CHOOSING IN GROUPS MUNGER AND MUNGER Slides for

- Slides: 24

CHOOSING IN GROUPS MUNGER AND MUNGER Slides for Chapter 4 The Analytics of Choosing in Groups

Outline of Chapter 4 § Definitions § Preferences, weak orders, and utility functions § Political preferences § Public goods and market failures § Consumer problem § Private goods § Public goods § Lindahl equilibrium § Representation of public preferences § Aggregation problem Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 2

Definitions § Preferences: Ordering of all alternatives; ties allowed § Rational if complete and transitive § Utility theory: Use of a mathematical function where utility depends on goods or state of the world § Under certain circumstances, utility can represent preferences § Representation: Mapping of preference profile onto family of utility functions § Binary relation: An ordered triple (X, X, S) in which X is mapped to S § Social choice function: A mapping of >1 preference profiles into a social utility function Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 3

Preference § Define a binary relation § “A B” means “A is at least as good as B” from the chooser’s perspective § A and B are both elements of X, the set of alternatives § (strict preference): If A § (strict indifference): If A B then A B but B B and B Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. A A All rights reserved. 4

Preference (2) § Reflexivity: The relation can be applied to one element, A § and are reflexive (A § Symmetry: If A § and B, then B A and A A), but A is not A are not symmetric; is symmetric § Transitivity: § Weak: if A B and B C, then C A § Strong: if A B and B C, then A C § We generally assume , and are transitive for individuals § Completeness: For any A and B in X, A B or B A § Any two alternatives can be compared Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 5

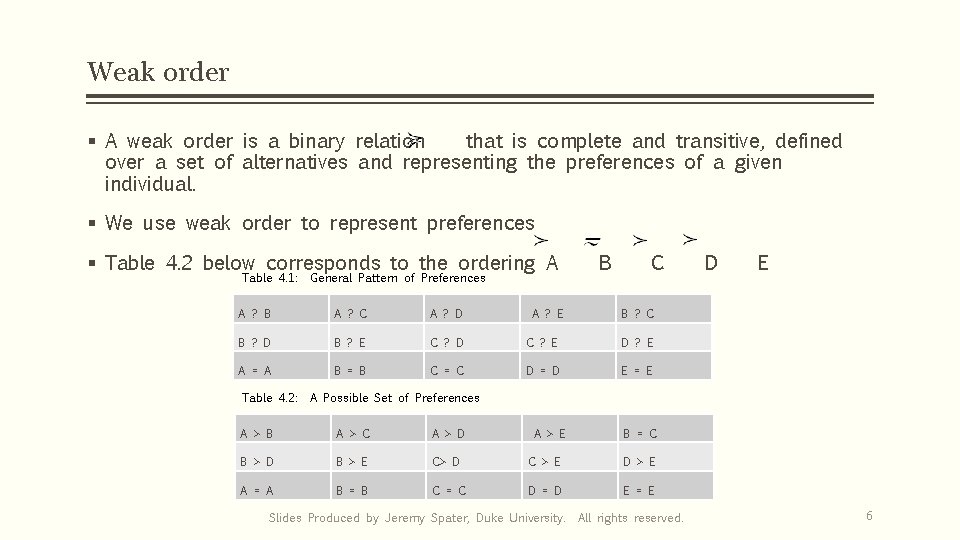

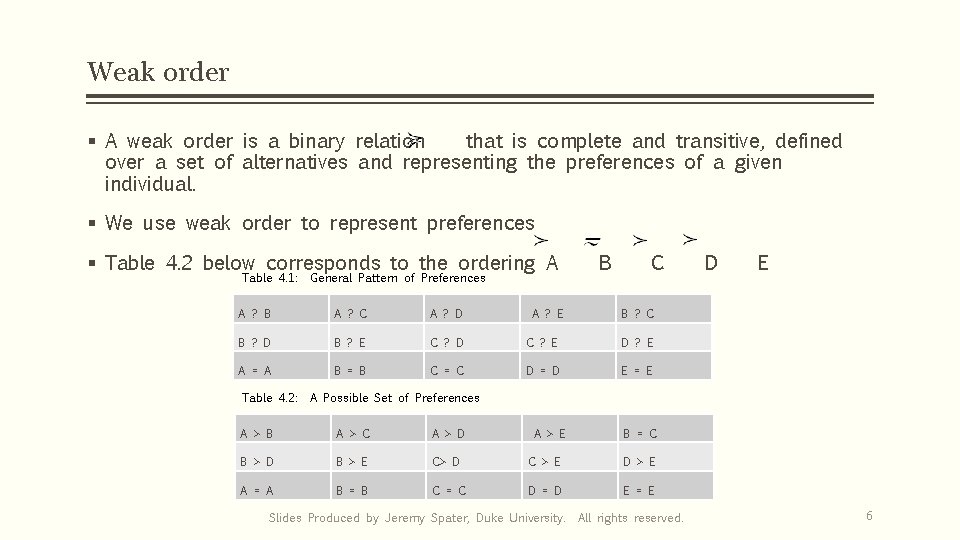

Weak order § A weak order is a binary relation that is complete and transitive, defined over a set of alternatives and representing the preferences of a given individual. § We use weak order to represent preferences § Table 4. 2 below corresponds to the ordering A Table 4. 1: General Pattern of Preferences C A ? B A ? C A ? D B ? E C ? D C ? E D ? E A ≂ A B ≂ B C ≂ C D ≂ D E ≂ E Table 4. 2: A ? E B D E B ? C A Possible Set of Preferences A ≻ B A ≻ C A ≻ D A ≻ E B ≻ D B ≻ E C≻ D C ≻ E D ≻ E A ≂ A B ≂ B C ≂ C D ≂ D E ≂ E Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. B ≂ C All rights reserved. 6

