Normative Approaches to Values in Science Kristina Rolin

- Slides: 27

Normative Approaches to Values in Science Kristina Rolin IAPH 2010: Feminism, Science, and Values June 27 th, 2010

The traditional ideal of value-free science • Social and moral values are not allowed to play any role in the reasoning and decision-making that scientists are engaged in when they decide to accept something as scientific knowledge, either individually or collectively. • Whereas feminist philosophers of science seem to be unanimous about the need to replace the traditional ideal of value-free science, their views diverge on the question of what the successor to the traditional ideal should be.

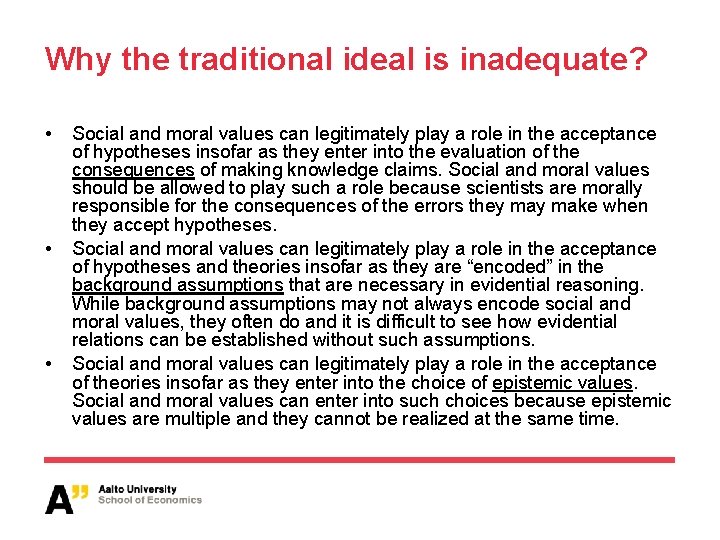

Why the traditional ideal is inadequate? • • • Social and moral values can legitimately play a role in the acceptance of hypotheses insofar as they enter into the evaluation of the consequences of making knowledge claims. Social and moral values should be allowed to play such a role because scientists are morally responsible for the consequences of the errors they make when they accept hypotheses. Social and moral values can legitimately play a role in the acceptance of hypotheses and theories insofar as they are “encoded” in the background assumptions that are necessary in evidential reasoning. While background assumptions may not always encode social and moral values, they often do and it is difficult to see how evidential relations can be established without such assumptions. Social and moral values can legitimately play a role in the acceptance of theories insofar as they enter into the choice of epistemic values. Social and moral values can enter into such choices because epistemic values are multiple and they cannot be realized at the same time.

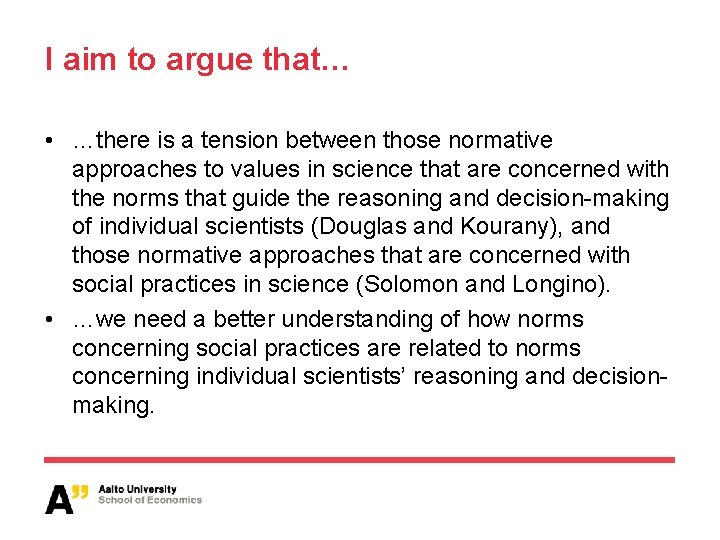

I aim to argue that… • …there is a tension between those normative approaches to values in science that are concerned with the norms that guide the reasoning and decision-making of individual scientists (Douglas and Kourany), and those normative approaches that are concerned with social practices in science (Solomon and Longino). • …we need a better understanding of how norms concerning social practices are related to norms concerning individual scientists’ reasoning and decisionmaking.

