Oncology Nursing Society Putting Evidence into Practice PEP

- Slides: 26

Oncology Nursing Society Putting Evidence into Practice (PEP) Assessment and Measurement of Medication Adherence: Oral Anti-Cancer Agents Sandra L. Spoelstra, Ph. D, RN Oncology Nursing Society Congress April 20, 2015 Orlando, FL

Objectives I. To define medication adherence. § In relation to oral anti-cancer agents (OAC). II. To describe the methods available to assess and measure medication adherence.

The Problem • Despite efforts to encourage adherence to oral agents for cancer (OAC), rates are sub-optimal. (Bassan, 2014) • OAC adherence is a problem which may impact treatment success. (Puts, 2013) • There is need to assess and measure OAC adherence.

Definition Adherence: “The degree or extent of conformity to the recommendations about day-to-day treatment by the provider with respect to the timing, dosage, and frequency for the duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy. ” (Cramer, 2007) – Timing (e. g. time of day – 9: 00 AM) – Dosage (e. g. 200 mg) – Frequency (e. g. daily, BID, TID) • Examines: – Taking < than prescribed – Taking > than prescribed – Doses taken too close together

Therapeutic Dosing • FDA Guidelines OACs (U. S. Food & Drug Administration, 2014) • Inadequate dosing can occur: – Due to toxicities from side effects of treatment – Dose reductions or stoppages – Problems with obtaining the medication (Bozic, 2013; Gebbia, 2012; Puts, 2013). • Tumor response or survival dosing is not known: – Whether 80% of the dosage is adequate – Or if 90% may be effective (Alberto, 1994)

Relative Dose Intensity (RDI) • Ratio of dose taken over time compared to the ordered dose. (Amgen, 2008) • Maintaining RDI reduces survival of resistant clones, increases percent of cells killed per dose, and decreases intervals between treatment cycles. • Results in greater treatment efficacy. • Most oncologists prefer 100% OAC adherence to assure RDI.

Complexities of OACs • Simple: – Once daily dosing • Complex: – More than daily dosing – On-and-off cycling – Two or more drugs (Spoelstra et al. , 2013)

The Process • PEP Team Project: Literature search to identify ways to assess and measure medication adherence – – – Oncology Nursing Society: Margaret Irwin Ph. D, RN, MN Cynthia Rittenberg, MN RN FAAN, AOCN Lee Ann Johnson, RN, PHDc Carol Blecher, MS, APNC, OACN, CBPN-C, CBCN Peggy Burhenn, MS, CNS, AOCNS Larissa Day, MSN, RN, CONC Diana Mc. Mahon, MSN, RN, OCN; AOCN Theresa Rudnitzki, MS, RN, ACNS-BC, AOCNS Josephine Smudde, MS, RN, BC, OCN Holly Sansoucie, RN, MSN, DNP, AOCN, CBCN Sandra Spoelstra, Ph. D, RN Janelle Tipton, MSN, RN, AOCN

Results • Measures: – 3 -Direct measures were identified – 4 -Indirect measures were identified • 7 -Tools were identified in the literature – Tools were divided into two categories: 1. Ability to assess risk of non-adherence 2. Ability to measure adherence rates

Direct & Indirect MEASURES

Direct Measures • Drug assays of serum or urine – not available for OACs • Drug markers – do not exist for OACs • Direct observation of medication ingestion 6 • COSTLY AND IMPRACTICAL

Indirect Measures • Self-report – Overestimates adherence due to questions not being specific, desire to please providers, and decreased cognitive ability to recall. Unreliable • Pill counts – Overestimate. Time consuming • Electronic monitoring systems – No way to know if ingested. Expensive and unrealistic for clinical setting • Pharmacy records and claims – Proportion of days covered (PDC): summing # days in a time period “covered” by the medication divided by # days in the period. Unrealistic for clinical setting as doctors do not have this access

To Assess TOOLS

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) • Evaluates past medication use patterns • Four “yes” or “no” questions (Moriskey, 1986) – Scored with a 1 for “yes” and a 0 for “no”; summed – Score of 0 is high adherence, 1 -2 is medium, and 3 -4 is low • Psychometrics: – Predictive validity 0. 75 adherence; 0. 47 nonadherence – Sensitivity 0. 81; Specificity 0. 44 • Floor/ceiling effects likely, due to the nature of questions – Makes tool unreliable to measure adherence • May be effective at predicting risk of nonadherence

Adherence Estimator • • Three-item tool (Mc. Horney, 2009) Screens likelihood of nonadherence Placed in categories: low, medium, high scores Psychometrics: – Sensitivity high: Cronbachs alpha at 0. 88 – Specificity acceptable at 59% • Does not assess adherence rate • May accurately predict risk of nonadherence.

