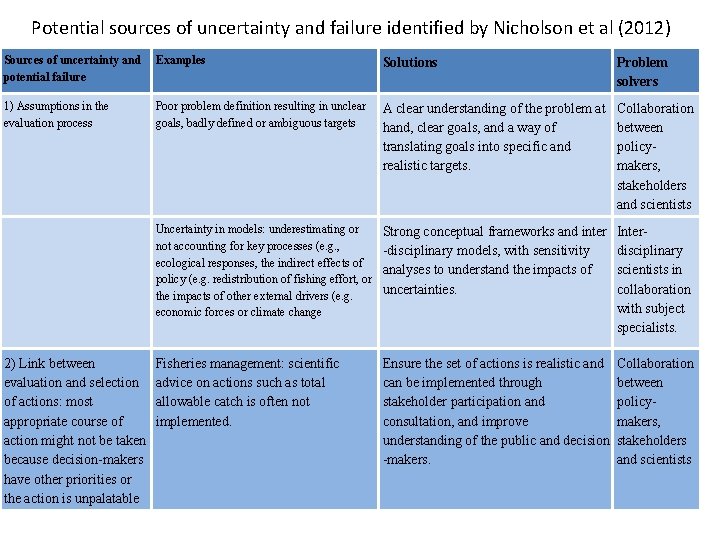

Potential sources of uncertainty and failure identified by Nicholson et al (2012) Sources of uncertainty and potential failure Examples Solutions Problem solvers 1) Assumptions in the evaluation process Poor problem definition resulting in unclear goals, badly defined or ambiguous targets A clear understanding of the problem at hand, clear goals, and a way of translating goals into specific and realistic targets. Collaboration between policy makers, stakeholders and scientists Uncertainty in models: underestimating or not accounting for key processes (e. g. , ecological responses, the indirect effects of policy (e. g. redistribution of fishing effort, or the impacts of other external drivers (e. g. economic forces or climate change Strong conceptual frameworks and inter disciplinary models, with sensitivity analyses to understand the impacts of uncertainties. Inter disciplinary scientists in collaboration with subject specialists. Fisheries management: scientific advice on actions such as total allowable catch is often not implemented. Ensure the set of actions is realistic and can be implemented through stakeholder participation and consultation, and improve understanding of the public and decision makers. Collaboration between policy makers, stakeholders and scientists 2) Link between evaluation and selection of actions: most appropriate course of action might not be taken because decision makers have other priorities or the action is unpalatable

