Transpersonal Experiences Modified States of Consciousness and the

- Slides: 37

Transpersonal Experiences, Modified States of Consciousness, and the Use of Psychoactive Substances Elías Capriles (Venezuela)

1. Transpersonal experiences: distinguishing three main types • A key shortcoming of transpersonal and “integral” psychologies is that they fail to distinguish • • between transpersonal and holotropic-and/or-holistic states of radically different signs:

1 a. Transpersonal, perfectly holistic states of nonstatic nirvāṇa: Buddhahood, rigpa (rig pa): • • • In them the true condition of ourselves and whole universe is perfectly, directly unconcealed for there is none of the types of unawareness and delusion that the Dzogchen teachings distinguish in that which the Buddha called avidyā: there is neither a beclouding of the true condition by an element of stupefaction (Tib. mongcha: rmongs cha) or a distortion of it by the subject-object duality or other types of perception in terms of concepts. Moreover, in them spontaneous selfless, nonconceptual activities achieve the purposes of self and others. Example in terms of the life of Buddha Śākyamuni: his condition after Awakening.

1 b. Transpersonal, quasi-holistic state in which saṃsāra is not yet actively functioning: • • • • This is the neutral condition of the base-of-all (Tib. kunzhi lungmaten [kun gzhi lung ma bstan]), which is free from the subject-object duality and from perception in terms of concepts, yet involves an innate unawareness of the true condition (Tib. gyu dagnyi chikpai marigpa [rgyu bdag nyid gcig pa’i ma rig pa]) due to a beclouding by the already mentioned element of stupefaction (mongcha). As Dzogchen Master Jigme Lingpa prophesized, the danger involved is that in our time it will be mistaken for the dharmakāya which is the “Mind” aspect of Buddhahood—i. e. , of nonstatic nirvāṇa. In terms of the life of Buddha Śākyamuni, this corresponds to the absorption in which he rested right before Awakening.

1 c. Transpersonal and holotropic states pertaining to active saṃsāra: the formless absorptions and realms: • In them the figure-ground distinction disappears • • yet there is a seemingly separate mental subject that identifies with the ensuing infinitude • • and derives subtle pride and a sense of power from this. • • In terms of the life of Buddha Śākyamuni, this corresponds to the achievements of the two successive teachers he followed after renouncing his princely life.

2. Modified states of consciousness: challenging the prevailing view 2 a. Saṃskṛta and asaṃskṛta • • • • The term saṃskṛta, which subsumes the notions of produced, contrived, conditioned, composite, constructed and modified, refers to all that is born from causes and conditions or from interdependent arisings and that is therefore impermanent, subject to suffering, and pertaining to cyclic existence—saṃsāra. This term is contrasted with asaṃskṛta, which subsumes the notions of unproduced, uncontrived, unintentional, unconditioned, uncomposite, unconstructed and unmodified and within which the higher forms of Buddhism include only:

i • • • (i) conditions of nonstatic nirvāṇa such as Buddhahood and rigpa, and (ii) the true condition that is unconcealed in nonstatic nirvāṇa. The nature of all that is asaṃskṛta is reflected in the etymology of the Tibetan word naljor (rnal ’byor): Nalma (rnal ma) means “unmodified condition of something, ” whereas jyorwa (’byor ba) means to possess—yet in this term has the acceptation of directly realizing beyond concepts .

2 b. The saṃskṛta and the ubiquitous unawareness and delusion called avidyā • • • • The saṃskṛta is all that is affected by the ubiquitous unawareness and delusion called avidyā and that therefore pertains to saṃsāra: We begin with an innate unawareness of the asaṃskṛta, unmodified condition produced by the already mentioned element of stupefaction (mongcha), and then active saṃsāra is produced when the contents of thought, which are digital and thus discontinuous, are endowed with an illusion of truth, absoluteness and value—which is what here I will abridge as potentiation of the contents of thought— and hence the sensory territory, which is analog and as such continuous, is distorted upon being perceived in terms of digital and as such discontinuous, potentiated concepts as being in itself discontinuous and as involving substantial duality and plurality. According to the Dzogchen teachings the above is produced by three or four types or aspects of avidyā:

i • • • (i) The innate unawareness of the asaṃskṛta, unmodified condition produced by the already mentioned element of stupefaction which pervades the whole of our experience, and which is also manifest in the passively samsaric condition of the base-of-all in which absorption for a significant length of time can only be achieved if it is produced by meditative self-conditioning. (ii) The discontinuity introduced by the subject-object duality that ontogenetically we develop when we are infants due to the potentiation of the supersubtle thought called the threefold directional thought-structure (Skt. trimaṇḍala / Tib. khorsum [’khor gsum]) which conceives a subject, an experience or an action or a thinking, etc. , and an object.

