The Soviet Union emerged from the Second World

![1937 1941 1953 [thousands] In prisons 545 488 276 In camps 821 1501 1728 1937 1941 1953 [thousands] In prisons 545 488 276 In camps 821 1501 1728](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/26f34559aeac9f040302ecbeb0b23dc7/image-21.jpg)

- Slides: 52

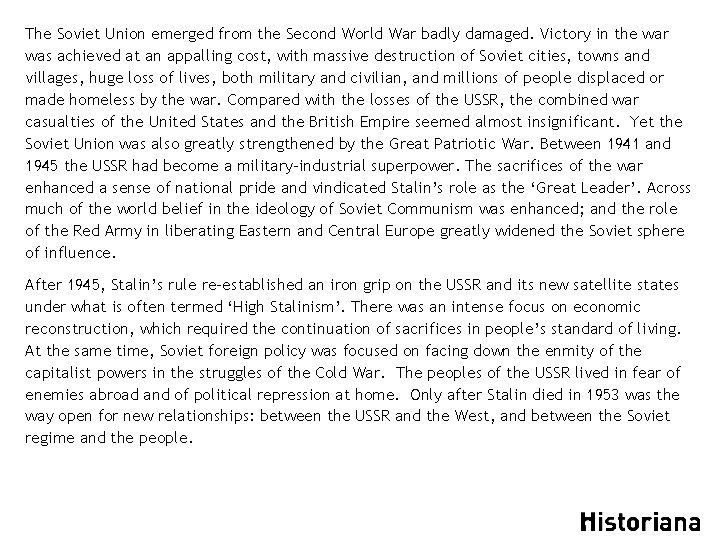

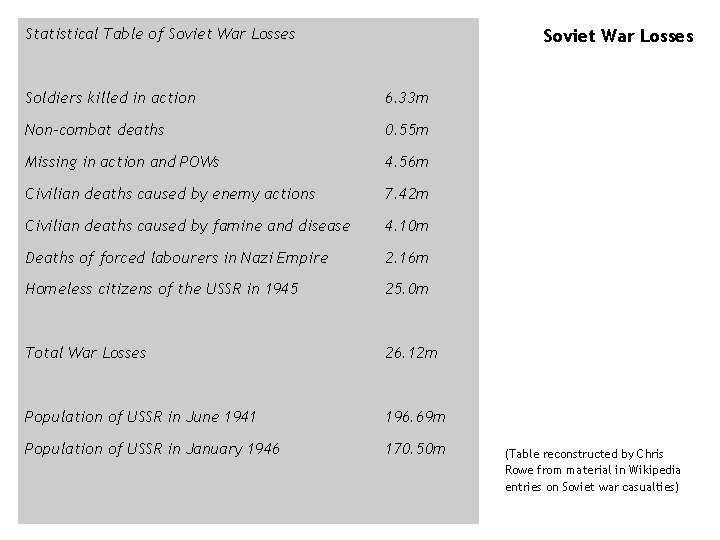

The Soviet Union emerged from the Second World War badly damaged. Victory in the war was achieved at an appalling cost, with massive destruction of Soviet cities, towns and villages, huge loss of lives, both military and civilian, and millions of people displaced or made homeless by the war. Compared with the losses of the USSR, the combined war casualties of the United States and the British Empire seemed almost insignificant. Yet the Soviet Union was also greatly strengthened by the Great Patriotic War. Between 1941 and 1945 the USSR had become a military-industrial superpower. The sacrifices of the war enhanced a sense of national pride and vindicated Stalin’s role as the ‘Great Leader’. Across much of the world belief in the ideology of Soviet Communism was enhanced; and the role of the Red Army in liberating Eastern and Central Europe greatly widened the Soviet sphere of influence. After 1945, Stalin’s rule re-established an iron grip on the USSR and its new satellite states under what is often termed ‘High Stalinism’. There was an intense focus on economic reconstruction, which required the continuation of sacrifices in people’s standard of living. At the same time, Soviet foreign policy was focused on facing down the enmity of the capitalist powers in the struggles of the Cold War. The peoples of the USSR lived in fear of enemies abroad and of political repression at home. Only after Stalin died in 1953 was the way open for new relationships: between the USSR and the West, and between the Soviet regime and the people.

The price of victory: Post-war reconstruction The USSR was greatly damaged by the immense national effort that had been required to win the war. Its people had been driven to endure great sacrifices and hardship. In 1945, many hoped for a period of relaxation and reward. This did not happen. The iron grip of the command economy remained; new sacrifices were demanded to push through post-war reconstruction, and to face down new threats from foreign enemies in the developing Cold War. Many parts of the USSR experienced a terrible famine in 1946 -47. Military spending was still given high priority. Living standards continued to be far lower than in the West, and consumer goods remained scarce. Even so, there was a significant recovery under the fourth Five Year Plan (1946 -50), especially in heavy industry. By 1953, the USSR was unmistakably a military-industrial superpower.

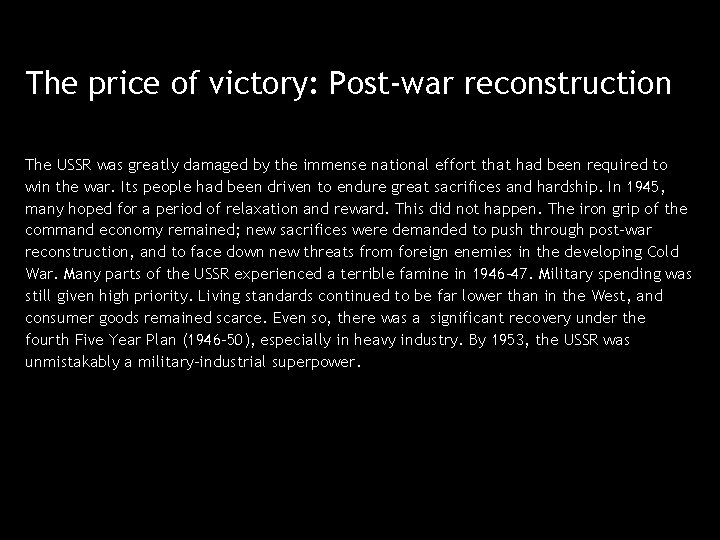

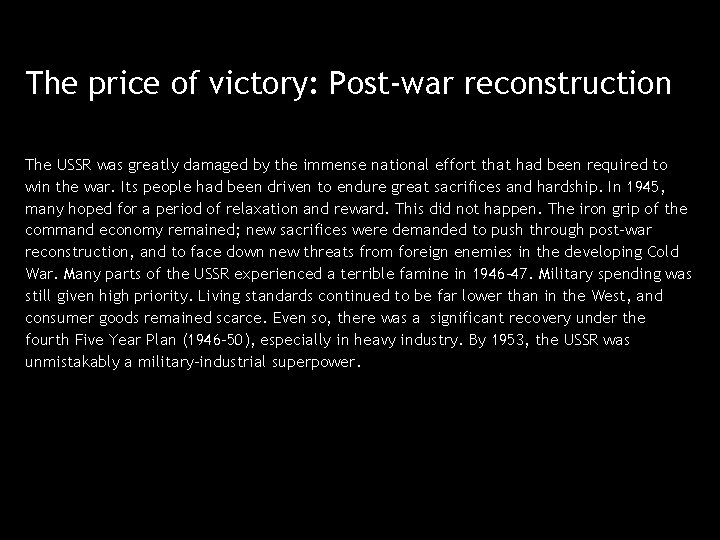

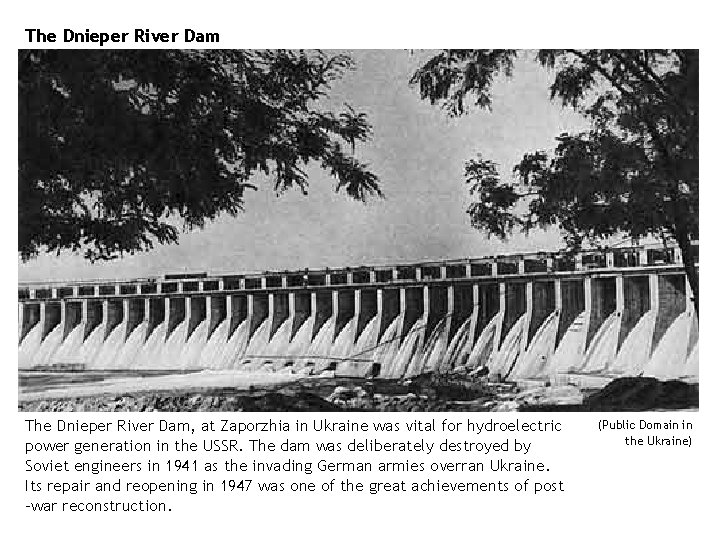

The battle of Stalingrad The great battle at Stalingrad in 1942 -43 left almost the entire city in ruins. (Public Domain in Russia) The war inflicted massive destruction upon Soviet Russia. This was partly the collateral damage of huge and costly battles, as armies advanced and retreated across European Russia and Ukraine. However, it also resulted from deliberate ‘scorched earth tactics’ designed to prevent valuable factories and equipment from falling into enemy hands.

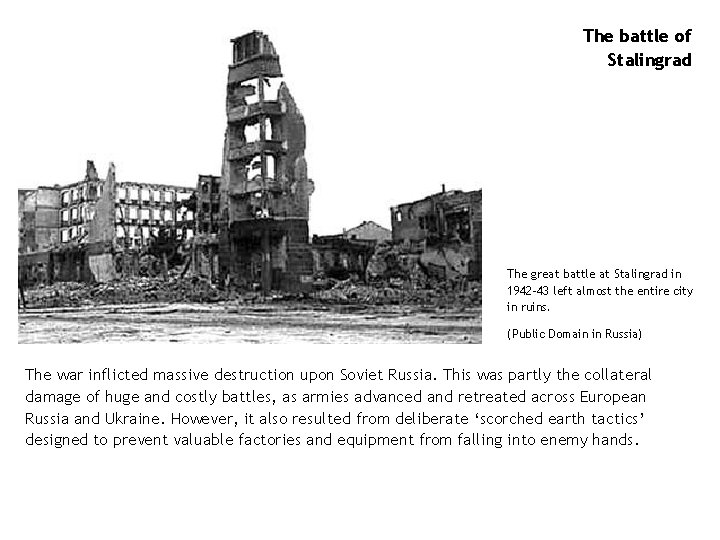

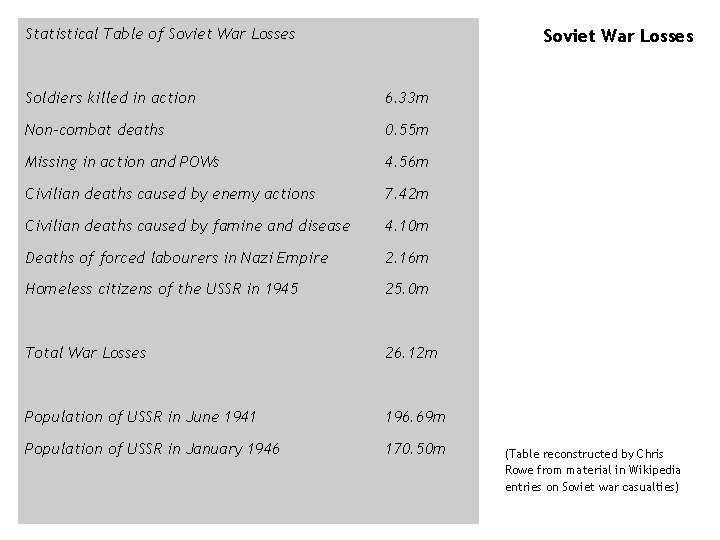

Statistical Table of Soviet War Losses Soldiers killed in action 6. 33 m Non-combat deaths 0. 55 m Missing in action and POWs 4. 56 m Civilian deaths caused by enemy actions 7. 42 m Civilian deaths caused by famine and disease 4. 10 m Deaths of forced labourers in Nazi Empire 2. 16 m Homeless citizens of the USSR in 1945 25. 0 m Total War Losses 26. 12 m Population of USSR in June 1941 196. 69 m Population of USSR in January 1946 170. 50 m (Table reconstructed by Chris Rowe from material in Wikipedia entries on Soviet war casualties)

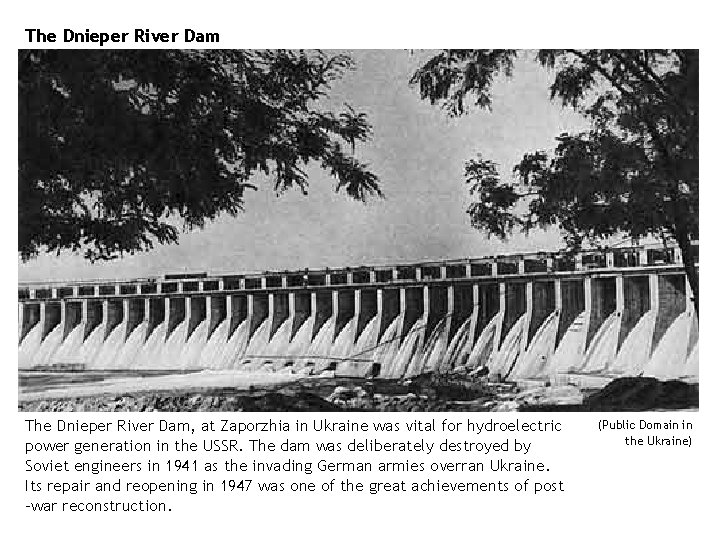

The Dnieper River Dam, at Zaporzhia in Ukraine was vital for hydroelectric power generation in the USSR. The dam was deliberately destroyed by Soviet engineers in 1941 as the invading German armies overran Ukraine. Its repair and reopening in 1947 was one of the great achievements of post -war reconstruction. (Public Domain in the Ukraine)

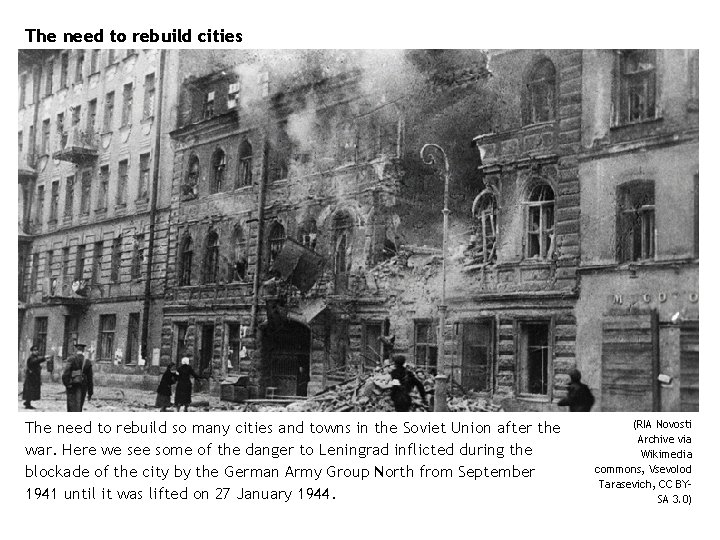

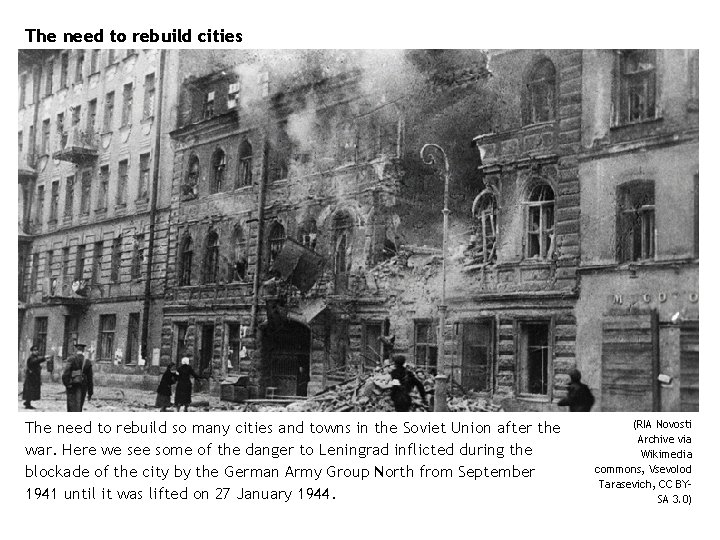

The need to rebuild cities The need to rebuild so many cities and towns in the Soviet Union after the war. Here we see some of the danger to Leningrad inflicted during the blockade of the city by the German Army Group North from September 1941 until it was lifted on 27 January 1944. (RIA Novosti Archive via Wikimedia commons, Vsevolod Tarasevich, CC BYSA 3. 0)

