Merger Antitrust Review Formulas and Other Reference Materials

- Slides: 39

Merger Antitrust Review: Formulas and Other Reference Materials Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins Note: I use a program called Math. Type to embed the equations. As a result, they may not copy to a document that does not have Math. Type as an add-in. October 28, 2020

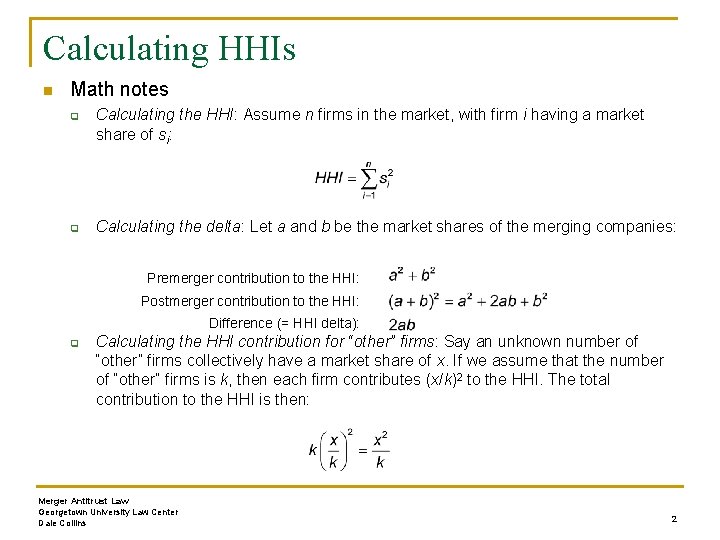

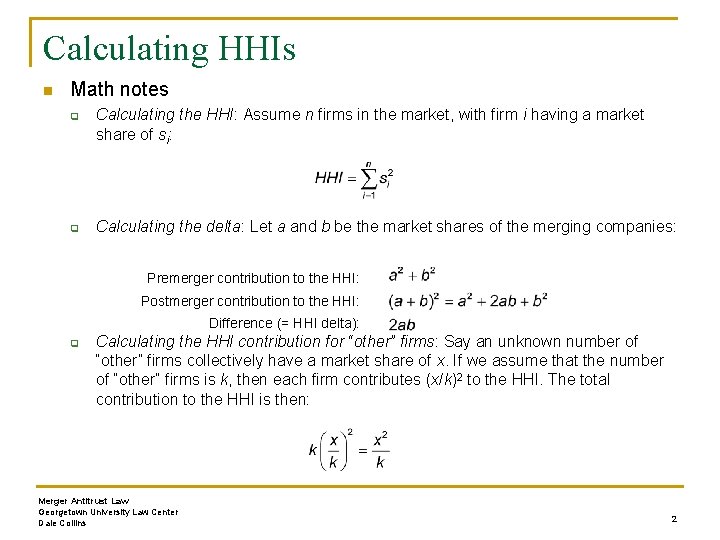

Calculating HHIs n Math notes q q Calculating the HHI: Assume n firms in the market, with firm i having a market share of si: Calculating the delta: Let a and b be the market shares of the merging companies: Premerger contribution to the HHI: Postmerger contribution to the HHI: Difference (= HHI delta): q Calculating the HHI contribution for “other” firms: Say an unknown number of “other” firms collectively have a market share of x. If we assume that the number of “other” firms is k, then each firm contributes (x/k)2 to the HHI. The total contribution to the HHI is then: Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 2

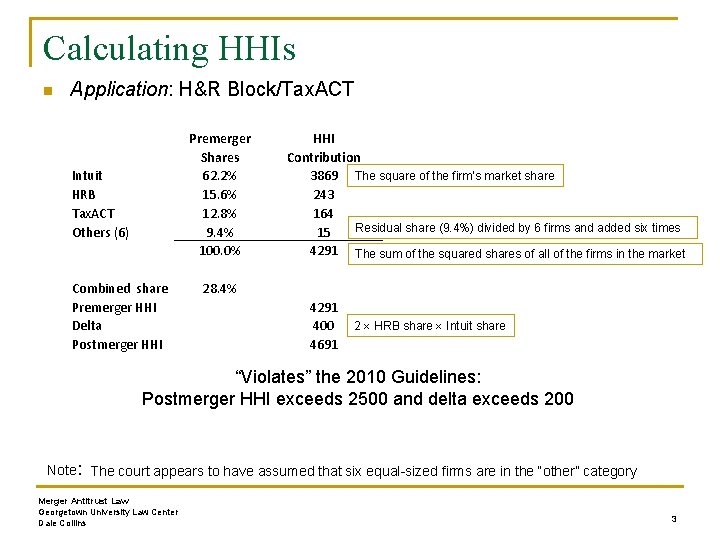

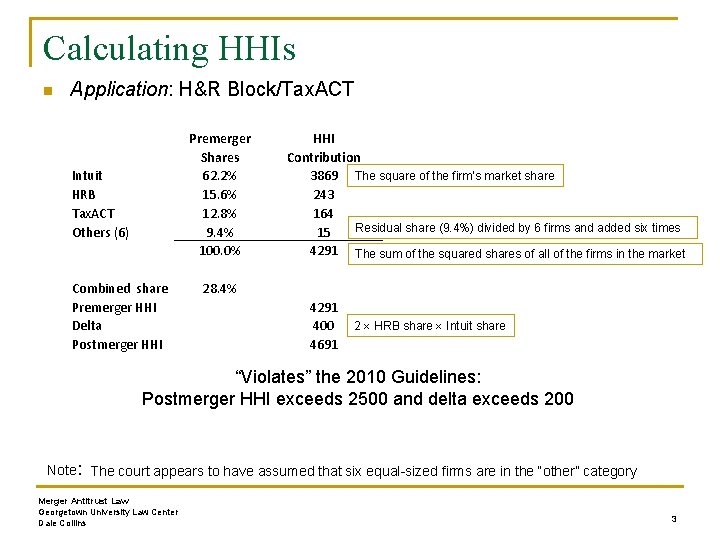

Calculating HHIs n Application: H&R Block/Tax. ACT Premerger Shares 62. 2% 15. 6% 12. 8% 9. 4% 100. 0% Intuit HRB Tax. ACT Others (6) Combined share Premerger HHI Delta Postmerger HHI Contribution 3869 The square of the firm’s market share 243 164 Residual share (9. 4%) divided by 6 firms and added six times 15 4291 The sum of the squared shares of all of the firms in the market 28. 4% 4291 400 4691 2 HRB share Intuit share “Violates” the 2010 Guidelines: Postmerger HHI exceeds 2500 and delta exceeds 200 Note: The court appears to have assumed that six equal-sized firms are in the “other” category Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 3

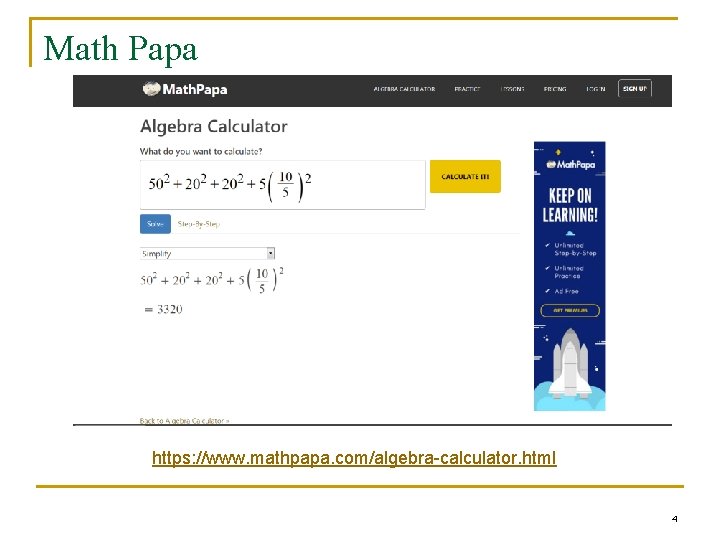

Math Papa https: //www. mathpapa. com/algebra-calculator. html 4

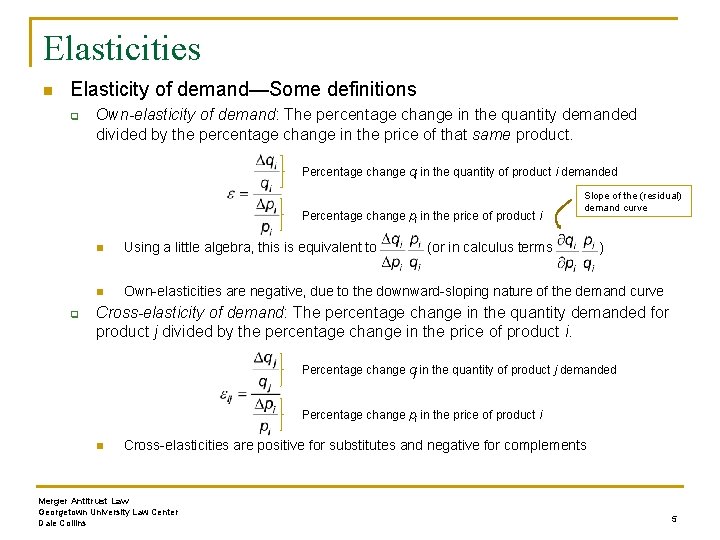

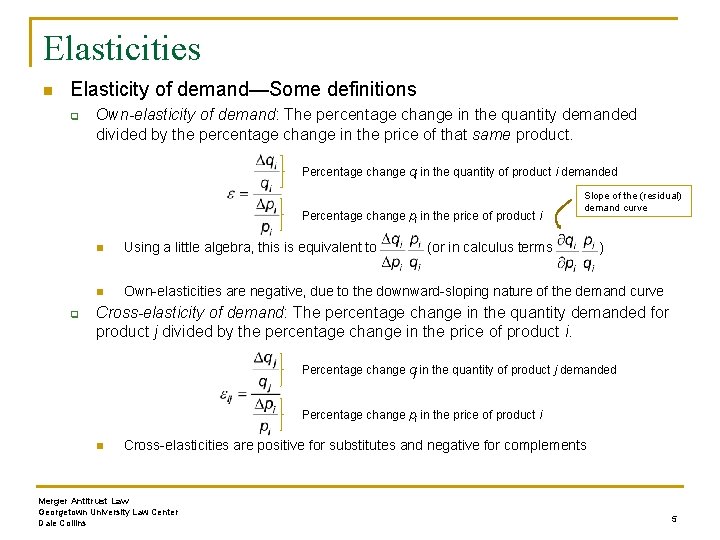

Elasticities n Elasticity of demand—Some definitions q Own-elasticity of demand: The percentage change in the quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in the price of that same product. Percentage change qi in the quantity of product i demanded Percentage change pi in the price of product i q Slope of the (residual) demand curve n Using a little algebra, this is equivalent to (or in calculus terms ) n Own-elasticities are negative, due to the downward-sloping nature of the demand curve Cross-elasticity of demand: The percentage change in the quantity demanded for product j divided by the percentage change in the price of product i. Percentage change qj in the quantity of product j demanded Percentage change pi in the price of product i n Cross-elasticities are positive for substitutes and negative for complements Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 5

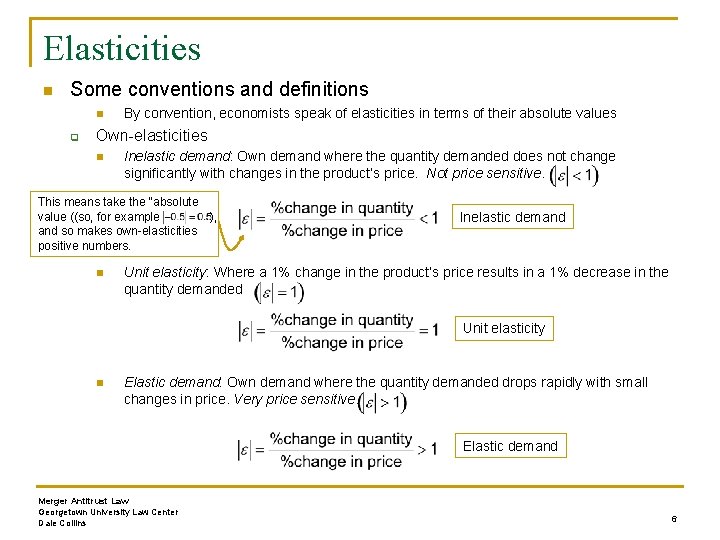

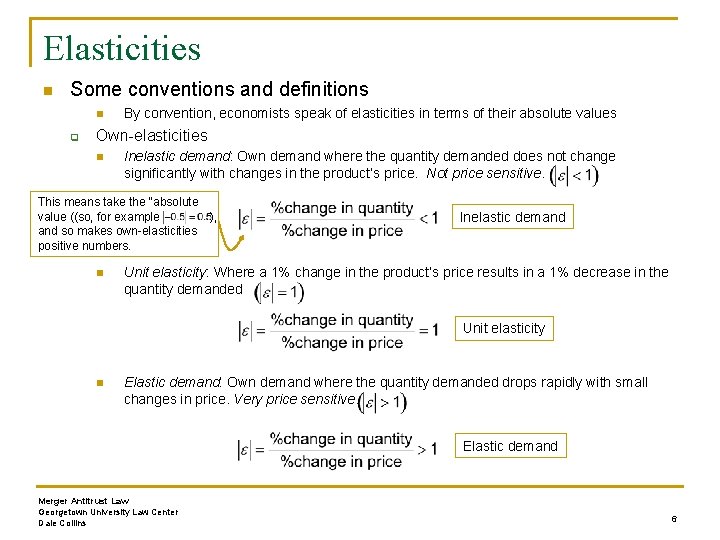

Elasticities n Some conventions and definitions n q By convention, economists speak of elasticities in terms of their absolute values Own-elasticities n Inelastic demand: Own demand where the quantity demanded does not change significantly with changes in the product’s price. Not price sensitive. This means take the “absolute value ((so, for example ), and so makes own-elasticities positive numbers. n Unit elasticity: Where a 1% change in the product’s price results in a 1% decrease in the quantity demanded Unit elasticity n Inelastic demand Elastic demand: Own demand where the quantity demanded drops rapidly with small changes in price. Very price sensitive. Elastic demand Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 6

