How to Reduce Causes to Correlations David Papineau

- Slides: 28

How to Reduce Causes to Correlations David Papineau King’s College London and City University New York Epistemic Norms in Theories of Explanation April 29 2019 University of Bordeaux

Correlations and Causes Correlation is not causation, we’re told. But social scientists (economists, sociologists, pol scientists, epidemiologists, everyone who can’t do experiments) have long practised techniques for deriving causal conclusions from correlational data.

Multivariate Regression Some of you might know these techniques from multivariate regression analysis. x = ex y = ax + ey z = bx + cy + ez These equations imply that x causes y and that x and y cause z.

Independent Error Terms How so? Can’t we rewrite so y depends on z and x say? z = (b + ca)ex + cey + ez x = -z/(b + ca) + (caey + ez)/(b + ca) y = z/c – bx/c – ez/c Yes but now the error terms aren’t independent. Structural “equations” must satisfy the constraint that the error terms are independent—and then they will represent causal structure.

Other Names The same ideas were implicit in path analysis (which is just multivariate regression with normalized variables). And it was rediscovered in the 1980 s/90 s (much to their surprise and embarrassment) by computer scientists working on expert systems, under the heading of Bayesian networks. These are all techniques for recovering causal structure from correlational structure. I think they point to a metaphysical moral. Causal structure just is correlational structure.

The Reductive Basis Let me be clear about the reductive basis here. Correlations aren’t just sample correlations, finite thisworldly patterns. Rather they are population correlations, underlying lawlike tendencies for properties to occur together. So the inference to causes involves two stages: first from finite samples to population lawlike correlations (the problem of statistical inference); second from the lawlike correlations to the causal structure. I’m just concerned with the second stage. )

The Reductive Basis How much of a reduction is this—what more is there to causation than “underlying lawlike tendencies for properties to occur together”? But the added value is the direction of causation. It’s one thing to know that two events are somehow causally connected. It’s another to know which causes which--or whether they’re joint effects/causes of a common cause/effect. The correlational facts fix these extra facts.

Correlations to Causes I have long felt this is the key to the nature of causation. Philosophers are finally getting interested in these correlation-cause inferences, but are still slow to draw the metaphysical implications.

