ENG 2003 Lecture 3 Morphology I 1 MORPHOLOGY

- Slides: 41

ENG 2003 Lecture 3 Morphology I 1

MORPHOLOGY • Morphology is the study of the structure of words • Many words can be divided into meaningful or recognizable subparts • These subparts are not necessarily words themselves 2

MORPHOLOGY For example, ‘friend’ can become: ‘friendly’ ‘unfriendly’ ‘friendliness’ ‘friendship’ ‘friendlessness’ ‘befriended’ ‘user-friendly’ ‘friends’ 학 can appear in the following words 대학교, 학생, 학원, 학습 (university, student, ‘hagwon’, study/learning) Such patterns can be found in almost all languages: Cree (Algonquian, central Canada) kâsihew – he cleans him kâsihwew – he purifies him kâsikwâniyagan – wash basin kâsik/kâsih – related to washing kâsihigan – eraser kâsikwâgan – face-cloth kâsikwew – he washes his face 3

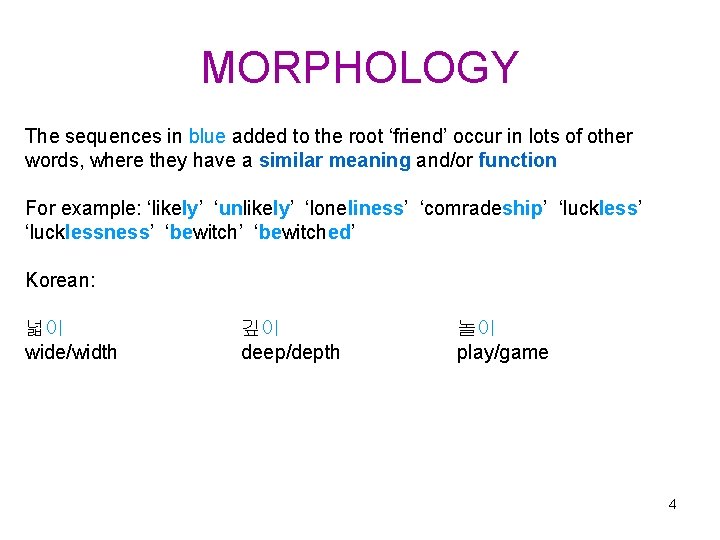

MORPHOLOGY The sequences in blue added to the root ‘friend’ occur in lots of other words, where they have a similar meaning and/or function For example: ‘likely’ ‘unlikely’ ‘loneliness’ ‘comradeship’ ‘lucklessness’ ‘bewitched’ Korean: 넓이 wide/width 깊이 deep/depth 놀이 play/game 4

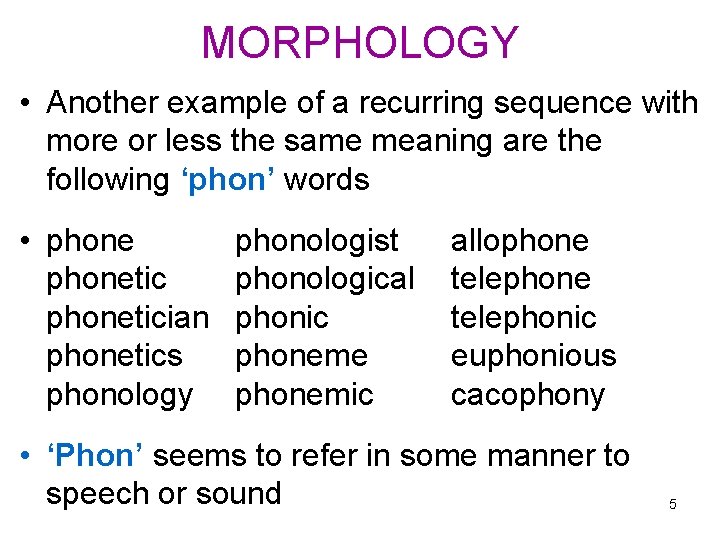

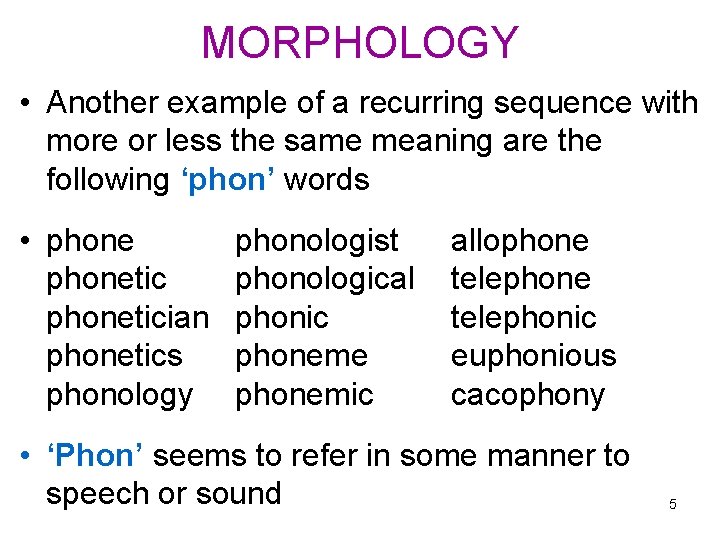

MORPHOLOGY • Another example of a recurring sequence with more or less the same meaning are the following ‘phon’ words • phonetician phonetics phonology phonologist phonological phonic phoneme phonemic allophone telephonic euphonious cacophony • ‘Phon’ seems to refer in some manner to speech or sound 5

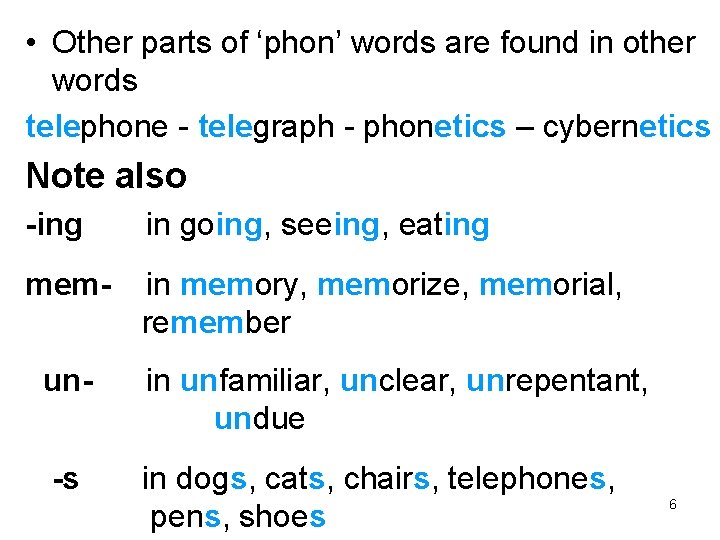

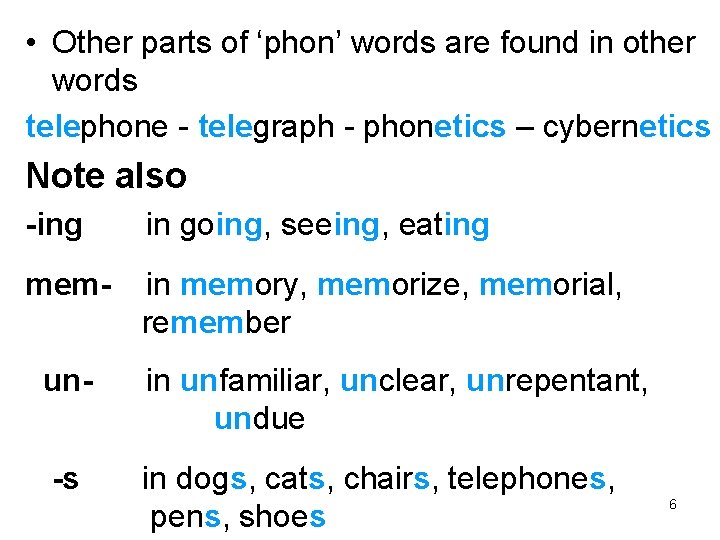

• Other parts of ‘phon’ words are found in other words telephone - telegraph - phonetics – cybernetics Note also -ing in going, seeing, eating mem- in memory, memorize, memorial, remember un- in unfamiliar, unclear, unrepentant, undue -s in dogs, cats, chairs, telephones, pens, shoes 6