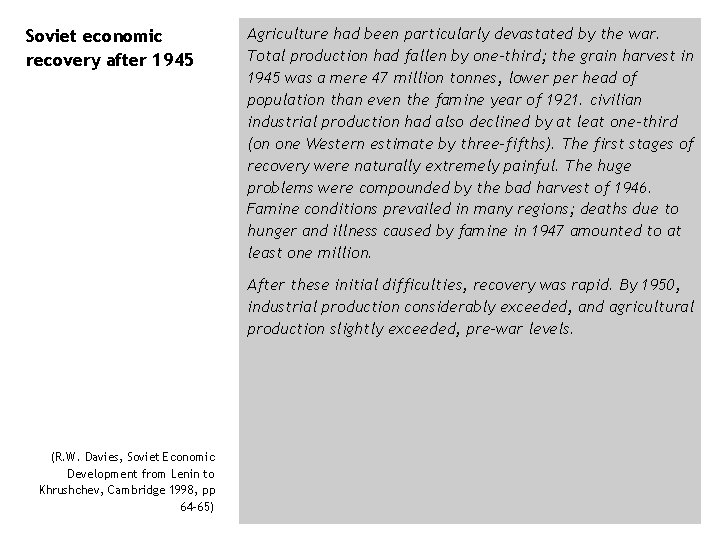

Soviet economic recovery after 1945 Agriculture had been particularly devastated by the war. Total production had fallen by one-third; the grain harvest in 1945 was a mere 47 million tonnes, lower per head of population than even the famine year of 1921. civilian industrial production had also declined by at leat one-third (on one Western estimate by three-fifths). The first stages of recovery were naturally extremely painful. The huge problems were compounded by the bad harvest of 1946. Famine conditions prevailed in many regions; deaths due to hunger and illness caused by famine in 1947 amounted to at least one million. After these initial difficulties, recovery was rapid. By 1950, industrial production considerably exceeded, and agricultural production slightly exceeded, pre-war levels. (R. W. Davies, Soviet Economic Development from Lenin to Khrushchev, Cambridge 1998, pp 64 -65)

The rise of the Soviet Empire At the end of Soviet Russia’s ‘Great Patriotic War’ the Red Army controlled much of Eastern and Central Europe. This military occupation became the basis of Soviet political domination in the post-war years. There were extensive territorial changes and shifts of population. The Baltic States and parts of eastern Poland were incorporated into the USSR. Between 1945 and 1948, ‘friendly governments’ were installed in such ‘satellite states’ as Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. Until 1948, Yugoslavia was also seen as a Soviet satellite, until Tito broke with Stalin and Yugoslavia became ‘non-aligned’ (neither allied with the USSR or the west). This extension of Soviet influence was not the result of agreed peace treaties. It took place in the formative stages of the emerging Cold War and the division of Europe between East and West. At the time and ever since, historians have disagreed as to how far the actions of the Soviet Union at this time was driven by Communist ideology and Stalin’s deliberate expansionist aims, or by the provocations of Western, especially American, disregard for the legitimate interests of the Soviet Union. By 1949, the USSR was established as a militaryindustrial superpower. The Soviet Bloc now faced the Western Alliance in a bipolar world.

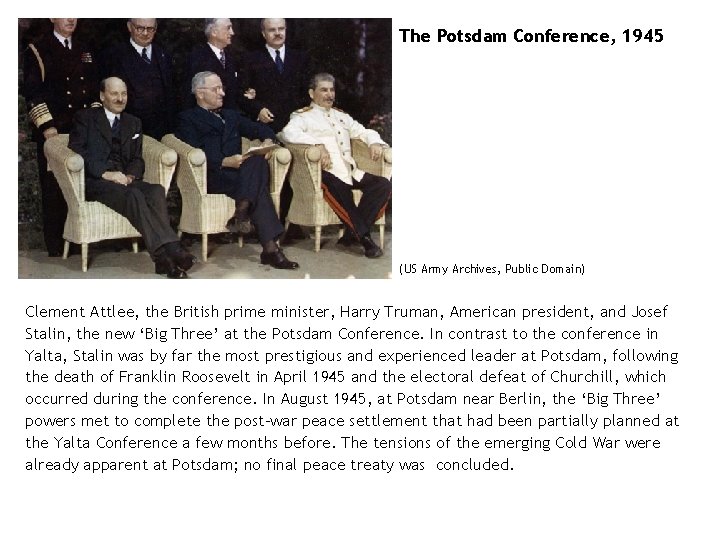

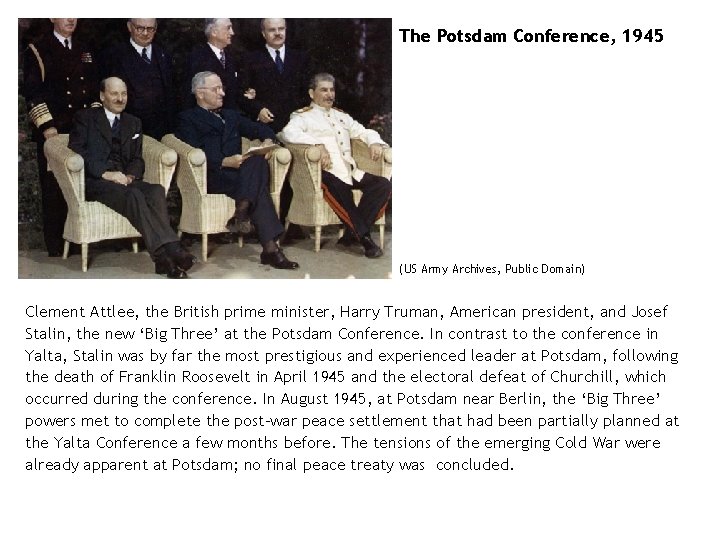

The Potsdam Conference, 1945 (US Army Archives, Public Domain) Clement Attlee, the British prime minister, Harry Truman, American president, and Josef Stalin, the new ‘Big Three’ at the Potsdam Conference. In contrast to the conference in Yalta, Stalin was by far the most prestigious and experienced leader at Potsdam, following the death of Franklin Roosevelt in April 1945 and the electoral defeat of Churchill, which occurred during the conference. In August 1945, at Potsdam near Berlin, the ‘Big Three’ powers met to complete the post-war peace settlement that had been partially planned at the Yalta Conference a few months before. The tensions of the emerging Cold War were already apparent at Potsdam; no final peace treaty was concluded.

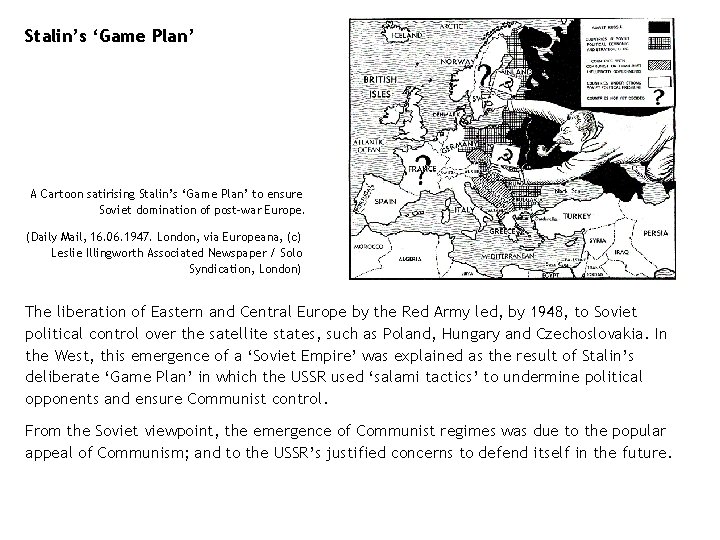

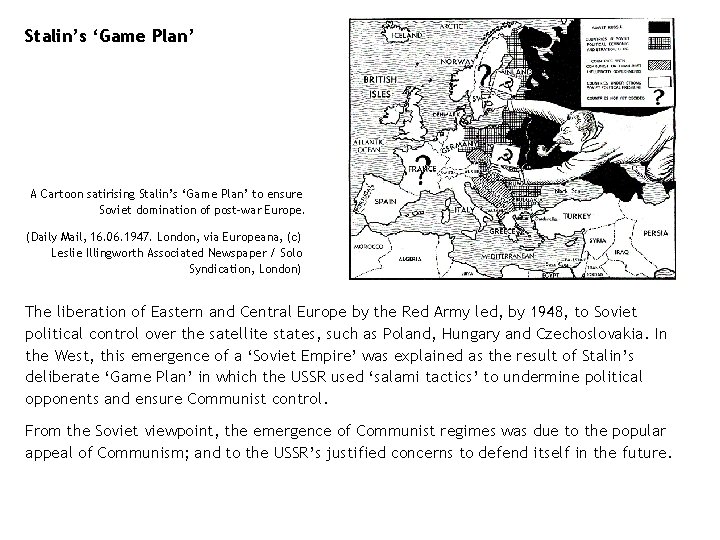

Stalin’s ‘Game Plan’ A Cartoon satirising Stalin’s ‘Game Plan’ to ensure Soviet domination of post-war Europe. (Daily Mail, 16. 06. 1947. London, via Europeana, (c) Leslie Illingworth Associated Newspaper / Solo Syndication, London) The liberation of Eastern and Central Europe by the Red Army led, by 1948, to Soviet political control over the satellite states, such as Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. In the West, this emergence of a ‘Soviet Empire’ was explained as the result of Stalin’s deliberate ‘Game Plan’ in which the USSR used ‘salami tactics’ to undermine political opponents and ensure Communist control. From the Soviet viewpoint, the emergence of Communist regimes was due to the popular appeal of Communism; and to the USSR’s justified concerns to defend itself in the future.

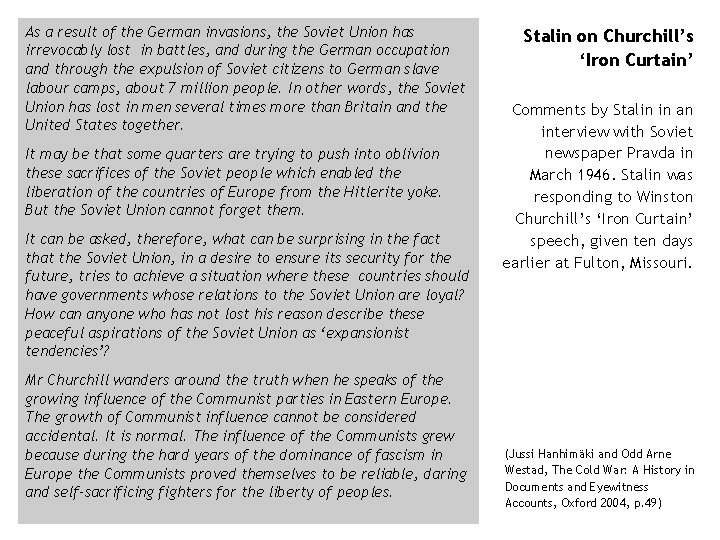

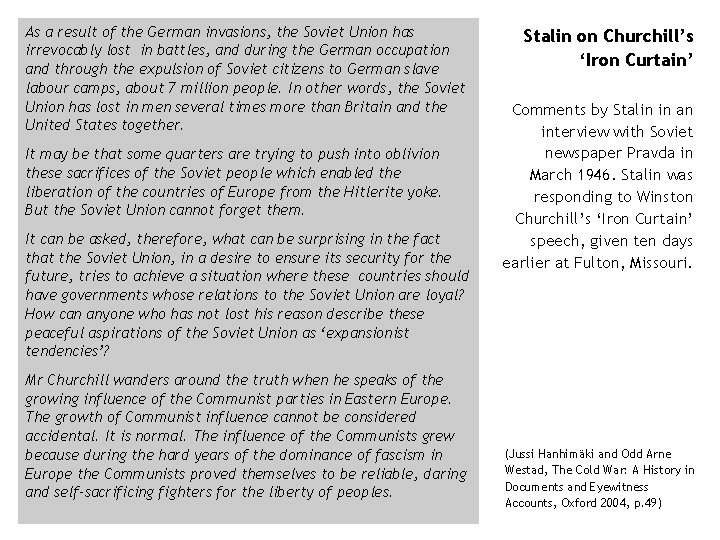

As a result of the German invasions, the Soviet Union has irrevocably lost in battles, and during the German occupation and through the expulsion of Soviet citizens to German slave labour camps, about 7 million people. In other words, the Soviet Union has lost in men several times more than Britain and the United States together. It may be that some quarters are trying to push into oblivion these sacrifices of the Soviet people which enabled the liberation of the countries of Europe from the Hitlerite yoke. But the Soviet Union cannot forget them. It can be asked, therefore, what can be surprising in the fact that the Soviet Union, in a desire to ensure its security for the future, tries to achieve a situation where these countries should have governments whose relations to the Soviet Union are loyal? How can anyone who has not lost his reason describe these peaceful aspirations of the Soviet Union as ‘expansionist tendencies’? Mr Churchill wanders around the truth when he speaks of the growing influence of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe. The growth of Communist influence cannot be considered accidental. It is normal. The influence of the Communists grew because during the hard years of the dominance of fascism in Europe the Communists proved themselves to be reliable, daring and self-sacrificing fighters for the liberty of peoples. Stalin on Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ Comments by Stalin in an interview with Soviet newspaper Pravda in March 1946. Stalin was responding to Winston Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech, given ten days earlier at Fulton, Missouri. (Jussi Hanhimäki and Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, Oxford 2004, p. 49)

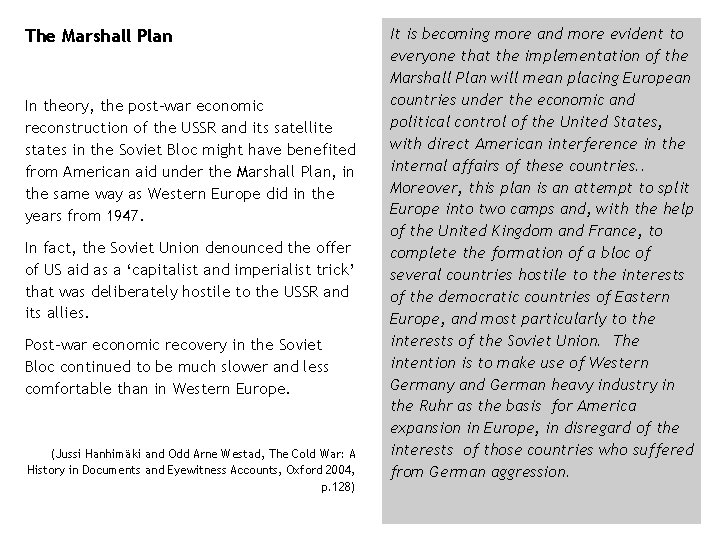

The Marshall Plan In theory, the post-war economic reconstruction of the USSR and its satellite states in the Soviet Bloc might have benefited from American aid under the Marshall Plan, in the same way as Western Europe did in the years from 1947. In fact, the Soviet Union denounced the offer of US aid as a ‘capitalist and imperialist trick’ that was deliberately hostile to the USSR and its allies. Post-war economic recovery in the Soviet Bloc continued to be much slower and less comfortable than in Western Europe. (Jussi Hanhimäki and Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A History in Documents and Eyewitness Accounts, Oxford 2004, p. 128) It is becoming more and more evident to everyone that the implementation of the Marshall Plan will mean placing European countries under the economic and political control of the United States, with direct American interference in the internal affairs of these countries. . Moreover, this plan is an attempt to split Europe into two camps and, with the help of the United Kingdom and France, to complete the formation of a bloc of several countries hostile to the interests of the democratic countries of Eastern Europe, and most particularly to the interests of the Soviet Union. The intention is to make use of Western Germany and German heavy industry in the Ruhr as the basis for America expansion in Europe, in disregard of the interests of those countries who suffered from German aggression.

