The Second World War was a total war

- Slides: 32

The Second World War was a total war; a long, wide-ranging conflict that caused massive social, economic and political disruption. It was a war that required the mobilisation of mass civilian populations for the ‘war effort’ – either to serve as conscripts in the armed forces, or to join the millions of workers in state-controlled industries. It was a war that demanded intense loyalty to the national cause. In all countries involved in the war, there was a huge increase in the power of the state to intervene in all aspects of society and the economy. In all countries there was a flood of propaganda to strengthen state control. In all countries there was a heightened emphasis on guarding the nation against those who were ‘politically unreliable’. The sense of an existential threat to national survival was frequently used to justify extreme measures that went far beyond what might have been done in peacetime. These extreme measures occurred mostly under the totalitarian regimes of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, but even democracies such as Britain and the United States used state power to override the liberties of their citizens. Under Hitler and Stalin mass deportations uprooted whole communities and transported them thousands of miles to remote, alien locations; millions died prematurely from overwork, harsh conditions, and even deliberate extermination. The Nazi and Soviet regimes also enforced the mass conscription of prisoners of war, political prisoners, and foreign civilians into systematic forced labour.

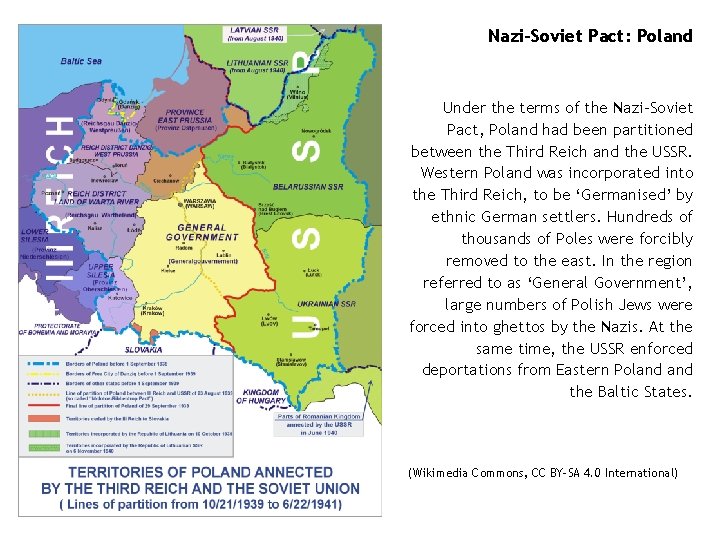

Deportations The Second World War caused many forced migrations: of refugees, prisoners of war, displaced persons made homeless or stateless by devastation left behind after the tides of war had passed on. Many of these migrations were chaotic and unplanned, but there were also numerous cases of state-organised population movements: the mass deportation of peoples moved from their homes as ‘politically unreliable’ or otherwise standing in the way of state plans for ethnic homogeneity. These mass deportations were mostly enforced by the dictatorial regimes of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia; but there were also instances on a smaller scale imposed by wartime democratic governments. The Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939 opened the way for the first waves of deportations. A week after the Pact was signed, the Third Reich invaded western Poland. This led to the mass expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Poles to the east, to allow for the ‘Germanisation’ of Polish territories annexed to the Reich. Almost simultaneously, the USSR occupied eastern Poland the Baltic States and enforced mass deportations of Poles, Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians. After the German invasion of Russia in June 1941, there were further mass deportations, including millions of Jews sent to death camps from German-occupied Europe. Millions of Soviet citizens were deported to distant parts of the USSR on Stalin’s orders. There were further deportations as the Red Army advanced westwards in 1944 -45. After the fighting ended in May 1945 Stalin ordered yet more deportations. In addition, peoples who had been occupied expelled from their borders those who had shared the same ethnic origins as the former occupiers.

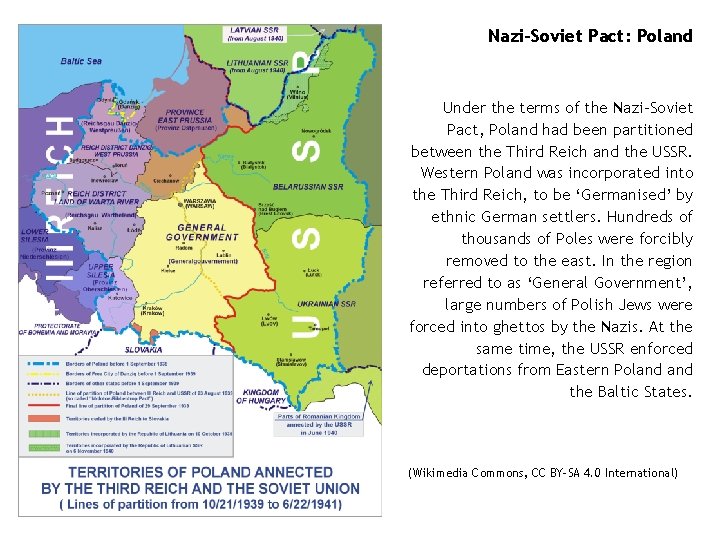

Nazi-Soviet Pact: Poland Under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, Poland had been partitioned between the Third Reich and the USSR. Western Poland was incorporated into the Third Reich, to be ‘Germanised’ by ethnic German settlers. Hundreds of thousands of Poles were forcibly removed to the east. In the region referred to as ‘General Government’, large numbers of Polish Jews were forced into ghettos by the Nazis. At the same time, the USSR enforced deportations from Eastern Poland the Baltic States. (Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4. 0 International)

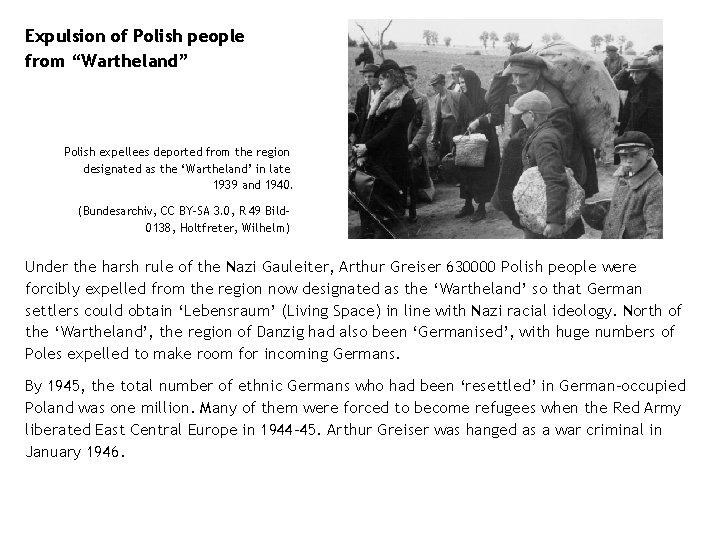

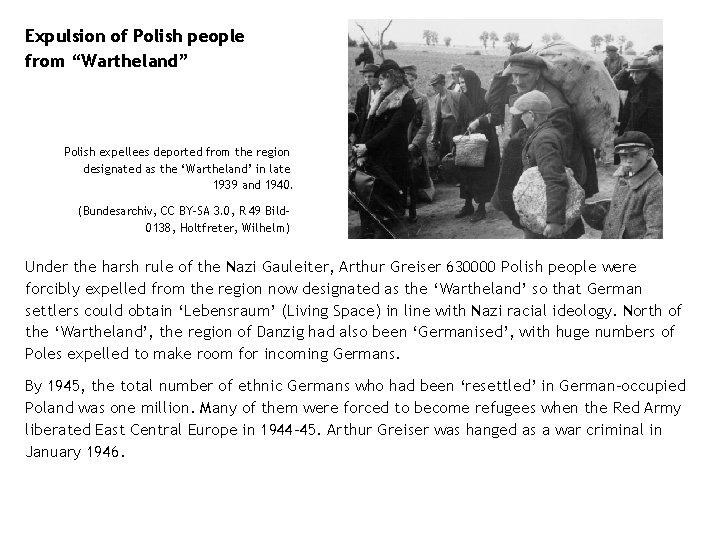

Expulsion of Polish people from “Wartheland” Polish expellees deported from the region designated as the ‘Wartheland’ in late 1939 and 1940. (Bundesarchiv, CC BY-SA 3. 0, R 49 Bild 0138, Holtfreter, Wilhelm) Under the harsh rule of the Nazi Gauleiter, Arthur Greiser 630000 Polish people were forcibly expelled from the region now designated as the ‘Wartheland’ so that German settlers could obtain ‘Lebensraum’ (Living Space) in line with Nazi racial ideology. North of the ‘Wartheland’, the region of Danzig had also been ‘Germanised’, with huge numbers of Poles expelled to make room for incoming Germans. By 1945, the total number of ethnic Germans who had been ‘resettled’ in German-occupied Poland was one million. Many of them were forced to become refugees when the Red Army liberated East Central Europe in 1944 -45. Arthur Greiser was hanged as a war criminal in January 1946.