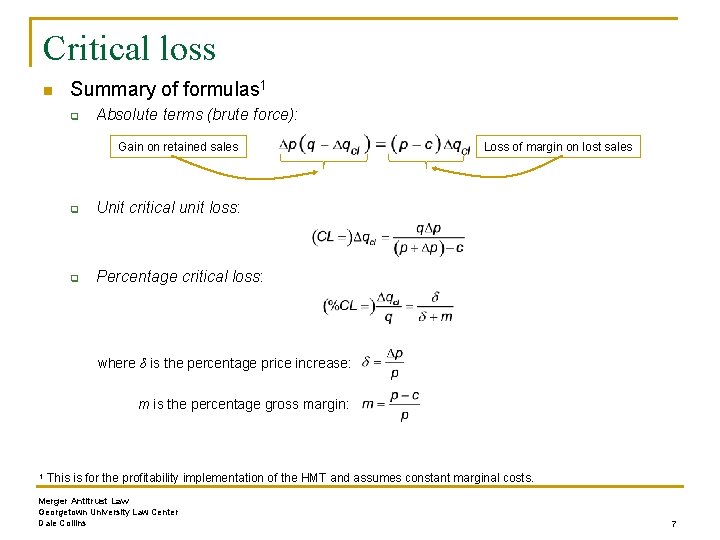

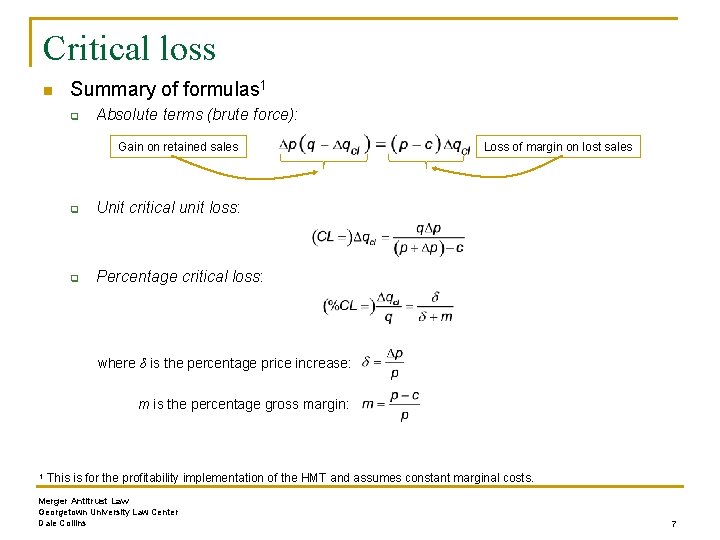

Critical loss n Summary of formulas 1 q Absolute terms (brute force): Gain on retained sales q Unit critical unit loss: q Percentage critical loss: Loss of margin on lost sales where δ is the percentage price increase: m is the percentage gross margin: 1 This is for the profitability implementation of the HMT and assumes constant marginal costs. Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 7

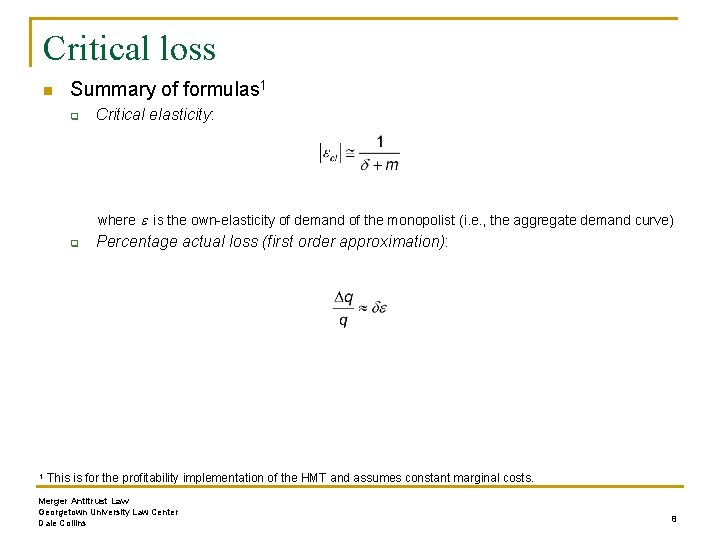

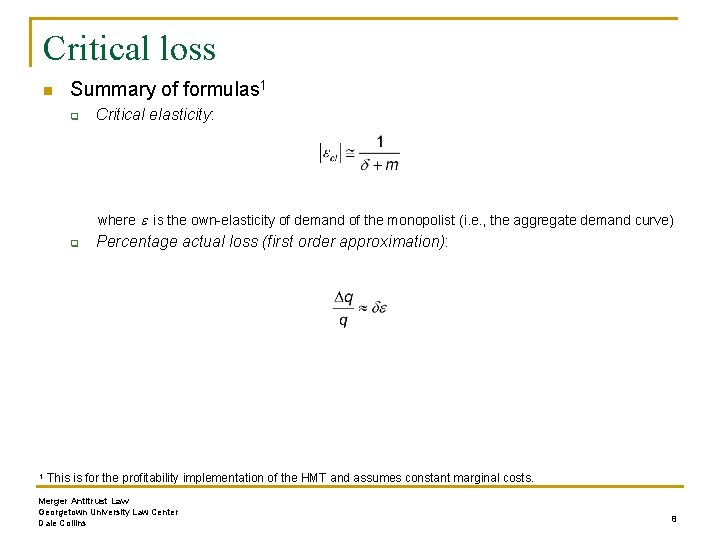

Critical loss n Summary of formulas 1 q Critical elasticity: where is the own-elasticity of demand of the monopolist (i. e. , the aggregate demand curve) q Percentage actual loss (first order approximation): 1 This is for the profitability implementation of the HMT and assumes constant marginal costs. Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 8

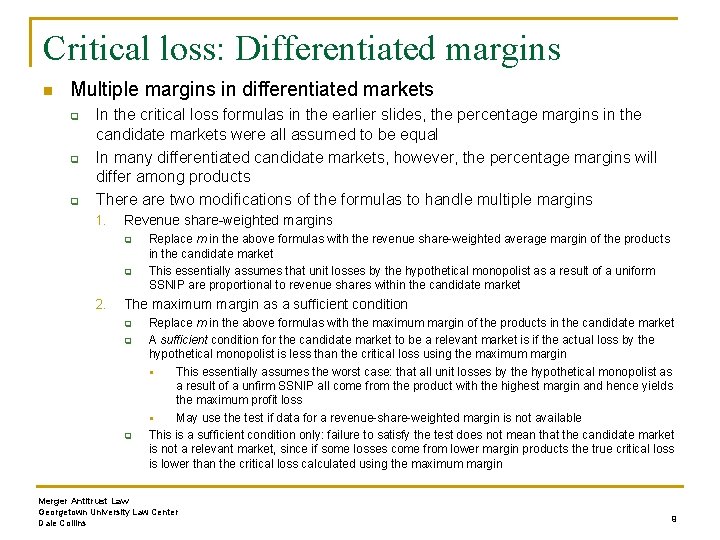

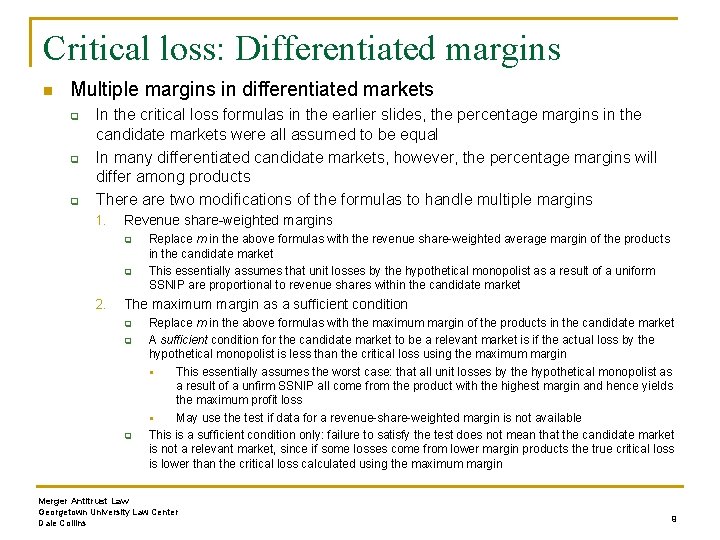

Critical loss: Differentiated margins n Multiple margins in differentiated markets q q q In the critical loss formulas in the earlier slides, the percentage margins in the candidate markets were all assumed to be equal In many differentiated candidate markets, however, the percentage margins will differ among products There are two modifications of the formulas to handle multiple margins 1. Revenue share-weighted margins q q 2. Replace m in the above formulas with the revenue share-weighted average margin of the products in the candidate market This essentially assumes that unit losses by the hypothetical monopolist as a result of a uniform SSNIP are proportional to revenue shares within the candidate market The maximum margin as a sufficient condition q q q Replace m in the above formulas with the maximum margin of the products in the candidate market A sufficient condition for the candidate market to be a relevant market is if the actual loss by the hypothetical monopolist is less than the critical loss using the maximum margin § This essentially assumes the worst case: that all unit losses by the hypothetical monopolist as a result of a unfirm SSNIP all come from the product with the highest margin and hence yields the maximum profit loss § May use the test if data for a revenue-share-weighted margin is not available This is a sufficient condition only: failure to satisfy the test does not mean that the candidate market is not a relevant market, since if some losses come from lower margin products the true critical loss is lower than the critical loss calculated using the maximum margin Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 9

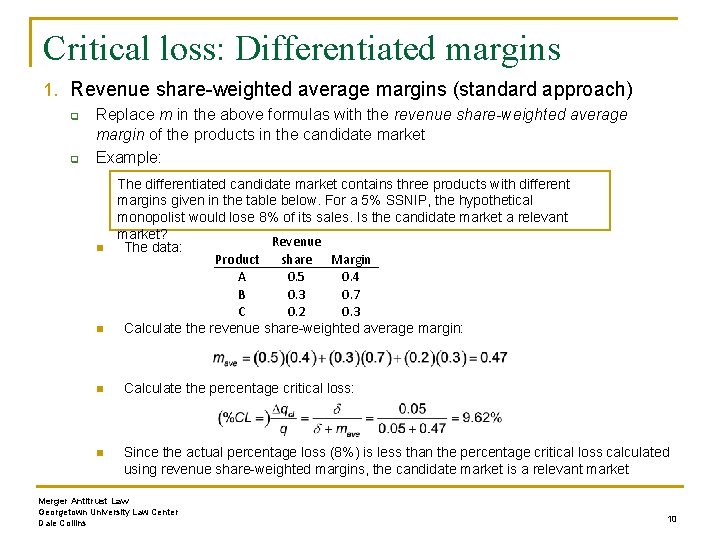

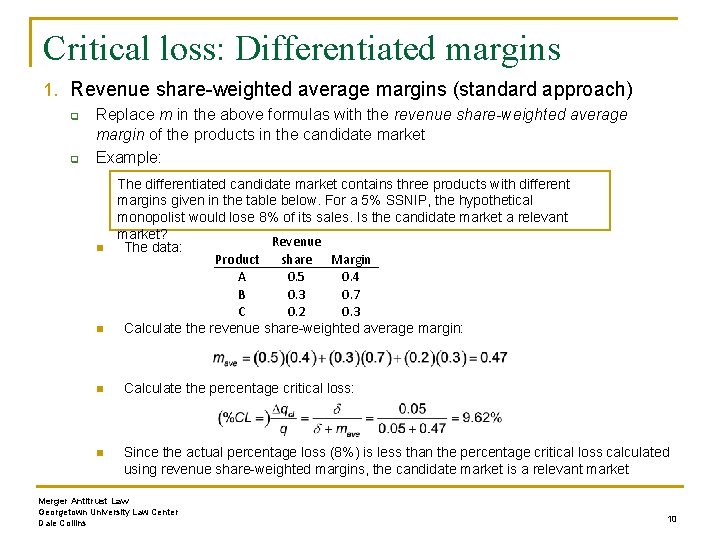

Critical loss: Differentiated margins 1. Revenue share-weighted average margins (standard approach) q q Replace m in the above formulas with the revenue share-weighted average margin of the products in the candidate market Example: n n The differentiated candidate market contains three products with different margins given in the table below. For a 5% SSNIP, the hypothetical monopolist would lose 8% of its sales. Is the candidate market a relevant market? Revenue The data: Product share Margin A 0. 5 0. 4 B 0. 3 0. 7 C 0. 2 0. 3 Calculate the revenue share-weighted average margin: n Calculate the percentage critical loss: n Since the actual percentage loss (8%) is less than the percentage critical loss calculated using revenue share-weighted margins, the candidate market is a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 10

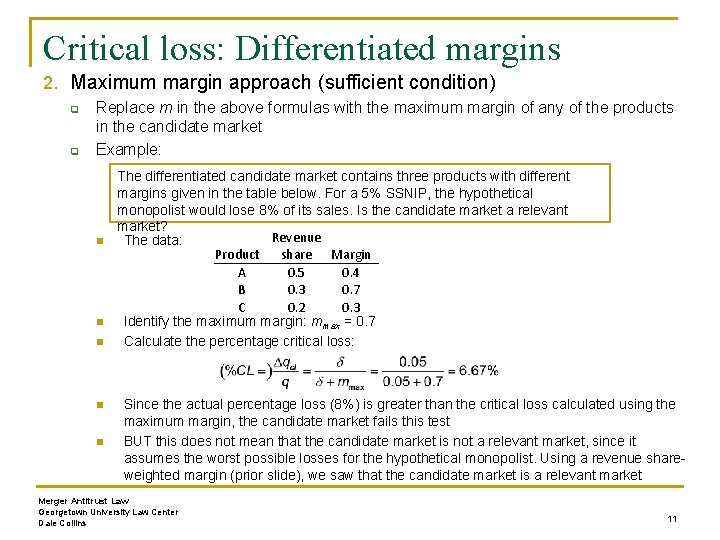

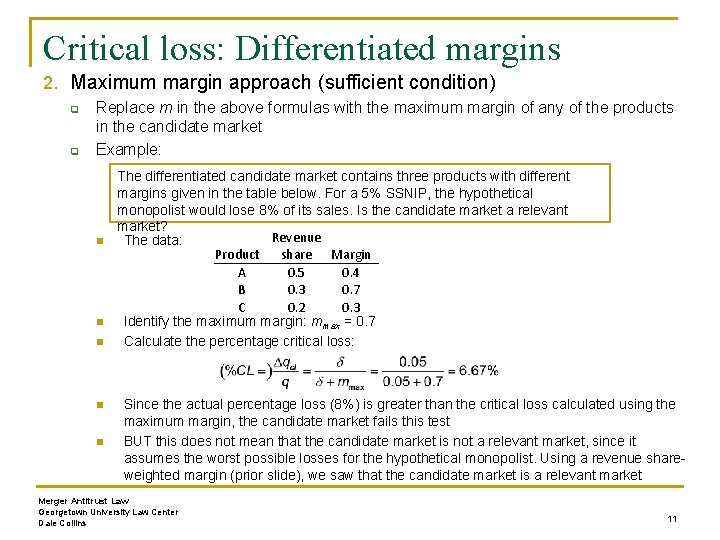

Critical loss: Differentiated margins 2. Maximum margin approach (sufficient condition) q q Replace m in the above formulas with the maximum margin of any of the products in the candidate market Example: n n n The differentiated candidate market contains three products with different margins given in the table below. For a 5% SSNIP, the hypothetical monopolist would lose 8% of its sales. Is the candidate market a relevant market? Revenue The data: Product share Margin A 0. 5 0. 4 B 0. 3 0. 7 C 0. 2 0. 3 Identify the maximum margin: mmax = 0. 7 Calculate the percentage critical loss: Since the actual percentage loss (8%) is greater than the critical loss calculated using the maximum margin, the candidate market fails this test BUT this does not mean that the candidate market is not a relevant market, since it assumes the worst possible losses for the hypothetical monopolist. Using a revenue shareweighted margin (prior slide), we saw that the candidate market is a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 11

