Philosophy of Law Hart and American Legal Realism

![Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1932] AC 161 • Court ruled that a mutual Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1932] AC 161 • Court ruled that a mutual](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-18.jpg)

![cf. , Solle v Butcher [1950] 1 KB 671 • S leased an apartment cf. , Solle v Butcher [1950] 1 KB 671 • S leased an apartment](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-20.jpg)

![And [H]owever smoothly they work over the great mass of ordinary cases, [they will], And [H]owever smoothly they work over the great mass of ordinary cases, [they will],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-37.jpg)

- Slides: 48

Philosophy of Law Hart, and American Legal Realism Phil 217/337

American Legal Realism • American Legal Movement early 20 C. –Reacting against formalism or mechanical jurisprudence. –Where formalism = the idea that the law determined the outcome to cases.

Target: • Christopher Columbus Langdell Dean, Harvard Law School 1870 -1895. • Invented the case method. • Students to deduce legal principles from cases and draw the deductively right conclusions by applying these principles to facts

Langdell’s Theoretical Assumptions • The process of applying principles to the facts was deductive • Judges were bound by the law to give certain ‘right’ answers to given facts. “Law, considered as a science, consists of certain principles or doctrines. To have such a mastery of these as to be able to apply them with constant facility and certainty to the ever-tangled skein of human affairs, is what constitutes a true lawyer…” Langdell, A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts, 1871, emphasis added

“The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nations development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics. ” Holmes, The Common Law, 1881

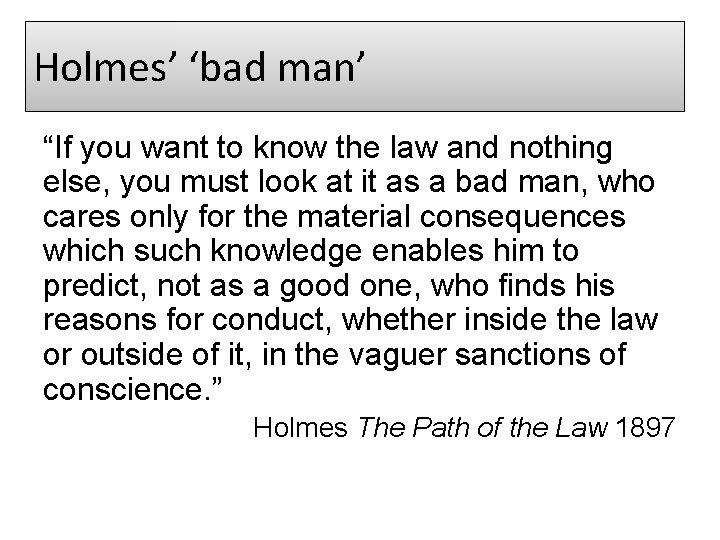

Was/Is legal realism a theory of law? “Take the fundamental question, ‘What constitutes the law? ’ You will find some text writers telling you that it is something different from what is decided by the courts of Massachusetts or England, that it is a system of reason, that it is a deduction from principles of ethics or admitted axioms or what not, which may or may not coincide with the decisions. But if we take the view of our friend the bad man we shall find that he does not care two straws for the axioms or deductions, but that he does want to know what the Massachusetts or English courts are likely to do in fact. I am much of his mind. The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law. ” Holmes, The Path of the Law 1897

Holmes’ ‘bad man’ “If you want to know the law and nothing else, you must look at it as a bad man, who cares only for the material consequences which such knowledge enables him to predict, not as a good one, who finds his reasons for conduct, whether inside the law or outside of it, in the vaguer sanctions of conscience. ” Holmes The Path of the Law 1897

