INFINITIVES AND INDIRECT STATEMENT First finite and nonfinite

- Slides: 16

INFINITIVES AND INDIRECT STATEMENT

First, “finite” and “non-finite” verbs. . . • If a Latin verb has these five properties: person, number, tense, mood, and voice (PNTMV) – or in other words, if it has a personal ending – we say it is a “finite” or a “finished” verb. • There are other verb forms that do not have all five of these properties. • They have tense, voice, and sometimes number, but not person or mood. • We call these the “non-finite, ” or “unfinished” verb forms. • They have verb stems, but adjective or noun endings. • They are two parts of speech in one: either a verbal noun or a verbal adjective.

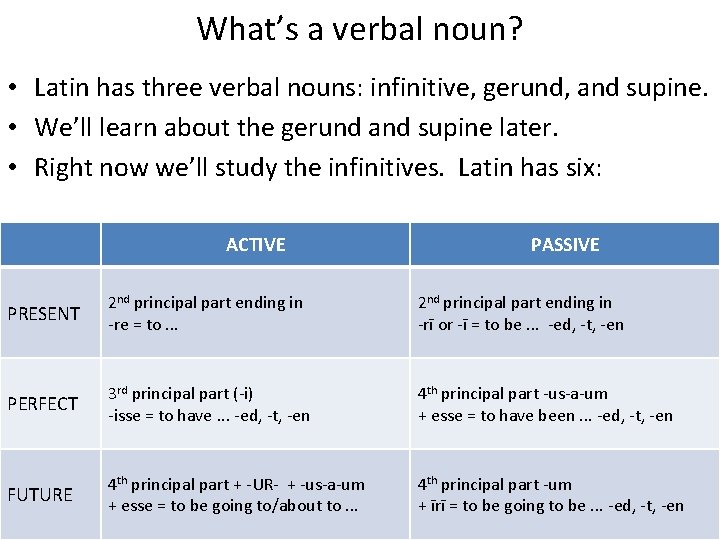

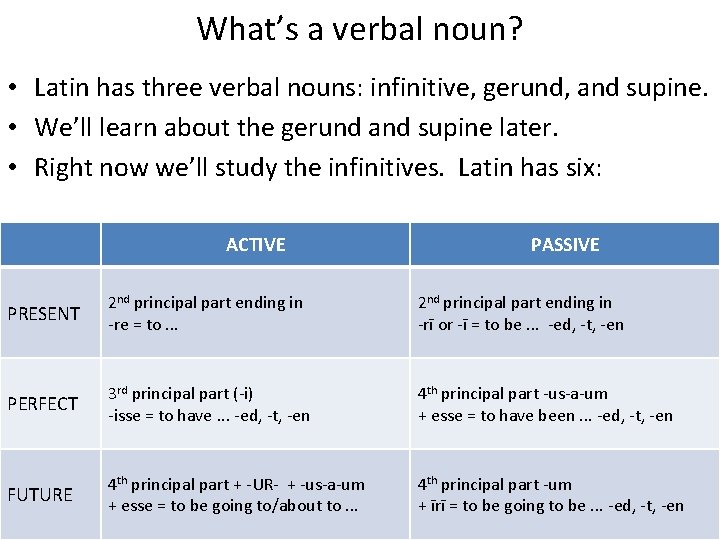

What’s a verbal noun? • Latin has three verbal nouns: infinitive, gerund, and supine. • We’ll learn about the gerund and supine later. • Right now we’ll study the infinitives. Latin has six: ACTIVE PASSIVE PRESENT 2 nd principal part ending in -re = to. . . 2 nd principal part ending in -rī or -ī = to be. . . -ed, -t, -en PERFECT 3 rd principal part (-i) -isse = to have. . . -ed, -t, -en 4 th principal part -us-a-um + esse = to have been. . . -ed, -t, -en FUTURE 4 th principal part + -UR- + -us-a-um + esse = to be going to/about to. . . 4 th principal part -um + īrī = to be going to be. . . -ed, -t, -en