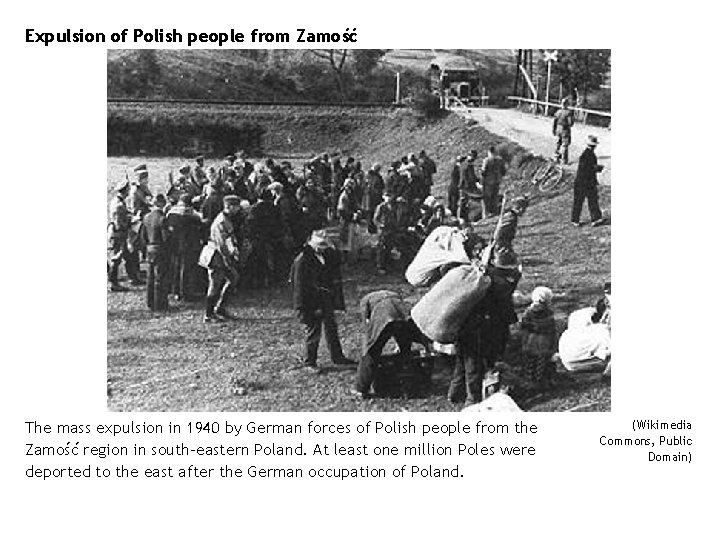

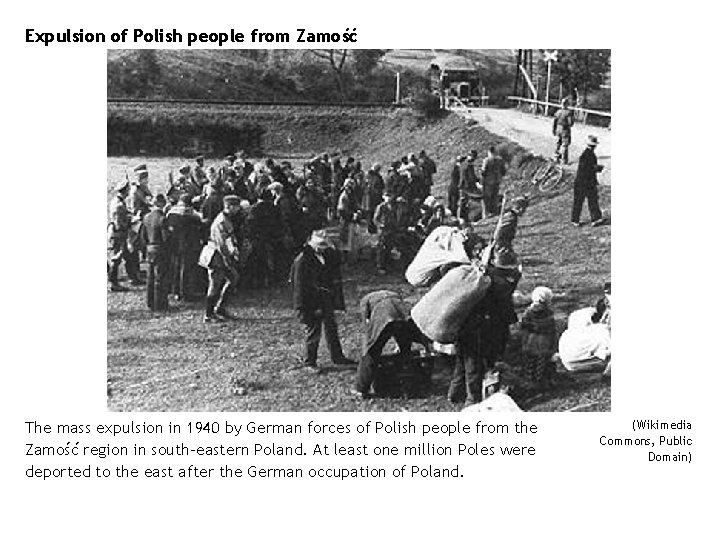

Expulsion of Polish people from Zamość The mass expulsion in 1940 by German forces of Polish people from the Zamość region in south-eastern Poland. At least one million Poles were deported to the east after the German occupation of Poland. (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Deportation of the people from the Baltic states Memorial at a disused railway platform near Riga to commemorate the place from where Latvian children were put on trains and deported to the east. (Pēters J. Vecrumba, CC BY-SA 3. 0 unported) After the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland, the USSR had also occupied the Baltic States: there was a wave of deportations of Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians, mostly to Soviet Central Asia and to Siberia. Later, between 1942 and 1944, similar deportations were enforced on ethnic minorities in the USSR, such as the Kalmyks, the Crimean Tatars, and the Black Sea Germans. Inside the USSR, the truth about the wartime deportations was suppressed until after the end of the Cold War.

Museum of the Occupation of Latvia The Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, in the Old Town of Riga, capital of Latvia (Karl Ragnar Gjertsen, CC BY-SA 3. 0 unported) What is now the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia was built for a very different purpose: erected in 1971 (at a time when the Latvian SSR was part of the Soviet Union) to salute the centenary of the birth of Lenin. Until 1991, when Latvia became independent, the museum commemorated the Latvian ‘Red Riflemen’ – Communist partisans fighting against the Nazis in 1941 -44. In 1993, the museum was remodelled. It continued to show the history of the occupation by Nazi Germany but also focused on the previously suppressed history of Soviet occupation, and the mass deportations that took place in 1940 -41 on Stalin’s orders. A similar Museum of Occupation was set up in Tallinn, capital of Estonia.

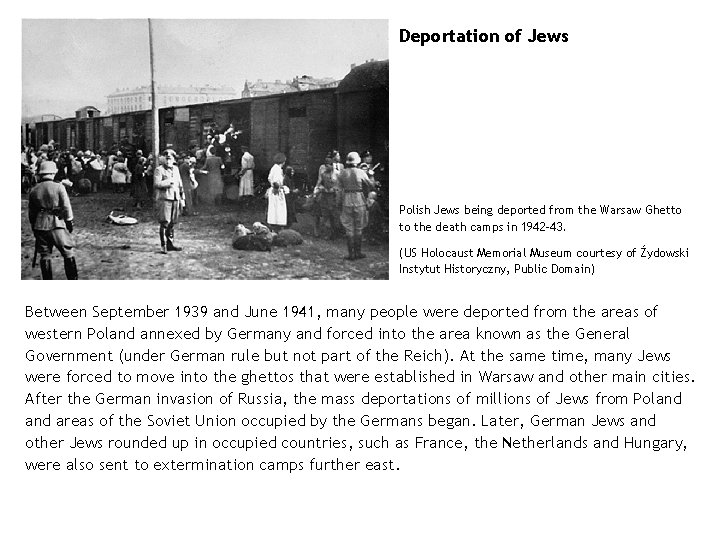

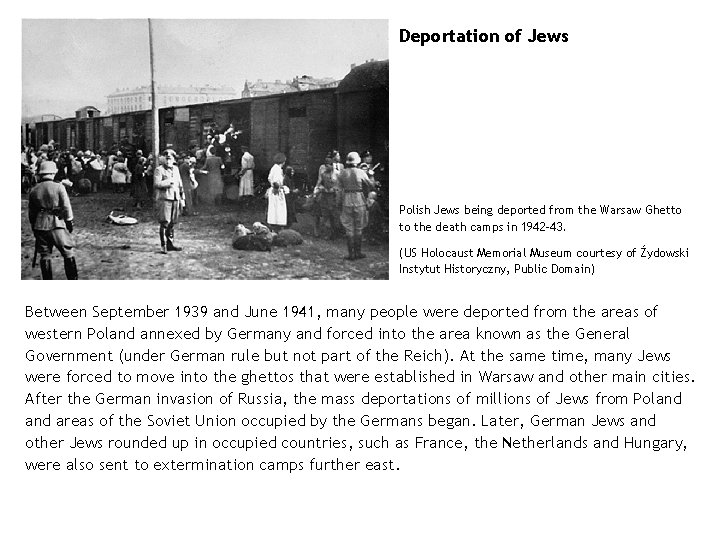

Deportation of Jews Polish Jews being deported from the Warsaw Ghetto to the death camps in 1942 -43. (US Holocaust Memorial Museum courtesy of Źydowski Instytut Historyczny, Public Domain) Between September 1939 and June 1941, many people were deported from the areas of western Poland annexed by Germany and forced into the area known as the General Government (under German rule but not part of the Reich). At the same time, many Jews were forced to move into the ghettos that were established in Warsaw and other main cities. After the German invasion of Russia, the mass deportations of millions of Jews from Poland areas of the Soviet Union occupied by the Germans began. Later, German Jews and other Jews rounded up in occupied countries, such as France, the Netherlands and Hungary, were also sent to extermination camps further east.

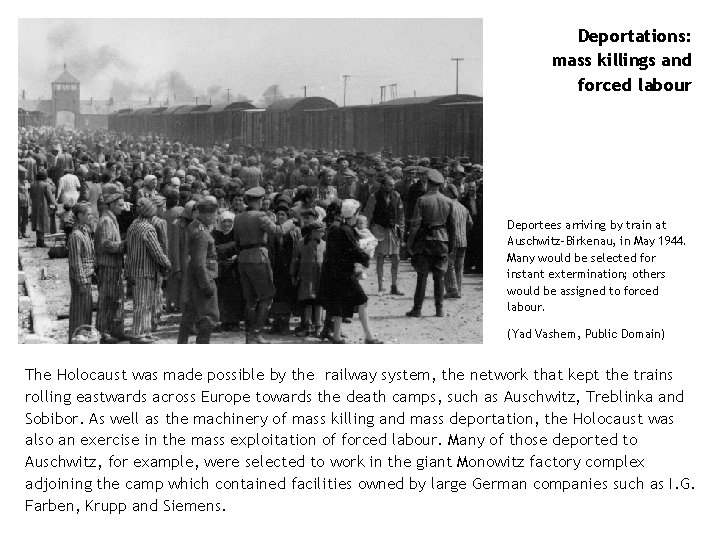

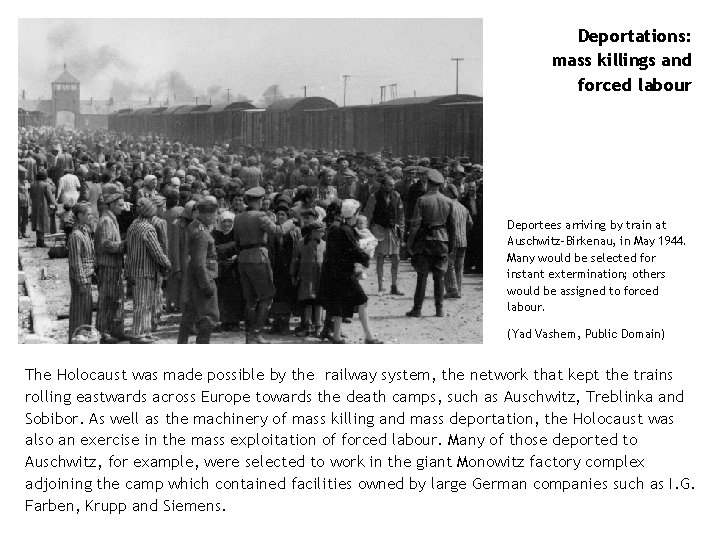

Deportations: mass killings and forced labour Deportees arriving by train at Auschwitz-Birkenau, in May 1944. Many would be selected for instant extermination; others would be assigned to forced labour. (Yad Vashem, Public Domain) The Holocaust was made possible by the railway system, the network that kept the trains rolling eastwards across Europe towards the death camps, such as Auschwitz, Treblinka and Sobibor. As well as the machinery of mass killing and mass deportation, the Holocaust was also an exercise in the mass exploitation of forced labour. Many of those deported to Auschwitz, for example, were selected to work in the giant Monowitz factory complex adjoining the camp which contained facilities owned by large German companies such as I. G. Farben, Krupp and Siemens.

