Derivative Instruments Hedging Speculating on Currency Risk Derivatives

- Slides: 58

. Derivative Instruments: Hedging (Speculating on) Currency Risk

Derivatives A derivative is a financial instrument whose price is “derived” in relation to the price of a specified underlying asset. The building blocks of derivative instruments, are futures and forward contracts, and “call” and “put” options.

Derivatives (cont) An intriguing feature of derivatives is that they can be used either to hedge (reduce exposure to an underlying asset) or, alternatively, to magnify a speculative position in relation to the price movement of an underlying asset. A trade in derivatives implies a contract between two parties, who take “opposite” positions on the price of the underlying. The outcome is that the value of the derivative is determined in relation to the positions of two opposite parties so that one party’s gain is the other party’s loss. Thus, derivatives represent a “zero-sum game”.

Forward and future contracts As a farmer, you may be wondering at what price your wheat crop will sell at the end of the harvest. At the same time, the granary that is planning to purchase your wheat is wondering at what price it will have to pay for your wheat. Both parties are aware that an abundance of wheat will lower the price, whereas a shortage will raise the price. Thus, both parties face price uncertainty. The uncertainty between the parties can be reduced if prior to the harvest, both parties agree the price at which they will trade the wheat between them. Such a contract – whereby both parties agree “now” as to both the quantity and price at which a transaction will occur at some given time in the future - constitutes a “forward” contract. In the above example, we can say that both parties have hedged their risk, in that they both have reduced their exposure to a price movement for wheat.

Forward and future contracts (cont) As another example, if I need to purchase a barrel of oil for fuel from my supplier at the end of each month going forward, and we agree on the price today for, say, the next 12 monthly deliveries, we have both entered into a forward contract on the barrel of oil, and, again, both of us have hedged our exposure to oil price uncertainty. ////

Forward and future contracts (cont) Suppose, however, that you and I are arguing as to the price of oil at the end of the month, and we are both seeking to back our hunches with a cash investment. Suppose, I believe that the oil price is about to increase (from, say, a current price of $50. 00/bbl), whereas you strongly believe that it will decline (from $50. 00/bbl). How are we to speculate on our views?

Forward and future contracts (cont) One answer is that we could enter into a forward contact with each other to take place at the end of the month. Basically, I agree to purchase from you X barrels of oil at a price we agree upon today, let us say, at the current price of $50. 00/bbl (since I believe it will be higher, and you believe it will be lower). Furthermore, if we both believe that price change in either direction is unlikely to be more than 5%, and we each have $500 agree to purchase from you – not 10 barrels – with which to speculate, I might but 200 barrels! Let’s see how this works out.

Forward and future contracts (cont) Suppose that at the end of the month the price of oil is $52. 5 a barrel (an increase of 5%) You are now contracted to sell 200 barrels of oil to me at $50 a barrel. In principle, you must purchase the oil at $52. 5 a barrel (costing you $52. 5 x 200 = $10, 500) and sell to me for $50 x 200 = $10, 000, meaning that you suffer a $500 loss. Reciprocally, I can pay you $10, 000 and then sell the oil for $10, 500, giving me a $500 profit. So, the contract is settled by you paying me $500! I have made $500 and you have lost $500.

Forward and future contracts (cont) Suppose, however, that at the end of the month, the price of oil had dropped by, say 5%. Now, I am contracted to purchase from you 200 barrels at $50 a barrel, oil that is only worth $47. 5 a barrel. So, this time, the contract is settled by me paying you $500!

Forward and future contracts (cont) Thus, we see that such a “forward” contract provides a means of leveraging, which is to say, increasing exposure to a position on an underlying asset or instrument. This is because a forward contract allows a speculator to bet on an “underlying” asset (a share, a bond, foreign exchange, etc. ) such that the outcome wealth on the contact position is determined, not by the price value of the underlying as such, but by the change in the price of the underlying from a pre-determined price.

Forward and future contracts (cont) In the above case, we say that we have both speculated on the price of oil. We have entered into the contract naked, meaning that neither of us own nor intend to own barrels of oil! It is exactly such lack of ownership – or lack of intended ownership - that has converted a hedging contract (designed to reduce uncertainty for the party that requires to actually either sell or purchase the underlying at the finalization of the contract – as in the above “wheat” example) into a speculative one.

Forward and future contracts (cont) When such forward arrangements are negotiated between specific parties – for example between a company (perhaps seeking to hedge a potential adverse currency movement on its receivables or payables in another currency) and a bank – the contract is a forward contract. It is termed an “over the counter” arrangement as the details can be negotiated between the two parties (in regard to such as the price, required amount and date of delivery). The understanding, generally, is that the contract will actually be delivered on (for example, a forward arrangement for a currency conversion between a business and its bank will normally lead to the actual transfer of the quoted funds).

Forward and future contracts (cont) Such a contract is also traded in specialized exchanges, when it is referred to as a future contract, as opposed to a “forward” contract. Originally, trading was carried on through open yelling and hand signals in a trading pit. Now, as for most other markets, futures exchanges are mostly electronic. The most important market foreign currency futures is the International Monetary Market (IMM), a division of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). To reduce the complexity of offerings – as well as to ensure that the outcome trading products are “liquid” (meaning that buyers and sellers are reliably available) - futures are traded in standardized amounts and dates for delivery.

Forward and future contracts (cont) For futures contacted through an exchange, the contract is rarely delivered upon, meaning that the underlying is not actually traded (in the same way that our above barrels of oil forward contract did not lead to a physical exchange of oil). Instead, both parties must deposit cash as collateral in a bank account with the exchange to ensure that the party that “loses out” is able to honour its cash obligations. This “margin” requirement is marked to market on a daily basis. If the amount becomes insufficient at the current price to cover one party’s losses, that party will receive a “margin call” from the exchange requesting that additional funds be placed in the person’s account. Failure to comply leads to the contract being closed out at the current price.