Miriam Solomon’s social empiricism

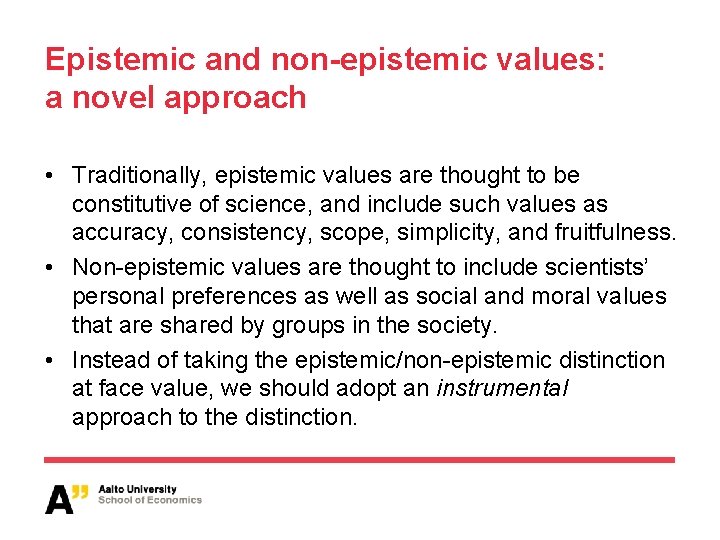

Epistemic and non-epistemic values: a novel approach • Traditionally, epistemic values are thought to be constitutive of science, and include such values as accuracy, consistency, scope, simplicity, and fruitfulness. • Non-epistemic values are thought to include scientists’ personal preferences as well as social and moral values that are shared by groups in the society. • Instead of taking the epistemic/non-epistemic distinction at face value, we should adopt an instrumental approach to the distinction.

Non-epistemic values: a re-evaluation • Any scientific practice that leads to empirical success or truth deserves to be called scientifically rational. • Given an instrumental perspective, even those values that have traditionally been conceived as non-epistemic can play a rational role in science. They can play a rational role by distributing research efforts in the community among those theories that have some empirical successes. • It is possible to make a distinction between two types of “decision vectors, ” empirical and non-empirical, on a priori grounds.

Solomon’s normative theory of values in science: individual level • A normative theory of values in science should not discourage the influence of non-empirical decision vectors at the individual level in determining a scientist’s choice of one theory over another. • For an individual scientist, social empiricism gives only one guideline. A scientist should work with empirically successful theories. • We should accept such a minimally constraining policy with respect to individual scientists’ reasoning and decisionmaking because non-empirical decision vectors can play a rational role in science.

Solomon’s normative theory of values in science: community level • A community of scientists should distribute research efforts when different theories have different empirical successes and none of theories has all available empirical successes in a domain of inquiry. • A rational distribution of research effort requires two things: (1) empirical decision vectors be equitably distributed in proportion to the empirical successes of the various theories under consideration, and (2) nonempirical decision vectors be equally distributed among those theories that have some empirical successes.

Criticism #1 • Even if it is the case that non-empirical decision vectors can play a rational role in science, it does not follow that a normative theory should not set any constraints on non-empirical decision vectors in individual scientists’ reasoning and decision-making. • In order for Solomon’s argument to be valid, she would have to make the stronger claim that non-empirical decision vectors always function in a rational way in scientific inquiry. This claim, however, is false. • Whether non-empirical decision vectors function in a rational way in science is to be decided on a case by case basis.

Criticism #2 • It is not coherent to suggest, as Solomon does, that epistemic responsibility should be located in scientific communities and not in individual scientists. • An individual scientist is epistemically responsible in making a claim when she provides sufficient evidence in its support - or at least adopts it with a “defense commitment. ” • A group is epistemically responsible in its view when at least one member of the group provides evidence for the group’s view or carries out the duties involved in a defense commitment. • Therefore, it is impossible for a group’s epistemic responsibility to emerge from a group where all individuals are epistemically irresponsible.