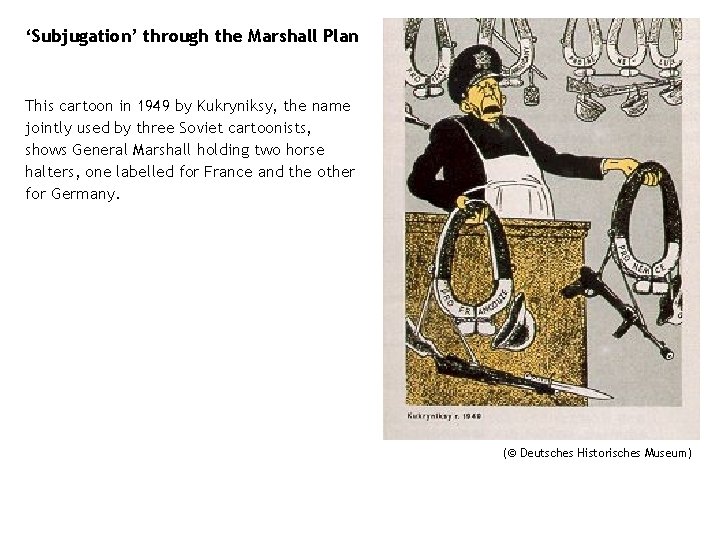

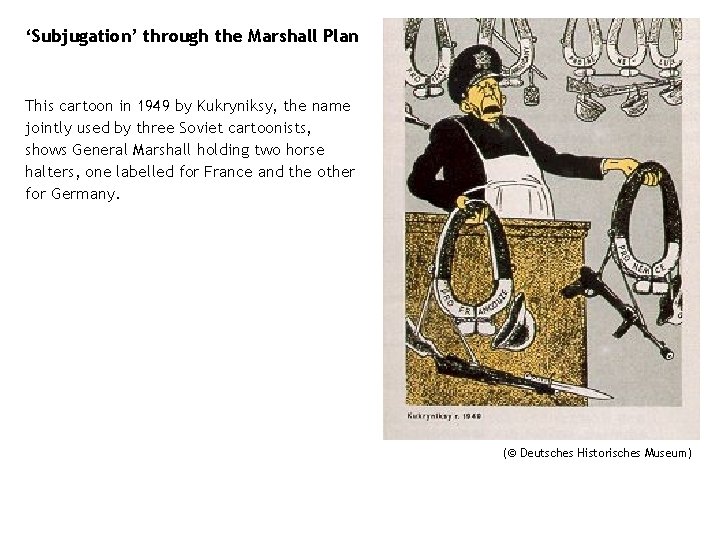

‘Subjugation’ through the Marshall Plan This cartoon in 1949 by Kukryniksy, the name jointly used by three Soviet cartoonists, shows General Marshall holding two horse halters, one labelled for France and the other for Germany. (© Deutsches Historisches Museum)

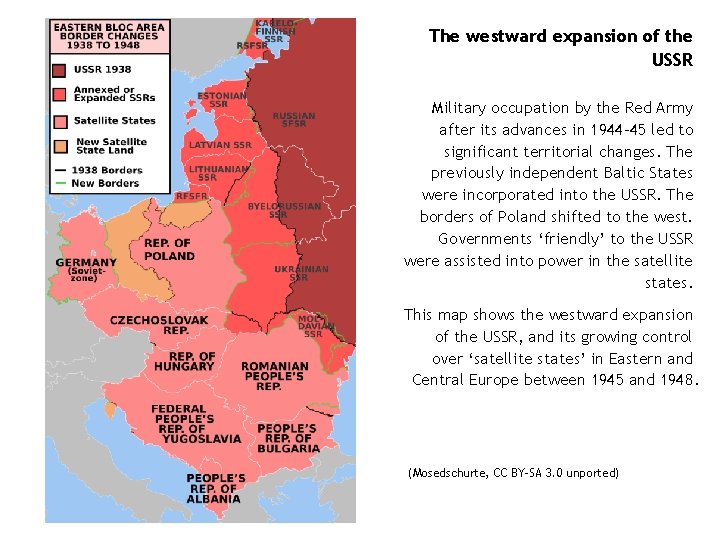

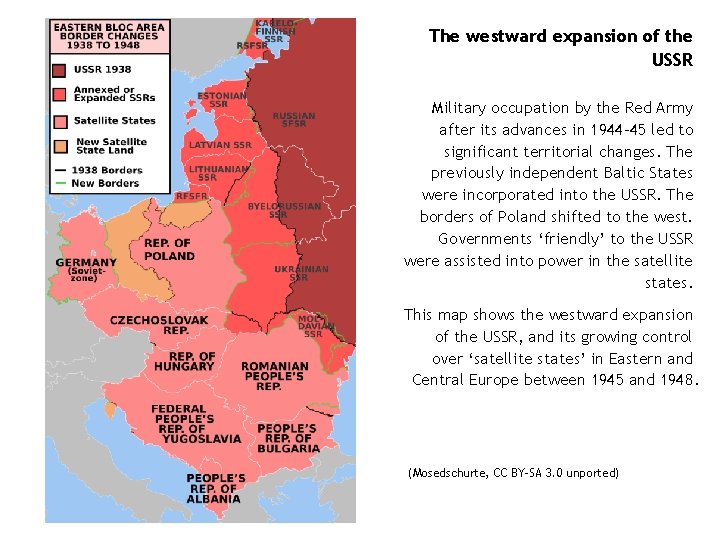

The westward expansion of the USSR Military occupation by the Red Army after its advances in 1944 -45 led to significant territorial changes. The previously independent Baltic States were incorporated into the USSR. The borders of Poland shifted to the west. Governments ‘friendly’ to the USSR were assisted into power in the satellite states. This map shows the westward expansion of the USSR, and its growing control over ‘satellite states’ in Eastern and Central Europe between 1945 and 1948. (Mosedschurte, CC BY-SA 3. 0 unported)

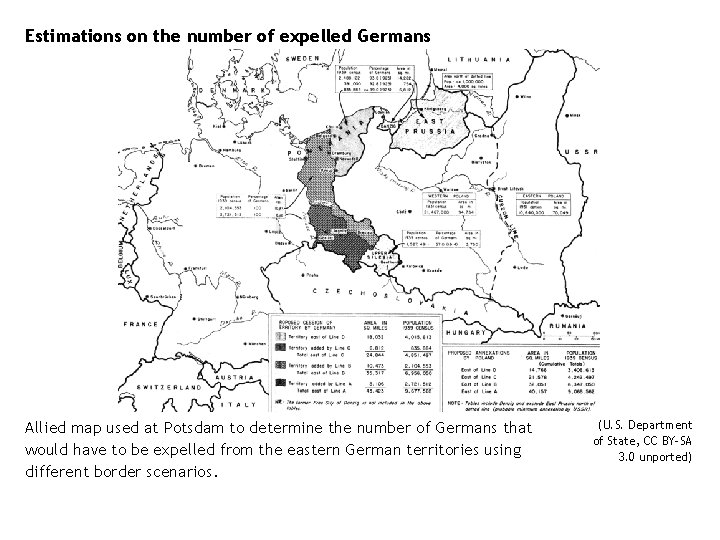

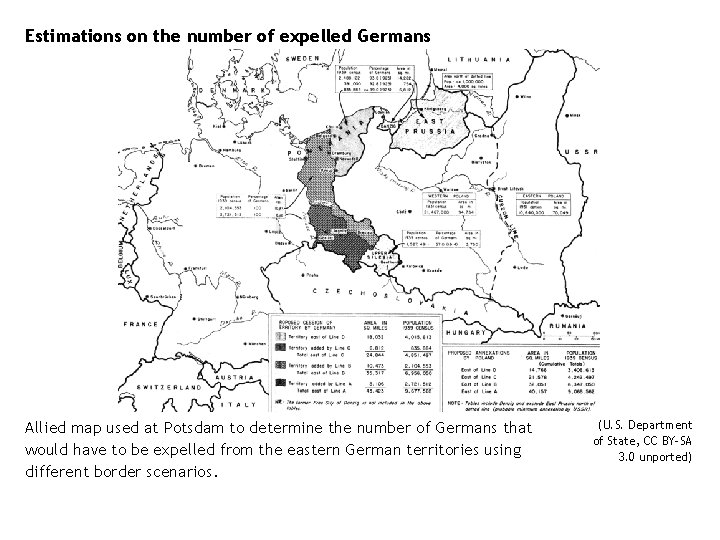

Estimations on the number of expelled Germans Allied map used at Potsdam to determine the number of Germans that would have to be expelled from the eastern German territories using different border scenarios. (U. S. Department of State, CC BY-SA 3. 0 unported)

Germany The Soviet war memorial in Treptower Park, East Berlin. (Pubic Domain) From 1945, the key to Stalin’s aims in Europe was Germany, and its capital Berlin. Stalin pushed the Red Army into costly offensives in order to capture Berlin before the western allies reached the city. He believed that Berlin should be a single city, predominantly under Soviet control and influence – and that such control over Berlin was the rightful reward for the huge sacrifices that had been made by the USSR to achieve victory over Nazism. Subsequent events were unwelcome to Stalin. The Four-power occupation led to separate administrations in the western zones in Berlin, and in the western parts of Germany. In June 1948, Stalin launched the Berlin Blockade in order to regain the Soviet control of the city that had briefly existed in 1945. When this blockade was defeated by the Berlin Airlift, the division of Berlin, and of Germany, became permanent, something Stalin had never wanted or envisaged.

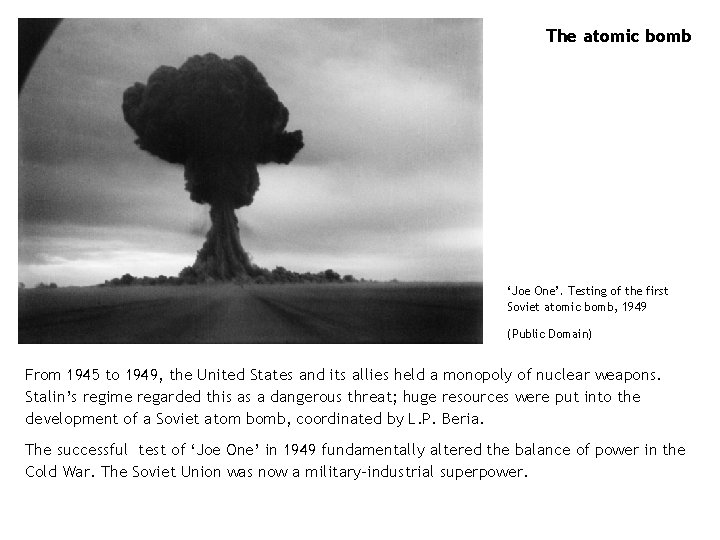

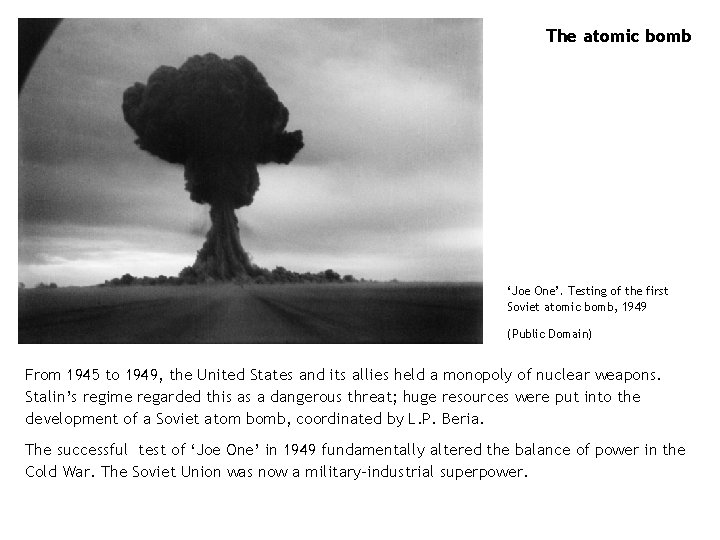

The atomic bomb ‘Joe One’. Testing of the first Soviet atomic bomb, 1949 (Public Domain) From 1945 to 1949, the United States and its allies held a monopoly of nuclear weapons. Stalin’s regime regarded this as a dangerous threat; huge resources were put into the development of a Soviet atom bomb, coordinated by L. P. Beria. The successful test of ‘Joe One’ in 1949 fundamentally altered the balance of power in the Cold War. The Soviet Union was now a military-industrial superpower.

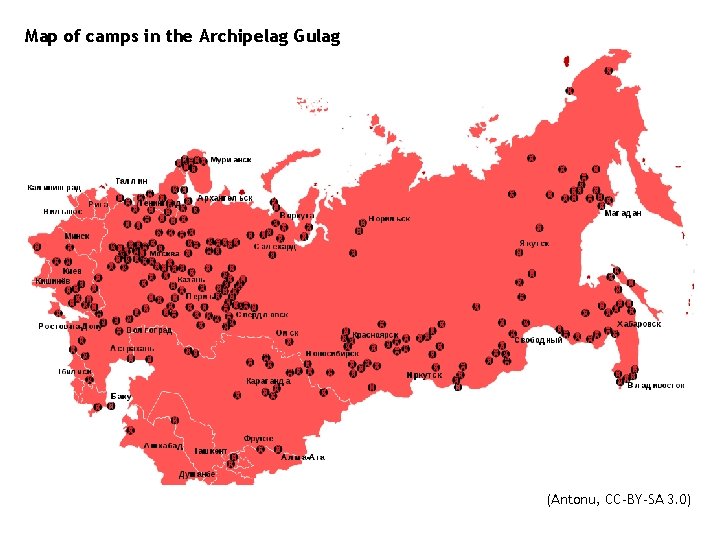

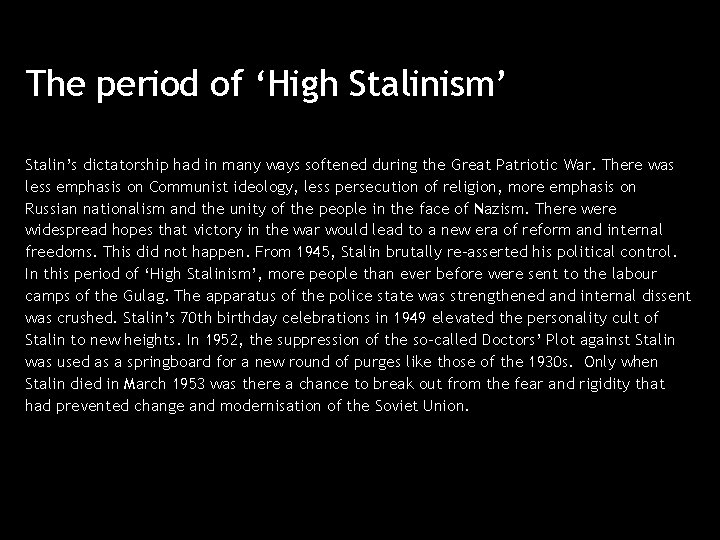

The period of ‘High Stalinism’ Stalin’s dictatorship had in many ways softened during the Great Patriotic War. There was less emphasis on Communist ideology, less persecution of religion, more emphasis on Russian nationalism and the unity of the people in the face of Nazism. There widespread hopes that victory in the war would lead to a new era of reform and internal freedoms. This did not happen. From 1945, Stalin brutally re-asserted his political control. In this period of ‘High Stalinism’, more people than ever before were sent to the labour camps of the Gulag. The apparatus of the police state was strengthened and internal dissent was crushed. Stalin’s 70 th birthday celebrations in 1949 elevated the personality cult of Stalin to new heights. In 1952, the suppression of the so-called Doctors’ Plot against Stalin was used as a springboard for a new round of purges like those of the 1930 s. Only when Stalin died in March 1953 was there a chance to break out from the fear and rigidity that had prevented change and modernisation of the Soviet Union.