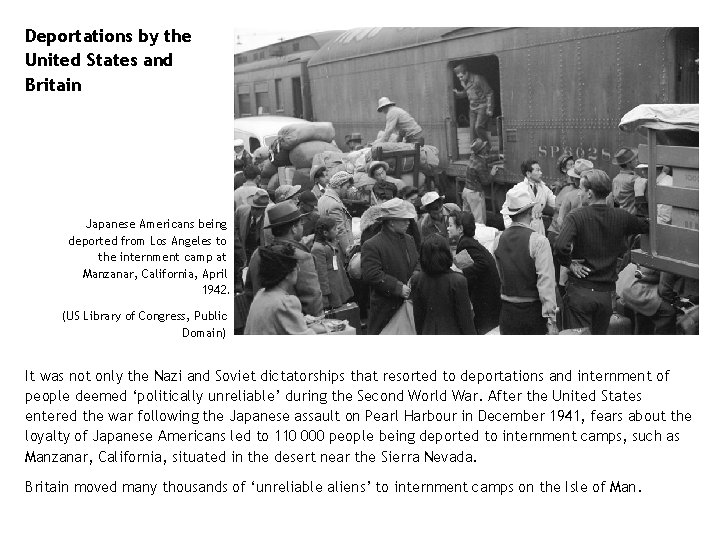

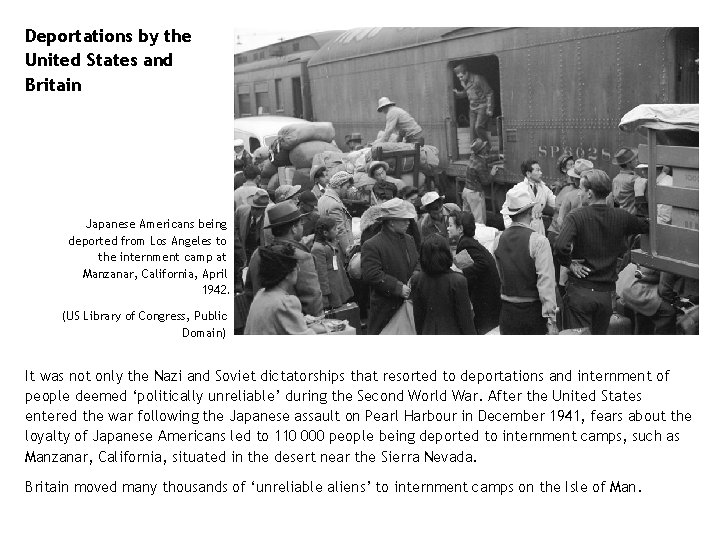

Deportations by the United States and Britain Japanese Americans being deported from Los Angeles to the internment camp at Manzanar, California, April 1942. (US Library of Congress, Public Domain) It was not only the Nazi and Soviet dictatorships that resorted to deportations and internment of people deemed ‘politically unreliable’ during the Second World War. After the United States entered the war following the Japanese assault on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, fears about the loyalty of Japanese Americans led to 110 000 people being deported to internment camps, such as Manzanar, California, situated in the desert near the Sierra Nevada. Britain moved many thousands of ‘unreliable aliens’ to internment camps on the Isle of Man.

“As the Red Army moved forward after the victory at Stalingrad in early 1943, Stalin’s security chief Lavrenty Beria recommended the deportation of whole peoples accused of collaborating with the Germans. For the most part, these were the Muslim nations of the Caucasus and Crimea. As Soviet troops retook the Caucasus, Stalin and Beria put the machine into action. On a single day in November 1943, the Soviets deported the entire Karachai population to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Over the course of two days, 28 -29 December 1943, the Soviets dispatched 92 000 Kalmyks to Siberia. Beria went to Grozny personally to supervise the deportations of Chechens and Ingush peoples in February 1944. People who could not move were shot. Leading about 120 000 special forces, Beria rounded up and expelled 479 000 people in just over a week. In April 1944, right after the Red Army reached the Crimea, Beria proposed and Stalin agreed that the entire Crimean Tatar population be resettled. 180 000 people were deported, most of them to Uzbekistan. Later in 1944, Beria had the Meshketian Turks deported from Soviet Georgia. Against this backdrop of essentially continuous national purges, Stalin’s decision to ethnically cleanse the Soviet-Polish border seems like an unsurprising development of policy. In September 1944, Stalin opted to move Poles (and Polish Jews), Ukrainians, and Belarussians back and forth across state borders in order to create ethic homogeneity. The same logic was applied, on a far greater scale, to the ethnic Germans in Poland. ” Soviet deportations and enforcing of ethnic homogeneity (Timothy Snyder (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler And Stalin. The Bodley Head, pp 330 -331. )

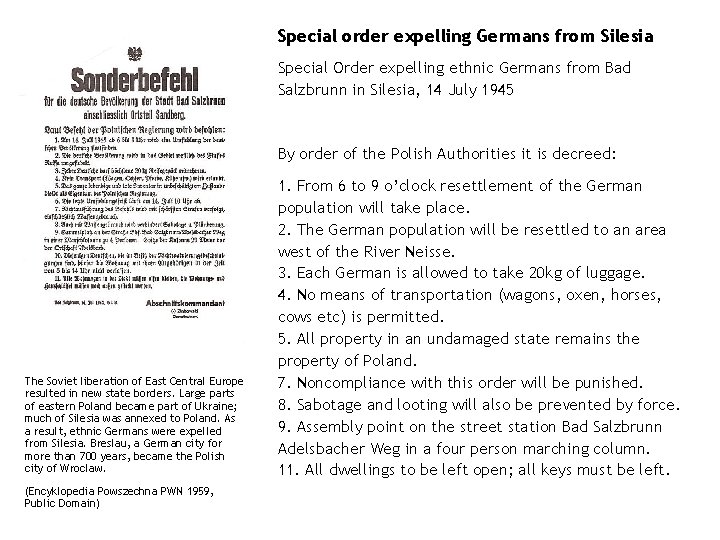

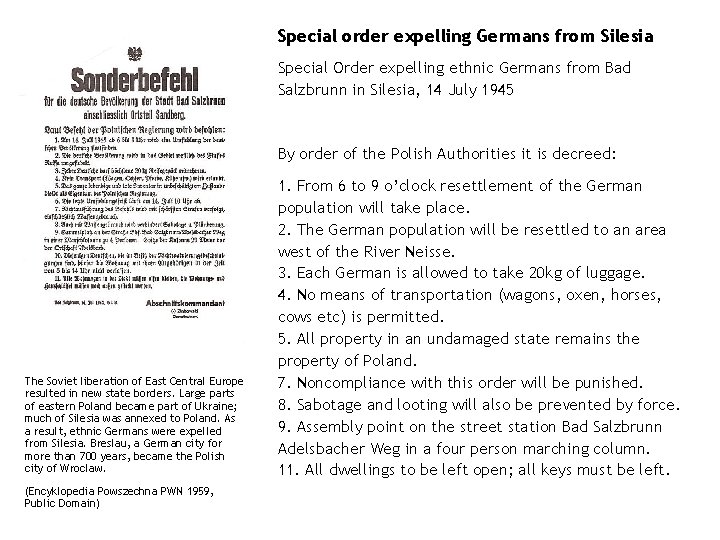

Special order expelling Germans from Silesia Special Order expelling ethnic Germans from Bad Salzbrunn in Silesia, 14 July 1945 By order of the Polish Authorities it is decreed: The Soviet liberation of East Central Europe resulted in new state borders. Large parts of eastern Poland became part of Ukraine; much of Silesia was annexed to Poland. As a result, ethnic Germans were expelled from Silesia. Breslau, a German city for more than 700 years, became the Polish city of Wroclaw. (Encyklopedia Powszechna PWN 1959, Public Domain) 1. From 6 to 9 o’clock resettlement of the German population will take place. 2. The German population will be resettled to an area west of the River Neisse. 3. Each German is allowed to take 20 kg of luggage. 4. No means of transportation (wagons, oxen, horses, cows etc) is permitted. 5. All property in an undamaged state remains the property of Poland. 7. Noncompliance with this order will be punished. 8. Sabotage and looting will also be prevented by force. 9. Assembly point on the street station Bad Salzbrunn Adelsbacher Weg in a four person marching column. 11. All dwellings to be left open; all keys must be left.

