Lambda Calculus PDCS 2 alpharenaming beta reduction eta

Lambda Calculus (PDCS 2) alpha-renaming, beta reduction, eta conversion, applicative and normal evaluation orders, Church. Rosser theorem, combinators, higher-order programming, recursion combinator, numbers, booleans Carlos Varela Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute September 4, 2015 C. Varela 1

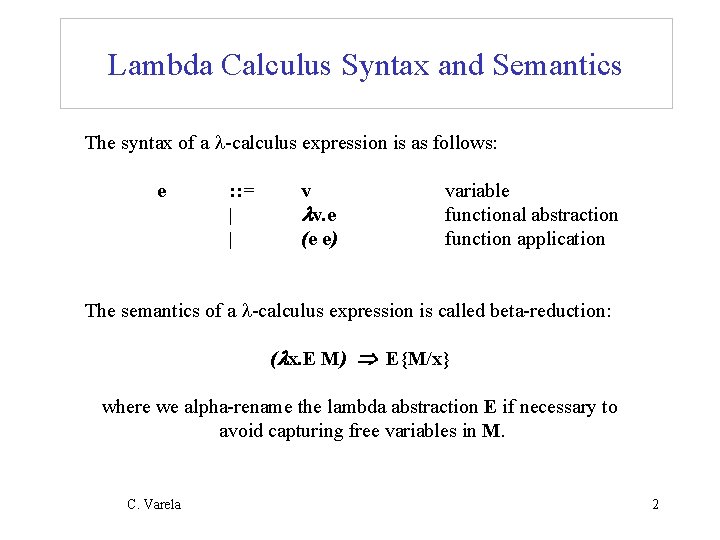

Lambda Calculus Syntax and Semantics The syntax of a -calculus expression is as follows: e : : = | | v v. e (e e) variable functional abstraction function application The semantics of a -calculus expression is called beta-reduction: ( x. E M) E{M/x} where we alpha-rename the lambda abstraction E if necessary to avoid capturing free variables in M. C. Varela 2

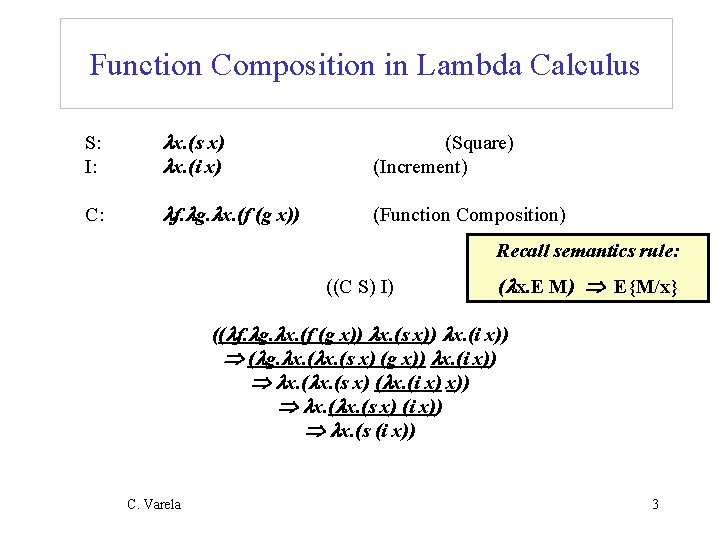

Function Composition in Lambda Calculus S: I: x. (s x) x. (i x) (Square) (Increment) C: f. g. x. (f (g x)) (Function Composition) Recall semantics rule: ((C S) I) ( x. E M) E{M/x} (( f. g. x. (f (g x)) x. (s x)) x. (i x)) ( g. x. (s x) (g x)) x. (i x)) x. (s x) ( x. (i x) x)) x. (s x) (i x)) x. (s (i x)) C. Varela 3

