Du Pont Analysis Dr Craig Ruff Department of

- Slides: 33

Du. Pont Analysis Dr. Craig Ruff Department of Finance J. Mack Robinson College of Business Georgia State University © 2014 Craig Ruff 1

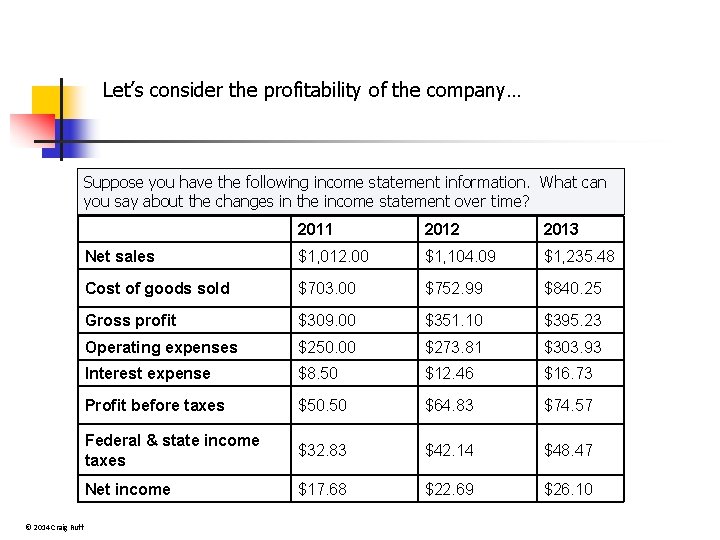

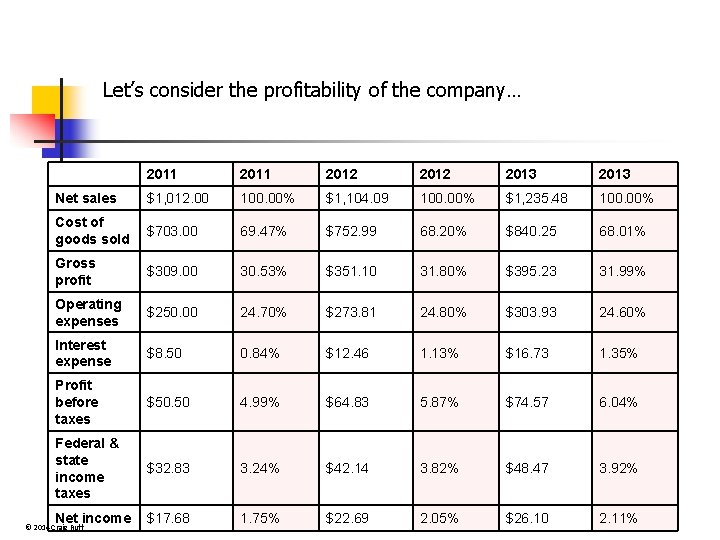

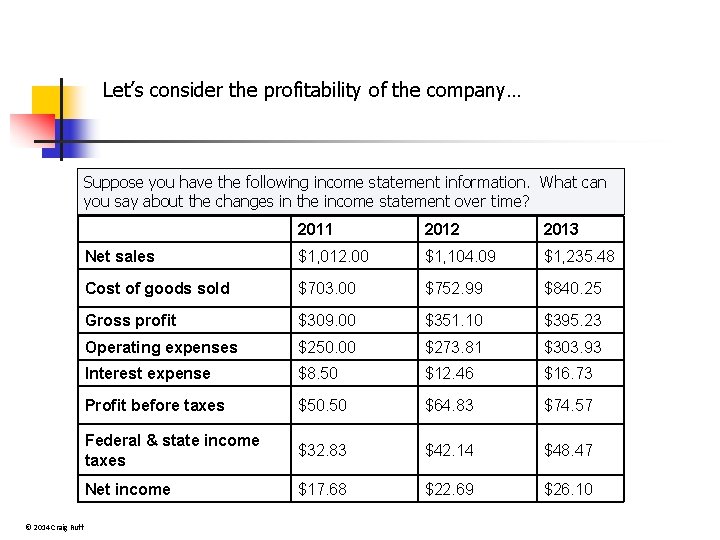

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… Suppose you have the following income statement information. What can you say about the changes in the income statement over time? © 2014 Craig Ruff 2011 2012 2013 Net sales $1, 012. 00 $1, 104. 09 $1, 235. 48 Cost of goods sold $703. 00 $752. 99 $840. 25 Gross profit $309. 00 $351. 10 $395. 23 Operating expenses $250. 00 $273. 81 $303. 93 Interest expense $8. 50 $12. 46 $16. 73 Profit before taxes $50. 50 $64. 83 $74. 57 Federal & state income taxes $32. 83 $42. 14 $48. 47 Net income $17. 68 $22. 69 $26. 10

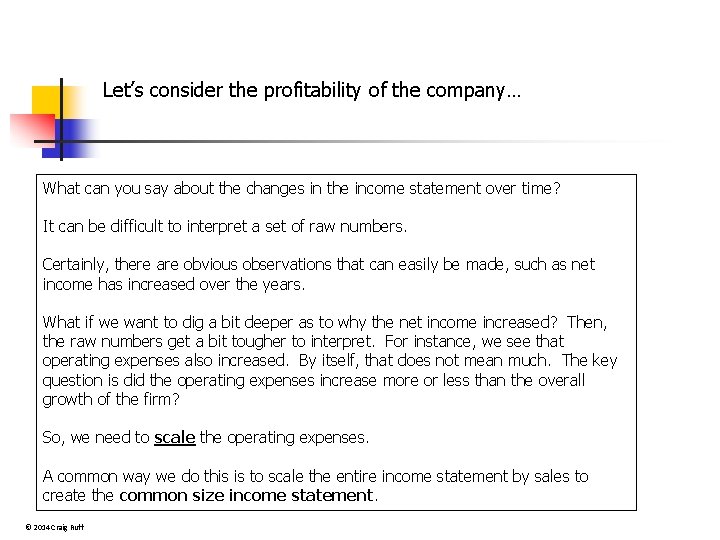

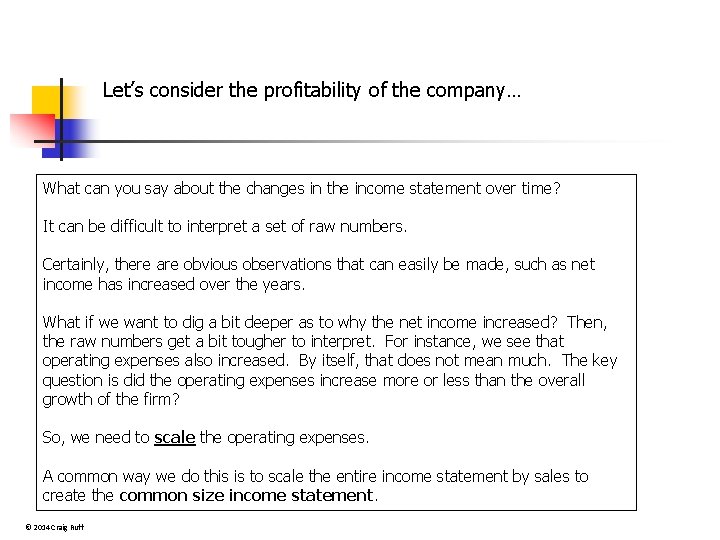

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… What can you say about the changes in the income statement over time? It can be difficult to interpret a set of raw numbers. Certainly, there are obvious observations that can easily be made, such as net income has increased over the years. What if we want to dig a bit deeper as to why the net income increased? Then, the raw numbers get a bit tougher to interpret. For instance, we see that operating expenses also increased. By itself, that does not mean much. The key question is did the operating expenses increase more or less than the overall growth of the firm? So, we need to scale the operating expenses. A common way we do this is to scale the entire income statement by sales to create the common size income statement. © 2014 Craig Ruff

