OUTCOME EVALUATION OF NSWs SAFER PATHWAY PROGRAM VICTIMS

- Slides: 56

OUTCOME EVALUATION OF NSW’s SAFER PATHWAY PROGRAM: VICTIMS’ EXPERIENCES Lily Trimboli NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research The Applied Research in Crime and Justice Conference 15 – 16 February 2017

BACKGROUND • Domestic violence is a significant problem with social, economic, health and financial consequences. • It includes physical assault; stalking; verbal, emotional or psychological abuse; threats of violence; harassment and intimidation.

RESEARCH AIMS 1. to see whether the Safer Pathway program is more effective in reducing domestic violence related offences (e. g. physical assault, threats of physical assault, intimidation) than the conventional response to such offences. 2. to describe key features of the program’s operation and the response of domestic violence victims to the services provided.

SAFER PATHWAY PROGRAM • Safer Pathway is a service delivery model, developed in response to the recommendations of three enquiries that were very critical of the existing system. • Provides an integrated response from government and non-government agencies to both female and male victims who have been assessed at risk of future domestic violence. • It applies to victims in both intimate partner relationships and non-intimate relationships. • It is being implemented in stages across NSW.

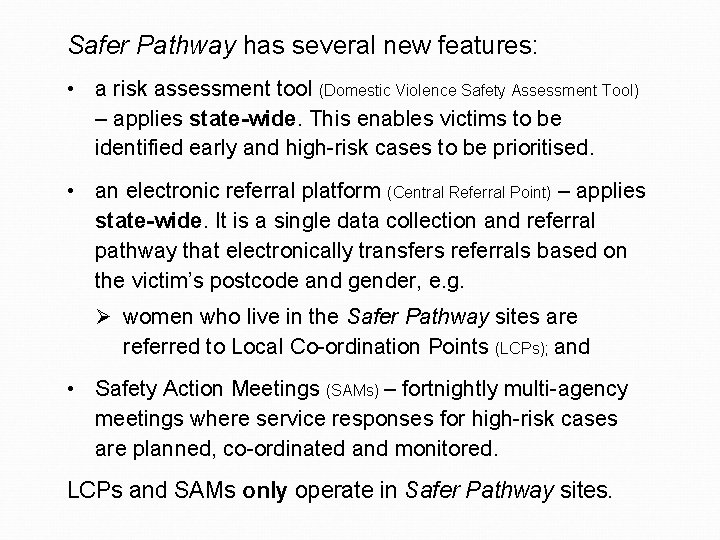

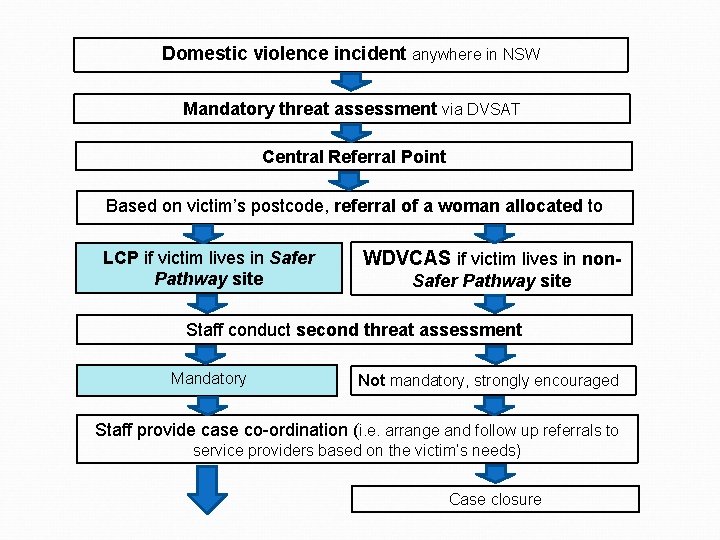

Safer Pathway has several new features: • a risk assessment tool (Domestic Violence Safety Assessment Tool) – applies state-wide. This enables victims to be identified early and high-risk cases to be prioritised. • an electronic referral platform (Central Referral Point) – applies state-wide. It is a single data collection and referral pathway that electronically transfers referrals based on the victim’s postcode and gender, e. g. Ø women who live in the Safer Pathway sites are referred to Local Co-ordination Points (LCPs); and • Safety Action Meetings (SAMs) – fortnightly multi-agency meetings where service responses for high-risk cases are planned, co-ordinated and monitored. LCPs and SAMs only operate in Safer Pathway sites.