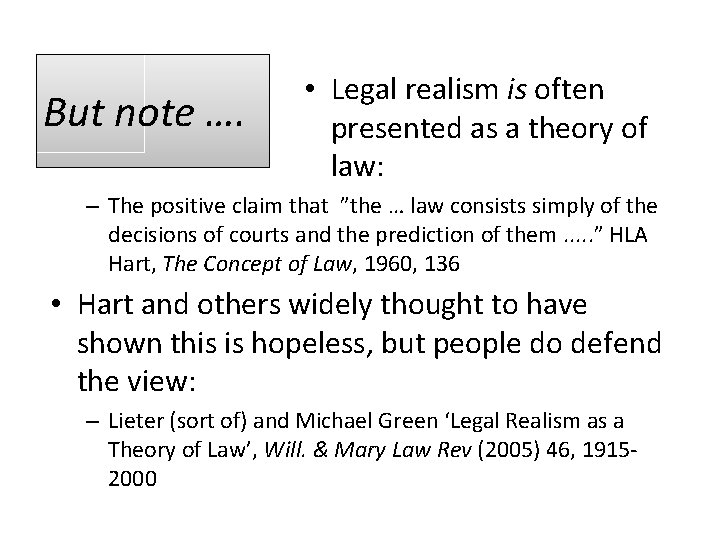

But note …. • Legal realism is often presented as a theory of law: – The positive claim that ”the … law consists simply of the decisions of courts and the prediction of them. . . ” HLA Hart, The Concept of Law, 1960, 136 • Hart and others widely thought to have shown this is hopeless, but people do defend the view: – Lieter (sort of) and Michael Green ‘Legal Realism as a Theory of Law’, Will. & Mary Law Rev (2005) 46, 19152000

Hart’s critique of the realist theory of law On Hart’s account, realists offered a ”predictive theory" of law: Law = a prediction of what the court will do. But according to the predictive theory: – a judge who sets out to discover the "law" on some issue is really just trying to discover what she will do, since the "law" is equivalent to a prediction of what she will do. – It seems impossible for a judge to have been mistaken about the law: she did what she did.

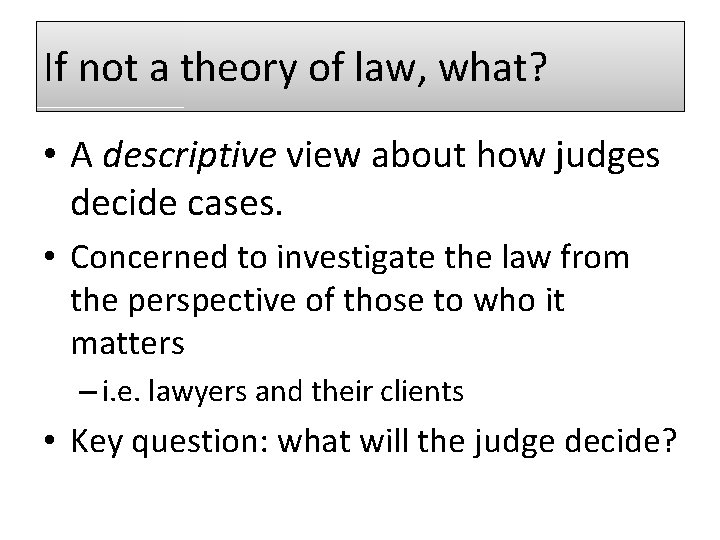

If not a theory of law, what? • A descriptive view about how judges decide cases. • Concerned to investigate the law from the perspective of those to who it matters – i. e. lawyers and their clients • Key question: what will the judge decide?

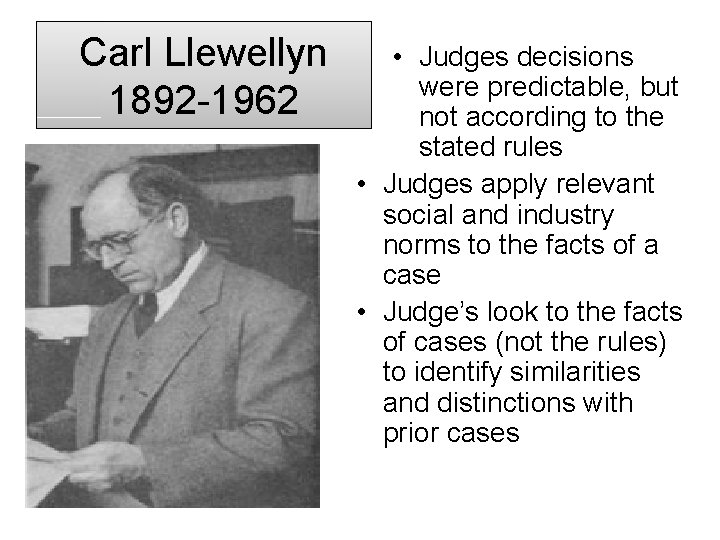

20 th Century Realism • Influenced by the rise of the social sciences in the 1930 s “… the Realists …came out of the intellectual culture of the 1920 s and 1930 s in the United States, a culture firmly in the grips of … a world-view which considered natural science the paradigm of all genuine knowledge, distinguished by its methods of observation and empirical testing, and in which the social sciences aimed to emulate the natural sciences' methods and successes. ” Brian Leiter ‘Rethinking Legal Realism: Toward a Naturalized Jurisprudence’, (1997 -1998) 76 Tex. L. Rev. 267, 271 -272

