LOGIC FATALISM AND FUTURE CONTINGENTS 1 Linear time

- Slides: 28

LOGIC FATALISM AND FUTURE CONTINGENTS 1

Linear time • We assume that time is linear. 2

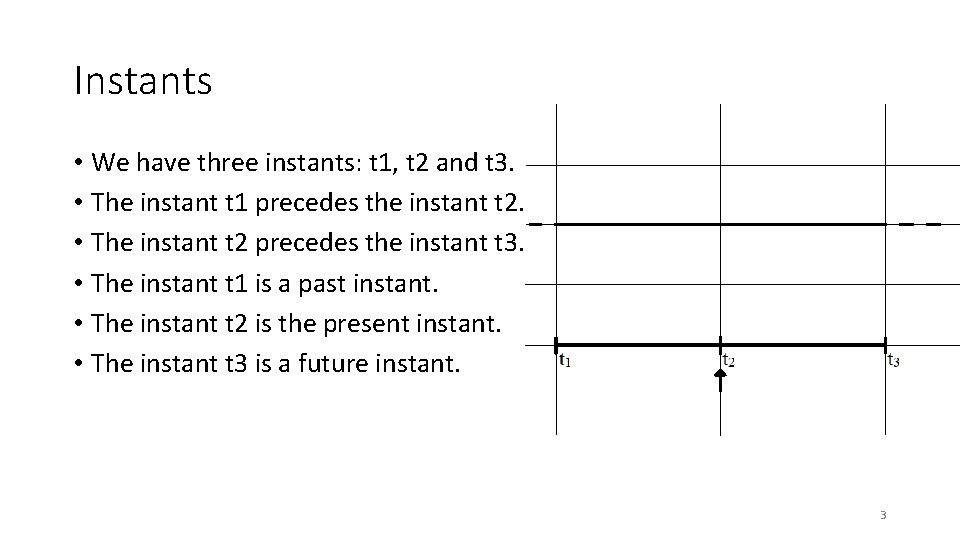

Instants • We have three instants: t 1, t 2 and t 3. • The instant t 1 precedes the instant t 2. • The instant t 2 precedes the instant t 3. • The instant t 1 is a past instant. • The instant t 2 is the present instant. • The instant t 3 is a future instant. 3

Presentism • Whatever exists is present. • Whatever exists is in the instant t 2. 4

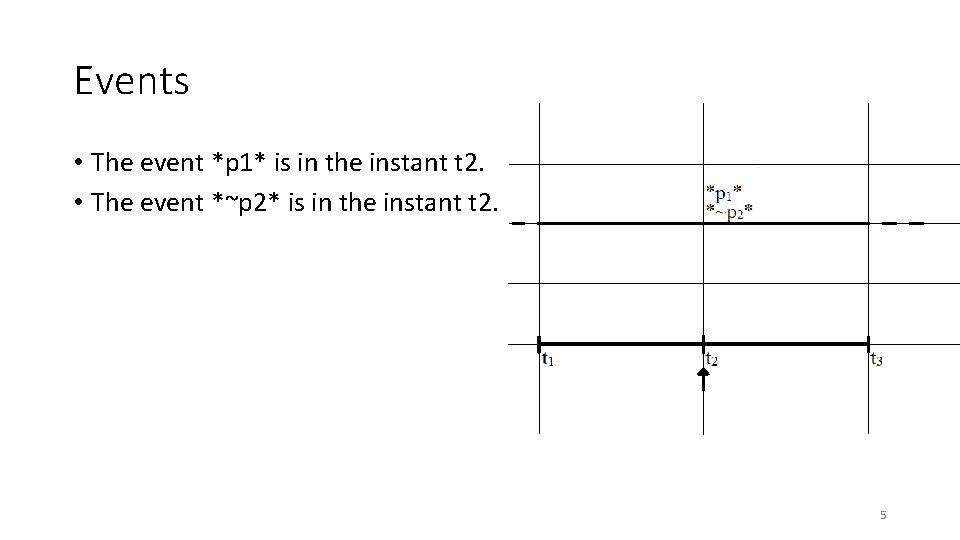

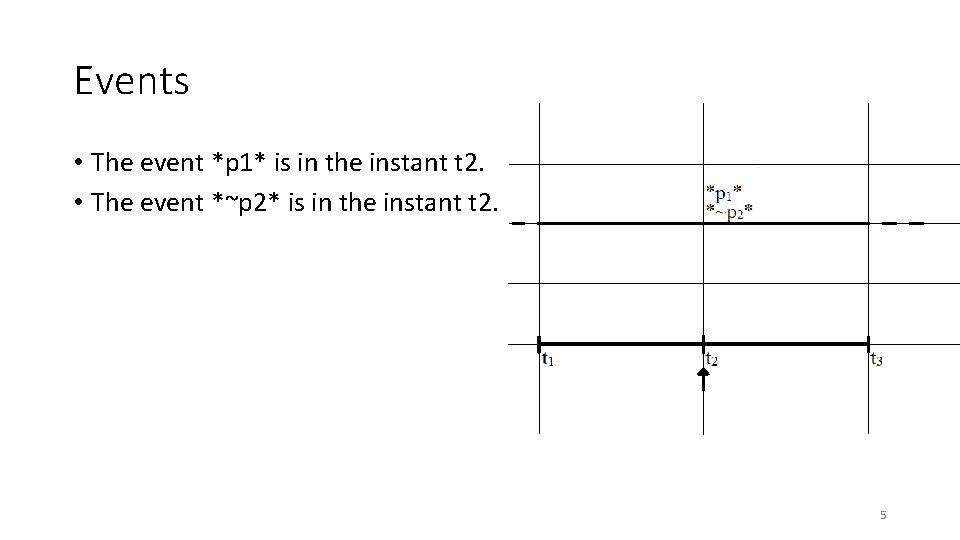

Events • The event *p 1* is in the instant t 2. • The event *~p 2* is in the instant t 2. 5