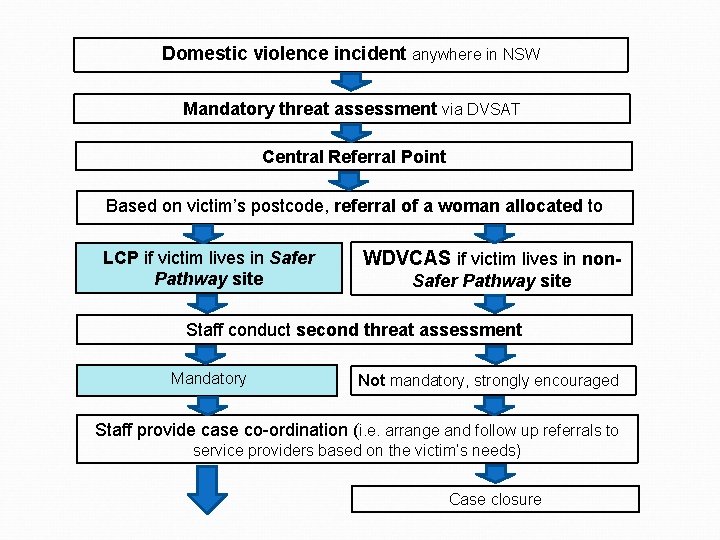

Domestic violence incident anywhere in NSW Mandatory threat assessment via DVSAT Central Referral Point Based on victim’s postcode, referral of a woman allocated to LCP if victim lives in Safer Pathway site WDVCAS if victim lives in non. Safer Pathway site Staff conduct second threat assessment Mandatory Not mandatory, strongly encouraged Staff provide case co-ordination (i. e. arrange and follow up referrals to service providers based on the victim’s needs) Case closure

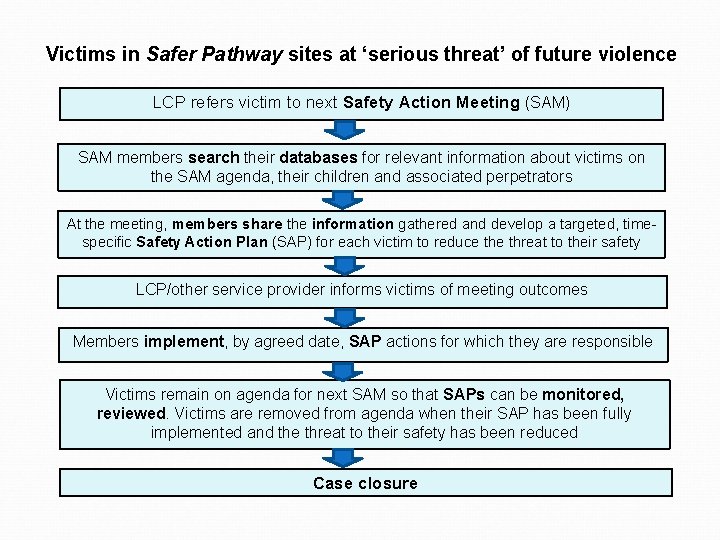

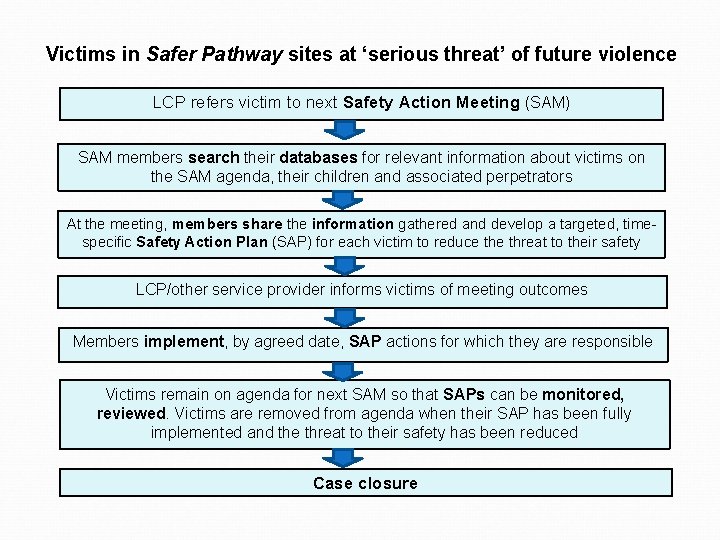

Victims in Safer Pathway sites at ‘serious threat’ of future violence LCP refers victim to next Safety Action Meeting (SAM) SAM members search their databases for relevant information about victims on the SAM agenda, their children and associated perpetrators At the meeting, members share the information gathered and develop a targeted, timespecific Safety Action Plan (SAP) for each victim to reduce threat to their safety LCP/other service provider informs victims of meeting outcomes Members implement, by agreed date, SAP actions for which they are responsible Victims remain on agenda for next SAM so that SAPs can be monitored, reviewed. Victims are removed from agenda when their SAP has been fully implemented and the threat to their safety has been reduced Case closure

SAFER PATHWAY PROGRAM continued • Programs with similar elements operate both overseas and in other Australian jurisdictions (e. g. Northern Territory, South Australia). • NSWs’ program is based on South Australia’s. • Some of these multi-agency domestic violence interventions have been evaluated. • However, those evaluations are not directly comparable to this study.