Beliefs about Medication Questionnaire (BMQ) • 17 -item two-section, self-report tool (Horne, 1999) 1. BMQ-Specific assesses medications prescribed for personal use • Two 5 -item factors assess beliefs about necessity of medication and concerns based on beliefs about the danger of dependence and long-term toxicity and the disruptive effects 2. BMQ-General assesses beliefs about medicines in general. • Two 4 -item factors assessing beliefs about medicine overuse and safety • Score: – – 1 -point strongly disagree; 2 -disagree, 3 -uncertain, 4 -agree, 5 -strongly agree Higher scores (range 10— 50) indicate better adherence Cronbachs Alpha each sub-scales >0. 80 Sensitivity and specificity lacking to measure adherence • Can possibly predict nonadherence • Tedious process for clinical setting.

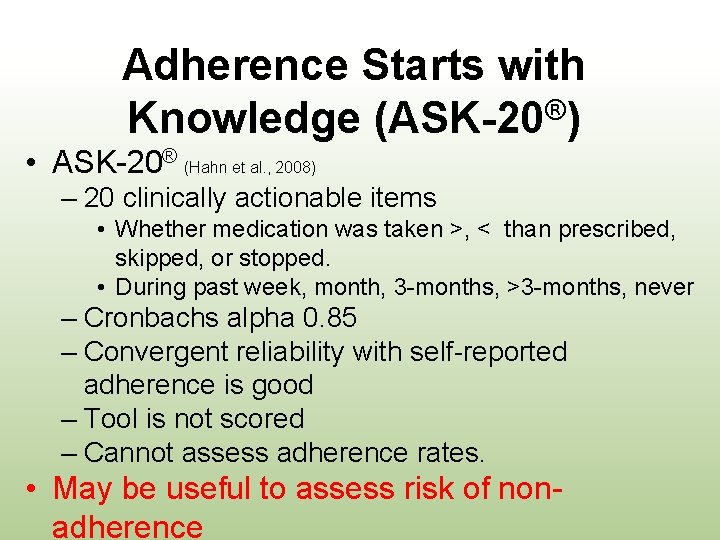

Adherence Starts with ® Knowledge (ASK-20 ) • ASK-20® (Hahn et al. , 2008) – 20 clinically actionable items • Whether medication was taken >, < than prescribed, skipped, or stopped. • During past week, month, 3 -months, >3 -months, never – Cronbachs alpha 0. 85 – Convergent reliability with self-reported adherence is good – Tool is not scored – Cannot assess adherence rates. • May be useful to assess risk of nonadherence