i • (iii) The discontinuity produced by the potentiation of subtle / intuitive potentiated thought (Skt. arthasāmānya; Tib. dönchi [don spyi]) • • which as a result of the process of conditioning in the family, the school and the whole of society • • makes us experience everything in terms of one or another potentiated thought • • and thus be under the illusion that each figure that we single out is inherently separate • • and that it is the concept that we apply to it—which yields the illusion of a multiplicity of substantial entities— • • and that, when also coarse / discursive thoughts (Skt. śabdasāmānya; Tib. drachi [sgra spyi]) are potentiated, • • produces another discontinuity as discursive thoughts are felt to be inherently true or false. • • (iv) Finally, saṃsāra is perfected as the suffering inherent in active saṃsāra • • is eluded by means of double phenomenological negations: • • in same operation something is negated, and it is negated that something is negated, • • —as in the case of the self-deceit Sartre called Bad Faith and Laing named elusion— • • and hence less distressful states are produced that, • • the more pleasant and gratifying, the more unauthentic and deceitful they are.

2 c. The energetic-volume-determining-the-scope-ofawareness (Tib. thig le, somewhat akin to Skt. kuṇḍalinī) • • • • According to Tantric bioenergetics, in the process of conditioning, repression and punishments reduce the entrance of energy to the higher energy centers, associated to the brain, putting an end to the oceanic feeling with its panoramic awareness and producing a figure-ground mind a tunnel-like consciousness, that, in combination with the potentiation of thought, produces the acute unawareness of interconnections that is at the root of ecological crisis, social contradictions etc.

2 d. Ascenders Vs. Descenders in Phenomenological and Existential Terms: Ascent as the construction of saṃskṛta / modified states • • • • In the 1990 s the so-called Ascender / Descender Debate pit Ken Wilber against Stan Grof and Michael Washburn, yet neither of the parts understood ascent as the production of saṃskṛta, modified states or Descent as Seeing through saṃskṛta, modified states into the asaṃskṛta, unmodified true condition. Spiritual ascent may be achieved by means of the “healthy, ” “positive” conditioning yielded by pacification and other kinds of conditioning meditation which boosts the already discussed elusion or bad faith so that more desirable saṃskṛta states may be achieved. For example, the achievement of a god of sensuality, which may involve worldly pleasure, success or power, may be achieved through a worldly training, yet it will always depend on accumulated good karma and hence will always be impermanent.

i • • • • • Likewise, the achievement of a god of form may be attained by means of steady concentration on a figure and thus accumulating karma of immobility (Skt. āninjyakarma; Tib. migyowe lai [mi gyo ba’s las]); therefore, it will also be impermanent. Finally, the achievement of a god of formlessness, which may be attained by means of a steady absorption beyond the figure-ground division in which there is a subject-object duality, yet the subject identifies with the infinitude subtly appearing as object and by means of this self-deceit achieves an illusion of cosmic union or cosmic identity and thereby obtains very subtle pride and pleasure, which is the summit of saṃsāra and the extreme of self-deceit and inauthenticity, also depends on karma of immobility and therefore it is also impermanent.

i • Since all that is saṃskṛta is impermanent and a source of suffering • • none of these “godly” states offers a solution to the “problem of life” • • for even though they may allow one to elude suffering for long whiles, • • when the karma to remain in them is exhausted, one bitterly suffers on foreseeing one’s fall, • • and when one falls, since one has become used to the pleasant and unfamiliar with the unpleasant, • • one will strongly reject the more painful experiences of lower states, and hence positive feedback loops will exacerbate the ensuing suffering.

