Dr Stephen Purcell In the Winters Tale at

![Roland Barthes (19151980) Barthes on theatre: § “[A]s soon as it is revealed, it Roland Barthes (19151980) Barthes on theatre: § “[A]s soon as it is revealed, it](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/012b3adb46edab440780fa43c418065d/image-4.jpg)

- Slides: 28

Dr Stephen Purcell

In the Winter's Tale at the Globe 1611 the 15 of May, Wednesday Observe there how Leontes the king of Sicilia was overcome with jealousy of his wife with the king of Bohemia, his friend that came to see him; and how he contrived his death and would have had his cupbearer to have poisoned, who gave the king of Bohemia warning thereof and fled with him to Bohemia. Remember also how he sent to the Oracle of Apollo and the answer of Apollo, that she was guiltless and that the king was jealous, etc. , and how except the child was found again that was lost, the king should die without issue. … Remember also the rogue that came in all tattered like colt pixie, and how he feigned him sick and to have been robbed of all that he had and how he cozened the poor man of all his money, and after came to the sheepshearer with a pedlar's pack and there cozened them again of all their money. And how he changed apparel with the king of Bohemia his son, and then how he turned courtier, etc. Beware of trusting feigned beggars or fawning felons. From Simon Forman, The Bocke of Plaies and Notes therof per forman for Common Pollicie, 1611, Bodleian Library, Oxford University

Ferdinand de Saussure (18571913) di e( rt h( et h m e Saussure’s concept of the e Sign: n p ht a y sl i c o a nl c e m p a rt k c or er a

![Roland Barthes 19151980 Barthes on theatre As soon as it is revealed it Roland Barthes (19151980) Barthes on theatre: § “[A]s soon as it is revealed, it](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/012b3adb46edab440780fa43c418065d/image-4.jpg)

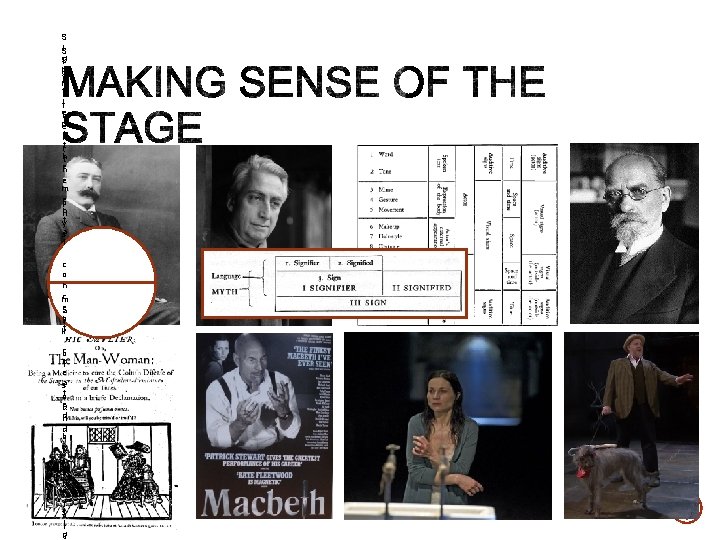

Roland Barthes (19151980) Barthes on theatre: § “[A]s soon as it is revealed, it begins emitting a certain number of messages … at a certain point in the performance, you receive at the same time six or seven items of information (proceeding from the set, the costumes, the lighting, the placing of the actors, their gestures, their speech), but some of these remain (the set, for example) while others change (speech, gesture); what we have, then, is a real informational polyphony, which is what theatricality is: a density of signs. ” (Barthes 1972: 261 -2)

