Language Arts and Chinese for Specific Purposes ChuRen

![Qualia Structure from Pustejovsky’s Generative Lexicon Qualia Structure accounts for regular polysemy [following Apresjan] Qualia Structure from Pustejovsky’s Generative Lexicon Qualia Structure accounts for regular polysemy [following Apresjan]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f394f31c5d2071aac3cd5a47ecdb3b5b/image-7.jpg)

- Slides: 53

Language Arts and Chinese for Specific Purposes Chu-Ren Huang 黃居仁 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University https: //www. researchgate. net/profile/Chu-Ren_Huang/ https: //scholar. google. com. hk/citations? user=z. P 4 DNqg. AAAAJ&hl=en 31 March 2018, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa

Outline The challenges of lexical meaning variations according to specific purposes 特定/特殊用途語言中的詞義變化問題 The name of the rose A Telic (purpose-driven) approach to meaning (for specific purposes) The Specific Purposes of Chinese 漢語的特定用途 Language in use, in context, in vivo Linguistic Tools for Specific Purposes Chinese Language Art and Language for Specific Purposes

The challenges of lexical meaning variations according to specific purposes 特定/特殊用途語言中的詞義變化問題 A rose by any other name would smell as sweet. -Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare Yet, do we know how many different things the term ‘rose’ refer to? How about ‘an apple…’, ‘a rice…’, ‘a lemongrass…’

A rose by any other name 玫瑰的芳名 http: //www. image-net. org/search? q=rose

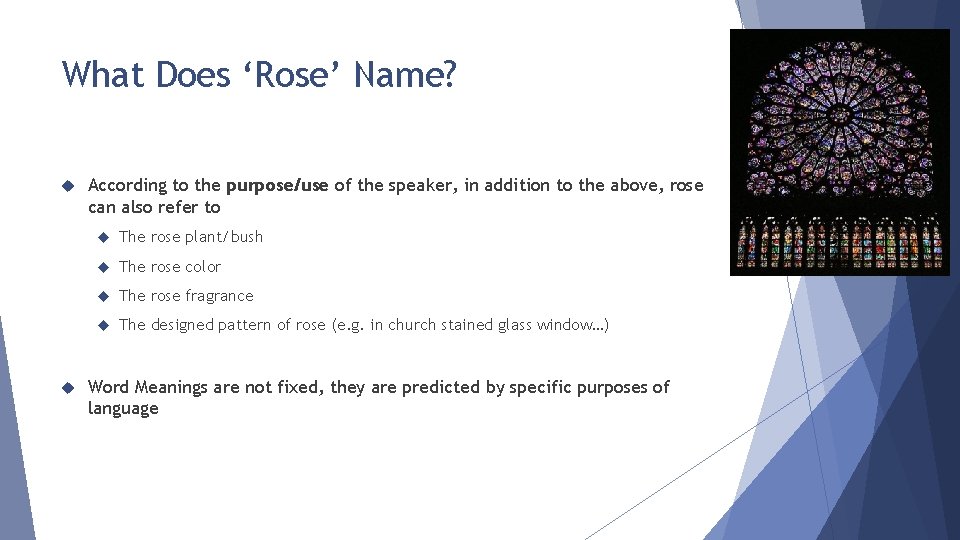

What Does ‘Rose’ Name? According to the purpose/use of the speaker, in addition to the above, rose can also refer to The rose plant/bush The rose color The rose fragrance The designed pattern of rose (e. g. in church stained glass window…) Word Meanings are not fixed, they are predicted by specific purposes of language

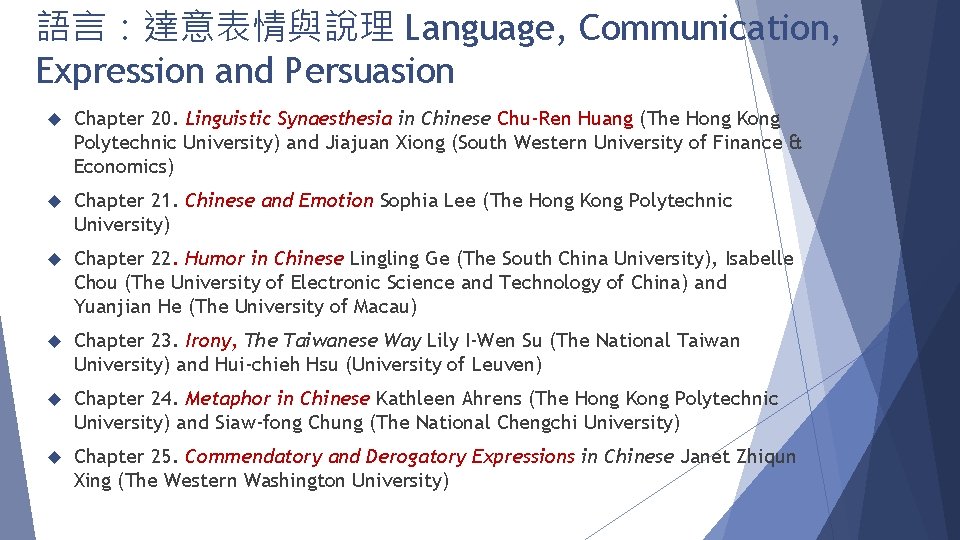

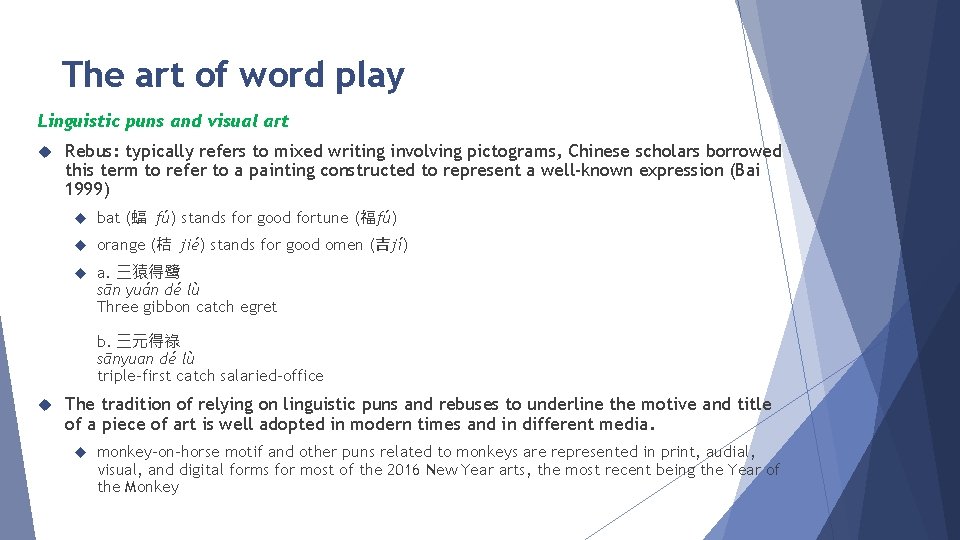

Aristotle’s Qualia: Four Causes As four aspects of knowledge/explanation The material cause: e. g. , the bronze of a statue. The formal cause: e. g. , the shape of a statue. The efficient cause: “the primary source of the change or rest”, e. g. , the artisan, the art of bronze-casting the statue, The final cause: “the end, that for the sake of which a thing is done”, telos The ‘Purpose’ We think we do not have knowledge of a thing until we have grasped its why, that is to say, its cause (Physics. 194 b 17 -20). -Falcon, Andrea, "Aristotle on Causality", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy http: //plato. stanford. edu/archives/fall 2008/entries/aristotle-causality/ Poly. U-FH Lecture Series 15 May 2009

![Qualia Structure from Pustejovskys Generative Lexicon Qualia Structure accounts for regular polysemy following Apresjan Qualia Structure from Pustejovsky’s Generative Lexicon Qualia Structure accounts for regular polysemy [following Apresjan]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/f394f31c5d2071aac3cd5a47ecdb3b5b/image-7.jpg)

