David Helfgott plays Rachmaninov Piano Concerto 3 Copenhagen

- Slides: 47

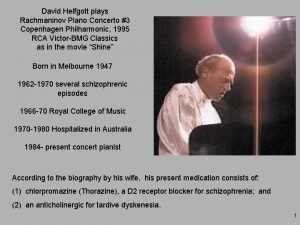

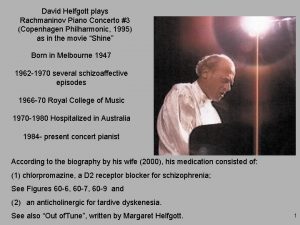

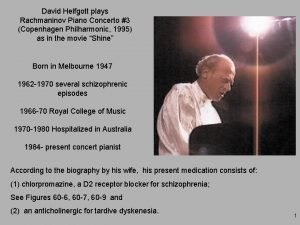

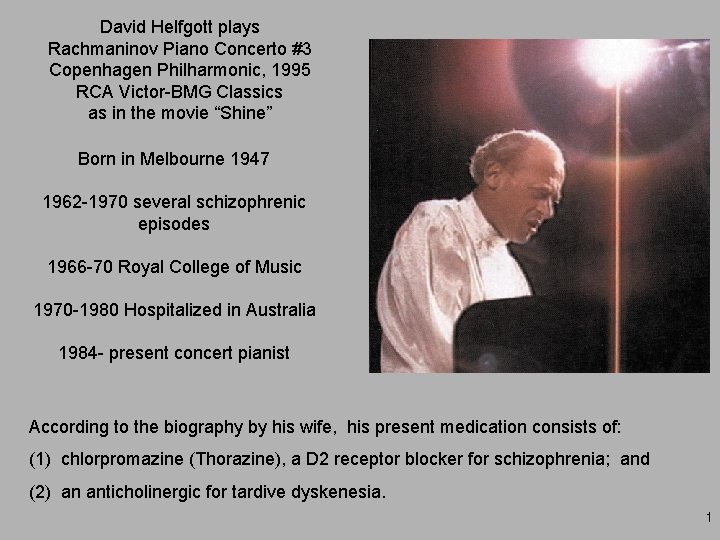

David Helfgott plays Rachmaninov Piano Concerto #3 Copenhagen Philharmonic, 1995 RCA Victor-BMG Classics as in the movie “Shine” Born in Melbourne 1947 1962 -1970 several schizophrenic episodes 1966 -70 Royal College of Music 1970 -1980 Hospitalized in Australia 1984 - present concert pianist According to the biography by his wife, his present medication consists of: (1) chlorpromazine (Thorazine), a D 2 receptor blocker for schizophrenia; and (2) an anticholinergic for tardive dyskenesia. 1

Bi 1 “Drugs and the Brain” Lecture 23 Tuesday, May 16, 2006 Schizophrenia, a cognitive disorder; Depression, a mood disorder 2

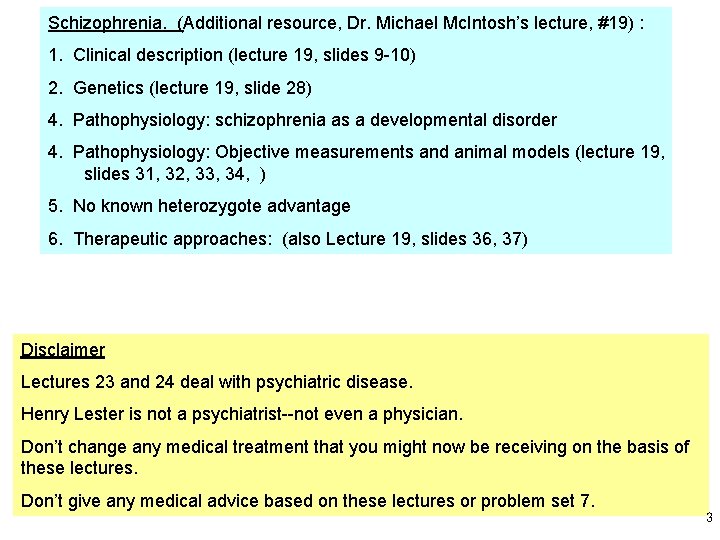

Schizophrenia. (Additional resource, Dr. Michael Mc. Intosh’s lecture, #19) : 1. Clinical description (lecture 19, slides 9 -10) 2. Genetics (lecture 19, slide 28) 4. Pathophysiology: schizophrenia as a developmental disorder 4. Pathophysiology: Objective measurements and animal models (lecture 19, slides 31, 32, 33, 34, ) 5. No known heterozygote advantage 6. Therapeutic approaches: (also Lecture 19, slides 36, 37) Disclaimer Lectures 23 and 24 deal with psychiatric disease. Henry Lester is not a psychiatrist--not even a physician. Don’t change any medical treatment that you might now be receiving on the basis of these lectures. Don’t give any medical advice based on these lectures or problem set 7. 3

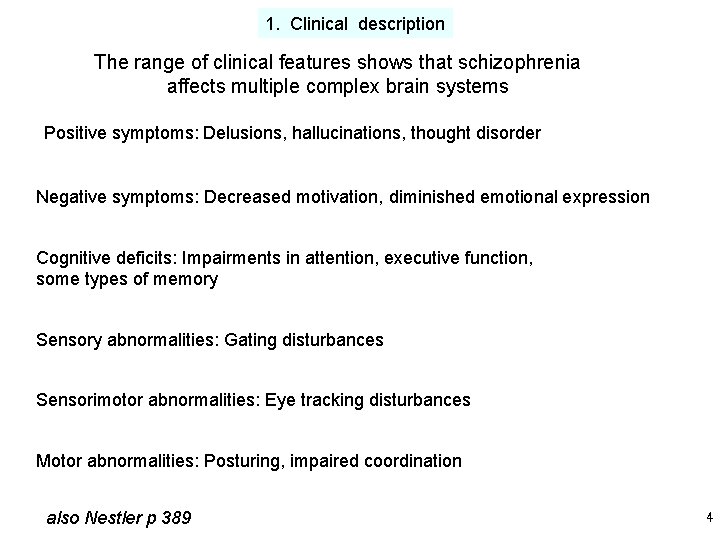

1. Clinical description The range of clinical features shows that schizophrenia affects multiple complex brain systems Positive symptoms: Delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder Negative symptoms: Decreased motivation, diminished emotional expression Cognitive deficits: Impairments in attention, executive function, some types of memory Sensory abnormalities: Gating disturbances Sensorimotor abnormalities: Eye tracking disturbances Motor abnormalities: Posturing, impaired coordination also Nestler p 389 4

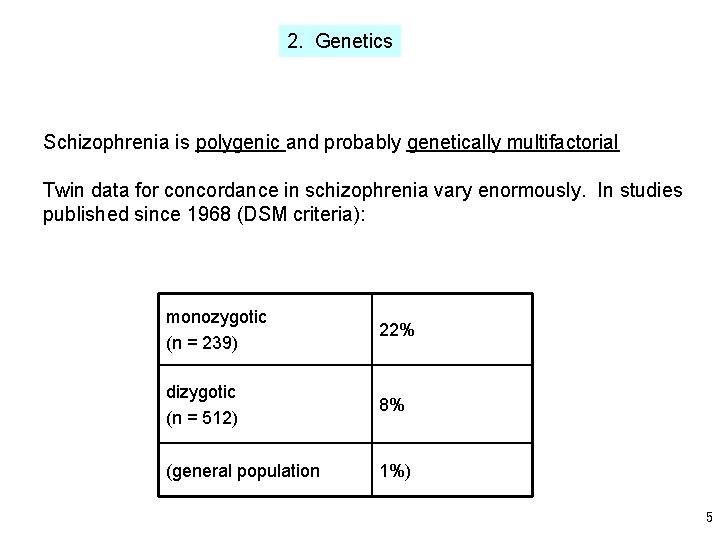

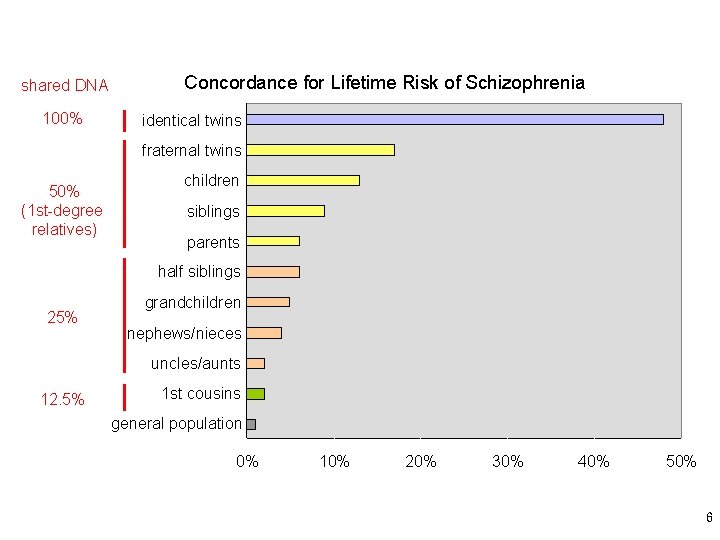

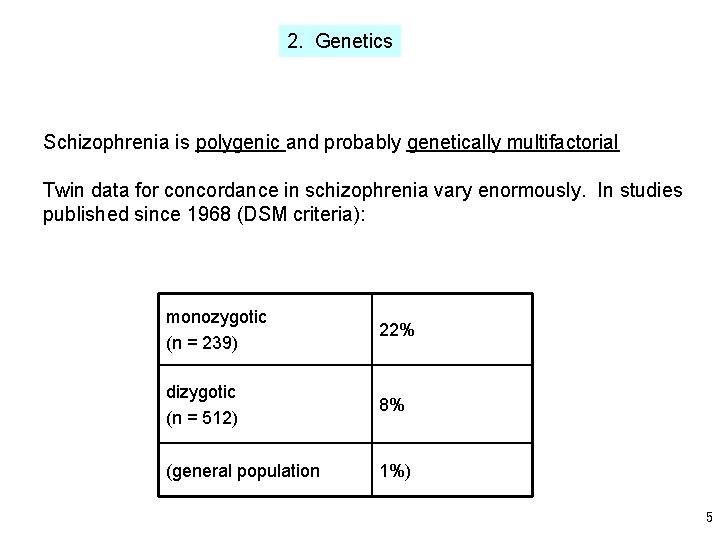

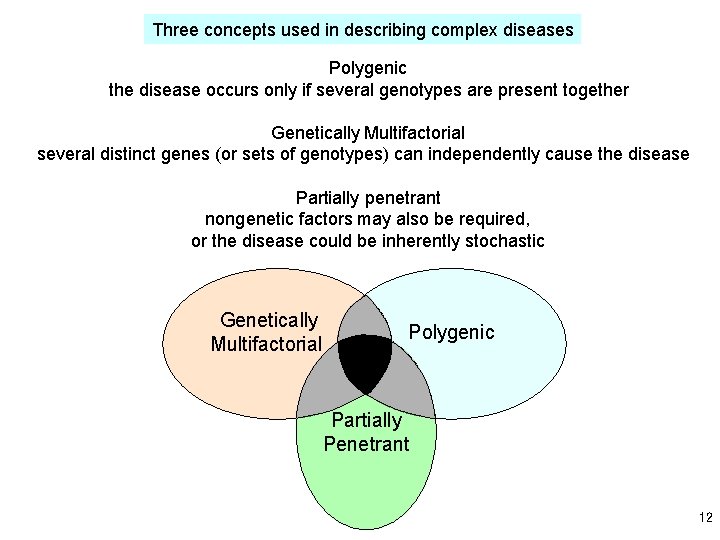

2. Genetics Schizophrenia is polygenic and probably genetically multifactorial Twin data for concordance in schizophrenia vary enormously. In studies published since 1968 (DSM criteria): monozygotic (n = 239) 22% dizygotic (n = 512) 8% (general population 1%) 5