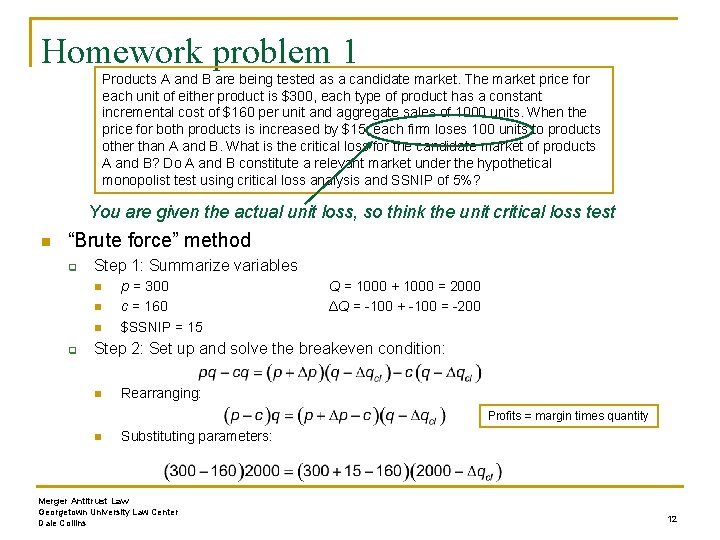

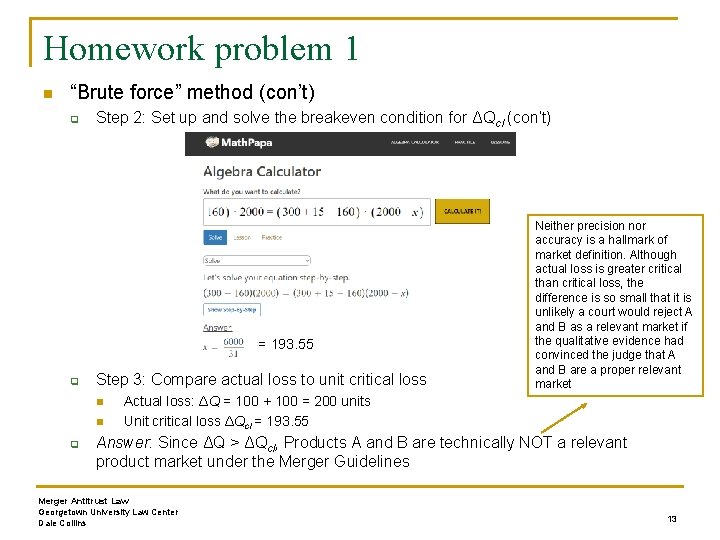

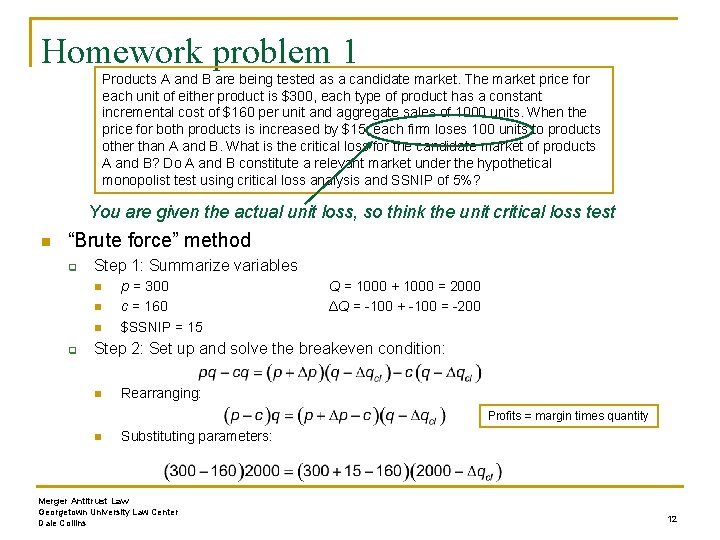

Homework problem 1 Products A and B are being tested as a candidate market. The market price for each unit of either product is $300, each type of product has a constant incremental cost of $160 per unit and aggregate sales of 1000 units. When the price for both products is increased by $15, each firm loses 100 units to products other than A and B. What is the critical loss for the candidate market of products A and B? Do A and B constitute a relevant market under the hypothetical monopolist test using critical loss analysis and SSNIP of 5%? You are given the actual unit loss, so think the unit critical loss test n “Brute force” method q Step 1: Summarize variables n n n q p = 300 c = 160 $SSNIP = 15 Q = 1000 + 1000 = 2000 ΔQ = -100 + -100 = -200 Step 2: Set up and solve the breakeven condition: n Rearranging: Profits = margin times quantity n Substituting parameters: Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 12

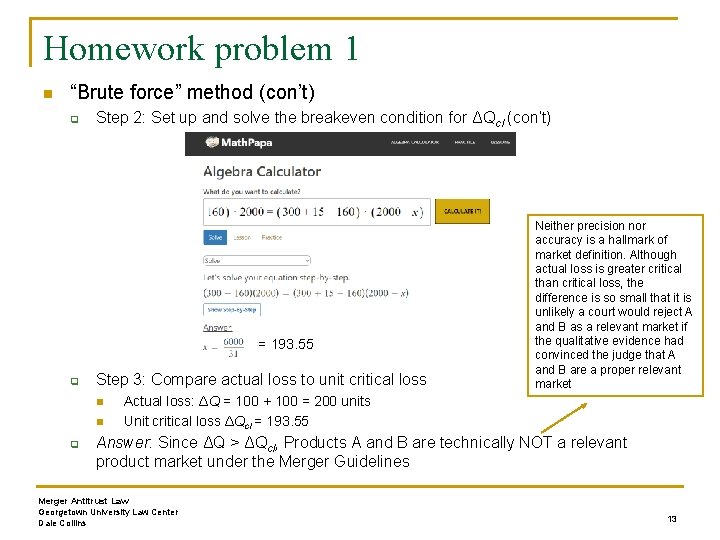

Homework problem 1 n “Brute force” method (con’t) q Step 2: Set up and solve the breakeven condition for ΔQcl (con’t) = 193. 55 q Step 3: Compare actual loss to unit critical loss n n q Neither precision nor accuracy is a hallmark of market definition. Although actual loss is greater critical than critical loss, the difference is so small that it is unlikely a court would reject A and B as a relevant market if the qualitative evidence had convinced the judge that A and B are a proper relevant market Actual loss: ΔQ = 100 + 100 = 200 units Unit critical loss ΔQcl = 193. 55 Answer: Since ΔQ > ΔQcl, Products A and B are technically NOT a relevant product market under the Merger Guidelines Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 13

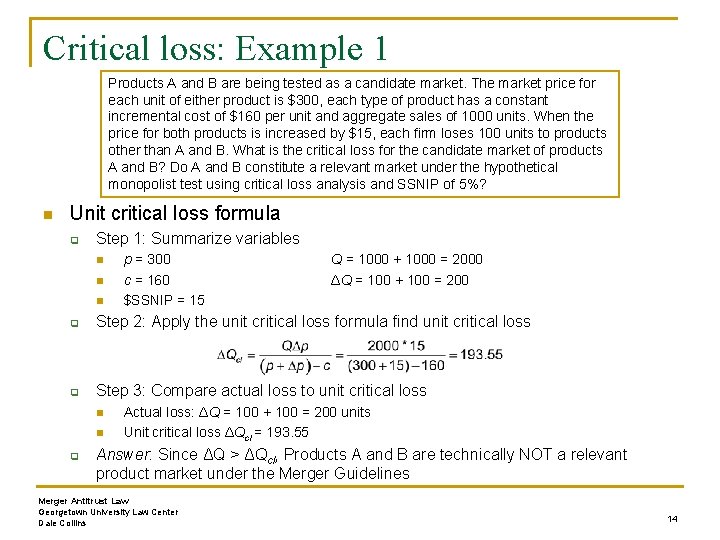

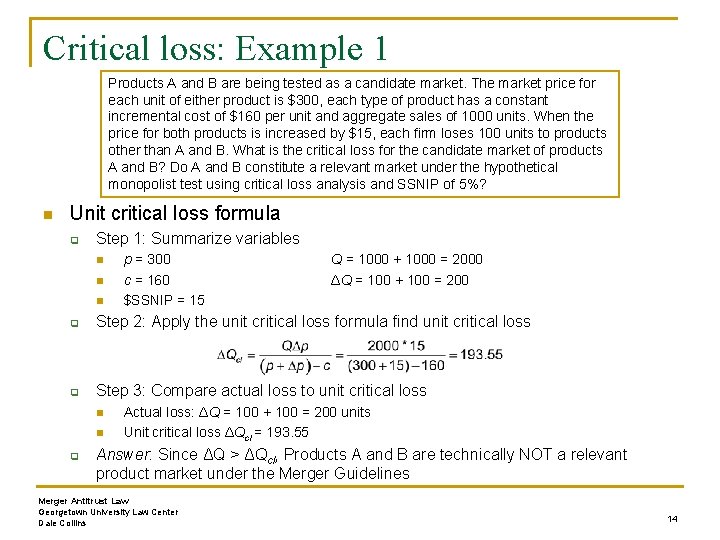

Critical loss: Example 1 Products A and B are being tested as a candidate market. The market price for each unit of either product is $300, each type of product has a constant incremental cost of $160 per unit and aggregate sales of 1000 units. When the price for both products is increased by $15, each firm loses 100 units to products other than A and B. What is the critical loss for the candidate market of products A and B? Do A and B constitute a relevant market under the hypothetical monopolist test using critical loss analysis and SSNIP of 5%? n Unit critical loss formula q Step 1: Summarize variables n n n p = 300 c = 160 $SSNIP = 15 Q = 1000 + 1000 = 2000 ΔQ = 100 + 100 = 200 q Step 2: Apply the unit critical loss formula find unit critical loss q Step 3: Compare actual loss to unit critical loss n n q Actual loss: ΔQ = 100 + 100 = 200 units Unit critical loss ΔQcl = 193. 55 Answer: Since ΔQ > ΔQcl, Products A and B are technically NOT a relevant product market under the Merger Guidelines Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 14

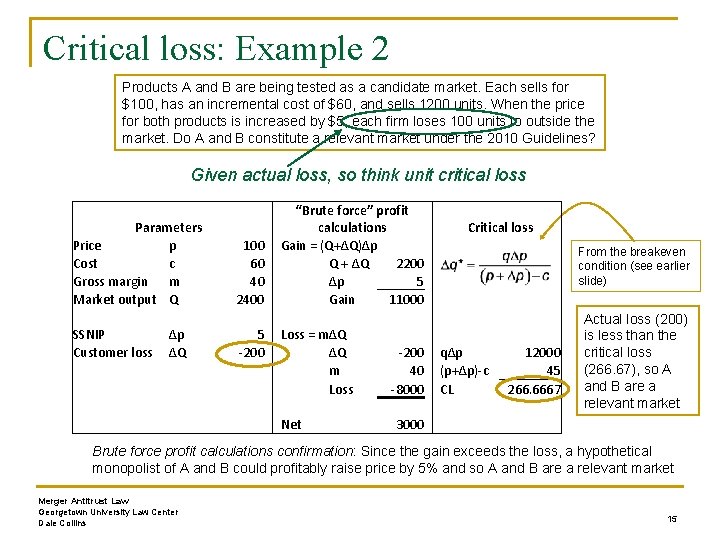

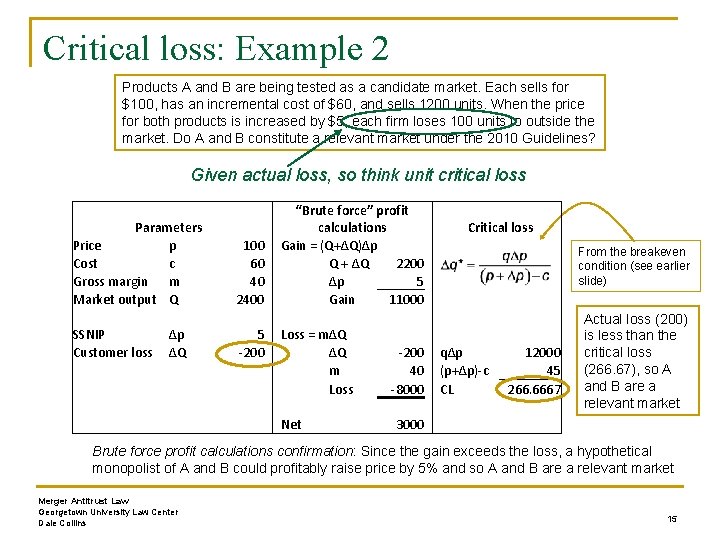

Critical loss: Example 2 Products A and B are being tested as a candidate market. Each sells for $100, has an incremental cost of $60, and sells 1200 units. When the price for both products is increased by $5, each firm loses 100 units to outside the market. Do A and B constitute a relevant market under the 2010 Guidelines? Given actual loss, so think unit critical loss Parameters Price p Cost c Gross margin m Market output Q SSNIP Δp Customer loss ΔQ “Brute force” profit calculations Critical loss 100 Gain = (Q+ΔQ)Δp 60 Q + ΔQ 2200 40 Δp 5 2400 Gain 11000 5 Loss = mΔQ -200 qΔp 12000 m 40 (p+Δp)-c 45 Loss -8000 CL 266. 6667 Net 3000 From the breakeven condition (see earlier slide) Actual loss (200) is less than the critical loss (266. 67), so A and B are a relevant market Brute force profit calculations confirmation: Since the gain exceeds the loss, a hypothetical monopolist of A and B could profitably raise price by 5% and so A and B are a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 15

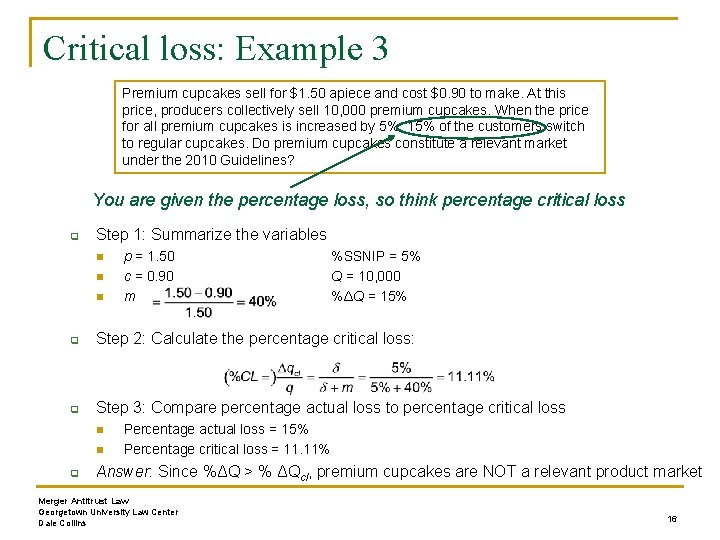

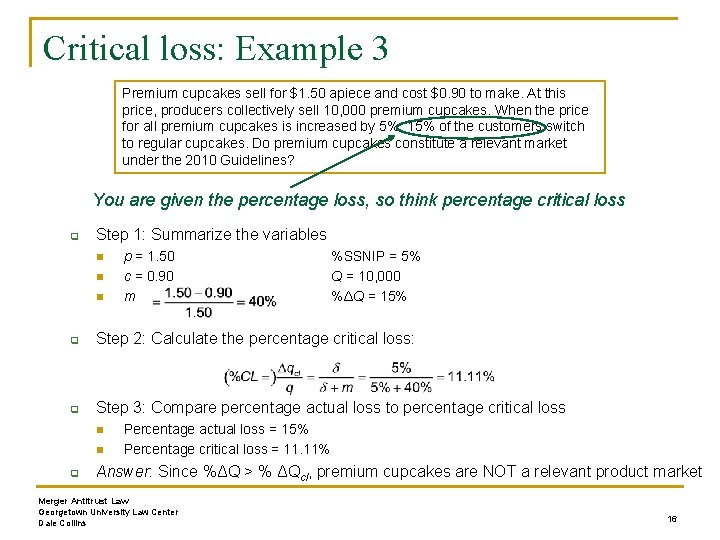

Critical loss: Example 3 Premium cupcakes sell for $1. 50 apiece and cost $0. 90 to make. At this price, producers collectively sell 10, 000 premium cupcakes. When the price for all premium cupcakes is increased by 5%, 15% of the customers switch to regular cupcakes. Do premium cupcakes constitute a relevant market under the 2010 Guidelines? You are given the percentage loss, so think percentage critical loss q Step 1: Summarize the variables n n n p = 1. 50 c = 0. 90 m %SSNIP = 5% Q = 10, 000 %ΔQ = 15% q Step 2: Calculate the percentage critical loss: q Step 3: Compare percentage actual loss to percentage critical loss n n q Percentage actual loss = 15% Percentage critical loss = 11. 11% Answer: Since %ΔQ > % ΔQcl, premium cupcakes are NOT a relevant product market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 16