2 e. Descent as Seeing through the saṃskṛta / modified into the asaṃskṛta / unmodified • In my presentation at the Colloquium, I showed normality to be a deluded insanity that yielded the ecological crisis that, • • unless that insanity and the structure and function of human society are healed, would occasion our self-destruction. • • The point I want to make today is that the Path to achieve the definitive healing of that insanity is descendent, • • for it can only be irreversible if it lies in a spontaneous and thus asaṃskṛta Seeing through all that is saṃskṛta • • into the asaṃskṛta true condition, which alone is perfectly and ultimately authentic • • —and, in the long run, in coming to live in it, so that all suffering comes to an end absolute plenitude and perfection are attained, • • yielding all-accomplishing selfless activities that spontaneously achieve the benefit of both self and others (Tib. tinle [phrin las] / khorsum nampar mitokpai lai dang drebu [’khor gsum rnam par mi rtog pa’i las dang ’bras bu]).

i • • • • In the Atthasālinī, Theravāda teacher Buddhaghoṣa illustrated the inauthentic ascending path that lies in establishing “healthy attitudes and meditative practices confined to the spheres of sensuality, that of form and that of formlessness” that “build up and make grow birth and death in a never-ending circle” and therefore are called “building-up practices” with a man that sets out to erect a wall eighteen cubits high. On the other hand, the descending Path, which involves a meditation that he calls “the tearing down one” (apacayagāmi) he illustrated with a man who “takes a hammer and breaks down and demolishes any part as it gets erected” even though it is not an active endeavor, for what it actually does is to bring about a deficiency in those conditions that tend to produce birth and death.

i • Sanā’ī & Rūmī: Greek and Chinese painters • • Dialogue between Mǎzǔ Dàoyī (馬祖道; Wade-Giles, Ma 3 tsu 3 Tao 4 -yi 1) and Nányuè Huáiràng (南嶽懷讓; Wade-Giles, Nan 2 -yu eh 4 Huai 2 -jang 4), who was to become his teacher.

2 f. Existential ascent and metaexistential descent as illustrated by Dante’s Divine Comedy • • • • Existentialism and Existenz Philosophie equate authenticity with facing the naked experience of what I am calling the modified, saṃskṛta condition —which may be identified with facing hell, for as Sartre noted, anguish (and nausea and so on) is the naked experience of the being of consciousness which he called Being-for-Self, whereas shame is the naked experience of becoming what others perceive as us, which he called Being-for-Others. What I call metaexistential descent lies in descending into hell and down though it to its bottom, and then undergo the initial asaṃskṛta dissolution of all that is modified / saṃskṛta and the concomitant disclosure of the asaṃskṛta, unmodified true condition thus—like Dante, Dzogchen practitioners or Paleo-Siberian shamans—“going through the hole at the bottom. ”

i • • • • This shows hell not to be an eternal descent into ever-greater suffering but a way to purge the modified, saṃskṛta condition and the karmas that sustain it until the asaṃskṛta / unmodified true condition is no longer hidden or distorted —which is the reason why going through the hole represents the transition to purgatory, through which the individual can then ascend to heaven. In this process all that is modified / saṃskṛta liberates itself repeatedly until its naked experience is no longer painful which is where one “enters” heaven and begins to ascend through it until the modified / saṃskṛta has been totally neutralized and hence one has become established in the unmodified, asaṃskṛta empyrean —or, in the symbolism of Buddhist Dzogchen, in the Akaniṣṭha-Ghanavyūha pure land.

2 g. Contrarily to the metaphenomenological descent leading to total authenticity and definitive sanity, Ken Wilber posits a phenomenological ascent • • • • In fact, Ken Wilber’s path is phenomenologically ascending, for it involves the arising of successive: (i) basic structures, resulting from a multidimensional learning and a conjunction of a main cause & secondary circumstances, and therefore being produced / arisen / modified / saṃskṛta and as such impermanent, spurious and pertaining to saṃsāra and being maintained when development continues to a higher level, for they integrate themselves into all subsequent basic structures, each founded on the former and arising only after the former is firmly established —like stores of a Babel tower intended to attain the unmodified, asaṃskṛta empyrean but at best offering a possibility of attaining the modified, saṃskṛta formless realms—

i • and (ii) transitional or replacement structures, which are • • “ways in which the world is experienced through the basic structures of a psychic level” • • and which, unlike the former, are not preserved on proceeding to higher psychic levels • • but which, since they depend on the former, are also produced / modified / conditioned and thus saṃskṛta. • (iii) Besides, Wilber posits a Self that identifies with successive basic structures, thus giving rise to • • (iv) what he calls fulcra.

