READERRESPONSE CRITICISM Literary and Critical Theories Lou Myers

- Slides: 85

READER-RESPONSE CRITICISM Literary and Critical Theories

Lou Myers The cover of the book is a cartoon by Lou Myers (1915 – 2005)

Literary criticism has always involved three inescapable elements: the author, the work, and the reader. (Weele 125) Reader-response criticism regards the third of these elements as the most crucial for criticism, for criticism always begins in the first instance with reading. (Weele 125)

As its name implies, reader-response criticism focuses on readers’ responses to literary texts. Reader-response criticism is a broad, exciting, evolving domain of literary studies that can help us learn about our own reading processes and how they relate to, among other things, specific elements in the texts we read, our life experiences, and the intellectual community of which we are a member. (Tyson 153).

Reader-response criticism covers a good deal of diverse ground such as psychoanalytic criticism (when it investigates the psychological motives for certain kinds of interpretations of a literary text), feminist criticism (when it analyzes how patriarchy teaches us to interpret texts in a sexist manner), structuralist criticism (when it examines the literary conventions a reader must have consciously or unconsciously internalized in order to be able to read a particular literary text). (Tyson 153 -154).

READER-RESPONSE CRITICISM Reader-Response theory, which did not receive much attention until the 1970 s, maintains that what a text is cannot be separated from what it does. For despite their divergent views of the reading process, reader-response theorists share two beliefs: 1. that the role of the reader cannot be omitted from our understanding of literature 2. that readers do not passively consume the meaning presented to them by an objective literary text; rather they actively make the meaning they find in literature. This second belief, that readers actively make meaning, suggests that different readers may read the same text quite differently. (Tyson 154).

In fact, reader-response theorists believe that even the same reader reading the same text on two different occasions will probably produce different meanings because so many variables contribute to our experience of the text. Knowledge we’ve acquired between our first and second reading of a text, personal experiences that have occurred in the interim, a change in mood between our two encounters with the text, or a change in the purpose for which we’re reading it can all contribute to our production of different meanings for the same text. (Tyson 154).

THE HOUSE The two boys ran until they came to the driveway. “See, I told you today was good for skipping school, ” said Mark. “Mom is never home on Thursday, ” he added. Tall hedges hid the house from the road so the pair strolled across the finely landscaped yard. “I never knew your place was so big, ” said Pete. “Yeah, but it’s nicer now than it used to be since Dad had the new stone siding put on and added the fireplace. ” There were front and back doors and a side door which led to the garage which was empty except for three parked 10 -speed bikes. They went in the side door, Mark explaining that it was always open in case his younger sisters got home earlier than their mother.

Pete wanted to see the house so Mark started with the living room. It, like the rest of the downstairs, was newly painted. Mark turned on the stereo, the noise of which worried Pete. “Don’t worry, the nearest house is a quarter of a mile away, ” Mark shouted. Pete felt more comfortable observing that no houses could be seen in any direction beyond the huge yard. The dining room, with all the china, silver and cut glass, was no place to play so the boys moved into the kitchen, where they made sandwiches. Mark said they wouldn’t go to the basement because it had been damp and musty ever since the new plumbing had been installed.

“This is where my Dad keeps his famous paintings and his coin collection, ” Mark said as they peered into the den. Mark bragged that he could get spending money whenever he needed it since he’d discovered that his Dad kept a lot in the desk drawer. There were three upstairs bedrooms. Mark showed Pete his mother’s closet which was filled with furs and the locked box which held her jewels. His sister’s room was uninteresting except for the color TV, which Mark carried to his room. Mark bragged that the bathroom in the hall was his since one had been added to his sisters’ room for their use. The big highlight in his room, though, was a leak in the ceiling where the old roof had finally rotted. (This passage, taken from a psychological study conducted by J. A. Pichert and R. C. Anderson, is used by Lois Tyson to teach reader-response theory. Tyson 155)