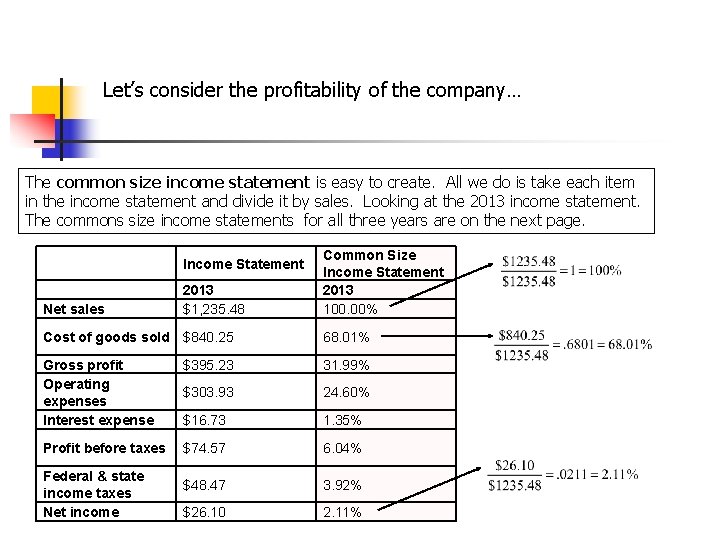

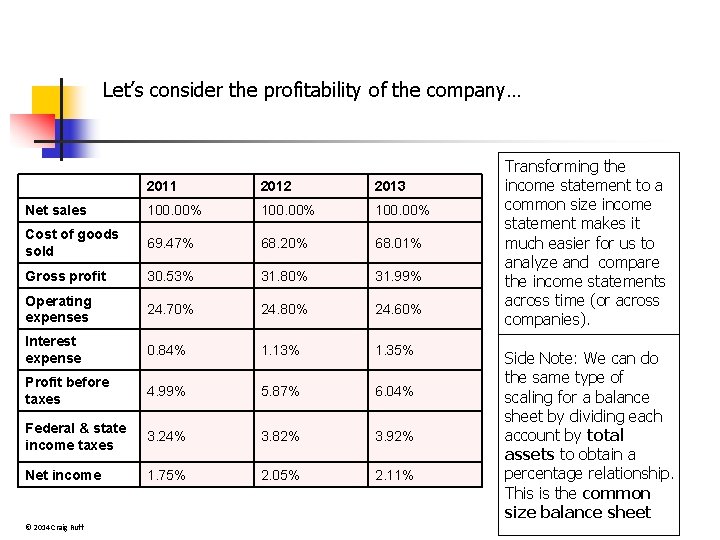

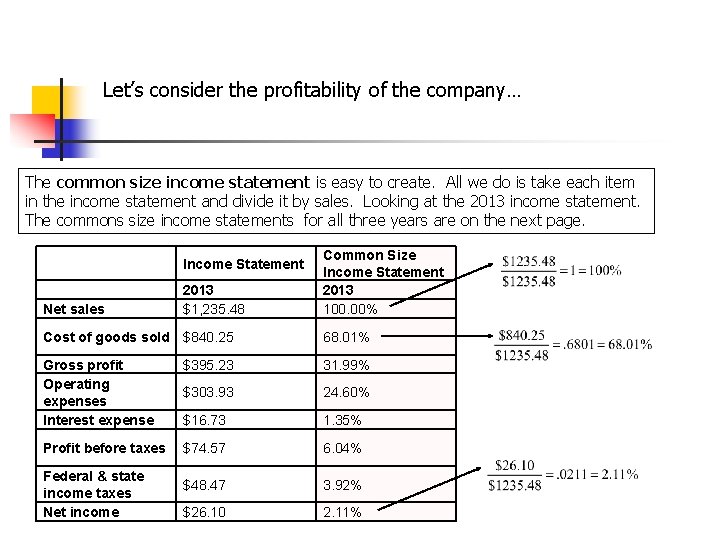

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… The common size income statement is easy to create. All we do is take each item in the income statement and divide it by sales. Looking at the 2013 income statement. The commons size income statements for all three years are on the next page. Income Statement Net sales 2013 $1, 235. 48 Common Size Income Statement 2013 100. 00% Cost of goods sold $840. 25 68. 01% Gross profit Operating expenses Interest expense $395. 23 31. 99% $303. 93 24. 60% $16. 73 1. 35% Profit before taxes $74. 57 6. 04% $48. 47 3. 92% $26. 10 2. 11% Federal & state income taxes Net income

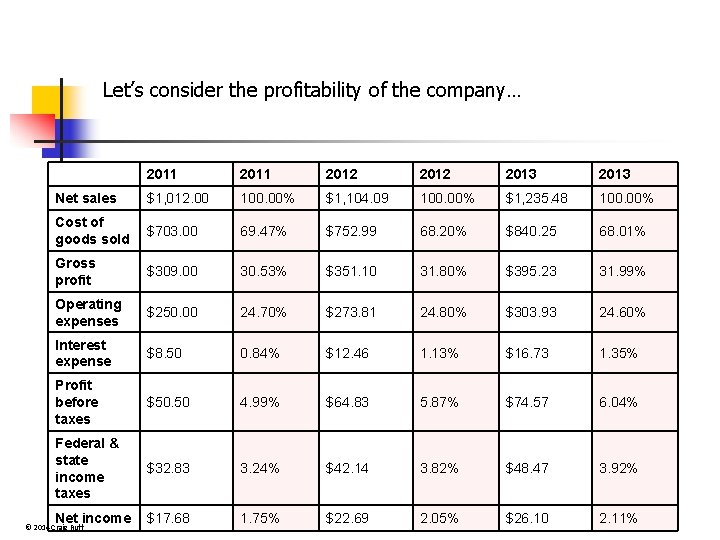

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… 2011 2012 2013 Net sales $1, 012. 00 100. 00% $1, 104. 09 100. 00% $1, 235. 48 100. 00% Cost of goods sold $703. 00 69. 47% $752. 99 68. 20% $840. 25 68. 01% Gross profit $309. 00 30. 53% $351. 10 31. 80% $395. 23 31. 99% Operating expenses $250. 00 24. 70% $273. 81 24. 80% $303. 93 24. 60% Interest expense $8. 50 0. 84% $12. 46 1. 13% $16. 73 1. 35% Profit before taxes $50. 50 4. 99% $64. 83 5. 87% $74. 57 6. 04% Federal & state income taxes $32. 83 3. 24% $42. 14 3. 82% $48. 47 3. 92% Net income $17. 68 1. 75% $22. 69 2. 05% $26. 10 2. 11% © 2014 Craig Ruff

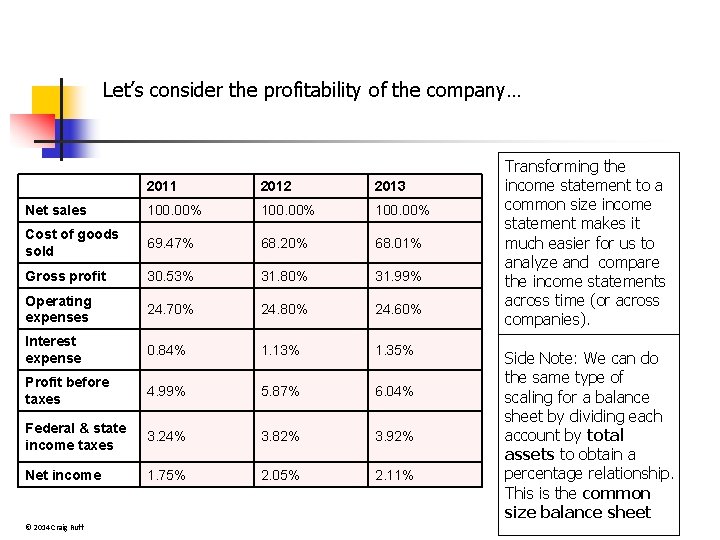

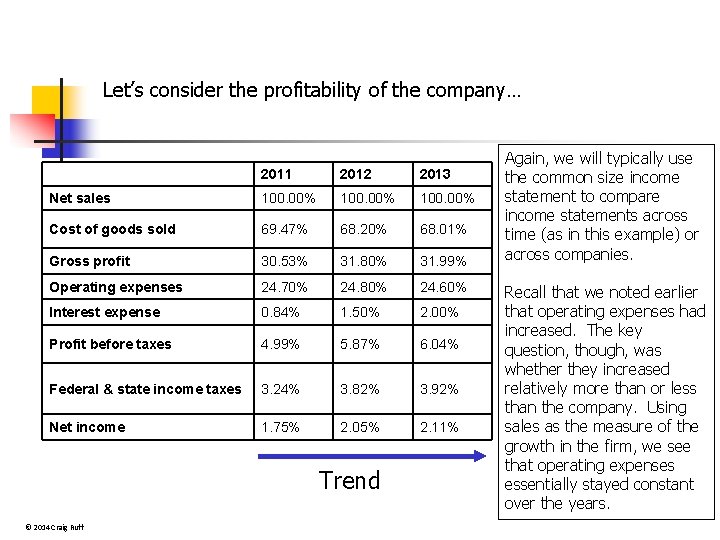

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… 2011 2012 2013 Net sales 100. 00% Cost of goods sold 69. 47% 68. 20% 68. 01% Gross profit 30. 53% 31. 80% 31. 99% Operating expenses 24. 70% 24. 80% 24. 60% Interest expense 0. 84% 1. 13% 1. 35% Profit before taxes 4. 99% 5. 87% 6. 04% Federal & state income taxes 3. 24% 3. 82% 3. 92% Net income 1. 75% 2. 05% 2. 11% © 2014 Craig Ruff Transforming the income statement to a common size income statement makes it much easier for us to analyze and compare the income statements across time (or across companies). Side Note: We can do the same type of scaling for a balance sheet by dividing each account by total assets to obtain a percentage relationship. This is the common size balance sheet

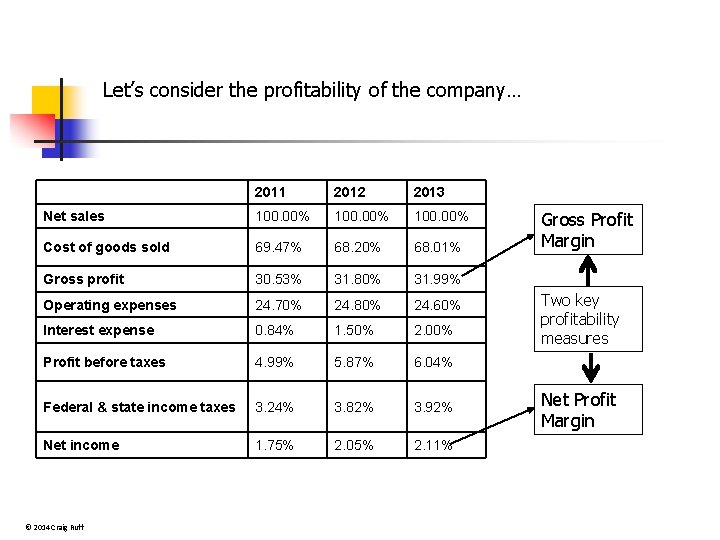

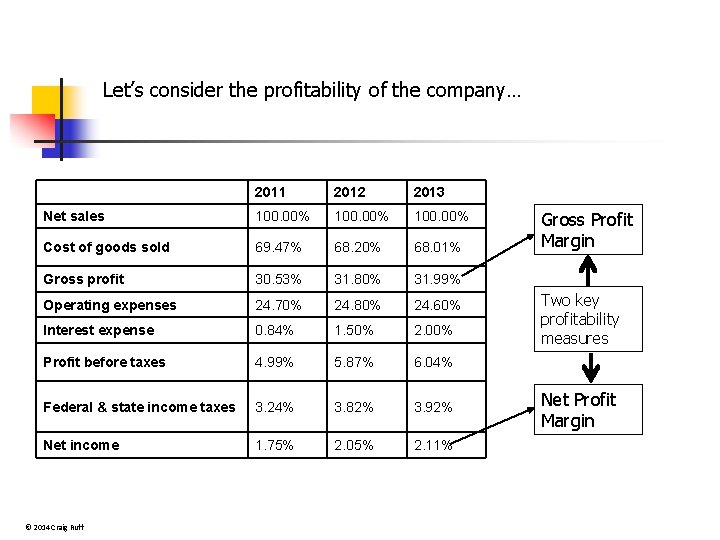

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… 2011 2012 2013 Net sales 100. 00% Cost of goods sold 69. 47% 68. 20% 68. 01% Gross profit 30. 53% 31. 80% 31. 99% Operating expenses 24. 70% 24. 80% 24. 60% Interest expense 0. 84% 1. 50% 2. 00% Profit before taxes 4. 99% 5. 87% 6. 04% Federal & state income taxes 3. 24% 3. 82% 3. 92% Net income 1. 75% 2. 05% 2. 11% © 2014 Craig Ruff Gross Profit Margin Two key profitability measures Net Profit Margin