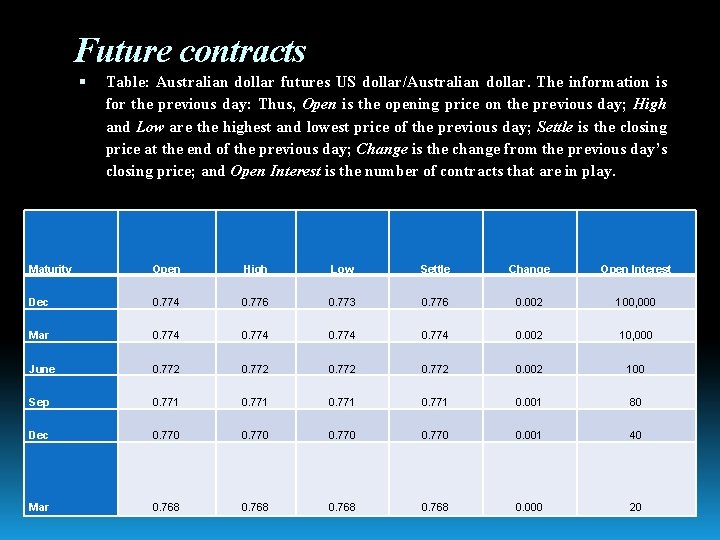

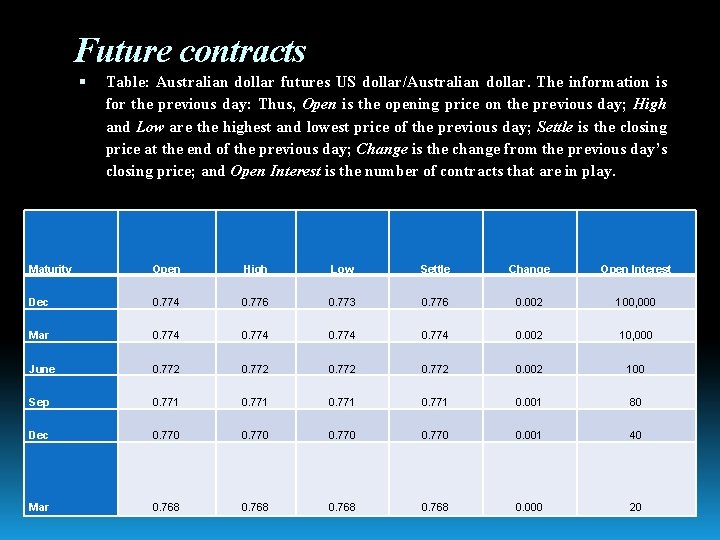

Future contracts Table: Australian dollar futures US dollar/Australian dollar. The information is for the previous day: Thus, Open is the opening price on the previous day; High and Low are the highest and lowest price of the previous day; Settle is the closing price at the end of the previous day; Change is the change from the previous day’s closing price; and Open Interest is the number of contracts that are in play. Maturity Open High Low Settle Change Open Interest Dec 0. 774 0. 776 0. 773 0. 776 0. 002 100, 000 Mar 0. 774 0. 002 10, 000 June 0. 772 0. 002 100 Sep 0. 771 0. 001 80 Dec 0. 770 0. 001 40 Mar 0. 768 0. 000 20

Break time

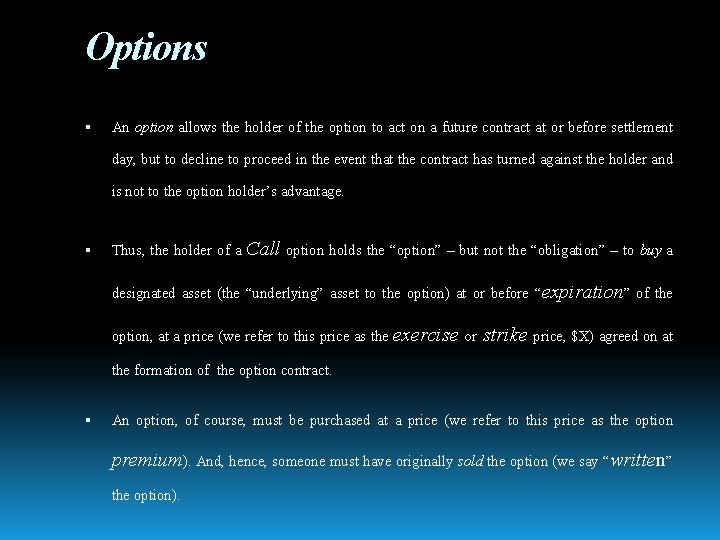

Options An option allows the holder of the option to act on a future contract at or before settlement day, but to decline to proceed in the event that the contract has turned against the holder and is not to the option holder’s advantage. Thus, the holder of a Call option holds the “option” – but not the “obligation” – to buy a designated asset (the “underlying” asset to the option) at or before “expiration” of the option, at a price (we refer to this price as the exercise or strike price, $X) agreed on at the formation of the option contract. An option, of course, must be purchased at a price (we refer to this price as the option premium). And, hence, someone must have originally sold the option (we say “written” the option).

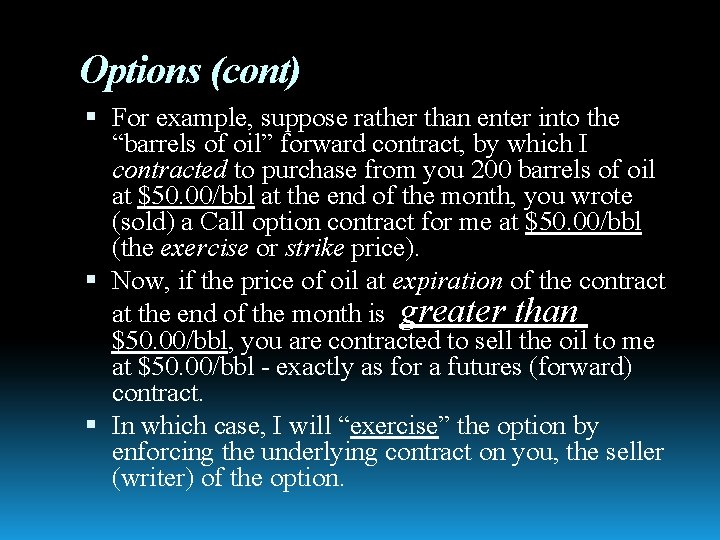

Options (cont) For example, suppose rather than enter into the “barrels of oil” forward contract, by which I contracted to purchase from you 200 barrels of oil at $50. 00/bbl at the end of the month, you wrote (sold) a Call option contract for me at $50. 00/bbl (the exercise or strike price). Now, if the price of oil at expiration of the contract at the end of the month is greater than $50. 00/bbl, you are contracted to sell the oil to me at $50. 00/bbl - exactly as for a futures (forward) contract. In which case, I will “exercise” the option by enforcing the underlying contract on you, the seller (writer) of the option.

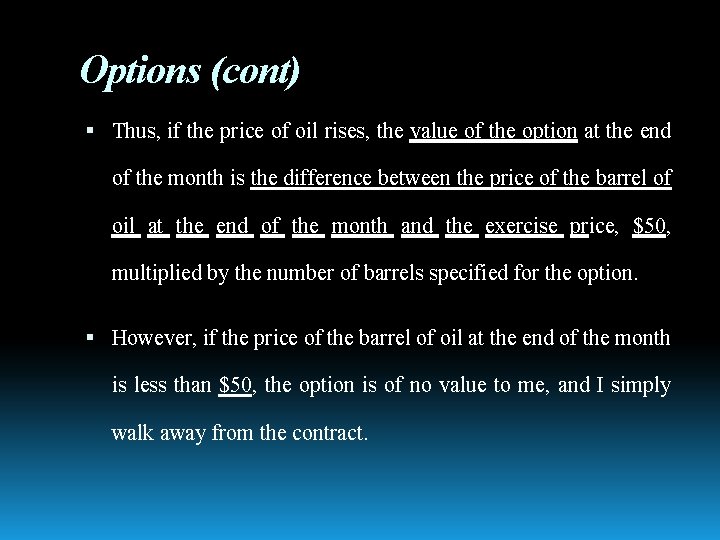

Options (cont) Thus, if the price of oil rises, the value of the option at the end of the month is the difference between the price of the barrel of oil at the end of the month and the exercise price, $50, multiplied by the number of barrels specified for the option. However, if the price of the barrel of oil at the end of the month is less than $50, the option is of no value to me, and I simply walk away from the contract.

Options (cont) Of course, you do not write the option for me for nothing. Maybe I purchased the above Call option from you at, say, $1. 50 a barrel. What is the implication? Basically, the price of a barrel of oil has to rise to $51. 50 before I break even. Why? Because at $51. 50 a barrel, my option obliges you to pay me: $51. 50 - $50 = $1. 50 f or each barrel of option contract, which cancels with the $1. 50 price per barrel of option contract that I paid you so as to hold the option. Above $51. 50/bbl, I, as the holder of the option, make a profit. Below $51. 50/bbl, you, the seller (writer) of the option makes a profit.

Options : Put options The holder of a Put option similarly holds the option, but not the obligation, to sell the underlying asset at the exercise or strike price, $X. In summary, the value of Call (Put) option is derived from the upward (downward) difference in the price of the underlying asset from the exercise price.

Options (cont) An option whose exercise price is the same as the spot price of the underlying is said to be at-themoney (ATM), whereas a Call (Put) option for which the exercise price is less (greater) than the current price is said to be in-the-money (ITM), and a Call (Put) option for which the exercise price is greater (less) than the current price is said to be out-of-the money (OTM). The option is termed “European” if the option can be “exercised” only at the specified settlement day (at “expiration” of the option), whereas the option is termed “American” if it can be exercised at any time in the intervening period.