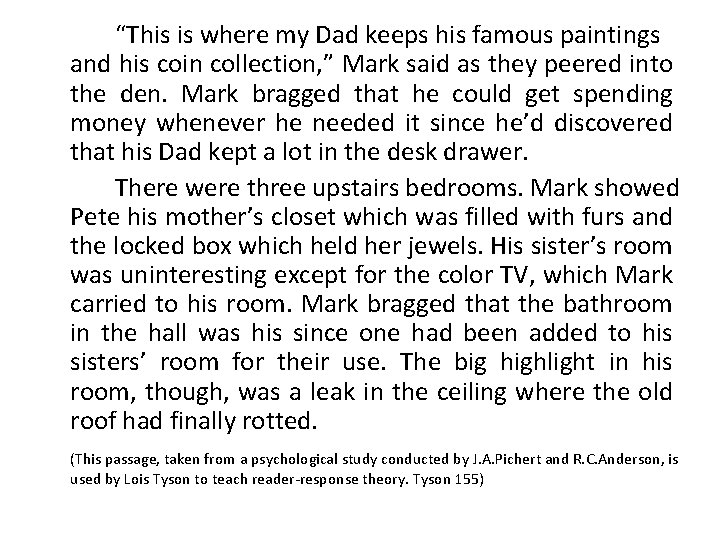

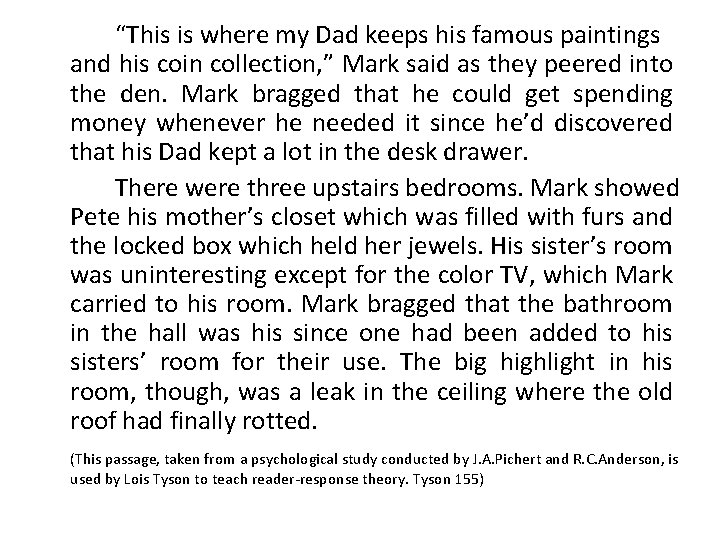

Imagine that you are a home buyer and circle any detail, positive or negative, that you think would be important if you were considering buying the house described in the passage. Positive Qualities Negative Qualities • • • tall hedges (privacy) finely landscaped yard stone siding fireplace garage newly painted downstairs nearest house ¼ mi. away (privacy) den 3 upstairs bedrooms New bathroom added to bedroom damp, musty basement new plumbing amiss rotting roof leak in bedroom ceiling

Now reread the passage and underline any detail, positive or negative, that you think would be important if you were casing the house in order to rob it. • • Positive Qualities tall hedges (safe from observation) no one home on Thursdays finely landscaped yard (those folks have money) 3 10 -speed bikes in garage, side door always left open Nearest house ¼ mi. away (safe from observation) many portable goods: stereo, china, silver, cut glass, paintings, coin collection, furs, box of jewels, tv set cash kept in desk drawer (Tyson 156).

«The house of fiction has in short not one window, but a million – a number of possible windows not to be reckoned, rather; every one of which has been pierced, or is still pierceable, in its vast front, by the need of the individual vision and by the pressure of the individual will. » Henry James, Preface to the New York Edition of Portrait of a Lady (Bressler 72)

According to the nineteenth-century novelist, essayist, literary critic, and short story writer Henry James (1843 -1916), this house represents the literary form – a story, a novel, a poem, or an essay – with each window being an individual reader’s distinct impression of that literary work. (Bressler 73).

Reader-Response critics, Reader-oriented critics, reader-critics, or audience-oriented critics believe that a literary work’s interpretation is created when a reader and a text interact or transact. They assert that the proper study of textual analysis must consider both the reader and the text, not simply a text in isolation. For these critics, Reader + Text = Poem (Meaning)

Meaning can emerge only with a reader actively involved in the reading process with the text. Meaning is context dependent and intricately associated with the reading process. Their chief interest is what occurs when a text and a reader interact or transact. During this exchange, reader-oriented critics investigate and theorize whether the reader, the text, or some combination finally determine the text’s interpretation. (Bressler 80).

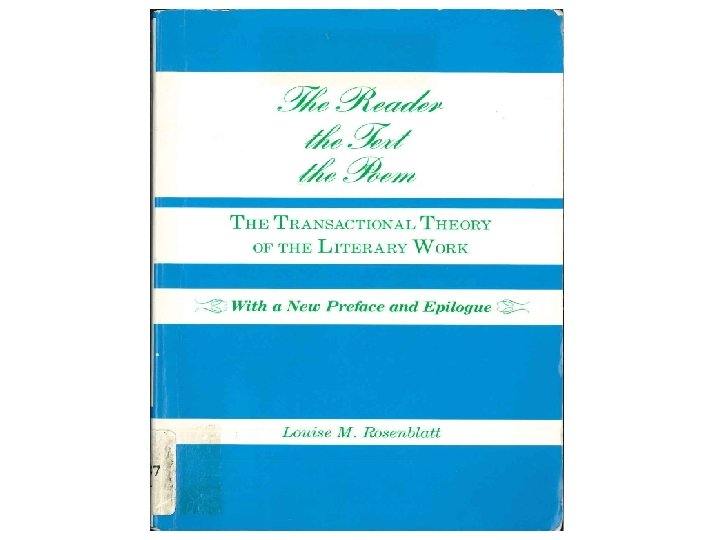

Transactional Reader-Response Theory Often associated with the work of Louise Rosenblatt, who formulated many of its premises, transactional reader-response theory analyzes the transaction between text and reader. In the 1930 s, Rosenblatt, literary theorist, author, scholar, and professor of literacy, further developed Richards’s earlier assumptions concerning the contextual nature of the reading process. She asserts that both the reader and the text must work together to produce meaning. Rosenblatt does not reject the importance of the text in favor of the reader; rather she claims that both are necessary in the production of meaning. She differentiates among the terms text, which refers to the printed words on the page; reader; and poem, which refers to the literary work produced by the text and the reader together. Unlike the New Critics, she shifts the emphasis of textual analysis away from the text alone and views the reader and the text as partners in the interpretative process. (Tyson 157 -158, Bressler 78)

Louise M. Rosenblatt For Rosenblatt, a text is not an autotelic artifact, and there are no generic literary works or generic readers. Instead, there are millions of potential individual readers of the potential millions of individual texts. Readers bring their individual personalities, their memories of past events, their present concerns, their particular physical condition, and all of their personhood to the reading of a text. Rosenblatt asserts the validity of multiple interpretations of a text shaped not only by the text but also by the reader. (Bressler 78).