OTHER EVALUATIONS Based on information available, other evaluations have involved: • police recorded crime data; • one post-intervention interview conducted with small samples of victims, e. g. Ø Marshall et al. (2008) interviewed 5 out of 69 women involved in South Australia’s Safer Framework Program; • questionnaires returned by a small proportion of service users, e. g. Ø in an evaluation of a London scheme, only 73 out of 400 questionnaires were returned.

METHOD

Structured telephone interviews conducted with two groups of female victims of domestic violence assessed at ‘serious threat’ of future violence: 1. an intervention group (n = 69) drawn from the 9 Police Local Area Commands (LACs) in the Safer Pathway program; and 2. a comparison group (n = 61) drawn from 9 LACs where only some elements of the program are operating but LACs well matched to the intervention LACs. In these LACs, there are no LCPs or SAMs. 11

Repeated measures design – both groups of victims interviewed twice and asked the same questions about proscribed behaviours during two time periods: • the month prior to the incident; and • the month after the case co-ordination processes/ comparable period. (In practice, the second interview was conducted about 6 weeks after the date of the incident. Since SAMs are held fortnightly, this allowed time for the victim to be referred to the next scheduled meeting). • proscribed behaviours: stalking, physical assault, threats of physical assault, intimidation and verbal abuse (in person, by phone and by text messages). • pre-post changes in proscribed behaviours in the two groups of victims were compared.

RESULTS

VICTIM CHARACTERISTICS • 2 out of 3 victims aged 25 – 44 years. • 3 out of 4 victims were in an intimate relationship with the defendant. • 4 out of 5 victims born in Australia. • 16. 2% of total group was Indigenous. • 1 out of 3 victims had tertiary qualifications.

IMPACT OF PROGRAM Interview Question: Stalking Between [dates for 4 -week period before and including index incident] did [defendant’s name] follow you about, e. g. did [defendant’s name] watch or approach or hang around the place where you live or where you work or any place where you normally go for social or leisure activities? Yes No Don’t know

If yes, how frequently did this happen? Was it • 1 – 3 times over the 4 -week period • once or twice per week • 3 – 4 times per week • at least once per day.

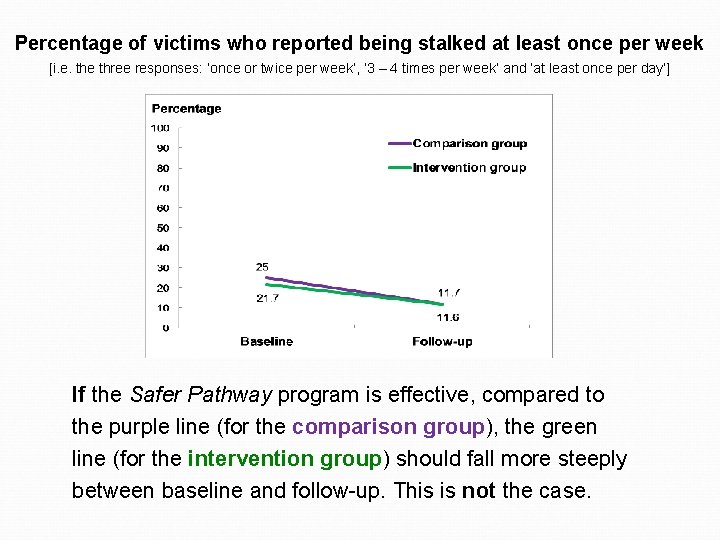

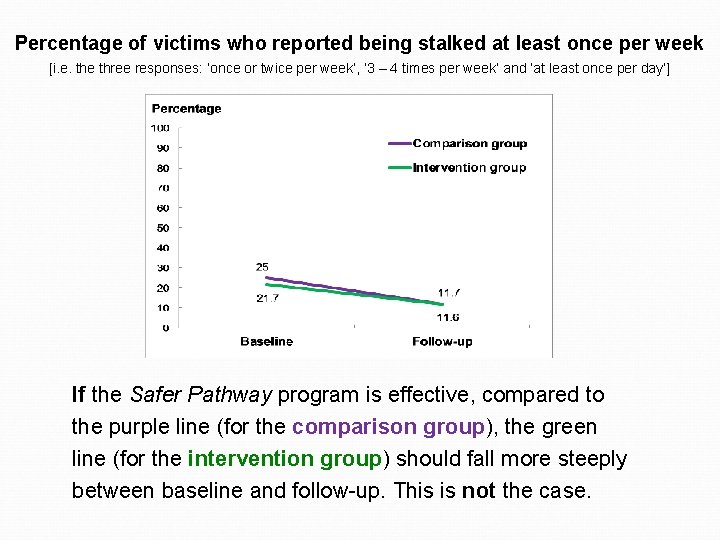

Percentage of victims who reported being stalked at least once per week [i. e. the three responses: ‘once or twice per week’, ‘ 3 – 4 times per week’ and ‘at least once per day’] If the Safer Pathway program is effective, compared to the purple line (for the comparison group), the green line (for the intervention group) should fall more steeply between baseline and follow-up. This is not the case.