Options (cont) Contract specifications for options are standardized for contract size, exercise price, maturity date, and premiums, as well as collateral and maintenance margins, and commissions. Again, as for futures (forwards), the instruments can be used for two very distinct management objectives: speculation – to “take a position” in the expectation of a profit, or hedging – to reduce the risk associated with business arrangements.

Options (cont) As for futures (forwards), options are a “zero-sum” game in that the speculative gain to a holder of the option at expiry is forthcoming at the expense of the original seller or “writer” of the option. The holder of the option cannot be made liable for any additional payment after purchase of the option. But, every cent of movement of the underlying price from the exercise price in the option holder’s favor implies a cent of additional profit for the option holder, which is multiplied by the quantity of the underlying that the option holder has an option on. On the other hand, the writer who writes (sells) the option gains by receiving the premium (price) for the option and thereafter anticipates that the option will either remain unexercised (ideally) or be exercised within the premium price range from the exercise price. The maximum gain to the option writer is therefore the option premium (the purchase price received). The potential loss is, of course, the potential gain to the option holder, as just described. //////

Options on currencies With currencies, a potential for confusion is that of deciding which of the two currencies is the “foreign” currency, and which is the currency with which one purchases or sells the option contract. To avoid confusion, when dealing with options for currencies, it is always a good idea to consider first of all, where is the exchange you are trading through. If it is in the US, for example, all options are bought and sold in US dollars, and the other currency - the “foreign” currency - can be visualized as the asset or “thing” (we sometimes say, “commodity”) that is being bought or sold.

Options on currencies (cont) The quotes foreign currencies in the options markets are generally direct quotes, meaning that in Chicago, for example, the quotes are displayed as US$ per unit of foreign currency. For example, the peso is trading at $1. 3 per peso. In fact, as we shall see, adhering to direct quotes makes the calculations fall readily into place. Thus, even if you were a European person trading Euros in Chicago, and seeking to assess your potential profit or loss in Euros as the exchange rate outcome at expiration of the option, it still works out simpler to perform the calculations in US dollars and convert to Euro as a final conversion.

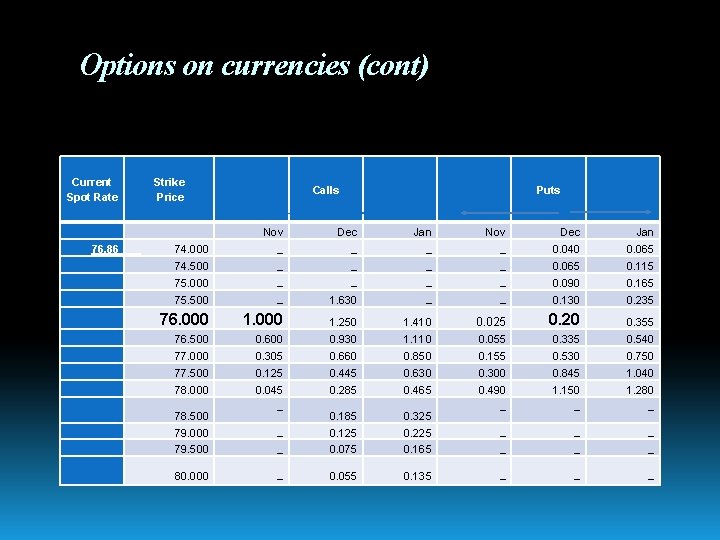

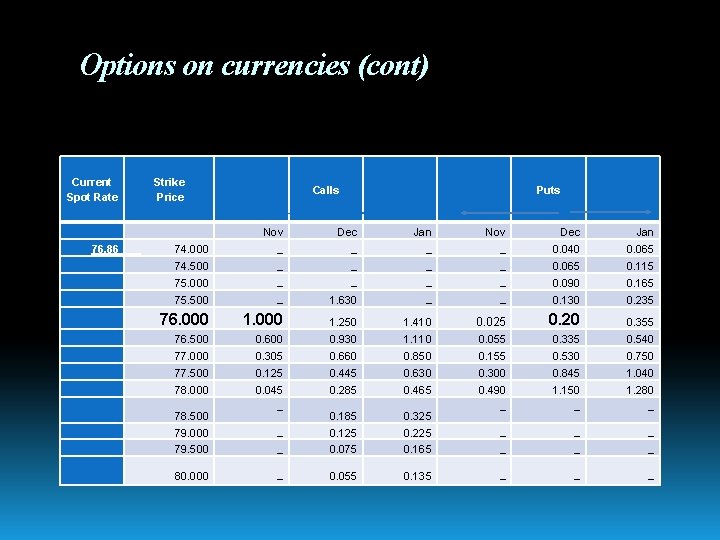

Options on currencies (cont) Current Spot Rate 76. 86 Strike Price Calls Puts Dec _ Jan _ Nov _ Dec Jan 74. 000 Nov _ 0. 040 0. 065 74. 500 _ _ 0. 065 0. 115 75. 000 _ _ 0. 090 0. 165 75. 500 _ 1. 630 _ _ 0. 130 0. 235 76. 000 1. 250 1. 410 0. 025 0. 20 0. 355 76. 500 0. 600 0. 930 1. 110 0. 055 0. 335 0. 540 77. 000 0. 305 0. 660 0. 850 0. 155 0. 530 0. 750 77. 500 0. 125 0. 445 0. 630 0. 300 0. 845 1. 040 78. 000 0. 045 _ 0. 285 0. 465 0. 185 0. 325 0. 490 _ 1. 150 _ 1. 280 _ 79. 000 _ 0. 125 0. 225 _ _ _ 79. 500 _ 0. 075 0. 165 _ _ _ 80. 000 _ 0. 055 0. 135 _ _ _ 78. 500

Options on currencies – a Call option Suppose, for example, we decide to purchase a November Call option on the Australian dollar with a strike price of 76 cents per Aussie dollar, at a premium, or cost of the option, of 1. 0 US cent per Aussie dollar (as depicted in the above table). What does this mean?

Options on currencies – a Call option The strike price means that at expiration of the Call option at the end of November, we hold the option (but not the obligation) of purchasing 1 Aussie dollar for 76 US cents. If at expiration, the Aussie dollar (for example, at 73 US cents) is worth less than the price at which it can be purchased (76 US cents), the option is out of the money – since there can be little advantage in purchasing the Aussie dollar at a price of 76 US cents if it can be purchased for 73 cents in the market place. However, if the Aussie dollar turns out, for example, to be worth 78 US cents, it is worth more than 76 US cents, and there is therefore a definite advantage in purchasing the item at 76 US cents. At the time of Table 11. 2, our option with a strike price of 76 cents to the Aussie dollar is in the money – since I can purchase the Aussie dollar (which is currently trading at 76. 86 cents to the Aussie dollar) for 76 cents.

Options on currencies – a Call option So how do we calculate our profit or loss? If the price of the Aussie at expiration is less than the option price, the calculation is simple - we have lost all our money – which, in this case, was 1. 0 US cent for an option on a single Aussie dollar. If the option contract we purchased was for an option on 10, 000 Aussie dollars, the cost of our purchase would have been 10, 000 x 1 US cent = $100.

Options on currencies – a Call option Suppose the good news is that our option is in the money – let us say the Aussie dollar has a market price of 78 US cents per dollar. The implication is that we can purchase an Aussie dollar that is now worth 78 US cents for only 76 US cents (the exercise price for the option). A profit of 2 cents. As we had an option contract to purchases 10, 000 Aussies, our option contract is worth $200. But we should bear in mind that the cost of the option was 1. 0 US cent per option on a single Aussie dollar. We calculated this above as 10, 000 x 1. 0 US cents = $100. Our profit therefore is not $200, but $200 - $100 = $100.