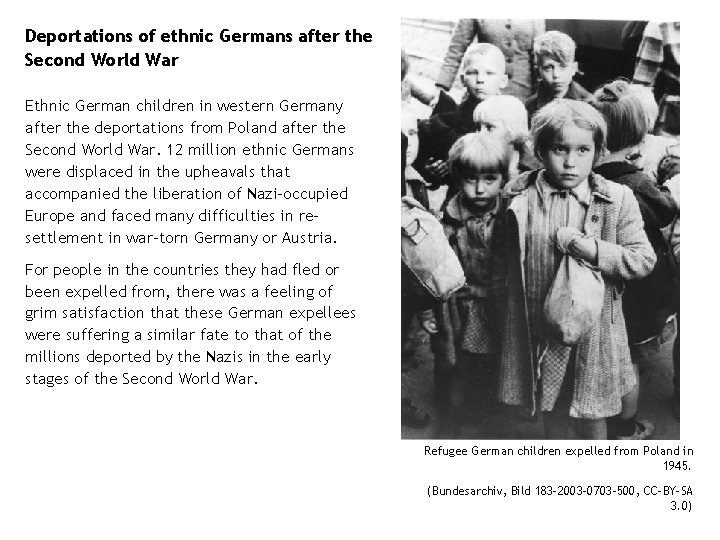

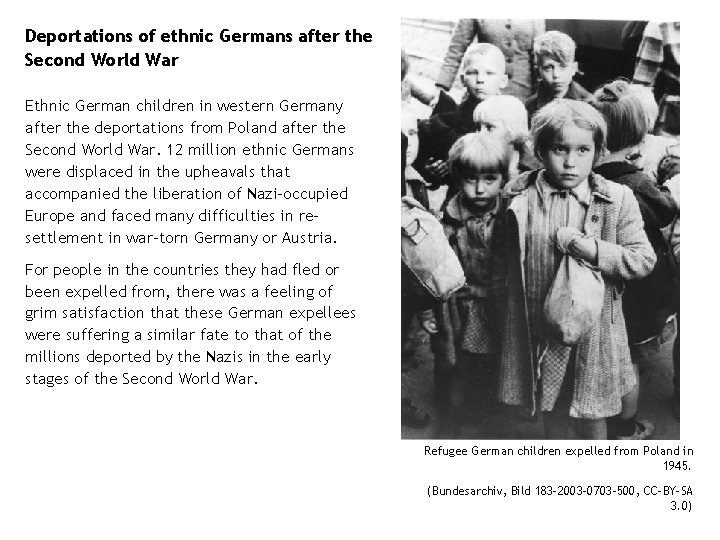

Deportations of ethnic Germans after the Second World War Ethnic German children in western Germany after the deportations from Poland after the Second World War. 12 million ethnic Germans were displaced in the upheavals that accompanied the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe and faced many difficulties in resettlement in war-torn Germany or Austria. For people in the countries they had fled or been expelled from, there was a feeling of grim satisfaction that these German expellees were suffering a similar fate to that of the millions deported by the Nazis in the early stages of the Second World War. Refugee German children expelled from Poland in 1945. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183 -2003 -0703 -500, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

Population exchange after the war The USSR and the PKWN (the pro-Communist Provisional Government of National Liberation) agreed to a massive population exchange in September 1944, to be implemented after the war. By 1946, almost 500 000 Ukrainians and more than one million Poles and Polish Jews had been forced to move by this exchange of populations Ukrainians ‘re-settled’ to the USSR in March 1946. (Wikimedia Commons courtesy of Sanok History Museum, Public Domain)

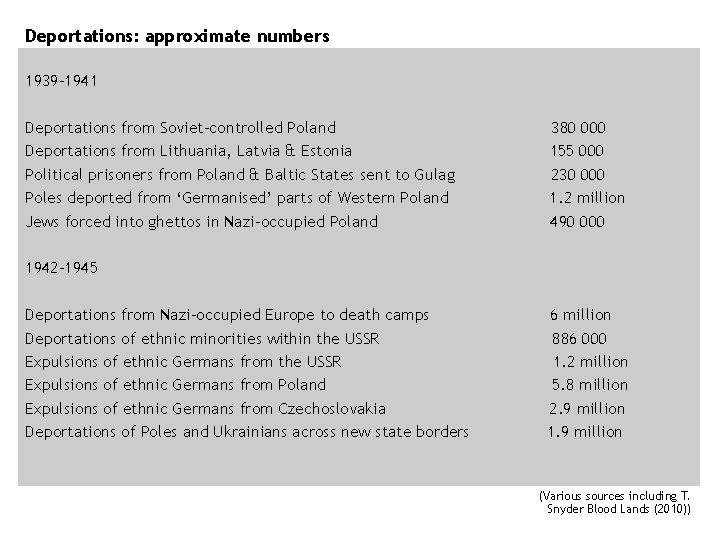

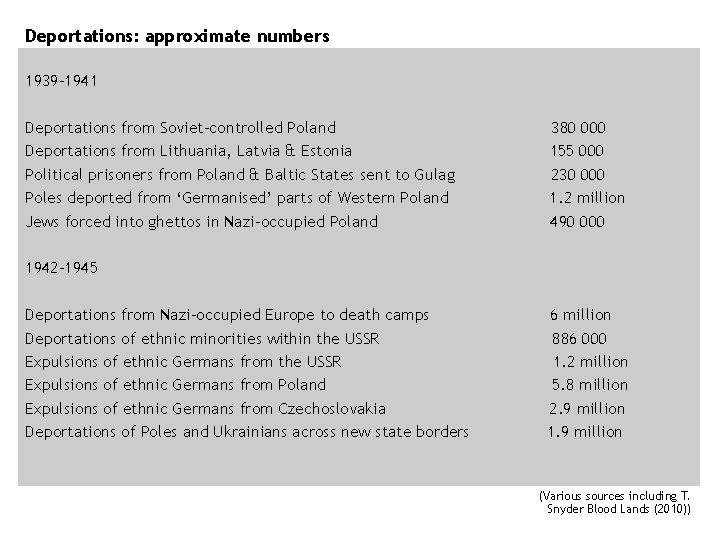

Deportations: approximate numbers 1939 -1941 Deportations from Soviet-controlled Poland Deportations from Lithuania, Latvia & Estonia Political prisoners from Poland & Baltic States sent to Gulag Poles deported from ‘Germanised’ parts of Western Poland Jews forced into ghettos in Nazi-occupied Poland 380 000 155 000 230 000 1. 2 million 490 000 1942 -1945 Deportations from Nazi-occupied Europe to death camps Deportations of ethnic minorities within the USSR Expulsions of ethnic Germans from Poland Expulsions of ethnic Germans from Czechoslovakia Deportations of Poles and Ukrainians across new state borders 6 million 886 000 1. 2 million 5. 8 million 2. 9 million 1. 9 million (Various sources including T. Snyder Blood Lands (2010))

Forced Labour The many millions conscripted into the armed forces had to be supported by a huge militaryindustrial war machine. Millions of civilian workers, particularly women, were recruited into war industries, to expand production, and to replace workers conscripted into the armed forces. Some of the belligerent countries also resorted to intensive exploitation of forced labour. In Stalin’s USSR, political prisoners in the Gulag had already been used as a labour force throughout the 1930 s, and their role as a captive work force was greatly intensified during World War 2. Many thousands of Soviet citizens were also compelled to move eastwards in 1942 -43 to build and work in the massive new industrial plants established east of the Ural mountains, beyond the reach of German air attacks. In German-occupied Europe the Third Reich conscripted huge numbers of foreign workers for German war production. Among these were nearly one million women and girls sent from occupied Ukraine to work in agriculture and domestic service in Germany. Political became a key element of Germany’s war economy as did Soviet prisoners of war. Becauprisonersse of the mass exterminations it is sometimes overlooked that many of the victimd of the holocausrt were also used as forced labour until they were unable to continue working. Also forced labour took many forms, including the sexual enslavement of women and girls to serve in the ‘comfort battalions’ that accompanied the Japanese Army.

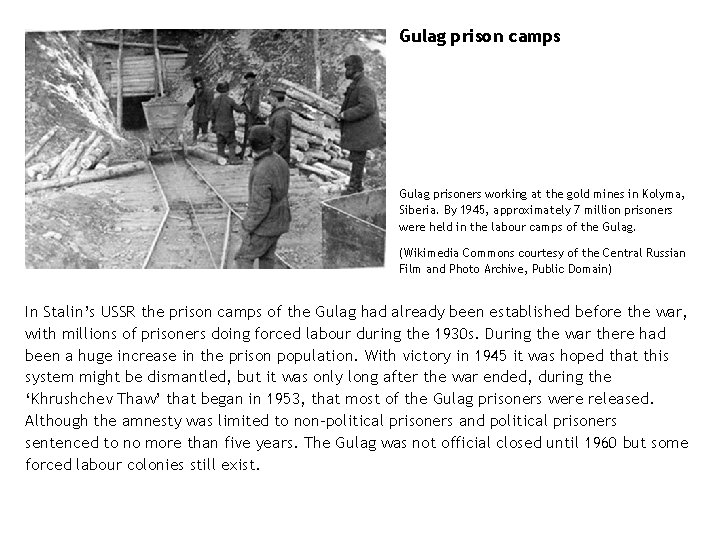

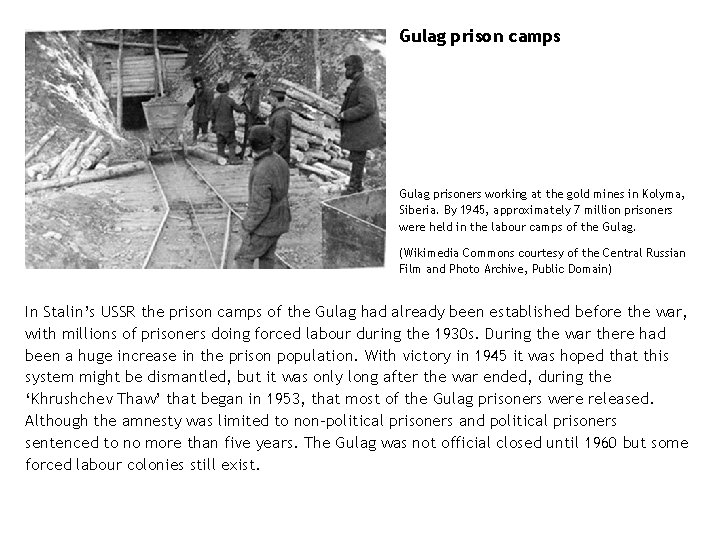

Gulag prison camps Gulag prisoners working at the gold mines in Kolyma, Siberia. By 1945, approximately 7 million prisoners were held in the labour camps of the Gulag. (Wikimedia Commons courtesy of the Central Russian Film and Photo Archive, Public Domain) In Stalin’s USSR the prison camps of the Gulag had already been established before the war, with millions of prisoners doing forced labour during the 1930 s. During the war there had been a huge increase in the prison population. With victory in 1945 it was hoped that this system might be dismantled, but it was only long after the war ended, during the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’ that began in 1953, that most of the Gulag prisoners were released. Although the amnesty was limited to non-political prisoners and political prisoners sentenced to no more than five years. The Gulag was not official closed until 1960 but some forced labour colonies still exist.