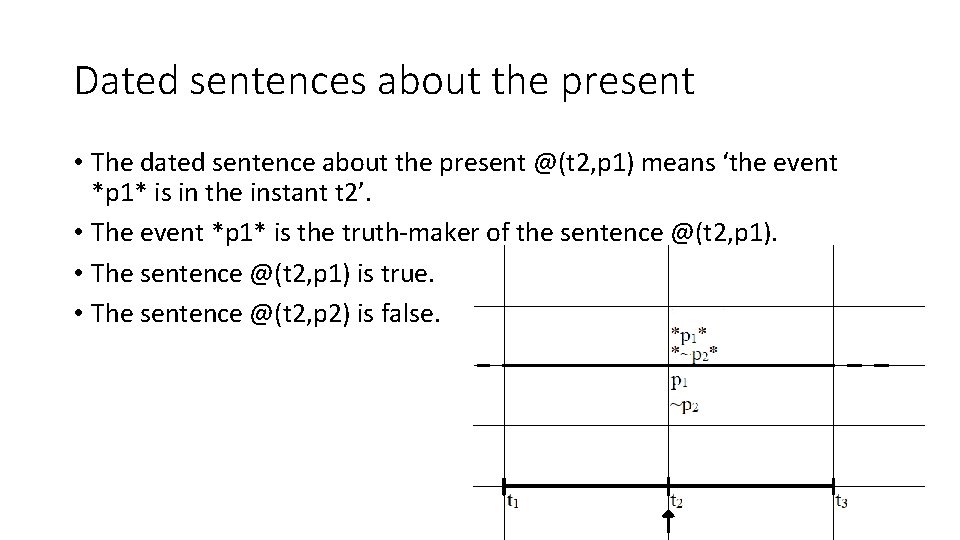

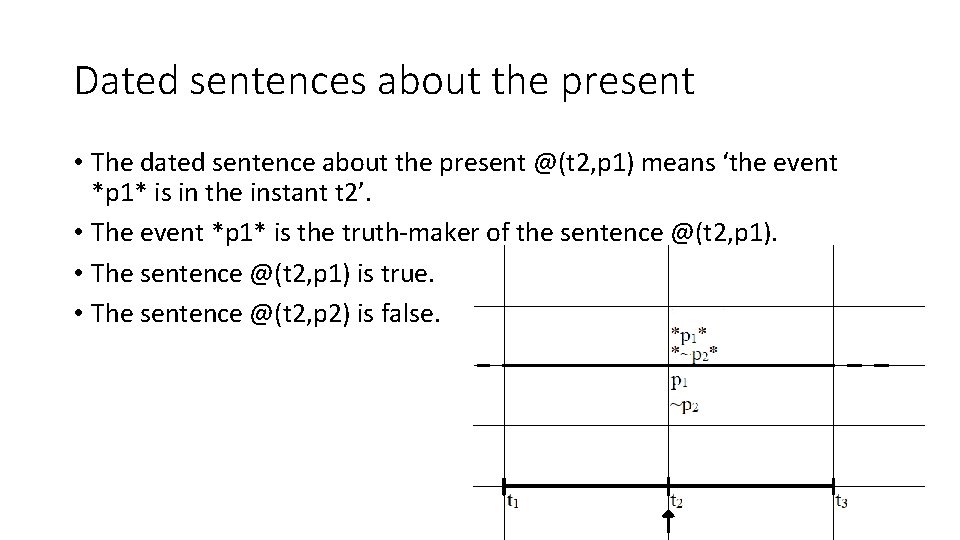

Dated sentences about the present • The dated sentence about the present @(t 2, p 1) means ‘the event *p 1* is in the instant t 2’. • The event *p 1* is the truth-maker of the sentence @(t 2, p 1). • The sentence @(t 2, p 1) is true. • The sentence @(t 2, p 2) is false. 6

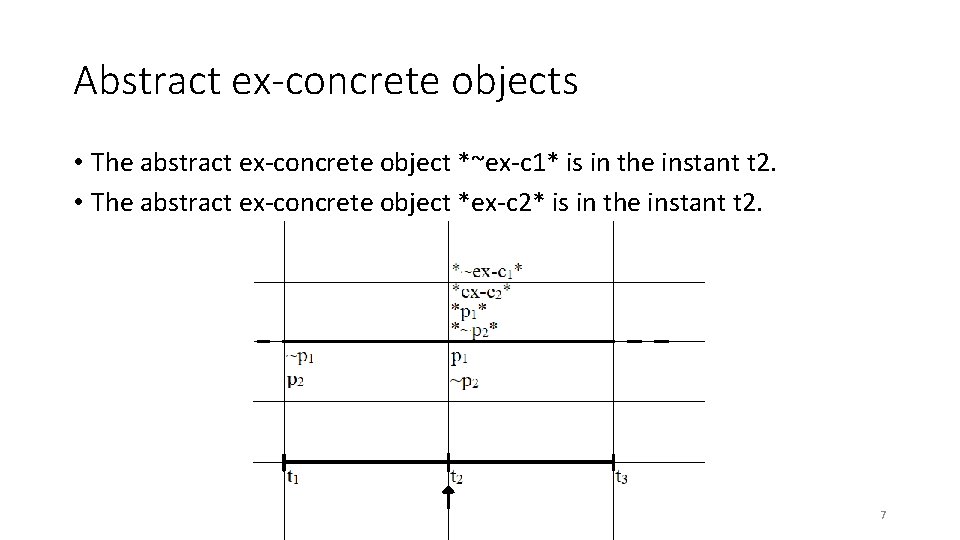

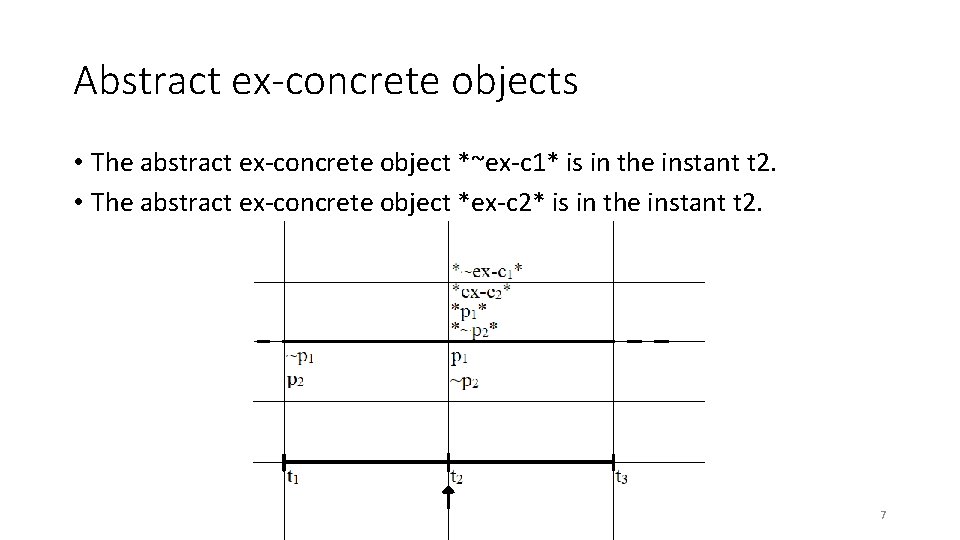

Abstract ex-concrete objects • The abstract ex-concrete object *~ex-c 1* is in the instant t 2. • The abstract ex-concrete object *ex-c 2* is in the instant t 2. 7

