CATR Programming Committee Land Acknowledgment As part of

- Slides: 19

CATR Programming Committee Land Acknowledgment As part of CATR 2018, Stó: lō scholar and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Arts, Dylan Robinson, will host a plenary discussion on performing land acknowledgments. In consulting with him on how we might engage in a respectful practice of acknowledgment as part of our conference opening, Dylan suggested that we include something prominently in the written/online program that comes from the organizing committee. In particular this would be an articulation that would move acknowledgement beyond standardization from the perspective of ourselves as a diverse group of theatre scholars and practitioners with very different positionalities. He encouraged us to seek to address the question: why is acknowledgement important to us?

Creating situational and relational practice of acknowledgement at our conference can be a way to query what this academic gathering will be offering to the land Indigenous peoples of this place. Taking time to consider these things, both before we arrive as we prepare our contributions and then also throughout the conference could be part of a decolonial practice that moves away from extractivist assumptions that the land, Indigenous peoples and other-than-human beings that inhabit it are irrelevant to the work that we do.

Each member of the programming was asked to craft a statement (max. 150 words) that responds to these prompts: • Where you are coming from – in relation to your positionality and the Indigenous peoples and territories where you currently live and work? • What does your presence on Haudenosaunee / Anishinaabe lands potentially bring? • Why is land acknowledgment important to you? • Include an image of your choice, e. g. from your home, or a visual metaphor that relates to your statement in some way… We also consulted Métis scholar Chelsea Vowel’s article “Beyond Territorial Acknowledgments” for thoughts on how (and why) to move beyond basic territorial acknowledgments. The following slides are the result of this process.

This is a photo my friend Cath took Jenn Stephenson: Why is land acknowledgment important to me? of the land the water at a moment of change and ambiguity. It reminds me that the water is the same water that was there from the beginning. It was, it is, and it will be. The past, present, and future of Indigenous people in Canada ought to be central to my understanding of Canadian culture. Statements of land acknowledgment offer a moment of pause to restate the centrality and impact of Indigenous experience, history, and culture. Indigenous culture is Canadian culture. Land acknowledgments make this visible.