Most of the population, and therefore most of the workforce, lived and worked in European Russia, Ukraine and Byelorussia. It was precisely these areas that were most directly threatened by the German invasion. Much of Soviet industry was endangered by the German advance, and so the Soviets undertook a titanic effort to dismantle their factories and transport them to safer sectors in Siberia and the Caucasus. The transfer was conducted astonishingly quickly. It was the expensive specialized machinery, the capital investment of the factory, that needed protection, and these were hauled to safety along the main rail lines, generally along with the workers trained to do the work of the factory. (Fassbender, M. (2014). The Transfer of Soviet Factories During World War II) Relocation of Soviet industry and workforce Evacuation of industrial plants from European Russia became urgent in August 1941. Many factories were dismantled and moved east. Railroads made this vast relocation of industry possible: 3000 trains per day took steel factory equipment from the Dnieper area; 25 000 wagons in one week shifted factories from Ukraine; 80 000 wagons moved 500 factories from Moscow. Technically, workers relocated to the east were not ‘forced’, but they were under strict state control, and working conditions were extremely harsh.

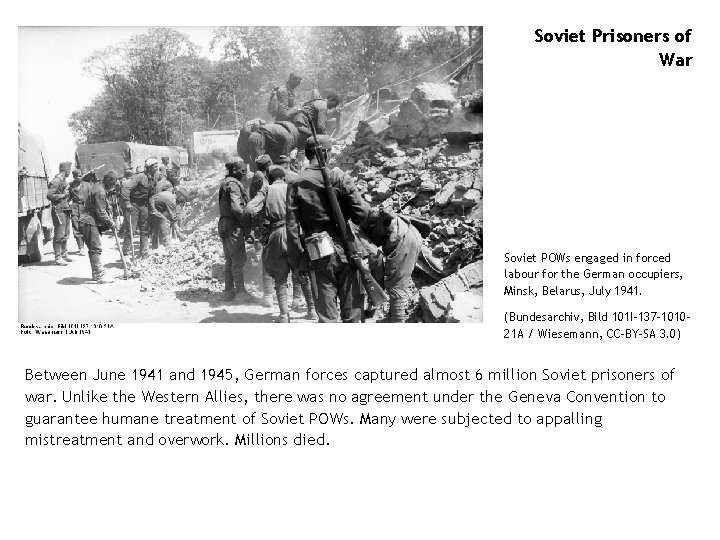

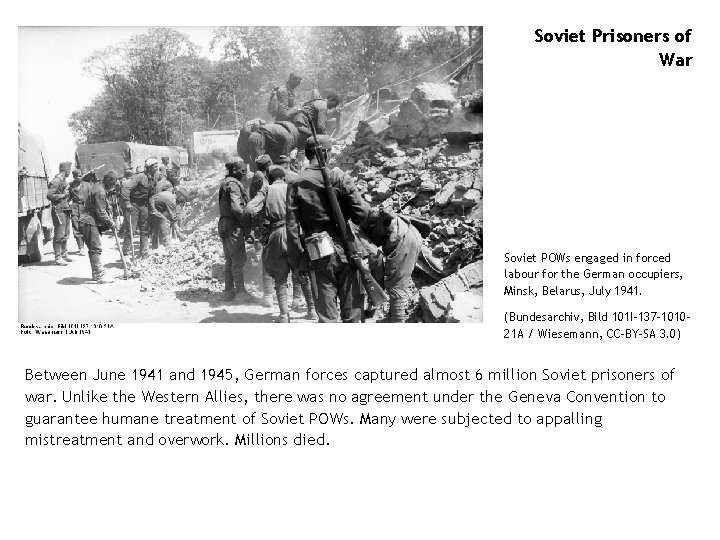

Soviet Prisoners of War Soviet POWs engaged in forced labour for the German occupiers, Minsk, Belarus, July 1941. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 101 I-137 -101021 A / Wiesemann, CC-BY-SA 3. 0) Between June 1941 and 1945, German forces captured almost 6 million Soviet prisoners of war. Unlike the Western Allies, there was no agreement under the Geneva Convention to guarantee humane treatment of Soviet POWs. Many were subjected to appalling mistreatment and overwork. Millions died.

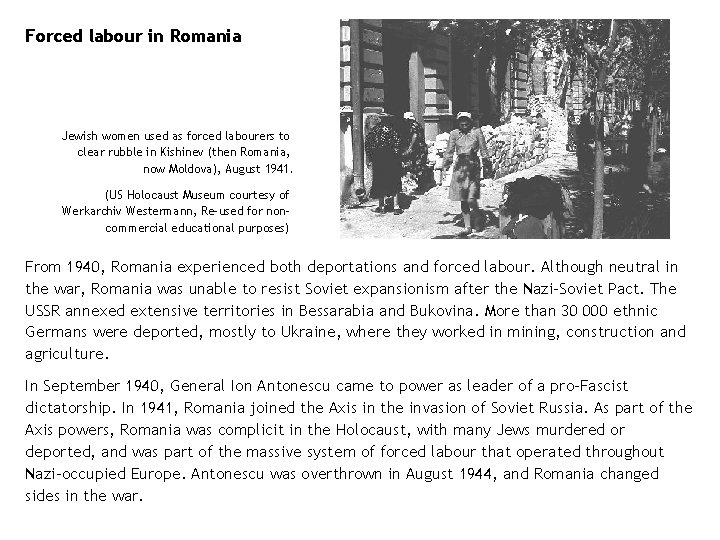

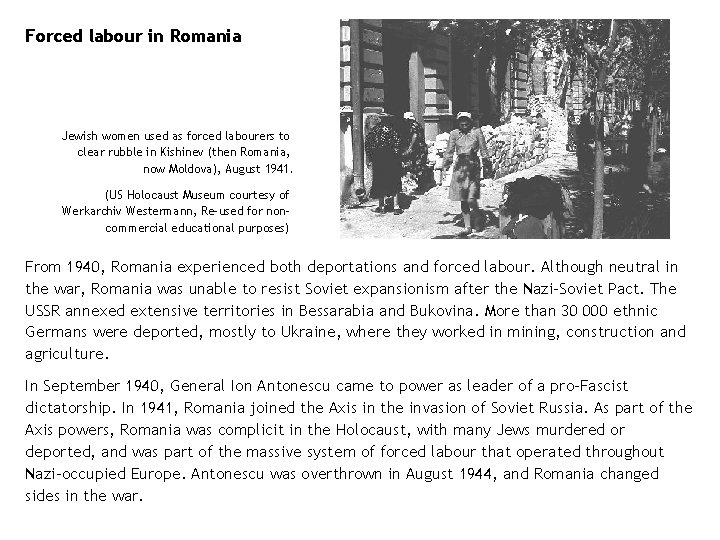

Forced labour in Romania Jewish women used as forced labourers to clear rubble in Kishinev (then Romania, now Moldova), August 1941. (US Holocaust Museum courtesy of Werkarchiv Westermann, Re-used for noncommercial educational purposes) From 1940, Romania experienced both deportations and forced labour. Although neutral in the war, Romania was unable to resist Soviet expansionism after the Nazi-Soviet Pact. The USSR annexed extensive territories in Bessarabia and Bukovina. More than 30 000 ethnic Germans were deported, mostly to Ukraine, where they worked in mining, construction and agriculture. In September 1940, General Ion Antonescu came to power as leader of a pro-Fascist dictatorship. In 1941, Romania joined the Axis in the invasion of Soviet Russia. As part of the Axis powers, Romania was complicit in the Holocaust, with many Jews murdered or deported, and was part of the massive system of forced labour that operated throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. Antonescu was overthrown in August 1944, and Romania changed sides in the war.

