Mental Health and Older Adults Vineeth John MD

- Slides: 32

Mental Health and Older Adults Vineeth John, MD and Kathleen Pace Murphy, Ph. D, GNP The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth)

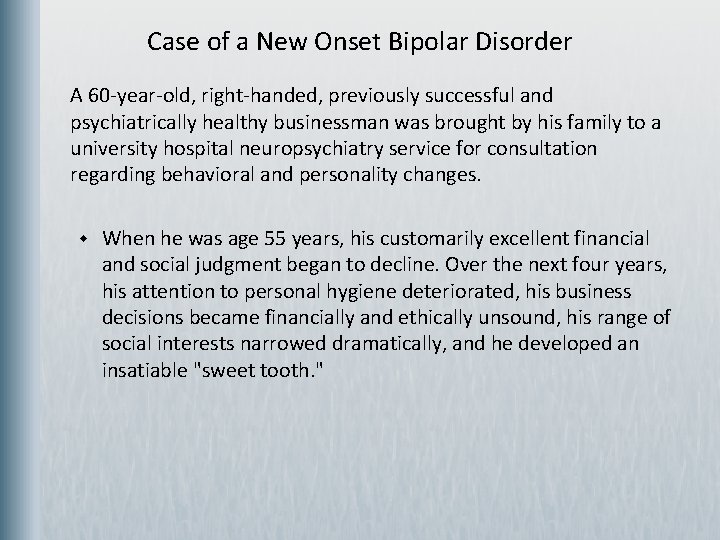

Case of a New Onset Bipolar Disorder A 60 -year-old, right-handed, previously successful and psychiatrically healthy businessman was brought by his family to a university hospital neuropsychiatry service for consultation regarding behavioral and personality changes. w When he was age 55 years, his customarily excellent financial and social judgment began to decline. Over the next four years, his attention to personal hygiene deteriorated, his business decisions became financially and ethically unsound, his range of social interests narrowed dramatically, and he developed an insatiable "sweet tooth. "

Case of a New Onset Bipolar Disorder A 60 -year-old, right-handed, previously successful and psychiatrically healthy businessman was brought by his family to a university hospital neuropsychiatry service for consultation regarding behavioral and personality changes. w In the year preceding the consultation, his ability to maintain sleep diminished, he began spending money recklessly and impulsively and became unable to appreciate the feelings and concerns of others, and his speech and behavior took on a perseverative quality. Concurrently, he developed unprovoked, brief, frequent, and excessively intense episodes of tearfulness and laughing. These episodes lasted minutes at most, after which he would return to his usual euthymic emotional state.

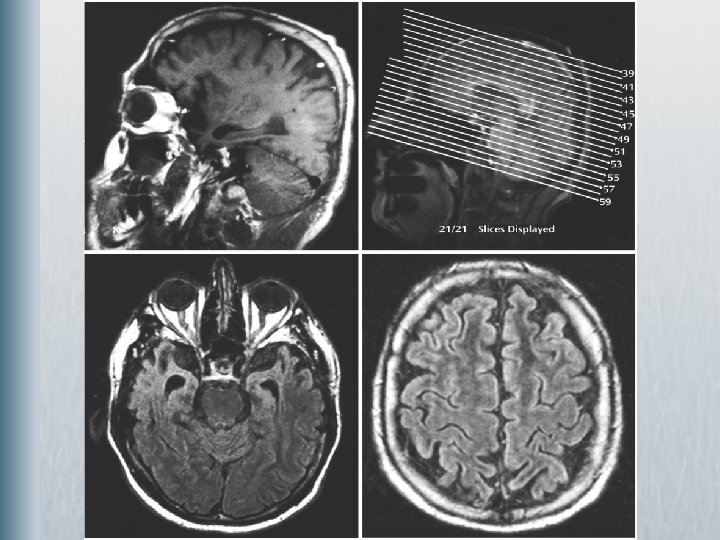

Case of a New Onset Bipolar Disorder A 60 -year-old, right-handed, previously successful and psychiatrically healthy businessman was brought by his family to a university hospital neuropsychiatry service for consultation regarding behavioral and personality changes. w One month before the neuropsychiatric consultation, he had received a diagnosis of late-onset bipolar disorder and had begun treatment with lithium carbonate. When his serum lithium level reached therapeutic range, his cognitive, behavioral and motor function declined precipitously, prompting the consultation for a second diagnostic opinion. Is this patient’s presentation consistent with late onset bipolar disorder? What assessments are needed to clarify his diagnosis?

Late Onset Psychosis w w Psychosis of Alzheimer's disease Late onset Schizophrenia Late life delusional disorder Psychotic disorders secondary to General Medical Conditions

Psychosis in AD w w w Increased risk of agitation Increase in aggression Poor self care Disruptive behavior Wandering High rate of institutionalization w w w Between 30 to 50 % of AD patients have psychotic symptoms Psychotic symptoms are more prevalent as the disease progresses but are more common in the middle stages. Visual hallucinations are more common than auditory hallucinations.

Common Themes of Delusions in AD w w Stealing Stranger in the house Spying Impersonating the spouse or loved one Photo by Morgue. File user ‘JKD_DE”. Morguefile. com

Psychosis in Other Dementias w w w Dementia of Lewy bodies – VH and Delusions Parkinson's Disease - Delusions and Hallucinations Vascular Dementia Treatment of Psychotic Symptoms in Dementia w w Low dose antipsychotics are the norm. Careful balancing of the risks and benefits need to be performed.