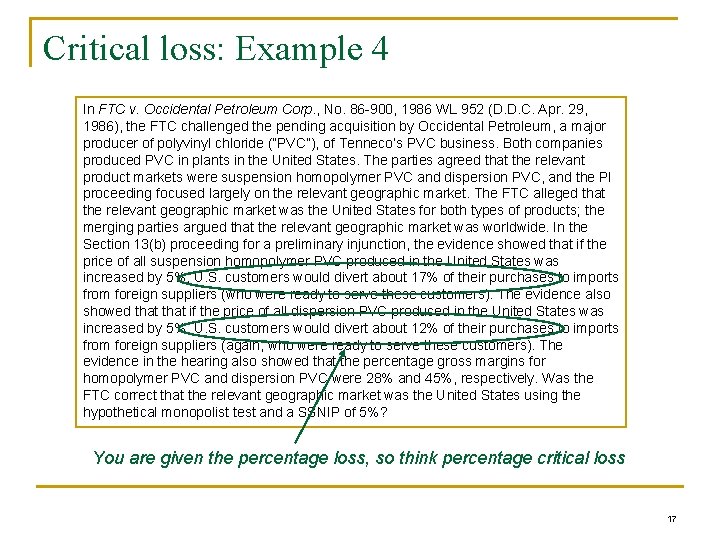

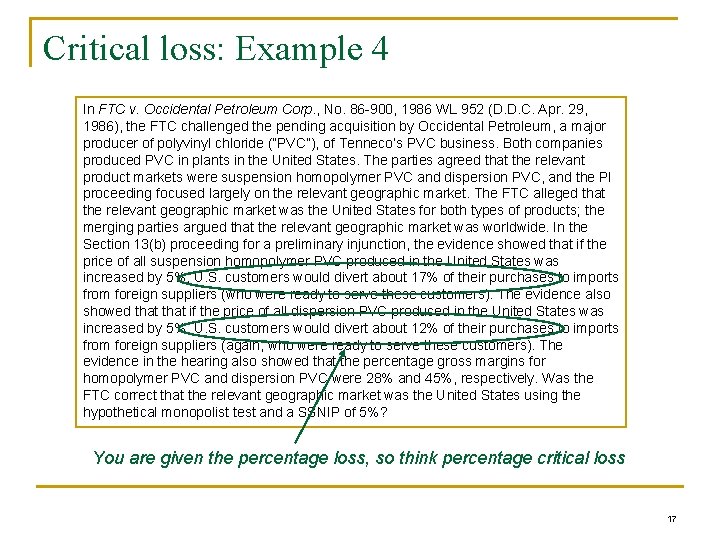

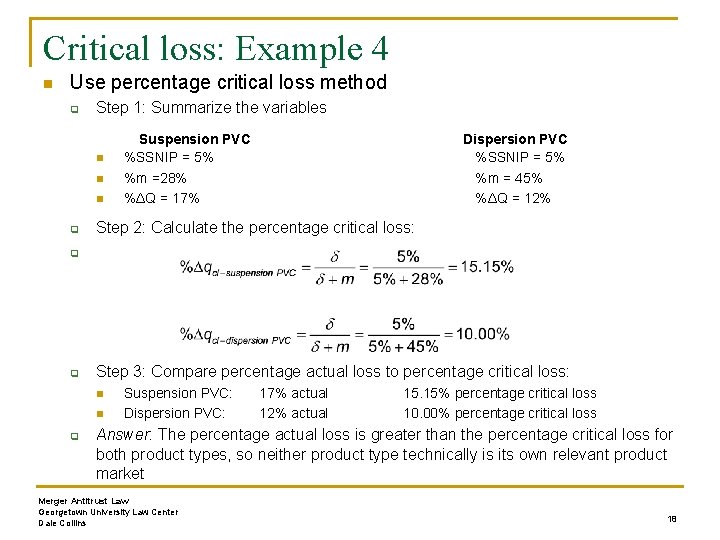

Critical loss: Example 4 In FTC v. Occidental Petroleum Corp. , No. 86 -900, 1986 WL 952 (D. D. C. Apr. 29, 1986), the FTC challenged the pending acquisition by Occidental Petroleum, a major producer of polyvinyl chloride (“PVC”), of Tenneco’s PVC business. Both companies produced PVC in plants in the United States. The parties agreed that the relevant product markets were suspension homopolymer PVC and dispersion PVC, and the PI proceeding focused largely on the relevant geographic market. The FTC alleged that the relevant geographic market was the United States for both types of products; the merging parties argued that the relevant geographic market was worldwide. In the Section 13(b) proceeding for a preliminary injunction, the evidence showed that if the price of all suspension homopolymer PVC produced in the United States was increased by 5%, U. S. customers would divert about 17% of their purchases to imports from foreign suppliers (who were ready to serve these customers). The evidence also showed that if the price of all dispersion PVC produced in the United States was increased by 5%, U. S. customers would divert about 12% of their purchases to imports from foreign suppliers (again, who were ready to serve these customers). The evidence in the hearing also showed that the percentage gross margins for homopolymer PVC and dispersion PVC were 28% and 45%, respectively. Was the FTC correct that the relevant geographic market was the United States using the hypothetical monopolist test and a SSNIP of 5%? You are given the percentage loss, so think percentage critical loss 17

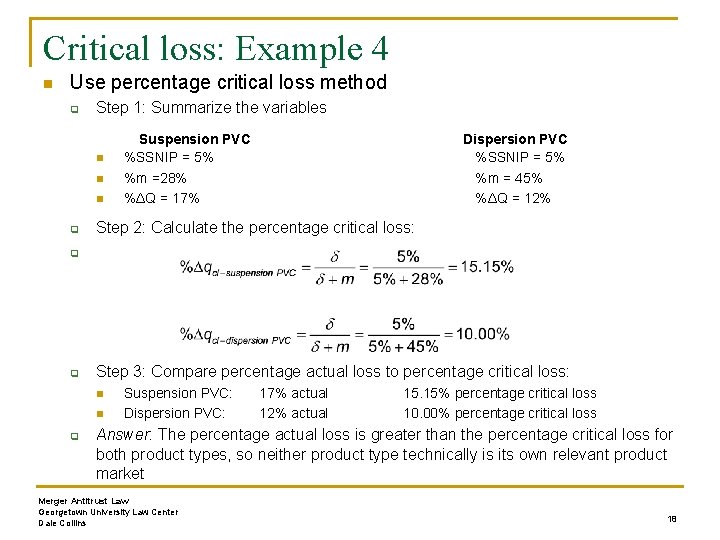

Critical loss: Example 4 n Use percentage critical loss method q Step 1: Summarize the variables n n n Suspension PVC %SSNIP = 5% %m =28% %ΔQ = 17% Dispersion PVC %SSNIP = 5% %m = 45% %ΔQ = 12% q Step 2: Calculate the percentage critical loss: q Step 3: Compare percentage actual loss to percentage critical loss: q n n q Suspension PVC: Dispersion PVC: 17% actual 12% actual 15. 15% percentage critical loss 10. 00% percentage critical loss Answer: The percentage actual loss is greater than the percentage critical loss for both product types, so neither product type technically is its own relevant product market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 18

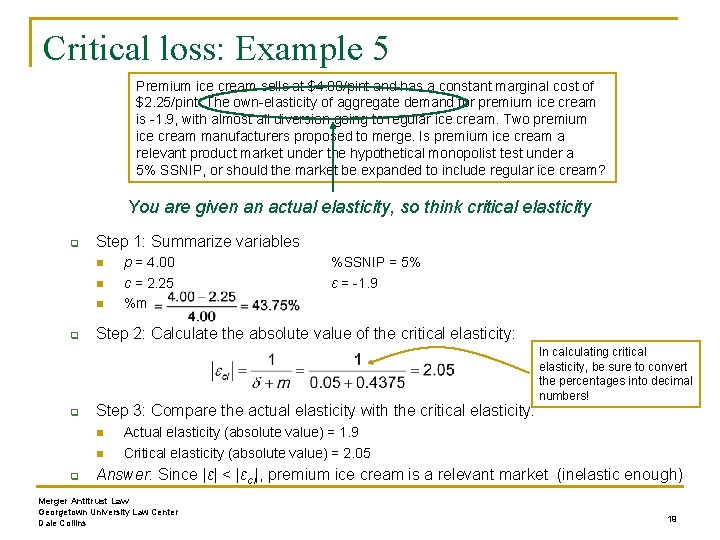

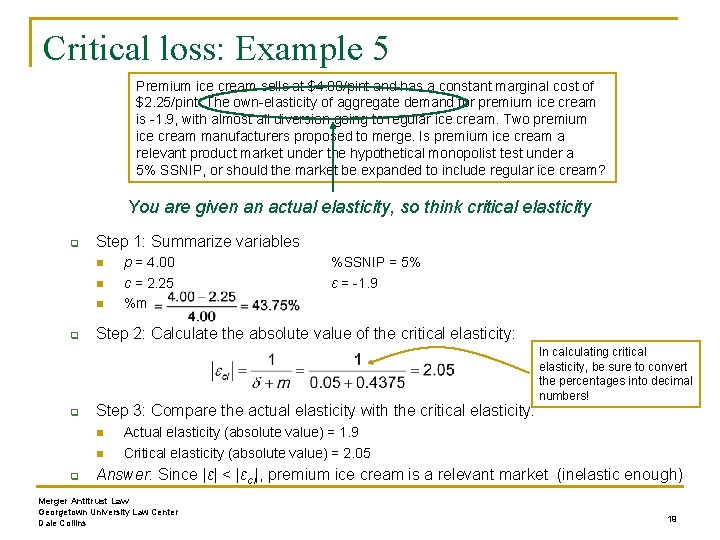

Critical loss: Example 5 Premium ice cream sells at $4. 00/pint and has a constant marginal cost of $2. 25/pint. The own-elasticity of aggregate demand for premium ice cream is -1. 9, with almost all diversion going to regular ice cream. Two premium ice cream manufacturers proposed to merge. Is premium ice cream a relevant product market under the hypothetical monopolist test under a 5% SSNIP, or should the market be expanded to include regular ice cream? You are given an actual elasticity, so think critical elasticity q Step 1: Summarize variables n n n q q %SSNIP = 5% ε = -1. 9 Step 2: Calculate the absolute value of the critical elasticity: Step 3: Compare the actual elasticity with the critical elasticity: n n q p = 4. 00 c = 2. 25 %m In calculating critical elasticity, be sure to convert the percentages into decimal numbers! Actual elasticity (absolute value) = 1. 9 Critical elasticity (absolute value) = 2. 05 Answer: Since |ε| < |εcl|, premium ice cream is a relevant market (inelastic enough) Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 19

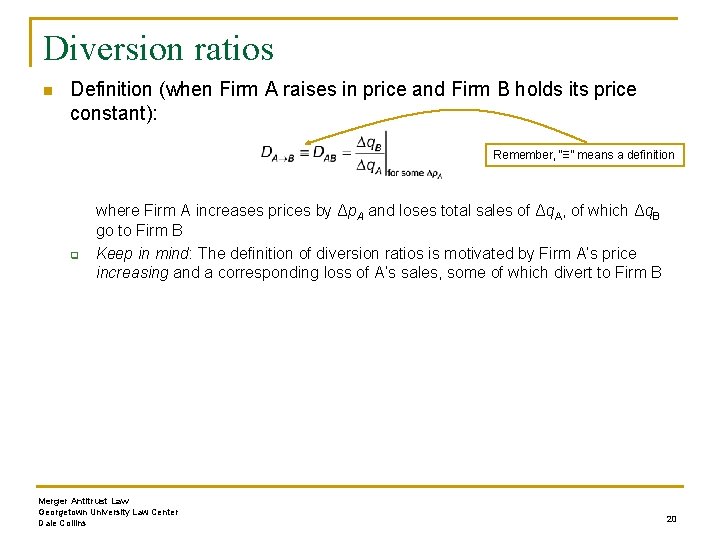

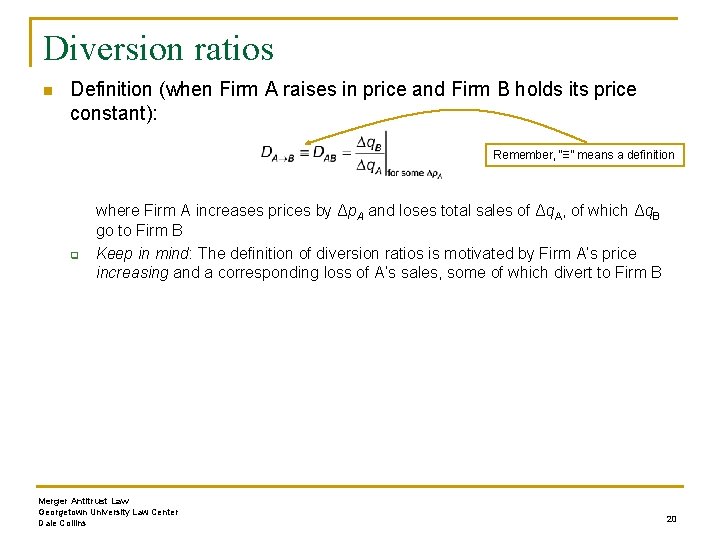

Diversion ratios n Definition (when Firm A raises in price and Firm B holds its price constant): Remember, “≡” means a definition q where Firm A increases prices by Δp. A and loses total sales of Δq. A, of which Δq. B go to Firm B Keep in mind: The definition of diversion ratios is motivated by Firm A’s price increasing and a corresponding loss of A’s sales, some of which divert to Firm B Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 20

