PERANCANGAN DAN IMPLEMENTASI ASESMEN RESIKO PERENCANAAN DAN PROSEDUR

- Slides: 20

PERANCANGAN DAN IMPLEMENTASI ASESMEN RESIKO, PERENCANAAN DAN PROSEDUR PEMULIHAN DATA PERTEMUAN Ke - 12 Ir. Nizirwan Anwar, MT Manajemen Informasi Kesehatan Fakultas Ilmu Kesehatan

LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Define a client registry and describe why such registries are needed in health information exchange. • Detail common strategies for implementing a client registry. • Discuss common challenges encountered when implementing a client registry. • Highlight the critical role a unique identifier plays in implementing a client registry. • Distinguish between the common methods of patient matching.

PATIENT IDENTIFIERS EHR systems manage records. Much of the information maintained in EHR systems pertains to patients—or clients—who receive health care services from a clinic or hospital. In order to effectively manage information about patients, EHR systems must assign and use patient identifiers, such as a medical record number (MRN), when performing tasks such as creating a new record, updating an existing record, or deleting a record. Identifiers (or IDs) ensure that the correct record is added, updated, or deleted. Patient identifiers can be thought of as belonging to two general classes: (1) a unique code or set of codes specifically designed to uniquely identify a patient in a given system and (2) an aggregate set of demographic and related attributes used to describe a patient uniquely, such as name, sex, date of birth, address, etc. Whether utilizing existing or creating new patient identifiers, it is prudent to understand the context in which the identifiers will be deployed.

UNIQUE PATIENT IDENTIFIERS Strategy for Assigning UPIs A UPI requires a sequence allocation sufficiently large to cover an entire population over time, theoretically for as long as the number will be in use. Sequencing schemes available for development of a UPI generally fall into three numbering systems: serial, derived, and composite. • In serial numbering systems, each individual is assigned a number from a central location. These numbers are automated and do not assimilate any nonunique characteristics of the individual. England’s National Health Service number is an example of serial numbering system, with some added functionality. • As the name suggests, derived numbering systems create a number based on, or derived from, a personal trait of the individual. In contrast to serial numbering, assignment of a derived number can take place anywhere but runs the risk of failing to be unique when derived from a personal trait which is shared by other individuals. • Composite numbering systems assign part of the number from a central location and the other part is derived from personal traits, thus represents a combination of the serial and derived systems.

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers Much of the concern around utilizing a universal identifier for health care, particularly in the United States, is fear of malicious intent in the event of a data breach. The only true way to prevent the possibility of confidentiality breaches is to exclude personal information; such as name, social security number (SSN), date of birth, etc. , and to eliminate the possibility of linking the health care identifier to databases which contain personal information. At the time of writing, and for the foreseeable future, no identifier exists which will perfectly ascertain all individuals uniquely across all scopes of health care; at least not one that is neither physically invasive (eg, implanted device) nor invasive of a citizen’s right to privacy. Health care identifiers are often assigned within individual information systems (eg, laboratory, radiology) as well as organization-wide (eg, MRN). However, as discussed, these identifiers are meaningless outside of the domain in which they operate. One solution to this identity challenge is to establish a unique identifier that crosses organizational boundaries. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), which is a standards development organization accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), describes 30 criteria which should be used to evaluate the efficacy of a candidate identifier.