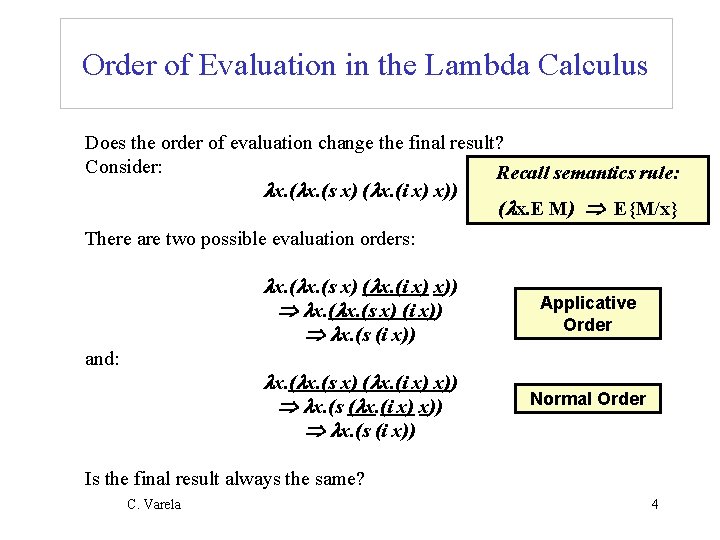

Order of Evaluation in the Lambda Calculus Does the order of evaluation change the final result? Consider: Recall semantics rule: x. (s x) ( x. (i x) x)) ( x. E M) E{M/x} There are two possible evaluation orders: and: x. (s x) ( x. (i x) x)) x. (s x) (i x)) x. (s (i x)) Applicative Order x. (s x) ( x. (i x) x)) x. (s (i x)) Normal Order Is the final result always the same? C. Varela 4

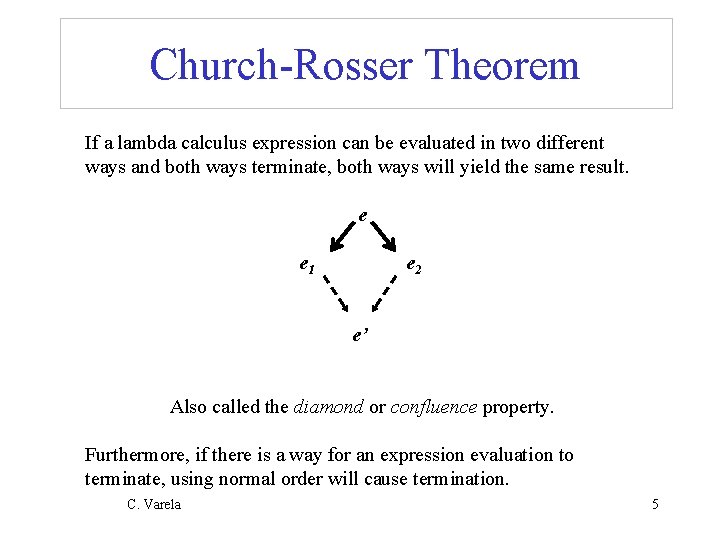

Church-Rosser Theorem If a lambda calculus expression can be evaluated in two different ways and both ways terminate, both ways will yield the same result. e e 1 e 2 e’ Also called the diamond or confluence property. Furthermore, if there is a way for an expression evaluation to terminate, using normal order will cause termination. C. Varela 5

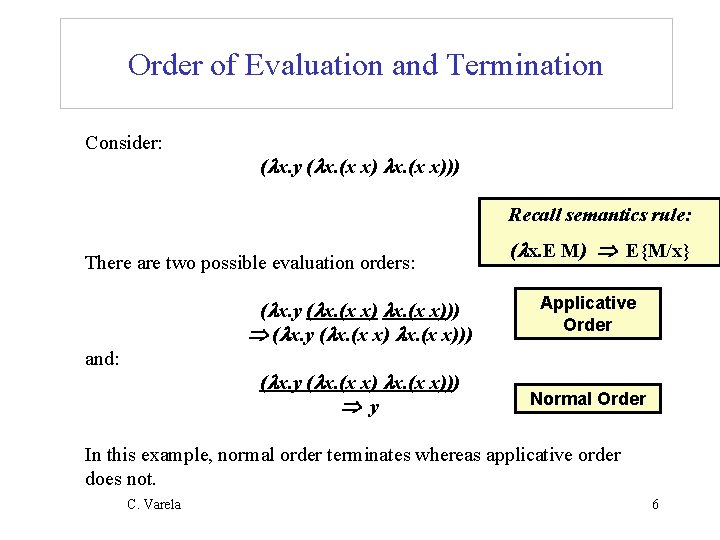

Order of Evaluation and Termination Consider: ( x. y ( x. (x x))) Recall semantics rule: There are two possible evaluation orders: and: ( x. E M) E{M/x} ( x. y ( x. (x x))) Applicative Order ( x. y ( x. (x x))) y Normal Order In this example, normal order terminates whereas applicative order does not. C. Varela 6

