2015 American Academy of Neurology Practice Guideline Idiopathic

- Slides: 53

© 2015 American Academy of Neurology

Practice Guideline Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: Response to Shunting and Predictors of Response Report by: Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) © 2015 American Academy of Neurology

Guideline Endorsement and Funding This guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. Authors who serve as AAN subcommittee members or methodologists (J. J. H. , G. G. , D. G. ) were reimbursed by the AAN for expenses related to travel to subcommittee meetings where drafts of manuscripts were reviewed. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 2

Guideline Authors § John J. Halperin, MD, FAAN § Roger Kurlan, MD, FAAN § Jason M. Schwalb, MD § Michael D. Cusimano, MD, Ph. D, FRCSC § Gary Gronseth, MD, FAAN § David Gloss, MD © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 3

Sharing This Information The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) develops these presentation slides as educational tools for neurologists and other health care practitioners. You may download and retain a single copy for your personal use. Please contact guidelines@aan. com to learn about options for sharing this content beyond your personal use. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 4

Presentation Objectives To present recommendations for utility of shunting in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (i. NPH) and for predictors of shunting effectiveness, based on a systematic review and analysis of the evidence. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 5

Overview § Introduction § Clinical questions § AAN guideline process § Methods § Analysis of evidence/conclusions § Practice recommendations © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 6

Introduction § Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) characterized by: § Clinical triad §Gait disturbance §Urinary incontinence §Memory impairment § Normal CSF pressure on lumbar puncture (LP) § Radiologic finding of enlarged cerebral ventricles © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 7

Table 1: Normal pressure hydrocephalus score used by a number of authors to quantify patients’ limitations Gait Normal Walk with support Requires cane Support by person Urinary incontinence None 5 Cognition None 6 4 Rare incontinence 4 Subjective decrease in memory 5 3 Occasional incontinence 3 Objective decrease in memory but independent 4 2 Constant incontinence 2 Partial loss of independence 3 Permanent catheter 1 Disoriented x 2 2 Institutionalized secondary to dementia 1 5 Wheelchair or bed 1 Reprinted from the British Journal of Neurosurgery (Sorteberg A, Eide PK, Fremming AD. A prospective study on the clinical effect of surgical treatment of normal pressure hydrocephalus: the value of hydrodynamic evaluation. Br J Neurosurg 2004; 18: 149157), © 2004, with permission from Informa Healthcare. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 8

Idiopathic NPH Unknown cause Response to shunting has been described as variable, short-lived, unpredictable, with significant risks Secondary NPH Typically arising from conditions such as subarachnoid hemorrhage and infectious meningitis Ventricular shunting is standard of care § Estimated incidence 2 of 5. 5/100, 000 © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 9

Clinical Questions Clinical Question 1 • Therapeutic question: What is the efficacy of ventricular shunting for i. NPH? Clinical Question 2 • Prognostic question: Are there reliable clinical or laboratory predictors of a successful outcome of shunting (efficacy and successful outcome both defined as a persistent, objectively demonstrable, and clinically meaningful improvement after shunting)? © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 10

AAN Guideline Process* • Clinical Question • Evidence • Conclusions • Recommendations *Guideline developed using the 2004 AAN Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual, except for the conclusions, which were derived according to the process described in the 2011 AAN Clinical Practice Guideline Process Manual. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 11

Literature Search/Review Rigorous, Comprehensive, Transparent 440 abstracts 36 articles © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Searched: Medline, EMBASE, LILACS, and Cochrane databases from 1980 2012; updated search of Medline and Cochrane 2012 to November 2013 Inclusion criteria: Exclusion criteria: • Cohort studies • Case-control studies • Case series • English-language publications • Case reports, editorials, metaanalyses, review articles, duplicative reports • Examined only secondary NPH • <10 patients with i. NPH/suspected i. NPH • Used no comparison group • Followed patients for response to therapy for <3 months Slide 12

AAN Classification of Evidence (2011) Therapeutic Scheme Class I • Randomized, controlled clinical trial (RCT) in a representative population • Masked or objective outcome assessment • Relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent between treatment groups, or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences • Also required: • a. Concealed allocation • b. Primary outcome(s) clearly defined • c. Exclusion/inclusion criteria clearly defined • d. Adequate accounting for dropouts (≤ 80% of enrolled subjects completing the study) and crossovers with numbers sufficiently low to have minimal potential for bias © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 13