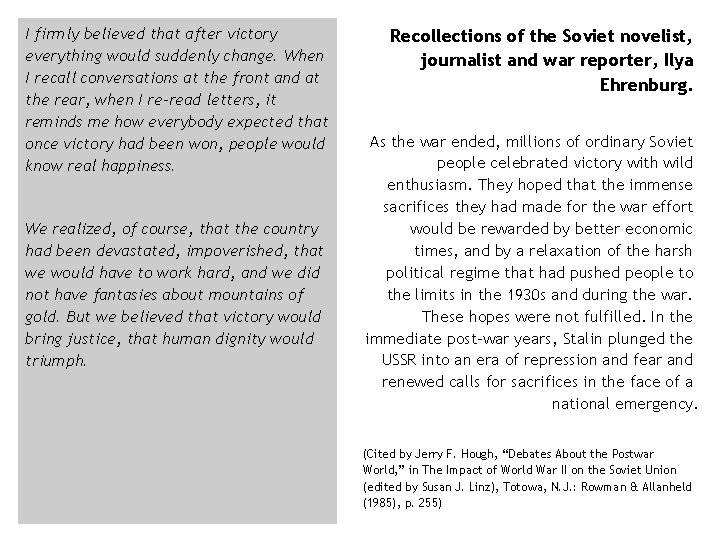

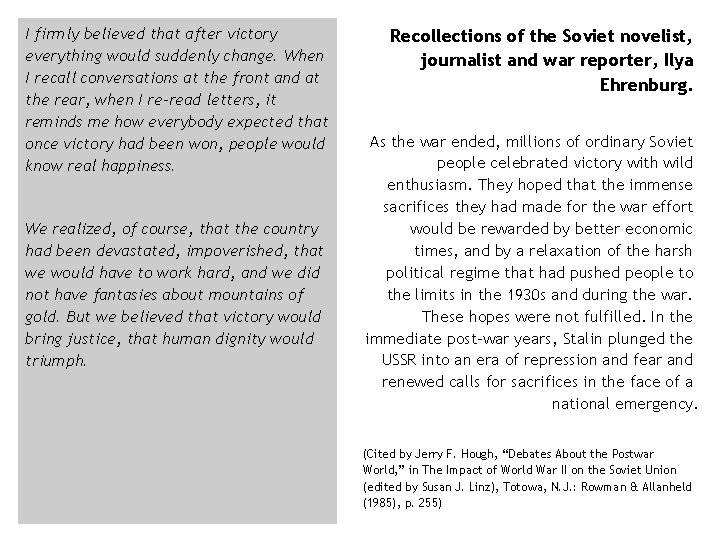

I firmly believed that after victory everything would suddenly change. When I recall conversations at the front and at the rear, when I re-read letters, it reminds me how everybody expected that once victory had been won, people would know real happiness. We realized, of course, that the country had been devastated, impoverished, that we would have to work hard, and we did not have fantasies about mountains of gold. But we believed that victory would bring justice, that human dignity would triumph. Recollections of the Soviet novelist, journalist and war reporter, Ilya Ehrenburg. As the war ended, millions of ordinary Soviet people celebrated victory with wild enthusiasm. They hoped that the immense sacrifices they had made for the war effort would be rewarded by better economic times, and by a relaxation of the harsh political regime that had pushed people to the limits in the 1930 s and during the war. These hopes were not fulfilled. In the immediate post-war years, Stalin plunged the USSR into an era of repression and fear and renewed calls for sacrifices in the face of a national emergency. (Cited by Jerry F. Hough, “Debates About the Postwar World, ” in The Impact of World War II on the Soviet Union (edited by Susan J. Linz), Totowa, N. J. : Rowman & Allanheld (1985), p. 255)

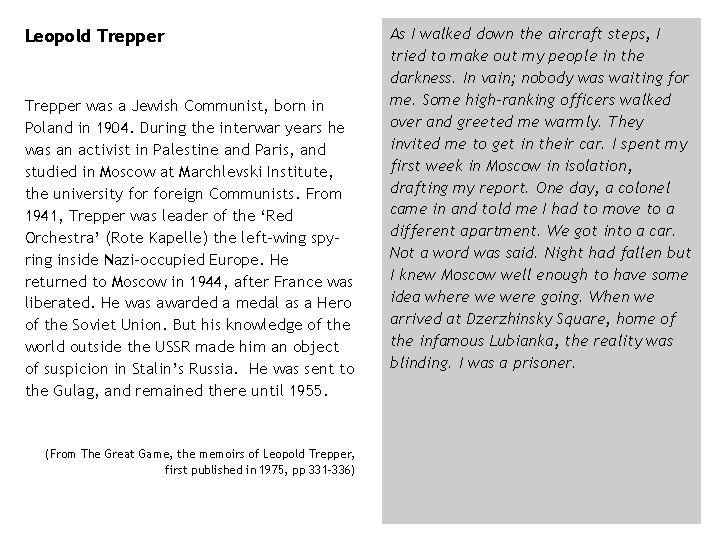

Leopold Trepper was a Jewish Communist, born in Poland in 1904. During the interwar years he was an activist in Palestine and Paris, and studied in Moscow at Marchlevski Institute, the university foreign Communists. From 1941, Trepper was leader of the ‘Red Orchestra’ (Rote Kapelle) the left-wing spyring inside Nazi-occupied Europe. He returned to Moscow in 1944, after France was liberated. He was awarded a medal as a Hero of the Soviet Union. But his knowledge of the world outside the USSR made him an object of suspicion in Stalin’s Russia. He was sent to the Gulag, and remained there until 1955. (From The Great Game, the memoirs of Leopold Trepper, first published in 1975, pp 331 -336) As I walked down the aircraft steps, I tried to make out my people in the darkness. In vain; nobody was waiting for me. Some high-ranking officers walked over and greeted me warmly. They invited me to get in their car. I spent my first week in Moscow in isolation, drafting my report. One day, a colonel came in and told me I had to move to a different apartment. We got into a car. Not a word was said. Night had fallen but I knew Moscow well enough to have some idea where we were going. When we arrived at Dzerzhinsky Square, home of the infamous Lubianka, the reality was blinding. I was a prisoner.

![1937 1941 1953 thousands In prisons 545 488 276 In camps 821 1501 1728 1937 1941 1953 [thousands] In prisons 545 488 276 In camps 821 1501 1728](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/26f34559aeac9f040302ecbeb0b23dc7/image-21.jpg)

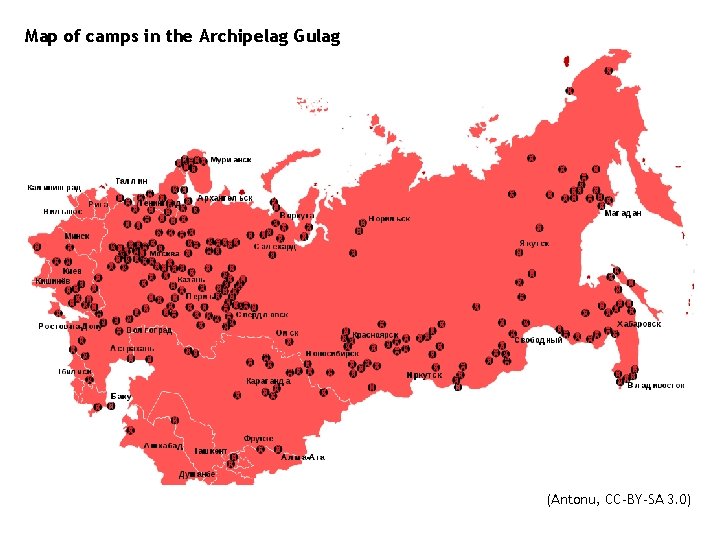

1937 1941 1953 [thousands] In prisons 545 488 276 In camps 821 1501 1728 In ‘colonies’ 375 420 741 In ‘special settlements’ 917 930 2754 Total 2. 66 m Prisoners and Forced Labour, in the USSR 1937 -53 One aspect of renewed repression after 1945 was the increase in the prison population and in the exploitation of forced labour. 3. 36 m 5. 51 m (Graph constructed by Chris Rowe, using source material in RW Davies, soviet economic development from Lenin to Krushchev, Cambridge 1998)

Map of camps in the Archipelag Gulag (Antonu, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

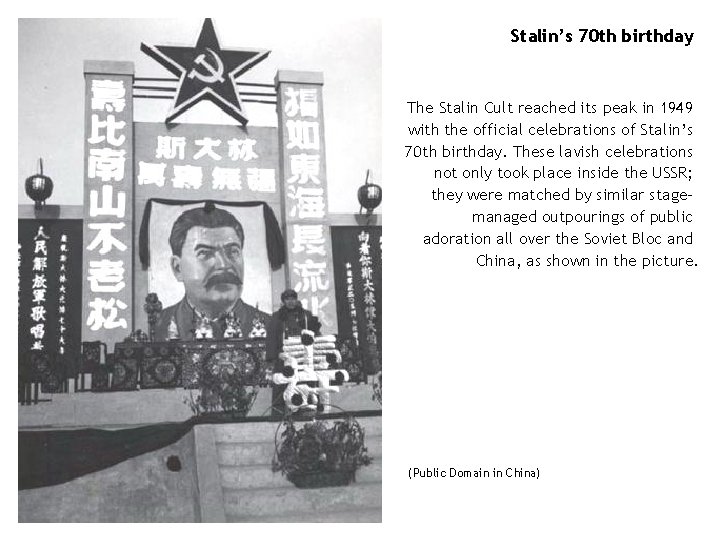

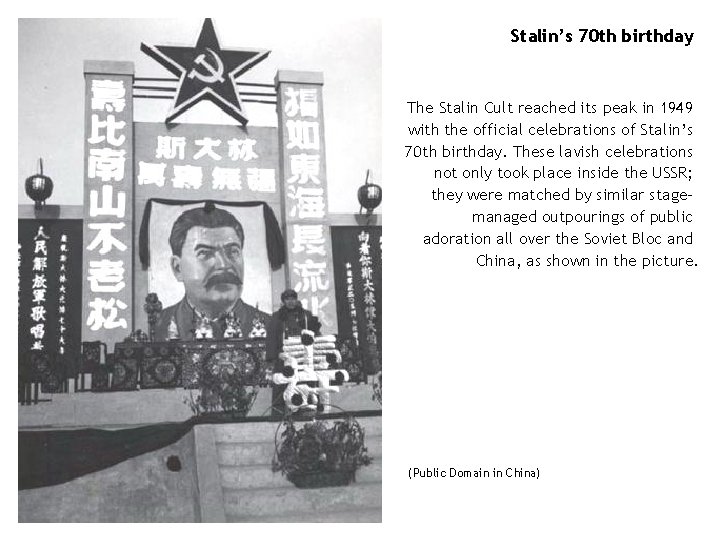

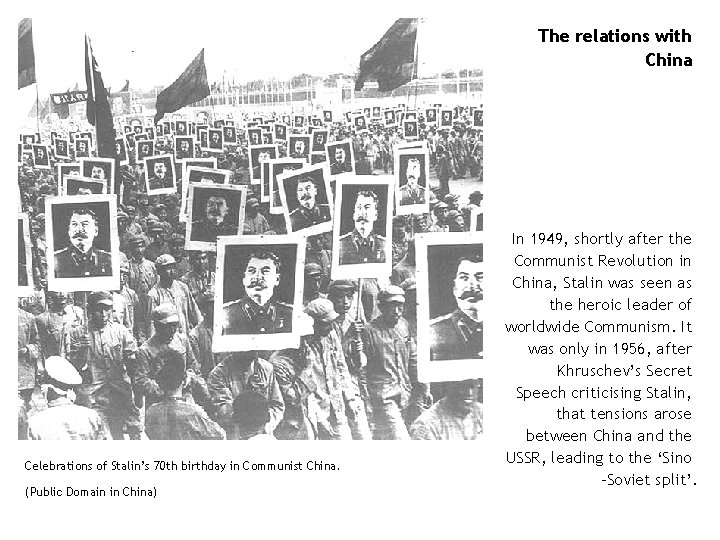

Stalin’s 70 th birthday The Stalin Cult reached its peak in 1949 with the official celebrations of Stalin’s 70 th birthday. These lavish celebrations not only took place inside the USSR; they were matched by similar stagemanaged outpourings of public adoration all over the Soviet Bloc and China, as shown in the picture. (Public Domain in China)

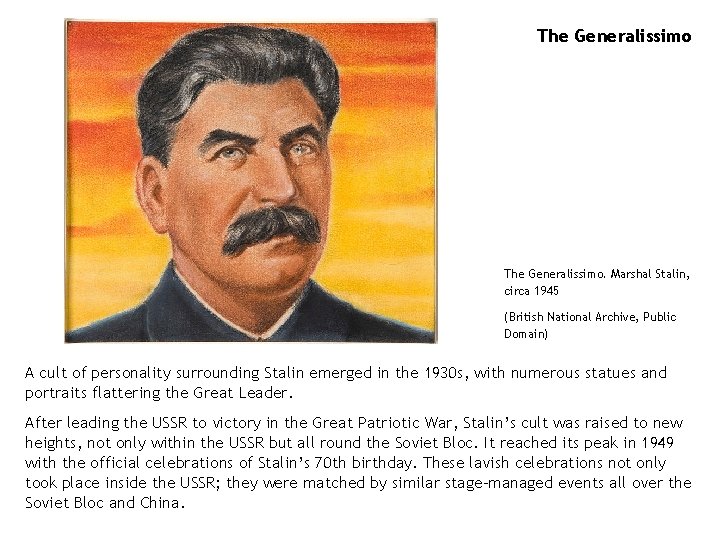

The Generalissimo. Marshal Stalin, circa 1945 (British National Archive, Public Domain) A cult of personality surrounding Stalin emerged in the 1930 s, with numerous statues and portraits flattering the Great Leader. After leading the USSR to victory in the Great Patriotic War, Stalin’s cult was raised to new heights, not only within the USSR but all round the Soviet Bloc. It reached its peak in 1949 with the official celebrations of Stalin’s 70 th birthday. These lavish celebrations not only took place inside the USSR; they were matched by similar stage-managed events all over the Soviet Bloc and China.