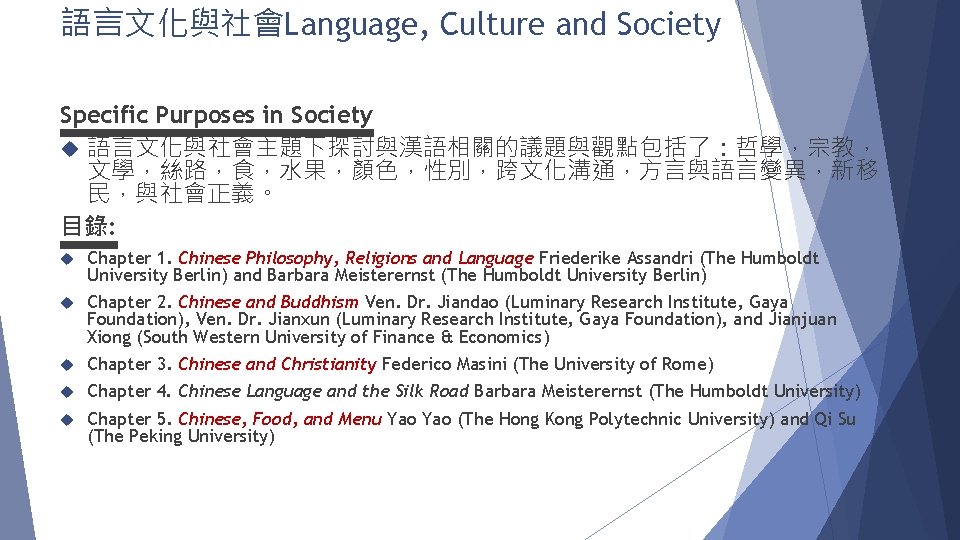

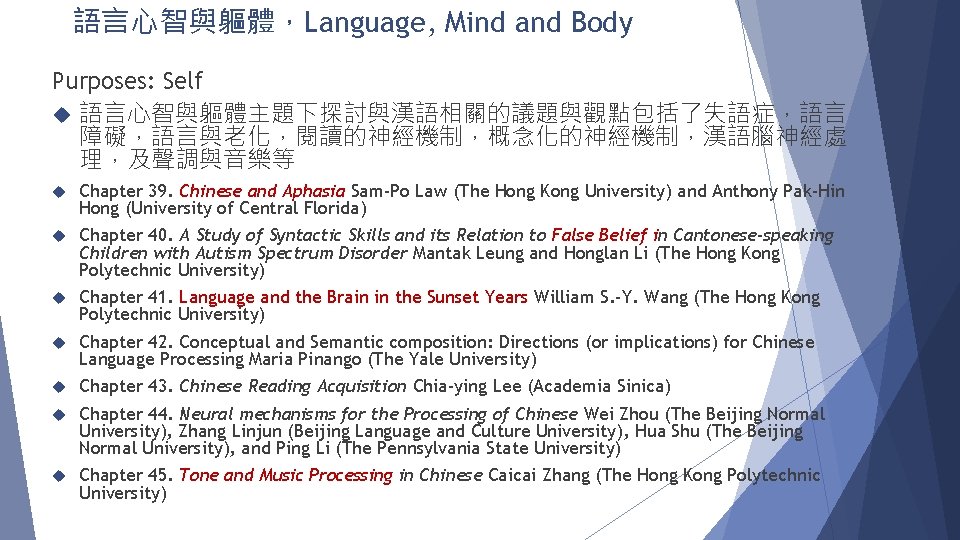

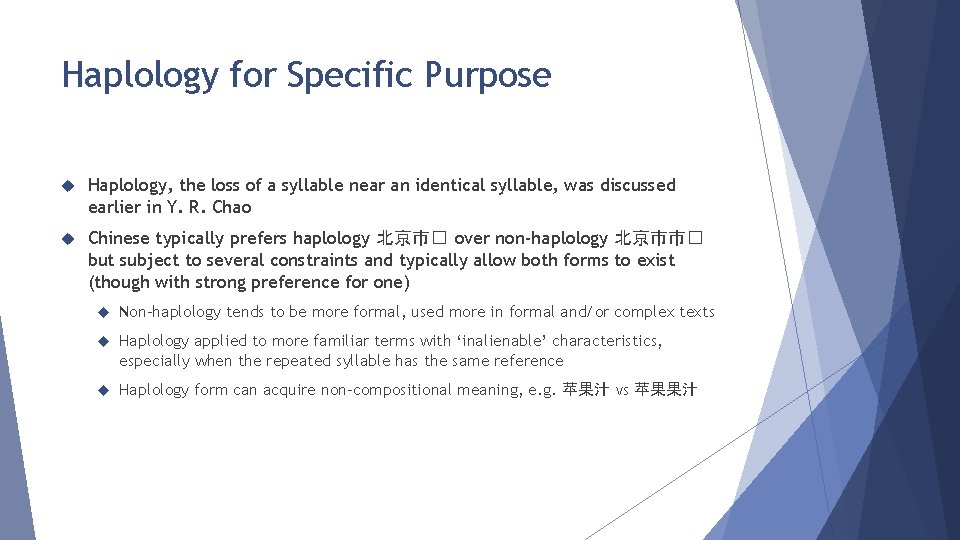

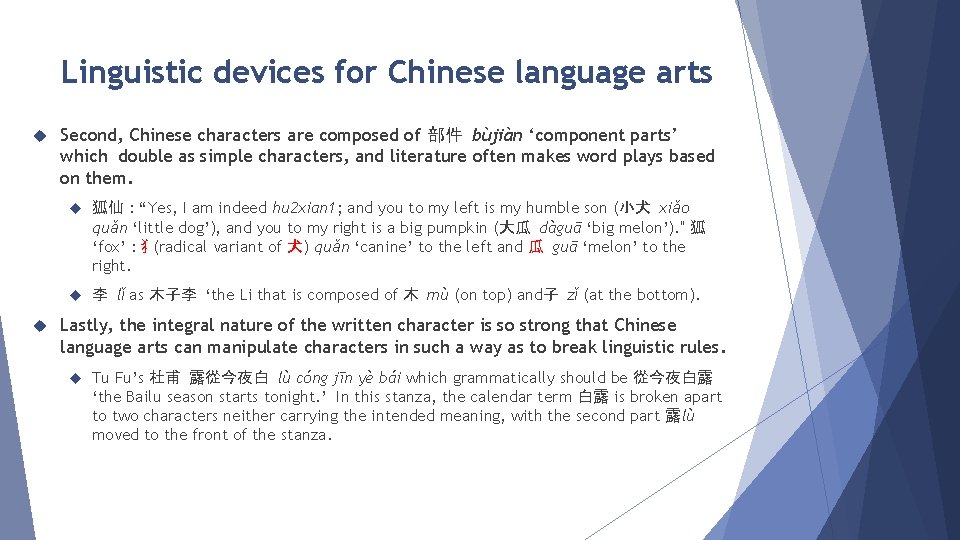

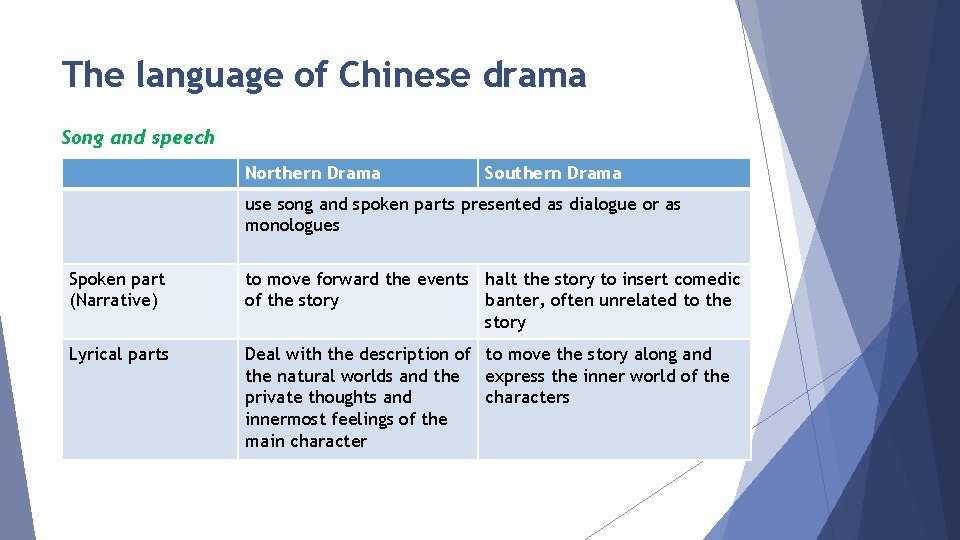

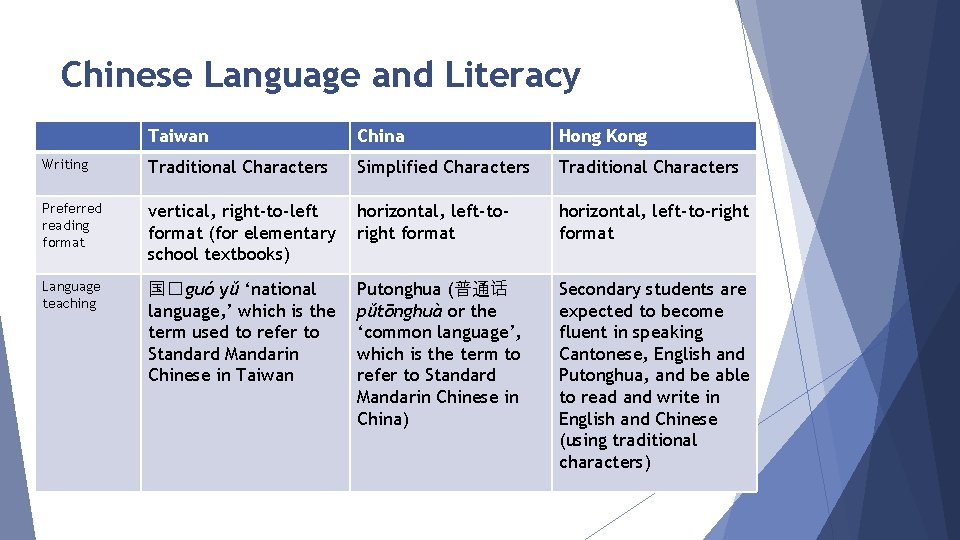

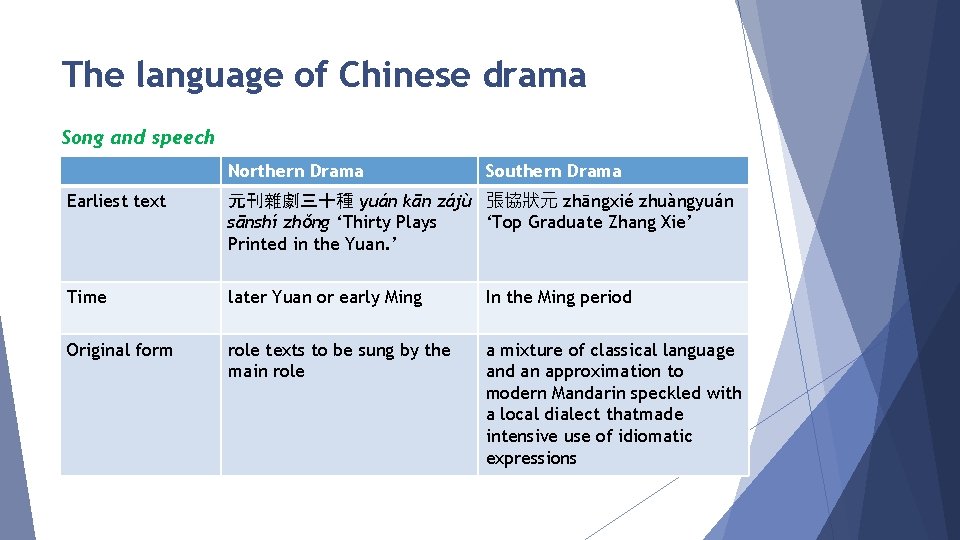

Qualia Structure from Pustejovsky’s Generative Lexicon Qualia Structure accounts for regular polysemy [following Apresjan] Formal: a good book, a red book Constitutive: a 650 pp. book, a 10 volume book, a ten chapter book Agentive: 線/膠裝書`thread or glue-bound book’, a difficult book (to write), Telic: an interesting book, I enjoyed the book Which meaning will a reader, a publisher, a writer, a scholar, a interior designer, a bookstore owner/clerk, a truck driver etc. refer to? By specific purpose, by context… Poly. U-FH Lecture Series 15 May 2009

A Telic/Purpose-driven Approach to Lexicon and Meaning Word meanings are not atoms but are complex bundle of related knowledge (qualia) that can be specified by the purposes. Tools: Word. Net Princeton Word. Net (WN) https: //wordnet. princeton. edu/ Sinica BOW: Academia Sinica Bilingual Ontological Wordnet中央研究院中英雙語知 識本體詞網. http: //bow. ling. sinica. edu. tw/ Chinese Wordnet 中文詞網 http: //cwn. ling. sinica. edu. tw Image. Net http: //www. image-net. org WN based collection of images References Pustejovsky, James. 1991. The generative lexicon. Computational linguistics 17. 4: 409 -441. Song, Zuoyan宋作豔 and Chu-Ren Huang黃居仁. 編著. In Press. 2018. Generative Lexicon Studies in Chinese生成辭彙理論與漢語研究. 北京: 商務印書館.

The Specific Purposes of Chinese 漢語的特定用途 What are the specific purposes of language? Are Chinese for Specific Purposes limited to Chinese in specific domains or professions? Business as purpose? Or to sell, to (persuade) to make deals? To emote To lie To persuade To describe food, fruit? products? To describe Time, location, senses? Scientific theories? Philosophy?

The Specific Purposes of Chinese II 漢語的特定用途 We saw earlier that word meanings are underspecified complex concepts that get specified by different purposes. It suggests that in fact to understand language as well as how language is used, we need to be able to understand the specific purposes of the language.

Chinese Language in Action, in Context, and in Vivo 行動中,脈絡中,活生生的漢語 Huang, Chu-Ren, Barbara Meisterernst, and Zhuo Jing-Schmidt. (Eds. ). 2019 (To Appear). Routledge Handbook on Chinese Applied Linguistics. London: Routledge.

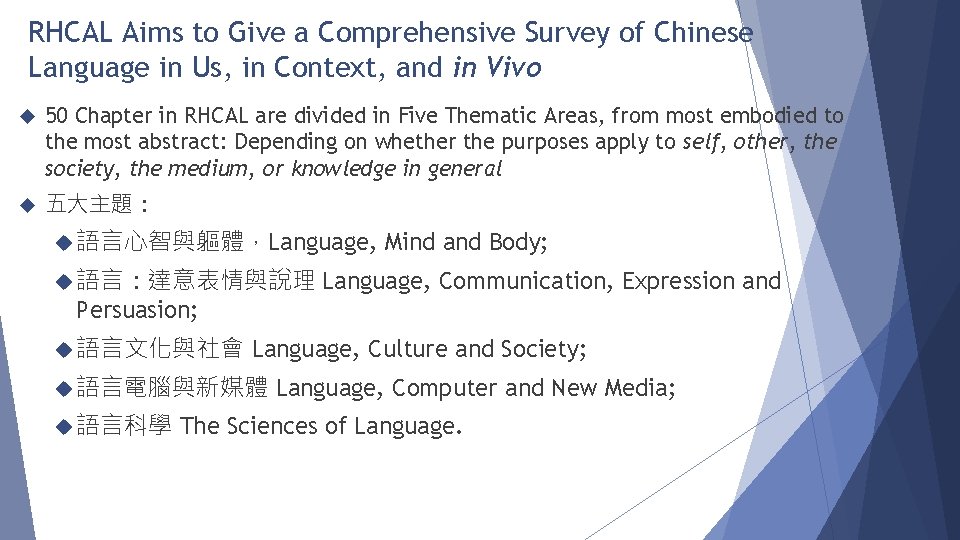

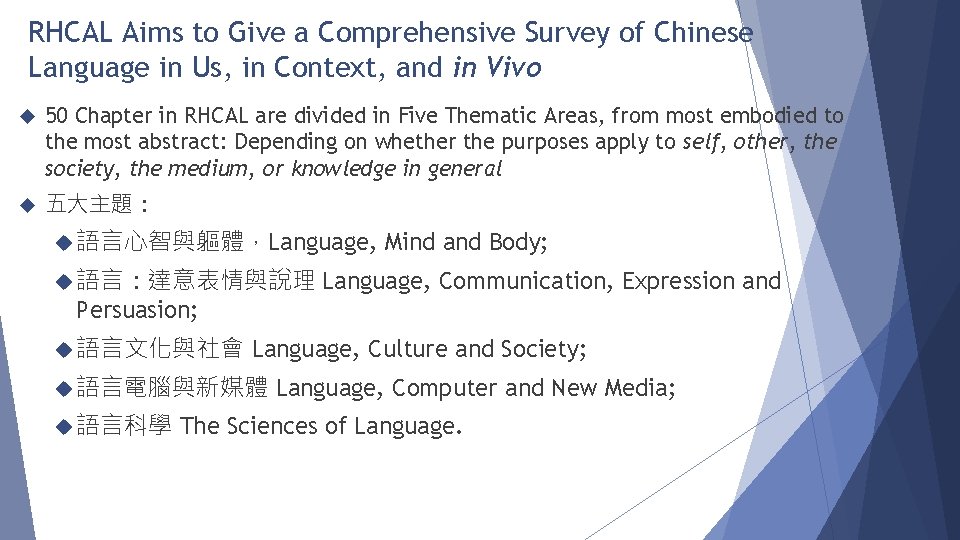

RHCAL Aims to Give a Comprehensive Survey of Chinese Language in Us, in Context, and in Vivo 50 Chapter in RHCAL are divided in Five Thematic Areas, from most embodied to the most abstract: Depending on whether the purposes apply to self, other, the society, the medium, or knowledge in general 五大主題: 語言心智與軀體,Language, 語言:達意表情與說理 Mind and Body; Language, Communication, Expression and Persuasion; 語言文化與社會 Language, Culture and Society; 語言電腦與新媒體 語言科學 Language, Computer and New Media; The Sciences of Language.

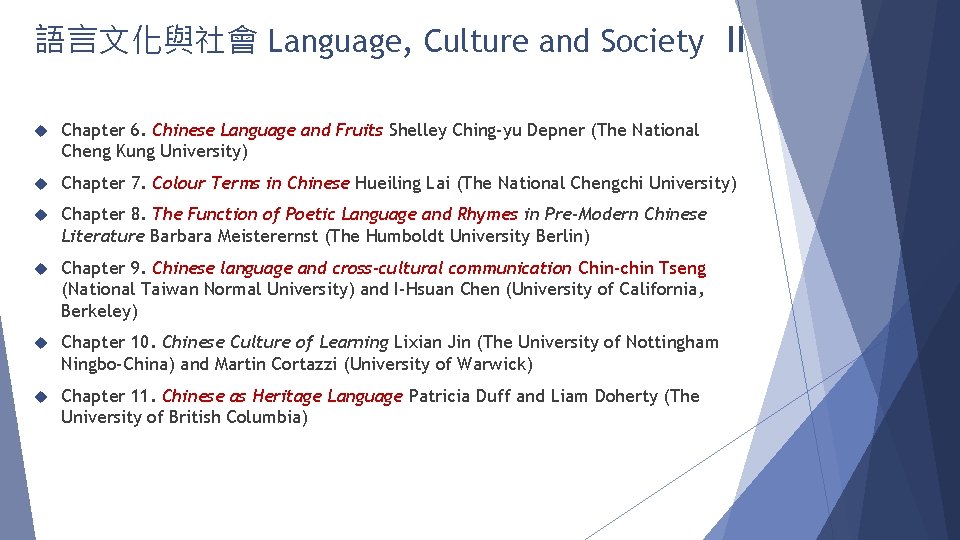

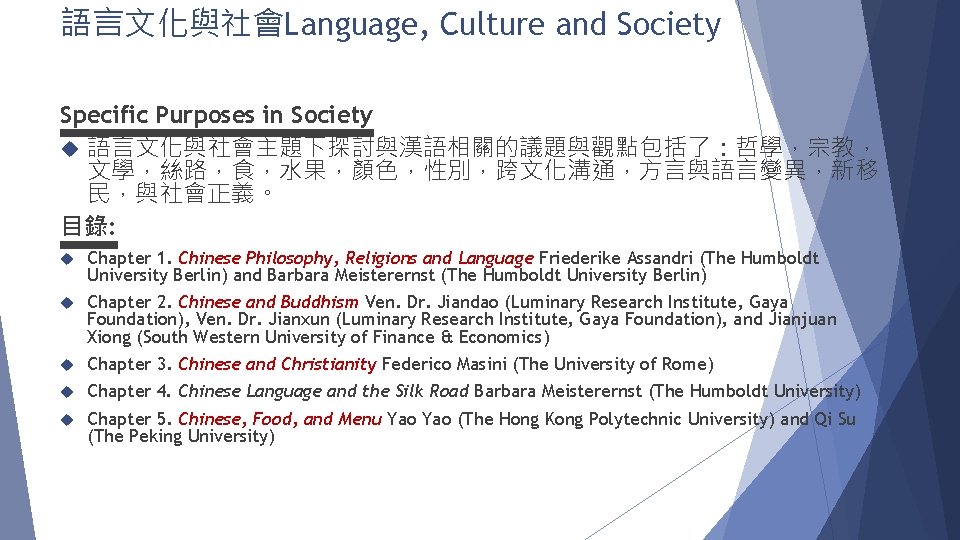

語言文化與社會Language, Culture and Society Specific Purposes in Society 語言文化與社會主題下探討與漢語相關的議題與觀點包括了:哲學,宗教, 文學,絲路,食,水果,顏色,性別,跨文化溝通,方言與語言變異,新移 民,與社會正義。 目錄: Chapter 1. Chinese Philosophy, Religions and Language Friederike Assandri (The Humboldt University Berlin) and Barbara Meisterernst (The Humboldt University Berlin) Chapter 2. Chinese and Buddhism Ven. Dr. Jiandao (Luminary Research Institute, Gaya Foundation), Ven. Dr. Jianxun (Luminary Research Institute, Gaya Foundation), and Jianjuan Xiong (South Western University of Finance & Economics) Chapter 3. Chinese and Christianity Federico Masini (The University of Rome) Chapter 4. Chinese Language and the Silk Road Barbara Meisterernst (The Humboldt University) Chapter 5. Chinese, Food, and Menu Yao (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Qi Su (The Peking University)

