Shakespeares History Plays history plays in Shakespeares career

- Slides: 23

Shakespeare’s History Plays

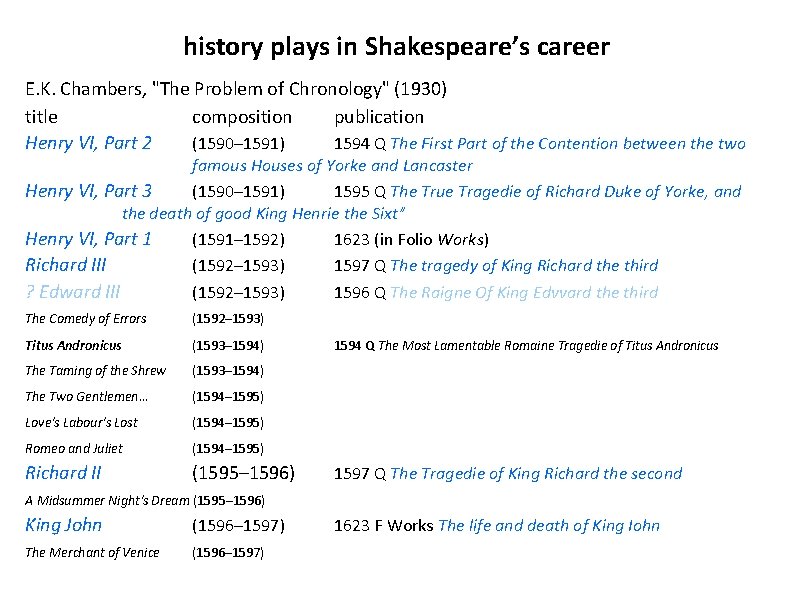

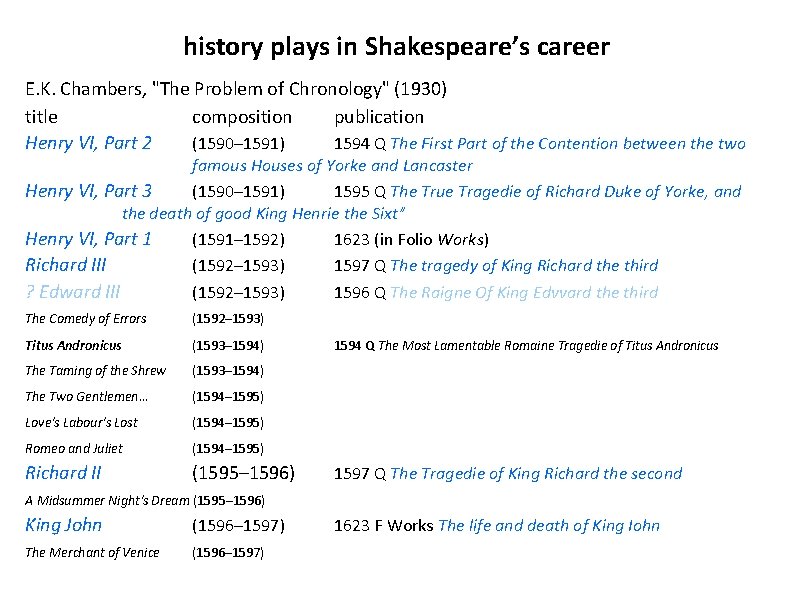

history plays in Shakespeare’s career E. K. Chambers, "The Problem of Chronology" (1930) title composition publication Henry VI, Part 2 (1590– 1591) 1594 Q The First Part of the Contention between the two famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster Henry VI, Part 3 (1590– 1591) 1595 Q The True Tragedie of Richard Duke of Yorke, and the death of good King Henrie the Sixt” Henry VI, Part 1 (1591– 1592) 1623 (in Folio Works) Richard III (1592– 1593) 1597 Q The tragedy of King Richard the third ? Edward III (1592– 1593) 1596 Q The Raigne Of King Edvvard the third The Comedy of Errors (1592– 1593) Titus Andronicus (1593– 1594) The Taming of the Shrew (1593– 1594) The Two Gentlemen… (1594– 1595) Love's Labour's Lost (1594– 1595) Romeo and Juliet (1594– 1595) Richard II (1595– 1596) 1594 Q The Most Lamentable Romaine Tragedie of Titus Andronicus 1597 Q The Tragedie of King Richard the second A Midsummer Night's Dream (1595– 1596) King John (1596– 1597) The Merchant of Venice (1596– 1597) 1623 F Works The life and death of King Iohn

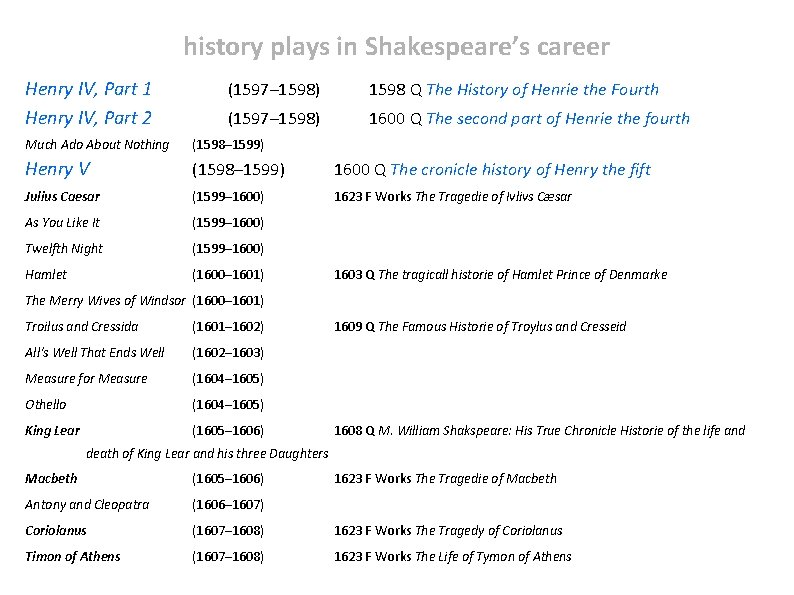

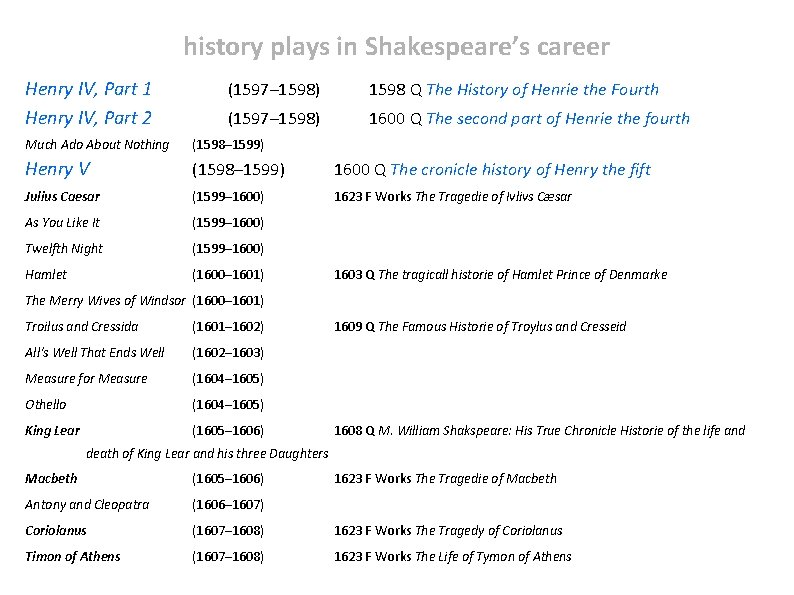

history plays in Shakespeare’s career Henry IV, Part 1 Henry IV, Part 2 (1597– 1598) 1598 Q The History of Henrie the Fourth (1597– 1598) 1600 Q The second part of Henrie the fourth Much Ado About Nothing (1598– 1599) Henry V (1598– 1599) 1600 Q The cronicle history of Henry the fift Julius Caesar (1599– 1600) 1623 F Works The Tragedie of Ivlivs Cæsar As You Like It (1599– 1600) Twelfth Night (1599– 1600) Hamlet (1600– 1601) 1603 Q The tragicall historie of Hamlet Prince of Denmarke The Merry Wives of Windsor (1600– 1601) Troilus and Cressida (1601– 1602) All's Well That Ends Well (1602– 1603) Measure for Measure (1604– 1605) Othello (1604– 1605) King Lear (1605– 1606) 1609 Q The Famous Historie of Troylus and Cresseid 1608 Q M. William Shakspeare: His True Chronicle Historie of the life and death of King Lear and his three Daughters Macbeth (1605– 1606) 1623 F Works The Tragedie of Macbeth Antony and Cleopatra (1606– 1607) Coriolanus (1607– 1608) 1623 F Works The Tragedy of Coriolanus Timon of Athens (1607– 1608) 1623 F Works The Life of Tymon of Athens

