JULIA KRISTEVA THE THEORY OF INTERTEXTUALITY AN INTRODUCTION

- Slides: 25

JULIA KRISTEVA &THE THEORY OF INTERTEXTUALITY “AN INTRODUCTION” by Dudu BAL ÖZBEK

Introduction “In 1966 Paris witnessed not only the publication of Jacques Lacan's Ecrits and Michel Foucault's Les Mots et les choses (The Order of Things), but also the arrival of a young linguist from Bulgaria. At the age of 25, Julia Kristeva, equipped with a doctoral research fellowship, embarked on her intellectual encounter with the French capital. ” (Moi, 1986: 1) Since the mid-1960 s, Julia Kristeva has become influential in international critical analysis, cultural theory, linguistics, semiotics, psychoanalysis and feminism. She is a Bulgarian. French philosopher, literary critic, linguist, psychoanalyst, feminist, and, most recently, novelist. Though she was influential in various disciplines, this presentation will primarily focus on her concept of “intertextuality” and the relevant social theories that led to the presentation of the concept as a term.

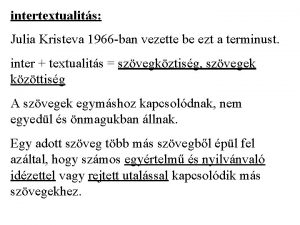

Intertextuality as a term was first used in Julia Kristeva's "Word, Dialogue and Novel" (1966) and then in "The Bounded Text" (1966 -67), essays she wrote shortly after arriving in Paris from Bulgaria. Kristeva referred to texts in terms of two axes: a horizontal axis connecting the author and reader of a text, and a vertical axis, which connects the text to other texts. The literary word is an intersection of textual surfaces rather than a point (a fixed meaning). It is a dialogue among several writings. The communication between author and reader is always paired with an intertextual relation between words and their prior existence in past texts; that is, the text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations and any text is the absorption and transformation of another. (Kristeva, 1986)

While explaining the term, Kristeva argues that authors do not create their texts from their own mind, but rather compile them from preexistent texts. Thus, the text becomes “a permutation of texts, an intertextuality: in the space of a given text, several utterances, taken from other texts, intersect and neutralize one another” (Kristeva, 1980: 36).

So, we can say that there always other words in a word, and other texts in a text. “The concept of intertextuality requires, therefore, that we understand texts not as self-contained systems but as differential and historical, as traces and tracings of otherness, since they are shaped by the repetition and transformation of other textual structures. Rejecting the New Critical principle of textual autonomy, theory of intertextuality insists that a text cannot exist as a selfsufficient whole, and so, that it does not function as a closed system. ” (Martinez-Alfaro, 1996: 268).

The term “intertextuality” was first introduced by Julia Kristeva during 1960 s but she was highly influenced by the previous work of Ferdinand de Saussure and Mikhail Bakhtin. It can be said that her own work on intertextuality is also an example of the term itself. Both of these theoreticians and the social, cultural and the political atmosphere of the time were influential in the process of formalizing theory of intertextuality. “There is no doubt that this concept was not created ex nihilo out of the fertile brain of Julia Kristeva. But she was the first to use it in print in an article on Bakhtin, whom she had read in Russian while still a student in Bulgaria, before she settled in France” (Haberer, 2007: 56).

It was, then, this specific and relatively unusual intellectual background that enabled Kristeva to take up a critical position towards structuralism right from the beginning. With this background, she inspired even her teachers at university in Paris such as Roland Barthes and Lucien Goldmann. “The reason why Kristeva right from the start of her career in Paris was in a position to inspire her own teachers is to be found in her unique intellectual background. Having equipped with fluent Russian, her Eastern European training enabled her to gain first-hand knowledge of the Russian Formalists, and - more importantly - of the great Soviet theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, whose work she (along with Tzvdtan Todorov) was instrumental in introducing to Western intellectuals” (Moi, 1986: 2).

Actually, in her essays “The Bounded Text” and “Word, Dialogue and Novel”, Kristeva introduces the work of the Russian literary theorist M. Bakhtin to the French-speaking world. “Bakhtin’s work is, today, extraordinarily, influential within the fields of literary theory and criticism, and in linguistics, political and social theory, philosophy and many other disciplines. However, in the 1960 s, his work was relatively unknown, much of it still unpublished” (Allen, 2011: 14).

In addition to her intellectual background, any assessment of Julia Kristeva’s launching of the notion of intertextuality must surely begin by recalling the social and political context of the 1960 s. The late 1960 s were in Paris the years when the human sciences made a quantum leap forward in all directions, with a number of hyper-active, avant-gardist intellectuals trying to apply theories and methodologies of those sciences to the study of literature. Foremost were the fast-developing sciences of post-Saussurean linguistics (Roman Jakobson, Émile Benveniste), post-Freudian psychoanalysis (Jacques Lacan), semiology (Roland Barthes) and anthropology (Claude Levi. Strauss). (Haberer, 2007)

It was the heyday of theorists, the years of transition from structuralism to poststructuralism (not clearly distinguished from what later came to be known as postmodernism) with also Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, Michel Foucault all at work, the years when all forms of authority were challenged – the Government, de Gaulle, tradition, capitalism, reason, the Establishment, the Author, etc. They were the years that led to the great libertarian subversive explosion of May 1968 in France, echoed and sometimes amplified in the campuses of many other countries, notably in Prague, in Belfast, and in North America. (Haberer, 2007) Meanwhile in Russia, during the late 1960 s and early 1970 s, after years of censorship, many valuable works of certain writers including those of Bakhtin’s, began to be rediscovered and republished.