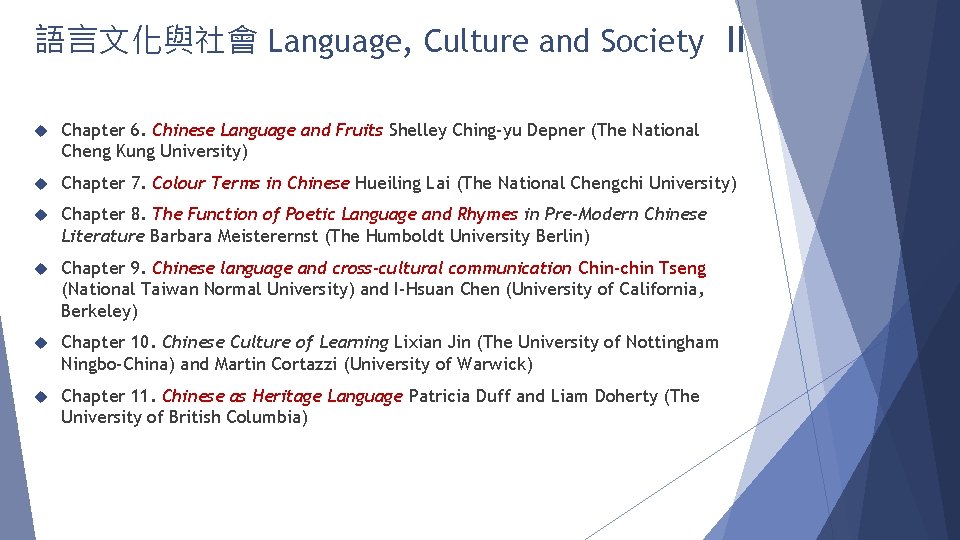

語言文化與社會 Language, Culture and Society II Chapter 6. Chinese Language and Fruits Shelley Ching-yu Depner (The National Cheng Kung University) Chapter 7. Colour Terms in Chinese Hueiling Lai (The National Chengchi University) Chapter 8. The Function of Poetic Language and Rhymes in Pre-Modern Chinese Literature Barbara Meisterernst (The Humboldt University Berlin) Chapter 9. Chinese language and cross-cultural communication Chin-chin Tseng (National Taiwan Normal University) and I-Hsuan Chen (University of California, Berkeley) Chapter 10. Chinese Culture of Learning Lixian Jin (The University of Nottingham Ningbo-China) and Martin Cortazzi (University of Warwick) Chapter 11. Chinese as Heritage Language Patricia Duff and Liam Doherty (The University of British Columbia)

語言文化與社會 Language, Culture and Society III Chapter 12. Language and Gender Marjorie Chan and Yuhan Lin (The Ohio State University) Chapter 13. Varieties of Chinese: Dialects or Sinitic Languages Maria Kurpaska (The Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan) Chapter 14. Variations in World Chineses Jingxia Lin (The Nanyang Technological University), Dingxu Shi (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), Jiang Menghan (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Chu-Ren Huang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 15. Chinese Language and New Immigrants Chin-chin Tseng (The National Taiwan Normal University) and Chen-Cheng Chun (The National Kaohsiung Normal University) Chapter 16. Chinese Language and Social Justice Susan D. Blum (The University of Notre Dame)

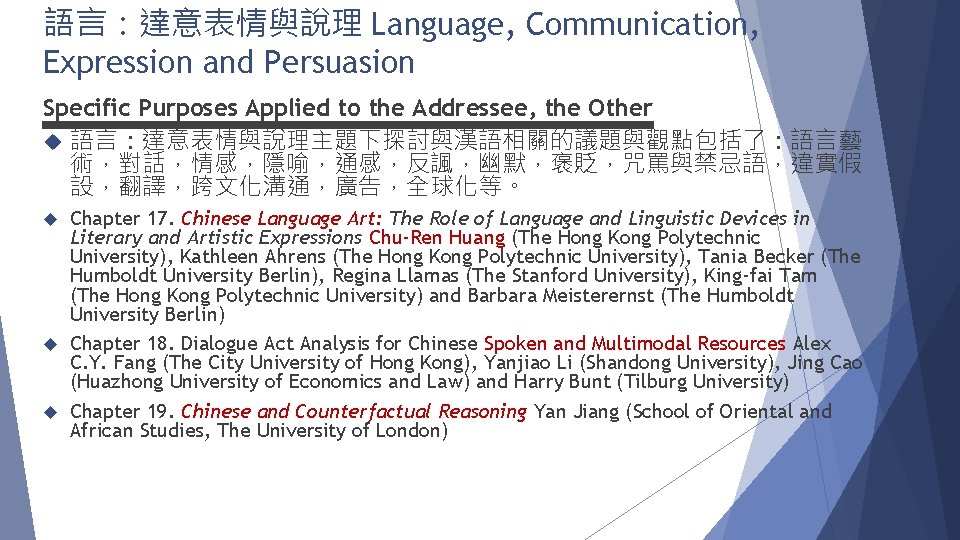

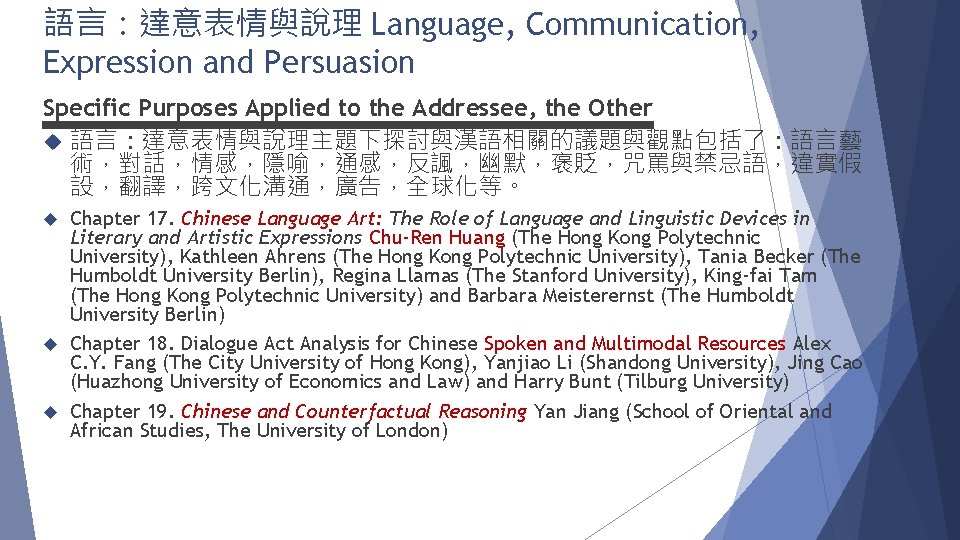

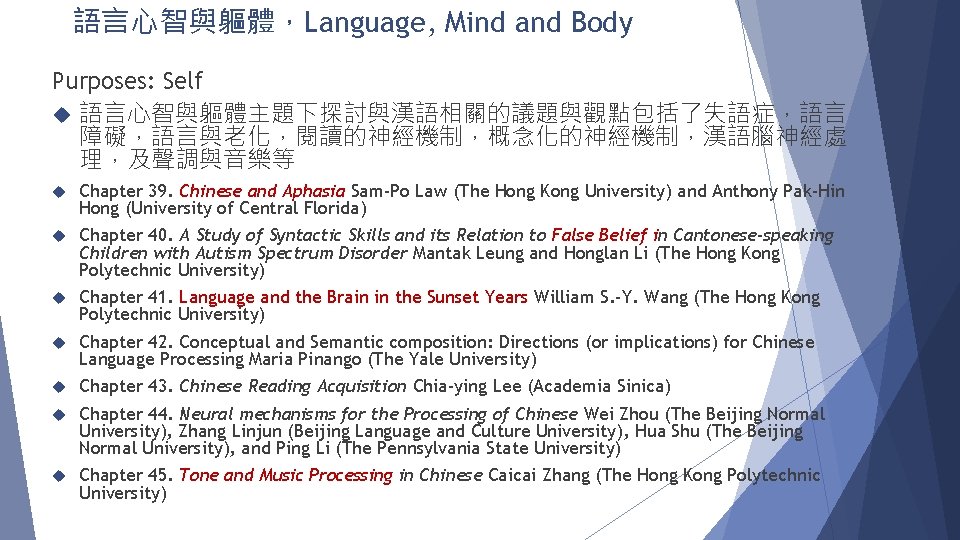

語言:達意表情與說理 Language, Communication, Expression and Persuasion Specific Purposes Applied to the Addressee, the Other 語言:達意表情與說理主題下探討與漢語相關的議題與觀點包括了:語言藝 術,對話,情感,隱喻,通感,反諷,幽默,褒貶,咒罵與禁忌語,違實假 設,翻譯,跨文化溝通,廣告,全球化等。 Chapter 17. Chinese Language Art: The Role of Language and Linguistic Devices in Literary and Artistic Expressions Chu-Ren Huang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), Kathleen Ahrens (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), Tania Becker (The Humboldt University Berlin), Regina Llamas (The Stanford University), King-fai Tam (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Barbara Meisterernst (The Humboldt University Berlin) Chapter 18. Dialogue Act Analysis for Chinese Spoken and Multimodal Resources Alex C. Y. Fang (The City University of Hong Kong), Yanjiao Li (Shandong University), Jing Cao (Huazhong University of Economics and Law) and Harry Bunt (Tilburg University) Chapter 19. Chinese and Counterfactual Reasoning Yan Jiang (School of Oriental and African Studies, The University of London)

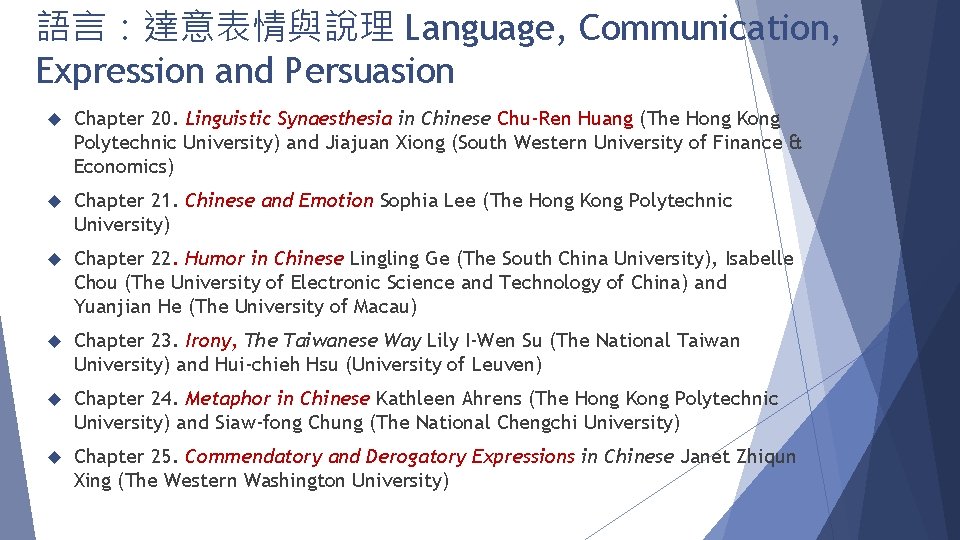

語言:達意表情與說理 Language, Communication, Expression and Persuasion Chapter 20. Linguistic Synaesthesia in Chinese Chu-Ren Huang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Jiajuan Xiong (South Western University of Finance & Economics) Chapter 21. Chinese and Emotion Sophia Lee (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 22. Humor in Chinese Lingling Ge (The South China University), Isabelle Chou (The University of Electronic Science and Technology of China) and Yuanjian He (The University of Macau) Chapter 23. Irony, The Taiwanese Way Lily I-Wen Su (The National Taiwan University) and Hui-chieh Hsu (University of Leuven) Chapter 24. Metaphor in Chinese Kathleen Ahrens (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Siaw-fong Chung (The National Chengchi University) Chapter 25. Commendatory and Derogatory Expressions in Chinese Janet Zhiqun Xing (The Western Washington University)

語言:達意表情與說理 Language, Communication, Expression and Persuasion II Chapter 26. Cursing, Taboo and Euphemism Zhuo Jing-Schmidt (The University of Oregon) Chapter 27. Chinese for specific purposes: A broader perspective Song Jiang and Haidan Wang (The University of Hawaii) Chapter 28. Chinese Translation in the Twenty First Century Chris C. C. Shei (The University of Swansea) Chapter 29. Chinese Language Advertisement Doreen Wu and Li Chaoyuan (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 30. Contemporary Chinese Discourse in Globalization Xu Shi (Hangzhou Normal University)

語言電腦與新媒體 Language, Computer and New Media Specific Purposes in terms of Medium 語言電腦與新媒體 主題下探討與漢語相關的議題與觀點包括了:漢字數字化, 語言資源,新詞語,信息可信度,語音合成,社交媒體,及科技對語言的影響 等 Chapter 31. Computer and Chinese Writing System Qin Lu (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 32. Digital Language Resources and NLP Tools Chu-Ren Huang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) and Nianwen Xue (The Brandeis University) Chapter 33. Information Quality: Linguistic cues and automatic judgments Qi Su (The Peking University) Chapter 34. Chinese Neologisms Zhuo Jing-Schmidt (The University of Oregon) and Shu-kai Hsieh (The National Taiwan University)

語言電腦與新媒體 Language, Computer and New Media II Chapter 35. Online Linguistic References: Advances, Applications, and Challenges Weidong Zhan (The Peking University), Xiaojing Bai (The Tsinghua University) Chapter 36. Speech recognition and text-to-speech synthesis Helen Meng, Lifa Sun, Shiyin Kang, and Xunying Liu (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) Chapter 37. Information Diffusion Prediction Based on Social Representation Learning with Group Influence Maggie Wenjie Li (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), Chengyao Chen (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University), and Zhitao Wang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 38. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology in the Chinese Language Life Jingwei Zhang (Nanjing University) and Daming Xu (The University of Macau)