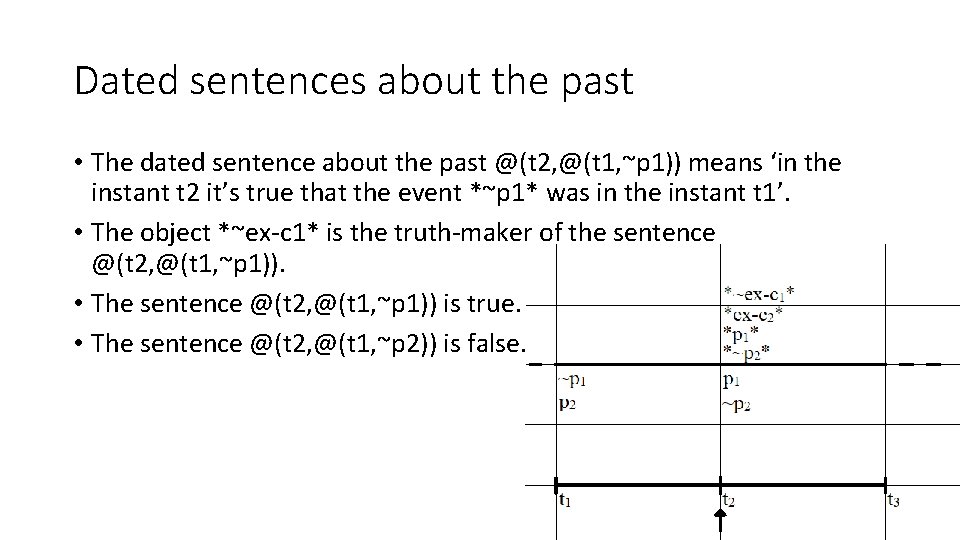

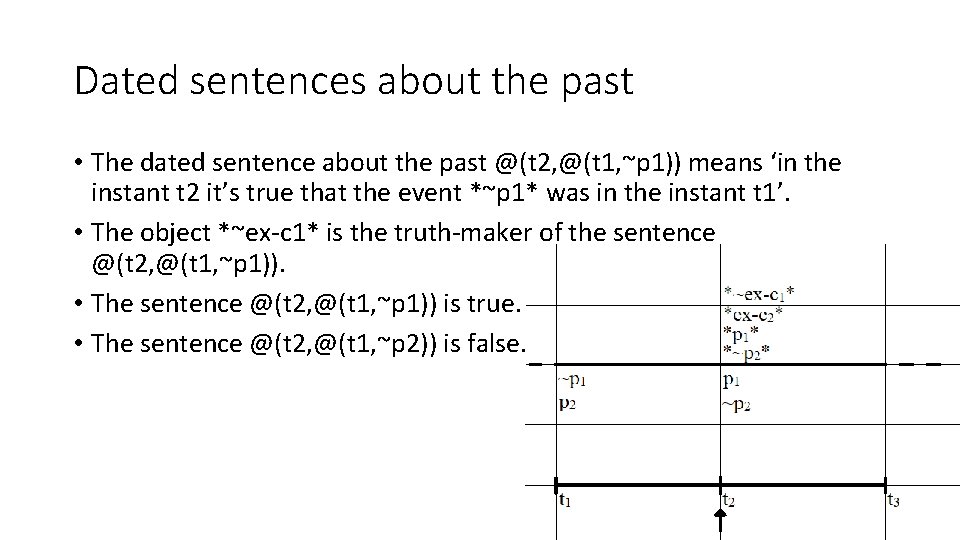

Dated sentences about the past • The dated sentence about the past @(t 2, @(t 1, ~p 1)) means ‘in the instant t 2 it’s true that the event *~p 1* was in the instant t 1’. • The object *~ex-c 1* is the truth-maker of the sentence @(t 2, @(t 1, ~p 1)). • The sentence @(t 2, @(t 1, ~p 1)) is true. • The sentence @(t 2, @(t 1, ~p 2)) is false. 8

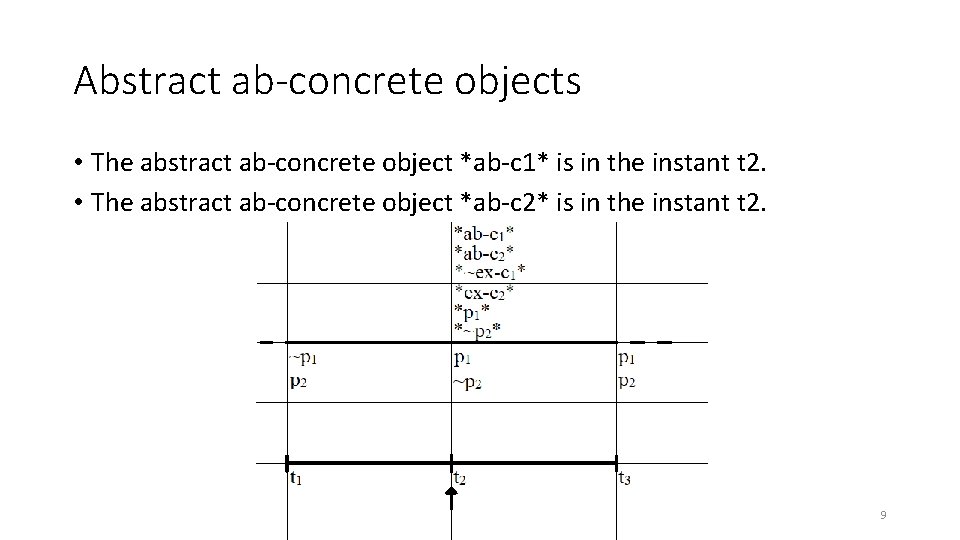

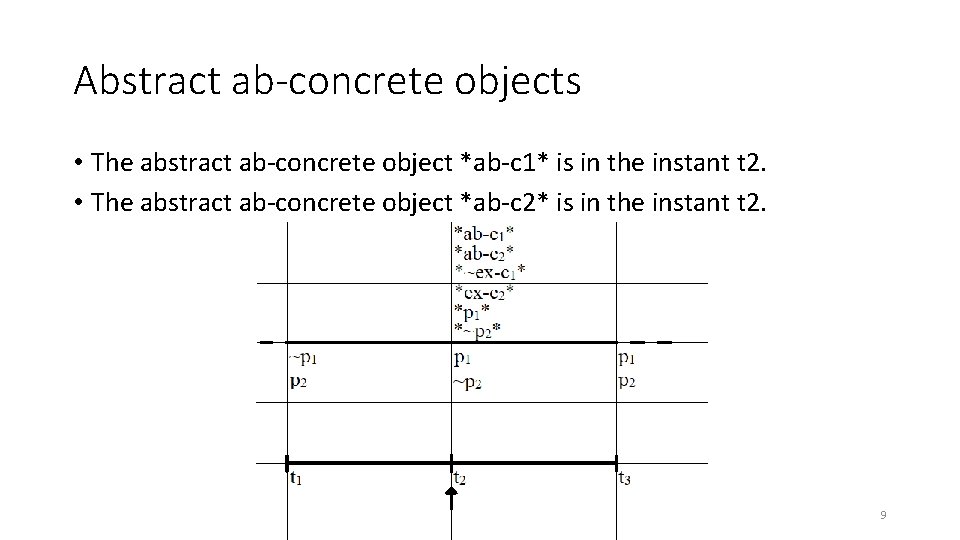

Abstract ab-concrete objects • The abstract ab-concrete object *ab-c 1* is in the instant t 2. • The abstract ab-concrete object *ab-c 2* is in the instant t 2. 9