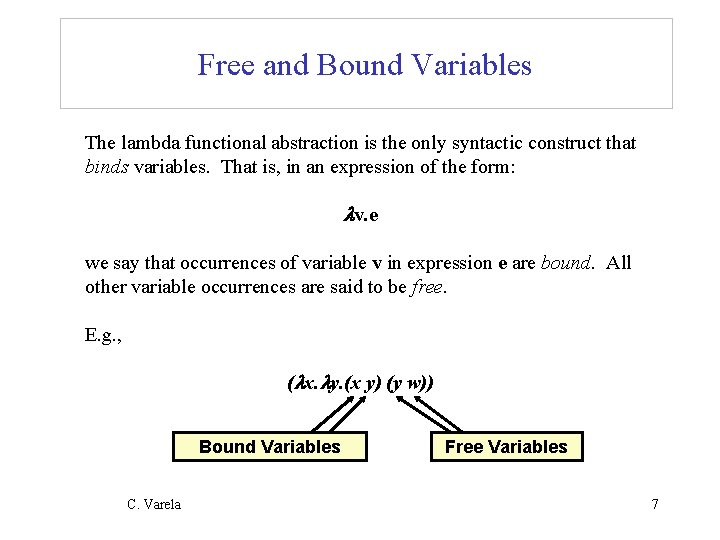

Free and Bound Variables The lambda functional abstraction is the only syntactic construct that binds variables. That is, in an expression of the form: v. e we say that occurrences of variable v in expression e are bound. All other variable occurrences are said to be free. E. g. , ( x. y. (x y) (y w)) Bound Variables C. Varela Free Variables 7

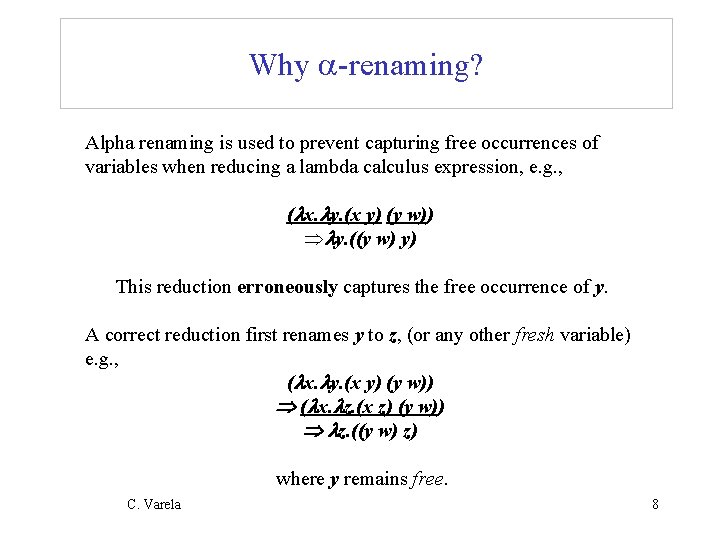

Why -renaming? Alpha renaming is used to prevent capturing free occurrences of variables when reducing a lambda calculus expression, e. g. , ( x. y. (x y) (y w)) Þ y. ((y w) y) This reduction erroneously captures the free occurrence of y. A correct reduction first renames y to z, (or any other fresh variable) e. g. , ( x. y. (x y) (y w)) ( x. z. (x z) (y w)) z. ((y w) z) where y remains free. C. Varela 8