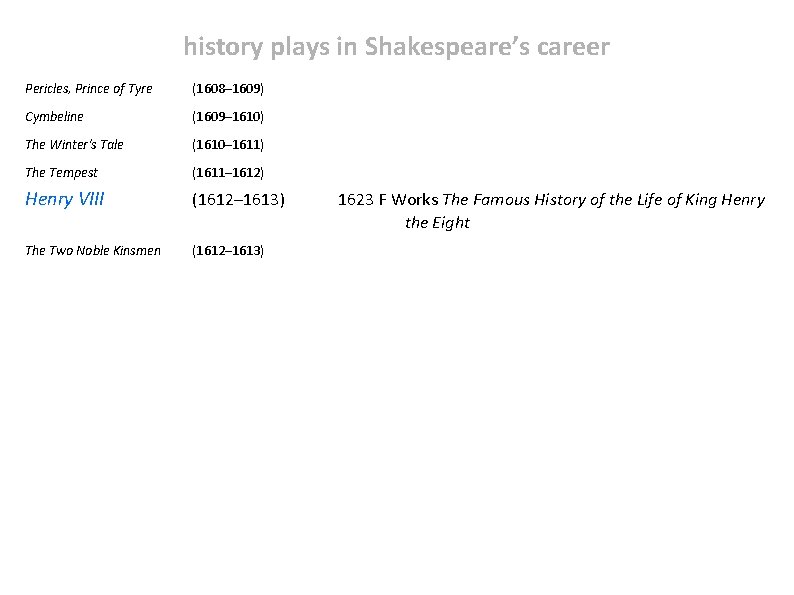

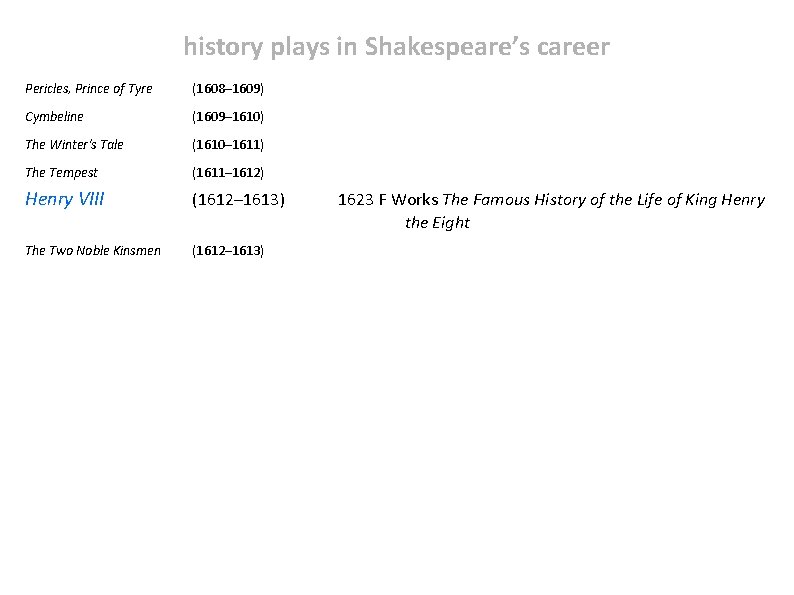

history plays in Shakespeare’s career Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1608– 1609) Cymbeline (1609– 1610) The Winter's Tale (1610– 1611) The Tempest (1611– 1612) Henry VIII (1612– 1613) The Two Noble Kinsmen (1612– 1613) 1623 F Works The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eight

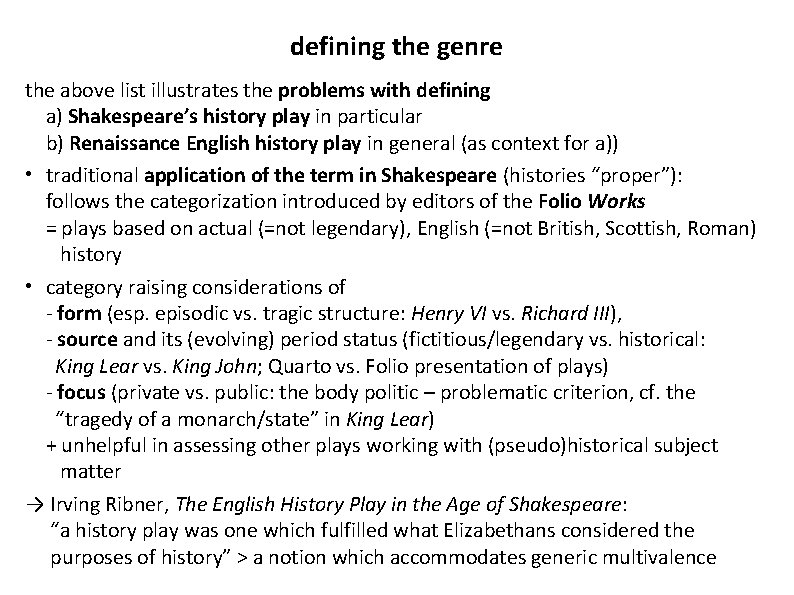

defining the genre the above list illustrates the problems with defining a) Shakespeare’s history play in particular b) Renaissance English history play in general (as context for a)) • traditional application of the term in Shakespeare (histories “proper”): follows the categorization introduced by editors of the Folio Works = plays based on actual (=not legendary), English (=not British, Scottish, Roman) history • category raising considerations of - form (esp. episodic vs. tragic structure: Henry VI vs. Richard III), - source and its (evolving) period status (fictitious/legendary vs. historical: King Lear vs. King John; Quarto vs. Folio presentation of plays) - focus (private vs. public: the body politic – problematic criterion, cf. the “tragedy of a monarch/state” in King Lear) + unhelpful in assessing other plays working with (pseudo)historical subject matter → Irving Ribner, The English History Play in the Age of Shakespeare: “a history play was one which fulfilled what Elizabethans considered the purposes of history” > a notion which accommodates generic multivalence

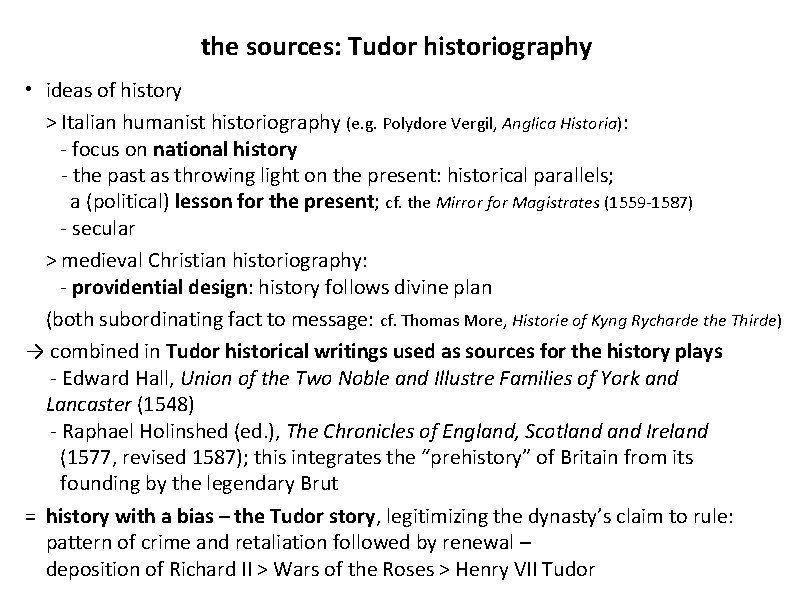

the sources: Tudor historiography • ideas of history > Italian humanist historiography (e. g. Polydore Vergil, Anglica Historia): - focus on national history - the past as throwing light on the present: historical parallels; a (political) lesson for the present; cf. the Mirror for Magistrates (1559 -1587) - secular > medieval Christian historiography: - providential design: history follows divine plan (both subordinating fact to message: cf. Thomas More, Historie of Kyng Rycharde the Thirde) → combined in Tudor historical writings used as sources for the history plays - Edward Hall, Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of York and Lancaster (1548) - Raphael Holinshed (ed. ), The Chronicles of England, Scotland Ireland (1577, revised 1587); this integrates the “prehistory” of Britain from its founding by the legendary Brut = history with a bias – the Tudor story, legitimizing the dynasty’s claim to rule: pattern of crime and retaliation followed by renewal – deposition of Richard II > Wars of the Roses > Henry VII Tudor