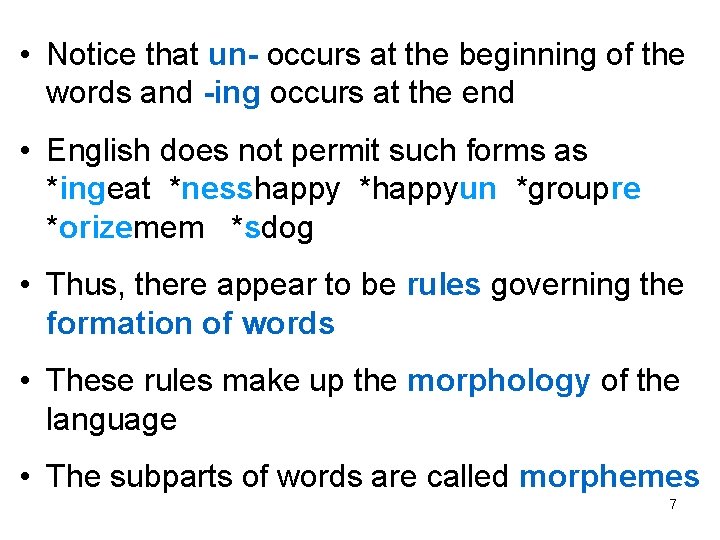

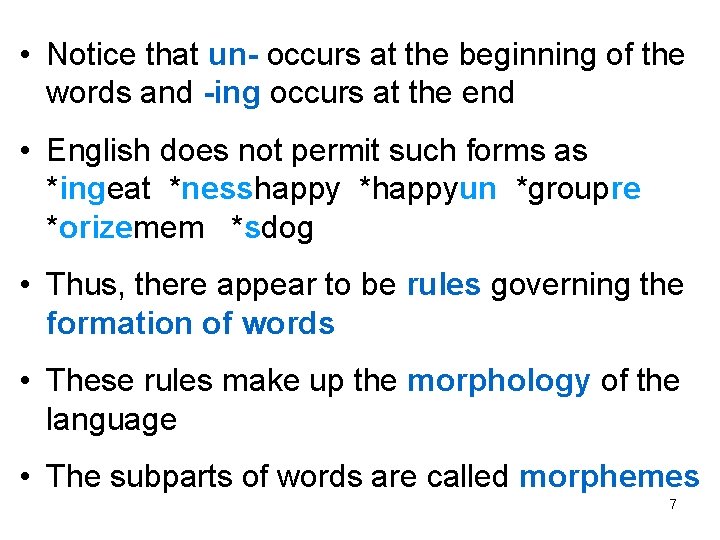

• Notice that un- occurs at the beginning of the words and -ing occurs at the end • English does not permit such forms as *ingeat *nesshappy *happyun *groupre *orizemem *sdog • Thus, there appear to be rules governing the formation of words • These rules make up the morphology of the language • The subparts of words are called morphemes 7

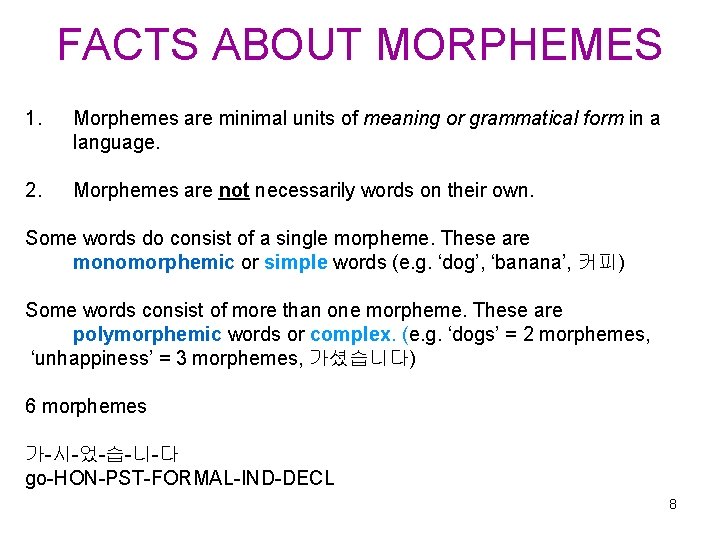

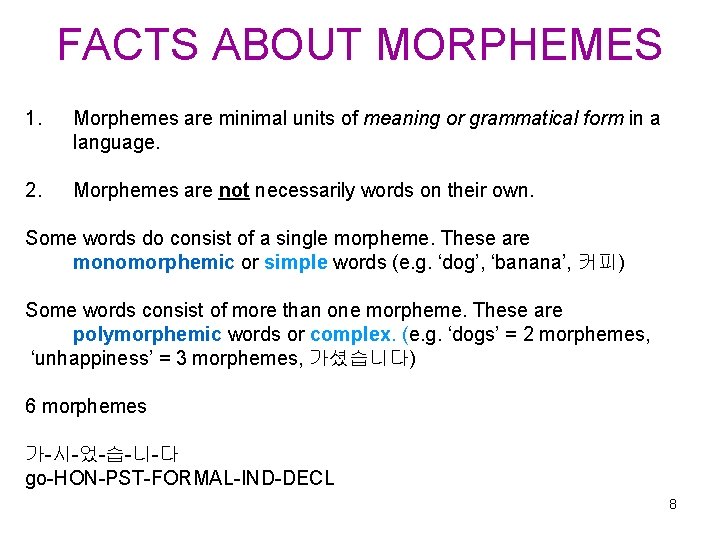

FACTS ABOUT MORPHEMES 1. Morphemes are minimal units of meaning or grammatical form in a language. 2. Morphemes are not necessarily words on their own. Some words do consist of a single morpheme. These are monomorphemic or simple words (e. g. ‘dog’, ‘banana’, 커피) Some words consist of more than one morpheme. These are polymorphemic words or complex. (e. g. ‘dogs’ = 2 morphemes, ‘unhappiness’ = 3 morphemes, 가셨습니다) 6 morphemes 가-시-었-습-니-다 go-HON-PST-FORMAL-IND-DECL 8

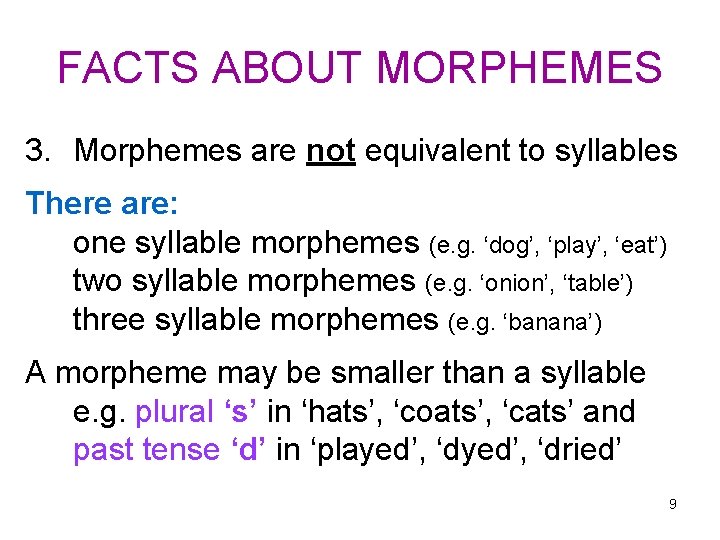

FACTS ABOUT MORPHEMES 3. Morphemes are not equivalent to syllables There are: one syllable morphemes (e. g. ‘dog’, ‘play’, ‘eat’) two syllable morphemes (e. g. ‘onion’, ‘table’) three syllable morphemes (e. g. ‘banana’) A morpheme may be smaller than a syllable e. g. plural ‘s’ in ‘hats’, ‘coats’, ‘cats’ and past tense ‘d’ in ‘played’, ‘dried’ 9