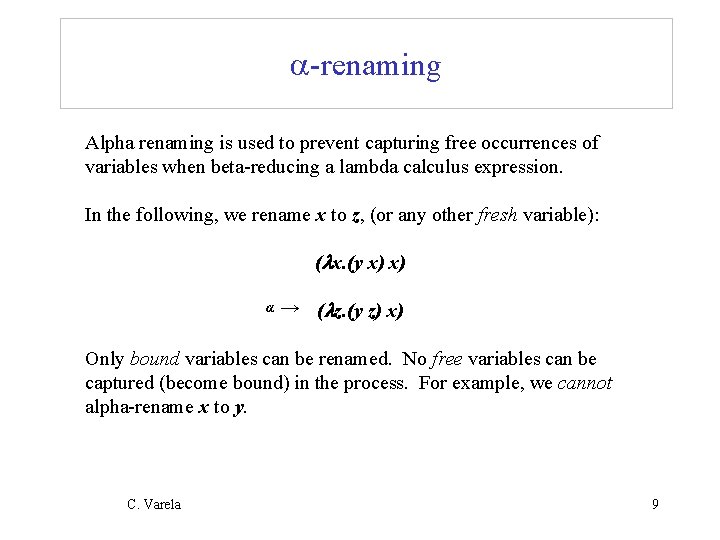

-renaming Alpha renaming is used to prevent capturing free occurrences of variables when beta-reducing a lambda calculus expression. In the following, we rename x to z, (or any other fresh variable): ( x. (y x) x) α → ( z. (y z) x) Only bound variables can be renamed. No free variables can be captured (become bound) in the process. For example, we cannot alpha-rename x to y. C. Varela 9

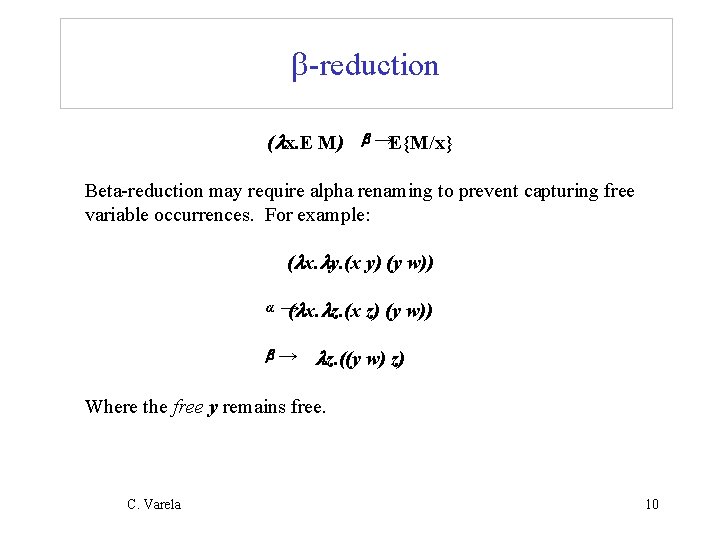

b-reduction ( x. E M) b →E{M/x} Beta-reduction may require alpha renaming to prevent capturing free variable occurrences. For example: ( x. y. (x y) (y w)) α → ( x. z. (x z) (y w)) b → z. ((y w) z) Where the free y remains free. C. Varela 10

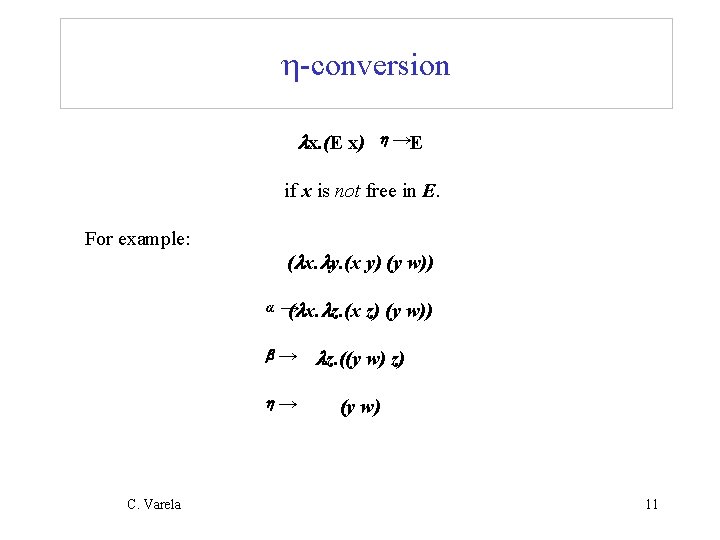

h-conversion x. (E x) h →E if x is not free in E. For example: ( x. y. (x y) (y w)) α → ( x. z. (x z) (y w)) b → z. ((y w) z) h→ C. Varela (y w) 11

