Rough Guide to Assessment Methods Dr John Unsworth

![References Baume, D. A. (2001) Briefing on the Assessment of Portfolios. [Online]. Available at: References Baume, D. A. (2001) Briefing on the Assessment of Portfolios. [Online]. Available at:](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/6d85e501801456028424c8780bf1cc36/image-38.jpg)

- Slides: 40

Rough Guide to Assessment Methods Dr John Unsworth and colleagues

Content Introduction Concepts in assessment Validity, Reliability and Educational Impact Knows / Knows How Factsheets: assessment methods focused on knowledge and the application of knowledge Shows Does References Factsheets: assessment methods focused on demonstrating competence (in vitro) Factsheets: assessment of performance (in vivo)

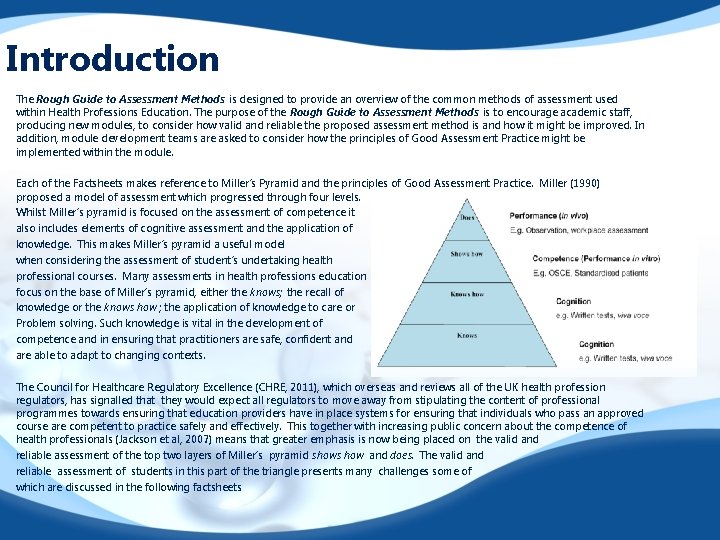

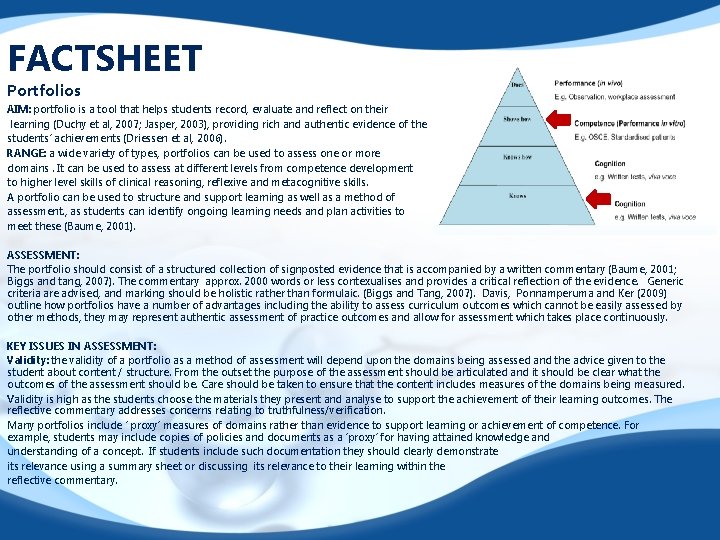

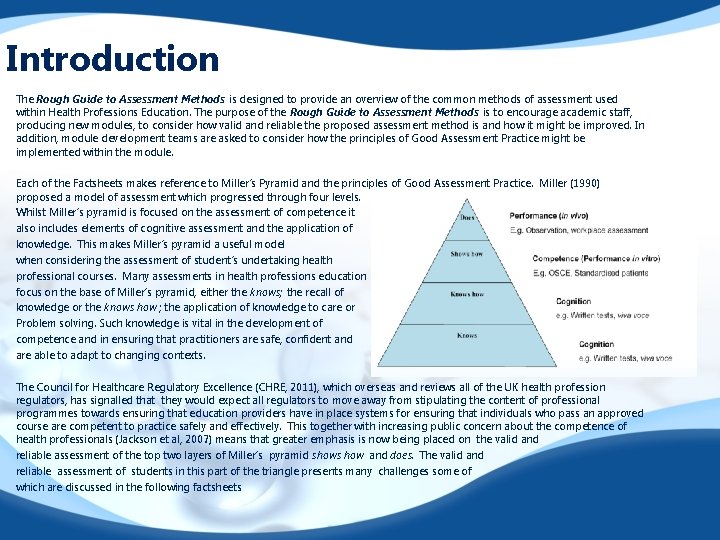

Introduction The Rough Guide to Assessment Methods is designed to provide an overview of the common methods of assessment used within Health Professions Education. The purpose of the Rough Guide to Assessment Methods is to encourage academic staff, producing new modules, to consider how valid and reliable the proposed assessment method is and how it might be improved. In addition, module development teams are asked to consider how the principles of Good Assessment Practice might be implemented within the module. Each of the Factsheets makes reference to Miller’s Pyramid and the principles of Good Assessment Practice. Miller (1990) proposed a model of assessment which progressed through four levels. Whilst Miller’s pyramid is focused on the assessment of competence it also includes elements of cognitive assessment and the application of knowledge. This makes Miller’s pyramid a useful model when considering the assessment of student’s undertaking health professional courses. Many assessments in health professions education focus on the base of Miller’s pyramid, either the knows; the recall of knowledge or the knows how ; the application of knowledge to care or Problem solving. Such knowledge is vital in the development of competence and in ensuring that practitioners are safe, confident and are able to adapt to changing contexts. The Council for Healthcare Regulatory Excellence (CHRE, 2011), which overseas and reviews all of the UK health profession regulators, has signalled that they would expect all regulators to move away from stipulating the content of professional programmes towards ensuring that education providers have in place systems for ensuring that individuals who pass an approved course are competent to practice safely and effectively. This together with increasing public concern about the competence of health professionals (Jackson et al, 2007) means that greater emphasis is now being placed on the valid and reliable assessment of the top two layers of Miller’s pyramid shows how and does. The valid and reliable assessment of students in this part of the triangle presents many challenges some of which are discussed in the following factsheets

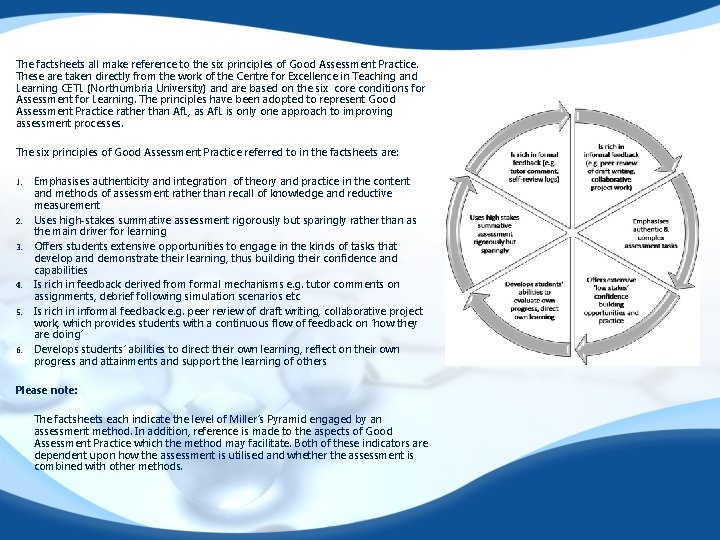

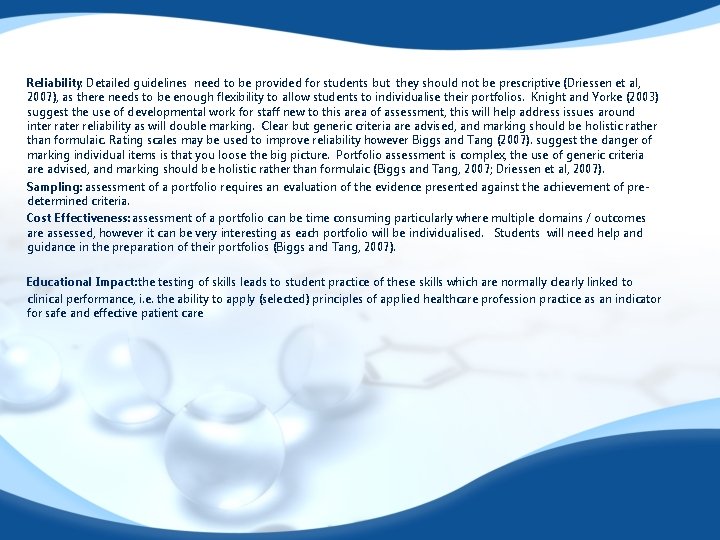

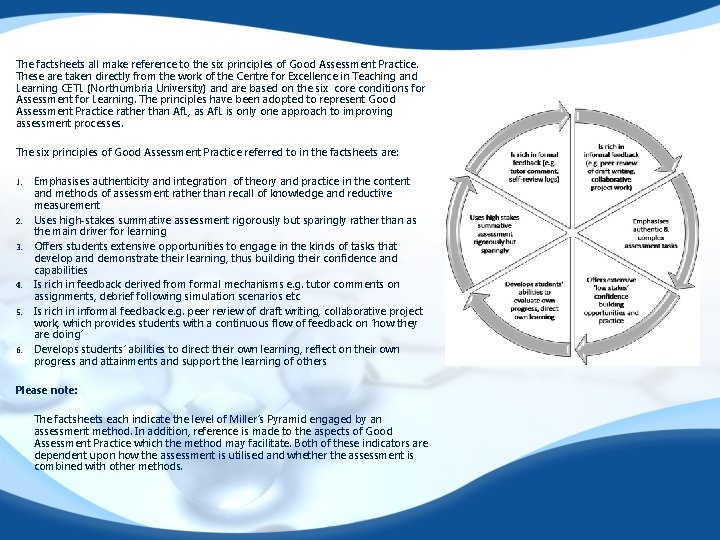

The factsheets all make reference to the six principles of Good Assessment Practice. These are taken directly from the work of the Centre for Excellence in Teaching and Learning CETL (Northumbria University) and are based on the six core conditions for Assessment for Learning. The principles have been adopted to represent Good Assessment Practice rather than Af. L, as Af. L is only one approach to improving assessment processes. The six principles of Good Assessment Practice referred to in the factsheets are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Emphasises authenticity and integration of theory and practice in the content and methods of assessment rather than recall of knowledge and reductive measurement Uses high-stakes summative assessment rigorously but sparingly rather than as the main driver for learning Offers students extensive opportunities to engage in the kinds of tasks that develop and demonstrate their learning, thus building their confidence and capabilities Is rich in feedback derived from formal mechanisms e. g. tutor comments on assignments, debrief following simulation scenarios etc Is rich in informal feedback e. g. peer review of draft writing, collaborative project work, which provides students with a continuous flow of feedback on ‘how they are doing’ Develops students’ abilities to direct their own learning, reflect on their own progress and attainments and support the learning of others Please note: The factsheets each indicate the level of Miller’s Pyramid engaged by an assessment method. In addition, reference is made to the aspects of Good Assessment Practice which the method may facilitate. Both of these indicators are dependent upon how the assessment is utilised and whether the assessment is combined with other methods.

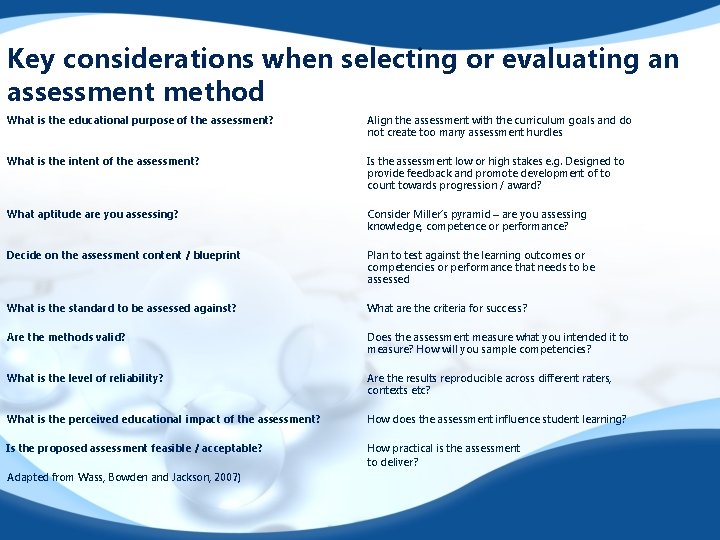

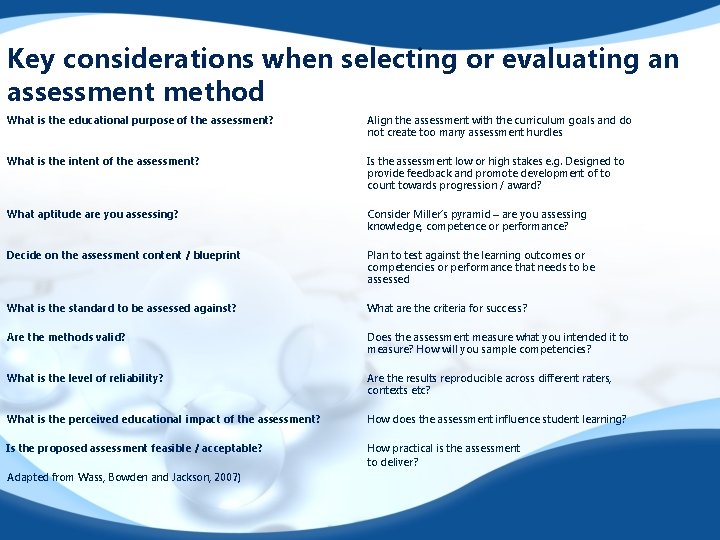

Key considerations when selecting or evaluating an assessment method What is the educational purpose of the assessment? Align the assessment with the curriculum goals and do not create too many assessment hurdles What is the intent of the assessment? Is the assessment low or high stakes e. g. Designed to provide feedback and promote development of to count towards progression / award? What aptitude are you assessing? Consider Miller’s pyramid – are you assessing knowledge, competence or performance? Decide on the assessment content / blueprint Plan to test against the learning outcomes or competencies or performance that needs to be assessed What is the standard to be assessed against? What are the criteria for success? Are the methods valid? Does the assessment measure what you intended it to measure? How will you sample competencies? What is the level of reliability? Are the results reproducible across different raters, contexts etc? What is the perceived educational impact of the assessment? How does the assessment influence student learning? Is the proposed assessment feasible / acceptable? How practical is the assessment to deliver? Adapted from Wass, Bowden and Jackson, 2007)

Concepts in assessment Validity: Validity in assessment relates to whether the method of assessment actually measures what it seeks to measure. There are no inherently good or bad assessment methods, they are all relative to the context in which they are implemented and can be used to assess different aspects of a student’s ability at different stages in their development (van der Vleuten and Schuwirth, 2005). Therefore, a valid assessment would consider the domain or competencies it sought to assess and ensure that it measured those areas. There are many different types of validity which are relevant to assessment e. g. content, predictive, construct etc. The modern view is that validity is a single unitary construct and therefore construct validity (which involves considering the validity of the assessment as a whole) is of significant importance (Messick, 1995). Within the education of health professionals, construct validity also relates to the need to assess the integration of multiple competencies and knowledge which practitioners need in order to practice safely and effectively. This requires assessments which move away from assessingle aspects of a student performance e. g. knowledge, towards assessing competency through global ratings of performance, multi-source feedback and through the use of multi-faceted authentic methods of assessment either in the workplace (in-vivo) or during simulation scenarios / objective structured clinical examinations (OSCE) (in-vitro). Reliability: Reliability irelates to the degree to which an assessment consistently measures what it measures (Mc. Coubrie, 2010). As a result, reliability relates to the reproducibility of the assessment results consistently between assessors and across samples of assessments. The reliability of an assessment can be negatively affected by sources of error such as assessor error, poor quality test items or behavioural rating scales that have ambiguous criteria and poor differentiation between gradings. Reliability of an assessment method can be improved by careful training and instruction of assessors, and by having multiple assessors and triangulation of scores.