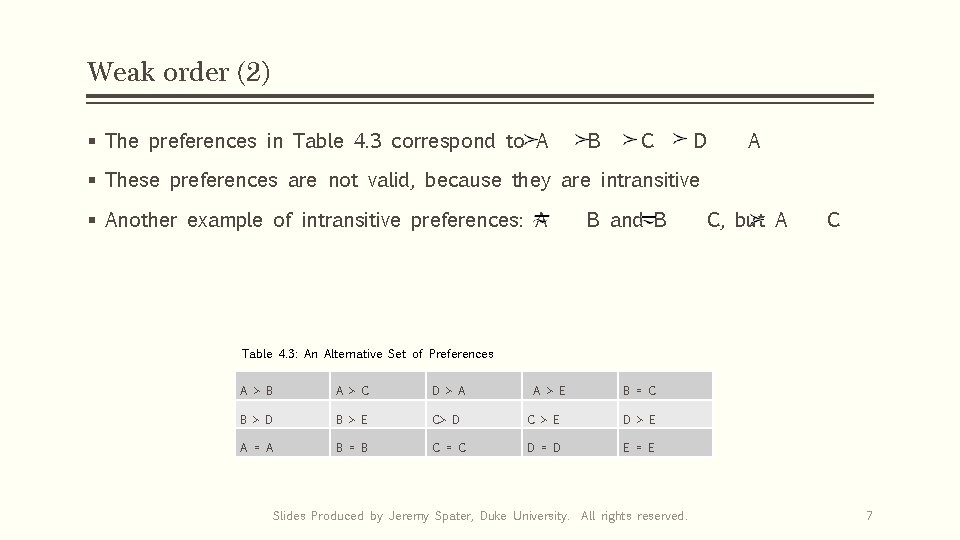

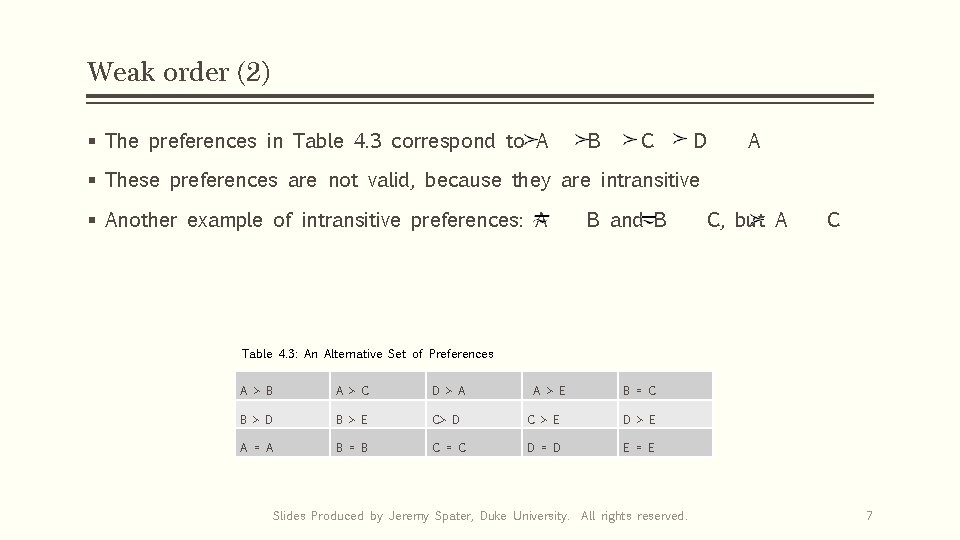

Weak order (2) § The preferences in Table 4. 3 correspond to A B C D A § These preferences are not valid, because they are intransitive § Another example of intransitive preferences: A B and B C, but A C Table 4. 3: An Alternative Set of Preferences A ≻ B A ≻ C D ≻ A A ≻ E B ≻ D B ≻ E C≻ D C ≻ E D ≻ E A ≂ A B ≂ B C ≂ C D ≂ D E ≂ E Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. B ≂ C All rights reserved. 7