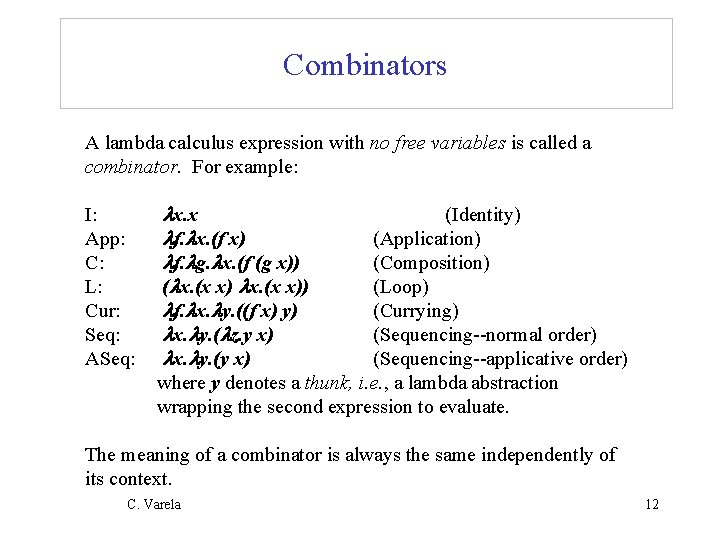

Combinators A lambda calculus expression with no free variables is called a combinator. For example: I: App: C: L: Cur: Seq: ASeq: x. x f. x. (f x) f. g. x. (f (g x)) ( x. (x x)) f. x. y. ((f x) y) x. y. ( z. y x) x. y. (y x) (Identity) (Application) (Composition) (Loop) (Currying) (Sequencing--normal order) (Sequencing--applicative order) where y denotes a thunk, i. e. , a lambda abstraction wrapping the second expression to evaluate. The meaning of a combinator is always the same independently of its context. C. Varela 12

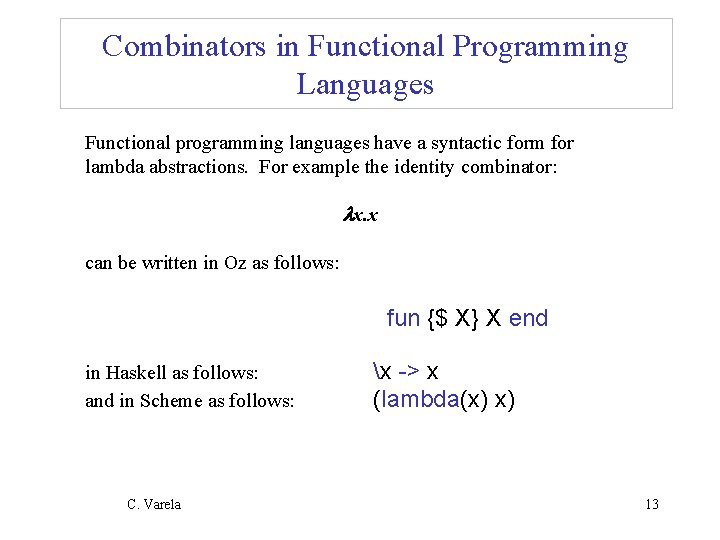

Combinators in Functional Programming Languages Functional programming languages have a syntactic form for lambda abstractions. For example the identity combinator: x. x can be written in Oz as follows: fun {$ X} X end in Haskell as follows: and in Scheme as follows: C. Varela x -> x (lambda(x) x) 13