Options on currencies – a Call option More generally, we can say that our profit on our Call option on a single Aussie dollar is the market price in US dollars per Aussie dollar minus the price at which we are able to purchase a single Aussie dollar with our option (the exercise price) minus the cost of purchase of an option on a single Aussie dollar (the premium price).

Options on currencies – a Call option In other words, we have: Profit for a Call option on the Aussie dollar (provided the outcome price of an Aussie dollar is greater than the exercise/strike price) in US dollars per option on a single Aussie dollar is determined as: outcome price of an Aussie dollar (US $ per Aussie dollar) – exercise price for one Aussie dollar (US $ per Aussie dollar) – price (premium) for an option on a single Aussie dollar (US $) (11. 1) which is then multiplied by the number of Australian dollars for which we hold the option.

Options on currencies – a Call option As another example, if the outcome rate is 77. 5 US cents per Aussie, our profit would be Profit = (77. 5 – 76. 0 – 1. 0) x 10, 000 (cents) = 5, 000 cents = $50. 0 We observe that our profit on the option is “cent for cent” above the exercise price, meaning that each US cent by which the price of the Aussie strengthens above the exercise price, equates with an additional US cent “in our pocket”, multiplied by the number of Aussie dollars on which we have an option.

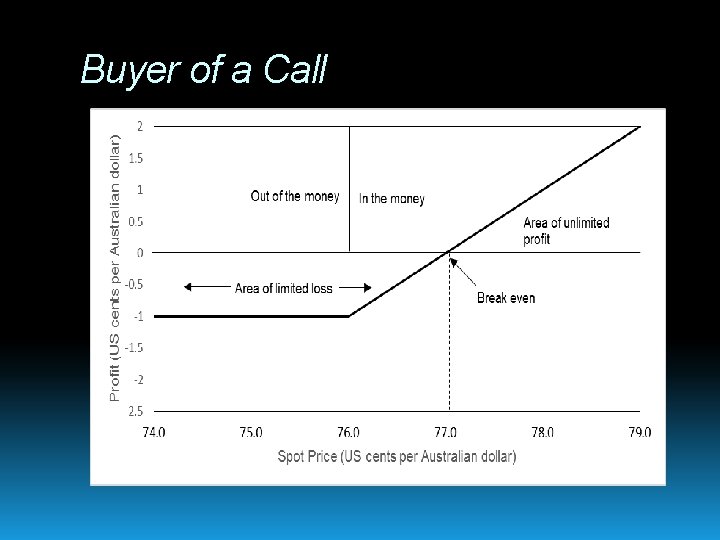

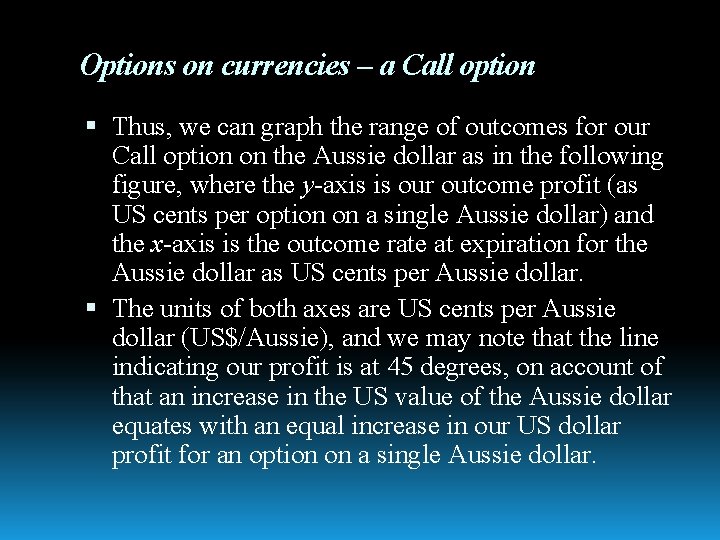

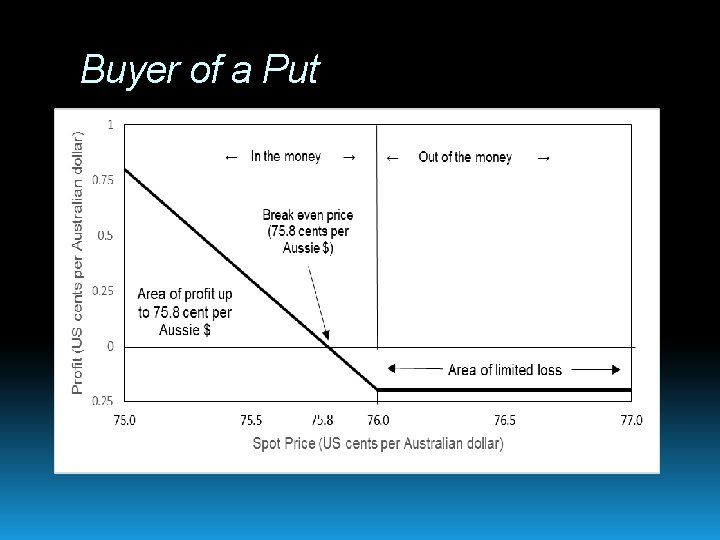

Options on currencies – a Call option Thus, we can graph the range of outcomes for our Call option on the Aussie dollar as in the following figure, where the y-axis is our outcome profit (as US cents per option on a single Aussie dollar) and the x-axis is the outcome rate at expiration for the Aussie dollar as US cents per Aussie dollar. The units of both axes are US cents per Aussie dollar (US$/Aussie), and we may note that the line indicating our profit is at 45 degrees, on account of that an increase in the US value of the Aussie dollar equates with an equal increase in our US dollar profit for an option on a single Aussie dollar.

Buyer of a Call

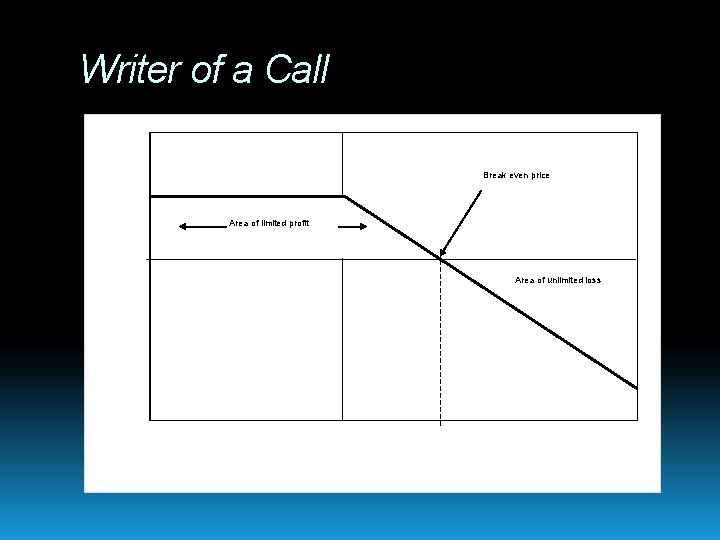

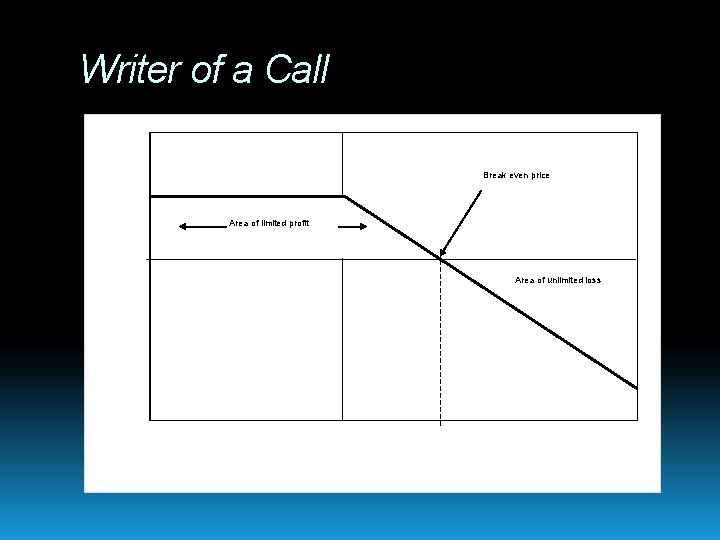

Options on currencies – writing a Call option Suppose that rather than purchasing a Call option as in the last example, we had chosen to “write” (sell) the above Call option (a Call option to purchase 10, 000 Aussie dollar at 76 cents, at a premium of 1 cent per Aussie dollar). The zero sum nature of options means that our gain or loss must come from the investor (which was “us” in the previous example) who purchases the option. In other words, the option holder’s loss/gain becomes the gain/loss for the writer of the option. See following figure