i • • • • Since identification cannot occur without a subject-object duality and the conjunction of the Self that identifies with that with which it identifies, fulcra are produced and conditioned and as such pertain to saṃsāra. Moreover, identification produces a sense-of-self, but in Buddhism all senses-ofself are by nature spurious and delusive. Thus in Buddhist terms Wilber’s path sustains and perfects the saṃskṛta / modified And therefore is inauthentic and contrary to authentic Paths of Awakening. Though Wilber juggles with all that was just denounced in order to conceal it, in my four-volume book The Beyond Mind Papers I carefully analyzed his writings until the first decade of the twentieth first century and showed it to be so beyond all doubts.

2 h. Descent in Grof and Washburn • Rather than viewing descent as Seeing through the self-deceit, structures, concepts and stupefaction • • that conceal the asaṃskṛta, unmodified, original true condition • • these two transpersonal icons harbor a regressive view of the descents they favor, • • seemingly failing to realize that the truly liberating descent in the one achieved by facing hell and uncontrivedly Seeing through it, • • as happens in the already discussed metaexistential and metaphenomenological descent.

2 h(i). Grof: • He posits Basic Perinatal Matrixes (BPMs) • • which are stages of the perinatal process, each with different varieties, • • and his therapy lies in reliving determining MPBs • • as though this were in itself therapeutic—not only superficially so, but ultimately so. • • Moreover, his view contradicts the structure and function of the metaphenomenological, metaexistential healing processes • • because he categorizes some MPBs as “good” and some as “bad” • • —as though conflictive experiences were in themselves noxious, • • rather than being supreme opportunities to See through the saṃskṛta into the asaṃskṛta, • • to burn karma, and to develop a high capacity of self-liberation, • • and as though the types of MPBs 1 and 4 he deems good were ultimately therapeutic realizations. • • Finally, he conceives ultimate sanity, which he seemingly confuses with Awakening, • • as a relative, conditioned state in which one is less deceived than normal people.

2 h(ii). Washburn: • • • • • He posits the triadic structure of the psyche of second Freudian topic as being inherent in the human condition and hence as being maintained in the ultimate spiritual realization that he calls “mystical illumination. ” He conceives the path as a reintegration of what he calls the Dynamic Ground, which he associates with the Freudian Id and which at an early age a Freud-like primal repression expelled from the Ego, giving rise to a primal split. He locates the Dynamic Ground and the Id in the pelvic-anal region and the Ego-Superego compound in the head, as though the topoi of the second Freudian topic were areas of the body. He promotes meditation as a key element in the process of descent, yet as shown in my book The Beyond Mind Papers he classifies the types of meditation and their effects in an imprecise way.

2 i. Psychotic Descent • • • • • As shown in my presentation at the Colloquium, the saṃskṛta / modified state of consciousness we call normality is a form of insanity involving relatively conflict-free adaptation to an absolutely insane society and resulting from interaction between innate propensities and conditioning hypnosis by means of what Laing called attributions with force of injunctions in what I call normalizing family, which is the one that applies what I call normalizing double-binds. Madness may result from innate propensities and conditioning / hypnosis in a dysadaptive family which regularly applies Bateson’s pathogenic double-binds and involves other circumstances that yield conflictive states that mainstream psychiatry / clinical psychology deem psychotic. Among these, some forms of what is diagnosed as “schizophrenia” are the potentially healing processes R. D. Laing called “true madness, ” which de-realize what we wrongly perceive as real so that a re-realization of some of the true condition that normally we ignore and/or view as unreal may possibly occur.

i • • • • However, the family and, as a rule, mental institutions, disrupt these processes turning them into the long-term, possibly lifelong “illnesses” that Laing called “a gross travesty, a mockery, a grotesque caricature of what the natural healing of that estranged integration we call sanity may be. ” John Weir Perry’s experience in his center, Diabasis, showed that an initial episode of this kind, if allowed to follow its natural course in a supportive, wise environment, lasts for no more than six (or a maximum of seven) weeks, and results in a reduction of conflict and insanity, and an increase in harmony and authenticity. However, David Cooper’s antipsychiatry overvalued the healing power of madness, giving to understand it could result in nonstatic nirvāṇa (= Awakening).