AAN Classification of Evidence (2011) Therapeutic Scheme Class I (continued) • e. For noninferiority or equivalence trials claiming to prove efficacy for one or both drugs, the following are also required: • 1. The authors explicitly state the clinically meaningful difference to be excluded by defining the threshold for equivalence or noninferiority • 2. The standard treatment used in the study is substantially similar to that used in previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment (e. g. , for a drug, the mode of administration, dose, and dosage adjustments are similar to those previously shown to be effective) • 3. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient selection and the outcomes of patients on the standard treatment are comparable to those of previous studies establishing efficacy of the standard treatment • 4. The interpretation of the study results is based on a per-protocol analysis that accounts for dropouts or crossovers Note: Objective outcome measurement refers to an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer’s (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e. g. , blood tests, administrative outcome data) © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 14

AAN Classification of Evidence (2011) Therapeutic Scheme Class II* • Cohort study meeting criteria a–e (see Class I description) or an RCT that lacks one or two criteria b–e • All relevant baseline characteristics are presented and substantially equivalent among treatment groups, or there is appropriate statistical adjustment for differences • Masked or objective outcome assessment Note: Objective outcome measurement refers to an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer’s (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e. g. , blood tests, administrative outcome data) *Numbers 1– 3 in Class Ie are required for Class II in equivalence trials. If any one of the three is missing, the class is automatically downgraded to Class III © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 15

AAN Classification of Evidence (2011) Therapeutic Scheme Class III • Controlled studies (including studies with external controls such as welldefined natural history controls) • A description of major confounding differences between treatment groups that could affect outcome • Outcome assessment masked, objective, or performed by someone who is not a member of the treatment team Class IV • Did not include patients with the disease • Did not include patients receiving different interventions • Undefined or unaccepted interventions or outcome measures • No measures of effectiveness or statistical precision presented or calculable Note: Objective outcome measurement refers to an outcome measure that is unlikely to be affected by an observer’s (patient, treating physician, investigator) expectation or bias (e. g. , blood tests, administrative outcome data) © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 16

AAN Classification of Evidence (2004) Prognostic Scheme Class II • A cohort study of a broad spectrum of persons at risk for developing the outcome (e. g. , target disease, work status). The outcome is defined by an acceptable reference standard for case definition. The outcome is objective or measured by an observer who is masked to the presence of the risk factor. Study results allow calculation of measures of prognostic accuracy. • A case-control study of a broad spectrum of persons with the condition compared to a broad spectrum of controls or a cohort study of a broad spectrum of persons at risk for the outcome (e. g. , target disease, work status) where the data was collected retrospectively. The outcome is defined by an acceptable reference standard for case definition. The outcome is objective or measured by an observer who is masked to the presence of the risk factor. Study results allow calculation of measures of prognostic accuracy. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 17

AAN Classification of Evidence (2004) Prognostic Scheme Class III Class IV • A case-control study or a cohort study where either the persons with the condition or the controls are of a narrow spectrum where the data was collected retrospectively. The outcome is defined by an acceptable reference standard for case definition. The outcome is objective or measured by an observer who did not determine the presence of the risk factor. Study results allow calculation of measures of a prognostic accuracy. • Studies not meeting Class I, II, or III criteria, including consensus, expert opinion, or a case report. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 18

AAN Classification of Recommendations Level A • Established as effective, ineffective or harmful (or established as useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. • Requires at least two consistent Class I studies. Level B • Probably effective, ineffective or harmful (or probably useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. • Requires at least one Class I study or two consistent Class II studies. Level C • Possibly effective, ineffective or harmful (or possibly useful/predictive or not useful/predictive) for the given condition in the specified population. • Requires at least one Class II study or two consistent Class III studies. Level U • Data inadequate or conflicting; given current knowledge, treatment (test, predictor) is unproven. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 19

Clinical Question 1 What is the efficacy of ventricular shunting for i. NPH? © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 20

What is the efficacy of ventricular shunting for i. NPH? • The 3 identified studies with higher than Class IV evidence suggest a benefit of shunting for i. NPH, but: § there is a decrease of response after 6 months 5 § fewer than half of patients were considered to be improved in all presenting i. NPH symptoms after 18 monthse 3 • Studies have reported clinical improvement of i. NPH after shunting, but none to date has been designed to provide high-level evidence of efficacy. § It should be recognized that the use of ventricular shunting for i. NPH is based largely on uncontrolled observational studies of clinical response. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 21

Q 1. Analysis of Evidence Efficacy for i. NPH § Class III study 5 § Of 75 patients with NPH (58 with i. NPH): § 54 had positive CSF infusion test (CSF-IT) or CSF tap test (TT) § 21 had negative test results (comparison group—no shunting) § At 6 months: § Significant improvements in gait and “subjective impression of overall improvement, ” improvements in reaction time, memory § After 5 years (43% of shunted patients available) § Measured response decreased § 3 subdural hematomas or effusions (5%), with one requiring surgery; 1 shunt infection; 1 superficial wound infection; 1 pulmonary embolism © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 22