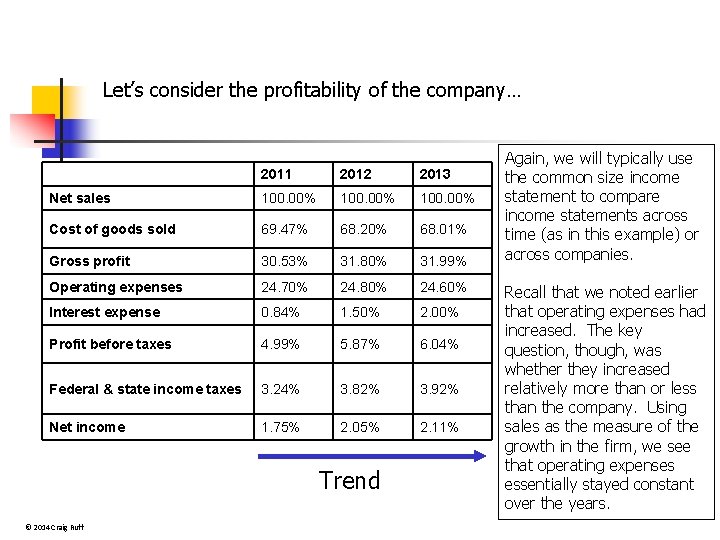

Let’s consider the profitability of the company… 2011 2012 2013 Net sales 100. 00% Cost of goods sold 69. 47% 68. 20% 68. 01% Gross profit 30. 53% 31. 80% 31. 99% Operating expenses 24. 70% 24. 80% 24. 60% Interest expense 0. 84% 1. 50% 2. 00% Profit before taxes 4. 99% 5. 87% 6. 04% Federal & state income taxes 3. 24% 3. 82% 3. 92% Net income 1. 75% 2. 05% 2. 11% Trend © 2014 Craig Ruff Again, we will typically use the common size income statement to compare income statements across time (as in this example) or across companies. Recall that we noted earlier that operating expenses had increased. The key question, though, was whether they increased relatively more than or less than the company. Using sales as the measure of the growth in the firm, we see that operating expenses essentially stayed constant over the years.

Combination Ratios © 2014 Craig Ruff

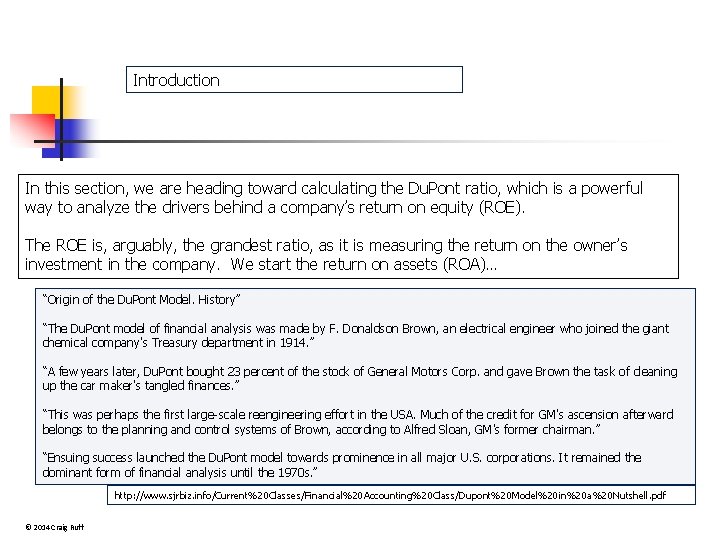

Introduction In this section, we are heading toward calculating the Du. Pont ratio, which is a powerful way to analyze the drivers behind a company’s return on equity (ROE). The ROE is, arguably, the grandest ratio, as it is measuring the return on the owner’s investment in the company. We start the return on assets (ROA)… “Origin of the Du. Pont Model. History” “The Du. Pont model of financial analysis was made by F. Donaldson Brown, an electrical engineer who joined the giant chemical company's Treasury department in 1914. ” “A few years later, Du. Pont bought 23 percent of the stock of General Motors Corp. and gave Brown the task of cleaning up the car maker's tangled finances. ” “This was perhaps the first large-scale reengineering effort in the USA. Much of the credit for GM's ascension afterward belongs to the planning and control systems of Brown, according to Alfred Sloan, GM's former chairman. ” “Ensuing success launched the Du. Pont model towards prominence in all major U. S. corporations. It remained the dominant form of financial analysis until the 1970 s. ” http: //www. sjrbiz. info/Current%20 Classes/Financial%20 Accounting%20 Class/Dupont%20 Model%20 in%20 a%20 Nutshell. pdf © 2014 Craig Ruff

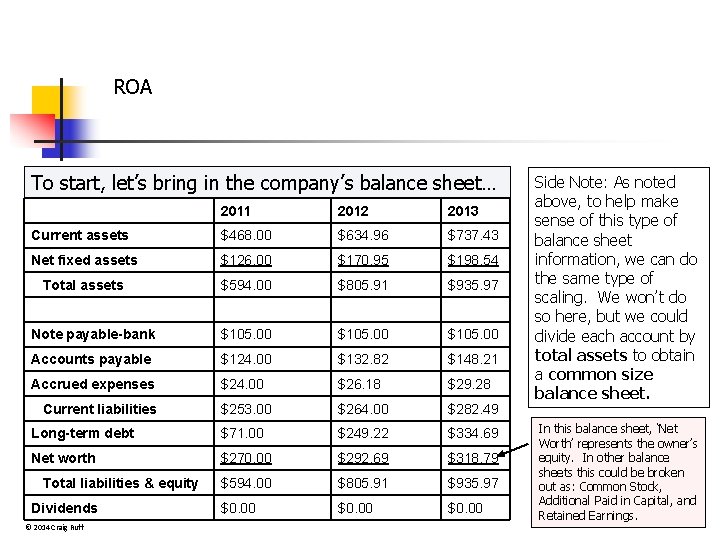

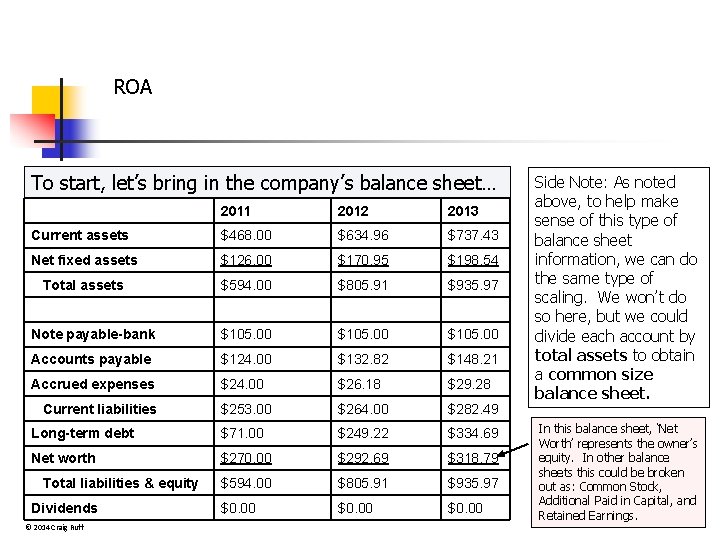

ROA To start, let’s bring in the company’s balance sheet… 2011 2012 2013 Current assets $468. 00 $634. 96 $737. 43 Net fixed assets $126. 00 $170. 95 $198. 54 Total assets $594. 00 $805. 91 $935. 97 Note payable-bank $105. 00 Accounts payable $124. 00 $132. 82 $148. 21 Accrued expenses $24. 00 $26. 18 $29. 28 $253. 00 $264. 00 $282. 49 Long-term debt $71. 00 $249. 22 $334. 69 Net worth $270. 00 $292. 69 $318. 79 $594. 00 $805. 91 $935. 97 $0. 00 Current liabilities Total liabilities & equity Dividends © 2014 Craig Ruff Side Note: As noted above, to help make sense of this type of balance sheet information, we can do the same type of scaling. We won’t do so here, but we could divide each account by total assets to obtain a common size balance sheet. In this balance sheet, ‘Net Worth’ represents the owner’s equity. In other balance sheets this could be broken out as: Common Stock, Additional Paid in Capital, and Retained Earnings.

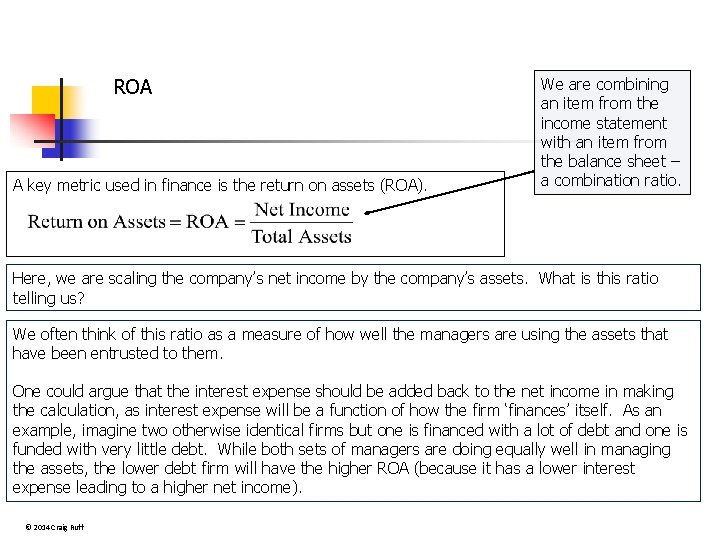

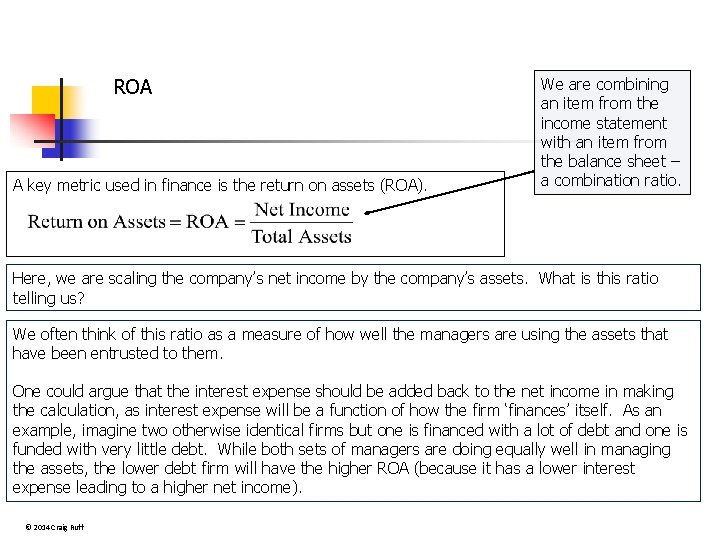

ROA A key metric used in finance is the return on assets (ROA). We are combining an item from the income statement with an item from the balance sheet – a combination ratio. Here, we are scaling the company’s net income by the company’s assets. What is this ratio telling us? We often think of this ratio as a measure of how well the managers are using the assets that have been entrusted to them. One could argue that the interest expense should be added back to the net income in making the calculation, as interest expense will be a function of how the firm ‘finances’ itself. As an example, imagine two otherwise identical firms but one is financed with a lot of debt and one is funded with very little debt. While both sets of managers are doing equally well in managing the assets, the lower debt firm will have the higher ROA (because it has a lower interest expense leading to a higher net income). © 2014 Craig Ruff