Stalking continued Intervention group • during the month before the incident (i. e. at baseline), 21. 7% of victims reported that they had been stalked at least weekly by the defendant; • during the month after the case co-ordination processes (i. e. at follow-up), 11. 6% of victims reported that they had been stalked at least weekly by the defendant – a drop of 10. 1 points. Comparison group • the corresponding fall was very similar (13. 3 points) – from 25% at baseline to 11. 7% at follow-up.

Stalking continued • Over time, the frequency of stalking fell for both the intervention and comparison groups and, from the graph, there is no obvious difference in the magnitude of this decline. • This proved to be the case when tested Ø there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the size of the decline in stalking between baseline and follow-up.

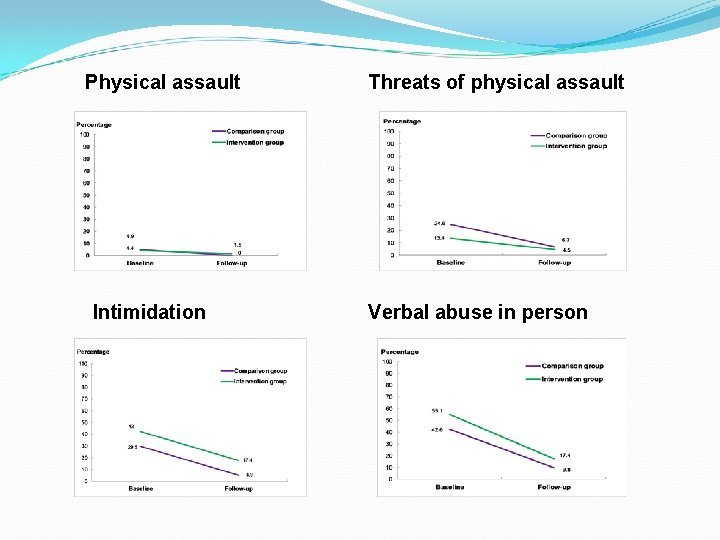

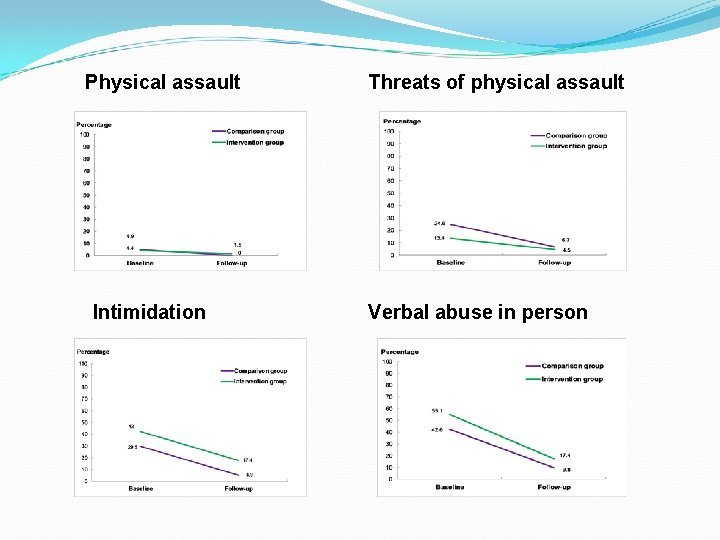

Other proscribed behaviours Pattern of results is the same for: • physical assault; • threats of physical assault; • intimidation; and • verbal abuse (in person, by phone and by text messages).

Physical assault Intimidation Threats of physical assault Verbal abuse in person

Other proscribed behaviours continued • For both the comparison and the intervention groups, there was a statistically significant decrease in each of these behaviours from baseline to follow-up. BUT • The rate of the decrease was similar for the comparison and the intervention groups.

PROGRAM’S OPERATION, SERVICE PROVISION

ADMINISTRATION OF DVSAT • 1 out of 2 victims reported feeling comfortable being asked the DVSAT questions at the time of the incident. • 9 out of 10 victims reported being treated respectfully by the police officer when he/she asked the DVSAT questions. • Most victims preferred to be asked the DVSAT questions at the time of the incident rather than at another time.

VICTIMS CONTACTED BY SERVICES? Did any services or agencies contact you in the past four weeks/since the SAM? yes • Comparison group: 49. 2% (n = 30) • Intervention group: 59. 4% (n = 41) difference between the two groups – not statistically significant. Victims named a range of services/agencies that had contacted them – housing, police, generalist counselling, child-related services.

