n n n The Early Stuarts James I

- Slides: 21

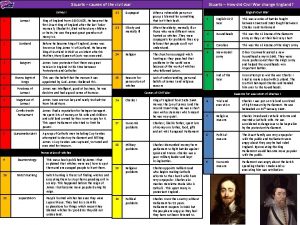

n n n The Early Stuarts James I. Charles I. The English Revolution Long Parliament n Civil War Oliver Cromwell n The Cromwellian Regime n n The Restoration Charles II. James II. William of Orange n The last of the Stuarts n The Union with Scotland 1707 Act of Union n n

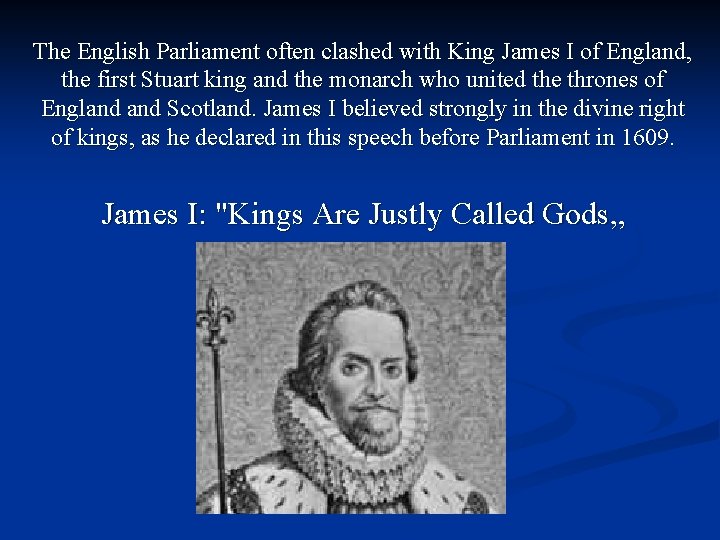

The English Parliament often clashed with King James I of England, the first Stuart king and the monarch who united the thrones of England Scotland. James I believed strongly in the divine right of kings, as he declared in this speech before Parliament in 1609. James I: "Kings Are Justly Called Gods„

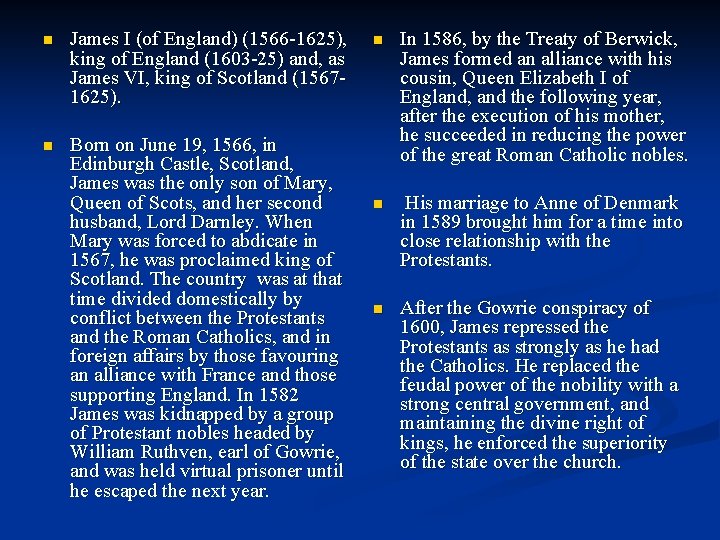

n James I (of England) (1566 -1625), king of England (1603 -25) and, as James VI, king of Scotland (15671625). n Born on June 19, 1566, in Edinburgh Castle, Scotland, James was the only son of Mary, Queen of Scots, and her second husband, Lord Darnley. When Mary was forced to abdicate in 1567, he was proclaimed king of Scotland. The country was at that time divided domestically by conflict between the Protestants and the Roman Catholics, and in foreign affairs by those favouring an alliance with France and those supporting England. In 1582 James was kidnapped by a group of Protestant nobles headed by William Ruthven, earl of Gowrie, and was held virtual prisoner until he escaped the next year. n In 1586, by the Treaty of Berwick, James formed an alliance with his cousin, Queen Elizabeth I of England, and the following year, after the execution of his mother, he succeeded in reducing the power of the great Roman Catholic nobles. n His marriage to Anne of Denmark in 1589 brought him for a time into close relationship with the Protestants. n After the Gowrie conspiracy of 1600, James repressed the Protestants as strongly as he had the Catholics. He replaced the feudal power of the nobility with a strong central government, and maintaining the divine right of kings, he enforced the superiority of the state over the church.