Heather Douglas’s conception of scientific integrity

Scientific integrity • Scientific integrity consists in keeping social and moral values to their proper roles in scientific reasoning, not in keeping them out of scientific reasoning. • Values play a direct role when they act as reasons to accept a hypothesis or a theory and an indirect role when they act as reasons to accept a certain level of uncertainty. • Social and moral values are not allowed to play a direct role in scientific reasoning but they can legitimately play an indirect role.

Arguments • A direct role is not acceptable because it would undermine the value of science itself, its basic integrity and authority. • An indirect role is acceptable because scientists are morally responsible for the potential harm caused by their making overly strong knowledge claims and downplaying the risk of error. Scientists should make value judgments concerning the acceptable level of uncertainty, and these judgments require social and moral values. • Value judgments should be made as explicit as possible because the public has a right to understand the social and moral values behind scientists’ assessment of the acceptable level of uncertainty.

Criticism • Social and moral values can play other roles in scientific reasoning besides direct and indirect roles. • Social and moral values can be “encoded” in background assumptions that are necessary to establish the relevance of evidence for a hypothesis or a theory (Longino 1990). • Insofar as social and moral values enter into scientific reasoning via background assumptions, their role is not direct because they do not act as evidence in scientific reasoning. Also, their role is not indirect because they do not concern the question of how much evidence is sufficient to render the risk of error acceptable. • Douglas’s normative theory of values in science does not provide guidance for such a situation.

Helen Longino’s social account of objectivity

Individual level • Social and moral values can legitimately play a role in individual scientists’ choice of background assumptions. • Objectivity cannot be realized in an individual scientist’s reasoning and decision-making because both the status of observation reports as empirical evidence, as well as the plausibility of evidential reasoning is dependent on a context of background assumptions which may include assumptions encoding moral and social values. • Individual scientists are not always capable of identifying such assumptions on their own.

Community level • A social account of objectivity is needed because “there are no formal rules, guidelines, or processes that can guarantee that social values will not permeate evidential relations” (2002, 50). • A social account of objectivity is needed to make sure that background assumptions as well as the social and moral values that have motivated their choice can be criticized.

Norms for social practice There at least four norms that are aptly included in the social account of objectivity because they facilitate “transformative criticism. ” (1) Public criticism: There must be publicly recognized forums for the criticism of evidence, of methods, and of assumptions and reasoning. (2) Uptake of criticism: There must be uptake of criticism. (3) Shared standards: There must be publicly recognized standards by which theories, hypotheses, and observational practices are evaluated and by appeal to which criticism is made relevant to the goals of the inquiring community. (4) Tempered equality of intellectual authority: Communities must be characterized by the equality of intellectual authority.

Longino’s approach vs. other approaches • Longino’s approach differs from Douglas’s approach in that it does not assume that individual scientists are capable of realizing the ideal of objectivity on their own. • Longino’s approach differs from Solomon’s approach in that it does not assume that scientific communities are capable of realizing the ideal of objectivity without assigning epistemic rights and obligations to individual scientists. The four norms imply epistemic rights and obligations for individual scientists.

Kourany’s criticism • Longino’s ideal of “social value management” is not sufficiently normative to count as a feminist philosophy of science. • It is not sufficient to recommend that scientific communities be inclusive of feminist scientists. • Feminist philosophy of science should recommend the ideal of “socially responsible science” that directs all scientists to include only specific social values in science.

Janet Kourany’s ideal of socially responsible science

Socially responsible science “Rather than strive to exclude all social values from science, as the ideal of value-free science directs scientists to do, or to include all social values in science but subject them all to criticism, as Longino’s social value management ideal of science directs scientists to do, the ideal of socially responsible science directs scientists to include only specific social values in science, namely the ones that meet the needs of society” (2008, 95; italics mine).