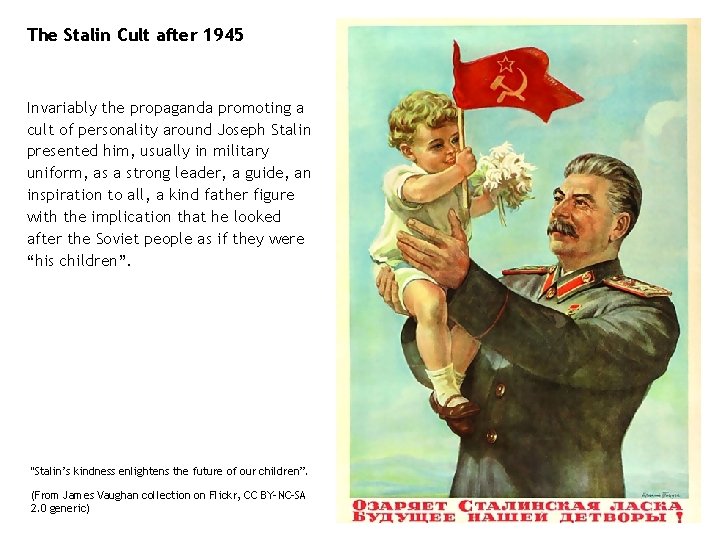

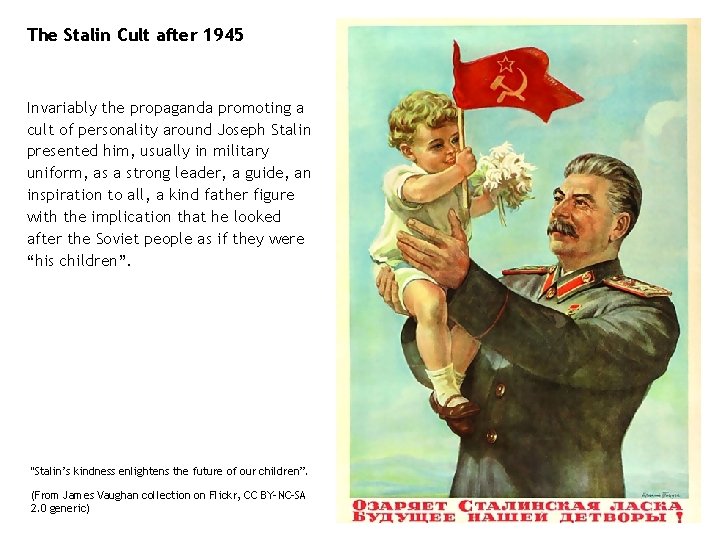

The Stalin Cult after 1945 Invariably the propaganda promoting a cult of personality around Joseph Stalin presented him, usually in military uniform, as a strong leader, a guide, an inspiration to all, a kind father figure with the implication that he looked after the Soviet people as if they were “his children”. "Stalin’s kindness enlightens the future of our children”. (From James Vaughan collection on Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2. 0 generic)

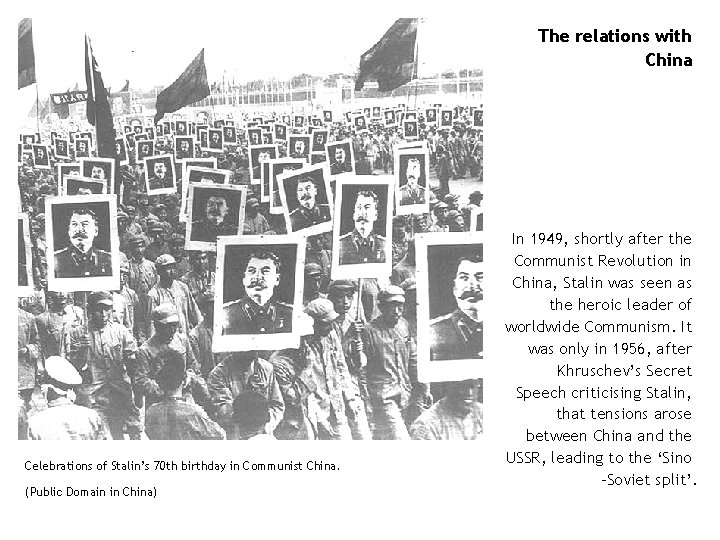

The relations with China Celebrations of Stalin’s 70 th birthday in Communist China. (Public Domain in China) In 1949, shortly after the Communist Revolution in China, Stalin was seen as the heroic leader of worldwide Communism. It was only in 1956, after Khruschev’s Secret Speech criticising Stalin, that tensions arose between China and the USSR, leading to the ‘Sino -Soviet split’.

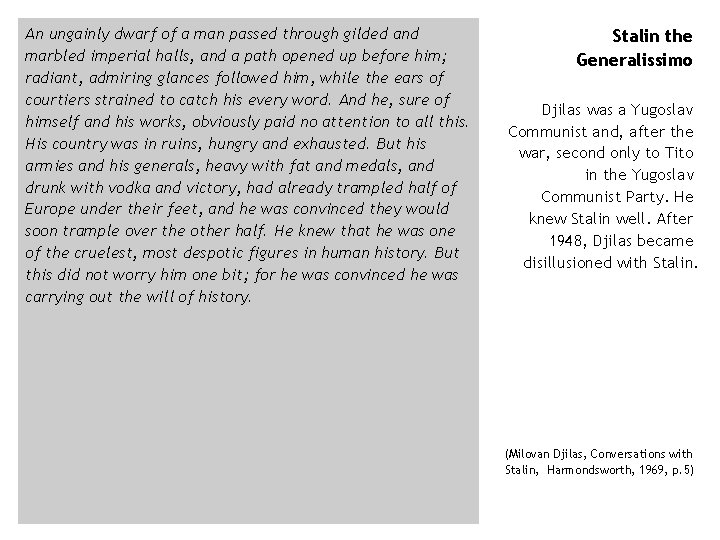

An ungainly dwarf of a man passed through gilded and marbled imperial halls, and a path opened up before him; radiant, admiring glances followed him, while the ears of courtiers strained to catch his every word. And he, sure of himself and his works, obviously paid no attention to all this. His country was in ruins, hungry and exhausted. But his armies and his generals, heavy with fat and medals, and drunk with vodka and victory, had already trampled half of Europe under their feet, and he was convinced they would soon trample over the other half. He knew that he was one of the cruelest, most despotic figures in human history. But this did not worry him one bit; for he was convinced he was carrying out the will of history. Stalin the Generalissimo Djilas was a Yugoslav Communist and, after the war, second only to Tito in the Yugoslav Communist Party. He knew Stalin well. After 1948, Djilas became disillusioned with Stalin. (Milovan Djilas, Conversations with Stalin, Harmondsworth, 1969, p. 5)

Recollections of Harrison Salisbury Many observers noted the extent to which the Soviet Union became repressed and fearful after the end of the war in 1945. Some historians regard this period of High Stalinism as a new development, influenced by Stalin’s increasing paranoia; others regard it as a return to the methods of terror he had already used in the later 1930 s. (Recollections of Harrison Salisbury, an American journalist who had worked in Moscow during the war and made a return visit in 1949) I’d first gone to Moscow in 1944, during the war. At that time, of course, we were still allies; there was still a certain camaraderie and a feeling of being together. All that was gone when I returned in 1949. I had many friends in Moscow, from the war. I telephoned several of them. Either the telephone did not answer or they hung up when they heard my voice. As I walked along Gorky Street, I would meet people I knew. At first, I tried to speak to them, but they would look right through me. I quickly understood that it was too dangerous for them to talk to me. I was regarded at that time by the police and the government, I suppose, as a dangerous spy. For any Russian to have any contact with me might lead to arrest, and possibly a one-way ticket to Siberia.

The Cultural Purge Andrei Zhdanov, leader of the Communist Party in Leningrad and a key figure in the Stalin regime after 1945. (Public Domain) From 1948, Andrei Zhdanov was put in charge of a harsh crackdown on any aspects of Soviet arts and culture that were ‘politically unreliable’. Many writers and composers were intimidated during this cultural purge, known as the ‘Zhdanovschina’. In 1949 Zhdanov, a heavy drinker, died of a massive heart attack in a sanitarium in Moscow. Prior to his death he had been relieved of his post by Stalin. Some claim this was because of his drinking others that he had angered Stalin because he had not condemned Yugoslavia as strongly as Malenkov at the meeting in 1948 of the Cominform. Four years after his death, Stalin claimed that Zhdanov had been a victim of the Doctors’ Plot.

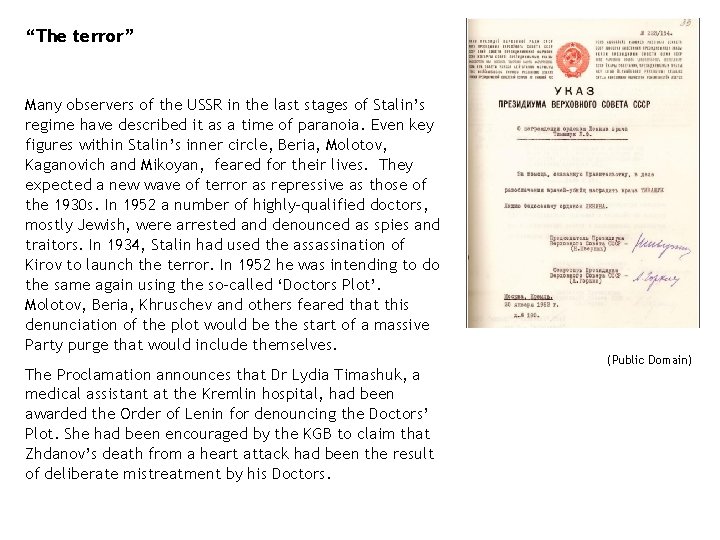

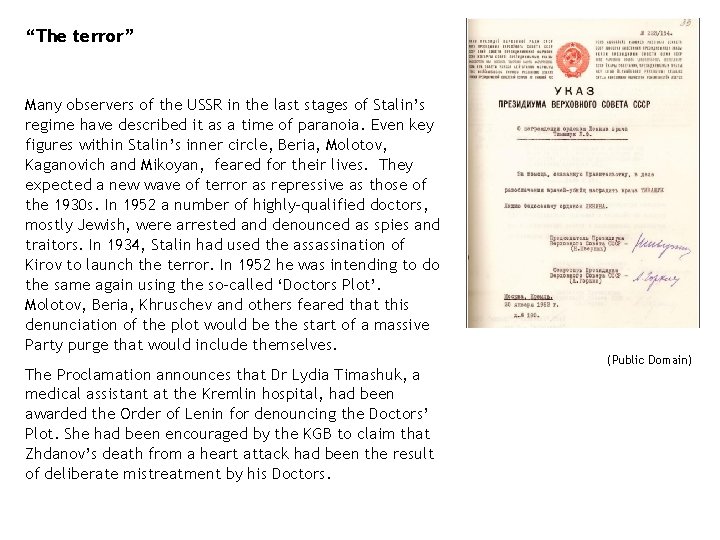

“The terror” Many observers of the USSR in the last stages of Stalin’s regime have described it as a time of paranoia. Even key figures within Stalin’s inner circle, Beria, Molotov, Kaganovich and Mikoyan, feared for their lives. They expected a new wave of terror as repressive as those of the 1930 s. In 1952 a number of highly-qualified doctors, mostly Jewish, were arrested and denounced as spies and traitors. In 1934, Stalin had used the assassination of Kirov to launch the terror. In 1952 he was intending to do the same again using the so-called ‘Doctors Plot’. Molotov, Beria, Khruschev and others feared that this denunciation of the plot would be the start of a massive Party purge that would include themselves. The Proclamation announces that Dr Lydia Timashuk, a medical assistant at the Kremlin hospital, had been awarded the Order of Lenin for denouncing the Doctors’ Plot. She had been encouraged by the KGB to claim that Zhdanov’s death from a heart attack had been the result of deliberate mistreatment by his Doctors. (Public Domain)

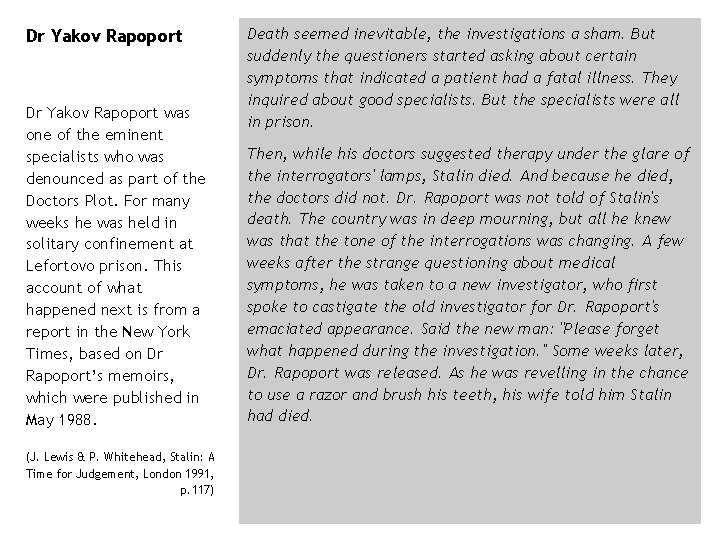

Dr Yakov Rapoport was one of the eminent specialists who was denounced as part of the Doctors Plot. For many weeks he was held in solitary confinement at Lefortovo prison. This account of what happened next is from a report in the New York Times, based on Dr Rapoport’s memoirs, which were published in May 1988. (J. Lewis & P. Whitehead, Stalin: A Time for Judgement, London 1991, p. 117) Death seemed inevitable, the investigations a sham. But suddenly the questioners started asking about certain symptoms that indicated a patient had a fatal illness. They inquired about good specialists. But the specialists were all in prison. Then, while his doctors suggested therapy under the glare of the interrogators' lamps, Stalin died. And because he died, the doctors did not. Dr. Rapoport was not told of Stalin's death. The country was in deep mourning, but all he knew was that the tone of the interrogations was changing. A few weeks after the strange questioning about medical symptoms, he was taken to a new investigator, who first spoke to castigate the old investigator for Dr. Rapoport's emaciated appearance. Said the new man: ''Please forget what happened during the investigation. '' Some weeks later, Dr. Rapoport was released. As he was revelling in the chance to use a razor and brush his teeth, his wife told him Stalin had died.