Writer of a Call 2 1, 5 Profit (US cents per Australian dollar) Break even price 1 0, 5 Area of limited profit 0 Area of unlimited loss -0, 5 -1 -1, 5 -2 -2, 5 74, 0 75, 0 76, 0 77, 0 Spot Price (US cents per Australian dollar) 78, 0 79, 0

Options on currencies – a Put option In contrast with the holder of a Call option, the holder of a Put option seeks to be able to sell (‘put’) the underlying currency at a price (the exercise price, for example, $76 cents per Aussie dollar) that exceeds the currency’s actual worth. Thus, the holder of a Put option benefits when the foreign currency loses value. For example, if the price of the Aussie dollar drops to US$ 0. 7400/A$, the holder of the November Put option is able to sell (‘put’) the Aussie dollar on the writer of the Put for 76 cents, which is to say, for 2 cents more than it is worth.

Options on currencies – a Put option In principle, as the holder of the Put, we could purchase the Aussie dollar for 74 cents in the market and sell it to the writer of the Put for 76 cents, who might then dispose of it in the market for 74 cents. Thus, we see that the Put (per option on a single Aussie dollar) is worth 1 cent for every cent that the Aussie drops below 76 US cents. Of course, if the Aussie dollar is 76 cents or higher, the Put is worthless. .

Options on currencies – a Put option In other words, we have: Profit for a Put option on the Aussie dollar (provided the outcome price of an Aussie dollar is less than the exercise/strike price) in US dollars per option on a single Aussie dollar: is determined as: exercise (strike) price for one Aussie dollar (US $ per Aussie dollar) – outcome price of an Aussie dollar (US $ per Aussie dollar) – price (premium) for an option on a single Aussie dollar (US $) (11. 2) which is then multiplied by the number of Aussie dollars for which we hold the option.

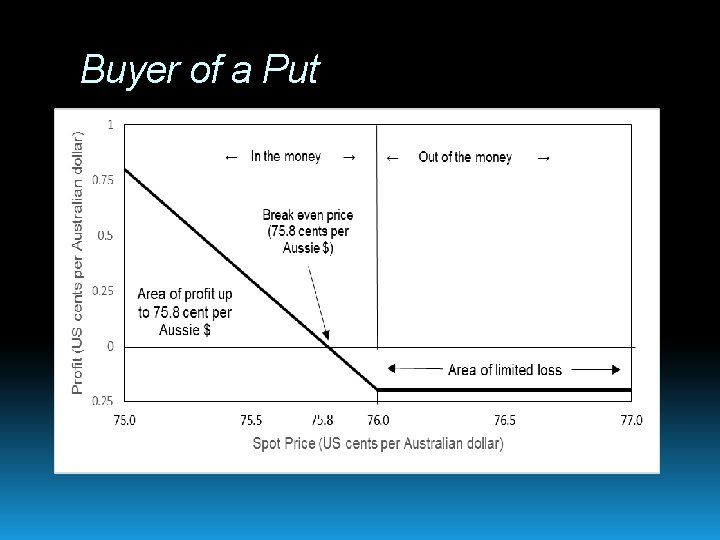

Options on currencies – a Put option In the above table, the premium price we had to pay for the December put option was 0. 2 cents for an option on each Aussie dollar. Thus, if the outcome price is US 73. 0 cents per Aussie dollar, our profit would be: Profit = (76 – 0. 2 – 73) x 10, 000 (cents) = $280. 0 The range of possible outcomes is depicted in the figure over.

Buyer of a Put

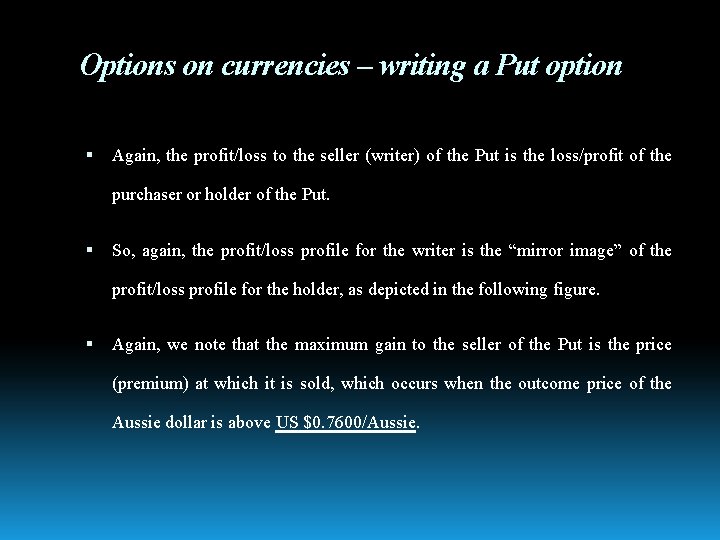

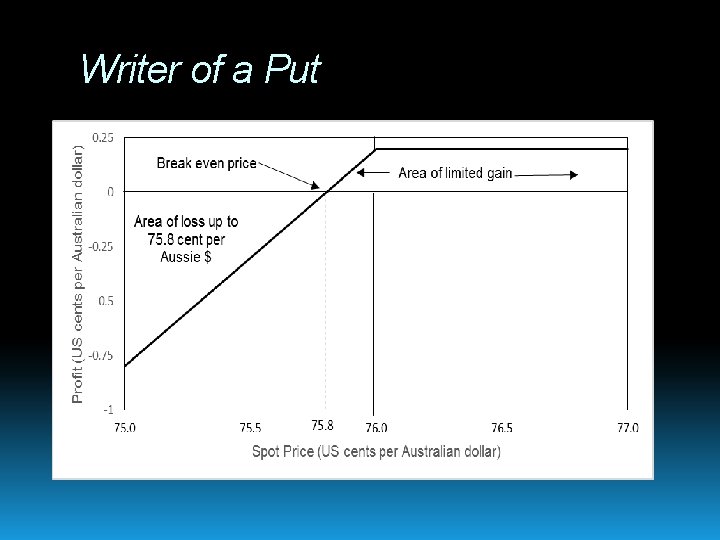

Options on currencies – writing a Put option Again, the profit/loss to the seller (writer) of the Put is the loss/profit of the purchaser or holder of the Put. So, again, the profit/loss profile for the writer is the “mirror image” of the profit/loss profile for the holder, as depicted in the following figure. Again, we note that the maximum gain to the seller of the Put is the price (premium) at which it is sold, which occurs when the outcome price of the Aussie dollar is above US $0. 7600/Aussie.