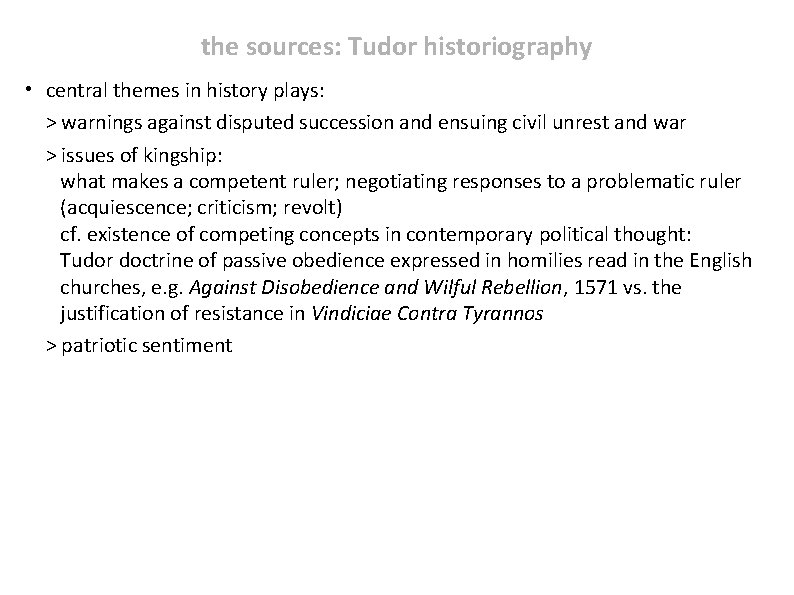

the sources: Tudor historiography • central themes in history plays: > warnings against disputed succession and ensuing civil unrest and war > issues of kingship: what makes a competent ruler; negotiating responses to a problematic ruler (acquiescence; criticism; revolt) cf. existence of competing concepts in contemporary political thought: Tudor doctrine of passive obedience expressed in homilies read in the English churches, e. g. Against Disobedience and Wilful Rebellion, 1571 vs. the justification of resistance in Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos > patriotic sentiment

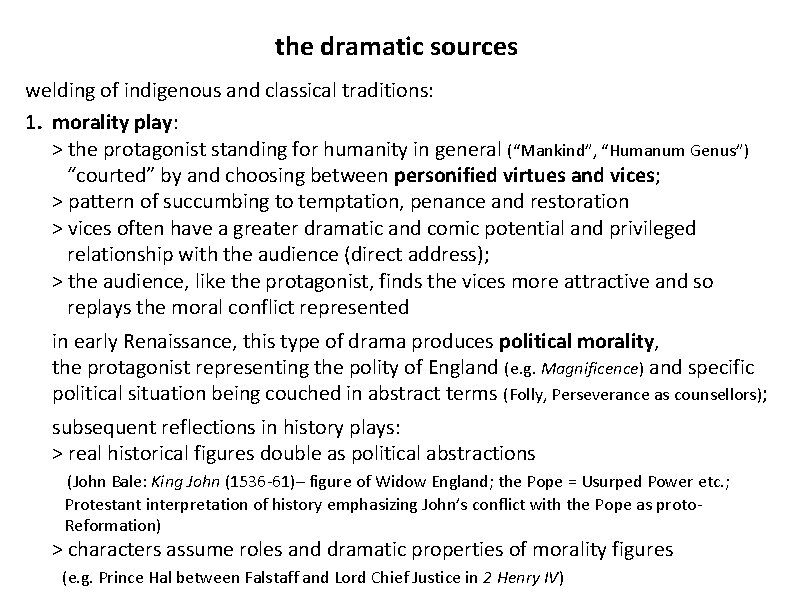

the dramatic sources welding of indigenous and classical traditions: 1. morality play: > the protagonist standing for humanity in general (“Mankind”, “Humanum Genus”) “courted” by and choosing between personified virtues and vices; > pattern of succumbing to temptation, penance and restoration > vices often have a greater dramatic and comic potential and privileged relationship with the audience (direct address); > the audience, like the protagonist, finds the vices more attractive and so replays the moral conflict represented in early Renaissance, this type of drama produces political morality, the protagonist representing the polity of England (e. g. Magnificence) and specific political situation being couched in abstract terms (Folly, Perseverance as counsellors); subsequent reflections in history plays: > real historical figures double as political abstractions (John Bale: King John (1536 -61)– figure of Widow England; the Pope = Usurped Power etc. ; Protestant interpretation of history emphasizing John’s conflict with the Pope as proto. Reformation) > characters assume roles and dramatic properties of morality figures (e. g. Prince Hal between Falstaff and Lord Chief Justice in 2 Henry IV)

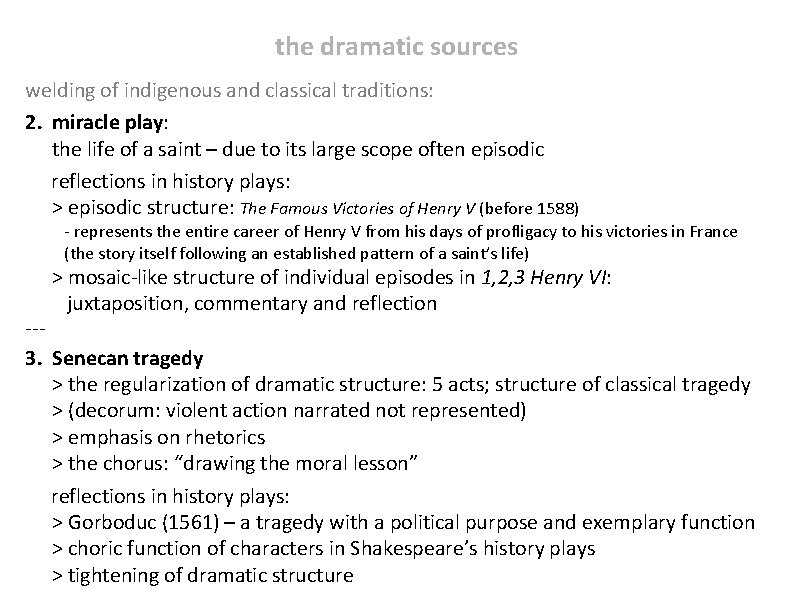

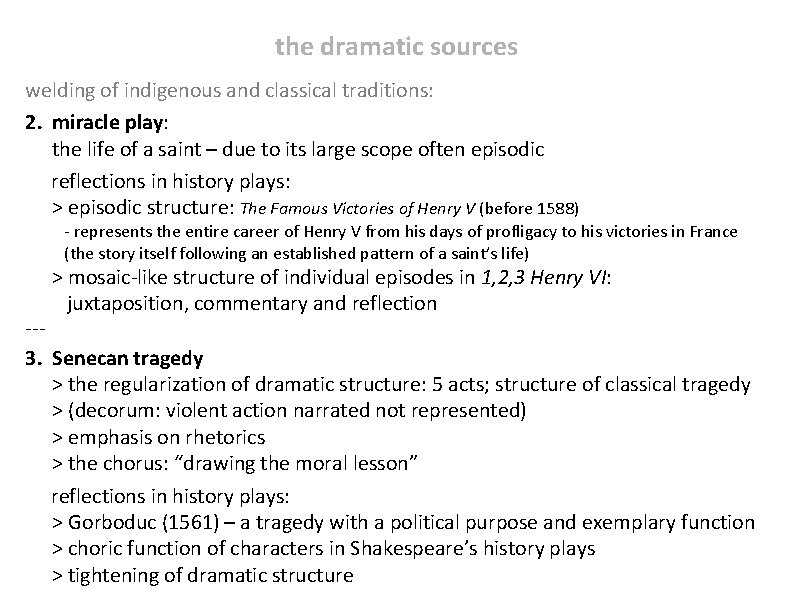

the dramatic sources welding of indigenous and classical traditions: 2. miracle play: the life of a saint – due to its large scope often episodic reflections in history plays: > episodic structure: The Famous Victories of Henry V (before 1588) - represents the entire career of Henry V from his days of profligacy to his victories in France (the story itself following an established pattern of a saint’s life) > mosaic-like structure of individual episodes in 1, 2, 3 Henry VI: juxtaposition, commentary and reflection --3. Senecan tragedy > the regularization of dramatic structure: 5 acts; structure of classical tragedy > (decorum: violent action narrated not represented) > emphasis on rhetorics > the chorus: “drawing the moral lesson” reflections in history plays: > Gorboduc (1561) – a tragedy with a political purpose and exemplary function > choric function of characters in Shakespeare’s history plays > tightening of dramatic structure