All these developments led to harsh questioning and attacks towards the existing theories in the intellectual world and finally led to post-structuralist and postmodern theories. “Postmodernism can be viewed as a development of modernism which manifested itself during the first decades of the 20 th century, in the years preceding and following the great fracture of the first World War. Modernism was characterized by the loss of stable values, by the loss of belief in the possibility of an objective truth and in the validity of totalizing ideologies, by the rejection of formal aesthetic theories, the emphasis given to subjectivity, to the discontinuous and the fragmentary, also by the place given to reflexivity and self-consciousness in the production of texts” (Haberer, 2007: 54).

Within this framework, Julia Kristeva presented theory of intertextuality along with these developments in the social and scientific context. She used her intellectual background to introduce the ideas of Mikhail Bakhtin and Russian formalists to the Western scholars and added her own understanding and conceptualization to the discussion. At this point we should note that any analysis of Kristeva's theory about intertextuality must begin with her views on language, since the former is a direct consequence of the latter.

Kristeva studied both Saussurean and Bakhtinian models in linguistics and used their ideas while establishing her theory of intertextuality. “It is viable to cite the Russian literary theorist M. M. Bakhtin as the originator, if not the term “intertextuality”, then at least of the specific view of language which helped others articulate theories of intertextuality. Bakhtin, as we will see, takes a very different approach to language and is far more concerned than Saussure with the social contexts within which words are exchanged” (Allen, 2011: 10). Saussure views language as a generalized and abstract system but for Bakhtin, language is related to specific social sites, registers, specific moments of utterance and reception. Saussurean linguistics remains something describable as “abstract objectivism”. However, to produce an abstract account of literary language or any language is to forget that language is utilized by individuals in specific social contexts. Thus, while Saussure is interested in language as an abstract and readymade system, Bakhtin is interested only in the dynamics of living speech (Allen 2011; Martinez-Alfaro 1996).

It is true enough to say that the basis upon which many of the major theories of intertextuality are developed takes us back to Saussure’s notion of the differential sign. With the developments in the specific context of the problematics in linguistics during 1960 s, “the sign itself being split into signifier and signified, the very notion of meaning as something fixed and stable, even though it sometimes had to be deciphered, was lost and replaced by that of the sliding, shifting, floating signified. Meaning could no longer be viewed as a finished product, it was now caught in a process of production… All the imaginary representations of a solid, identifiable self, or ego, in control of language and capable of expressing himself, were denounced and replaced by the notion of a subject intermittently produced by his parole – literally spoken by language. ” (Haberer, 2007: 56).

These post-structuralist views towards the nature of language resulted in a different perception related to the function of language in forming identities. Influenced with the ideas of Lacan, poststructuralists viewed language as part of a cultural system which directly constructs and produces the self. The notion of the self or ego in control of language is replaced by the idea that language is in control of the self. Similarly, language is not just a tool to express ideas but it is rather the system which forms those ideas and concepts as well as the identities. If culture and language are so effective on how people think, then it is difficult to talk about the originality of the things that the mind produces. When we question originality, we finally reach the concept of intertextuality in the literary context.

Intertextuality has been adapted by non-literary art forms as well. Since Kristeva uses the term in a general sense in her essays, writers, readers, cultural contexts, history and society, all appear as ‘texts’ and ‘textual surfaces’. She does not limit it to the actual literary context only. So, Kristeva’s semi analytical approach extends beyond the literary text and includes other art forms, such as music, painting, and dance.

In the modernist era, intertextuality is apparent in every section of culture: literature (Eliot, Joyce), art (Picasso), music (Stravinsky, Mahler), photography (Heartfield, Haussmann), etc. , even if it is interpreted in different ways. Postmodernism shows an increase of this tendency which now includes films (e. g. Woody Allen's Play it Again, Sam) and architecture (e. g. Charles Moore's Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans). Risking some degree of oversimplification, one could say that the pretexts of the modernist work are normative (these pretexts come from a wide range of epochs and cultures but the privileged ones are always the canonized and classical texts). The postmodernist work, by contrast, has as its very aim the levelling down of all traditional distinctions between high and low: past and present, classic and pop, art and commerce, they all are reduced to the same status of disposable materials. All in all, the production of art and literature during our century has become an act of creation based on a recycling of previously existing works. (Lesic-Thomas 2005: 5; Martinez-Alfaro 1996: 271)