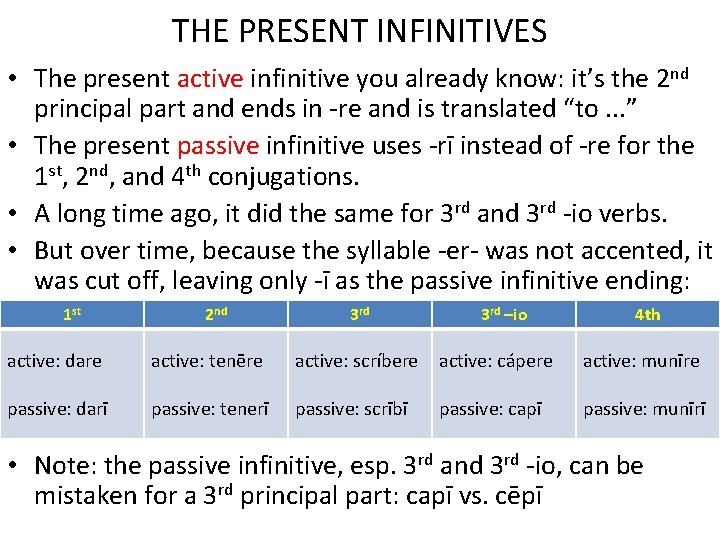

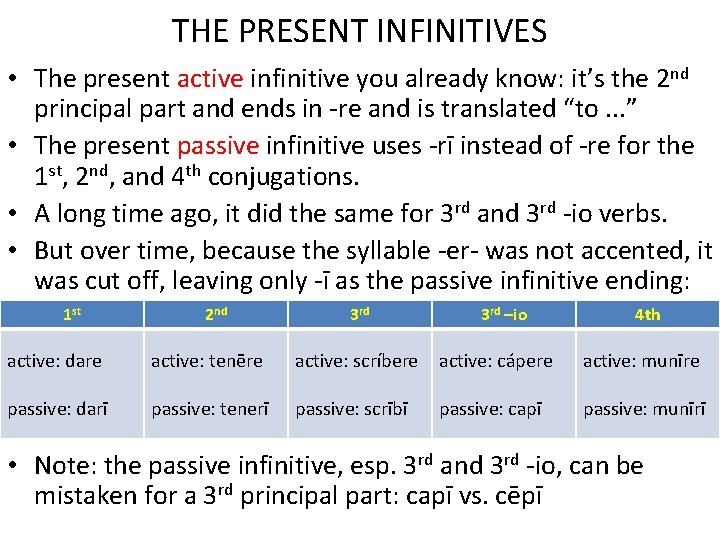

THE PRESENT INFINITIVES • The present active infinitive you already know: it’s the 2 nd principal part and ends in -re and is translated “to. . . ” • The present passive infinitive uses -rī instead of -re for the 1 st, 2 nd, and 4 th conjugations. • A long time ago, it did the same for 3 rd and 3 rd -io verbs. • But over time, because the syllable -er- was not accented, it was cut off, leaving only -ī as the passive infinitive ending: 1 st 2 nd 3 rd –io 4 th active: dare active: tenēre active: scríbere active: cápere active: munīre passive: darī passive: tenerī passive: scrībī passive: capī passive: munīrī • Note: the passive infinitive, esp. 3 rd and 3 rd -io, can be mistaken for a 3 rd principal part: capī vs. cēpī

