Radiological Category Gastrointestinal Principal Modality 1 Fluoroscopy Principal

- Slides: 18

Radiological Category: Gastrointestinal Principal Modality (1): Fluoroscopy Principal Modality (2): None Case Report 703 Submitted by: Craig E Cook, M. D. Faculty reviewer: Agnes Guthrie, M. D. The University of Texas Medical School at Houston Date accepted: 12 April 2010

Case History 27 -year-old radiology resident with difficulty swallowing. Other history withheld.

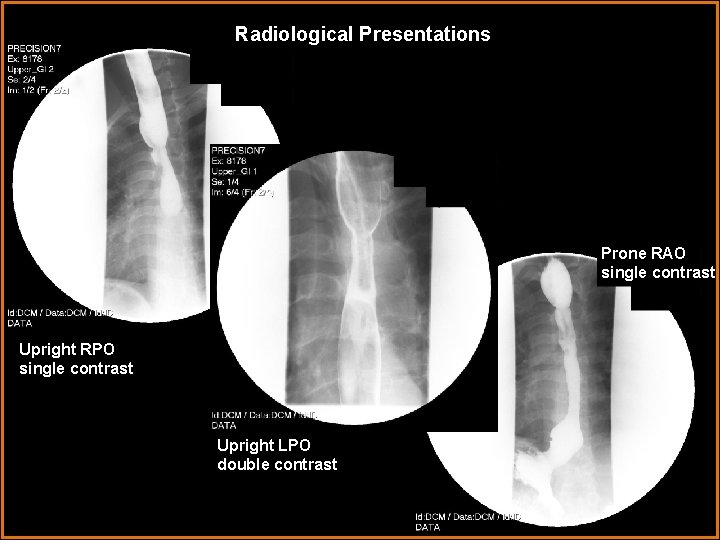

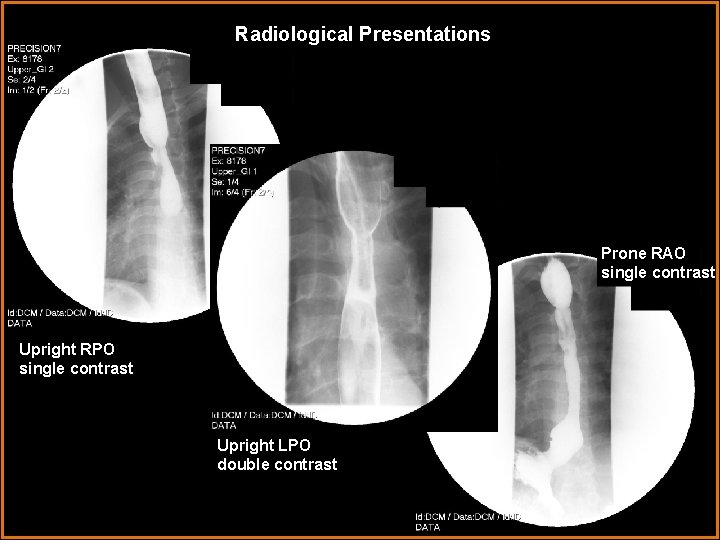

Radiological Presentations Prone RAO single contrast Upright RPO single contrast Upright LPO double contrast