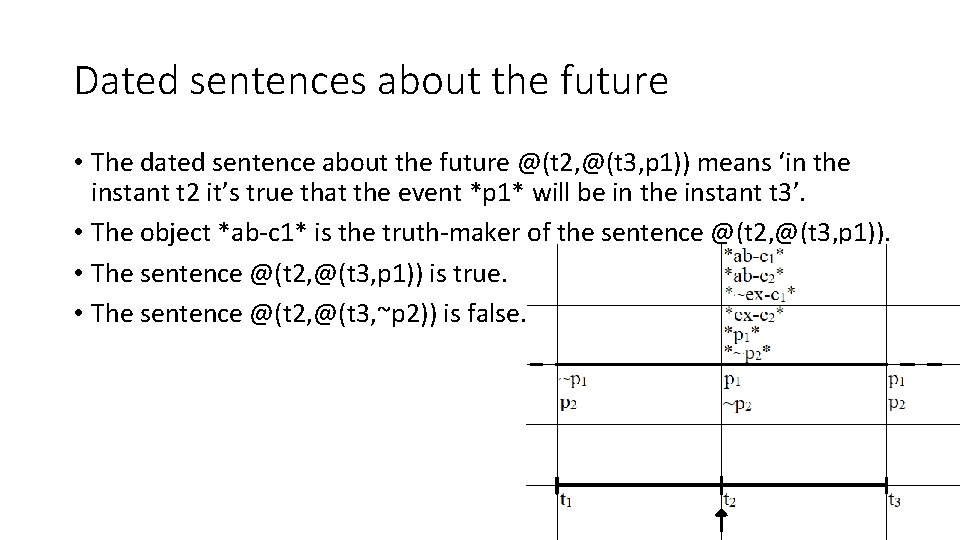

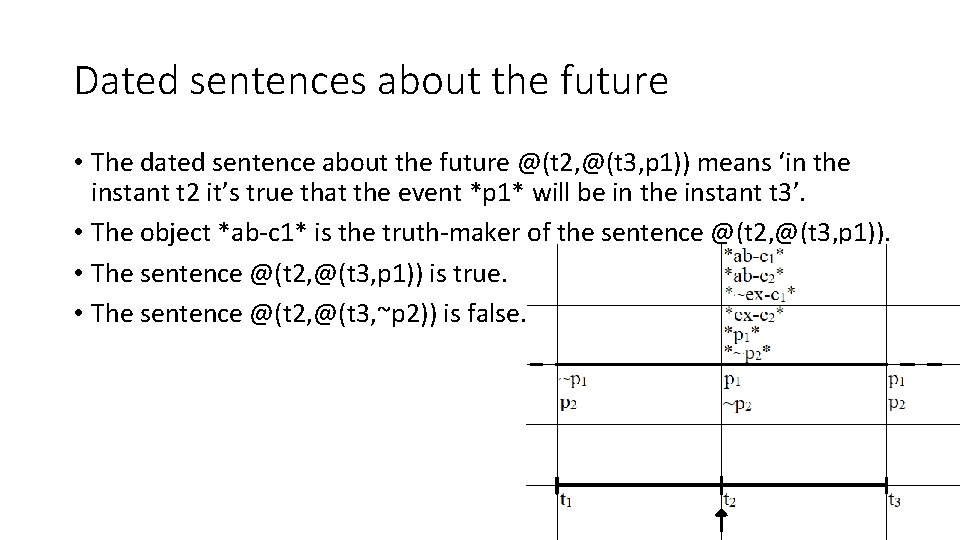

Dated sentences about the future • The dated sentence about the future @(t 2, @(t 3, p 1)) means ‘in the instant t 2 it’s true that the event *p 1* will be in the instant t 3’. • The object *ab-c 1* is the truth-maker of the sentence @(t 2, @(t 3, p 1)). • The sentence @(t 2, @(t 3, p 1)) is true. • The sentence @(t 2, @(t 3, ~p 2)) is false. 10

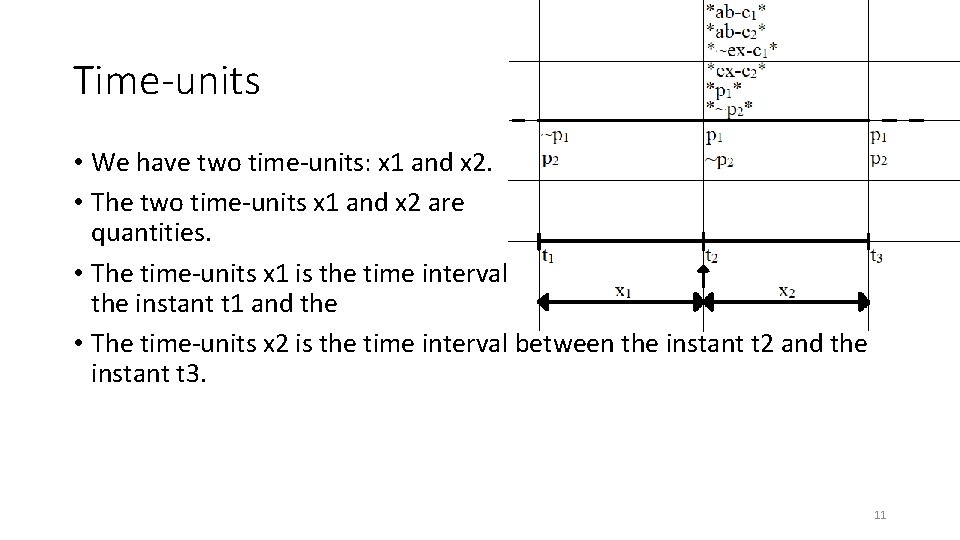

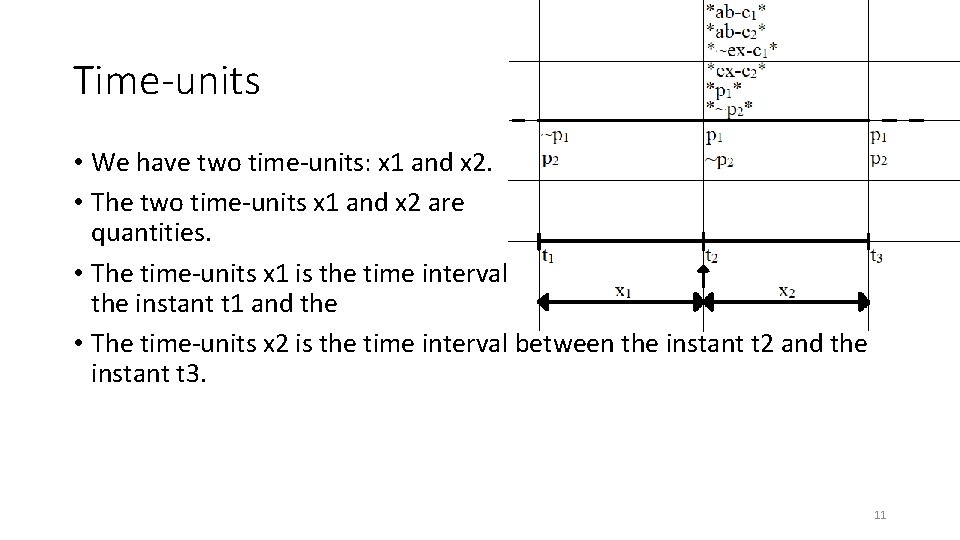

Time-units • We have two time-units: x 1 and x 2. • The two time-units x 1 and x 2 are whole quantities. • The time-units x 1 is the time interval between the instant t 1 and the instant t 2. • The time-units x 2 is the time interval between the instant t 2 and the instant t 3. 11

