Politeness and Solidarity When we speak we have

![• Brown and Levinson (1987) provide the definition of FACE “[it is] the • Brown and Levinson (1987) provide the definition of FACE “[it is] the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/d746c12dc4aca933e3c1947dd8904f55/image-30.jpg)

- Slides: 34

Politeness and Solidarity When we speak we have to make choices of many different kinds: what to say, when to say it, how to say it. How we say something is as important as what we say – Content and form are inseparable Some linguistic choices indicate the social relationship between speaker and listener.

Tu & Vous 1 Many languages have a distinction corresponding to the tu–vous (T/V) distinction in French, where grammatically there is a ‘singular you’ tu (T) and a ‘plural you’ vous (V) but usage requires that you use vous with individuals on certain occasions.

Tu & Vous 2 The T form is sometimes described as the ‘familiar’ form and the V form as the ‘polite’ one. The T/V distinction began as a genuine difference between singular and plural

Tu & Vous 3 In the 4 th century: the use of plural vous was to address the emperor. There were two emperors: one in the east Constantinople and another in the west Rome, but the Empire was administratively unified. By addressing one, you were in fact addressing both emperors. The choice of vous as a form of address may have been in response to this implicit plurality.

Tu & Vous 4 An emperor is also plural in another sense; he is the summation of his people and can speak as their representative. Royal persons sometimes say ‘we’ where an ordinary man would say ‘I. ’

Asymmetrical VS Symmetrical T/V Usage 1 The consequence of this usage was that by medieval times the upper classes apparently began to use V forms with each other to show mutual respect and politeness. However, T forms persisted, so that the upper classes used mutual V, the lower classes used mutual T, and the upper classes addressed the lower classes with T but received V.

Asymmetrical VS Symmetrical T/V Usage 2 Asymmetrical T/V usage therefore came to symbolize a power relationship. It was extended to such situations as people to animals, master or mistress to servants, parents to children, priest to penitent, officer to soldier, and even God to angels, with, in each case, the first mentioned giving T but receiving V.

Asymmetrical VS Symmetrical T/V Usage 3 Symmetrical V usage became ‘polite’ usage. This polite usage spread downward in society, but not all the way down, so that in certain classes, but never the lowest, it became expected between husband wife, parents and children, and lovers. Symmetrical T usage was always available to show intimacy, and its use for that purpose also spread to situations in which two people agreed they had strong common interests, i. e. , a feeling of solidarity.

Asymmetrical VS Symmetrical T/V Usage 4 The mutual T for solidarity gradually came to replace the mutual V of politeness, since solidarity is often more important than politeness in personal relationships. Moreover, the use of the asymmetrical T/V to express power decreased and mutual V was often used in its place, as between officer and soldier. Today we can still find asymmetrical T/V uses, but solidarity has tended to replace power, so that now mutual T is found quite often in relationships which previously had asymmetrical usage, e. g. , father and son, and employer and employee.

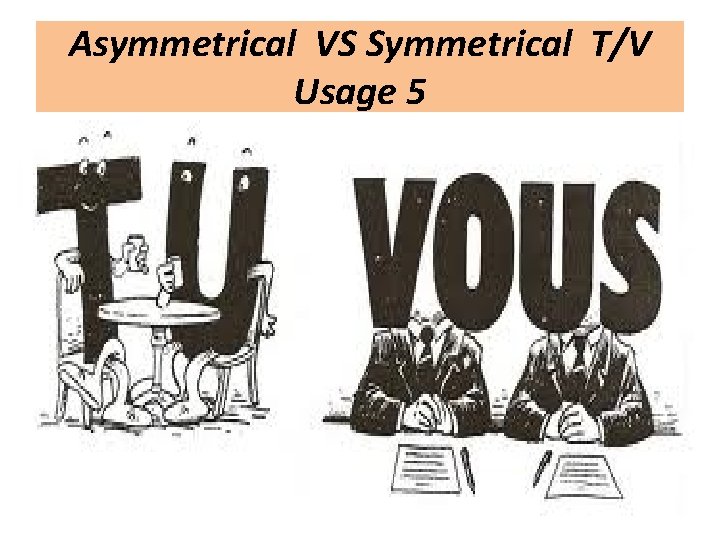

Asymmetrical VS Symmetrical T/V Usage 5

Does English have active T/V distinction? English, has no active T/V distinction. The use of T forms by such groups as Quakers (members of a group of religious Christian movements which is known as the Religious Society of Friends in Europe, Australia, New Zealand parts of North America) is very much limited, but these T forms are a solidarity marker for those who do use them. The T/V use that remains in English is archaic, found in fixed formulas such as prayers or in use in plays written during the era when the T/V distinction was alive or in modern works that try to recapture aspects of that era.