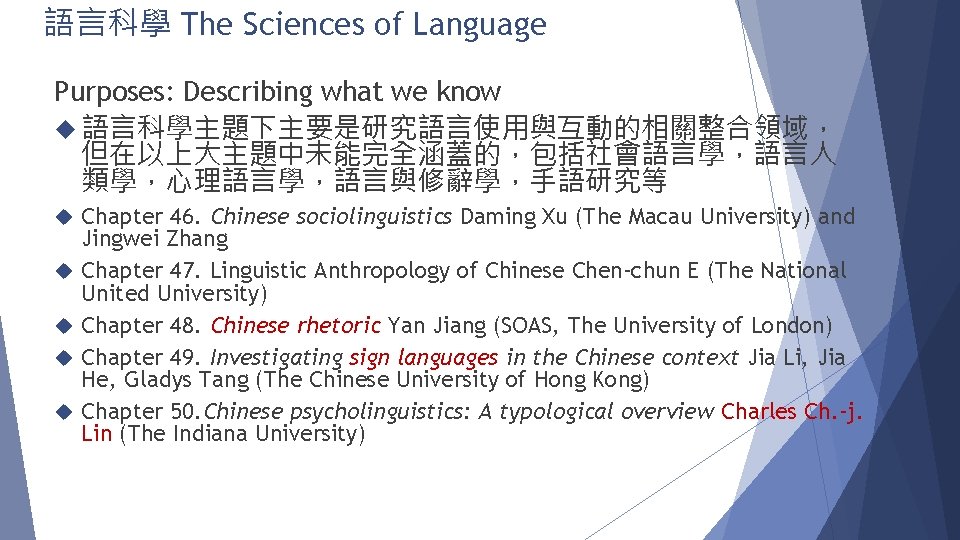

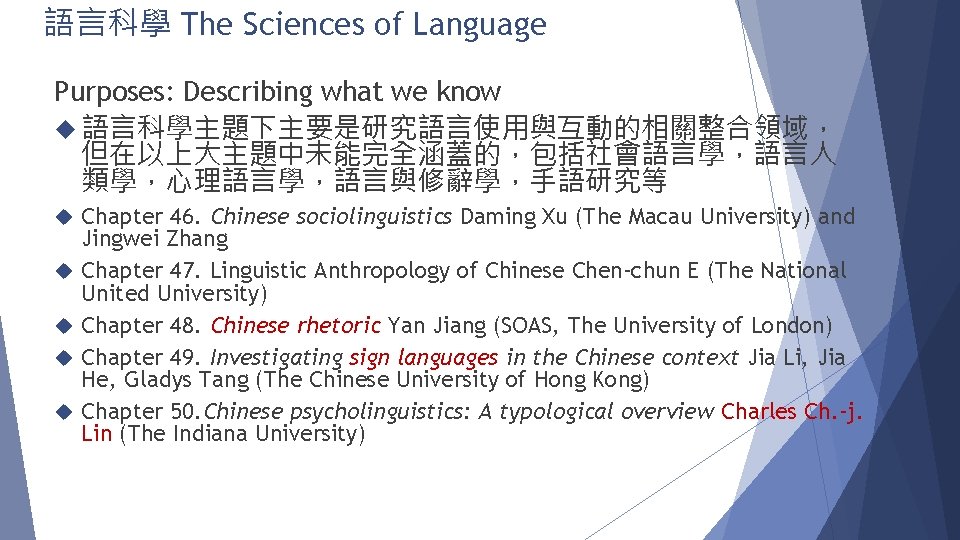

語言心智與軀體,Language, Mind and Body Purposes: Self 語言心智與軀體主題下探討與漢語相關的議題與觀點包括了失語症,語言 障礙,語言與老化,閱讀的神經機制,概念化的神經機制,漢語腦神經處 理,及聲調與音樂等 Chapter 39. Chinese and Aphasia Sam-Po Law (The Hong Kong University) and Anthony Pak-Hin Hong (University of Central Florida) Chapter 40. A Study of Syntactic Skills and its Relation to False Belief in Cantonese-speaking Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Mantak Leung and Honglan Li (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 41. Language and the Brain in the Sunset Years William S. -Y. Wang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University) Chapter 42. Conceptual and Semantic composition: Directions (or implications) for Chinese Language Processing Maria Pinango (The Yale University) Chapter 43. Chinese Reading Acquisition Chia-ying Lee (Academia Sinica) Chapter 44. Neural mechanisms for the Processing of Chinese Wei Zhou (The Beijing Normal University), Zhang Linjun (Beijing Language and Culture University), Hua Shu (The Beijing Normal University), and Ping Li (The Pennsylvania State University) Chapter 45. Tone and Music Processing in Chinese Caicai Zhang (The Hong Kong Polytechnic University)

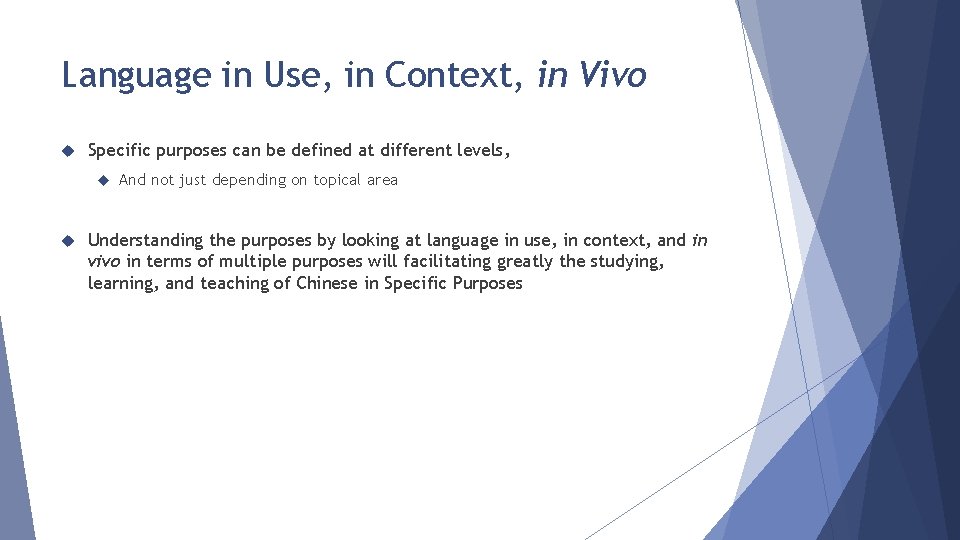

語言科學 The Sciences of Language Purposes: Describing what we know 語言科學主題下主要是研究語言使用與互動的相關整合領域, 但在以上大主題中未能完全涵蓋的,包括社會語言學,語言人 類學,心理語言學,語言與修辭學,手語研究等 Chapter 46. Chinese sociolinguistics Daming Xu (The Macau University) and Jingwei Zhang Chapter 47. Linguistic Anthropology of Chinese Chen-chun E (The National United University) Chapter 48. Chinese rhetoric Yan Jiang (SOAS, The University of London) Chapter 49. Investigating sign languages in the Chinese context Jia Li, Jia He, Gladys Tang (The Chinese University of Hong Kong) Chapter 50. Chinese psycholinguistics: A typological overview Charles Ch. -j. Lin (The Indiana University)

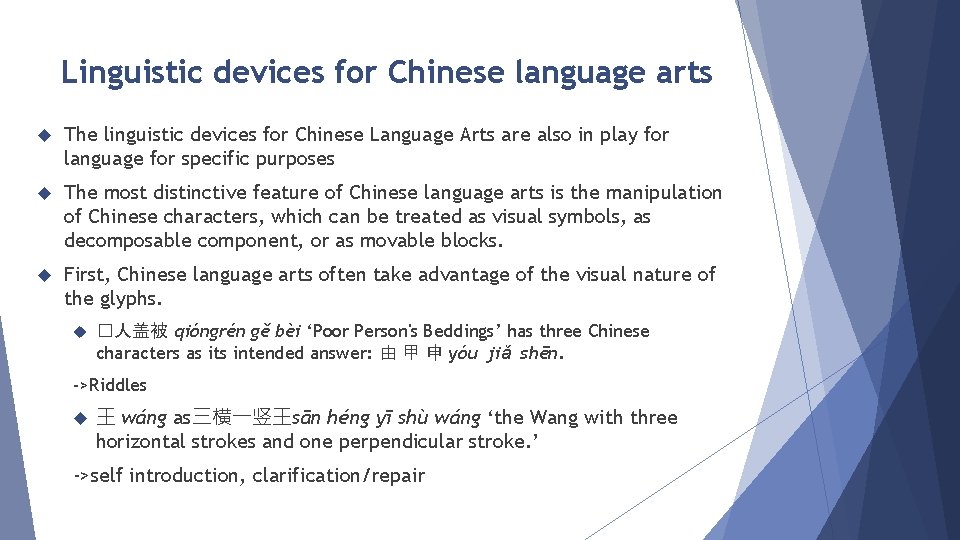

Language in Use, in Context, in Vivo Specific purposes can be defined at different levels, And not just depending on topical area Understanding the purposes by looking at language in use, in context, and in vivo in terms of multiple purposes will facilitating greatly the studying, learning, and teaching of Chinese in Specific Purposes

Linguistic devices for Chinese language arts The linguistic devices for Chinese Language Arts are also in play for language for specific purposes The most distinctive feature of Chinese language arts is the manipulation of Chinese characters, which can be treated as visual symbols, as decomposable component, or as movable blocks. First, Chinese language arts often take advantage of the visual nature of the glyphs. �人盖被 qióngrén gě bèi ‘Poor Person's Beddings’ has three Chinese characters as its intended answer: 由 甲 申 yóu jiǎ shēn. ->Riddles 王 wáng as三横一竖王sān héng yī shù wáng ‘the Wang with three horizontal strokes and one perpendicular stroke. ’ ->self introduction, clarification/repair

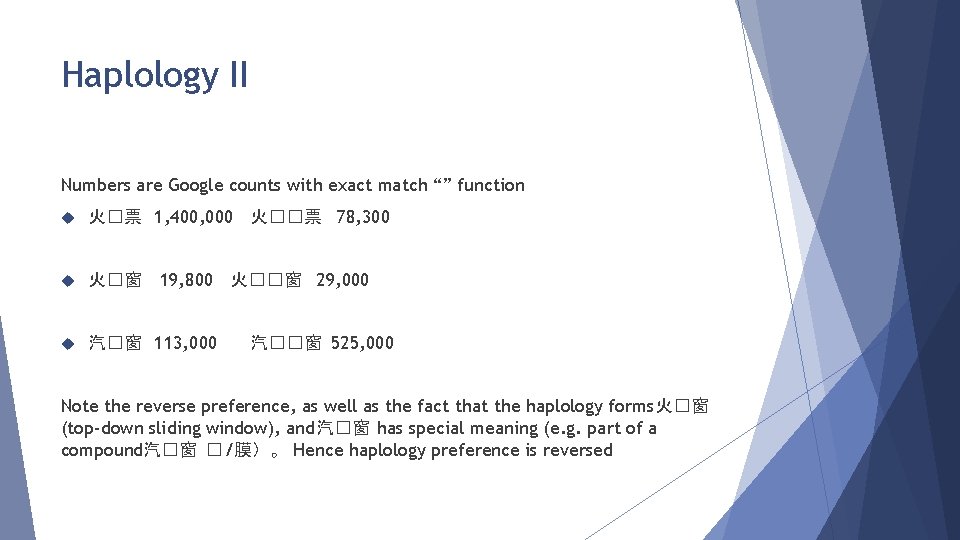

Haplology for Specific Purpose Haplology, the loss of a syllable near an identical syllable, was discussed earlier in Y. R. Chao Chinese typically prefers haplology 北京市� over non-haplology 北京市市� but subject to several constraints and typically allow both forms to exist (though with strong preference for one) Non-haplology tends to be more formal, used more in formal and/or complex texts Haplology applied to more familiar terms with ‘inalienable’ characteristics, especially when the repeated syllable has the same reference Haplology form can acquire non-compositional meaning, e. g. 苹果汁 vs 苹果果汁

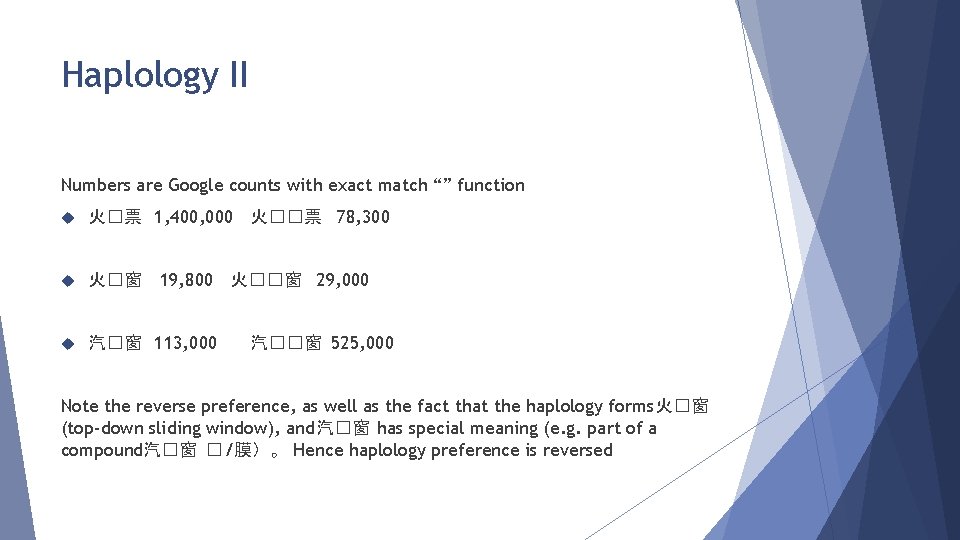

Haplology II Numbers are Google counts with exact match “” function 火�票 1, 400, 000 火��票 78, 300 火�窗 汽�窗 113, 000 19, 800 火��窗 29, 000 汽��窗 525, 000 Note the reverse preference, as well as the fact that the haplology forms火�窗 (top-down sliding window), and汽�窗 has special meaning (e. g. part of a compound汽�窗 � /膜)。 Hence haplology preference is reversed