n In 1603 Queen Elizabeth died childless, and James succeeded her as James I, the first Stuart king of England. In 1604 he ended England's war with Spain, but his tactless attitude toward Parliament, based on his belief in divine right, led to prolonged conflict with that body. n His severity toward Roman Catholics, however, led to the abortive Gunpowder Plot in 1605. It was conspiracy to kill James I, king of England, as well as the Lords and the Commons at the opening of Parliament on November 5, 1605. The plot was formed by a group of prominent Roman Catholics in retaliation against the oppressive anti. Catholic laws being applied by James I. The originator of the scheme was Robert Catesby, a country gentleman of Warwickshire. The conspirators discovered a vault directly beneath the House of Lords. They rented this cellar and stored in it 36 barrels of gunpowder. n n In the final arrangement, Fawkes was to set fire to the gunpowder in the cellar on November 5 and then flee to Flanders. Through a letter of warning written to a peer, the plot was exposed. Fawkes was arrested and examined under torture on the rack. He revealed the names of his associates, nearly all of whom were killed on being taken or were hanged along with Fawkes on January 31, 1606. n James tried unsuccessfully to advance the cause of religious peace in Europe, giving his daughter Elizabeth in marriage to Frederick V, the leader of the German Protestants. n He also sought to end the conflict by attempting to arrange a marriage between his son, Charles, and the infanta of Spain, then the principal Catholic power. When he was rejected, he formed an alliance with France and declared war on Spain. n James I died in Hertfordshire on March 27, 1625, and was succeeded to the throne by his son, Charles I.

Charles I (of England) (1600 -1649), n n Charles was born the second son of James I, and became heir apparent when his elder brother, Henry, died, and was made Prince of Wales in 1616. In 1625 Charles succeeded to the throne and married Henrietta Maria, the French princess. Charles believed in the divine right of kings and in the authority of the Church of England. These beliefs soon brought him into conflict with Parliament and ultimately led to civil war. He came under the influence of his close friend George Villiers, 1 st duke of Buckingham, whom he appointed his chief minister in defiance of public opinion and whose war schemes in Spain and France ended unsuccessfully. Charles convoked and dissolved three Parliaments in four years because they refused to comply with his demands ( paymants for military expenditures and imprisoning those who did not pay). When the third Parliament met in 1628, it presented the Petition of Right, a statement demanding that Charles make certain reforms in exchange for war funds. Charles was forced to accept the petition. However, in 1629, Charles dismissed Parliament and had several parliamentary leaders imprisoned. Charles governed without a Parliament for the next 11 years. During this time forced loans, and other extraordinary financial measures were sanctioned to meet governmental expenses. In 1637 Charles's attempt to impose the Anglican liturgy in Scotland led to rioting by Presbyterian Scots. Charles was unable to quell the revolt, and in 1640 he convoked the so-called Short Parliament to raise an army and necessary funds. This body, which sat for one month (April-May), refused his demands, drew up a statement of public grievances, and insisted on peace with Scotland. Obtaining money by irregular means, Charles advanced against the Scots, who crossed the border, routed his army at Newburn, and soon afterward occupied Newcastle and Durham.

n His money exhausted, the king was compelled to call his fifth Parliament, the Long Parliament, in 1640. In 1641 Charles agreed that this Parliament would not be dissolved without its own permission. The king also agreed to more religious liberties for the Scots and to submit to the demands of the Scottish Parliament. n While still in Scotland, the king received word of a rebellion in Ireland in which thousands of English colonists were massacred. When he returned to London in November, he tried to have Parliament raise an army, under his control, to put down the Irish revolt. Parliament, fearing that the army would be used against itself, refused, and issued the Grand Remonstrance, a list of reform demands, including the right of Parliament to approve the king's ministers. Charles appeared in the House of Commons with an armed force. The country was aroused, and the king fled with his family from London.