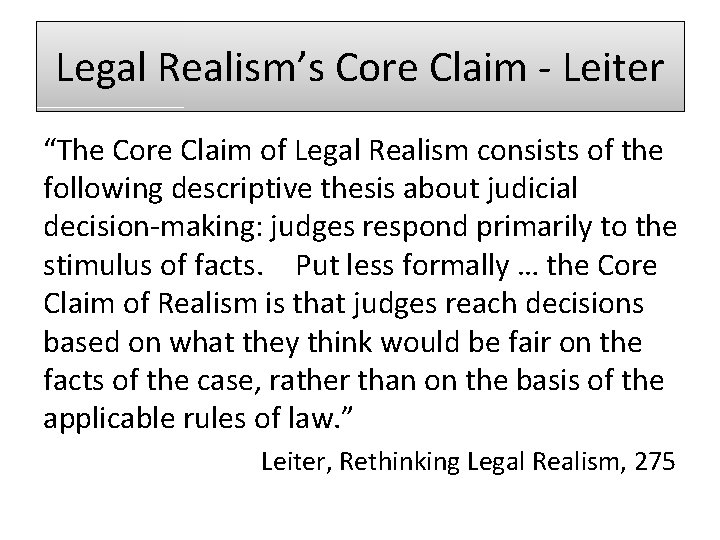

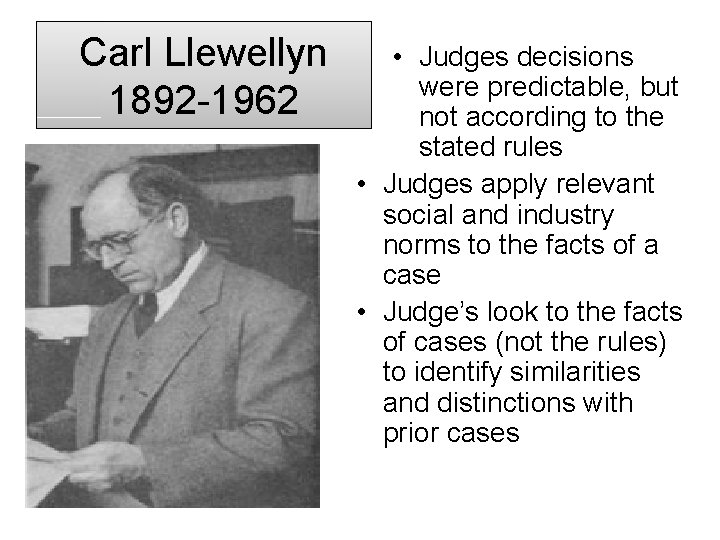

Carl Llewellyn 1892 -1962 • Judges decisions were predictable, but not according to the stated rules • Judges apply relevant social and industry norms to the facts of a case • Judge’s look to the facts of cases (not the rules) to identify similarities and distinctions with prior cases

Legal Realism’s Core Claim - Leiter “The Core Claim of Legal Realism consists of the following descriptive thesis about judicial decision-making: judges respond primarily to the stimulus of facts. Put less formally … the Core Claim of Realism is that judges reach decisions based on what they think would be fair on the facts of the case, rather than on the basis of the applicable rules of law. ” Leiter, Rethinking Legal Realism, 275

Indeterminacy of law § Due to language… § More importantly due to the availability of conflicting rules and principles in both common-law and statute • Legal doctrine inevitably contained conflicting rules which gave judges a choice between inconsistent rules in their determination of cases.