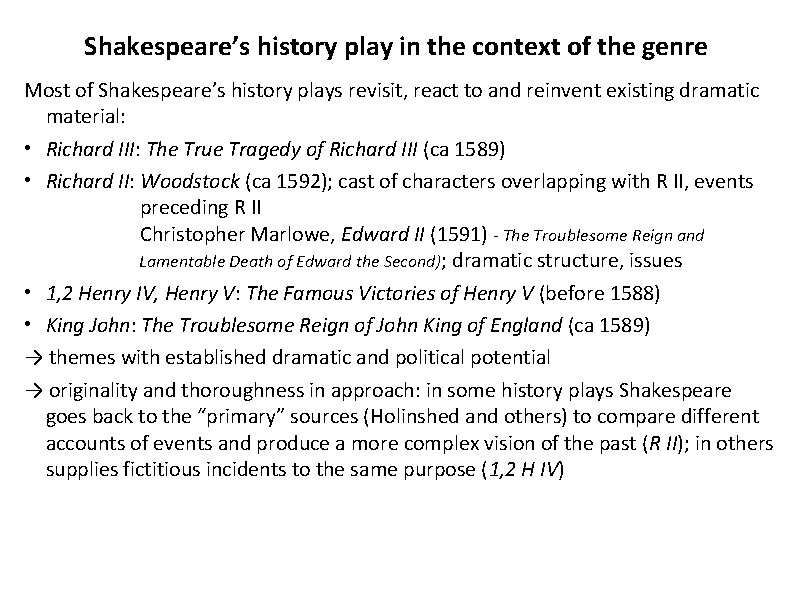

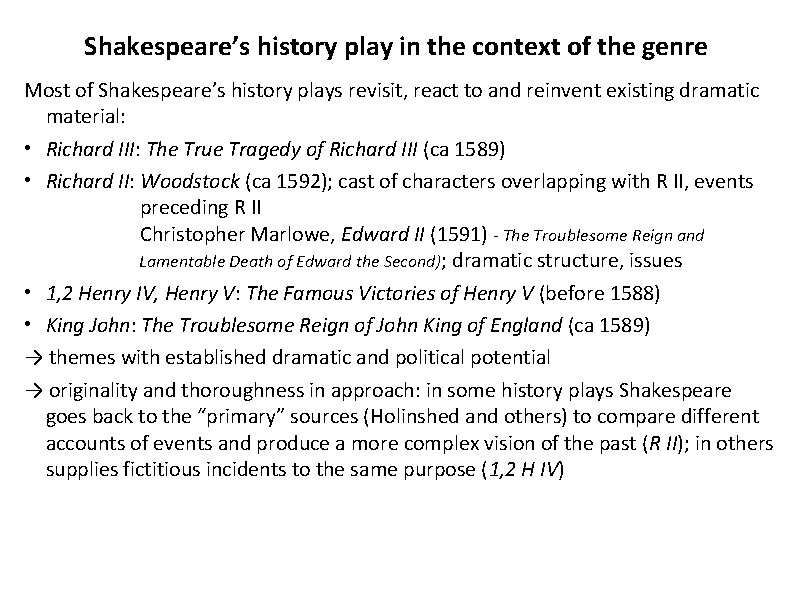

Shakespeare’s history play in the context of the genre Most of Shakespeare’s history plays revisit, react to and reinvent existing dramatic material: • Richard III: The True Tragedy of Richard III (ca 1589) • Richard II: Woodstock (ca 1592); cast of characters overlapping with R II, events preceding R II Christopher Marlowe, Edward II (1591) - The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second); dramatic structure, issues • 1, 2 Henry IV, Henry V: The Famous Victories of Henry V (before 1588) • King John: The Troublesome Reign of John King of England (ca 1589) → themes with established dramatic and political potential → originality and thoroughness in approach: in some history plays Shakespeare goes back to the “primary” sources (Holinshed and others) to compare different accounts of events and produce a more complex vision of the past (R II); in others supplies fictitious incidents to the same purpose (1, 2 H IV)

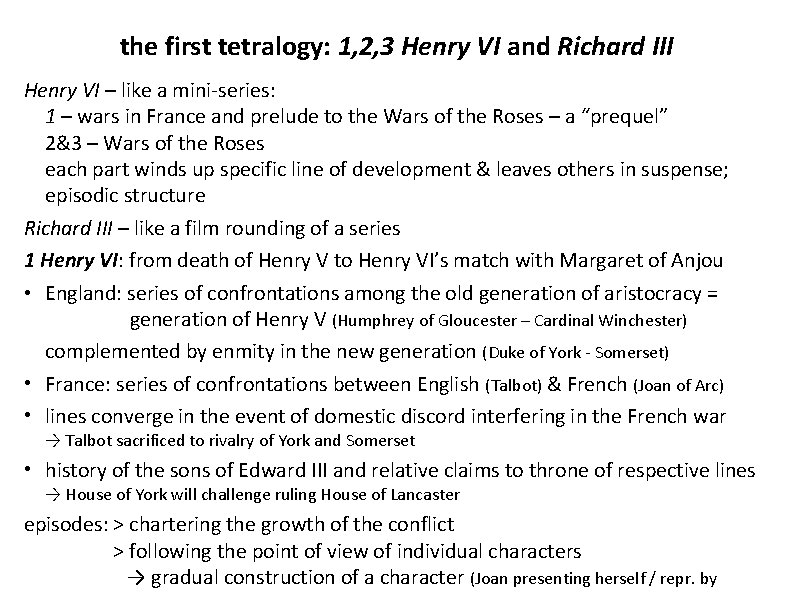

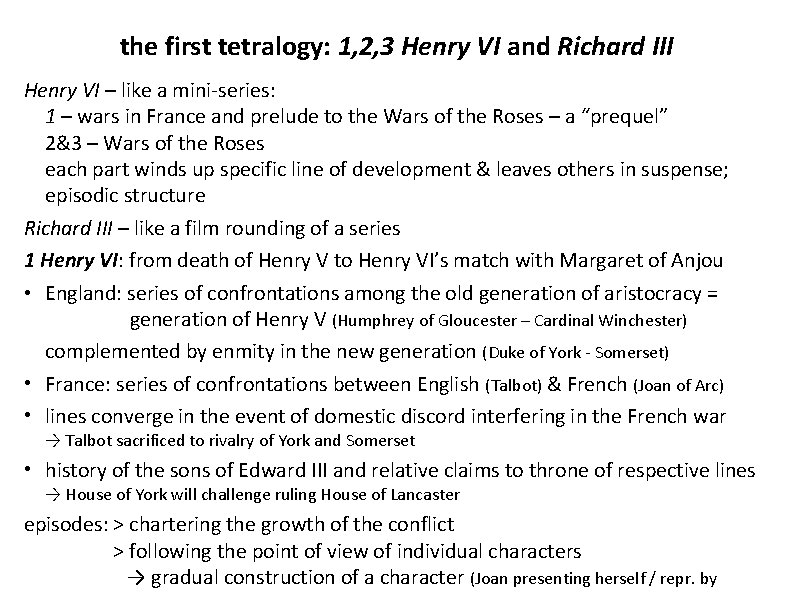

the first tetralogy: 1, 2, 3 Henry VI and Richard III Henry VI – like a mini-series: 1 – wars in France and prelude to the Wars of the Roses – a “prequel” 2&3 – Wars of the Roses each part winds up specific line of development & leaves others in suspense; episodic structure Richard III – like a film rounding of a series 1 Henry VI: from death of Henry V to Henry VI’s match with Margaret of Anjou • England: series of confrontations among the old generation of aristocracy = generation of Henry V (Humphrey of Gloucester – Cardinal Winchester) complemented by enmity in the new generation (Duke of York - Somerset) • France: series of confrontations between English (Talbot) & French (Joan of Arc) • lines converge in the event of domestic discord interfering in the French war → Talbot sacrificed to rivalry of York and Somerset • history of the sons of Edward III and relative claims to throne of respective lines → House of York will challenge ruling House of Lancaster episodes: > chartering the growth of the conflict > following the point of view of individual characters → gradual construction of a character (Joan presenting herself / repr. by

