Dependent Plurals and Three Levels of Multiplicity Serge

- Slides: 71

Dependent Plurals and Three Levels of Multiplicity Serge Minor CASTL, University of Tromsø HSE Seminar Moscow, 11. 04. 2019

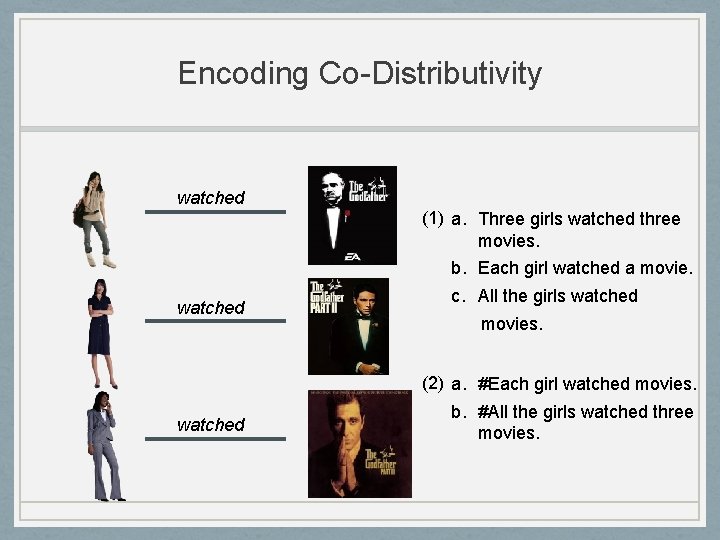

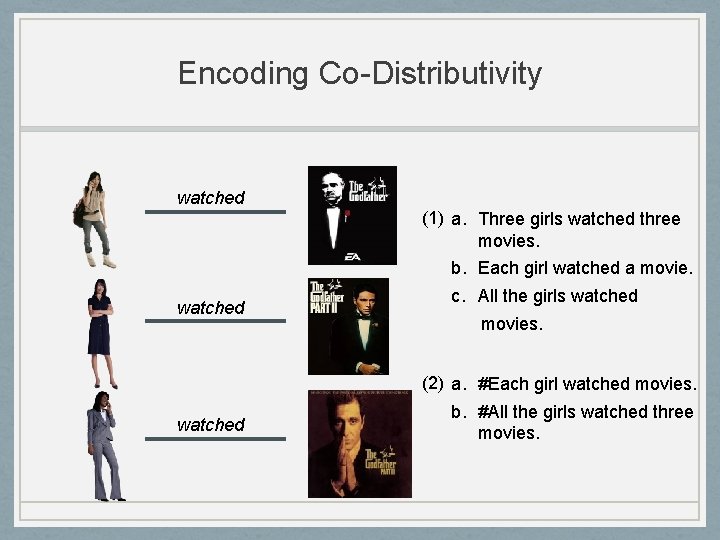

Encoding Co-Distributivity watched (1) a. Three girls watched three movies. watched b. Each girl watched a movie. c. All the girls watched movies. (2) a. #Each girl watched movies. watched b. #All the girls watched three movies.

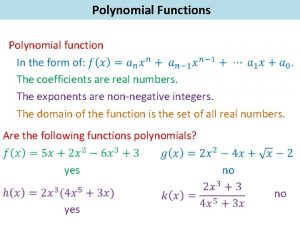

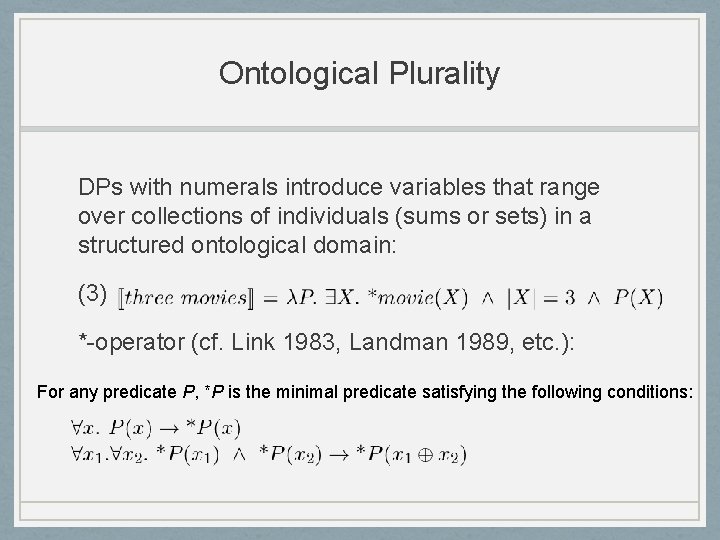

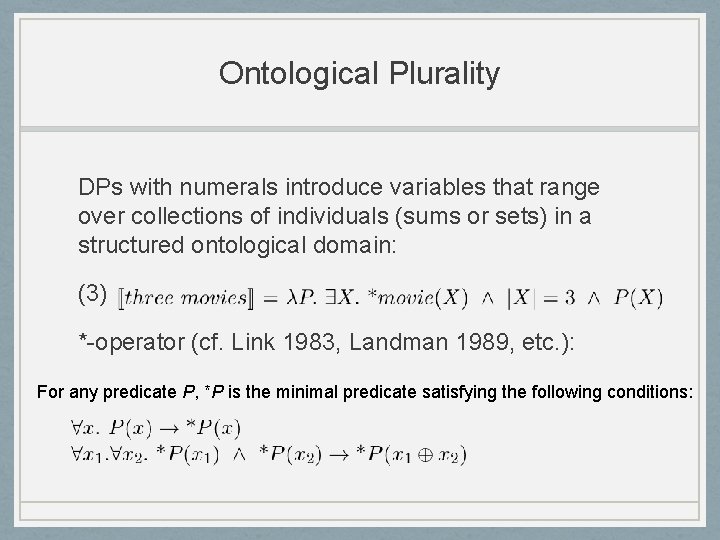

Ontological Plurality DPs with numerals introduce variables that range over collections of individuals (sums or sets) in a structured ontological domain: (3) *-operator (cf. Link 1983, Landman 1989, etc. ): For any predicate P, *P is the minimal predicate satisfying the following conditions:

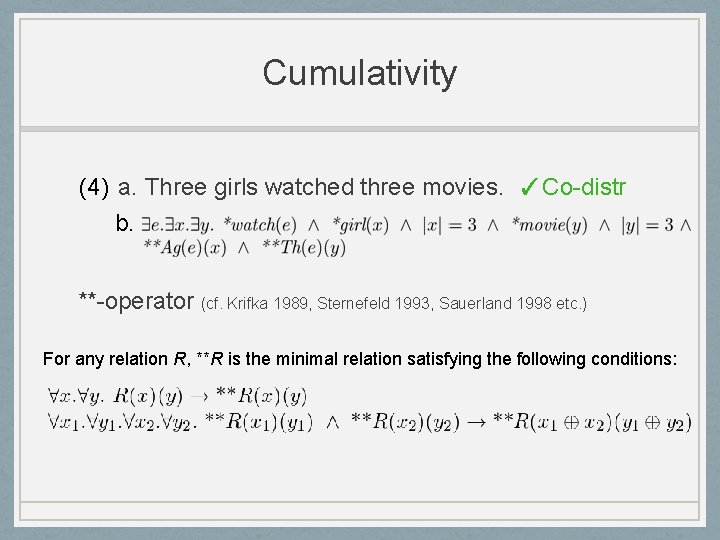

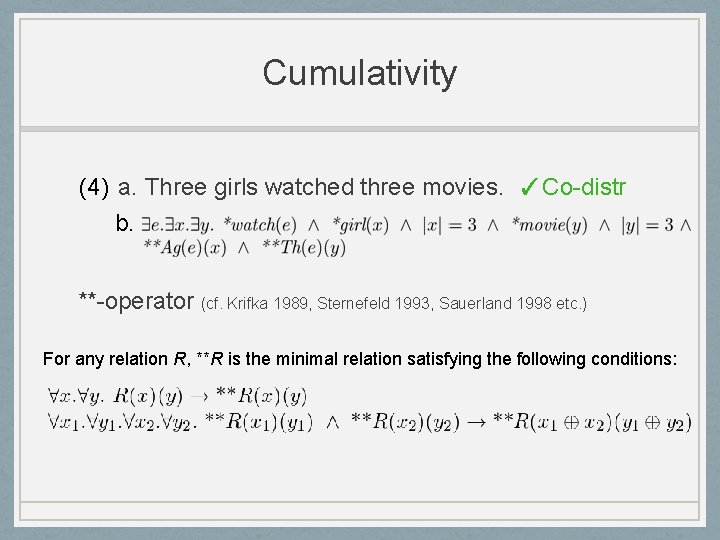

Cumulativity (4) a. Three girls watched three movies. ✓Co-distr b. **-operator (cf. Krifka 1989, Sternefeld 1993, Sauerland 1998 etc. ) For any relation R, **R is the minimal relation satisfying the following conditions:

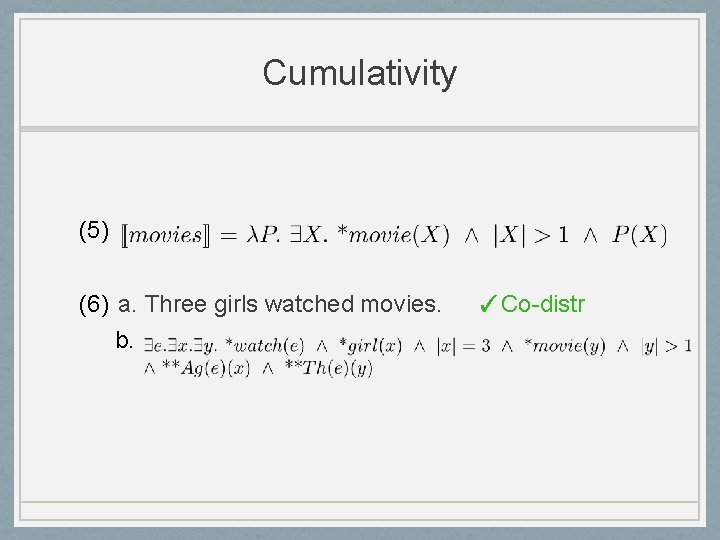

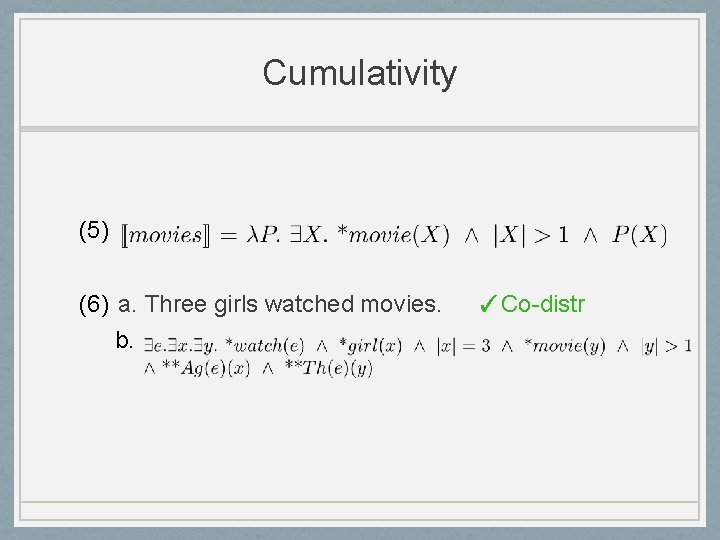

Cumulativity (5) (6) a. Three girls watched movies. b. ✓Co-distr

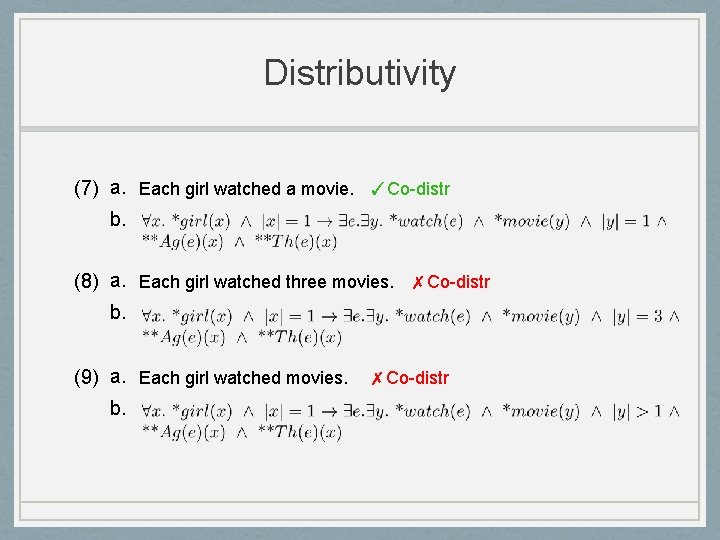

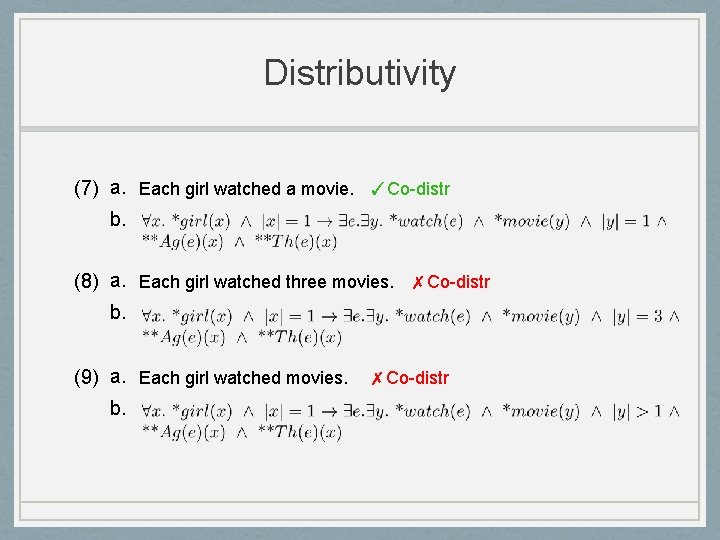

Distributivity (7) a. Each girl watched a movie. ✓Co-distr b. (8) a. Each girl watched three movies. ✗Co-distr b. (9) a. Each girl watched movies. b. ✗Co-distr

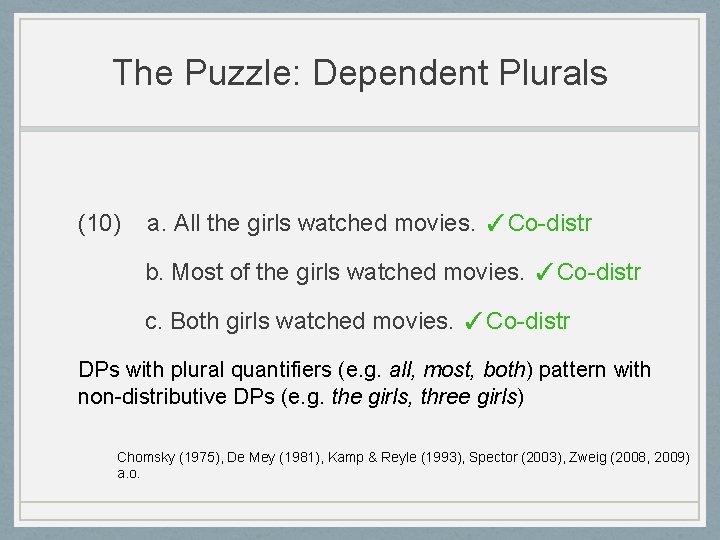

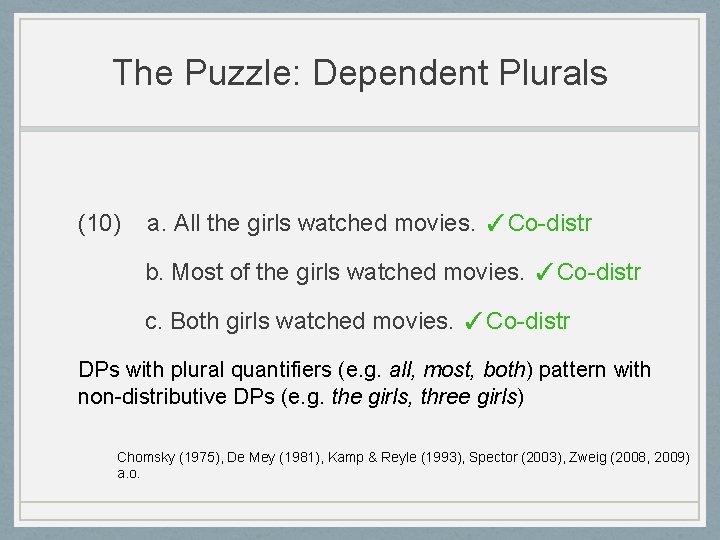

The Puzzle: Dependent Plurals (10) a. All the girls watched movies. ✓Co-distr b. Most of the girls watched movies. ✓Co-distr c. Both girls watched movies. ✓Co-distr DPs with plural quantifiers (e. g. all, most, both) pattern with non-distributive DPs (e. g. the girls, three girls) Chomsky (1975), De Mey (1981), Kamp & Reyle (1993), Spector (2003), Zweig (2008, 2009) a. o.

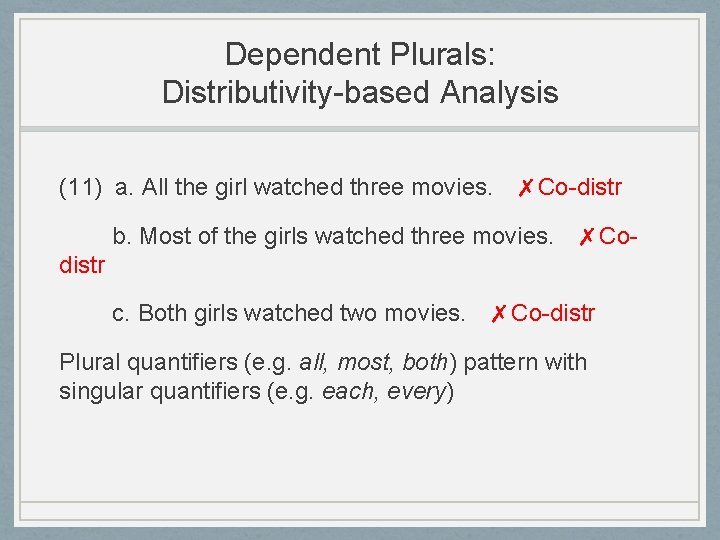

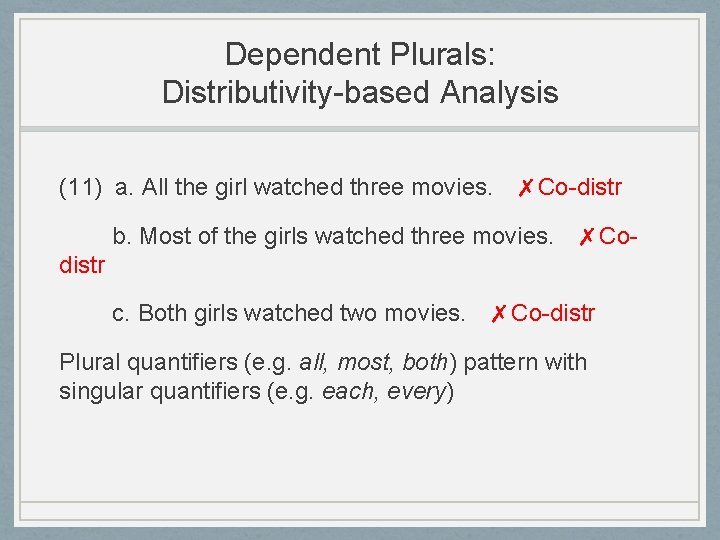

Dependent Plurals: Distributivity-based Analysis (11) a. All the girl watched three movies. ✗Co-distr b. Most of the girls watched three movies. ✗Codistr c. Both girls watched two movies. ✗Co-distr Plural quantifiers (e. g. all, most, both) pattern with singular quantifiers (e. g. each, every)

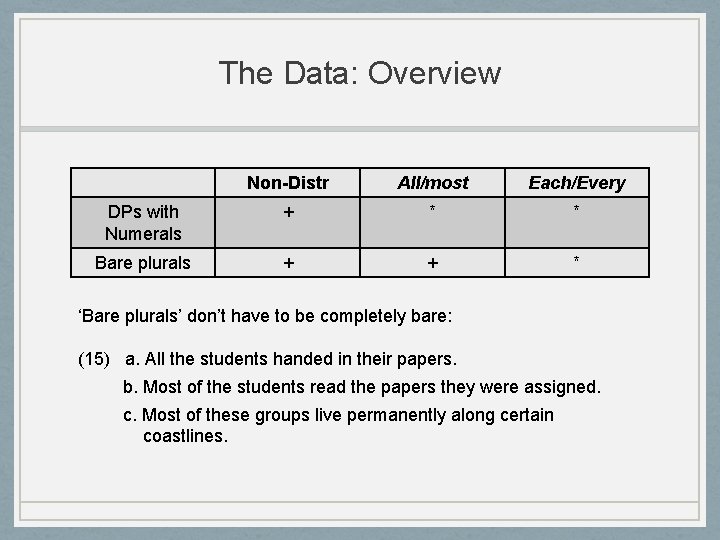

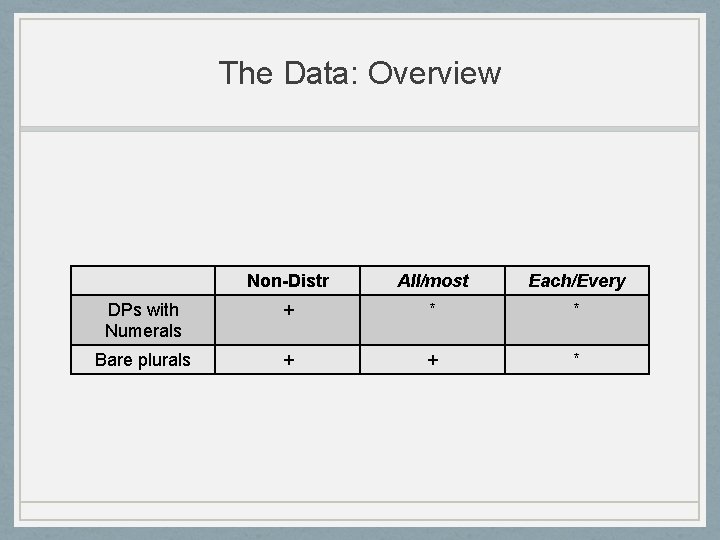

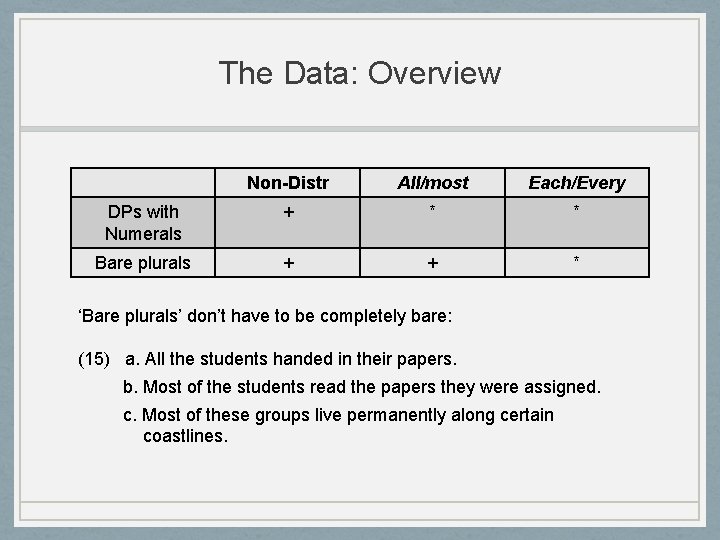

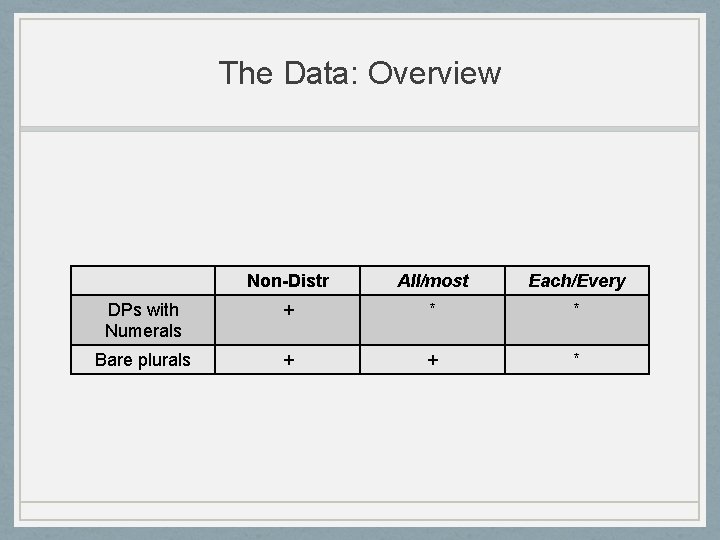

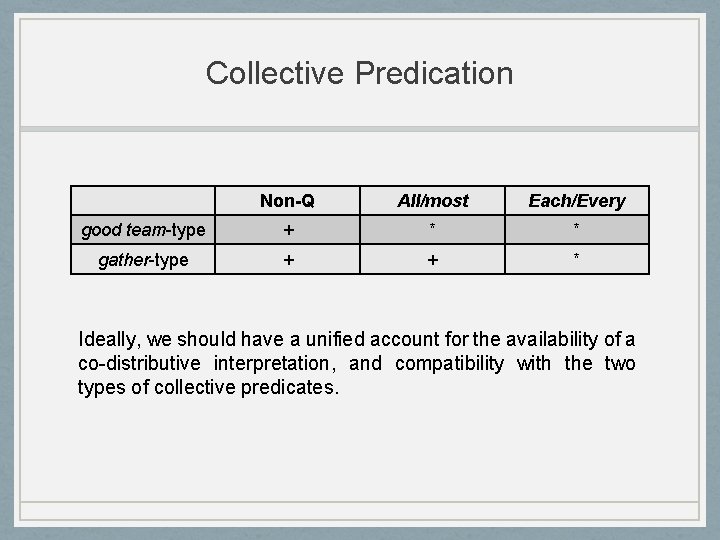

The Data: Overview Non-Distr All/most Each/Every DPs with Numerals + * * Bare plurals + + * ‘Bare plurals’ don’t have to be completely bare: (15) a. All the students handed in their papers. b. Most of the students read the papers they were assigned. c. Most of these groups live permanently along certain coastlines.