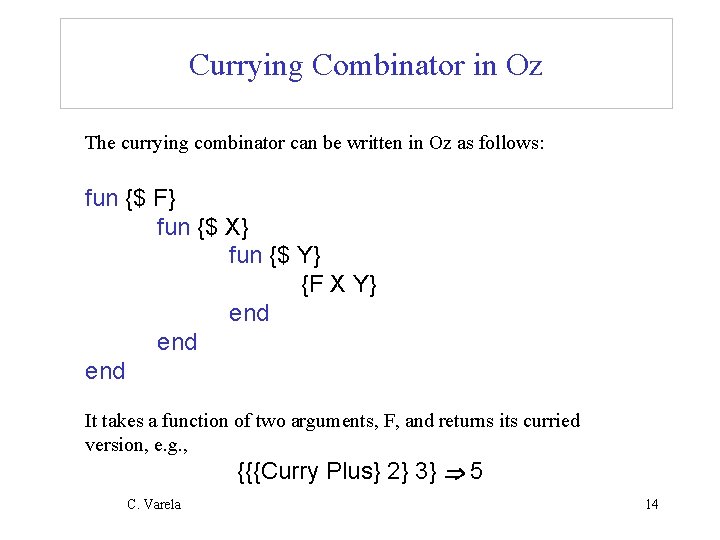

Currying Combinator in Oz The currying combinator can be written in Oz as follows: fun {$ F} fun {$ X} fun {$ Y} {F X Y} end end It takes a function of two arguments, F, and returns its curried version, e. g. , {{{Curry Plus} 2} 3} 5 C. Varela 14

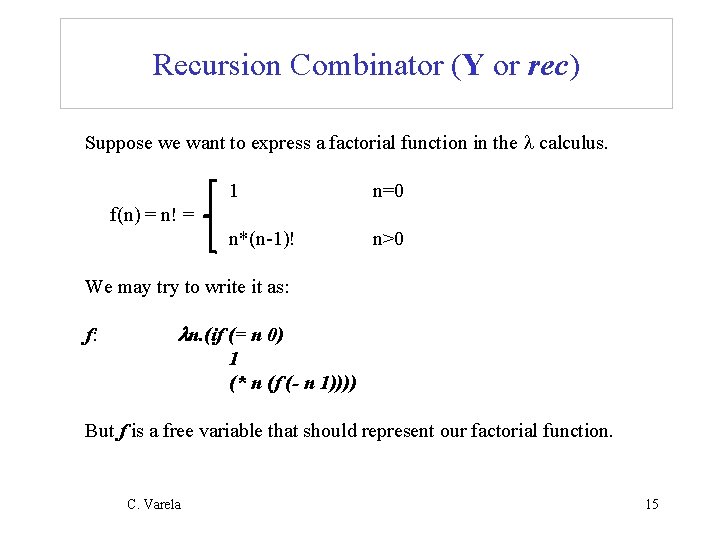

Recursion Combinator (Y or rec) Suppose we want to express a factorial function in the calculus. 1 n=0 n*(n-1)! n>0 f(n) = n! = We may try to write it as: f: n. (if (= n 0) 1 (* n (f (- n 1)))) But f is a free variable that should represent our factorial function. C. Varela 15