VICTIMS CONTACTED BY DV AGENCIES Main type of agency contacting victims was domestic violence related: • Comparison group: 13 (2 in 5 of the 30 victims who reported that agencies had contacted them); • Intervention group: 24 (3 in 5 of the 41 victims who reported that agencies had contacted them) victims reported they were contacted by at least one domestic violence related agency. Most were satisfied with the support received BUT 21. 6% stated the agency could have done more to help them.

ADDITIONAL SUPPORT NEEDED • 1 in 4 of the 71 women who reported services had contacted them stated they needed additional support that had not been offered. • 1 in 5 of the 59 women who reported that no agencies had contacted them/couldn’t recall whether they had been contacted stated that they needed support during the reference period. • Support needed related to housing, financial assistance, advice about AVOs, counselling.

DISLIKED ABOUT SUPPORT • Most victims reported there was nothing they disliked about the support received during the previous four weeks/after the SAM. • Elements disliked were: Ø police-related issues (noted by 8 victims; e. g. condescending, not supportive, arrived late); Ø a lack of, or a delay in, follow-up (noted by 5 victims); Ø insufficient resources (noted by 5 victims, e. g. need better drug programs).

INTERVENTION GROUP

SAM PROCEDURES • Victims assessed at ‘serious threat’ of future violence must be referred to the next Safety Action Meeting. • Staff must tell victims about the meeting and ask their consent for the referral. However • A SAM referral happens even if victims refuse consent. Victims are told this is because there are serious concerns for their safety. • Victims are informed of the meeting’s purpose, who will attend and the potential outcomes. • After the meeting, staff advise victims of the actions that will be taken to reduce threat to their safety.

TOLD OF REFERRAL TO SAM? Of the 68 victims in the intervention group (missing response for 1 victim): • 33 (48. 5%) reported that they had been told their case would be referred to a SAM where the issue of their safety would be discussed; • of the remaining 35 (51. 5%) victims: Ø 28 stated that they had not been told about a SAM referral; and Ø 7 stated that they could not recall whether they had been told.

REFERRAL TO SAM • Of the 33 victims who reported that they had been told their case would be referred to a SAM, 24 (7 in 10) agreed to the referral. Ø main reasons victims agreed: to get support/help, to enhance her safety and it might be useful. • Of these 24 women who agreed to their case being referred to a SAM, 15 (3 in 5) reported feeling comfortable knowing that workers from different agencies would discuss their case at a SAM.

CONTACTED AFTER SAM? Of 69 women in intervention group: • 40. 6% yes • 59. 4% no/can’t recall

RECOMMEND REFERRAL TO SAM? 91. 7% (33 out of 36) reported that they would suggest that others in a similar situation agree to being referred to a SAM.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS

With one exception – referral to SAMs and the case co -ordination processes – every DV victim in NSW receives similar responses from key authorities: • DVSAT, referral to CRP and then, for women, referral to LCP or WDVCAS. This DVSAT/referral process might affect risk of repeat victimisation in two ways: 1. being asked the 25 DVSAT questions by the police at the incident may encourage women to re-assess their relationship with their intimate partner (perhaps to take the violence more seriously instead of minimising it); victims might take action to change their circumstances to reduce their risk.

2. automatic referral of victims to LCP or WDVCAS staff through the CRP process may reduce subsequent victimisation through the victim support and services staff provide or facilitate, e. g. staff • help women to develop safety or escape plans; • make ‘warm’ referrals to relevant service providers based on victims’ needs (e. g. housing, DV counselling, welfare assistance, family services); and • follow-up women at serious threat to check on their safety and on the progress of the referrals made.

This referral/support process seems to work equally well (at least in the short-term) whether these actions are initiated by LCP staff (and supported by the SAM process) or delivered by WDVCAS staff. We know that staff in both the intervention and the comparison sites assist victims – • 3 in 5 women in the intervention group and 1 in 2 women in the comparison group in this sample reported that services had initiated contact with them in the 4 -week reference period after the incident. • There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups on this issue.

CHANGE IN DEFENDANT BEHAVIOUR • Perhaps the defendant changes his/her behaviour because the police attended at the time of the incident. This may create a deterrent effect. • The defendant might discontinue or at least reduce the violence towards the victim (even if it is only for a short period of time) because he/she: Ø fears the legal or social consequences, or Ø believes that there is an increased risk of being caught and sanctioned.

CONCLUSIONS

• The procedure of referring victims to Safety Action Meetings and the associated processes does not appear to provide victims any extra short-term benefits over and above the systems that operate for women at serious threat in the comparison sites. • This study shows that victims in both the intervention and the comparison group were treated in a similar manner by the various authorities involved.