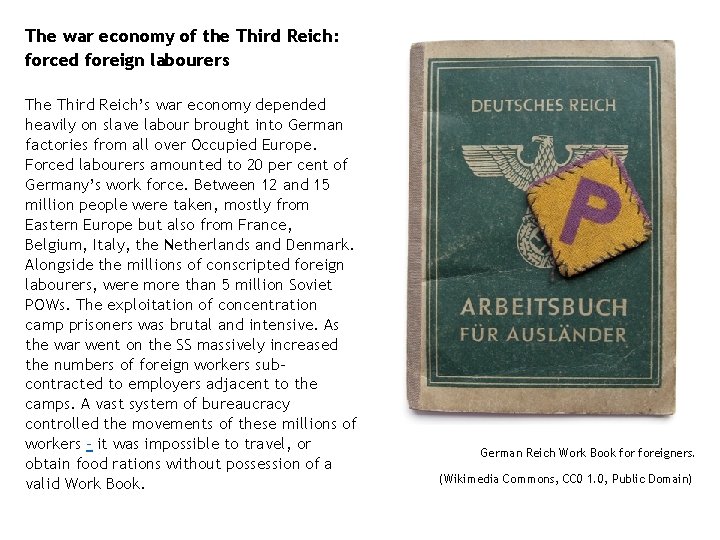

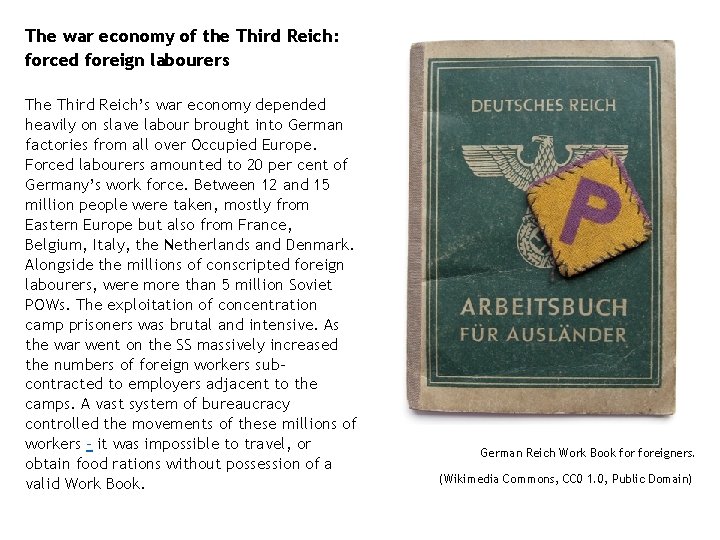

The war economy of the Third Reich: forced foreign labourers The Third Reich’s war economy depended heavily on slave labour brought into German factories from all over Occupied Europe. Forced labourers amounted to 20 per cent of Germany’s work force. Between 12 and 15 million people were taken, mostly from Eastern Europe but also from France, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark. Alongside the millions of conscripted foreign labourers, were more than 5 million Soviet POWs. The exploitation of concentration camp prisoners was brutal and intensive. As the war went on the SS massively increased the numbers of foreign workers subcontracted to employers adjacent to the camps. A vast system of bureaucracy controlled the movements of these millions of workers – it was impossible to travel, or obtain food rations without possession of a valid Work Book. German Reich Work Book foreigners. (Wikimedia Commons, CC 0 1. 0, Public Domain)

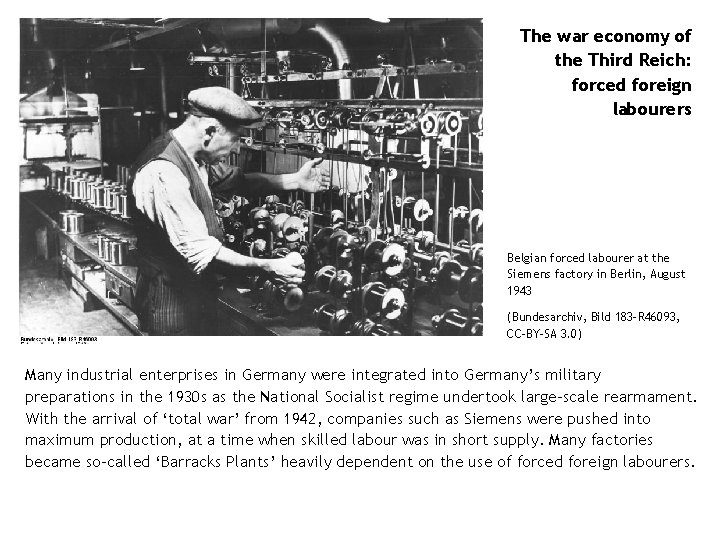

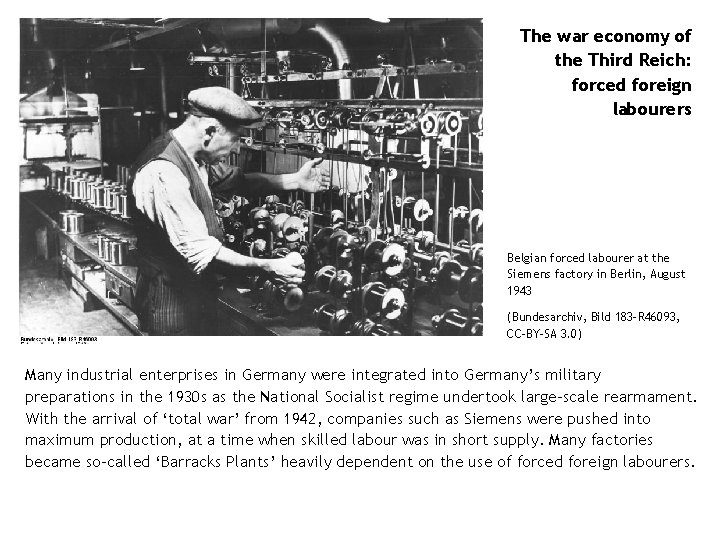

The war economy of the Third Reich: forced foreign labourers Belgian forced labourer at the Siemens factory in Berlin, August 1943 (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183 -R 46093, CC-BY-SA 3. 0) Many industrial enterprises in Germany were integrated into Germany’s military preparations in the 1930 s as the National Socialist regime undertook large-scale rearmament. With the arrival of ‘total war’ from 1942, companies such as Siemens were pushed into maximum production, at a time when skilled labour was in short supply. Many factories became so-called ‘Barracks Plants’ heavily dependent on the use of forced foreign labourers.

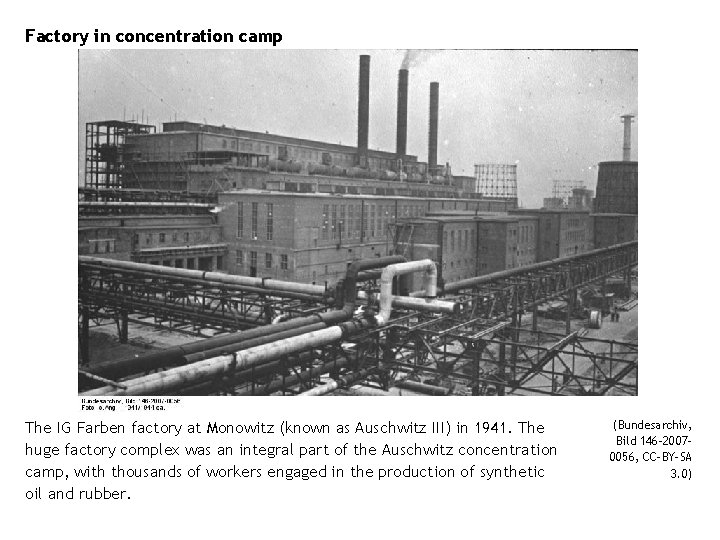

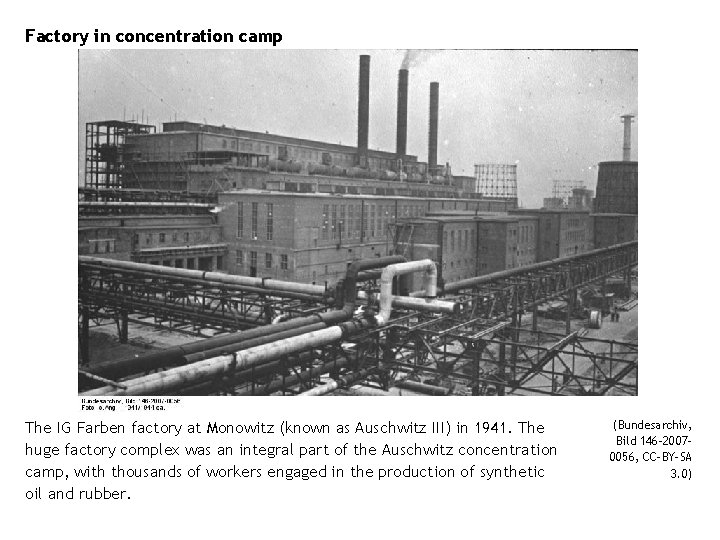

Factory in concentration camp The IG Farben factory at Monowitz (known as Auschwitz III) in 1941. The huge factory complex was an integral part of the Auschwitz concentration camp, with thousands of workers engaged in the production of synthetic oil and rubber. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 146 -20070056, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

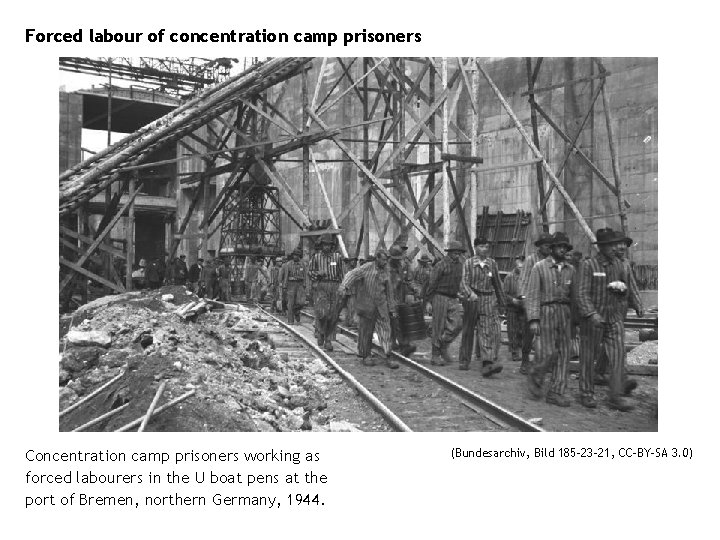

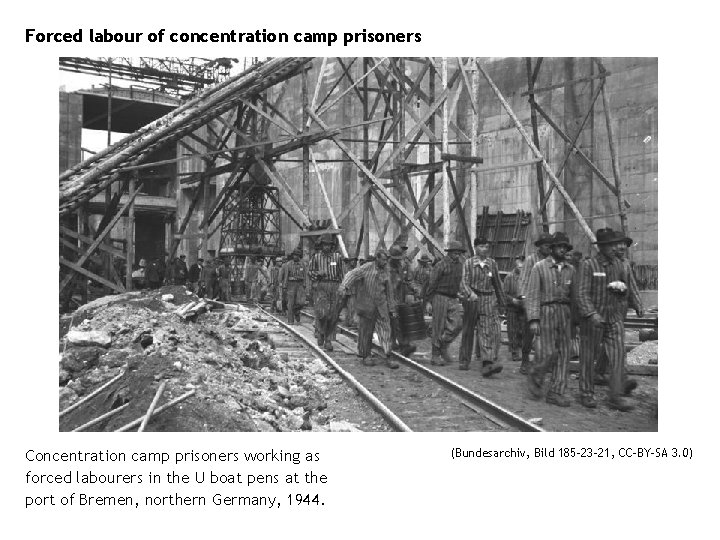

Forced labour of concentration camp prisoners Concentration camp prisoners working as forced labourers in the U boat pens at the port of Bremen, northern Germany, 1944. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 185 -23 -21, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