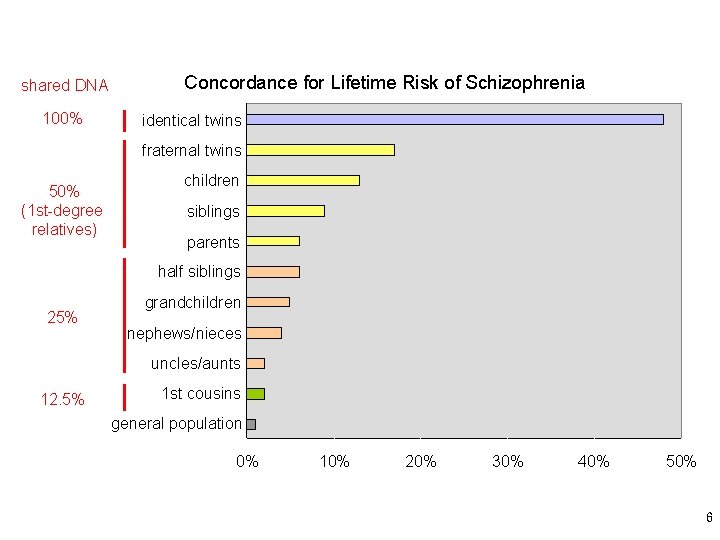

shared DNA 100% Concordance for Lifetime Risk of Schizophrenia identical twins fraternal twins 50% (1 st-degree relatives) children siblings parents half siblings 25% grandchildren nephews/nieces uncles/aunts 12. 5% 1 st cousins general population 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 6

Molecular Neuroscience Clinical Neuroscience Human Genome and Associated Data 7

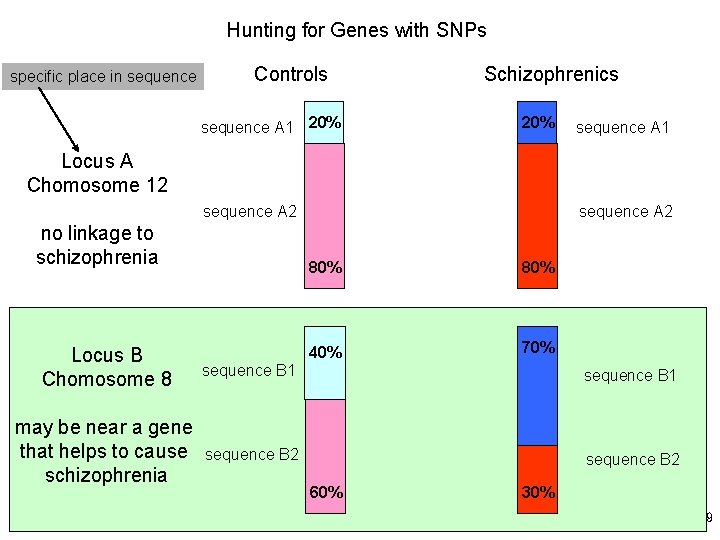

We describe a map of 1. 42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) distributed throughout the human genome, providing an average density on available sequence of one SNP every 1. 9 kilobases. This high-density SNP map provides a public resource for defining haplotype variation across the genome, and should help to identify biomedically important genes for diagnosis and therapy. The International SNP Working Group (Lander et al) 8

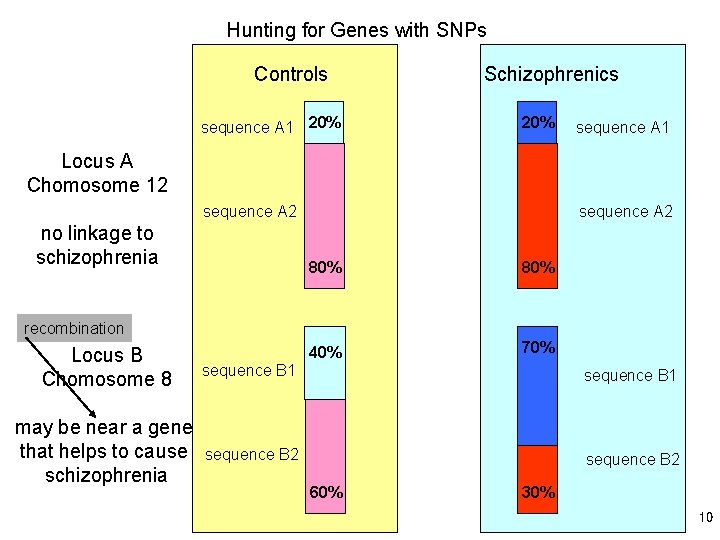

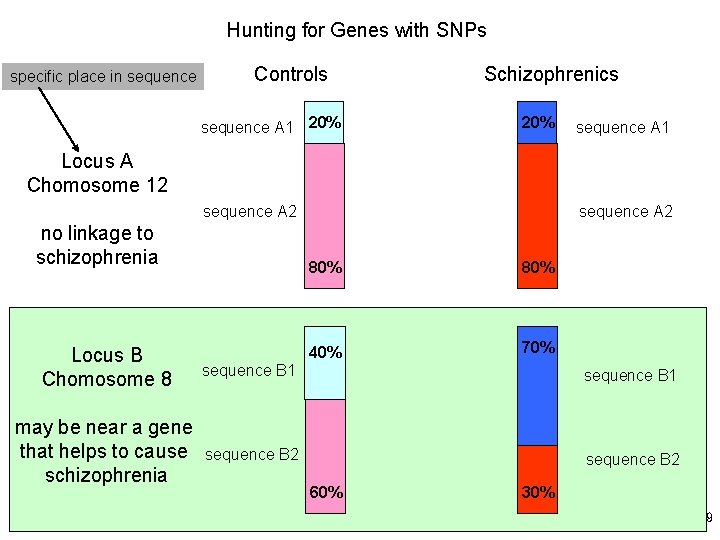

Hunting for Genes with SNPs specific place in sequence Controls sequence A 1 20% Schizophrenics 20% sequence A 1 Locus A Chomosome 12 sequence A 2 no linkage to schizophrenia 80% 40% 70% Locus B Chomosome 8 sequence B 1 may be near a gene that helps to cause schizophrenia sequence B 2 60% 30% 9

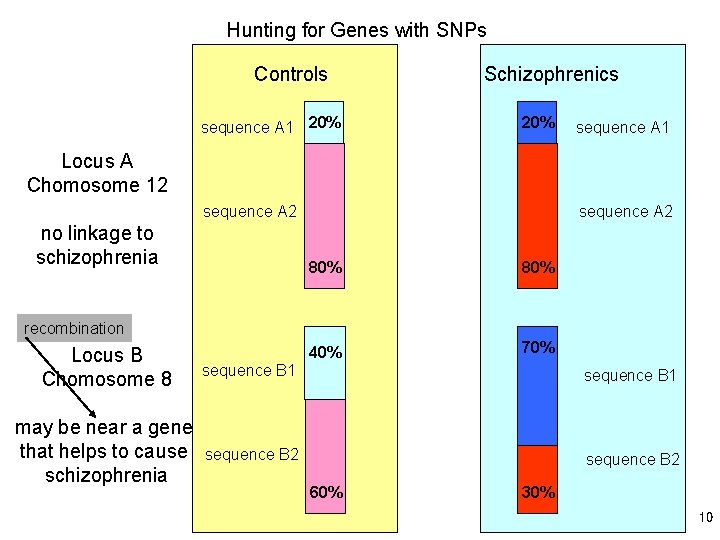

Hunting for Genes with SNPs Controls sequence A 1 20% Schizophrenics 20% sequence A 1 Locus A Chomosome 12 sequence A 2 no linkage to schizophrenia 80% 40% 70% recombination Locus B Chomosome 8 sequence B 1 may be near a gene that helps to cause schizophrenia sequence B 2 60% 30% 10

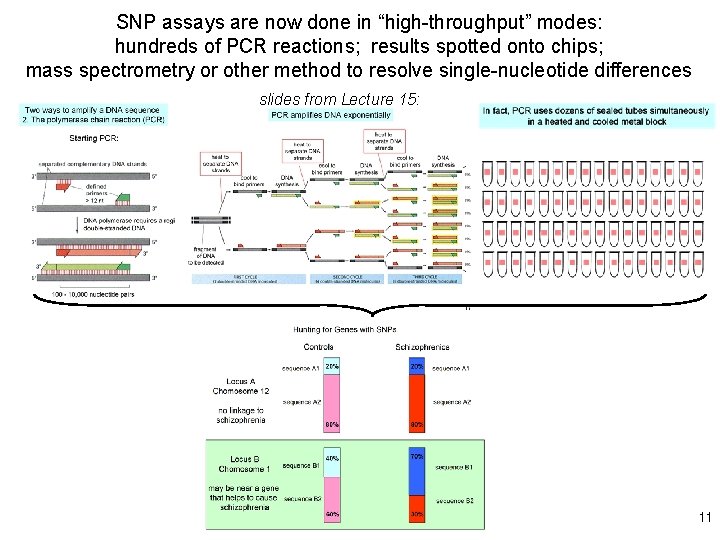

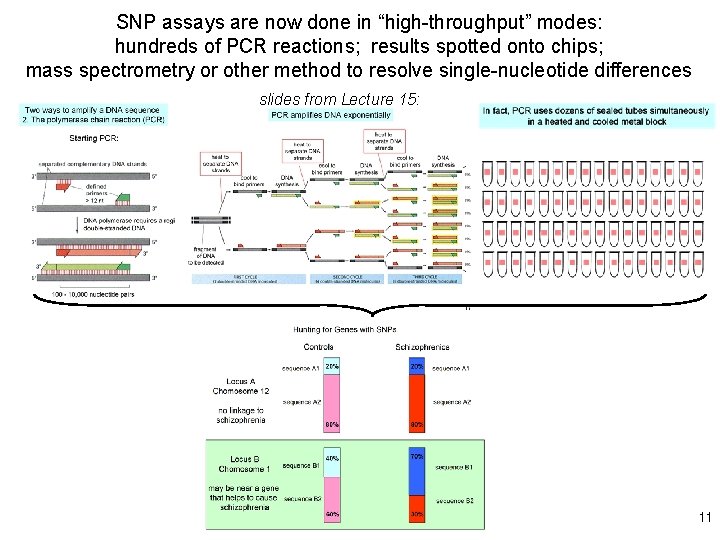

SNP assays are now done in “high-throughput” modes: hundreds of PCR reactions; results spotted onto chips; mass spectrometry or other method to resolve single-nucleotide differences slides from Lecture 15: 11