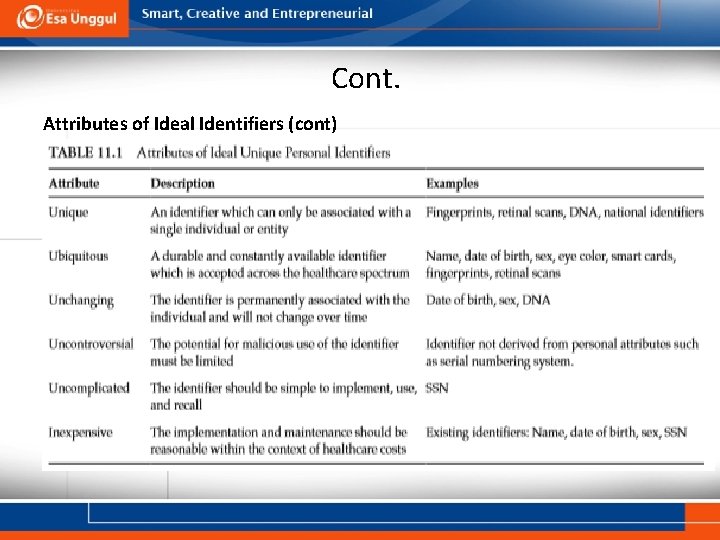

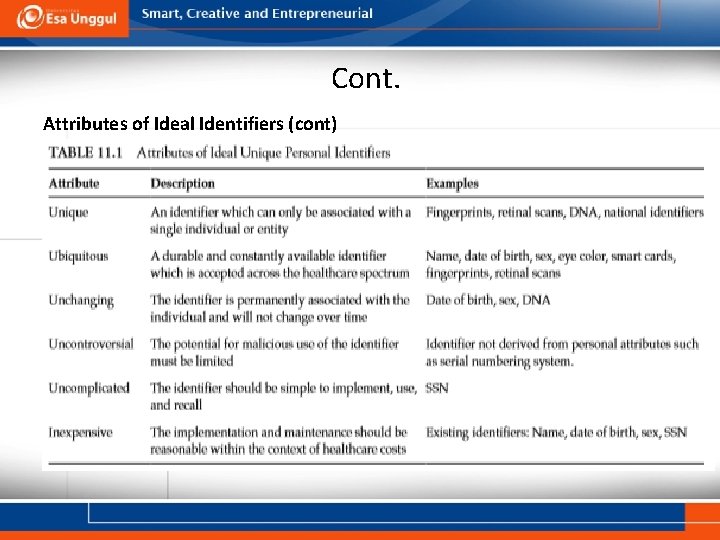

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers (cont) Meeting all of the proposed criteria would lead to a UPI that achieves the following: • positively identifies patients. • automatically links and collates patient records from disparate electronic sources, creating a longitudinal care record, • protects patient’s personal health information and privacy, • effectively minimizes the cost of patient record management. No identifier exists which could meet all of the criteria proposed by the standard because some ideal attributes conflict with each other. For example, a ubiquitous and easily accessible identifier may not adequately preserve privacy. The following is a description of selected ideal UPI attributes; for succinct definitions and examples, refer to Table 11. 1.

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers (cont) Meeting all of the proposed criteria would lead to a UPI that achieves the following: • positively identifies patients. • automatically links and collates patient records from disparate electronic sources, creating a longitudinal care record, • protects patient’s personal health information and privacy, • effectively minimizes the cost of patient record management. No identifier exists which could meet all of the criteria proposed by the standard because some ideal attributes conflict with each other. For example, a ubiquitous and easily accessible identifier may not adequately preserve privacy. The following is a description of selected ideal UPI attributes; for succinct definitions and examples, refer to Table 11. 1.

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers (cont)

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers (cont) • • • A unique identifier, by definition, can never be associated with more than one individual. That is, once assigned, the possibility of another person being assigned the same number must be eliminated, or infinitely minuscule. A ubiquitous identifier is available and accepted across the health care spectrum. For example, a nonubiquitous identifier would identify a patient for a hospitalization but not the subsequent primary care visit. Ubiquity also requires the identifier to be durable and made readily available at the time of service. Unchanging. In order for an individual identifier to be effective, every individual should have an identifier that applies only to that individual and does not change over time. This requires foresight on the part of the issuing agency because enough numbers must be generated to support the population throughout the life span of the identifier.