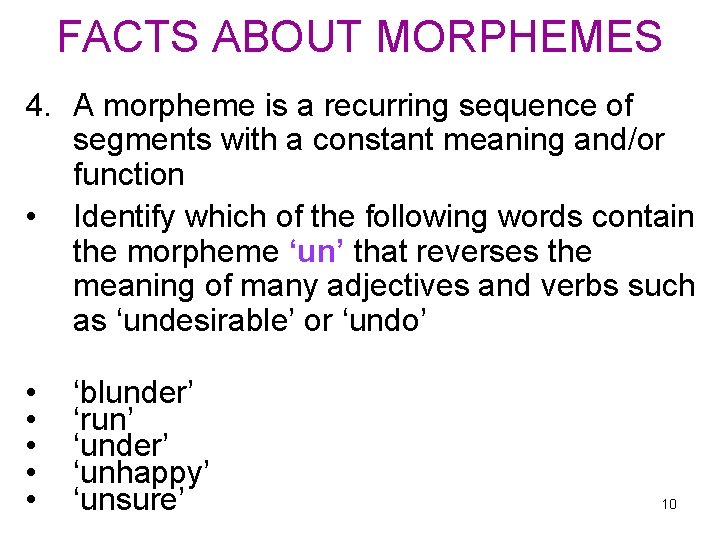

FACTS ABOUT MORPHEMES 4. A morpheme is a recurring sequence of segments with a constant meaning and/or function • Identify which of the following words contain the morpheme ‘un’ that reverses the meaning of many adjectives and verbs such as ‘undesirable’ or ‘undo’ • • • ‘blunder’ ‘run’ ‘under’ ‘unhappy’ ‘unsure’ 10

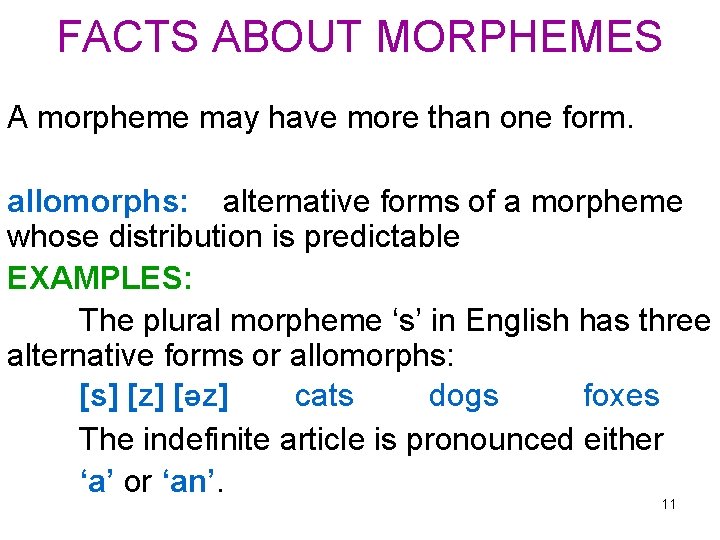

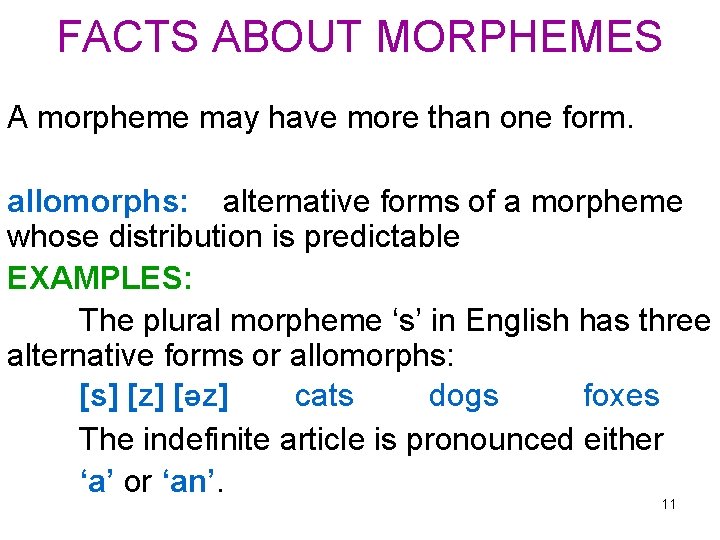

FACTS ABOUT MORPHEMES A morpheme may have more than one form. allomorphs: alternative forms of a morpheme whose distribution is predictable EXAMPLES: The plural morpheme ‘s’ in English has three alternative forms or allomorphs: [s] [z] [ z] cats dogs foxes The indefinite article is pronounced either ‘a’ or ‘an’. 11

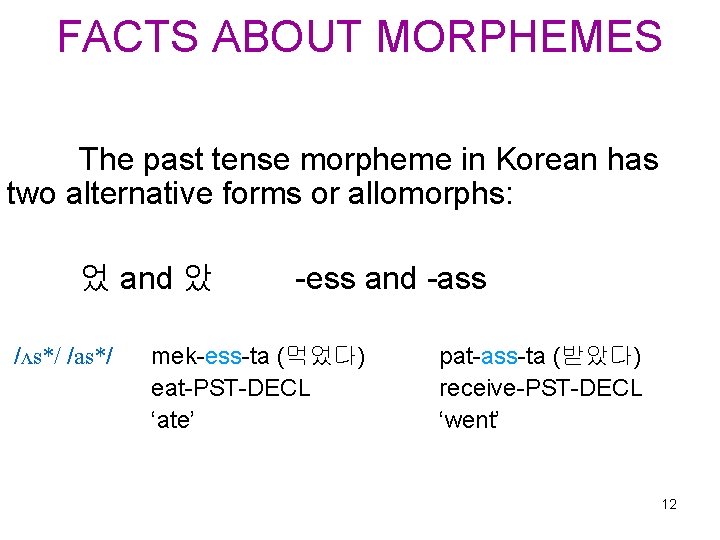

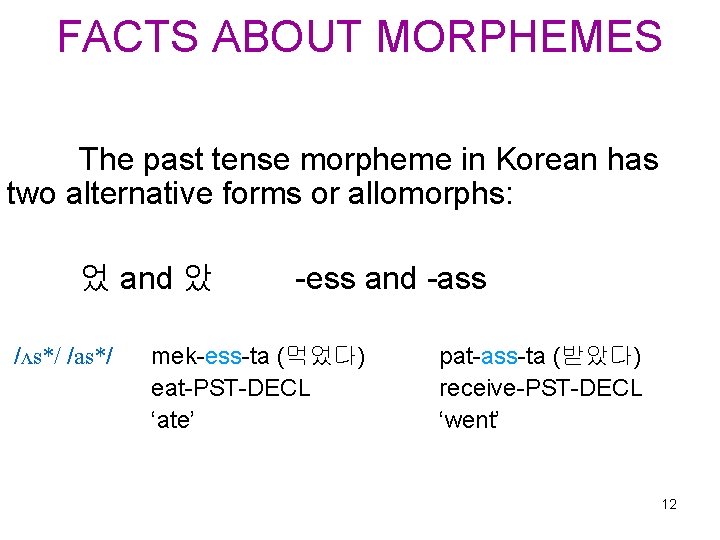

FACTS ABOUT MORPHEMES The past tense morpheme in Korean has two alternative forms or allomorphs: 었 and 았 /ʌs*/ /as*/ -ess and -ass mek-ess-ta (먹었다) eat-PST-DECL ‘ate’ pat-ass-ta (받았다) receive-PST-DECL ‘went’ 12

Spelling Variants A morpheme can have two or more spellings in English. If the pronunciation remains the same, these are not considered allomorphs of one another. They are simply spelling variants of the same one morpheme. For example: -or in translator and -er in teacher are spelling variants. 13

CATEGORIES OF MORPHEMES • Distributionally, morphemes are of two general types: Free or Bound Morphemes Free morphemes • free morphemes can stand alone as simple words Example: ‘dog’, ‘house’, ‘run’, ‘banana’, ‘table’, ‘it’, ‘on’ • English has many free morphemes • some languages have very few free morphemes 14