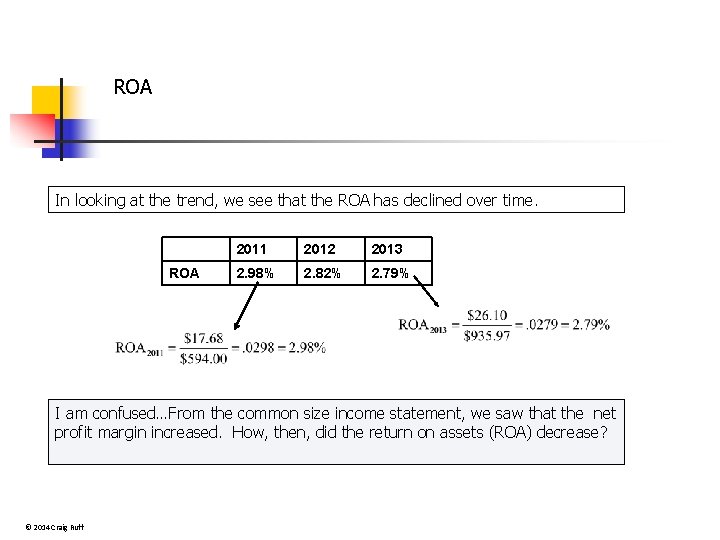

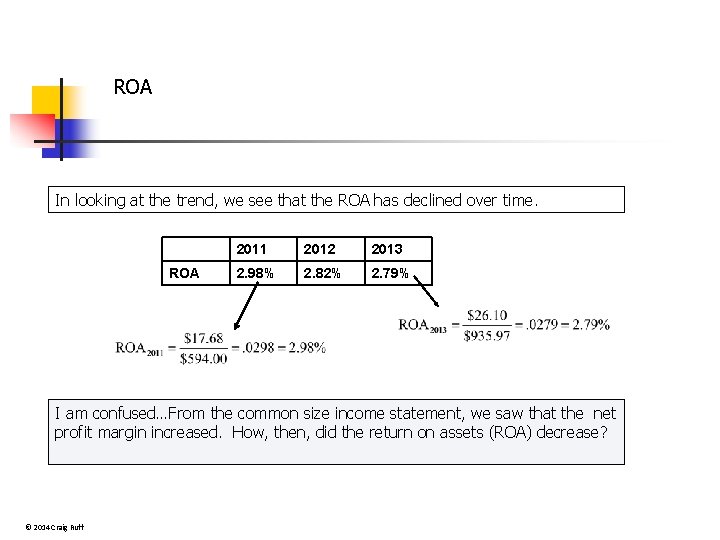

ROA In looking at the trend, we see that the ROA has declined over time. ROA 2011 2012 2013 2. 98% 2. 82% 2. 79% I am confused…From the common size income statement, we saw that the net profit margin increased. How, then, did the return on assets (ROA) decrease? © 2014 Craig Ruff

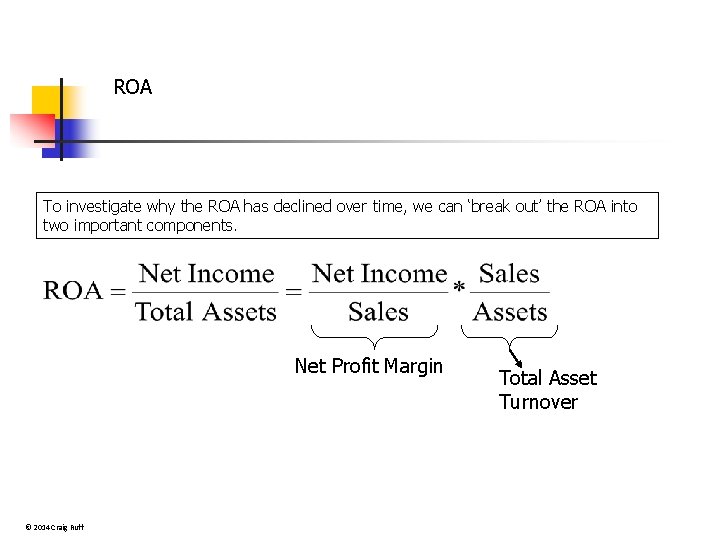

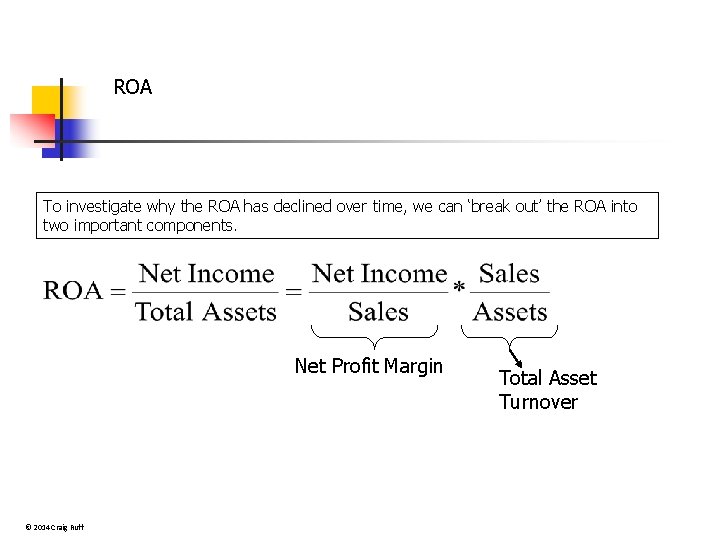

ROA To investigate why the ROA has declined over time, we can ‘break out’ the ROA into two important components. Net Profit Margin © 2014 Craig Ruff Total Asset Turnover

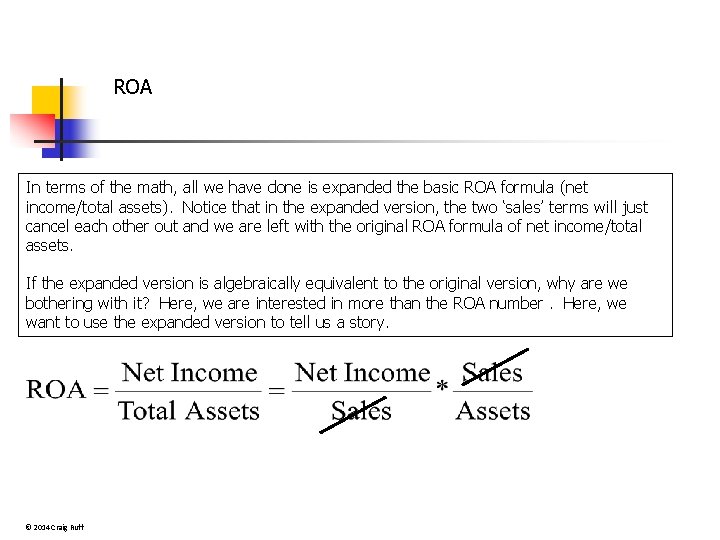

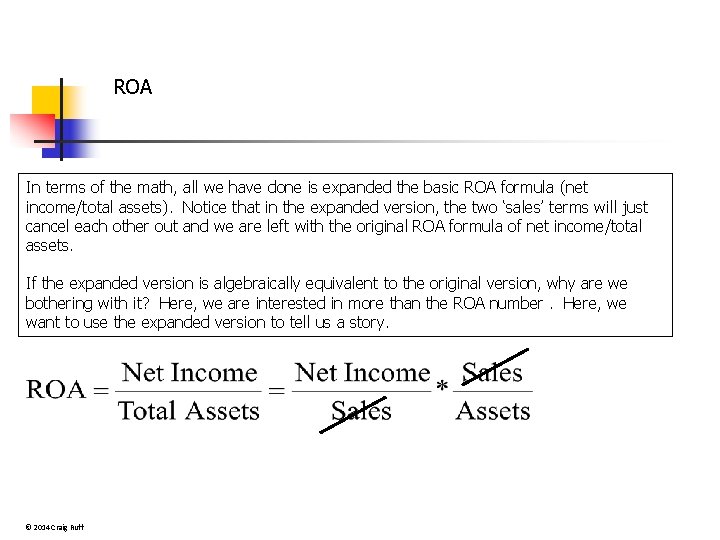

ROA In terms of the math, all we have done is expanded the basic ROA formula (net income/total assets). Notice that in the expanded version, the two ‘sales’ terms will just cancel each other out and we are left with the original ROA formula of net income/total assets. If the expanded version is algebraically equivalent to the original version, why are we bothering with it? Here, we are interested in more than the ROA number. Here, we want to use the expanded version to tell us a story. © 2014 Craig Ruff