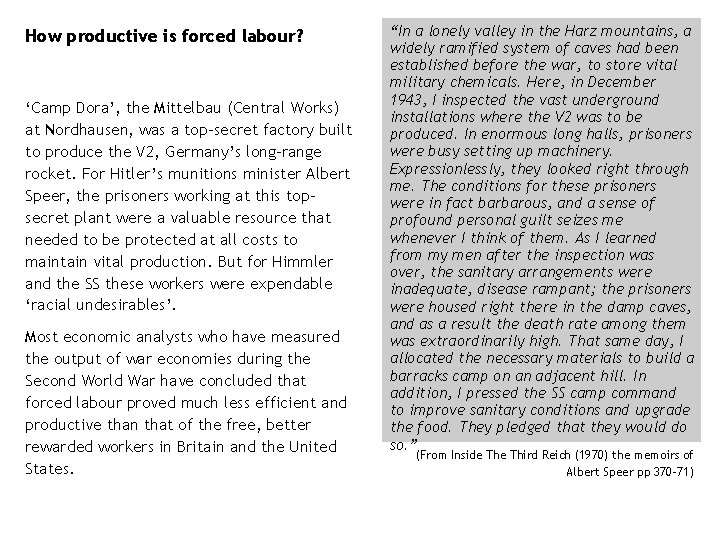

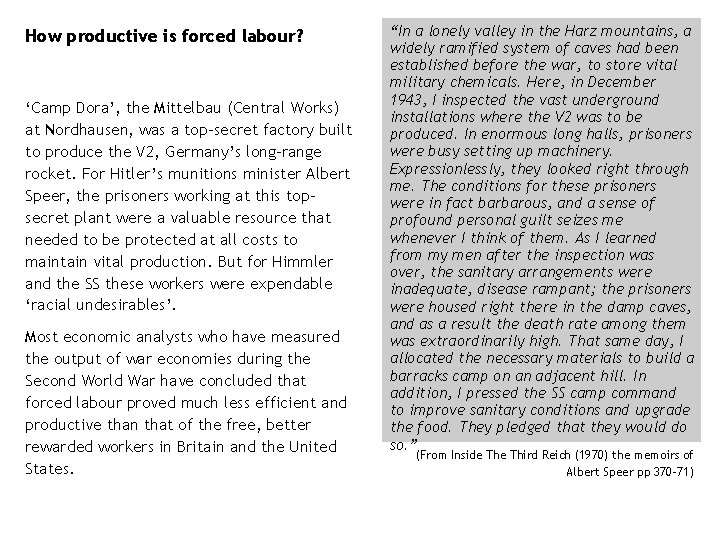

How productive is forced labour? ‘Camp Dora’, the Mittelbau (Central Works) at Nordhausen, was a top-secret factory built to produce the V 2, Germany’s long-range rocket. For Hitler’s munitions minister Albert Speer, the prisoners working at this topsecret plant were a valuable resource that needed to be protected at all costs to maintain vital production. But for Himmler and the SS these workers were expendable ‘racial undesirables’. Most economic analysts who have measured the output of war economies during the Second World War have concluded that forced labour proved much less efficient and productive than that of the free, better rewarded workers in Britain and the United States. “In a lonely valley in the Harz mountains, a widely ramified system of caves had been established before the war, to store vital military chemicals. Here, in December 1943, I inspected the vast underground installations where the V 2 was to be produced. In enormous long halls, prisoners were busy setting up machinery. Expressionlessly, they looked right through me. The conditions for these prisoners were in fact barbarous, and a sense of profound personal guilt seizes me whenever I think of them. As I learned from my men after the inspection was over, the sanitary arrangements were inadequate, disease rampant; the prisoners were housed right there in the damp caves, and as a result the death rate among them was extraordinarily high. That same day, I allocated the necessary materials to build a barracks camp on an adjacent hill. In addition, I pressed the SS camp command to improve sanitary conditions and upgrade the food. They pledged that they would do so. ” (From Inside Third Reich (1970) the memoirs of Albert Speer pp 370 -71)

“Convicted skilled craftsmen (many of them Jewish) were traced among the prison population and sent to KL Sachsenhausen, the concentration camp north of Berlin to work on the top-secret production of forged bank notes. The unit was controlled by Major Bernhard Kruger (hence the new code name Operation Bernhard). The total value of the British bank notes (mostly £ 5 notes, or ‘white fivers’) produced by 1945 was perhaps as high as £ 300 million. Work was also begun on counterfeiting US dollars. Some of the counterfeit money was used to pay German spies, and to buy information that helped the German operation to free Mussolini from captivity in 1943. Early in 1945, as Germany was being invaded both from east and west, the counterfeiters were moved to a safer location at KL Mauthausen, near Linz in Upper Austria, but they then had to move again – to tunnels under the mountains. With Germany close to final defeat, the unit was moved yet again, to KL Ebensee; SS guards had orders that the forgers were to be executed, to avoid them falling in to enemy hands. These orders were not carried out, and the men were liberated by the Americans. Vast amounts of bank notes, and the printing plates that produced them, were hidden in lakes in the mountains south of Salzburg. The original master plan never really succeeded; but enough ‘perfect’ counterfeit bank notes were in circulation by 1945 that the Bank of England had to switch to a new, different design than the ‘white fivers’. ” Operation Bernhard (The story has been told in a book OPERATION BERNHARD by Anthony Pirie (1988) and an Austrian feature film, THE COUNTERFEITERS (DIE FALSCHER) made in 2007)

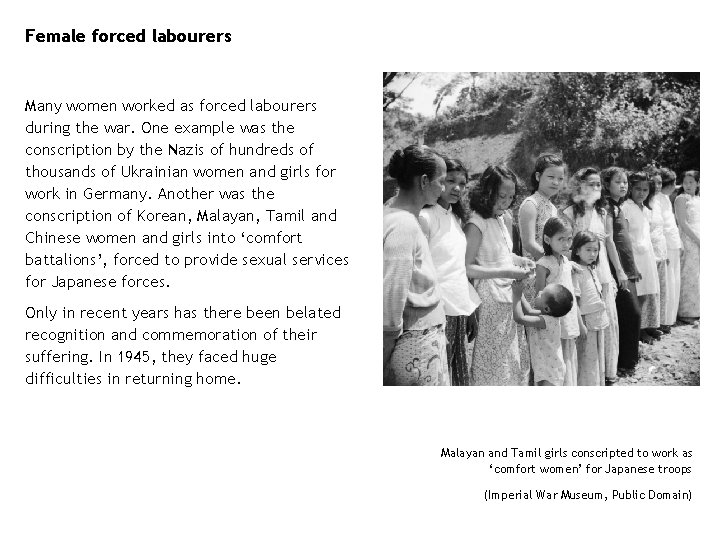

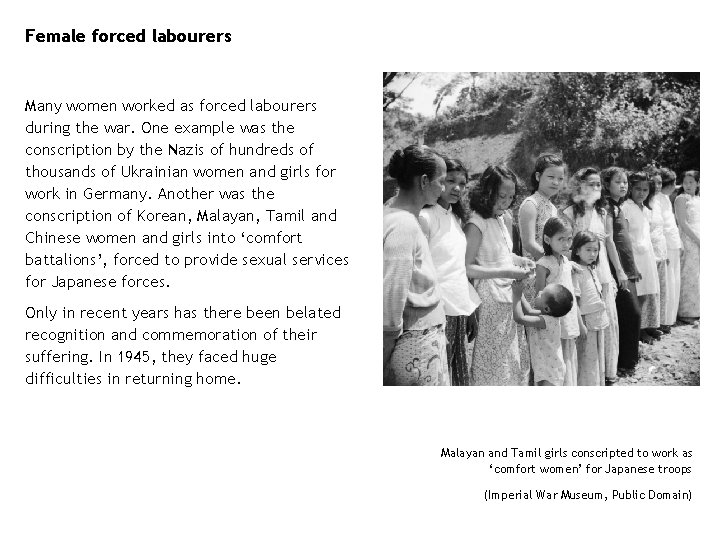

Female forced labourers Many women worked as forced labourers during the war. One example was the conscription by the Nazis of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian women and girls for work in Germany. Another was the conscription of Korean, Malayan, Tamil and Chinese women and girls into ‘comfort battalions’, forced to provide sexual services for Japanese forces. Only in recent years has there been belated recognition and commemoration of their suffering. In 1945, they faced huge difficulties in returning home. Malayan and Tamil girls conscripted to work as ‘comfort women’ for Japanese troops (Imperial War Museum, Public Domain)