Cont. Attributes of Ideal Identifiers (cont) • • • Uncontroversial. The identifier should help minimize the opportunities for crime and abuse and should not contain substantive information about the individual. Similarly, the various stakeholders must perceive the identifier to be minimally invasive. The subjectivity of what is and is not invasive makes universal acceptance difficult, if not impossible. Uncomplicated. An identifier or identifier system that is not practical to implement or that does not meet the requirements of administrative simplification must be deemed unacceptable. Inexpensive. The costs of implementation and use of the identifier must be within an acceptable range. Analysis of costs across all health care settings should be considered including, patients, providers, payers, and government agencies. For example, it has been estimated that a national health identifier implemented in the United States would cost between $4. 9 and $12. 2 billion to deploy and $1. 5 billion per year, which many view as unsustainable

Cont. Existing Unique Patient Identifiers The Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) recognized the need to uniquely identify patients for managing care and administrative purposes, thus proposing a unique health identifier for all individuals. UPIs have been implemented in several international health care systems but have yet to come to fruition in the United States for a number of reasons: a funding embargo imposed by Congress; costs to implement such a system; privacy concerns; difficulties in conforming existing information systems to utilize the identifier; and a lack of consensus on selection of an identifier. The interested reader is referred to a 1998 Health and Human Services white paper, developed prior to a congressional ban on government funded UPI discussion, which discusses relevant legislation, privacy and confidentiality concerns, as well as strengths and weaknesses of several proposed implementations of a national UPI. The following is a discussion centered on commonly broached UPIs—SSN, biometric identifiers, and a voluntary universal health care identifier.

Cont. Social Security Number The SSN has been advanced as a candidate for a UPI in the United States because it is theoretically unique, ubiquitous, unchanging, most adults can recite it from memory, and would not require additional infrastructure to implement (ie, inexpensive and uncomplicated). However, in reality, the SSN is sometimes shared by multiple individuals, not all people are eligible for an SSN, in rare circumstances an individual may possess more than one SSN, SSNs are not universally available at birth, and there is no legal protection for maintaining SSN confidentiality in nongovernment organizations. Using the SSN also comes with controversy, largely as a result of its universality. At its inception, the SSN was for use only within the context of the Social Security program and intended to identify an account, not a person. Today, the SSN has become tightly linked to an individual’s credit score, among other things, and is now largely viewed as a nonconfidential identifier.

Biometric Identifiers Cont. Biometric identifiers such as fingerprints, iris scans, voice recognition, and facial shapes offer unique, ubiquitous, and relatively unchanging identifiers. In developed nations, implementation of biometrics has been scarce, mainly because of concerns with privacy and the potential for law enforcement to use these data. However, underdeveloped nations often lack universal coverage by civil registration systems leading to an identification problem that reaches far beyond health care. Recent technological advances are allowing cheaper, more accurate identification using biometric indicators such as fingerprints and iris scans. In a report for the Center for Global Development, Gelb and Clark found that 160 countries have deployed biometrics to address the identify gap covering over 1 billion people. While highly discriminatory, biometric identifiers do not eliminate the need for sophisticated matching algorithms to uniquely identify an individual. Measurements of a person’s fingerprint or iris will possess variability within persons, due to changes in age, environment, disease, stress, and occupational factors, as well as variability due to hardware (eg, sensor calibration and age of the device). In the case of fingerprints, any single individual can produce several distinct images depending on the angle of depression, pressure, presence of dirt, moisture, and sensor characteristics.