CATEGORIES OF MORPHEMES Bound morphemes • bound morphemes cannot stand alone as words • they must be attached to at least one other morpheme before they can occur in an actual utterance • Examples: -English plural ‘s’ -past tense ‘ed’/었/았 • Languages differ from one another in what concepts they encode as free or bound. 15

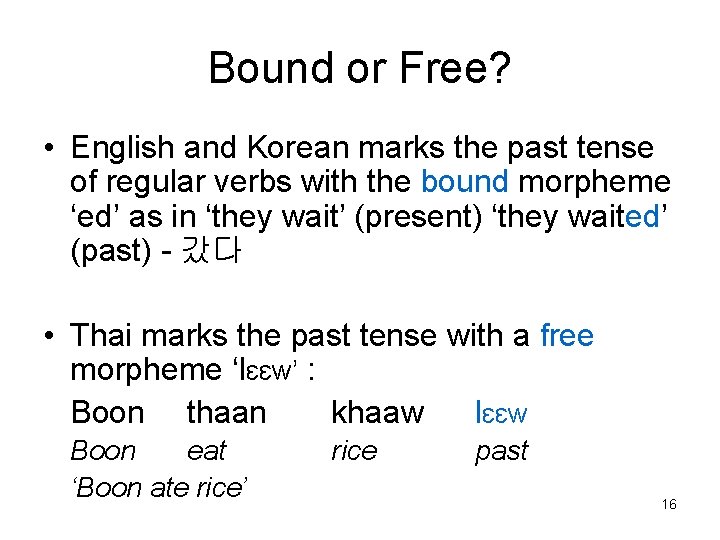

Bound or Free? • English and Korean marks the past tense of regular verbs with the bound morpheme ‘ed’ as in ‘they wait’ (present) ‘they waited’ (past) - 갔다 • Thai marks the past tense with a free morpheme ‘lɛɛw’ : Boon thaan khaaw lɛɛw Boon eat ‘Boon ate rice’ rice past 16

CATEGORIES OF MORPHEMES Affixes and Roots • as parts of words, morphemes can be affixes or roots • Roots serve as the lexical core of words • Roots provide the primary meaning of words • Affixes are added to roots (or bases) and modify the meaning and/or function of a root 17

Roots and Bases • Root refers to the lexical core of a word. • Base refers to a form that an affix is added to. • Of course affixes can be added to roots. In such cases the root and the base are the same. • Affixes can also be added to a unit larger than a root. • Thus a base may also consist of a root plus another affix or affixes. [affix-[root-affix]]-affix 18