When assessing competence van der Vleuten and Schuwirth (2005) have highlighted the need to ensure effective sampling of skills across a time period, as student / practitioner performance is inconsistent and therefore 7 -11 ratings over a period of time will improve the reliability of the assessment when compared with a single rating of performance. Educational Impact: Wass et al (2001) have postulated that ‘assessment drives learning’, insomuch as, student’s when faced with a high workload will focus on learning what they need to learn in order to pass the assessment. As a result when the focus is on a written assessment then student focus on learning from books and journals but when the focus is on a practical skill students tend to rehearse their skills in a clinical context (Newble and Jaegar, 1983). However, it is not as simple as student focusing learning on the specifics of the assessment method. There are several ways in which learning can be influenced by assessment. These include the content of the assessment, the format of the assessment and through the feedback provided to students following the assessment. In addition, Mc. Lachlan (2006) has articulated how students learn subjects which are not explicitly examined. This learning occurs because students are exposed to a range of factors which influence their thinking about what is important. For example, students often share experiences with their fellow students which can assist in a student identifying discrepancy between their knowledge or skills when compared with their peers.

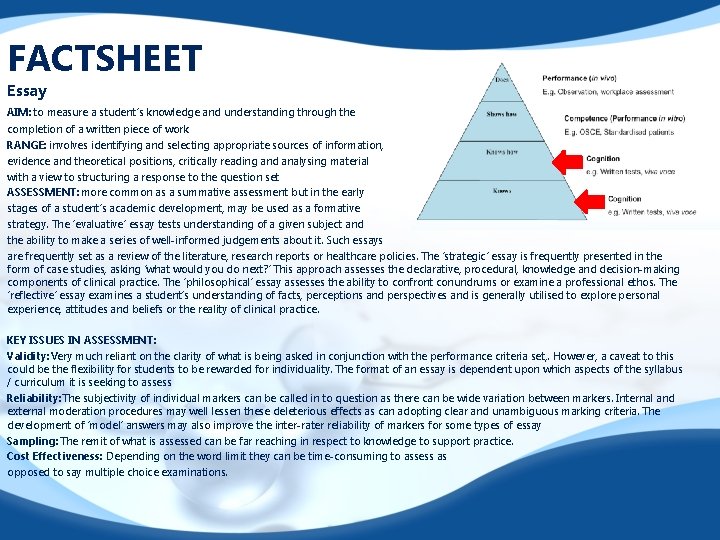

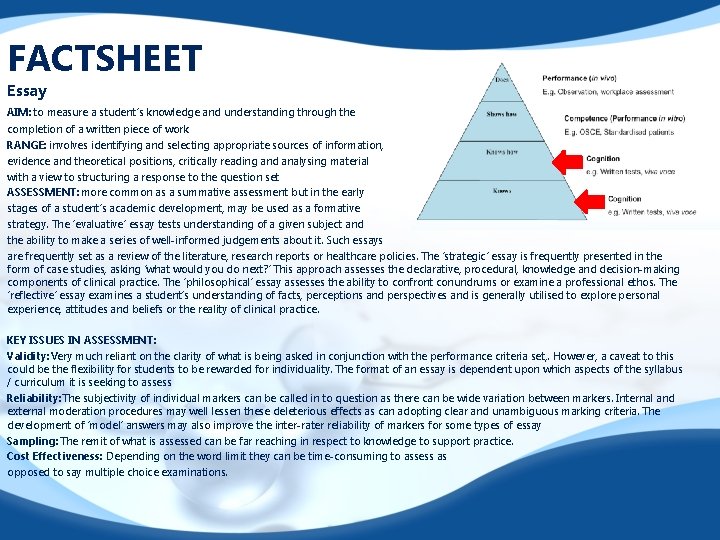

FACTSHEET Essay AIM: to measure a student’s knowledge and understanding through the completion of a written piece of work RANGE: involves identifying and selecting appropriate sources of information, evidence and theoretical positions, critically reading and analysing material with a view to structuring a response to the question set ASSESSMENT: more common as a summative assessment but in the early stages of a student’s academic development, may be used as a formative strategy. The ‘evaluative’ essay tests understanding of a given subject and the ability to make a series of well-informed judgements about it. Such essays are frequently set as a review of the literature, research reports or healthcare policies. The ‘strategic’ essay is frequently presented in the form of case studies, asking ‘what would you do next? ’ This approach assesses the declarative, procedural, knowledge and decision-making components of clinical practice. The ‘philosophical’ essay assesses the ability to confront conundrums or examine a professional ethos. The ‘reflective’ essay examines a student’s understanding of facts, perceptions and perspectives and is generally utilised to explore personal experience, attitudes and beliefs or the reality of clinical practice. KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: Very much reliant on the clarity of what is being asked in conjunction with the performance criteria set, . However, a caveat to this could be the flexibility for students to be rewarded for individuality. The format of an essay is dependent upon which aspects of the syllabus / curriculum it is seeking to assess Reliability: The subjectivity of individual markers can be called in to question as there can be wide variation between markers. Internal and external moderation procedures may well lessen these deleterious effects as can adopting clear and unambiguous marking criteria. The development of ‘model’ answers may also improve the inter-rater reliability of markers for some types of essay Sampling: The remit of what is assessed can be far reaching in respect to knowledge to support practice. Cost Effectiveness: Depending on the word limit they can be time-consuming to assess as opposed to say multiple choice examinations.

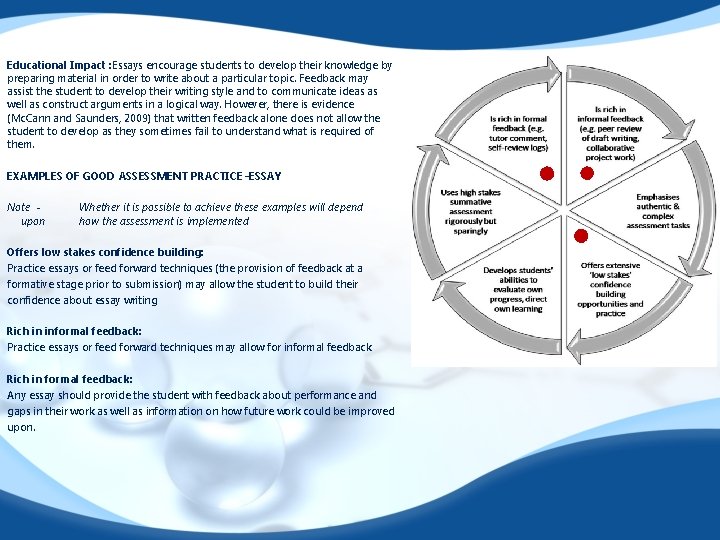

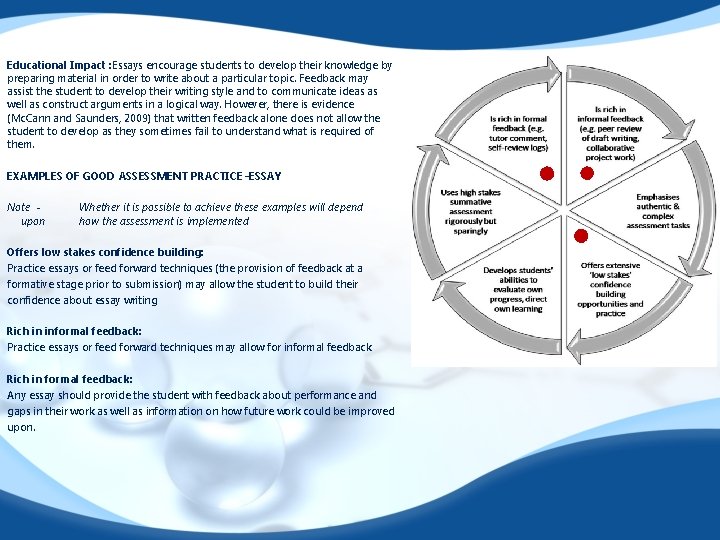

Educational Impact : Essays encourage students to develop their knowledge by preparing material in order to write about a particular topic. Feedback may assist the student to develop their writing style and to communicate ideas as well as construct arguments in a logical way. However, there is evidence (Mc. Cann and Saunders, 2009) that written feedback alone does not allow the student to develop as they sometimes fail to understand what is required of them. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –ESSAY Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Offers low stakes confidence building: Practice essays or feed forward techniques (the provision of feedback at a formative stage prior to submission) may allow the student to build their confidence about essay writing Rich in informal feedback: Practice essays or feed forward techniques may allow for informal feedback Rich in formal feedback: Any essay should provide the student with feedback about performance and gaps in their work as well as information on how future work could be improved upon.

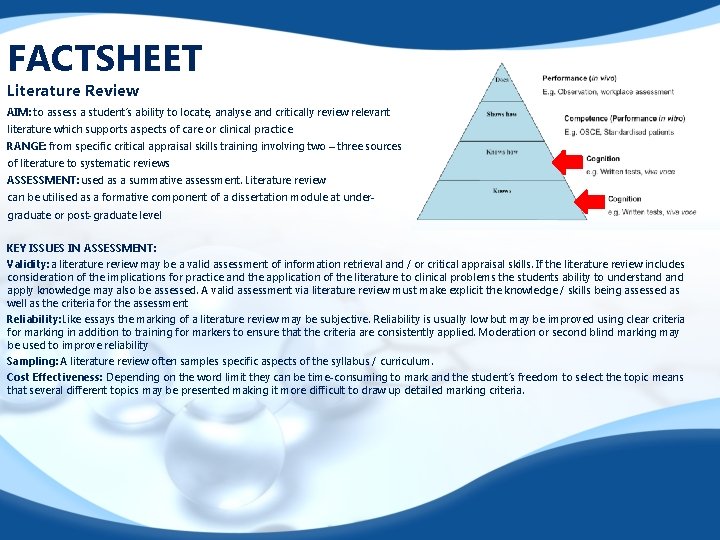

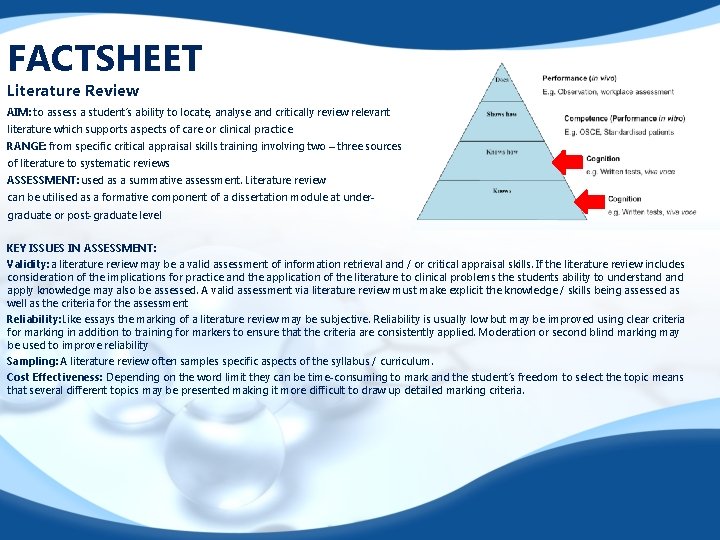

FACTSHEET Literature Review AIM: to assess a student’s ability to locate, analyse and critically review relevant literature which supports aspects of care or clinical practice RANGE: from specific critical appraisal skills training involving two – three sources of literature to systematic reviews ASSESSMENT: used as a summative assessment. Literature review can be utilised as a formative component of a dissertation module at undergraduate or post-graduate level KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: a literature review may be a valid assessment of information retrieval and / or critical appraisal skills. If the literature review includes consideration of the implications for practice and the application of the literature to clinical problems the students ability to understand apply knowledge may also be assessed. A valid assessment via literature review must make explicit the knowledge / skills being assessed as well as the criteria for the assessment Reliability: Like essays the marking of a literature review may be subjective. Reliability is usually low but may be improved using clear criteria for marking in addition to training for markers to ensure that the criteria are consistently applied. Moderation or second blind marking may be used to improve reliability Sampling: A literature review often samples specific aspects of the syllabus / curriculum. Cost Effectiveness: Depending on the word limit they can be time-consuming to mark and the student’s freedom to select the topic means that several different topics may be presented making it more difficult to draw up detailed marking criteria.