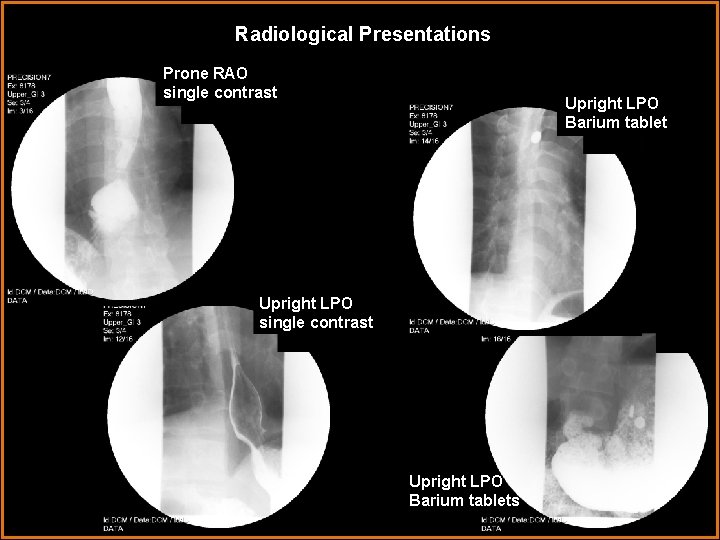

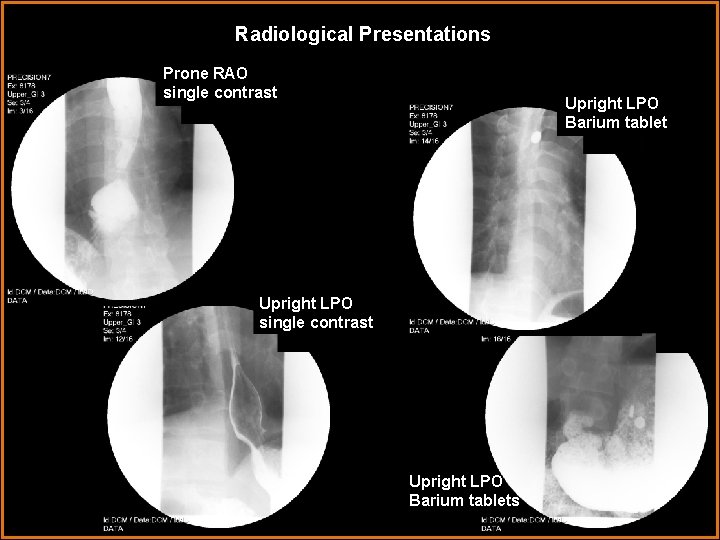

Radiological Presentations Prone RAO single contrast Upright LPO Barium tablet Upright LPO single contrast Upright LPO Barium tablets

Test Your Diagnosis Which one of the following is your choice for the appropriate diagnosis? After your selection, go to next page. • Chronic esophagitis • Chronic gastroesophageal reflux • Prior caustic ingestion • Prior esophageal atresia repair • Prior radiation therapy • Eosinophilic esophagitis

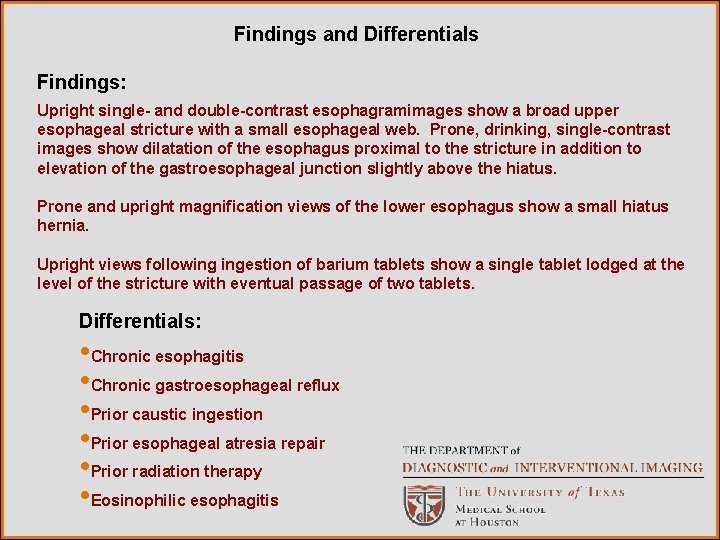

Findings and Differentials Findings: Upright single- and double-contrast esophagramimages show a broad upper esophageal stricture with a small esophageal web. Prone, drinking, single-contrast images show dilatation of the esophagus proximal to the stricture in addition to elevation of the gastroesophageal junction slightly above the hiatus. Prone and upright magnification views of the lower esophagus show a small hiatus hernia. Upright views following ingestion of barium tablets show a single tablet lodged at the level of the stricture with eventual passage of two tablets. Differentials: • Chronic esophagitis • Chronic gastroesophageal reflux • Prior caustic ingestion • Prior esophageal atresia repair • Prior radiation therapy • Eosinophilic esophagitis