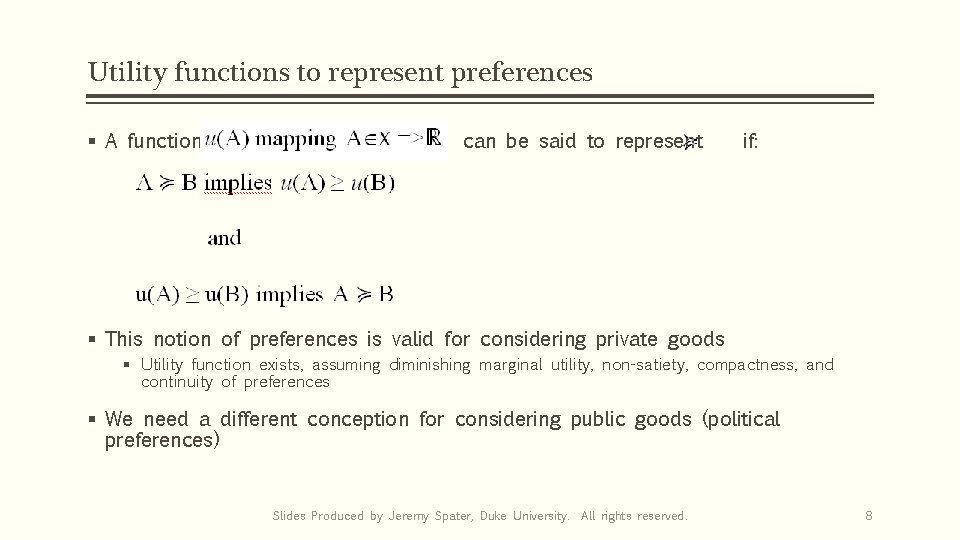

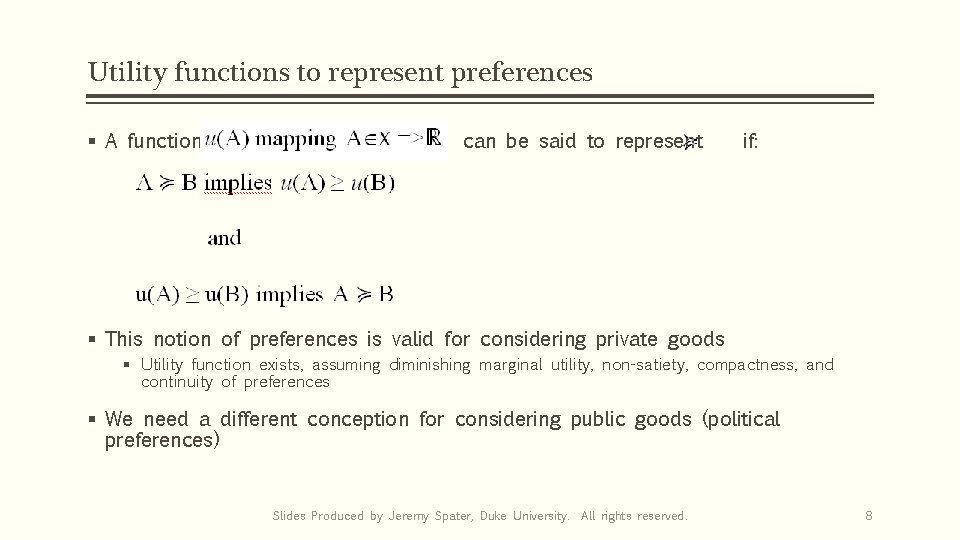

Utility functions to represent preferences § A function can be said to represent if: § This notion of preferences is valid for considering private goods § Utility function exists, assuming diminishing marginal utility, non-satiety, compactness, and continuity of preferences § We need a different conception for considering public goods (political preferences) Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 8

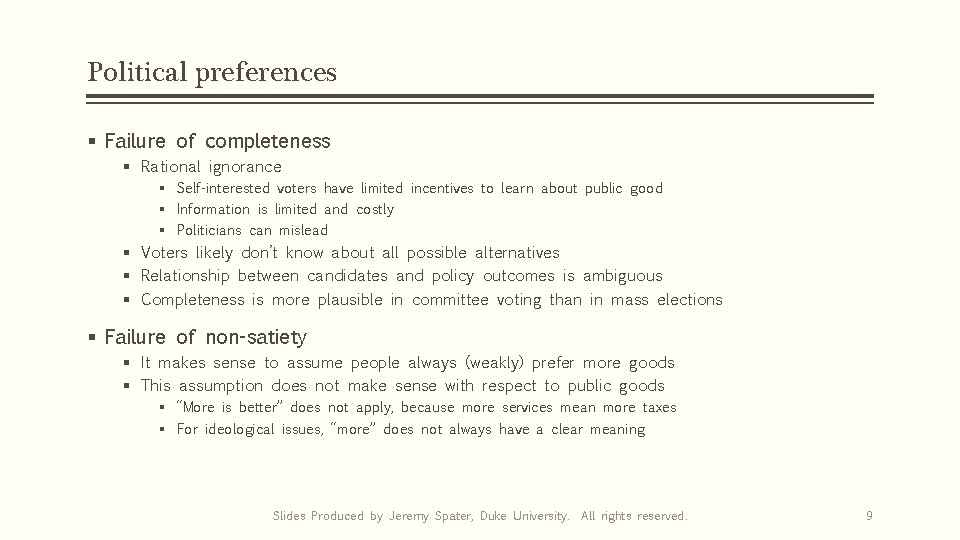

Political preferences § Failure of completeness § Rational ignorance § Self-interested voters have limited incentives to learn about public good § Information is limited and costly § Politicians can mislead § Voters likely don’t know about all possible alternatives § Relationship between candidates and policy outcomes is ambiguous § Completeness is more plausible in committee voting than in mass elections § Failure of non-satiety § It makes sense to assume people always (weakly) prefer more goods § This assumption does not make sense with respect to public goods § “More is better” does not apply, because more services mean more taxes § For ideological issues, “more” does not always have a clear meaning Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 9