The Reader, The Text, the Poem, written by Rosenblatt, was published in 1978 and became a pivotal force in helping to cause a paradigm shift in the teaching of literature by changing the focus from the text alone to a reader’s individual response to a text as a key element in the interpretive process. According to Rosenblatt, the reading process involves both a reader and a text. The reader and the text participate in or share a transactional experience: The text acts as a stimulus for eliciting various past experiences, thoughts, and ideas from the reader, those found in both our everyday existence and in past reading experiences. (Bressler 78 -79).

Through this transactional experience, the reader and the text produce a new creation, a poem. For Rosenblatt and many other readeroriented critics, a poem is defined as the result of an event that takes place during the reading process, or what Rosenblatt calls the “aesthetic transaction”. A poem is created each time a reader transacts with a text, whether this transaction is a first reading or any one of countless rereading of the same text. For Rosenblatt, readers read in one of two ways: efferently or aesthetically. (Bressler 79).

When we read for information, we are engaging in efferent reading. During this process, we are interested only in newly gained information. When we read efferently, we are motivated by specific needs to acquire information. When we engage in aesthetic reading, we experience the text. We note its every word, its sounds, its patterns, and so on. When reading aesthetically we involve ourselves in an elaborate give-and-take encounter with the text. (Bressler 79).

In order for the transaction between text and reader to occur, our approach to the text must be, in Rosenblatt’s words, aesthetic rather than efferent. When we read in the efferent mode, we focus just on the information contained in the text. Without the aesthetic approach, there could be no transaction between text and reader to analyze. (Tyson 158).

“The playwright is nothing without his audience. He is one of the audience who happens to know how to speak” Arthur Miller (1915 -2005) Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” (1949) is a play about a travelling salesman who kills himself so that his son will receive his life-insurance money. This is an example of an efferent reading of the text. Willy Loman’s plight is powerfully evoked by the contrast between his small house and the large, orange-colored apartment buildings that surround it. This is an example of an aesthetic reading of the text. (Tyson 158)

In “Death of a Salesman” we might say, for example, that the text’s determinate meaning includes the fact that Willy habitually lies to Linda about his success on the job, about how well liked he is, and about how important his role in the company has been. The play’s indeterminacy includes issues such as how much (or how little) of the truth Linda knows about her husband’s career, at what point she realizes the truth (if ever she does), and why she doesn’t let Willy tell her the truth about his shortcomings when he tries to do so. (Tyson 159).

What differentiates Rosenblatt’s and all readeroriented critics from other critical approaches (especially New Criticism) is their purposive shift in emphasis away from the text as the sole determiner of meaning. No longer is there one correct interpretation and no longer is the reader passive. On the contrary, the reader is an active participant along with the text in creating meaning. It is from the literacy experience that meaning evolves. (Bressler 79 -80).

These questions lead reader-oriented critics to a further narrowing and developing of terminology: What is a text? Is it simply the words or symbols on a page? How can we differentiate between what is actually in the text and what is in the mind of the reader? Who is this reader? Are there various kinds of readers? Is it possible that different texts presuppose different kinds of readers? What about a reader’s response to a text? Are the responses equivalent to the text’s meaning? Can one reader’s response be more correct than another reader’s, or are all responses of equal validity? (Bressler 81).

Although readers respond to the same text in a variety of ways, why many readers individually arrive at the same conclusions or interpretations of the same text? What part, if any, does the author play in a work’s interpretation? Can the author’s attitudes toward the reader actually influence a work’s meaning? If a reader knows the author’s clearly stated intentions for a text, does this information have any part in creating the text’s meaning, or should an author’s intentions for a work be ignored? The concerns of reader-oriented critics can be best summarized in one question: What is and what happens during the reading process? (Bressler 81).

• The reader, including his or her view of the world, background, purpose for reading, knowledge of the world, knowledge of words • The text, with all its various linguistic elements • Meaning, or how the text and the reader interact or transact so that the reader can make sense of the printed material (Bressler 81).

Prince’s concerns about the reader place him in the reader-oriented school of criticism, though such an approach relies heavily on textual analysis. Narratology is the process of analyzing a story using all the elements involved in its telling, such as narrator, voice, style, verb tense, personal pronouns, audience, and so forth. In the 1970 s, Gerard Prince helped develop a specific kind of structuralism known as narratology. Prince noted that critics often ask questions about the story’s point of view – omniscient, limited, first person – but rarely ask about the person to whom the narrator is speaking, the narratee. Prince argues that the narrative itself, the story, produces the narratee. Prince believes it is possible not only to identify the narratee but also to classify stories based on the different kinds of narratees created by the texts themselves. Such narratees may include the real reader (person actually reading the book), the virtual reader (the reader to whom the author believes he or she is writing), and the ideal reader (the one who explicitly and implicitly understands all the nuances, terminology, and structure of the text). (Bressler 83).

Second group of reader-oriented critics follow Rosenblatt’s assumption that the reader is involved in a transactional experience when interpreting a text. Both the text and the reader play somewhat equal parts in the interpretative process. For them, reading is an event that culminates in the creation of the poem. Many adherents in this group – Wolfgang Iser, Hans Robert Jauss, Roman Ingarden – are often associated with phenomenology. (Bressler 83).