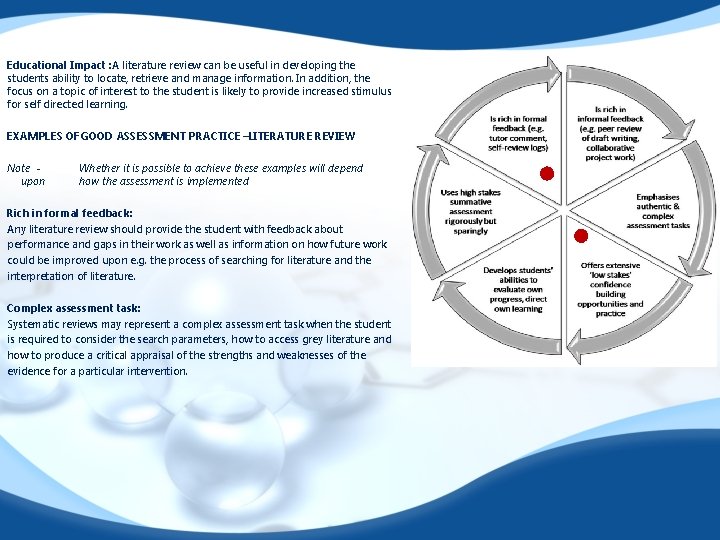

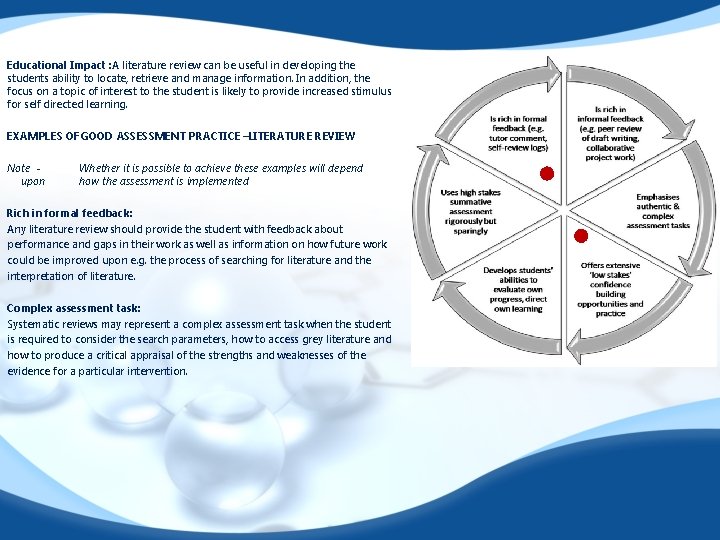

Educational Impact : A literature review can be useful in developing the students ability to locate, retrieve and manage information. In addition, the focus on a topic of interest to the student is likely to provide increased stimulus for self directed learning. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –LITERATURE REVIEW Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Rich in formal feedback: Any literature review should provide the student with feedback about performance and gaps in their work as well as information on how future work could be improved upon e. g. the process of searching for literature and the interpretation of literature. Complex assessment task: Systematic reviews may represent a complex assessment task when the student is required to consider the search parameters, how to access grey literature and how to produce a critical appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence for a particular intervention.

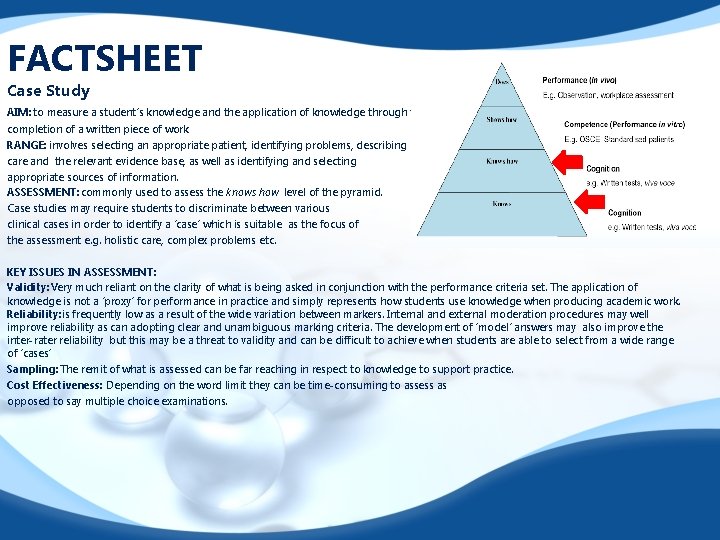

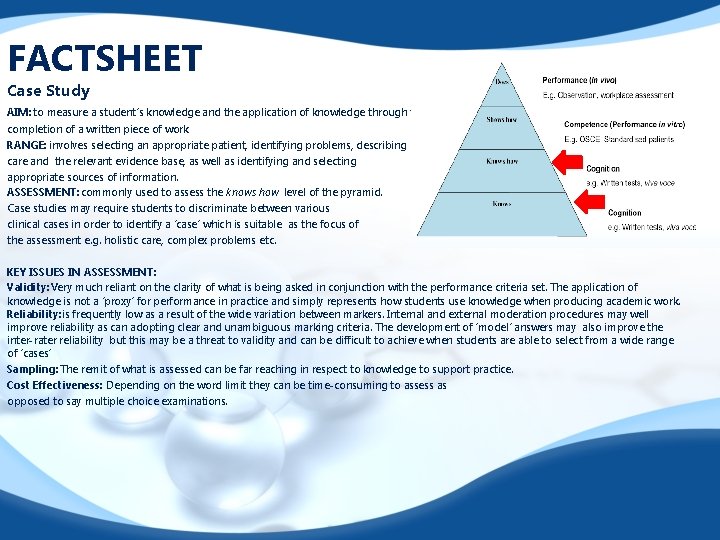

FACTSHEET Case Study AIM: to measure a student’s knowledge and the application of knowledge through the completion of a written piece of work RANGE: involves selecting an appropriate patient, identifying problems, describing care and the relevant evidence base, as well as identifying and selecting appropriate sources of information. ASSESSMENT: commonly used to assess the knows how level of the pyramid. Case studies may require students to discriminate between various clinical cases in order to identify a ‘case’ which is suitable as the focus of the assessment e. g. holistic care, complex problems etc. KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: Very much reliant on the clarity of what is being asked in conjunction with the performance criteria set. The application of knowledge is not a ‘proxy’ for performance in practice and simply represents how students use knowledge when producing academic work. Reliability: is frequently low as a result of the wide variation between markers. Internal and external moderation procedures may well improve reliability as can adopting clear and unambiguous marking criteria. The development of ‘model’ answers may also improve the inter-rater reliability but this may be a threat to validity and can be difficult to achieve when students are able to select from a wide range of ‘cases’ Sampling: The remit of what is assessed can be far reaching in respect to knowledge to support practice. Cost Effectiveness: Depending on the word limit they can be time-consuming to assess as opposed to say multiple choice examinations.

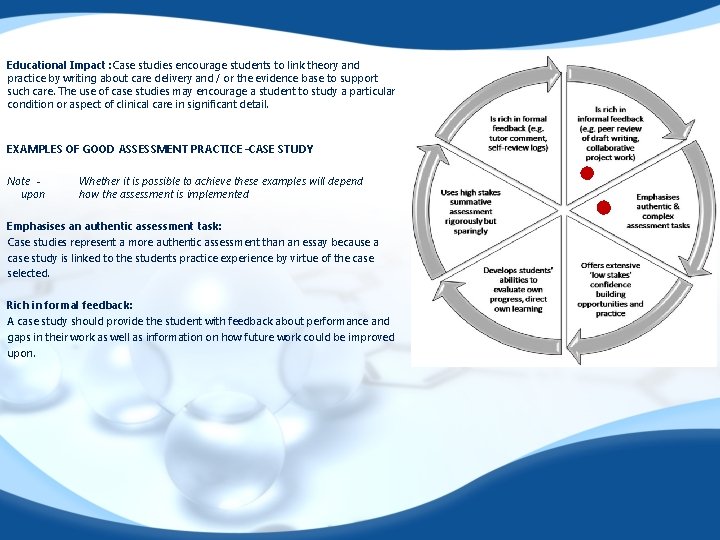

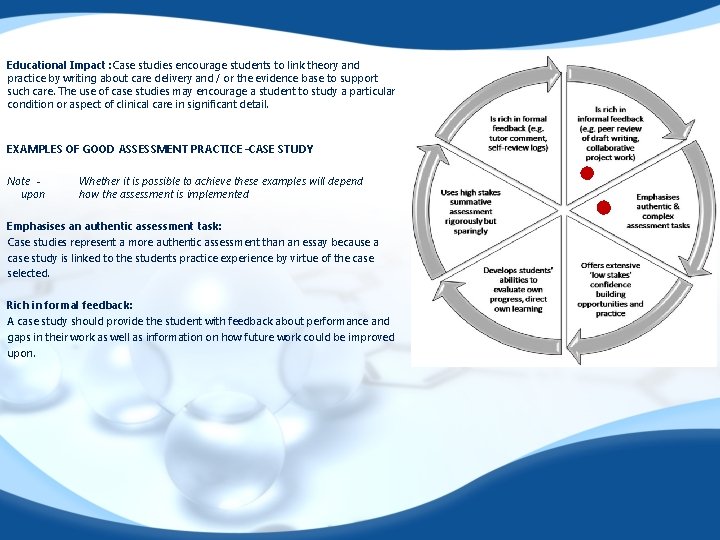

Educational Impact : Case studies encourage students to link theory and practice by writing about care delivery and / or the evidence base to support such care. The use of case studies may encourage a student to study a particular condition or aspect of clinical care in significant detail. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –CASE STUDY Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Emphasises an authentic assessment task: Case studies represent a more authentic assessment than an essay because a case study is linked to the students practice experience by virtue of the case selected. Rich in formal feedback: A case study should provide the student with feedback about performance and gaps in their work as well as information on how future work could be improved upon.

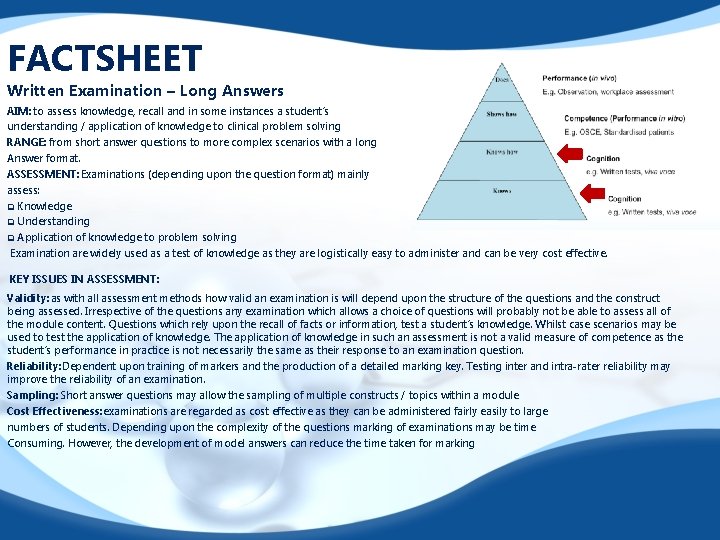

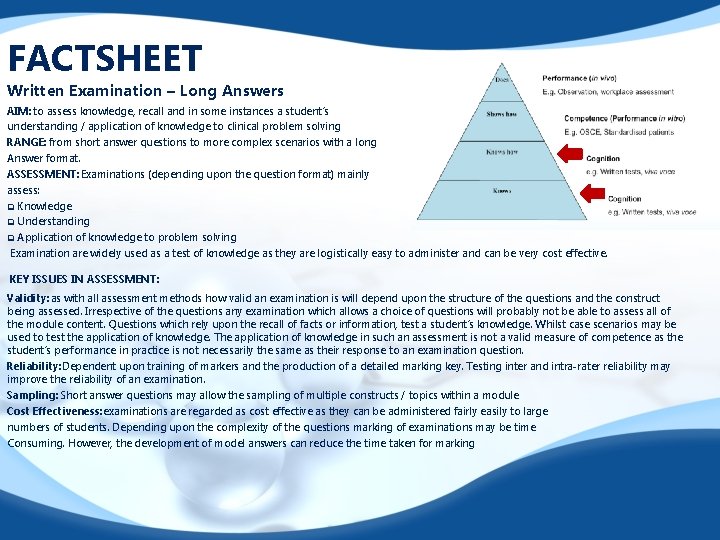

FACTSHEET Written Examination – Long Answers AIM: to assess knowledge, recall and in some instances a student’s understanding / application of knowledge to clinical problem solving RANGE: from short answer questions to more complex scenarios with a long Answer format. ASSESSMENT: Examinations (depending upon the question format) mainly assess: q Knowledge q Understanding q Application of knowledge to problem solving Examination are widely used as a test of knowledge as they are logistically easy to administer and can be very cost effective. KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: as with all assessment methods how valid an examination is will depend upon the structure of the questions and the construct being assessed. Irrespective of the questions any examination which allows a choice of questions will probably not be able to assess all of the module content. Questions which rely upon the recall of facts or information, test a student’s knowledge. Whilst case scenarios may be used to test the application of knowledge. The application of knowledge in such an assessment is not a valid measure of competence as the student’s performance in practice is not necessarily the same as their response to an examination question. Reliability: Dependent upon training of markers and the production of a detailed marking key. Testing inter and intra-rater reliability may improve the reliability of an examination. Sampling: Short answer questions may allow the sampling of multiple constructs / topics within a module Cost Effectiveness: examinations are regarded as cost effective as they can be administered fairly easily to large numbers of students. Depending upon the complexity of the questions marking of examinations may be time Consuming. However, the development of model answers can reduce the time taken for marking

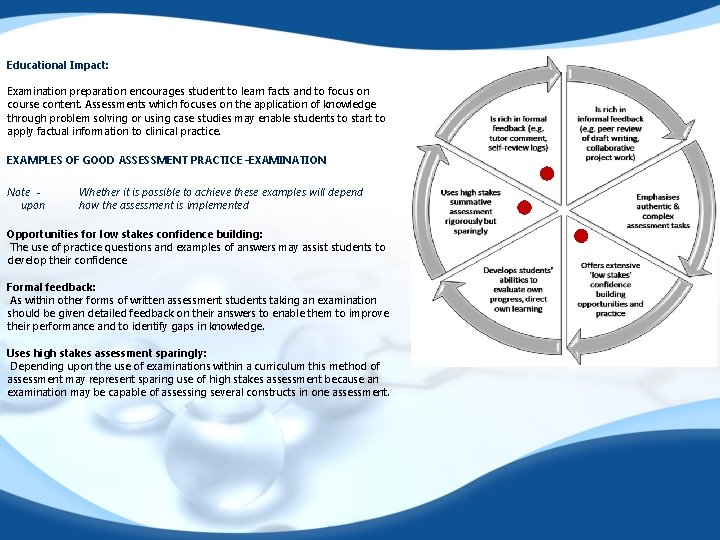

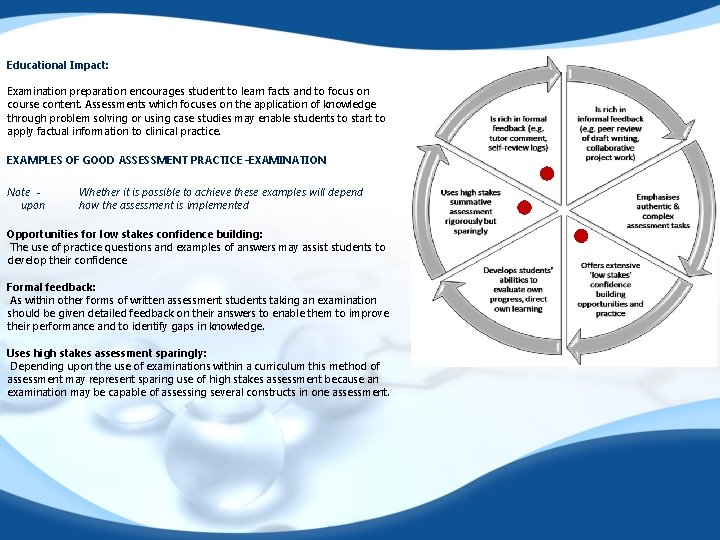

Educational Impact: Examination preparation encourages student to learn facts and to focus on course content. Assessments which focuses on the application of knowledge through problem solving or using case studies may enable students to start to apply factual information to clinical practice. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –EXAMINATION Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Opportunities for low stakes confidence building: The use of practice questions and examples of answers may assist students to develop their confidence Formal feedback: As within other forms of written assessment students taking an examination should be given detailed feedback on their answers to enable them to improve their performance and to identify gaps in knowledge. Uses high stakes assessment sparingly: Depending upon the use of examinations within a curriculum this method of assessment may represent sparing use of high stakes assessment because an examination may be capable of assessing several constructs in one assessment.