Discussion The most common cause of esophageal stricture formation is chronic esophagitis. It may be associated with abnormal esophageal motility. It may also result in formation of strictures or webs and occasionally in segmental or diffuse esophageal narrowing and shortening. The most common cause of chronic esophagitis is gastroesophageal reflux, but other causes include alcohol abuse, motility disorders such as achalasia, eosinophilic esophagitis, and infectious esophagitis, especially in the immunocompromised. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is another common cause of esophageal stricture formation, usually in the lower esophagus. These strictures typically demonstrate concentric, smooth tapering of the esophagus with proximal dilatation. GERD is caused by incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter and is frequently associated with a hiatus hernia. Patients may complain of a burning sensation in the epigastrium and/or chest area, chest pain, a globus sensation, postural regurgitation, and dysphagia or odynophagia. Occasionally, patients with chronic reflux esophagitis do not have symptoms until complications occur. A long-term complication of chronic GERD is distal esophageal metaplasia (Barrett’s esophagus), which is a precursor to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroesophageal reflux can be diagnosed on upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examination but does not imply GERD, as reflux can be seen in 20% of normal individuals on UGI without provocation. The most sensitive method for diagnosing GERD is 24 -hour p. H monitoring.

Discussion Caustic ingestion is usually the result of an accident in the pediatric population or an attempt at suicide in the adult population. Alkaline agents (e. g. liquid lye) cause liquefaction necrosis, often complicated by esophageal ulceration with or without perforation, while acidic agents usually cause more superficial injury. Long-term complications include both strictures, which may be short and irregular or long and filiform, and diverticula. Chronic esophagitis is not a common finding with prior caustic ingestion. Radiation therapy in the chest can cause esophageal strictures if the radiation portal includes the esophagus. Acute changes may simply include ulcer formation, but fibrosis can develop, causing interrupted peristalsis and stricture formation. Stricture formation is more commonly associated with higher radiation doses in the range of 45 -60 Gy and usually occurs at least 4 – 8 months after radiotherapy. These strictures are most commonly found in the upper to mid esophagus and present as broad, smooth tapers within the radiated field. Radiation therapy does not typically cause chronic esophagitis.