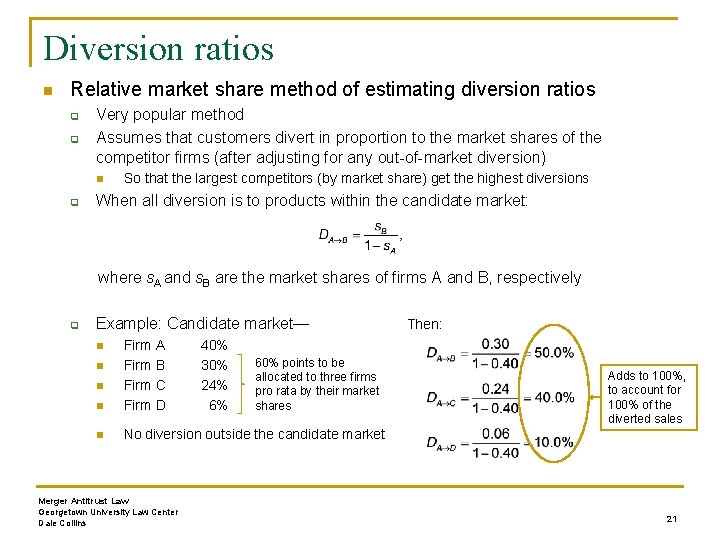

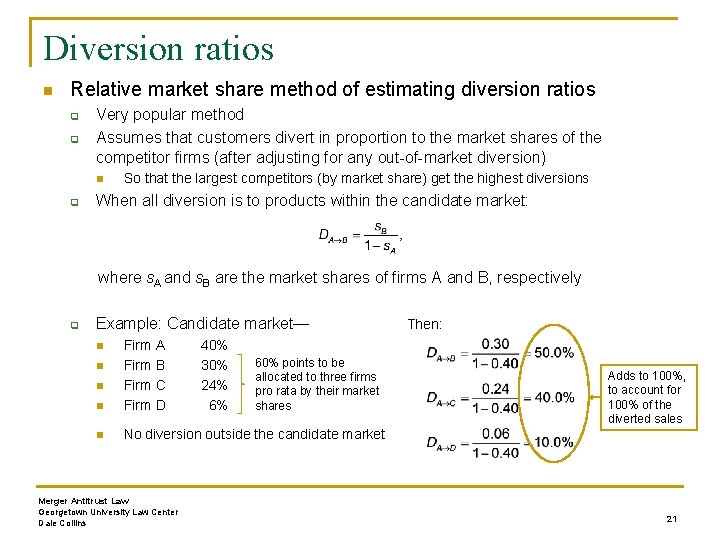

Diversion ratios n Relative market share method of estimating diversion ratios q q Very popular method Assumes that customers divert in proportion to the market shares of the competitor firms (after adjusting for any out-of-market diversion) n q So that the largest competitors (by market share) get the highest diversions When all diversion is to products within the candidate market: where s. A and s. B are the market shares of firms A and B, respectively q Example: Candidate market— n Firm A Firm B Firm C Firm D n No diversion outside the candidate market n n n Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 40% 30% 24% 6% 60% points to be allocated to three firms pro rata by their market shares Then: Adds to 100%, to account for 100% of the diverted sales 21

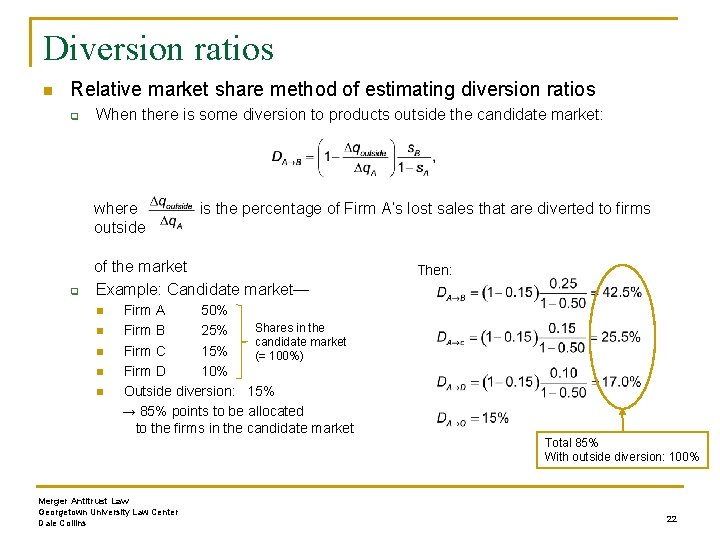

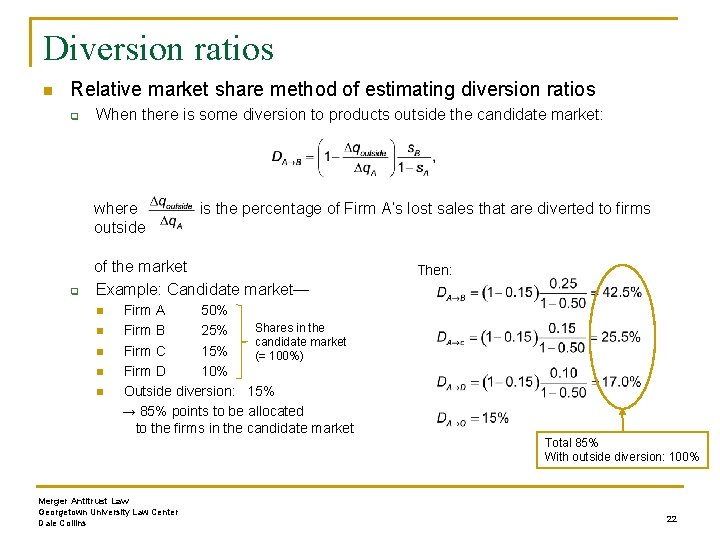

Diversion ratios n Relative market share method of estimating diversion ratios q When there is some diversion to products outside the candidate market: where is the percentage of Firm A’s lost sales that are diverted to firms outside q of the market Example: Candidate market— n n n Then: Firm A 50% Shares in the Firm B 25% candidate market Firm C 15% (= 100%) Firm D 10% Outside diversion: 15% → 85% points to be allocated to the firms in the candidate market Total 85% With outside diversion: 100% Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 22

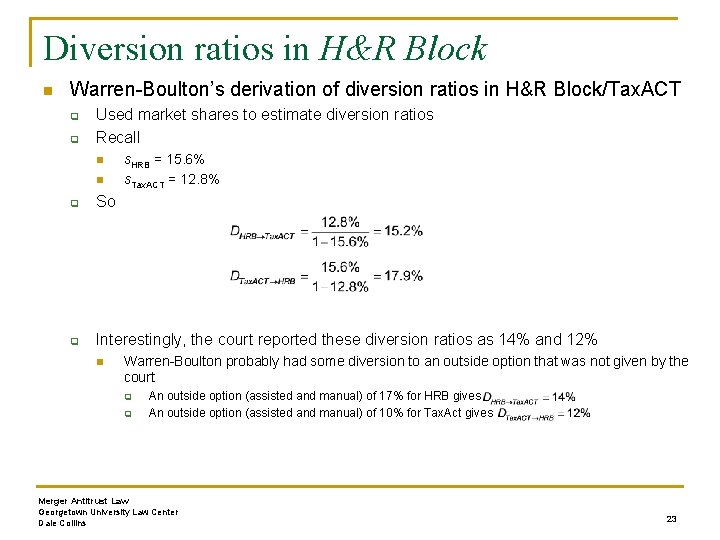

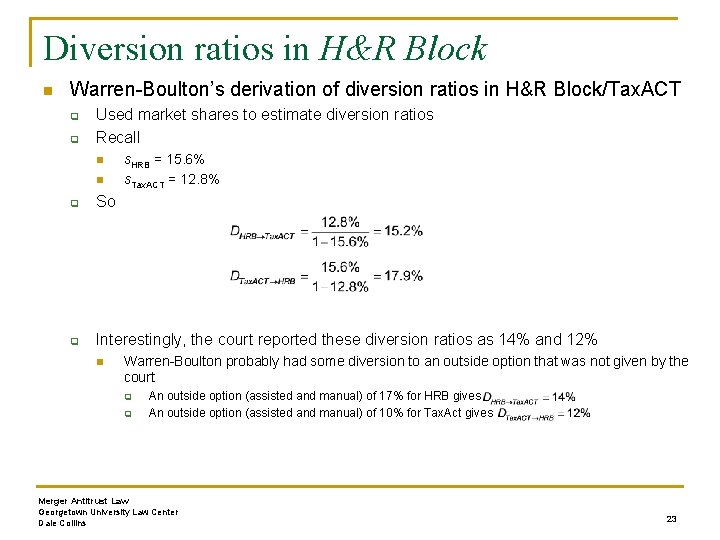

Diversion ratios in H&R Block n Warren-Boulton’s derivation of diversion ratios in H&R Block/Tax. ACT q q Used market shares to estimate diversion ratios Recall n n s. HRB = 15. 6% s. Tax. ACT = 12. 8% q So q Interestingly, the court reported these diversion ratios as 14% and 12% n Warren-Boulton probably had some diversion to an outside option that was not given by the court q q An outside option (assisted and manual) of 17% for HRB gives An outside option (assisted and manual) of 10% for Tax. Act gives Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 23

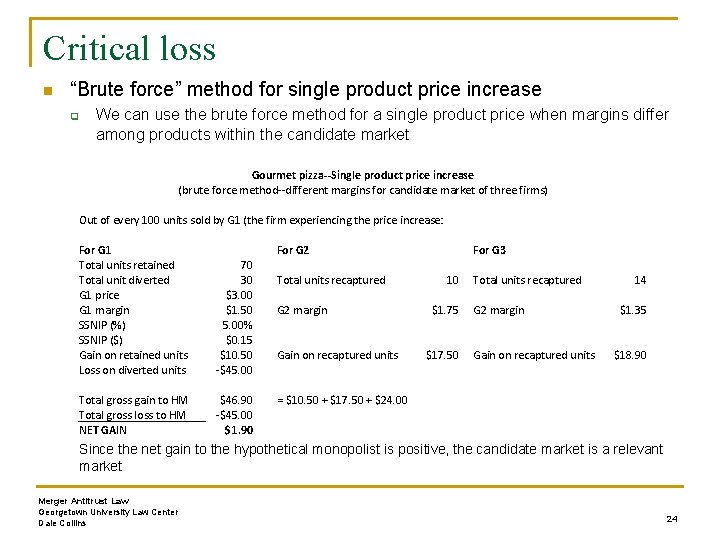

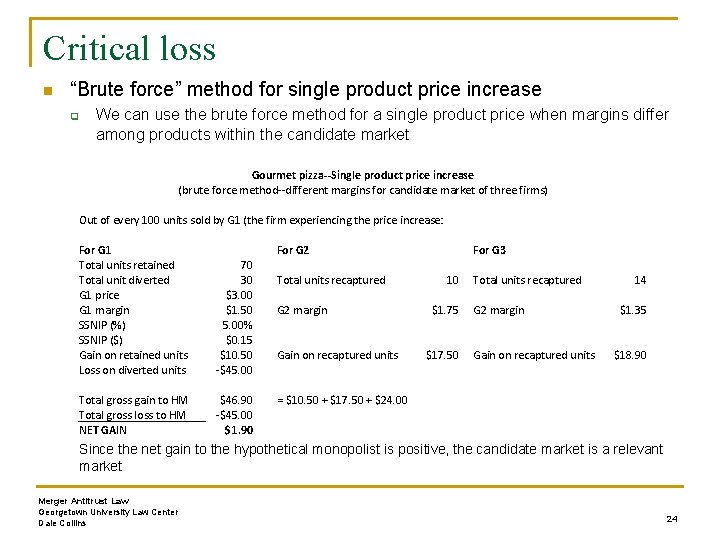

Critical loss n “Brute force” method for single product price increase q We can use the brute force method for a single product price when margins differ among products within the candidate market Gourmet pizza--Single product price increase (brute force method--different margins for candidate market of three firms) Out of every 100 units sold by G 1 (the firm experiencing the price increase: For G 1 Total units retained Total unit diverted G 1 price G 1 margin SSNIP (%) SSNIP ($) Gain on retained units Loss on diverted units For G 2 70 30 $3. 00 $1. 50 5. 00% $0. 15 $10. 50 -$45. 00 Total gross gain to HM Total gross loss to HM NET GAIN $46. 90 -$45. 00 $1. 90 Total units recaptured G 2 margin Gain on recaptured units For G 3 10 Total units recaptured $1. 75 G 2 margin $17. 50 Gain on recaptured units 14 $1. 35 $18. 90 = $10. 50 + $17. 50 + $24. 00 Since the net gain to the hypothetical monopolist is positive, the candidate market is a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 24

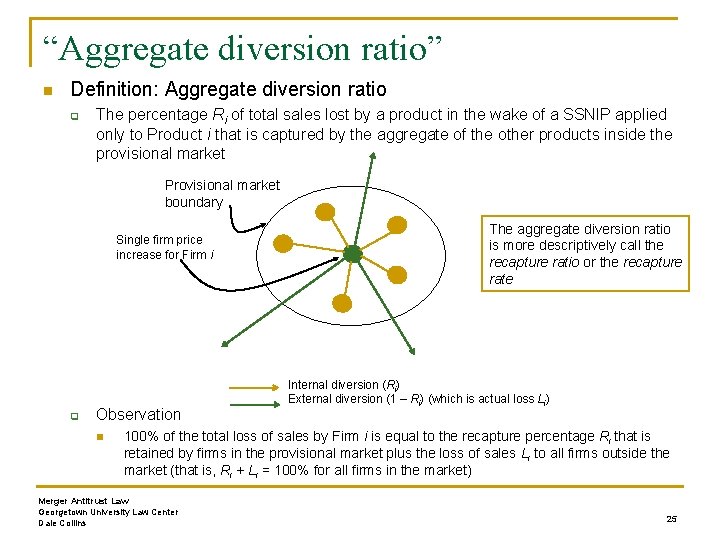

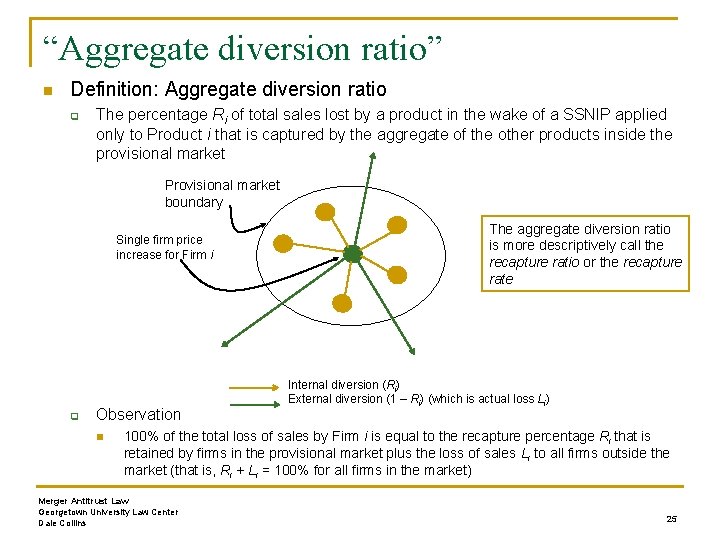

“Aggregate diversion ratio” n Definition: Aggregate diversion ratio q The percentage Ri of total sales lost by a product in the wake of a SSNIP applied only to Product i that is captured by the aggregate of the other products inside the provisional market Provisional market boundary Single firm price increase for Firm i q Observation n The aggregate diversion ratio is more descriptively call the recapture ratio or the recapture rate Internal diversion (Ri) External diversion (1 – Ri) (which is actual loss Li) 100% of the total loss of sales by Firm i is equal to the recapture percentage Ri that is retained by firms in the provisional market plus the loss of sales Li to all firms outside the market (that is, Ri + Li = 100% for all firms in the market) Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 25