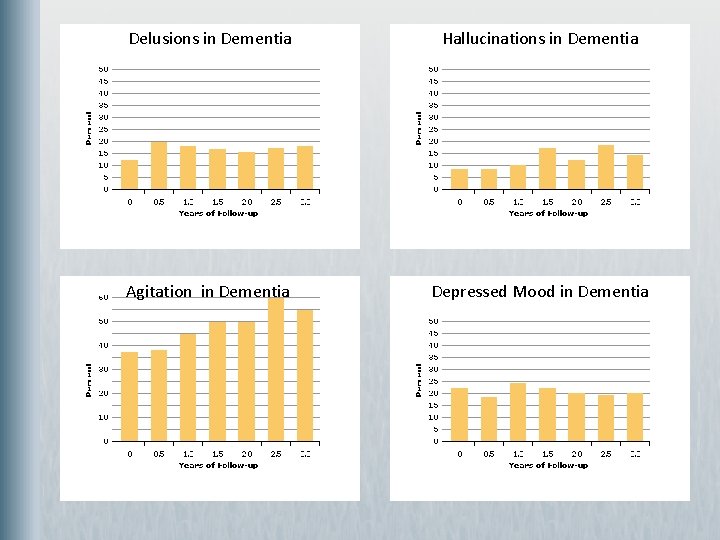

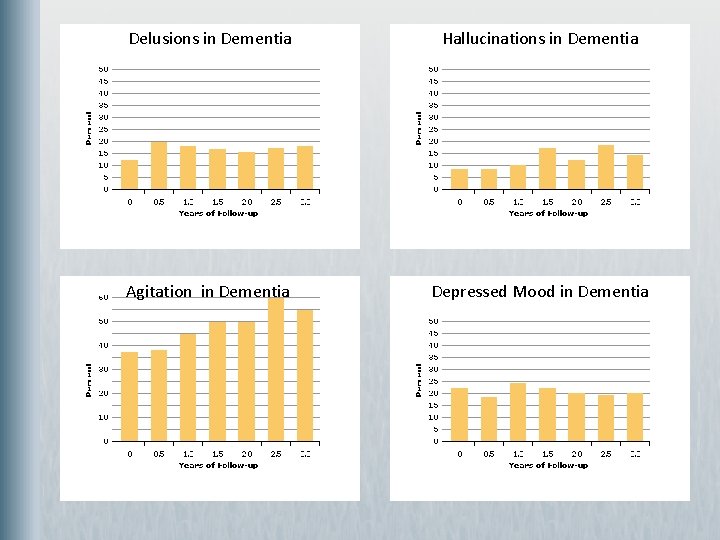

Delusions in Dementia Hallucinations in Dementia Agitation in Dementia Depressed Mood in Dementia

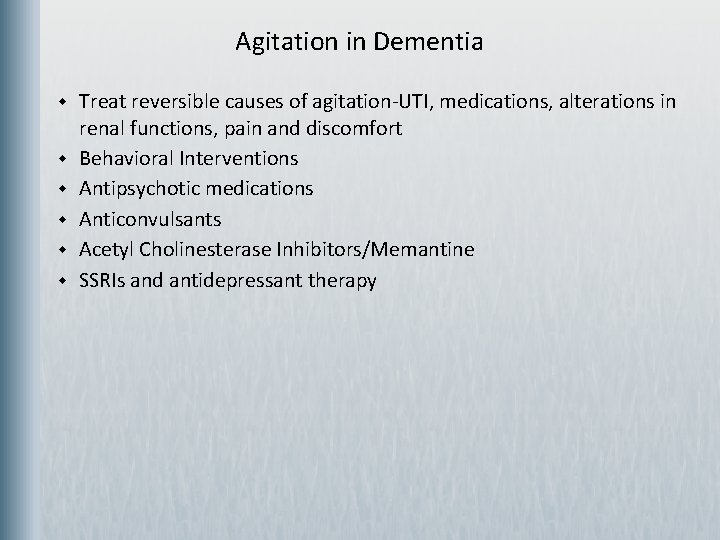

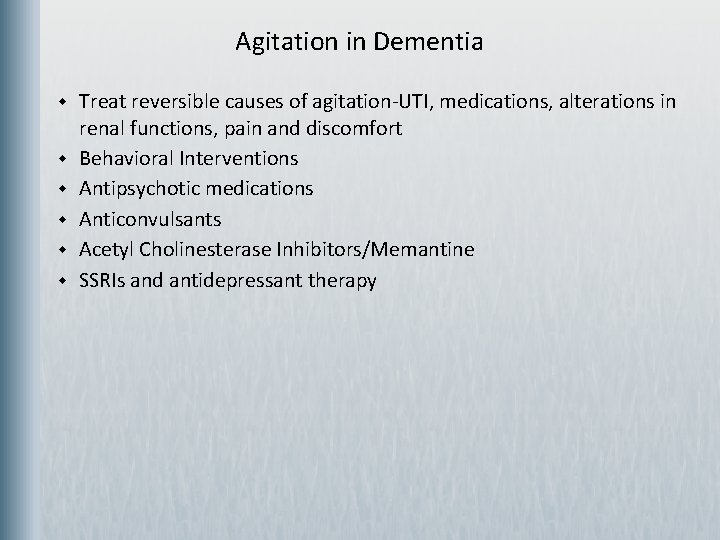

Agitation in Dementia w w w Treat reversible causes of agitation-UTI, medications, alterations in renal functions, pain and discomfort Behavioral Interventions Antipsychotic medications Anticonvulsants Acetyl Cholinesterase Inhibitors/Memantine SSRIs and antidepressant therapy