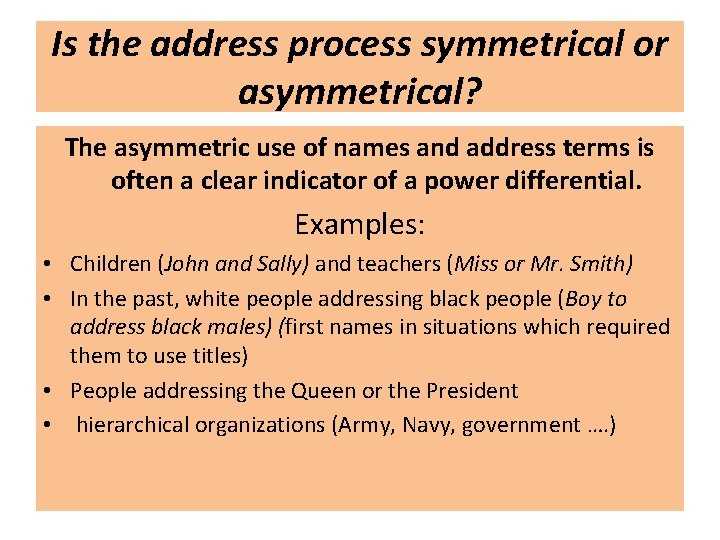

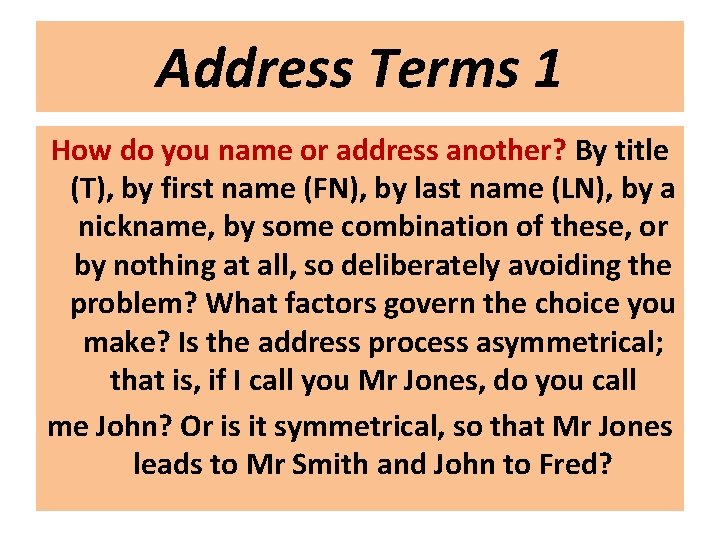

Address Terms 1 How do you name or address another? By title (T), by first name (FN), by last name (LN), by a nickname, by some combination of these, or by nothing at all, so deliberately avoiding the problem? What factors govern the choice you make? Is the address process asymmetrical; that is, if I call you Mr Jones, do you call me John? Or is it symmetrical, so that Mr Jones leads to Mr Smith and John to Fred?