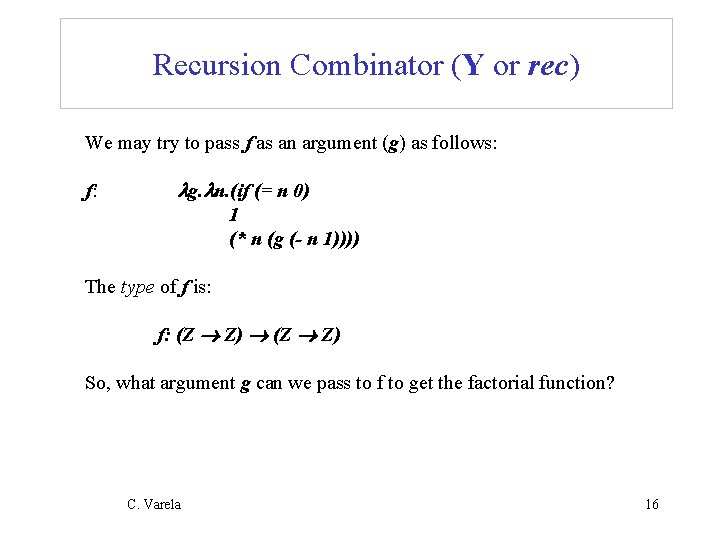

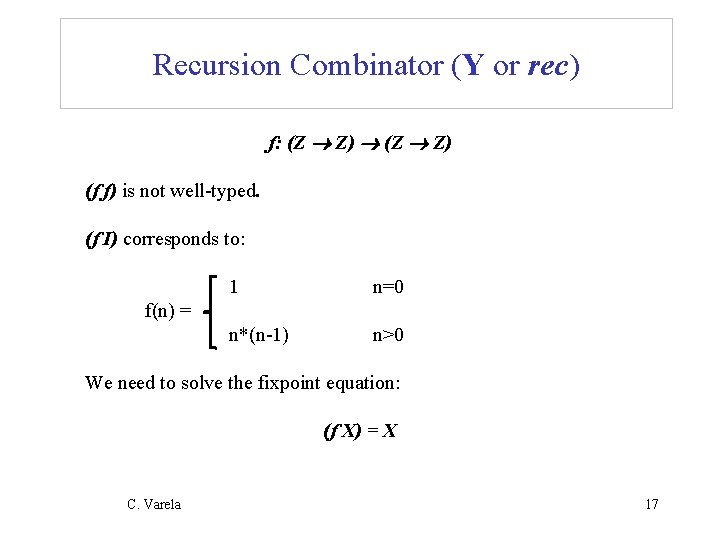

Recursion Combinator (Y or rec) We may try to pass f as an argument (g) as follows: f: g. n. (if (= n 0) 1 (* n (g (- n 1)))) The type of f is: f: (Z Z) So, what argument g can we pass to f to get the factorial function? C. Varela 16

Recursion Combinator (Y or rec) f: (Z Z) (f f) is not well-typed. (f I) corresponds to: 1 n=0 n*(n-1) n>0 f(n) = We need to solve the fixpoint equation: (f X) = X C. Varela 17

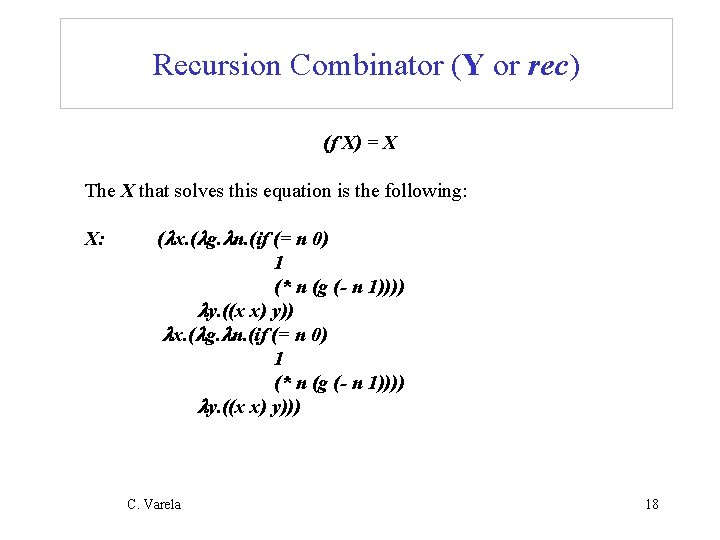

Recursion Combinator (Y or rec) (f X) = X The X that solves this equation is the following: X: ( x. ( g. n. (if (= n 0) 1 (* n (g (- n 1)))) y. ((x x) y))) C. Varela 18

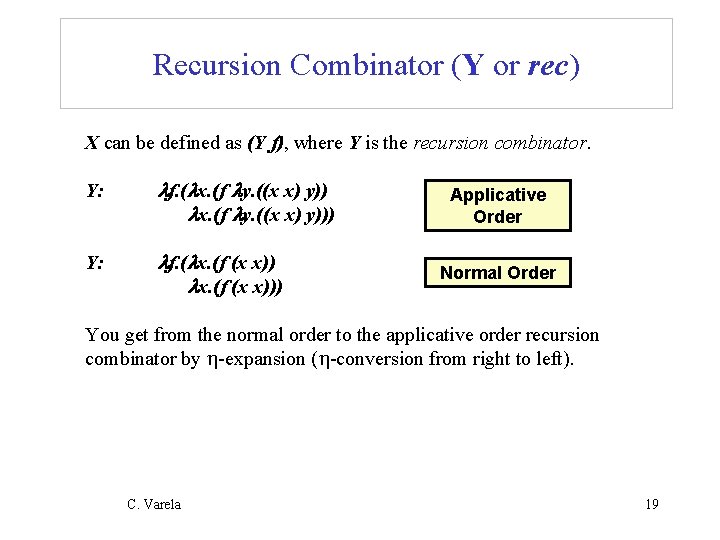

Recursion Combinator (Y or rec) X can be defined as (Y f), where Y is the recursion combinator. Y: f. ( x. (f y. ((x x) y))) Y: f. ( x. (f (x x))) Applicative Order Normal Order You get from the normal order to the applicative order recursion combinator by h-expansion (h-conversion from right to left). C. Varela 19