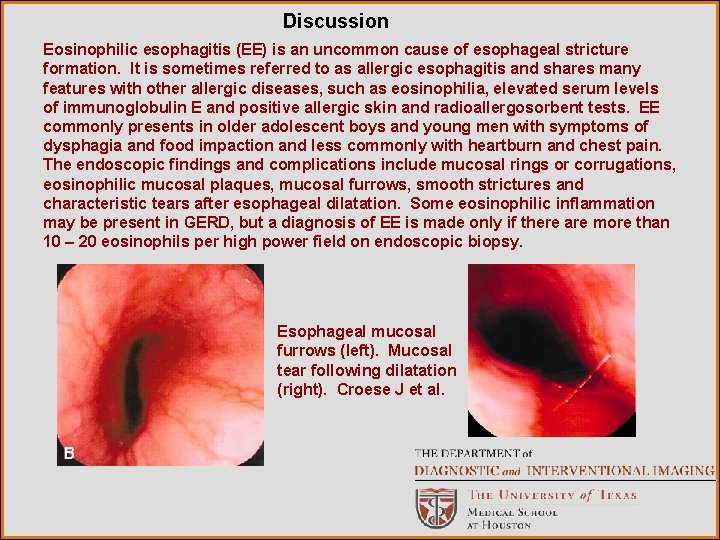

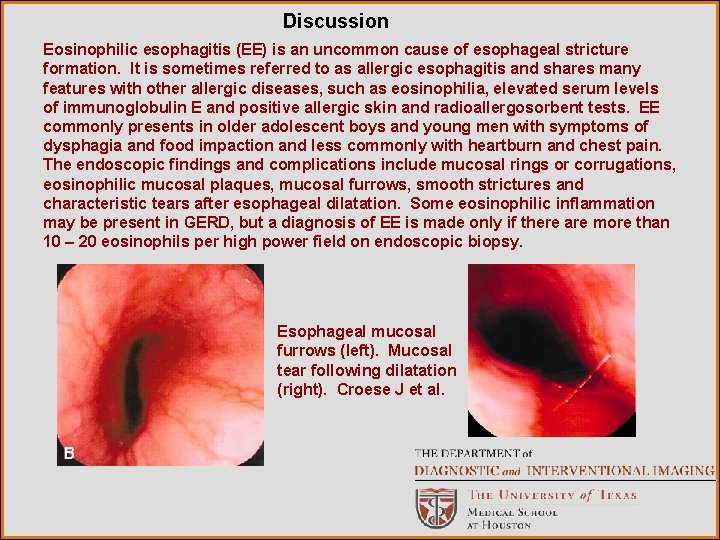

Discussion Eosinophilic esophagitis (EE) is an uncommon cause of esophageal stricture formation. It is sometimes referred to as allergic esophagitis and shares many features with other allergic diseases, such as eosinophilia, elevated serum levels of immunoglobulin E and positive allergic skin and radioallergosorbent tests. EE commonly presents in older adolescent boys and young men with symptoms of dysphagia and food impaction and less commonly with heartburn and chest pain. The endoscopic findings and complications include mucosal rings or corrugations, eosinophilic mucosal plaques, mucosal furrows, smooth strictures and characteristic tears after esophageal dilatation. Some eosinophilic inflammation may be present in GERD, but a diagnosis of EE is made only if there are more than 10 – 20 eosinophils per high power field on endoscopic biopsy. Esophageal mucosal furrows (left). Mucosal tear following dilatation (right). Croese J et al.

Discussion Repair of esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula (EA-TEF) is a less common entity (incidence of 1 in 4, 500 to 1 in 2, 500 live births), but it commonly leads to both mechanical and functional strictures. The mechanical strictures are those caused by excessive scar tissue which narrows the esophageal lumen, while functional strictures result from the lack of muscle in that scar tissue, which precludes peristalsis. This resultant esophageal dysmotility causes another, more common long-term complication of EA-TEF repair—dysphagia, usually for solid foods. In contradistinction to the dysphagia seen in other adults, patients with prior EA-TEF repair have spent their entire lives adapting their swallowing habits to the function of the esophagus to minimize symptoms. The most common and worrisome long-term complication of EA-TEF repair is GERD and the resultant chronic esophagitis. The incidence of GERD ranges from 40 – 70% in pediatric patients. While several investigators have suggested a high incidence of GERD in adults with a history of EA-TEF repair, it is believed to be similar to the normal adult population. However, there is a discrepancy between subjective reflux symptoms and documented GER in these patients, which leaves the lower esophagus exposed to high levels of gastric acid at a subclinical level. This increases the potential for columnar metaplasia in those who are untreated.

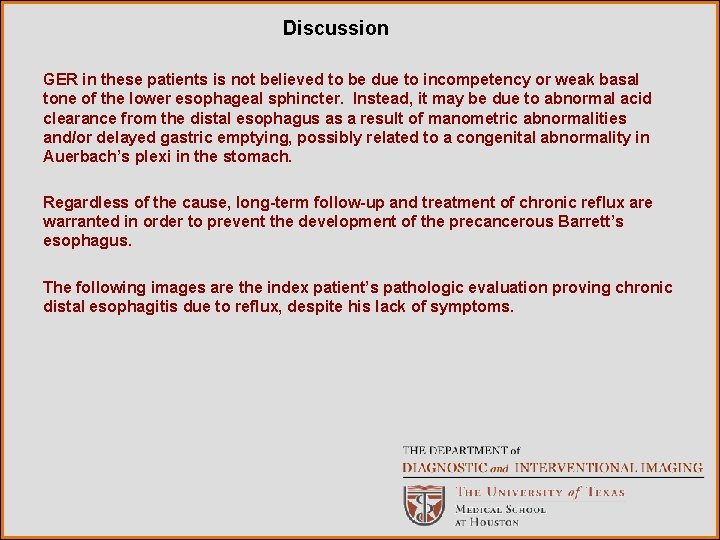

Discussion GER in these patients is not believed to be due to incompetency or weak basal tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. Instead, it may be due to abnormal acid clearance from the distal esophagus as a result of manometric abnormalities and/or delayed gastric emptying, possibly related to a congenital abnormality in Auerbach’s plexi in the stomach. Regardless of the cause, long-term follow-up and treatment of chronic reflux are warranted in order to prevent the development of the precancerous Barrett’s esophagus. The following images are the index patient’s pathologic evaluation proving chronic distal esophagitis due to reflux, despite his lack of symptoms.