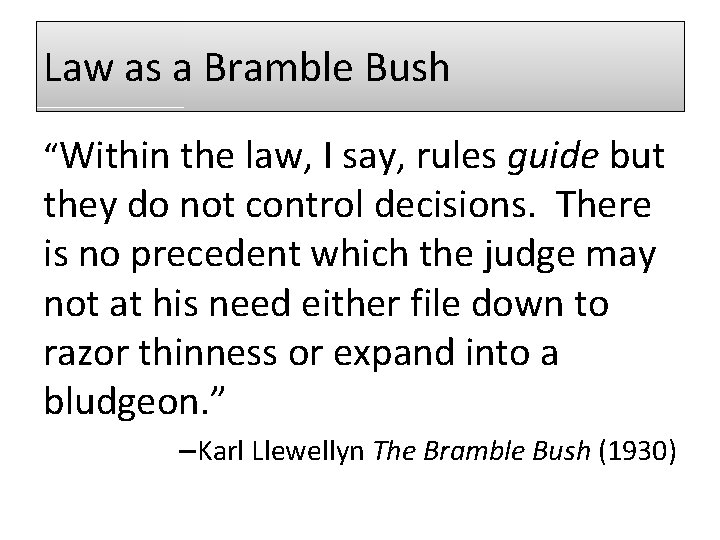

Law as a Bramble Bush “Within the law, I say, rules guide but they do not control decisions. There is no precedent which the judge may not at his need either file down to razor thinness or expand into a bludgeon. ” – Karl Llewellyn The Bramble Bush (1930)

And … “… if there is available a competing but equally authoritative premise that leads to a different conclusion there is a choice in the case; a choice to be justified; a choice which can be justified only as a question of policy - for the authoritative tradition speaks with a forked tongue. ” Llewellyn, ‘Some Realism about Realism’ 44 Harvard Law Review (1931) 1222 -1264, 1252

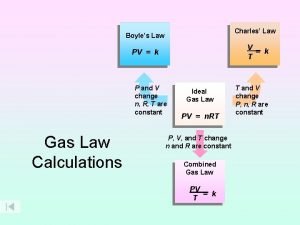

An illustration? • Lever Bros wanted to get rid of two senior managers, Bell and Snelling. Negotiated ‘exit contracts’ of £ 30 K and £ 20 K (1929). • Then discovered they had been trading on their own account: could have sacked them for nothing. • Tried to rescind the contracts • But ….

![Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd 1932 AC 161 Court ruled that a mutual Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1932] AC 161 • Court ruled that a mutual](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-18.jpg)

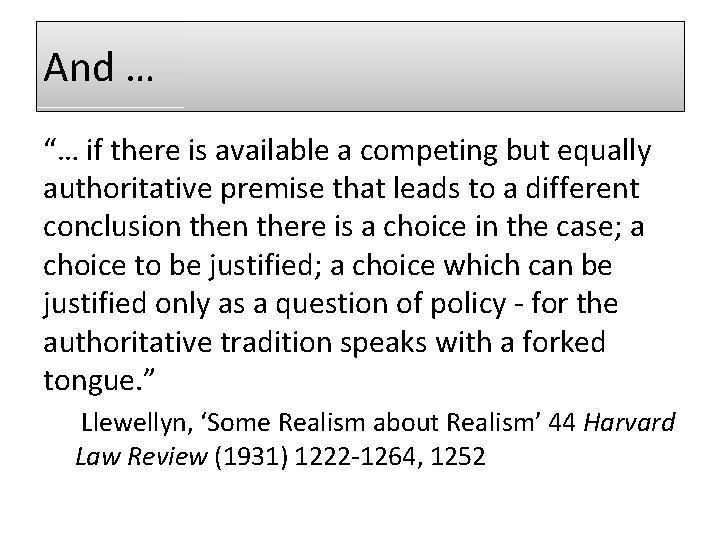

Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1932] AC 161 • Court ruled that a mutual mistake only allowed rescission where it undercut the consent of the parties – where they didn’t get what they’d bargained for. • Here, though what Lever Bros got – the retirement of Bell and Snelling – was worth much less than they’d paid for it, it was exactly what they’d been bargaining for. • No remedy for a mistake about the quality or value of the contract goods.