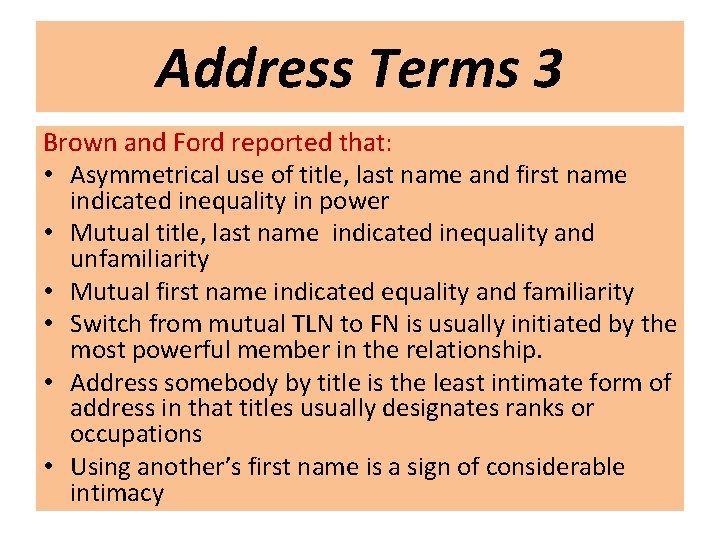

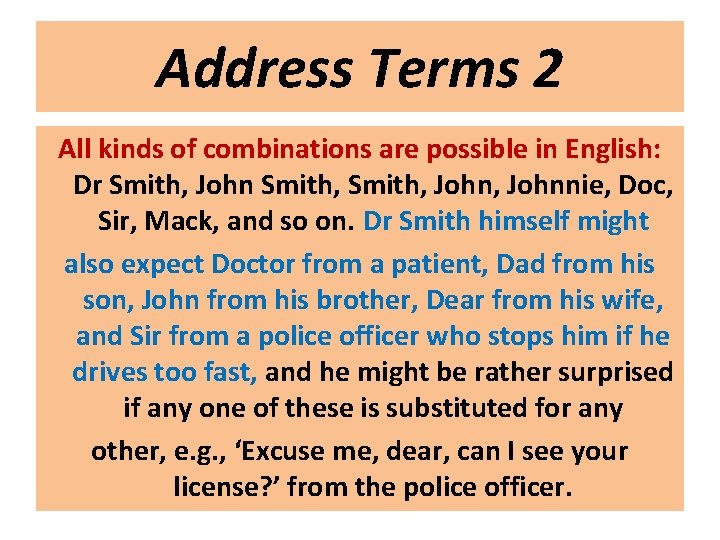

Address Terms 2 All kinds of combinations are possible in English: Dr Smith, John, Johnnie, Doc, Sir, Mack, and so on. Dr Smith himself might also expect Doctor from a patient, Dad from his son, John from his brother, Dear from his wife, and Sir from a police officer who stops him if he drives too fast, and he might be rather surprised if any one of these is substituted for any other, e. g. , ‘Excuse me, dear, can I see your license? ’ from the police officer.

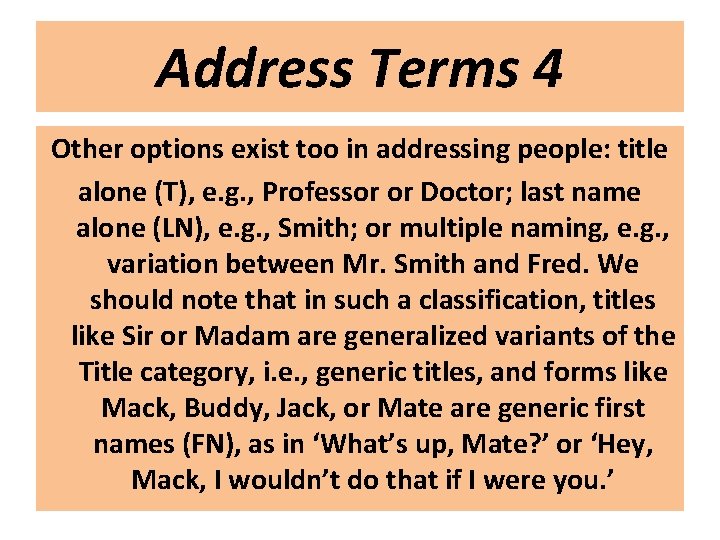

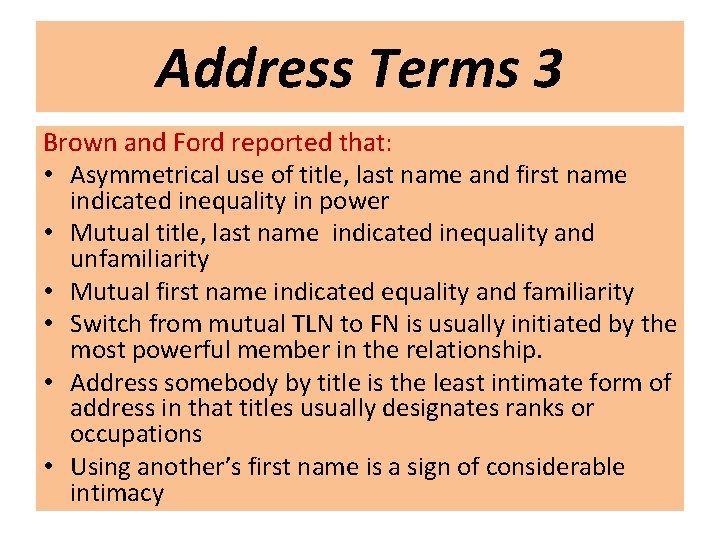

Address Terms 3 Brown and Ford reported that: • Asymmetrical use of title, last name and first name indicated inequality in power • Mutual title, last name indicated inequality and unfamiliarity • Mutual first name indicated equality and familiarity • Switch from mutual TLN to FN is usually initiated by the most powerful member in the relationship. • Address somebody by title is the least intimate form of address in that titles usually designates ranks or occupations • Using another’s first name is a sign of considerable intimacy