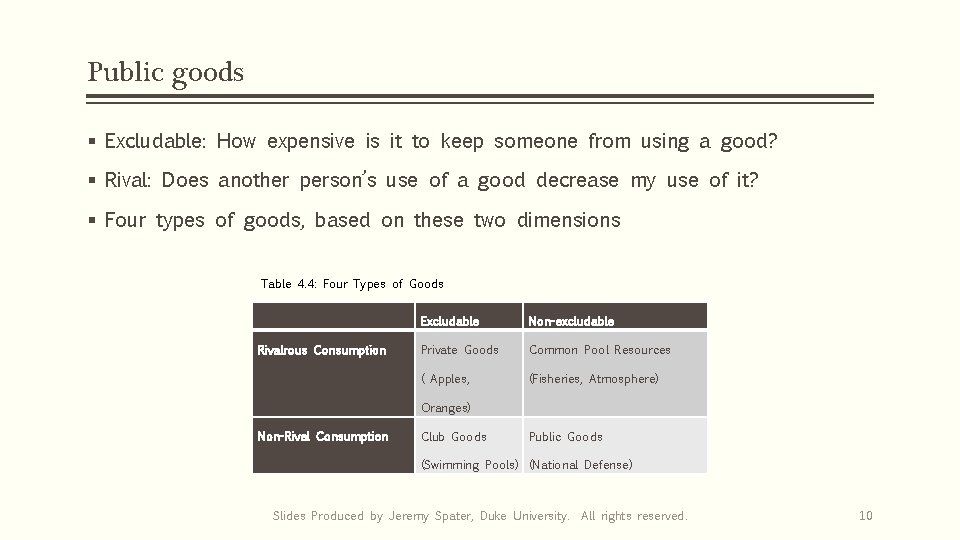

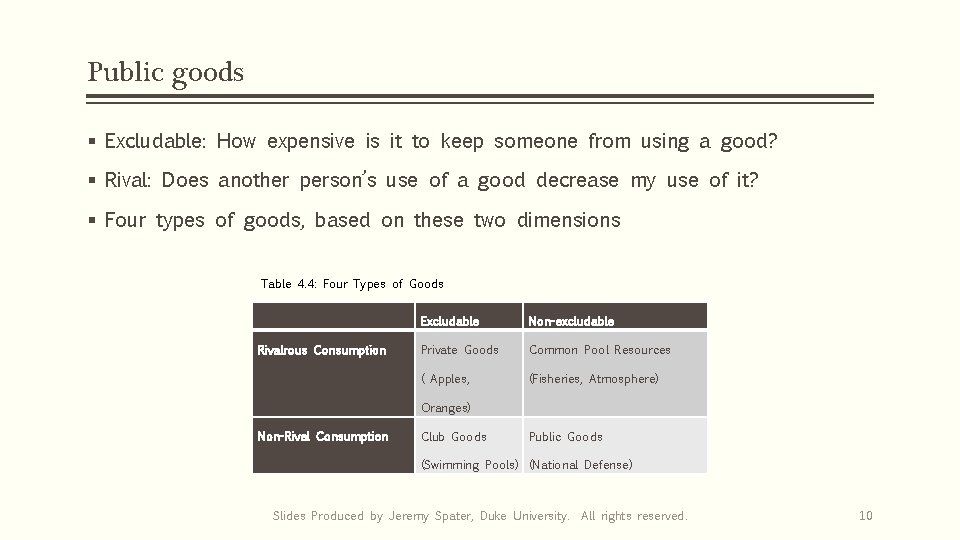

Public goods § Excludable: How expensive is it to keep someone from using a good? § Rival: Does another person’s use of a good decrease my use of it? § Four types of goods, based on these two dimensions Table 4. 4: Four Types of Goods Excludable Non-excludable Rivalrous Consumption Private Goods Common Pool Resources ( Apples, (Fisheries, Atmosphere) Oranges) Non-Rival Consumption Club Goods Public Goods (Swimming Pools) (National Defense) Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 10

Public goods (2) § Political choice: § Who (individual or group) determines supply and allocation of different types of goods? § Sometimes public goods are determined privately, and vice versa § Considerable variation exists among nations § Market failures § Club goods: Acting individually, people supply less than the optimal amount § Common pool goods: “Tragedy of the commons”: resources are overused § Public goods: “Free rider problem”: Individuals prefer to let someone else produce the good Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 11

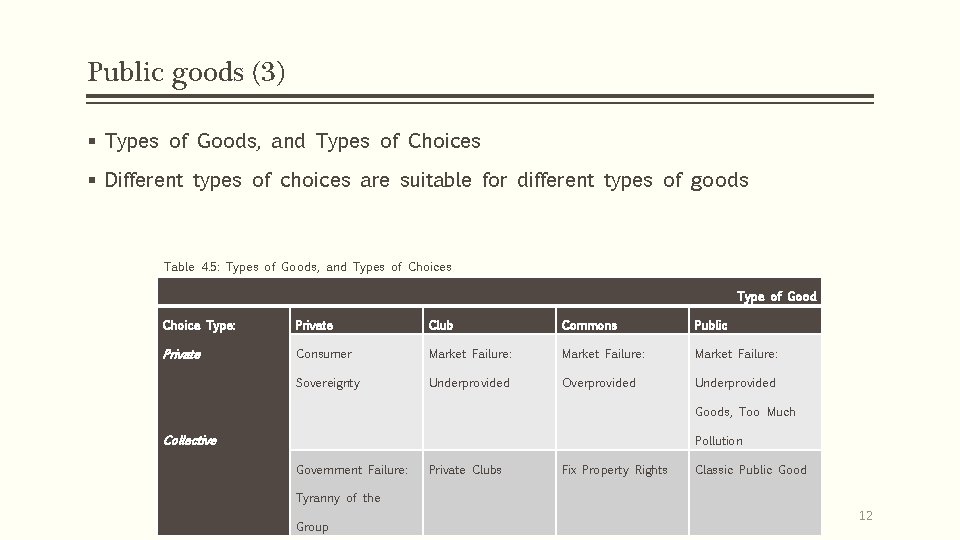

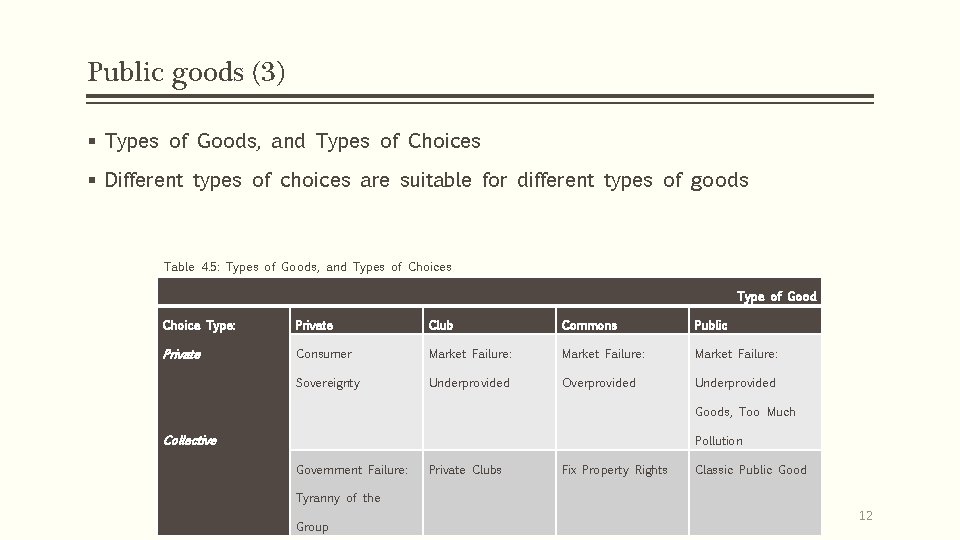

Public goods (3) § Types of Goods, and Types of Choices § Different types of choices are suitable for different types of goods Table 4. 5: Types of Goods, and Types of Choices Type of Good Choice Type: Private Club Commons Public Private Consumer Market Failure: Sovereignty Underprovided Overprovided Underprovided Goods, Too Much Collective Pollution Government Failure: Private Clubs Fix Property Rights Tyranny of the Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. Group All rights reserved. Classic Public Good 12