2 j. Only Paths of Awakening revealed by fully Awake individuals can result in a thorough disclosure of the unmodified, true condition of awareness that discloses the unmodified true condition of ourselves and the whole universe • • • No psychological therapy except for the authentic traditions of Awakening can lead to the absolute sanity that lies in the stabilization of nonstatic nirvāṇa. (i) Such traditions are metatranspersonal because they don’t mistake samsaric transpersonal and holotropic states for nonstatic nirvāṇa yet may use samsaric transpersonal and holotropic states as springboards to rigpa —i. e. , nonstatic nirvāṇa. (ii) They are metaphenomenological because their method lies in Seeing through the saṃskṛta / modified into the asaṃskṛta / unmodified (iii) And they are metaexistential because their method lies in facing hell and going through it, as the fast track for rapidly neutralizing avidyā.

i • (iv) Like in true madness, progress in such Paths is catalyzed by the Freudian Thánatos, • • and it involves successively going through states analogous to MPBs 2 & 3, • • and then repeatedly going through a transition comparable to that between an MPB 3 and an MPB 4 • • —in which, however, the coming point, rather than a samsaric MPB 4, is an episode of (c) nonstatic nirvāṇa. • • Every time this transition takes place, it neutralizes propensities for unawareness and delusion • • And hence the repetition of this in the long run totally neutralizes those propensities.

i • • • • (v) Like true madness, they begin with a derealization of the false / saṃskṛta / modified involving illusory experiences of emptiness / insubstantiality that would be viewed as psychotic by mainstream systems. However, those treading the Path might not experience them as undesirable pathologies: if their capacity is high, their occurrence may even yield great happiness. (vi) Unlike true madness, they necessarily involve the disclosure of the asaṃskṛta / unmodified condition which is thus re-realized, until in the long run it is irreversibly stabilized. The above is illustrated by a Chán / Zen saying: When I began to practice Zen for me mountains were simply mountains and rivers were simply rivers. When my practice of Zen developed, mountains were for me no longer mountains and rivers were for me no longer rivers. When I attained the Truth of Zen, to me mountains came to be true mountains and rivers came to be true rivers.

2 j. In Dzogchen and Tantra, the energetic-volume-determining-thescope-of-awareness is increased to produce modified states characterized by a wider scope of awareness and an intensified experience • quite similar to those produced by psychedelics, holotropic breathing, etc. • • However, Dzogchen and Tantra use them in a way that is in stark contrast with the latter, • • for practitioners are aware that they are all illusory experiences in which they should not to dwell and which they should not confuse with Awakening, • • yet they should use as an experiential basis for questioning experience and thus realize the asaṃskṛta / unmodified true condition. •

i • In fact, the Dzogchen teachings illustrate the nature of mind with a Mirror • • and extraordinary experiences with reflections, initially to be used for discovering the Mirror’s true condition • • and subsequently to be used for keeping to the true Condition of the Mirror • • by helping the illusion of a mental subject —called “the one reflected”— to self-liberate whenever it arises, • • until the propensities for it to arise are totally neutralized.

3. The use of psychoactive substances: Approaches to holotropic states of consciousness other than those of Dzogchen and Tantra • • • All the approaches discussed next share shortcomings such as the inability to distinguish radically between different transpersonal and holotropic or holistic states or to use those which are not nonstatic nirvāṇa as a springboard for achieving nonstatic nirvāṇa.

3 a. Approach of recreational users of psychedelics: • • • • Three main types of transpersonal, holotropic states and other samsaric conditions succeed each other: (i) First there is the base-of-all (Skt. ālaya; Tib. kunzhi [kun gzhi]) where there is neither a subjectobject duality nor any other kind of thought (ii) Then the potentiation of the threefold directional thought structure produces the subject-object duality and the potentiation of the subtle concept interpreting the limitless object produces a conceptualization of infinity thus producing a formless (Skt. ārūpa; Tib. zukmé [gzugs med]) condition: example of “all is one, ” etc. (iii) Then the consciousness of the base-of-all (Skt. ālayavijñāna; Tib. kunzhi namshé [kun gzhi rnam shes]) produced by singling out a figure in the sensory continuum under impulse of directionality of mind (Skt. cetanā; Tib. sempa [sems pa]) may result in a wondrous experience: example of grain of sand.