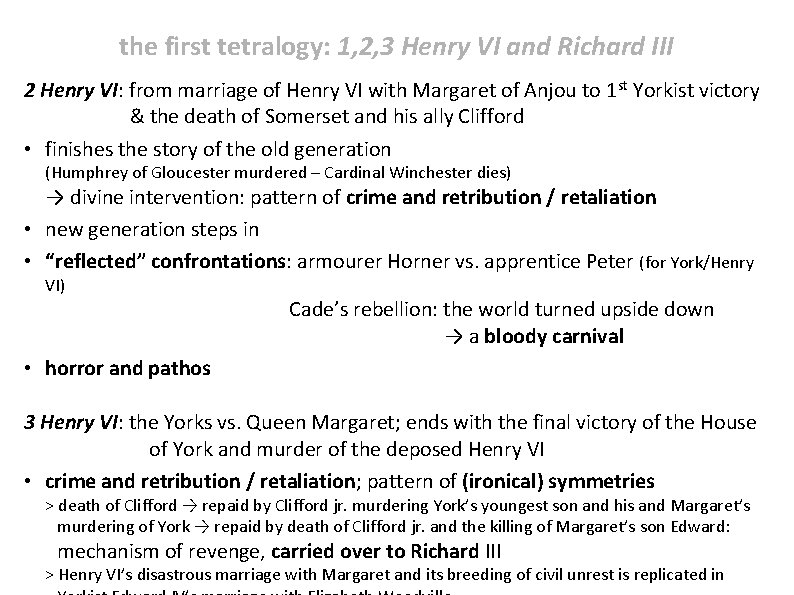

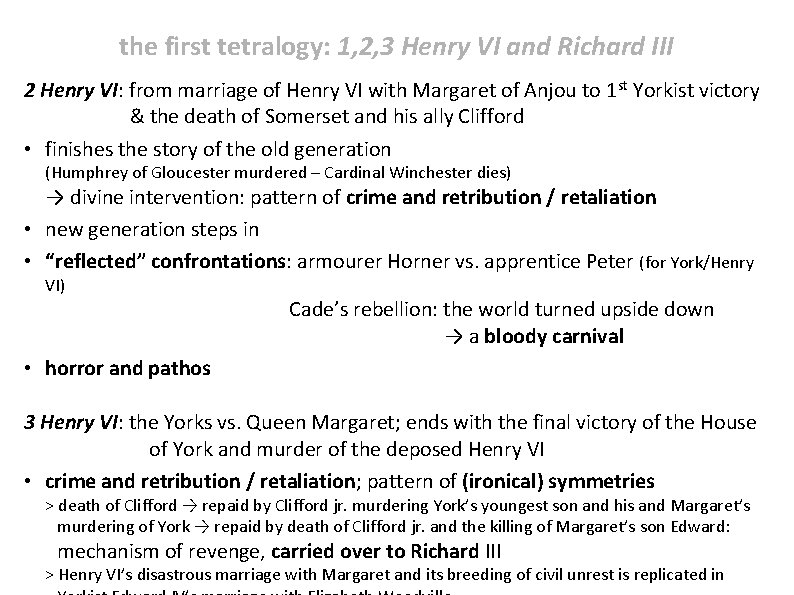

the first tetralogy: 1, 2, 3 Henry VI and Richard III 2 Henry VI: from marriage of Henry VI with Margaret of Anjou to 1 st Yorkist victory & the death of Somerset and his ally Clifford • finishes the story of the old generation (Humphrey of Gloucester murdered – Cardinal Winchester dies) → divine intervention: pattern of crime and retribution / retaliation • new generation steps in • “reflected” confrontations: armourer Horner vs. apprentice Peter (for York/Henry VI) Cade’s rebellion: the world turned upside down → a bloody carnival • horror and pathos 3 Henry VI: the Yorks vs. Queen Margaret; ends with the final victory of the House of York and murder of the deposed Henry VI • crime and retribution / retaliation; pattern of (ironical) symmetries > death of Clifford → repaid by Clifford jr. murdering York’s youngest son and his and Margaret’s murdering of York → repaid by death of Clifford jr. and the killing of Margaret’s son Edward: mechanism of revenge, carried over to Richard III > Henry VI’s disastrous marriage with Margaret and its breeding of civil unrest is replicated in

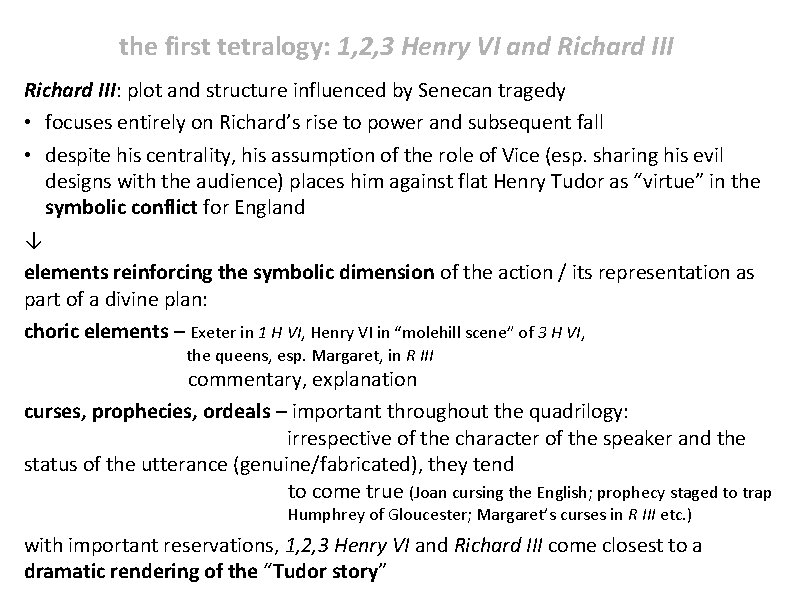

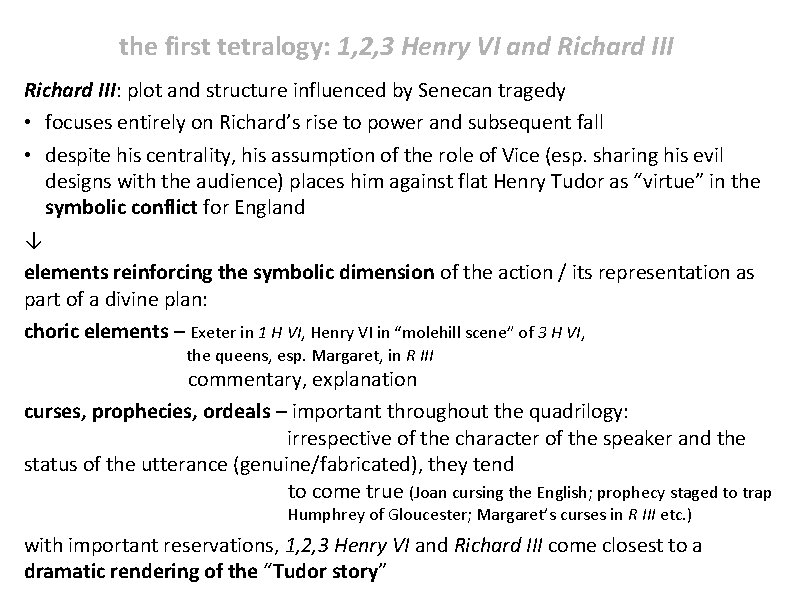

the first tetralogy: 1, 2, 3 Henry VI and Richard III: plot and structure influenced by Senecan tragedy • focuses entirely on Richard’s rise to power and subsequent fall • despite his centrality, his assumption of the role of Vice (esp. sharing his evil designs with the audience) places him against flat Henry Tudor as “virtue” in the symbolic conflict for England ↓ elements reinforcing the symbolic dimension of the action / its representation as part of a divine plan: choric elements – Exeter in 1 H VI, Henry VI in “molehill scene” of 3 H VI, the queens, esp. Margaret, in R III commentary, explanation curses, prophecies, ordeals – important throughout the quadrilogy: irrespective of the character of the speaker and the status of the utterance (genuine/fabricated), they tend to come true (Joan cursing the English; prophecy staged to trap Humphrey of Gloucester; Margaret’s curses in R III etc. ) with important reservations, 1, 2, 3 Henry VI and Richard III come closest to a dramatic rendering of the “Tudor story”