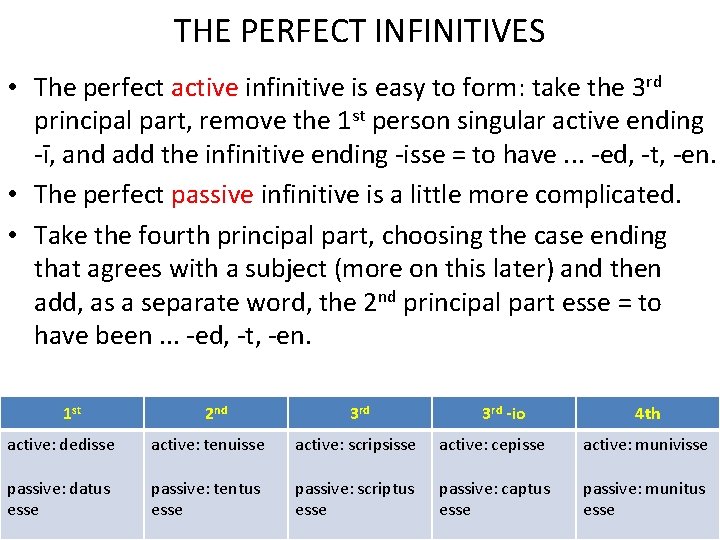

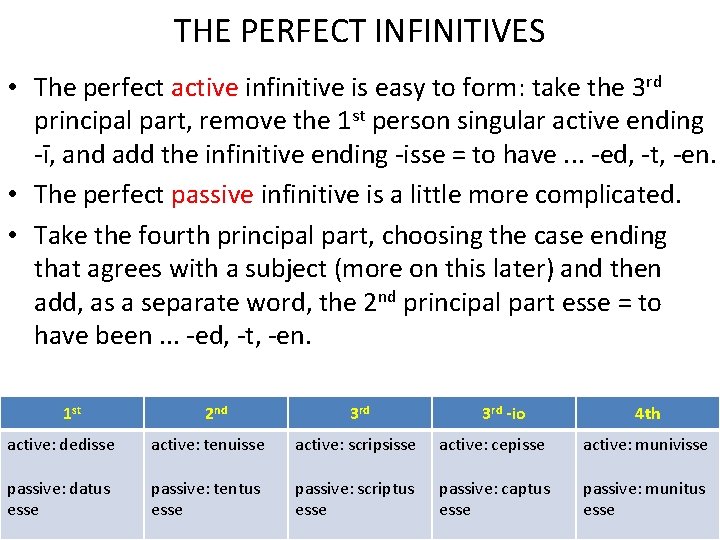

THE PERFECT INFINITIVES • The perfect active infinitive is easy to form: take the 3 rd principal part, remove the 1 st person singular active ending -ī, and add the infinitive ending -isse = to have. . . -ed, -t, -en. • The perfect passive infinitive is a little more complicated. • Take the fourth principal part, choosing the case ending that agrees with a subject (more on this later) and then add, as a separate word, the 2 nd principal part esse = to have been. . . -ed, -t, -en. 1 st 2 nd 3 rd -io 4 th active: dedisse active: tenuisse active: scripsisse active: cepisse active: munivisse passive: datus esse passive: tentus esse passive: scriptus esse passive: captus esse passive: munitus esse