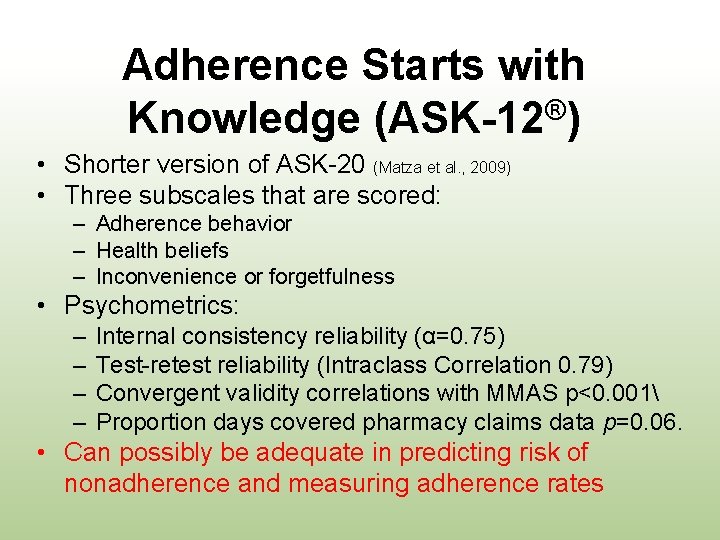

Adherence Starts with ® Knowledge (ASK-12 ) • Shorter version of ASK-20 (Matza et al. , 2009) • Three subscales that are scored: – Adherence behavior – Health beliefs – Inconvenience or forgetfulness • Psychometrics: – – Internal consistency reliability (α=0. 75) Test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation 0. 79) Convergent validity correlations with MMAS p<0. 001 Proportion days covered pharmacy claims data p=0. 06. • Can possibly be adequate in predicting risk of nonadherence and measuring adherence rates

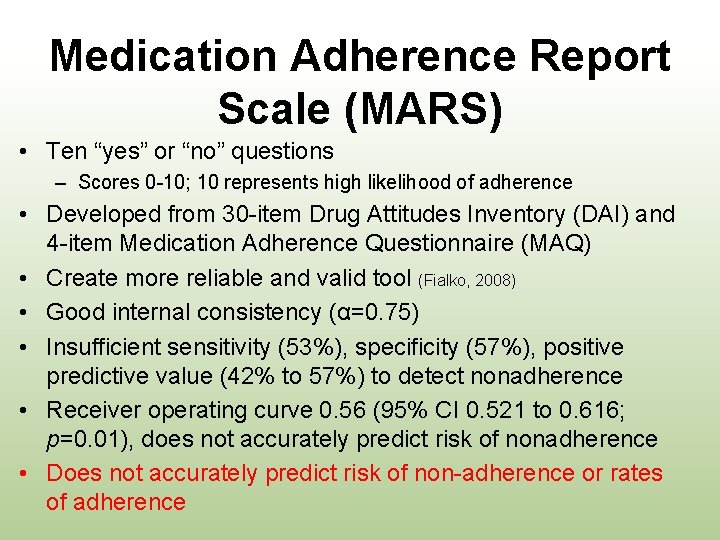

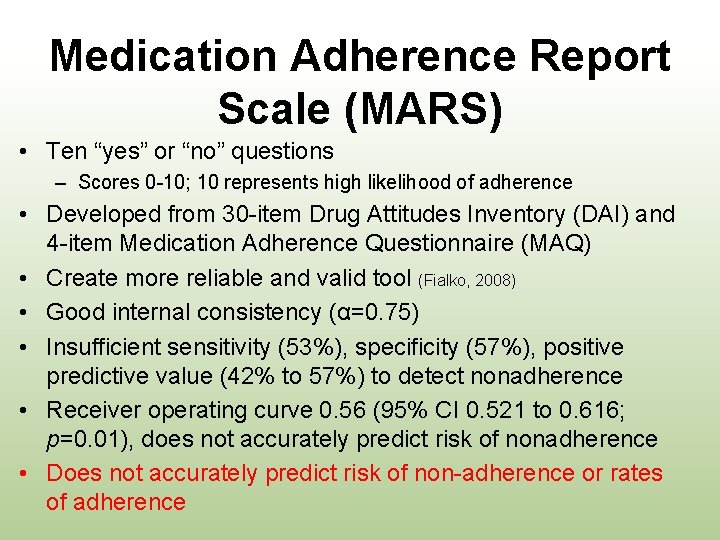

Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) • Ten “yes” or “no” questions – Scores 0 -10; 10 represents high likelihood of adherence • Developed from 30 -item Drug Attitudes Inventory (DAI) and 4 -item Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ) • Create more reliable and valid tool (Fialko, 2008) • Good internal consistency (α=0. 75) • Insufficient sensitivity (53%), specificity (57%), positive predictive value (42% to 57%) to detect nonadherence • Receiver operating curve 0. 56 (95% CI 0. 521 to 0. 616; p=0. 01), does not accurately predict risk of nonadherence • Does not accurately predict risk of non-adherence or rates of adherence