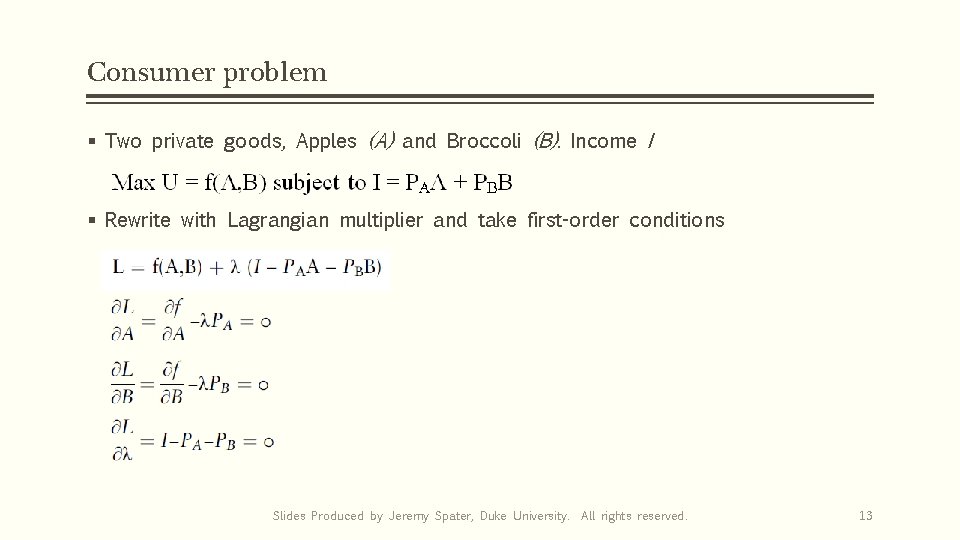

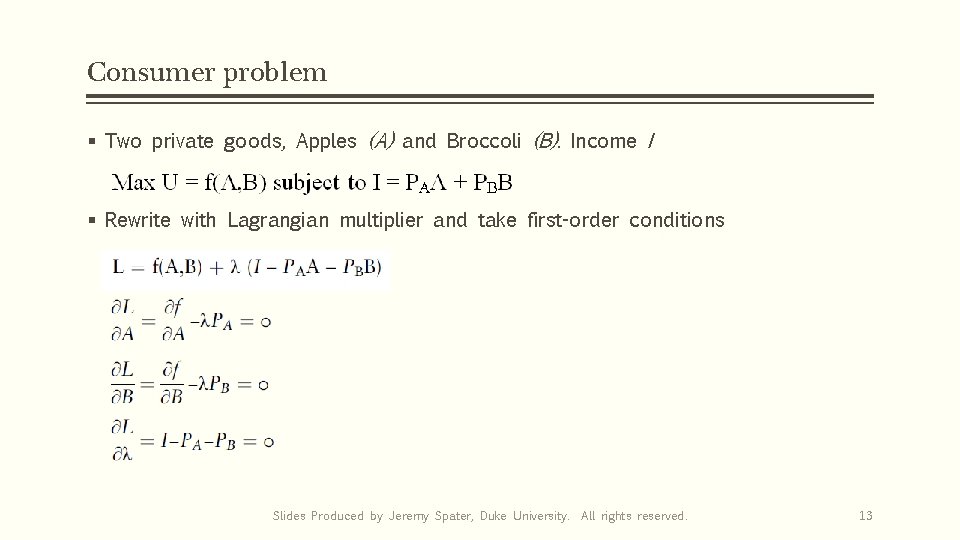

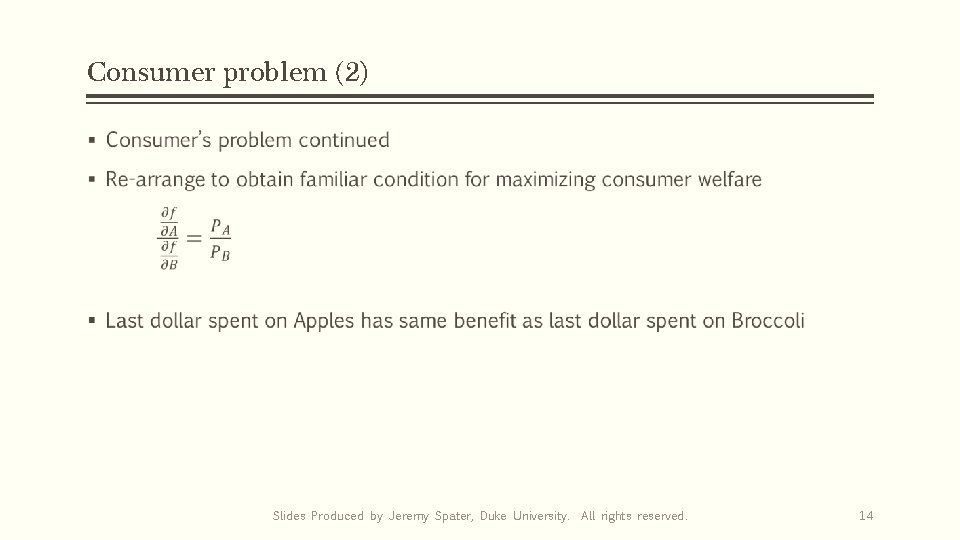

Consumer problem § Two private goods, Apples (A) and Broccoli (B). Income I § Rewrite with Lagrangian multiplier and take first-order conditions Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 13