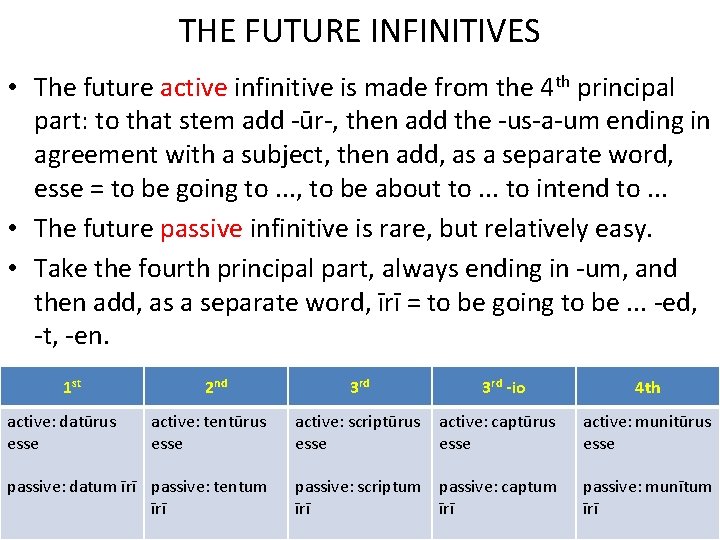

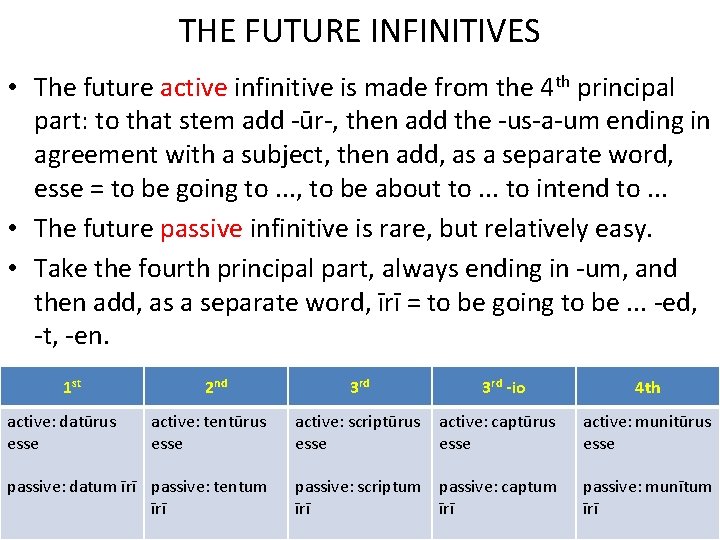

THE FUTURE INFINITIVES • The future active infinitive is made from the 4 th principal part: to that stem add -ūr-, then add the -us-a-um ending in agreement with a subject, then add, as a separate word, esse = to be going to. . . , to be about to. . . to intend to. . . • The future passive infinitive is rare, but relatively easy. • Take the fourth principal part, always ending in -um, and then add, as a separate word, īrī = to be going to be. . . -ed, -t, -en. 1 st active: datūrus esse 2 nd active: tentūrus esse passive: datum īrī passive: tentum īrī 3 rd active: scriptūrus esse 3 rd -io 4 th active: captūrus esse active: munitūrus esse passive: scriptum passive: captum īrī passive: munītum īrī

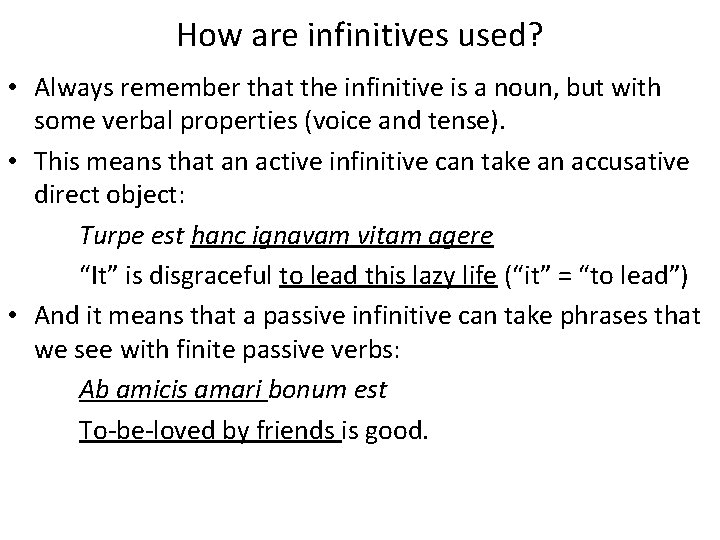

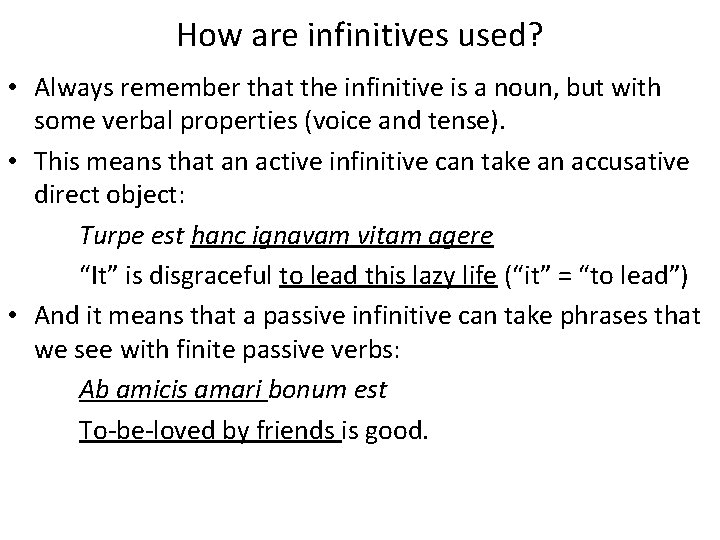

How are infinitives used? • Always remember that the infinitive is a noun, but with some verbal properties (voice and tense). • This means that an active infinitive can take an accusative direct object: Turpe est hanc ignavam vitam agere “It” is disgraceful to lead this lazy life (“it” = “to lead”) • And it means that a passive infinitive can take phrases that we see with finite passive verbs: Ab amicis amari bonum est To-be-loved by friends is good.