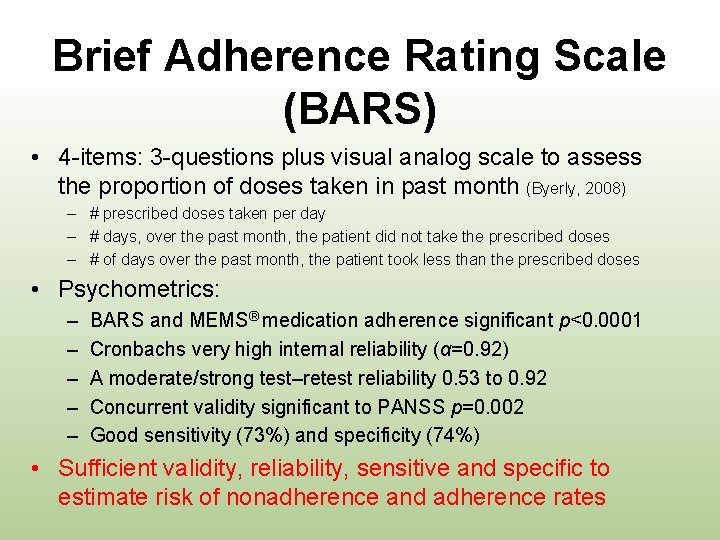

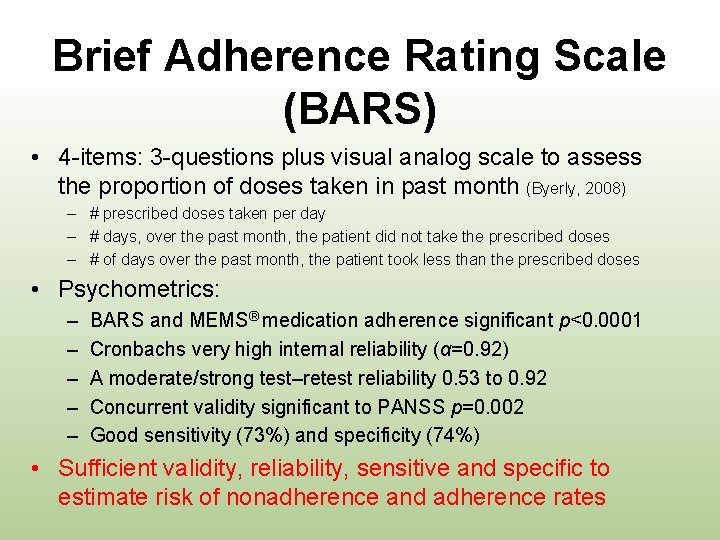

Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) • 4 -items: 3 -questions plus visual analog scale to assess the proportion of doses taken in past month (Byerly, 2008) – # prescribed doses taken per day – # days, over the past month, the patient did not take the prescribed doses – # of days over the past month, the patient took less than the prescribed doses • Psychometrics: – – – BARS and MEMS® medication adherence significant p<0. 0001 Cronbachs very high internal reliability (α=0. 92) A moderate/strong test–retest reliability 0. 53 to 0. 92 Concurrent validity significant to PANSS p=0. 002 Good sensitivity (73%) and specificity (74%) • Sufficient validity, reliability, sensitive and specific to estimate risk of nonadherence and adherence rates

Assessing and Measuring Medication Adherence STATE OF THE SCIENCE

• Ability to assess and/or measure OAC medication adherence is poor. – Most measures are indirect, and include a form of self-report that cannot truly capture if the medication was taken. – A few tools are able to assess risk of nonadherence – Lack specificity to determine adherence – Nor can both OAC underadherence and overadherence can be examined.

Tools that may be useful for measuring adherence rates: • ASK-12® • BARS Tools that may assess risk of non-adherence: • • Adherence Estimator Morisky ASK-12® BARS

Implications for Research • Need for practice-based tools • Technology – Including timing, dose, frequency, & duration

Implications for Nursing Practice • Adherence needs to be defined, assessed, and documented.