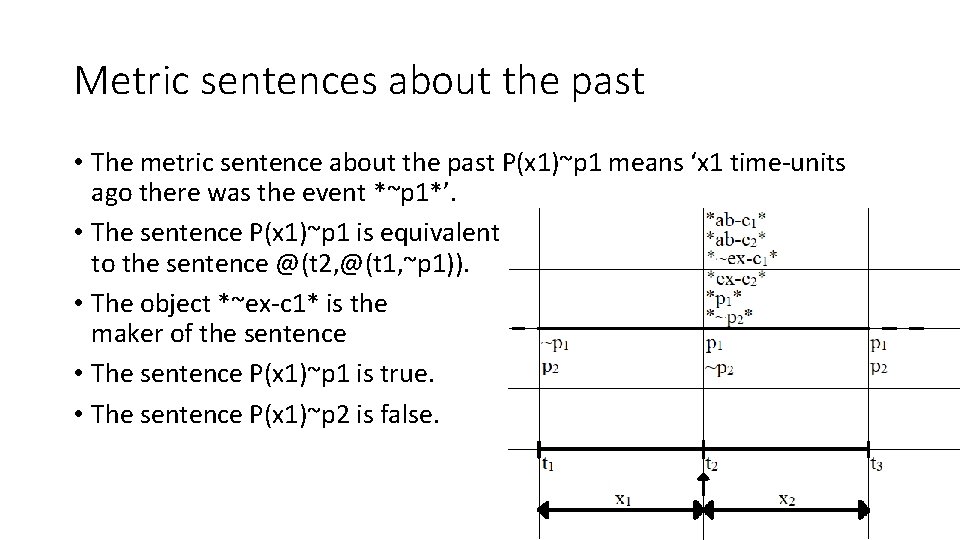

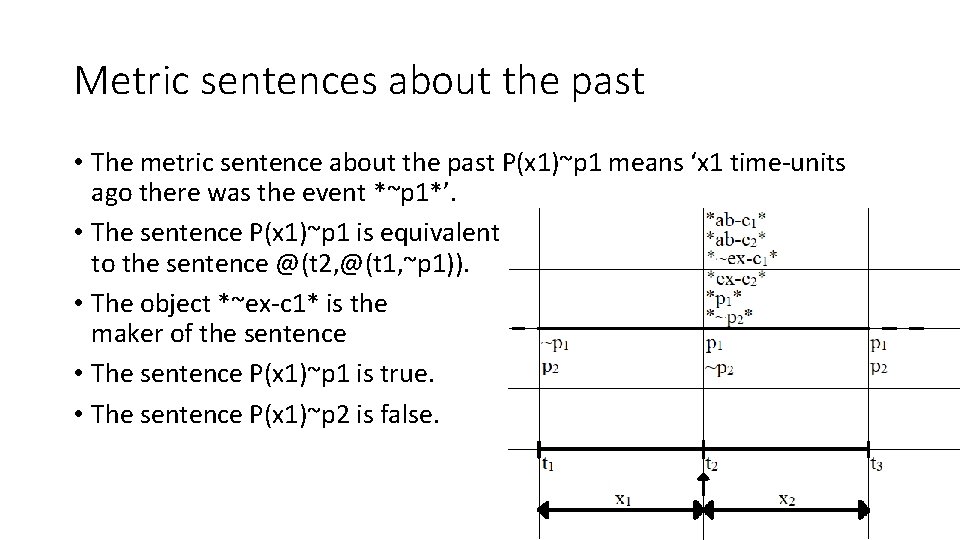

Metric sentences about the past • The metric sentence about the past P(x 1)~p 1 means ‘x 1 time-units ago there was the event *~p 1*’. • The sentence P(x 1)~p 1 is equivalent to the sentence @(t 2, @(t 1, ~p 1)). • The object *~ex-c 1* is the truthmaker of the sentence P(x 1)~p 1. • The sentence P(x 1)~p 1 is true. • The sentence P(x 1)~p 2 is false. 12

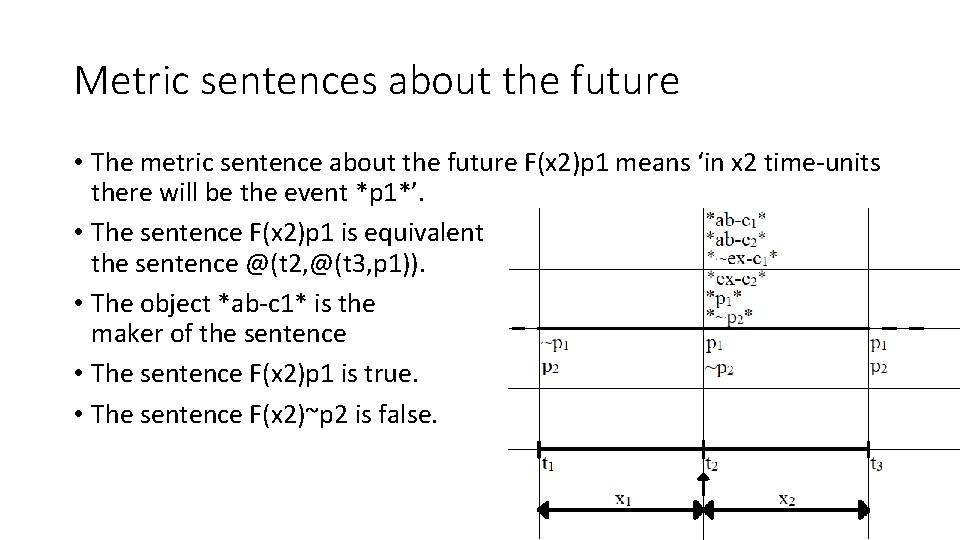

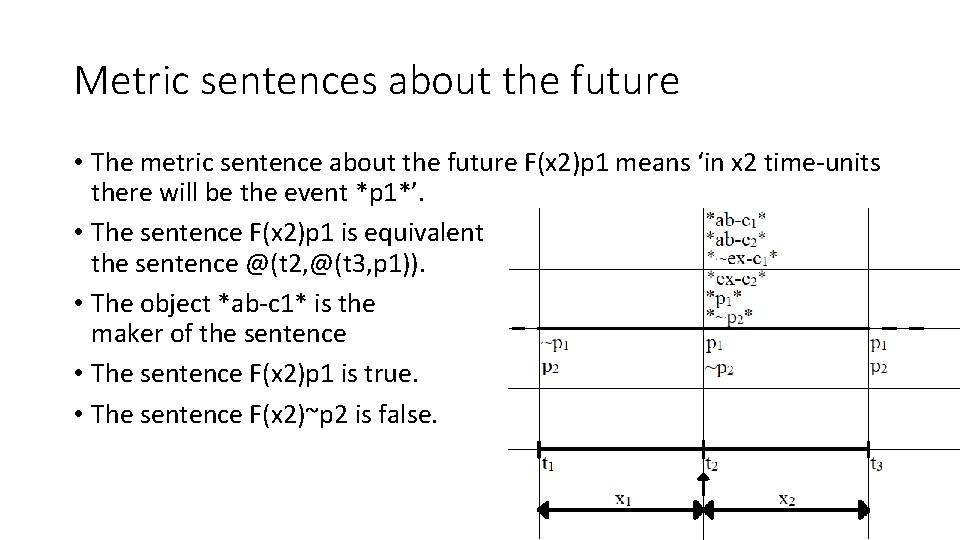

Metric sentences about the future • The metric sentence about the future F(x 2)p 1 means ‘in x 2 time-units there will be the event *p 1*’. • The sentence F(x 2)p 1 is equivalent to the sentence @(t 2, @(t 3, p 1)). • The object *ab-c 1* is the truthmaker of the sentence F(x 2)p 1. • The sentence F(x 2)p 1 is true. • The sentence F(x 2)~p 2 is false. 13