Writer of a Put

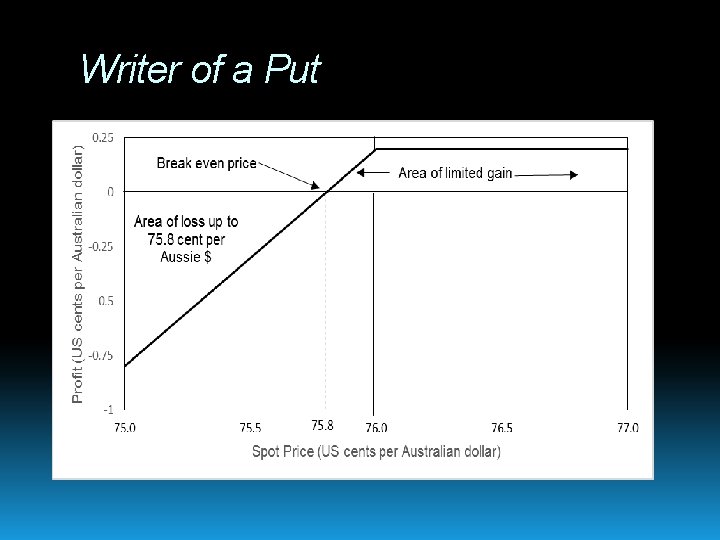

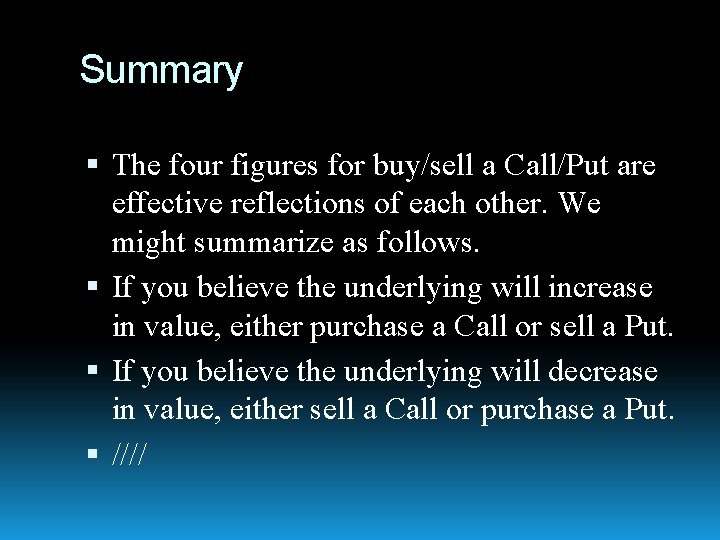

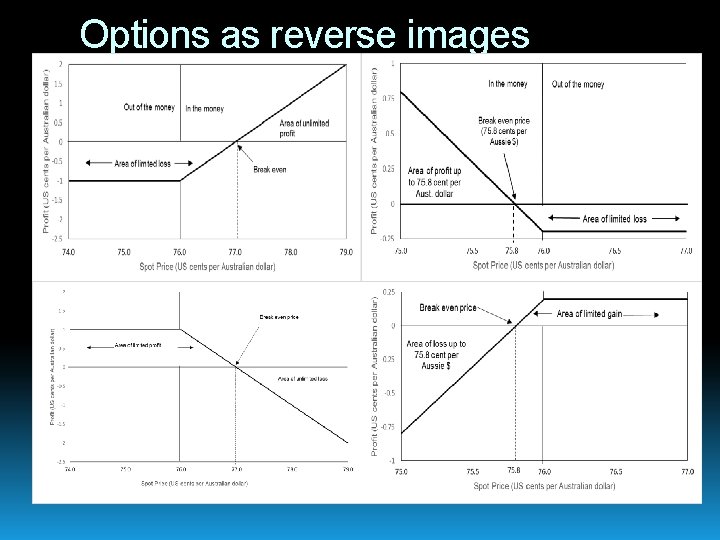

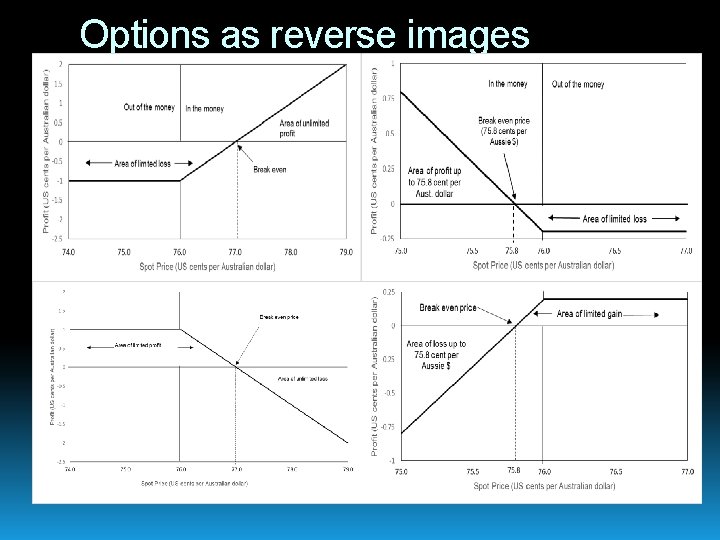

Summary The four figures for buy/sell a Call/Put are effective reflections of each other. We might summarize as follows. If you believe the underlying will increase in value, either purchase a Call or sell a Put. If you believe the underlying will decrease in value, either sell a Call or purchase a Put. ////

Options as reverse images

Break time

Hedging transactional exposure with options A company’s transactional exposures, as either the future receiving of a foreign currency for services or goods sold to an overseas purchaser, or the future obligation to pay a foreign currency for purchase of goods or services to an over-seas supplier, can be hedged effectively in the futures (forwards) and option markets.

Hedging “money receivable” Company Rocky in the US is a designer of Japanese -style gardens designed to require minimal maintenance. Rocky has concluded a contract with Marciano in Italy, the outcome of which is that a payment of € 10, 000 will be received by Rocky in twelve months. The following data is available.

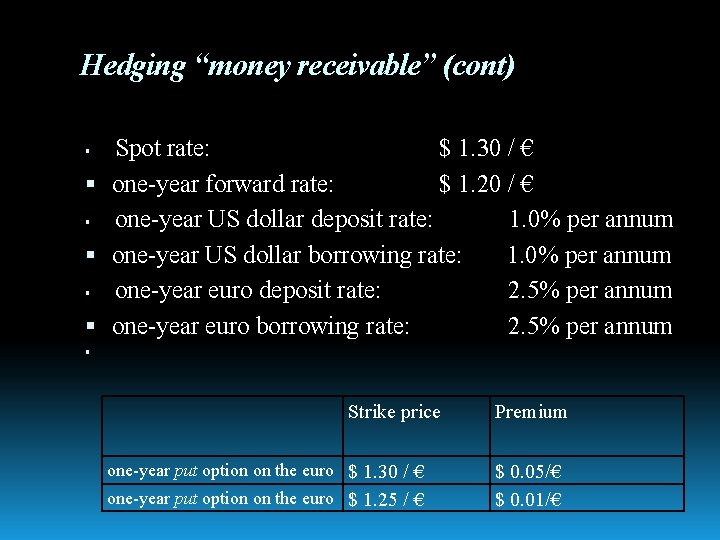

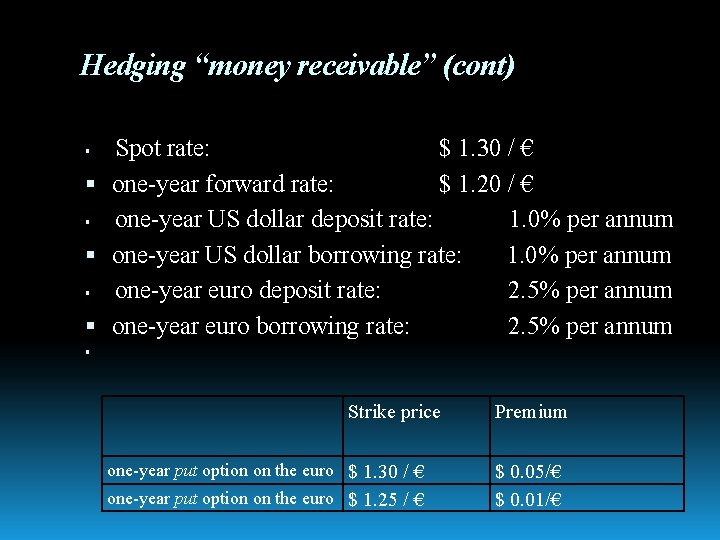

Hedging “money receivable” (cont) Spot rate: $ 1. 30 / € one-year forward rate: $ 1. 20 / € one-year US dollar deposit rate: 1. 0% per annum one-year US dollar borrowing rate: 1. 0% per annum one-year euro deposit rate: 2. 5% per annum one-year euro borrowing rate: 2. 5% per annum Strike price one-year put option on the euro $ 1. 30 / € one-year put option on the euro $ 1. 25 / € Premium $ 0. 05/€ $ 0. 01/€