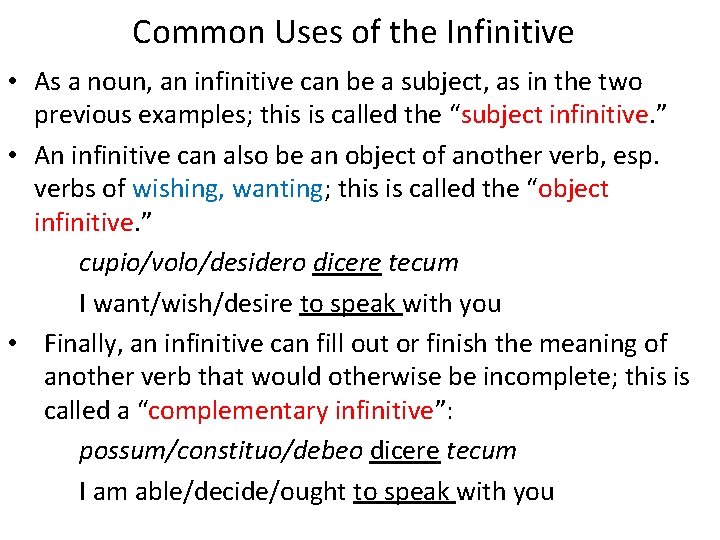

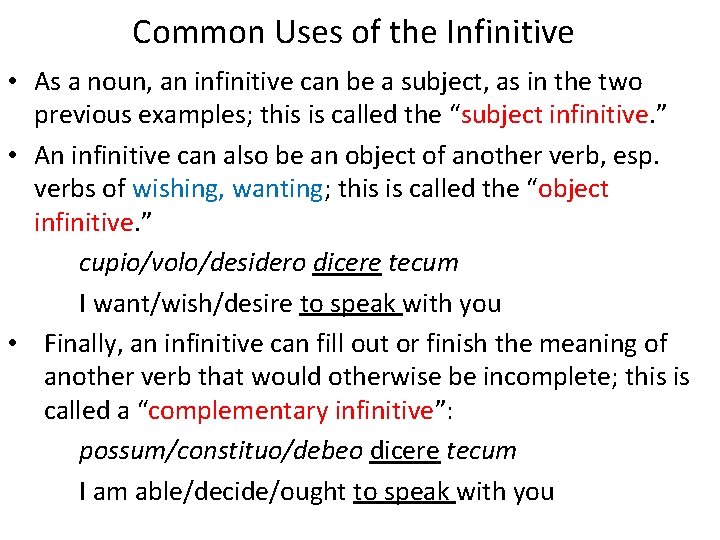

Common Uses of the Infinitive • As a noun, an infinitive can be a subject, as in the two previous examples; this is called the “subject infinitive. ” • An infinitive can also be an object of another verb, esp. verbs of wishing, wanting; this is called the “object infinitive. ” cupio/volo/desidero dicere tecum I want/wish/desire to speak with you • Finally, an infinitive can fill out or finish the meaning of another verb that would otherwise be incomplete; this is called a “complementary infinitive”: possum/constituo/debeo dicere tecum I am able/decide/ought to speak with you

• Let’s review: a finite verb is a finished verb: it has the five properties of person, number, tense, mood, and voice. • The subject of a finite verb is nominative case. • A non-finite verb is an unfinished verb: it has tense and voice, and sometimes number, but it has no person or mood. • A group of words with a subject and predicate – with a finite verb - we call a “clause, ” a closed unit of meaning. • But we can also have a group of words with a subject and predicate – with a non-finite verb form; we call these “nonfinite verb phrases. ” • They are equivalent to various kinds of subordinate or dependent clauses.

• Remember that an infinitive is a noun with some powers of a verb, i. e. , it can be an object itself of another verb, and also take its own object (if it is active voice): Hercules cupivit leonem interficere Hercules wanted / to kill / the lion • The infinitive interficere is the object of cupivit, but interficere also takes the accusative object leonem. • Now let’s look at this example using the verb iubeo, iubere, iussi, iussus-a-um, order, command: Caesar iussit milites pontem facere Caesar ordered / his soldiers / to build/ a bridge. • milites is the acc. dir. obj. of iussit, correct? But at the same time, milites is the subject of facere, • and pontem is the acc. dir. obj. of facere.

• So we have a general rule: the subject of an infinitive is (usually) in the accusative case. • Now we come to a phrase commonly called Indirect Statement. It works like this: • There is a leading verb “of the head” (knowing, seeing, hearing, saying, believing, thinking), so-called verbs of thinking, feeling, perceiving, and saying. • Then there is an accusative noun or pronoun. • That word is then the subject of an infinitive, forming an indirect statement. • In English, we use the all-purpose word “that” to introduce an indirect statement: otherwise it would be a direct quote. • Here’s an example.