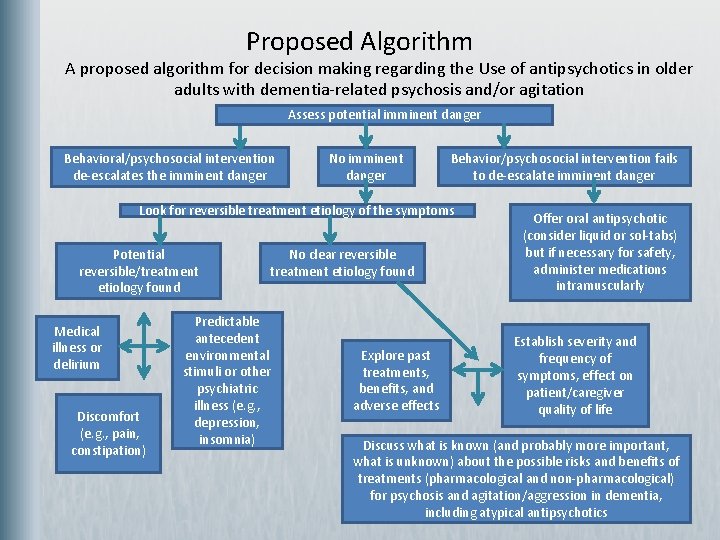

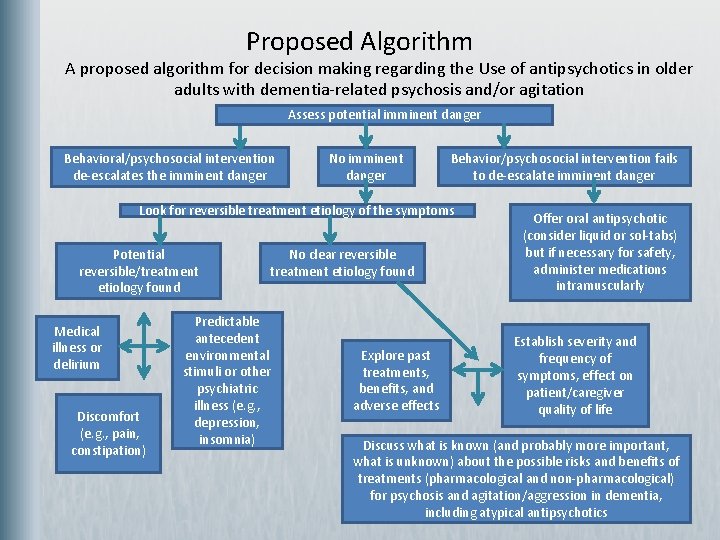

Proposed Algorithm A proposed algorithm for decision making regarding the Use of antipsychotics in older adults with dementia-related psychosis and/or agitation Assess potential imminent danger Behavioral/psychosocial intervention de-escalates the imminent danger No imminent danger Behavior/psychosocial intervention fails to de-escalate imminent danger Look for reversible treatment etiology of the symptoms Potential reversible/treatment etiology found Medical illness or delirium Discomfort (e. g. , pain, constipation) No clear reversible treatment etiology found Predictable antecedent environmental stimuli or other psychiatric illness (e. g. , depression, insomnia) Explore past treatments, benefits, and adverse effects Offer oral antipsychotic (consider liquid or sol-tabs) but if necessary for safety, administer medications intramuscularly Establish severity and frequency of symptoms, effect on patient/caregiver quality of life Discuss what is known (and probably more important, what is unknown) about the possible risks and benefits of treatments (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) for psychosis and agitation/aggression in dementia, including atypical antipsychotics

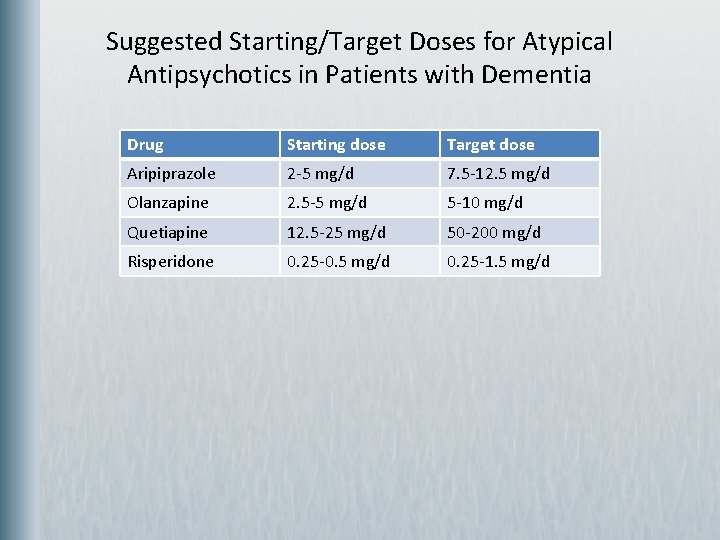

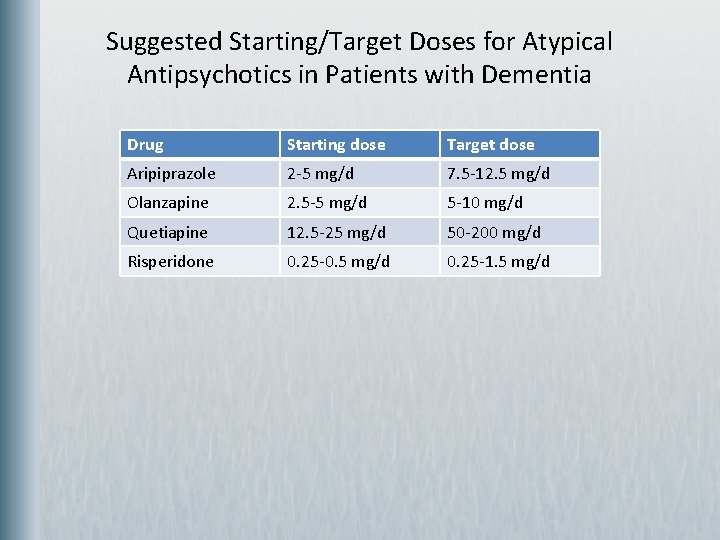

Suggested Starting/Target Doses for Atypical Antipsychotics in Patients with Dementia Drug Starting dose Target dose Aripiprazole 2 -5 mg/d 7. 5 -12. 5 mg/d Olanzapine 2. 5 -5 mg/d 5 -10 mg/d Quetiapine 12. 5 -25 mg/d 50 -200 mg/d Risperidone 0. 25 -0. 5 mg/d 0. 25 -1. 5 mg/d