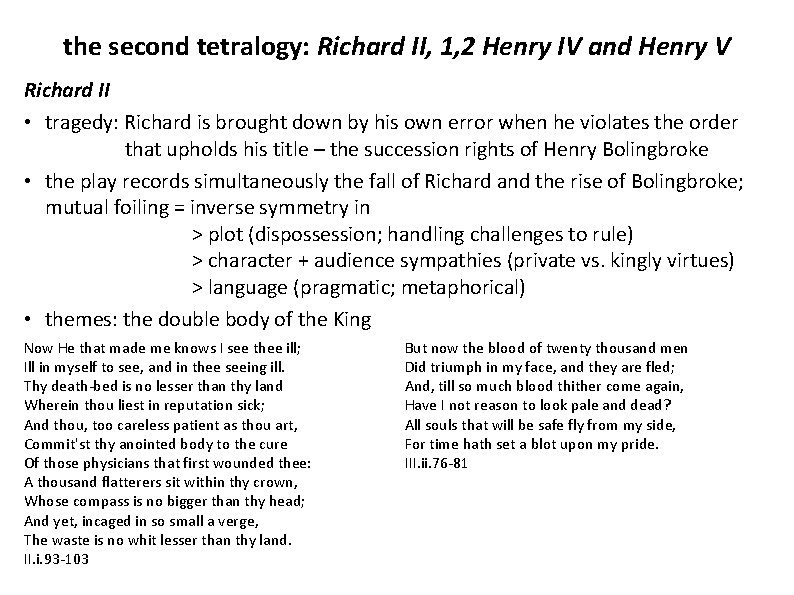

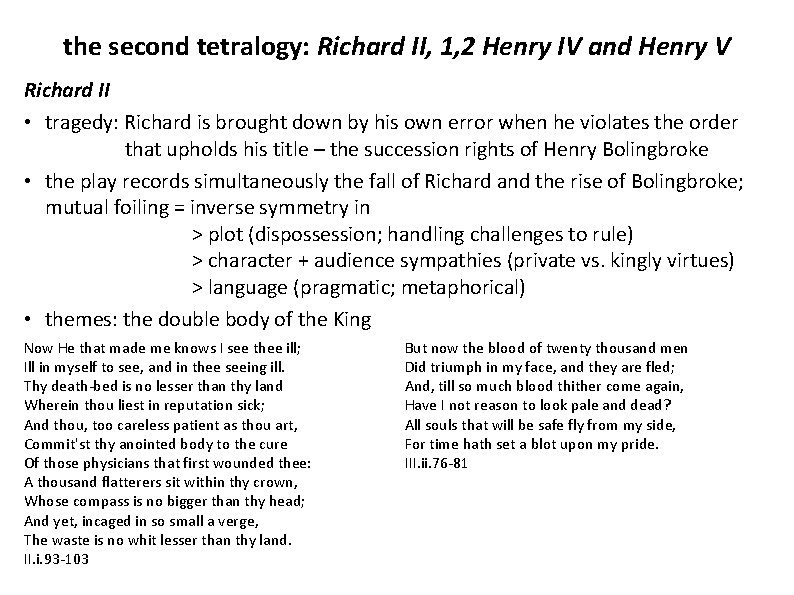

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V Richard II • tragedy: Richard is brought down by his own error when he violates the order that upholds his title – the succession rights of Henry Bolingbroke • the play records simultaneously the fall of Richard and the rise of Bolingbroke; mutual foiling = inverse symmetry in > plot (dispossession; handling challenges to rule) > character + audience sympathies (private vs. kingly virtues) > language (pragmatic; metaphorical) • themes: the double body of the King Now He that made me knows I see thee ill; Ill in myself to see, and in thee seeing ill. Thy death-bed is no lesser than thy land Wherein thou liest in reputation sick; And thou, too careless patient as thou art, Commit'st thy anointed body to the cure Of those physicians that first wounded thee: A thousand flatterers sit within thy crown, Whose compass is no bigger than thy head; And yet, incaged in so small a verge, The waste is no whit lesser than thy land. II. i. 93 -103 But now the blood of twenty thousand men Did triumph in my face, and they are fled; And, till so much blood thither come again, Have I not reason to look pale and dead? All souls that will be safe fly from my side, For time hath set a blot upon my pride. III. ii. 76 -81