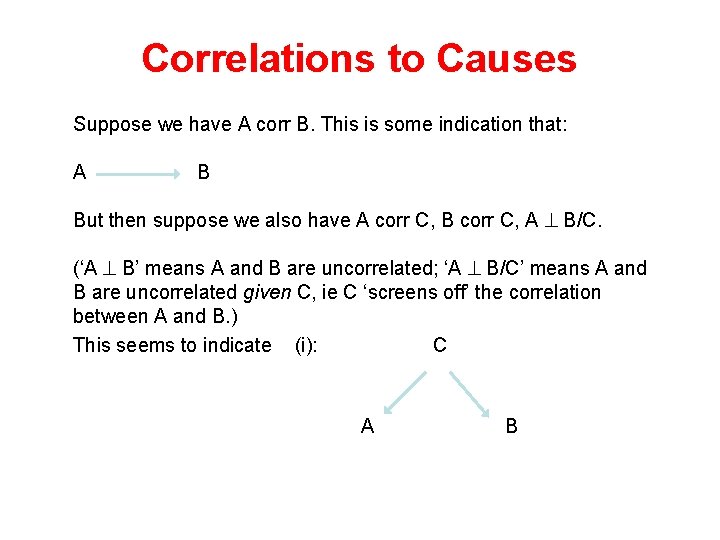

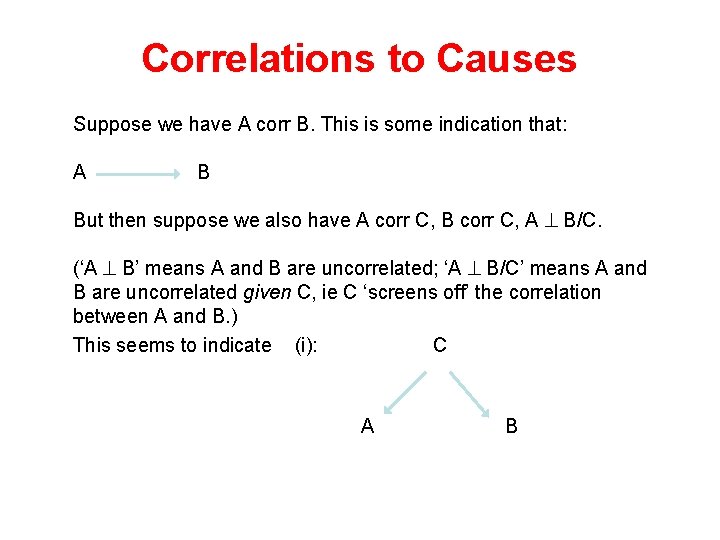

Correlations to Causes Suppose we have A corr B. This is some indication that: A B But then suppose we also have A corr C, B corr C, A B/C. (‘A B’ means A and B are uncorrelated; ‘A B/C’ means A and B are uncorrelated given C, ie C ‘screens off’ the correlation between A and B. ) This seems to indicate (i): C A B

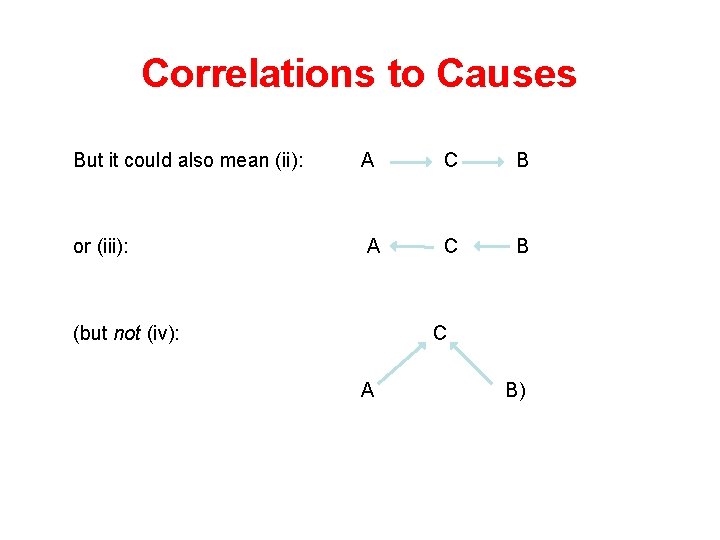

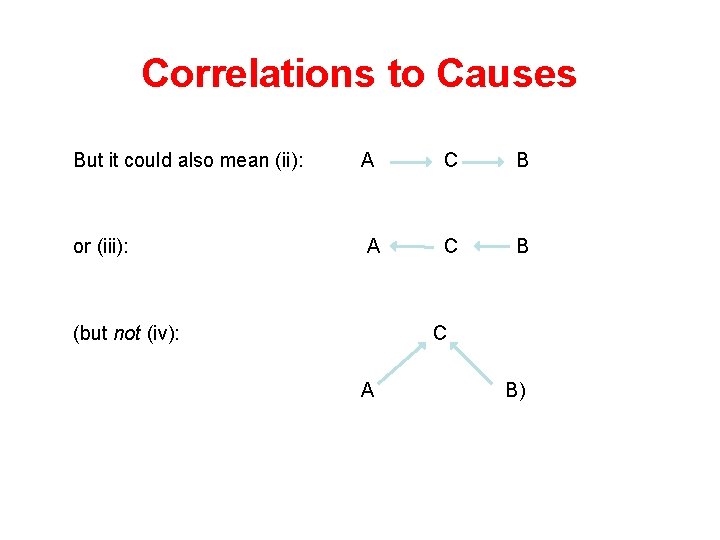

Correlations to Causes But it could also mean (ii): A C B or (iii): A C B (but not (iv): C A B)