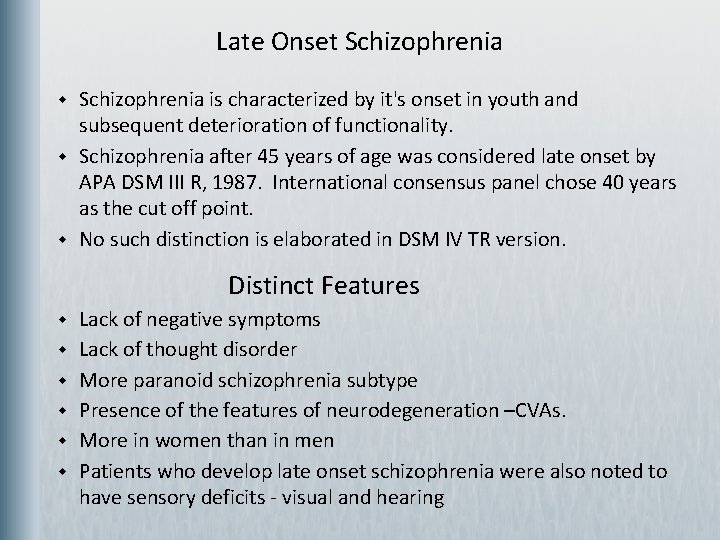

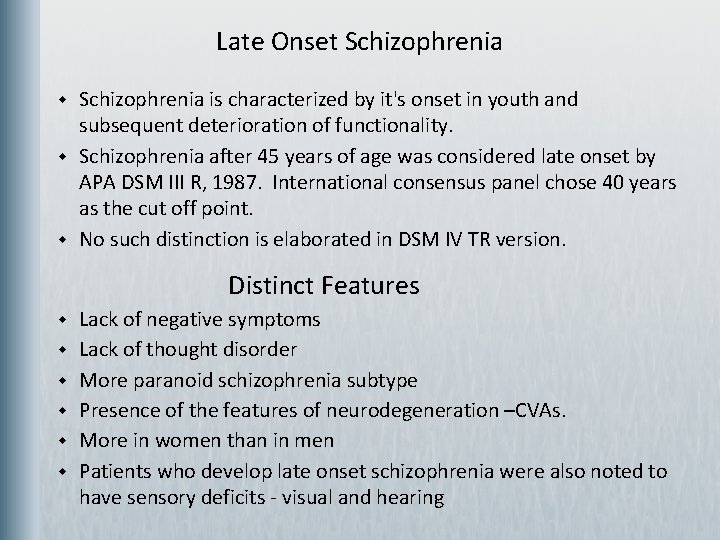

Late Onset Schizophrenia w w w Schizophrenia is characterized by it's onset in youth and subsequent deterioration of functionality. Schizophrenia after 45 years of age was considered late onset by APA DSM III R, 1987. International consensus panel chose 40 years as the cut off point. No such distinction is elaborated in DSM IV TR version. Distinct Features w w w Lack of negative symptoms Lack of thought disorder More paranoid schizophrenia subtype Presence of the features of neurodegeneration –CVAs. More in women than in men Patients who develop late onset schizophrenia were also noted to have sensory deficits - visual and hearing

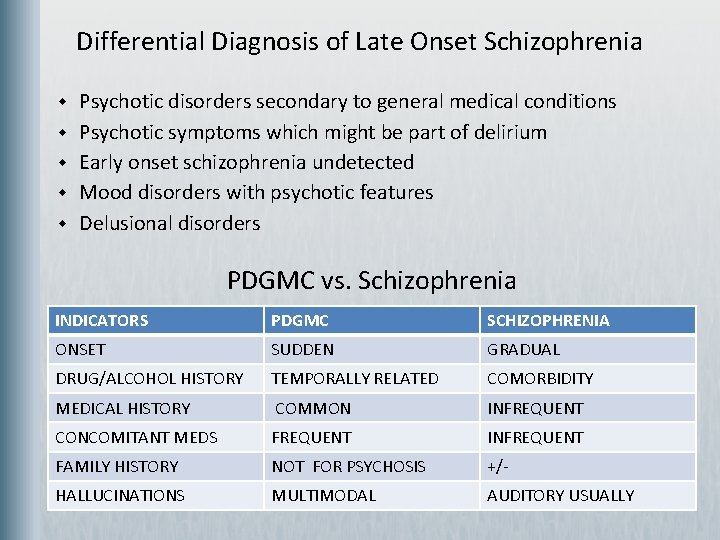

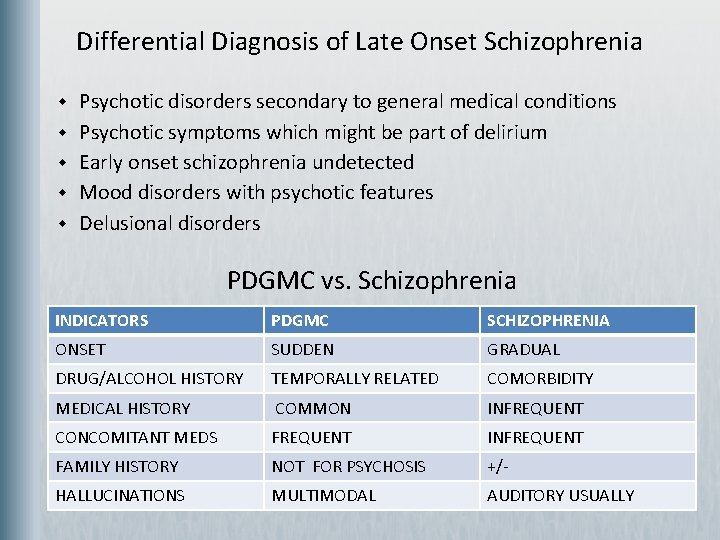

Differential Diagnosis of Late Onset Schizophrenia w w w Psychotic disorders secondary to general medical conditions Psychotic symptoms which might be part of delirium Early onset schizophrenia undetected Mood disorders with psychotic features Delusional disorders PDGMC vs. Schizophrenia INDICATORS PDGMC SCHIZOPHRENIA ONSET SUDDEN GRADUAL DRUG/ALCOHOL HISTORY TEMPORALLY RELATED COMORBIDITY MEDICAL HISTORY COMMON INFREQUENT CONCOMITANT MEDS FREQUENT INFREQUENT FAMILY HISTORY NOT FOR PSYCHOSIS +/- HALLUCINATIONS MULTIMODAL AUDITORY USUALLY