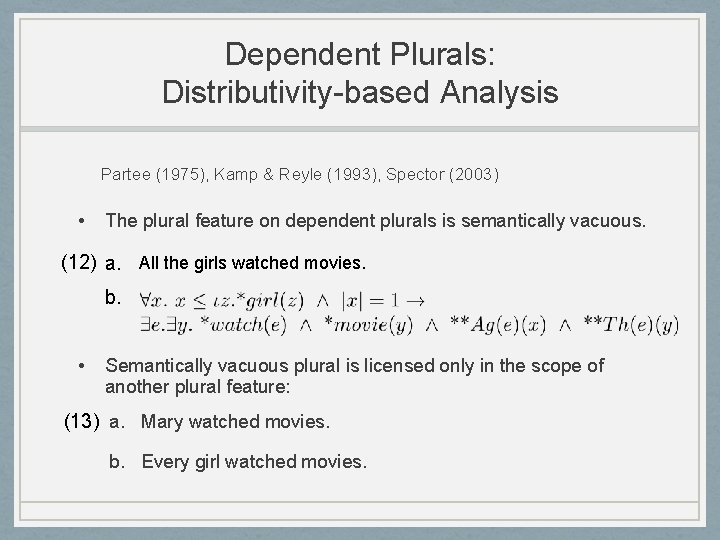

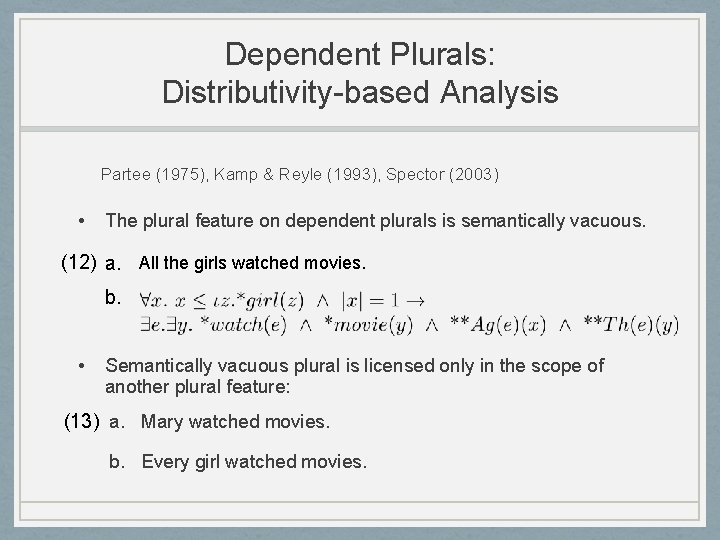

Dependent Plurals: Distributivity-based Analysis Partee (1975), Kamp & Reyle (1993), Spector (2003) • The plural feature on dependent plurals is semantically vacuous. (12) a. All the girls watched movies. b. • Semantically vacuous plural is licensed only in the scope of another plural feature: (13) a. Mary watched movies. b. Every girl watched movies.

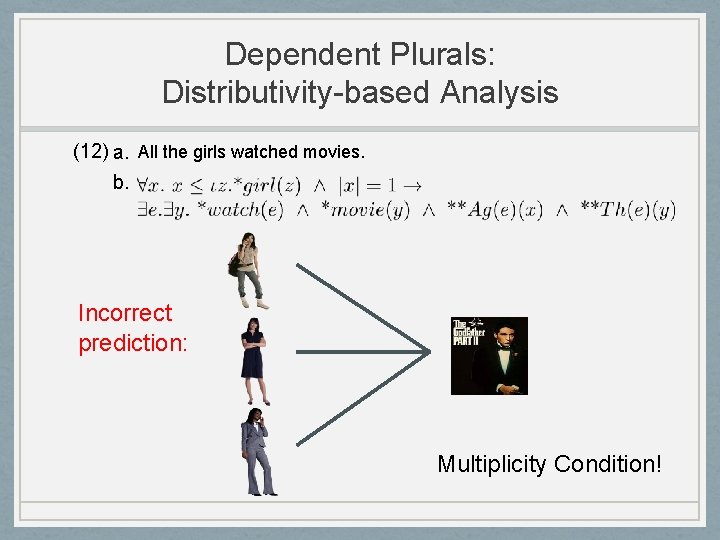

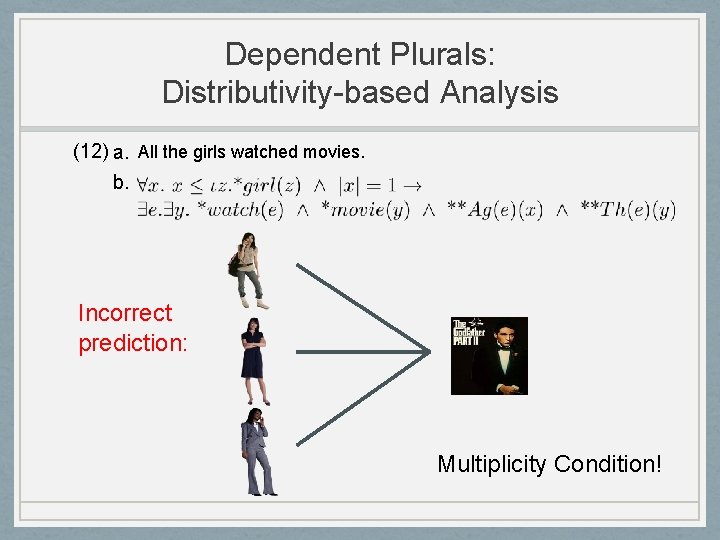

Dependent Plurals: Distributivity-based Analysis (12) a. All the girls watched movies. b. Incorrect prediction: Multiplicity Condition!

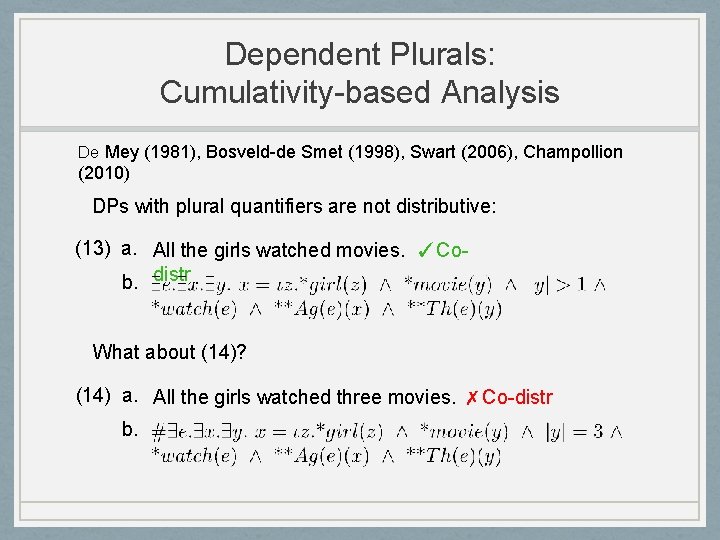

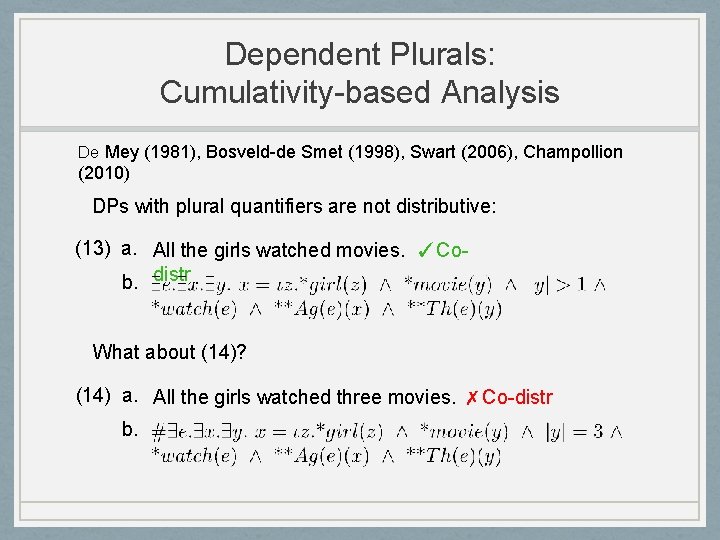

Dependent Plurals: Cumulativity-based Analysis De Mey (1981), Bosveld-de Smet (1998), Swart (2006), Champollion (2010) DPs with plural quantifiers are not distributive: (13) a. All the girls watched movies. ✓Cob. distr What about (14)? (14) a. All the girls watched three movies. ✗Co-distr b.

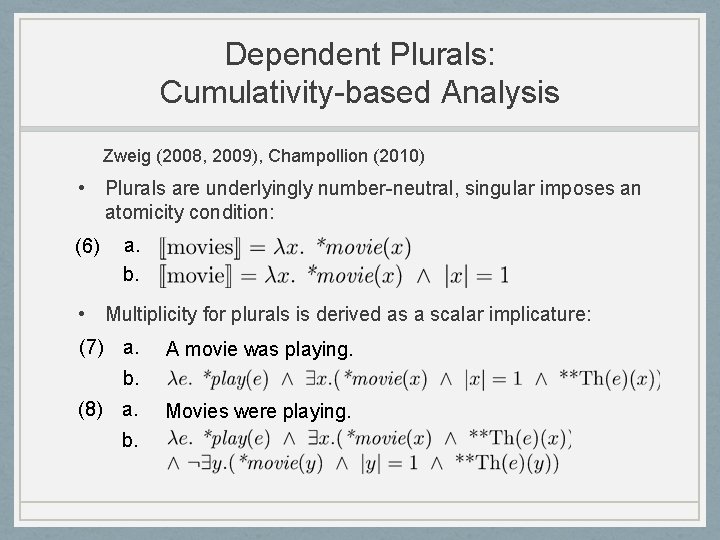

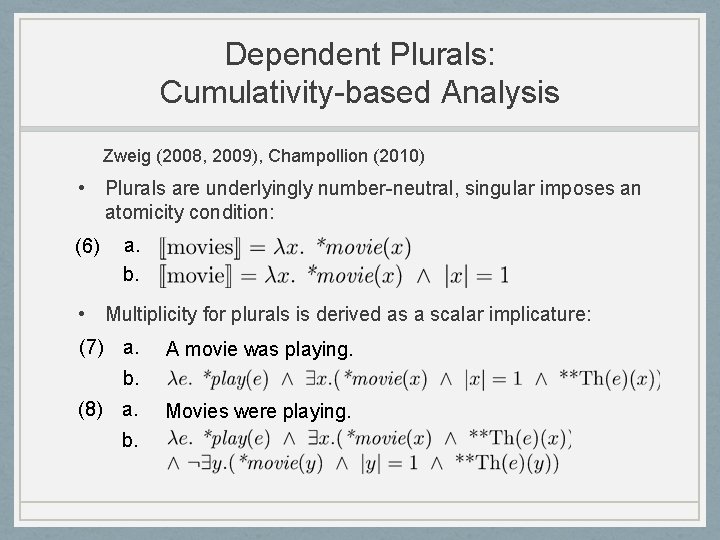

Dependent Plurals: Cumulativity-based Analysis Zweig (2008, 2009), Champollion (2010) • Plurals are underlyingly number-neutral, singular imposes an atomicity condition: (6) a. b. • Multiplicity for plurals is derived as a scalar implicature: (7) a. A movie was playing. b. (8) a. b. Movies were playing.

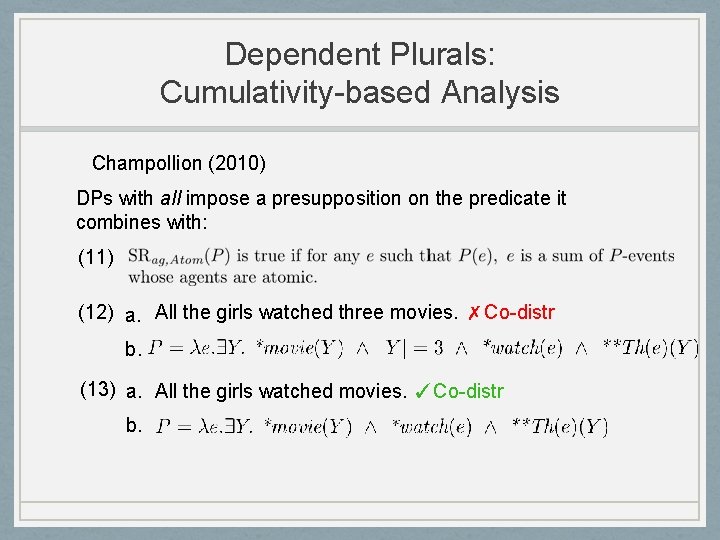

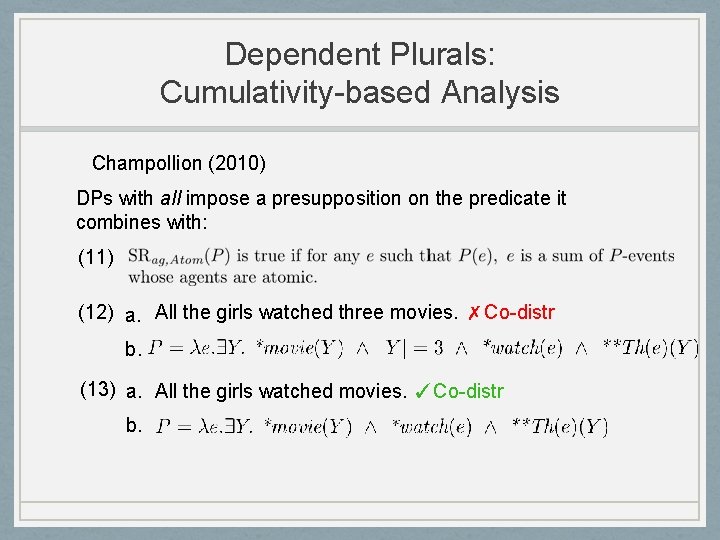

Dependent Plurals: Cumulativity-based Analysis Champollion (2010) DPs with all impose a presupposition on the predicate it combines with: (11) (12) a. All the girls watched three movies. ✗Co-distr b. (13) a. All the girls watched movies. ✓Co-distr b.

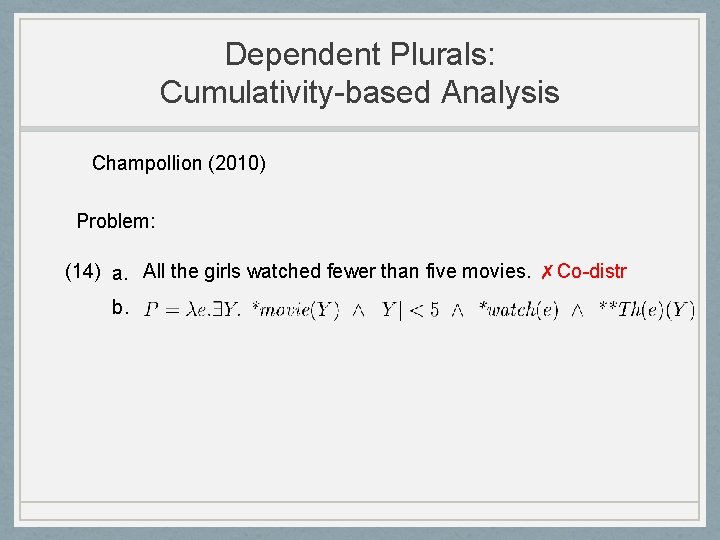

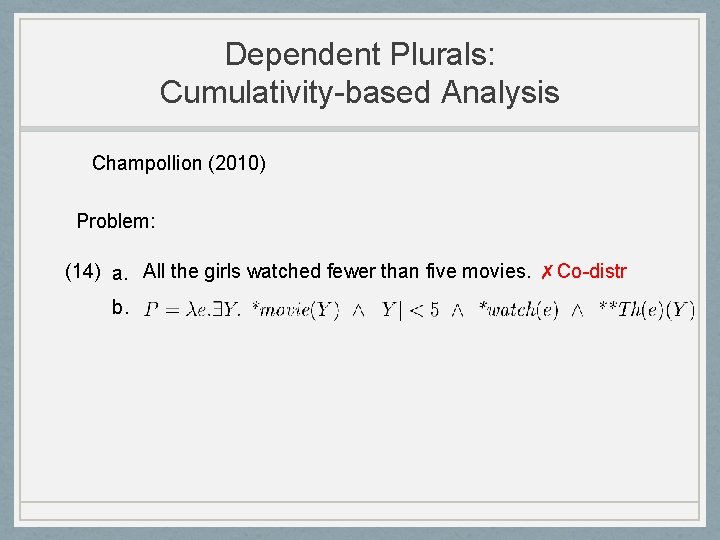

Dependent Plurals: Cumulativity-based Analysis Champollion (2010) Problem: (14) a. All the girls watched fewer than five movies. ✗Co-distr b.

The Data: Overview Non-Distr All/most Each/Every DPs with Numerals + * * Bare plurals + + *

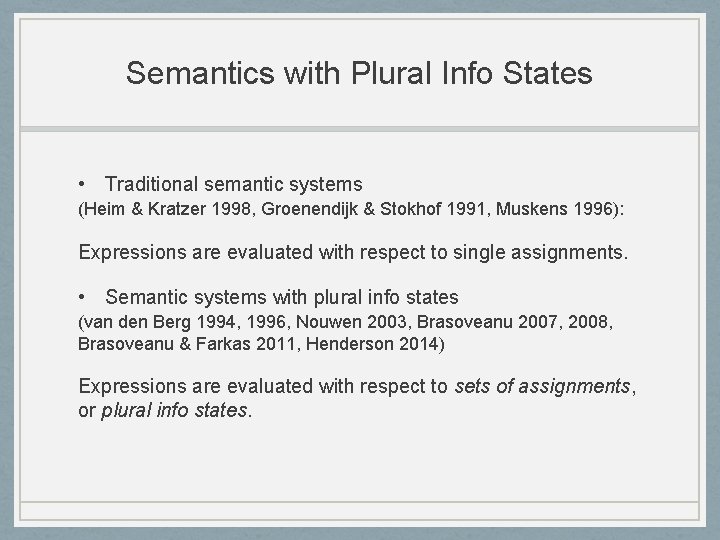

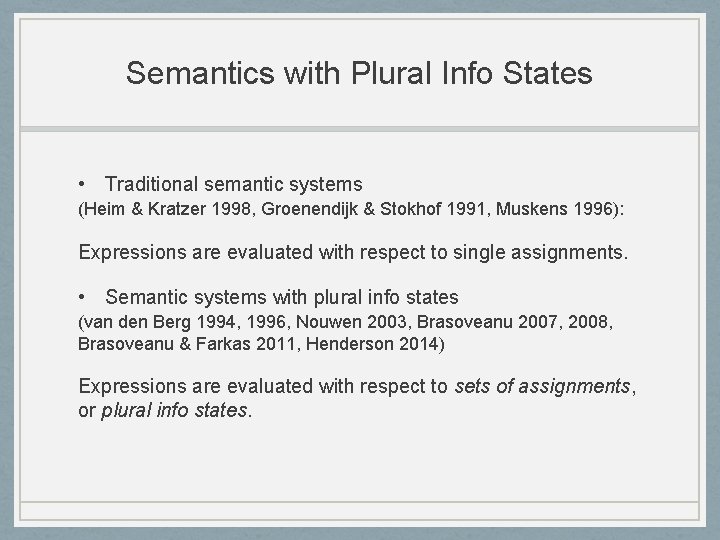

Semantics with Plural Info States • Traditional semantic systems (Heim & Kratzer 1998, Groenendijk & Stokhof 1991, Muskens 1996): Expressions are evaluated with respect to single assignments. • Semantic systems with plural info states (van den Berg 1994, 1996, Nouwen 2003, Brasoveanu 2007, 2008, Brasoveanu & Farkas 2011, Henderson 2014) Expressions are evaluated with respect to sets of assignments, or plural info states.