Phenomenology is a modern philosophical tendency that emphasizes the perceiver. For phenomenologists, objects can have meaning only if an active consciousness (a perceiver) absorbs or notes their existence. In other words, objects exist if we register them in our consciousness. Rosenblatt’s definition of a poem directly applies this theory. The true poem can exist only in the reader’s consciousness, not on the printed page. When a reader and text transact, the poem and, therefore, meaning are created; they exist only in the consciousness of the reader. (Bressler 84).

Reading and textual analysis now become an aesthetic experience, in which both the reader and the text combine in the consciousness of the reader to create the poem. So, the reader’s imagination must work, fill in the gaps in the text and conjecture about characters’ actions, personality traits, and motives. The ideas and practices of tworeader-oriented critics, Jauss and Iser, serve to illustrate phenomenology’s methodology. (Bressler 84).

Toward the end of the 1960 s, The German critic Hans Robert Jauss emphasizes that a text’s social history must be considered when interpreting the text. He espouses reception theory and asserts that readers from any given historical period devise for themselves the criteria whereby they will judge a text. Jauss argues that because each historical period establishes its own horizons of expectation, the overall value and meaning of any text can never become fixed or universal; readers from any given historical period establish for themselves what they value in a text. A text, then, does not have one and only one correct interpretation because its supposed meaning changes from one historical period to another. A final assessment about any literary work thus becomes impossible. Jauss declares that although the text itself remains important in the interpretive process, the reader plays an essential role. (Bressler 84).

• The German phenomenologist Wolfgang Iser borrows and amends Jauss’s ideas. Iser believes that any object – a stone, a house, a poem – does not achieve meaning until an active consciousness recognizes or registers this object. He declares that as soon as a text is read, the object and the reader (the perceiver) are essentially one. Iser differentiates two kinds of readers. The first is the implied reader, who “embodies all those predispositions necessary for a literary work to exercise its effect… consequently, the implied reader… has his or her roots firmly planted in the structure of the text” (Iser, 1978). In other words, the implied reader is the reader implied by the text, one who is predisposed to appreciate the overall effects of the text. The actual reader is the person who physically picks up the text and reads it. This reader comes to the text shaped by particular cultural and personal norms and prejudices. (Bressler 84 -85).

Similar to Jauss, Iser disavows the New Critical stance that a text has one and only one correct meaning and asserts that a text has many possible interpretations. For Iser, texts do not possess meaning. When a text is concretized, ( the phenomenological concept whereby the text registers in the reader’s consciousness) the reader automatically views the text from his or her personal worldview. As texts do not tell the reader everything that needs to be known about a character, a situation, a relationship, or other such textual elements, readers must automatically fill in these “gaps”, using their own knowledge, worldview. In addition, each reader creates his or her own horizons of expectation –that is, expectations about what will or may or should happen next. (Bressler 85).

So, Filling in the text’s gaps = making sense of the text = continually adopting new horizons of expectation According to Iser, each reader makes “concrete” the text; each concretization is, therefore, personal, allowing the new creation to be unique. The reader is an active, essential player in the text’s interpretation, writing part of the text as the story is read and concretized and, indispensably, becoming its coauthor. (Bressler 86).

Wolfgang Iser • As a literary text can only produce a response when it is read, it is virtually impossible to describe this response without also analyzing the reading process. Reading is therefore the focal point of this study, for it sets in motion a whole chain of activities that depend both on the text and on the exercise of certain basic human faculties. Effects and responses are properties neither of the text nor of the reader; the text represents a potential effect that is realized in the reading process (Iser ix). • Aesthetic response is therefore to be analyzed in terms of a dialectic relationship between text, reader, and their interaction. It is called aesthetic response because, although it is brought about by the text, it brings into play the imaginative and perceptive faculties of the reader, in order to make him adjust and even differentiate his own focus (Iser x). • «Central to the reading of every literary work is the interaction between its structure and its recipient» (Iser 20). • «The literary work has two poles, which we might call the artistic and the aesthetic: the artistic pole is the author’s text and the aesthetic is the realization accomplished by the reader» (Iser 21).

Subjective Reader-Response Theory Psychological Reader-Response Theory The third group of reader-oriented critics place the greatest emphasis on the reader in the interpretative process. For these psychological or subjective critics, the reader’s thoughts, beliefs, and experiences play a greater part than the actual text in shaping a work’s meaning. Led by Norman Holland David Bleich, these critics assert that readers shape and find their self-identities in the reading process. (Bressler 86).

Similar to Rosenblatt, Holland asserts that the reading process is a transaction between the text and the reader. The text is indeed important because it contains its own themes, unity and structure. A reader, however, transforms a text into a private world, a place where the reader works out his or her fantasies, which are actually mediated by the text so that they will be socially acceptable. For Holland, all interpretations are subjective. Unlike New Criticism, his reader-oriented approach asserts that no “correct interpretation” exists. From his perspective, there as many valid interpretations as there are readers because the act of interpretation is a subjective experience in which the text is subordinated to the individual reader. (Bressler 86).

Norman Holland uses Freudian psychoanalysis as the foundation for his theory and practices formulated in the early 1970 s. He believes that at birth we receive from our mothers a primary identity. We personalize this identity through our life’s experiences, transform it into our own individualized identity theme that becomes the lens through which we see the world. Textual interpretation becomes a matter of working out our own fears, desires, and needs to help maintain our psychological health. (Bressler 86).