The DCL-argument • The DCL-argument is Diodorus Cronus and Lavenham’s argument. • This argument has five premises but the most important ones are (P 3) and (P 5): • [(P 1) F(x 2)p→P(x 1)F(x 2)p]; • [(P 2) □(P(x 2)F(x 2)p→p)]; • (P 3) P(x 2)p→□P(x 2)p; • [(P 4) (□(p→q)&□p)→□q]; • (P 5) F(x 2)p˅F(x 2)~p. 14

(P 3) The necessity of the past • (P 3) P(x 2)p→□P(x 2)p. • This symbol ‘□’ means ‘it is necessary that. . . ’. • The premise (P 3) means ‘If x 2 time-units ago there was the event *p*, then it is necessary that x 2 time-units ago there was the event *p*. • The premise (P 3) expresses the necessity of the past. • For each true sentence about the past, in the present there is the abstract ex-concrete object as the truth-maker of the sentence. • In other words, each true sentence about the past matches an abstract exconcrete object, as truth-maker of the sentence, in the present. • Every true sentence about the past is necessarily true. 15

(P 5) (PFME)The principle of the future middle -excluded • (P 5) F(x 2)p˅F(x 2)~p. • The premise (P 5) means ‘in x 2 time-units there will be the event *p* or in x 2 time-units there will be the event *~p*. • The premise (P 5) expresses the principle of the future middleexcluded (PFME). • In the future there will be an event or in the future there will be the opposite of that event. 16

(LF) Logic fatalism • From the five premises (P 1)-(P 5), it is possible to infer the conclusion: • (LF) □F(x 2)p˅□F(x 2)~p. • The conclusion (LF) means ‘it is necessary that in x 2 time-units there will be the event *p* or it is necessary that in x 2 time-units there will be the event *~p*. • The conclusion (LF) expresses logic fatalism, the necessity of the future. This is equivalent to close future or determinism. Therefore, there is not freedom. • For each true sentence about the future, in the present there is the abstract abconcrete object as truth-maker of the sentence. • In other words, each true sentence about the future matches an abstract abconcrete object, as truth-maker of the sentence, in the present. • Every true sentence about the future is necessarily true. 17

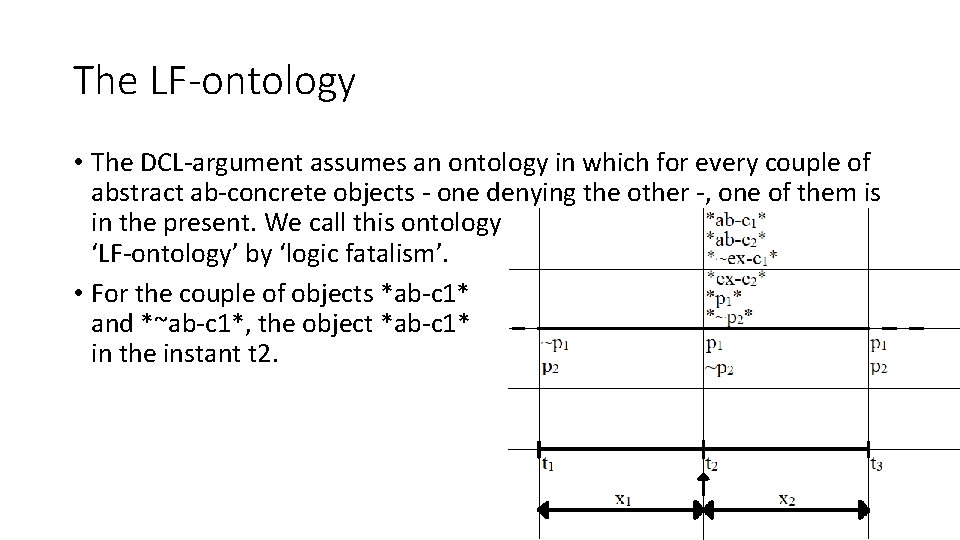

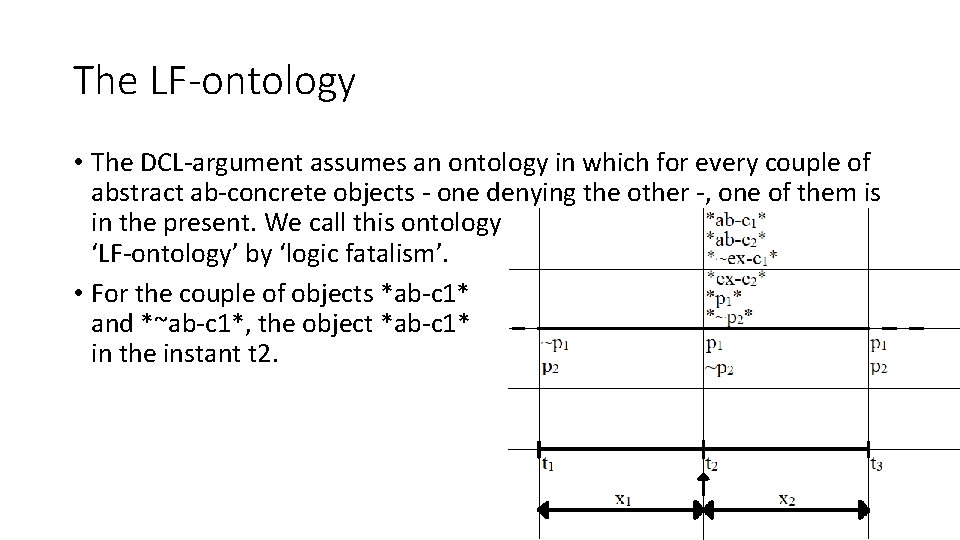

The LF-ontology • The DCL-argument assumes an ontology in which for every couple of abstract ab-concrete objects - one denying the other -, one of them is in the present. We call this ontology ‘LF-ontology’ by ‘logic fatalism’. • For the couple of objects *ab-c 1* and *~ab-c 1*, the object *ab-c 1* is in the instant t 2. 18

The LF-ontology (2) • The LF-ontology implies the conclusion (LF). • In order to deny the conclusion (LF), it is necessary to deny at least one premise of the DCL-argument. • But in order to deny at least one premise of the DCL-argument, it is necessary to assume an ontology different from the LF-ontology. • The Peirce-system denies the premise (P 5). • The Ockham-system denies the premise (P 3). • We won’t treat Ockham-system. 19