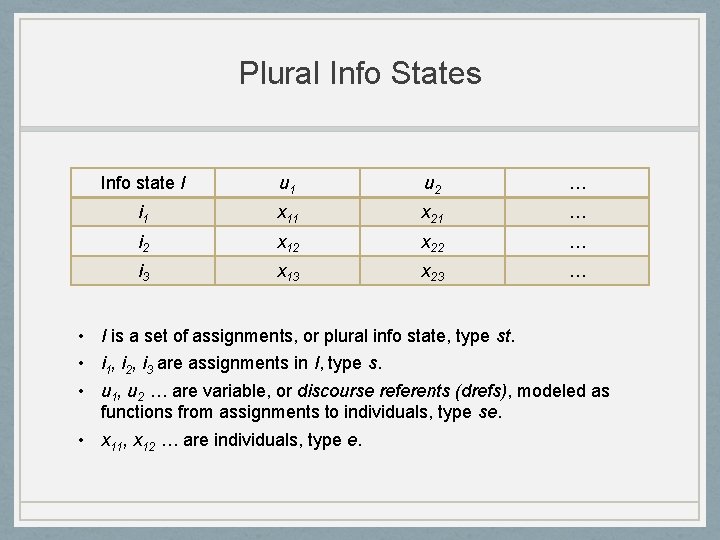

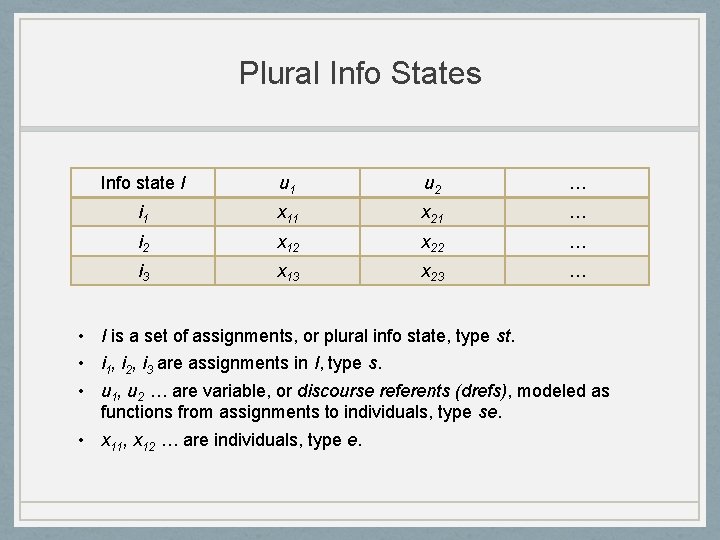

Plural Info States Info state I u 1 u 2 … i 1 x 11 x 21 … i 2 x 12 x 22 … i 3 x 13 x 23 … • I is a set of assignments, or plural info state, type st. • i 1, i 2, i 3 are assignments in I, type s. • u 1, u 2 … are variable, or discourse referents (drefs), modeled as functions from assignments to individuals, type se. • x 11, x 12 … are individuals, type e.

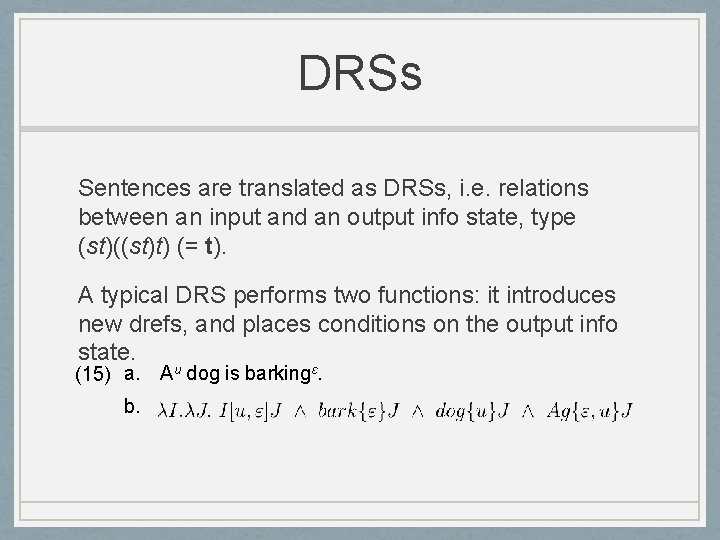

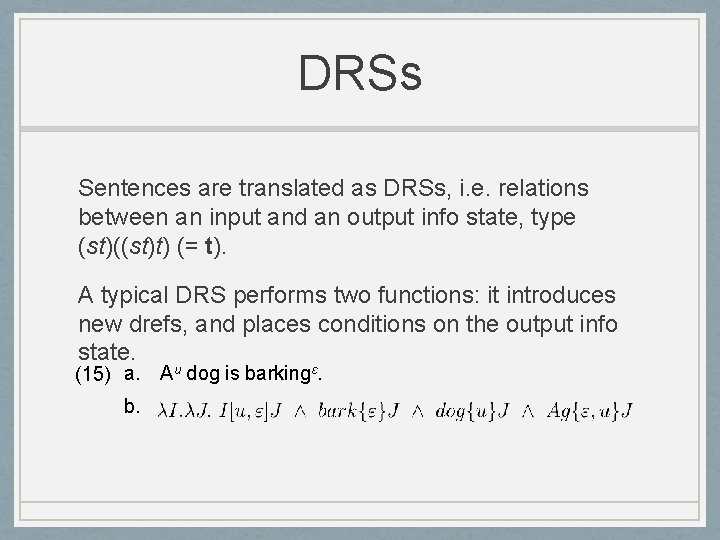

DRSs Sentences are translated as DRSs, i. e. relations between an input and an output info state, type (st)((st)t) (= t). A typical DRS performs two functions: it introduces new drefs, and places conditions on the output info state. (15) a. Au dog is barkingε. b.

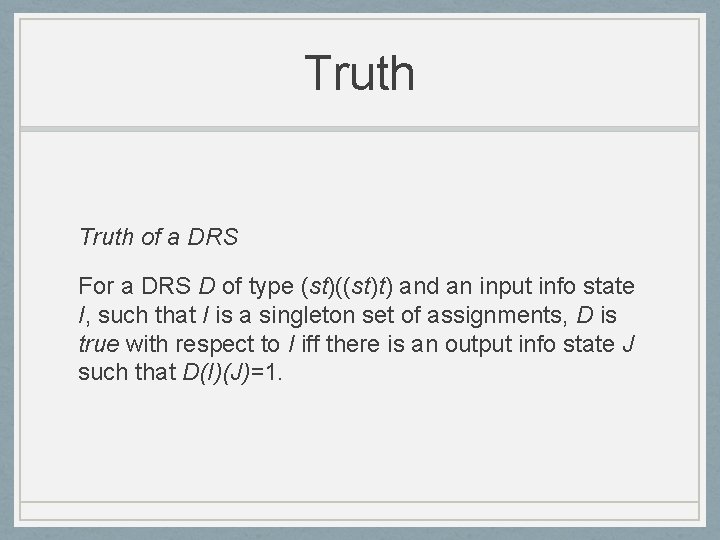

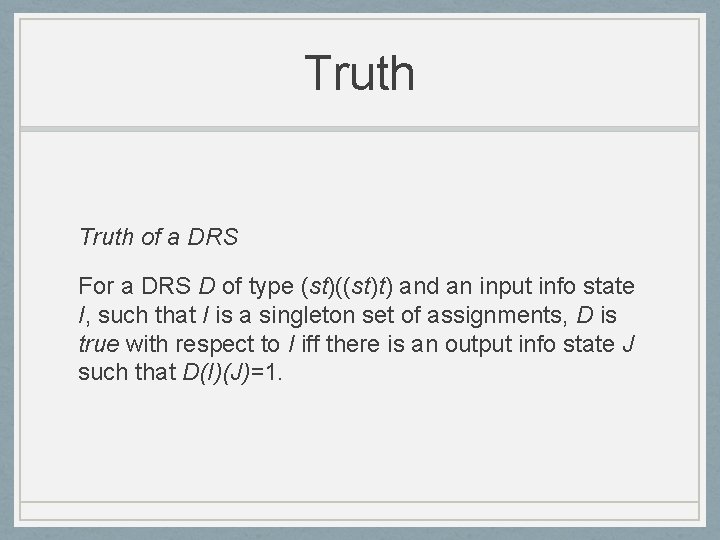

Truth of a DRS For a DRS D of type (st)((st)t) and an input info state I, such that I is a singleton set of assignments, D is true with respect to I iff there is an output info state J such that D(I)(J)=1.

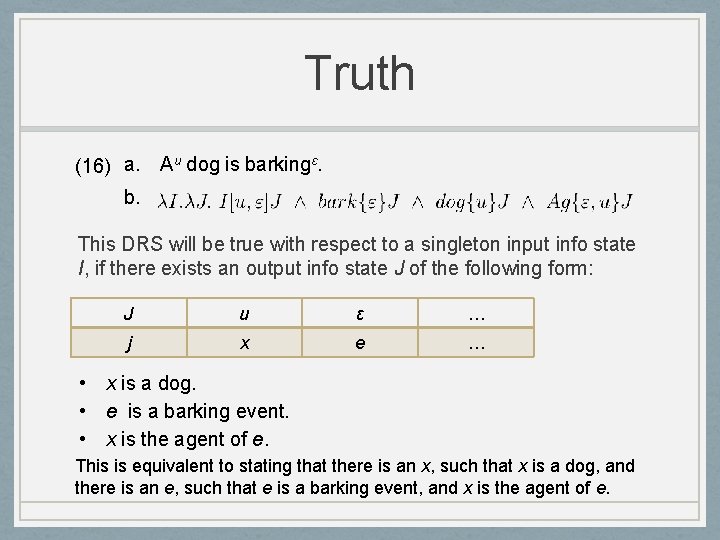

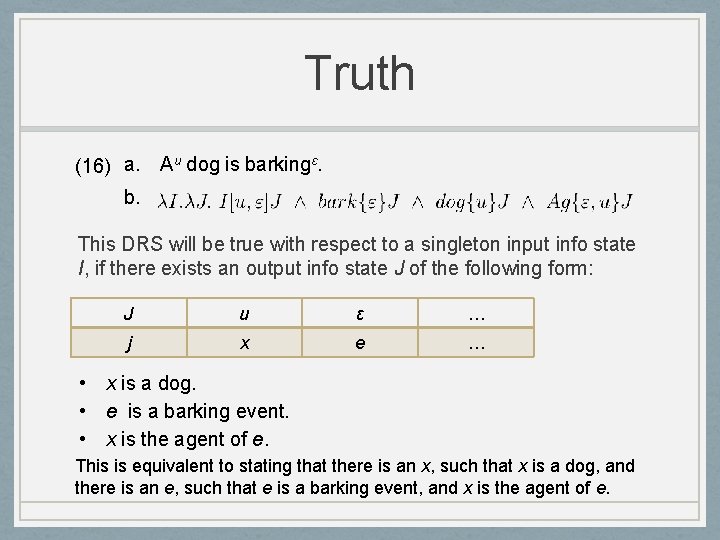

Truth (16) a. Au dog is barkingε. b. This DRS will be true with respect to a singleton input info state I, if there exists an output info state J of the following form: J u ε … j x e … • x is a dog. • e is a barking event. • x is the agent of e. This is equivalent to stating that there is an x, such that x is a dog, and there is an e, such that e is a barking event, and x is the agent of e.

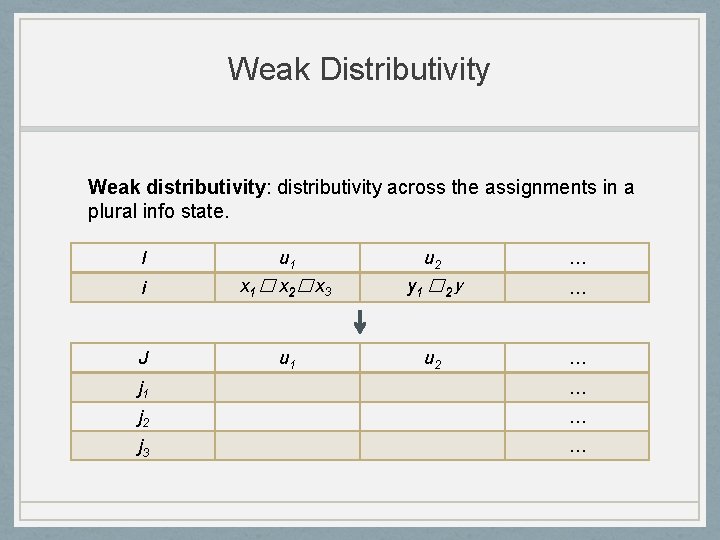

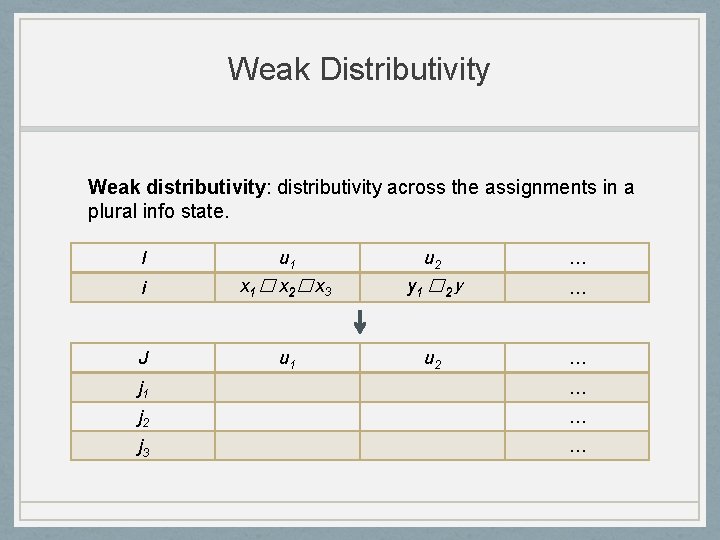

Weak Distributivity Weak distributivity: distributivity across the assignments in a plural info state. I u 1 u 2 … i x 1 � x 2 � x 3 y 1 � 2 y … J u 1 u 2 … j 1 … j 2 … j 3 …

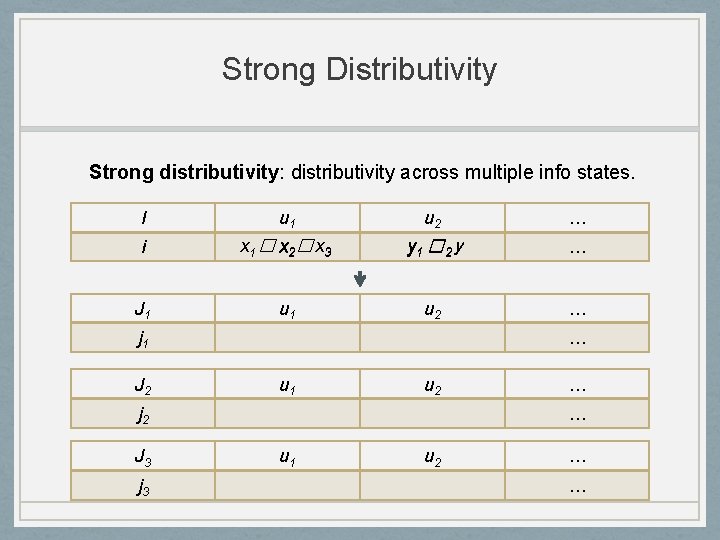

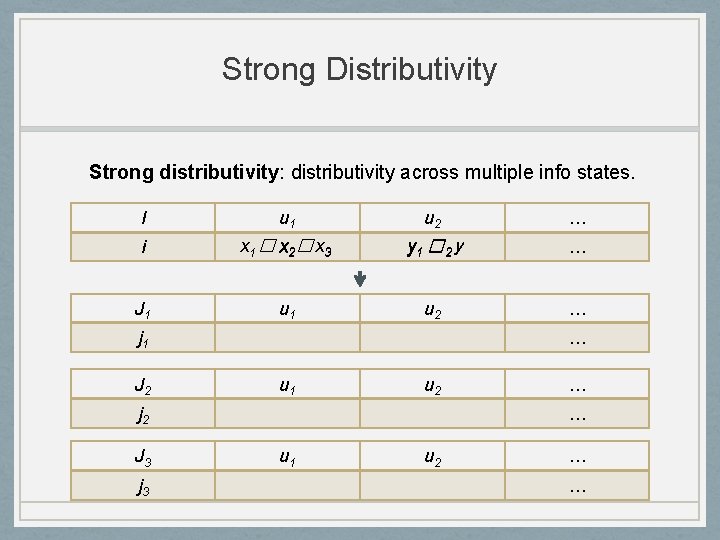

Strong Distributivity Strong distributivity: distributivity across multiple info states. I u 1 u 2 … i x 1 � x 2 � x 3 y 1 � 2 y … J 1 u 2 … j 1 J 2 … u 1 u 2 j 2 J 3 j 3 … … u 1 u 2 … …

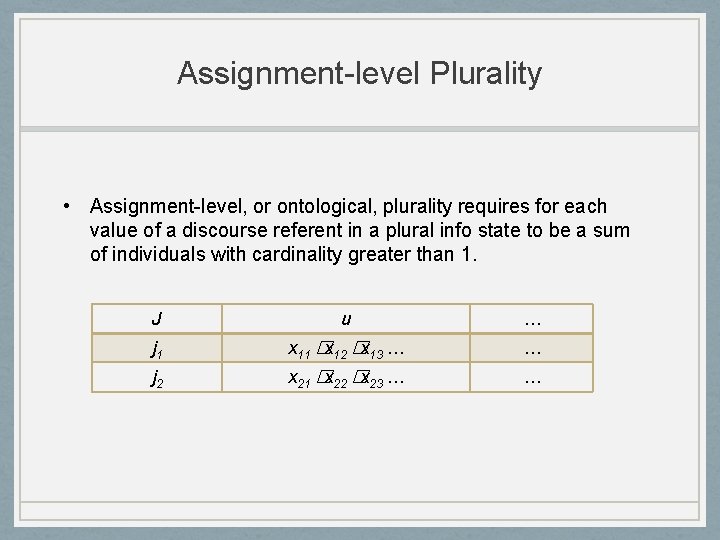

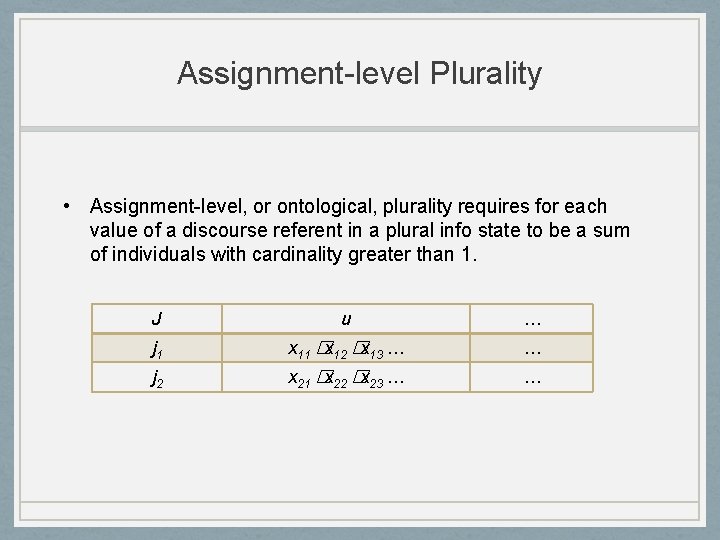

Assignment-level Plurality • Assignment-level, or ontological, plurality requires for each value of a discourse referent in a plural info state to be a sum of individuals with cardinality greater than 1. J u … j 1 x 11 �x 12 �x 13 … … j 2 x 21 �x 22 �x 23 … …

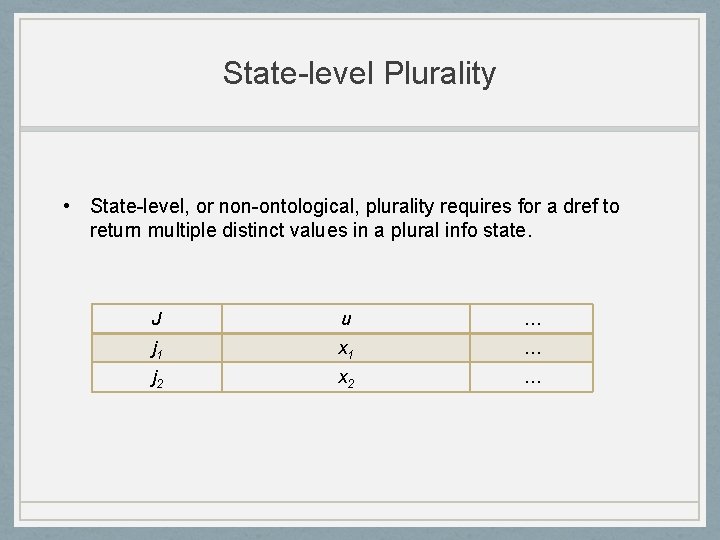

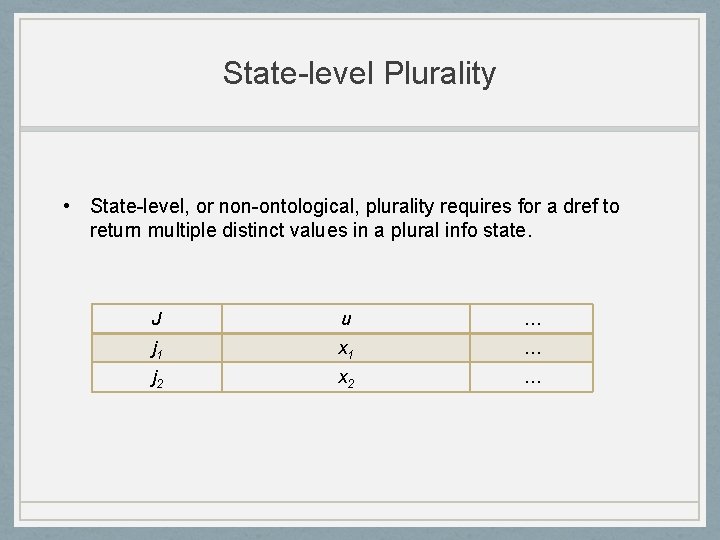

State-level Plurality • State-level, or non-ontological, plurality requires for a dref to return multiple distinct values in a plural info state. J u … j 1 x 1 … j 2 x 2 …

Proposal: Determiners • Non-quantificational determiners (e. g. the definite and indefinite articles) do not induce distributivity. • All/most encode weak distributivity. • Each/every encode strong distributivity.