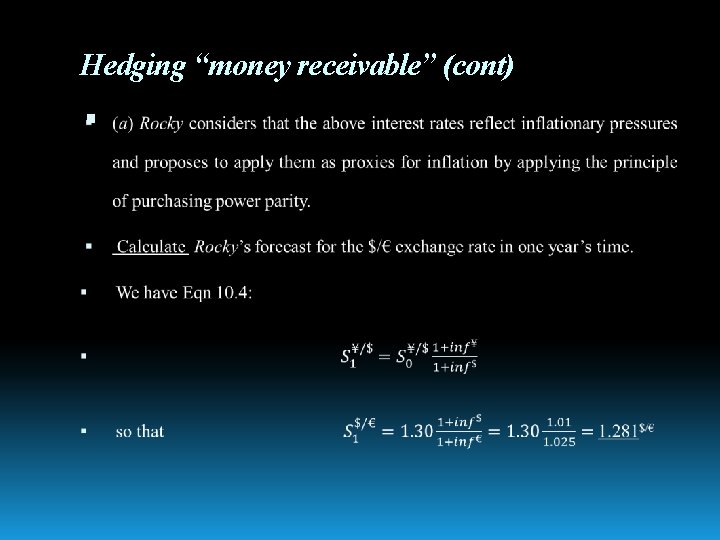

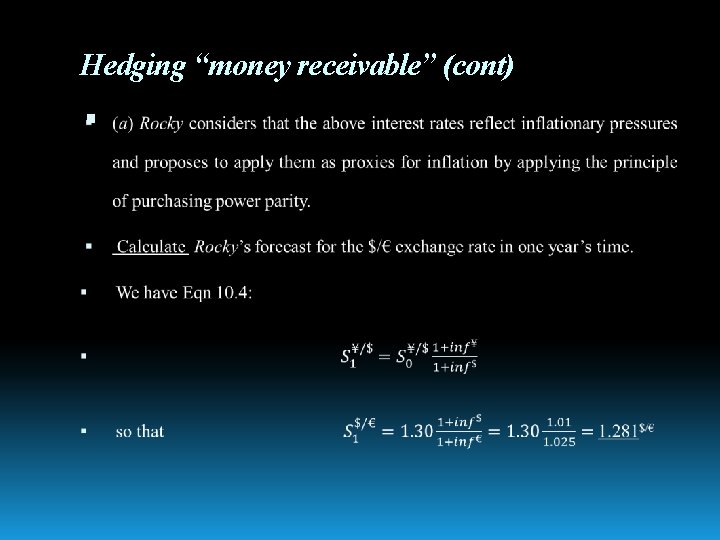

Hedging “money receivable” (cont)

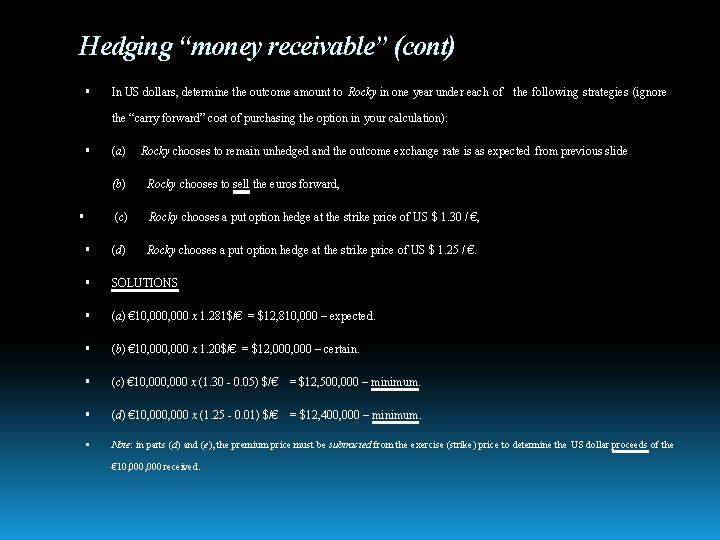

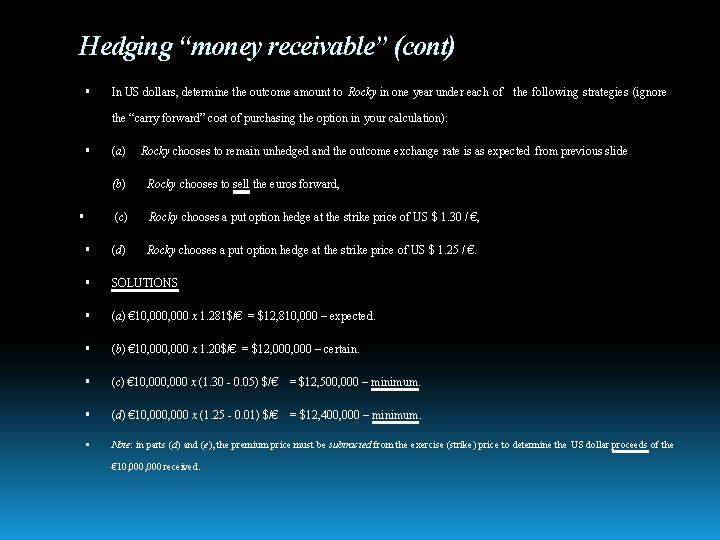

Hedging “money receivable” (cont) In US dollars, determine the outcome amount to Rocky in one year under each of the following strategies (ignore the “carry forward” cost of purchasing the option in your calculation): (a) Rocky chooses to remain unhedged and the outcome exchange rate is as expected from previous slide (b) Rocky chooses to sell the euros forward, (c) Rocky chooses a put option hedge at the strike price of US $ 1. 30 / €, (d) Rocky chooses a put option hedge at the strike price of US $ 1. 25 / €. SOLUTIONS (a) € 10, 000 x 1. 281$/€ = $12, 810, 000 – expected. (b) € 10, 000 x 1. 20$/€ = $12, 000 – certain. (c) € 10, 000 x (1. 30 - 0. 05) $/€ = $12, 500, 000 – minimum. (d) € 10, 000 x (1. 25 - 0. 01) $/€ = $12, 400, 000 – minimum. Note: in parts (d) and (e), the premium price must be subtracted from the exercise (strike) price to determine the US dollar proceeds of the € 10, 000 received.