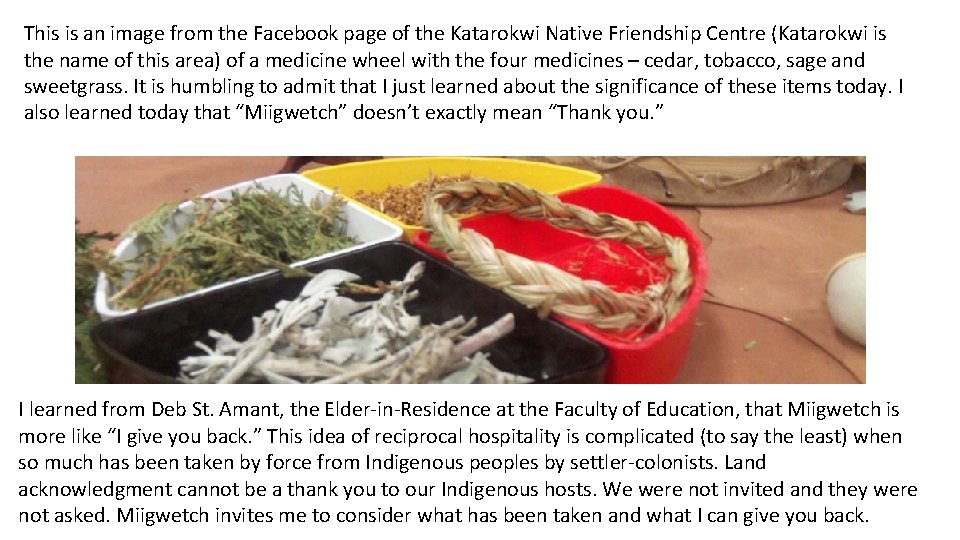

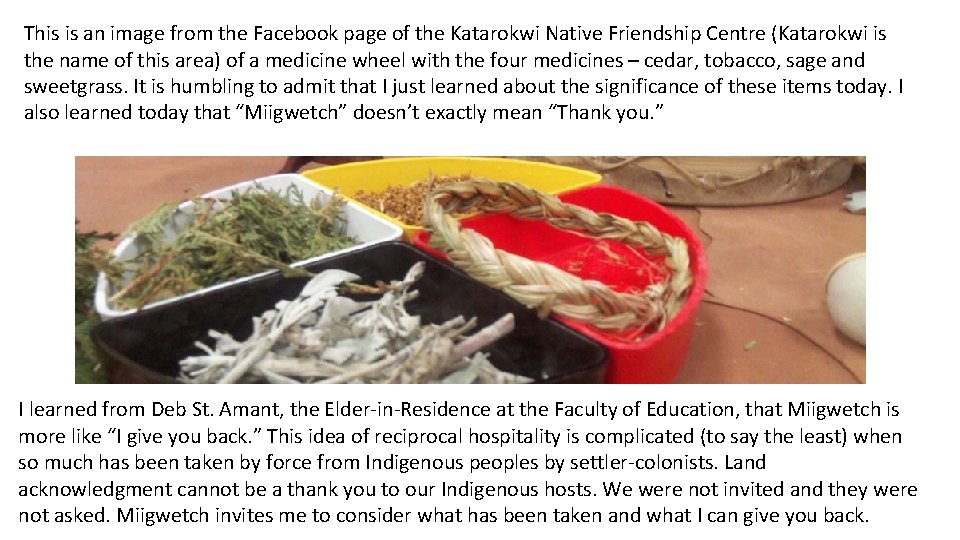

This is an image from the Facebook page of the Katarokwi Native Friendship Centre (Katarokwi is the name of this area) of a medicine wheel with the four medicines – cedar, tobacco, sage and sweetgrass. It is humbling to admit that I just learned about the significance of these items today. I also learned today that “Miigwetch” doesn’t exactly mean “Thank you. ” I learned from Deb St. Amant, the Elder-in-Residence at the Faculty of Education, that Miigwetch is more like “I give you back. ” This idea of reciprocal hospitality is complicated (to say the least) when so much has been taken by force from Indigenous peoples by settler-colonists. Land acknowledgment cannot be a thank you to our Indigenous hosts. We were not invited and they were not asked. Miigwetch invites me to consider what has been taken and what I can give you back.

Thoughts About Land Acknowledgements: Craig Walker I was born in Toronto to a mother who was an immigrant, and a father who was the child of immigrants. But the cultural touchstones of my upbringing were pretty much entirely Canadian, and on the few occasions I traveled to what my parents would have considered “the old country, ” my visit only served to underscore that I really have no sense of belonging to any place but Canada. 1 of 3

Naturally, it is not easy to reconcile that fact with my awareness that, from a certain perspective, I am no more than a late-arriving European settler, a colonist and an interloper in First Nations land. But, having no existential attachment to any other place, I conclude that my only choice is to form a greater sense of attachment to this one. For me, that means developing some awareness of the deeper history of this land intuiting how my predecessors have felt a sense of connection to it, particularly in the times prior to European contact. Walker 2 of 3

An important insight for me occurred many years ago when I visited the Museum of Anthropology at UBC and I realized how various Indigenous cultures located all across the country had, in the style of their artefacts, expressed a very specific sense of place. In Ontario, one sees it quite clearly, for example, in petroglyphs. There is a profundity there that I think defies translation or imitation, but it can be acknowledged. Though, personally, I never do so without an accompanying sense of loss. That is basically what the acknowledgement in Kingston that these are the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe (and perhaps earlier, the Wendat? ) means to me: it’s an acknowledgement of the importance of an existential connection to place and an acknowledgement that the level at which some people have experienced that connection represents an ideal that may be never fully available to me. Walker 3 of 3

Robin Whittaker: My house and my place of work are situated in Fredericton on land that is the traditional territory of the Wolastoqiyik / Maliseet whose ancestors along with the Mi’Kmaq / Mi’kmaw and Passamaquoddy / Peskotomuhkati Tribes / Nations signed Peace and Friendship Treaties with the British Crown in the 1700 s. As a guest on Haudenosaunee / Anishinaabe lands during CATR 2018, I hope to share knowledge with colleagues from across Canada and beyond. Land Acknowledgement encourages us to be mindful of those who have lived, and still live, here, and how these lands have been used. I have included as the requested image a photograph of me at Fort Henry at the age of 8. My parents took me to Kingston several summers in a row owing to my father’s great interest (scholarly and personal) in Canadian history. I am grateful for the opportunity to return now as a scholar of Canadian theatre and performance history. Best, Robin