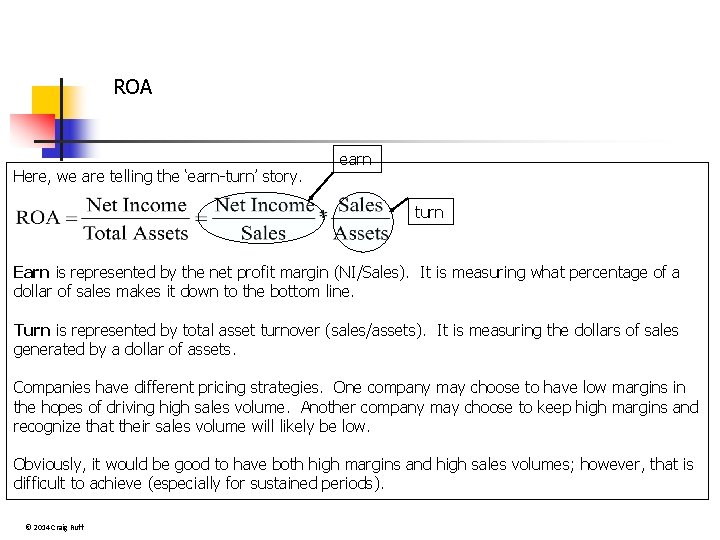

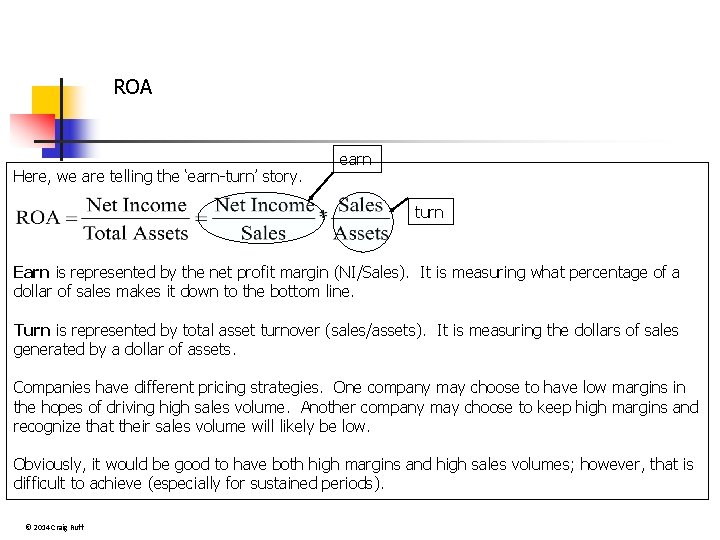

ROA Here, we are telling the ‘earn-turn’ story. earn turn Earn is represented by the net profit margin (NI/Sales). It is measuring what percentage of a dollar of sales makes it down to the bottom line. Turn is represented by total asset turnover (sales/assets). It is measuring the dollars of sales generated by a dollar of assets. Companies have different pricing strategies. One company may choose to have low margins in the hopes of driving high sales volume. Another company may choose to keep high margins and recognize that their sales volume will likely be low. Obviously, it would be good to have both high margins and high sales volumes; however, that is difficult to achieve (especially for sustained periods). © 2014 Craig Ruff

ROA Before going back to our company, let’s consider Whole Foods Market versus Kroger versus Costco. I perceive Whole Foods as a higher-priced, upscale, organic-oriented grocery store. I perceive Kroger as a mainstream grocery store that strives for low prices to compete with increasing competition from chains like Walmart. I perceive Costco as a membership-oriented, highly cost conscious, low-price store. It also sells more than groceries (such as electronics) so the comparison to the other two chains may not be ideal. © 2014 Craig Ruff

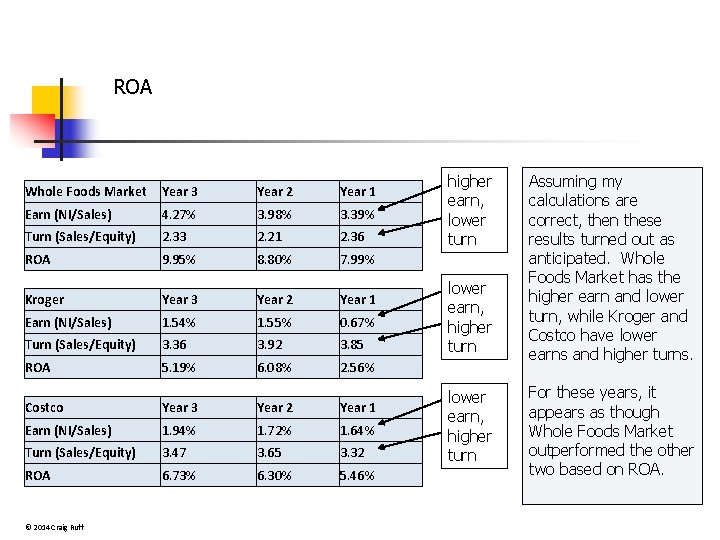

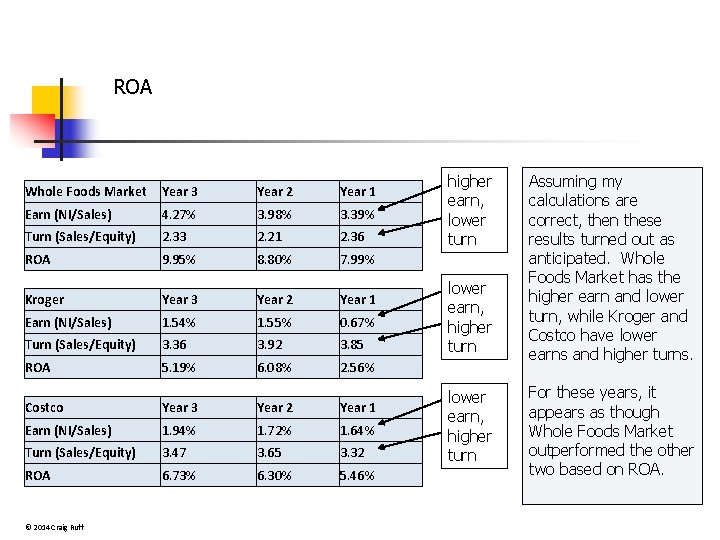

ROA Whole Foods Market Year 3 Year 2 Year 1 Earn (NI/Sales) 4. 27% 3. 98% 3. 39% Turn (Sales/Equity) 2. 33 2. 21 2. 36 ROA 9. 95% 8. 80% 7. 99% Kroger Year 3 Year 2 Year 1 Earn (NI/Sales) 1. 54% 1. 55% 0. 67% Turn (Sales/Equity) 3. 36 3. 92 3. 85 ROA 5. 19% 6. 08% 2. 56% Costco Year 3 Year 2 Year 1 Earn (NI/Sales) 1. 94% 1. 72% 1. 64% Turn (Sales/Equity) 3. 47 3. 65 3. 32 ROA 6. 73% 6. 30% 5. 46% © 2014 Craig Ruff higher earn, lower turn lower earn, higher turn Assuming my calculations are correct, then these results turned out as anticipated. Whole Foods Market has the higher earn and lower turn, while Kroger and Costco have lower earns and higher turns. For these years, it appears as though Whole Foods Market outperformed the other two based on ROA.

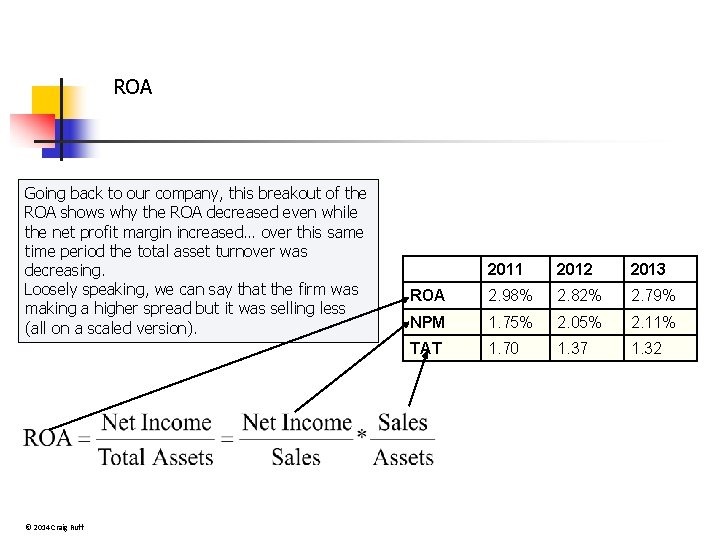

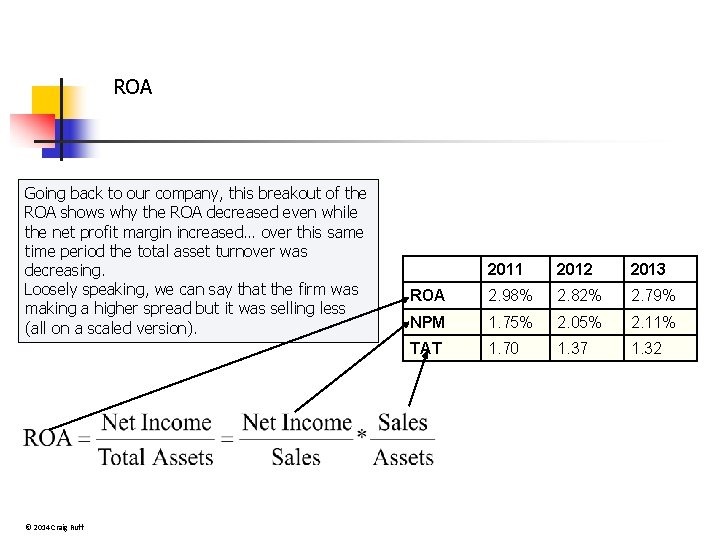

ROA Going back to our company, this breakout of the ROA shows why the ROA decreased even while the net profit margin increased… over this same time period the total asset turnover was decreasing. Loosely speaking, we can say that the firm was making a higher spread but it was selling less (all on a scaled version). © 2014 Craig Ruff 2011 2012 2013 ROA 2. 98% 2. 82% 2. 79% NPM 1. 75% 2. 05% 2. 11% TAT 1. 70 1. 37 1. 32

ROE Now, we turn to the final quest in our mission… the ROE. Remember that the return on equity (ROE) is a very special ratio: it is measuring the return on the owner’s investment in the company. Remember that we are not going through the Du. Pont Analysis just to calculate the ROE. We are doing the analysis to explain what drove the ROE. It is all about the story. © 2014 Craig Ruff