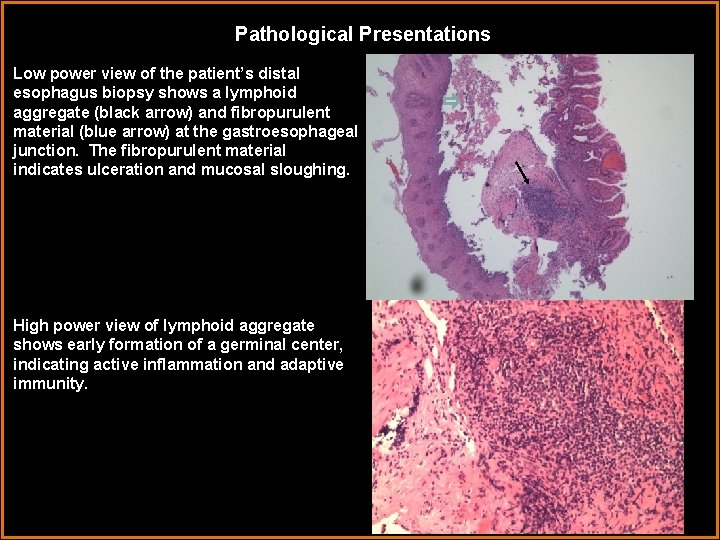

Pathological Presentations Low power view of the patient’s distal esophagus biopsy shows a lymphoid aggregate (black arrow) and fibropurulent material (blue arrow) at the gastroesophageal junction. The fibropurulent material indicates ulceration and mucosal sloughing. High power view of lymphoid aggregate shows early formation of a germinal center, indicating active inflammation and adaptive immunity.

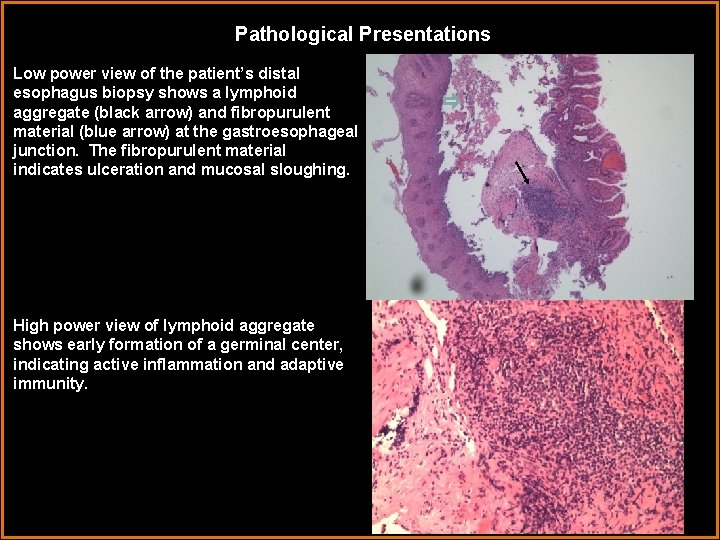

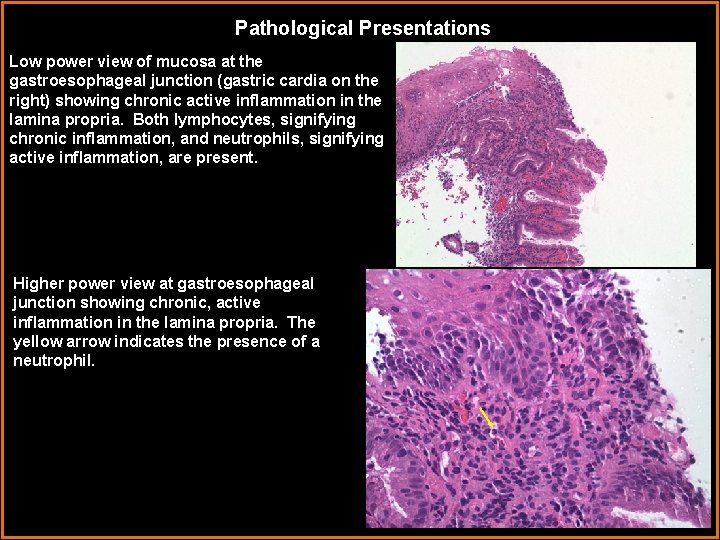

Pathological Presentations Low power view of mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction (gastric cardia on the right) showing chronic active inflammation in the lamina propria. Both lymphocytes, signifying chronic inflammation, and neutrophils, signifying active inflammation, are present. Higher power view at gastroesophageal junction showing chronic, active inflammation in the lamina propria. The yellow arrow indicates the presence of a neutrophil.