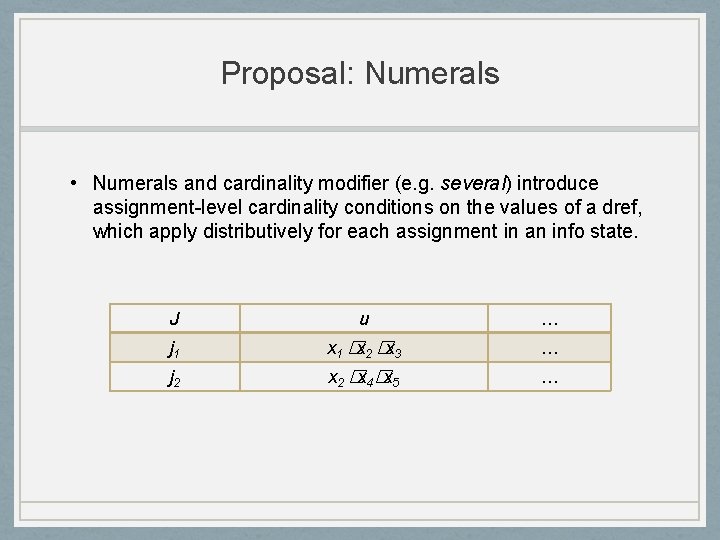

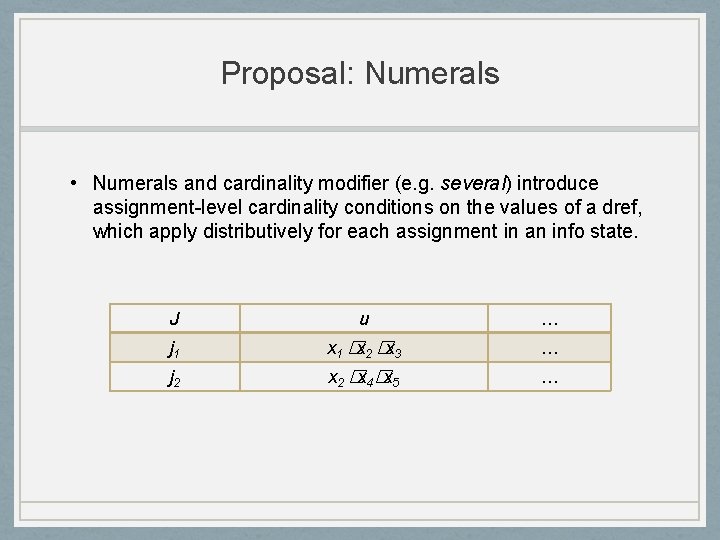

Proposal: Numerals • Numerals and cardinality modifier (e. g. several) introduce assignment-level cardinality conditions on the values of a dref, which apply distributively for each assignment in an info state. J u … j 1 x 1 �x 2 �x 3 … j 2 x 2 �x 4�x 5 …

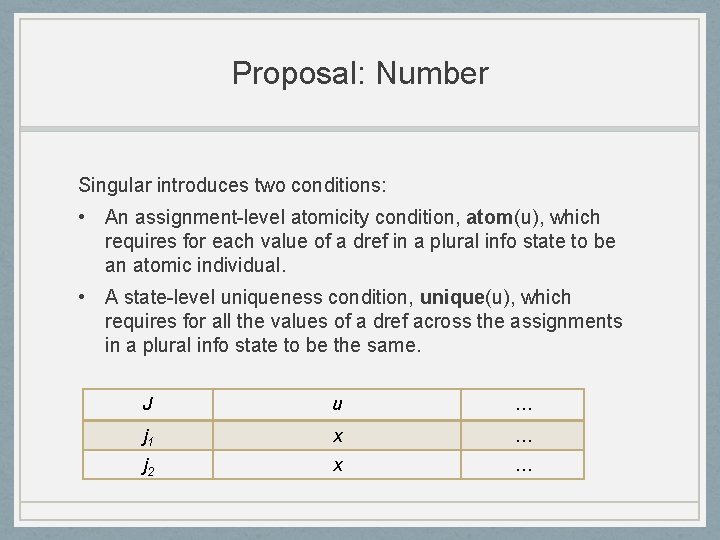

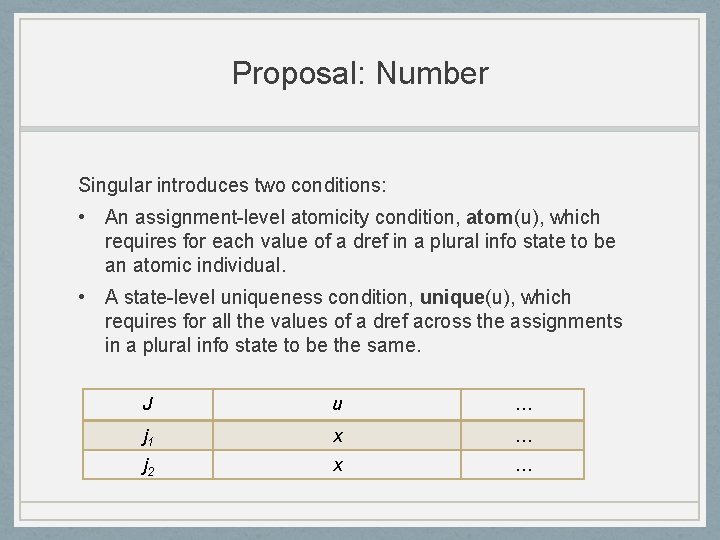

Proposal: Number Singular introduces two conditions: • An assignment-level atomicity condition, atom(u), which requires for each value of a dref in a plural info state to be an atomic individual. • A state-level uniqueness condition, unique(u), which requires for all the values of a dref across the assignments in a plural info state to be the same. J u … j 1 x … j 2 x …

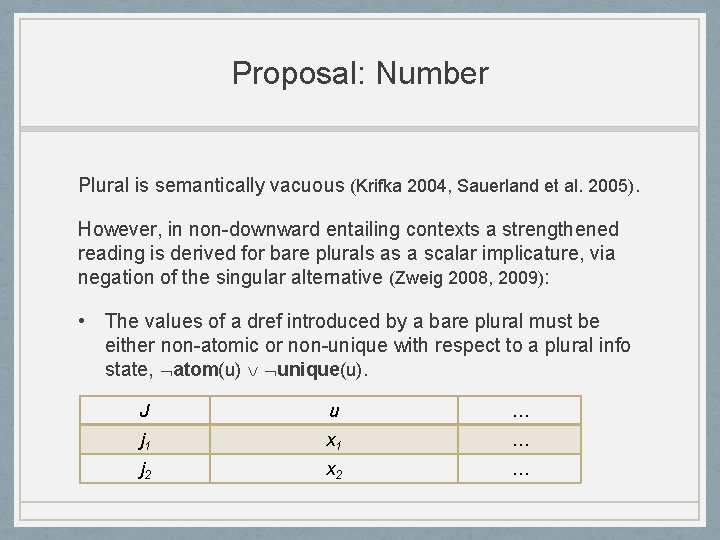

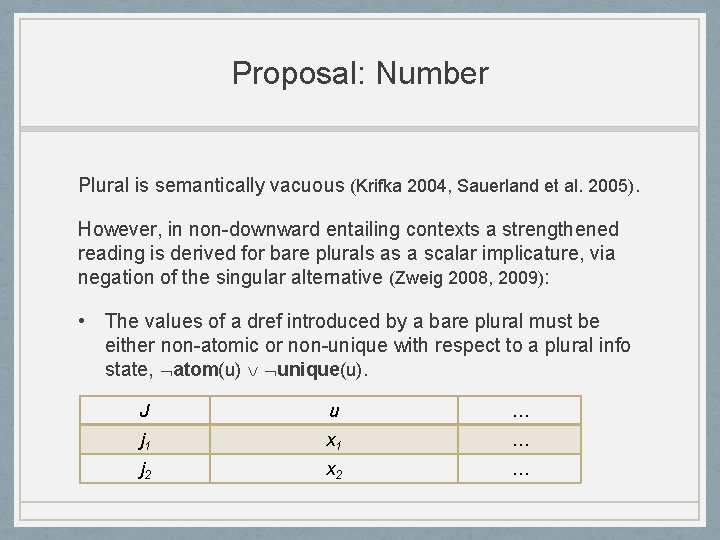

Proposal: Number Plural is semantically vacuous (Krifka 2004, Sauerland et al. 2005). However, in non-downward entailing contexts a strengthened reading is derived for bare plurals as a scalar implicature, via negation of the singular alternative (Zweig 2008, 2009): • The values of a dref introduced by a bare plural must be either non-atomic or non-unique with respect to a plural info state, atom(u) unique(u). J u … j 1 x 1 … j 2 x 2 …

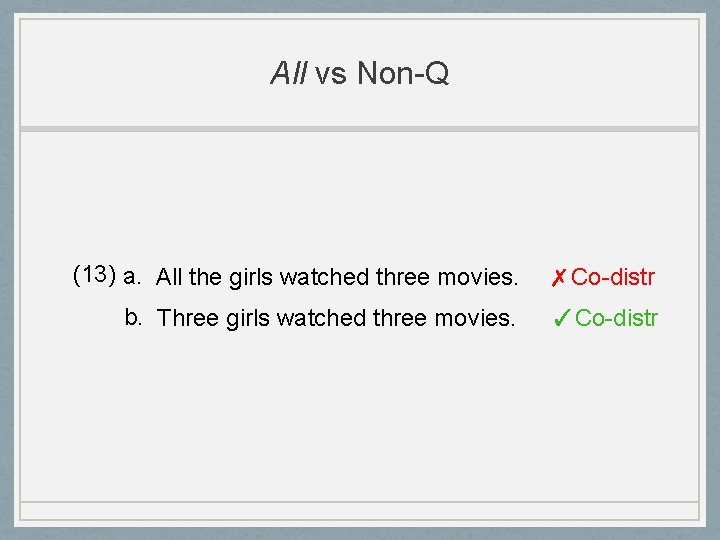

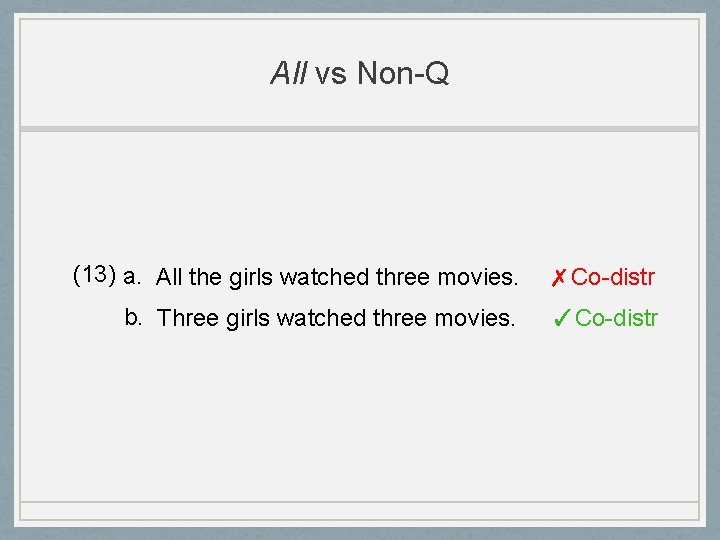

All vs Non-Q (13) a. All the girls watched three movies. ✗Co-distr b. Three girls watched three movies. ✓Co-distr

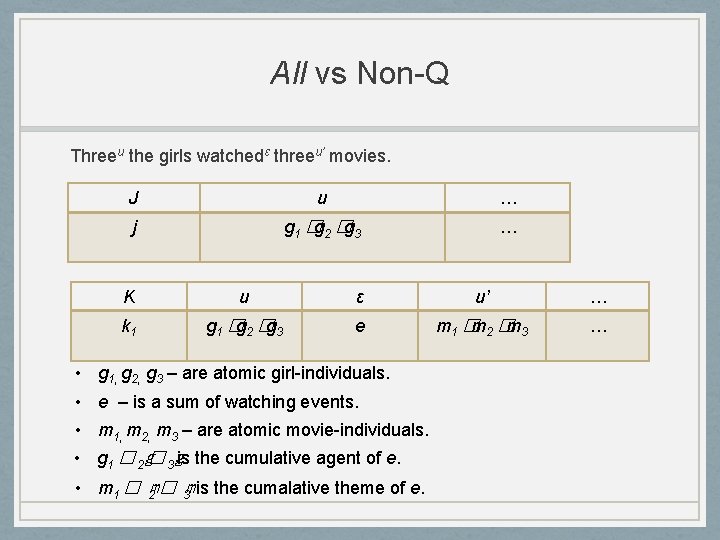

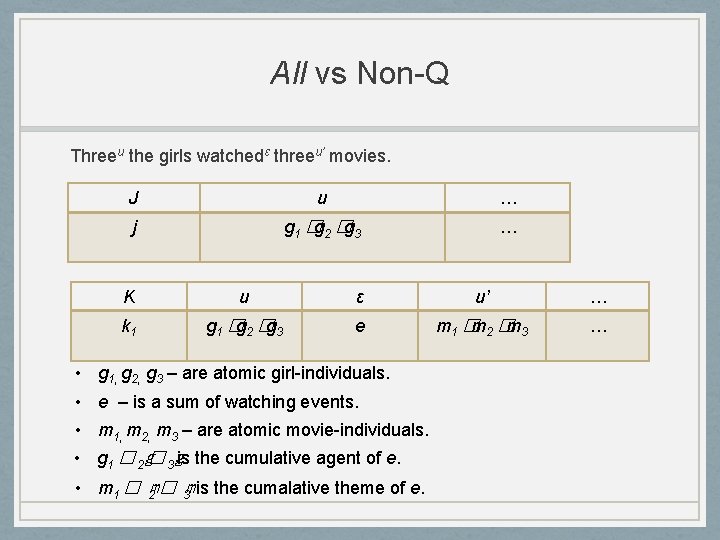

All vs Non-Q Threeu the girls watchedε threeu’ movies. J u … j g 1 �g 2 �g 3 … K u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 �g 2 �g 3 e m 1 �m 2 �m 3 … • g 1, g 2, g 3 – are atomic girl-individuals. • e – is a sum of watching events. • m 1, m 2, m 3 – are atomic movie-individuals. • g 1 � 2 g� 3 gis the cumulative agent of e. • m 1 � 2 m� 3 m is the cumalative theme of e.

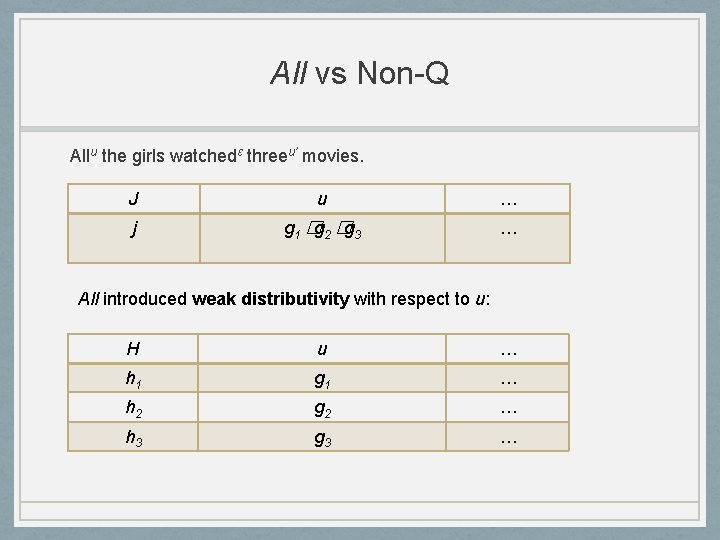

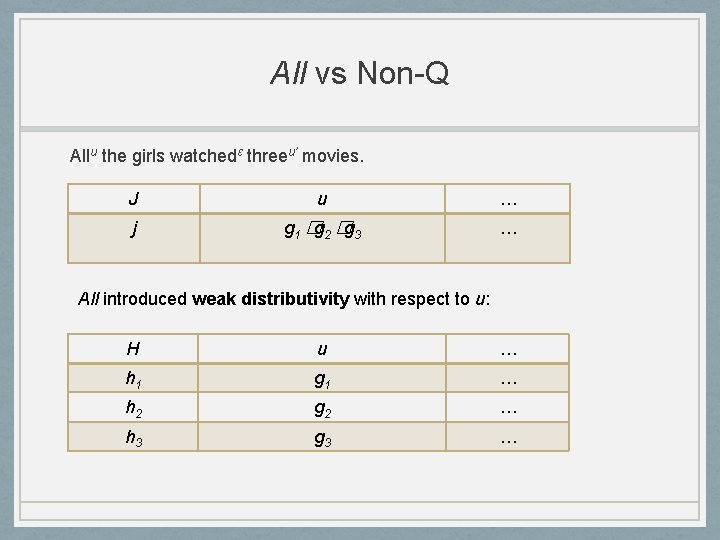

All vs Non-Q Allu the girls watchedε threeu’ movies. J u … j g 1 �g 2 �g 3 … All introduced weak distributivity with respect to u: H u … h 1 g 1 … h 2 g 2 … h 3 g 3 …

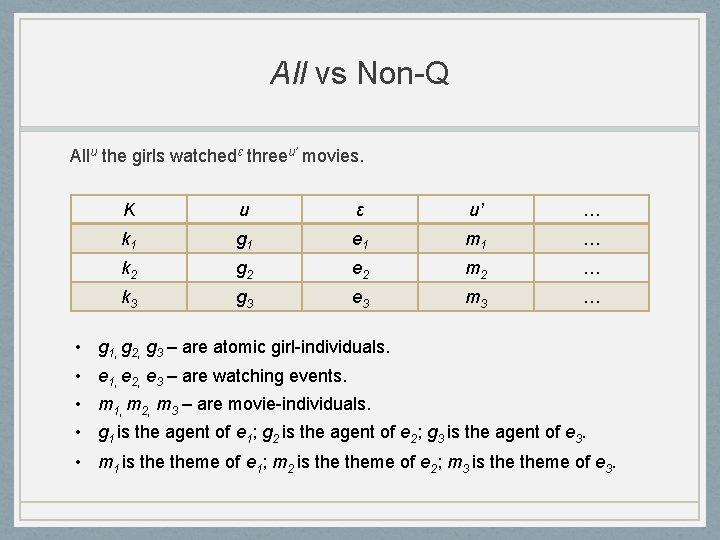

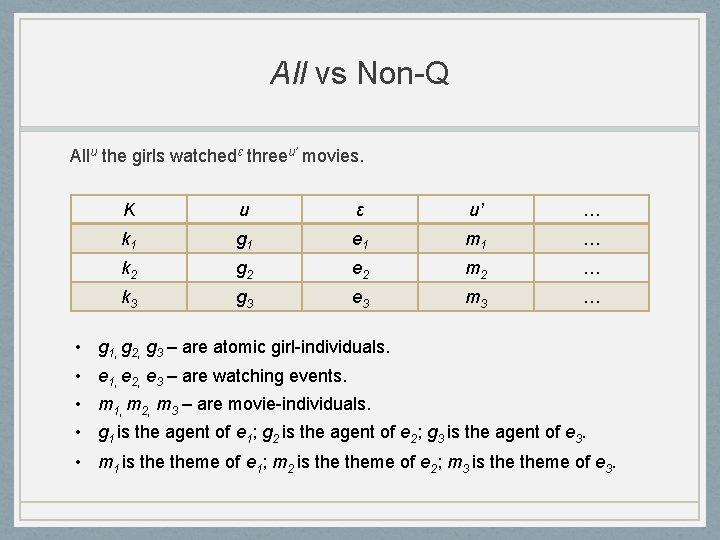

All vs Non-Q Allu the girls watchedε threeu’ movies. K u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 e 1 m 1 … k 2 g 2 e 2 m 2 … k 3 g 3 e 3 m 3 … • g 1, g 2, g 3 – are atomic girl-individuals. • e 1, e 2, e 3 – are watching events. • m 1, m 2, m 3 – are movie-individuals. • g 1 is the agent of e 1; g 2 is the agent of e 2; g 3 is the agent of e 3. • m 1 is theme of e 1; m 2 is theme of e 2; m 3 is theme of e 3.

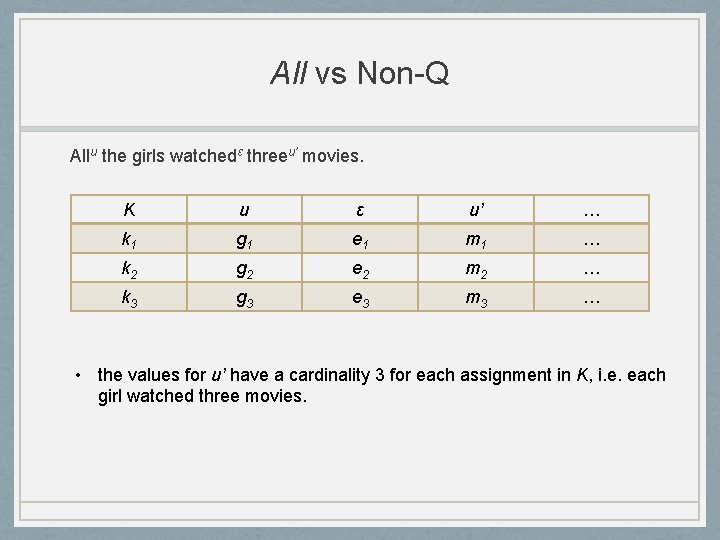

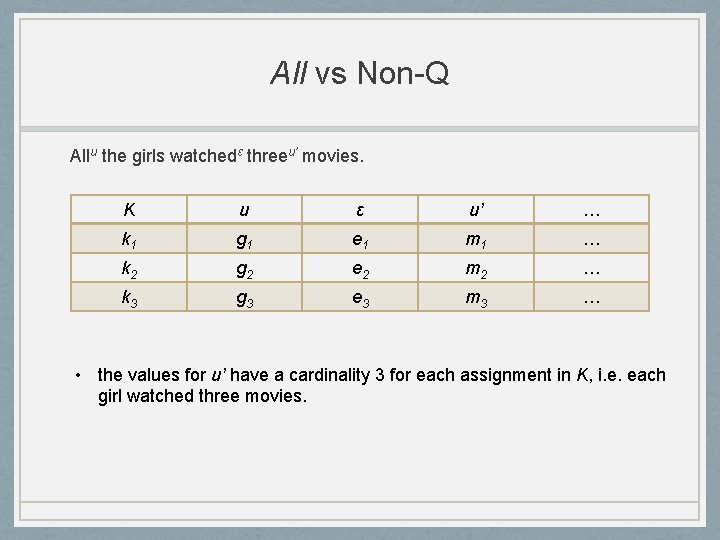

All vs Non-Q Allu the girls watchedε threeu’ movies. K u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 e 1 m 1 … k 2 g 2 e 2 m 2 … k 3 g 3 e 3 m 3 … • the values for u’ have a cardinality 3 for each assignment in K, i. e. each girl watched three movies.