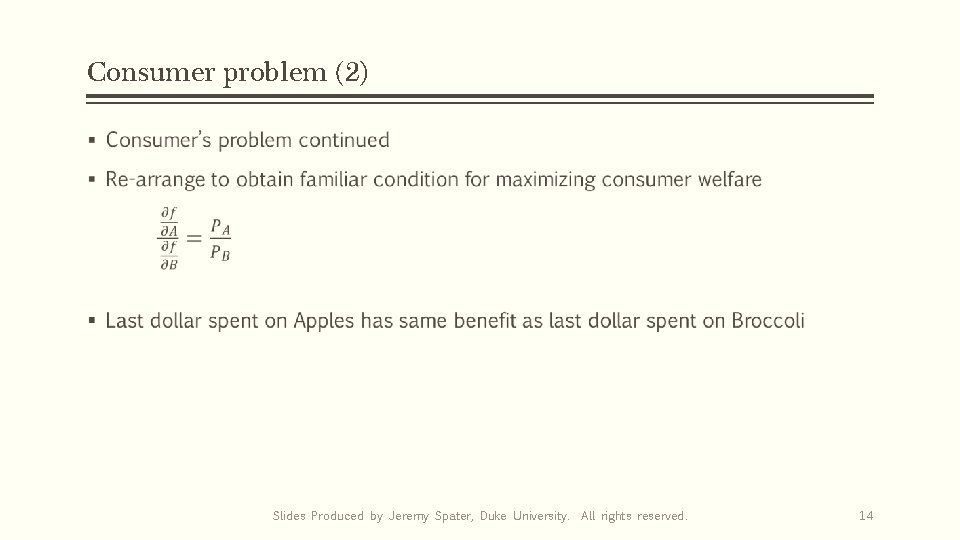

Consumer problem (2) § Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 14

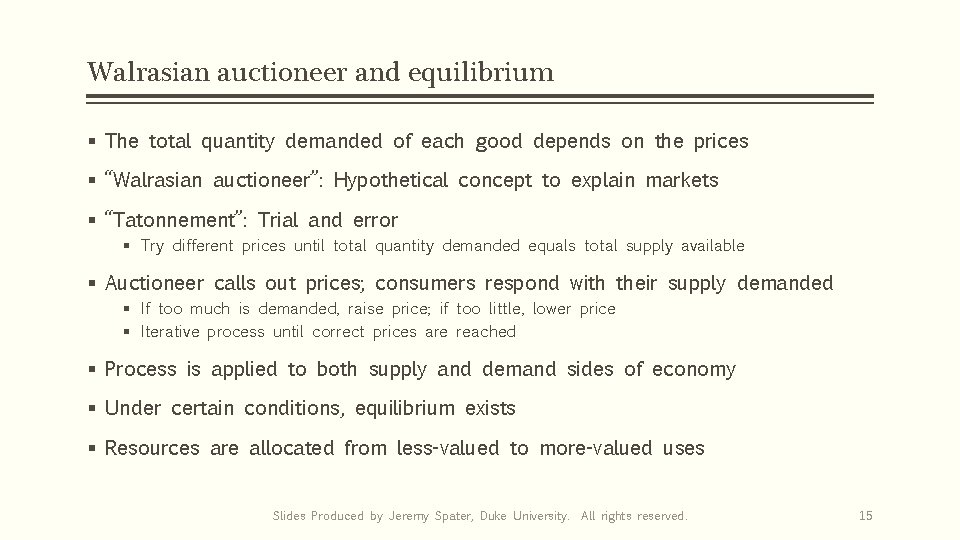

Walrasian auctioneer and equilibrium § The total quantity demanded of each good depends on the prices § “Walrasian auctioneer”: Hypothetical concept to explain markets § “Tatonnement”: Trial and error § Try different prices until total quantity demanded equals total supply available § Auctioneer calls out prices; consumers respond with their supply demanded § If too much is demanded, raise price; if too little, lower price § Iterative process until correct prices are reached § Process is applied to both supply and demand sides of economy § Under certain conditions, equilibrium exists § Resources are allocated from less-valued to more-valued uses Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 15