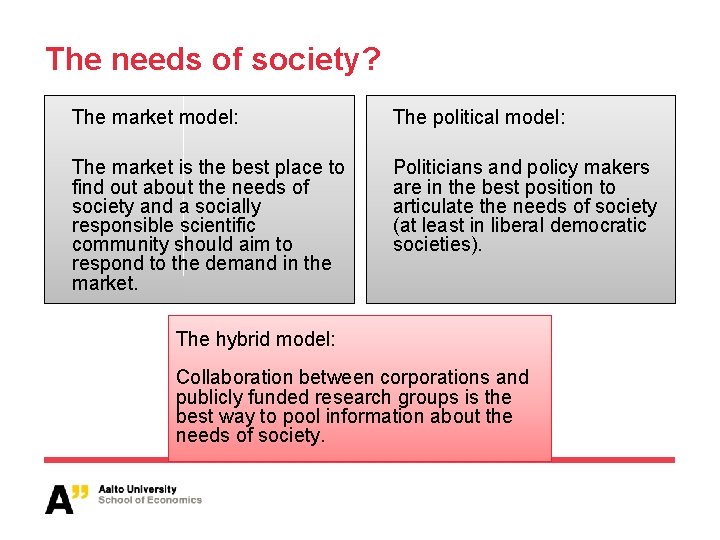

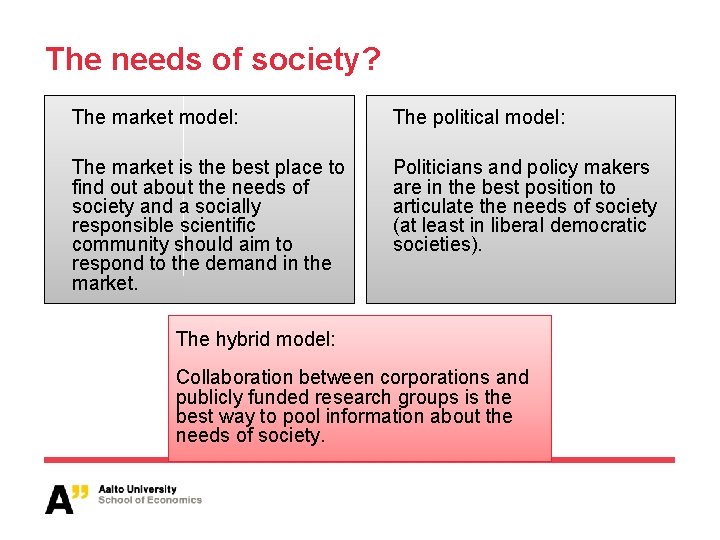

The needs of society? The market model: The political model: The market is the best place to find out about the needs of society and a socially responsible scientific community should aim to respond to the demand in the market. Politicians and policy makers are in the best position to articulate the needs of society (at least in liberal democratic societies). The hybrid model: Collaboration between corporations and publicly funded research groups is the best way to pool information about the needs of society.