Selena Couture: I am an 11 th generation descendent of settlers who came to the lands now known as Canada in 1640. For 132 years my family has lived on lands accessed through treaty – specifically the Peace and Friendship Treaties, Upper Canada Treaties, and Treaty 2 and, most recently, Treaty 6 / Métis Territory as I started work in Amiskwacîwâskahikan. 1 of 2

During CATR at Ka'tarohkwi I aim to share my understandings and to learn from Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples what it means to be a respectful visitor in their lands, as I have been learning from Cree peoples in Treaty 6 recently through two sculptures shown on the next 2 slides. Couture 2 of 2

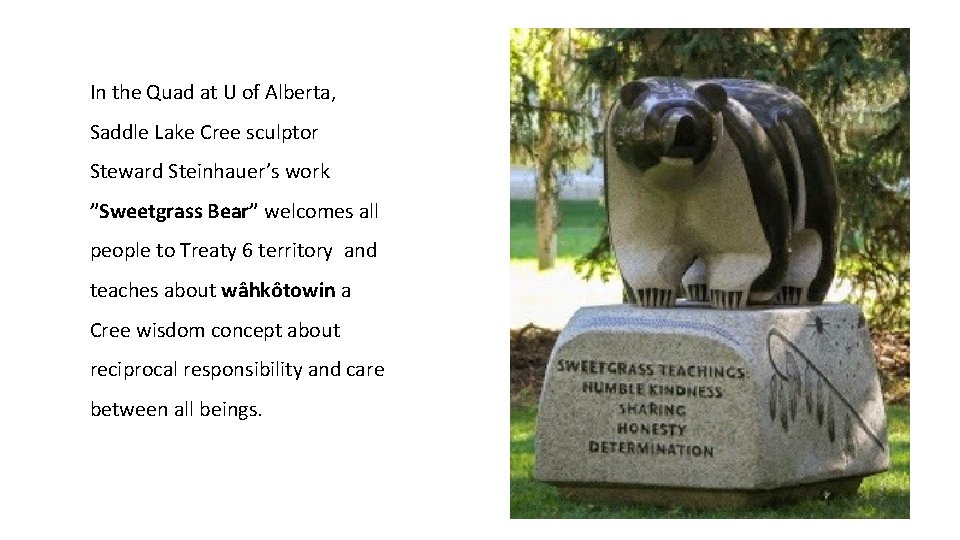

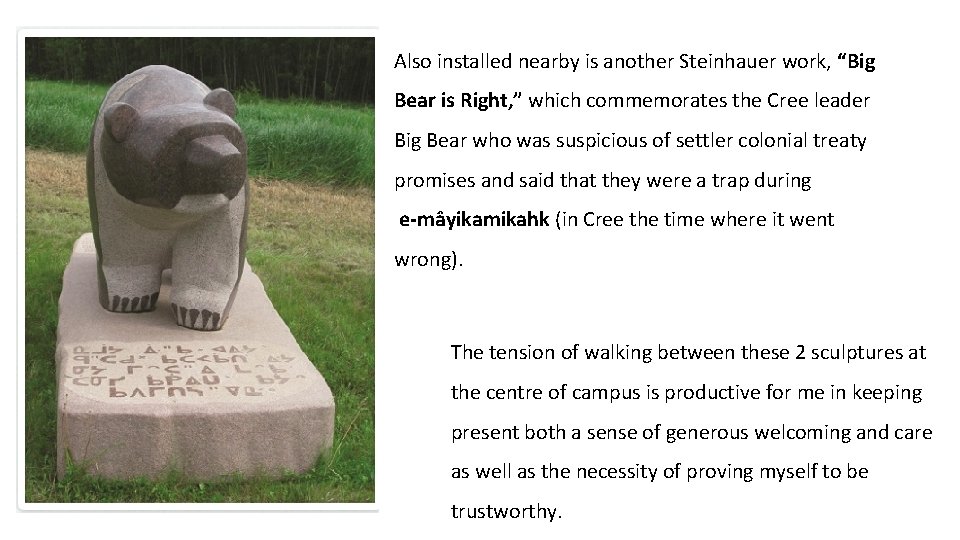

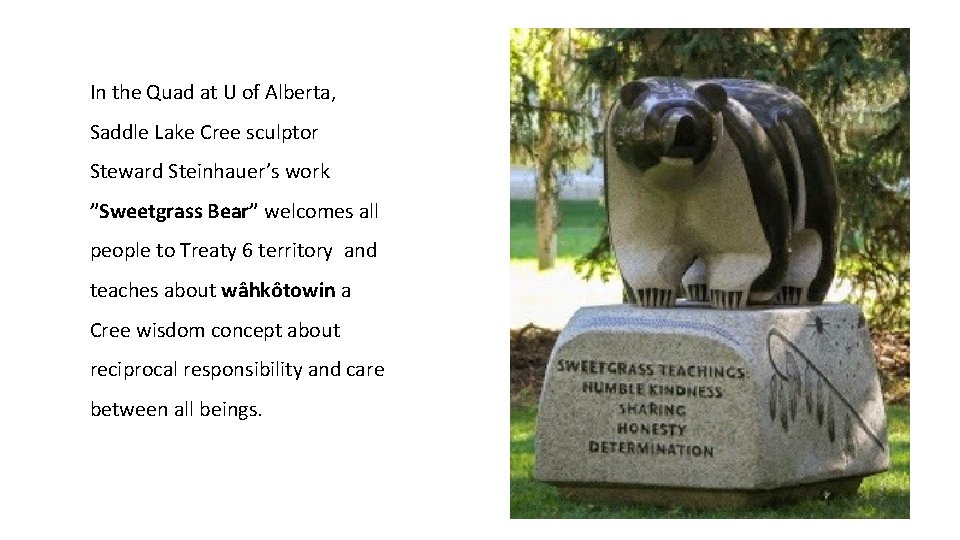