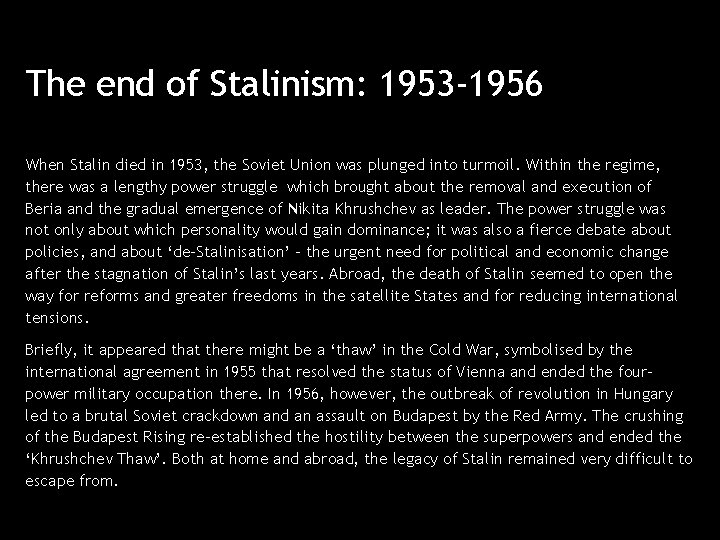

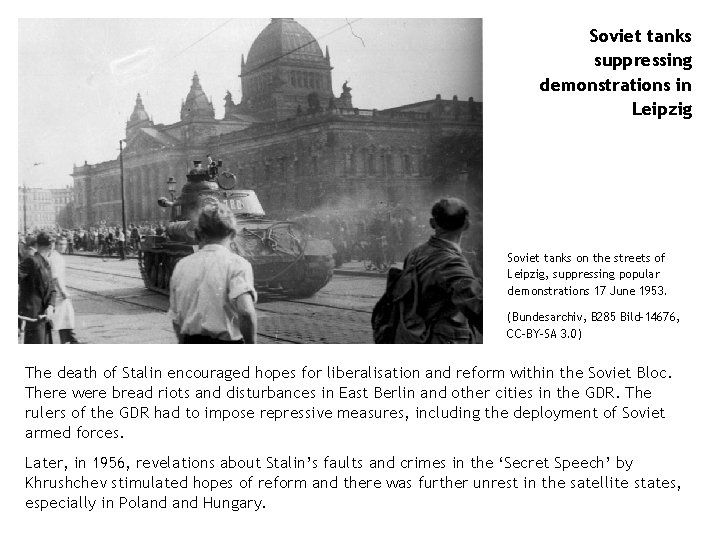

The end of Stalinism: 1953 -1956 When Stalin died in 1953, the Soviet Union was plunged into turmoil. Within the regime, there was a lengthy power struggle which brought about the removal and execution of Beria and the gradual emergence of Nikita Khrushchev as leader. The power struggle was not only about which personality would gain dominance; it was also a fierce debate about policies, and about ‘de-Stalinisation’ - the urgent need for political and economic change after the stagnation of Stalin’s last years. Abroad, the death of Stalin seemed to open the way for reforms and greater freedoms in the satellite States and for reducing international tensions. Briefly, it appeared that there might be a ‘thaw’ in the Cold War, symbolised by the international agreement in 1955 that resolved the status of Vienna and ended the fourpower military occupation there. In 1956, however, the outbreak of revolution in Hungary led to a brutal Soviet crackdown and an assault on Budapest by the Red Army. The crushing of the Budapest Rising re-established the hostility between the superpowers and ended the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’. Both at home and abroad, the legacy of Stalin remained very difficult to escape from.

Two Prisoners in Labour Camps recall how they felt on hearing the news that Stalin was dead. First part: Lev Kopelev, a committed Communist, who in later life changed his mind about Stalin and his regime. Second part: Alice Mulkigian, a young woman, who was an American citizen who spent five years imprisoned in a women’s labour camp in Kazakhstan (J. Lewis & P. Whitehead, Stalin: A Time for Judgement, London 1991, p. 129) At that time I still thought that, for all his faults, Stalin was the last real Communist in the Politburo – that he really wanted something good – and I even cried in secret. I’m not ashamed to admit it, but when they were burying him and the horns were blowing I went into an empty hut where there was nobody , so I could not be seen by either my comrade prisoners or by the guards; and I cried, because I knew that when my brother had perished in the war he had died shouting for the Motherland, and for Stalin. There were actually women in the camp who cried when they heard the news Stalin had died, but 99 per cent just jumped for joy and said, ‘Today is a Holiday!’ We all had a cup of tea and we celebrated because Stalin was dead, and we all said, ‘None too soon!’. It was one of the happiest moments, and we felt that something good was going to happen, because things just could not have continued as they were.

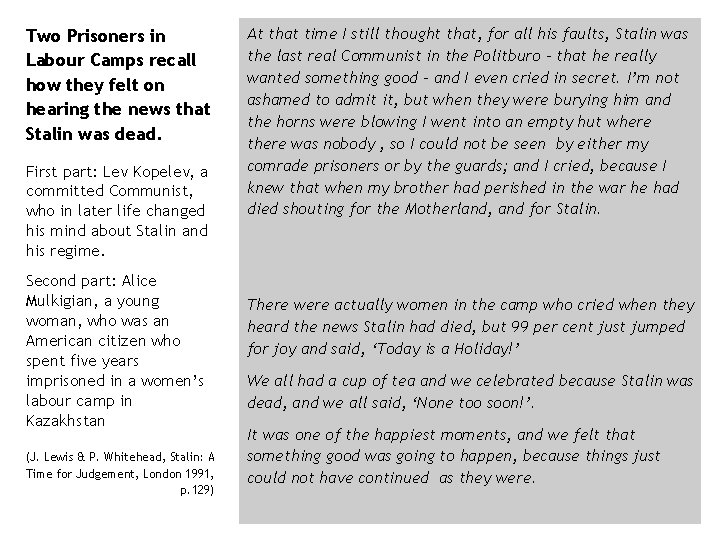

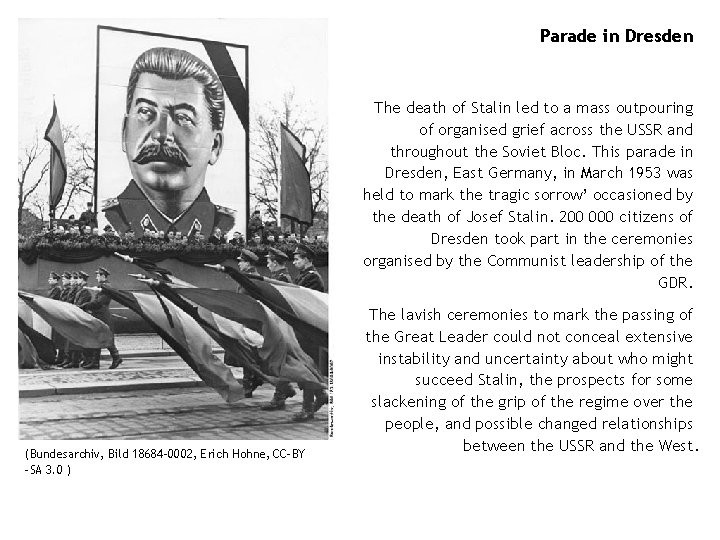

Parade in Dresden The death of Stalin led to a mass outpouring of organised grief across the USSR and throughout the Soviet Bloc. This parade in Dresden, East Germany, in March 1953 was held to mark the tragic sorrow’ occasioned by the death of Josef Stalin. 200 000 citizens of Dresden took part in the ceremonies organised by the Communist leadership of the GDR. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 18684 -0002, Erich Hohne, CC-BY -SA 3. 0 ) The lavish ceremonies to mark the passing of the Great Leader could not conceal extensive instability and uncertainty about who might succeed Stalin, the prospects for some slackening of the grip of the regime over the people, and possible changed relationships between the USSR and the West.

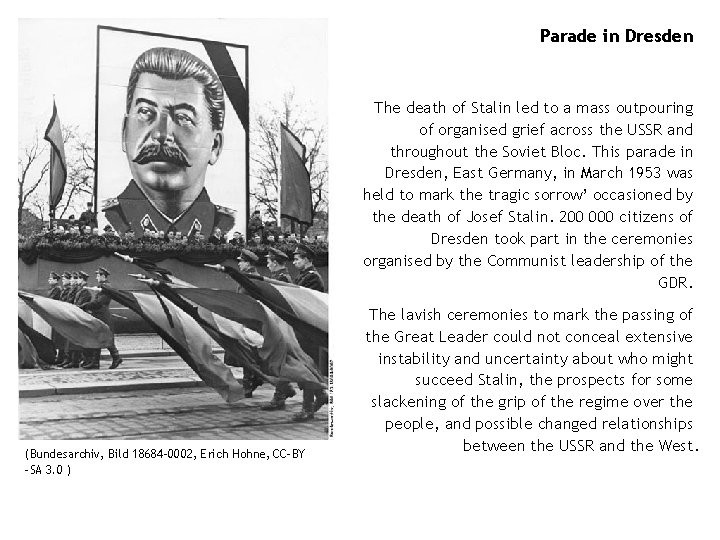

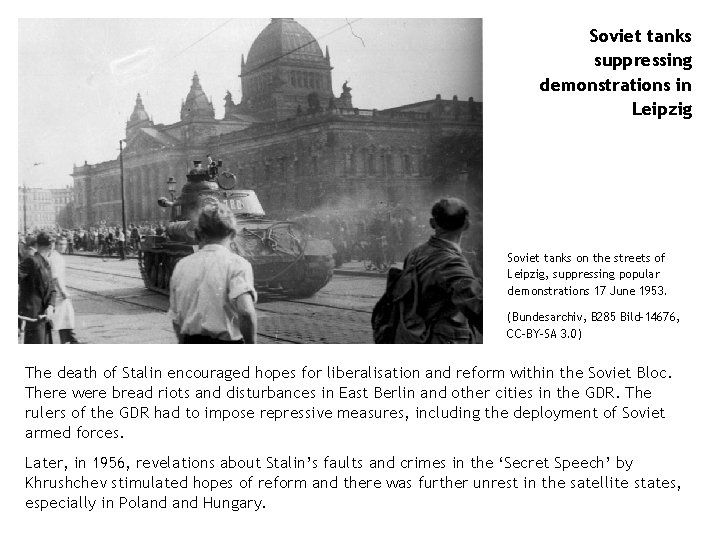

Soviet tanks suppressing demonstrations in Leipzig Soviet tanks on the streets of Leipzig, suppressing popular demonstrations 17 June 1953. (Bundesarchiv, B 285 Bild-14676, CC-BY-SA 3. 0) The death of Stalin encouraged hopes for liberalisation and reform within the Soviet Bloc. There were bread riots and disturbances in East Berlin and other cities in the GDR. The rulers of the GDR had to impose repressive measures, including the deployment of Soviet armed forces. Later, in 1956, revelations about Stalin’s faults and crimes in the ‘Secret Speech’ by Khrushchev stimulated hopes of reform and there was further unrest in the satellite states, especially in Poland Hungary.

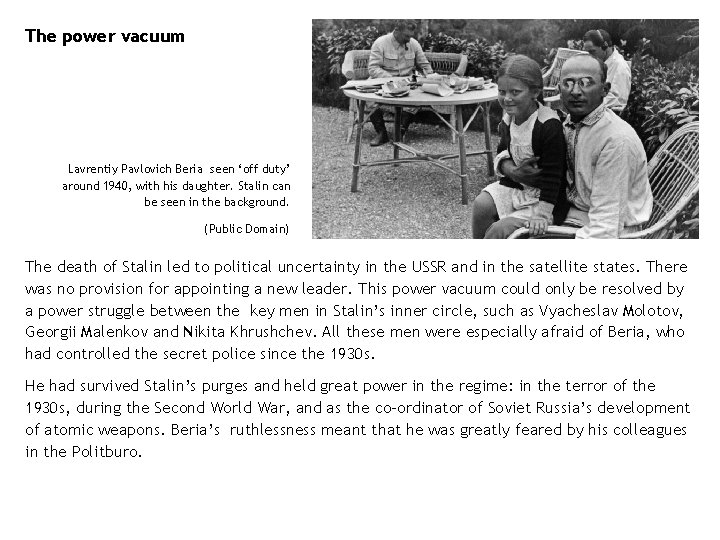

The power vacuum Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria seen ‘off duty’ around 1940, with his daughter. Stalin can be seen in the background. (Public Domain) The death of Stalin led to political uncertainty in the USSR and in the satellite states. There was no provision for appointing a new leader. This power vacuum could only be resolved by a power struggle between the key men in Stalin’s inner circle, such as Vyacheslav Molotov, Georgii Malenkov and Nikita Khrushchev. All these men were especially afraid of Beria, who had controlled the secret police since the 1930 s. He had survived Stalin’s purges and held great power in the regime: in the terror of the 1930 s, during the Second World War, and as the co-ordinator of Soviet Russia’s development of atomic weapons. Beria’s ruthlessness meant that he was greatly feared by his colleagues in the Politburo.

The removal of Beria An account of the removal of Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria in the power struggle that followed the death of Stalin in March 1953. (HISTORY TODAY Volume 53 Issue 12, December 2003) On June 26 th, at a hastily convened meeting of the Presidium, Khrushchev launched a blistering attack on Beria, accusing him of being a cynical careerist, long in the pay of British intelligence, and no true Communist. Beria was taken aback and said, ‘What’s going on, Nikita? ’. Khrushchev told him he would soon find out. Molotov and others chimed in against Beria and Khrushchev proposed a motion for his instant dismissal. Before a vote could be taken, the panicky Malenkov pressed a button on his desk as the pre-arranged signal to Marshal Zhukov and a group of armed soldiers in a nearby room. They immediately burst in, seized Beria and manhandled him away. Beria’s men were guarding the Kremlin, so Zhukov had to wait until nightfall before smuggling Beria out in the back of a car. He was taken first to the Lefortovo Prison and subsequently to the headquarters of General Moskalenko, commander of Moscow District Air Defence, where he was imprisoned in an underground bunker. Beria’s arrest was kept as quiet as possible while his principal supporters were rounded up – some were rumoured to have been shot out of hand – and regular troops were moved into Moscow. Then the Central Committee of the Party spent five days convincing itself of Beria’s guilt before an experienced prosecutor, loyal to Khrushchev, was appointed to make certain that Beria was tried, condemned and executed with the maximum appearance of legality. Beria was finally executed on 23 December 1953.

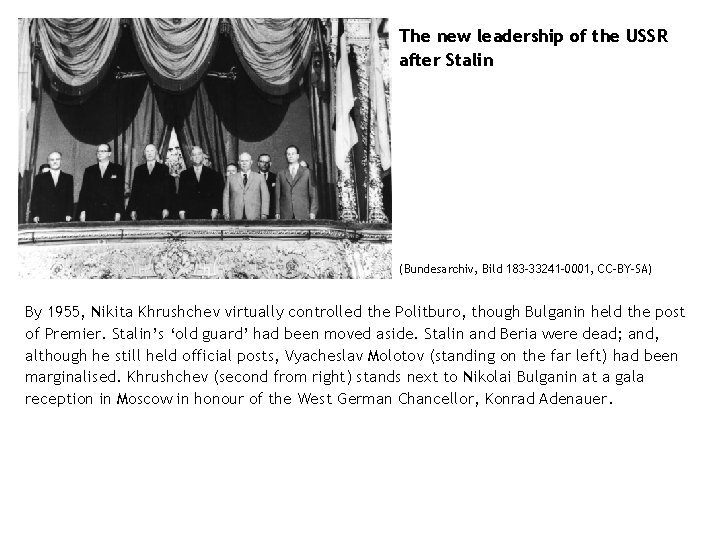

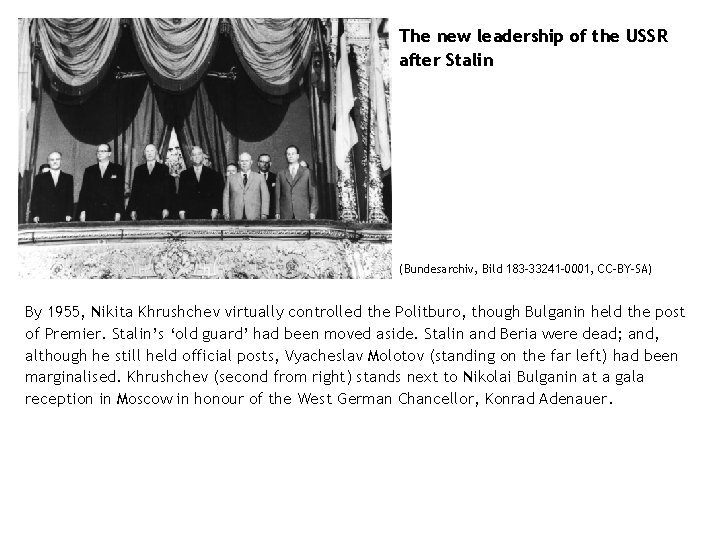

The new leadership of the USSR after Stalin (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183 -33241 -0001, CC-BY-SA) By 1955, Nikita Khrushchev virtually controlled the Politburo, though Bulganin held the post of Premier. Stalin’s ‘old guard’ had been moved aside. Stalin and Beria were dead; and, although he still held official posts, Vyacheslav Molotov (standing on the far left) had been marginalised. Khrushchev (second from right) stands next to Nikolai Bulganin at a gala reception in Moscow in honour of the West German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer.