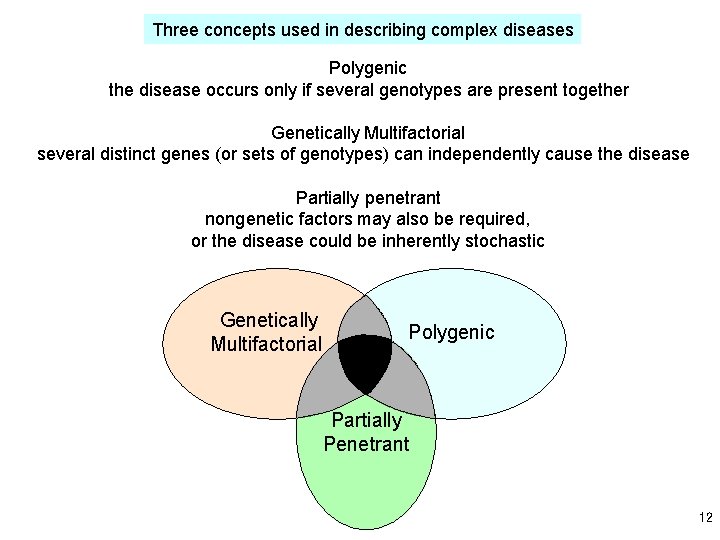

Three concepts used in describing complex diseases Polygenic the disease occurs only if several genotypes are present together Genetically Multifactorial several distinct genes (or sets of genotypes) can independently cause the disease Partially penetrant nongenetic factors may also be required, or the disease could be inherently stochastic Genetically Multifactorial Polygenic Partially Penetrant 12

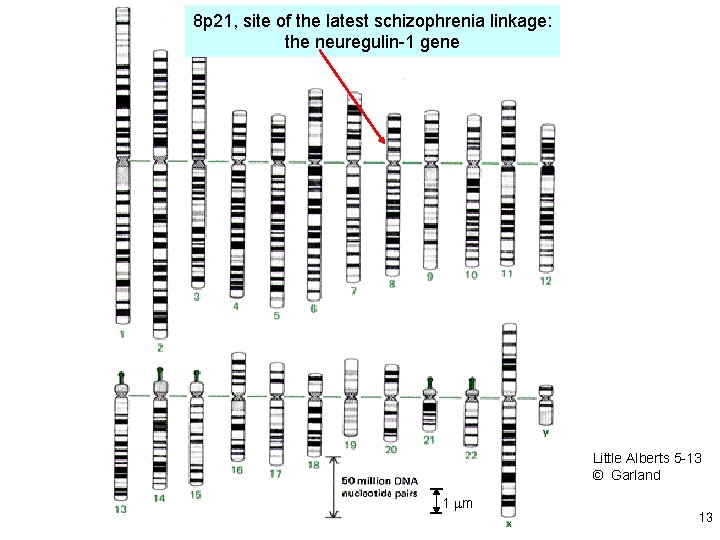

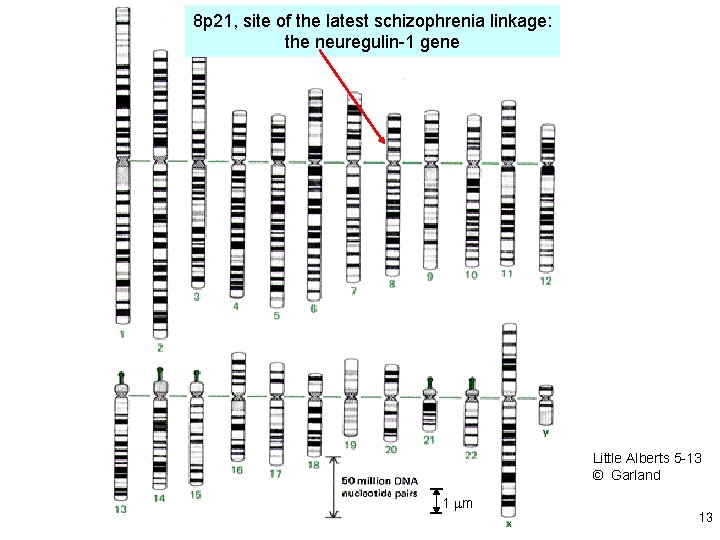

8 p 21, site of the latest schizophrenia linkage: the neuregulin-1 gene Little Alberts 5 -13 © Garland 1 mm 13

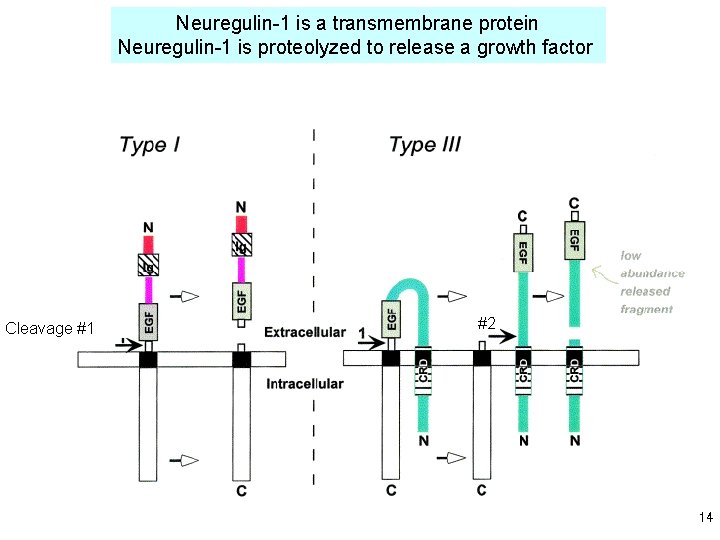

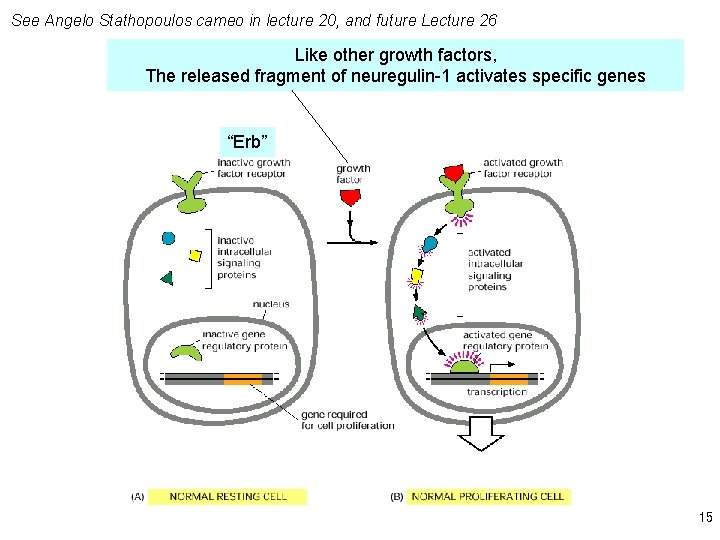

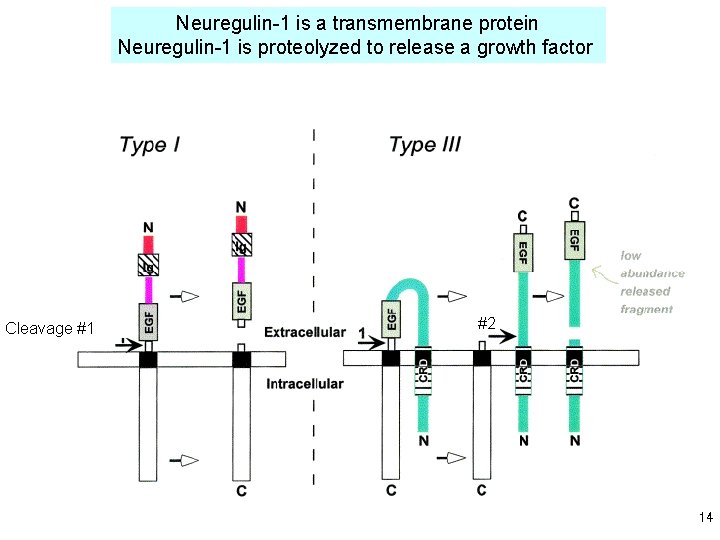

Neuregulin-1 is a transmembrane protein Neuregulin-1 is proteolyzed to release a growth factor Cleavage #1 #2 14

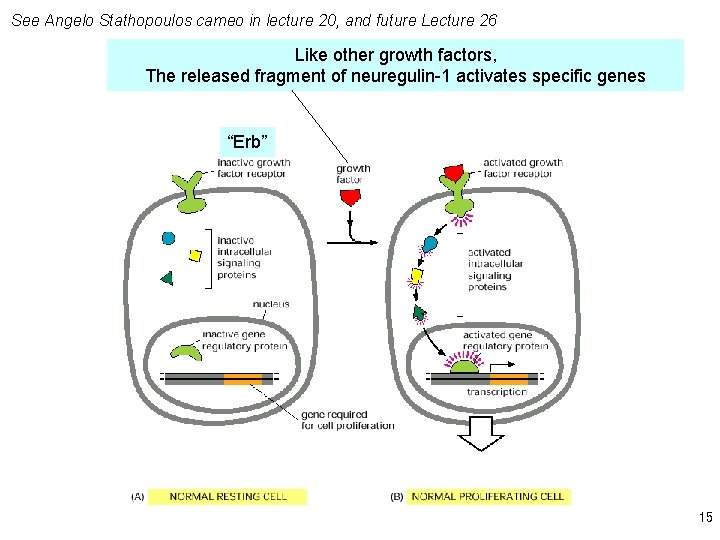

See Angelo Stathopoulos cameo in lecture 20, and future Lecture 26 Like other growth factors, The released fragment of neuregulin-1 activates specific genes “Erb” 15

3. Pathophysiology. Each new advance in neuroscience has been tried out on schizophrenia. There is no satisfactory explanation yet. In general, modern theories of schizophrenia emphasize abnormal neuronal circuits or pathways, rather than individual neurons that either (a) degenerate or (b) fire too fast or too slow Specific cell types may migrate incorrectly in embryonic development 16