In the Quad at U of Alberta, Saddle Lake Cree sculptor Steward Steinhauer’s work ”Sweetgrass Bear” welcomes all people to Treaty 6 territory and teaches about wâhkôtowin a Cree wisdom concept about reciprocal responsibility and care between all beings.

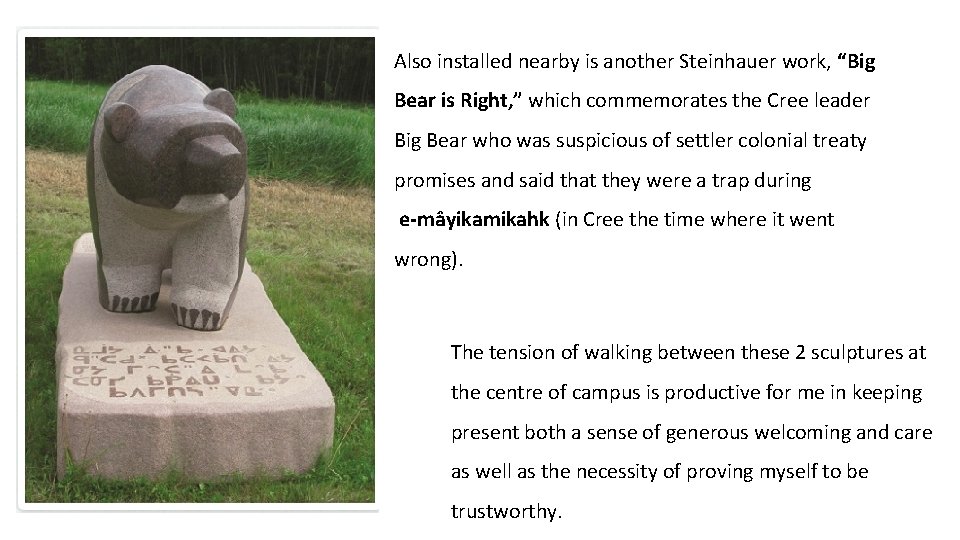

Also installed nearby is another Steinhauer work, “Big Bear is Right, ” which commemorates the Cree leader Big Bear who was suspicious of settler colonial treaty promises and said that they were a trap during e-mâyikamikahk (in Cree the time where it went wrong). The tension of walking between these 2 sculptures at the centre of campus is productive for me in keeping present both a sense of generous welcoming and care as well as the necessity of proving myself to be trustworthy.