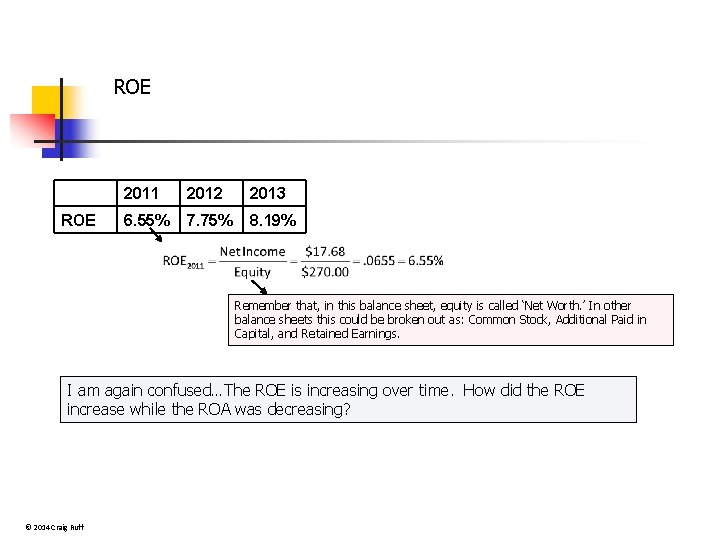

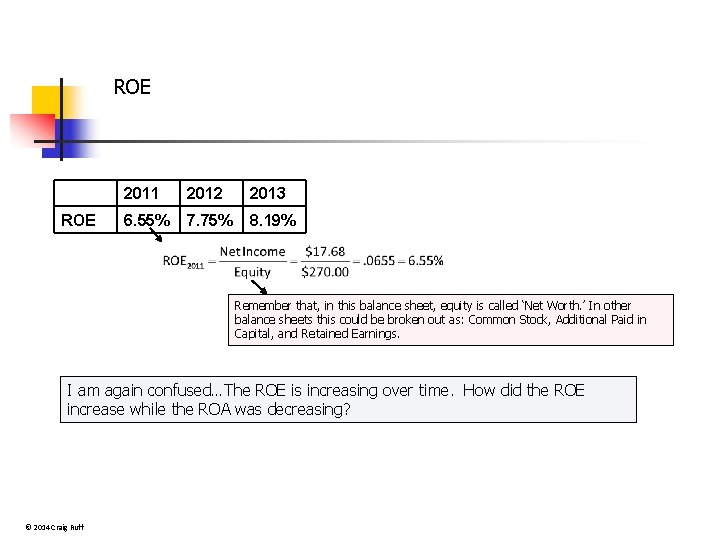

ROE 2011 2012 2013 6. 55% 7. 75% 8. 19% Remember that, in this balance sheet, equity is called ‘Net Worth. ’ In other balance sheets this could be broken out as: Common Stock, Additional Paid in Capital, and Retained Earnings. I am again confused…The ROE is increasing over time. How did the ROE increase while the ROA was decreasing? © 2014 Craig Ruff

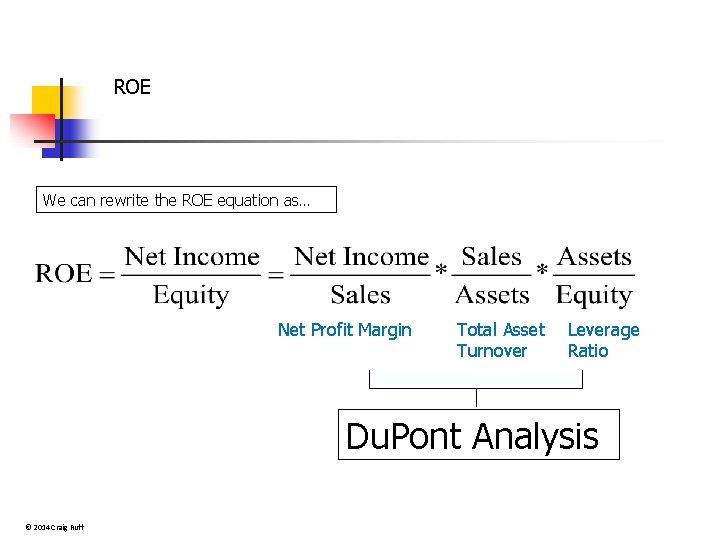

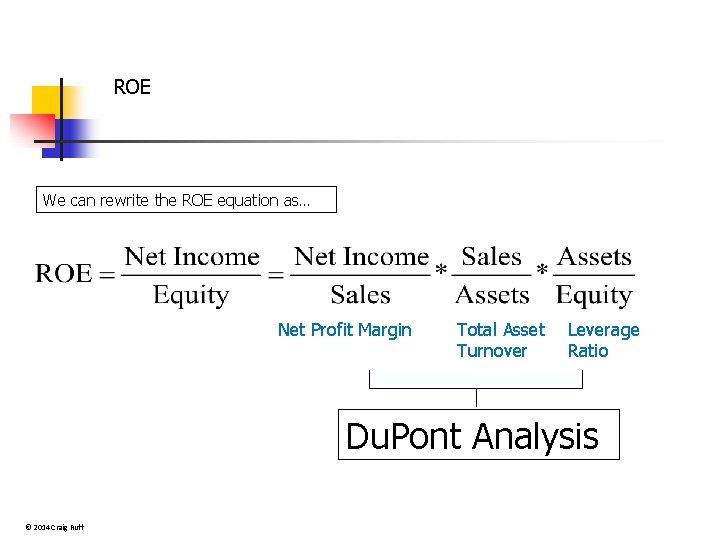

ROE We can rewrite the ROE equation as… Net Profit Margin Total Asset Turnover Leverage Ratio Du. Pont Analysis © 2014 Craig Ruff

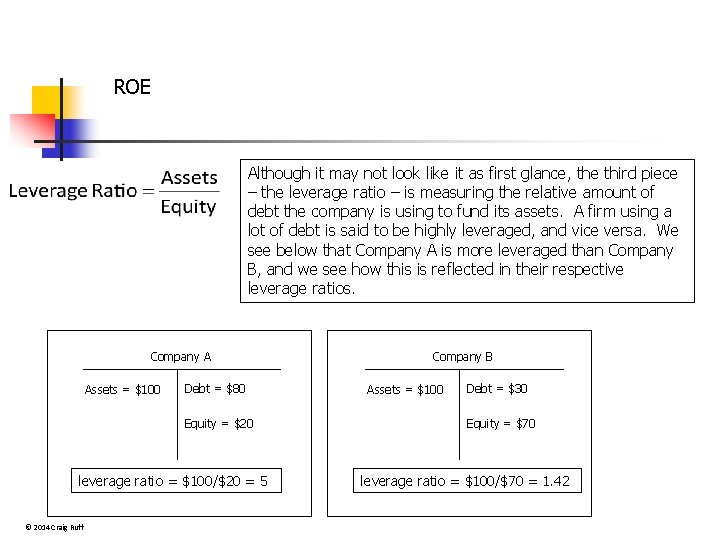

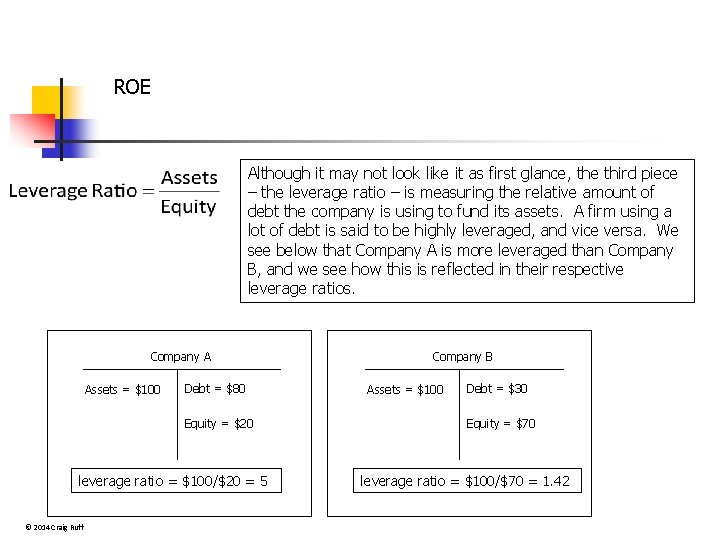

ROE Although it may not look like it as first glance, the third piece – the leverage ratio – is measuring the relative amount of debt the company is using to fund its assets. A firm using a lot of debt is said to be highly leveraged, and vice versa. We see below that Company A is more leveraged than Company B, and we see how this is reflected in their respective leverage ratios. Company A Assets = $100 Debt = $80 Equity = $20 leverage ratio = $100/$20 = 5 © 2014 Craig Ruff Company B Assets = $100 Debt = $30 Equity = $70 leverage ratio = $100/$70 = 1. 42

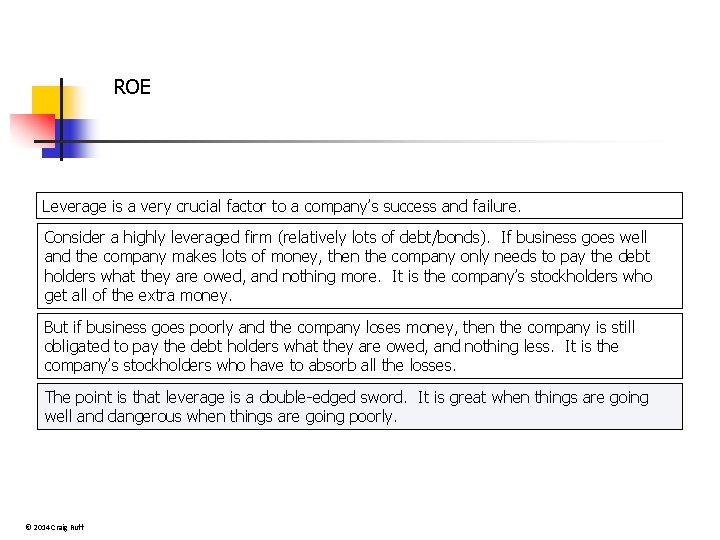

ROE Leverage is a very crucial factor to a company’s success and failure. Consider a highly leveraged firm (relatively lots of debt/bonds). If business goes well and the company makes lots of money, then the company only needs to pay the debt holders what they are owed, and nothing more. It is the company’s stockholders who get all of the extra money. But if business goes poorly and the company loses money, then the company is still obligated to pay the debt holders what they are owed, and nothing less. It is the company’s stockholders who have to absorb all the losses. The point is that leverage is a double-edged sword. It is great when things are going well and dangerous when things are going poorly. © 2014 Craig Ruff

ROE As another way of thinking about this, imagine a company that has borrowed a lot of money by issuing bonds. If so, they will have a relatively large interest obligation. If times are tough, they may not be able to meet that obligation. That will push the company toward default on its bonds and all sorts of trouble. Now imagine that the company had avoided issuing bonds and, instead, issued more equity to raise capital. If so, the company will have a relatively small interest obligation. Here, there is less chance that, if times are tough, the company will not be able to meet its interest obligation. And remember that the company is not obligated to make payments to its stockholders. © 2014 Craig Ruff