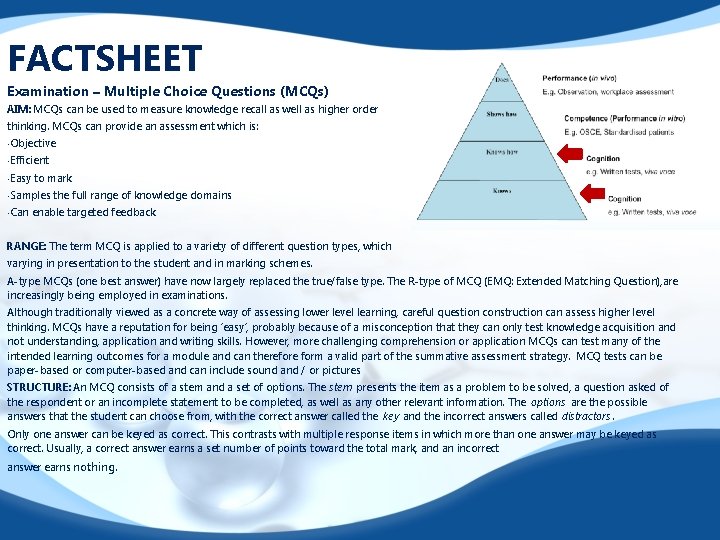

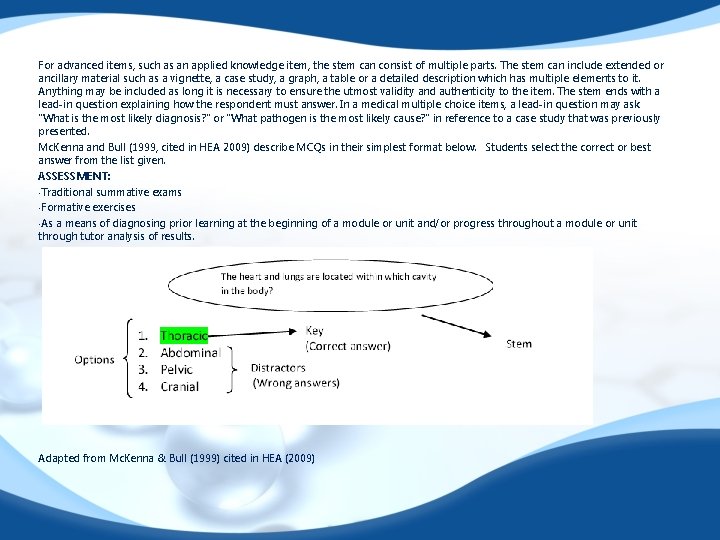

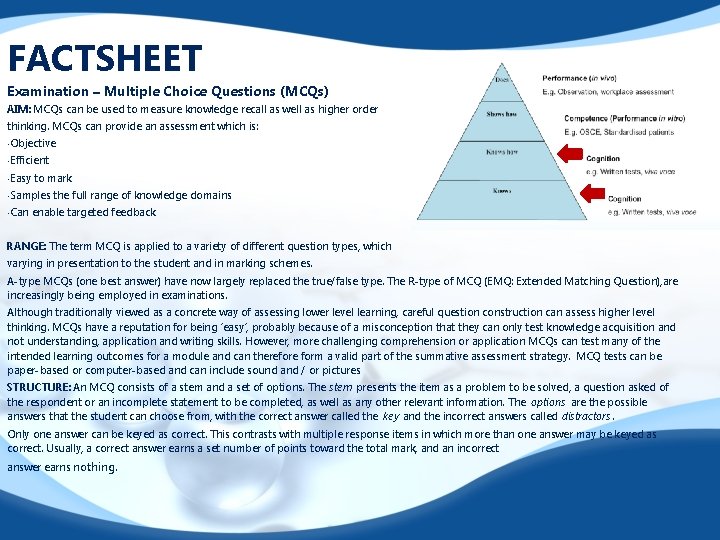

FACTSHEET Examination – Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) AIM: MCQs can be used to measure knowledge recall as well as higher order thinking. MCQs can provide an assessment which is: • Objective • Efficient • Easy to mark • Samples • Can the full range of knowledge domains enable targeted feedback RANGE: The term MCQ is applied to a variety of different question types, which varying in presentation to the student and in marking schemes. A-type MCQs (one best answer) have now largely replaced the true/false type. The R-type of MCQ (EMQ: Extended Matching Question), are increasingly being employed in examinations. Although traditionally viewed as a concrete way of assessing lower level learning, careful question construction can assess higher level thinking. MCQs have a reputation for being ‘easy’, probably because of a misconception that they can only test knowledge acquisition and not understanding, application and writing skills. However, more challenging comprehension or application MCQs can test many of the intended learning outcomes for a module and can therefore form a valid part of the summative assessment strategy. MCQ tests can be paper-based or computer-based and can include sound and / or pictures STRUCTURE: An MCQ consists of a stem and a set of options. The stem presents the item as a problem to be solved, a question asked of the respondent or an incomplete statement to be completed, as well as any other relevant information. The options are the possible answers that the student can choose from, with the correct answer called the key and the incorrect answers called distractors. Only one answer can be keyed as correct. This contrasts with multiple response items in which more than one answer may be keyed as correct. Usually, a correct answer earns a set number of points toward the total mark, and an incorrect answer earns nothing.

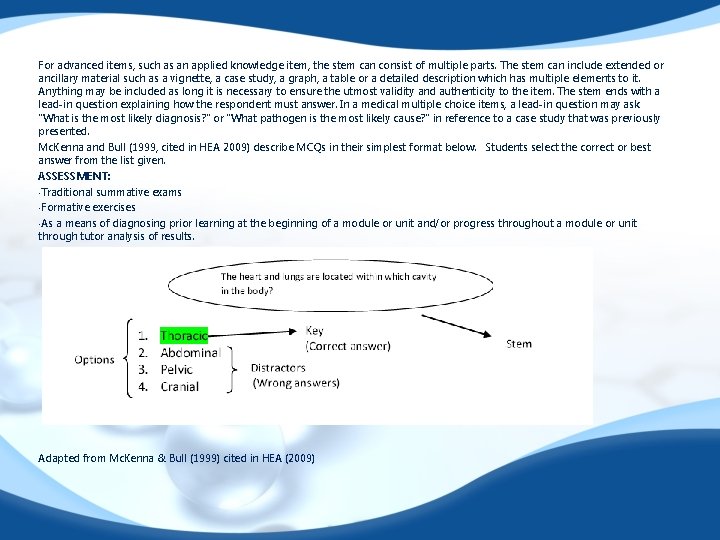

For advanced items, such as an applied knowledge item, the stem can consist of multiple parts. The stem can include extended or ancillary material such as a vignette, a case study, a graph, a table or a detailed description which has multiple elements to it. Anything may be included as long it is necessary to ensure the utmost validity and authenticity to the item. The stem ends with a lead-in question explaining how the respondent must answer. In a medical multiple choice items, a lead-in question may ask "What is the most likely diagnosis? " or "What pathogen is the most likely cause? " in reference to a case study that was previously presented. Mc. Kenna and Bull (1999, cited in HEA 2009) describe MCQs in their simplest format below. Students select the correct or best answer from the list given. ASSESSMENT: • Traditional summative exams • Formative exercises • As a means of diagnosing prior learning at the beginning of a module or unit and/or progress throughout a module or unit through tutor analysis of results. Adapted from Mc. Kenna & Bull (1999) cited in HEA (2009)

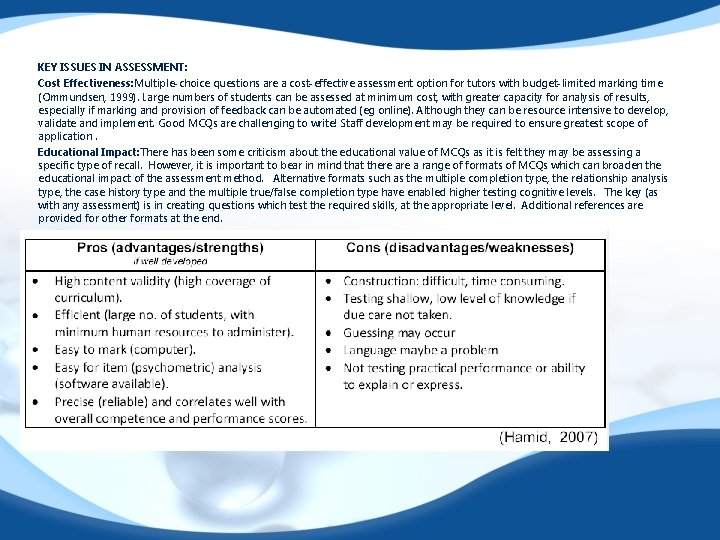

KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: The content validity of multiple choice tests depends upon systematic selection of items with regard to both content and level of learning. Although it is usual to try to select items that sample the range of content covered by the syllabus / curriculum, it is important to consider the level of the questions selected. It is important to consider what is being assessed and select questions and/or assessment strategies that reflect the full range of skills / knowledge expected. The issue of ‘guessing’ is frequently raised by detractors and it is possible to implement a formula to detect guessing. However, if the tests are robust (reliable), then the likelihood of students being able to guess extensively and pass are minimal. It is also possible to include ‘negative marking’ although this is considered poor practice now. Validity and reliability is enhanced by including a sufficient number of items (Medvarsity 2009). Reliability: Test reliability depends upon grading consistency and discrimination between students of differing performance levels. Well-designed MCQ tests are generally more reliable than essay tests because they sample material more broadly; discrimination between performance levels is easier to determine; scoring consistency is virtually guaranteed (Center for Teaching and Learning, 1990). On many MCQ assessments, reliability has been shown to improve with larger numbers of items on a test; with appropriate sampling across and within areas of the curriculum and care over case specificity, overall test reliability can be further increased (Downing, 2004).

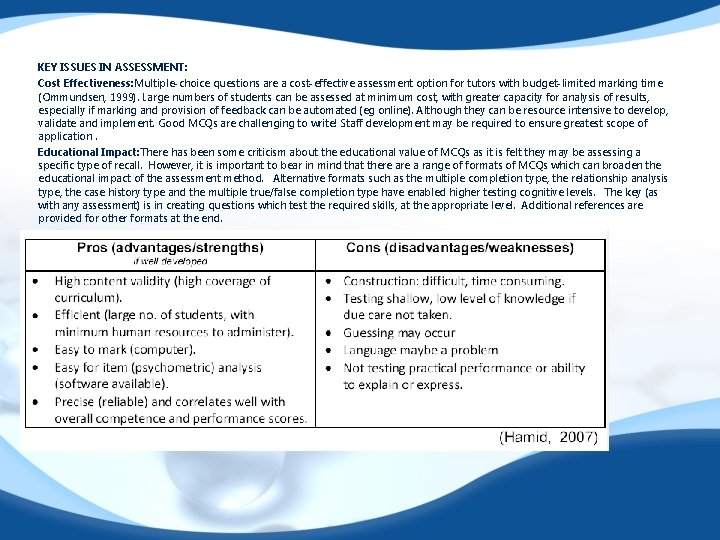

KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Cost Effectiveness: Multiple-choice questions are a cost-effective assessment option for tutors with budget-limited marking time (Ommundsen, 1999). Large numbers of students can be assessed at minimum cost, with greater capacity for analysis of results, especially if marking and provision of feedback can be automated (eg online). Although they can be resource intensive to develop, validate and implement. Good MCQs are challenging to write! Staff development may be required to ensure greatest scope of application. Educational Impact: There has been some criticism about the educational value of MCQs as it is felt they may be assessing a specific type of recall. However, it is important to bear in mind that there a range of formats of MCQs which can broaden the educational impact of the assessment method. Alternative formats such as the multiple completion type, the relationship analysis type, the case history type and the multiple true/false completion type have enabled higher testing cognitive levels. The key (as with any assessment) is in creating questions which test the required skills, at the appropriate level. Additional references are provided for other formats at the end.

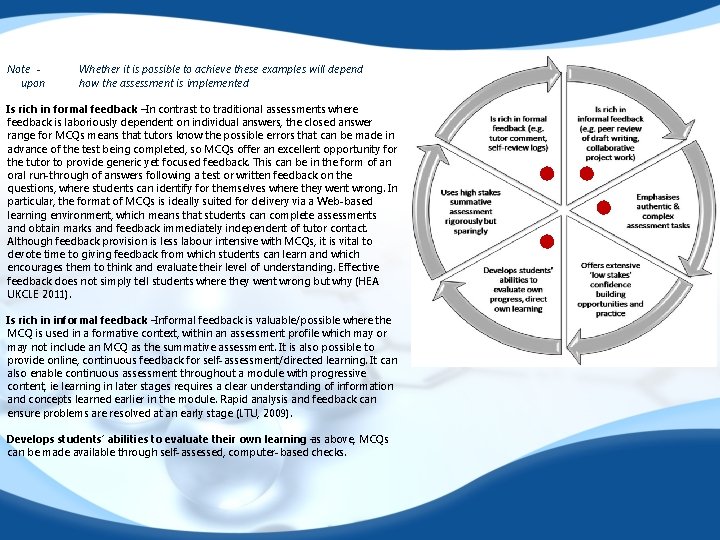

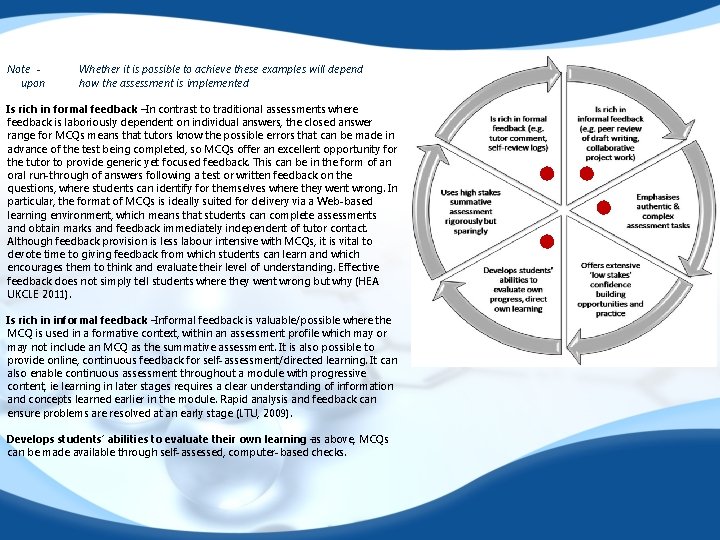

Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Is rich in formal feedback –In contrast to traditional assessments where feedback is laboriously dependent on individual answers, the closed answer range for MCQs means that tutors know the possible errors that can be made in advance of the test being completed, so MCQs offer an excellent opportunity for the tutor to provide generic yet focused feedback. This can be in the form of an oral run-through of answers following a test or written feedback on the questions, where students can identify for themselves where they went wrong. In particular, the format of MCQs is ideally suited for delivery via a Web-based learning environment, which means that students can complete assessments and obtain marks and feedback immediately independent of tutor contact. Although feedback provision is less labour intensive with MCQs, it is vital to devote time to giving feedback from which students can learn and which encourages them to think and evaluate their level of understanding. Effective feedback does not simply tell students where they went wrong but why (HEA UKCLE 2011). Is rich in informal feedback –Informal feedback is valuable/possible where the MCQ is used in a formative context, within an assessment profile which may or may not include an MCQ as the summative assessment. It is also possible to provide online, continuous feedback for self-assessment/directed learning. It can also enable continuous assessment throughout a module with progressive content, ie learning in later stages requires a clear understanding of information and concepts learned earlier in the module. Rapid analysis and feedback can ensure problems are resolved at an early stage (LTU, 2009). Develops students’ abilities to evaluate their own learning –as above, MCQs can be made available through self-assessed, computer-based checks.