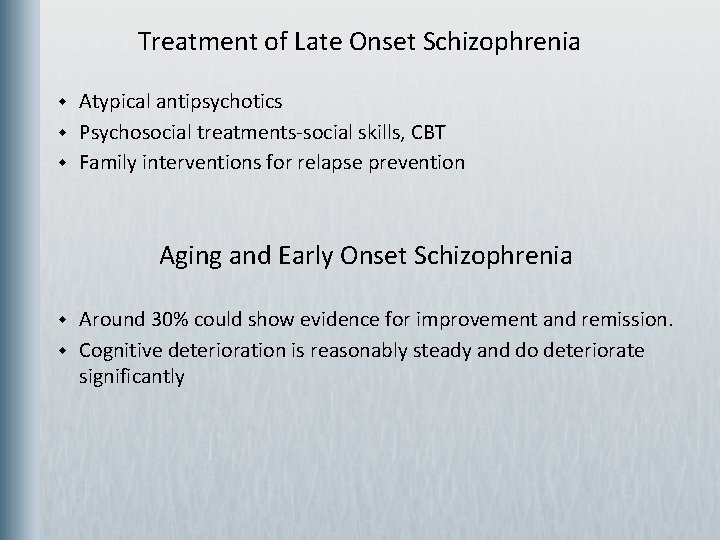

Treatment of Late Onset Schizophrenia w w w Atypical antipsychotics Psychosocial treatments-social skills, CBT Family interventions for relapse prevention Aging and Early Onset Schizophrenia w w Around 30% could show evidence for improvement and remission. Cognitive deterioration is reasonably steady and do deteriorate significantly

John Nash, Jr. — in his own words “But after my return to the dream-like delusional hypotheses in the later 60's I became a person of delusionally influenced thinking but of relatively moderate behavior and thus tended to avoid hospitalization and the direct attention of psychiatrists. Thus further time passed. Then gradually I began to intellectually reject some of the delusional influenced lines of thinking which had been characteristic of my orientation. This began, most recognizably, with the rejection of politically-oriented thinking as essentially a hopeless waste of intellectual effort. ”

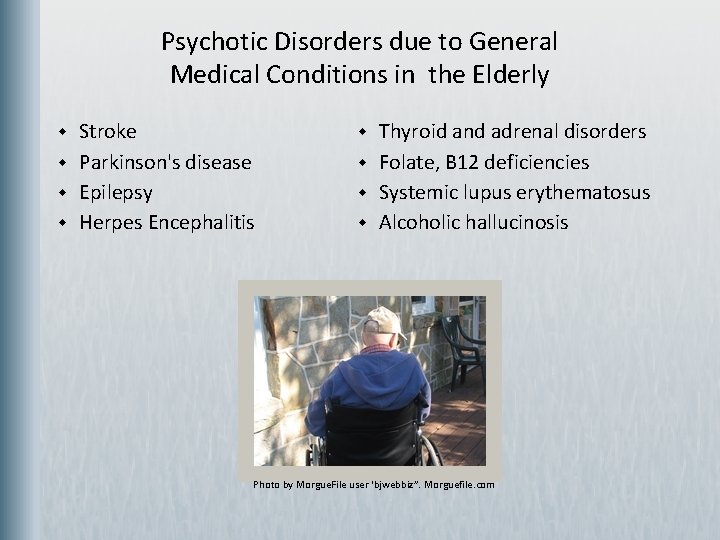

Psychotic Disorders due to General Medical Conditions in the Elderly w w Stroke Parkinson's disease Epilepsy Herpes Encephalitis w w Thyroid and adrenal disorders Folate, B 12 deficiencies Systemic lupus erythematosus Alcoholic hallucinosis Photo by Morgue. File user ‘bjwebbiz”. Morguefile. com

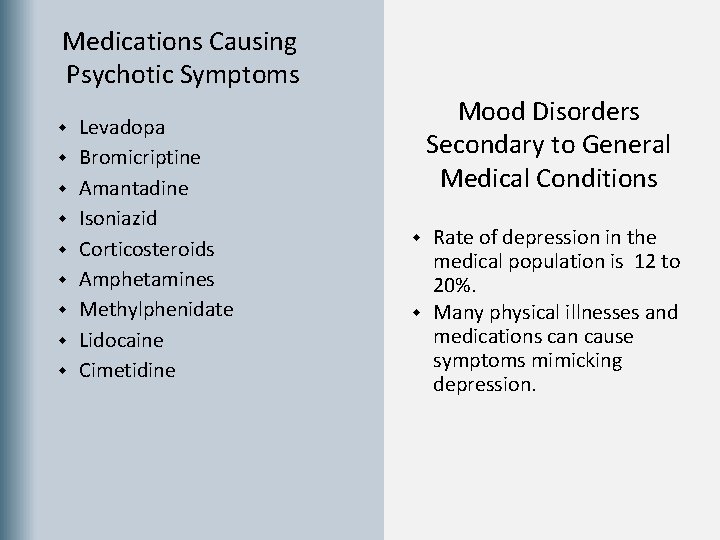

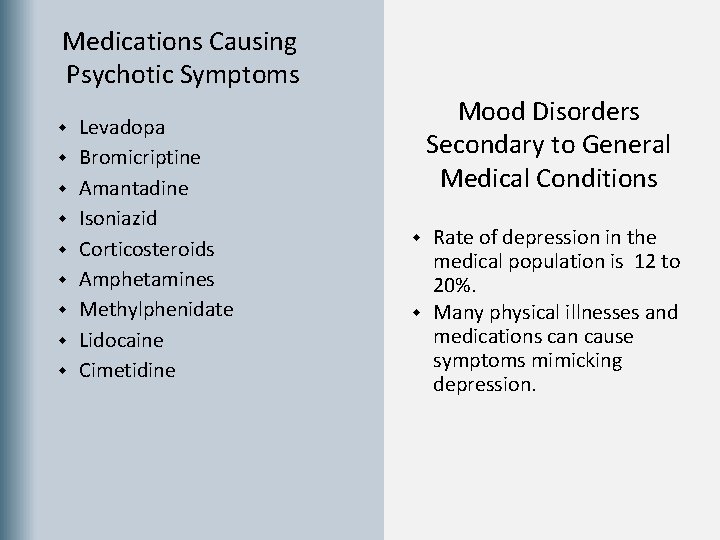

Medications Causing Psychotic Symptoms w w w w w Levadopa Bromicriptine Amantadine Isoniazid Corticosteroids Amphetamines Methylphenidate Lidocaine Cimetidine Mood Disorders Secondary to General Medical Conditions w w Rate of depression in the medical population is 12 to 20%. Many physical illnesses and medications can cause symptoms mimicking depression.