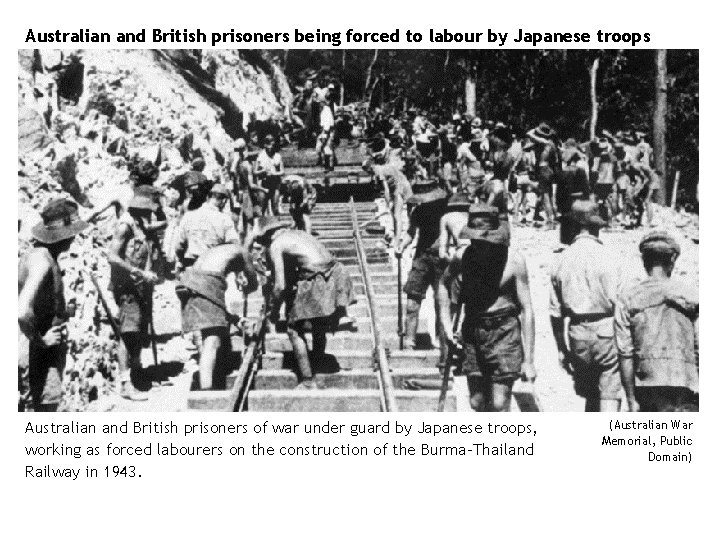

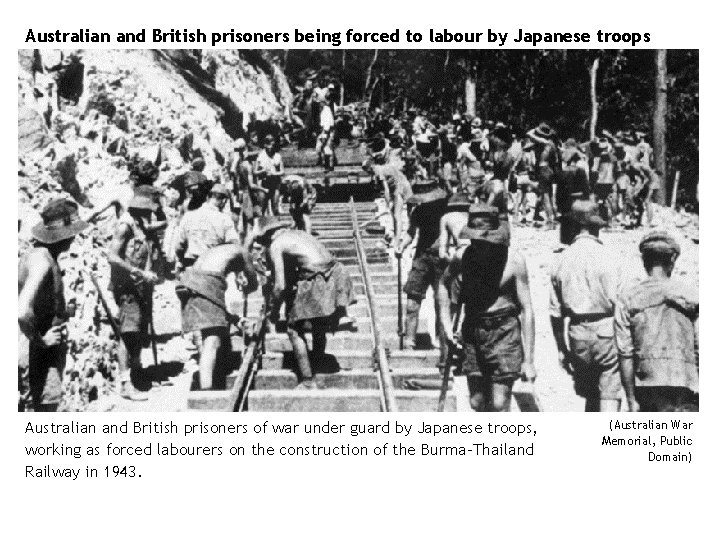

Australian and British prisoners being forced to labour by Japanese troops Australian and British prisoners of war under guard by Japanese troops, working as forced labourers on the construction of the Burma-Thailand Railway in 1943. (Australian War Memorial, Public Domain)

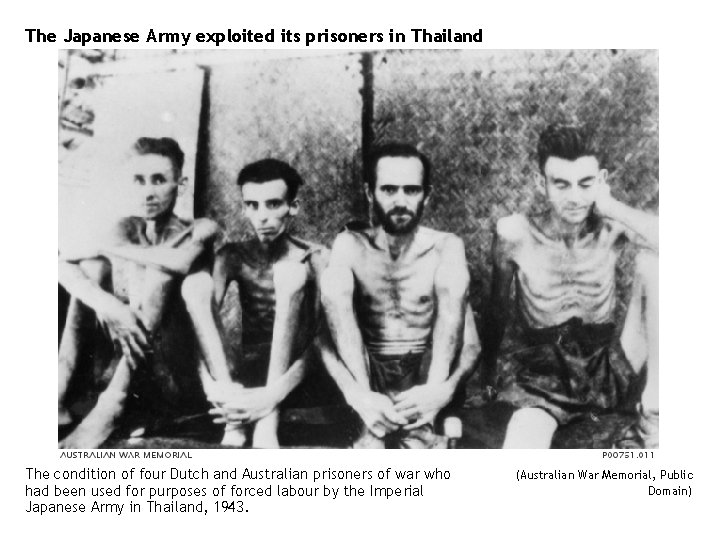

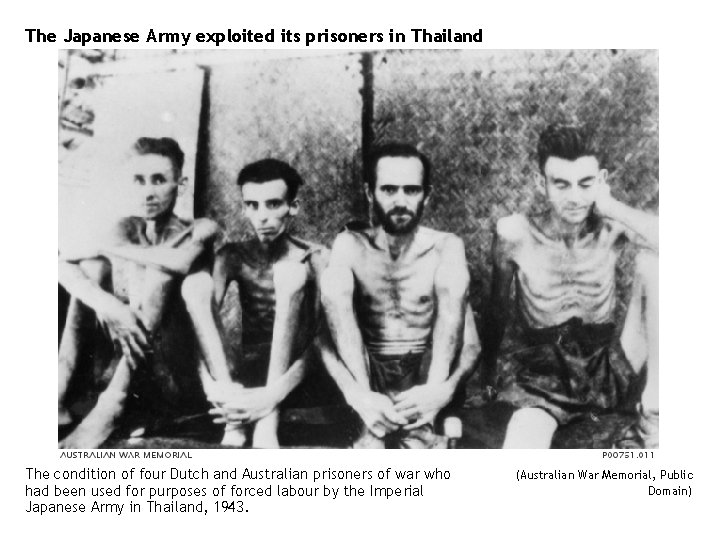

The Japanese Army exploited its prisoners in Thailand The condition of four Dutch and Australian prisoners of war who had been used for purposes of forced labour by the Imperial Japanese Army in Thailand, 1943. (Australian War Memorial, Public Domain)

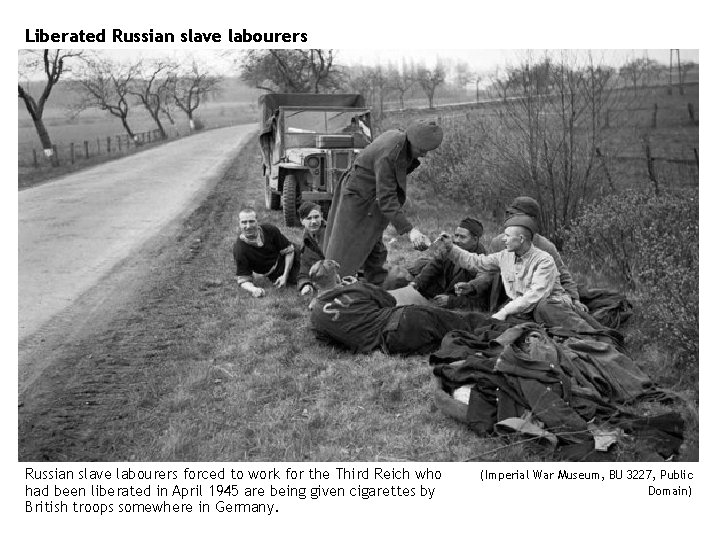

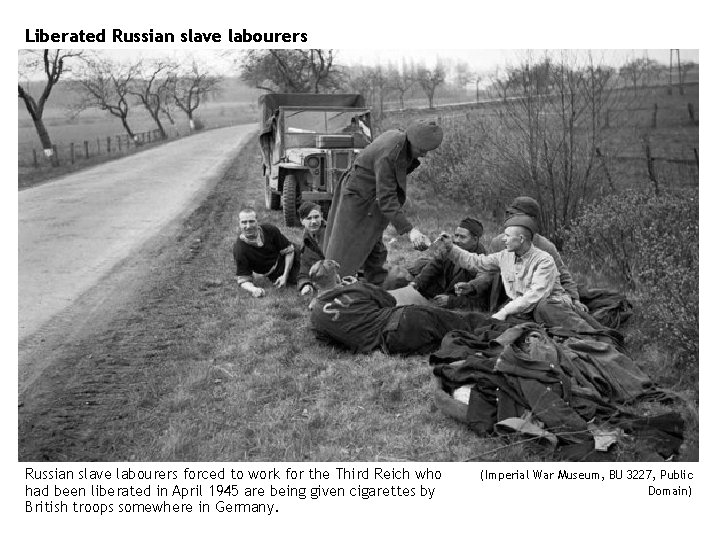

Liberated Russian slave labourers forced to work for the Third Reich who had been liberated in April 1945 are being given cigarettes by British troops somewhere in Germany. (Imperial War Museum, BU 3227, Public Domain)

Consequences At the end of the war, returning these people to their home countries was a huge logistical problem. More than 5 million foreign workers and POWs were repatriated to the Soviet Union, 1. 5 million to Poland, and 1. 5 million to France. Nearly 1 million went back to Italy, and hundreds of thousands to countries such as Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Hungary and Yugoslavia. At first, many foreign workers were simply cast adrift. Later the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was set up to coordinate repatriation, providing food and temporary accommodation to those seeking to return home. For many people, returning home was difficult, dangerous, or impossible. Many suffered ill-health after years of mistreatment. Many Soviet citizens faced imprisonment or death for having ‘collaborated’ with the enemy, even though in reality they had been prisoners of war and slave labourers of the Third Reich.

Deportations and forced labour This collection has been made by Laura Steenbrink, Joyce Schaftlein and Chris Rowe of the Historiana team. SUPPORTED BY COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE EUROCLIO has tried to contact all copyright holders of materials published on Historiana. Please contact copyright@historiana. eu in case you find that materials have been unrightfully used. License: CC-BY-SA 4. 0, Historiana DISCLAIMER (Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain) The European Commission support for this publication does not constitute of an endorsement of the contents which reflects the view only of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained herein. DEVELOPED BY