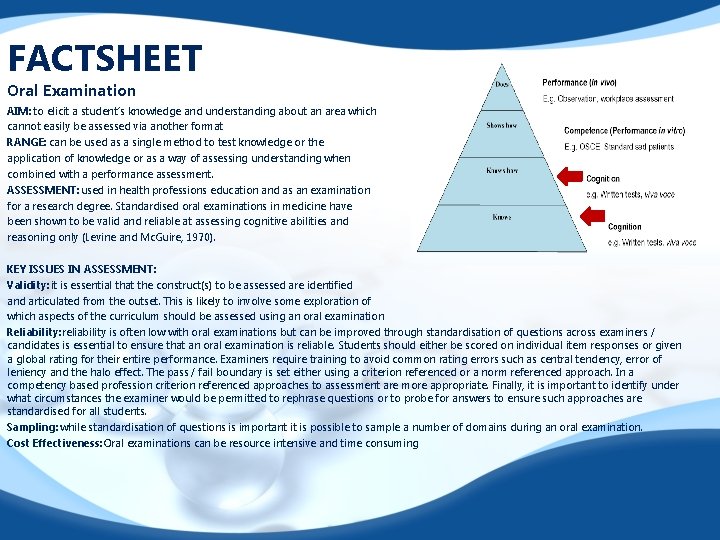

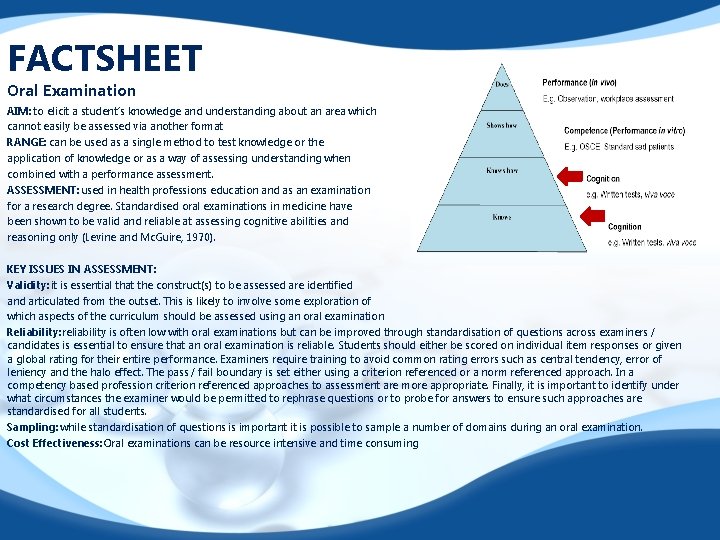

FACTSHEET Oral Examination AIM: to elicit a student’s knowledge and understanding about an area which cannot easily be assessed via another format RANGE: can be used as a single method to test knowledge or the application of knowledge or as a way of assessing understanding when combined with a performance assessment. ASSESSMENT: used in health professions education and as an examination for a research degree. Standardised oral examinations in medicine have been shown to be valid and reliable at assessing cognitive abilities and reasoning only (Levine and Mc. Guire, 1970). KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: it is essential that the construct(s) to be assessed are identified and articulated from the outset. This is likely to involve some exploration of which aspects of the curriculum should be assessed using an oral examination Reliability: reliability is often low with oral examinations but can be improved through standardisation of questions across examiners / candidates is essential to ensure that an oral examination is reliable. Students should either be scored on individual item responses or given a global rating for their entire performance. Examiners require training to avoid common rating errors such as central tendency, error of leniency and the halo effect. The pass / fail boundary is set either using a criterion referenced or a norm referenced approach. In a competency based profession criterion referenced approaches to assessment are more appropriate. Finally, it is important to identify under what circumstances the examiner would be permitted to rephrase questions or to probe for answers to ensure such approaches are standardised for all students. Sampling: while standardisation of questions is important it is possible to sample a number of domains during an oral examination. Cost Effectiveness: Oral examinations can be resource intensive and time consuming

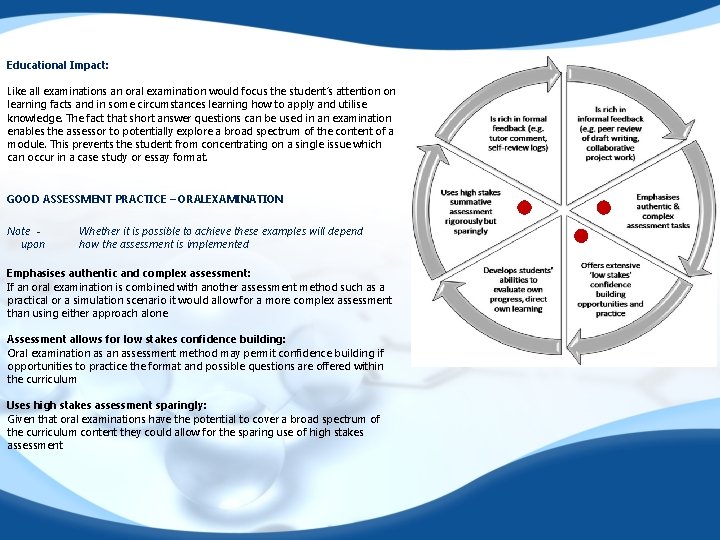

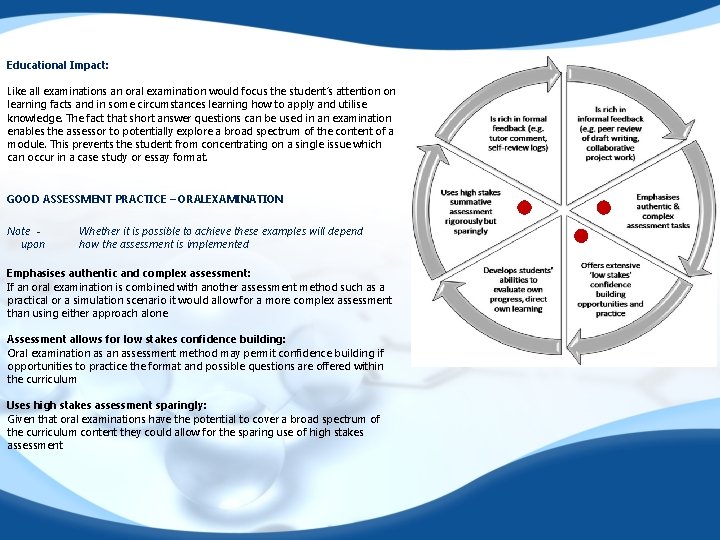

Educational Impact: Like all examinations an oral examination would focus the student’s attention on learning facts and in some circumstances learning how to apply and utilise knowledge. The fact that short answer questions can be used in an examination enables the assessor to potentially explore a broad spectrum of the content of a module. This prevents the student from concentrating on a single issue which can occur in a case study or essay format. GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE – ORALEXAMINATION Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Emphasises authentic and complex assessment: If an oral examination is combined with another assessment method such as a practical or a simulation scenario it would allow for a more complex assessment than using either approach alone Assessment allows for low stakes confidence building: Oral examination as an assessment method may permit confidence building if opportunities to practice the format and possible questions are offered within the curriculum Uses high stakes assessment sparingly: Given that oral examinations have the potential to cover a broad spectrum of the curriculum content they could allow for the sparing use of high stakes assessment

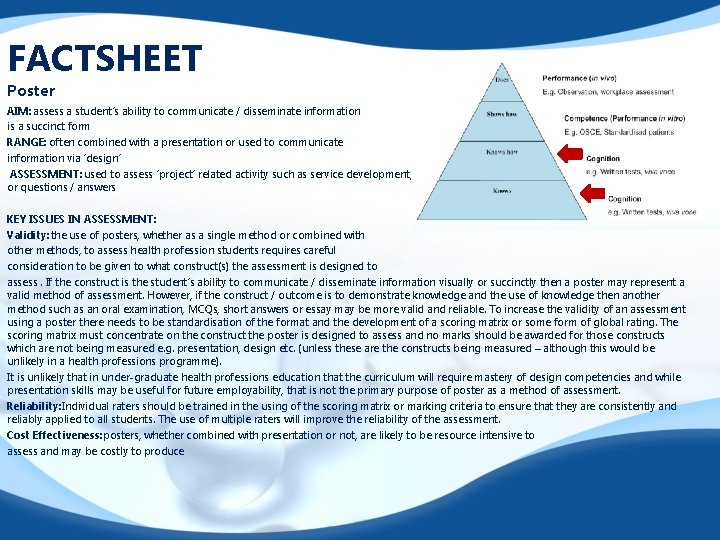

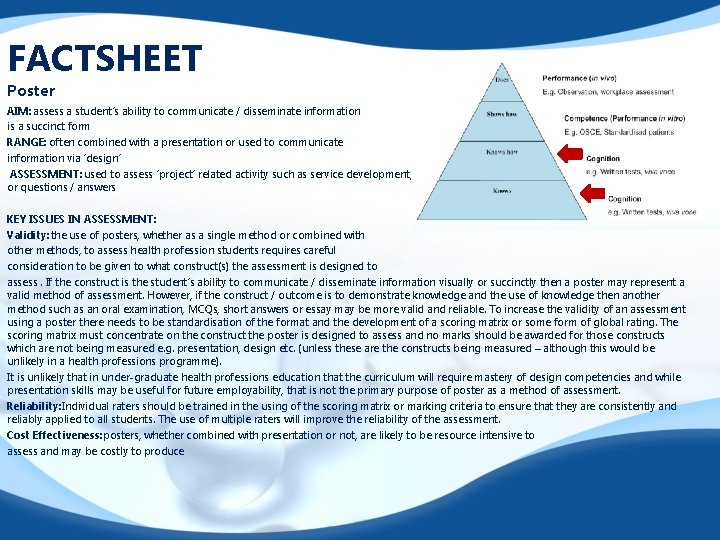

FACTSHEET Poster AIM: assess a student’s ability to communicate / disseminate information is a succinct form RANGE: often combined with a presentation or used to communicate information via ‘design’ ASSESSMENT: used to assess ‘project’ related activity such as service development, audit or research. Usually combined with a presentation or questions / answers KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: the use of posters, whether as a single method or combined with other methods, to assess health profession students requires careful consideration to be given to what construct(s) the assessment is designed to assess. If the construct is the student’s ability to communicate / disseminate information visually or succinctly then a poster may represent a valid method of assessment. However, if the construct / outcome is to demonstrate knowledge and the use of knowledge then another method such as an oral examination, MCQs, short answers or essay may be more valid and reliable. To increase the validity of an assessment using a poster there needs to be standardisation of the format and the development of a scoring matrix or some form of global rating. The scoring matrix must concentrate on the construct the poster is designed to assess and no marks should be awarded for those constructs which are not being measured e. g. presentation, design etc. (unless these are the constructs being measured – although this would be unlikely in a health professions programme). It is unlikely that in under-graduate health professions education that the curriculum will require mastery of design competencies and while presentation skills may be useful for future employability, that is not the primary purpose of poster as a method of assessment. Reliability: Individual raters should be trained in the using of the scoring matrix or marking criteria to ensure that they are consistently and reliably applied to all students. The use of multiple raters will improve the reliability of the assessment. Cost Effectiveness: posters, whether combined with presentation or not, are likely to be resource intensive to assess and may be costly to produce

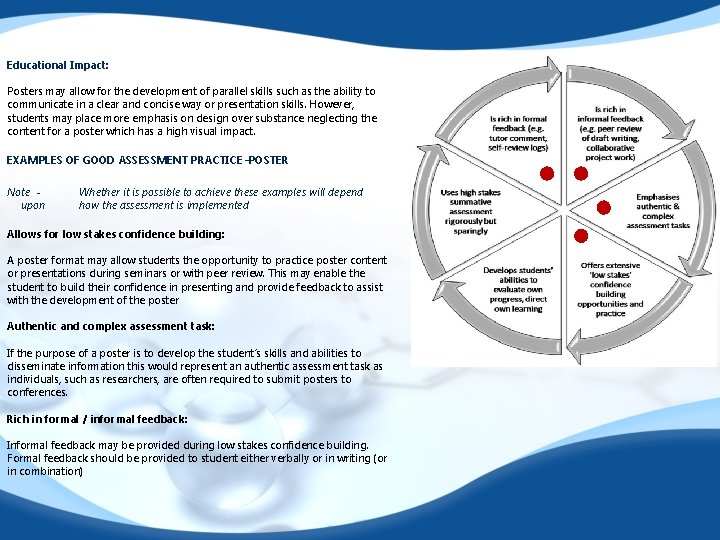

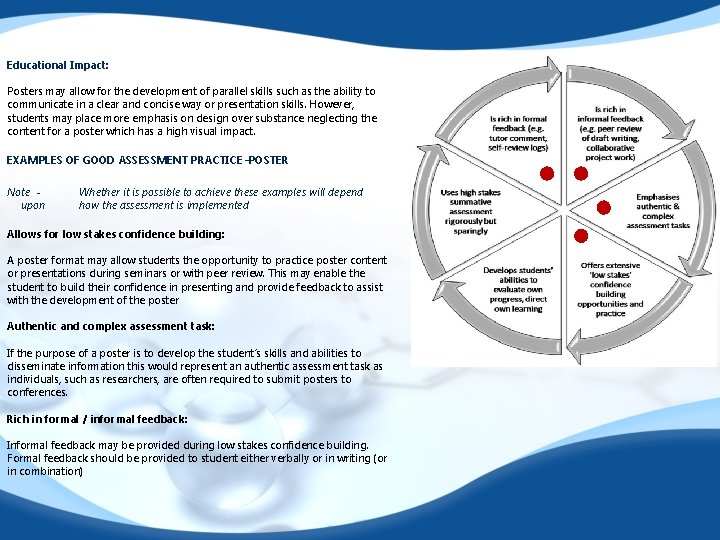

Educational Impact: Posters may allow for the development of parallel skills such as the ability to communicate in a clear and concise way or presentation skills. However, students may place more emphasis on design over substance neglecting the content for a poster which has a high visual impact. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –POSTER Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Allows for low stakes confidence building: A poster format may allow students the opportunity to practice poster content or presentations during seminars or with peer review. This may enable the student to build their confidence in presenting and provide feedback to assist with the development of the poster Authentic and complex assessment task: If the purpose of a poster is to develop the student’s skills and abilities to disseminate information this would represent an authentic assessment task as individuals, such as researchers, are often required to submit posters to conferences. Rich in formal / informal feedback: Informal feedback may be provided during low stakes confidence building. Formal feedback should be provided to student either verbally or in writing (or in combination)