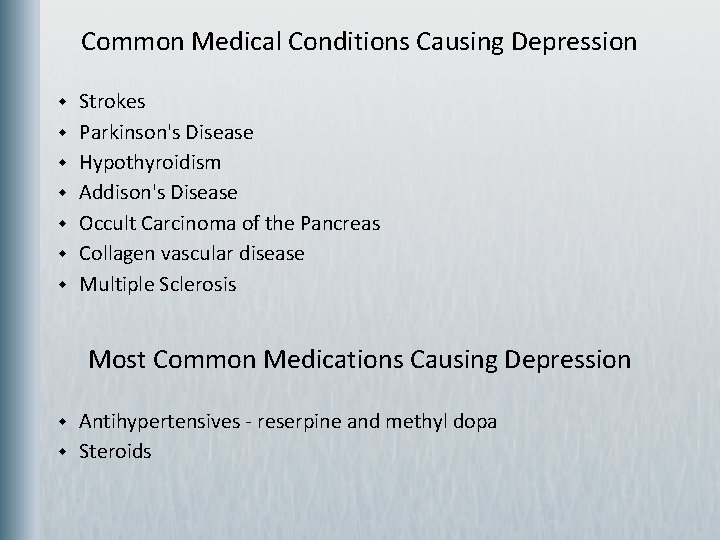

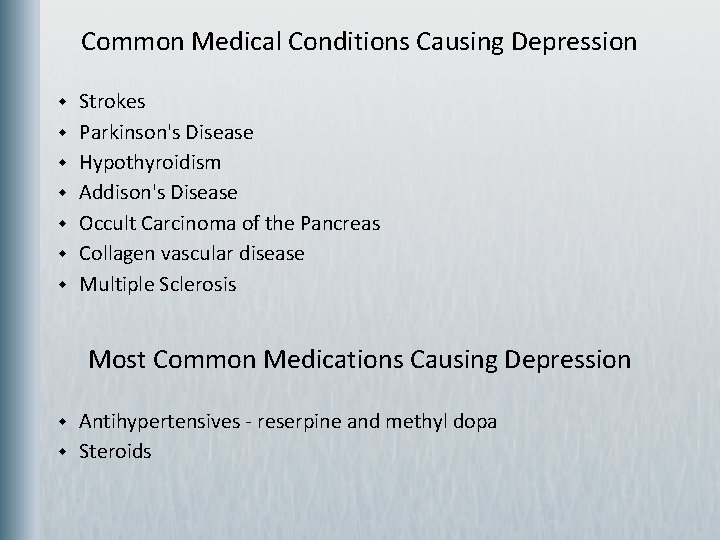

Common Medical Conditions Causing Depression w w w w Strokes Parkinson's Disease Hypothyroidism Addison's Disease Occult Carcinoma of the Pancreas Collagen vascular disease Multiple Sclerosis Most Common Medications Causing Depression w w Antihypertensives - reserpine and methyl dopa Steroids

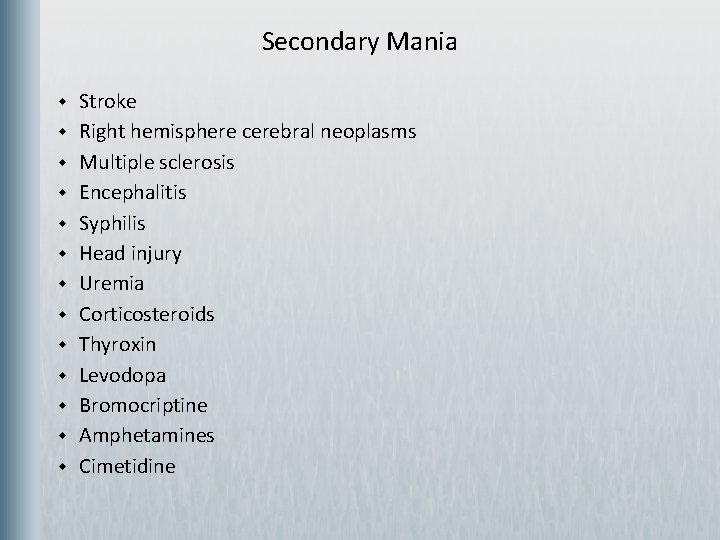

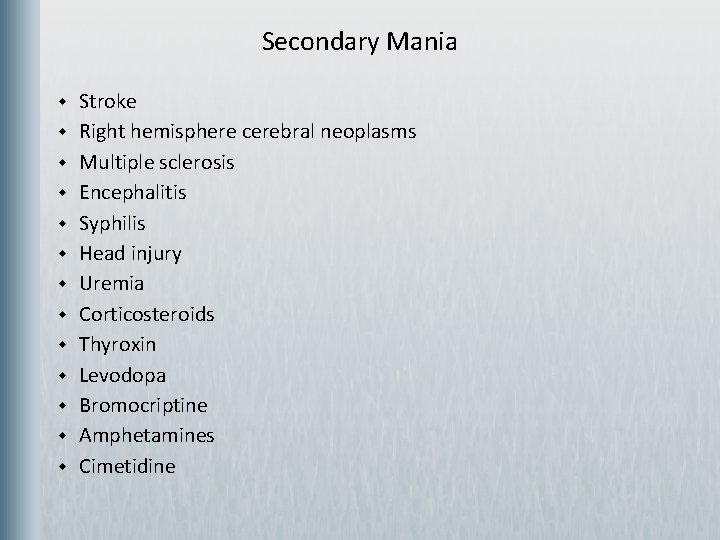

Secondary Mania w w w w Stroke Right hemisphere cerebral neoplasms Multiple sclerosis Encephalitis Syphilis Head injury Uremia Corticosteroids Thyroxin Levodopa Bromocriptine Amphetamines Cimetidine