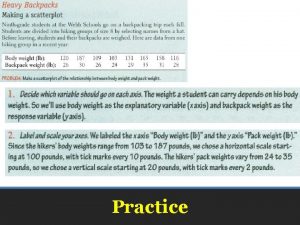

% Improvement in patients with positive CSF TT or CSF-IT Without shunting (6 mos) Memory With shunting (5 yrs) With shunting (6 mos) Reaction time Gait test f-reported overall improvement 0 20 40 60 80 100 Data taken from analysis of the study described on page 2064 of this guideline. 5 © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 23

Q 1. Analysis of Evidence Efficacy for i. NPH § Class III study 9 § 19 patients underwent surgery § After 3 4 months: § 14/18 shunted patients showed marked or moderate improvement on global ratings § 9/14 controls showed marked or moderate worsening § 89% of shunted patients showed moderate to marked improvement on gait measures © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 24

Q 1. Analysis of Evidence Efficacy for i. NPH § Class III study 11 § 93 patients were randomized to undergo lumboperitoneal shunting within 1 month or 3 months of randomization § Improvement of ≥ 1 point on the modified Rankin Scale assessed 3 months after randomization § 32/49 patients in the immediate group improved § 2/44 in the delayed group improved © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 25

Q 1. Conclusions § Shunting is possibly effective for patients with i. NPH § 96% chance of subjective improvement § 83% chance of improvement on the timed walk test at 6 months § 11% risk of serious adverse events § Upgraded strength of evidence from very low to low because of the strong subjective effect § 95% reporting subjective improvement in symptoms, compared with 19% of controls § Among objective measures, only gait improved significantly © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 26

Clinical Question 2 Are there reliable clinical or laboratory predictors of successful outcome of shunting (efficacy and successful outcome both defined as a persistent, objectively demonstrable, and clinically meaningful improvement after shunting)? © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 27

If there is evidence of efficacy, are there clinical or laboratory predictors of a successful outcome? • Identification of Alzheimer pathology at the time of shunting predicts a poor outcomee 4 • There is evidence that improvement in gait following the procedures below may predict a good response to shunting § External lumbar drainage (ELD)22 § MRI-measured high CSF velocity through the aqueduct 26 § Abnormal intracranial CSF hydrodynamics 21 • These procedures are associated with significant cost and potential complications, 40 and in the case of CSF-ITs, the equipment required is not widely available © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 28

Clinical Question 2 a CSF Dynamics and Inclusion Tests • Without an objective reference standard for i. NPH diagnosis, candidates for inclusion had: § all or part of clinical triad § brain imaging studies demonstrating ventriculomegaly § no history of factors that could cause secondary NPH © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 29

Q 2 a. Analysis of Evidence CSF Dynamics and Inclusion Tests § 1 Class IV study 15 (CSF drainage) and 1 Class II study 15 (CSF dynamics) found no relationship between B-wave amplitude or frequency and shunt response 15 § 1 Class I study 14 and 1 Class II study 16 did not show differences in B waves relating to shunt response, but they were underpowered to detect differences © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 30

Q 2 a. Analysis of Evidence CSF Dynamics and Inclusion Tests § 1 Class I study 17 § 142 patients in whom RO was measured preoperatively § No correlation between RO and outcome § At varying levels of RO, positive predictive value as high as 94%, but negative predictive value never exceeded 19% § Multiple Class II studies, 1 Class III study 18– 21 § RO the only measured variable that significantly predicted response © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 31

Q 2 a. Conclusions In patients with suspected i. NPH, those with elevated Ro are probably more likely to respond to shunting than those without elevated Ro, but lower Ro does not preclude shunt responsiveness. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 32

Q 2 b. Analysis of Evidence Comorbidities § 1 Class II study 22 § In patients responding to ELD, shunt response was independent of age up to the ninth decade § 1 Class III study 21 § Overall, 66% of patients with i. NPH had a good response, but 83% of those with low comorbidity index score had a good response © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 33