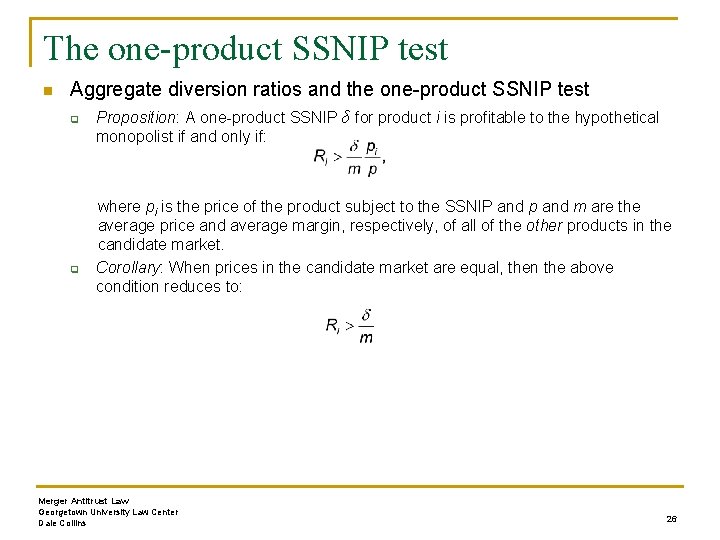

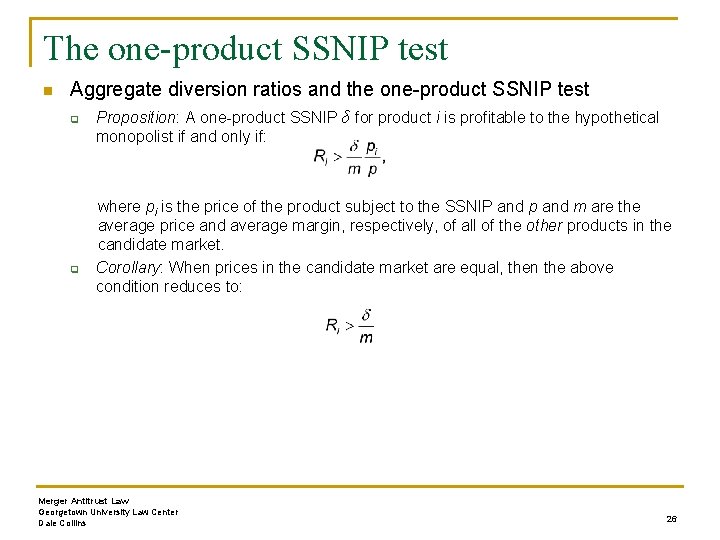

The one-product SSNIP test n Aggregate diversion ratios and the one-product SSNIP test q q Proposition: A one-product SSNIP δ for product i is profitable to the hypothetical monopolist if and only if: where pi is the price of the product subject to the SSNIP and p and m are the average price and average margin, respectively, of all of the other products in the candidate market. Corollary: When prices in the candidate market are equal, then the above condition reduces to: Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 26

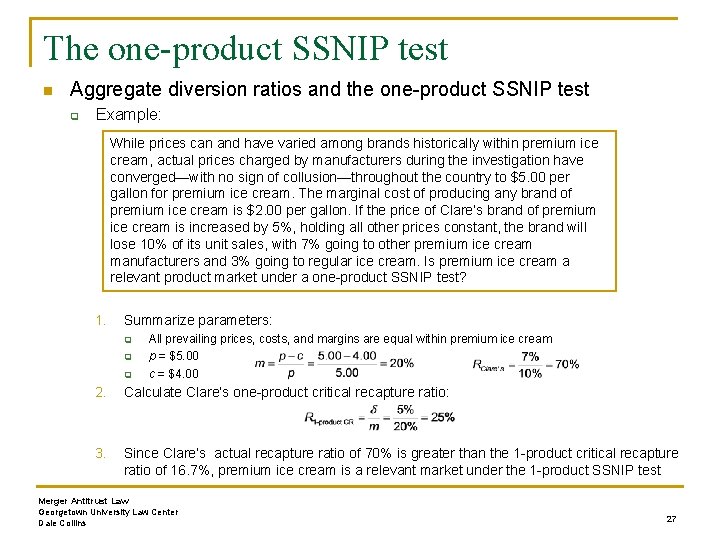

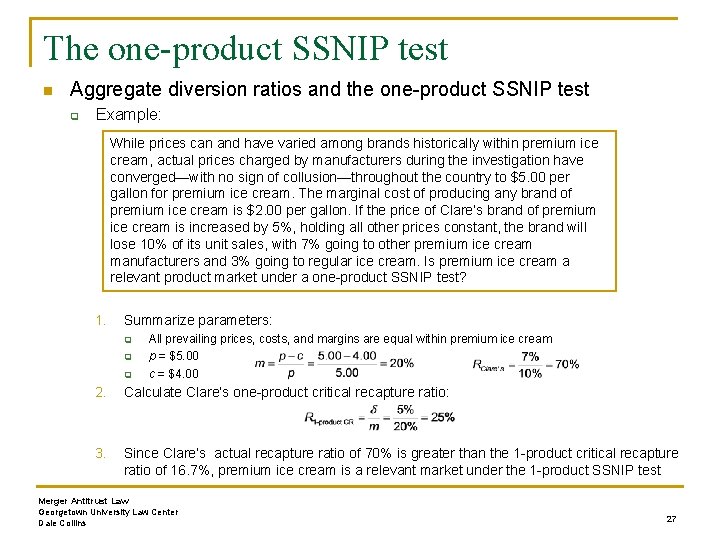

The one-product SSNIP test n Aggregate diversion ratios and the one-product SSNIP test q Example: While prices can and have varied among brands historically within premium ice cream, actual prices charged by manufacturers during the investigation have converged—with no sign of collusion—throughout the country to $5. 00 per gallon for premium ice cream. The marginal cost of producing any brand of premium ice cream is $2. 00 per gallon. If the price of Clare’s brand of premium ice cream is increased by 5%, holding all other prices constant, the brand will lose 10% of its unit sales, with 7% going to other premium ice cream manufacturers and 3% going to regular ice cream. Is premium ice cream a relevant product market under a one-product SSNIP test? 1. Summarize parameters: q q q All prevailing prices, costs, and margins are equal within premium ice cream p = $5. 00 c = $4. 00 2. Calculate Clare’s one-product critical recapture ratio: 3. Since Clare’s actual recapture ratio of 70% is greater than the 1 -product critical recapture ratio of 16. 7%, premium ice cream is a relevant market under the 1 -product SSNIP test Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 27

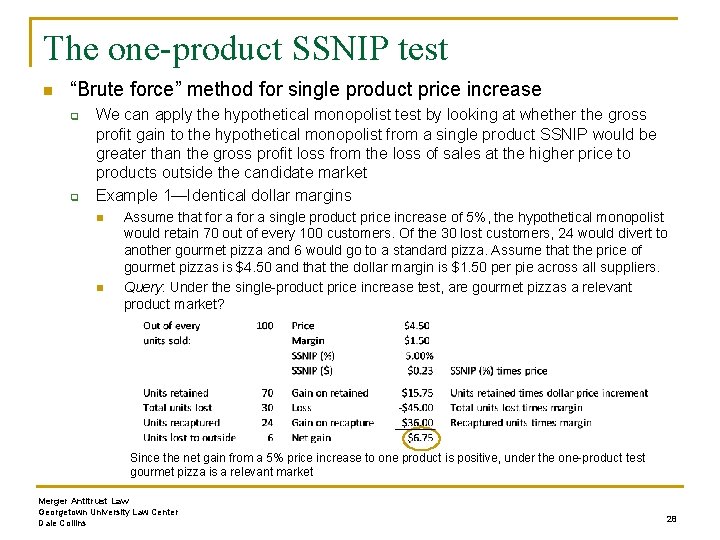

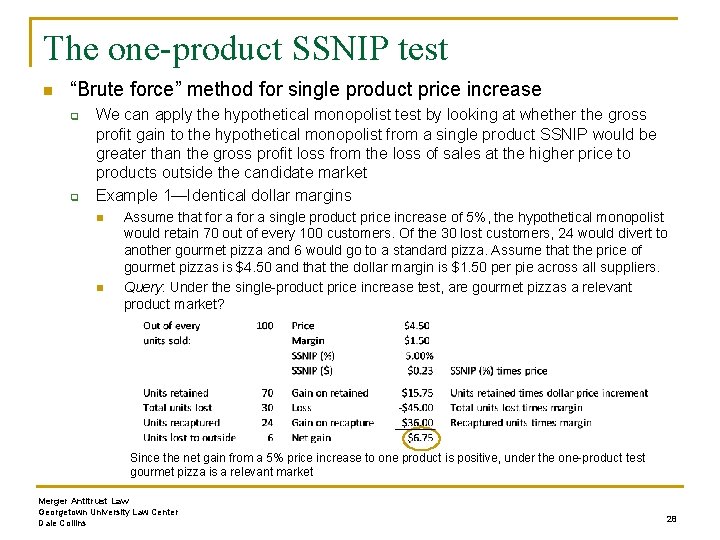

The one-product SSNIP test n “Brute force” method for single product price increase q q We can apply the hypothetical monopolist test by looking at whether the gross profit gain to the hypothetical monopolist from a single product SSNIP would be greater than the gross profit loss from the loss of sales at the higher price to products outside the candidate market Example 1—Identical dollar margins n n Assume that for a single product price increase of 5%, the hypothetical monopolist would retain 70 out of every 100 customers. Of the 30 lost customers, 24 would divert to another gourmet pizza and 6 would go to a standard pizza. Assume that the price of gourmet pizzas is $4. 50 and that the dollar margin is $1. 50 per pie across all suppliers. Query: Under the single-product price increase test, are gourmet pizzas a relevant product market? Since the net gain from a 5% price increase to one product is positive, under the one-product test gourmet pizza is a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 28

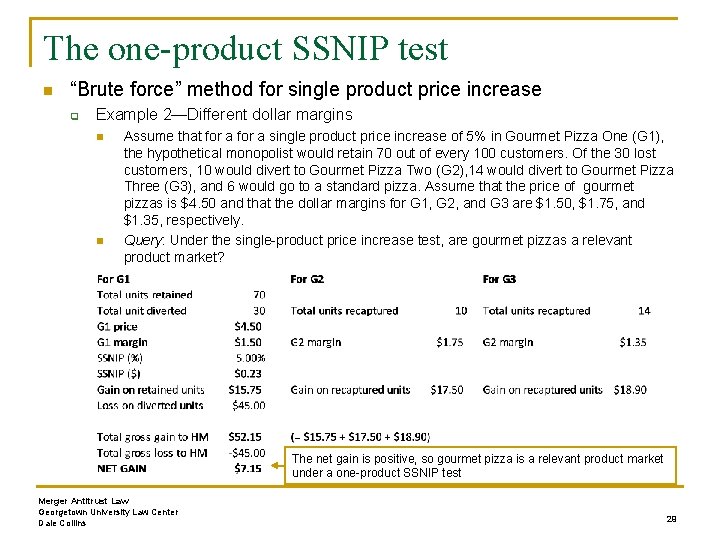

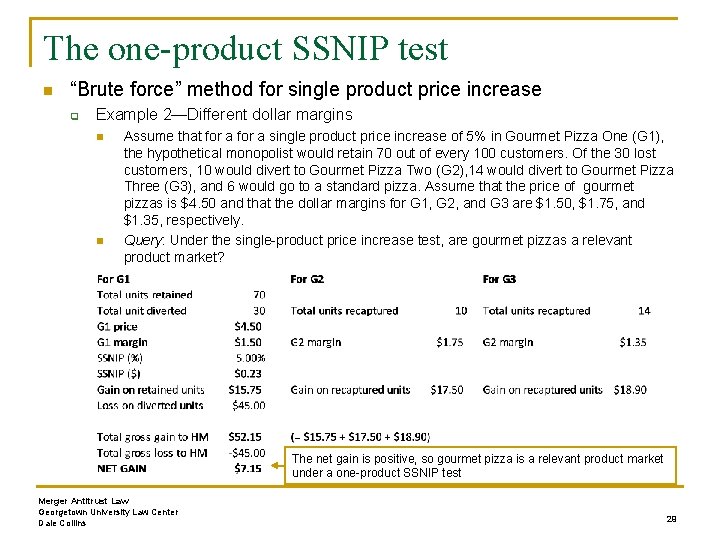

The one-product SSNIP test n “Brute force” method for single product price increase q Example 2—Different dollar margins n n Assume that for a single product price increase of 5% in Gourmet Pizza One (G 1), the hypothetical monopolist would retain 70 out of every 100 customers. Of the 30 lost customers, 10 would divert to Gourmet Pizza Two (G 2), 14 would divert to Gourmet Pizza Three (G 3), and 6 would go to a standard pizza. Assume that the price of gourmet pizzas is $4. 50 and that the dollar margins for G 1, G 2, and G 3 are $1. 50, $1. 75, and $1. 35, respectively. Query: Under the single-product price increase test, are gourmet pizzas a relevant product market? The net gain is positive, so gourmet pizza is a relevant product market under a one-product SSNIP test Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 29