Norman Holland’s central thesis is that people deal with literary texts the same way they deal with life-experience. Each person develops a particular style of coping what Holland calls an identity theme. (Tompkins xix). Dynamics described three parts: Fantasy, defense (or form), meaning

• Fantasies may be conscious and unconscious. A fantasy usually combines several wishes. • A literary text transforms fantasy by defenses. In literature, form transforms fantasy toward an acceptable meaning. Dynamics also dealt with form as small verbal details. • Conscious meaning is only the tip of the iceberg.

NORMAN HOLLAND xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx “The text has a direction; it begins, progresses, and ends. But a skilled reader also gives the text meaning by making connections between all parts of the text, regardless of direction or position…. The skilled reader abstracts recurring images, incidents, characters, forms and all the rest into certain themes” (Holland 28).

(Holland 28 -29). In the Dynamics model, a literary text transforms the fantasy by defenses. That is, in ordinary life, our minds transform the raw drives of id into socially or personally acceptable actions by defenses such as repression, denial, reversal or sublimation. So in literature, form transforms fantasy toward an acceptable meaning. (Holland viii). The dynamics of literary response is not taking place within a text which a person introjects but between a person and a text. (Holland xi).

David Bleich is the founder of “subjective criticism”. He agrees with Holland’s psychological explanation of the interpretive process, but Bleich devalues the role of the text plays, denying its objective existence. Bleich argues that meaning does not reside in the text but is developed when the reader works in cooperation with other readers to achieve the text’s collective meaning. When each reader is able to articulate his or her individual responses about the text within a group, then, can the group, working together, negotiate meaning. Such communally motivated negotiations ultimately determine the text’s meaning. For Bleich, the starting point for interpretation is the reader’s responses to a text, not the text itself. However, these responses do not constitute the text’s meaning because meaning can not be found within a text or within responses to the text. Rather, a text’s meaning must be developed from and out of the reader’s responses, working in conjunction with other readers’ responses and with past literary and life experiences. So, Bleich differentiates between the reader’s responses to a text and the reader’s interpretation or meaning, which must be developed communally in a classroom or similar setting. (Bressler 86 -87).

For Bleich and his adherents, the key to developing a text’s meaning is the working out of one’s responses to a text so that these responses will be challenged, amended, and then accepted by one’s social group. When reading a text, a reader may respond to something in the text in a bizarre and personal way. Through discussion, these private responses are pruned away by members of the reader’s social group. The group decides on the acceptable interpretation of the text. Only through negotiations with other readers and other texts – intertextuality – can one develop the text’s meaning. (Bressler 87).

Reading is an activity, something you do. (Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in this Class? )

IS THERE A TEXT IN THIS CLASS? The answer this book gives to its title question is «there is» and «there isn’t» . • There isn’t a text in this or any other class if one means by text “an entity which always remains the same from one moment to the next”. • But there is a text in this and every class if one means by text the structure of meanings that is obvious and inescapable from the perspective of whatever interpretive assumptions happen to be in force. (Fish vii)

Social Reader-Response Theory Affective Stylistics • Interpretive community is a term coined by Stanley Fish to designate a group of readers who share the same interpretive strategies. Fish, a contemporary reader-oriented critic, has coined the term affective stylistics or reception aesthetics to describe his reading strategy. Fish argues that meaning inheres in the reader, not the text. A text’s meaning resides in the reading community to which a reader belongs, or what Fish calls the interpretive community. This community or (these communities) ultimately invests meaning. (Bressler 88).

Unlike the New Critics, Fish declares that the objectivity of a text is an illusion because the text is a tabula rasa, a blank slate upon which the reader writes the actual text. The reader determines the form and content of the text. Not the text but the reader is preeminent. (Bressler 88).

The term Reader-oriented criticism allows for so much divergence in theory and methods. Such an eclectic membership denotes the continued growth and ongoing development of reader-oriented criticism. As reader-oriented critics use a variety of methodologies, there is no particular list of questions. Nevertheless, by asking the following questions, one can participate in both theory and practice of readeroriented criticism: (Bressler 88).

• • • Who is the actual reader? Who is the implied reader? Who is the ideal reader? Who is the narratee? What are some gaps you see in the text? Can you list several horizons of expectations and show they change from a particular text’s beginning to its end? Using Jauss’s definition of horizons of expectation, can you develop (first on your own and then with your classmates) an interpretation of a particular text? Can you articulate your identity theme as you develop your personal interpretation of a particular text? Using Bleich’s subjective criticism, can you state the difference between your response to a text and your interpretation? In a classroom setting, develop your class’s interpretive strategies for arriving at the meaning of a particular text. As you interpret this text, can you cite the interpretive community or communities to which you, the reader, belong? (Bressler 88).

Because all reader-oriented critics agree that the individual reader creates the text’s meaning, reader-oriented criticism declares that there can be no correct meaning for any text; instead many valid interpretations are possible. What the reading process is and how readers read are major concerns for all reader-oriented critics. The answers to these and similar questions are widely divergent. (Bressler 89).

Iser’s gap theory, Rosenblatt’s transactional theory, and Fish’s rather relativistic assumption that no text can exist until either the reader or an interpretive community creates it are significant. Do African-Americans read differently from European Americans? How do women read? How do men read? In other words, different schools of criticism such as feminism, gender studies, have embraced the principles of reader-oriented criticism. (Bressler 90).