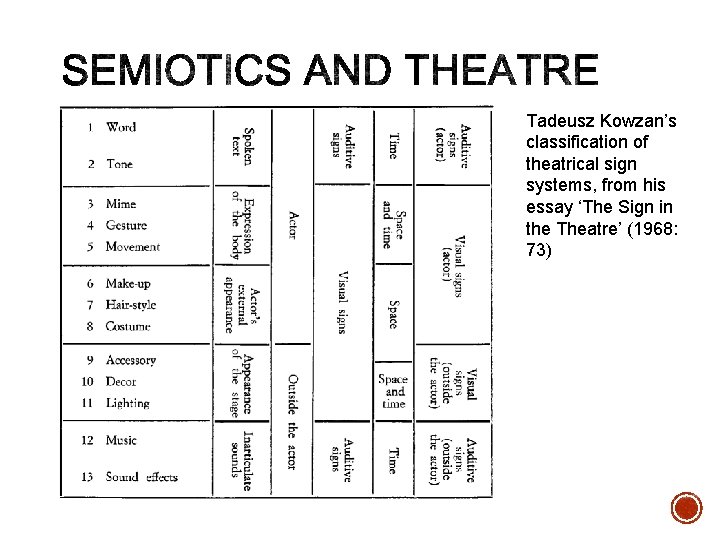

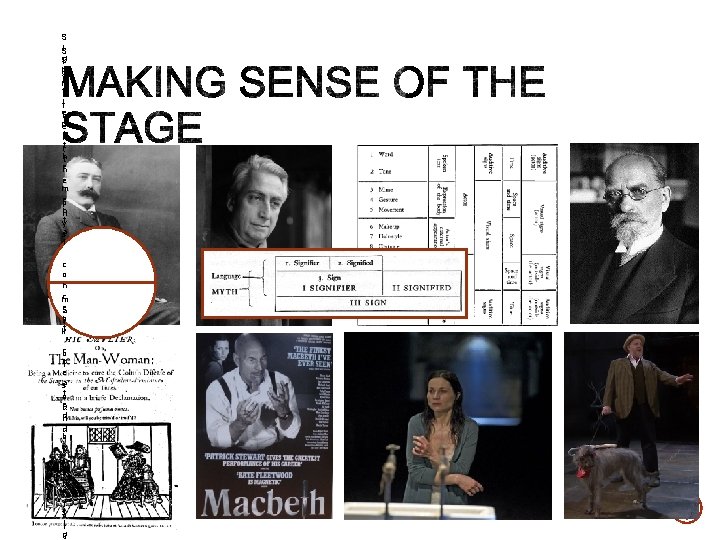

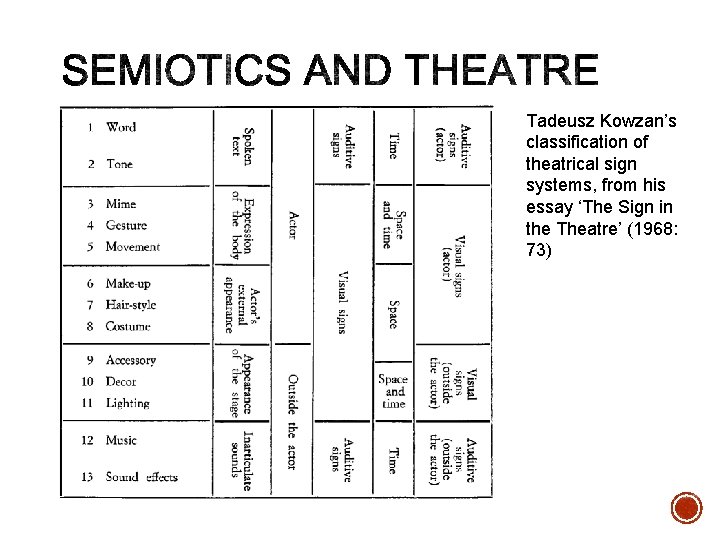

Tadeusz Kowzan’s classification of theatrical sign systems, from his essay ‘The Sign in the Theatre’ (1968: 73)

§ Kowzan distinguishes between “natural signs” and “artificial signs”: § Natural signs are “those whose relation with the thing signified results from the laws of nature alone: e. g. smoke, the sign of fire” (1968: 59); § Artificial signs are “those whose relation with the thing signified relies on a voluntary and more often collective decision” (1968: 59). § “The signs used by theatrical art all belong to the artificial category. They are artificial signs par excellence. …The spectacle transforms natural signs into artificial ones (a flash of lightning), so it can “artificialize” signs. Even if they are only reflexes in life, they become voluntary signs in theater. Even if they have no communicative function in life, they necessarily acquire it on stage. ” (1968: 60)