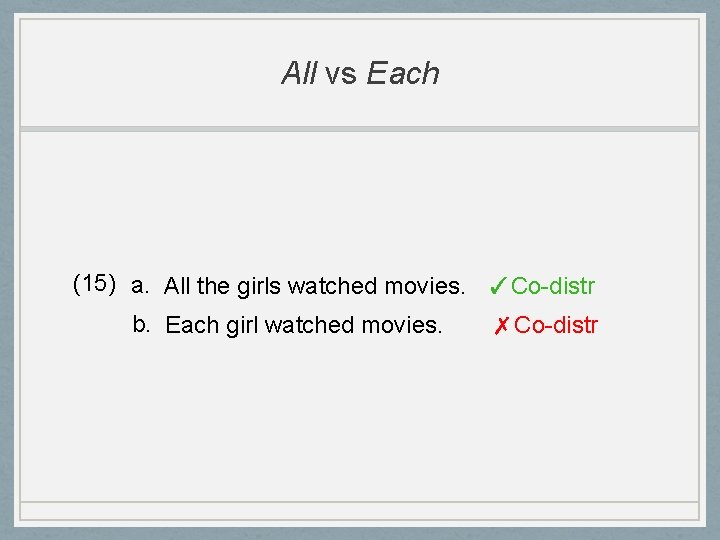

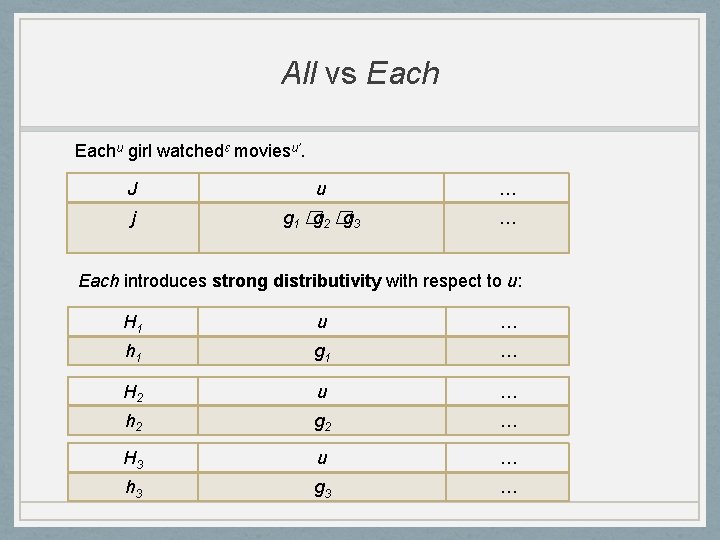

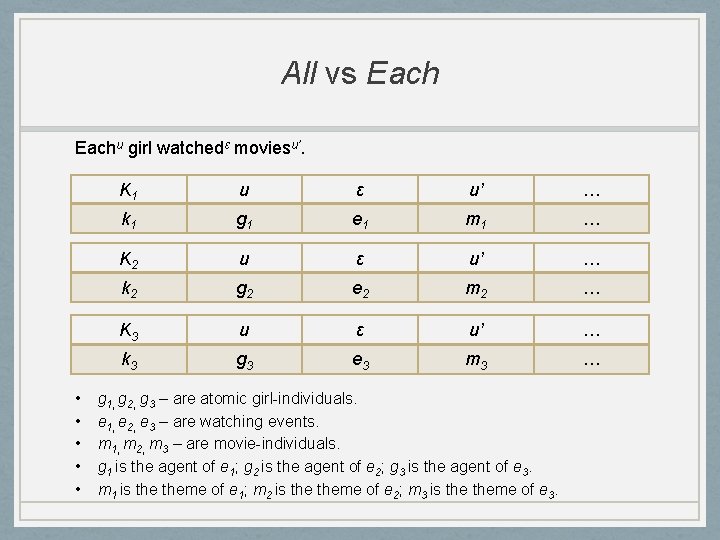

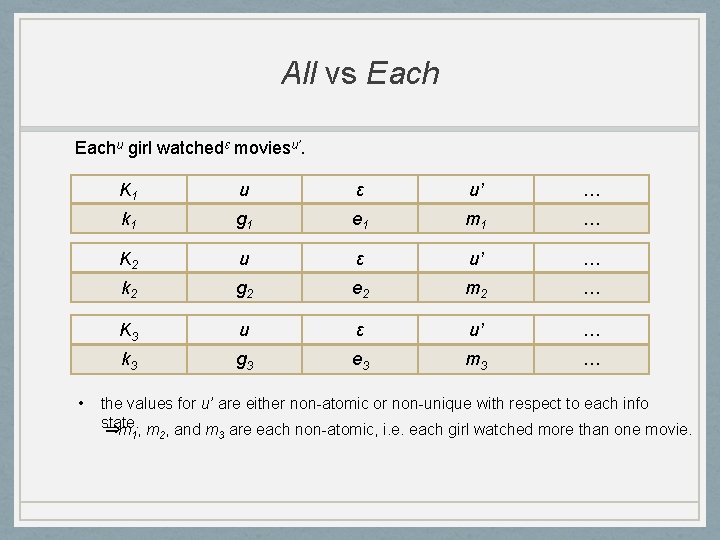

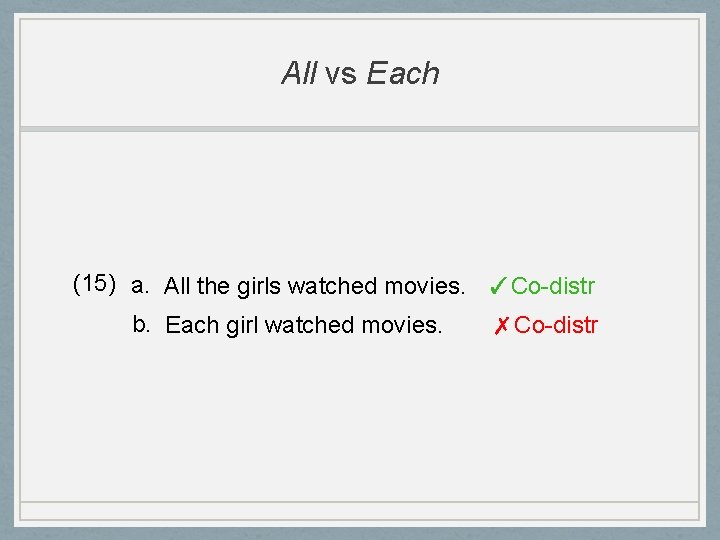

All vs Each (15) a. All the girls watched movies. ✓Co-distr b. Each girl watched movies. ✗Co-distr

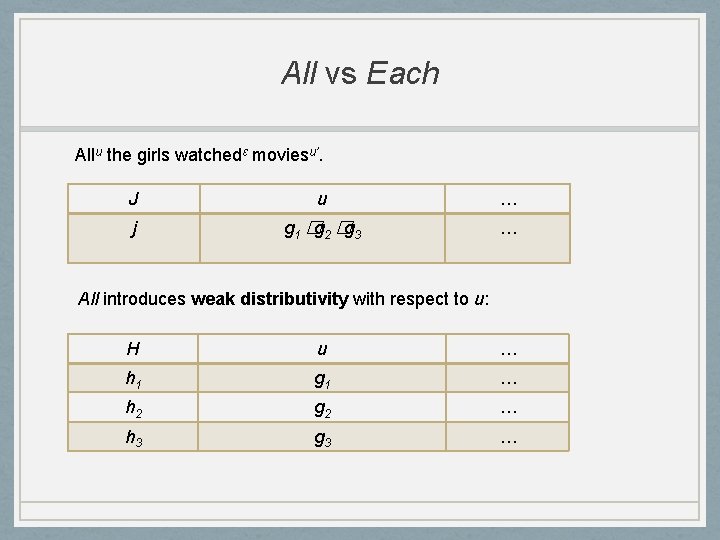

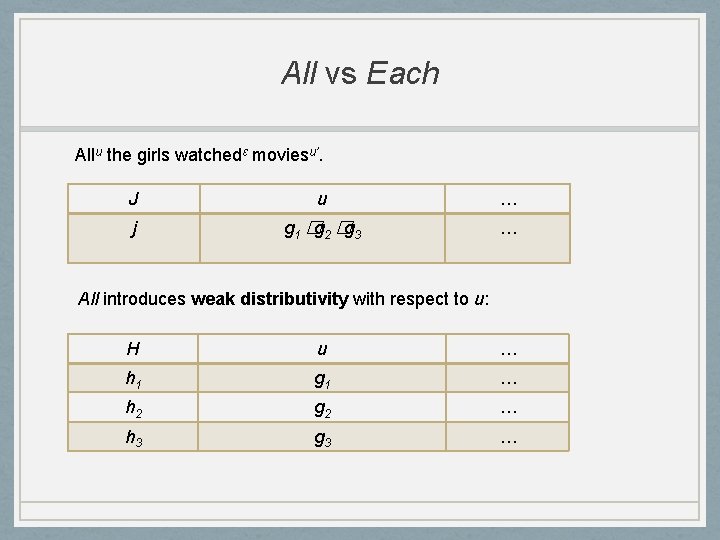

All vs Each Allu the girls watchedε moviesu’. J u … j g 1 �g 2 �g 3 … All introduces weak distributivity with respect to u: H u … h 1 g 1 … h 2 g 2 … h 3 g 3 …

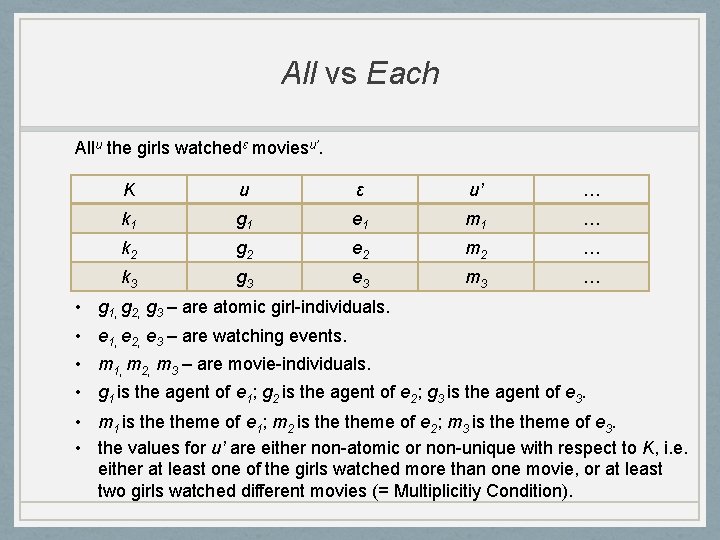

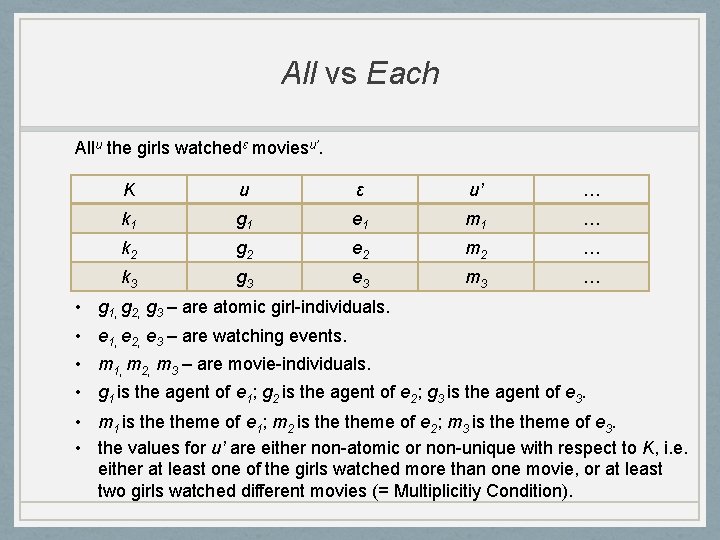

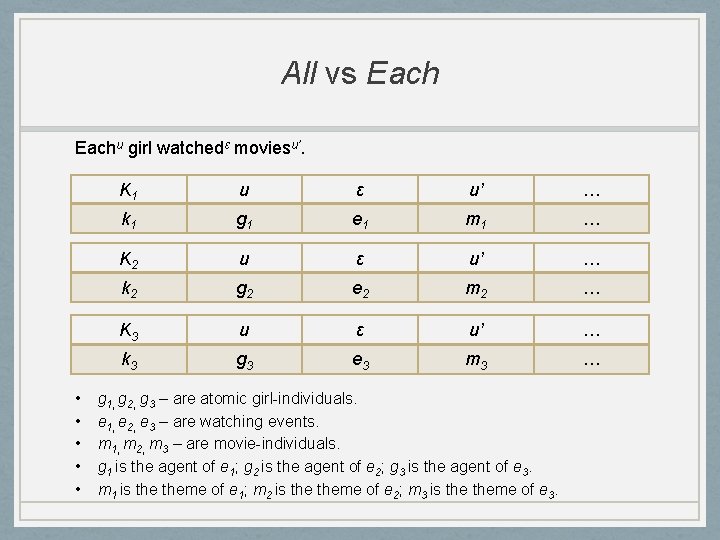

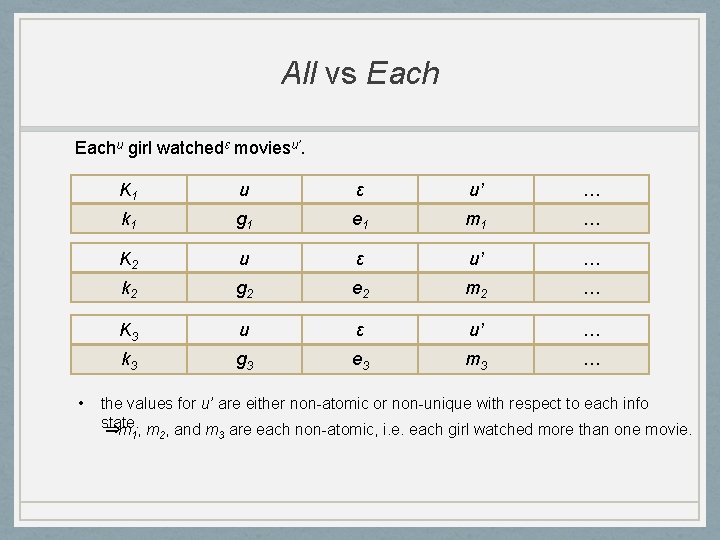

All vs Each Allu the girls watchedε moviesu’. K u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 e 1 m 1 … k 2 g 2 e 2 m 2 … k 3 g 3 e 3 m 3 … • g 1, g 2, g 3 – are atomic girl-individuals. • e 1, e 2, e 3 – are watching events. • m 1, m 2, m 3 – are movie-individuals. • g 1 is the agent of e 1; g 2 is the agent of e 2; g 3 is the agent of e 3. • m 1 is theme of e 1; m 2 is theme of e 2; m 3 is theme of e 3. • the values for u’ are either non-atomic or non-unique with respect to K, i. e. either at least one of the girls watched more than one movie, or at least two girls watched different movies (= Multiplicitiy Condition).

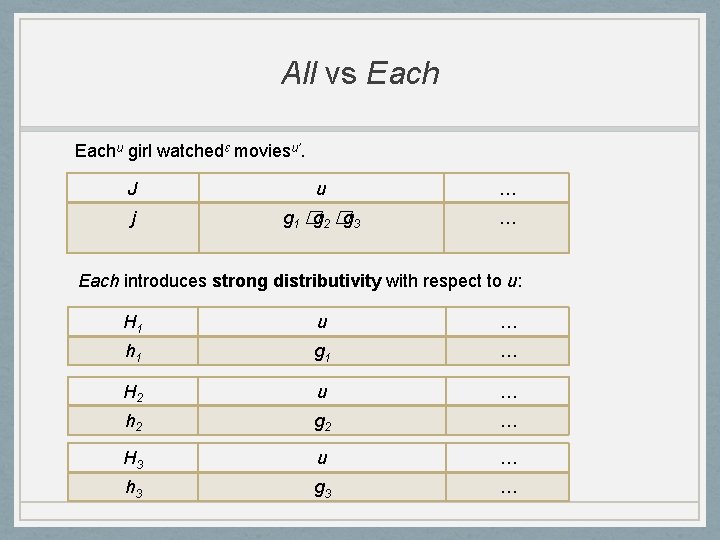

All vs Eachu girl watchedε moviesu’. J u … j g 1 �g 2 �g 3 … Each introduces strong distributivity with respect to u: H 1 u … h 1 g 1 … H 2 u … h 2 g 2 … H 3 u … h 3 g 3 …

All vs Eachu girl watchedε moviesu’. • • • K 1 u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 e 1 m 1 … K 2 u ε u’ … k 2 g 2 e 2 m 2 … K 3 u ε u’ … k 3 g 3 e 3 m 3 … g 1, g 2, g 3 – are atomic girl-individuals. e 1, e 2, e 3 – are watching events. m 1, m 2, m 3 – are movie-individuals. g 1 is the agent of e 1; g 2 is the agent of e 2; g 3 is the agent of e 3. m 1 is theme of e 1; m 2 is theme of e 2; m 3 is theme of e 3.

All vs Eachu girl watchedε moviesu’. • K 1 u ε u’ … k 1 g 1 e 1 m 1 … K 2 u ε u’ … k 2 g 2 e 2 m 2 … K 3 u ε u’ … k 3 g 3 e 3 m 3 … the values for u’ are either non-atomic or non-unique with respect to each info state. ⇒m , and m are each non-atomic, i. e. each girl watched more than one movie. 1 2 3

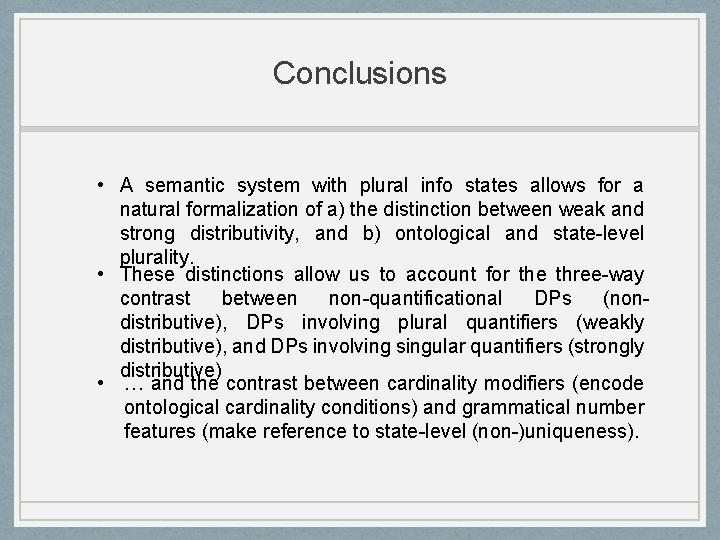

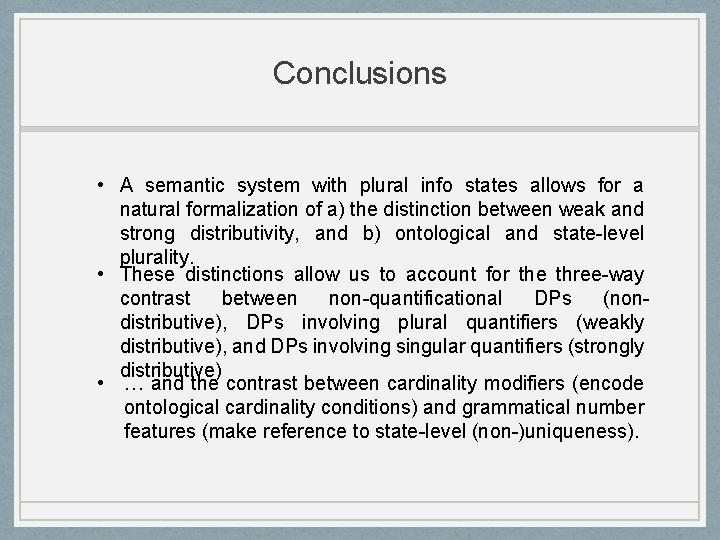

Conclusions • A semantic system with plural info states allows for a natural formalization of a) the distinction between weak and strong distributivity, and b) ontological and state-level plurality. • These distinctions allow us to account for the three-way contrast between non-quantificational DPs (nondistributive), DPs involving plural quantifiers (weakly distributive), and DPs involving singular quantifiers (strongly distributive) • … and the contrast between cardinality modifiers (encode ontological cardinality conditions) and grammatical number features (make reference to state-level (non-)uniqueness).

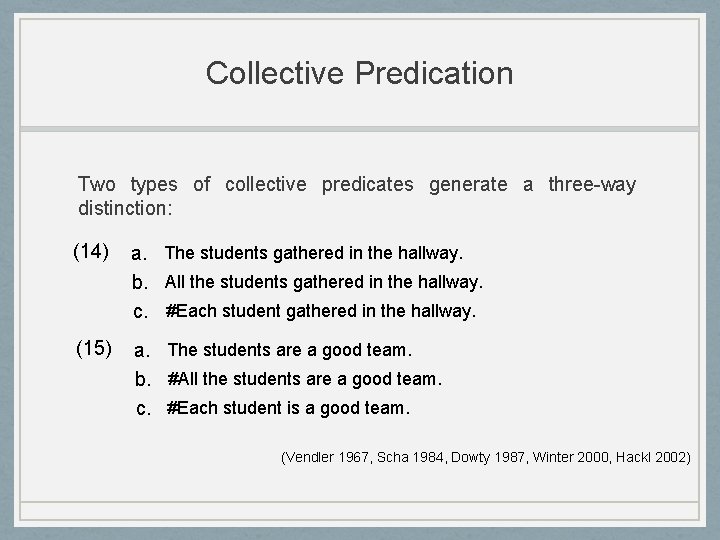

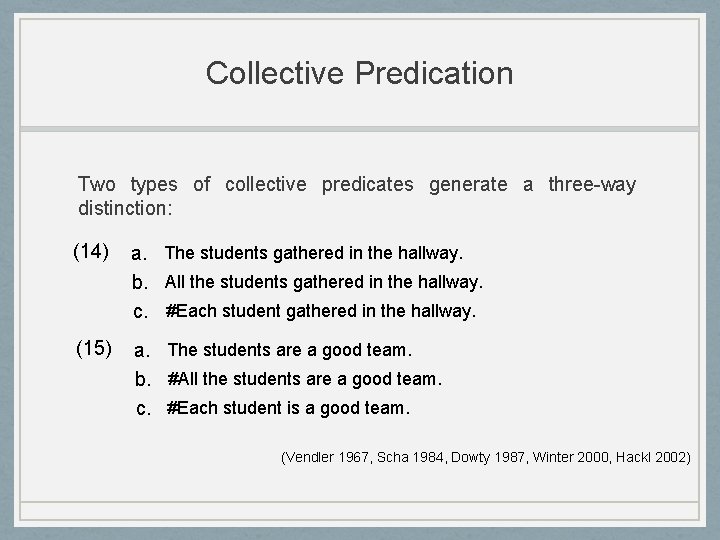

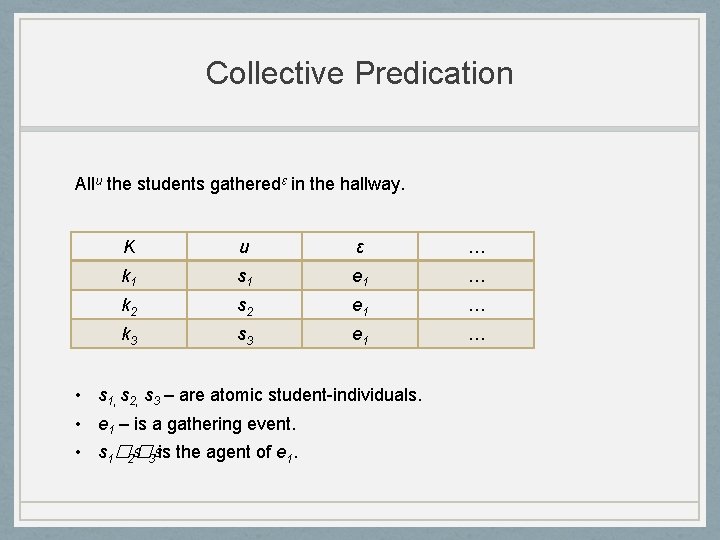

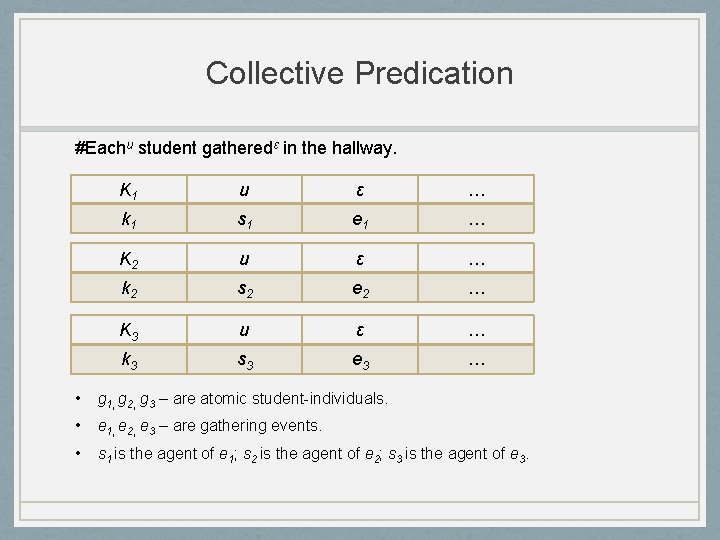

Collective Predication Two types of collective predicates generate a three-way distinction: (14) a. The students gathered in the hallway. b. All the students gathered in the hallway. c. #Each student gathered in the hallway. (15) a. The students are a good team. b. #All the students are a good team. c. #Each student is a good team. (Vendler 1967, Scha 1984, Dowty 1987, Winter 2000, Hackl 2002)

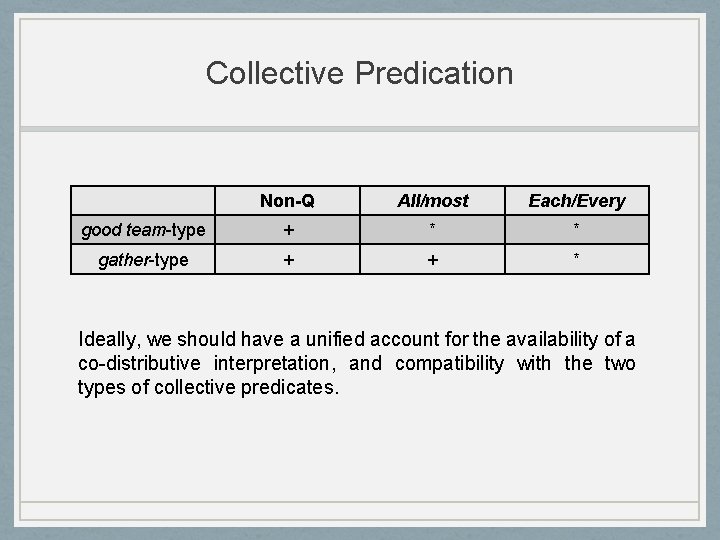

Collective Predication Non-Q All/most Each/Every good team-type + * * gather-type + + * Ideally, we should have a unified account for the availability of a co-distributive interpretation, and compatibility with the two types of collective predicates.