STUDY STRENGTHS, LIMITATIONS

STUDY STRENGTHS 1. Comparison group with LACs well-matched to intervention LACs. 2. Large sample size (n = 130 women). 3. Sensitive measure of offending/ victimisation (i. e. victim self-report through structured telephone interviews). 4. Repeated measures design (each victim was interviewed twice regarding 4 -week period prior to the incident and 4 -week period after the case coordination processes/comparable period).

STUDY LIMITATIONS 1. Short follow-up period (i. e. a few weeks). 2. An even larger sample size may have detected small intervention effects, if they exist. 3. No measure of program implementation success. Program implementation may have varied across LACs.

FUTURE RESEARCH

• Some of these limitations will be addressed by comparing trends in domestic violence related incidents at the LAC level for Safer Pathway and non-Safer Pathway sites. • This work is currently being undertaken by BOCSAR. • The results will be available later this year.

THANK YOU. Lily Trimboli NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research lily. trimboli@justice. nsw. gov. au Report available: May 2017 [approximately]

EXTRAS

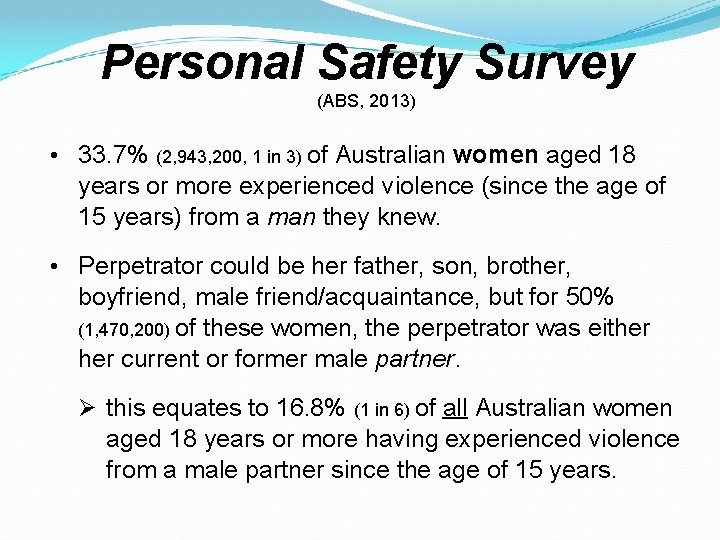

Personal Safety Survey (ABS, 2013) • 33. 7% (2, 943, 200, 1 in 3) of Australian women aged 18 years or more experienced violence (since the age of 15 years) from a man they knew. • Perpetrator could be her father, son, brother, boyfriend, male friend/acquaintance, but for 50% (1, 470, 200) of these women, the perpetrator was either current or former male partner. Ø this equates to 16. 8% (1 in 6) of all Australian women aged 18 years or more having experienced violence from a male partner since the age of 15 years.