§ In his essay on the ‘Semiotics of Theatrical Performance’ (1977), Umberto Eco images a scenario in which a drunkard is ‘exposed in a public place by the Salvation Army in order to advertise the advantages of temperance’ (1977: 109): § “As soon as he has been put on the platform and shown to the audience, the drunken man has lost his original nature of “real” body among real bodies. He is no more a world object among world objects-he has become a semiotic device; he is now a sign. A sign, according to [C. S. ] Peirce, is something that stands to somebody for something else in some respect or capacity—a physical presence referring back to something absent. What is our drunken man referring back to? To a drunken man. But not to the drunk who he is, but to a drunk. The present drunkinsofar as he is the member of a class—is referring us back to the class of which he is a member. He stands for the category he belongs to. ” (1977: 110)

§ In his article ‘When We Talk of Horses: Or, what do we see when we see a play? ’, Dan Rebellato argues against the notion that drama is “illusionistic” (2009: 17): § “These views of ‘dramatic theatre’ are wrong; representational theatre is not illusionistic. In illusions we have mistaken beliefs about what we are seeing. No sane person watching a play believes that what is being represented before them is actually happening. We know we are watching people representing something else; we are aware of this, never forget it, and rarely get confused. ” (2009: 18) § “I want to suggest that ‘David Tennant is Hamlet’ in much the same way that love is a battlefield and all the world’s a stage, In other words, David Tennant is a metaphor for Hamlet. In metaphor, we are invited to see (or think about) one thing in terms of another thing. There is no make-believe involved, no amassing of propositional information, no artful subtraction from one to create the image of the other. We know the two objects are quite separate, but we think of one in terms of the other. ” (2009: 25)