The Krushchev Thaw (Public Domain in China and the US) From 1954, the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’ improved relations with many foreign countries. There were cultural exchanges with the West. Khrushchev and Bulganin led friendly diplomatic missions to India in 1955, and to Britain and China in 1956. At that time, it was not yet clear that Khrushchev was the dominant leader in the USSR. Many observers wrongly believed he was sharing power with Bulganin. This period of improved international relations did not last. China was offended by the attacks on Stalin in Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’; and the crushing of the Hungarian Rising caused renewed hostility between East and West. Here we see Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin with Chinese Communist officials in February 1956, during the ‘Soviet ‘charm offensive’ to improve foreign relations after the death of Stalin.

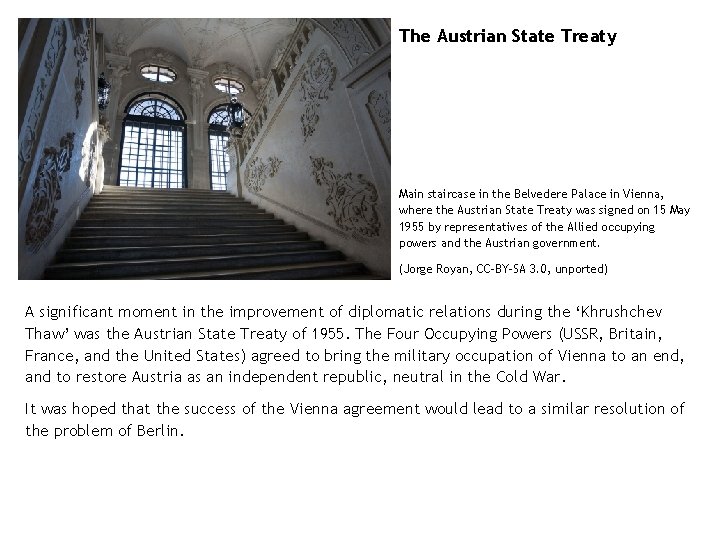

The Austrian State Treaty Main staircase in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna, where the Austrian State Treaty was signed on 15 May 1955 by representatives of the Allied occupying powers and the Austrian government. (Jorge Royan, CC-BY-SA 3. 0, unported) A significant moment in the improvement of diplomatic relations during the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’ was the Austrian State Treaty of 1955. The Four Occupying Powers (USSR, Britain, France, and the United States) agreed to bring the military occupation of Vienna to an end, and to restore Austria as an independent republic, neutral in the Cold War. It was hoped that the success of the Vienna agreement would lead to a similar resolution of the problem of Berlin.

The Austrian State Treaty Negotiations over the future status of Austria began in 1947 but were downgraded in priority because of the importance given to an Allied settlement of the future of Germany. The Cold War climate from 1950 onwards also put a brake on negotiations. After Stalin’s death the Khrushchev thaw led the western powers to believe that a negotiated treaty on Austria was possible. The main obstacle was the neutrality of Austria. Julius Raab, who had succeeded Leopold Figl as Austrian Chancellor on 2 April 1953 replaced his vocal anti-Communist Foreign Minister Karl Gruber with Figl. The new Foreign Minister then used diplomatic channels to ask the Indian government, which had good relations with the USSR, to convince Moscow that an independent Austria would be neutral. In April 1955 Raab was invited to Moscow for meetings with Molotov which led to a draft Treaty. Washington was not particularly happy about being out-manoeuvred but the Treaty was signed by the Four Powers and Austria on 15 May, 1955. (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek)

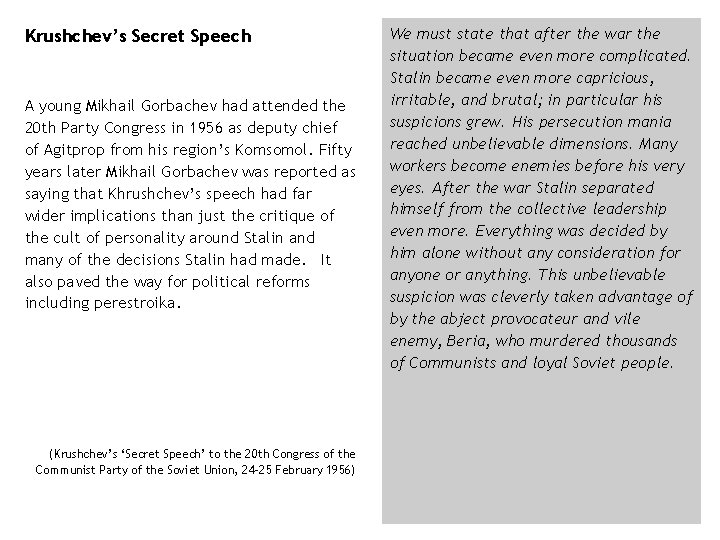

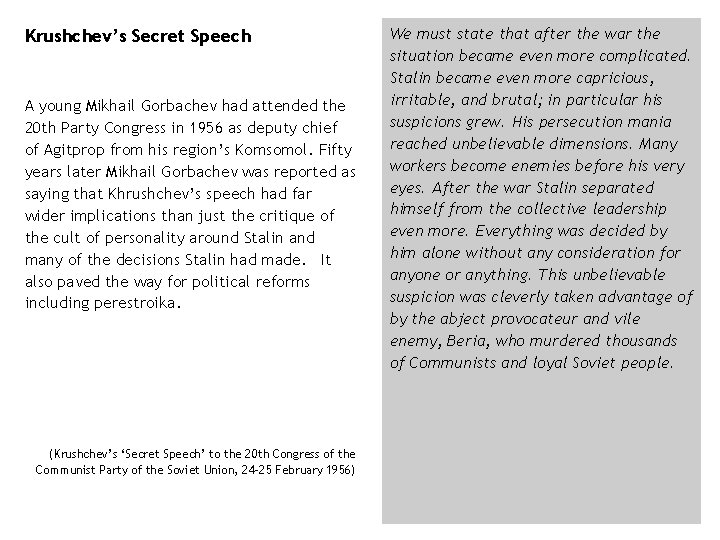

Krushchev’s Secret Speech A young Mikhail Gorbachev had attended the 20 th Party Congress in 1956 as deputy chief of Agitprop from his region’s Komsomol. Fifty years later Mikhail Gorbachev was reported as saying that Khrushchev’s speech had far wider implications than just the critique of the cult of personality around Stalin and many of the decisions Stalin had made. It also paved the way for political reforms including perestroika. (Krushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ to the 20 th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 24 -25 February 1956) We must state that after the war the situation became even more complicated. Stalin became even more capricious, irritable, and brutal; in particular his suspicions grew. His persecution mania reached unbelievable dimensions. Many workers become enemies before his very eyes. After the war Stalin separated himself from the collective leadership even more. Everything was decided by him alone without any consideration for anyone or anything. This unbelievable suspicion was cleverly taken advantage of by the abject provocateur and vile enemy, Beria, who murdered thousands of Communists and loyal Soviet people.

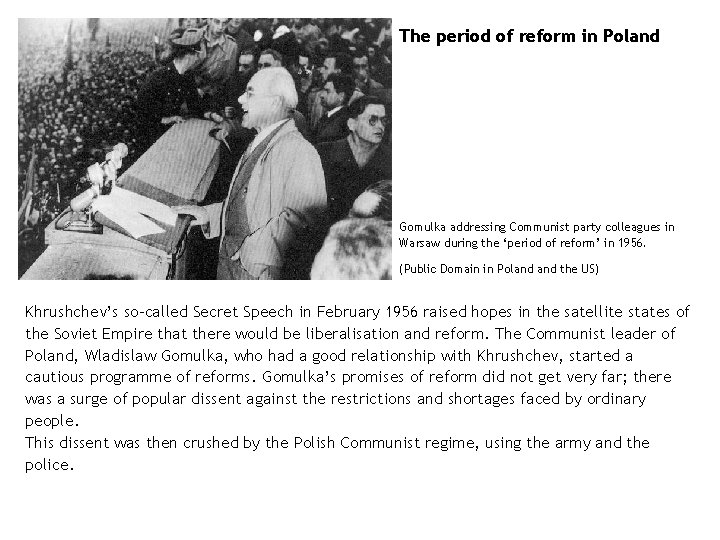

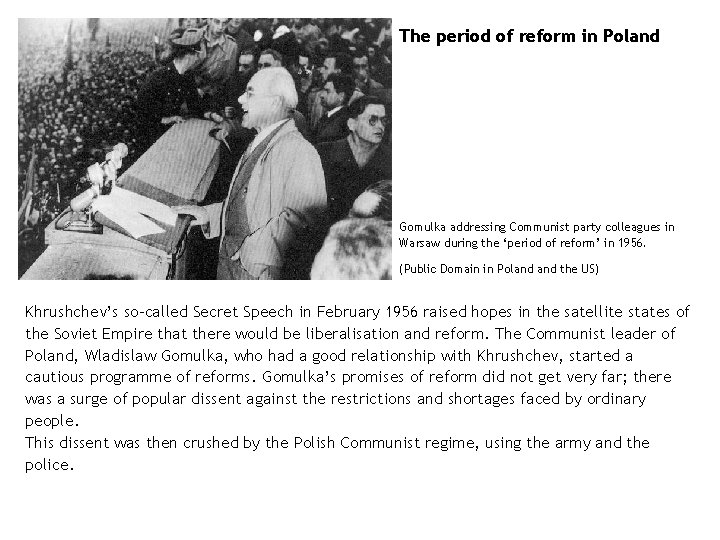

The period of reform in Poland Gomulka addressing Communist party colleagues in Warsaw during the ‘period of reform’ in 1956. (Public Domain in Poland the US) Khrushchev’s so-called Secret Speech in February 1956 raised hopes in the satellite states of the Soviet Empire that there would be liberalisation and reform. The Communist leader of Poland, Wladislaw Gomulka, who had a good relationship with Khrushchev, started a cautious programme of reforms. Gomulka’s promises of reform did not get very far; there was a surge of popular dissent against the restrictions and shortages faced by ordinary people. This dissent was then crushed by the Polish Communist regime, using the army and the police.

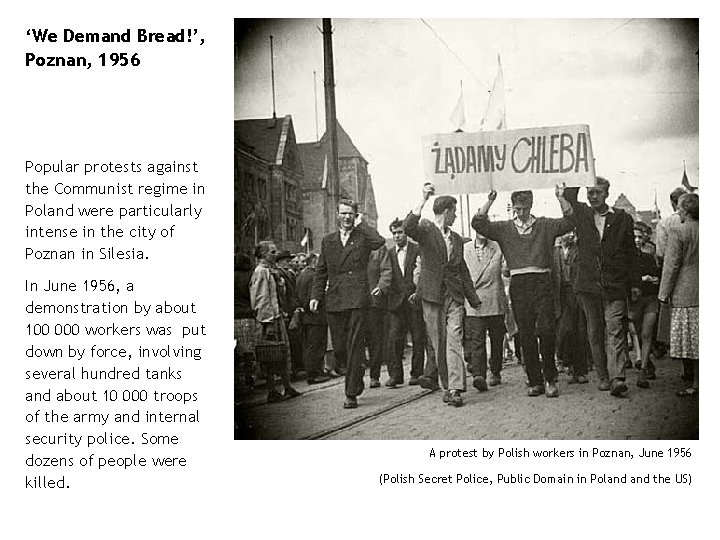

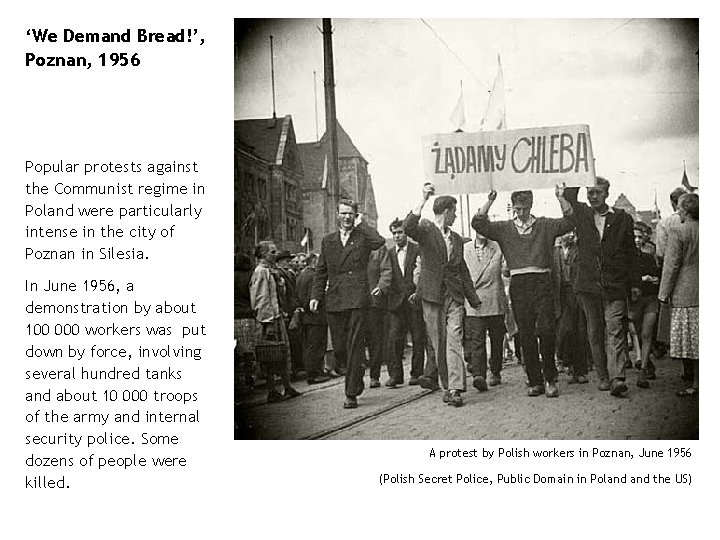

‘We Demand Bread!’, Poznan, 1956 Popular protests against the Communist regime in Poland were particularly intense in the city of Poznan in Silesia. In June 1956, a demonstration by about 100 000 workers was put down by force, involving several hundred tanks and about 10 000 troops of the army and internal security police. Some dozens of people were killed. A protest by Polish workers in Poznan, June 1956 (Polish Secret Police, Public Domain in Poland the US)

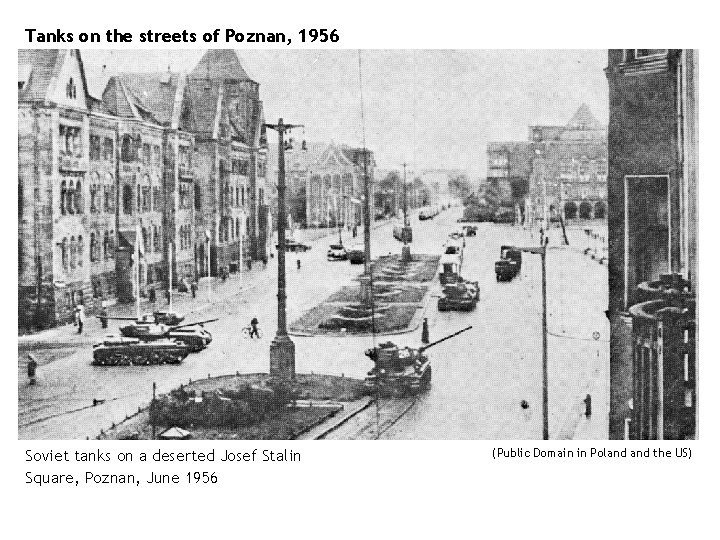

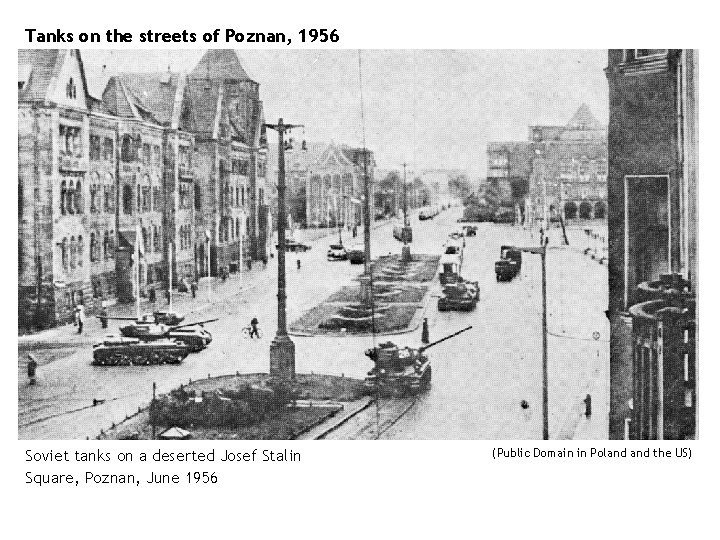

Tanks on the streets of Poznan, 1956 Soviet tanks on a deserted Josef Stalin Square, Poznan, June 1956 (Public Domain in Poland the US)