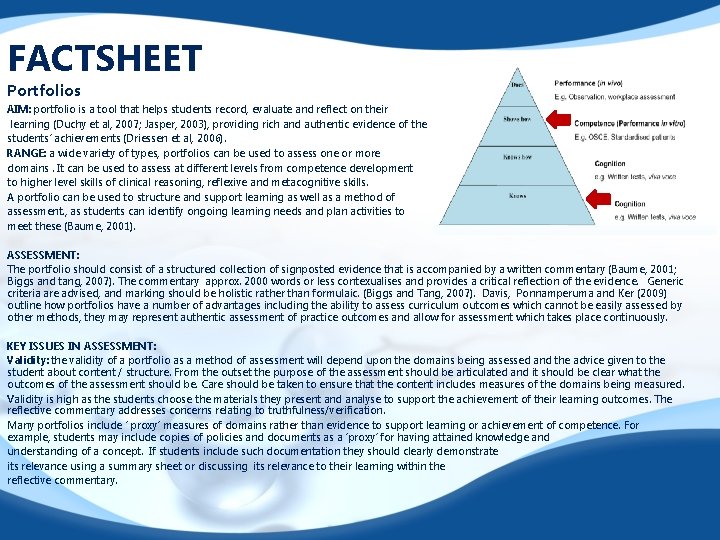

FACTSHEET Portfolios AIM: portfolio is a tool that helps students record, evaluate and reflect on their learning (Duchy et al, 2007; Jasper, 2003), providing rich and authentic evidence of the students’ achievements (Driessen et al, 2006). RANGE: a wide variety of types, portfolios can be used to assess one or more domains. It can be used to assess at different levels from competence development to higher level skills of clinical reasoning, reflexive and metacognitive skills. A portfolio can be used to structure and support learning as well as a method of assessment. , as students can identify ongoing learning needs and plan activities to meet these (Baume, 2001). ASSESSMENT: The portfolio should consist of a structured collection of signposted evidence that is accompanied by a written commentary (Baume, 2001; Biggs and tang, 2007). The commentary approx. 2000 words or less contexualises and provides a critical reflection of the evidence. Generic criteria are advised, and marking should be holistic rather than formulaic. (Biggs and Tang, 2007). Davis, Ponnamperuma and Ker (2009) outline how portfolios have a number of advantages including the ability to assess curriculum outcomes which cannot be easily assessed by other methods, they may represent authentic assessment of practice outcomes and allow for assessment which takes place continuously. KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: the validity of a portfolio as a method of assessment will depend upon the domains being assessed and the advice given to the student about content / structure. From the outset the purpose of the assessment should be articulated and it should be clear what the outcomes of the assessment should be. Care should be taken to ensure that the content includes measures of the domains being measured. Validity is high as the students choose the materials they present and analyse to support the achievement of their learning outcomes. The reflective commentary addresses concerns relating to truthfulness/verification. Many portfolios include ‘ proxy’ measures of domains rather than evidence to support learning or achievement of competence. For example, students may include copies of policies and documents as a ‘proxy’ for having attained knowledge and understanding of a concept. If students include such documentation they should clearly demonstrate its relevance using a summary sheet or discussing its relevance to their learning within the reflective commentary.

Reliability: Detailed guidelines need to be provided for students but they should not be prescriptive (Driessen et al, 2007), as there needs to be enough flexibility to allow students to individualise their portfolios. Knight and Yorke (2003) suggest the use of developmental work for staff new to this area of assessment, this will help address issues around inter rater reliability as will double marking. Clear but generic criteria are advised, and marking should be holistic rather than formulaic. Rating scales may be used to improve reliability however Biggs and Tang (2007). suggest the danger of marking individual items is that you loose the big picture. Portfolio assessment is complex, the use of generic criteria are advised, and marking should be holistic rather than formulaic (Biggs and Tang, 2007; Driessen et al, 2007). Sampling: assessment of a portfolio requires an evaluation of the evidence presented against the achievement of predetermined criteria. Cost Effectiveness: assessment of a portfolio can be time consuming particularly where multiple domains / outcomes are assessed, however it can be very interesting as each portfolio will be individualised. Students will need help and guidance in the preparation of their portfolios (Biggs and Tang, 2007). Educational Impact: the testing of skills leads to student practice of these skills which are normally clearly linked to clinical performance, i. e. the ability to apply (selected) principles of applied healthcare profession practice as an indicator for safe and effective patient care

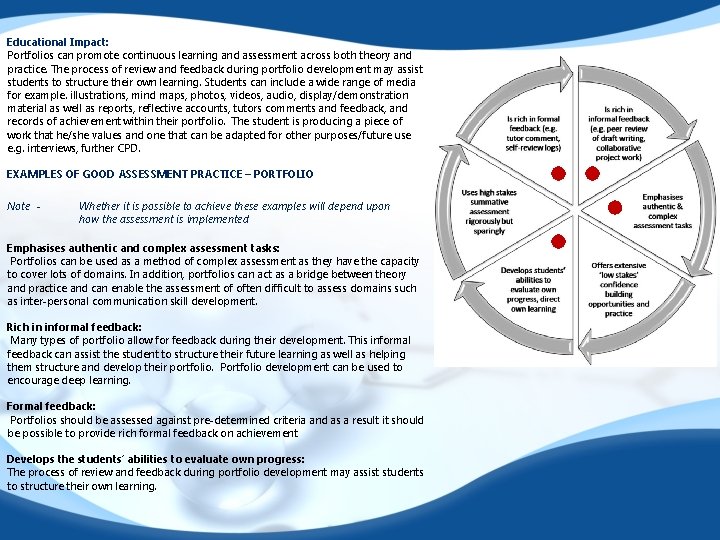

Educational Impact: Portfolios can promote continuous learning and assessment across both theory and practice. The process of review and feedback during portfolio development may assist students to structure their own learning. Students can include a wide range of media for example. illustrations, mind maps, photos, videos, audio, display/demonstration material as well as reports, reflective accounts, tutors comments and feedback, and records of achievement within their portfolio. The student is producing a piece of work that he/she values and one that can be adapted for other purposes/future use e. g. interviews, further CPD. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE – PORTFOLIO Note - Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend upon how the assessment is implemented Emphasises authentic and complex assessment tasks: Portfolios can be used as a method of complex assessment as they have the capacity to cover lots of domains. In addition, portfolios can act as a bridge between theory and practice and can enable the assessment of often difficult to assess domains such as inter-personal communication skill development. Rich in informal feedback: Many types of portfolio allow for feedback during their development. This informal feedback can assist the student to structure their future learning as well as helping them structure and develop their portfolio. Portfolio development can be used to encourage deep learning. Formal feedback: Portfolios should be assessed against pre-determined criteria and as a result it should be possible to provide rich formal feedback on achievement Develops the students’ abilities to evaluate own progress: The process of review and feedback during portfolio development may assist students to structure their own learning.

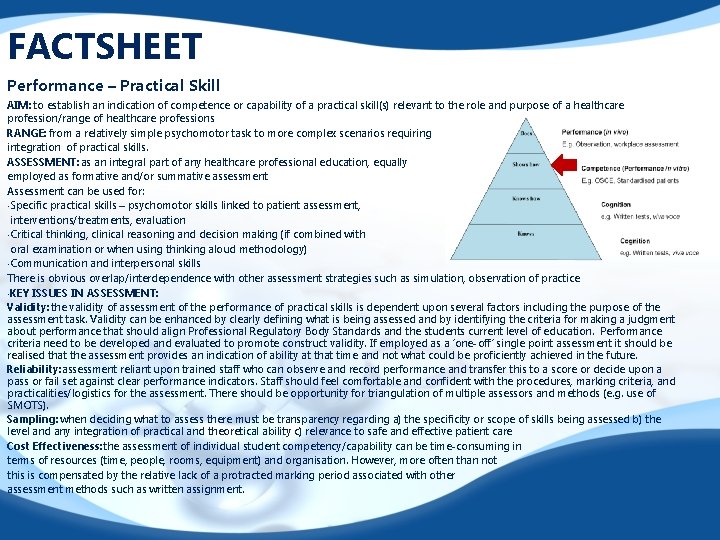

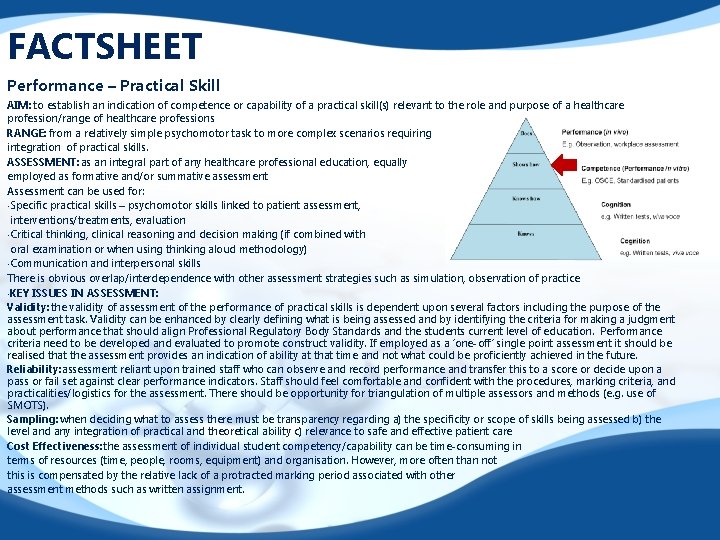

FACTSHEET Performance – Practical Skill AIM: to establish an indication of competence or capability of a practical skill(s) relevant to the role and purpose of a healthcare profession/range of healthcare professions RANGE: from a relatively simple psychomotor task to more complex scenarios requiring integration of practical skills. ASSESSMENT: as an integral part of any healthcare professional education, equally employed as formative and/or summative assessment Assessment can be used for: • Specific practical skills – psychomotor skills linked to patient assessment, interventions/treatments, evaluation • Critical thinking, clinical reasoning and decision making (if combined with oral examination or when using thinking aloud methodology) • Communication and interpersonal skills There is obvious overlap/interdependence with other assessment strategies such as simulation, observation of practice • KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: the validity of assessment of the performance of practical skills is dependent upon several factors including the purpose of the assessment task. Validity can be enhanced by clearly defining what is being assessed and by identifying the criteria for making a judgment about performance that should align Professional Regulatory Body Standards and the students current level of education. Performance criteria need to be developed and evaluated to promote construct validity. If employed as a ‘one-off’ single point assessment it should be realised that the assessment provides an indication of ability at that time and not what could be proficiently achieved in the future. Reliability: assessment reliant upon trained staff who can observe and record performance and transfer this to a score or decide upon a pass or fail set against clear performance indicators. Staff should feel comfortable and confident with the procedures, marking criteria, and practicalities/logistics for the assessment. There should be opportunity for triangulation of multiple assessors and methods (e. g. use of SMOTS). Sampling: when deciding what to assess there must be transparency regarding a) the specificity or scope of skills being assessed b) the level and any integration of practical and theoretical ability c) relevance to safe and effective patient care Cost Effectiveness: the assessment of individual student competency/capability can be time-consuming in terms of resources (time, people, rooms, equipment) and organisation. However, more often than not this is compensated by the relative lack of a protracted marking period associated with other assessment methods such as written assignment.

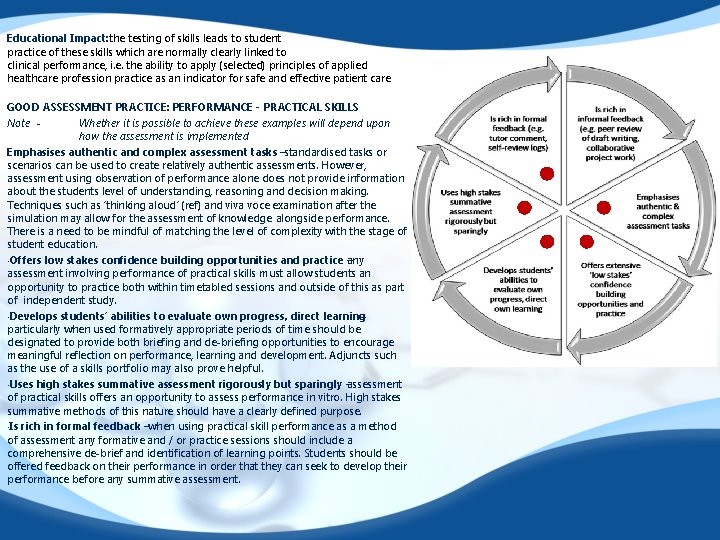

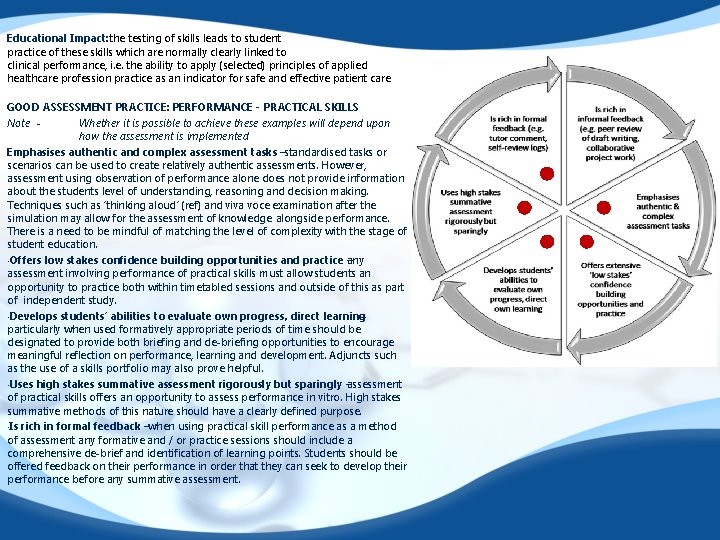

Educational Impact: the testing of skills leads to student practice of these skills which are normally clearly linked to clinical performance, i. e. the ability to apply (selected) principles of applied healthcare profession practice as an indicator for safe and effective patient care GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE: PERFORMANCE - PRACTICAL SKILLS Note Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend upon how the assessment is implemented Emphasises authentic and complex assessment tasks –standardised tasks or scenarios can be used to create relatively authentic assessments. However, assessment using observation of performance alone does not provide information about the students level of understanding, reasoning and decision making. Techniques such as ‘thinking aloud’ (ref) and viva voce examination after the simulation may allow for the assessment of knowledge alongside performance. There is a need to be mindful of matching the level of complexity with the stage of student education. • Offers low stakes confidence building opportunities and practice any – assessment involving performance of practical skills must allow students an opportunity to practice both within timetabled sessions and outside of this as part of independent study. • Develops students’ abilities to evaluate own progress, direct learning – particularly when used formatively appropriate periods of time should be designated to provide both briefing and de-briefing opportunities to encourage meaningful reflection on performance, learning and development. Adjuncts such as the use of a skills portfolio may also prove helpful. • Uses high stakes summative assessment rigorously but sparingly – assessment of practical skills offers an opportunity to assess performance in vitro. High stakes summative methods of this nature should have a clearly defined purpose. • Is rich in formal feedback –when using practical skill performance as a method of assessment any formative and / or practice sessions should include a comprehensive de-brief and identification of learning points. Students should be offered feedback on their performance in order that they can seek to develop their performance before any summative assessment.