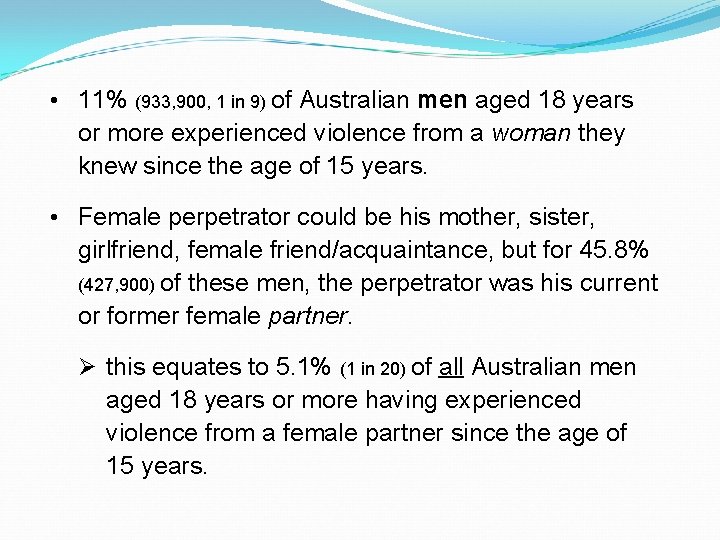

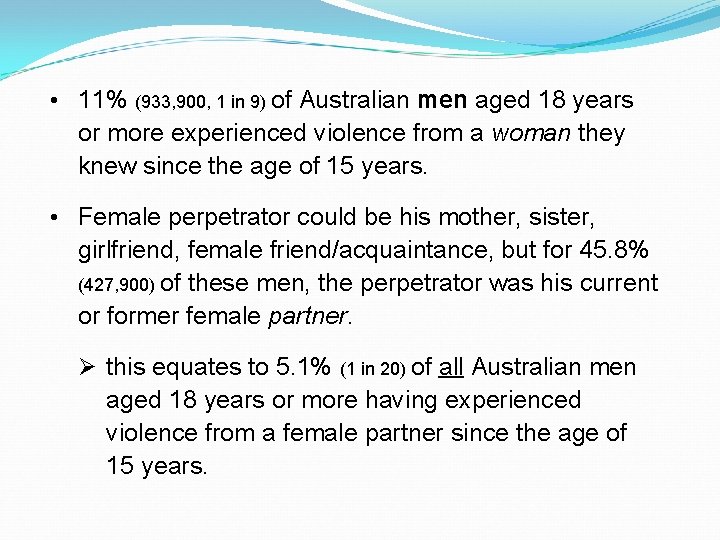

• 11% (933, 900, 1 in 9) of Australian men aged 18 years or more experienced violence from a woman they knew since the age of 15 years. • Female perpetrator could be his mother, sister, girlfriend, female friend/acquaintance, but for 45. 8% (427, 900) of these men, the perpetrator was his current or former female partner. Ø this equates to 5. 1% (1 in 20) of all Australian men aged 18 years or more having experienced violence from a female partner since the age of 15 years.

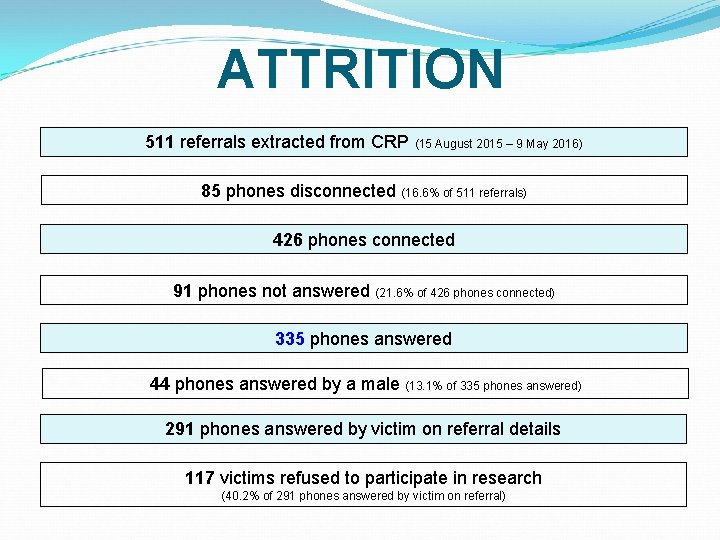

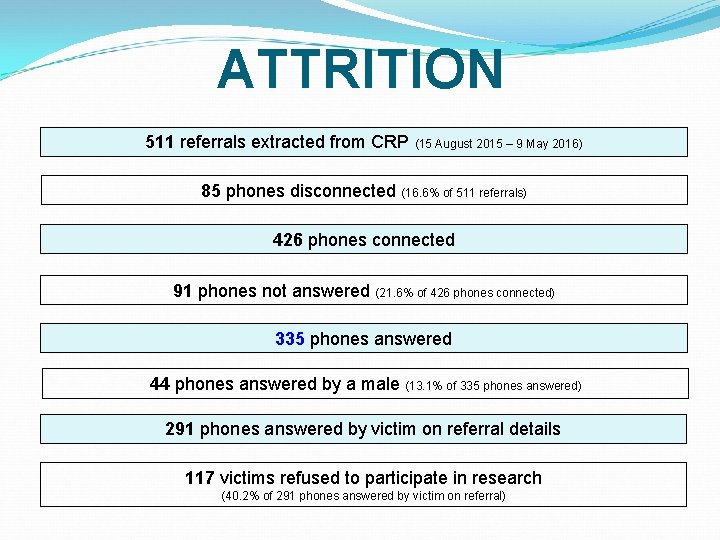

ATTRITION 511 referrals extracted from CRP (15 August 2015 – 9 May 2016) 85 phones disconnected (16. 6% of 511 referrals) 426 phones connected 91 phones not answered (21. 6% of 426 phones connected) 335 phones answered 44 phones answered by a male (13. 1% of 335 phones answered) 291 phones answered by victim on referral details 117 victims refused to participate in research (40. 2% of 291 phones answered by victim on referral)