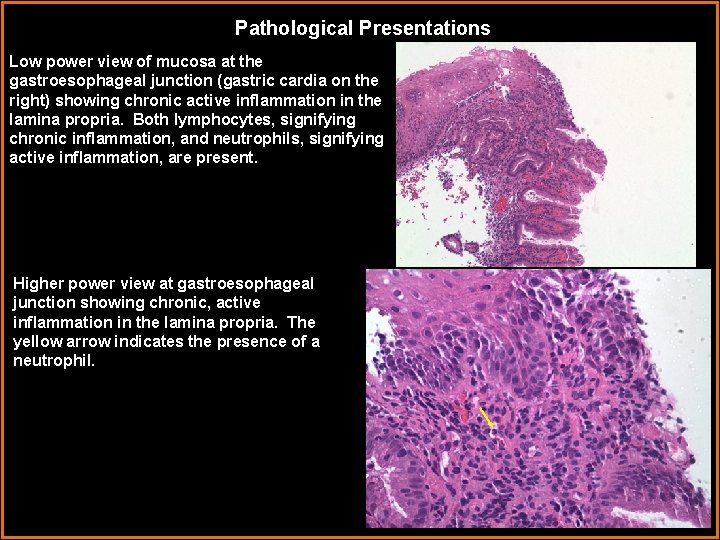

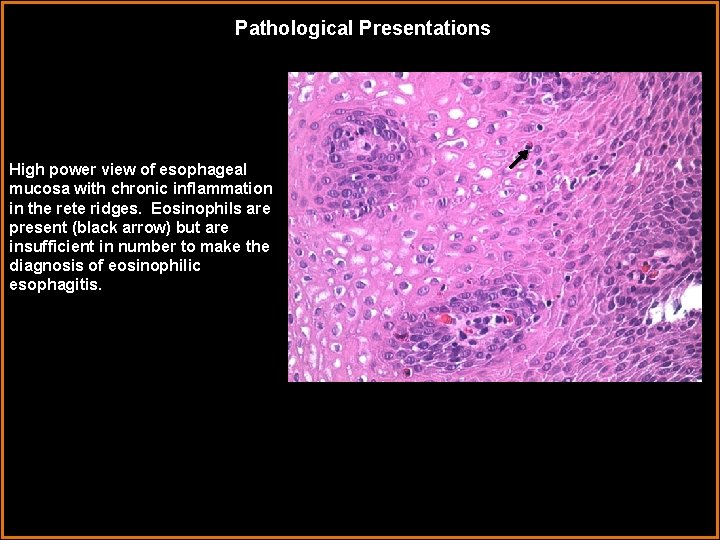

Pathological Presentations High power view of esophageal mucosa with chronic inflammation in the rete ridges. Eosinophils are present (black arrow) but are insufficient in number to make the diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis.