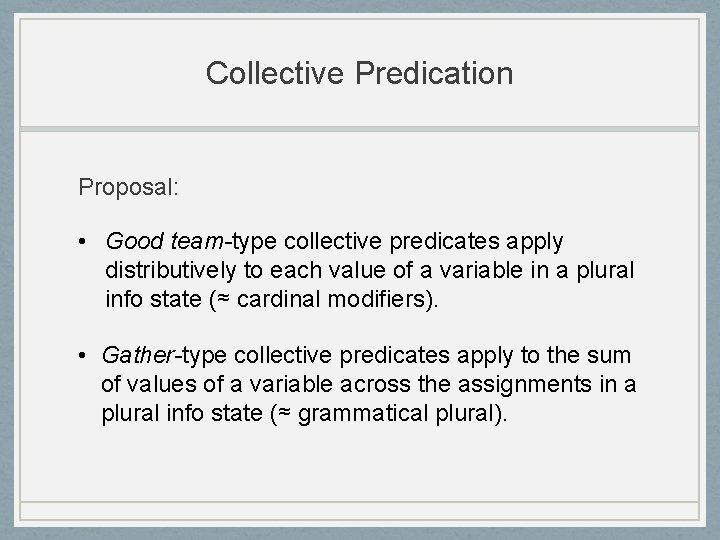

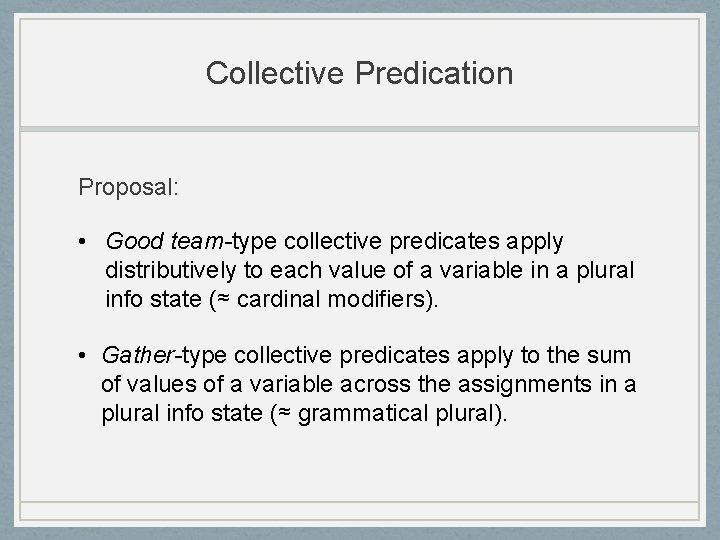

Collective Predication Proposal: • Good team-type collective predicates apply distributively to each value of a variable in a plural info state (≈ cardinal modifiers). • Gather-type collective predicates apply to the sum of values of a variable across the assignments in a plural info state (≈ grammatical plural).

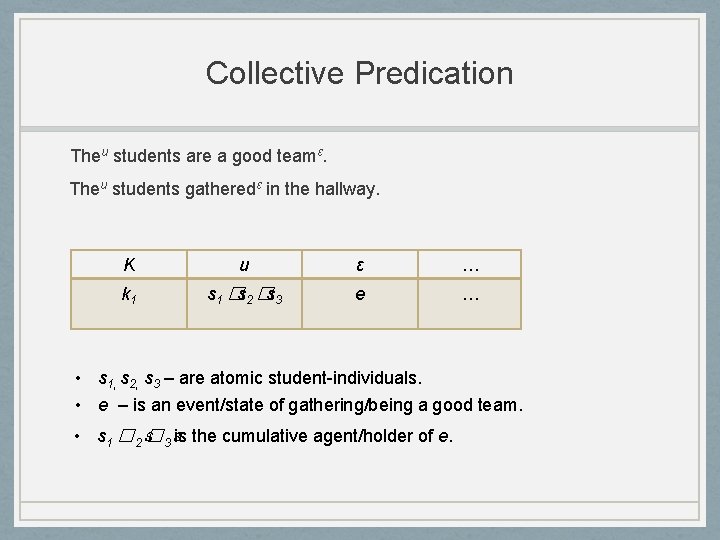

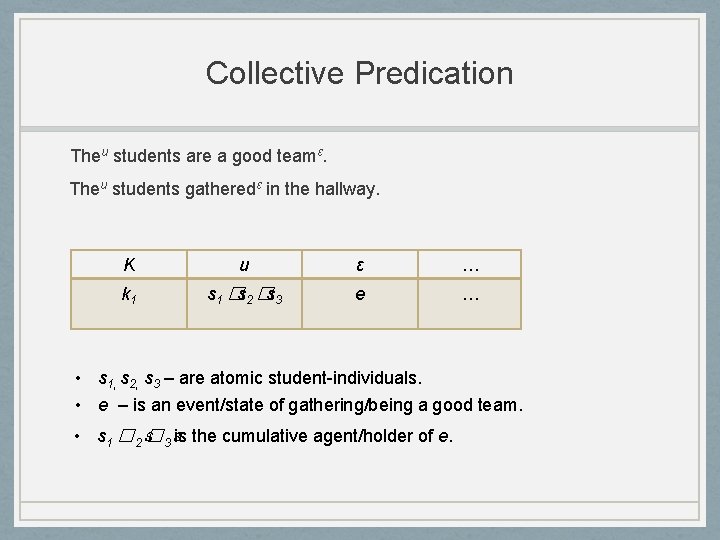

Collective Predication Theu students are a good teamε. Theu students gatheredε in the hallway. K u ε … k 1 s 1 �s 2 �s 3 e … • s 1, s 2, s 3 – are atomic student-individuals. • e – is an event/state of gathering/being a good team. • s 1 � 2 s� 3 sis the cumulative agent/holder of e.

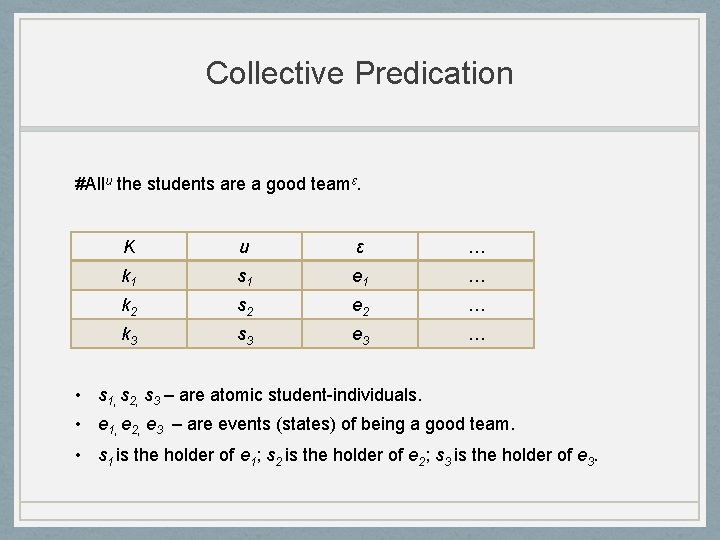

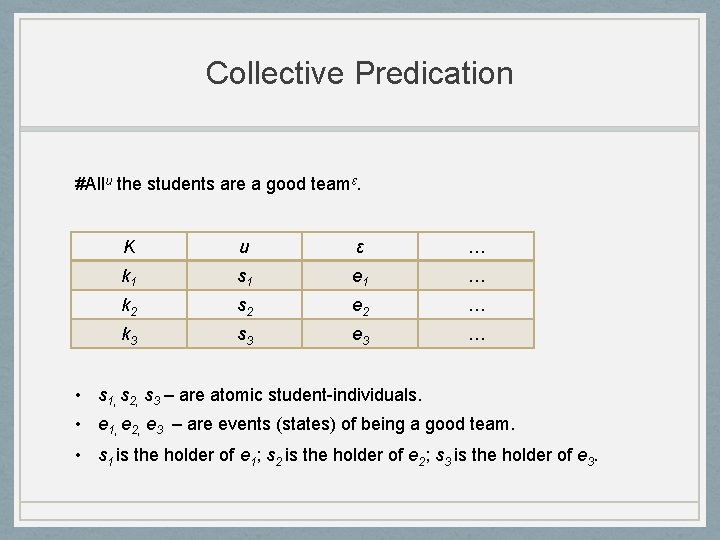

Collective Predication #Allu the students are a good teamε. K u ε … k 1 s 1 e 1 … k 2 s 2 e 2 … k 3 s 3 e 3 … • s 1, s 2, s 3 – are atomic student-individuals. • e 1, e 2, e 3 – are events (states) of being a good team. • s 1 is the holder of e 1; s 2 is the holder of e 2; s 3 is the holder of e 3.

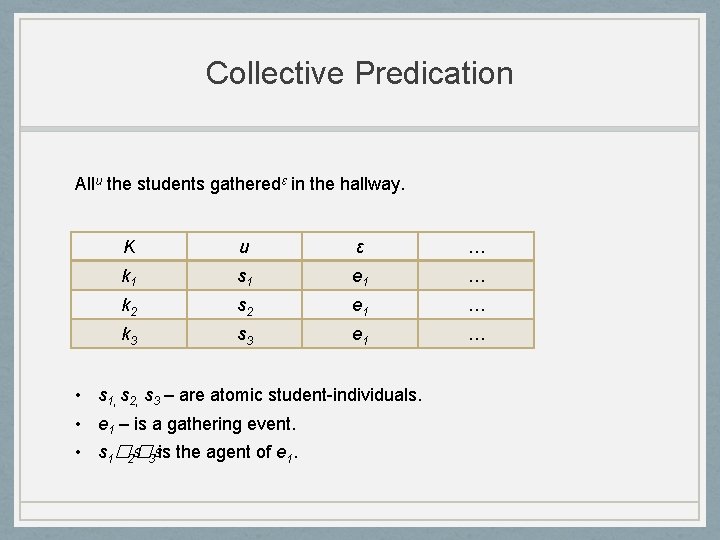

Collective Predication Allu the students gatheredε in the hallway. K u ε … k 1 s 1 e 1 … k 2 s 2 e 1 … k 3 s 3 e 1 … • s 1, s 2, s 3 – are atomic student-individuals. • e 1 – is a gathering event. • s 1�s 2�s 3 is the agent of e 1.

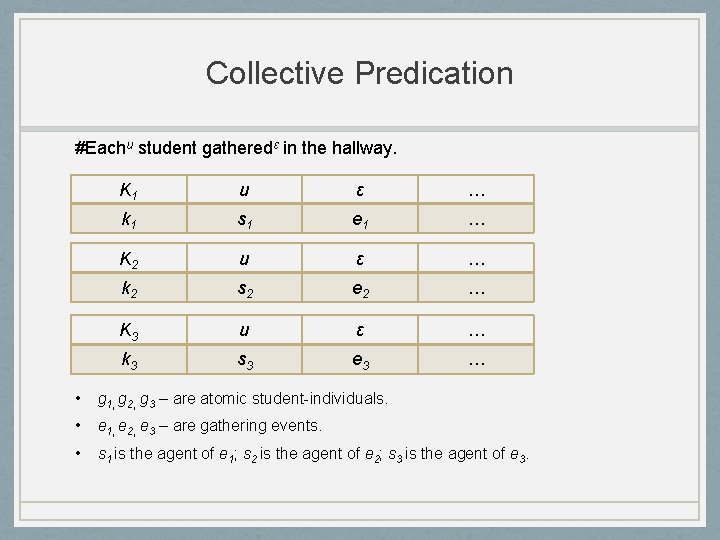

Collective Predication #Eachu student gatheredε in the hallway. K 1 u ε … k 1 s 1 e 1 … K 2 u ε … k 2 s 2 e 2 … K 3 u ε … k 3 s 3 e 3 … • g 1, g 2, g 3 – are atomic student-individuals. • e 1, e 2, e 3 – are gathering events. • s 1 is the agent of e 1; s 2 is the agent of e 2; s 3 is the agent of e 3.

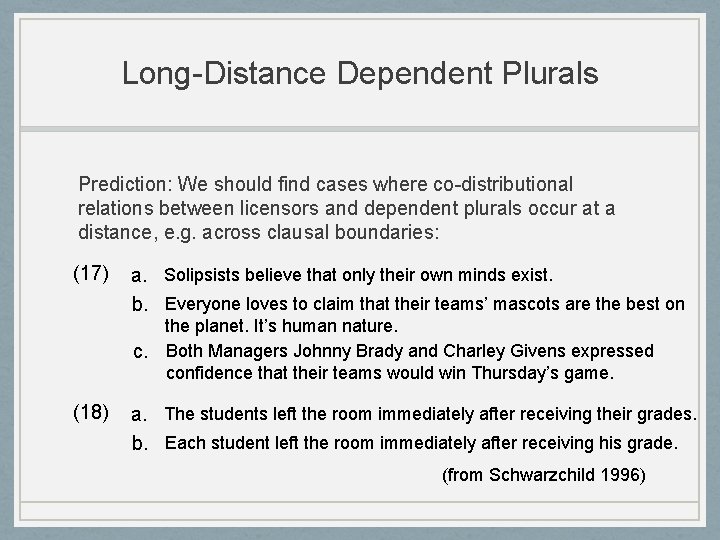

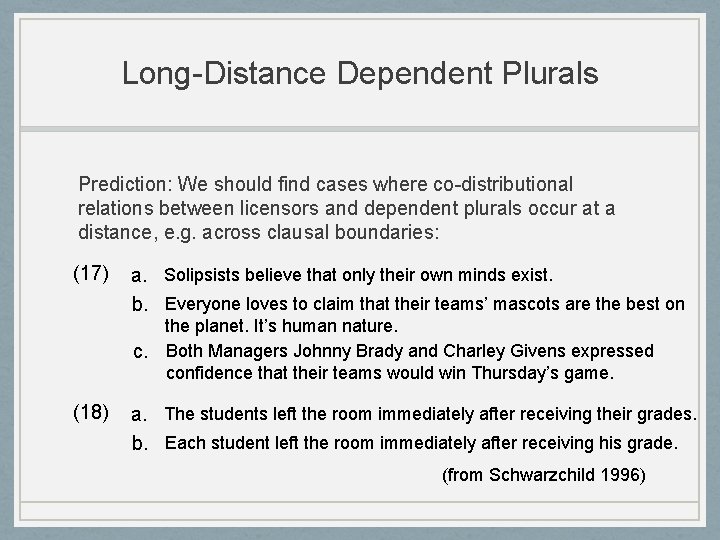

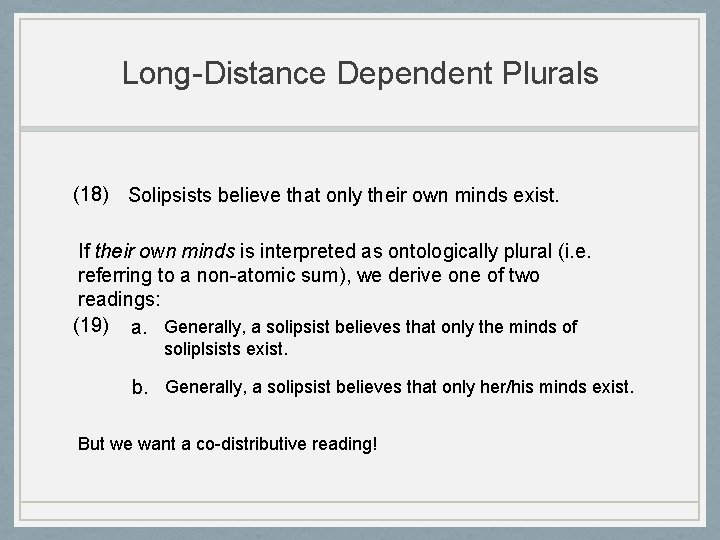

Long-Distance Dependent Plurals Prediction: We should find cases where co-distributional relations between licensors and dependent plurals occur at a distance, e. g. across clausal boundaries: (17) a. Solipsists believe that only their own minds exist. b. Everyone loves to claim that their teams’ mascots are the best on the planet. It’s human nature. c. Both Managers Johnny Brady and Charley Givens expressed confidence that their teams would win Thursday’s game. (18) a. The students left the room immediately after receiving their grades. b. Each student left the room immediately after receiving his grade. (from Schwarzchild 1996)

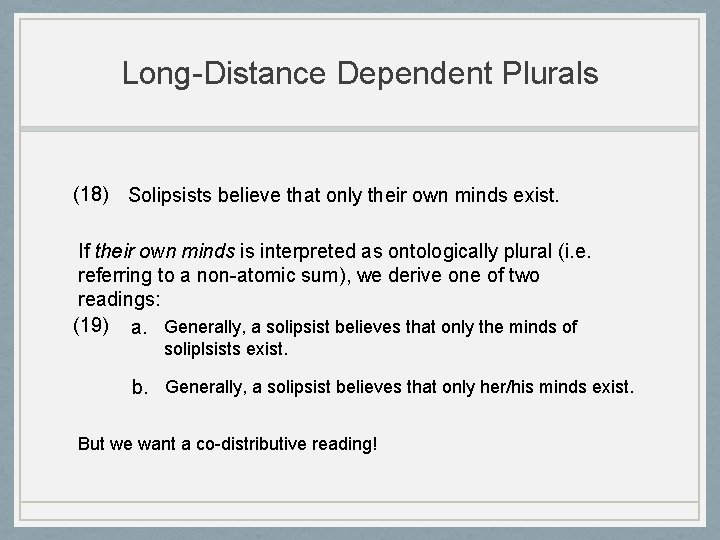

Long-Distance Dependent Plurals (18) Solipsists believe that only their own minds exist. If their own minds is interpreted as ontologically plural (i. e. referring to a non-atomic sum), we derive one of two readings: (19) a. Generally, a solipsist believes that only the minds of soliplsists exist. b. Generally, a solipsist believes that only her/his minds exist. But we want a co-distributive reading!

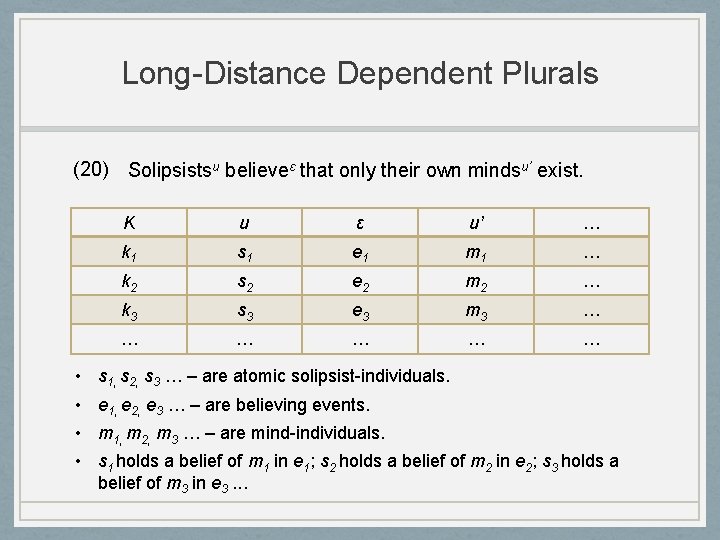

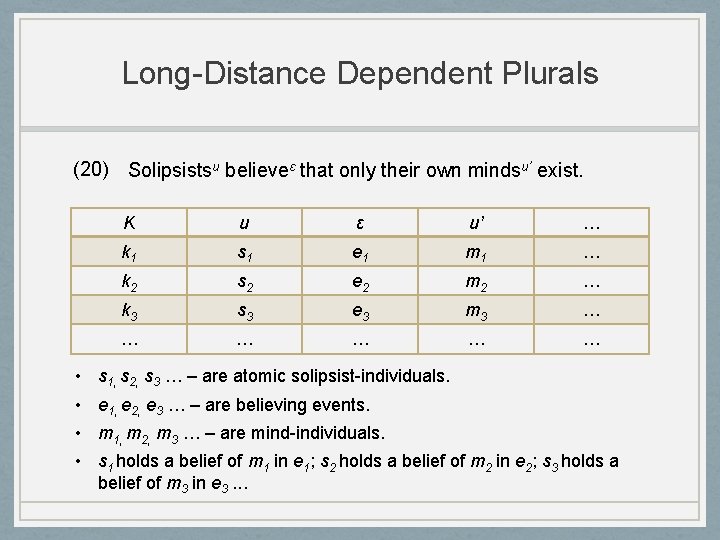

Long-Distance Dependent Plurals (20) Solipsistsu believeε that only their own mindsu’ exist. K u ε u’ … k 1 s 1 e 1 m 1 … k 2 s 2 e 2 m 2 … k 3 s 3 e 3 m 3 … … … • s 1, s 2, s 3 … – are atomic solipsist-individuals. • e 1, e 2, e 3 … – are believing events. • m 1, m 2, m 3 … – are mind-individuals. • s 1 holds a belief of m 1 in e 1; s 2 holds a belief of m 2 in e 2; s 3 holds a belief of m 3 in e 3. . .

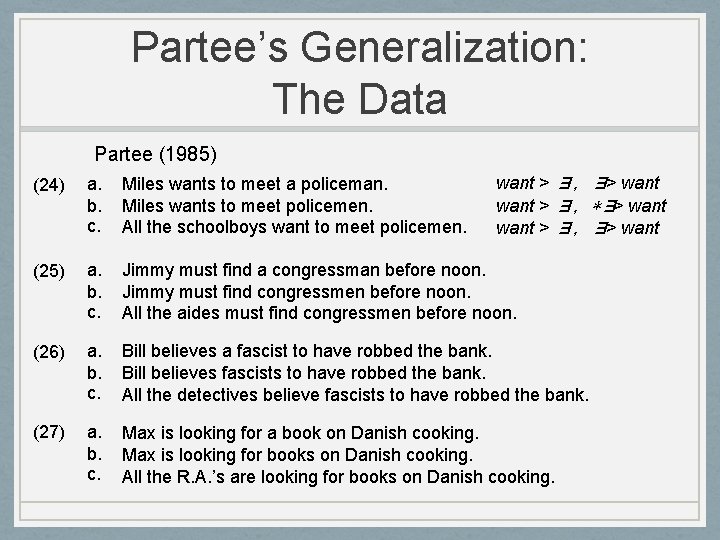

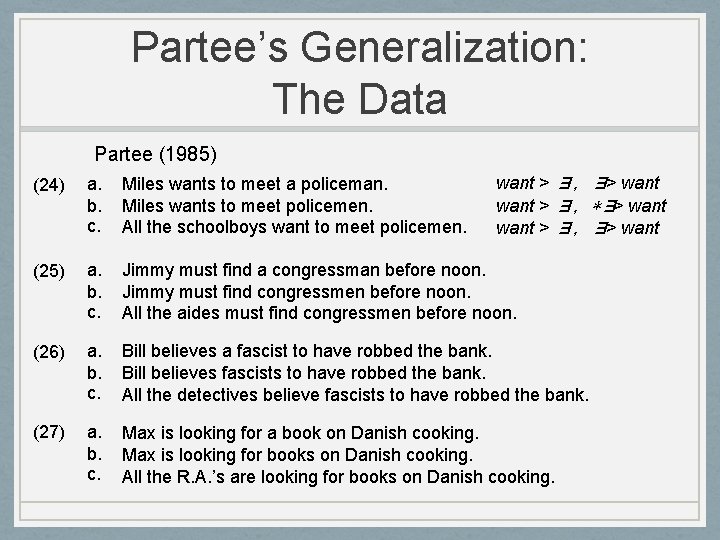

Partee’s Generalization: The Data Partee (1985) want > ∃, ∃> want > ∃, *∃> want > ∃, ∃> want (24) a. b. c. Miles wants to meet a policeman. Miles wants to meet policemen. All the schoolboys want to meet policemen. (25) a. b. c. Jimmy must find a congressman before noon. Jimmy must find congressmen before noon. All the aides must find congressmen before noon. (26) a. b. c. Bill believes a fascist to have robbed the bank. Bill believes fascists to have robbed the bank. All the detectives believe fascists to have robbed the bank. (27) a. b. c. Max is looking for a book on Danish cooking. Max is looking for books on Danish cooking. All the R. A. ’s are looking for books on Danish cooking.