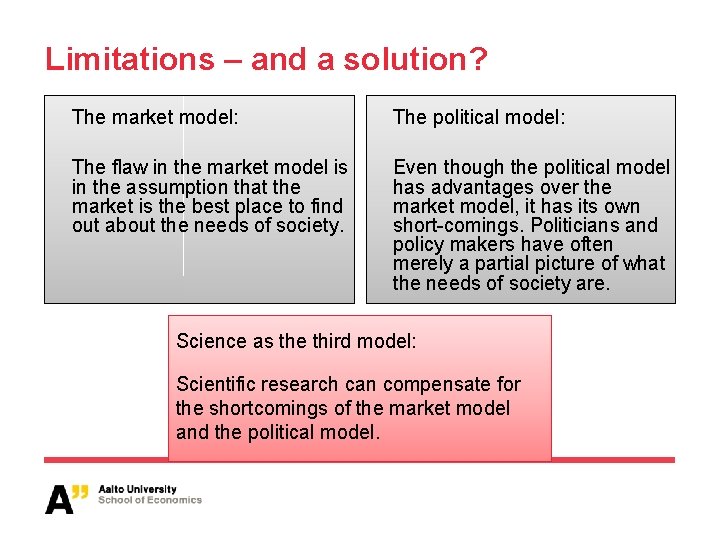

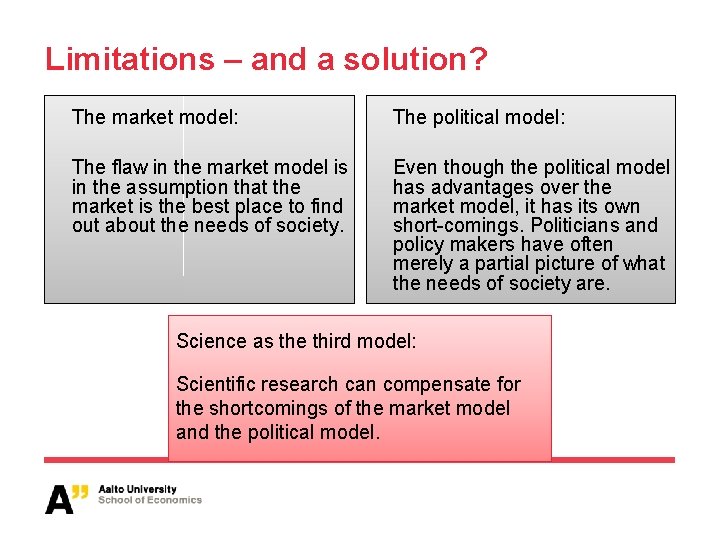

Limitations – and a solution? The market model: The political model: The flaw in the market model is in the assumption that the market is the best place to find out about the needs of society. Even though the political model has advantages over the market model, it has its own short-comings. Politicians and policy makers have often merely a partial picture of what the needs of society are. Science as the third model: Scientific research can compensate for the shortcomings of the market model and the political model.

Criticism • Scientists should be given the opportunity and resources to engage themselves in an on-going debate about the needs of society because both the market model and the political model (and the hybrid model) have their shortcomings. • Scientists should not be expected to take at face value the “needs” that are expressed in the market or articulated by politicians, policy makers, and non-governmental organizations. • Longino’s social value management ideal of science is capable of meeting the needs of society better than Kourany ideal because it does not accept different articulations of needs dogmatically; instead, they are subjected to critical scrutiny.

Conclusions While I agree with Solomon that social and moral values can play a positive role in science by generating a distribution of research efforts, I do not believe that a normative theory of values in science should refrain from assigning epistemic responsibilities to individual scientists. While I agree with Douglas that a normative theory of values in science should include rules for the reasoning and decisionmaking of individual scientists, I do not believe that such rules are sufficient. I have raised concerns about Kourany’s attempt to defend certain values for all individual scientists.

Kristina rolin

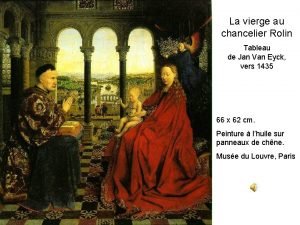

Kristina rolin La vierge au chancelier rolin de jan van eyck

La vierge au chancelier rolin de jan van eyck La vierge du chancelier rolin analyse

La vierge du chancelier rolin analyse Miguel angel obras

Miguel angel obras Jan van eyck (1390-1441)

Jan van eyck (1390-1441) Physical mobility scale score interpretation

Physical mobility scale score interpretation My subject is

My subject is Western values vs eastern values

Western values vs eastern values Machavillian

Machavillian An individual's enduring tendency to feel

An individual's enduring tendency to feel A bit can have two possible values. what value are those

A bit can have two possible values. what value are those Human values definition

Human values definition Kristina elfgren

Kristina elfgren Podatak informacija znanje

Podatak informacija znanje Kristina yondt

Kristina yondt Kristina vukaj

Kristina vukaj Kristina urbanc

Kristina urbanc Kristina pai

Kristina pai Kristina soon

Kristina soon Kristina kull

Kristina kull Zahrtmann sokrates og alkibiades

Zahrtmann sokrates og alkibiades Klart under genomsnittet

Klart under genomsnittet Kristina grange

Kristina grange Mikrofibrill

Mikrofibrill Kristina jung

Kristina jung Kristina oligsč

Kristina oligsč Kristina yondt

Kristina yondt Kristina lukačić

Kristina lukačić