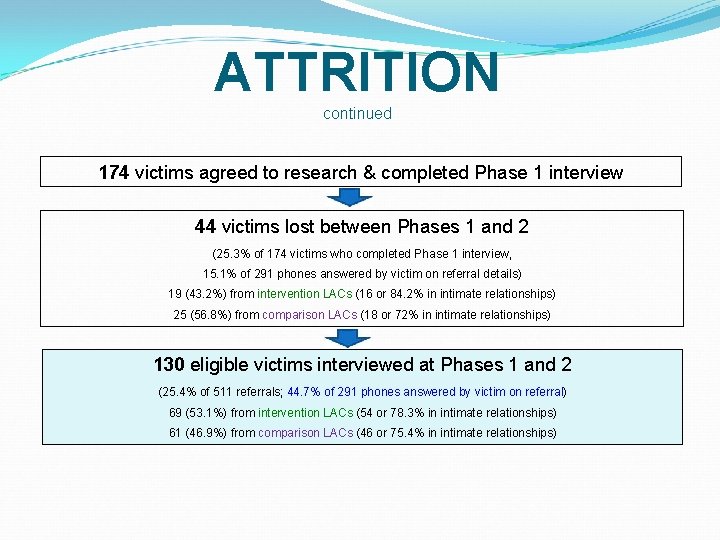

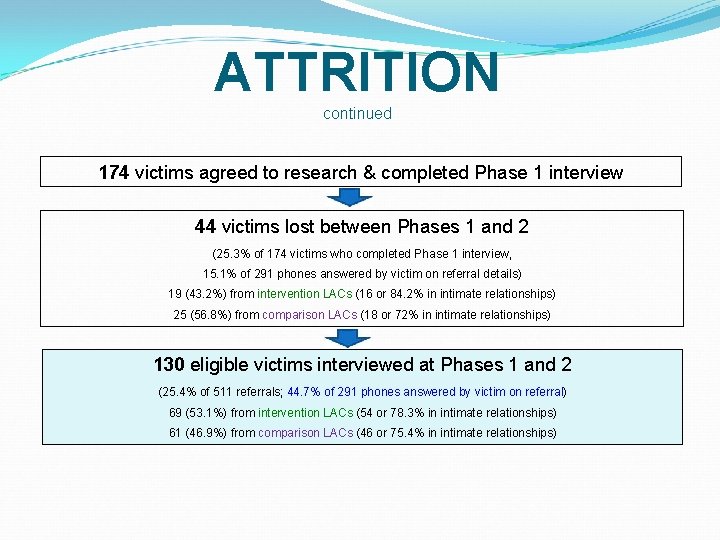

ATTRITION continued 174 victims agreed to research & completed Phase 1 interview 44 victims lost between Phases 1 and 2 (25. 3% of 174 victims who completed Phase 1 interview, 15. 1% of 291 phones answered by victim on referral details) 19 (43. 2%) from intervention LACs (16 or 84. 2% in intimate relationships) 25 (56. 8%) from comparison LACs (18 or 72% in intimate relationships) 130 eligible victims interviewed at Phases 1 and 2 (25. 4% of 511 referrals; 44. 7% of 291 phones answered by victim on referral) 69 (53. 1%) from intervention LACs (54 or 78. 3% in intimate relationships) 61 (46. 9%) from comparison LACs (46 or 75. 4% in intimate relationships)

MALES EXCLUDED Male victims were not included in this study because: • most victims of domestic violence are women; • the male sample size would be very small, precluding analyses to be separated out by gender; • the type and availability of services catering to male victims are very different to those for female victims, and much fewer in number; and • after piloting the interview with a small number of male victims, it became apparent that male interviewers would be needed and BOCSAR did not have resources available at the time to do this.

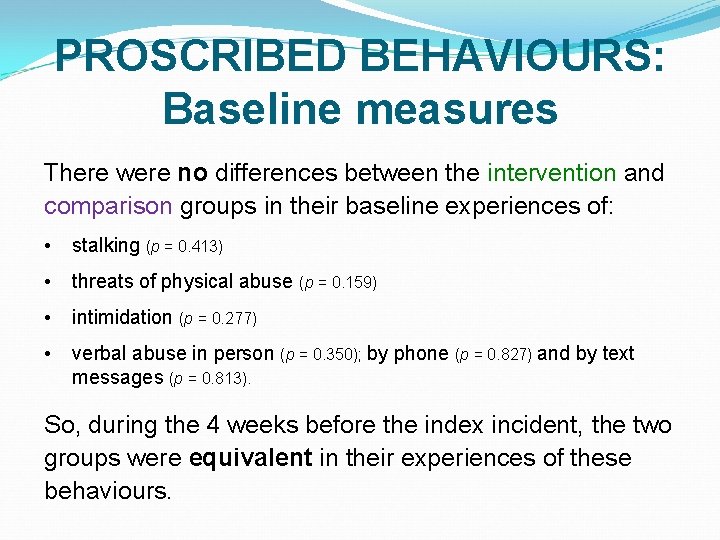

PROSCRIBED BEHAVIOURS: Baseline measures There were no differences between the intervention and comparison groups in their baseline experiences of: • stalking (p = 0. 413) • threats of physical abuse (p = 0. 159) • intimidation (p = 0. 277) • verbal abuse in person (p = 0. 350); by phone (p = 0. 827) and by text messages (p = 0. 813). So, during the 4 weeks before the index incident, the two groups were equivalent in their experiences of these behaviours.

Physical assault: Baseline measures The one exception was physical assault. At baseline, compared with victims in the comparison group, a higher percentage of victims in the intervention group had been assaulted at least once during the four weeks before the index incident at which the police administered the DVSAT (OR = 3. 26, p = 0. 002*).