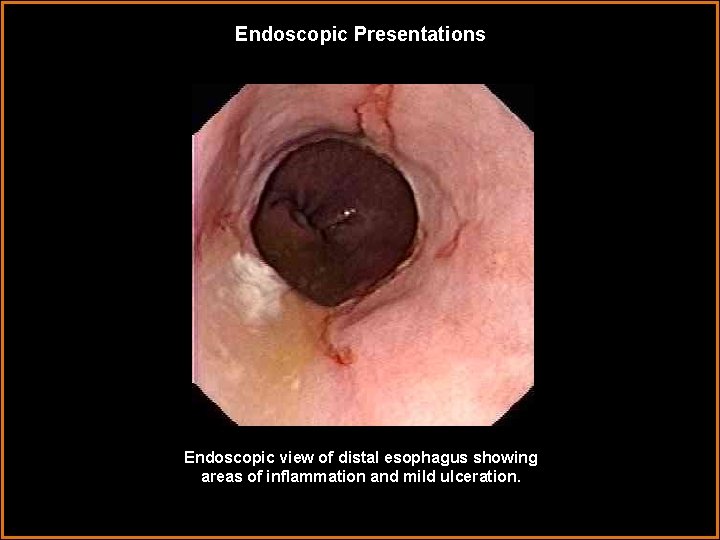

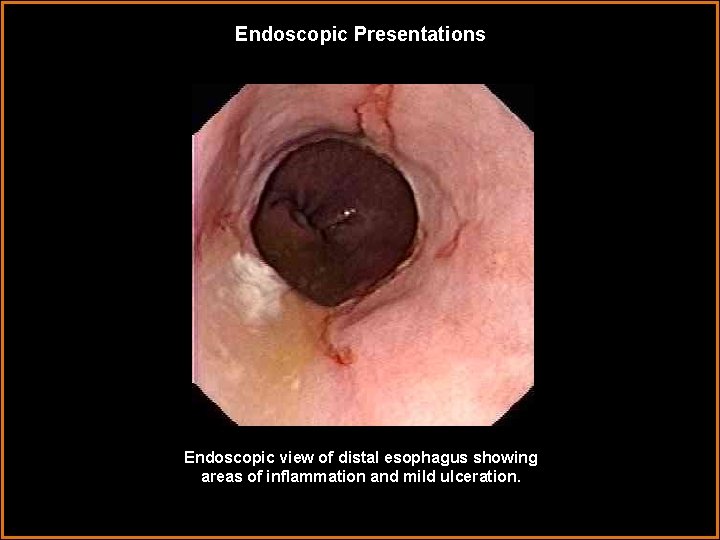

Endoscopic Presentations Endoscopic view of distal esophagus showing areas of inflammation and mild ulceration.

Diagnosis Broad, wide esophageal stricture due to prior esophageal atresia-tracheoesophageal fistula repair with secondary long-term complication of chronic reflux esophagitis.

References Biller JA, Allen JL, Schuster SR, Treves ST, Winter HS. Long-Term Evaluation of Esophageal and Pulmonary Function in Patients with Repaired Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophgeal Fistula. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1987; 37(9): 985 -990. Brant WE. Abdomen and Pelvis. In: Brant WE, Helms CA. Fundamentals of Diagnostic Radiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007: 801 -813. Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, et al. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilicesophagitis in adults. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2003; 58(4): 516 -522. Romeo C, Bonanno N, Baldari S, et al. Gastric Motility Disorders in Patients Operated on for Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula: Long-Term Evaluation. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35(5): 740 -744. Somppi E, Tammela O, Ruuska T, et al. Outcome of Patients Operated on for Esophageal Atresia: 30 Years’ Experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33(9): 1341 -1346.

References Weissleder. R, Wittenberg J, et al. Primer of Diagnostic Imaging. 4 th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007: 162 -168. Stat. Dx Special thanks to Brian D. Stewart, M. D. , for his assistance in obtaining pathologic images and the interpretation thereof.

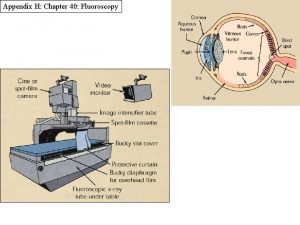

Digital fluoroscopy vs conventional fluoroscopy

Digital fluoroscopy vs conventional fluoroscopy Erate category 1

Erate category 1 Center for devices and radiological health

Center for devices and radiological health National radiological emergency preparedness conference

National radiological emergency preparedness conference Radiological dispersal device

Radiological dispersal device Tennessee division of radiological health

Tennessee division of radiological health Carm fluoroscopy

Carm fluoroscopy Real time fluoroscopy

Real time fluoroscopy Bronchoscopy fluoroscopy

Bronchoscopy fluoroscopy Spot film fluoroscopy

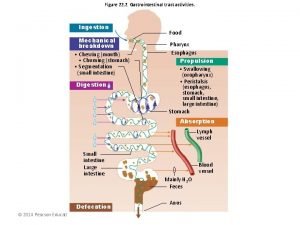

Spot film fluoroscopy Sistema digestorio

Sistema digestorio Gastrointestinal medical terminology breakdown

Gastrointestinal medical terminology breakdown Pneumatic reduction of intussusception

Pneumatic reduction of intussusception Motilidad gastrointestinal

Motilidad gastrointestinal Emt chapter 18 gastrointestinal and urologic emergencies

Emt chapter 18 gastrointestinal and urologic emergencies Dr sigit djuniawan

Dr sigit djuniawan Peristalsis and segmentation

Peristalsis and segmentation Ashraf radwan

Ashraf radwan Nutrition focused physical findings

Nutrition focused physical findings