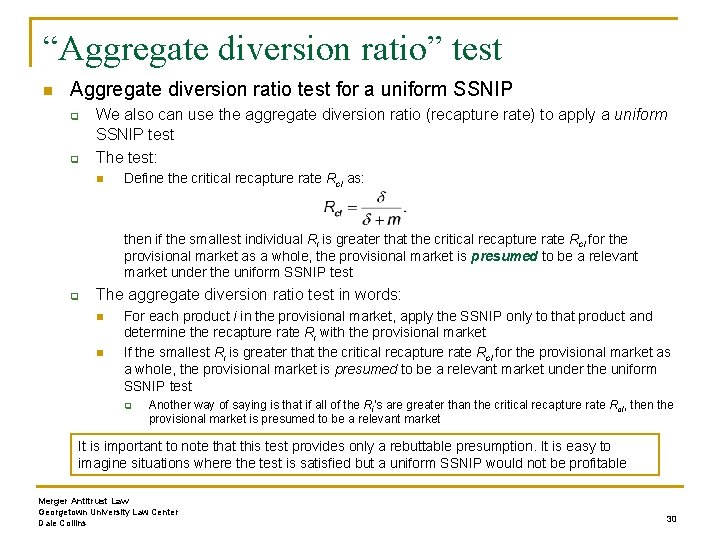

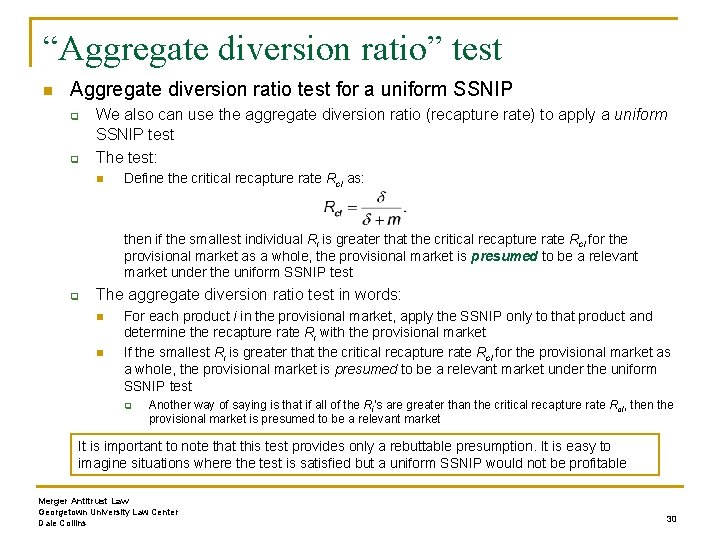

“Aggregate diversion ratio” test n Aggregate diversion ratio test for a uniform SSNIP q q We also can use the aggregate diversion ratio (recapture rate) to apply a uniform SSNIP test The test: n Define the critical recapture rate Rcl as: then if the smallest individual Ri is greater that the critical recapture rate Rcl for the provisional market as a whole, the provisional market is presumed to be a relevant market under the uniform SSNIP test q The aggregate diversion ratio test in words: n n For each product i in the provisional market, apply the SSNIP only to that product and determine the recapture rate Ri with the provisional market If the smallest Ri is greater that the critical recapture rate Rcl for the provisional market as a whole, the provisional market is presumed to be a relevant market under the uniform SSNIP test q Another way of saying is that if all of the Ri’s are greater than the critical recapture rate Rcl, then the provisional market is presumed to be a relevant market It is important to note that this test provides only a rebuttable presumption. It is easy to imagine situations where the test is satisfied but a uniform SSNIP would not be profitable Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 30

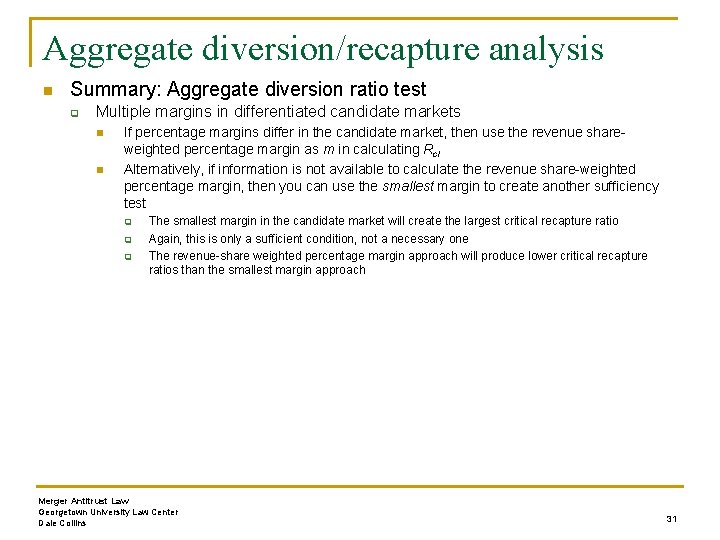

Aggregate diversion/recapture analysis n Summary: Aggregate diversion ratio test q Multiple margins in differentiated candidate markets n n If percentage margins differ in the candidate market, then use the revenue shareweighted percentage margin as m in calculating Rcl Alternatively, if information is not available to calculate the revenue share-weighted percentage margin, then you can use the smallest margin to create another sufficiency test q q q The smallest margin in the candidate market will create the largest critical recapture ratio Again, this is only a sufficient condition, not a necessary one The revenue-share weighted percentage margin approach will produce lower critical recapture ratios than the smallest margin approach Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 31

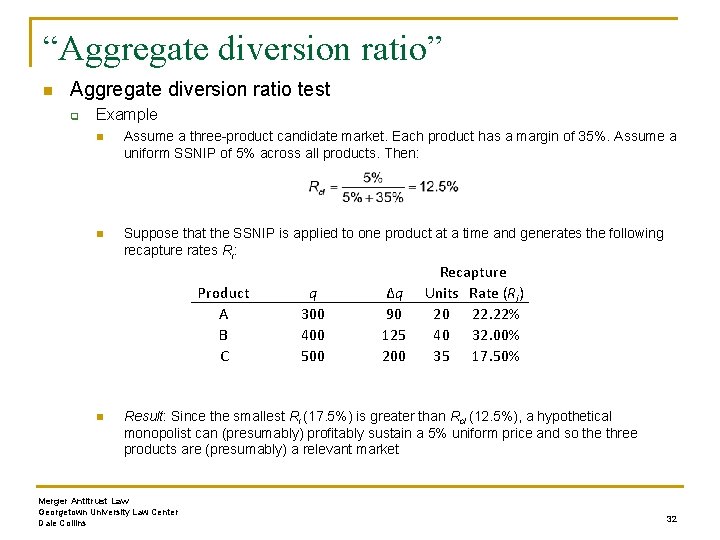

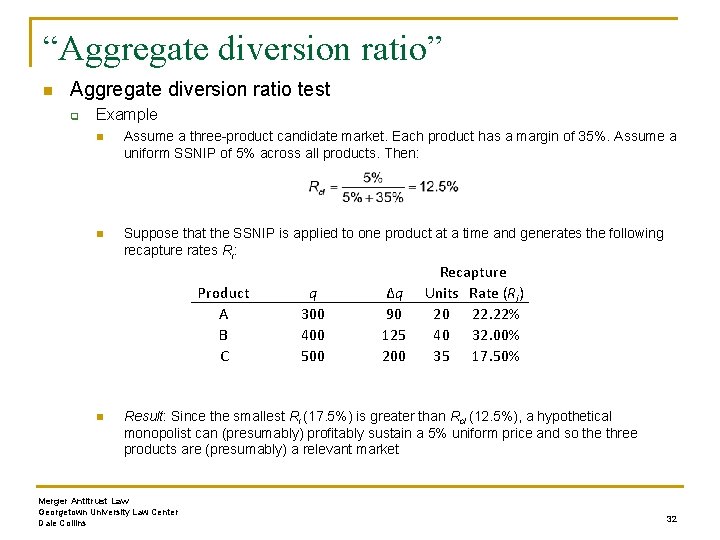

“Aggregate diversion ratio” n Aggregate diversion ratio test q Example n Assume a three-product candidate market. Each product has a margin of 35%. Assume a uniform SSNIP of 5% across all products. Then: n Suppose that the SSNIP is applied to one product at a time and generates the following recapture rates Ri: Product A B C n q 300 400 500 Δq 90 125 200 Recapture Units Rate (Ri) 20 22. 22% 40 32. 00% 35 17. 50% Result: Since the smallest Ri (17. 5%) is greater than Rcl (12. 5%), a hypothetical monopolist can (presumably) profitably sustain a 5% uniform price and so the three products are (presumably) a relevant market Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 32

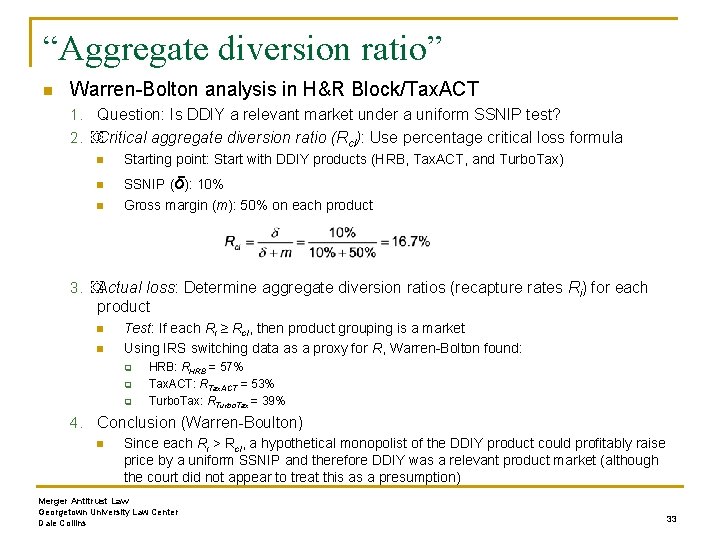

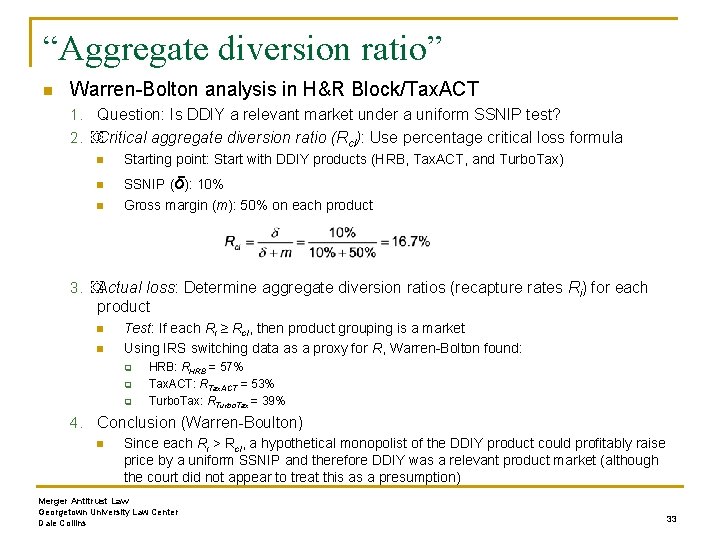

“Aggregate diversion ratio” n Warren-Bolton analysis in H&R Block/Tax. ACT 1. Question: Is DDIY a relevant market under a uniform SSNIP test? 2. Critical aggregate diversion ratio (Rcl): Use percentage critical loss formula n Starting point: Start with DDIY products (HRB, Tax. ACT, and Turbo. Tax) n SSNIP (δ): 10% n Gross margin (m): 50% on each product 3. Actual loss: Determine aggregate diversion ratios (recapture rates Ri) for each product n n Test: If each Ri ≥ Rcl, then product grouping is a market Using IRS switching data as a proxy for R, Warren-Bolton found: q q q HRB: RHRB = 57% Tax. ACT: RTax. ACT = 53% Turbo. Tax: RTurbo. Tax = 39% 4. Conclusion (Warren-Boulton) n Since each Ri > Rcl, a hypothetical monopolist of the DDIY product could profitably raise price by a uniform SSNIP and therefore DDIY was a relevant product market (although the court did not appear to treat this as a presumption) Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 33

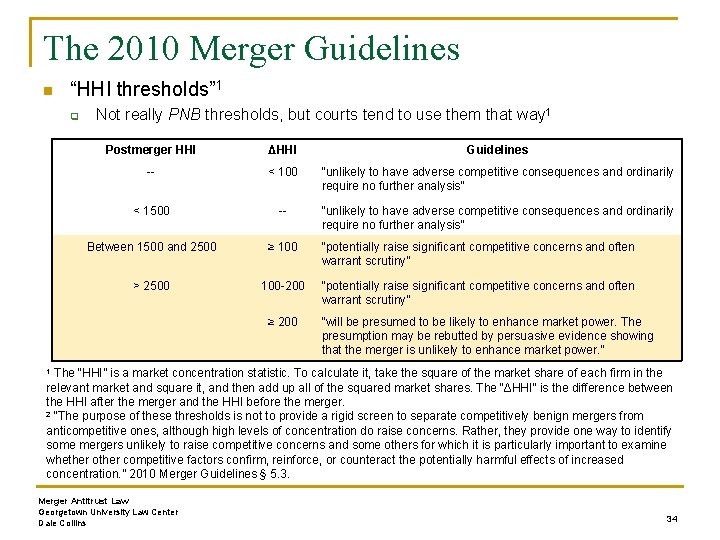

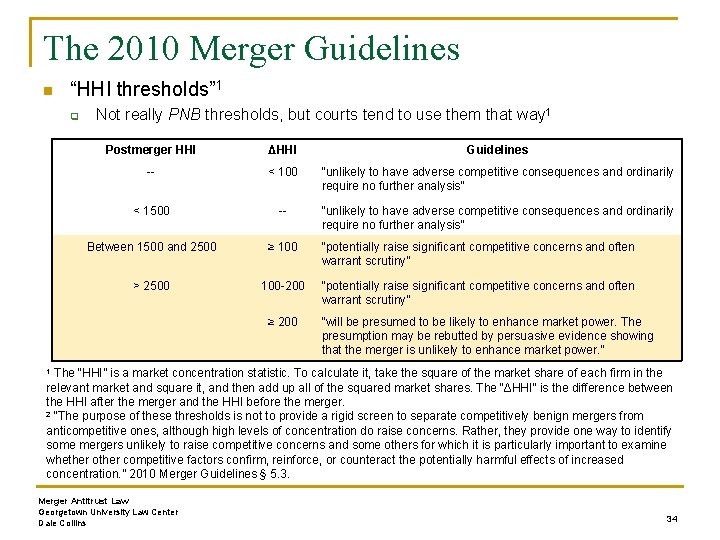

The 2010 Merger Guidelines n “HHI thresholds” 1 q Not really PNB thresholds, but courts tend to use them that way 1 Postmerger HHI ΔHHI Guidelines -- < 100 “unlikely to have adverse competitive consequences and ordinarily require no further analysis” < 1500 -- “unlikely to have adverse competitive consequences and ordinarily require no further analysis” Between 1500 and 2500 ≥ 100 “potentially raise significant competitive concerns and often warrant scrutiny” > 2500 100 -200 “potentially raise significant competitive concerns and often warrant scrutiny” ≥ 200 “will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power. The presumption may be rebutted by persuasive evidence showing that the merger is unlikely to enhance market power. ” 1 The “HHI” is a market concentration statistic. To calculate it, take the square of the market share of each firm in the relevant market and square it, and then add up all of the squared market shares. The “ΔHHI” is the difference between the HHI after the merger and the HHI before the merger. 2 “The purpose of these thresholds is not to provide a rigid screen to separate competitively benign mergers from anticompetitive ones, although high levels of concentration do raise concerns. Rather, they provide one way to identify some mergers unlikely to raise competitive concerns and some others for which it is particularly important to examine whether other competitive factors confirm, reinforce, or counteract the potentially harmful effects of increased concentration. ” 2010 Merger Guidelines § 5. 3. Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 34