Cont. Voluntary Universal Healthcare Identifier (VUHID) An example of VUHID was deployed by Global Patient Identifiers, Inc. (GPII) and attempts to completely eliminate patient matching errors by augmenting existing probabilistic matching algorithms with a VUHID. The patient may request one open voluntary identifier (OVID), which as the name suggests shares all information with all providers, and multiple private voluntary identifiers (PVID) that will only disclose information to patient-selected providers. A key design element for the VUHID proposed by GPII is that once a patient requests to participate through their provider, they are assigned a unique identifier that, unlike the SSN, is used only to identify them in the health care setting. The VUHID then routes the unique identifier back through the HIE CR to be associated with the patient’s records. The unique identifier (implemented by barcode, magnetic strip, smart card, etc. ) is given to the patient and presented when visiting a provider. Drawbacks of the proposed VUHID include the complexity introduced by the PVID, which assumes that patients will understand when it is clinically important to share information from one provider with another, and concerns that the failure to share all records may impede hospitals from producing complete billing records.

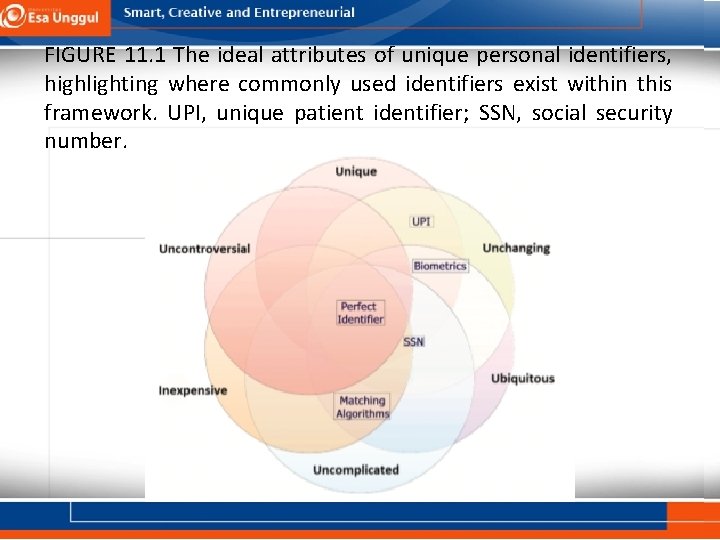

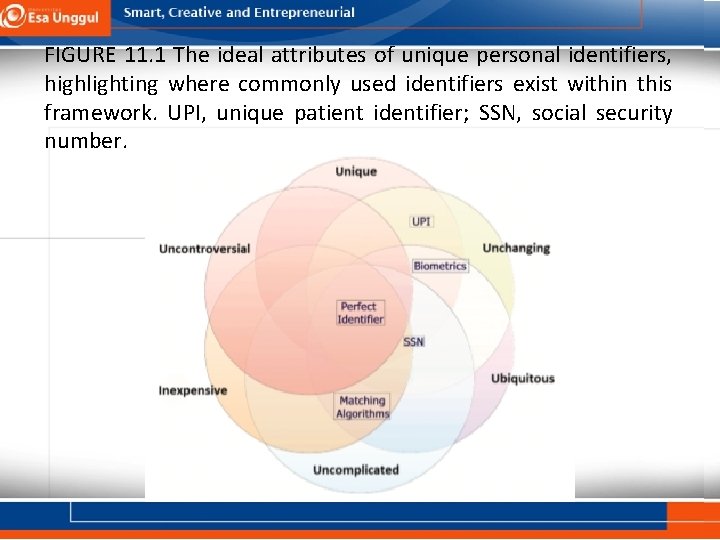

Cont. International Unique Patient Identifiers UPIs have been developed and implemented in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Details on the purpose, formats, validation methods, technical architectures, and lessons learned from UPI implementations in England, Newfoundland Labrador, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany may be found in a review from 2010 by the Health Information and Quality Authority. Specific use cases for implementing a UPI in Denmark, Botswana, Kenya, Brazil, Malawi, Ukraine, Thailand, and Zambia are discussed in a UNAIDS white paper addressing developing and using individual identifiers for health services including HIV. Although no single identifier currently exists with each of the ideal attributes, Figure 11. 1 depicts the degree to which the examples discussed meet the expectations of an ideal identifier. As will be discussed, a key strength of the CR is the ability to utilize multiple identifiers through matching algorithms to positively identify a patient. That is, the CR does not rely on the necessity to produce an ideal UPI; however, when a UPI is available, matching efficiency is improved. UPIs hold promise for simplifying patient identification, but even in the case a UPI is in use, there is a need to match patients using other attributes, such as demographics, when a UPI is unavailable at the time of service (eg, forgot card or emergency situations). Similarly, if a temporary identification must be issued, the central authority will need to utilize other identifiers, such as demographics, to link a patient’s UPI to the temporary ID to prevent record fragmentation. In general, the implementation of a UPI will improve the accuracy of matching procedures but will not replace the need for demographic attributes.

FIGURE 11. 1 The ideal attributes of unique personal identifiers, highlighting where commonly used identifiers exist within this framework. UPI, unique patient identifier; SSN, social security number.

THE ENTERPRISE MASTER PATIENT INDEX Each health care organization’s e. MPI associates its own unique identifier with patient data; thus, a single patient may have several “unique” e. MPI identifiers, one within each organization where care occurred. The lack of a shared identifier across organizations makes integration of patient data difficult. So if Bob visits an ED outside his usual integrated health care system, data about the visit would not be integrated into the EHR system record utilized by his primary care physician and, unless Bob discloses this information, his primary care physician may never be aware of the incident. The unique identifier problem has an intuitive solution that creates a unique identifier to span all health care organizations.