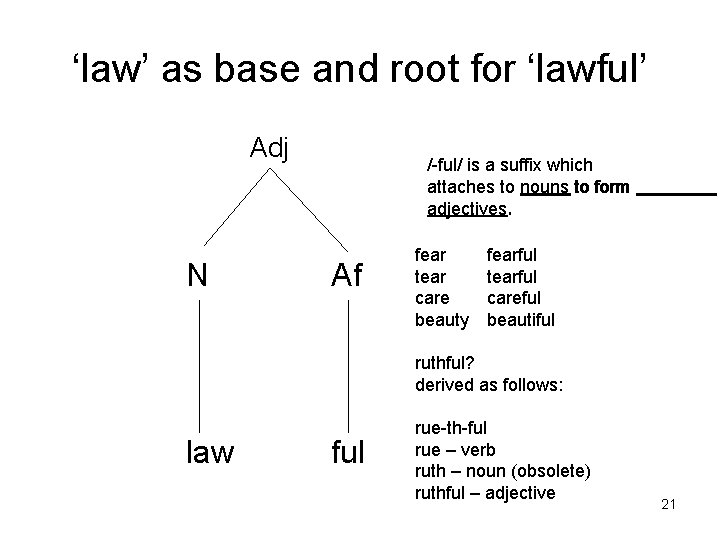

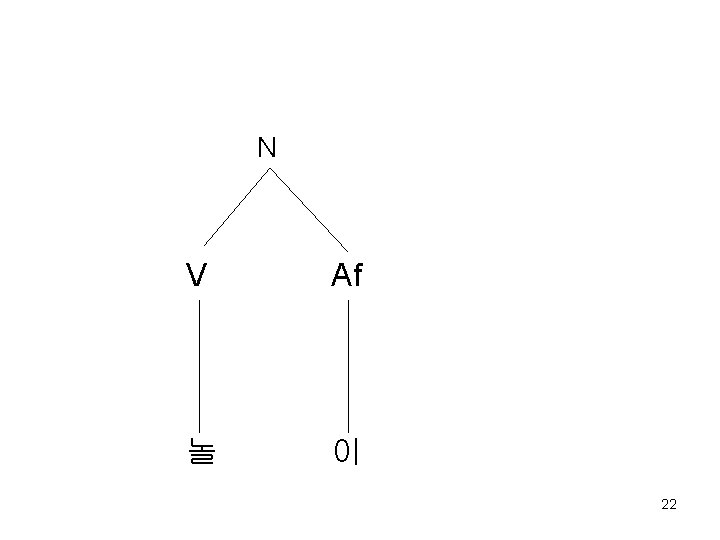

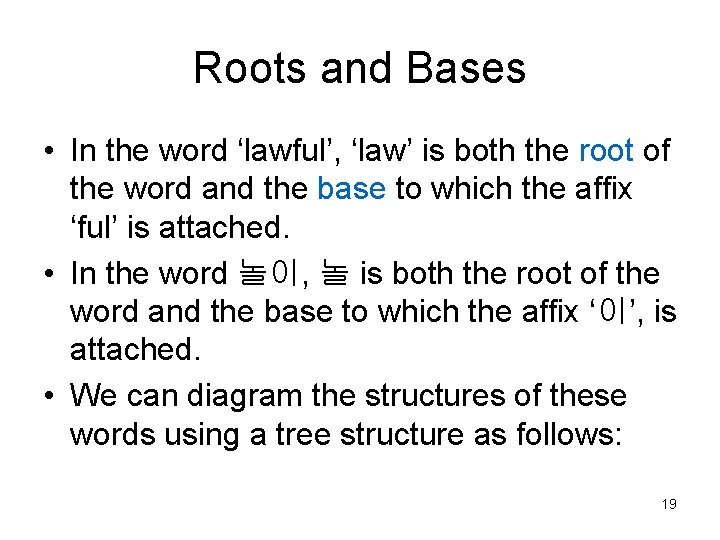

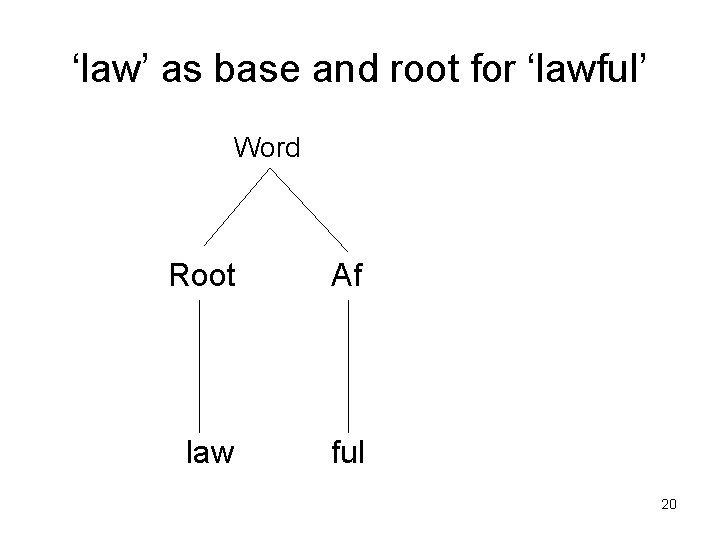

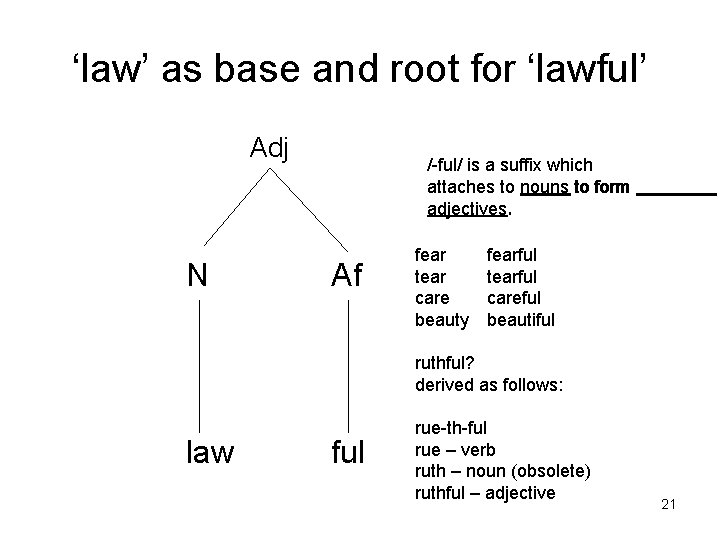

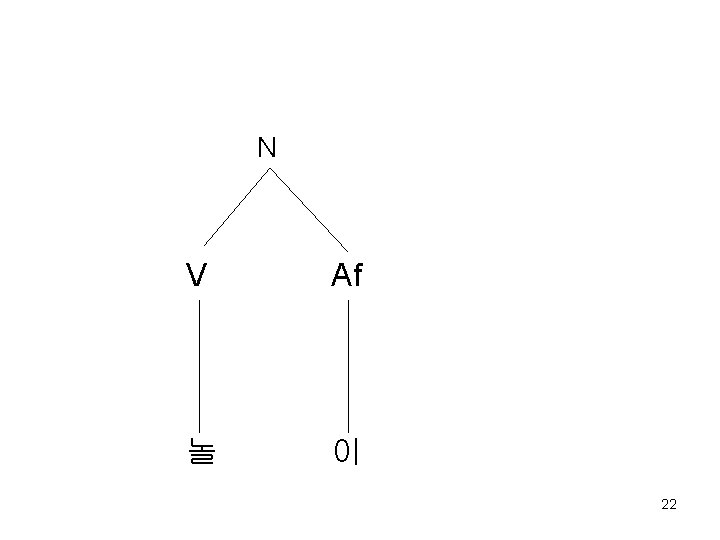

Roots and Bases • In the word ‘lawful’, ‘law’ is both the root of the word and the base to which the affix ‘ful’ is attached. • In the word 놀이, 놀 is both the root of the word and the base to which the affix ‘이’, is attached. • We can diagram the structures of these words using a tree structure as follows: 19

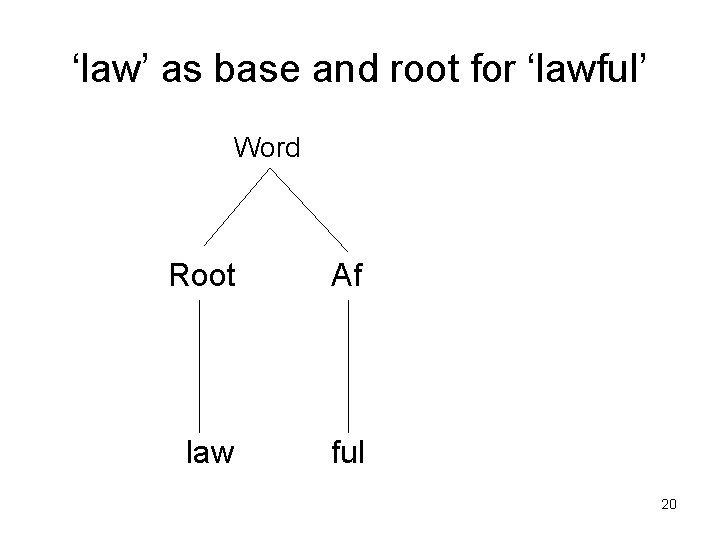

‘law’ as base and root for ‘lawful’ Word Root Af law ful 20

‘law’ as base and root for ‘lawful’ Adj N /-ful/ is a suffix which attaches to nouns to form adjectives. . Af fear tear care beauty fearful tearful careful beautiful ruthful? derived as follows: law ful rue-th-ful rue – verb ruth – noun (obsolete) ruthful – adjective 21