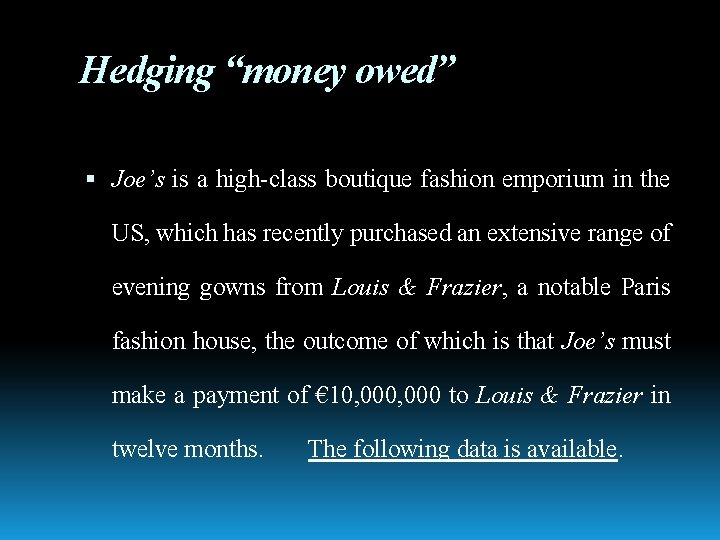

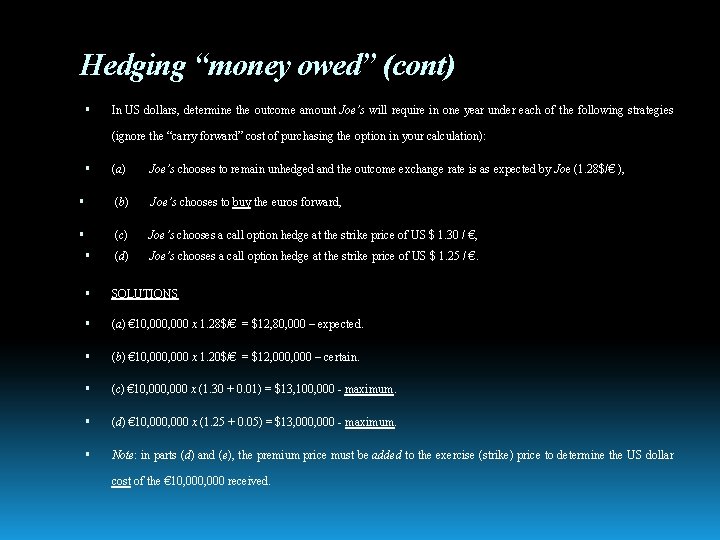

Hedging “money owed” Joe’s is a high-class boutique fashion emporium in the US, which has recently purchased an extensive range of evening gowns from Louis & Frazier, a notable Paris fashion house, the outcome of which is that Joe’s must make a payment of € 10, 000 to Louis & Frazier in twelve months. The following data is available.

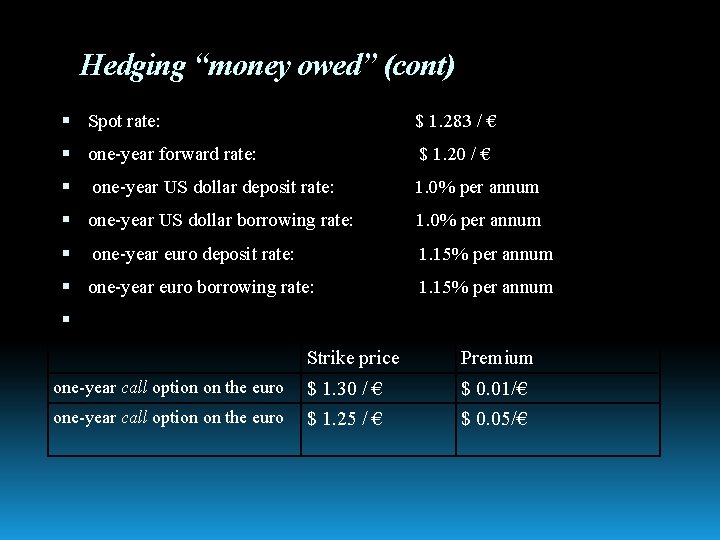

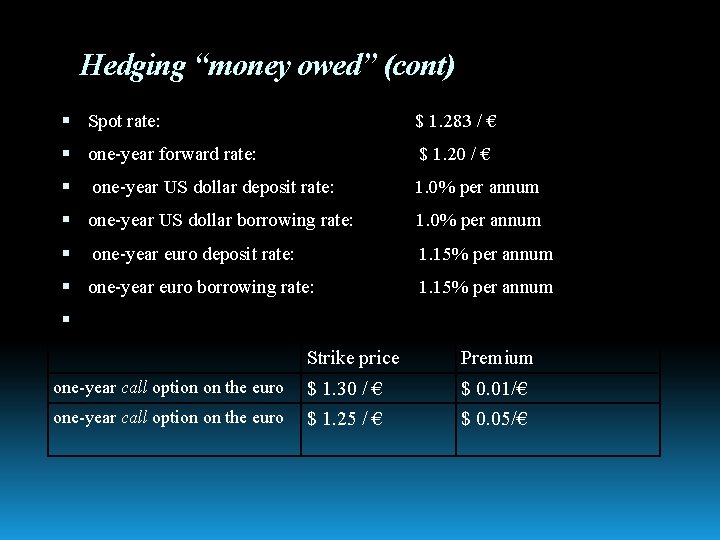

Hedging “money owed” (cont) Spot rate: $ 1. 283 / € one-year forward rate: $ 1. 20 / € one-year US dollar deposit rate: one-year US dollar borrowing rate: one-year euro deposit rate: 1. 0% per annum 1. 15% per annum one-year euro borrowing rate: 1. 15% per annum one-year call option on the euro Strike price Premium $ 1. 30 / € $ 1. 25 / € $ 0. 01/€ $ 0. 05/€

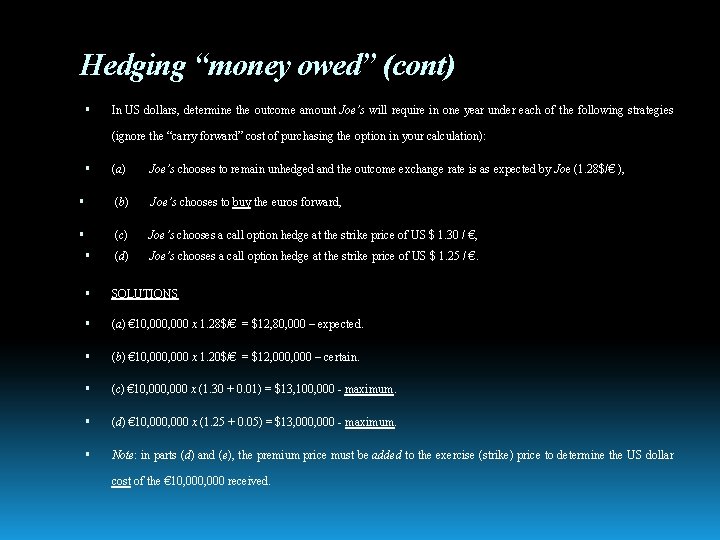

Hedging “money owed” (cont) In US dollars, determine the outcome amount Joe’s will require in one year under each of the following strategies (ignore the “carry forward” cost of purchasing the option in your calculation): (a) Joe’s chooses to remain unhedged and the outcome exchange rate is as expected by Joe (1. 28$/€ ), (b) Joe’s chooses to buy the euros forward, (c) Joe’s chooses a call option hedge at the strike price of US $ 1. 30 / €, (d) Joe’s chooses a call option hedge at the strike price of US $ 1. 25 / €. SOLUTIONS (a) € 10, 000 x 1. 28$/€ = $12, 80, 000 – expected. (b) € 10, 000 x 1. 20$/€ = $12, 000 – certain. (c) € 10, 000 x (1. 30 + 0. 01) = $13, 100, 000 - maximum. (d) € 10, 000 x (1. 25 + 0. 05) = $13, 000 - maximum. Note: in parts (d) and (e), the premium price must be added to the exercise (strike) price to determine the US dollar cost of the € 10, 000 received.

Summary of hedging scenarios Both futures and options (call and puts) can be used to hedge currency risk. The two main “scenarios” are (a) the firm wishes to hedge a future cash income (due to overseas sales) denominated in a foreign currency, and (b) the firm wishes to hedge a future cash obligation (due to overseas purchases) denominated in a foreign currency.