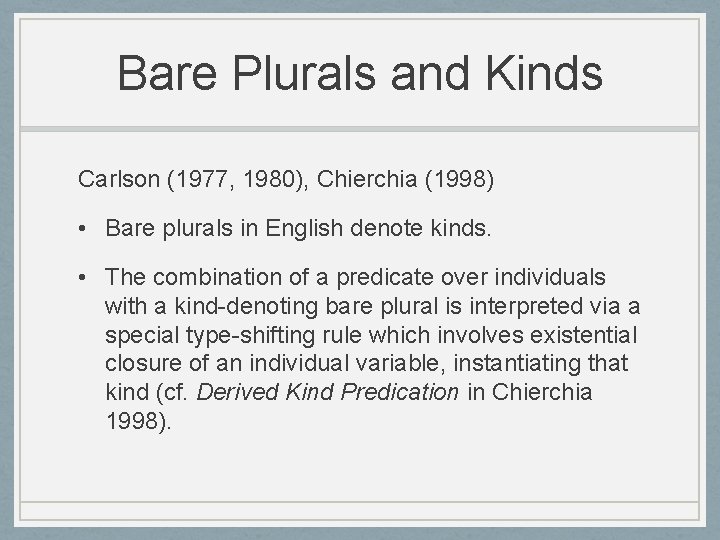

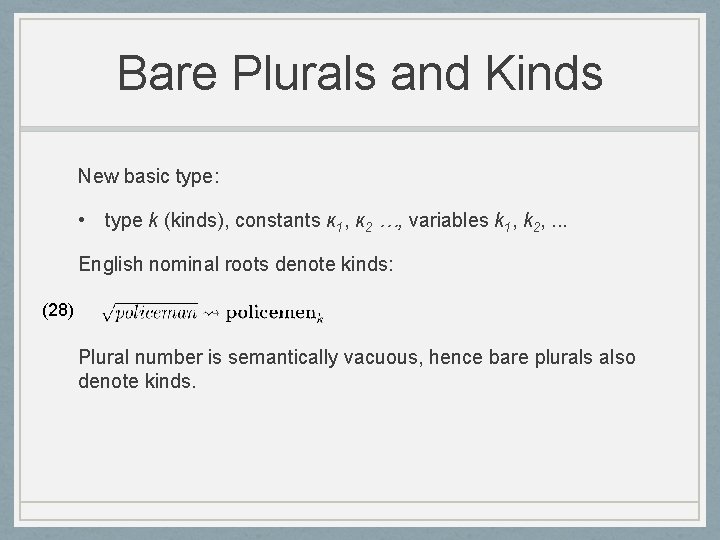

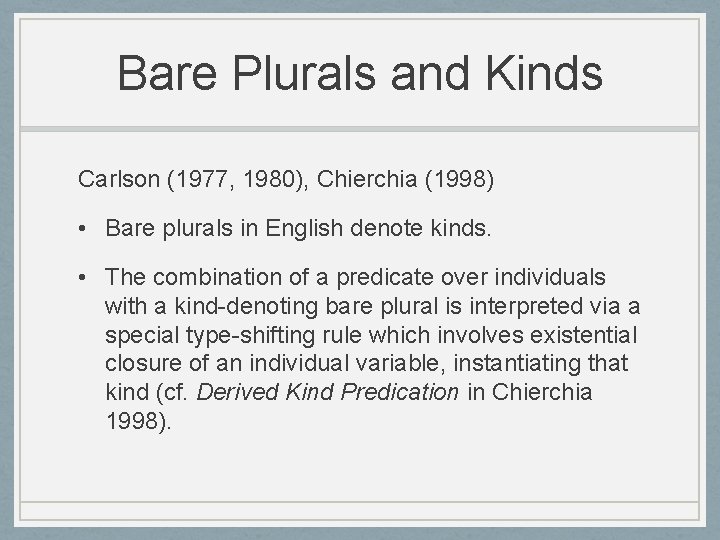

Bare Plurals and Kinds Carlson (1977, 1980), Chierchia (1998) • Bare plurals in English denote kinds. • The combination of a predicate over individuals with a kind-denoting bare plural is interpreted via a special type-shifting rule which involves existential closure of an individual variable, instantiating that kind (cf. Derived Kind Predication in Chierchia 1998).

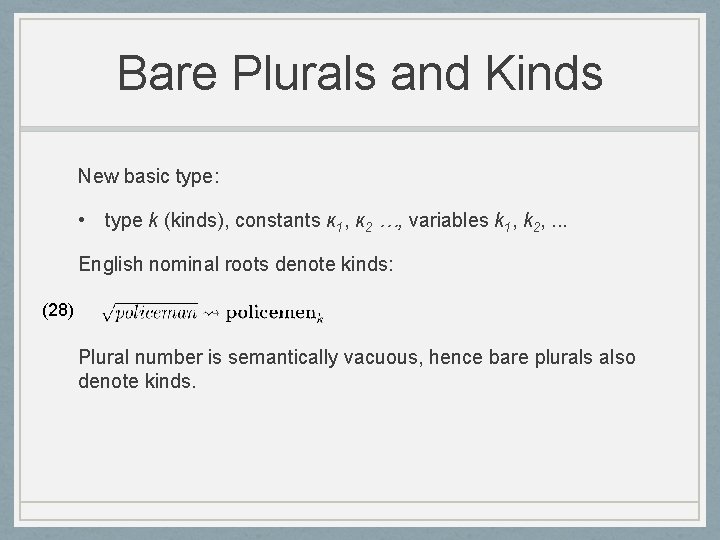

Bare Plurals and Kinds New basic type: • type k (kinds), constants κ 1, κ 2 …, variables k 1, k 2, . . . English nominal roots denote kinds: (28) Plural number is semantically vacuous, hence bare plurals also denote kinds.

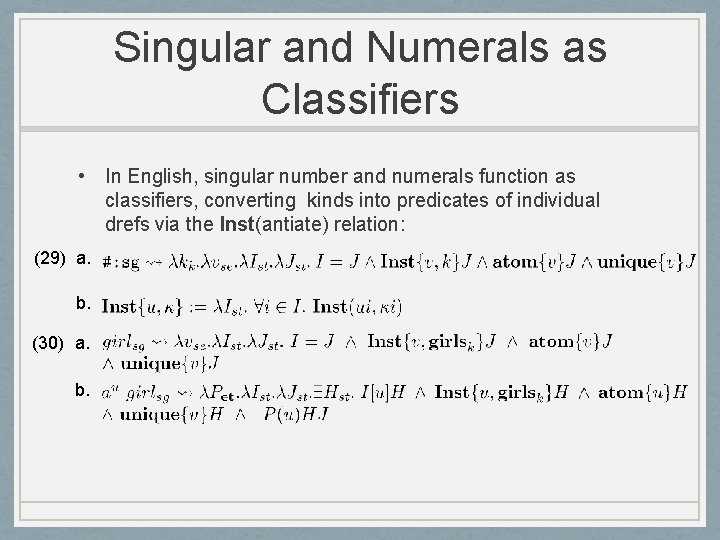

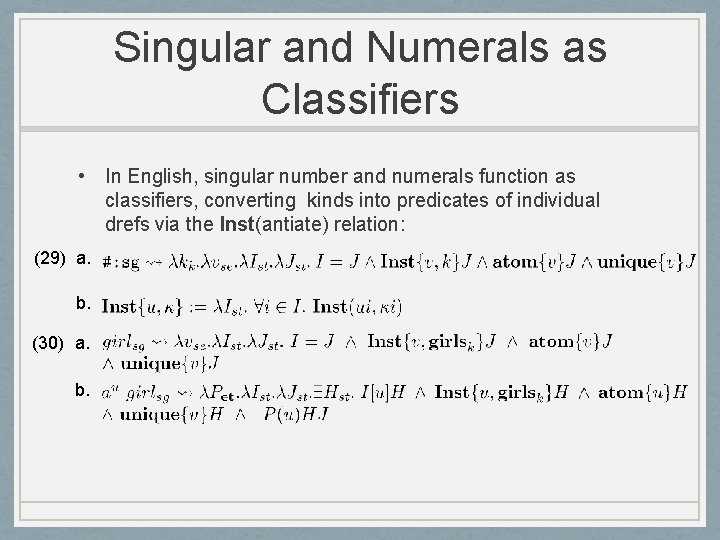

Singular and Numerals as Classifiers • In English, singular number and numerals function as classifiers, converting kinds into predicates of individual drefs via the Inst(antiate) relation: (29) a. b. (30) a. b.

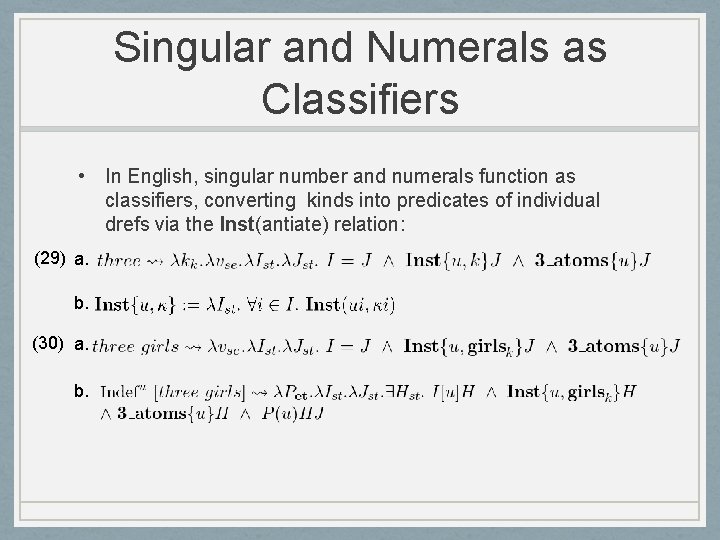

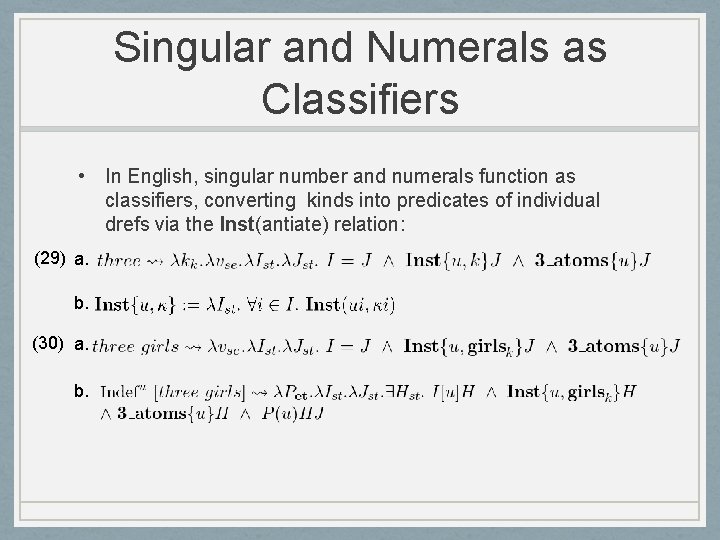

Singular and Numerals as Classifiers • In English, singular number and numerals function as classifiers, converting kinds into predicates of individual drefs via the Inst(antiate) relation: (29) a. b. (30) a. b.

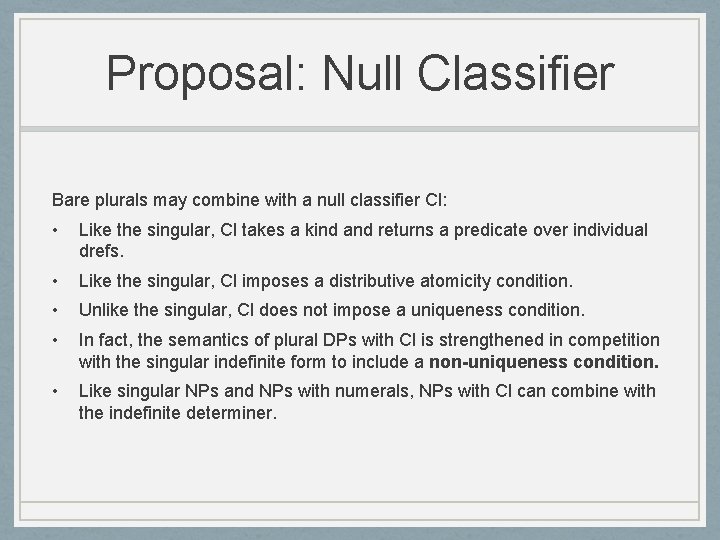

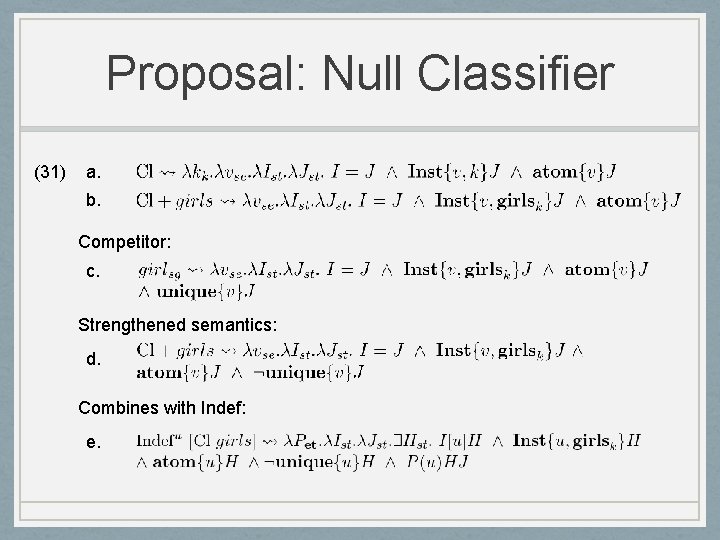

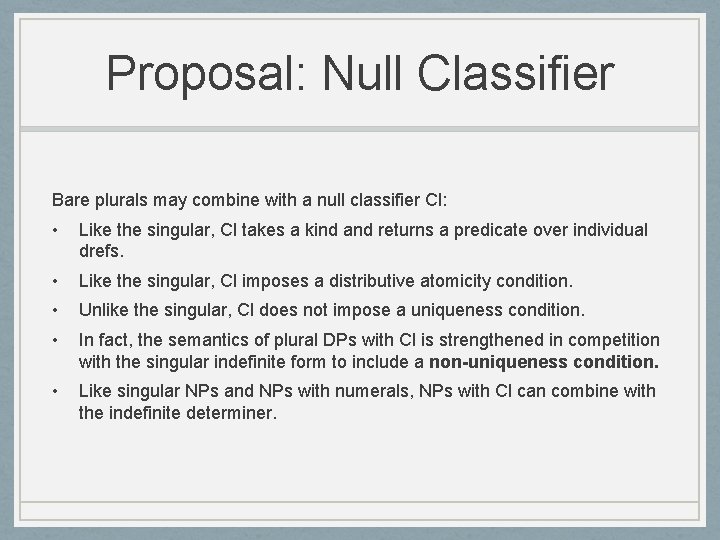

Proposal: Null Classifier Bare plurals may combine with a null classifier Cl: • Like the singular, Cl takes a kind and returns a predicate over individual drefs. • Like the singular, Cl imposes a distributive atomicity condition. • Unlike the singular, Cl does not impose a uniqueness condition. • In fact, the semantics of plural DPs with Cl is strengthened in competition with the singular indefinite form to include a non-uniqueness condition. • Like singular NPs and NPs with numerals, NPs with Cl can combine with the indefinite determiner.

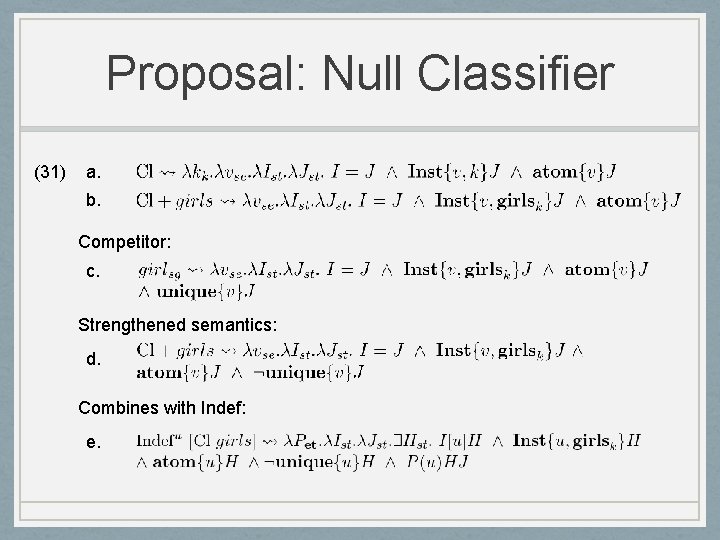

Proposal: Null Classifier (31) a. b. Competitor: c. Strengthened semantics: d. Combines with Indef: e.

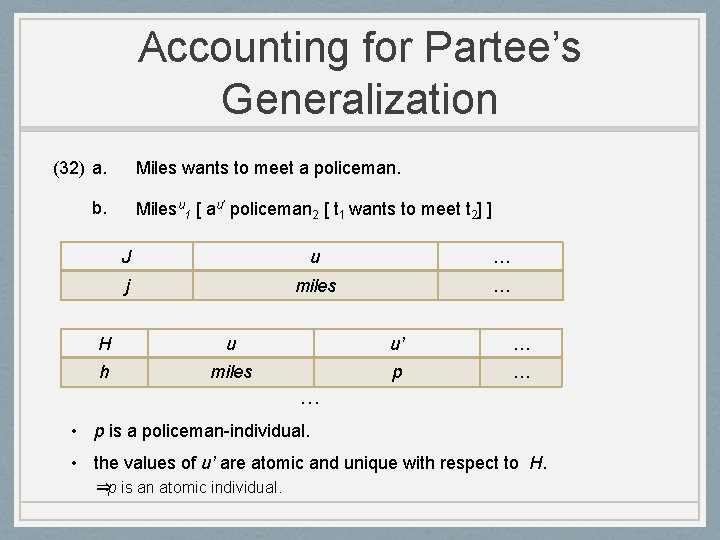

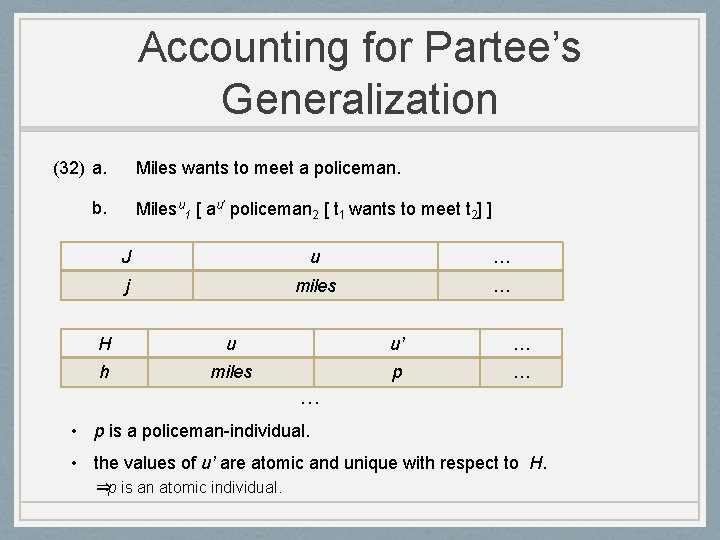

Accounting for Partee’s Generalization (32) a. Miles wants to meet a policeman. b. Milesu 1 [ au’ policeman 2 [ t 1 wants to meet t 2] ] J u … j miles … H u u’ … h miles p … … • p is a policeman-individual. • the values of u’ are atomic and unique with respect to H. ⇒p is an atomic individual.

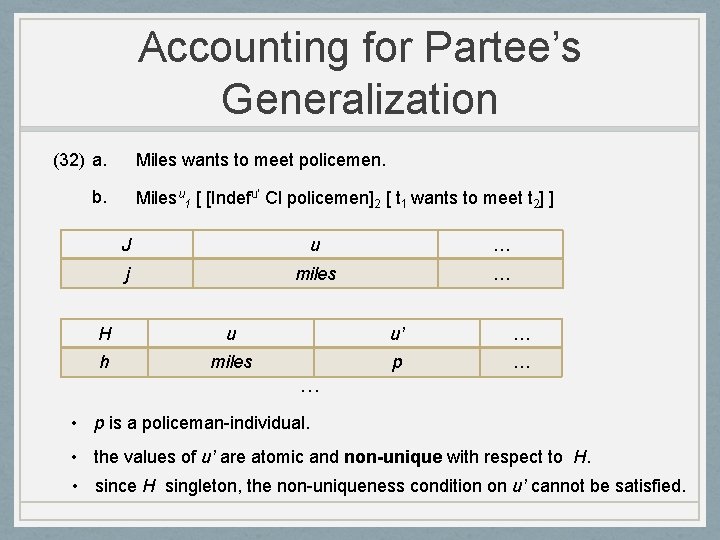

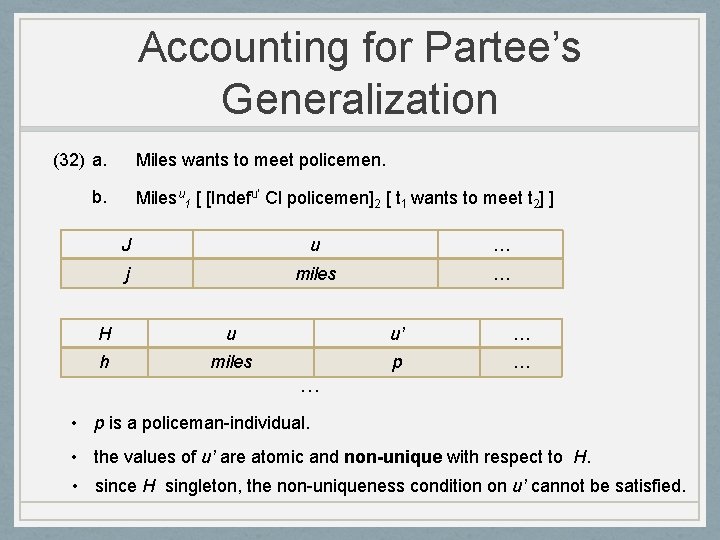

Accounting for Partee’s Generalization (32) a. Miles wants to meet policemen. b. Milesu 1 [ [Indefu’ Cl policemen]2 [ t 1 wants to meet t 2] ] J u … j miles … H u u’ … h miles p … … • p is a policeman-individual. • the values of u’ are atomic and non-unique with respect to H. • since H singleton, the non-uniqueness condition on u’ cannot be satisfied.