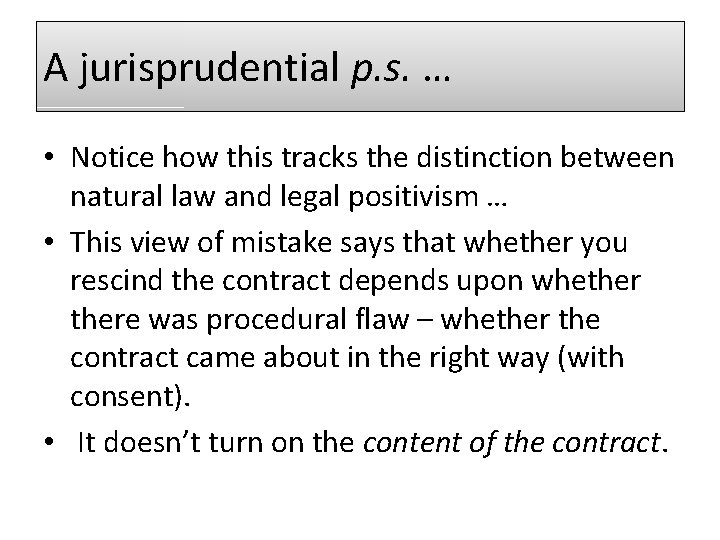

A jurisprudential p. s. … • Notice how this tracks the distinction between natural law and legal positivism … • This view of mistake says that whether you rescind the contract depends upon whethere was procedural flaw – whether the contract came about in the right way (with consent). • It doesn’t turn on the content of the contract.

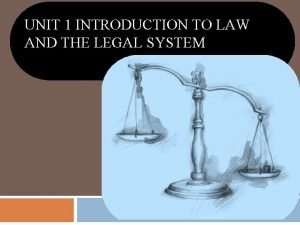

![cf Solle v Butcher 1950 1 KB 671 S leased an apartment cf. , Solle v Butcher [1950] 1 KB 671 • S leased an apartment](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-20.jpg)

cf. , Solle v Butcher [1950] 1 KB 671 • S leased an apartment from B. • Both believed the apartment to be exempt from rent-control legislation, and the rent was fixed accordingly. • Upon discovering the apartment was not exempt, S sued to recover the difference between the actual and the controlled rent. • B counter-claimed that the lease was void for mistake. The point of the counter-claim was to destroy the contractual-tenancy from which a controlled-tenancy might spring.

Solle v Butcher. . . • Denning LJ found that there was no mistake which would void the contract under common law: though both mistakenly thought the tenancy was exempt from the rent-control legislation, "[t]he parties agreed on the same terms on the same subject matter. " • But …. .

Solle v Butcher … “Whilst presupposing that a contract was good at law. . . the court of equity would often relieve a party from the consequences of his own mistake, so long as it could do so without injustice to third parties. The court it was said, had power to set aside the contract whenever it was of the opinion that it was unconscientious for the other party to avail himself of the legal advantage he had obtained”. [1950] 1 KB 671 (CA)692 -693

Follow-up jurisprudential p. s. … • Solle v Butcher appears to take a contentdependent approach to mistake: whether the court will give a remedy depends upon whether the content of the contract, what the parties bargained for, is such that it would be unfair to hold them to the bargain.

Back to realism …. • Suppose you’re a lawyer considering bring a case in mutual mistake in the mid -1960 s, when (let’s suppose) both Bell v Lever and Solle v Butcher are part of the law. • You might tell your client there are two apparently inconsistent lines of authority.

Perhaps a bit quick? • Denning did go on to give a list of features that would bring a case within the equitable jurisdiction …. – “even Lord Denning did not propose that a known unilateral mistake of fact would be remedied by equity—although it may not be safe to assume that, had he addressed this issue, he would have rejected an equitable jurisdiction for such a case!”

Still … • If a judge can choose whether to dispose of a plea of contractual mistake by appeal to the content-dependent or to the content-independent version of the doctrine of mistake, it seems that we must concede at least that the outcome of the case is under-determined by the legal rules. • If the choice is not determined by rules, then the outcome to the case is not determined by rules. We must look for some other explanation, and this other thing will explain the decision - the case will be explained by whatever it is that leads a judge to decide to go for one rule rather than the other

Hart on adjudication “Formalism and rule-scepticism are the Scylla and Charybdis of juristic theory; they are the great exagerations, salutary where they correct each other, and the truth lies between them”. (Hart, Cof. L. , p. 144) • “Legal theory… is apt either to ignore or to exagerate the indeterminacies of legal rules”. (Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 127)

Hart so far … All legal systems consist of 1. a master rule of recognition which underlies and unifies the legal system by specifying criteria for validity which all the other laws of the system must meet and 2. all those rules which do meet the requirements for validity set out in the master rule of recognition.