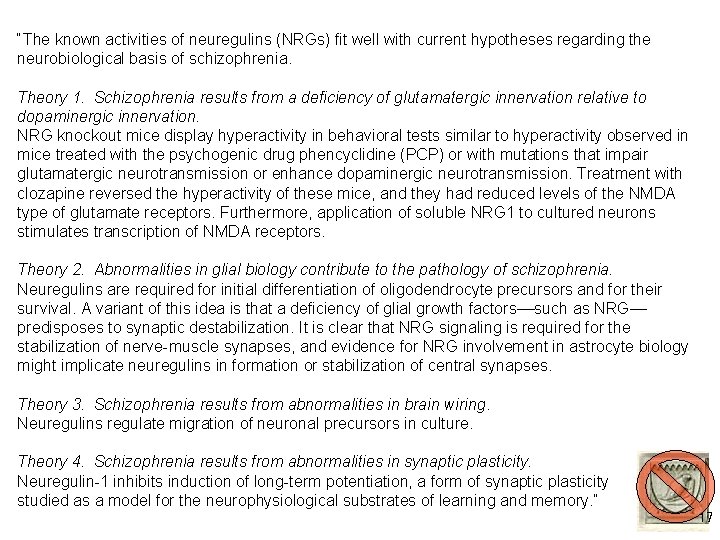

“The known activities of neuregulins (NRGs) fit well with current hypotheses regarding the neurobiological basis of schizophrenia. Theory 1. Schizophrenia results from a deficiency of glutamatergic innervation relative to dopaminergic innervation. NRG knockout mice display hyperactivity in behavioral tests similar to hyperactivity observed in mice treated with the psychogenic drug phencyclidine (PCP) or with mutations that impair glutamatergic neurotransmission or enhance dopaminergic neurotransmission. Treatment with clozapine reversed the hyperactivity of these mice, and they had reduced levels of the NMDA type of glutamate receptors. Furthermore, application of soluble NRG 1 to cultured neurons stimulates transcription of NMDA receptors. Theory 2. Abnormalities in glial biology contribute to the pathology of schizophrenia. Neuregulins are required for initial differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors and for their survival. A variant of this idea is that a deficiency of glial growth factors––such as NRG–– predisposes to synaptic destabilization. It is clear that NRG signaling is required for the stabilization of nerve-muscle synapses, and evidence for NRG involvement in astrocyte biology might implicate neuregulins in formation or stabilization of central synapses. Theory 3. Schizophrenia results from abnormalities in brain wiring. Neuregulins regulate migration of neuronal precursors in culture. Theory 4. Schizophrenia results from abnormalities in synaptic plasticity. Neuregulin-1 inhibits induction of long-term potentiation, a form of synaptic plasticity studied as a model for the neurophysiological substrates of learning and memory. ” 17

Nongenetic contributions: the other 50% (1) Nourishment and health of the fetus Viral infections during pregnancy, Possibly leading to low-level inflammation (Prof. Paul Patterson, Caltech)? (2) Head injury 18

4. Objective physiological measurements that correlate with schizophrenia Biomarkers are objective, measurable biochemical, genetic, or other biological indicators of a physiological or disease process. . . complex conditions, such as mental illness, might benefit from constellations of several different biomarkers being used in concert. . . biomarkers could facilitate definitive diagnosis of mental disorders in individuals, assess the susceptibility of individuals to a particular disorder, indicate changes in the severity of a disorder, and show the response of a disorder to a given treatment. . . Some disorders appear as a broad spectrum where signs and symptoms vary enormously but yet collectively represent one general disorder (e. g. autism spectrum disorders). In other instances, a particular symptom may appear across a variety of mental disorders (e. g. , cognitive impairment) or represent an exaggeration of a dimension seen in healthy individuals (e. g. , depressed mood). . . Biomarkers could aid clinicians in categorizing particular signs and symptoms so that a spectrum disorder could be broken down into well-defined subcategories, allowing differential analysis or treatment. Biomarkers. . . could be used in basic research to map the variability of a marker across healthy populations. 19

4. Objective physiological measurements that correlate with schizophrenia 1. Electroencephalograms 2. Eye pursuit 20

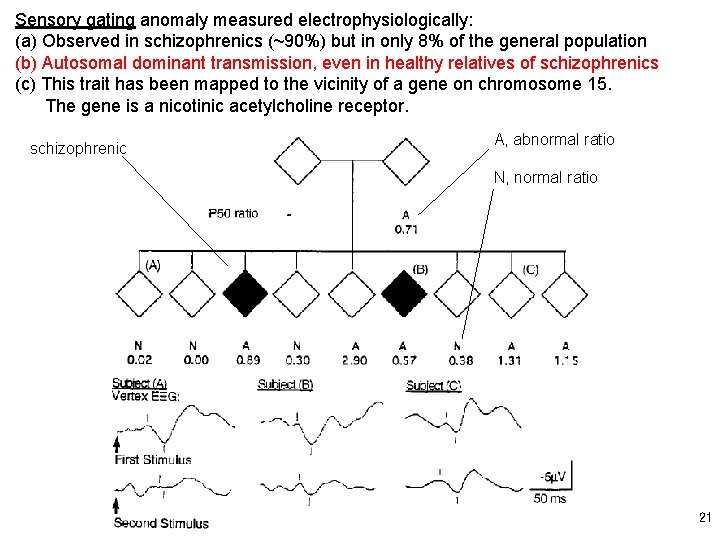

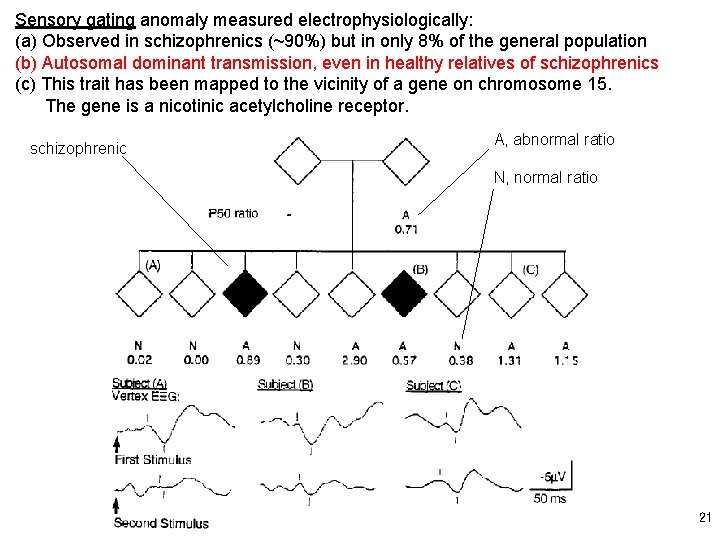

Sensory gating anomaly measured electrophysiologically: (a) Observed in schizophrenics (~90%) but in only 8% of the general population (b) Autosomal dominant transmission, even in healthy relatives of schizophrenics (c) This trait has been mapped to the vicinity of a gene on chromosome 15. The gene is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. A, abnormal ratio schizophrenic N, normal ratio a 21

5. Therapeutic approaches Dopamine D 2 blockers are the classical “antipsychotic” drugs. See Nestler Figure 17 -11, p 402 And Problem Set 7 All dopamine receptors are GPCRs. 22

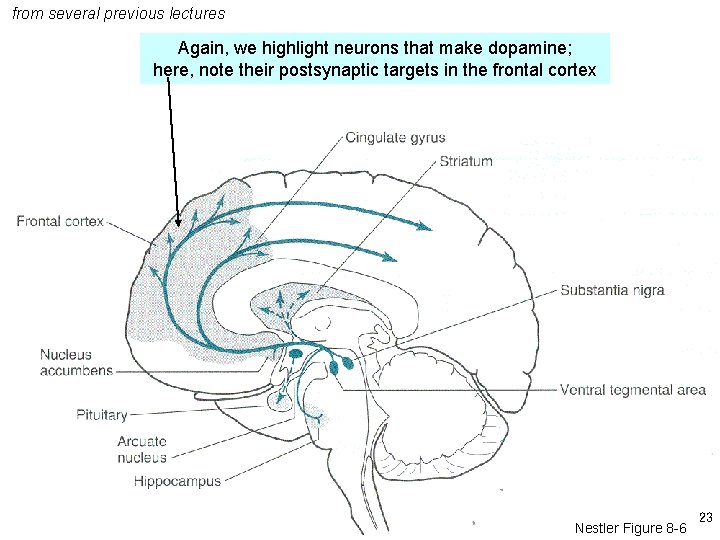

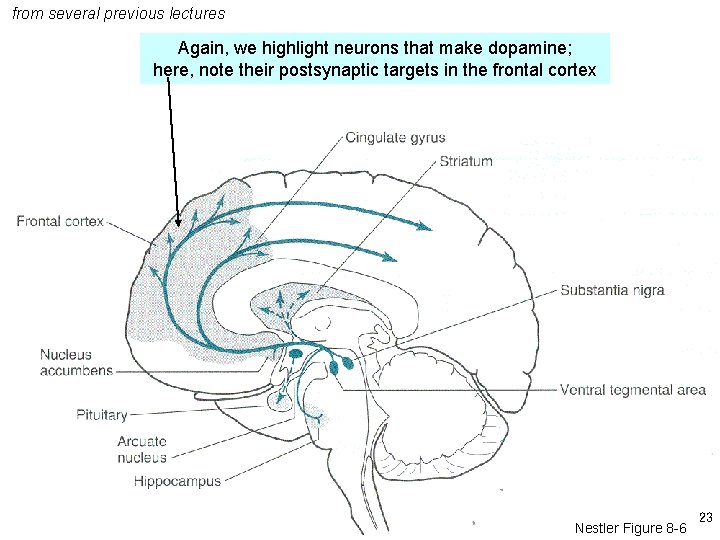

from several previous lectures Again, we highlight neurons that make dopamine; here, note their postsynaptic targets in the frontal cortex Nestler Figure 8 -6 23