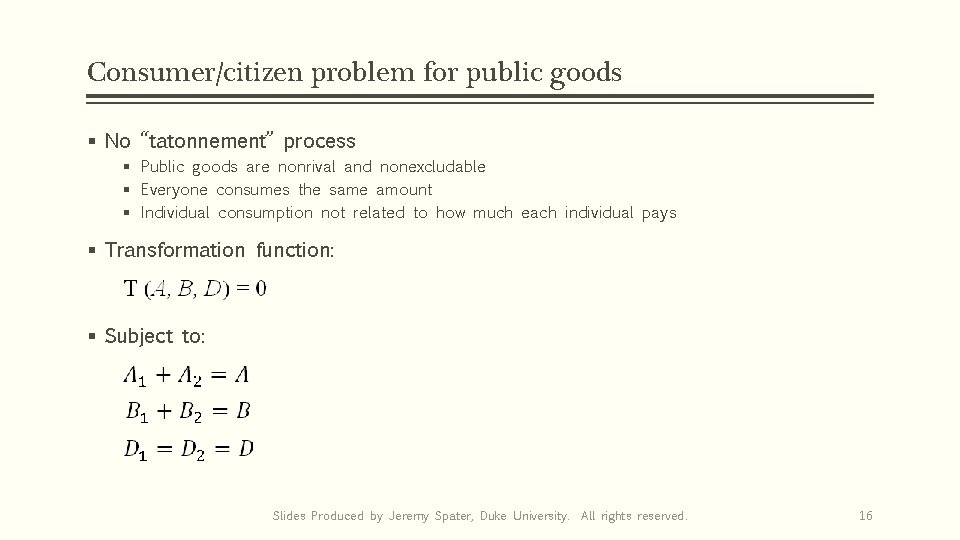

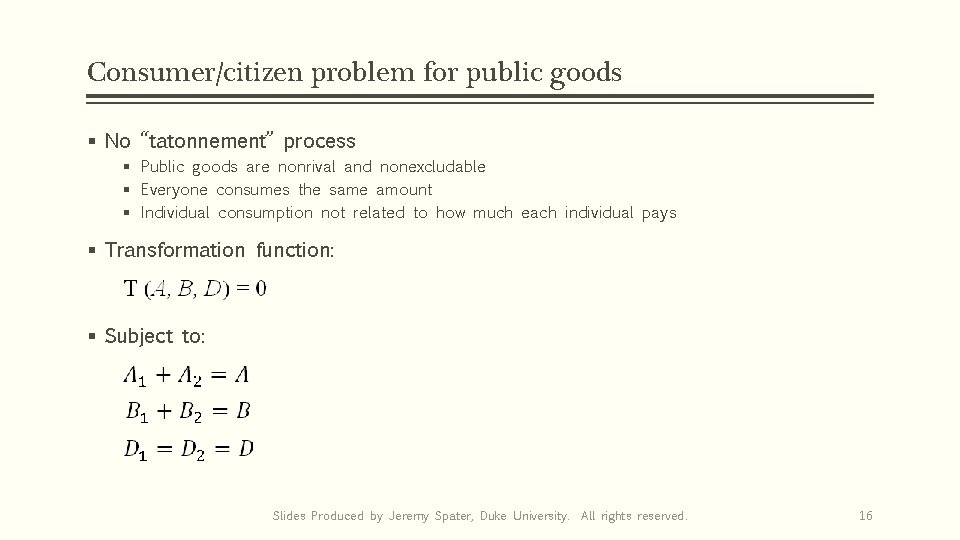

Consumer/citizen problem for public goods § No “tatonnement” process § Public goods are nonrival and nonexcludable § Everyone consumes the same amount § Individual consumption not related to how much each individual pays § Transformation function: § Subject to: Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 16

Consumer/citizen problem for public goods (2) § Social welfare function (ui is each citizen’s utility): § Objective function: § Write down Lagrangian: Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 17

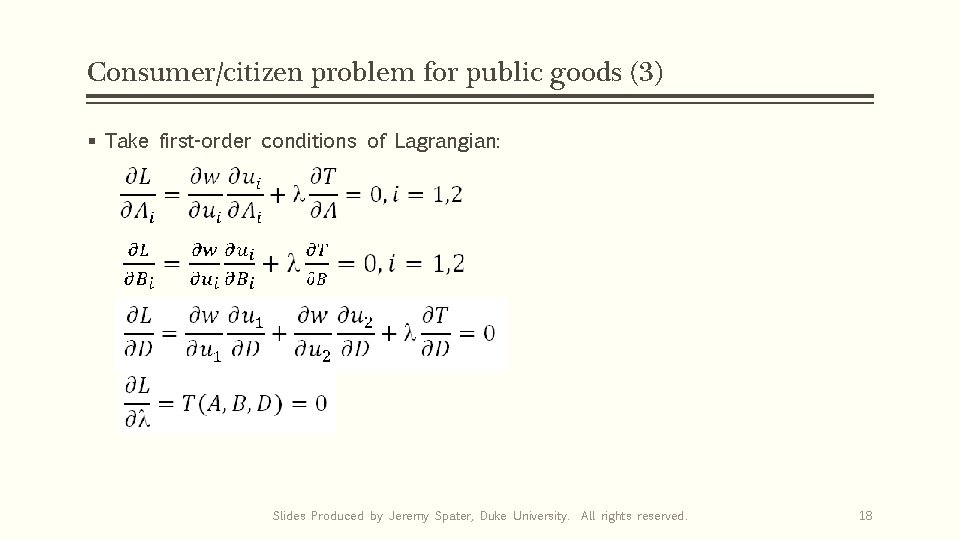

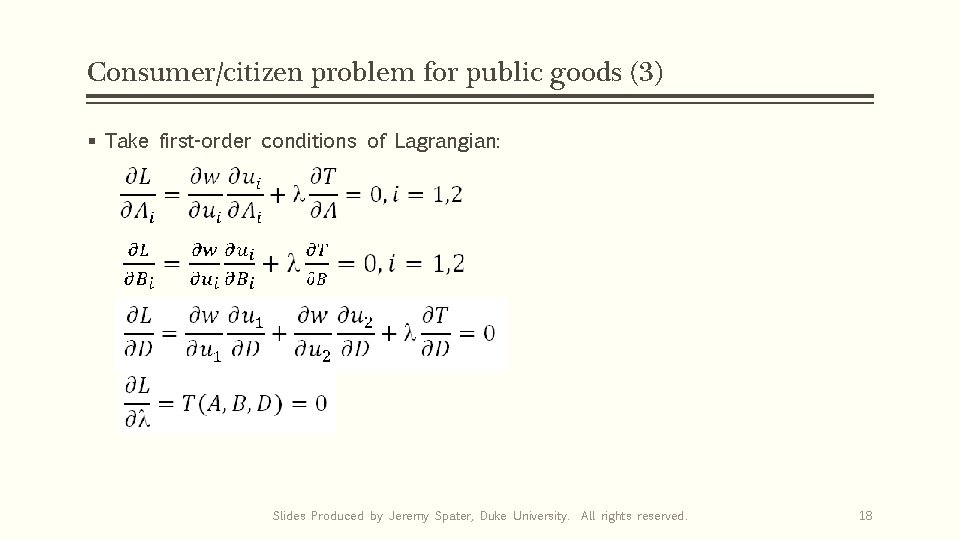

Consumer/citizen problem for public goods (3) § Take first-order conditions of Lagrangian: Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 18