• • • Cynthia dicit Genghem Khanum Seras invadere. Cynthia says “that” Genghis Khan is invading China. Cynthia dicit is our main clause Genghem Khanum Seras invadere is our indirect statement. Genghem Khanum is the acc. subject of invadere, while Seras is the acc. dir. obj. of invadere. In English, “Genghis Khan is invading China” could also be a direct statement or quote, right? Only the addition of “that” makes it an indirect statement or quote. In Latin, a direct quote is marked by one of two little irregular verbs, ait (or aiunt) and inquit (or inquiunt). Both mean “say/s” but don’t initiate an indirect statement; instead, they are used where we would use quotation marks.

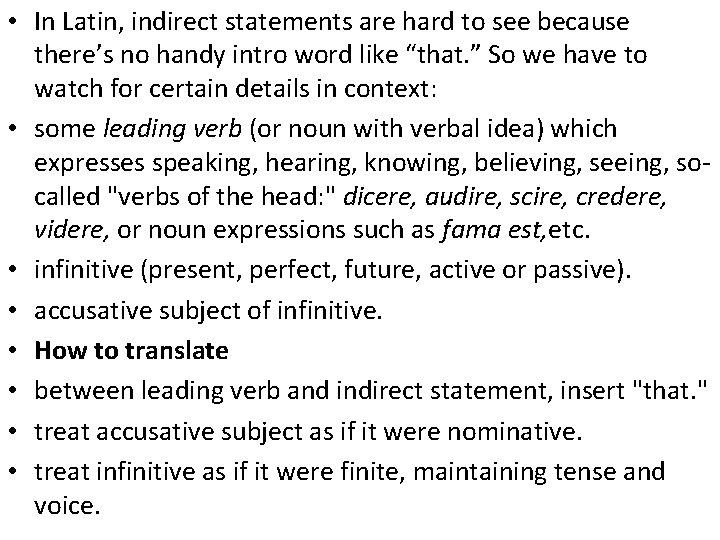

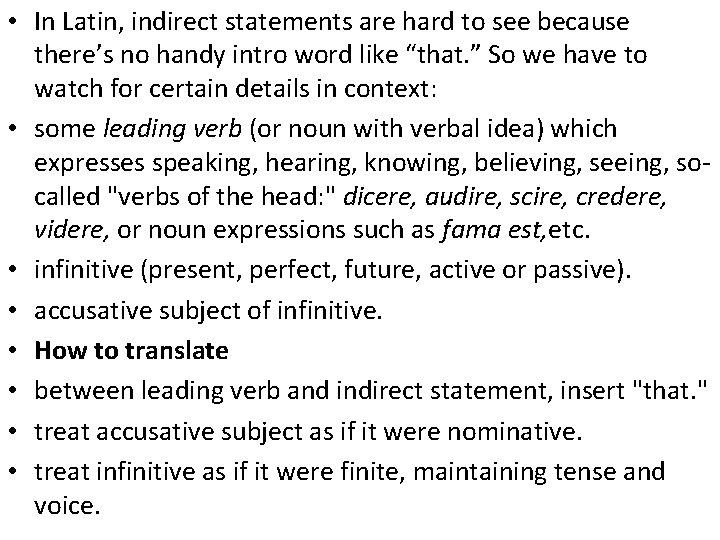

• In Latin, indirect statements are hard to see because there’s no handy intro word like “that. ” So we have to watch for certain details in context: • some leading verb (or noun with verbal idea) which expresses speaking, hearing, knowing, believing, seeing, socalled "verbs of the head: " dicere, audire, scire, credere, videre, or noun expressions such as fama est, etc. • infinitive (present, perfect, future, active or passive). • accusative subject of infinitive. • How to translate • between leading verb and indirect statement, insert "that. " • treat accusative subject as if it were nominative. • treat infinitive as if it were finite, maintaining tense and voice.