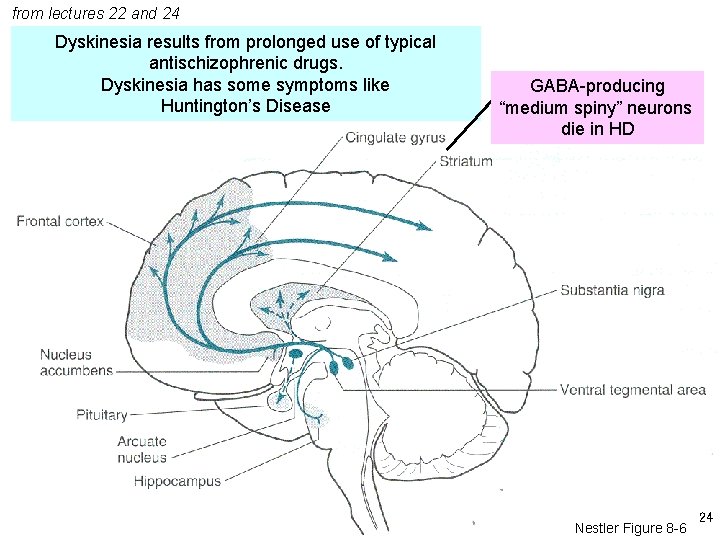

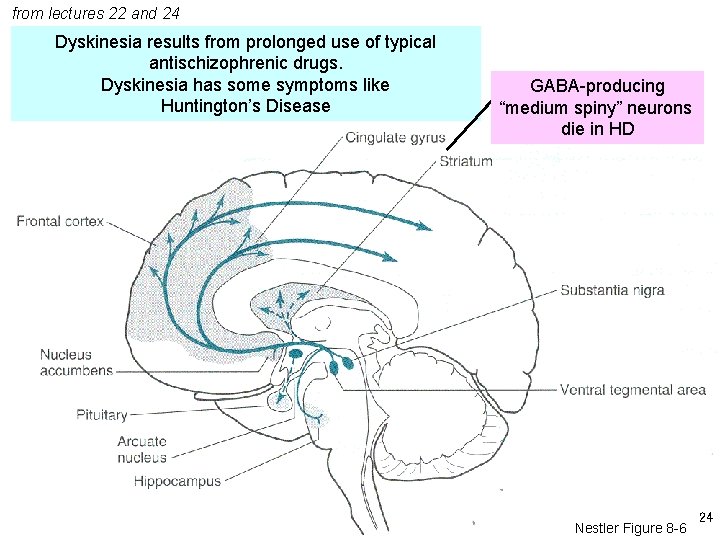

from lectures 22 and 24 Dyskinesia results from prolonged use of typical antischizophrenic drugs. Dyskinesia has some symptoms like Huntington’s Disease GABA-producing “medium spiny” neurons die in HD Nestler Figure 8 -6 24

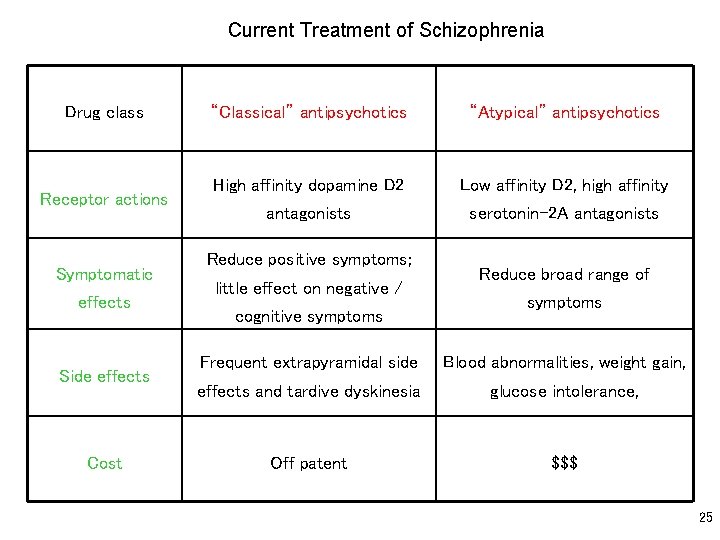

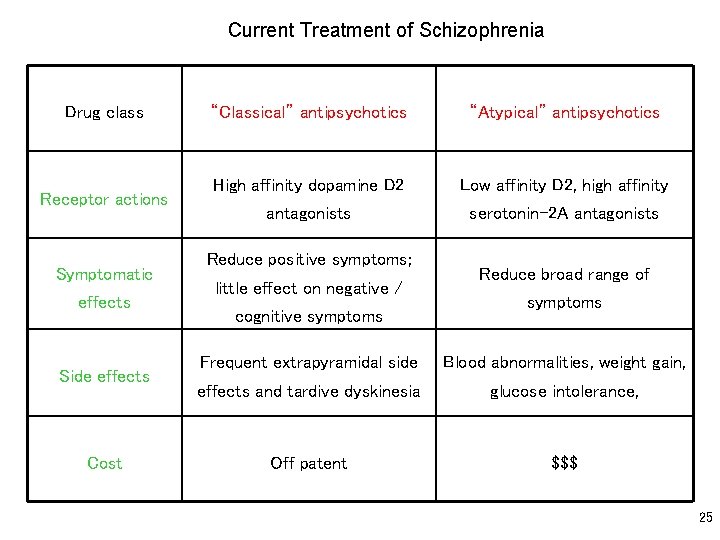

Current Treatment of Schizophrenia Drug class Receptor actions Symptomatic effects Side effects Cost “Classical” antipsychotics “Atypical” antipsychotics High affinity dopamine D 2 Low affinity D 2, high affinity antagonists serotonin-2 A antagonists Reduce positive symptoms; little effect on negative / cognitive symptoms Reduce broad range of symptoms Frequent extrapyramidal side Blood abnormalities, weight gain, effects and tardive dyskinesia glucose intolerance, Off patent $$$ 25

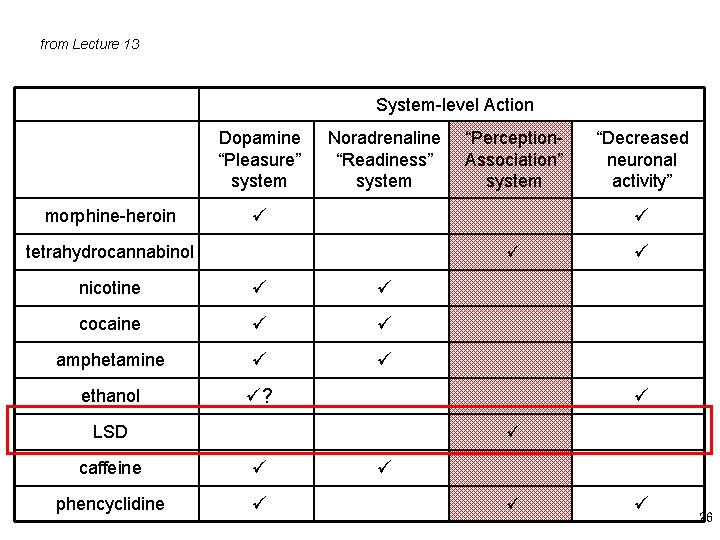

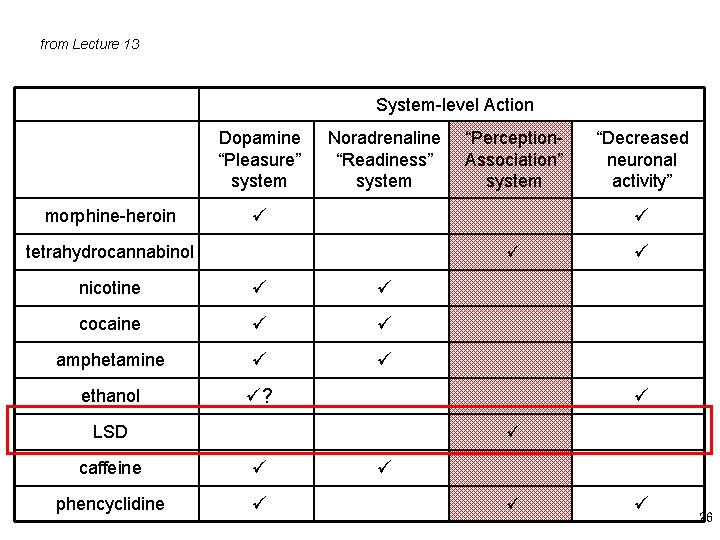

from Lecture 13 System-level Action Dopamine “Pleasure” system morphine-heroin Noradrenaline “Readiness” system “Perception. Association” system “Decreased neuronal activity” tetrahydrocannabinol nicotine cocaine amphetamine ethanol ? LSD caffeine phencyclidine 26

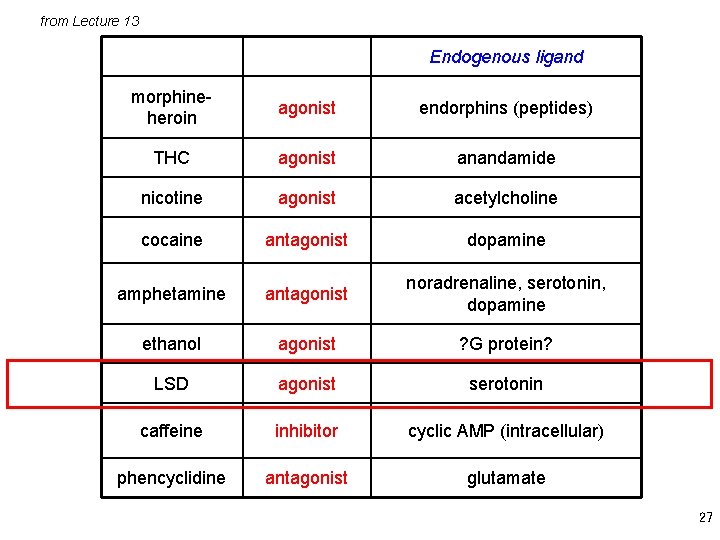

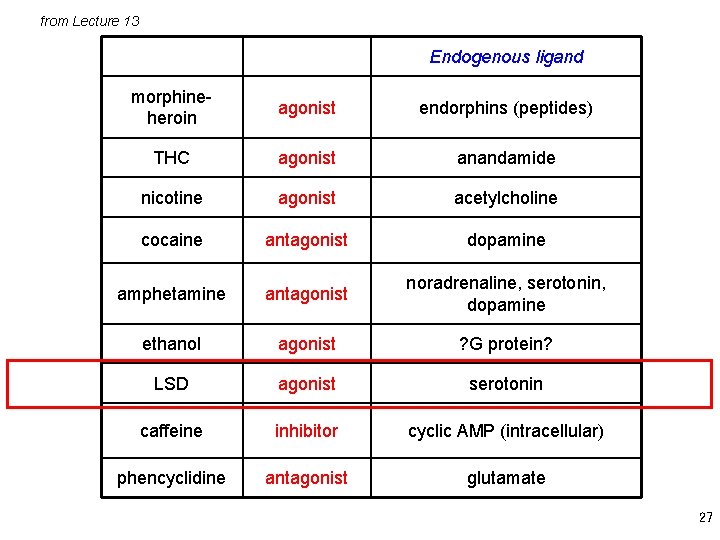

from Lecture 13 Endogenous ligand morphineheroin agonist endorphins (peptides) THC agonist anandamide nicotine agonist acetylcholine cocaine antagonist dopamine amphetamine antagonist noradrenaline, serotonin, dopamine ethanol agonist ? G protein? LSD agonist serotonin caffeine inhibitor cyclic AMP (intracellular) phencyclidine antagonist glutamate 27