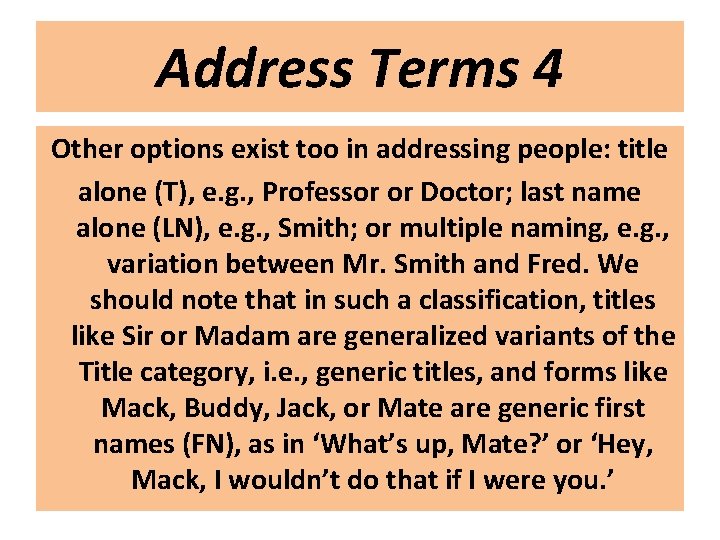

Address Terms 4 Other options exist too in addressing people: title alone (T), e. g. , Professor or Doctor; last name alone (LN), e. g. , Smith; or multiple naming, e. g. , variation between Mr. Smith and Fred. We should note that in such a classification, titles like Sir or Madam are generalized variants of the Title category, i. e. , generic titles, and forms like Mack, Buddy, Jack, or Mate are generic first names (FN), as in ‘What’s up, Mate? ’ or ‘Hey, Mack, I wouldn’t do that if I were you. ’

Is the address process symmetrical or asymmetrical? The asymmetric use of names and address terms is often a clear indicator of a power differential. Examples: • Children (John and Sally) and teachers (Miss or Mr. Smith) • In the past, white people addressing black people (Boy to address black males) (first names in situations which required them to use titles) • People addressing the Queen or the President • hierarchical organizations (Army, Navy, government …. )

Address Terms 5 • In each country there are different rules stating how people should address each other. In England we can omit the address term when greeting someone but in France that avoidance could be impolite. • As your family relationships change, issues of naming and addressing may arise; for example: how do you address your father/mother in law?

Address Terms 6 • Finally, an additional peculiarity is that people sometimes give names to, and address, non – human as well as humans, for example: how do you address your pets, if you have? And how do you address your kids or kids in general?

Politeness ‘I’ll have an iced mocha’, my New York friend, Ellen, said. ‘An iced mocha’, repeated the server. ‘Do you want whipped cream on that? ’ ‘You have to ask? ’ said Ellen.

Clearly the server at the Michigan restaurant where this exchange took place found Ellen’s reply, ‘You have to ask? ’ and her ironic tone of voice, somewhat hard to interpret. Do you agree? If you know that there was a long pause while she looked at Ellen waiting for her to say something more.

Commentary Outside of New York, Ellen’s answer didn’t have the meaning of an enthusiastic ‘yes’ that it was intended to have. In Michigan, it seems waiting staff don’t expect the kind of ironic jokes from strangers that you might find in talk between close friends.

Question Was it polite for Ellen to say ‘You have to ask? ’ like that? The answer probably depends on where somebody grew up and what norms of politeness s/he acquired there.

In many places, a reply like this would be considered terribly rude, and something like ‘Yes, please’ or ‘Yes, thank you’ would be expected. But by the standards of where Ellen grew up, she was being polite. By making a joke – moreover, a joke that suggests that the answer to her question is already shared knowledge between the speaker and the hearer – she was working to construct the business exchange in more friendly and intimate terms.