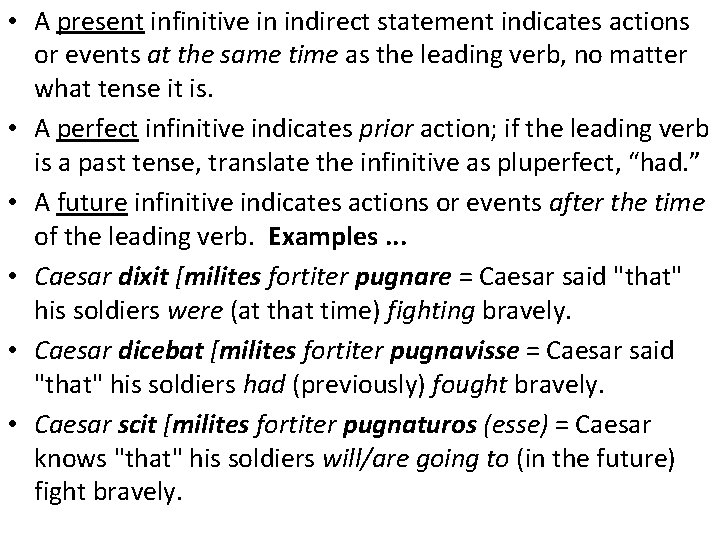

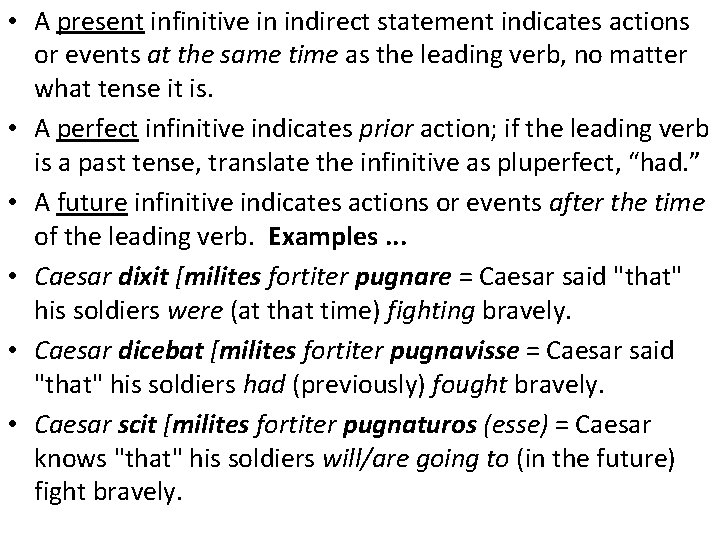

• A present infinitive in indirect statement indicates actions or events at the same time as the leading verb, no matter what tense it is. • A perfect infinitive indicates prior action; if the leading verb is a past tense, translate the infinitive as pluperfect, “had. ” • A future infinitive indicates actions or events after the time of the leading verb. Examples. . . • Caesar dixit [milites fortiter pugnare = Caesar said "that" his soldiers were (at that time) fighting bravely. • Caesar dicebat [milites fortiter pugnavisse = Caesar said "that" his soldiers had (previously) fought bravely. • Caesar scit [milites fortiter pugnaturos (esse) = Caesar knows "that" his soldiers will/are going to (in the future) fight bravely.