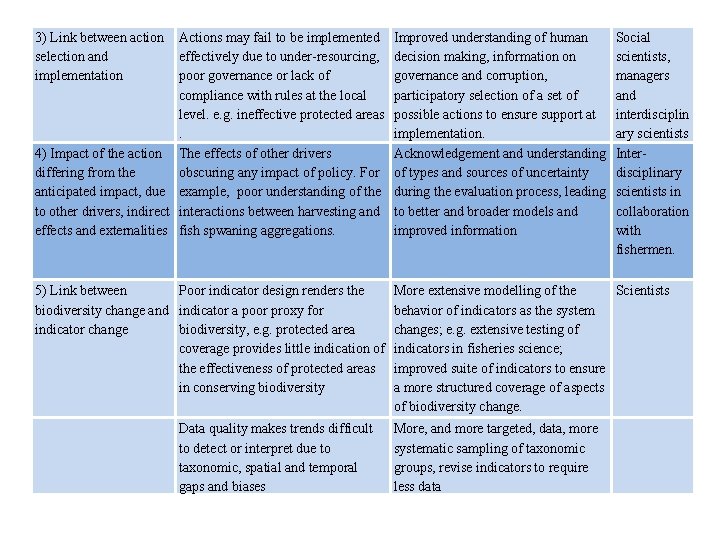

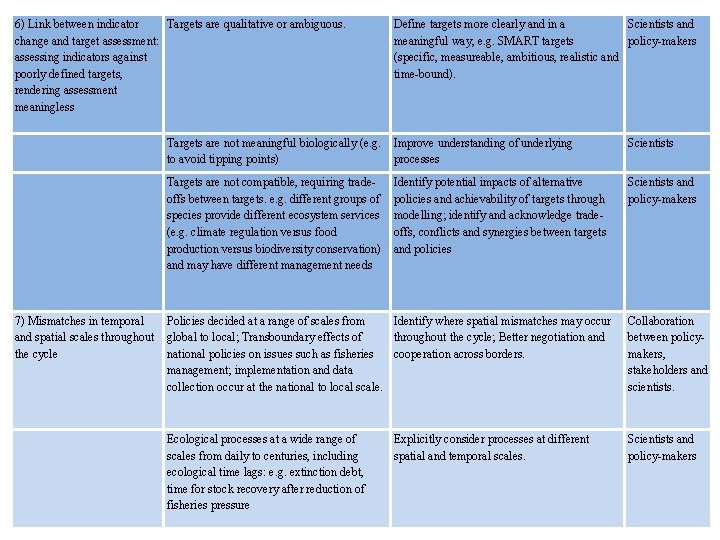

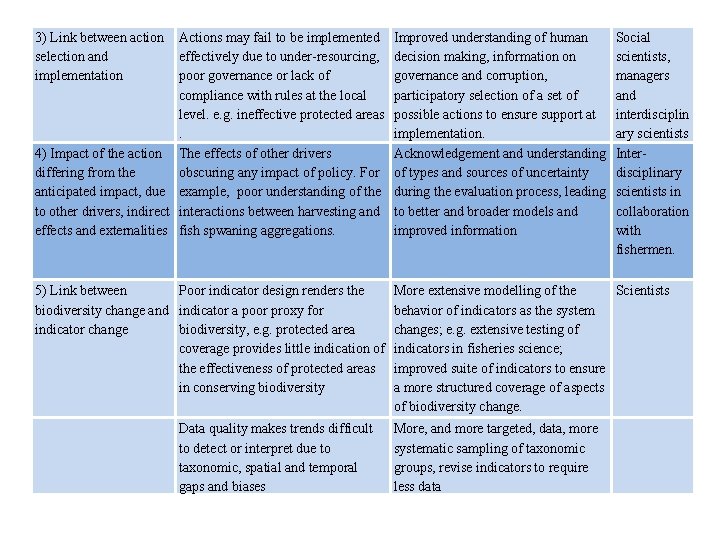

3) Link between action selection and implementation Actions may fail to be implemented effectively due to under resourcing, poor governance or lack of compliance with rules at the local level. e. g. ineffective protected areas. 4) Impact of the action The effects of other drivers differing from the obscuring any impact of policy. For anticipated impact, due example, poor understanding of the to other drivers, indirect interactions between harvesting and effects and externalities fish spwaning aggregations. Improved understanding of human decision making, information on governance and corruption, participatory selection of a set of possible actions to ensure support at implementation. Acknowledgement and understanding of types and sources of uncertainty during the evaluation process, leading to better and broader models and improved information 5) Link between Poor indicator design renders the biodiversity change and indicator a poor proxy for indicator change biodiversity, e. g. protected area coverage provides little indication of the effectiveness of protected areas in conserving biodiversity More extensive modelling of the Scientists behavior of indicators as the system changes; e. g. extensive testing of indicators in fisheries science; improved suite of indicators to ensure a more structured coverage of aspects of biodiversity change. Data quality makes trends difficult to detect or interpret due to taxonomic, spatial and temporal gaps and biases More, and more targeted, data, more systematic sampling of taxonomic groups, revise indicators to require less data Social scientists, managers and interdisciplin ary scientists Inter disciplinary scientists in collaboration with fishermen.