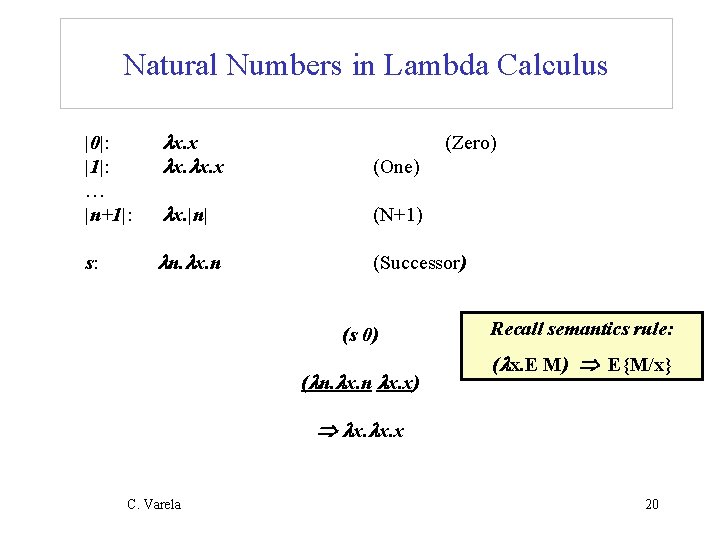

Natural Numbers in Lambda Calculus |0|: |1|: … |n+1|: x. x. x (One) x. |n| (N+1) s: n. x. n (Successor) (Zero) (s 0) ( n. x. n x. x) Recall semantics rule: ( x. E M) E{M/x} x. x. x C. Varela 20

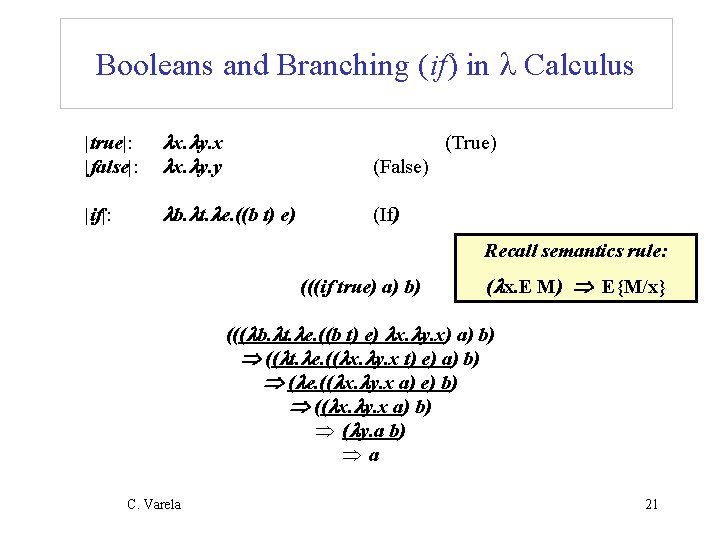

Booleans and Branching (if) in Calculus |true|: |false|: x. y. x x. y. y (False) |if|: b. t. e. ((b t) e) (If) (True) Recall semantics rule: (((if true) a) b) ( x. E M) E{M/x} ((( b. t. e. ((b t) e) x. y. x) a) b) (( t. e. (( x. y. x t) e) a) b) ( e. (( x. y. x a) e) b) (( x. y. x a) b) Þ ( y. a b) Þa C. Varela 21

Exercises 6. PDCS Exercise 2. 11. 7 (page 31). 7. PDCS Exercise 2. 11. 9 (page 31). 8. PDCS Exercise 2. 11. 10 (page 31). 9. PDCS Exercise 2. 11 (page 31). 10. Prove that your addition operation is correct using induction. 11. PDCS Exercise 2. 11. 12 (page 31). Test your representation of booleans in Haskell. C. Varela 22

- Slides: 22