i • • • • • (iv) Then the conceptualization of a steady figure may yield a condition of form (Skt. rūpa; Tib. zuk [gzugs]). (v) Then the consciousness of the passions (Skt. kliṣṭamanovijñāna; Tib. nyönyikyi namshé [nyon yid kyi rnam shes) may arise: example of coincidentally touching desirable, potential erotic partner which yields experience that precedes passionately reacting to the object (vi) Then a condition of sensuality (Skt. kāma; Tib. döpa [dod pa]) arises as one passionately reacts to a conceptualization of the object. Short-term dangers: —Confusion of sequence of base-of-all and subsequent formless condition with nonstatic nirvāṇa —“Bad trip” or so-called psychotomimetic experience that may be a precious opportunity yet rather than being used becomes a door to great trouble. Long-term Dangers: psychosis, addiction hard drugs or false gurus, right-wing political reaction. . . Potential benefits: interest in spirituality and Paths of Awakening

3 b. Approach of so-called South American Shamanism: • Explanation according to Michael Harner in Hallucinogens and Shamanism: • • everyday reality is seen as false and shamanic reality is seen as true • • and though the shaman may be able to manipulate that reality for healing of harming • • this approach involves the danger of falling under the power of the whim of unpredictable entities • • and may create negative karma when sacrifices are involved: • • contrast with practice of Chö (gcod). • • Potential benefits: ecological attitude, possibility of curing illnesses, etc.

i • • • 3 c. Stan Grof’s approach: already discussed: danger is taking saṃskṛta / modified states with nonstatic nirvāṇa potential benefit is a lessening of perinatal and other traumas. 3 d. Other approaches: for drug-addiction withdrawal and other aims • • iboga, ayahuasca, LSD and others • • Dangers and potential benefits of this approach

Types of mobility

Types of mobility Tanatologo que es

Tanatologo que es Transpersonal caring moment

Transpersonal caring moment Jean watson's theory of transpersonal caring

Jean watson's theory of transpersonal caring Transpersonal psychology

Transpersonal psychology 3 states of consciousness

3 states of consciousness Latent dreams definition

Latent dreams definition Ap psychology states of consciousness

Ap psychology states of consciousness Sleep theories ap psychology

Sleep theories ap psychology Unit 5 states of consciousness answers

Unit 5 states of consciousness answers Chapter 7 states of consciousness

Chapter 7 states of consciousness Crash course states of consciousness

Crash course states of consciousness Lesson quiz 7-1 altered states of consciousness

Lesson quiz 7-1 altered states of consciousness Ap psychology states of consciousness

Ap psychology states of consciousness Unit 5 states of consciousness

Unit 5 states of consciousness Feelings in a dream chapter 7

Feelings in a dream chapter 7 Chapter 7 altered states of consciousness

Chapter 7 altered states of consciousness There were 11

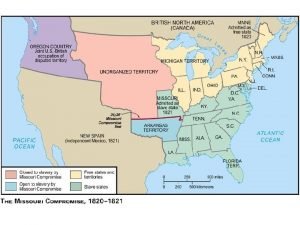

There were 11 Map of northern united states

Map of northern united states How does the constitution guard against tyranny

How does the constitution guard against tyranny Two track brain

Two track brain A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness

A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness Social influence theory of hypnosis

Social influence theory of hypnosis A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness

A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness Chapter 3 consciousness and the two-track mind

Chapter 3 consciousness and the two-track mind Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Gấu đi như thế nào

Gấu đi như thế nào Thang điểm glasgow

Thang điểm glasgow Hát lên người ơi

Hát lên người ơi Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ chạy

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng từ chạy Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

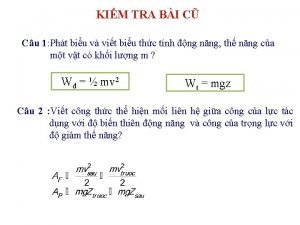

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Công của trọng lực

Công của trọng lực Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Cách giải mật thư tọa độ

Cách giải mật thư tọa độ