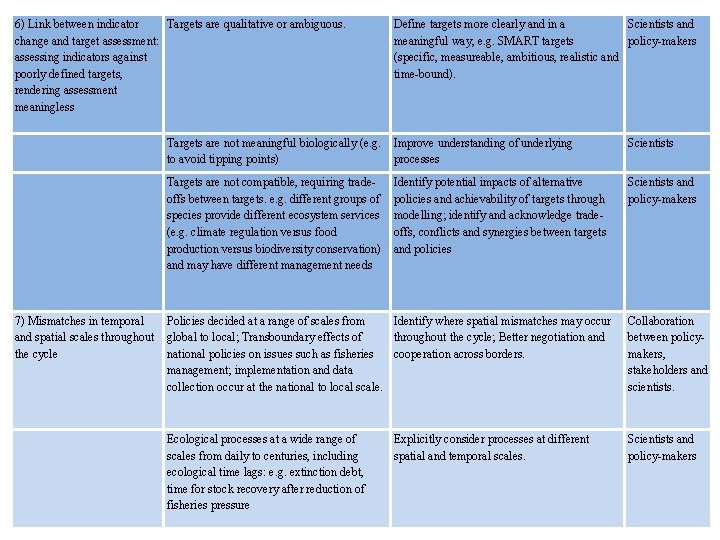

6) Link between indicator Targets are qualitative or ambiguous. change and target assessment: assessing indicators against poorly defined targets, rendering assessment meaningless 7) Mismatches in temporal and spatial scales throughout the cycle Define targets more clearly and in a Scientists and meaningful way, e. g. SMART targets policy makers (specific, measureable, ambitious, realistic and time bound). Targets are not meaningful biologically (e. g. to avoid tipping points) Improve understanding of underlying processes Scientists Targets are not compatible, requiring trade offs between targets. e. g. different groups of species provide different ecosystem services (e. g. climate regulation versus food production versus biodiversity conservation) and may have different management needs Identify potential impacts of alternative policies and achievability of targets through modelling; identify and acknowledge trade offs, conflicts and synergies between targets and policies Scientists and policy makers Policies decided at a range of scales from Identify where spatial mismatches may occur global to local; Transboundary effects of throughout the cycle; Better negotiation and national policies on issues such as fisheries cooperation across borders. management; implementation and data collection occur at the national to local scale. Collaboration between policy makers, stakeholders and scientists. Ecological processes at a wide range of scales from daily to centuries, including ecological time lags: e. g. extinction debt, time for stock recovery after reduction of fisheries pressure Scientists and policy makers Explicitly consider processes at different spatial and temporal scales.