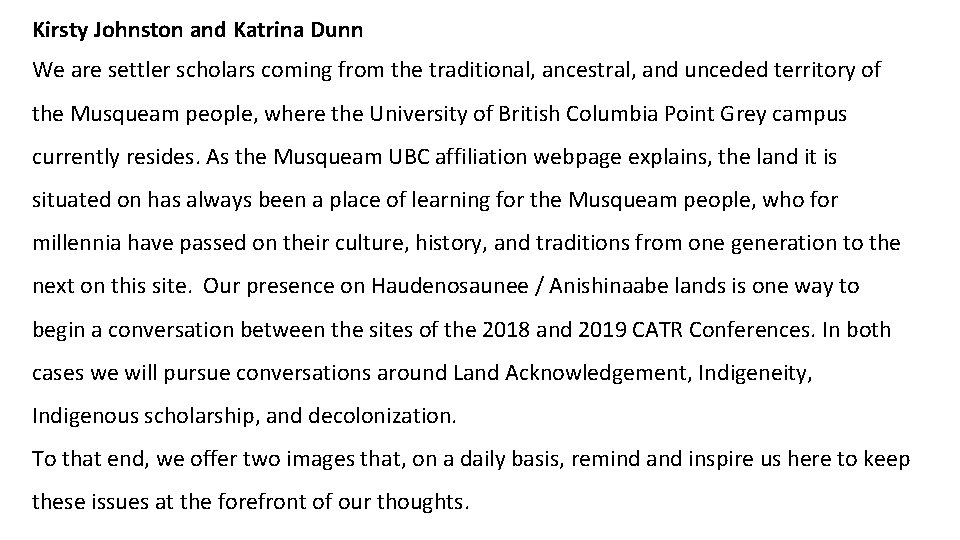

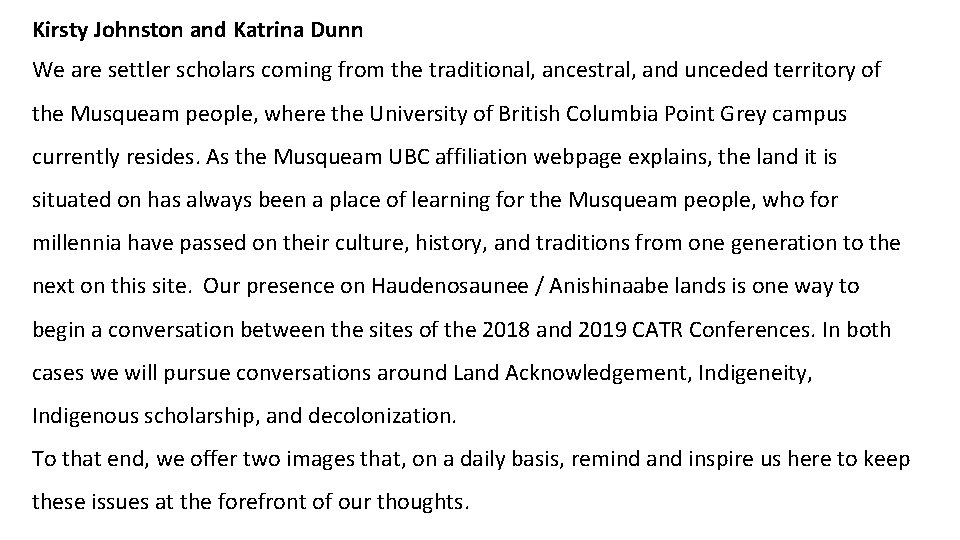

Kirsty Johnston and Katrina Dunn We are settler scholars coming from the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people, where the University of British Columbia Point Grey campus currently resides. As the Musqueam UBC affiliation webpage explains, the land it is situated on has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam people, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history, and traditions from one generation to the next on this site. Our presence on Haudenosaunee / Anishinaabe lands is one way to begin a conversation between the sites of the 2018 and 2019 CATR Conferences. In both cases we will pursue conversations around Land Acknowledgement, Indigeneity, Indigenous scholarship, and decolonization. To that end, we offer two images that, on a daily basis, remind and inspire us here to keep these issues at the forefront of our thoughts.