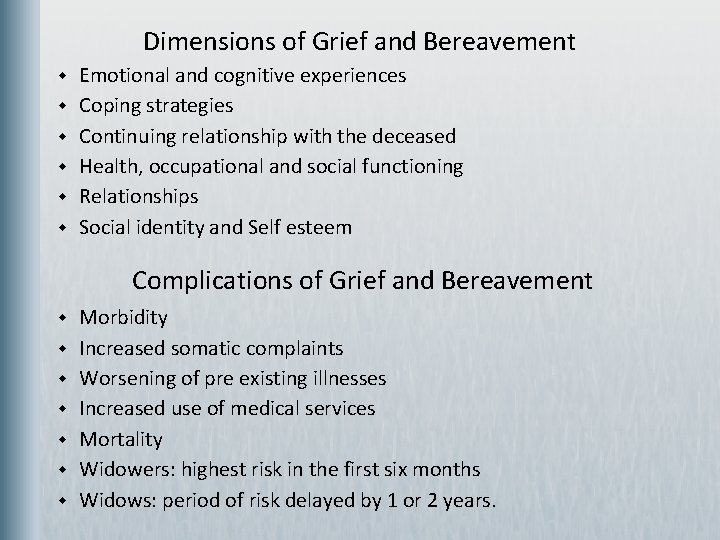

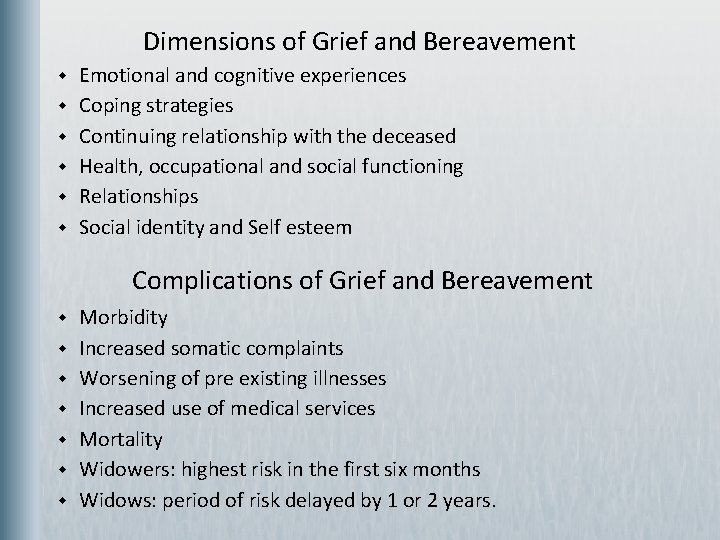

Dimensions of Grief and Bereavement w w w Emotional and cognitive experiences Coping strategies Continuing relationship with the deceased Health, occupational and social functioning Relationships Social identity and Self esteem Complications of Grief and Bereavement w w w w Morbidity Increased somatic complaints Worsening of pre existing illnesses Increased use of medical services Mortality Widowers: highest risk in the first six months Widows: period of risk delayed by 1 or 2 years.

Psychiatric Complications of Grief w w Substance use Anxiety symptoms PTSD Depression Photo by Stockxchng user ‘Ginnt. Lynny”. www. sxc. hu

Risk Factors Leading to Depression in the Grieving Process w w w w Unnatural sudden unexpected death Preexisting mood disorder Early, intense depressive reaction after the loss Poor physical health Increased alcohol consumption Family history of major depression Poor social support system Geriatric Depression w w w Prevalence of geriatric depression is much higher in medical settings than in the community — 30%. 50% of nursing home residents are at risk to develop depression. Cognitive impairment is an expected complication in elderly patients who develop depression

Under Diagnosis of Depression in the Elderly w w w Under reporting of symptoms More focus on physical symptoms More anhedonia than sadness Subsyndromal depression not meeting criteria Medical illness detection overshadow the diagnosis of depression Photo by Daniel Bayona. Morguefile. com

Reasons for Missed Diagnosis of Depression in Elderly Patients • Elderly patients under-report symptoms of depression (Lyness, 1995) • Elderly patients may not acknowledge being sad, down or depressed (Gallo, 1997) • Atypical presentations of depression frequently occur in old age (eg, somatic disorders, pseudodementia , behavioural disturbances) (Brodaty, 1993) • Elderly patients and clinicians misattribute symptoms to comorbid physical illnesses (Booth, 1998; Knauper, 1994) • The acceptance of depression as a “normal” psychological reaction to physical illness, life in a nursing home, widowhood or the aging process (Fawcett, 1972) • General practitioners may lack confidence in diagnosing depression in elderly patients, especially when the patient may not talk about feeling depressed, sad or irritable (Shah, 1997; Bowers, 1990) • Current diagnostic categories of depression do not adequately describe many depressed older people, particularly those with minor depressions that are most common in primary care (Beekman, 1999; Callahan 1996) • Education of general practitioners may focus too much on the types of depression seen in specialist practice (major depression), and not enough on minor depression