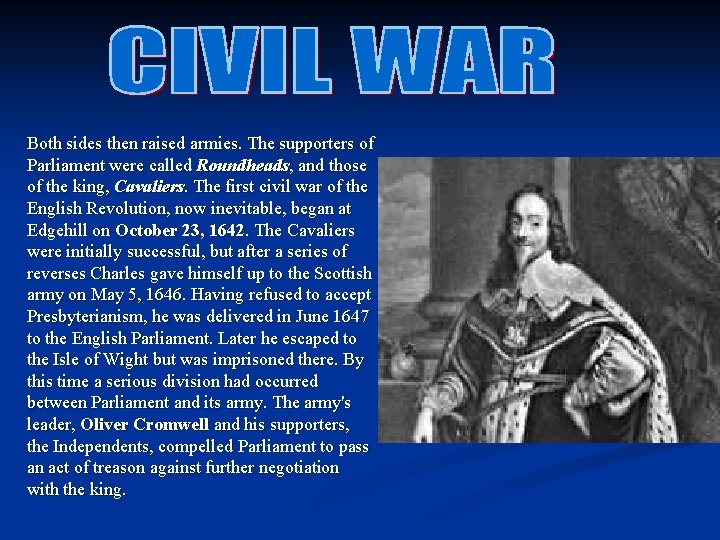

Both sides then raised armies. The supporters of Parliament were called Roundheads, and those of the king, Cavaliers. The first civil war of the English Revolution, now inevitable, began at Edgehill on October 23, 1642. The Cavaliers were initially successful, but after a series of reverses Charles gave himself up to the Scottish army on May 5, 1646. Having refused to accept Presbyterianism, he was delivered in June 1647 to the English Parliament. Later he escaped to the Isle of Wight but was imprisoned there. By this time a serious division had occurred between Parliament and its army. The army's leader, Oliver Cromwell and his supporters, the Independents, compelled Parliament to pass an act of treason against further negotiation with the king.

n Eventually, the moderate Parliamentarians were forcibly ejected by the Independents, and the remaining legislators, who formed the so-called Rump Parliament, appointed a court to try the king. On January 20, 1649, the trial began in Westminster Hall. Charles denied the legality of the court and refused to plead. On January 27 he was sentenced to death as a tyrant, murderer, and enemy of the nation. Scotland protested, the royal family entreated, and France and the Netherlands interceded, in vain. Charles was beheaded at Whitehall, London. Subsequently Oliver Cromwell became chairman of the council of state, a parliamentary agency that governed England as a republic until the restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

n n The problem of settling the government on a permanent basis was never solved. The new Council of State had to depend on the force of the army and the Rump Parliament. Cromwell was the dominant individual. From 1649 to 1651 he subdued Ireland Scotland brought them into the Commonwealth. In 1653 he dissolved the Rump. In December 1653 accepted the Instrument of Government, England's only attempt at a written constitution. The protectorate, which it created, was governed by a House of Commons and Cromwell as Lord Protector. Parliament challenged the restrictions of the Instrument and then proposed the socalled Humble Petition and Advice to amend it. Cromwell accepted a second house of Parliament and the right to name his successor, but refused the title of king. After a Royalist uprising in 1655, Cromwell divided England into 11 military districts commanded by major generals. This, more than anything except the killing of Charles, turned people against Cromwell and taught them to hate Puritans and standing armies. Cromwell pursued an active foreign policy. The Navigation Act of 1651 provoked the Dutch War of 1652 to 1654, from which England gained some success. Jamaica was taken from Spain in 1655. Allied with France, England in 1658 won the Battle of the Dunes and took Dunkerque in France. Not since Elizabeth's reign had English ships and arms been so successful and so respected. The protectorate collapsed after Cromwell died in September 1658, and his son, Richard, was unable to gain the respect of the army. In the ensuing confusion, General George Monck, the commander in Scotland, marched to London, recalled the Long Parliament, and set in motion the return of the dead king's eldest son from