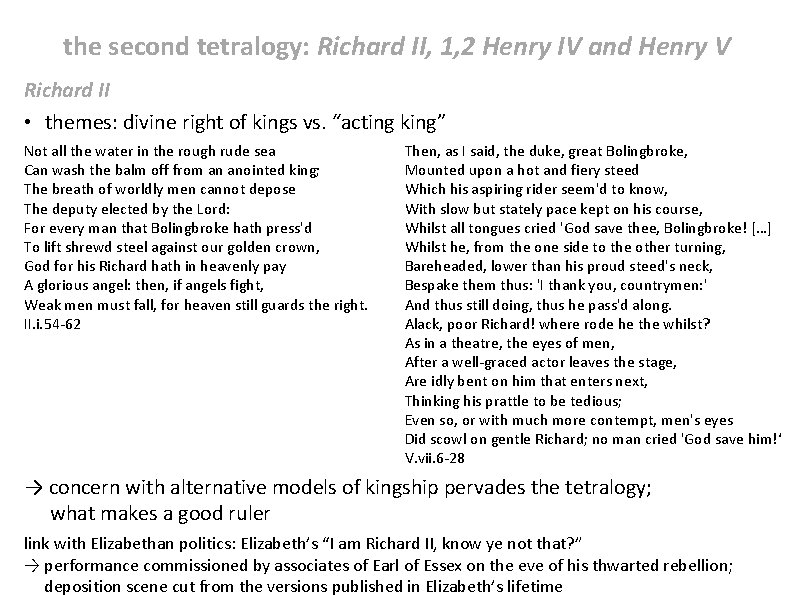

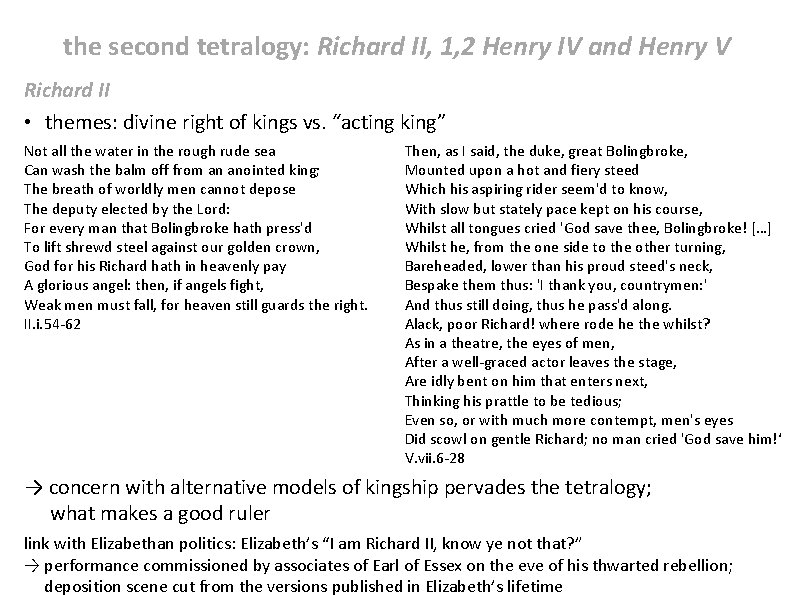

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V Richard II • themes: divine right of kings vs. “acting king” Not all the water in the rough rude sea Can wash the balm off from an anointed king; The breath of worldly men cannot depose The deputy elected by the Lord: For every man that Bolingbroke hath press'd To lift shrewd steel against our golden crown, God for his Richard hath in heavenly pay A glorious angel: then, if angels fight, Weak men must fall, for heaven still guards the right. II. i. 54 -62 Then, as I said, the duke, great Bolingbroke, Mounted upon a hot and fiery steed Which his aspiring rider seem'd to know, With slow but stately pace kept on his course, Whilst all tongues cried 'God save thee, Bolingbroke! […] Whilst he, from the one side to the other turning, Bareheaded, lower than his proud steed's neck, Bespake them thus: 'I thank you, countrymen: ' And thus still doing, thus he pass'd along. Alack, poor Richard! where rode he the whilst? As in a theatre, the eyes of men, After a well-graced actor leaves the stage, Are idly bent on him that enters next, Thinking his prattle to be tedious; Even so, or with much more contempt, men's eyes Did scowl on gentle Richard; no man cried 'God save him!‘ V. vii. 6 -28 → concern with alternative models of kingship pervades the tetralogy; what makes a good ruler link with Elizabethan politics: Elizabeth’s “I am Richard II, know ye not that? ” → performance commissioned by associates of Earl of Essex on the eve of his thwarted rebellion; deposition scene cut from the versions published in Elizabeth’s lifetime

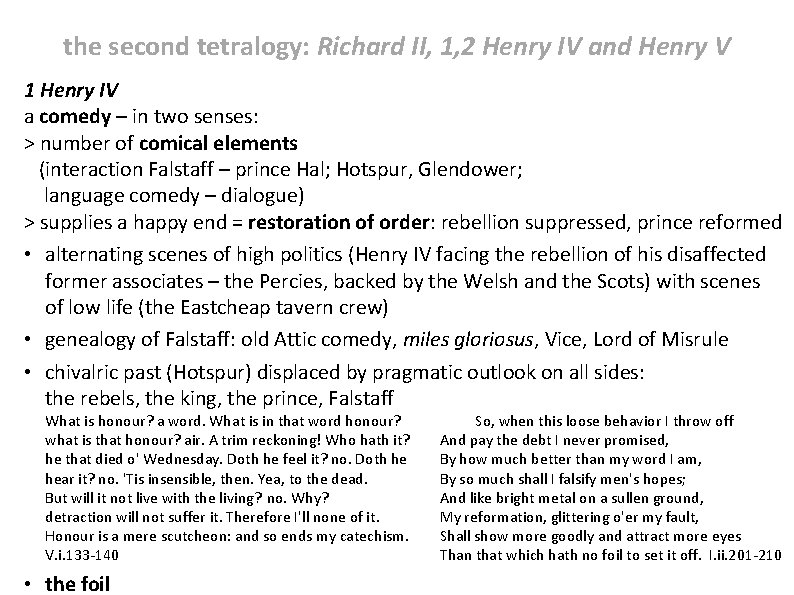

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V 1 Henry IV a comedy – in two senses: > number of comical elements (interaction Falstaff – prince Hal; Hotspur, Glendower; language comedy – dialogue) > supplies a happy end = restoration of order: rebellion suppressed, prince reformed • alternating scenes of high politics (Henry IV facing the rebellion of his disaffected former associates – the Percies, backed by the Welsh and the Scots) with scenes of low life (the Eastcheap tavern crew) • genealogy of Falstaff: old Attic comedy, miles gloriosus, Vice, Lord of Misrule • chivalric past (Hotspur) displaced by pragmatic outlook on all sides: the rebels, the king, the prince, Falstaff What is honour? a word. What is in that word honour? what is that honour? air. A trim reckoning! Who hath it? he that died o' Wednesday. Doth he feel it? no. Doth he hear it? no. 'Tis insensible, then. Yea, to the dead. But will it not live with the living? no. Why? detraction will not suffer it. Therefore I'll none of it. Honour is a mere scutcheon: and so ends my catechism. V. i. 133 -140 • the foil So, when this loose behavior I throw off And pay the debt I never promised, By how much better than my word I am, By so much shall I falsify men's hopes; And like bright metal on a sullen ground, My reformation, glittering o'er my fault, Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes Than that which hath no foil to set it off. I. ii. 201 -210

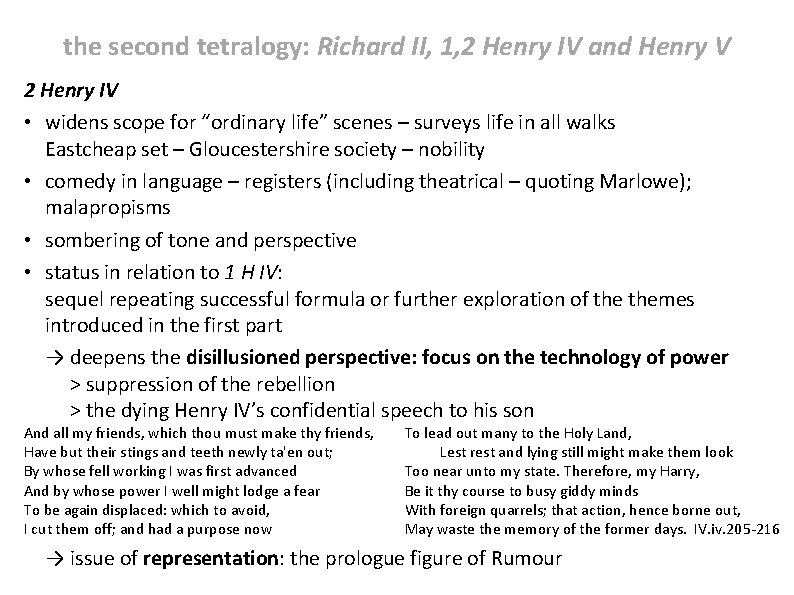

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V 2 Henry IV • widens scope for “ordinary life” scenes – surveys life in all walks Eastcheap set – Gloucestershire society – nobility • comedy in language – registers (including theatrical – quoting Marlowe); malapropisms • sombering of tone and perspective • status in relation to 1 H IV: sequel repeating successful formula or further exploration of themes introduced in the first part → deepens the disillusioned perspective: focus on the technology of power > suppression of the rebellion > the dying Henry IV’s confidential speech to his son And all my friends, which thou must make thy friends, Have but their stings and teeth newly ta'en out; By whose fell working I was first advanced And by whose power I well might lodge a fear To be again displaced: which to avoid, I cut them off; and had a purpose now To lead out many to the Holy Land, Lest rest and lying still might make them look Too near unto my state. Therefore, my Harry, Be it thy course to busy giddy minds With foreign quarrels; that action, hence borne out, May waste the memory of the former days. IV. iv. 205 -216 → issue of representation: the prologue figure of Rumour