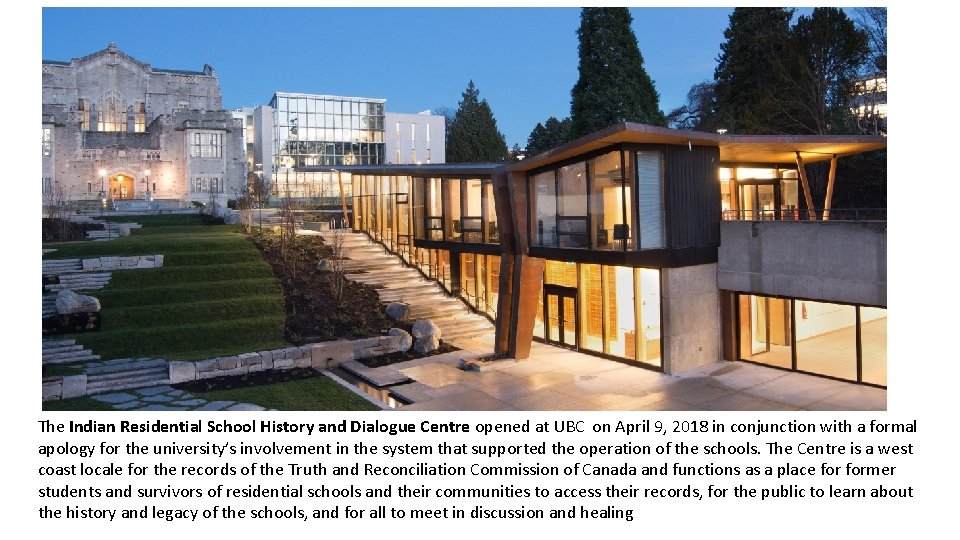

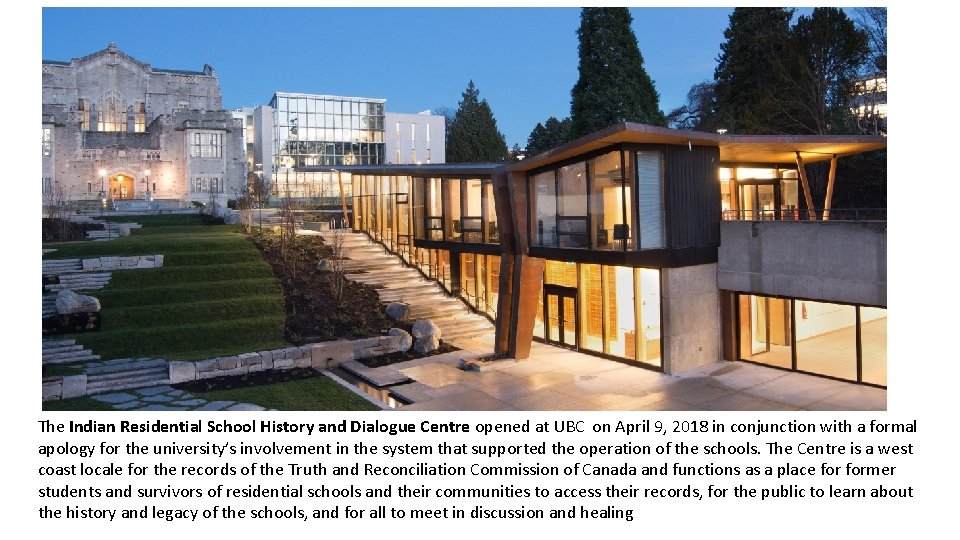

The Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre opened at UBC on April 9, 2018 in conjunction with a formal apology for the university’s involvement in the system that supported the operation of the schools. The Centre is a west coast locale for the records of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and functions as a place former students and survivors of residential schools and their communities to access their records, for the public to learn about the history and legacy of the schools, and for all to meet in discussion and healing