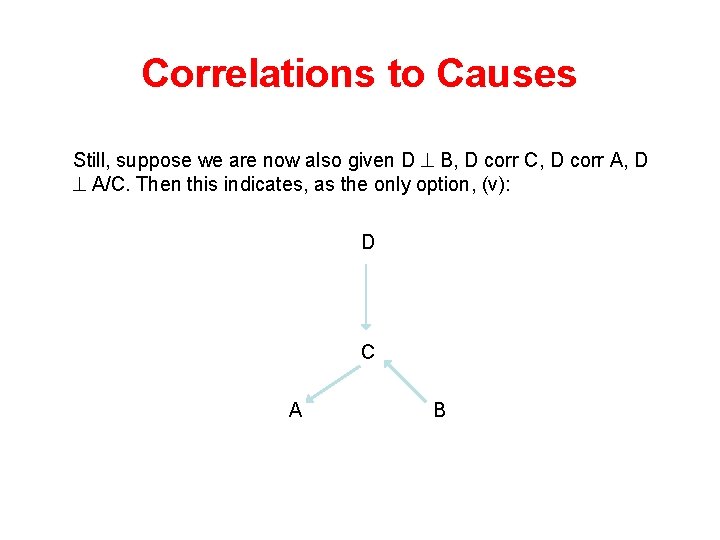

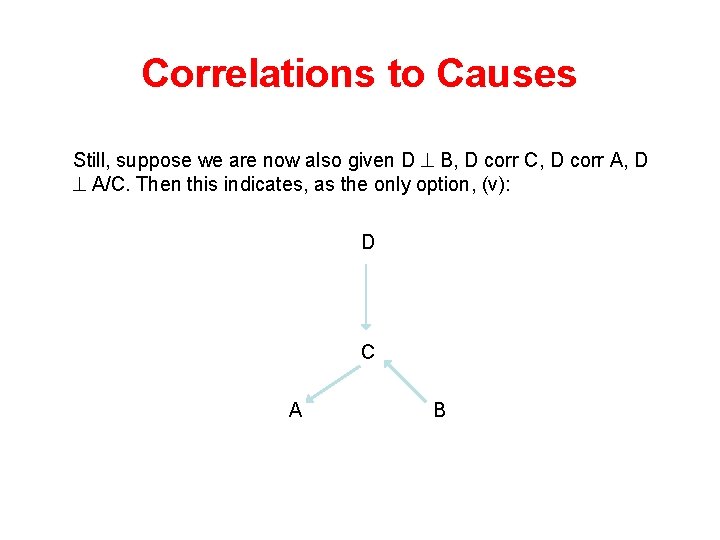

Correlations to Causes Still, suppose we are now also given D B, D corr C, D corr A, D A/C. Then this indicates, as the only option, (v): D C A B

Correlations to Causes Whenever the correlations don’t identify a unique causal structure—as here when “A corr B, A corr C, B corr C, A B/C” left us undecided between three possibilities—there will always be some wider set of possible variables the correlations between which will decide the causal relations between the original variables—as bringing in D showed us how A, B, C were related.

Hidden Common Causes Is the procedure sensitive to which variables we include “in our model”? Yes. If we omit a common cause of two variables we will draw the wrong conclusions. If we have A B, A corr C, B corr C, then this implies: A C B But in reality it may be A C D B With B not causing C.

Hidden Common Causes Still, once we have included all common causes in our model, then our inferences will be secure, and not overturned by including further variables. Intuitively, B can only be spuriously correlated with C if it is itself an effect of one of C’s true causes. (This point is crucial to survey research—we need to include all possible “confounders”, but not all other variables correlated with the effect whatsoever. )

Honesty and Faithfulness The assumptions driving these inferences are: (a) Causally unconnected events (neither causes the other and they have no common cause) are uncorrelated, and causally connected events are uncorrelated given the events than come between them. [Causal Markov condition] (b) There are no probabilistic independencies that aren’t implied by (a). [Faithfulness]

Honesty and Faithfulness In fact, we can simplify. What’s really doing the work is basically: (a’) Correlated events are causally connected. (Honesty – no misleading correlations) (b’) Causally connected events are correlated. (Faithfulness – no misleading independencies).

Hausman’s Neat Account This is enough for Dan Hausman’s neat account of casual order: Given a correlated A and B, A is a cause of B iff everything correlated with A is correlated with B, and something correlated with B isn’t correlated with A. (Basically the idea is that effects always have independent sources of variation. )

A Metaphysical Reduction Most philosophers think of the difference between causes and effects as somehow constituted independently of all this correlational stuff—with the fact that the exogenous causes are always probabilistically independent then being a happy accident that allows us to infer causes from correlations. But surely a better account is that this is what makes for the difference between causes and effects. It’s a reduction of causation. My position has the advantage of not positing a primitive asymmetry (exogenous variables are always probabilistically independent) that just happens to be connected to another primitive asymmetry (the causes always come before their effects).