N V Af 놀 이 22

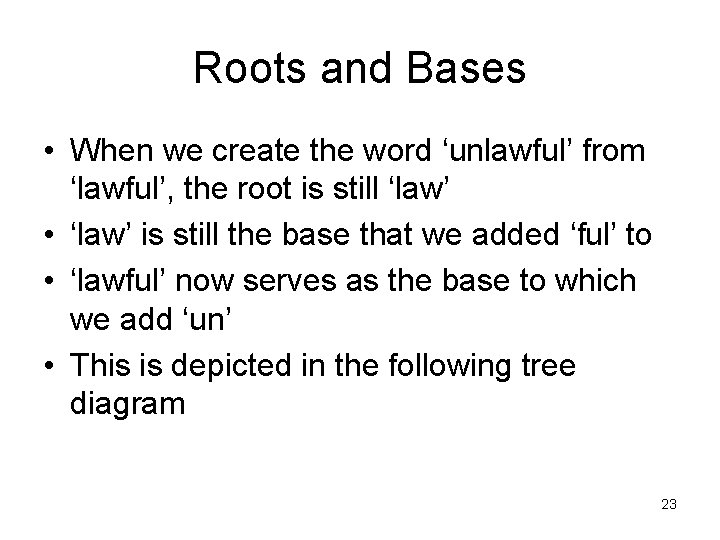

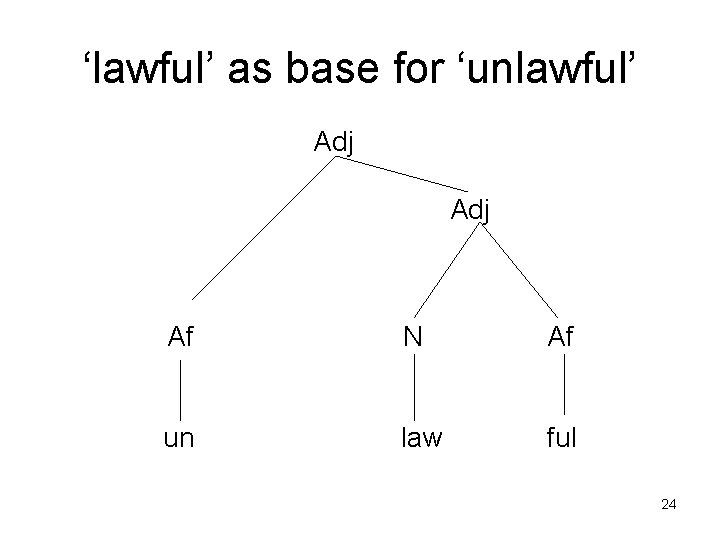

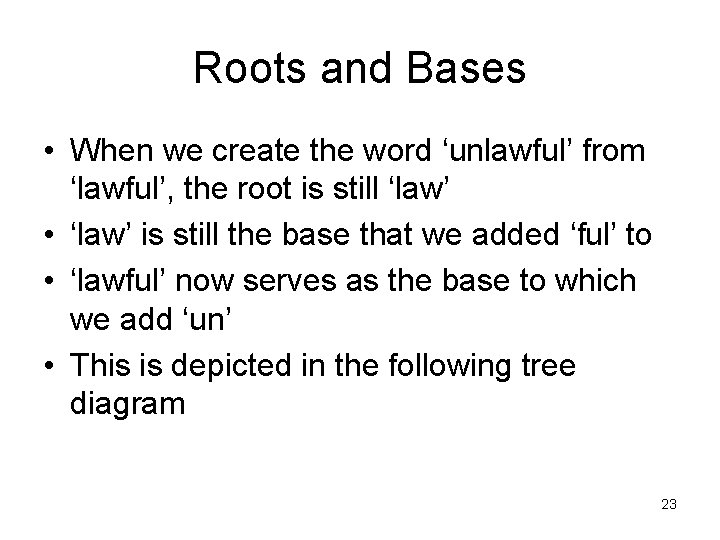

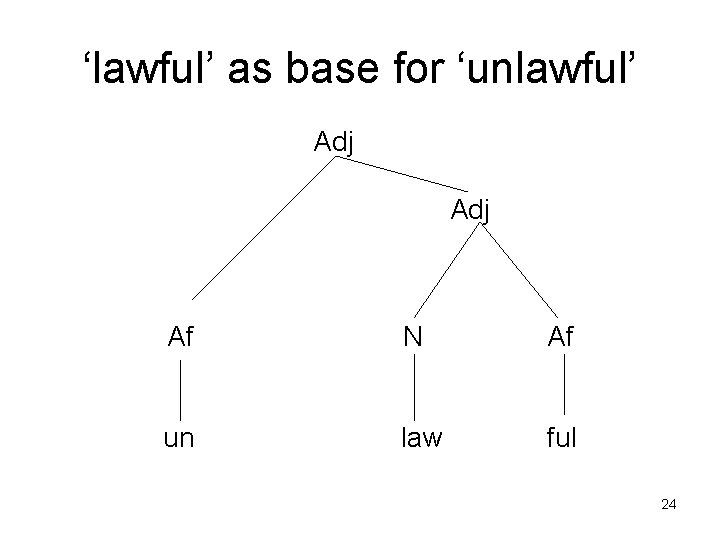

Roots and Bases • When we create the word ‘unlawful’ from ‘lawful’, the root is still ‘law’ • ‘law’ is still the base that we added ‘ful’ to • ‘lawful’ now serves as the base to which we add ‘un’ • This is depicted in the following tree diagram 23

‘lawful’ as base for ‘unlawful’ Adj Af N Af un law ful 24

Labeling word trees • Note that we label the nodes in tree diagrams according to the parts of speech of the root and the new words created by adding affixes to the root. • Thus ‘law’ is N for noun • ‘lawful’ is Adj for adjective • ‘unlawful’ is Adj for adjective 25

unlawful • In the word ‘unlawful’, the root law provides the core meaning of the word. • ‘ful’ is an affix that changes ‘law’ from a noun to an adjective • ‘un’ is an affix which reverses the meaning of ‘lawful’ • This gives us a hint as to the function of some types of affixes. 26

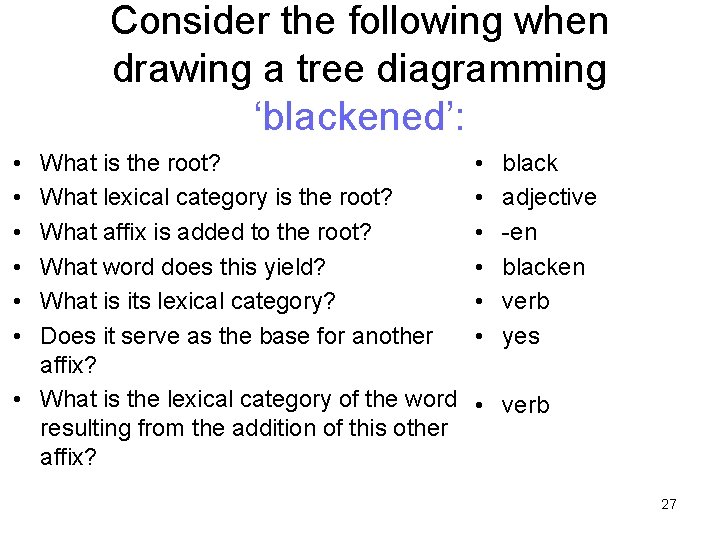

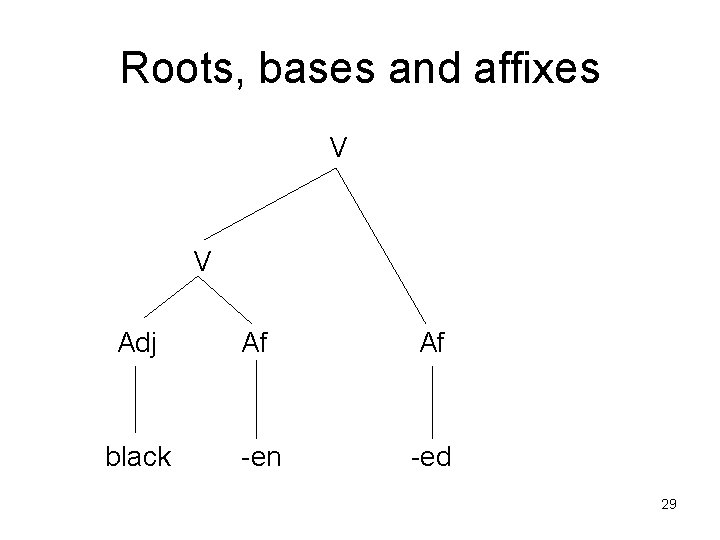

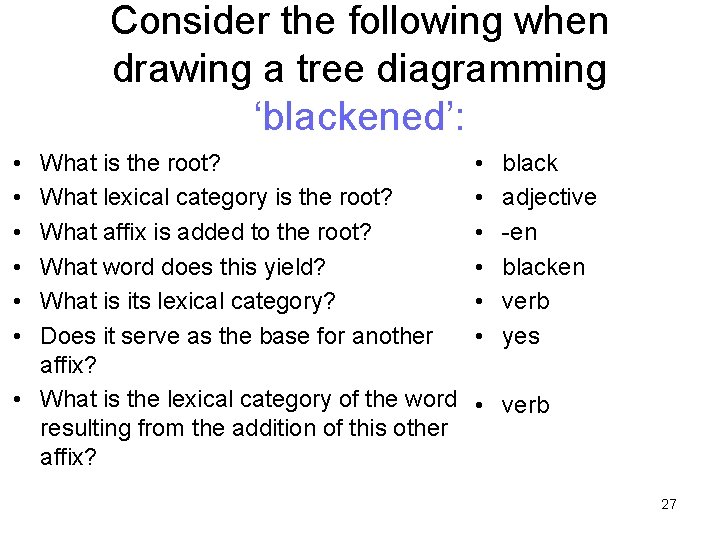

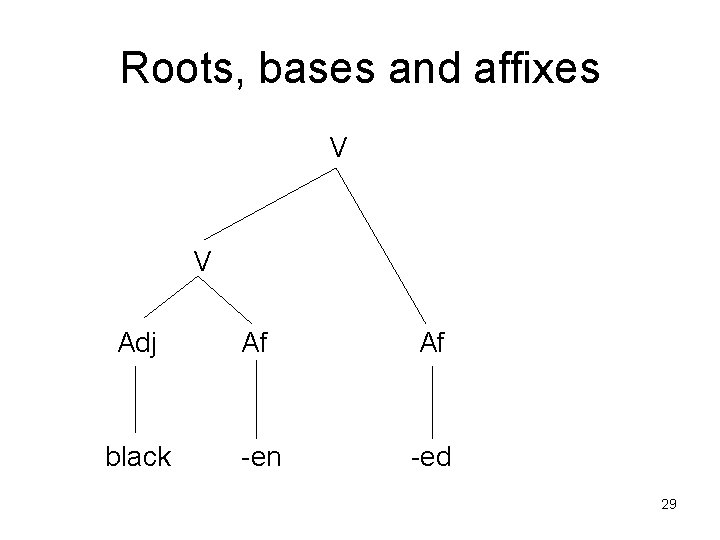

Consider the following when drawing a tree diagramming ‘blackened’: • • • What is the root? What lexical category is the root? What affix is added to the root? What word does this yield? What is its lexical category? Does it serve as the base for another affix? • What is the lexical category of the word resulting from the addition of this other affix? • • • black adjective -en blacken verb yes • verb 27

blackened • The adjective ‘black’ is the root (and base) to which we add the suffix ‘en’ • ‘black + -en’ is a verb. • The verb ‘blacken’ is the base to which we add the suffix ‘-ed’. • ‘blackened’ is still a verb, as the suffix ‘-ed’ does not change the part of speech of the base. 28