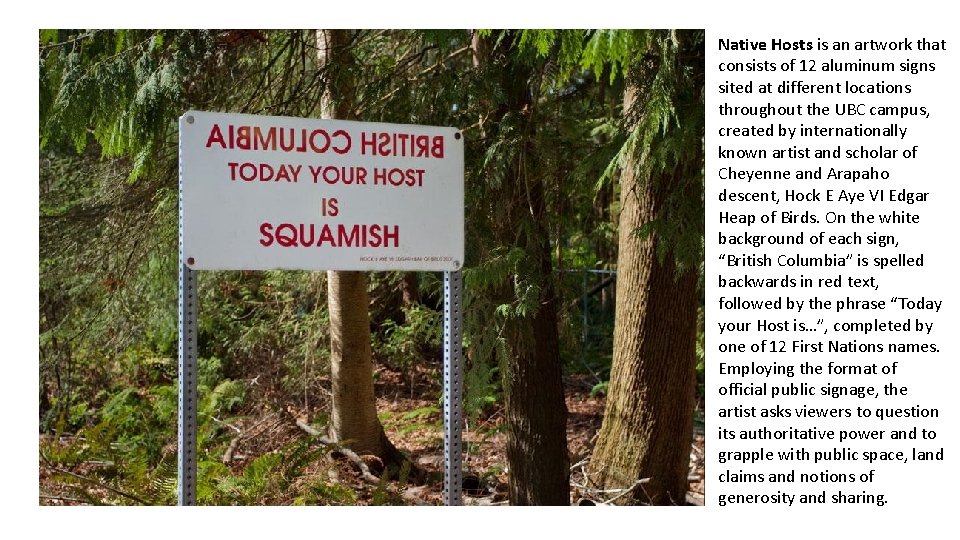

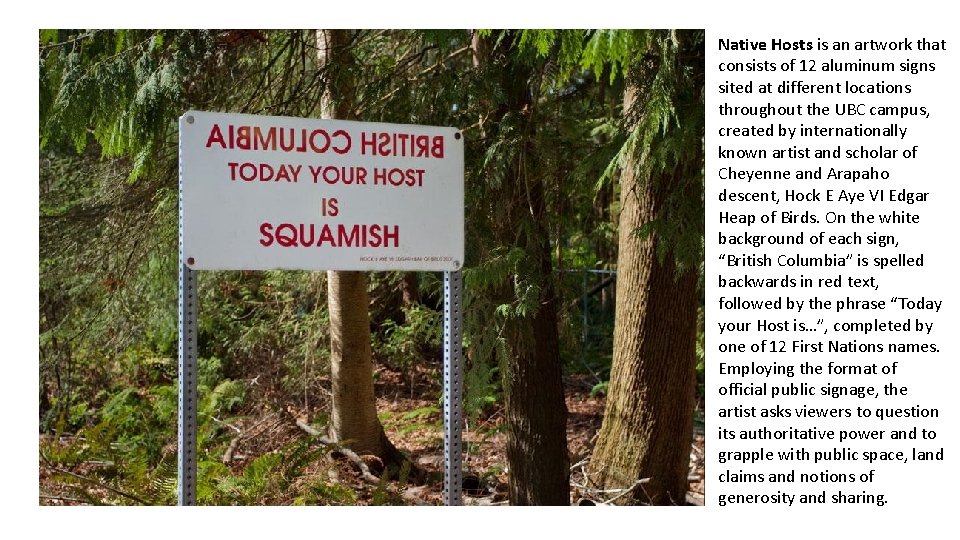

Native Hosts is an artwork that consists of 12 aluminum signs sited at different locations throughout the UBC campus, created by internationally known artist and scholar of Cheyenne and Arapaho descent, Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds. On the white background of each sign, “British Columbia” is spelled backwards in red text, followed by the phrase “Today your Host is…”, completed by one of 12 First Nations names. Employing the format of official public signage, the artist asks viewers to question its authoritative power and to grapple with public space, land claims and notions of generosity and sharing.