n James II soon lost the goodwill he had inherited. He was too harsh in his suppression of a revolt by James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (an illegitimate son of Charles), in 1685; he created a standing army; and he put Roman Catholics in the government, army, and university. In 1688 his Declaration of Indulgence, allowing Dissenters and Catholics to worship freely, and the birth of a son, which set up a Roman Catholic succession, prompted James's opponents to invite William of Orange, a Protestant and stadtholder of the Netherlands and husband of the king's elder daughter, Mary, to come to safeguard Mary's inheritance. When William landed, James fled, his army having deserted to William. n n William was given temporary control of the government. Parliament in 1689 gave him and Mary the crown jointly, provided that they affirm the Bill of Rights listing and condemning the abuses of James. A Toleration Act gave freedom of worship to Protestant dissenters. This revolution was called the Glorious Revolution because, unlike that of 1640 to 1660, it was bloodless and successful: Parliament was sovereign and England prosperous. It was a victory of Whig principles and Tory pragmatism. Those who would not swear allegiance to the new monarchs were called nonjurors or Jacobites— Jacobus being Latin for James. The Jacobites were most numerous among the Roman Catholics in the Scottish Highlands and in Ireland.

n n Before James II's younger daughter, Anne, came to the throne in 1702, her many children had all died. To prevent a return of the Roman Catholic Stuarts, Parliament in 1701 passed the Act of Settlement, providing that the throne should go next to the Protestant Electress Sophia of Hannover, the granddaughter of James I, and to her descendants. Scotland, angry at its exclusion from trade with the English Empire, hesitated to duplicate the act, as it had the Bill of Rights in 1689. The only solution was to combine the two kingdoms, which was done by the Act of Union of 1707, creating the kingdom of Great Britain.

Act of Union, name of several statutes that accomplished : n the joining of England with Wales (1536), n England Wales with Scotland (1707), n Great Britain with Ireland (1800), n British provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada (1840) in North America. n

n Anne (1665 -1714), queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1702 -14), the last British sovereign of the house of Stuart. Born in London on February 6, 1665, she was the second daughter of King James II. Her mother was James's first wife, Anne Hyde. In 1683 she was married to Prince George of Denmark. Although her father converted to Roman Catholicism in 1672, Anne remained Protestant. Becoming queen on William Orange's death in 1702, Anne restored to favor John Churchill, who had been disgraced by her predecessor, making him duke of Marlborough and captain-general of the army. Marlborough won a series of victories over the French in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 -14, known in America as Queen Anne's War), and he and his wife, Sarah, had great influence over the queen in the early years of her reign. n . During Queen Anne's reign the kingdoms of England Scotland were united (1707). She died in London on August 1, 1714, and, having no surviving children, was succeeded by her German cousin, George, elector of Hannover, as King George I of Great Britain and Ireland.

The restoration and the last stuarts

The restoration and the last stuarts Early cpr and early defibrillation can: *

Early cpr and early defibrillation can: * James meredith early life

James meredith early life James is going through puberty quite early

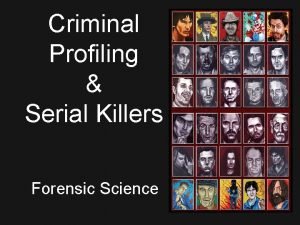

James is going through puberty quite early Clay lawson and russell odom

Clay lawson and russell odom James clayton lawson

James clayton lawson Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới ưu thế lai là gì

ưu thế lai là gì Hệ hô hấp

Hệ hô hấp Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Cái miệng bé xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi

Cái miệng bé xinh thế chỉ nói điều hay thôi Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân Tư thế ngồi viết

Tư thế ngồi viết Thế nào là giọng cùng tên

Thế nào là giọng cùng tên Chó sói

Chó sói Thẻ vin

Thẻ vin Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu

Sự nuôi và dạy con của hươu Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu

Từ ngữ thể hiện lòng nhân hậu