Roots, bases and affixes V V Adj Af Af black -en -ed 29

AFFIXES • Positionally, there are four types of affixes: 1. Prefixes 2. Suffixes 3. Infixes (and Triconsonantal Roots) 4. Circumfixes 1. Prefixes appear before the root, as in ‘redo’ 2. Suffixes appear after the root, as in ‘reader’ 30

AFFIXES • In many languages, a word can have more than one prefix or suffix. • English example: ‘helplessness’ • Noun (N) base/root ‘help’ + suffix ‘less’ to yield the adjective ‘helpless’ • ‘helpless’ serves as the base for the suffix ‘ness’ to yield the noun (N) ‘helplessness’ 31

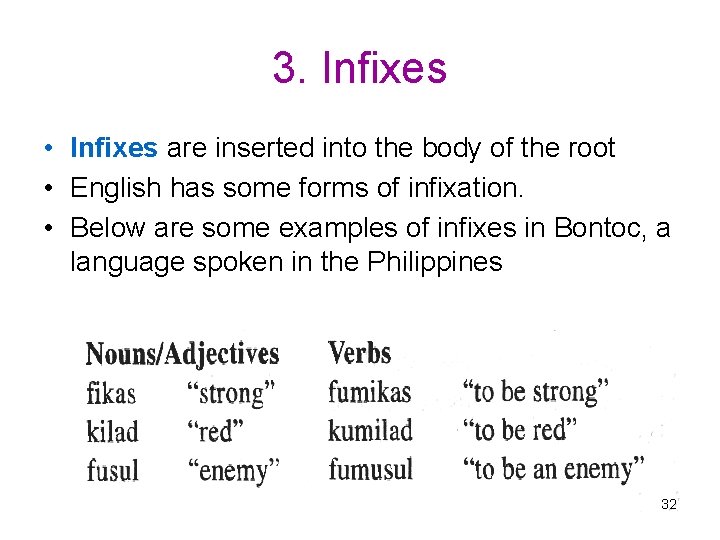

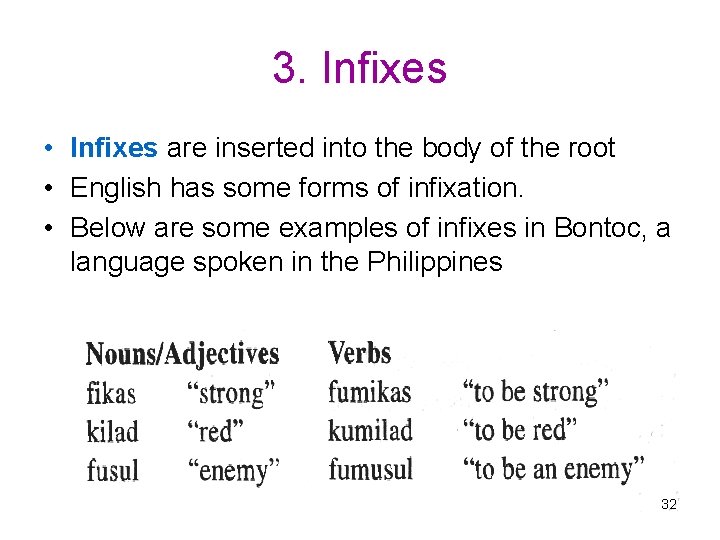

3. Infixes • Infixes are inserted into the body of the root • English has some forms of infixation. • Below are some examples of infixes in Bontoc, a language spoken in the Philippines 32

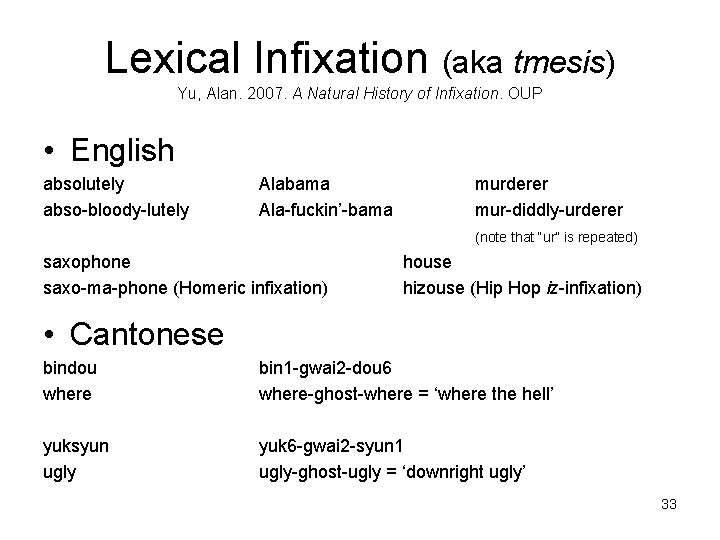

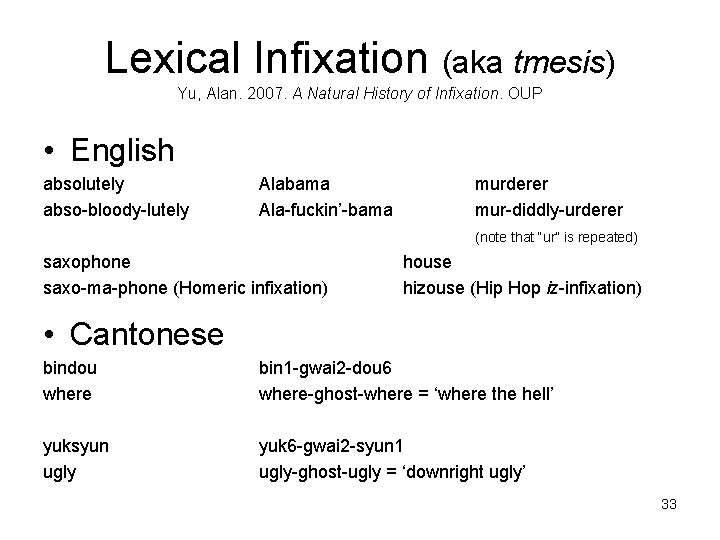

Lexical Infixation (aka tmesis) Yu, Alan. 2007. A Natural History of Infixation. OUP • English absolutely abso-bloody-lutely Alabama Ala-fuckin’-bama murderer mur-diddly-urderer (note that “ur” is repeated) saxophone saxo-ma-phone (Homeric infixation) house hizouse (Hip Hop iz-infixation) • Cantonese bindou where bin 1 -gwai 2 -dou 6 where-ghost-where = ‘where the hell’ yuksyun ugly yuk 6 -gwai 2 -syun 1 ugly-ghost-ugly = ‘downright ugly’ 33