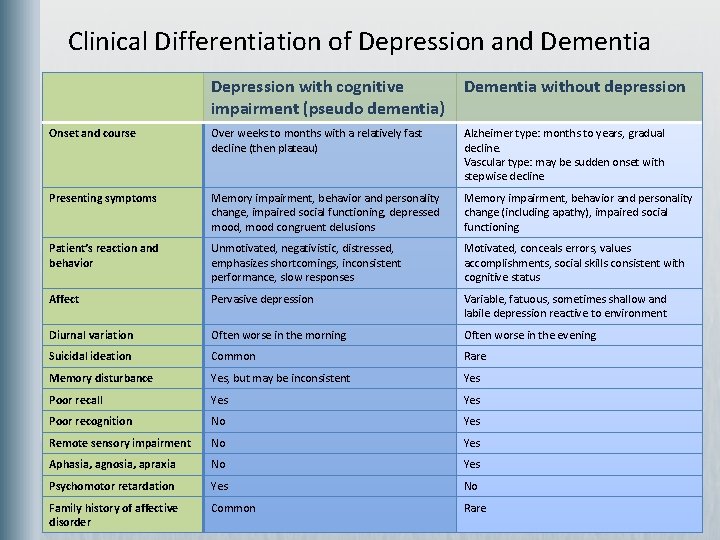

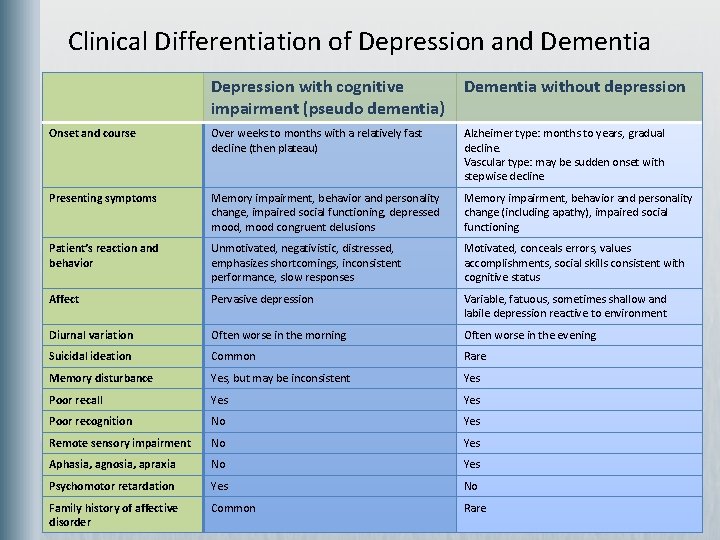

Clinical Differentiation of Depression and Dementia Depression with cognitive impairment (pseudo dementia) Dementia without depression Onset and course Over weeks to months with a relatively fast decline (then plateau) Alzheimer type: months to years, gradual decline. Vascular type: may be sudden onset with stepwise decline Presenting symptoms Memory impairment, behavior and personality change, impaired social functioning, depressed mood, mood congruent delusions Memory impairment, behavior and personality change (including apathy), impaired social functioning Patient’s reaction and behavior Unmotivated, negativistic, distressed, emphasizes shortcomings, inconsistent performance, slow responses Motivated, conceals errors, values accomplishments, social skills consistent with cognitive status Affect Pervasive depression Variable, fatuous, sometimes shallow and labile depression reactive to environment Diurnal variation Often worse in the morning Often worse in the evening Suicidal ideation Common Rare Memory disturbance Yes, but may be inconsistent Yes Poor recall Yes Poor recognition No Yes Remote sensory impairment No Yes Aphasia, agnosia, apraxia No Yes Psychomotor retardation Yes No Family history of affective disorder Common Rare

Co-morbidity and Complications of Late Life Depression worsens outcomes and prognosis of medical illnesses w Depression lengthens hospital stay w Depression increases perception of ill health w Depression increases economic burden on the health care system w Depression worsens disability w Depression also results in increased suicide risk —White men over the age of 65, has the highest suicide rate w

Risk Factors for Suicide in the Elderly w w w Loneliness and poor social support Presence of psychiatric disorder Presence of fire arm Impaired ability with IADLs Medical co-morbidity Photo by Morgue. File user BBoomer. In. Denial. Morguefile. com

Treatment Options for Depression in the Elderly w w w w SSRIs TCAs MAOIs Bupropion Mirtazapine Augmenting agents ECT Psychotherapy Photo by Ronnie Bergeron. Morguefile. com

References • Devan and DP, Jacobs DM, Tang MX, et al. The course of psychopathologic features in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997; 54: 257– 263 • Meeks, TW and Jeste, DV, Current Psychiatry, 2008 • Meeks, TW and Jeste, DV, Current Psychiatry, 2009 Photographs use for the cover are allowed by the Morgue. File free photo agreement and the Royalty Free usage agreement at Stock. xchng. They appear on the cover in this order: Wallyir at morguefile. com/archive/display/221205 Mokra at www. sxc. hu/photo/572286 Clarita at morguefile. com/archive/display/33743

The Training Excellence in Aging Studies (TEXAS) program promotes geriatric training from medical school through the practicing physician level. This project is funded by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation to the division of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine within the department of Internal Medicine at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) TEXAS would also like to recognize the following for contributions: Houston Geriatric Education Center Harris County Hospital District Memorial Hermann Foundation The TEXAS Advisory Board Othello "Bud" and Newlyn Hare UTHealth Medical School Office of the Dean UTHealth Medical School Office of Educational Programs UTHealth School of Nursing UTHealth Consortium on Aging

Mental health and older adults

Mental health and older adults Mental health and older adults

Mental health and older adults Older adults mental health

Older adults mental health Vineeth john md

Vineeth john md Vineeth john md

Vineeth john md Life is older older than the trees

Life is older older than the trees Altered cognition in older adults is commonly attributed to

Altered cognition in older adults is commonly attributed to Physical examination conclusion

Physical examination conclusion Older adults

Older adults Covids older adults

Covids older adults Dynamic stretching for older adults

Dynamic stretching for older adults Cse 340 principles of programming languages

Cse 340 principles of programming languages Chapter 20 mental health and mental illness

Chapter 20 mental health and mental illness Mental health jeopardy questions and answers

Mental health jeopardy questions and answers Shorter taller older tall

Shorter taller older tall Dq98 form

Dq98 form Downsizing and divesting older business

Downsizing and divesting older business Module 11 studying the brain and older brain structures

Module 11 studying the brain and older brain structures Chapter 3 lesson 3 expressing emotions in healthful ways

Chapter 3 lesson 3 expressing emotions in healthful ways Lemhwa report to congress

Lemhwa report to congress Mental health and citizenship

Mental health and citizenship Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health

Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health Chapter 21 mental health diseases and disorders

Chapter 21 mental health diseases and disorders Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health answers

Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health answers Psychology, mental health and distress

Psychology, mental health and distress Mental health policy, plans and programmes michelle funk

Mental health policy, plans and programmes michelle funk Chapter 5 lesson 3 suicide prevention answer key

Chapter 5 lesson 3 suicide prevention answer key Chapter 5 lesson 4 getting help

Chapter 5 lesson 4 getting help Chapter 3 mental and emotional health answer key

Chapter 3 mental and emotional health answer key Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health

Chapter 3 achieving mental and emotional health Emotional health defintion

Emotional health defintion Achieving mental and emotional health

Achieving mental and emotional health Photoshop mind map

Photoshop mind map