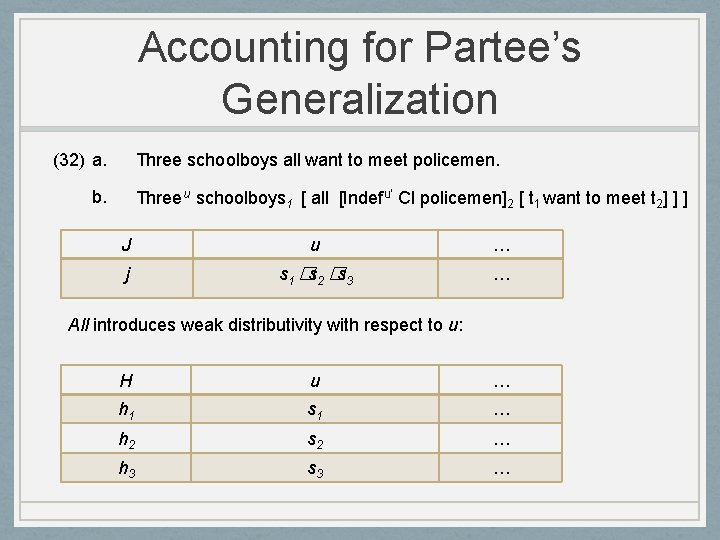

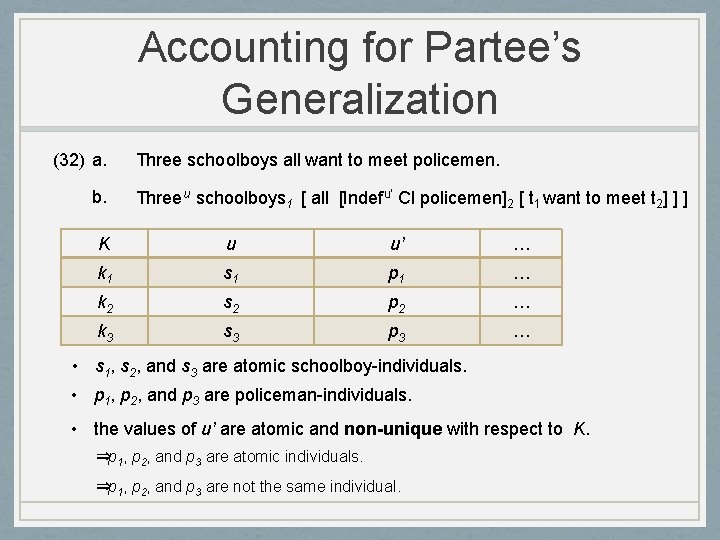

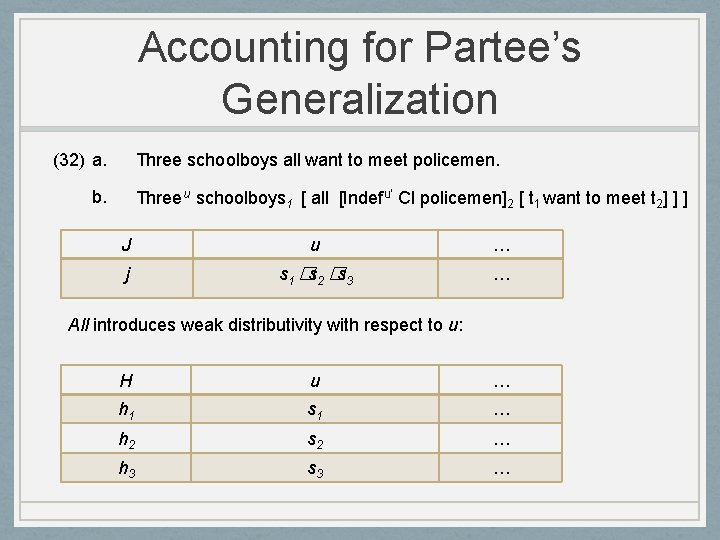

Accounting for Partee’s Generalization (32) a. Three schoolboys all want to meet policemen. b. Threeu schoolboys 1 [ all [Indefu’ Cl policemen]2 [ t 1 want to meet t 2] ] ] J u … j s 1 �s 2 �s 3 … All introduces weak distributivity with respect to u: H u … h 1 s 1 … h 2 s 2 … h 3 s 3 …

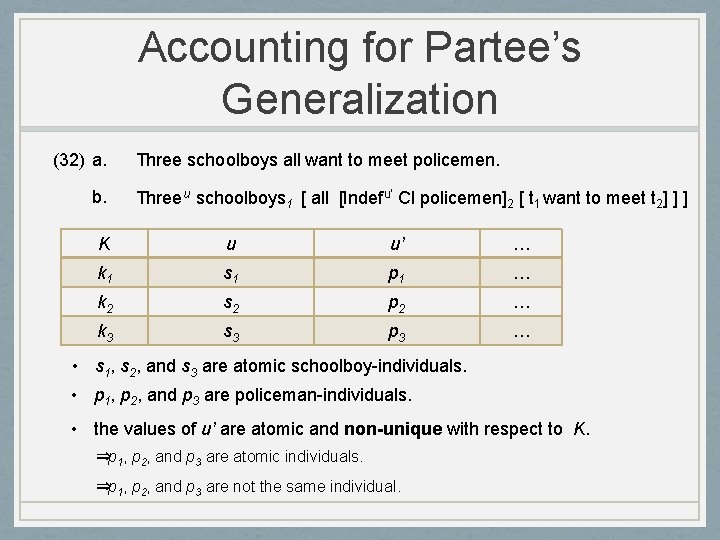

Accounting for Partee’s Generalization (32) a. b. Three schoolboys all want to meet policemen. Threeu schoolboys 1 [ all [Indefu’ Cl policemen]2 [ t 1 want to meet t 2] ] ] K u u’ … k 1 s 1 p 1 … k 2 s 2 p 2 … k 3 s 3 p 3 … • s 1, s 2, and s 3 are atomic schoolboy-individuals. • p 1, p 2, and p 3 are policeman-individuals. • the values of u’ are atomic and non-unique with respect to K. ⇒p 1, p 2, and p 3 are atomic individuals. ⇒p 1, p 2, and p 3 are not the same individual.

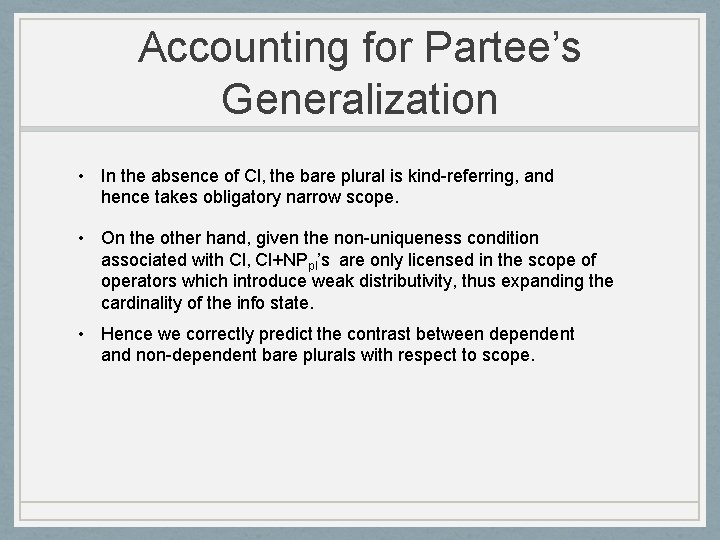

Accounting for Partee’s Generalization • In the absence of Cl, the bare plural is kind-referring, and hence takes obligatory narrow scope. • On the other hand, given the non-uniqueness condition associated with Cl, Cl+NPpl’s are only licensed in the scope of operators which introduce weak distributivity, thus expanding the cardinality of the info state. • Hence we correctly predict the contrast between dependent and non-dependent bare plurals with respect to scope.

Conclusions • A semantic system with plural info states allows for a natural formalization of a) the distinction between weak and strong distributivity, and b) ontological and state-level plurality. • These distinctions allow us to account for the three-way contrast between non-quantificational DPs (nondistributive), DPs involving plural quantifiers (weakly distributive), and DPs involving singular quantifiers (strongly distributive) • … and the contrast between cardinality modifiers (encode ontological cardinality conditions) and grammatical number features (make reference to state-level (non-)uniqueness).

Conclusions • This approach allows for a unified account of dependent plural-licensing and collective predication. • It also correctly predicts the existence of long-distance dependent plurals. • Finally, I have argued that the proposed system for the first time opens the way to an account of Partee’s Generalization concerning the scopal properties of English dependent and non-dependent bare plurals.

Thank you!

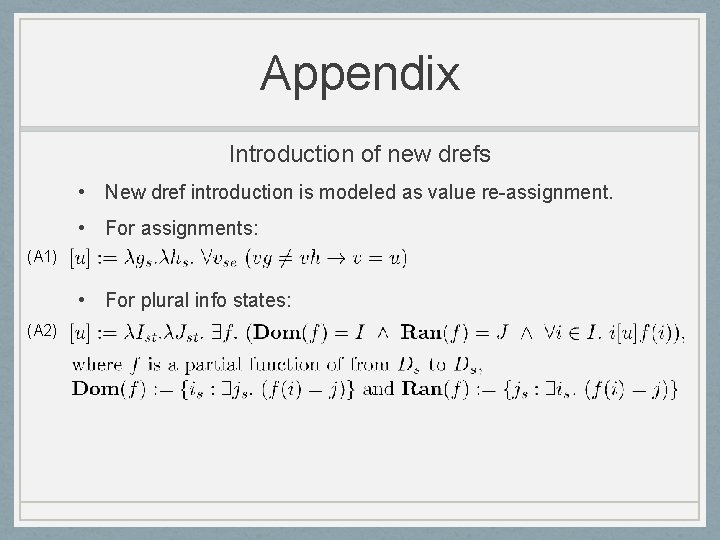

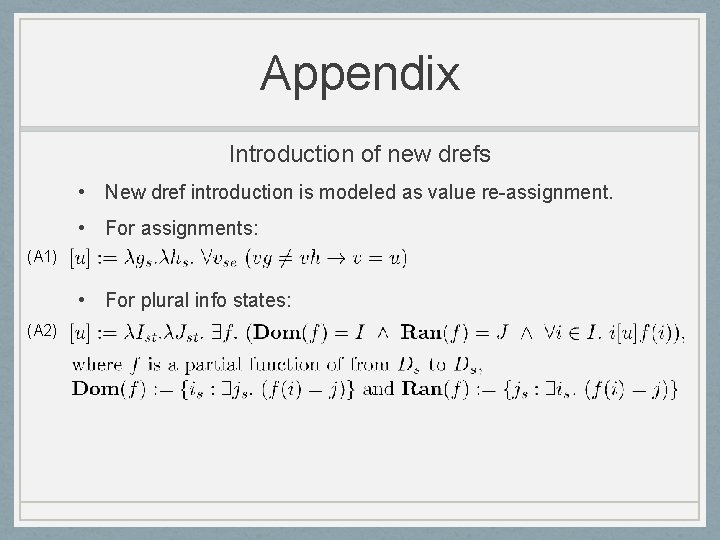

Appendix Introduction of new drefs • New dref introduction is modeled as value re-assignment. • For assignments: (A 1) • For plural info states: (A 2)

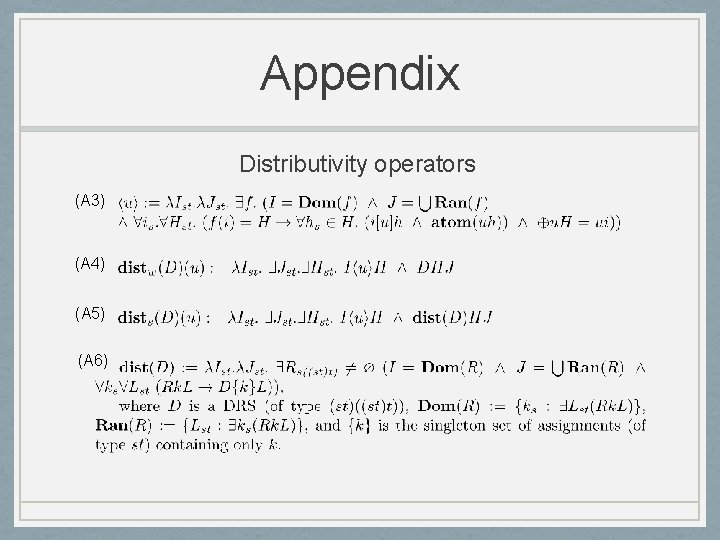

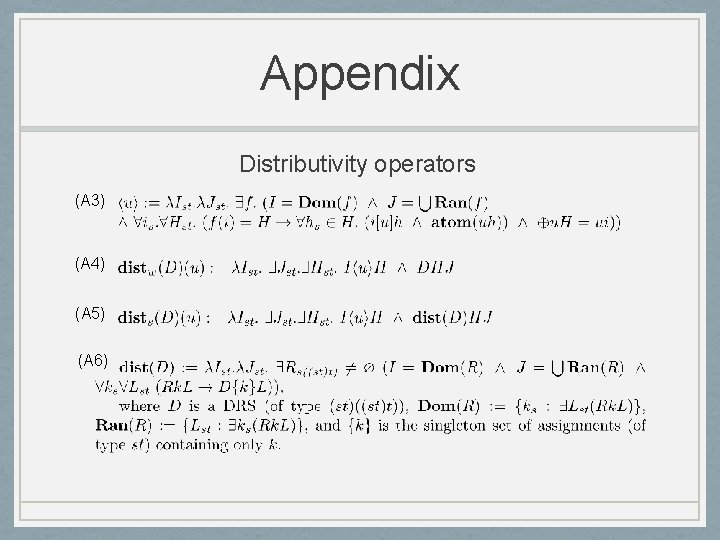

Appendix Distributivity operators (A 3) (A 4) (A 5) (A 6)

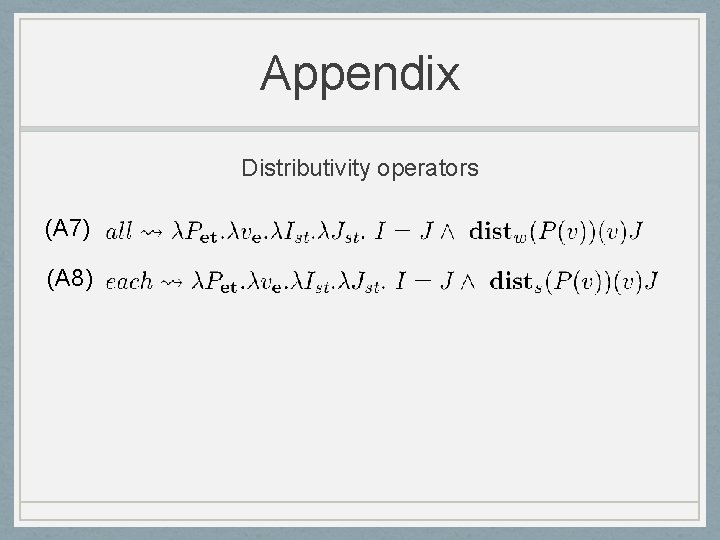

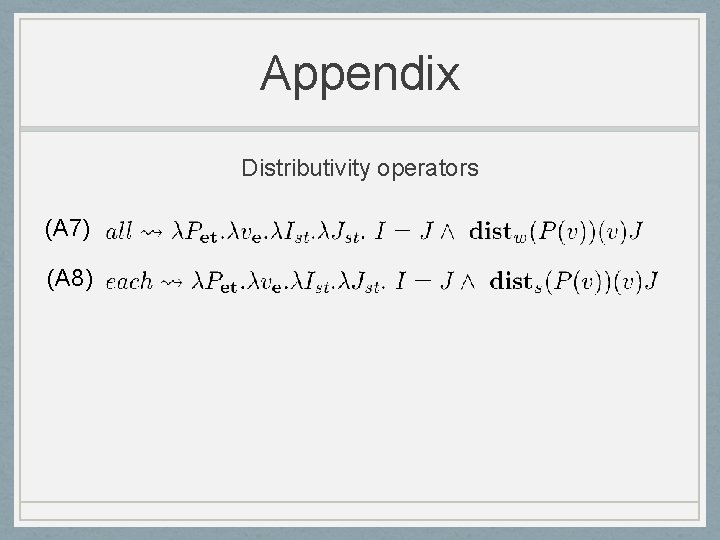

Appendix Distributivity operators (A 7) (A 8)

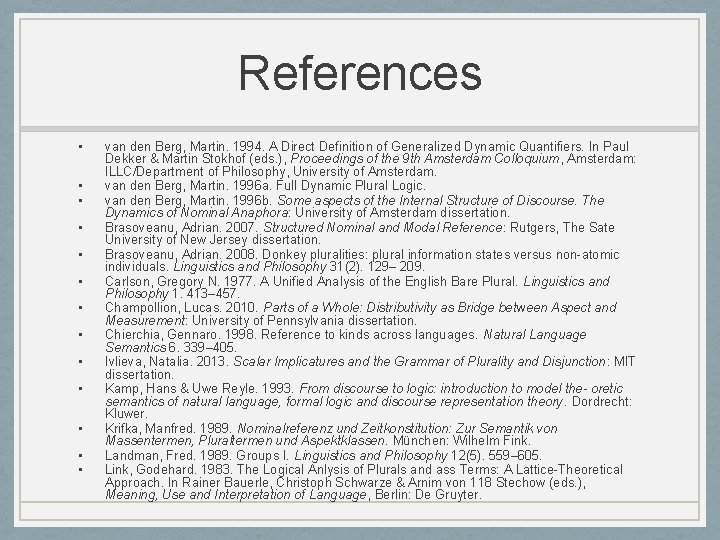

References • • • • van den Berg, Martin. 1994. A Direct Definition of Generalized Dynamic Quantifiers. In Paul Dekker & Martin Stokhof (eds. ), Proceedings of the 9 th Amsterdam Colloquium, Amsterdam: ILLC/Department of Philosophy, University of Amsterdam. van den Berg, Martin. 1996 a. Full Dynamic Plural Logic. van den Berg, Martin. 1996 b. Some aspects of the Internal Structure of Discourse. The Dynamics of Nominal Anaphora: University of Amsterdam dissertation. Brasoveanu, Adrian. 2007. Structured Nominal and Modal Reference: Rutgers, The Sate University of New Jersey dissertation. Brasoveanu, Adrian. 2008. Donkey pluralities: plural information states versus non-atomic individuals. Linguistics and Philosophy 31(2). 129– 209. Carlson, Gregory N. 1977. A Unified Analysis of the English Bare Plural. Linguistics and Philosophy 1. 413– 457. Champollion, Lucas. 2010. Parts of a Whole: Distributivity as Bridge between Aspect and Measurement: University of Pennsylvania dissertation. Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across languages. Natural Language Semantics 6. 339– 405. Ivlieva, Natalia. 2013. Scalar Implicatures and the Grammar of Plurality and Disjunction: MIT dissertation. Kamp, Hans & Uwe Reyle. 1993. From discourse to logic: introduction to model the- oretic semantics of natural language, formal logic and discourse representation theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Krifka, Manfred. 1989. Nominalreferenz und Zeitkonstitution: Zur Semantik von Massentermen, Pluraltermen und Aspektklassen. München: Wilhelm Fink. Landman, Fred. 1989. Groups I. Linguistics and Philosophy 12(5). 559– 605. Link, Godehard. 1983. The Logical Anlysis of Plurals and ass Terms: A Lattice-Theoretical Approach. In Rainer Bauerle, Christoph Schwarze & Arnim von 118 Stechow (eds. ), Meaning, Use and Interpretation of Language, Berlin: De Gruyter.

References • • Muskens, Richard. 1996. Combining Montague semantics and discourse representation. Linguistics and Philosophy 19. 143– 186. Partee, Barbara H. 1975. Comments on C. J. Fillmore’s and N. Chomsky’s papers. In Robert Austerlitz (ed. ), Scope of American Linguistics, 197– 209. Lisse: The Peter De Ridder Press. Partee, Barbara H. 1985. “Dependent Plurals” Are Distinct From Bare Plurals. Sauerland, Uli. 1998. Plurals, Derived Predicates and Reciprocals. In Uli Sauerland & Orin Percus (eds. ), The Interpretive Tract, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 25, Cambridge, MA. Spector, Benjamin. 2003. Plural indefinite DPs as PLURAL-polarity items. In Joseph Quer, Jan Shroten, Mauro Scorretti, Petra Sleeman & Els Verheugd (eds. ), Romance languages and linguistic theory 2001: Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Sternefeld, Wolfgang. 1998. Reciprocity and Cumulative Predication. Natu- ral language semantics 303– 337. Zweig, Eytan. 2008. Dependent Plurals and Plural Meaning: New York University dissertation. Zweig, Eytan. 2009. Number-Neutral Bare plurals and the Multiplicity Implicature. Linguistics and Philosophy 32. 353– 407.

Contraction vs possessive

Contraction vs possessive Write the possessive form of the noun in parentheses

Write the possessive form of the noun in parentheses Possessive noun

Possessive noun The verb jugar (p. 208) answers

The verb jugar (p. 208) answers Advice plural form

Advice plural form Definite and indefinite articles spanish

Definite and indefinite articles spanish Costas levels of questioning

Costas levels of questioning Serge delfos

Serge delfos Edmond vidal et sa femme

Edmond vidal et sa femme Serge rozenberg

Serge rozenberg Serge abiteboul

Serge abiteboul Serge rubinstein

Serge rubinstein Serge kreiker

Serge kreiker Jaqueline ginsburg

Jaqueline ginsburg Serge lama je voudrais tant que tu sois là

Serge lama je voudrais tant que tu sois là Serge hanna

Serge hanna Ecusson sdmis

Ecusson sdmis Serge faure

Serge faure Je voudrais tant que tu sois la

Je voudrais tant que tu sois la Serge dezutter

Serge dezutter Serge hanna

Serge hanna Que manger avant un match de tennis

Que manger avant un match de tennis Serge duarte

Serge duarte Tissu natté | tissage natté | armure nattée

Tissu natté | tissage natté | armure nattée Serge hanna

Serge hanna Serge duarte

Serge duarte Pr serge halimi

Pr serge halimi 31 rue de seine

31 rue de seine Serge hanna

Serge hanna Serge bard proviseur

Serge bard proviseur Serge tisseron

Serge tisseron Serge yattah

Serge yattah Serge lama marie la polonaise

Serge lama marie la polonaise Serge rezzi

Serge rezzi Serge tinland

Serge tinland Zeros and multiplicity

Zeros and multiplicity Dualism multiplicity and relativism

Dualism multiplicity and relativism Father of dactyloscopy

Father of dactyloscopy Multiplicity and end behavior

Multiplicity and end behavior Plural forms of words

Plural forms of words Plural form bus

Plural form bus Plural flowers

Plural flowers Plurals words ending in ch sh s x worksheets

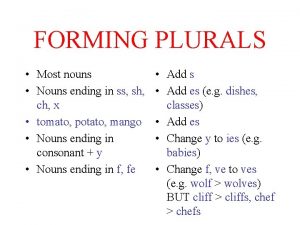

Plurals words ending in ch sh s x worksheets Most nouns form their plurals by adding

Most nouns form their plurals by adding Is tea a noun

Is tea a noun Standart plural

Standart plural Plurals of flower

Plurals of flower Objective plural

Objective plural 30 singular and plural

30 singular and plural Plurals tooth

Plurals tooth What is the plural form of calf

What is the plural form of calf Special plurals

Special plurals Odd vs even multiplicity

Odd vs even multiplicity Cardinality vs multiplicity

Cardinality vs multiplicity Magnifying class

Magnifying class Multiplicity math

Multiplicity math Whats the end behavior of a graph

Whats the end behavior of a graph Finding real roots of polynomial equations examples

Finding real roots of polynomial equations examples Cardinality vs multiplicity

Cardinality vs multiplicity Enzyme multiplicity

Enzyme multiplicity Geometric multiplicity

Geometric multiplicity Eigenvalues of orthogonal matrix

Eigenvalues of orthogonal matrix Cardinality vs multiplicity

Cardinality vs multiplicity Contoh multiplicity class diagram

Contoh multiplicity class diagram Multiplicity in ooad

Multiplicity in ooad Multiplicity indicator to denote optional association

Multiplicity indicator to denote optional association Multiplicity pada class diagram

Multiplicity pada class diagram Multiplicity indicator for optional association

Multiplicity indicator for optional association Multiplicity (mathematics)

Multiplicity (mathematics) Hubungan realisasi khusus antara classifier dan interface

Hubungan realisasi khusus antara classifier dan interface Multiplicity imdb

Multiplicity imdb Spin multiplicity

Spin multiplicity