Table 2. Comorbidity index 1 point 2 points 3 points Vascular risk factors Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Peripheral vascular occlusion Aortofemoral bypass; stent; internal carotid artery stenosis Peripheral vascular occlusion Cerebrovascular disease Posterior circulation insufficiency Vascular encephalopathy; TIA; PRIND Cerebral infarct Heart Arrhythmia; valvular disease; heart failure (coronal); stent; aortocoronary bypass; infarction Abbreviation: PRIND = prolonged reversible ischemic neurologic deficit. Each mentioned symptom or disease has to be assigned according to the indicated parameter-values (1– 3 points). The sum represents the individual comorbidity index. Reprinted from Acta Neurochirurgica Supplement (Kiefer M, Eymann R, Steudel WI. Outcome predictors for normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2006; 96: 364 367), © 2004, with permission from Springer. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 34

Q 2 b. Conclusions Age is possibly not an independent risk factor for poor shunt response. In patients with suspected i. NPH, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether those with 3 or more major comorbidities are likely to respond less favorably to shunting than those with fewer comorbidities. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 35

Q 2 c. Analysis of Evidence Tap Test/External Lumbar Drainage § 1 Class III study 23 § Improvement with ELD predicted shunt response § 16/19 who improved with ELD improved in measurement of gait with shunting § 1 Class I study 17 § Found no correlation between results of tap tests (TTs) and outcome § Population preselected on the basis of clinical and imaging criteria; positive predictive value of the TT was 88% but negative predictive value only 18%, resulting in an overall accuracy of 53% © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 36

Q 2 c. Conclusions In patients with suspected i. NPH, there is insufficient high-quality evidence to conclude that improvement in response to ELD predicts response to shunting. Patients who improve after TTs may be more likely to respond to shunting, but negative TTs do not preclude a response to shunting. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 37

Q 2 d. Analysis of Evidence CBF and Acetazolamide Reactivity § 1 Class I study 24 § SPECT cerebral blood flow (CBF) in responders was no different from CBF in controls or nonresponders § CBF reactivity to acetazolamide was significantly impaired in responders compared with controls and nonresponders © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 38

Q 2 d. Conclusions In patients with suspected i. NPH, those with impaired CBF reactivity to acetazolamide are possibly more likely to respond to shunting than those without impaired CBF reactivity to acetazolamide. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 39

Q 2 e. Analysis of Evidence MRI Aqueductal CSF Flow § 1 Class II study 25 § Shunting followed by §Improved gait (86%) §Improved continence (69%) §Improved cognitive function (44%) § Elevated aqueductal flow rate did not predict the response of any aspect of function, although all patients with rates >33 m. L/min did improve © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 40

Q 2 e. Analysis of Evidence MRI Aqueductal CSF Flow § 3 Class III studies 26– 28 § Study 1: Values greater than appx. 10 mm/s considered elevated § 28/29 improved with shunting (elevated velocities) § 3/4 improved with shunting (normal velocities) § Study 2: MRI sensitivity was 46%, and specificity was 95% for i. NPH § Study 3: Stratified aqueductal CSF stroke volume (low, medium, and high) §No relationship between this measure and shunt response © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 41

Q 2 e. Conclusions Patients with suspected i. NPH who have highvelocity aqueductal flow on MRI scan and an abnormal CSF infusion test (CSF-IT) are possibly more likely to respond to shunting. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 42

Q 2. Other Conclusions 1 Class III cohort 29, 30 In patients with suspected i. NPH, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether those with moderate to severe neuropathologic findings of Alzheimer disease are likely to respond less favorably to shunting than those without Alzheimer pathology. 1 Class II study There is insufficient evidence to determine whether the detection (downgraded for of periventricular hyperintensities on imaging is predictive of lack of precision)31 shunt response in patients with suspected i. NPH. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether patients with Class IV evidence suspected i. NPH and persistent ventricular stasis on radioisotope only 31 cisternography would respond to shunting. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 43

Clinical Context • None of the studies cited in therapeutic section provided high-level evidence of shunt efficacy • However, in other studies, more than 80% of patients shunted on the basis of results from TTs, 31 ELD, 23 and CSF -ITs 18, 19 improved © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 44

Clinical Context 120% % Pts improved, based on test 100% 80% 60% unselected - test + test 40% 20% 0% ELD tap test CSF puls Ro >13 Ro >=18 Hyper velo MRI Aq Aq vel >= SV 25. 5 TT Ro>12 -20% Figure 1. Percentage of patients improving with shunting in each of the 10 described studies © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 45

Clinical Context • Shunting is associated with significant cost and potential morbidity and mortality • In addition to the costs of hospitalization and surgery, patients with implanted shunts are at risk of shunt failure, ventriculitis, and shunt infections • Prolonged lumbar drainage is associated with a risk of meningitis and death 39, 40 © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 46