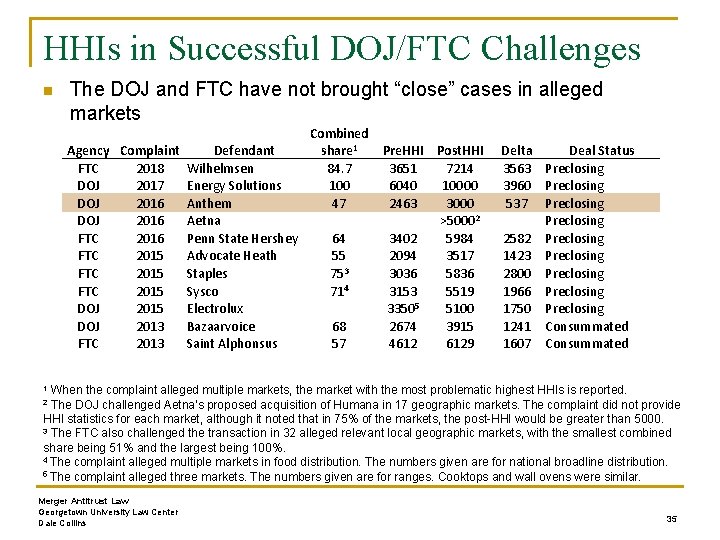

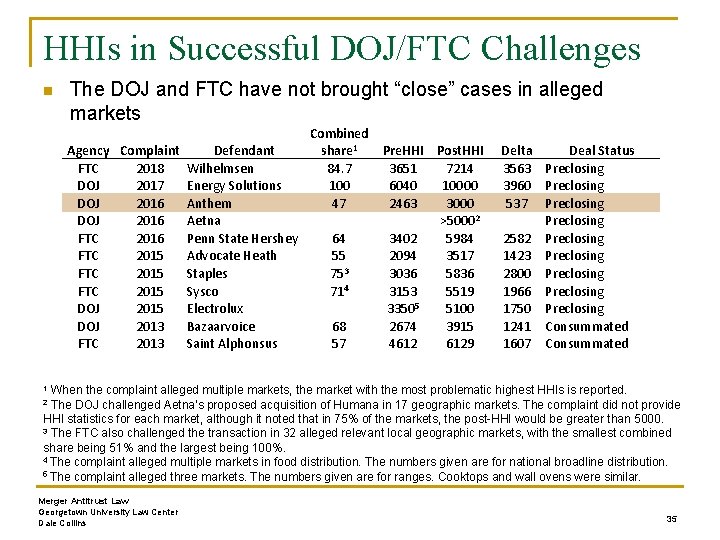

HHIs in Successful DOJ/FTC Challenges n The DOJ and FTC have not brought “close” cases in alleged markets Combined Agency Complaint Defendant share 1 Pre. HHI Post. HHI FTC 2018 Wilhelmsen 84. 7 3651 7214 DOJ 2017 Energy Solutions 100 6040 10000 DOJ 2016 Anthem 47 2463 3000 DOJ 2016 Aetna >50002 FTC 2016 Penn State Hershey 64 3402 5984 FTC 2015 Advocate Heath 55 2094 3517 3 FTC 2015 Staples 75 3036 5836 4 FTC 2015 Sysco 71 3153 5519 DOJ 2015 Electrolux 33505 5100 DOJ 2013 Bazaarvoice 68 2674 3915 FTC 2013 Saint Alphonsus 57 4612 6129 Delta Deal Status 3563 Preclosing 3960 Preclosing 537 Preclosing 2582 Preclosing 1423 Preclosing 2800 Preclosing 1966 Preclosing 1750 Preclosing 1241 Consummated 1607 Consummated 1 When the complaint alleged multiple markets, the market with the most problematic highest HHIs is reported. 2 The DOJ challenged Aetna’s proposed acquisition of Humana in 17 geographic markets. The complaint did not provide HHI statistics for each market, although it noted that in 75% of the markets, the post-HHI would be greater than 5000. 3 The FTC also challenged the transaction in 32 alleged relevant local geographic markets, with the smallest combined share being 51% and the largest being 100%. 4 The complaint alleged multiple markets in food distribution. The numbers given are for national broadline distribution. 5 The complaint alleged three markets. The numbers given are for ranges. Cooktops and wall ovens were similar. Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 35

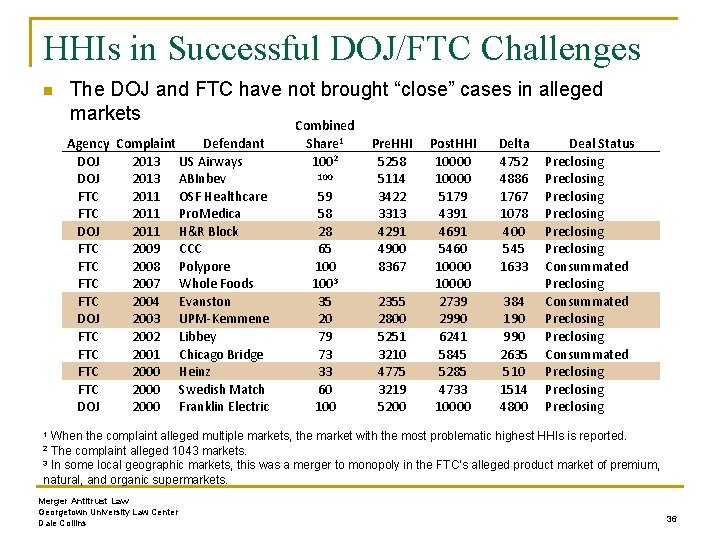

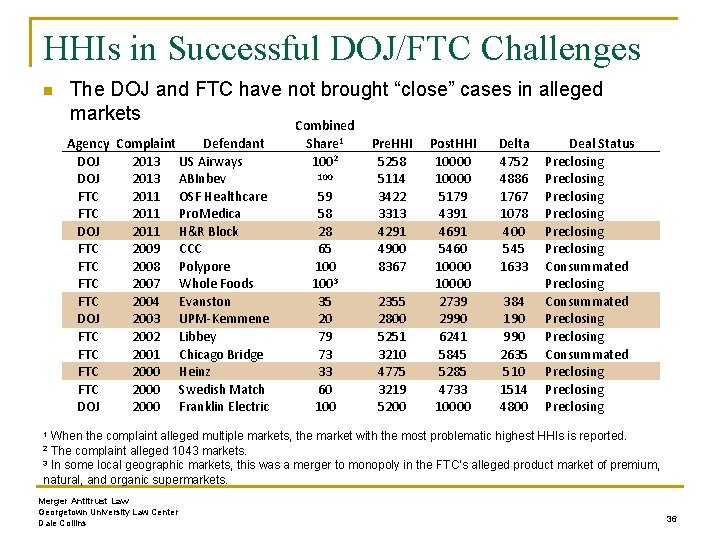

HHIs in Successful DOJ/FTC Challenges n The DOJ and FTC have not brought “close” cases in alleged markets Combined Agency Complaint Defendant DOJ 2013 US Airways DOJ 2013 ABInbev FTC 2011 OSF Healthcare FTC 2011 Pro. Medica DOJ 2011 H&R Block FTC 2009 CCC FTC 2008 Polypore FTC 2007 Whole Foods FTC 2004 Evanston DOJ 2003 UPM-Kemmene FTC 2002 Libbey FTC 2001 Chicago Bridge FTC 2000 Heinz FTC 2000 Swedish Match DOJ 2000 Franklin Electric Share 1 1002 100 59 58 28 65 1003 35 20 79 73 33 60 100 Pre. HHI 5258 5114 3422 3313 4291 4900 8367 2355 2800 5251 3210 4775 3219 5200 Post. HHI 10000 5179 4391 4691 5460 10000 2739 2990 6241 5845 5285 4733 10000 Delta 4752 4886 1767 1078 400 545 1633 384 190 990 2635 510 1514 4800 Deal Status Preclosing Preclosing Consummated Preclosing Preclosing 1 When the complaint alleged multiple markets, the market with the most problematic highest HHIs is reported. 2 The complaint alleged 1043 markets. 3 In some local geographic markets, this was a merger to monopoly in the FTC’s alleged product market of premium, natural, and organic supermarkets. Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 36

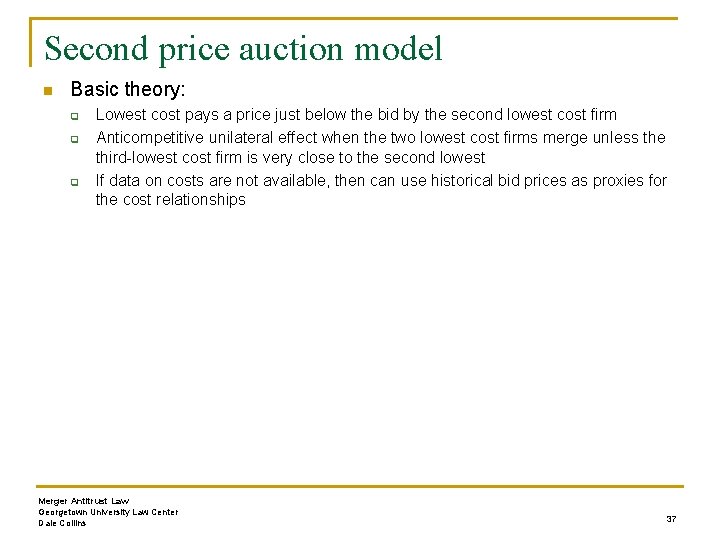

Second price auction model n Basic theory: q q q Lowest cost pays a price just below the bid by the second lowest cost firm Anticompetitive unilateral effect when the two lowest cost firms merge unless the third-lowest cost firm is very close to the second lowest If data on costs are not available, then can use historical bid prices as proxies for the cost relationships Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 37

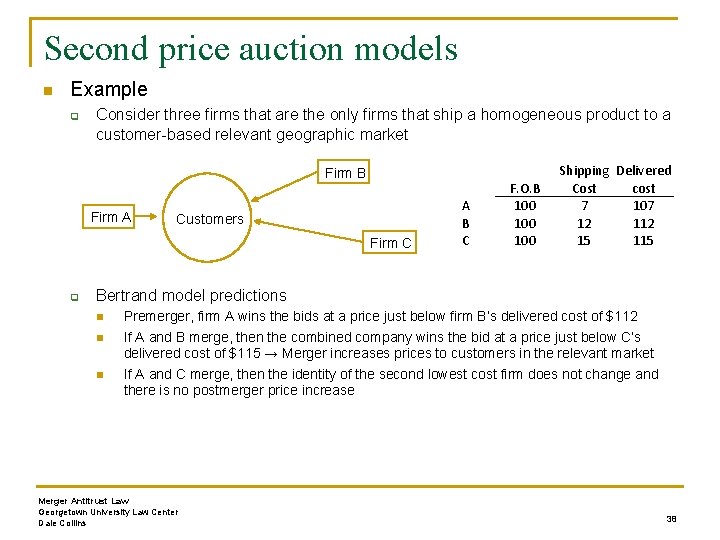

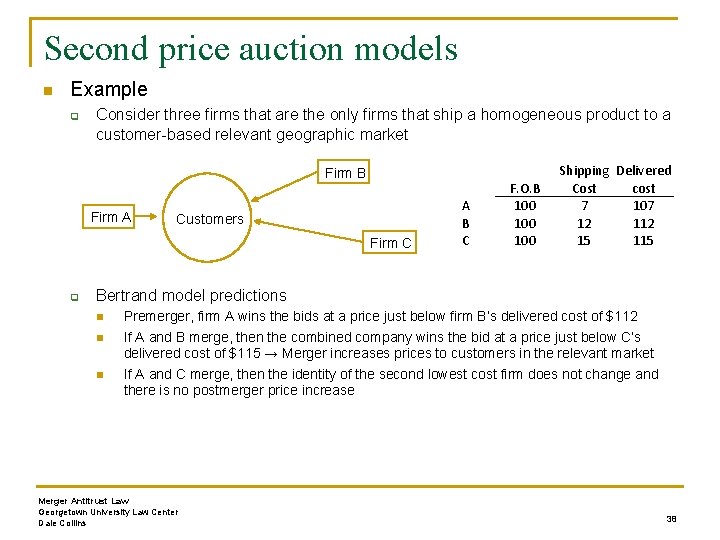

Second price auction models n Example q Consider three firms that are the only firms that ship a homogeneous product to a customer-based relevant geographic market Firm B Firm A Customers Firm C q A B C F. O. B 100 100 Shipping Delivered Cost cost 7 107 12 15 115 Bertrand model predictions n n n Premerger, firm A wins the bids at a price just below firm B’s delivered cost of $112 If A and B merge, then the combined company wins the bid at a price just below C’s delivered cost of $115 → Merger increases prices to customers in the relevant market If A and C merge, then the identity of the second lowest cost firm does not change and there is no postmerger price increase Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 38

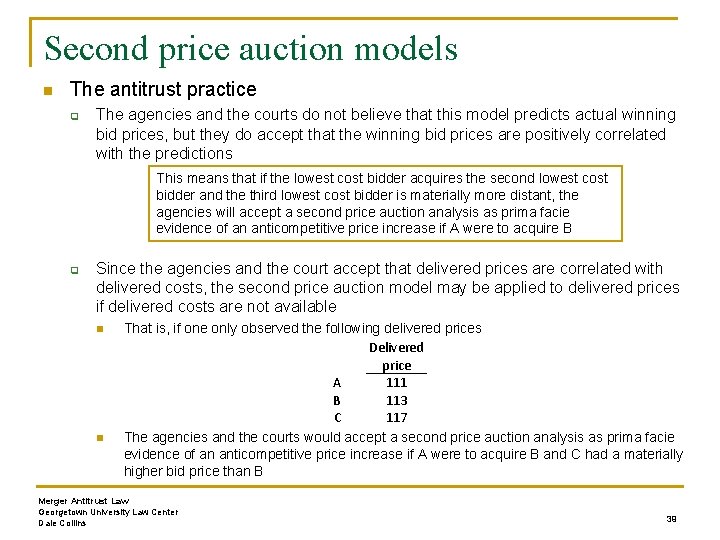

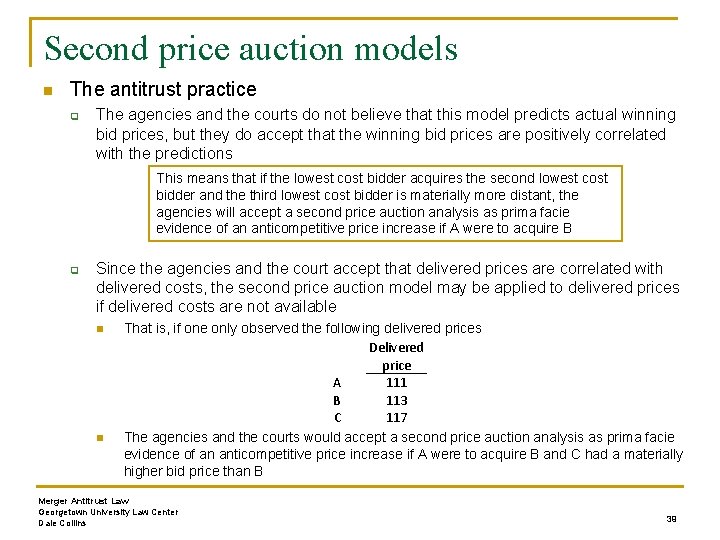

Second price auction models n The antitrust practice q The agencies and the courts do not believe that this model predicts actual winning bid prices, but they do accept that the winning bid prices are positively correlated with the predictions This means that if the lowest cost bidder acquires the second lowest cost bidder and the third lowest cost bidder is materially more distant, the agencies will accept a second price auction analysis as prima facie evidence of an anticompetitive price increase if A were to acquire B q Since the agencies and the court accept that delivered prices are correlated with delivered costs, the second price auction model may be applied to delivered prices if delivered costs are not available n n That is, if one only observed the following delivered prices Delivered price A 111 B 113 C 117 The agencies and the courts would accept a second price auction analysis as prima facie evidence of an anticompetitive price increase if A were to acquire B and C had a materially higher bid price than B Merger Antitrust Law Georgetown University Law Center Dale Collins 39