References Alberto, P. (1994). Dose intensity in cancer chemotherapy: Definition, average relative dose intensity and effective dose intensity. Bulletin du Cancer, 82(Suppl. 1), 3 s– 8 s. Retrieved from http: //www. jle. com/en/revues/bdc/revue. phtml Amgen. (2008). Increasing awareness of relative dose intensity in an evidence-based practice. Retrievedfrom http: //www. onsedge. com/pdf/amgen. EBP. pdf Bassan, F. , Peter, F. , Houbre, B. , Brennstuhl, M. J. , Costantini, M. , Speyer, E. , & Tarquinio, C. (2014). Adherence to oral antineoplastic agents by cancer patients: Definition and literature review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 23, 22– 35. Bozic, I. , Reiter, J. G. , Allen, B. , Antal, T. , Chatterjee, K. , Shah, P. , . . . Le, D. T. (2013). Evolutionary dynamics of cancer in response to targeted combination therapy. e. Life, 2, 1– 15. Byerly, M. J. , Nakonezny, P. A. , & Rush, A. J. (2008). The Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) validated against electronic monitoring in assessing the antipsychotic medication adherence of outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophrenia Research, 100(1– 3), 60– 69. Cramer, J. A. , Roy, A. , Burrell, A. , Fairchild, C. J. , Fuldeore, M. J. , Ollendorf, D. A. , & Wong, P. K. (2008). Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value in Health, 11(1), 44– 47 Fialko, L. , Garety, P. A. , Kuipers, E. , Dunn, G. , Bebbington, P. E. , Fowler, D. , & Freeman, D. (2008). A large-scale validation study of the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS). Schizophrenia Research, 100(1– 3), 53– 59. Gebbia, V. , Bellavia, G. , Ferraù, F. , & Valerio, M. R. (2012). Adherence, compliance and persistence to oral antineoplastic therapy: A review focused on chemotherapeutic and biologic agents. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 11(S 1), S 49–S 59. Hahn, S. R. , Park, J. , Skinner, E. P. , Yu-Isenberg, K. S. , Weaver, M. B. , Crawford, B. , & Flowers, P. W. (2008). Development of the ASK-20 adherence barrier survey. Current Medical Research Opinions, 24, 2127– 2138. Horne, R. , Weinman, J. , & Hankins, M. (1999). The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: The development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychology and Health, 14, 1– 24. Matza, L. S. , Park, J. , Coyne, K. S. , Skinner, E. P. , Malley, K. G. , & Wolever, R. Q. (2009). Derivation and validation of the ASK-12 adherence barrier survey. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 43, 1614– 1630. Mc. Horney, 2009. The Adherence Estimator: a brief, proximal screener for patient propensity to adhere to prescription medications for chronic disease. Current Medical Research & Opinion 2009 25: 1 , 215 -238 Morisky, D. E. , Green, L. W. , & Levine, D. M. (1986). Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Medical Care, 24, 67– 74. Puts, M. T. , Tu, H. A. , Tourangeau, A. , Howell, D. , Fitch, M. , Springall, E. , & Alibhai, S. M. (2013). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of Oncology, 25(3), 564 -577. Spoelstra, S. L. , Given, B. A. , Given, C. W. , Grant, M. , Sikorskii, A. , You, M. , & Decker, V. (2013). An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents: An exploratory study. Cancer Nursing, 36, 18– 28.

Putting evidence into practice

Putting evidence into practice Putting service pricing into practice

Putting service pricing into practice Putting it into practice

Putting it into practice Putting prevention into practice

Putting prevention into practice Putting principles into practice

Putting principles into practice Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system

Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system

Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system Practice putting it all together part 1 fill in the blank

Practice putting it all together part 1 fill in the blank Achog

Achog Connective tissue oncology society

Connective tissue oncology society 2017 asco oncology practice conference

2017 asco oncology practice conference Testicular cancer nursing diagnosis

Testicular cancer nursing diagnosis Primary evidence vs secondary evidence

Primary evidence vs secondary evidence Primary evidence vs secondary evidence

Primary evidence vs secondary evidence Secondary sources

Secondary sources Primary evidence vs secondary evidence

Primary evidence vs secondary evidence Jobs vancouver

Jobs vancouver Fiber evidence can have probative value

Fiber evidence can have probative value Class evidence vs individual evidence

Class evidence vs individual evidence Individual evidence can have probative value

Individual evidence can have probative value A pair of latex gloves was found at a crime scene

A pair of latex gloves was found at a crime scene The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence meaning

The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence meaning Gertler econ

Gertler econ Putting-out system

Putting-out system What does nasreen say about ice cream with chocolate

What does nasreen say about ice cream with chocolate Putting-out system

Putting-out system Proletarianization ap euro

Proletarianization ap euro