That’s it … • Nothing other counts as the law. • Pace natural lawyers, there’s no 'law beyond human law’. • The law just is that determinate and limited set of rules which satisfy the rule of recognition, and legal rights, duties, powers and so specified by those rules. • So … it’s important we know what the rules require.

The temptations of formalism? • It might seem that this view would lead one to a formalist theory of law: – Remember … the idea that the legal rules determine the outcome of case. • Hart thinks law is a (complicated) model of rules: – Why not embrace formalism?

Hart rejects formalism (or mechanical jurisprudence) • Argues that judicial discretion is both: – Necessary and – Desirable

The argument from necessity Begins with contrast between two methods of communicating general standards of behaviour. 1. By example An example is provided by some general verbal directions, such as, ‘Do as I do’, and the person being instructed is left to infer what is required. Hart argues that the example method “may leave open ranges of possibilities, and hence doubt, as to what is intended, even as to matters which the person seeking to communicate has himself clearly envisaged” (CL, p. 122).

… two methods 2. By 'explicit forms of language’ Transforming the example into a verbal rule, such as, ‘Every man must take off his hat on entering a church’, might seem to fix the interpretative problem generated by examples. Now the citizen just has to "'subsume' particular facts under general classificatory heads and draw a simple syllogistic conclusion” (CL, p. 122).

But … • • Hart argues that general rules don’t solve the problems of guidance by example. When the rule, "No vehicles in the park” is enacted both the legislators, and the public have in mind particular problems, and situations that are to be brought about or avoided.

“No Vehicles Allowed in the Park” • We might begin by thinking, "If anything is a vehicle a motor-car is one” (CL, p. 123). • In deciding whether, for the purpose of the rule, the word "vehicle” applies to roller-skates or toy cars, one would "consider. . . whether the present case resembles the plain case 'sufficiently’ in 'relevant’ respects”. • “Like a motorcar, roller skates make noise (but not nearly as much) and they threaten safety and order (though the threat is on a much lower scale). Further dissimilarities include the facts that roller skates are far smaller than motorcars, and that they do not pollute the air. There are both similarities and dissimilarities; some criteria are fulfilled, others are not”.

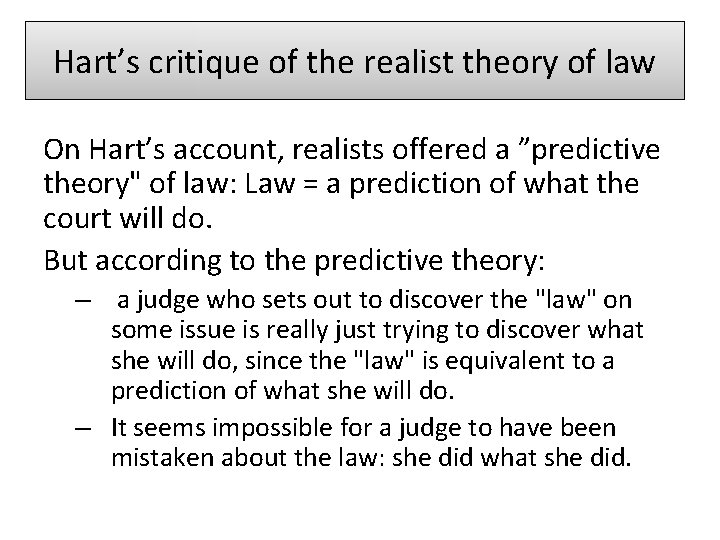

The Open–Texture of Language • In all fields of experience, not only that of rules, there is a limit, inherent in the nature of language, to the guidance which general language can provide. There will indeed be plain cases constantly recurring in similar contexts to which general expressions are clearly applicable. . . where there is general agreement in judgments as to the applicability of the general terms. . . but there will also be cases where it is not clear whether they apply or not. • (CL, p. 123)