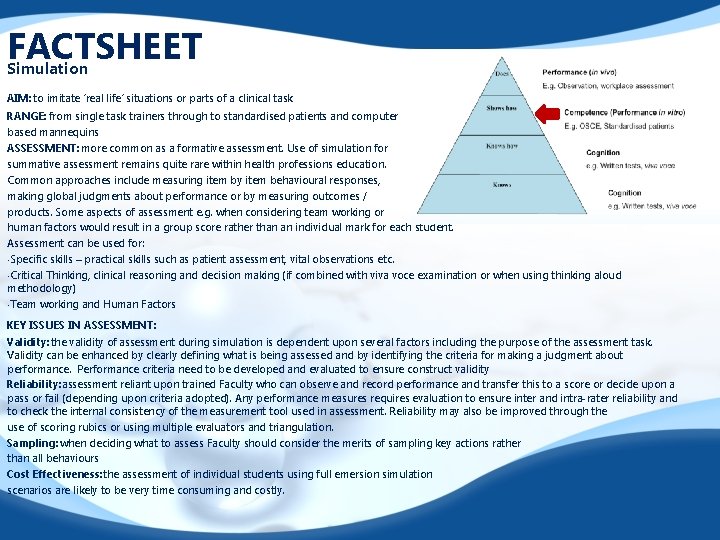

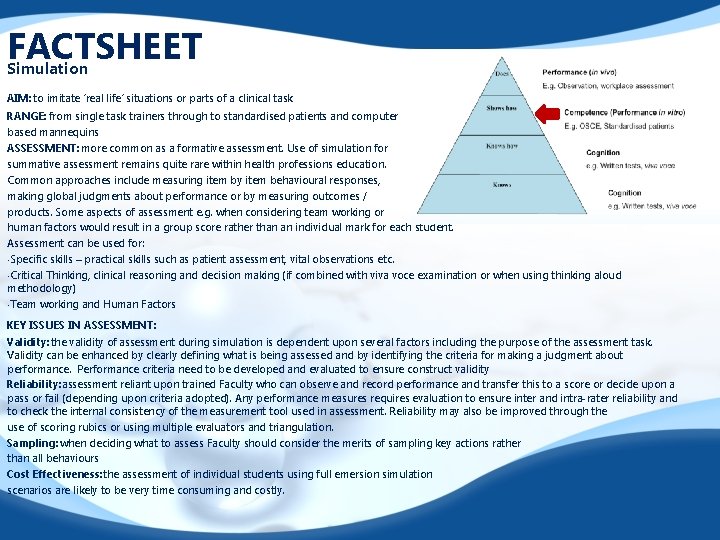

FACTSHEET Simulation AIM: to imitate ‘real life’ situations or parts of a clinical task RANGE: from single task trainers through to standardised patients and computer based mannequins ASSESSMENT: more common as a formative assessment. Use of simulation for summative assessment remains quite rare within health professions education. Common approaches include measuring item by item behavioural responses, making global judgments about performance or by measuring outcomes / products. Some aspects of assessment e. g. when considering team working or human factors would result in a group score rather than an individual mark for each student. Assessment can be used for: • Specific skills – practical skills such as patient assessment, vital observations etc. • Critical Thinking, clinical reasoning and decision making (if combined with viva voce examination or when using thinking aloud methodology) • Team working and Human Factors KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: the validity of assessment during simulation is dependent upon several factors including the purpose of the assessment task. Validity can be enhanced by clearly defining what is being assessed and by identifying the criteria for making a judgment about performance. Performance criteria need to be developed and evaluated to ensure construct validity Reliability: assessment reliant upon trained Faculty who can observe and record performance and transfer this to a score or decide upon a pass or fail (depending upon criteria adopted). Any performance measures requires evaluation to ensure inter and intra-rater reliability and to check the internal consistency of the measurement tool used in assessment. Reliability may also be improved through the use of scoring rubics or using multiple evaluators and triangulation. Sampling: when deciding what to assess Faculty should consider the merits of sampling key actions rather than all behaviours Cost Effectiveness: the assessment of individual students using full emersion simulation scenarios are likely to be very time consuming and costly.

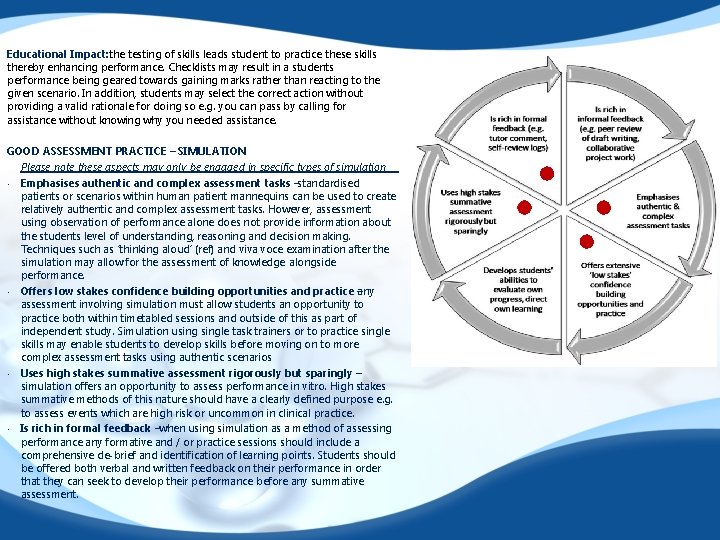

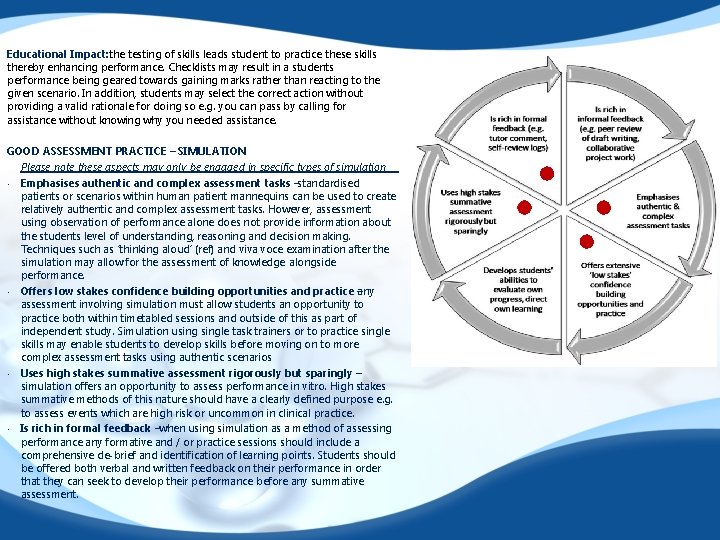

Educational Impact: the testing of skills leads student to practice these skills thereby enhancing performance. Checklists may result in a students performance being geared towards gaining marks rather than reacting to the given scenario. In addition, students may select the correct action without providing a valid rationale for doing so e. g. you can pass by calling for assistance without knowing why you needed assistance. GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE – SIMULATION Please note these aspects may only be engaged in specific types of simulation • Emphasises authentic and complex assessment tasks –standardised patients or scenarios within human patient mannequins can be used to create relatively authentic and complex assessment tasks. However, assessment using observation of performance alone does not provide information about the students level of understanding, reasoning and decision making. Techniques such as ‘thinking aloud’ (ref) and viva voce examination after the simulation may allow for the assessment of knowledge alongside performance. • Offers low stakes confidence building opportunities and practice any – assessment involving simulation must allow students an opportunity to practice both within timetabled sessions and outside of this as part of independent study. Simulation usingle task trainers or to practice single skills may enable students to develop skills before moving on to more complex assessment tasks using authentic scenarios • Uses high stakes summative assessment rigorously but sparingly – simulation offers an opportunity to assess performance in vitro. High stakes summative methods of this nature should have a clearly defined purpose e. g. to assess events which are high risk or uncommon in clinical practice. • Is rich in formal feedback –when using simulation as a method of assessing performance any formative and / or practice sessions should include a comprehensive de-brief and identification of learning points. Students should be offered both verbal and written feedback on their performance in order that they can seek to develop their performance before any summative assessment.

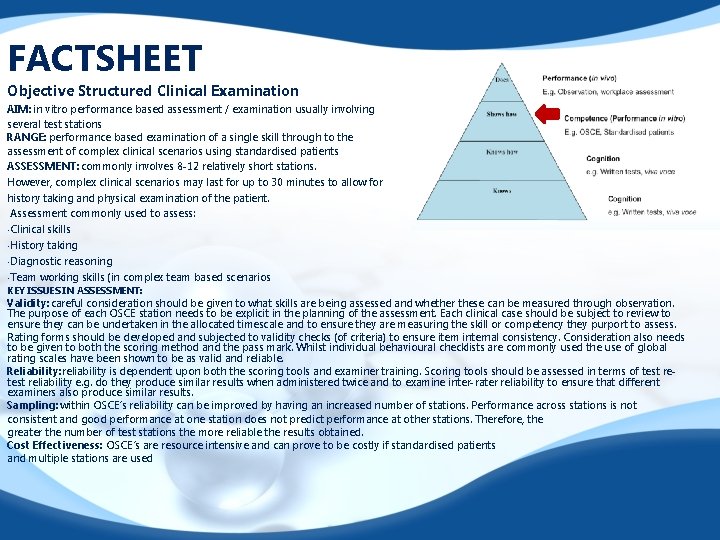

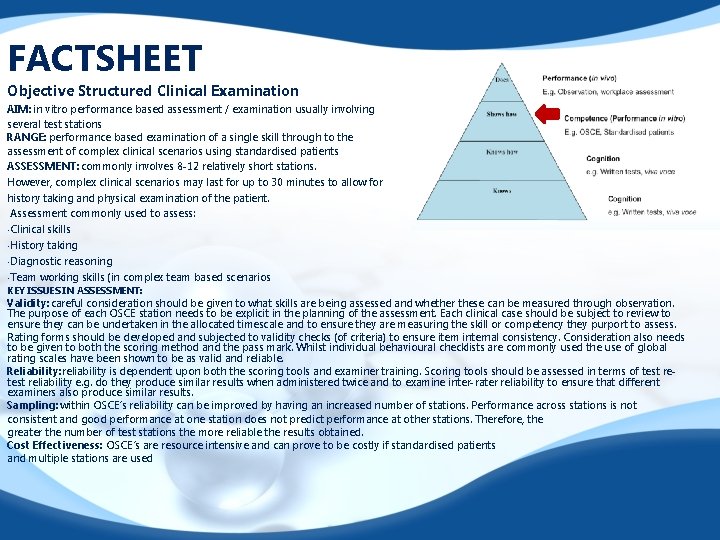

FACTSHEET Objective Structured Clinical Examination AIM: in vitro performance based assessment / examination usually involving several test stations RANGE: performance based examination of a single skill through to the assessment of complex clinical scenarios using standardised patients ASSESSMENT: commonly involves 8 -12 relatively short stations. However, complex clinical scenarios may last for up to 30 minutes to allow for history taking and physical examination of the patient. Assessment commonly used to assess: • Clinical skills • History taking • Diagnostic reasoning • Team working skills (in complex team based scenarios KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: careful consideration should be given to what skills are being assessed and whether these can be measured through observation. The purpose of each OSCE station needs to be explicit in the planning of the assessment. Each clinical case should be subject to review to ensure they can be undertaken in the allocated timescale and to ensure they are measuring the skill or competency they purport to assess. Rating forms should be developed and subjected to validity checks (of criteria) to ensure item internal consistency. Consideration also needs to be given to both the scoring method and the pass mark. Whilst individual behavioural checklists are commonly used the use of global rating scales have been shown to be as valid and reliable. Reliability: reliability is dependent upon both the scoring tools and examiner training. Scoring tools should be assessed in terms of test reliability e. g. do they produce similar results when administered twice and to examine inter-rater reliability to ensure that different examiners also produce similar results. Sampling: within OSCE’s reliability can be improved by having an increased number of stations. Performance across stations is not consistent and good performance at one station does not predict performance at other stations. Therefore, the greater the number of test stations the more reliable the results obtained. Cost Effectiveness: OSCE’s are resource intensive and can prove to be costly if standardised patients and multiple stations are used