Some languages have different words for the same thing that have to be chosen depending on what the politeness and respect relationship is between the speakers. In Japanese, the form of some verbs, including the verb ‘to eat’ changes entirely. Japanese requires speakers to make such decisions about what verb form to use, and what kind of suffixes to attach to verbs and nouns in everyday speech. Showing this kind of attention to each other and evaluating your relationship with your interlocutors in a particular place or at a particular time is, in a very general sense, what it means to be polite.

Question……? Does English have speech levels or special respectful vocabulary to the same extent that Japanese does?

Answer…… English doesn’t have speech levels or special respectful vocabulary to the same extent that Japanese does. However, it does have some areas of the vocabulary where euphemisms or avoidance strategies are used according to where people are or who they are talking to.

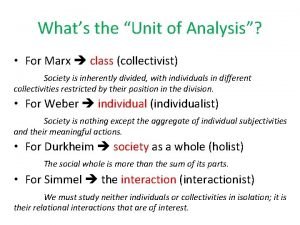

What is politeness? Politeness is socially prescribed, we adjust to others in social relationships in ways society deems appropriate It refers to the actions taken by competent speakers in a community in order to attend to possible social or interpersonal disturbance

Types of politeness There are two kinds of politeness: • POSITIVE: we try to achieve solidarity and treat others as friends. We do not impose and never threaten their face. Example: symmetrical pronominal use • NEGATIVE: it leads to deference, indirectness and formality in language use. Example: Asymmetric T/V use

• Goffman (1955) states that when communicating “we present a FACE to others and to others’ faces. ” • In every social interaction we are obliged to protect both our own face and the face of others. • We play out a kind of ritual in which each party is required to recognize the identity the other presents or claims. • There is no faceless communication.

![Brown and Levinson 1987 provide the definition of FACE it is the • Brown and Levinson (1987) provide the definition of FACE “[it is] the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/d746c12dc4aca933e3c1947dd8904f55/image-30.jpg)

• Brown and Levinson (1987) provide the definition of FACE “[it is] the public self-image that every member wants to claim for himself” They make a distinction between: • POSITIVE FACE: it is the desire to gain the approval of others, the positive consistent self- image or personality. It looks to SOLIDARITY • NEGATIVE FACE: it is the desire to be unimpeded by others’ actions; a claim for freedom of action and from imposition.

• Each interaction is a FACE WORK and the goal is the maintenance of as much of each individual’s positive face as possible. • Pinker (2007) argues that “politeness theory is a good start, but not enough [because] it assumes that the speaker and the hearer are working in perfect harmony, each trying to save each other’s face”

Solidarity strategy in pragmatics

Solidarity strategy in pragmatics Organic solidarity

Organic solidarity Speech without preparation

Speech without preparation High considerateness style

High considerateness style What does this symbol mean

What does this symbol mean Falling tone and rising tone examples

Falling tone and rising tone examples Labor and solidarity day ne demek

Labor and solidarity day ne demek Brown and levinson

Brown and levinson Politeness theory in communication

Politeness theory in communication Spanish politeness

Spanish politeness Negative politeness examples

Negative politeness examples Negative politeness examples

Negative politeness examples Spanish politeness

Spanish politeness Politeness is to human nature what warmth is to wax

Politeness is to human nature what warmth is to wax Politeness principle

Politeness principle Face-threatening

Face-threatening Social solidarity meaning

Social solidarity meaning Mechanical solidarity

Mechanical solidarity Mechanical solidarity definition sociology

Mechanical solidarity definition sociology Criticisms of conflict theory

Criticisms of conflict theory Functionalism looks at

Functionalism looks at Status scale in sociolinguistics

Status scale in sociolinguistics Definiton justice

Definiton justice Solidarity meaning

Solidarity meaning Mechanical solidarity

Mechanical solidarity Economic groupings

Economic groupings Solidarity meaning

Solidarity meaning Solidarity tax credit eligibility

Solidarity tax credit eligibility 6 square faces and 8 vertices

6 square faces and 8 vertices Words have meaning and names have power

Words have meaning and names have power Dangerous curves the zoo

Dangerous curves the zoo What is a echinoderm

What is a echinoderm Keep calm and speak english

Keep calm and speak english Dollar diplomacy definition us history

Dollar diplomacy definition us history To approach and speak to first

To approach and speak to first