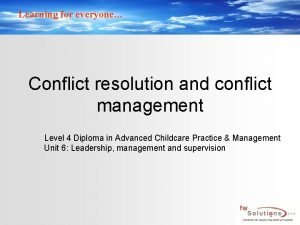

![And However smoothly they work over the great mass of ordinary cases they will And [H]owever smoothly they work over the great mass of ordinary cases, [they will],](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/102452ec8d2acc1c517df27e3a0ce205/image-37.jpg)

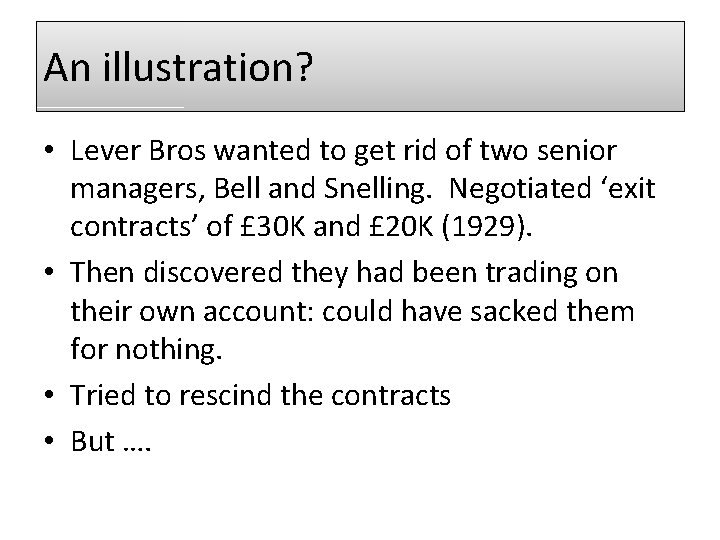

And [H]owever smoothly they work over the great mass of ordinary cases, [they will], at some point where their application is in question, [be] indeterminate; they have what has been termed an open texture. . [Uncertainty] at the borderline is the price to be paid for the use of general classifying terms. • (CL, pp. 124 -125)

So … • Always a core of certainty – 'General terms would be useless to us as a medium of communication unless there were such familiar, generally unchallenged cases' (CL, p. 123). • And a penumbra of uncertainty where there are respectable reasons both for and against subsuming a case under a term, in which there is: – 'no firm convention or general agreement dictates its use, or, on the other hand, its rejection by the person concerned to classify' (CL, p. 123).

An on-going challenge • On Hart’s account, the problem of "open texture" will recur regularly, because there are "fact-situations, continually thrown up by nature or human invention, which possess only some of the features of the plain cases but others which they lack". (CL, p. 123) • So we might build consensus about whether to apply a general term to particular, relatively common, borderline case, but that won’t eliminate "open texture” challenge, for life will soon provide more uncertain borderline cases to replace those convention has transformed into "plain-cases”.

Hart’s conclusion • At the penumbra, or in penumbral cases, judicial discretion is inevitable: – 'no firm convention or general agreement dictates its use, or, on the other hand, its rejection by the person concerned to classify' (CL, p. 123). • In these cases the rule’s, and so the law's, guidance runs out, and it is the judge who must choose whether to subsume the entity or fact-situation under the rule.

Hart’s conclusion cont. , • The judge must simply decide whether penumbral cases are to be considered ‘vehicle’ for the purposes of the rule. • And the judge’s decision, 'even though it may not be arbitrary or irrational is in effect a choice' (CL, p. 124). • A choice is to be based upon a reasonable compromise of what appears to the judge to be reasonable social aims, and purposes. It will therefore amount to the exercise of a quasilegislative discretion.

Remember …. Hart rejects formalism for two reasons • Argues that judicial discretion is both: – Necessary and – Desirable

The argument from desirability • According to Hart, – “We should not cherish, even as an ideal, the conception of a rule so detailed that the question whether it applied or not to a particular case was always settled in advance, and never involved, at the point of application, a fresh choice between open alternatives. ” (CL, p. 125, emphasis added).