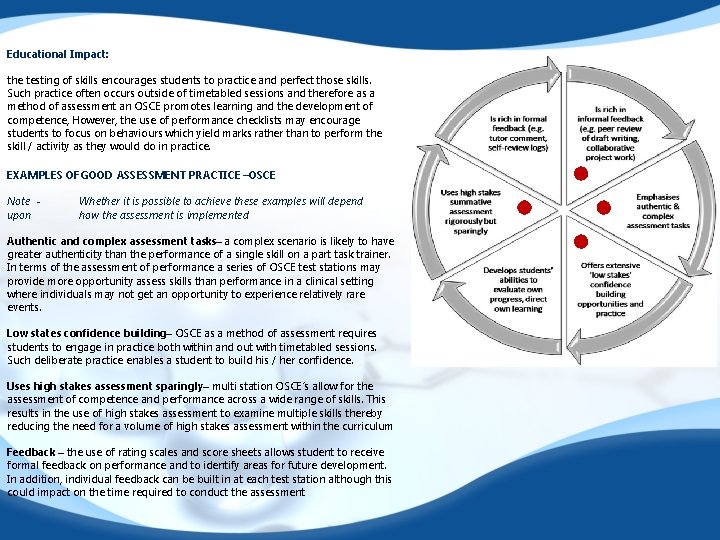

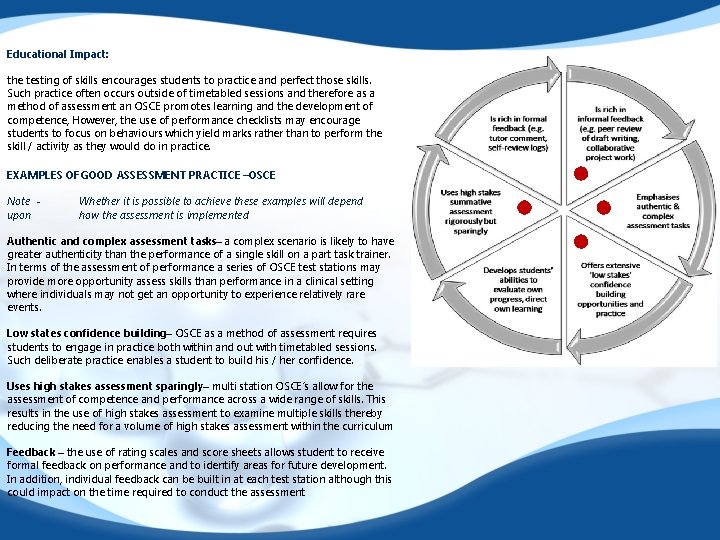

Educational Impact: the testing of skills encourages students to practice and perfect those skills. Such practice often occurs outside of timetabled sessions and therefore as a method of assessment an OSCE promotes learning and the development of competence, However, the use of performance checklists may encourage students to focus on behaviours which yield marks rather than to perform the skill / activity as they would do in practice. EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE –OSCE Note upon Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend how the assessment is implemented Authentic and complex assessment tasks– a complex scenario is likely to have greater authenticity than the performance of a single skill on a part task trainer. In terms of the assessment of performance a series of OSCE test stations may provide more opportunity assess skills than performance in a clinical setting where individuals may not get an opportunity to experience relatively rare events. Low states confidence building– OSCE as a method of assessment requires students to engage in practice both within and out with timetabled sessions. Such deliberate practice enables a student to build his / her confidence. Uses high stakes assessment sparingly– multi station OSCE’s allow for the assessment of competence and performance across a wide range of skills. This results in the use of high stakes assessment to examine multiple skills thereby reducing the need for a volume of high stakes assessment within the curriculum Feedback – the use of rating scales and score sheets allows student to receive formal feedback on performance and to identify areas for future development. In addition, individual feedback can be built in at each test station although this could impact on the time required to conduct the assessment

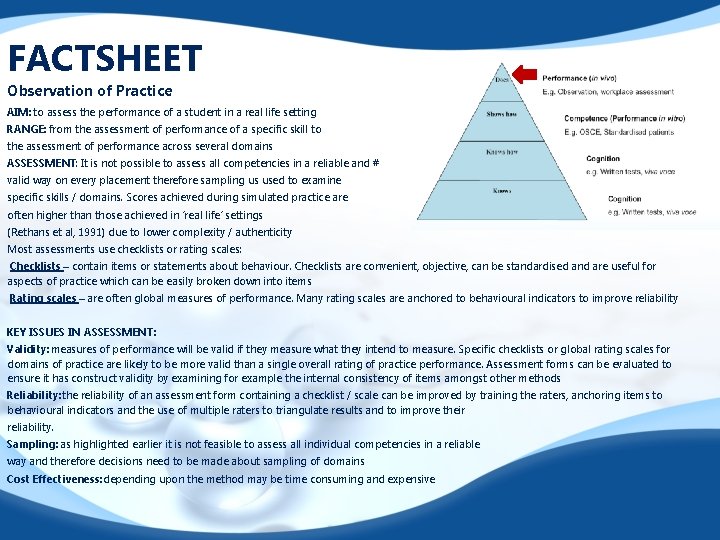

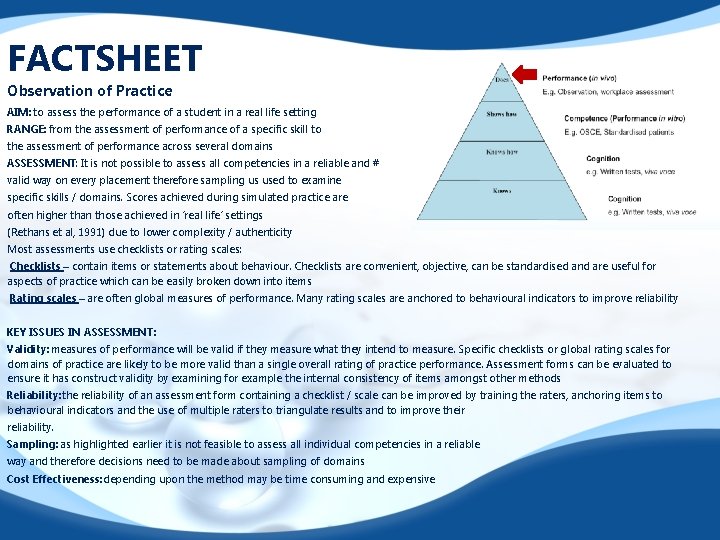

FACTSHEET Observation of Practice AIM: to assess the performance of a student in a real life setting RANGE: from the assessment of performance of a specific skill to the assessment of performance across several domains ASSESSMENT: It is not possible to assess all competencies in a reliable and # valid way on every placement therefore sampling us used to examine specific skills / domains. Scores achieved during simulated practice are often higher than those achieved in ‘real life’ settings (Rethans et al, 1991) due to lower complexity / authenticity Most assessments use checklists or rating scales: Checklists – contain items or statements about behaviour. Checklists are convenient, objective, can be standardised and are useful for aspects of practice which can be easily broken down into items Rating scales – are often global measures of performance. Many rating scales are anchored to behavioural indicators to improve reliability KEY ISSUES IN ASSESSMENT: Validity: measures of performance will be valid if they measure what they intend to measure. Specific checklists or global rating scales for domains of practice are likely to be more valid than a single overall rating of practice performance. Assessment forms can be evaluated to ensure it has construct validity by examining for example the internal consistency of items amongst other methods Reliability: the reliability of an assessment form containing a checklist / scale can be improved by training the raters, anchoring items to behavioural indicators and the use of multiple raters to triangulate results and to improve their reliability. Sampling: as highlighted earlier it is not feasible to assess all individual competencies in a reliable way and therefore decisions need to be made about sampling of domains Cost Effectiveness: depending upon the method may be time consuming and expensive

Specific types of performance assessments Multi-source feedback (MSF)– this tool collects evidence about a student’s performance from multiple sources. Some MSF measures also involve self rating by the student which allows for the exploration of the student’s perceived performance against how their performance has been judged by others. The results of MSF are generally presented graphically and may be reviewed by the student in conjunction with his / her practice teacher Observed skills – these are short checklists or rating scales for a specific procedure which is observed by one or more raters Patient Assessment (PA)– patient satisfaction surveys are widely used by NHS organisations to assess quality. Patients are also now used to assess healthcare professionals / students around interpersonal skills, dignity and respect etc. Educational Impact: the main educational impact of assessments of performance are twofold. Firstly, awareness of the assessment criteria enables the student to focus their learning and development around what is required in the assessment. Sampling of performance reduces the risk associated with a single assessment, on a single day. However, in turn encourages the student to strive for consistent performance over a period rather than ‘gearing up’ and focusing on a single assessment. Finally, the feedback and ratings should enable the student to plan their future development and learning needs.

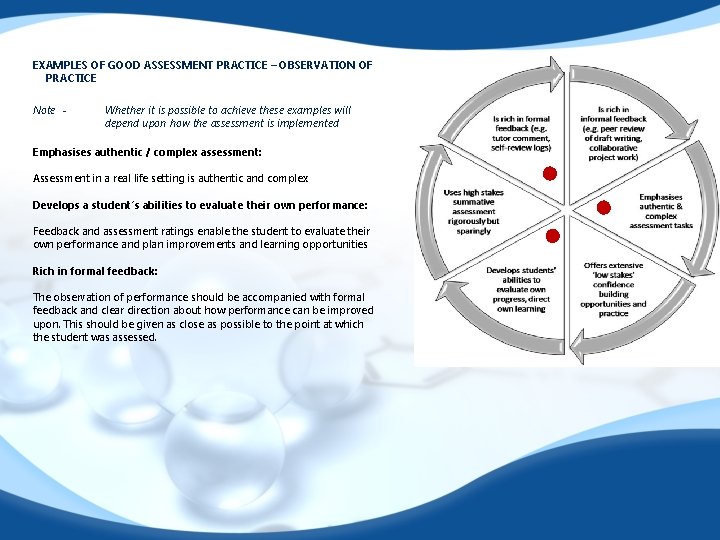

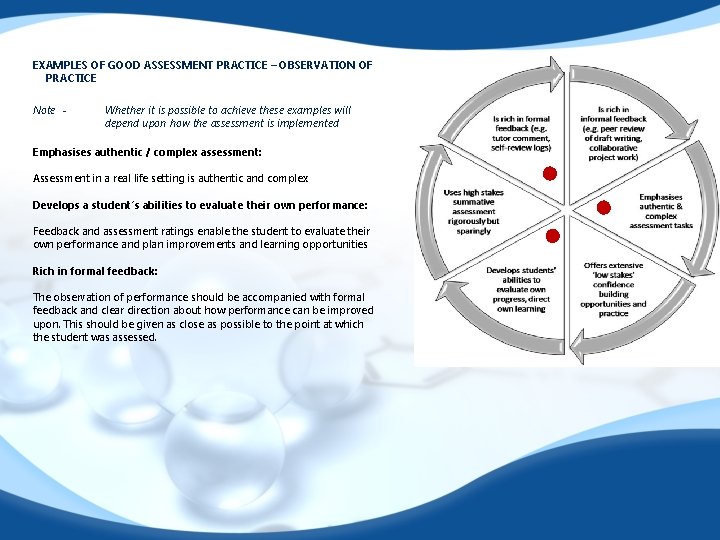

EXAMPLES OF GOOD ASSESSMENT PRACTICE – OBSERVATION OF PRACTICE Note - Whether it is possible to achieve these examples will depend upon how the assessment is implemented Emphasises authentic / complex assessment: Assessment in a real life setting is authentic and complex Develops a student’s abilities to evaluate their own performance: Feedback and assessment ratings enable the student to evaluate their own performance and plan improvements and learning opportunities Rich in formal feedback: The observation of performance should be accompanied with formal feedback and clear direction about how performance can be improved upon. This should be given as close as possible to the point at which the student was assessed.

Glossary Human Factors: are all the non-technical factors that impact on patient care in medicine. Human factors have enormous breadth including human behaviour, interactions between professionals, design of equipment, systems and environment.

![References Baume D A 2001 Briefing on the Assessment of Portfolios Online Available at References Baume, D. A. (2001) Briefing on the Assessment of Portfolios. [Online]. Available at:](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/6d85e501801456028424c8780bf1cc36/image-38.jpg)

References Baume, D. A. (2001) Briefing on the Assessment of Portfolios. [Online]. Available at: http: //www. bioscience. heacademy. ac. uk/ftp/re (Accessed: 17 August 2011). Biggs, J. and Tang, C (2007) Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 3 rd edn. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press Center for Teaching and Learning (1990) http: //cfe. unc. edu/pdfs/FYC 8. pdf. Accessed 10 July 2011 Clouder, L. and Toms, J. (2005) An evaluation of the validity of assessment strategies used to grade practice learning in undergraduate physiotherapy students. Academy: York Higher Education Davis, M. H. , Ponnamperuma, G. G. and Ker, J. S. (2009) ‘Student perceptions of a portfolio assessment process’, Medical Education, 43(1), pp. 89 - 98, EBSCO [Online]. Available at: http: //web. ebschohost. com (Accessed: 21 September 2011) Driessen, E. , Overeem, K. , van Tartwijk, J. , van der Vleuten, C. P. (2006) ‘ Validity of portfolio assessment: which qualities determine ratings? ’, Medical Education, 40(9), pp. 862 866, EBSCO [Online]. Available at: http: //web. ebschohost. com (Accessed: 21 September 2011) Driessen, E. , van Tartwijk, J. , van der Vleuten, C. and Wass, V. (2007) ‘Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review’, Medical Education, 41(12), pp. 1224 - 1233, EBSCO [Online]. Available at: http: //web. ebschohost. com (Accessed: 21 September 2011) Duchy, F. , Segers, M. , Gujbels, D. and Striven, K. (2007) ‘Assessment engineering: breaking down barriers between teaching and learning, and assessment’, in Boud, D. and Falchikov, N. (ed. ) Rethinking assessment in Higher Education. London: Routledge, pp. 87 -100. Jackson, N. , Jamieson, A and Khan, A (2007) Assessment in Medical Education & Training: a practical guide. Radcliffe: London Jasper, M. (2003) Beginning Reflective Practice. Cheltenham: Nelson Thornes. Hamid B (2007) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives – Fact Sheet 12. com. ksau-hs. edu. sa/eng/images/DME_Fact_Sheets/fact_sheet_12_final. doc. Accessed 18 July 2011 Harper R (2003) Multiple Choice Questions – a reprieve. BEE-j. 2, 2 -6. http: //bio. itsn. ac. uk/journal/vol/beej-2 -6. htm. Accessed 16 July 2011 Higher Education Academy (HEA) UKCLE http: //www. ukcle. ac. uk/resources/assessment-and-feedback/mcqs/ten/ Accessed 15 July 2011 Knight, P. K. and Yorke, M (2003) Assessment, Learning and Employability. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press. Learning Technology Unit (LTU) (2009) Multiple Choice Questions. http: //www. leedsmet. ac. uk/health/ltu/areas/assessment/mcq/index. html Accessed 20 July 2011 Levine, H. G. And Mc. Guire, C. H. (1970) Mc. Cann, L. And Saunders, G. (2009) Exploring student perceptions of Assessment Feedback. Higher Education Academy SWAP Report. HEA: York Mc. Coubrie, P. (2010) Metrics in Medical Education. The Ulster Medical Society, 79; 52 -56 Mc. Lachan, J. C. (2006) The relationship between assessment and learning. Medical Education, 40; 716 -717 Medvarsity (2009) Multiple choice questions – the facts. http: //medvarsity. com/vmul 1. 2/st/lp/ole/mcqfacts. html. Accessed 20 July 2911 Miller, G. E. (1990) The assessment of clinical skills, competence, performance. Academic Medicine, 65; S 63 -S 67

Messick, S. (1995) Validity of Psychological assessment: validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol, 50; 741 -749 Newble, D. I. and Jaeger, K. (1983) The effect of assessments and examinations on learning of medical students. Medical Education, 17; 165 -171 Ommundsen P (1999)Biology Case Studies in Multiple-choice Questions http: //capewest. ca/mc. html. Accessed 12 July 2011 Downing, S. M. (2004) Reliability: on the reproducibility of assessment data Medical Education 38 (9), 1006– 1012. doi: 10. 1111/j. 1365 -2929. 2004. 01932. x van der Vleuten, C. P. M and Schuwirth, L. W. T. (2005) Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Medical Education , 39; 309 -317 Wass, V. , Bowden, R and Jackson, N. (2007) The principles of assessment design. In Assessment in Medical Education and Training (Neil Jackson et al Eds) Radcliffe: London Wass, V. , va der Vleuten, C. , Shatzer, J. , Jones, R. (2001) Assessment of clinical competence. Lancet, 357; 945 -949

Produced by the Assessment Cross Programme Group 2011