“Many art works produced in accordance with the postmodern sense of intertextuality, are simply evaluated as attacking traditional art in order to promote some avant-garde movements and ideals. For example, Marcel Duchamp’s well known ready-made “L. H. O. O. Q” is a pun. It is a humorous use of words to create several possible meanings. It is generally assumed that Duchamp decided to use his ready-mades, not only to critique established art conventions, but also to force the audience to discard their preconceived ideas and look at something with a completely different point of view. Moreover, by making the personal image of the portrait, (or feminine gender of the Mona Lisa) ambiguous, Duchamp presents his observers a new perspective on a classical work of art. ” (Genç, n. d. )

In music, famous composer Nikolaus Decius, adapted J. S. Bach’s “Matthaus Passion” to his cantatas. Although the musical structure of the cantatas are different, the text follows Bach’s work. The composer composed the same text with different music by using pastiche method. (Önal, 2013) William Blake’s work can be another example to show the intertextuality even between different art forms. Blake's illustrated books were much imitated in the early twentieth century, and the emergence of radical ideas about alternative futures heightened the appeal of Blake's prophetic literature. Aldous Huxley took up the idea of The Doors of Perception, in a 1954 book of the same name about mind expansion through ingestion of mescaline. The book takes its title from a phrase in William Blake's 1793 poem The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. In The Doors of Perception Huxley told his experiences when taking mescaline. This book was the influence behind Jim Morrison's naming his band The Doors in 1965.

CONCLUSION Since 1960 s, when Julia Kristeva presented the concept of “intertextuality” by using her intellectual background in Russian Formalism and especially the work of Mikhail Bakhtin, the term has been used as an umbrella word for any critical analysis between two or more texts. With the term intertextuality, Kristeva proposed that the text is not an individual, isolated object but a compilation of cultural textuality. She believes that the individual text and the cultural text are made from the same textual material and cannot be separated from each other.

Because Kristeva’s theory raises questions related to the matter of originality, the corpus of texts which are all related to each other is like a bunch of wires which blend and clash with each other. Thus, “the intertext has been compared with Gilles Deleuze’s notion of the rhizome, a network that spreads and sprawls, has no origin, no end, no hierarchical organization. Analogies have also been made between intertextuality and the development of hypertexts and of the World Wide Web, free from the dominant linear, hierarchical models. Postmodern systems of communication have thus created the conditions for what Ihab Hassan calls “the intertextuality of all life. ” For him, ‘a patina of thought, of signifiers, of ‘connections’, now lies on everything the mind touches. ’ ” (Haberer, 2007: 57).

REFERENCES 1. Allen, G. (2011). Intertextuality (2 nd ed). England: Routledge 2. Barthes, R. (1978). Image-Music-Text. New York: Hill and Wang 3. Genç, A. (n. d. ). Influence and Intertextuality. Retrieved from www. academia. edu 4. Haberer, A. (2007). Intertextuality in Theory and Practice. Literatura. vol. 49, n. 5, 54 -67. 5. Kristeva, J. (1980). Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art. USA: Columbia University Press 6. Kristeva, J. (1986). Word, Dialogue and Novel. In Toril Moil (ed. ), The Kristeva Reader. New York: Columbia University Press. pp: 34 -62 7. Lesic-Thomas, A. (2005). Behind Bakhtin: Russian Formalism and Kristeva’s Intertextuality. Paragraph. vol. 28, n. 3, 1 -20. 8. Martinez-Alfaro, M. J. (1996). Intertextuality: Origins and Development of The Concept. Atlantis. vol. 18, n. 1/2. 268 -285. 9. Moil, T. (1986). The Kristeva Reader. New York: Columbia University Press 10. Önal, A. (2013). Metinlerarasılık Bağlamında Müzik Sanatında Alıntı ve Yeniden Üretim. SDÜ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. vol. 1, n. 17.

Julia kristeva intertextuality

Julia kristeva intertextuality Julia kristeva semiotic

Julia kristeva semiotic Tybalt jellemzése

Tybalt jellemzése Intertextuality example

Intertextuality example This is the modeling of a texts meaning by another text

This is the modeling of a texts meaning by another text Calque intertextuality

Calque intertextuality Intertextuality nedir

Intertextuality nedir Taylor swift ethnicity

Taylor swift ethnicity Example of adaptation intertextuality

Example of adaptation intertextuality Masthead traduzione

Masthead traduzione Intertextuality examples in songs

Intertextuality examples in songs Example of intertext

Example of intertext Types of intertextuality

Types of intertextuality This refers to

This refers to Intertextuality definition

Intertextuality definition Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Ng-html

Ng-html Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Gấu đi như thế nào

Gấu đi như thế nào Thang điểm glasgow

Thang điểm glasgow Chúa yêu trần thế

Chúa yêu trần thế Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Cong thức tính động năng

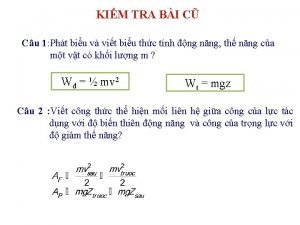

Cong thức tính động năng