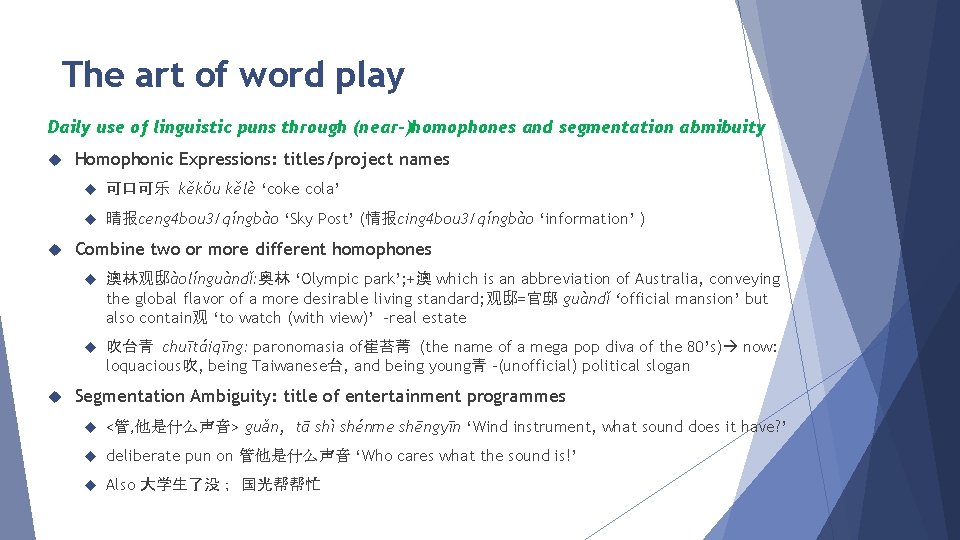

The art of word play Daily use of linguistic puns through (near-)homophones and segmentation abmibuity Homophonic Expressions: titles/project names 可口可乐 kěkǒu kělè ‘coke cola’ 晴报ceng 4 bou 3/qíngbào ‘Sky Post’ (情报cing 4 bou 3/qíngbào ‘information’ ) Combine two or more different homophones 澳林观邸àolínguàndǐ: 奥林 ‘Olympic park’; +澳 which is an abbreviation of Australia, conveying the global flavor of a more desirable living standard; 观邸=官邸 guàndǐ ‘official mansion’ but also contain观 ‘to watch (with view)’ -real estate 吹台青 chuītáiqīng: paronomasia of崔苔菁 (the name of a mega pop diva of the 80’s) now: loquacious吹, being Taiwanese台, and being young青 –(unofficial) political slogan Segmentation Ambiguity: title of entertainment programmes <管, 他是什么声音> guǎn, tā shì shénme shēngyīn ‘Wind instrument, what sound does it have? ’ deliberate pun on 管他是什么声音 ‘Who cares what the sound is!’ Also 大学生了没; 国光帮帮忙

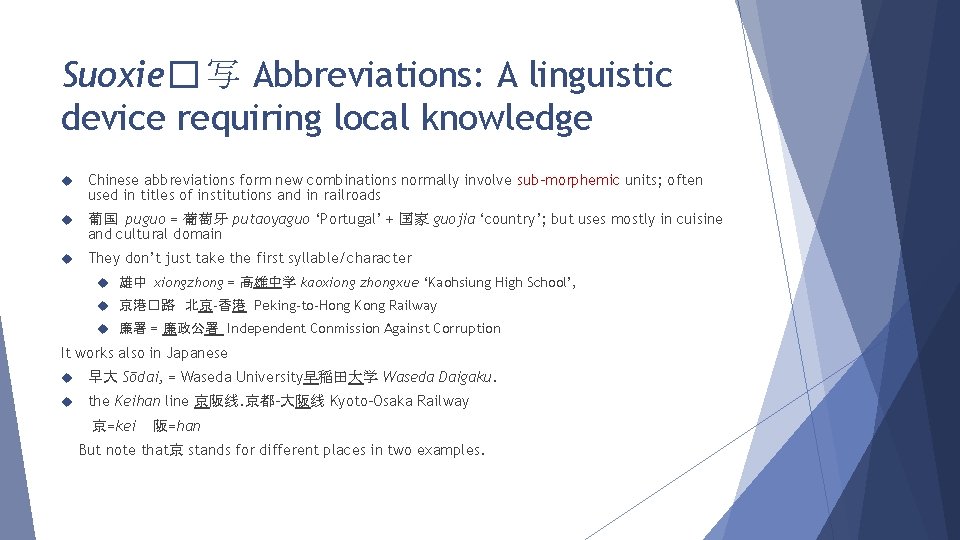

Suoxie� 写 Abbreviations: A linguistic device requiring local knowledge Chinese abbreviations form new combinations normally involve sub-morphemic units; often used in titles of institutions and in railroads 葡国 puguo = 葡萄牙 putaoyaguo ‘Portugal’ + 国家 guojia ‘country’; but uses mostly in cuisine and cultural domain They don’t just take the first syllable/character 雄中 xiongzhong = 高雄中学 kaoxiong zhongxue ‘Kaohsiung High School’, 京港�路 北京-香港 Peking-to-Hong Kong Railway 廉署 = 廉政公署 Independent Conmission Against Corruption It works also in Japanese 早大 Sōdai, = Waseda University早稲田大学 Waseda Daigaku. the Keihan line 京阪线. 京都-大阪线 Kyoto-Osaka Railway 京=kei 阪=han But note that京 stands for different places in two examples.

Conclusion Every word has different special meanings in the context of specific purpose Hence the regularity of meaning shifts/coercions for specific purposes based on understanding of qualia/purposes must be taught Specific purposes are not limited to domains, but should be interpreted as combinations of purposeful linguistic activities typically carried out in that specific domain Linguistic devices can help to identify different specific purposes

References Ahrens, Kathleen, and Siaw-Fong Chung. 2018. Metaphor in Chinese. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu. Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Ai, Weiwei, and Lee Ambrozy. 2011. Ai Weiwei’s blog: Writings, interviews and digital rants, 2006– 2009. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 1991. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised Edition). London: Verso. Assandri, Friederike, and Barbara Meisterernst. 2018. Chinese philosophy, religions, and language. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Bai, Qianshen. 1999. Image as word: A study of rebus play in Song painting (960 -1279). Metropolitan Museum Journal 34: 12+57– 72. Bodde, Derk. 1964, Sexual sympathetic magic in Han China. History of Religions 3 (2): 292– 299. Boltz, William. 1999. Language and writing. In The Cambridge history of ancient China, ed. Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy, 74– 123. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chao, Yuen Ren. 1968. A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press. Chan, Marjorie, and Yuhan Lin. 2018. Chinese language and gender research. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Davis, Stuart. 1993. Language games. In The encyclopedia of languages and linguistics, ed. Ron Asher, 1980– 1985. Oxford and New York: Pergamon Press. Dawkins, Richard. 2001. Das egoistische Gen, 309– 310. Hamburg: Rowohlt. Duanmu, San. 2000. The phonology of standard Chinese. New York: Oxford University Press. Führer, Bernhard. 2006. Riddles and politics: A graffito against Wang Anshi’s politics. In Kritik im alten und modernen China (Jahrbuch der Deutschen Vereinigung für Chinastudien 2), ed. Heiner Roetz, 144– 149. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Ge, Lingling, and Yuanjian He. 2018. Humour in Chinese. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Hou, Baolin, and Xue Baokun (eds). 1981. Papers on the art of Xiangsheng 相声艺术论集. Harbin: Heilongjiang Press.

References Huang, Chu-Ren, and Jiajuan Xiong. 2018. Linguistic synaesthesia in Chinese. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Huang, Chu-Ren, Shu-Kai Hsieh, and Keh-Jiann Chen. 2017. Mandarin Chinese words and parts of speech: A corpus-based study. London: Routledge Huang, Chu-Ren, and Shu-Kai Hsieh. 2015. Chinese lexical semantics: From radicals to event structure. In The Oxford handbook of Chinese linguistics, ed. William S. -Y. Wang and Chao-Fen Sun, 290– 305. New York: Oxford University Press. Huang, Chu-Ren, and Kathleen Ahrens. 2012 a. Numbers do. Hong Kong: Sun Ya Press. Huang, Chu-Ren, and Kathleen Ahrens. 2012 b. Ears hear. Hong Kong: Sun Ya Press. Huang, Chu-Ren 黃居仁. 1981. Chinese temporal concept – A study on temporal expressions in classic poetry 時間如流水-由古典詩歌中的時間用語談到 中國人的時間觀. Chung-Wai Literary 中外文學 9(11): 70– 88. Jianxun, Jiandao, and Jiajuan Xiong. 2018. Chinese and Buddhism. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo. 2018. Cursing, taboo and euphemism. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing. Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Jing-Schmidt, Zhuo, and Shu-Kai Hsieh. 2018. Chinese neologisms. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Kurpaska, Maria. 2018. Varieties of Chinese: Dialects or Sinitic languages? . In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Lee, Sophia. 2018. Chinese and emotion analysis. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Li, David C. S. , and Virginia Costa. 2009. Punning in Hong Kong Chinese media: Forms and functions. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 31(1): 77– 107. Lo, Feng-ju, Shujuan Yu, Jinquan Zheng, Chu-Ren Huang, Jinghui Chen, and Wanchun Chai 羅鳳珠, 余淑娟, 鄭錦全, 黃居仁, 陳靜慧, 蔡宛純. 2002. Computer assisted language learning Minnan Dialect: 16 th century Minnan classic Lychee Mirror learning website閩南語電腦輔助教學:十六世紀閩南 語第一名著《荔鏡記》教學網站. Paper Presented at International Symposium on Chinese Curriculum Reform in Chinese Language Education in the New Century中國語文教育百年暨新世紀語文課程改革國際研討會, Beijing. Lu, Sheldon H. 2007. Chinese modernity and global biopolitics: Studies in literature and visual culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. Lu, Sheldon H. , and Emilie Y-Y Yeh. 2005. Introduction: Mapping the field of Chinese-language cinema. In Chinese-language film: Historiography, poetics, politics, ed. Sheldon H. Lu and Emilie Y-Y Yeh, 1– 24. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

References Lu, Zongli. 1995. Heaven’s mandate and man’s destiny in early medieval China: The role of prophecy in politics. Madision: University of Wisconsin. Masini, Federico. 2018. Christianity and the Chinese language. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics , ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Meisterernst, Barbara. 2018. The function of poetic language and rhymes in pre-modern Chinese literature. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Moser, David. 1990. Reflexivity in the humor of Xiangsheng. Chinoperl Papers 15: 45– 68. Moser, David. 2018. Keeping the ci in fengci: A brief history of the Chinese verbal art of Xiangsheng. In Not just a laughing matter, ed. King-fai Tam and Sharon Wesoky. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. Neergaard, Karl, and Chu-Ren Huang. 2016. Graph theoretic approach to Mandarin syllable segmentation. Paper presented at The Fifteen International Symposium on Chinese Language and Linguistics (Is. CLL) , Hsinchu, Taiwan. Ng, Kenny K. K. 吳國坤. 2009. Language, region, and geopolitics: The urban comedy of Cathay/MP&GI in the 1950 s and 60 s語言、地域、地緣政治:試 論五、六十年代國泰/電懋的都市喜劇Film Appreciation Academic Journal 電影欣賞學刊6(2): 96– 112. [expanded Chinese version of Ng 2007] Ng, Kenny K. K. 2007. Romantic comedies of Cathay-MP&GI in the 1950 s and 60 s: Language, locality and urban character. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 49. Shu, Dingfang. 2015. Chinese Xiehouyu (歇后�) and the interpretation of metaphor and metonymy. Journal of Pragmatics 86: 74– 79. Su, I-Wen, and Shuping Huang. 2018. Irony in Chinese languages: An overview and a case study. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Tam, King-fai, and Sharon Wesoky (eds). 2018. Not just a laughing matter. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. Wacker, Gudrun, and Matthis Kaiser. 2008. Nachhaltigkeit auf chinesische Art. Das Konzept der ‘harmonischen Gesellschaft’. SWP Studien, July 18. Available at http: //www. swpberlin. org/fileadmin/contents/products/studien/2008_S 18_wkr_ks. pdf. Accessed on 13 September 2016. Wang, Guowei 王国�. 1957/1998. Anthology of Wang Guowei's writings on drama: An evidential study of Song and Yuan drama and other works 王国��曲�文及宋元�曲考及其他. Beijing: Chinese Drama Publication Press/Taipei: Liren. Wang, William S. -Y. 2013. Love and war in ancient China—Voices from the Shijing. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

References Wang, Xuan, Kaspar Juffermans, and Caixia Du. 2016. Harmony as language policy in China, Language Policy 5: 299– 321. West, Setephen H. , and Wilt L. Idema. 2015. (Translation) The orphan of Zhao and other Yuan plays: The earliest known versions. New York: Columbia University Press. Wiener, Seth. 2011. Grass-mud-horses to victory: The phonological constraints of subversive puns. In: Proceedings of the 23 rd North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-23) (Volume 1), ed. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, 156– 172, Eugene: University of Oregon. Wines, Michael. 2009. A dirty pun tweaks China’s online censors. The New York Times, March 11. Available at at http: //www. nytimes. com/2009/03/12/world/asia/12 beast. html? em. Accessed on 13 September 2016. Xiao, Zhiwei. 1999. Constructing a new national culture: Film censorship and the issues of Cantonese dialect, superstition, and sex in the Nanjing decade. In Cinema and urban culture in Shanghai: 1922 -1943, ed. Zhang Yingjin, 183– 199. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Xing, Zhiqun J. 2018. Commedatory and derogatory expressions in Chinese. In The Routledge handbook of Chinese applied linguistics, ed. Chu-Ren Huang, Zhuo Jing-Schmidt, and Barbara Meisterernst, XX–XX. London: Routledge. Yang, Guobin, 2015, The online practice of political satire in China: Between ritual and resistance. The International Communication Gazette 77(3): 215– 231. Yung, Sai-shing 容世誠. 2013. 'A native sound is worth a million': The interaction between 1960 s Chaozhoudialect film industries in China, Hong Kong and Southeast Asia「鄉音抵萬金」:六十年代潮劇電影 業的三 地互動. In The Chaozhou-dialect films of Hong Kong (in Chinese) 香港潮語電影尋跡, ed. Wu Jun-yu 吳君玉 60– 72. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive. Zhou, Deqing 周德清. 1324. Rhymes of the central plains 中原音韻.

Abstracts Language Arts: the study and improvement of the arts of language, especially in terms of the understanding of language in different genres and the effective use of language for different purposes, including persuasion and expression. Language arts and language for specific purposes are closely related. In this talk, based on and extended from the chapter on linguistic devices for Chinese language arts in the Routledge Handbook of Chinese Applied Linguistics (Huang et al. 2018), I will introduce a few aspects of Chinese language arts that are useful in the study and learning of Chinese for specific purposes.