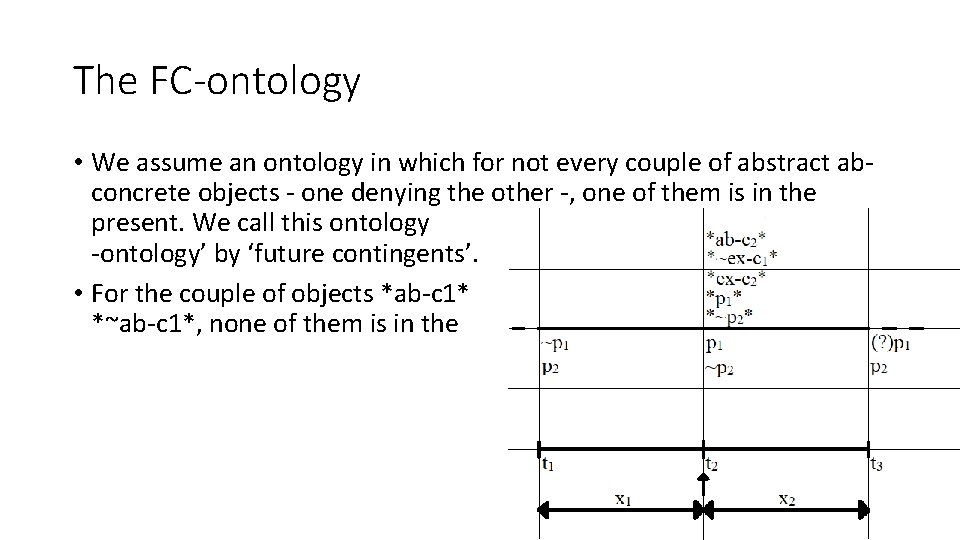

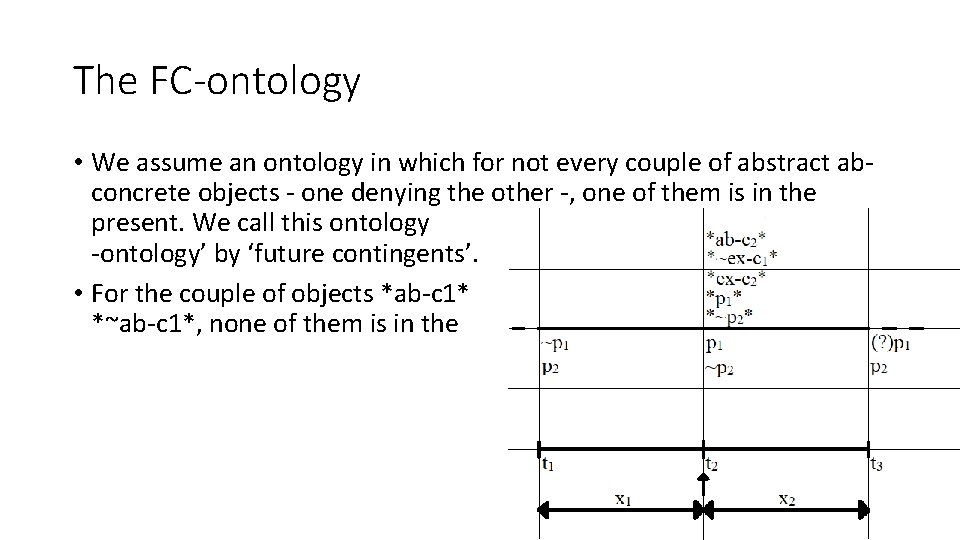

The FC-ontology • We assume an ontology in which for not every couple of abstract abconcrete objects - one denying the other -, one of them is in the present. We call this ontology ‘FC -ontology’ by ‘future contingents’. • For the couple of objects *ab-c 1* and *~ab-c 1*, none of them is in the instant t 2. 20

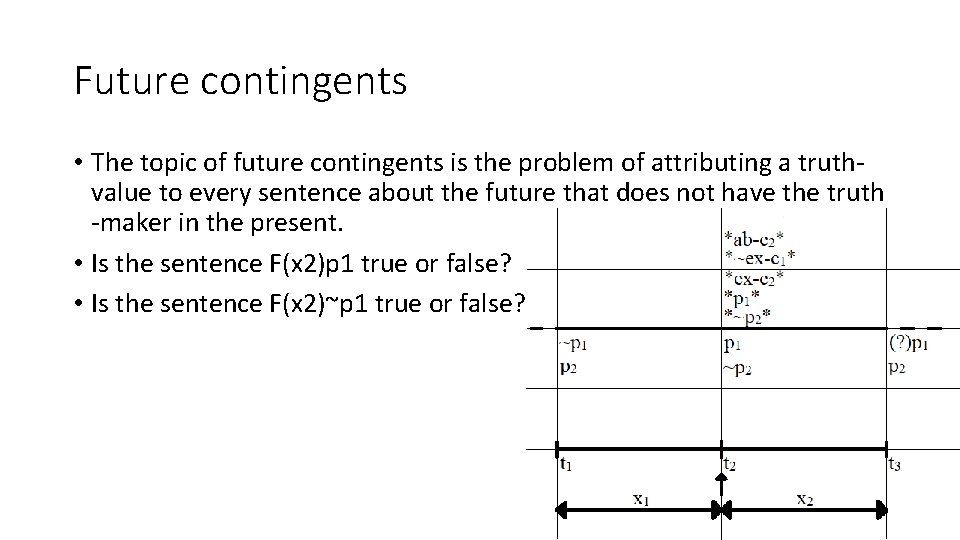

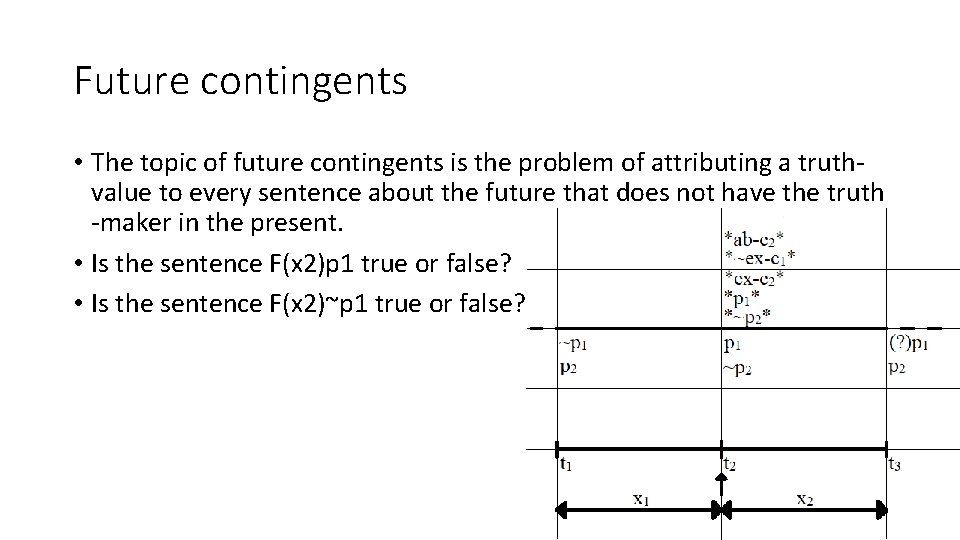

Future contingents • The topic of future contingents is the problem of attributing a truthvalue to every sentence about the future that does not have the truth -maker in the present. • Is the sentence F(x 2)p 1 true or false? • Is the sentence F(x 2)~p 1 true or false? 21