“Tell me, glass, tell me true! Of all the ladies in the land, Who is fairest, tell me who? ” […] “Thou, queen, art the fairest in all the land. ” […] “Thou, queen, art fair, and beauteous to see, But Snow White is lovelier far than thee!” […] “Thou, queen, art the fairest in all this land: But over the hills, in the greenwood shade, Where the seven dwarfs their dwelling have made, There Snow White is hiding her head; and she Is lovelier far, O queen! than thee. ” […] “Thou, lady, art loveliest here, I ween; But lovelier far is the new-made queen. ”

Grimm, J. L. C. and Grimm W. C. , “Snow White” in Grimms’ Fairy Tales, London: CRW Publishing Limited, 2004: 199 -208

Midwinter – Invincible, Immaculate. The Count and his wife go riding, he on a grey mare and she on a black one, she wrapped in the glittering pelts of black foxes; and she wore high, black, shining boots with scarlet heels, and spurs. Fresh snow fell on snow already fallen; when it ceased, the whole world was white. “I wish I had a girl as white as snow, ” says the Count. They ride on. They come to a hole in the snow; this hole is filled with blood. He says: “I wish I had a girl as red as blood. ” So they ride on again; here is a raven, perched on a bare bough. “I wish I had a girl as black as that bird’s feather. ” As soon as he completed her description, there she stood, beside the road, white skin, red mouth, black hair and stark naked; she was the child of his desire and the Countees hated her. The Count lifted her up and sat in front of him on his saddle but the Countess had only one thought: how shall I be rid of her? The Countess dropped her glove in the snow and told the girl to get down to look for it; she meant to gallop off and leave her there but the Count said: “I’ll buy you new gloves. ” At that, the furs sprang off the Countess’s shoulders and twined round the naked girl. Then the Countess threw her diamond brooch through the ice of a frozen pond: “Dive in and fetch it for me, ” she said; she thought the girl would drown. But the Count said: “Is she a fish, to swim in such cold weather? ” Then her boots leapt off the Countees’s feet and on to the girl’s legs. Now the Countess was bare as a bone and the girl furred and booted; the Count felt sorry for his wife. They came to a bush of roses, all in flower. “Pick me one, ” said the Countess to the girl. “I can’t deny you that, ” said the Count.

So the girl picks a rose; pricks her finger on the thorn; bleeds; screams; falls. Weeping, the Count got off his horse, unfastened his breeches and thrust his virile member into the dead girl. The Countess reined in her stamping mare and watched him narrowly; he was soon finished. Then the girl began to melt. Soon there was nothing left of her but a feather a bird might have dropped; a bloodstain, like the trace of a fox’s kill on the snow; and the rose she had pulled off the bush. Now the Countess had all her clothes again. With her long hand she stroked her furs. The Count picked up the rose, bowed and handed it to his wife; when she touched it, she dropped it. “It bites!” she said.

Carter, Angela. “The Snow Child” in The Bloody Chamber. London: Vintage Books, 2006: 105106.

• “Mary Cassatt and Me”, 1976 by Miriam Schapiro • Schapiro made “femmages”, collages which addressed feminist concerns by combining fabric, ribbon, wallpaper, and other traditionally “feminine” materials. (Doss 187 )

Born in Toronto, Canada in 1923, Miriam Schapiro, painter, sculptor, printmaker and “femmagist”, is known as a leader in both the Feminist Art Movement and the Pattern and Decoration Movement.

Definition of "Femmage": 1. It is a work by a woman. 2. The activities of saving and collecting are important ingredients. 3. The theme has a woman-life context.

Feminine materials in Schapiro’s work can be compared with Susan Glaspell’s one-act play, “Trifles” (1916). So, in order to understand these works better, please first read the extract from the play and analyze the quotation. Sheriff: Nothing here but kitchen things. […] Lewis Hale: Well, women are used to worrying over trifles. […] Mrs. Hale: I’d hate to have men coming into my kitchen, snooping around and criticising. […] Mrs. Peters: She said she wanted an apron. Mrs. Hale: Do you think she did it? Mrs. Hale: Well, I don’t think she did. Asking for an apron and her little shawl. Worring about her fruit. […] Mrs. Hale: Mrs. Peters, look at this one. Here, this is the one she was working on, and look at the sewing! All the rest of it has been so nice and even. And look at this! It’s all over the place! Why, it looks as if she didn’t know what she was about! (After she has said this they look at each other, then start to glance back at the door. After an instant Mrs Hale has pulled at a knot and ripped the sewing. )

Mrs. Peters: Oh, what are you doing, Mrs Hale? Mrs Hale: (mildly) Just pulling out a stitch or two that’s not sewed very good. (threading a needle) Bad sewing always made me fidgety. Mrs Peters: (nervously) I don’t think we ought to touch things. Mrs Hale: I’ll just finish up this end. (suddenly stopping and leaning forward) Mrs Peters? Mrs Peters: Yes, Mrs Hale? Mrs Hale: What do you suppose she was so nervous about? […]

“The Story of an Hour” by Kate Chopin Knowing that Mrs. Mallard was afflicted with a heart trouble, great care was taken to break to her as gently as possible the news of her husband’s death. It was her sister Josephine who told her, in broken sentences. […] Her husband’s friend Richards was there, too, near her. She wept at once, with sudden, wild abandonment, in her sister’s arms. When the storm of grief had spent itself she went away to her room alone. She would have no one follow her. There stood, facing the open window, a comfortable, roomy armchair. Into this she sank, pressed down by a physical exhaustion that haunted her body and seemed to reach into her soul. She could see in the open square before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life. The delicious breath of rain was in the air. […] countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves. […]

She was young, with a fair, calm face, whose lines bespoke repression and even a certain strength. But now there was a dull stare in her eyes. […] There was something coming to her and she was waiting for it, fearfully. What was it? She did not know; it was too subtle and clusive to name. But she felt it, creeping out of the sky, reaching toward her through the sounds, the scents, the color that filled the air. Now her bosom rose and fell tumultuously. She was beginning to recognize this thing that was approaching to possess her…. When she abandoned herself a little whispered word escaped her slightly parted lips. She said it over and over under her breath: “Free, free!” […] “Free! Body and soul free!” she kept whispering.