Contents how such polysemy can be used as signature of language for specific purposes, e. g. , the fact that the term ‘rose’ can refer to the flower with or without the stem, petals, the plant, or the extracted essential oil, among others. the linguistic devices used in Chinese language arts overview of different genres drama, the language art form which is probably closest to the simultaneous use of language (though scripted and highly stylized) cinema, a language art form delivered in a non-simultaneous medium with a focus on visual presentation how language arts can interact with other media, especially in performing art children’s literature (not only as another form of language arts but also as a foundation for building an appreciation for Chinese language arts)

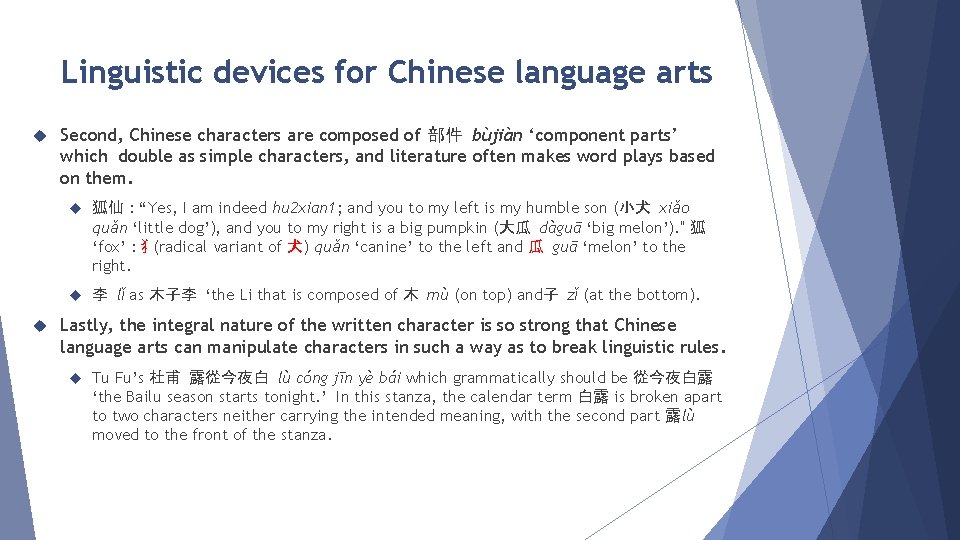

The art of word play Involve both numerals and other languages ‘fun 假’ vs, 放假 fàngjià ‘to take holidays’: ads aiming at young professionals Cantonese: 8 baat 3 to stand for 发 faat 3 201314 èlíngyīsānyīsì: 爱你一生一世 àinǐyīshēngyīshì ‘(Will) love you (my) whole life!’ -typically as memorable slogans (for (ad) campaigns, activities etc. ) 夏木漱石 xiàmùshùshí ‘summer trees, river gurgling over stones’ : a popular name for property developments, a pun on the name of one of the best known Japanese authors 夏目漱石 Natsume Soseki Japanese names are quite apt as they are presented in Chinese characters, however western names, e. g. Beethoven, Mozart, Versaille, Fontainebleau, etc. are aso used very often)

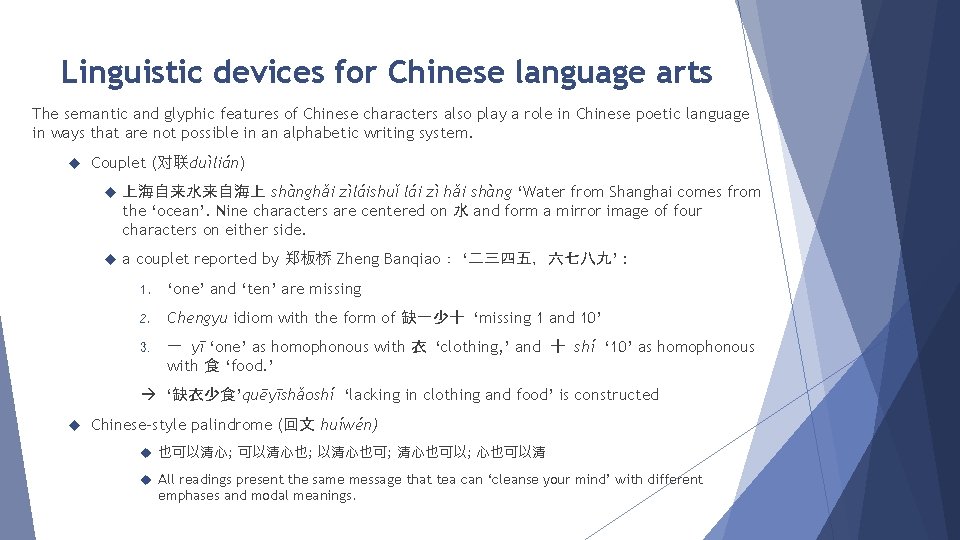

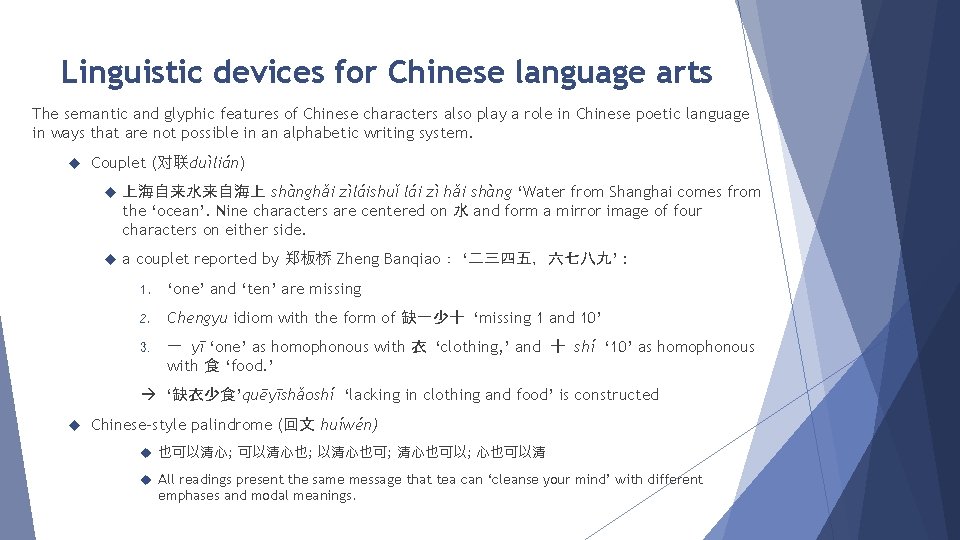

Linguistic devices for Chinese language arts Second, Chinese characters are composed of 部件 bùjiàn ‘component parts’ which double as simple characters, and literature often makes word plays based on them. 狐仙 : “Yes, I am indeed hu 2 xian 1; and you to my left is my humble son (小犬 xiǎo quǎn ‘little dog’), and you to my right is a big pumpkin (大瓜 dàguā ‘big melon’). " 狐 ‘fox’ : 犭(radical variant of 犬) quǎn ‘canine’ to the left and 瓜 guā ‘melon’ to the right. 李 lǐ as 木子李 ‘the Li that is composed of 木 mù (on top) and子 zǐ (at the bottom). Lastly, the integral nature of the written character is so strong that Chinese language arts can manipulate characters in such a way as to break linguistic rules. Tu Fu’s 杜甫 露從今夜白 lù cóng jīn yè bái which grammatically should be 從今夜白露 ‘the Bailu season starts tonight. ’ In this stanza, the calendar term 白露 is broken apart to two characters neither carrying the intended meaning, with the second part 露lù moved to the front of the stanza.

Linguistic devices for Chinese language arts The semantic and glyphic features of Chinese characters also play a role in Chinese poetic language in ways that are not possible in an alphabetic writing system. Couplet (对联duìlián) 上海自来水来自海上 shànghǎi zìláishuǐ lái zì hǎi shàng ‘Water from Shanghai comes from the ‘ocean’. Nine characters are centered on 水 and form a mirror image of four characters on either side. a couplet reported by 郑板桥 Zheng Banqiao: ‘二三四五,六七八九’ : 1. ‘one’ and ‘ten’ are missing 2. Chengyu idiom with the form of 缺一少十 ‘missing 1 and 10’ 3. 一 yī ‘one’ as homophonous with 衣 ‘clothing, ’ and 十 shí ‘ 10’ as homophonous with 食 ‘food. ’ ‘缺衣少食’quēyīshǎoshí ‘lacking in clothing and food’ is constructed Chinese-style palindrome (回文 huíwén) 也可以清心; 可以清心也; 以清心也可; 清心也可以; 心也可以清 All readings present the same message that tea can ‘cleanse your mind’ with different emphases and modal meanings.

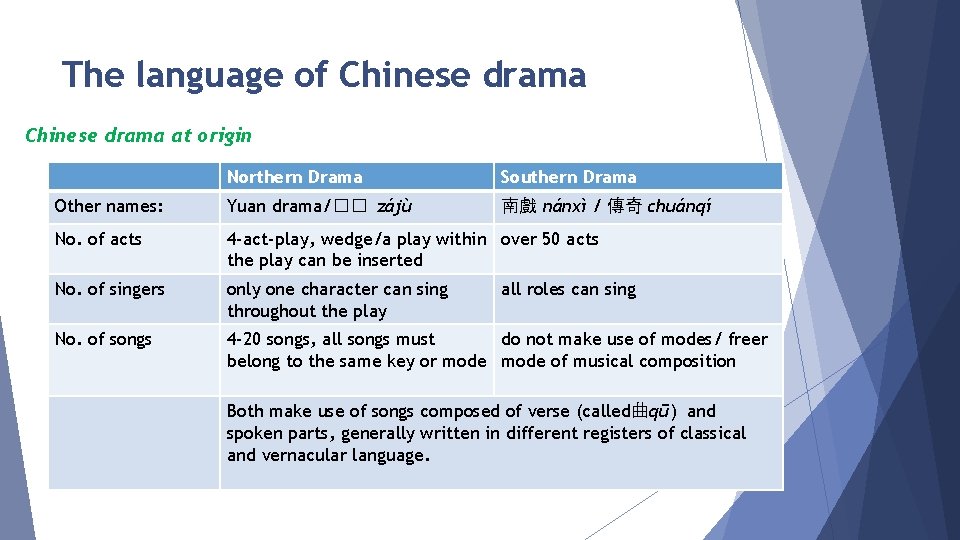

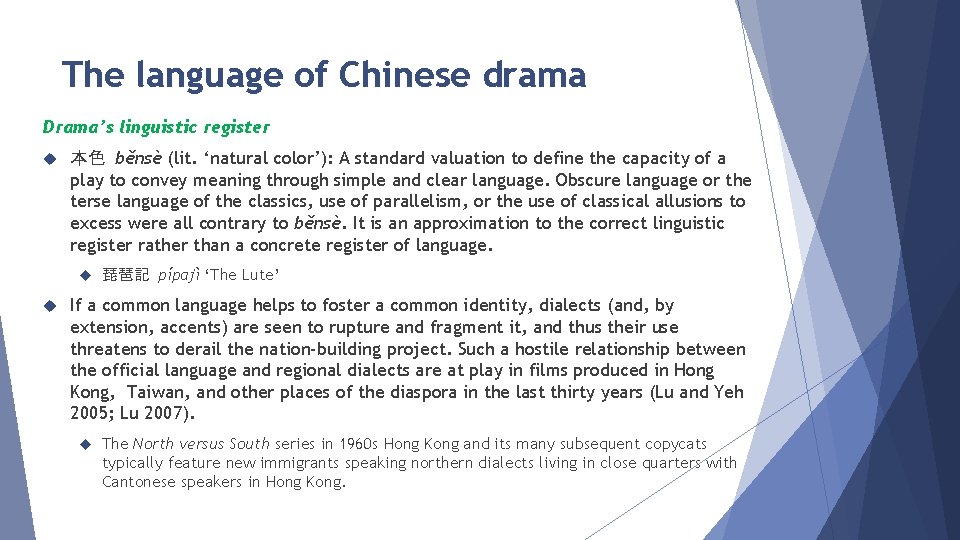

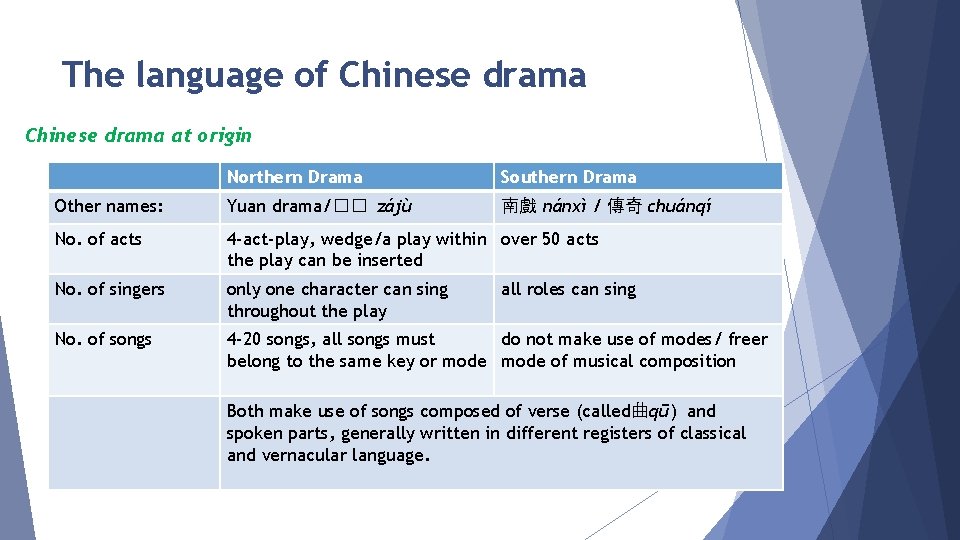

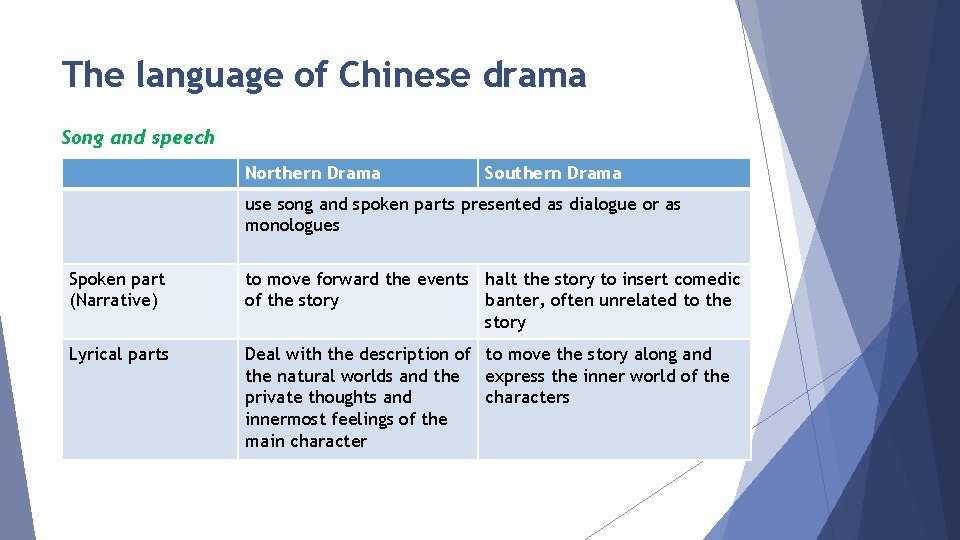

The language of Chinese drama at origin Northern Drama Southern Drama Other names: Yuan drama/�� zájù 南戲 nánxì / 傳奇 chuánqí No. of acts 4 -act-play, wedge/a play within over 50 acts the play can be inserted No. of singers only one character can sing throughout the play No. of songs 4 -20 songs, all songs must do not make use of modes/ freer belong to the same key or mode of musical composition all roles can sing Both make use of songs composed of verse (called曲qū) and spoken parts, generally written in different registers of classical and vernacular language.