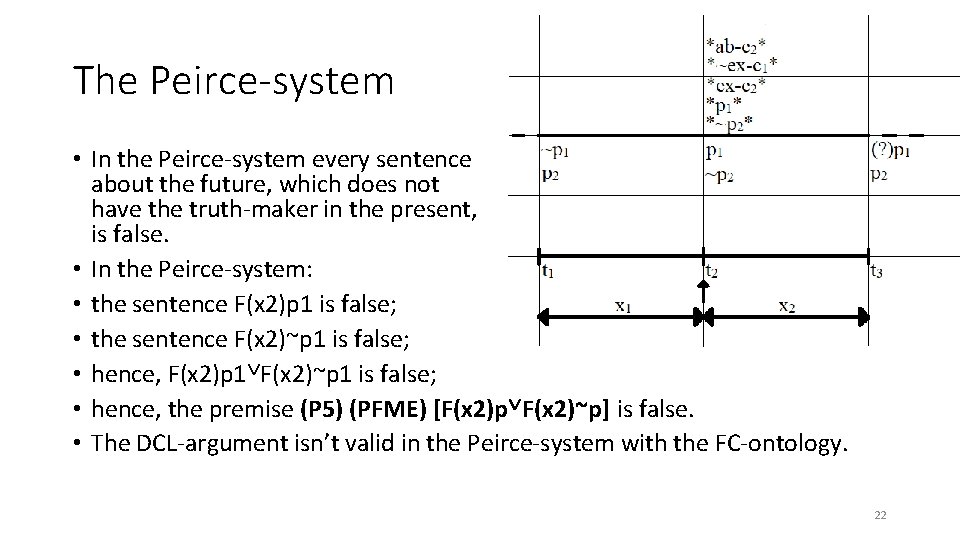

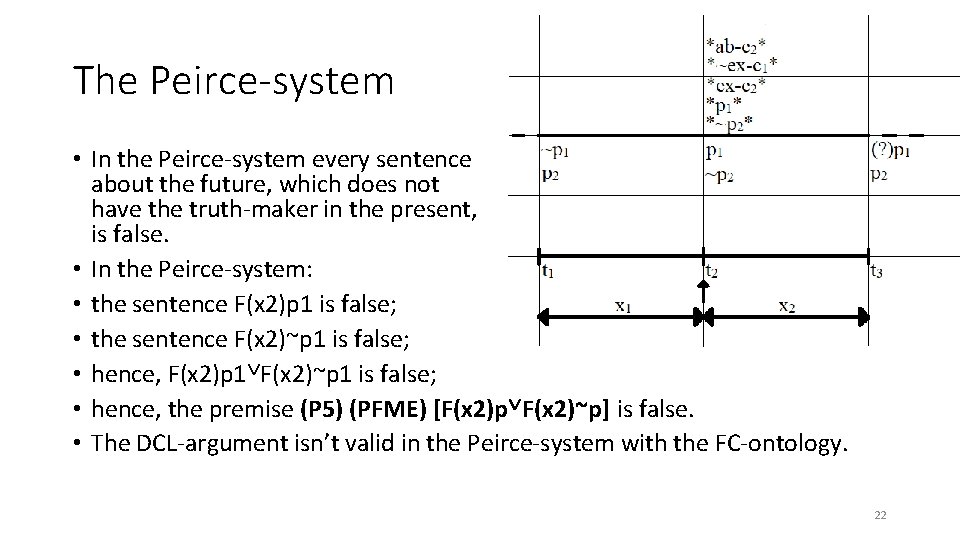

The Peirce-system • In the Peirce-system every sentence about the future, which does not have the truth-maker in the present, is false. • In the Peirce-system: • the sentence F(x 2)p 1 is false; • the sentence F(x 2)~p 1 is false; • hence, F(x 2)p 1˅F(x 2)~p 1 is false; • hence, the premise (P 5) (PFME) [F(x 2)p˅F(x 2)~p] is false. • The DCL-argument isn’t valid in the Peirce-system with the FC-ontology. 22

(PME) The principle of the middle-excluded • In the Peirce-system: • the sentence F(x 2)p 1 is false; • the sentence ~F(x 2)p 1 is true because it is the negation of F(x 2)p 1, that is false; • hence, F(x 2)p 1˅~F(x 2)p 1 is true. • (PME) p˅~p • (PME’) F(x 2)p˅~F(x 2)p • Denying the premise (P 5) (PFME) [F(x 2)p˅F(x 2)~p], the Peirce-system does not deny the principle (PME). • The sentence F(x 2)~p in not equivalent to the sentence ~F(x 2)p. • The sentence F(x 2)~p is not the negation of the sentence F(x 2)p. 23

Conclusion (1) • If we assume the LF-ontology, then the DCL-argument is valid. • If we assume the FC-ontology, then the DCL-argument is not valid. • The Peirce-system assumes the FC-ontology and it denies the principle (PFME). This denial makes the DCL-argument not valid in the Peirce-system as we wanted to prove. 24

Conclusion (2) • The LF-ontology implies logic fatalism or close future or determinism. • Every future event, including volitions, is pre-determined by a cause in a previous instant. • The FC-ontology implies open future or indeterminism. • Not every future event is pre-determined by a cause in a previous instant. Indeed, not for every couple of abstract ab-concrete objects one denying the other -, one of them is in the present. I. e. , our future volition and its opposite are abstract ab-concrete objects that are not yet in the present. Hence, our volition is not pre-determined in a previous instant until we decide it (see Prior, Some Free Thinking about Time). 25

Conclusion (3) • We cannot say anything nor can we prove anything without assuming any ontology in a previous instant. • Do not think that there is the FC-ontology because there is the valid DCL-argument. It is exactly the opposite. There is the DCL-argument because there is the FC-ontology. If we assume the FC-ontology, then there is the valid DCL-argument. • We can choose which ontology to assume. 26

Conclusion (4) • When someone tells us that we are not free, he usually tries to demonstrate this by saying that our will is always pre-determined (consciously or unconsciously) by a previous cause. To be true, he is not proving anything, but he is assuming the FC-ontology. Nevertheless, as an assumption, it cannot be demonstrated. Otherwise, we would have a petitio principii. Indeed, we cannot prove experimentally that all our volitions are pre-determined. • I think that we might be free by assuming the FC-ontology. On the contrary, by assuming the LF-ontology, we might not. 27

Bibliography • Øhrstrøm, Peter and Hasle, Per, "Future Contingents", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed. ), URL = <https: //plato. stanford. edu/archives/win 2015/entries/futurecontingents/>, pp. 1 -28. • Orilia F. , On the Existential side of the Eternalism-Presentism Dispute, Manuscrito – Rev. Int. Fil. Campinas, v. 39, n. 4, pp. 225 - 254, out. -dez. 2016, URL = <https: //periodicos. sbu. unicamp. br/ojs/index. php/manuscrito/article /view/8647885/14669>, pp. 238 -250. 28