So shouldn’t fix open texture even if we could … “Because we shall thus indeed succeed in settling in advance, but also in the dark, issues which can only reasonably be settled when they arise and are identified. We shall be forced by this technique to include in the scope of a rule cases which we would wish to exclude in order to give effect to reasonable social aims, and which the open-textured terms of our language would have allowed us to exclude, had we left them less rigidly defined. The rigidity of our classifications will thus war with our aims in having or maintaining the rule. ” (CL, pp. 126 -127)

So shouldn’t fix open texture even if we could …cont. ". . . we labour under two connected handicaps. . . The first. . . is our relative ignorance of fact: the second is our relative indeterminacy of aim". (Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 125).

But a puzzle here? • Hart thinks discretion positively desirable when the semantic or linguistic penumbra kicks-in. • There is no ‘normative’ equivalent. • But aren’t there cases where even though the meaning of the rule is clear, it seems we should allow a discretion on ‘justice’ grounds?

That is, should there be a normative penumbra? The Ambulance Driver: – Ambulance plainly a vehicle, but aren’t there substantive grounds to think discretion is desirable?

Waluchow …. • The possibility of unwanted results serves as a sufficient reason for preserving the penumbra even when it could be eliminated. Why does this possibility not also serve as a sufficient reason for following the practice of not considering a rule applicable when, unfortunately, the plain meanings of the general terms used in its expression call for a clearly undesirable result - a result which we could have avoided if, by some stroke of luck, the case had fallen within the penumbra? In other words, cannot Hart's desirability argument be extended to what I'll call 'plain meaning cases' - cases which do not fall within the open-textured penumbra of the rule's general terms, but rather within their core of settled meaning? In short, can't the argument be extended to cases like Riggs ? • Wilfrid J. Waluchow, ‘Hart, Legal Rules and Palm Tree Justice’ Law and Philosophy, 4. 1 (1985), 41 -70, 54

Hrt 2 hrt

Hrt 2 hrt Legal realism vs natural law

Legal realism vs natural law No moral

No moral Descriptive ethics vs normative ethics

Descriptive ethics vs normative ethics Realism vs anti realism

Realism vs anti realism Realism philosophy

Realism philosophy Realism philosophy in education

Realism philosophy in education Indirect realism a level philosophy

Indirect realism a level philosophy Newton's first law and second law and third law

Newton's first law and second law and third law Si unit of newton's first law

Si unit of newton's first law Positive law

Positive law What is realism

What is realism Pragmatic legal realism

Pragmatic legal realism Legal realism

Legal realism Realism and naturalism in american literature

Realism and naturalism in american literature Regionalism literary movement

Regionalism literary movement Naturalism

Naturalism Characteristics of african legal philosophy (lju4801)

Characteristics of african legal philosophy (lju4801) Characteristics of realism

Characteristics of realism Realism in american literature

Realism in american literature Realism naturalism modernism

Realism naturalism modernism Development of modern american drama

Development of modern american drama American realism essay

American realism essay Boyles law

Boyles law Boyle's law charles law avogadro's law

Boyle's law charles law avogadro's law Unit 1 introduction to law and the legal system

Unit 1 introduction to law and the legal system Bell and hart's eight causes of conflict

Bell and hart's eight causes of conflict Hart learning and development

Hart learning and development Legal assistance services townsville

Legal assistance services townsville Kitzler witze

Kitzler witze Laat de vlam weer branden tekst

Laat de vlam weer branden tekst Hart plain infant school

Hart plain infant school Principle of fouchet test

Principle of fouchet test Hart q connection

Hart q connection Hart team norfolk

Hart team norfolk Chlorophyta

Chlorophyta Scala della partecipazione di hart

Scala della partecipazione di hart Proudfoot v hart

Proudfoot v hart Holland & hart

Holland & hart Ik wil terug naar het hart van aanbidding

Ik wil terug naar het hart van aanbidding Heilig hart turnhout

Heilig hart turnhout Scala della partecipazione di hart

Scala della partecipazione di hart Grote en kleine bloedsomloop

Grote en kleine bloedsomloop Proudfoot v hart

Proudfoot v hart Gezondheidsuniversiteit

Gezondheidsuniversiteit Hart van brabant rabobank

Hart van brabant rabobank Loriot das ei ist hart text

Loriot das ei ist hart text Dylan thomas bio

Dylan thomas bio Zorg in hart van brabant

Zorg in hart van brabant