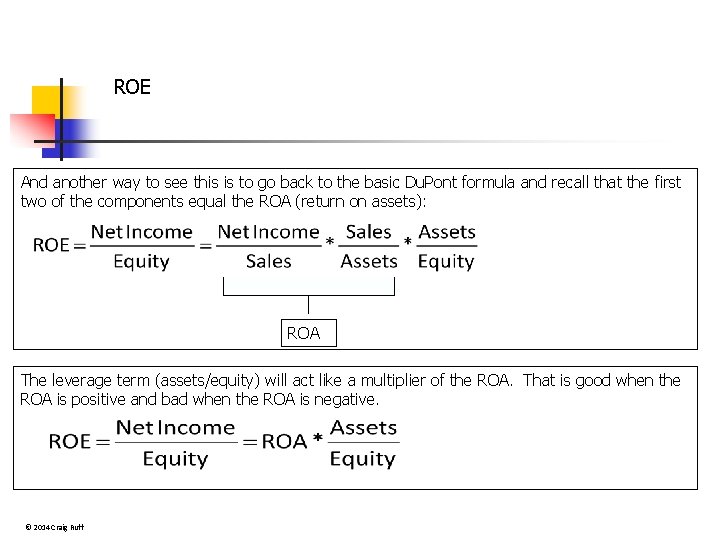

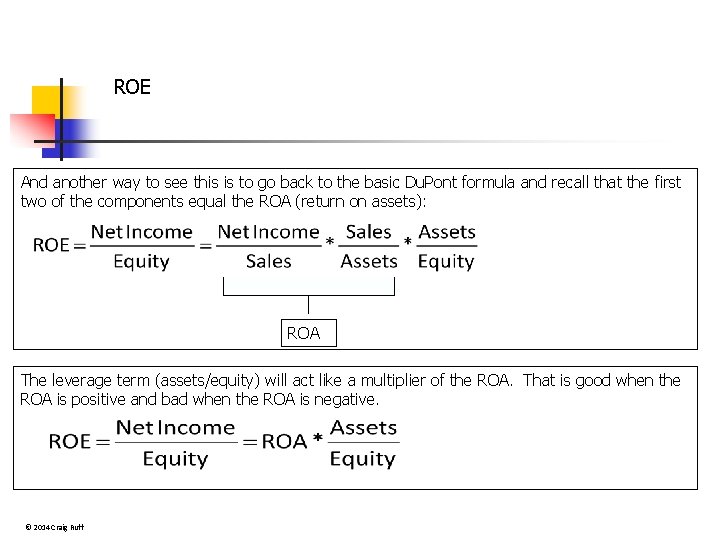

ROE And another way to see this is to go back to the basic Du. Pont formula and recall that the first two of the components equal the ROA (return on assets): ROA The leverage term (assets/equity) will act like a multiplier of the ROA. That is good when the ROA is positive and bad when the ROA is negative. © 2014 Craig Ruff

ROE Again, keep in mind that leverage is a double-edged sword: When things are going well, it magnifies the company’s ROE. But when the ROA is negative, it magnifies that negative return. Even if the ROA is not negative, there are still ‘costs’ to the financial risk associated with a highly leveraged firm: § Routine high interest charges and debt repayment burdens § Little or no ability to borrow in case of an emergency § Too much of management’s time and energies are devoted to worrying about financial problems (such as making sure the company can make the principal or interest payments) rather than devoting time to operations or strategy § Without financial flexibility, there is more uncertainty about coping with future operations or financial problems. © 2014 Craig Ruff

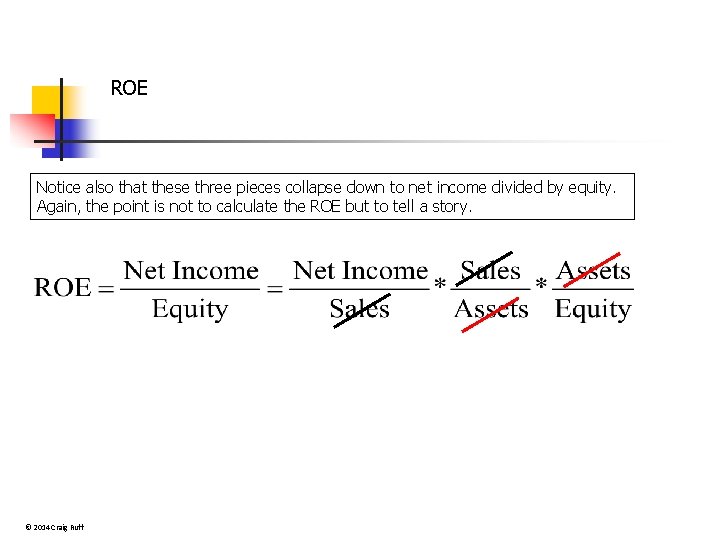

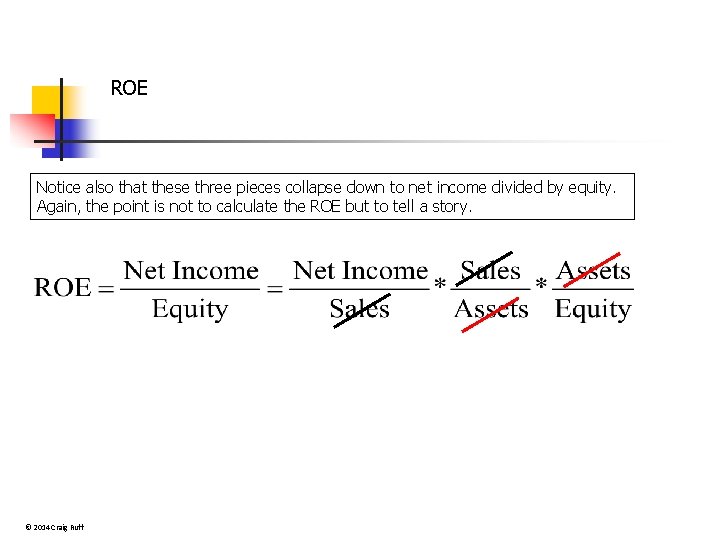

ROE Notice also that these three pieces collapse down to net income divided by equity. Again, the point is not to calculate the ROE but to tell a story. © 2014 Craig Ruff

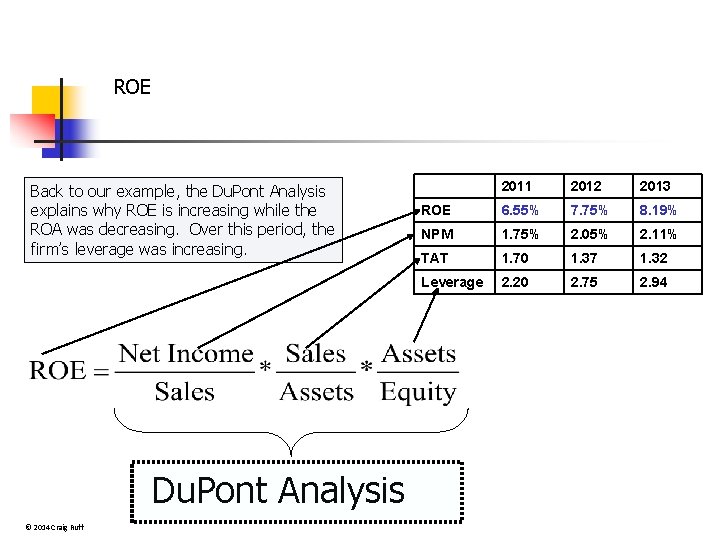

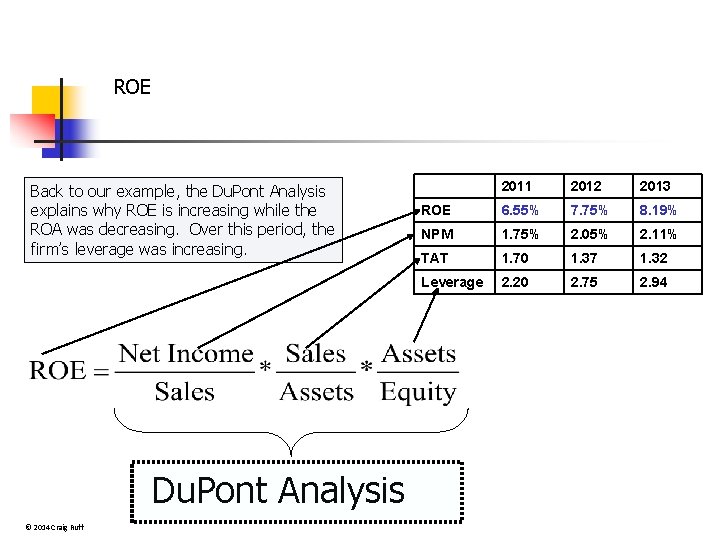

ROE Back to our example, the Du. Pont Analysis explains why ROE is increasing while the ROA was decreasing. Over this period, the firm’s leverage was increasing. Du. Pont Analysis © 2014 Craig Ruff 2011 2012 2013 ROE 6. 55% 7. 75% 8. 19% NPM 1. 75% 2. 05% 2. 11% TAT 1. 70 1. 37 1. 32 Leverage 2. 20 2. 75 2. 94

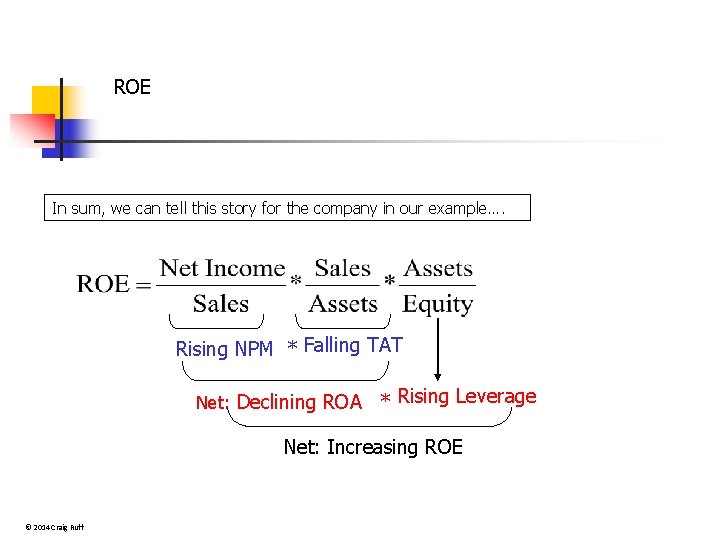

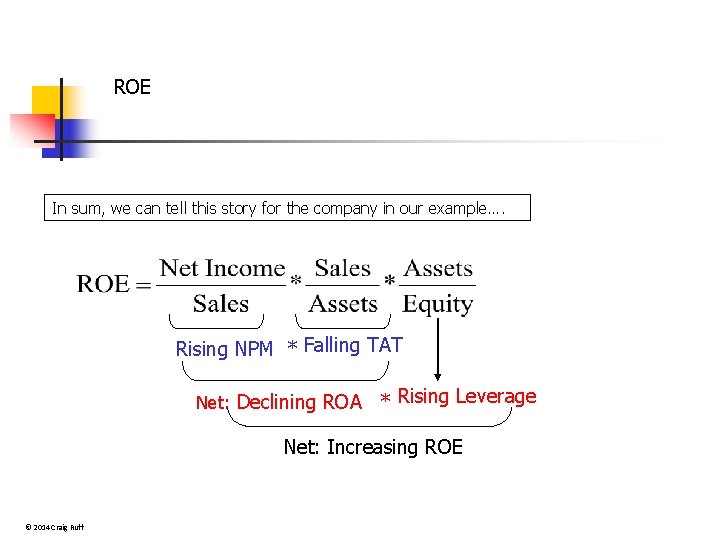

ROE In sum, we can tell this story for the company in our example…. Rising NPM * Falling TAT Net: Declining ROA * Rising Leverage Net: Increasing ROE © 2014 Craig Ruff