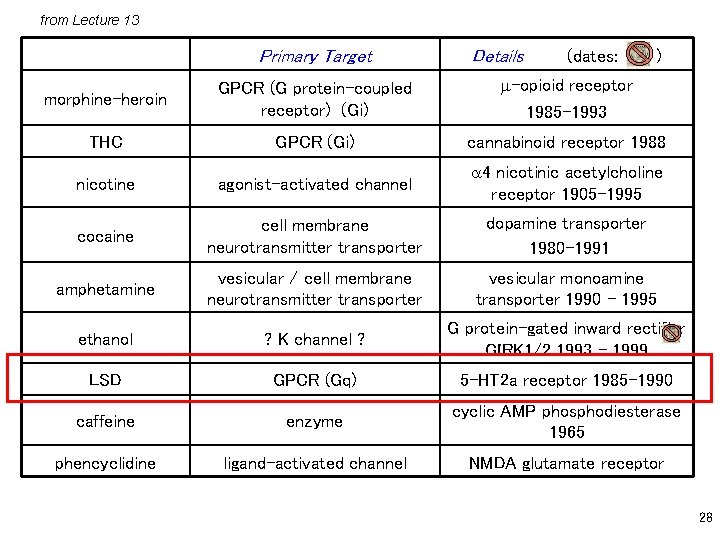

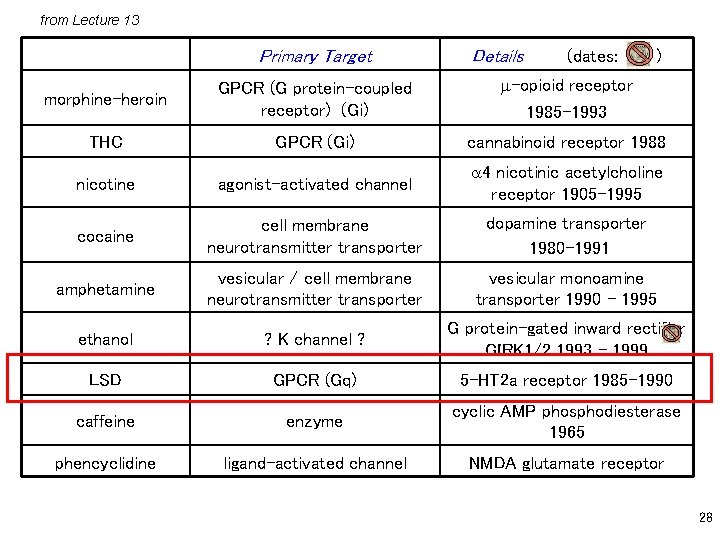

from Lecture 13 Primary Target Details (dates: ) morphine-heroin GPCR (G protein-coupled receptor) (Gi) m-opioid receptor 1985 -1993 THC GPCR (Gi) cannabinoid receptor 1988 nicotine agonist-activated channel a 4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor 1905 -1995 cocaine cell membrane neurotransmitter transporter dopamine transporter 1980 -1991 amphetamine vesicular / cell membrane neurotransmitter transporter vesicular monoamine transporter 1990 - 1995 ethanol ? K channel ? G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK 1/2 1993 - 1999 LSD GPCR (Gq) 5 -HT 2 a receptor 1985 -1990 caffeine enzyme cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase 1965 phencyclidine ligand-activated channel NMDA glutamate receptor 28

Most antipsychotic drugs take at least 2 weeks to exert their effects on the symptoms of schizophrenia. Therefore these drugs teach us too little about the cause(s) of schizophrenia. What happens during those 2 weeks? We don’t know. Presumably the nervous system responds to the initial effect of the drug by readjusting synapses, gene activation, and other processes. 29

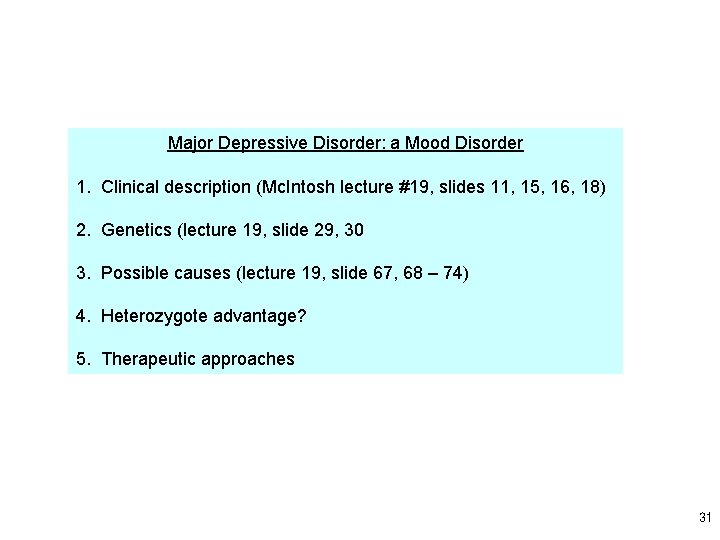

Major Depressive Disorder: a Mood Disorder 1. Clinical description (Mc. Intosh lecture #19, slides 11, 15, 16, 18) 2. Genetics (lecture 19, slide 29, 30 3. Possible causes (lecture 19, slide 67, 68 – 74) 4. Heterozygote advantage? 5. Therapeutic approaches 31

From DSM-IV Summary description of a Major Depressive Episode : The essential feature of a Major Depressive Episode is a period of at least 2 weeks during which there is either depressed mood or the loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities. In children, adolescents, and some adults, the mood may be irritable rather than sad. The individual must also experience at least four additional symptoms drawn from a list that includes: • changes in appetite or weight, sleep, and psychomotor activity; • decreased energy; • feelings of worthlessness or guilt; • difficulty thinking, concentrating, or making decisions; or • recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation, plans, or attempts. To count toward a Major Depressive Episode, a symptom must either be newly present or must have clearly worsened. The symptoms must persist for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least 2 consecutive weeks. The episode must be accompanied by clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. 32

(click on the text to read the entire excerpt in Word) 33

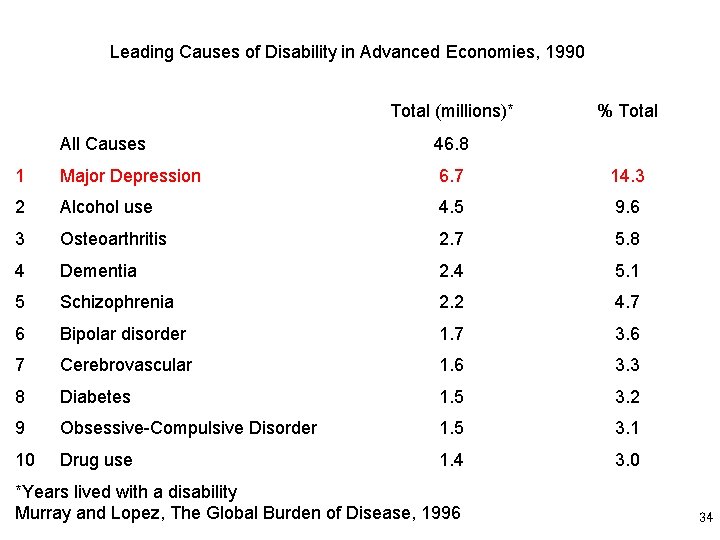

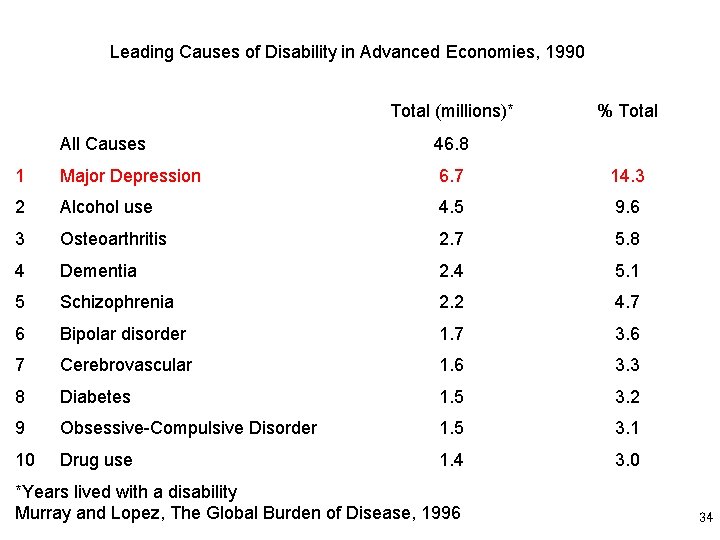

Leading Causes of Disability in Advanced Economies, 1990 Total (millions)* % Total All Causes 46. 8 1 Major Depression 6. 7 14. 3 2 Alcohol use 4. 5 9. 6 3 Osteoarthritis 2. 7 5. 8 4 Dementia 2. 4 5. 1 5 Schizophrenia 2. 2 4. 7 6 Bipolar disorder 1. 7 3. 6 7 Cerebrovascular 1. 6 3. 3 8 Diabetes 1. 5 3. 2 9 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder 1. 5 3. 1 10 Drug use 1. 4 3. 0 *Years lived with a disability Murray and Lopez, The Global Burden of Disease, 1996 34

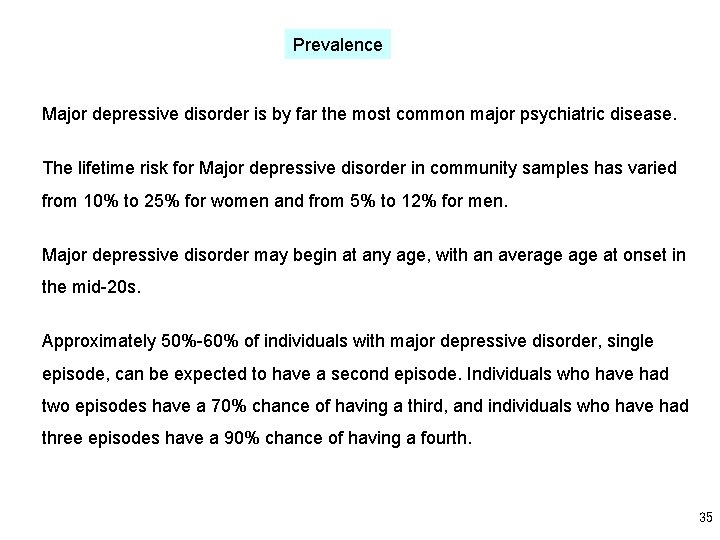

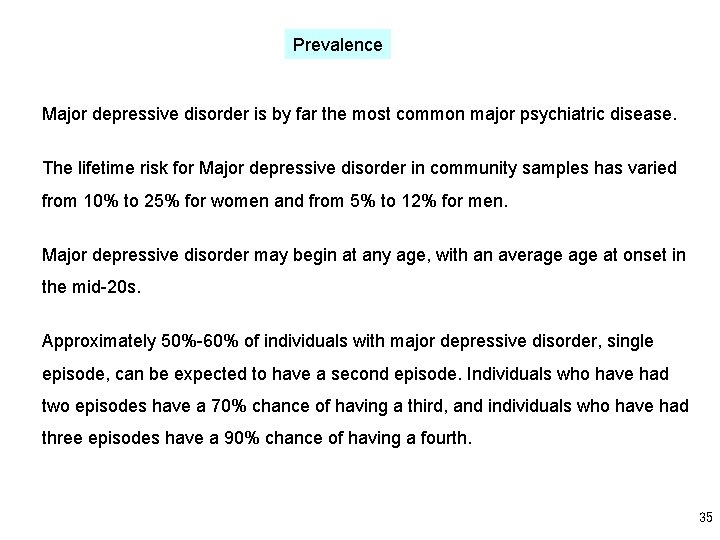

Prevalence Major depressive disorder is by far the most common major psychiatric disease. The lifetime risk for Major depressive disorder in community samples has varied from 10% to 25% for women and from 5% to 12% for men. Major depressive disorder may begin at any age, with an average at onset in the mid-20 s. Approximately 50%-60% of individuals with major depressive disorder, single episode, can be expected to have a second episode. Individuals who have had two episodes have a 70% chance of having a third, and individuals who have had three episodes have a 90% chance of having a fourth. 35