Josephine was kneeling before the closed door with her lips to the keyhole, imploring for admission. “Louise, open the door! I beg; open the door – you will make yourself ill. What are you doing, Louise? For heaven’s sake open the door. ” “Go away. I am not making myself ill. ” No; she was drinking in a very elixir of life through that open window. Her fancy was running riot along those days ahead of her. Spring days, and summer days, and all sorts of days that would be her own […] She arose at length and opened the door to her sister’s importunities. There was a feverish triumph in her eyes, and she carried herself unwittingly like a goddess of Victory. She clasped her sister’s waist, and together they descended the stairs. Richards stood waiting for them at the bottom.

Some one was opening the front door with a latchkey. It was Brently Mallard who entered, a little travel-stained, composedly carrying his grip-sack and umbrella. He had been far from the scene of accident, and did not even know there had been one. He stood amazed at Josephine’s piercing cry; at Richards’ quick motion to screen him from the view of his wife. But Richards was too late. When the doctors came they said she had sied of heart disease –of joy that kills.

Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” (1894) is about a woman, Mrs. Mallard, struggling with heart trouble. Her sister Josephine tells her the news of her husband’s death. She weeps at once. She can see in the open square trees, which can be the symbol for freedom, and new spring life, symbol of rebirth. She can taste the delicious breath of rain in the air. She hears the notes of a distant song and sparrows. She is rediscovering life. However, at the end of the story, she dies when she sees her husband, Brently Mallard, alive. The end of the story may be tragic but a woman’s understanding of what the freedom is apparently more effective.

I belong to that classification of people known as wives. I am a wife. And, not altogether incidentally, I am a mother. Not too long ago a male friend of mine appeared on the scene fresh from a recent divorce. He had one child, who is, of course, with his ex-wife. He is looking for another wife. As I thought about him while I was ironing one evening, it suddenly occurred to me that I, too, would like to have a wife. Why do I want a wife?

I would like to go back to school so that I can become economically independent, support myself, and, if need be, support those dependent upon me. I want a wife who will work and send me to school. And while I am going to school, I want a wife to take care of my children. […] I want a wife who will take care of my physical needs. I want a wife who will keep my house clean. […]

I want a wife who will keep my clothes clean, ironed, mended, replaced when need be, and who will see to it that my personal things are kept in their proper place so that I can find what I need the minute I need it. I want a wife who cooks the meals, a wife who is a good cook. I want a wife who will plan the menus, do the necessary grocery shopping, prepare the meals, serve them pleasantly, and then do the cleaning up while I do my studying. I want a wife who will care for me when I am sick and sympathize with my pain and loss of time from school.

I want a wife who will not bother me with rambling complaints about a wife's duties. If, by chance, I find another person more suitable as a wife than the wife I already have, I want the liberty to replace my present wife with another one. Naturally, I will expect a fresh, new life; my wife will take the children and be solely responsible for them so that I am left free.

When I am through with school and have a job, I want my wife to quit working and remain at home so that my wife can more fully and completely take care of a wife's duties. My God, who wouldn't want a wife? The speech “Why I Want a Wife? ”, a legendary feminist satire, was delivered by Judy Syfers delivered on August 26, 1970.

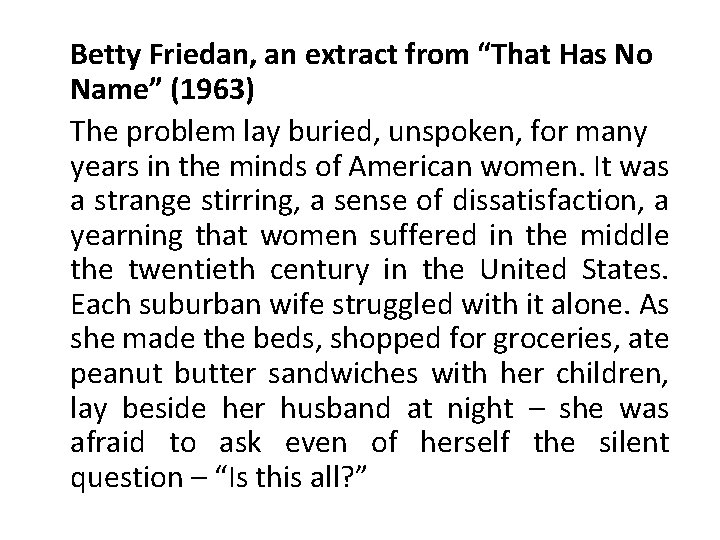

Betty Friedan, an extract from “That Has No Name” (1963) The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, lay beside her husband at night – she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question – “Is this all? ”

In this presentation, all the works of art as the examples reflecting the gender issue are given to indicate the application of Reader-Response Criticism to the literary texts.

Reader-response theory does not aim for uniformity of interpretation, nor does it assume that uniformity is possible; it does, however, help to account for the diversity of interpretations and to encourage participation in a community of interpreters. (Weele 146).