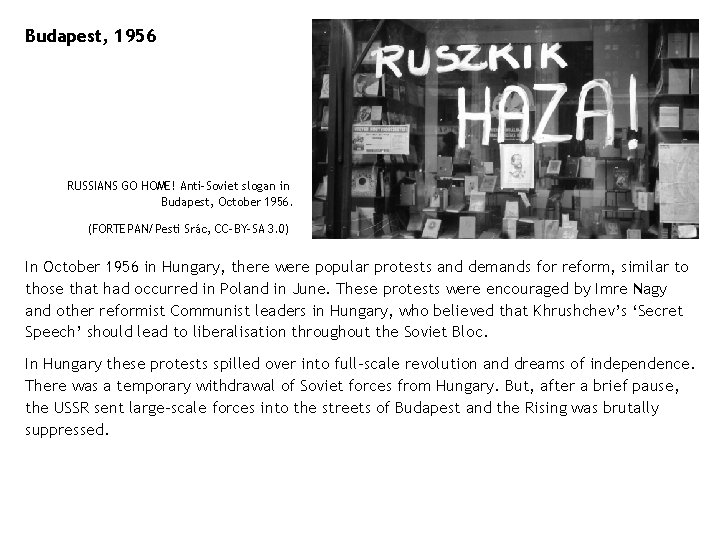

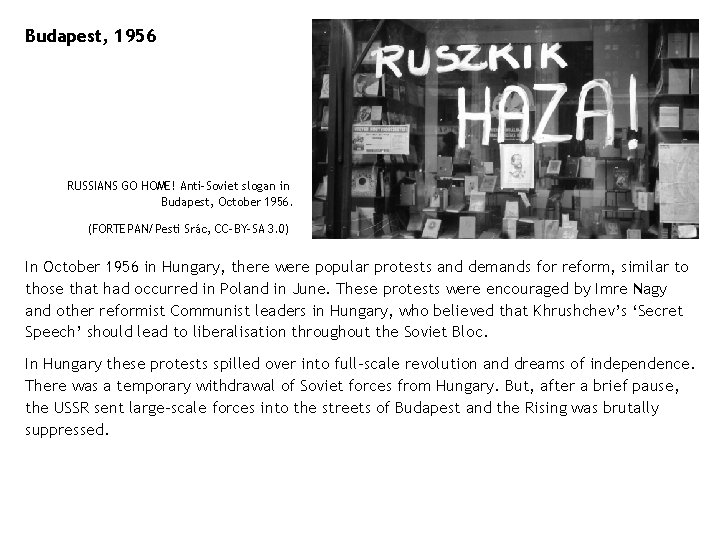

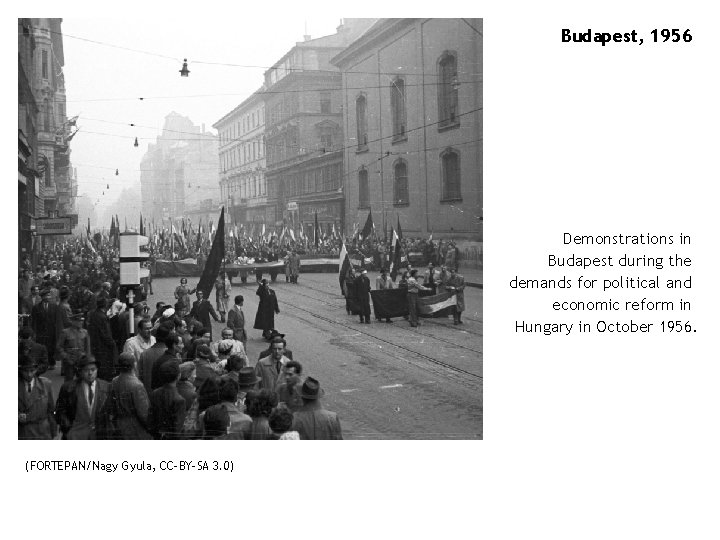

Budapest, 1956 RUSSIANS GO HOME! Anti-Soviet slogan in Budapest, October 1956. (FORTEPAN/Pesti Srác, CC-BY-SA 3. 0) In October 1956 in Hungary, there were popular protests and demands for reform, similar to those that had occurred in Poland in June. These protests were encouraged by Imre Nagy and other reformist Communist leaders in Hungary, who believed that Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ should lead to liberalisation throughout the Soviet Bloc. In Hungary these protests spilled over into full-scale revolution and dreams of independence. There was a temporary withdrawal of Soviet forces from Hungary. But, after a brief pause, the USSR sent large-scale forces into the streets of Budapest and the Rising was brutally suppressed.

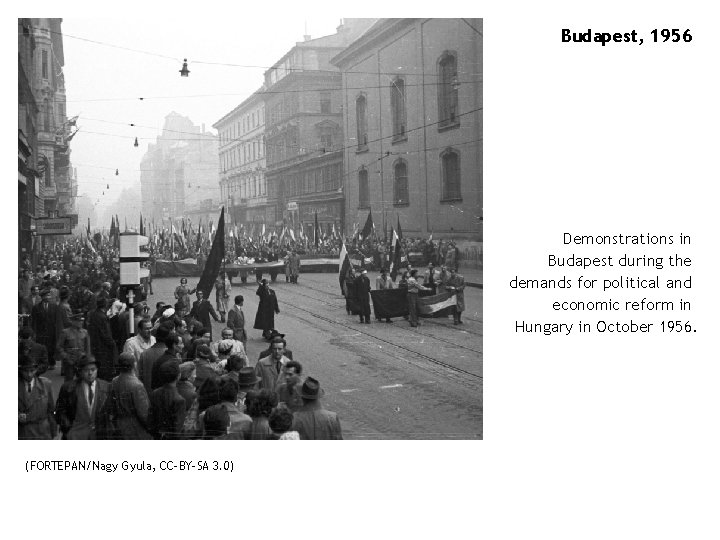

Budapest, 1956 Demonstrations in Budapest during the demands for political and economic reform in Hungary in October 1956. (FORTEPAN/Nagy Gyula, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

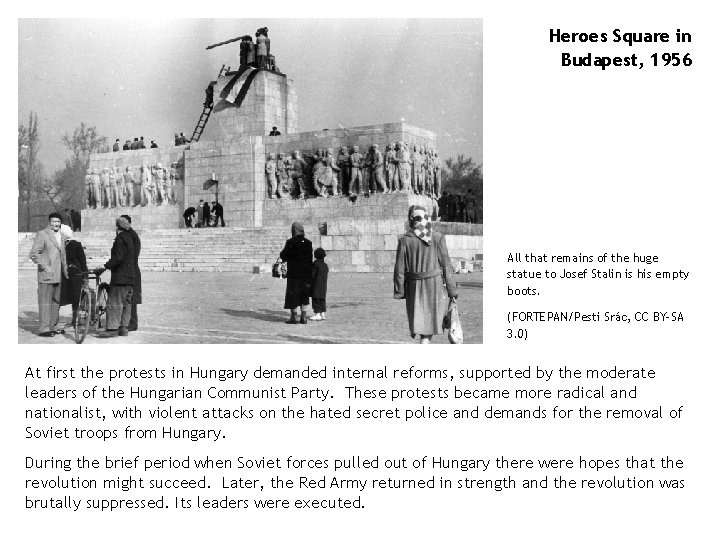

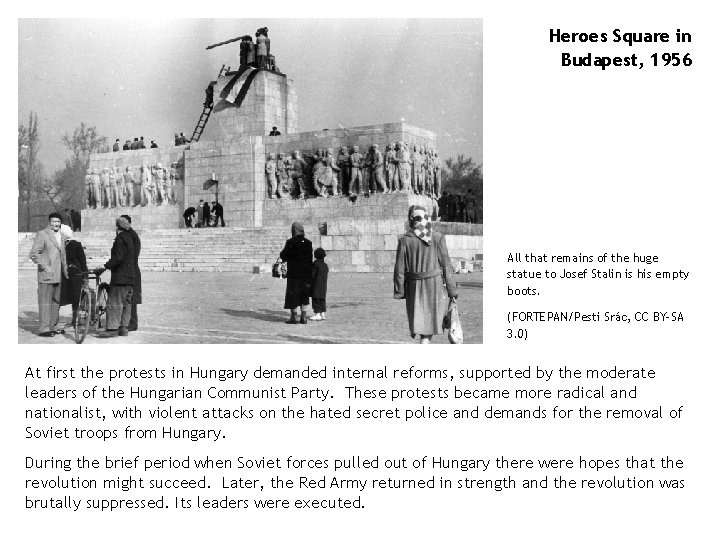

Heroes Square in Budapest, 1956 All that remains of the huge statue to Josef Stalin is his empty boots. (FORTEPAN/Pesti Srác, CC BY-SA 3. 0) At first the protests in Hungary demanded internal reforms, supported by the moderate leaders of the Hungarian Communist Party. These protests became more radical and nationalist, with violent attacks on the hated secret police and demands for the removal of Soviet troops from Hungary. During the brief period when Soviet forces pulled out of Hungary there were hopes that the revolution might succeed. Later, the Red Army returned in strength and the revolution was brutally suppressed. Its leaders were executed.

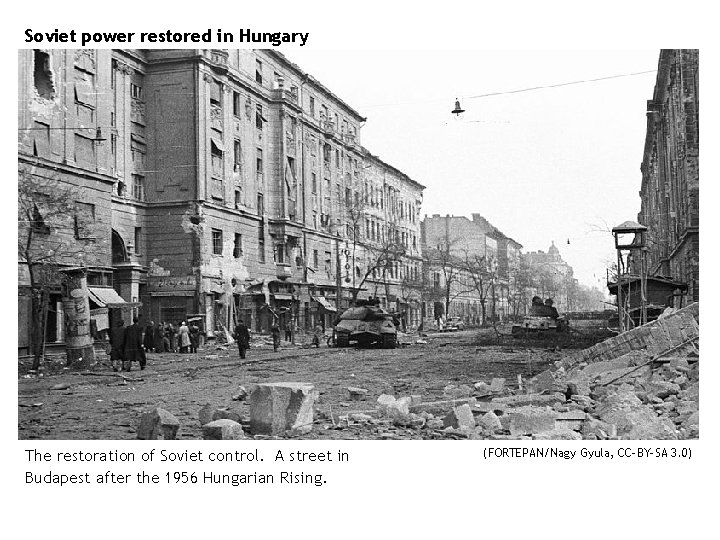

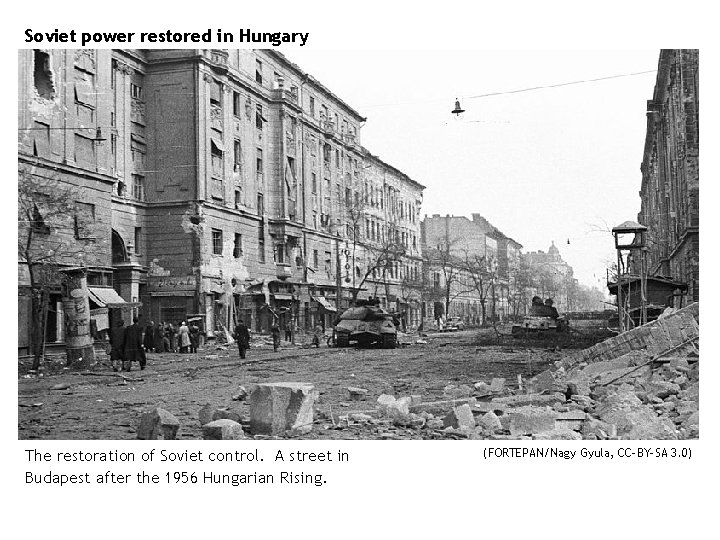

Soviet power restored in Hungary The restoration of Soviet control. A street in Budapest after the 1956 Hungarian Rising. (FORTEPAN/Nagy Gyula, CC-BY-SA 3. 0)

Myth of Liberation Suppression of the Hungarian Revolution by the Soviet Union in 1956 was not the definitive turning point in Western Cold War policy toward Eastern Europe, forcing the West to abandon initiatives aimed at liberating the region from Soviet control. The real turning point in American policy had been in 1953. The East German uprising and mass protests in Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria spawned discussion in Washington of more interventionist “liberation” policies. But by the end of that year the Eisenhower Administration that had assumed office amidst electoral campaign rhetoric of “liberation” concluded in National Security Council Report No. 174 (December 1953) that only an unacceptable war could end Soviet control of Eastern Europe. U. S. policy was formally defined as promoting evolutionary reform within the Soviet European space rather than liberation as revolutionary change. This policy reflected the conclusions of some twenty U. S. government studies, that Soviet control of Eastern Europe was a fact of life. (A. Ross Johnson, Looking Back at the Cold War: 1956 Wilson Center Cold War International History Project, October 2016)

After Stalin’s death, there were many trips abroad. Khrushchev went to China; in May 1955 to Yugoslavia, then to India, Burma, Indonesia and so on. Very soon, however, Khrushchev began to think that a quiet termination of the Cold War could not be accomplished, because policy-making in the United States remained in the hands of staunch enemies who could be convinced only by force. Two developments in particular influenced this conclusion. One was the relentless policy of encirclement and roll-back of the Soviet Union conducted by John Foster Dulles, the US Secretary of State; the other was a revolt of party leaders within the Soviet system. Expectations and realities The authors were Russian experts whose researches were based on Soviet archives opened up after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The Polish and Hungarian revolts in 1956 took Khrushchev aback. They underlined the fragility of the Socialist camp, and cast a long shadow over Khrushchev’s optimistic expectations. ‘Peaceful co-existence’ remained his long-term project, but he learned a lesson about the bipolar and ‘zerosum’ nature of the Cold War. (Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov, From Inside the Kremlin’s Cold War: From Stalin to Khrushchev, Harvard University Press 1996 pp 186 -7)

STALIN, THE USSR AND THE WORLD 1945 -1956 This collection was developed by Chris Rowe of the Historiana content team. SUPPORTED BY COPYRIGHT AND LICENSE EUROCLIO has tried to contact all copyright holders of materials published on Historiana. Please contact copyright@historiana. eu in case you find that materials have been unrightfully used. License: CC-BY-SA 4. 0, Historiana DISCLAIMER (CC BY-NC-SA 2. 0 generic) The European Commission support for this publication does not constitute of an endorsement of the contents which reflects the view only of the authors, and the European Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained herein. DEVELOPED BY