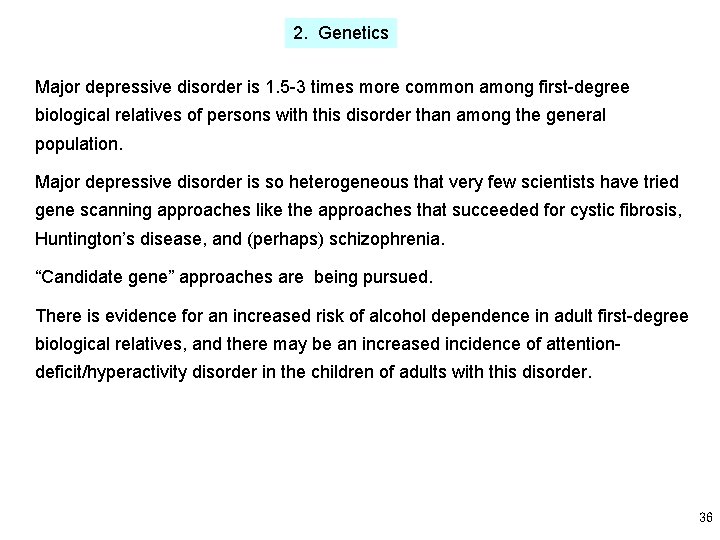

2. Genetics Major depressive disorder is 1. 5 -3 times more common among first-degree biological relatives of persons with this disorder than among the general population. Major depressive disorder is so heterogeneous that very few scientists have tried gene scanning approaches like the approaches that succeeded for cystic fibrosis, Huntington’s disease, and (perhaps) schizophrenia. “Candidate gene” approaches are being pursued. There is evidence for an increased risk of alcohol dependence in adult first-degree biological relatives, and there may be an increased incidence of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder in the children of adults with this disorder. 36

4. Possible causes 37

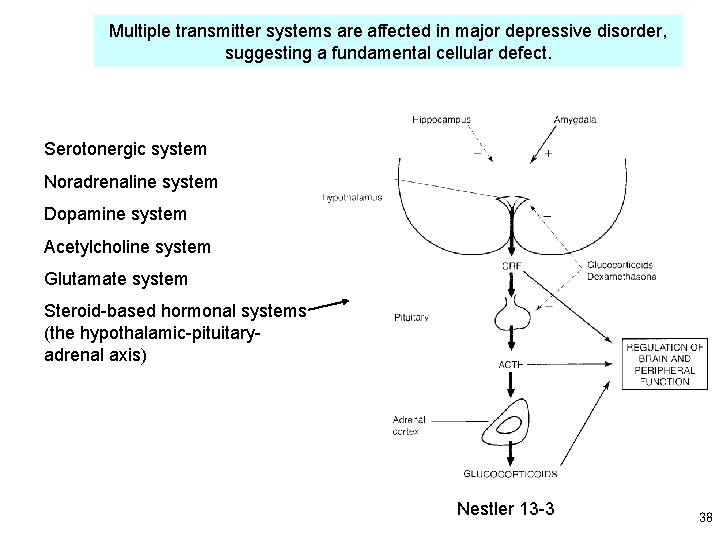

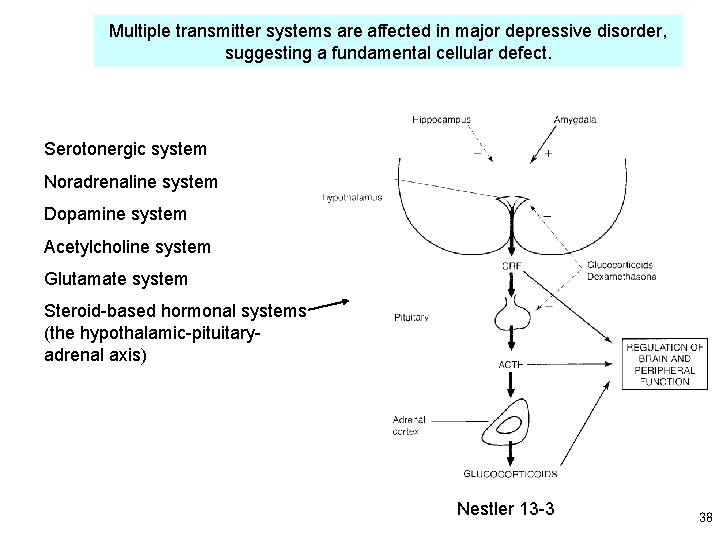

Multiple transmitter systems are affected in major depressive disorder, suggesting a fundamental cellular defect. Serotonergic system Noradrenaline system Dopamine system Acetylcholine system Glutamate system Steroid-based hormonal systems (the hypothalamic-pituitaryadrenal axis) Nestler 13 -3 38

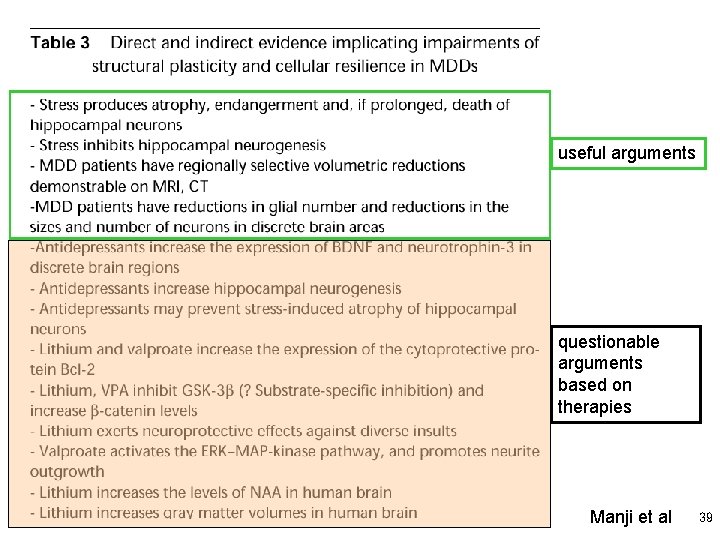

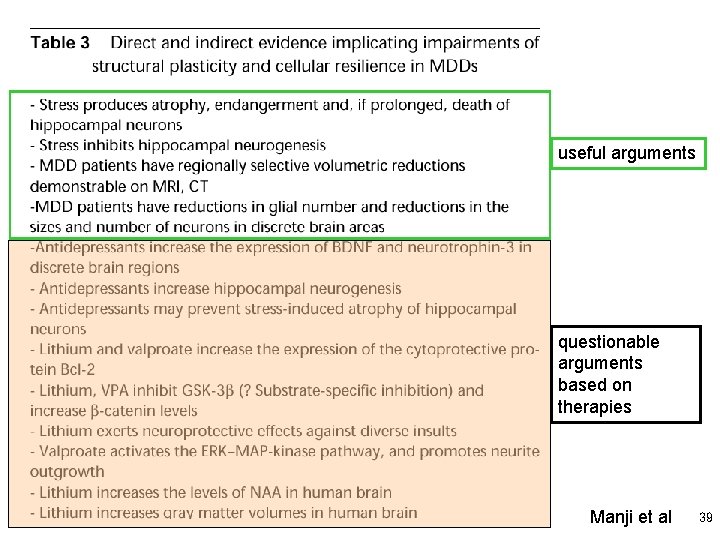

useful arguments questionable arguments based on therapies Manji et al 39

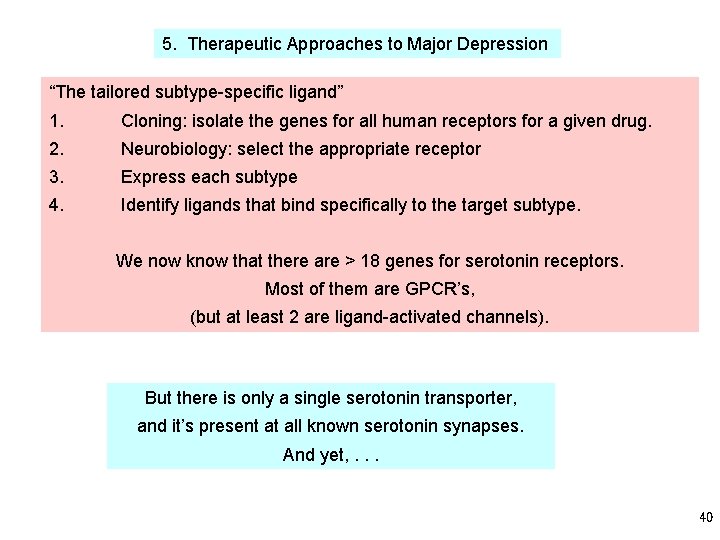

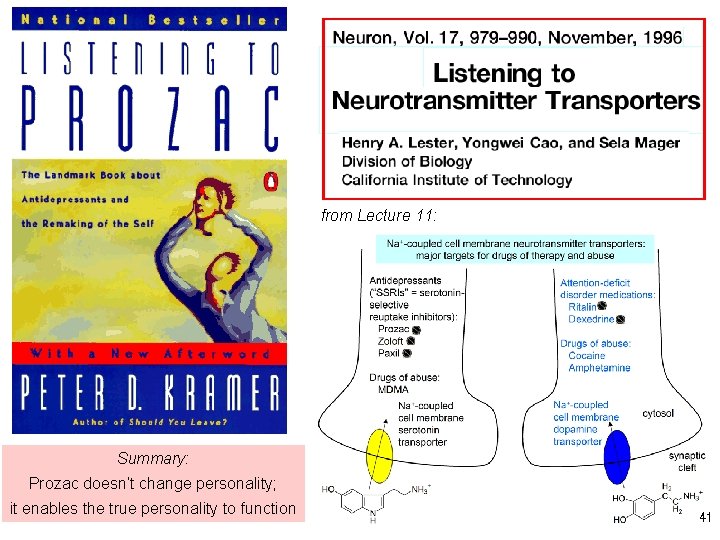

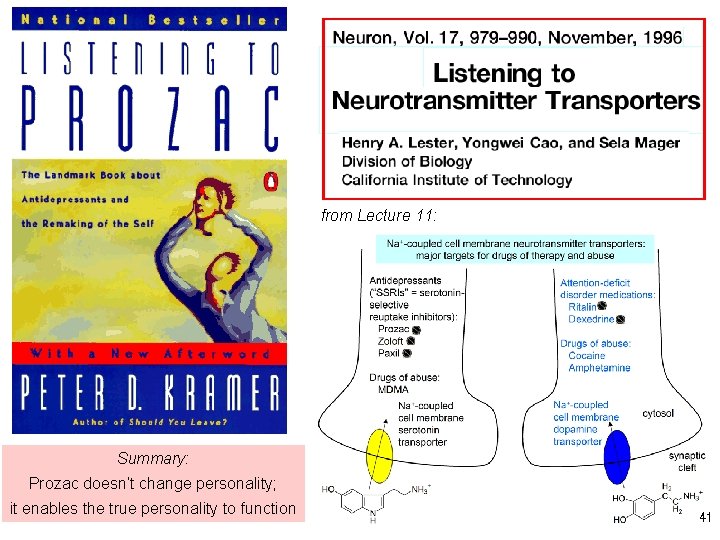

5. Therapeutic Approaches to Major Depression “The tailored subtype-specific ligand” 1. Cloning: isolate the genes for all human receptors for a given drug. 2. Neurobiology: select the appropriate receptor 3. Express each subtype 4. Identify ligands that bind specifically to the target subtype. We now know that there are > 18 genes for serotonin receptors. Most of them are GPCR’s, (but at least 2 are ligand-activated channels). But there is only a single serotonin transporter, and it’s present at all known serotonin synapses. And yet, . . . 40

from Lecture 11: Summary: Prozac doesn’t change personality; it enables the true personality to function 41