Practice Recommendations Level B © 2015 American Academy of Neurology • Because there is a risk of significant AEs, the risks and benefits of the procedure should be carefully weighed • Clinicians should inform patients with i. NPH with elevated Ro that they have an increased chance of responding to shunting compared with those without such elevation Slide 47

Practice Recommendations • Clinicians may choose to offer shunting as a treatment for patients with i. NPH in order to treat their gait and subjective symptoms of i. NPH Level C • Clinicians may counsel patients with i. NPH that an abnormal CSF-IT or a positive response to repeated lumbar punctures increases the chance of response to shunting • Clinicians may counsel patients with i. NPH and their families that increasing age does not necessarily decrease the chance of a shunt being successful • Clinicians may counsel patients with suspected i. NPH and with impaired CBF reactivity to acetazolamide, measured by SPECT, that they are possibly more likely to respond to shunting © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 48

Recommendations for Future Research Well-designed clinical trials are needed • Control intervention • Randomized assignment • Treatment masking • More objective outcome measures • Sufficiently long observation period • Considerations of: • Possible Alzheimer disease • Comorbidities and functional status Properly performed studies of diagnosis, predictors, and treatment are essential © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 49

References cited here can be found in the summary article and e-references to the summary article (an online data supplement to the summary article). To locate these materials, please visit AAN. com/guidelines. © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 50

Access Guideline and Summary Tools • To access the complete guideline and related summary tools, visit AAN. com/guidelines. • Summary guideline article • Complete guideline article (available as a data supplement to the published summary) • Summary for clinicians and summary for patients/families © 2015 American Academy of Neurology Slide 51

Questions? © 2015 American Academy of Neurology

Ideopathic peripheral neuropathy

Ideopathic peripheral neuropathy Idiopathic hirsutism

Idiopathic hirsutism Idiopathic oat

Idiopathic oat Pediatric surgery

Pediatric surgery Asam national practice guideline

Asam national practice guideline Kdigo 2012 clinical practice guideline

Kdigo 2012 clinical practice guideline Cushing syndrome mnemonic

Cushing syndrome mnemonic Code of practice 2015

Code of practice 2015 Waikato stormwater management guideline

Waikato stormwater management guideline Interview guideline template

Interview guideline template Anemia in pregnancy guideline

Anemia in pregnancy guideline Autoanamnesa

Autoanamnesa Patient safety incident definition

Patient safety incident definition Msqh standard

Msqh standard Pertanyaan anamnesa psikologi

Pertanyaan anamnesa psikologi East practice management guidelines

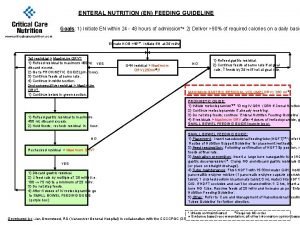

East practice management guidelines En feeding guide

En feeding guide Notching hair definition

Notching hair definition What is a guideline for hoisting a hoseline?

What is a guideline for hoisting a hoseline? Turnball warning

Turnball warning 5 guideline for cumbersome calculations

5 guideline for cumbersome calculations Formal multiplication rule

Formal multiplication rule Who guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies

Who guideline on country pharmaceutical pricing policies Outside counsel billing guideline creation

Outside counsel billing guideline creation Ccgi guidelines

Ccgi guidelines Acg chronic pancreatitis

Acg chronic pancreatitis Bpfk cosmetic guideline

Bpfk cosmetic guideline Leischker

Leischker Disconnected epidural catheter guideline

Disconnected epidural catheter guideline Escardio

Escardio Asean stability guideline

Asean stability guideline Srm process flow

Srm process flow Mfmea example

Mfmea example American academy of financial management

American academy of financial management Griffin concierge medical cost

Griffin concierge medical cost American beauty academy

American beauty academy American academy of oral and maxillofacial radiology

American academy of oral and maxillofacial radiology American academy of witchcraft arts

American academy of witchcraft arts Academy of physical medicine

Academy of physical medicine American academy of allergy asthma and immunology 2018

American academy of allergy asthma and immunology 2018 The walton centre for neurology and neurosurgery

The walton centre for neurology and neurosurgery Motor strength scale

Motor strength scale Vanderbilt epilepsy monitoring unit

Vanderbilt epilepsy monitoring unit Alemutuzumab

Alemutuzumab Mary bridge neurology

Mary bridge neurology Neurology sonography

Neurology sonography Robert layzer md

Robert layzer md Family medicine shelf percentile

Family medicine shelf percentile Rrerl

Rrerl Nlff neuro

Nlff neuro Nex exam neurology

Nex exam neurology Mppd unhas

Mppd unhas Raeburn forbes

Raeburn forbes Nin bajaj

Nin bajaj