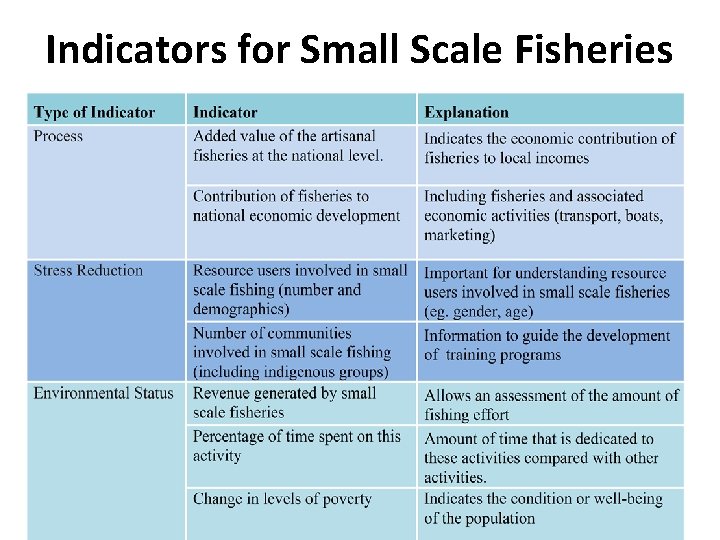

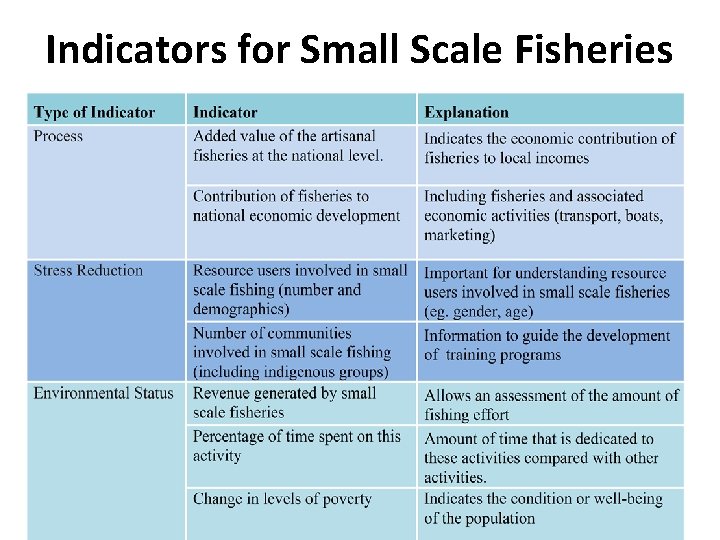

Indicators for Small Scale Fisheries

• An indicator approach provides a useful tool for appraising sustainability and for assessing policies – in particular for assessing measures and actions taken or proposed in relation to marine resources. • Indicators can help to inform citizens, policymakers, scientists and other stakeholders about the status of marine resources, human impacts on the marine ecosystem, mitigating actions and the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders.

A framework for Indicators of Sustainable Development • Specify targets that are measurable using indicators. • Define actions that can be implemented or achieve; use models to make predictions about the potential impacts. • Indicators must therefore be able to take into account different locations, people, cultures and institutions • All this information can be used to improve monitoring and collection of better indicator datasets.

Database questions • The development of an effective indicator framework requires data and information, as well as appropriate data, information management and mechanisms to calculate, review and revise the indicators on a continuous basis. However, there are fundamental gaps in data collection and monitoring for sustainable development in coastal areas of the CLME. As mentioned by Heileman and Walling (2008), a number of initiatives have been undertaken in the region to improve environmental statistics. Some of the main problems are summarized below: • The coastal zone is not well represented as a distinct reporting unit or as a specific area in most GIS information sources or databases. • There is a lack of coherence in data gathering programs in terms of geographic and temporal coverage, and in the definition of measurements. This can be due to the absence of guiding policies, deficient benchmark information or inadequate analysis. • Indicators calculated by research centers, government, public administrations or agencies may be limited in scope (methodology, definitions, coverage), which restricts their usefulness at a wider regional level. • Differences in statistical data between countries may result in a bias in calculations and in comparison of 'the coastal zone' between CLME countries, in particular for population and socio-economic data.

• • • Differences in the composition of sampling units for different reporting purposes may cause inconsistencies at the moment of reporting indicators between countries and over time. Frequency and interval of sampling may not coincide between countries. For instance, frequency and period of sampling for two related indicators or indicators (e. g. number of overnight fishing trips and numbers of fishing boats) may not coincide, generating an unknown bias in the results. Changes in methodology over time, within the data gathering program, may create an interruption and/or a breach in time series. This can be due to changes in measuring instruments, modifications in the location of measuring stations, changes in weighting factors in the analysis of data from surveys, etc. Geo-referenced data is limited. Data needs to be geo-referenced in order to allow comparisons and representation of socio-economic and environmental information. Consistent data and data flow should provide a more realistic picture of the processes taking place and support decision-making at different levels (from local to national to CLME level). The best way to ensure comparability data or indicators at all levels is a bottom-up approach in data collecting and information systems: starting from reliable and sound data at the local level and aggregating it at higher levels in common databases.