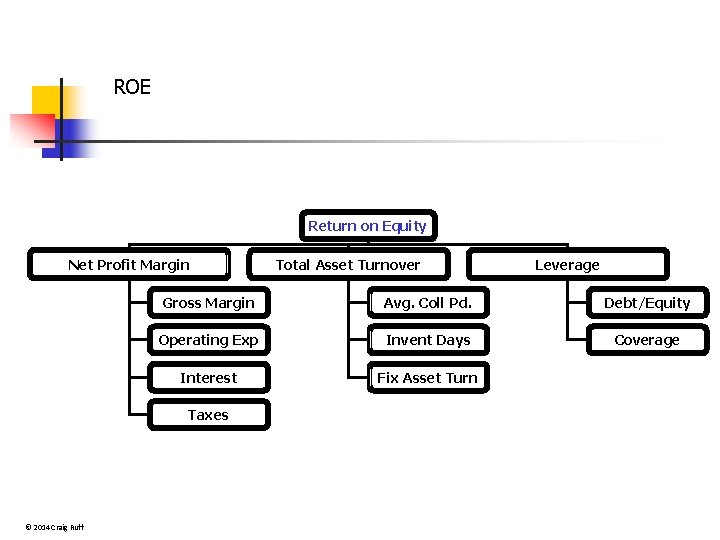

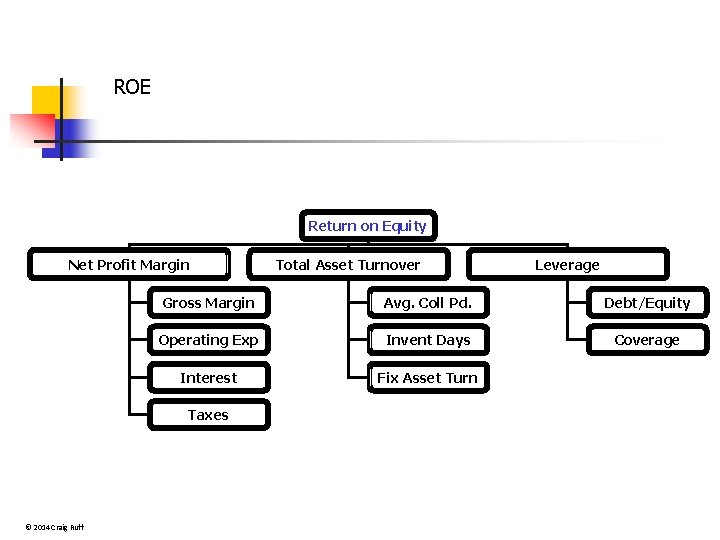

ROE Return on Equity Net Profit Margin Leverage Gross Margin Avg. Coll Pd. Debt/Equity Operating Exp Invent Days Coverage Interest Fix Asset Turn Taxes © 2014 Craig Ruff Total Asset Turnover

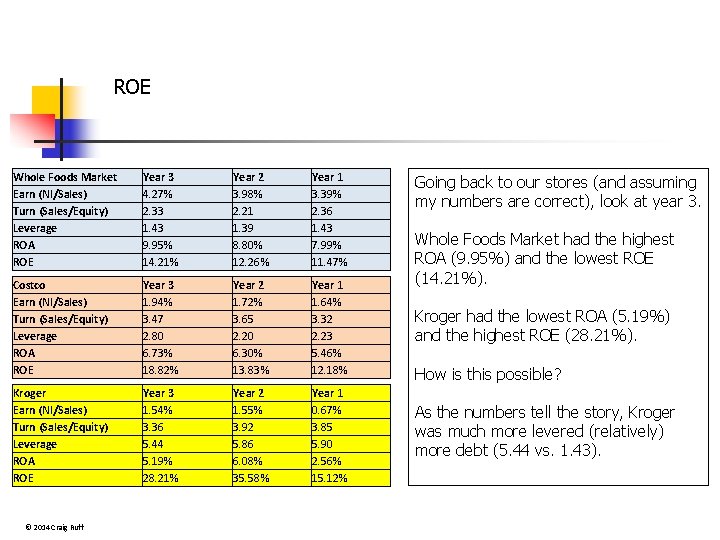

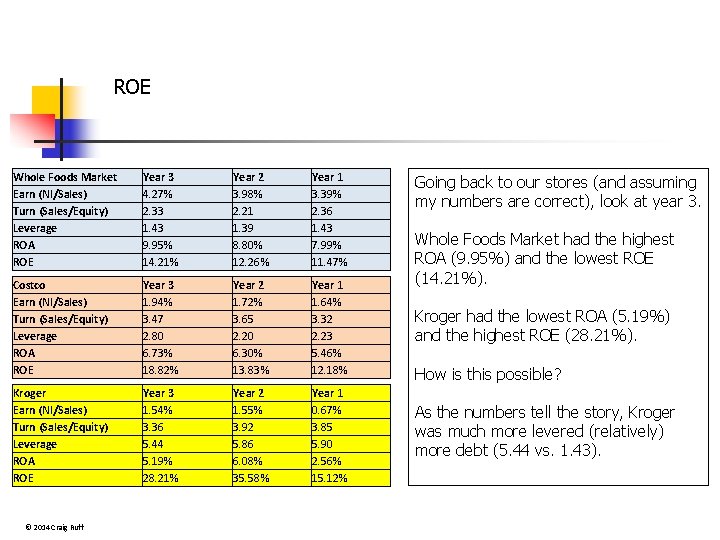

ROE Whole Foods Market Earn (NI/Sales) Turn (Sales/Equity) Leverage ROA ROE Year 3 4. 27% 2. 33 1. 43 9. 95% 14. 21% Year 2 3. 98% 2. 21 1. 39 8. 80% 12. 26% Year 1 3. 39% 2. 36 1. 43 7. 99% 11. 47% Costco Earn (NI/Sales) Turn (Sales/Equity) Leverage ROA ROE Year 3 1. 94% 3. 47 2. 80 6. 73% 18. 82% Year 2 1. 72% 3. 65 2. 20 6. 30% 13. 83% Year 1 1. 64% 3. 32 2. 23 5. 46% 12. 18% Kroger Earn (NI/Sales) Turn (Sales/Equity) Leverage ROA ROE Year 3 1. 54% 3. 36 5. 44 5. 19% 28. 21% Year 2 1. 55% 3. 92 5. 86 6. 08% 35. 58% Year 1 0. 67% 3. 85 5. 90 2. 56% 15. 12% © 2014 Craig Ruff Going back to our stores (and assuming my numbers are correct), look at year 3. Whole Foods Market had the highest ROA (9. 95%) and the lowest ROE (14. 21%). Kroger had the lowest ROA (5. 19%) and the highest ROE (28. 21%). How is this possible? As the numbers tell the story, Kroger was much more levered (relatively) more debt (5. 44 vs. 1. 43).

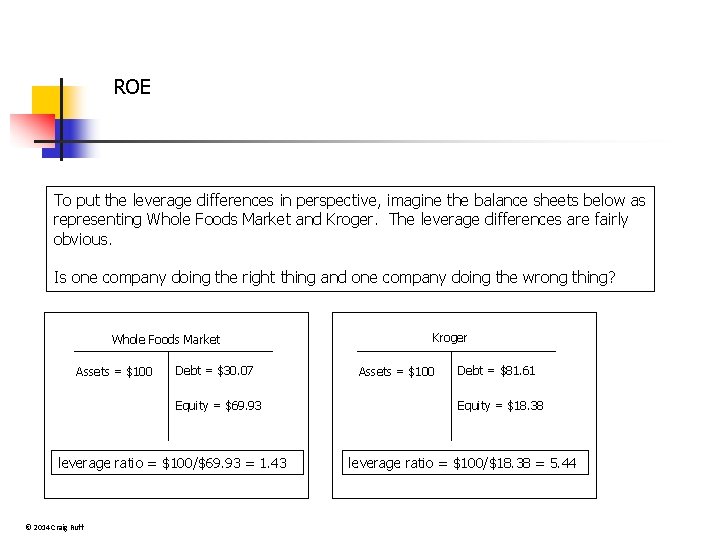

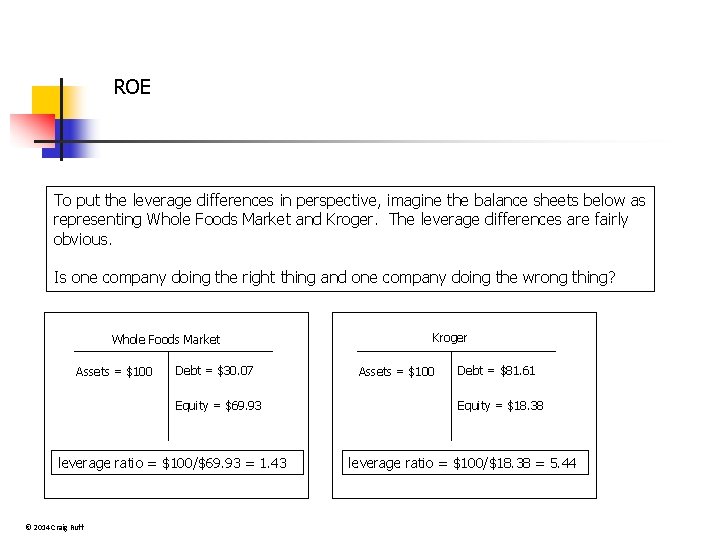

ROE To put the leverage differences in perspective, imagine the balance sheets below as representing Whole Foods Market and Kroger. The leverage differences are fairly obvious. Is one company doing the right thing and one company doing the wrong thing? Whole Foods Market Assets = $100 Debt = $30. 07 Equity = $69. 93 leverage ratio = $100/$69. 93 = 1. 43 © 2014 Craig Ruff Kroger Assets = $100 Debt = $81. 61 Equity = $18. 38 leverage ratio = $100/$18. 38 = 5. 44