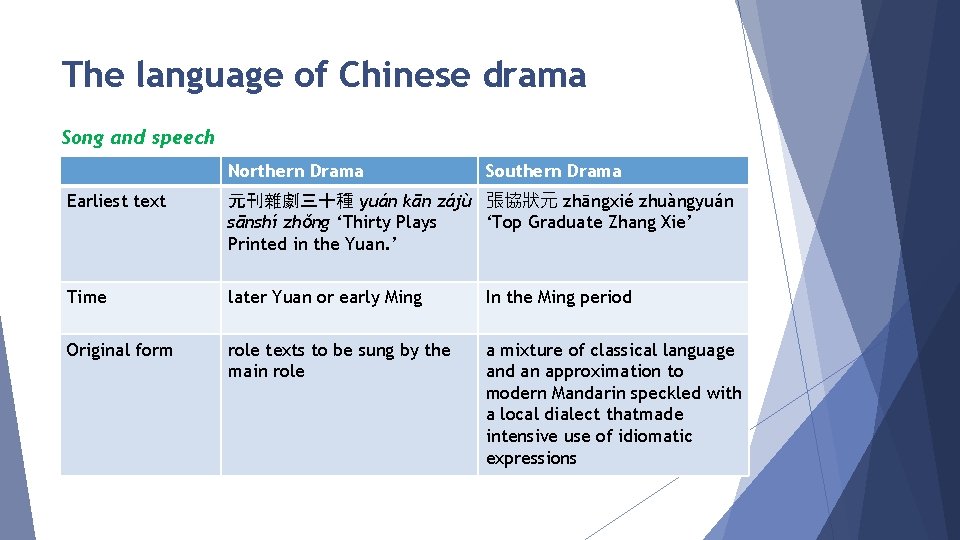

The language of Chinese drama Song and speech Northern Drama Southern Drama Earliest text 元刊雜劇三十種 yuán kān zájù 張協狀元 zhāngxié zhuàngyuán sānshí zhǒng ‘Thirty Plays ‘Top Graduate Zhang Xie’ Printed in the Yuan. ’ Time later Yuan or early Ming In the Ming period Original form role texts to be sung by the main role a mixture of classical language and an approximation to modern Mandarin speckled with a local dialect thatmade intensive use of idiomatic expressions

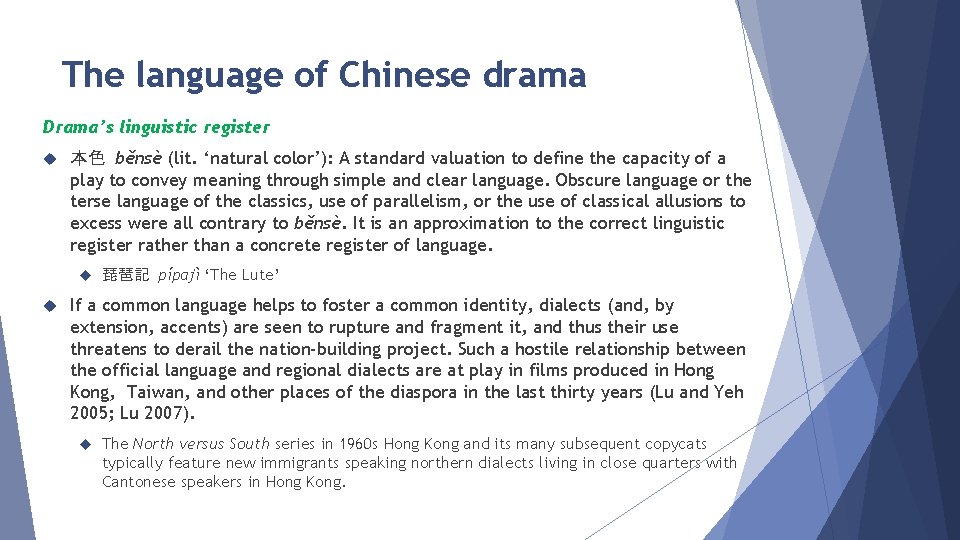

The language of Chinese drama Song and speech Northern Drama Southern Drama use song and spoken parts presented as dialogue or as monologues Spoken part (Narrative) to move forward the events halt the story to insert comedic of the story banter, often unrelated to the story Lyrical parts Deal with the description of to move the story along and the natural worlds and the express the inner world of the private thoughts and characters innermost feelings of the main character

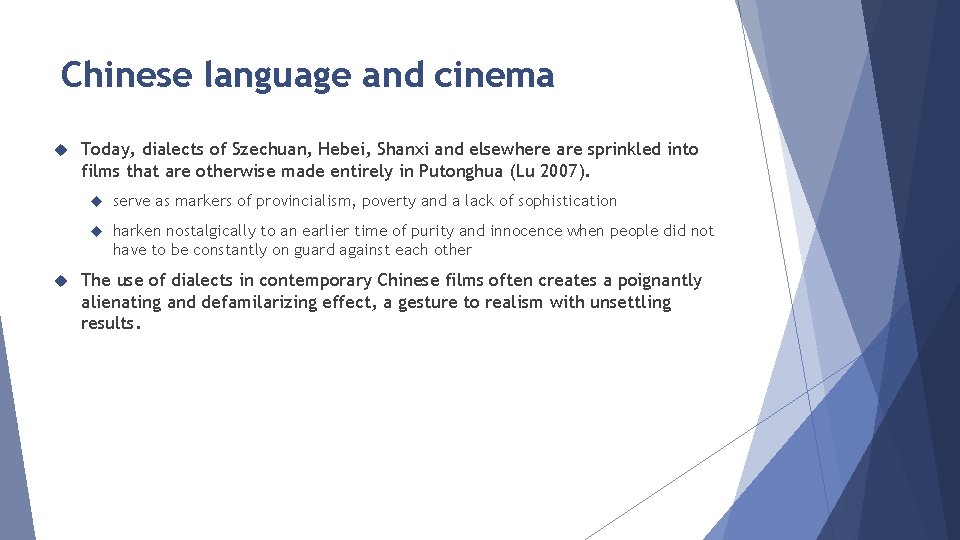

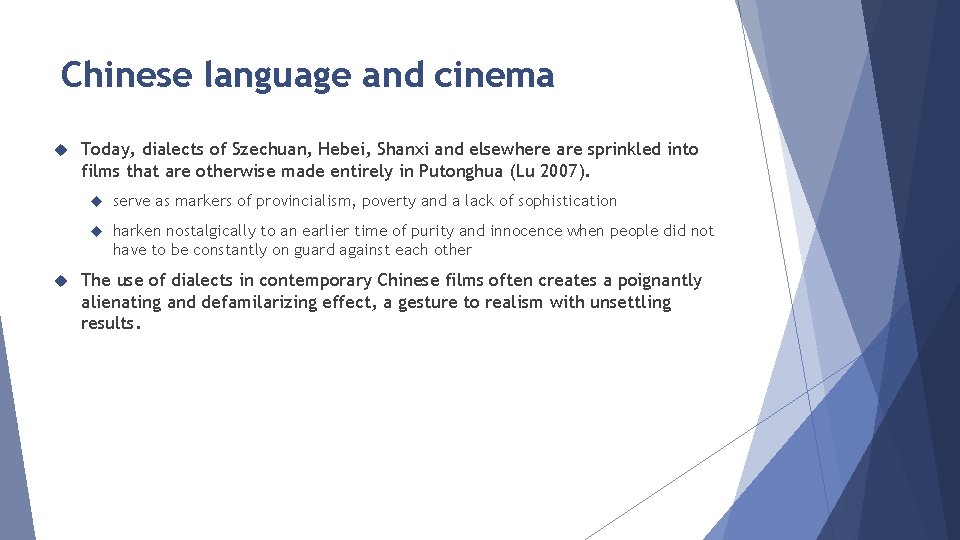

The language of Chinese drama Drama’s linguistic register 本色 běnsè (lit. ‘natural color’): A standard valuation to define the capacity of a play to convey meaning through simple and clear language. Obscure language or the terse language of the classics, use of parallelism, or the use of classical allusions to excess were all contrary to běnsè. It is an approximation to the correct linguistic register rather than a concrete register of language. 琵琶記 pípajì ‘The Lute’ If a common language helps to foster a common identity, dialects (and, by extension, accents) are seen to rupture and fragment it, and thus their use threatens to derail the nation-building project. Such a hostile relationship between the official language and regional dialects are at play in films produced in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other places of the diaspora in the last thirty years (Lu and Yeh 2005; Lu 2007). The North versus South series in 1960 s Hong Kong and its many subsequent copycats typically feature new immigrants speaking northern dialects living in close quarters with Cantonese speakers in Hong Kong.

Chinese language and cinema Today, dialects of Szechuan, Hebei, Shanxi and elsewhere are sprinkled into films that are otherwise made entirely in Putonghua (Lu 2007). serve as markers of provincialism, poverty and a lack of sophistication harken nostalgically to an earlier time of purity and innocence when people did not have to be constantly on guard against each other The use of dialects in contemporary Chinese films often creates a poignantly alienating and defamilarizing effect, a gesture to realism with unsettling results.

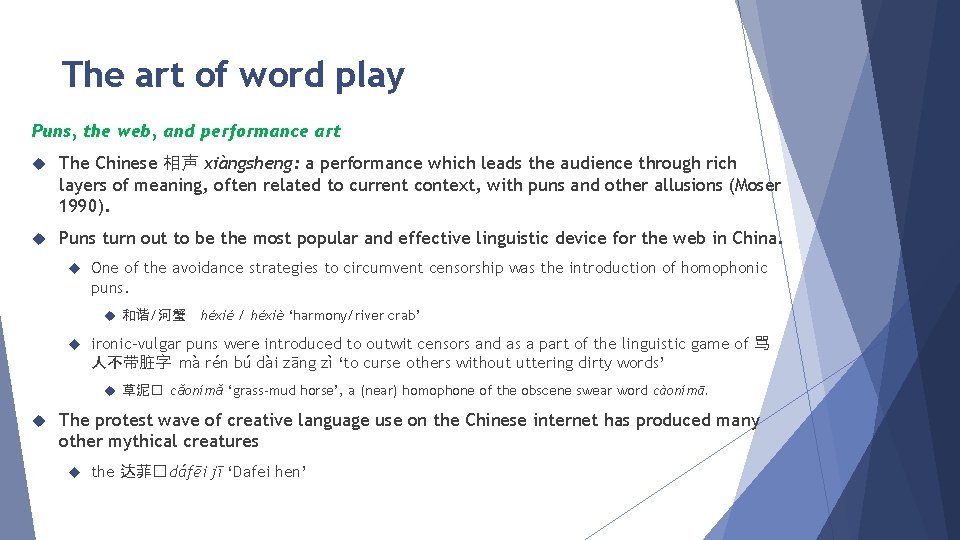

The art of word play Puns, the web, and performance art The Chinese 相声 xiàngsheng: a performance which leads the audience through rich layers of meaning, often related to current context, with puns and other allusions (Moser 1990). Puns turn out to be the most popular and effective linguistic device for the web in China. One of the avoidance strategies to circumvent censorship was the introduction of homophonic puns. 和谐/河蟹 héxié / héxiè ‘harmony/river crab’ ironic-vulgar puns were introduced to outwit censors and as a part of the linguistic game of 骂 人不带脏字 mà rén bú dài zāng zì ‘to curse others without uttering dirty words’ 草泥� cǎonímǎ ‘grass-mud horse’, a (near) homophone of the obscene swear word càonímā. The protest wave of creative language use on the Chinese internet has produced many other mythical creatures the 达菲� dáfēi jī ‘Dafei hen’

The art of word play Linguistic constraints and historical usage of word play Syllable structure of Chinese: CVX (Consonant-Vowel-Coda) Wiener (2011) listed three possible constraints on language games played with puns on the web: (1) a change in the orthographic representation (an avoidance strategy against censorship), (2) preservation of the syllable, and (3) preservation of tone if possible Test: Wiener employed Optimality Theory, established a number of ranked constraints, including semantic and syntactic ones Results: the confirmation that tone does not play a determining role in the selection of a near homophonous syllable for the pun; the segment alone suffices for the lexical activation of the association. Possible explanation: contrary to common assumption, the C, V, and X segments (but not tone), are the most salient elements in modeling phonological neighourhoods for Mandarin Chinese, , as shown in a recent study by Neergaard and Huang (2016).