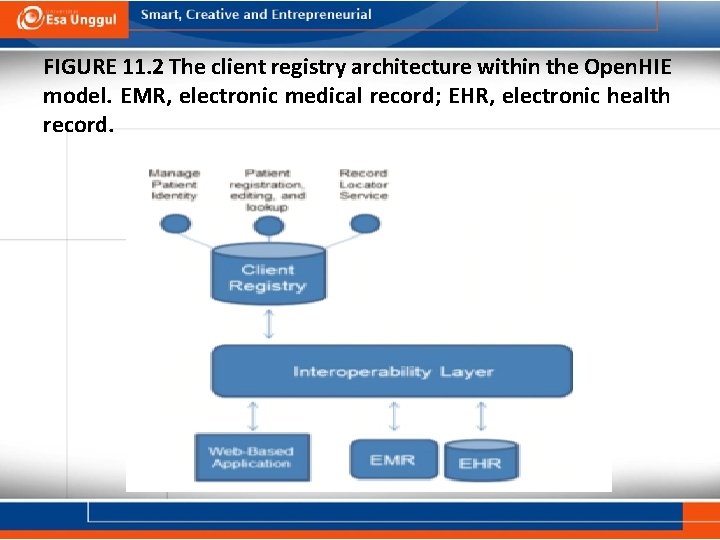

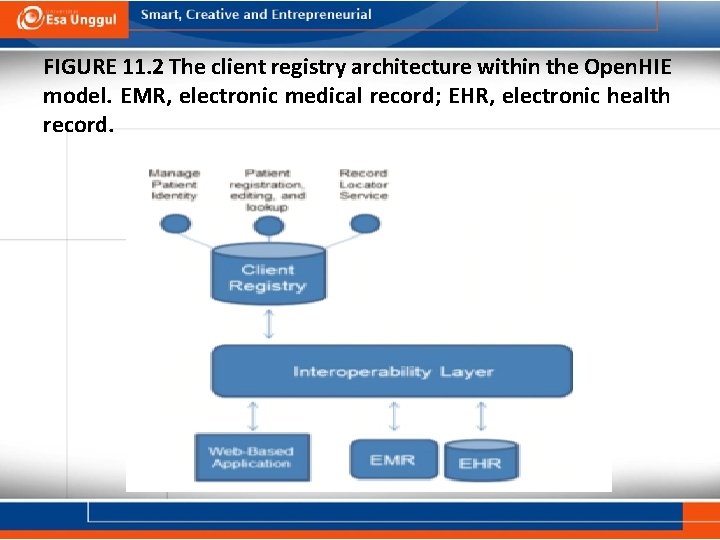

THE CLIENT REGISTRY The e. MPI uniquely identified and linked each of Bob’s specialty care visits because they were within the same network or enterprise, but data from an ED visit outside Bob’s usual integrated health care system would remain in a silo. A natural, logical solution might be the use of an UPI that could span all of Bob’s health care services and allow for positive identification and linkage of Bob’s ED visit to his other health care data. However, no single UPI is currently available that would facilitate linking all of Bob’s records. Thus, in order to link data across the health system, we must rely upon an assemblage of existing identifiers. A CR operates by adjudicating the assemblage of demographic attributes and other personal identifiers from each data supplier (eg, hospitals, clinics, etc. ) to create a single record for each patient within the HIE. Figure 11. 2 demonstrates how the CR fits into the scheme of the HIE model. Organizational EHR systems and point-of-care applications interact with the CR through the interoperability layer allowing users to retrieve, add, and edit patient records. Once positive identification is made, the CR associates each patient’s records with a unique number called the master patient index (MPI). Although similar in concept to the unique number assigned by an e. MPI, the MPI—in the context of the CR —acts as the controller for all other local identifiers that may be associated with the patient, including one or more MRNs assigned by individual facilities and

FIGURE 11. 2 The client registry architecture within the Open. HIE model. EMR, electronic medical record; EHR, electronic health record.

SUMMARY Health care data are generated from numerous clinical sites, often by different EHR systems. Each organization has its own method of uniquely identifying patients, but these identifiers are incapable of identifying patient records from outside organizations. Currently, no single unique patient identifier