A Metaphysical Reduction Judea Pearl and other computer scientists were surprised to discover that the arrows they were drawing to capture experts’ probability distributions seemed to coincide with casual arrows. Some of the statisticians found this embarrassing and wanted no part of the metaphysical notion of causation. But Pearl himself saw that the causal arrows were significant in ways that went beyond mere statistical correlation. We need to recognize them as distinctively causal, not least for the ways they matter to action and counterfactuals. So Pearl, against the other statisticians, wanted to insist we shouldn’t eliminate causal relationships in favour of correlations. But what seems to have been lost sight of in this debate is that we can resist elimination and still be reductionists. To say that causes are nothing more than (certain special) correlations is not to say that don’t exist and don’t have a distinctive importance. To repeat, if we are non-reductionist realists we face an awkward question to which we have no answer. Why do the statisticians’ arrows always coincide with the causal arrows? Why are event types probabilistically independent if and only if they are causally independent? Surely an answer to the question must hinge somehow on the nature of causation.

Honesty and Faithfulness Go back to the two assumptions. (a’) Correlated events are causally connected. (Honesty – no misleading correlations) (b’) Causally connected events are correlated. (Faithfulness – no misleading independencies) The first are threatened by Venice-water-level/Londonbread-price examples. The second are threatened by “failures of faithfulness”.

Venice-London Problems On Venice-London cases, I’d rule these out as not being real correlations in the terms of the act. We are interested in correlations between the different properties of units (some kind of objects (people, towns), or kind of groups of objects bearing certain specified spatiotemporal relationships to each other (married couples, towns on rivers)). We estimate the correlations by repeated sampling of units of these kinds, where the objects/groups units don’t have any systematic relationships to each other.

Venice-London Problems But this is violated by Venice-London examples. At first pass, our units are years, and the properties are water levels and bread prices. So far so good. But the different years sampled are successive, and this means we get a factitious correlation due to the separate probabilistic relationships between the levels, and the prices, in one year and the next. We should thus rule out correlations which are solely due to probabilistic dependencies between properties of different units.

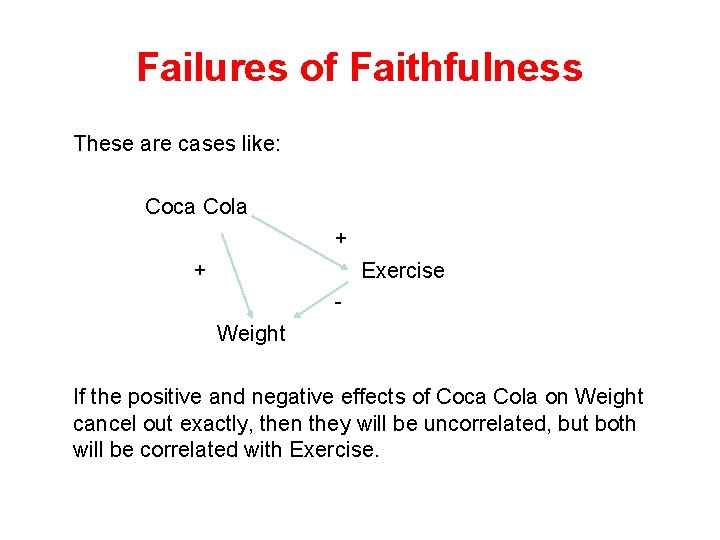

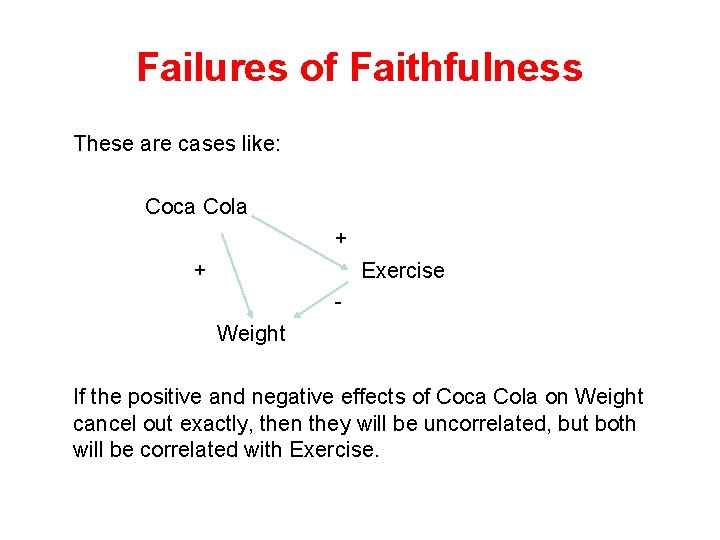

Failures of Faithfulness These are cases like: Coca Cola + + Exercise Weight If the positive and negative effects of Coca Cola on Weight cancel out exactly, then they will be uncorrelated, but both will be correlated with Exercise.