Works Cited • • • Bressler, Charles E. Literary Criticism: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. Fourth Edition. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc. , 2007. Carter, Angela. “The Snow Child” in The Bloody Chamber. London: Vintage Books, 2006: 105 -106. Doss, Erika. Twentieth-Century American Art. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Fish, Stanley. Is There A Text in This Class? : The Authority of Interpretive Communities. London: Harvard University Press, 1980. Grimm, J. L. C. and Grimm W. C. , “Snow White” in Grimms’ Fairy Tales, London: CRW Publishing Limited, 2004: 199 -208 Holland, Norman H. The Dynamics of Literary Response. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. Iser, Wolfgang. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987. Rosenblatt, Louise M. The Reader The Text The Poem: The Transactional Theory of the Literary Work. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994. Tompkins, Jane P. Ed. Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-Structuralism. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. , 1999. Weele, Michael Vander. “Reader-Response Theories” in Contemporary Literary Theory: A Christian Appraisal. Eds. Clarence Walhout and Leland Ryken.

Lou myers gay

Lou myers gay Critical semi critical and non critical instruments

Critical semi critical and non critical instruments Principle of sterilization

Principle of sterilization Definition of psychoanalytic criticism

Definition of psychoanalytic criticism What is constructive criticism

What is constructive criticism Russian formalism slideshare

Russian formalism slideshare Two types of historical criticism

Two types of historical criticism Descriptive criticism vs prescriptive criticism

Descriptive criticism vs prescriptive criticism Critical theories

Critical theories Queer theory in literary criticism ppt

Queer theory in literary criticism ppt Advantages of literary criticism

Advantages of literary criticism Advantages and disadvantages of literary criticism

Advantages and disadvantages of literary criticism Mythological and archetypal approach in literary criticism

Mythological and archetypal approach in literary criticism Slidetodoc.com

Slidetodoc.com Lucy lou and my girl drew

Lucy lou and my girl drew Example of structuralism

Example of structuralism Literary criticism in renaissance

Literary criticism in renaissance Psychological literary criticism

Psychological literary criticism What are the different literary approaches

What are the different literary approaches Uil literary criticism study guide

Uil literary criticism study guide Different literary lenses

Different literary lenses Archetypal criticism questions

Archetypal criticism questions Difference between horace and longinus

Difference between horace and longinus Conclusion of literary criticism

Conclusion of literary criticism Literary criticism approaches

Literary criticism approaches Definition of sociological criticism

Definition of sociological criticism Merchant of venice literary analysis

Merchant of venice literary analysis Structuralism literary criticism

Structuralism literary criticism Deconstruction ppt

Deconstruction ppt Poststructuralist definition

Poststructuralist definition Phallocentrism

Phallocentrism Gender criticism in literature

Gender criticism in literature Feminist literary criticism examples

Feminist literary criticism examples Types of critical lenses

Types of critical lenses Literary archetypes definition

Literary archetypes definition I a richards principles of literary criticism summary

I a richards principles of literary criticism summary Define literary criticism

Define literary criticism Historical/biographical criticism

Historical/biographical criticism Literary approach

Literary approach Ecocriticism purdue owl

Ecocriticism purdue owl Structuralist/formalist definition

Structuralist/formalist definition Psychoanalytic criticism ppt

Psychoanalytic criticism ppt Historical biographical approach to his coy mistress

Historical biographical approach to his coy mistress Structuralism literary theory

Structuralism literary theory Literary criticism map

Literary criticism map Approach in literary criticism

Approach in literary criticism Commodity fetishism

Commodity fetishism Types of literary criticism

Types of literary criticism Tess of the d urbervilles literary criticism

Tess of the d urbervilles literary criticism Reader response criticism cinderella

Reader response criticism cinderella Types of literary criticism

Types of literary criticism Owl purdue subject verb agreement

Owl purdue subject verb agreement Finance brealey and myers

Finance brealey and myers Gruneberg and myers pllc

Gruneberg and myers pllc Myers briggs strengths and weaknesses

Myers briggs strengths and weaknesses Abu ghraib

Abu ghraib Critical lens types

Critical lens types Historical critical lens

Historical critical lens New historicism definition

New historicism definition Applying critical approaches to literary analysis

Applying critical approaches to literary analysis Lou harvey leeds

Lou harvey leeds Pronote clg lou blazer

Pronote clg lou blazer Lou's kitchen dunedin

Lou's kitchen dunedin Wenjing lou

Wenjing lou Lou pai

Lou pai Thought patterns for a successful career pacific institute

Thought patterns for a successful career pacific institute Modelo de walter dick y lou carey

Modelo de walter dick y lou carey Andreas-salomé, lou, la humanidad de la mujer.

Andreas-salomé, lou, la humanidad de la mujer. Pronote college lou blazer

Pronote college lou blazer Fannie lou hamer delta sigma theta

Fannie lou hamer delta sigma theta Fannie lou hamer apush

Fannie lou hamer apush Lou cheng

Lou cheng Lou reiter

Lou reiter Lou tessier

Lou tessier Lifeboat 12 by susan hood

Lifeboat 12 by susan hood Vivian quotes a lesson before dying

Vivian quotes a lesson before dying Mary lou long

Mary lou long Chou lou

Chou lou Language

Language How does lou gehrig establish ethos in his speech

How does lou gehrig establish ethos in his speech Abc lou note taking

Abc lou note taking Lou lappen

Lou lappen Lou fabrizio

Lou fabrizio Lou tessier

Lou tessier Mary lou dunzik-gougar

Mary lou dunzik-gougar Define literary devices

Define literary devices