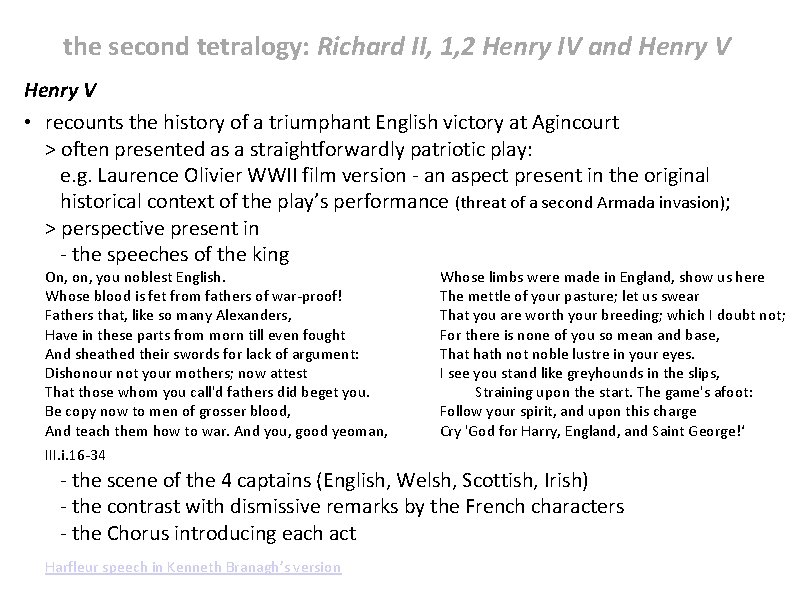

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V • recounts the history of a triumphant English victory at Agincourt > often presented as a straightforwardly patriotic play: e. g. Laurence Olivier WWII film version - an aspect present in the original historical context of the play’s performance (threat of a second Armada invasion); > perspective present in - the speeches of the king On, on, you noblest English. Whose blood is fet from fathers of war-proof! Fathers that, like so many Alexanders, Have in these parts from morn till even fought And sheathed their swords for lack of argument: Dishonour not your mothers; now attest That those whom you call'd fathers did beget you. Be copy now to men of grosser blood, And teach them how to war. And you, good yeoman, Whose limbs were made in England, show us here The mettle of your pasture; let us swear That you are worth your breeding; which I doubt not; For there is none of you so mean and base, That hath not noble lustre in your eyes. I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips, Straining upon the start. The game's afoot: Follow your spirit, and upon this charge Cry 'God for Harry, England, and Saint George!‘ III. i. 16 -34 - the scene of the 4 captains (English, Welsh, Scottish, Irish) - the contrast with dismissive remarks by the French characters - the Chorus introducing each act Harfleur speech in Kenneth Branagh’s version

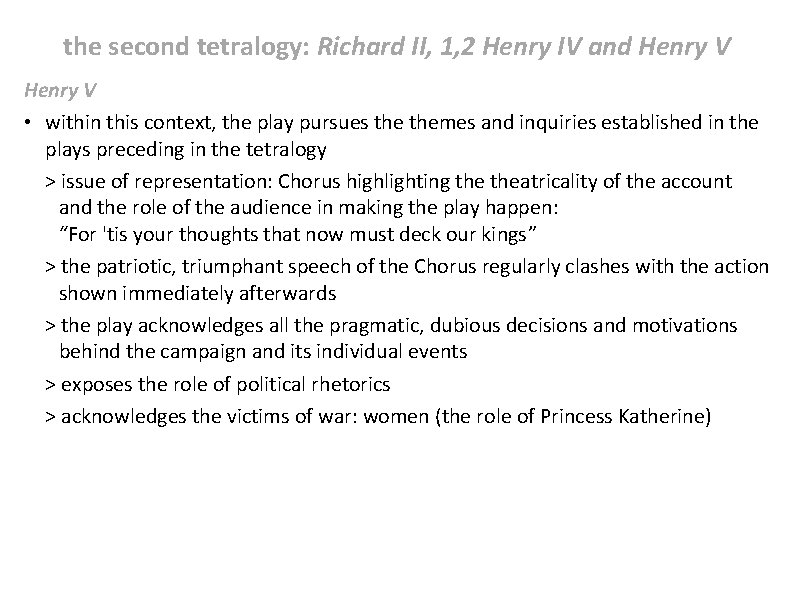

the second tetralogy: Richard II, 1, 2 Henry IV and Henry V • within this context, the play pursues themes and inquiries established in the plays preceding in the tetralogy > issue of representation: Chorus highlighting theatricality of the account and the role of the audience in making the play happen: “For 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings” > the patriotic, triumphant speech of the Chorus regularly clashes with the action shown immediately afterwards > the play acknowledges all the pragmatic, dubious decisions and motivations behind the campaign and its individual events > exposes the role of political rhetorics > acknowledges the victims of war: women (the role of Princess Katherine)

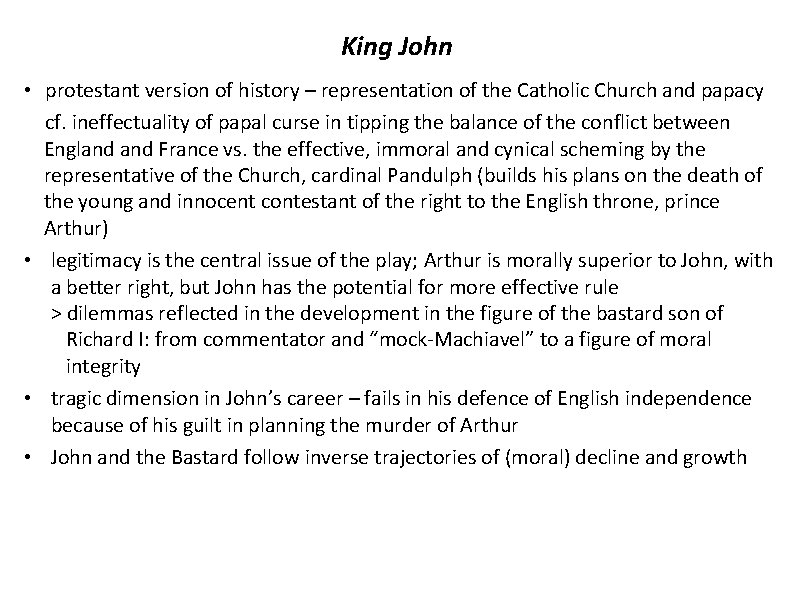

King John • protestant version of history – representation of the Catholic Church and papacy cf. ineffectuality of papal curse in tipping the balance of the conflict between England France vs. the effective, immoral and cynical scheming by the representative of the Church, cardinal Pandulph (builds his plans on the death of the young and innocent contestant of the right to the English throne, prince Arthur) • legitimacy is the central issue of the play; Arthur is morally superior to John, with a better right, but John has the potential for more effective rule > dilemmas reflected in the development in the figure of the bastard son of Richard I: from commentator and “mock-Machiavel” to a figure of moral integrity • tragic dimension in John’s career – fails in his defence of English independence because of his guilt in planning the murder of Arthur • John and the Bastard follow inverse trajectories of (moral) decline and growth

Henry VIII • a late play written in cooperation with John Fletcher; alternative title All is True > raises issues about the nature of historical truth: Be sad, as we would make ye: think ye see The very persons of our noble story As they were living; think you see them great, And follow'd with the general throng and sweat Of thousand friends; then in a moment, see How soon this mightiness meets misery […] Prologue 26 -30 > the play shows momentous events in English history (Henry’s divorce with Catharine of Aragon, marriage with Anne Boleyn, the fall of cardinal Wolsey and the rise of the protestant martyr Thomas Cranmer, birth of Elizabeth) but does not provide a unified perspective of them

permeable borders: “ideas of history” in other plays • King Lear – maps the dissolution of order caused by Lear’s division of his kingdom on personal, political and cosmic level > Gorboduc pattern • Macbeth – contrasting images of tyranny and good kingship (Macbeth / Malcolm) – anatomy of tyranny? – a political dimension of the play connected to the succession of James I – Macbeth’s vision of Banquo’s descendants

Bibliography: Stephen Greenblatt, Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England, University of California Press 1988 Michael Hattaway, ed. , The Cambridge companion to Shakespeare’s History Plays, Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2002 Martin Hilský. Shakespeare a jeviště svět, Praha: Academia 2011 Irving Ribner, The English History Play in the Age of Shakespeare, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press 1957

Miracle and morality plays

Miracle and morality plays Shakespeare 1587

Shakespeare 1587 Themes in othello by william shakespeare

Themes in othello by william shakespeare Shakespeare's tragedy about racism and jealousy

Shakespeare's tragedy about racism and jealousy Where was hamlet born

Where was hamlet born William shakespeare's idioms

William shakespeare's idioms Romeo's father

Romeo's father Fcs launchpad

Fcs launchpad Formulas for career success: résumés - assessment

Formulas for career success: résumés - assessment History of guidance and counselling in the philippines

History of guidance and counselling in the philippines Three types of shakespeare plays

Three types of shakespeare plays Wildcat football plays

Wildcat football plays Morality plays in english literature

Morality plays in english literature Three types of shakespeare plays

Three types of shakespeare plays Character types in shakespeare plays

Character types in shakespeare plays How to cite shakespeare sonnets mla

How to cite shakespeare sonnets mla He plays football

He plays football Definition of one act play

Definition of one act play Morality plays characteristics

Morality plays characteristics Moulding personality meaning

Moulding personality meaning What is liturgical drama

What is liturgical drama Deca role play tips

Deca role play tips Theatre grew out of ritual, which is

Theatre grew out of ritual, which is Double slot offense

Double slot offense