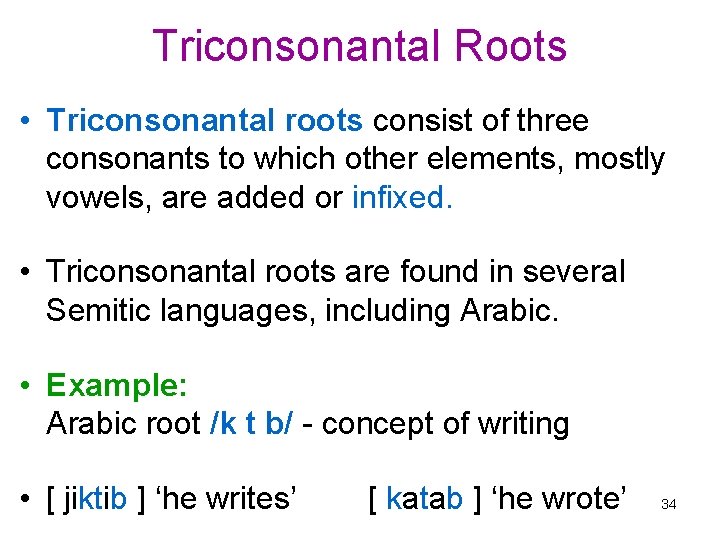

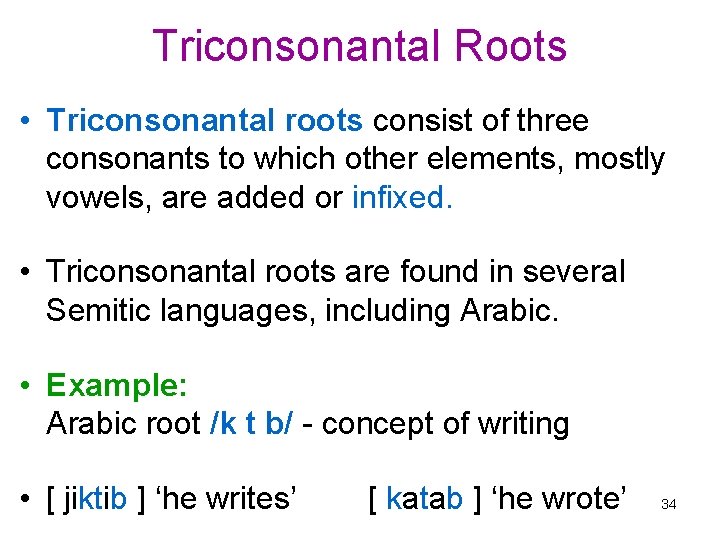

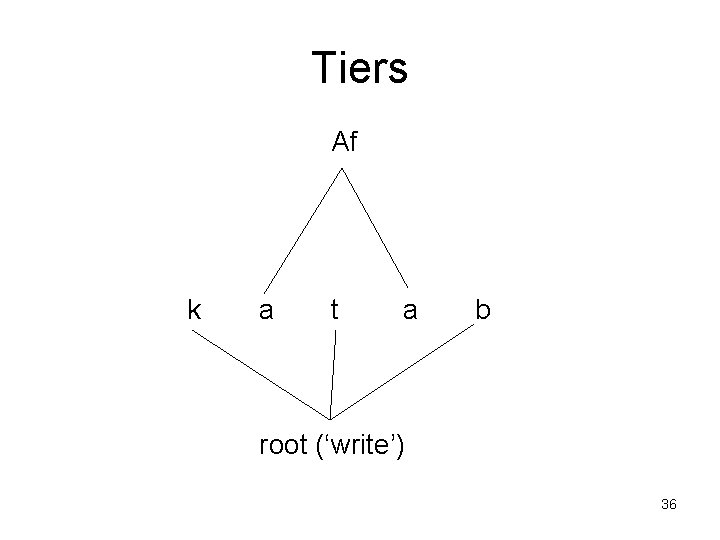

Triconsonantal Roots • Triconsonantal roots consist of three consonants to which other elements, mostly vowels, are added or infixed. • Triconsonantal roots are found in several Semitic languages, including Arabic. • Example: Arabic root /k t b/ - concept of writing • [ jiktib ] ‘he writes’ [ katab ] ‘he wrote’ 34

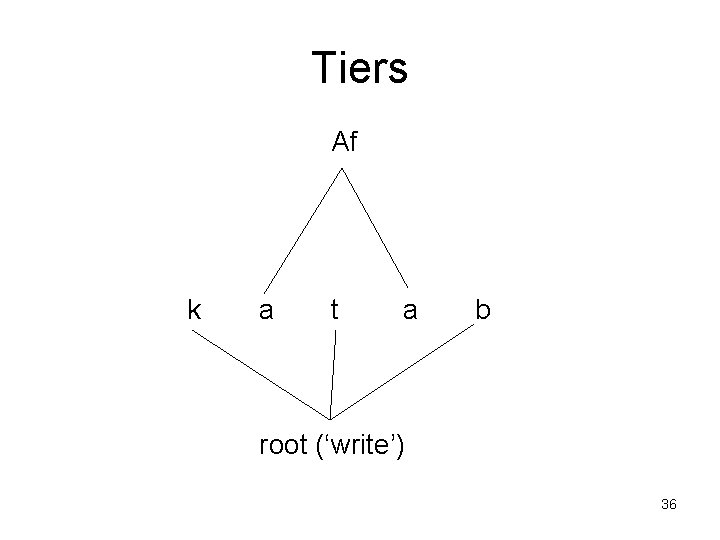

Tiers • The word structure of languages with triconsonantal roots are sometimes depicted in terms of tiers, rather than with tree diagrams. 35

Tiers Af k a t a b root (‘write’) 36

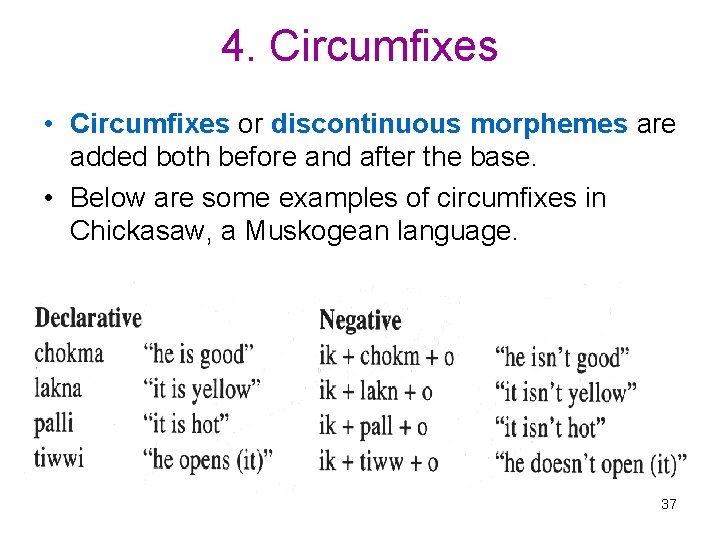

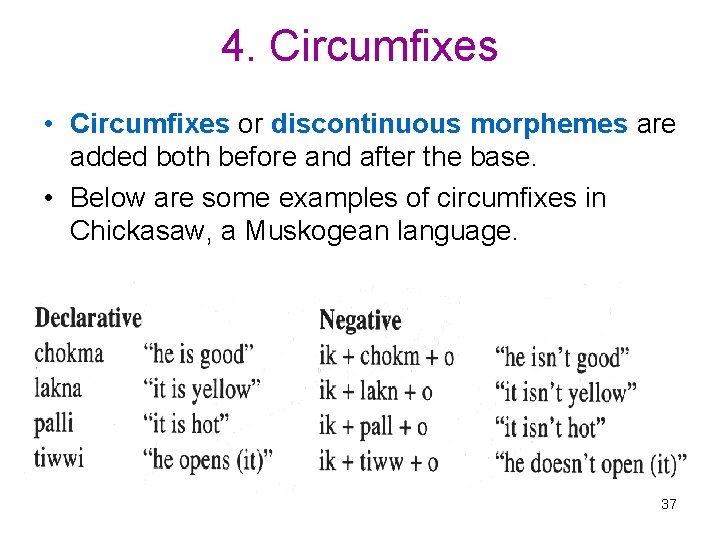

4. Circumfixes • Circumfixes or discontinuous morphemes are added both before and after the base. • Below are some examples of circumfixes in Chickasaw, a Muskogean language. 37

CIRCUMFIXES German also has circumfixes or discontinuous morphemes lieb ‘love’ verb root geliebt ‘loved’ or ‘be loved’ 38

CATEGORIES OF MORPHEMES • All affixes are, by definition, bound • That is, they always occur attached to another morpheme • In many languages, most of the roots are bound as well • That is, the grammar requires attaching some type of affix to them before they can be uttered as grammatical words • In English, most roots are also free morphemes or stand-alone words 39

BOUND ROOTS IN ENGLISH • There a few so-called bound roots in English They include: ‘ceive’ as in ‘deceive’, ‘receive’, ‘conceive’, ‘perceive’ ‘tract’ as in ‘retract’, ‘detract’, ‘contract’ ‘spire’ as in ‘inspire’, ‘conspire’, ‘perspire’ ‘pris’ as in ‘reprisal’, ‘enterprise’ ‘gust’ as in ‘disgust’, ‘gustatory’ ‘gusto’ 40

BOUND ROOTS IN ENGLISH • The ‘ceive’ words show a regular pattern. • For example, they have unique ‘cept’ allomorphs as in: • ‘receive’ ‘reception’ • ‘deceive’ ‘deception’ • This is evidence in favour of the reality of bound roots, although further research is pending. 41