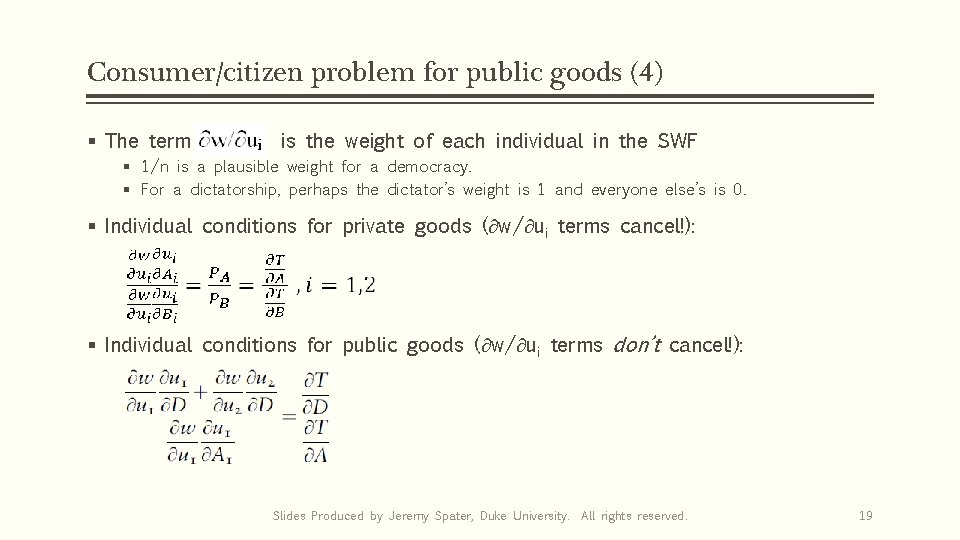

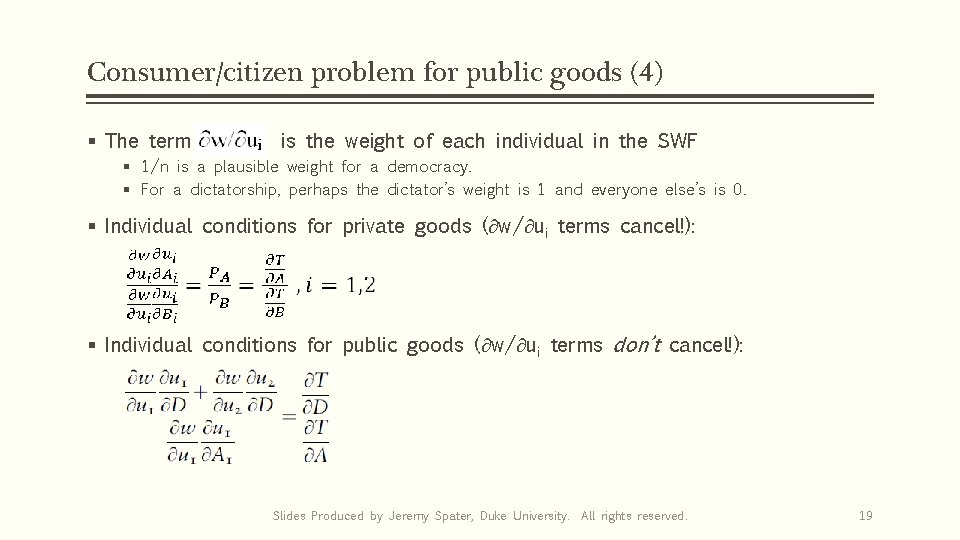

Consumer/citizen problem for public goods (4) § The term is the weight of each individual in the SWF § 1/n is a plausible weight for a democracy. § For a dictatorship, perhaps the dictator’s weight is 1 and everyone else’s is 0. § Individual conditions for private goods ( w/ ui terms cancel!): § Individual conditions for public goods ( w/ ui terms don’t cancel!): Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 19

Consumer/citizen problem for public goods (5) § Problems with representing public and private goods in same setting: § Weights of SWF with respect to individuals don’t cancel out! § Group constitution matters § Implied equilibrium levels depend on personal appraisals of the public good § No purely individual component; it depends on personal political beliefs § How do we determine who pays how much? Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 20

Lindahl equilibrium § Walrasian auctioneer process for public goods § Announce a level of public goods, and ask citizens what they would pay § If total payments > cost, raise level of public good (or vice versa) § Tatonnement process for public goods Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 21

Lindahl equilibrium (2) § Problems with Lindahl equilibrium: § Demand revelation: Everyone under-reports their own willingness to pay § Similar to free rider problem § End up with lower than optimal level of public good § Impossibility theorems (Arrow and others): § There is no solution for a robust and moral SWF that represents public preferences § Public goods preference revelation problem is impossible to solve § Failure of “induced” public sector preferences § Single utility function representing public and private preferences does not exist Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 22

Ways to represent public preferences § Use weak ordering directly § This avoids the representation problem entirely § Model collective choice preferences directly § Drop economists’ method of modeling “induced” preferences § Model collective choice rather than public goods § Deal directly with institutions and consequences of choosing in groups § Extension to multiple dimensions Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 23

Problem of aggregation § Core of social choice problem: § Aggregation of individual choices into legitimate and accepted consensus § Plott’s fundamental “equation” of politics: § Outcome can change when institutions change (with constant preferences) § Outcome can change when preferences change (with constant institutions) Slides Produced by Jeremy Spater, Duke University. All rights reserved. 24