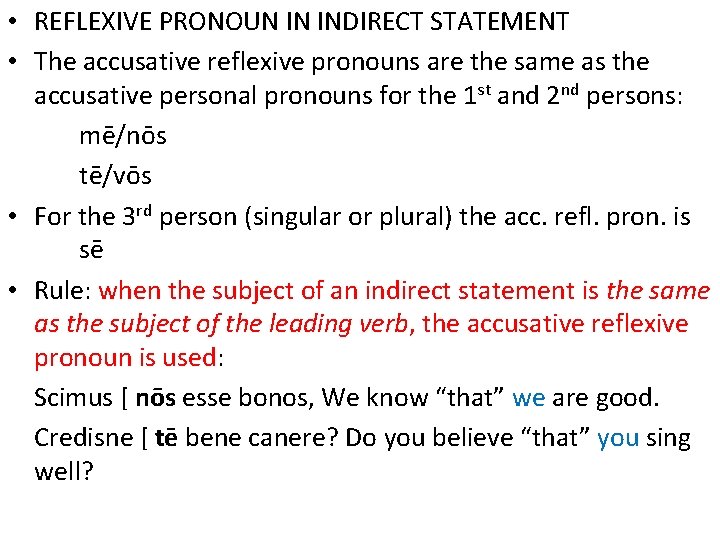

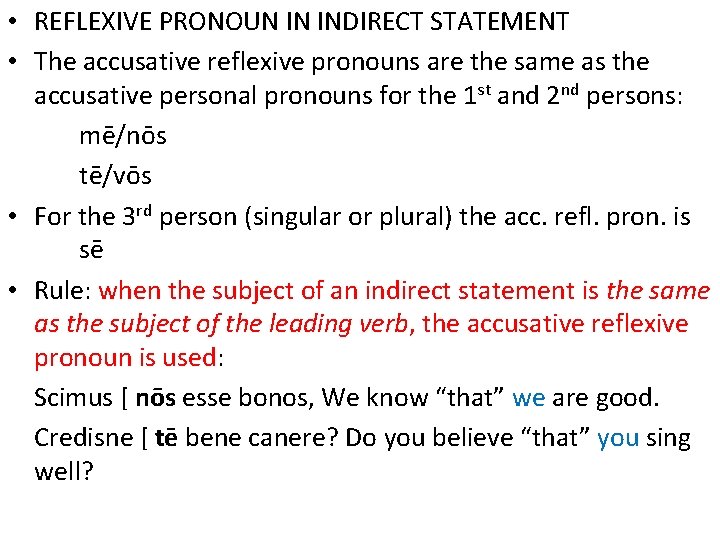

• REFLEXIVE PRONOUN IN INDIRECT STATEMENT • The accusative reflexive pronouns are the same as the accusative personal pronouns for the 1 st and 2 nd persons: mē/nōs tē/vōs • For the 3 rd person (singular or plural) the acc. refl. pron. is sē • Rule: when the subject of an indirect statement is the same as the subject of the leading verb, the accusative reflexive pronoun is used: Scimus [ nōs esse bonos, We know “that” we are good. Credisne [ tē bene canere? Do you believe “that” you sing well?

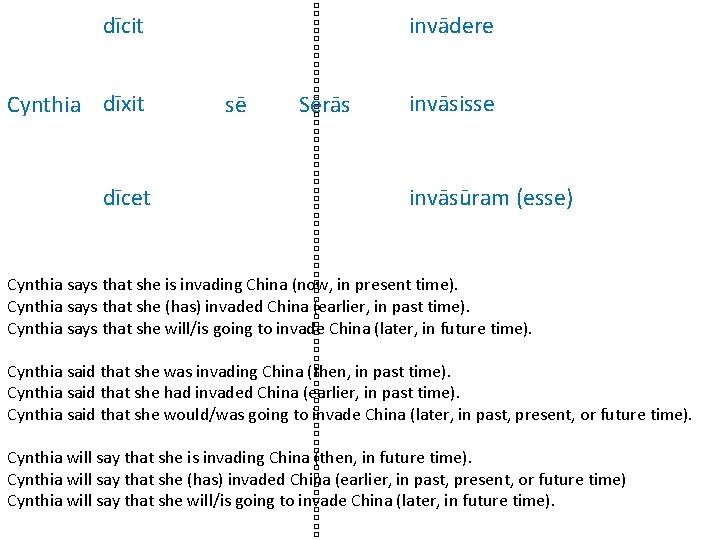

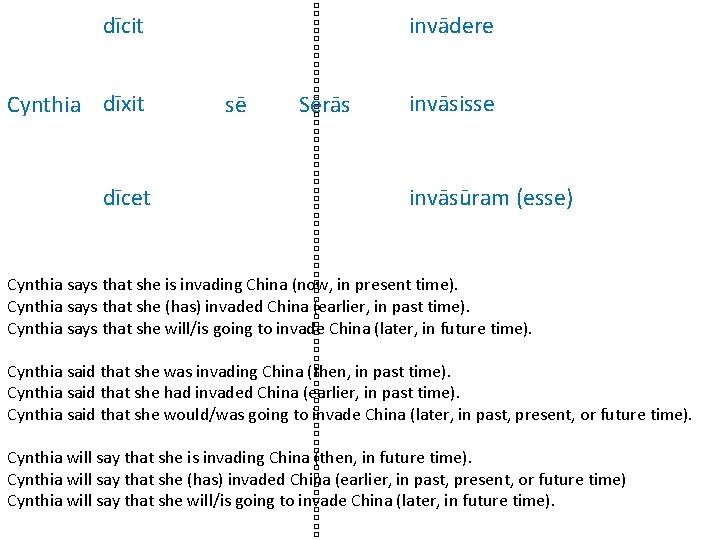

dīcit Cynthia dīxit dīcet sē � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � Sērās invādere invāsisse invāsūram (esse) Cynthia says that she is invading China (now, in present time). Cynthia says that she (has) invaded China (earlier, in past time). Cynthia says that she will/is going to invade China (later, in future time). Cynthia said that she was invading China (then, in past time). Cynthia said that she had invaded China (earlier, in past time). Cynthia said that she would/was going to invade China (later, in past, present, or future time). Cynthia will say that she is invading China (then, in future time). Cynthia will say that she (has) invaded China (earlier, in past, present, or future time) Cynthia will say that she will/is going to invade China (later, in future time).