The art of word play Homophones 春秋繁露chūnqiū fánlù ‘Chunqiu Fanlu’: 四時皆以庚子之日令吏民夫婦皆偶處。 sī shí jiē yǐ gēngzǐ zhī rì líng lì mín fū fù jiē ǒu chǔ Four__season__all__YI__gengzi__GEN___day__make__order__official___people fū fù jiē ǒu chǔ husband__wife__all__pairwise__dwell ‘In all of the four seasons, on the keng-tzu days, all husbands and wives among officials and commoners are ordered to cohabit. ’ (tr. Bodde 1964) ǒu chǔ is extremely infrequent, can only be interpreted as a euphemism for sexual intercourse Gengzi may refer to the homophonous更 gēng ‘again’ or ‘change’, and 子zǐ ‘name of the first cyclical branch’ to the near-homophonous word 孳 zī ‘engender’ Lu (1995): puns in讖 chèn prophecy Führer (2006): 析字 xīzì ‘parsing characters’ as political criticism in Song period China

The art of word play Linguistic Puns 露從今夜白,月是故鄉明 Original meaning: ‘(We) start the báilù solar term tonight, and the moon (that we watch) is the same bright moon over (our) hometown’ Suggestive meaning: ‘dews will turn white tonight and the moon is brighter at home’

The art of word play Linguistic puns and visual art Rebus: typically refers to mixed writing involving pictograms, Chinese scholars borrowed this term to refer to a painting constructed to represent a well-known expression (Bai 1999) bat (蝠 fú) stands for good fortune (福fú) orange (桔 jié) stands for good omen (吉jí) a. 三猿得鹭 sān yuán dé lù Three gibbon catch egret b. 三元得祿 sānyuan dé lù triple-first catch salaried-office The tradition of relying on linguistic puns and rebuses to underline the motive and title of a piece of art is well adopted in modern times and in different media. monkey-on-horse motif and other puns related to monkeys are represented in print, audial, visual, and digital forms for most of the 2016 New Year arts, the most recent being the Year of the Monkey

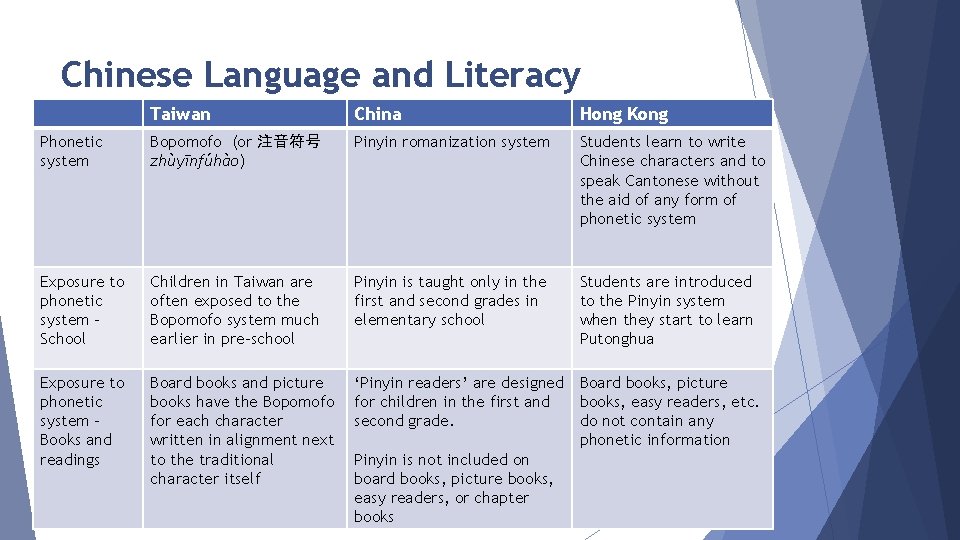

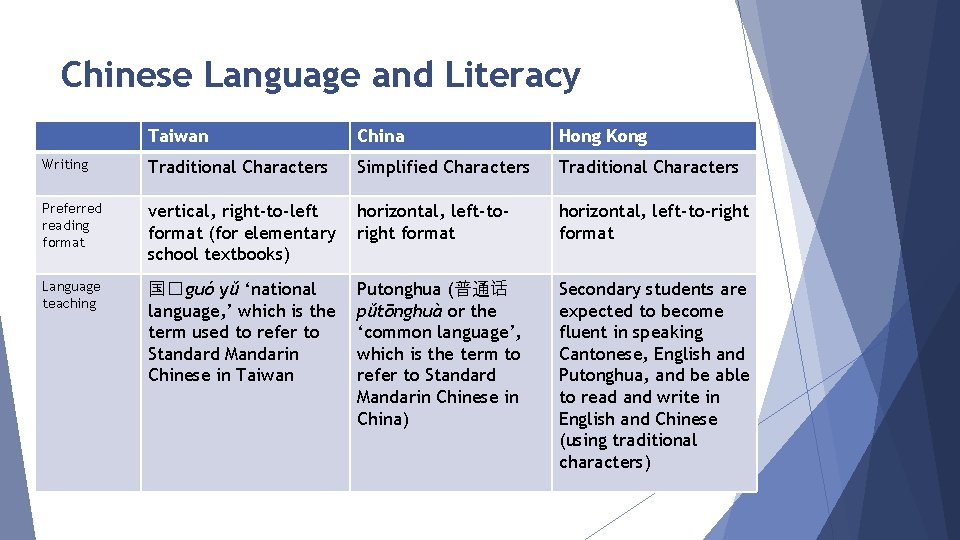

Chinese Language and Literacy Taiwan China Hong Kong Writing Traditional Characters Simplified Characters Traditional Characters Preferred reading format vertical, right-to-left format (for elementary school textbooks) horizontal, left-toright format horizontal, left-to-right format Language teaching 国� guó yǔ ‘national language, ’ which is the term used to refer to Standard Mandarin Chinese in Taiwan Putonghua (普通话 pǔtōnghuà or the ‘common language’, which is the term to refer to Standard Mandarin Chinese in China) Secondary students are expected to become fluent in speaking Cantonese, English and Putonghua, and be able to read and write in English and Chinese (using traditional characters)

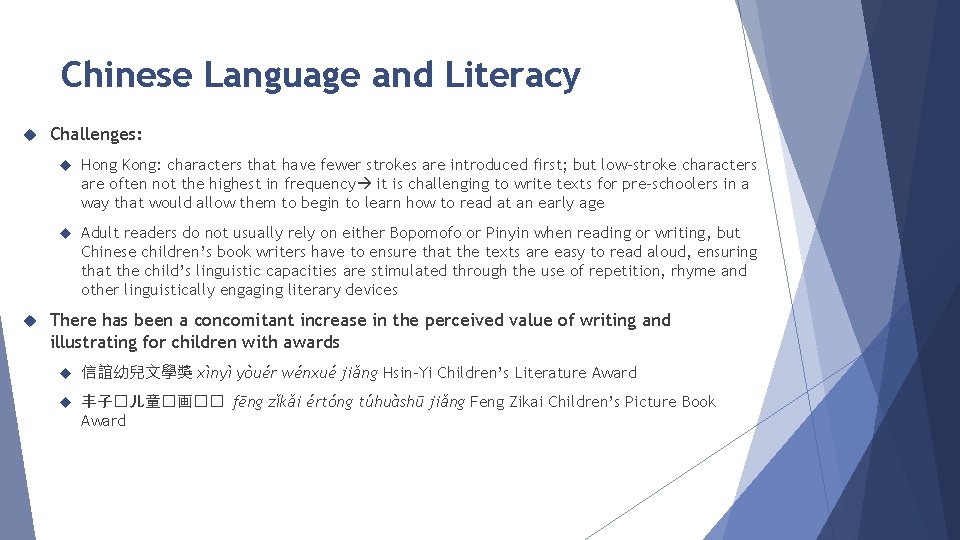

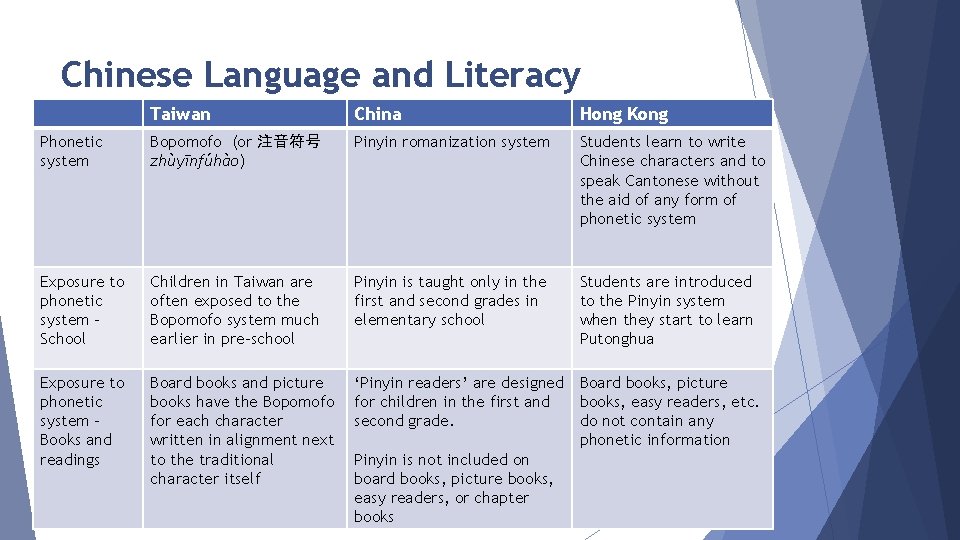

Chinese Language and Literacy Taiwan China Hong Kong Phonetic system Bopomofo (or 注音符号 zhùyīnfúhào) Pinyin romanization system Students learn to write Chinese characters and to speak Cantonese without the aid of any form of phonetic system Exposure to phonetic system School Children in Taiwan are often exposed to the Bopomofo system much earlier in pre-school Pinyin is taught only in the first and second grades in elementary school Students are introduced to the Pinyin system when they start to learn Putonghua Exposure to phonetic system – Books and readings Board books and picture books have the Bopomofo for each character written in alignment next to the traditional character itself ‘Pinyin readers’ are designed Board books, picture for children in the first and books, easy readers, etc. second grade. do not contain any phonetic information Pinyin is not included on board books, picture books, easy readers, or chapter books

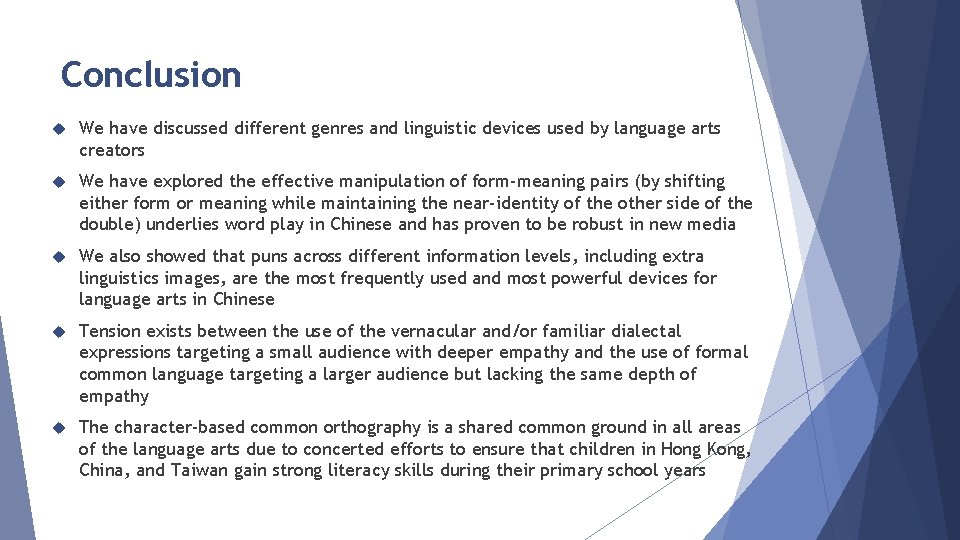

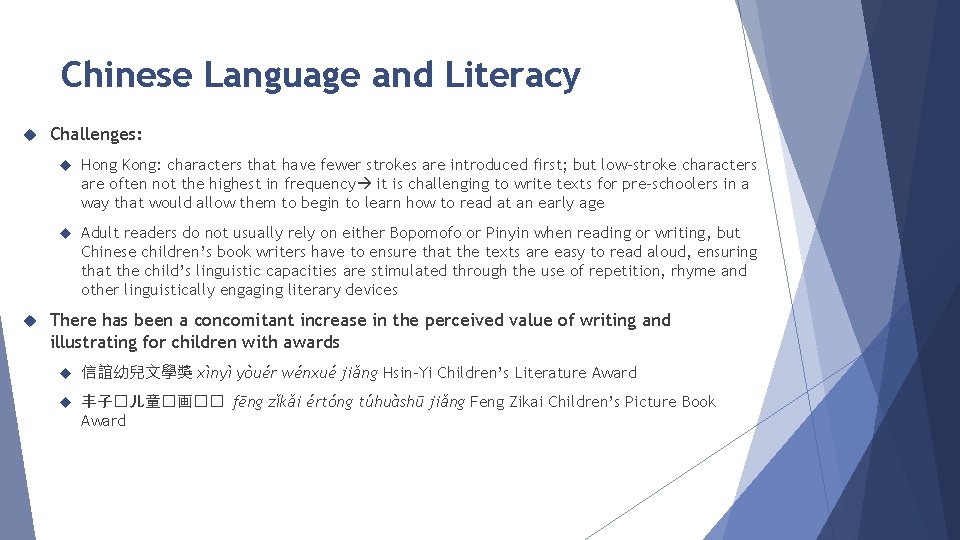

Chinese Language and Literacy Challenges: Hong Kong: characters that have fewer strokes are introduced first; but low-stroke characters are often not the highest in frequency it is challenging to write texts for pre-schoolers in a way that would allow them to begin to learn how to read at an early age Adult readers do not usually rely on either Bopomofo or Pinyin when reading or writing, but Chinese children’s book writers have to ensure that the texts are easy to read aloud, ensuring that the child’s linguistic capacities are stimulated through the use of repetition, rhyme and other linguistically engaging literary devices There has been a concomitant increase in the perceived value of writing and illustrating for children with awards 信誼幼兒文學獎 xìnyì yòuér wénxué jiǎng Hsin-Yi Children’s Literature Award 丰子�儿童�画�� fēng zǐkǎi értóng túhuàshū jiǎng Feng Zikai Children’s Picture Book Award

Conclusion We have discussed different genres and linguistic devices used by language arts creators We have explored the effective manipulation of form-meaning pairs (by shifting either form or meaning while maintaining the near-identity of the other side of the double) underlies word play in Chinese and has proven to be robust in new media We also showed that puns across different information levels, including extra linguistics images, are the most frequently used and most powerful devices for language arts in Chinese Tension exists between the use of the vernacular and/or familiar dialectal expressions targeting a small audience with deeper empathy and the use of formal common language targeting a larger audience but lacking the same depth of empathy The character-based common orthography is a shared common ground in all areas of the language arts due to concerted efforts to ensure that children in Hong Kong, China, and Taiwan gain strong literacy skills during their primary school years

Language for specific purposes

Language for specific purposes Creative arts programme of assessment

Creative arts programme of assessment Anglo chinese school chinese name

Anglo chinese school chinese name What is esp english for specific purposes

What is esp english for specific purposes What is esp english for specific purposes

What is esp english for specific purposes Glycerin specific gravity

Glycerin specific gravity Specific gravity units g/ml

Specific gravity units g/ml Ib chinese a language and literature

Ib chinese a language and literature Language in life

Language in life Language arts

Language arts Why do we use question marks

Why do we use question marks Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Symbol language arts definition

Symbol language arts definition Reasoning through language arts

Reasoning through language arts English

English Strands in language arts

Strands in language arts Language arts

Language arts Gicsd

Gicsd Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language chart

Language chart Grade 5

Grade 5 Signpost chart example

Signpost chart example Language

Language Language arts symbols

Language arts symbols Language arts

Language arts ..

.. Language arts trailer

Language arts trailer Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Ricas accommodations

Ricas accommodations Ricas accommodations

Ricas accommodations Math science social studies language arts

Math science social studies language arts Language arts

Language arts Language arts

Language arts Bilingual common core progressions

Bilingual common core progressions Jeopardy language arts

Jeopardy language arts Ricas english language arts

Ricas english language arts English language study design

English language study design Language in chinese

Language in chinese Language in chinese

Language in chinese Cangjie programming language

Cangjie programming language Language chinese

Language chinese Language chinese

Language chinese Language chinese

Language chinese Language

Language Formuö

Formuö Typiska drag för en novell

Typiska drag för en novell