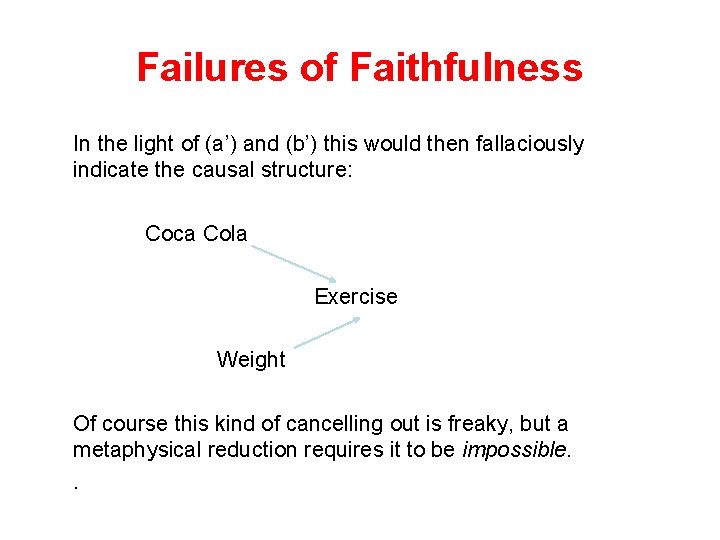

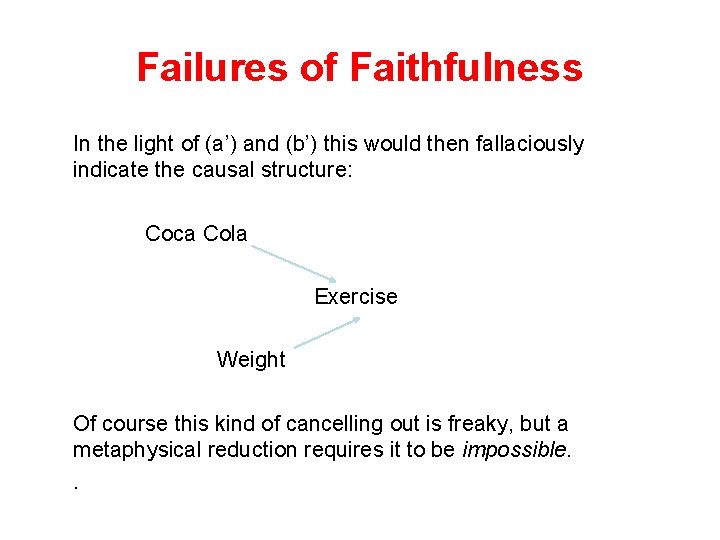

Failures of Faithfulness In the light of (a’) and (b’) this would then fallaciously indicate the causal structure: Coca Cola Exercise Weight Of course this kind of cancelling out is freaky, but a metaphysical reduction requires it to be impossible. .

Pseudo-Indeterminism At this point I’m inclined to look behind the correlational facts to something deeper. A natural explanation of the correlational facts is that they are an upshot of pseudo-indeterminism. Go back to the multivariate equations. If we assume that our statistical relationships result from deterministic equations of the form: E = a. C + E W = b. C + d. E + W then we can view the causal structure as being determined by the independence of the “error terms”, rather than the resulting correlations.

Pseudo-Indeterminism In most cases, these equations and the independence of the (unknown) s will determine correlations between the (known) causally connected Cs, Es, Ws etc. But in some funny cases the precise coefficients will lead to cancelling-out failures of faithfulness. Still, the underlying deterministic relationships and independent errors are still there to fix the right causal arrows, and it is metaphysically impossible, I say, for these underlying facts to come apart from the causal ones.

Conclusion So that is my reduction of causal asymmetry. It’s nothing over and above basic deterministic laws, probabilistic independencies, and the kinds of Cs, Es, Ws etc that enter into these deterministic laws.

The End