is capable of spanning the entire health care environment, and record linkage must rely upon multiple patient attributes and identifiers. The CR handles inconsistent completeness and quality of identifying data by standardizing incoming data and employing statistical matching algorithms to link data from separate organizations for the same patient. Once identified, a single, unique identifier (the MPI) is associated with the patient, allowing HIE networks to create and maintain patient-centric records and services.

Kelemahan asesmen alternatif

Kelemahan asesmen alternatif Implementasi css menggunakan tag merupakan implementasi

Implementasi css menggunakan tag merupakan implementasi Asesmen wawancara adalah

Asesmen wawancara adalah Perbedaan aum umum dan ptsdl

Perbedaan aum umum dan ptsdl Implementasi perencanaan

Implementasi perencanaan Penaksiran resiko dan desain pengujian

Penaksiran resiko dan desain pengujian Apa itu physical security

Apa itu physical security Penaksiran resiko dan desain pengujian

Penaksiran resiko dan desain pengujian Pusat asesmen dan pembelajaran

Pusat asesmen dan pembelajaran Asesmen komunitas adalah

Asesmen komunitas adalah Tugas proktor dan teknisi asesmen nasional

Tugas proktor dan teknisi asesmen nasional Contoh asesmen formatif dan sumatif

Contoh asesmen formatif dan sumatif Contoh asesmen kinerja rubrik dan portofolio

Contoh asesmen kinerja rubrik dan portofolio Mata kuliah testing dan implementasi sistem

Mata kuliah testing dan implementasi sistem Kerangka pemikiran dalam penelitian

Kerangka pemikiran dalam penelitian Gambar model implementasi van meter dan van horn

Gambar model implementasi van meter dan van horn Testing dan implementasi sistem

Testing dan implementasi sistem Implementasi iman dan taqwa dalam kehidupan sehari-hari

Implementasi iman dan taqwa dalam kehidupan sehari-hari Implementasi taqwa dalam kehidupan sehari-hari

Implementasi taqwa dalam kehidupan sehari-hari Sikda generik lamongan

Sikda generik lamongan Testing dan implementasi sistem

Testing dan implementasi sistem