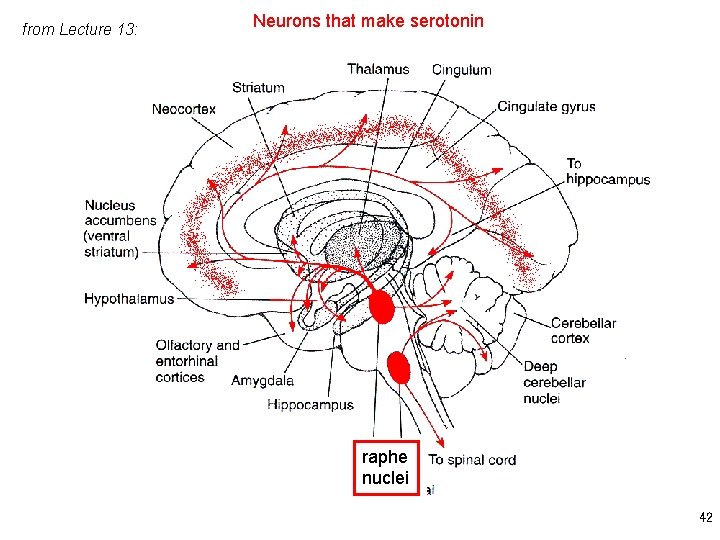

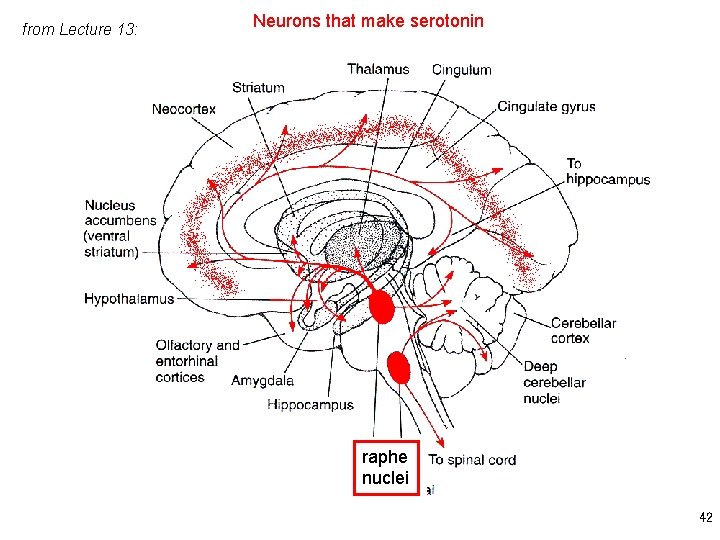

from Lecture 13: Neurons that make serotonin raphe nuclei 42

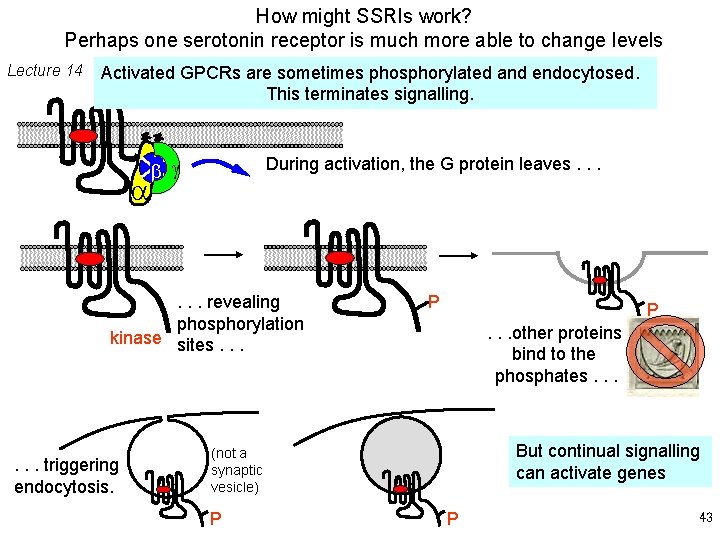

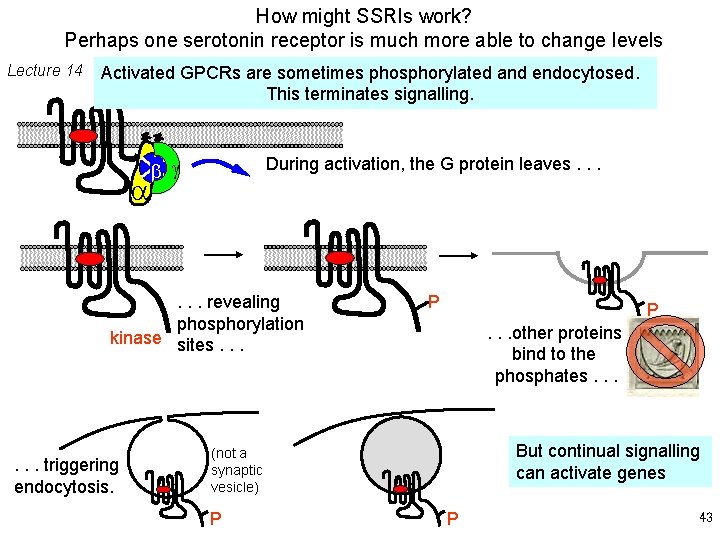

How might SSRIs work? Perhaps one serotonin receptor is much more able to change levels Lecture 14 Activated GPCRs are sometimes phosphorylated and endocytosed. This terminates signalling. a During activation, the G protein leaves. . . b g . . . revealing phosphorylation kinase sites. . . triggering endocytosis. P P. . . other proteins bind to the phosphates. . . But continual signalling can activate genes (not a synaptic vesicle) P P 43

The present discussion about the wisdom of prescribing SSRI’s to teenagers DSM-IV: “The presence in a depressed patient of a positive family history of bipolar disorder or acute psychosis probably increases the chances that the patient's own depressive disorder is a manifestation of bipolar rather than unipolar disorder and that antidepressant therapy may incite a switch into mania. ” 44

Recent uses for SSRI’s depression irritability obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) social phobia premenstrual syndrome eating disorders 45

Nonpharmacological Treatments for Depression (in conjunction with antidepressants, or after antidepressants have failed) Goal = reduce symptoms of depression and return patient to full, active life • Psychotherapy - Cognitive behavioral therapy - • Interpersonal therapy Psychodynamic therapy Electroconvulsive therapy 46

Public Service Announcements: “Real Men, Real Depression” See also http: //menanddepression. nimh. nih. gov/ 47

Bi 1 “Drugs and the Brain” End of Lecture 23 48

David helfgott disability

David helfgott disability David helfgott rachmaninov piano concerto 3

David helfgott rachmaninov piano concerto 3 Miracle play genre

Miracle play genre David helfgott diagnosis

David helfgott diagnosis Forte fortissimo

Forte fortissimo Insidious mastery of song

Insidious mastery of song Concerto grosso definicion

Concerto grosso definicion Concerto signage

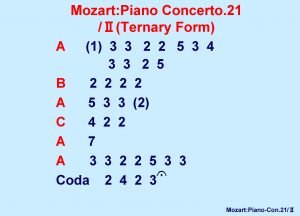

Concerto signage Wolfgang amadeus mozart horn concerto no. 4

Wolfgang amadeus mozart horn concerto no. 4 Digital signage concerto

Digital signage concerto A typical sequence of movements in a classical concerto is

A typical sequence of movements in a classical concerto is The term concerto grosso means

The term concerto grosso means A classical concerto is a three movement work for

A classical concerto is a three movement work for Digital signage ppt

Digital signage ppt Dr david galbreath

Dr david galbreath Copenhagen golf center

Copenhagen golf center Reflections copenhagen

Reflections copenhagen Completeness in quantum mechanics

Completeness in quantum mechanics Securitization copenhagen school

Securitization copenhagen school Copenhagen

Copenhagen Arv copenhagen

Arv copenhagen Internet copenhagen

Internet copenhagen Copenhagen interpretation

Copenhagen interpretation University of copenhagen library

University of copenhagen library Hera copenhagen

Hera copenhagen Copenhagen charter cos'è

Copenhagen charter cos'è Burnout symptome wikipedia

Burnout symptome wikipedia Eu

Eu Ems 2018 copenhagen

Ems 2018 copenhagen Hiv cure

Hiv cure Copenhagen charter cos'è

Copenhagen charter cos'è Copenhagen interpretation

Copenhagen interpretation Copenhagen school five sectors of security

Copenhagen school five sectors of security When did john milton go blind

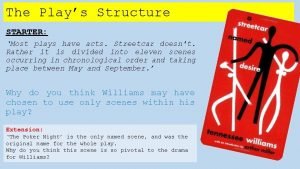

When did john milton go blind How to quote plays

How to quote plays My friend plays tennis and football

My friend plays tennis and football Plays like romeo and juliet

Plays like romeo and juliet What is a theatrical convention?

What is a theatrical convention? Which term is used to describe bitmap images?

Which term is used to describe bitmap images? The plays the thing

The plays the thing Dignity its essential role in resolving conflict

Dignity its essential role in resolving conflict Moulding personality meaning

Moulding personality meaning The first greek plays grew out of

The first greek plays grew out of Present tense practice sentences

Present tense practice sentences Morality play characteristics

Morality play characteristics Daylight pickoff play

Daylight pickoff play Fbz service plays

Fbz service plays Short radio plays

Short radio plays