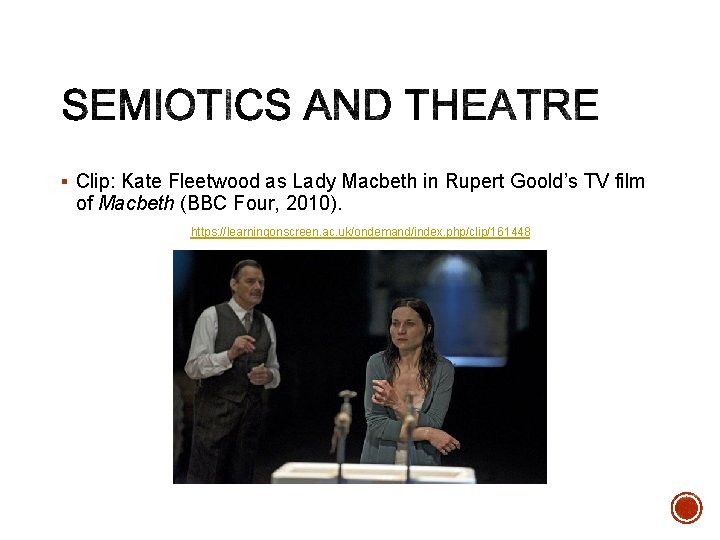

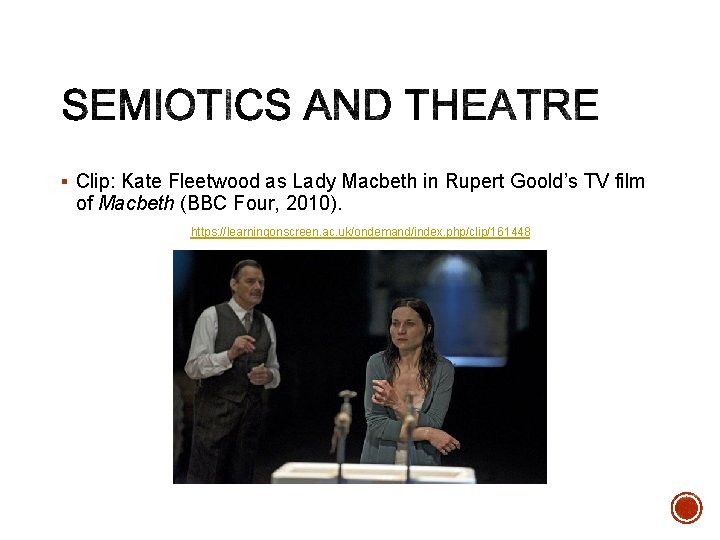

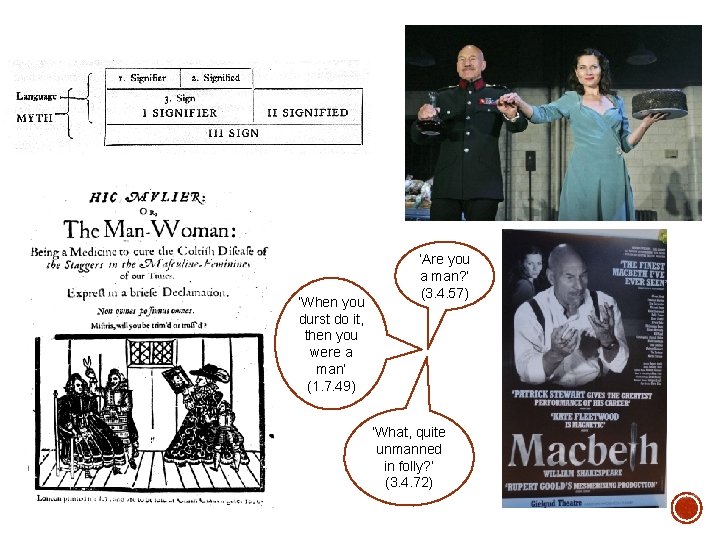

§ Clip: Kate Fleetwood as Lady Macbeth in Rupert Goold’s TV film of Macbeth (BBC Four, 2010). https: //learningonscreen. ac. uk/ondemand/index. php/clip/161448

§ In his book The Semiotics of Performance, Marco De Marinis proposes the concept of ‘The Model Spectator’, “a strategy of interpretive cooperation foreseen by, and variously inscribed in, the performance text (like a ‘guideline for reading’)” (1993: 166 -7): § “…the Model Spectator is one who recognizes all the codes of the performance text in question, reconstructing the entire structure of the performance text in the way that is textually proposed by the sender” (1993: 167); § He distinguishes between “closed” performances, which “predict [a] specific addressee”, and “open” ones, which are “intended to reach a fairly nonspecific addressee” and “do not foresee a rigidly predetermined interpretive process as a requirement for their success, but allow the audience a variable margin of freedom deciding up to what point they can control the cooperation”(1993: 168 -9).

§ Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in this Class? : § “Interpretive communities are made up of those who share interpretive strategies not for reading (in the conventional sense) but for writing texts, for constituting their properties and assigning their intentions. In other words, these strategies exist prior to the act of reading and therefore determine the shape of what is read rather than, as is usually assumed, the other way around. … This, then, is the explanation both for the stability of interpretation among readers (they belong to the same community) and for the regularity with which a single reader will employ different interpretive strategies and thus make different texts (he belongs to different communities). ” (1980: 171)

§ Susan Bennett, Theatre Audiences: § “…the outer frame contains all those cultural elements which create and inform theatrical event. The inner frame contains the dramatic production in a particular playing space. The audience’s role is carried out within these two frames and, perhaps most importantly, at their points of intersection. It is the interactive relations between audience and stage, spectator and spectator which constitute production and reception, and which cause the inner and outer frames to converge for the creation of a particular experience. ” (1997: 139) § “In the Western theatre audience that this study assumes… it is the tension between the inner frame of the fictional stage world, the audience’s moment by moment perception of that in the experience of a social group, and the outer frame of community (cultural construction and horizons of expectations) which determine the nature and satisfaction of the interpretive process. ” (1997: 156)

§ Nick Abercrombie and Brian Longhurst, Audiences: § They argue that what they call the “Incorporation/Resistance paradigm” in audience studies is exemplified by Stuart Hall’s influential essay ‘Encoding/Decoding’ (1980), in which readings are either “dominant”, “oppositional” or “negotiated”. § “The Incorporation/Resistance paradigm … defines the problem of audience research as whether audience members are incorporated in the dominant ideology by their participation in media activity or whether, to the contrary, they are resistant to that incorporation. … These are the questions that are permitted by the paradigm; other sorts of questions about the audience are almost un-askable or, at least, are not treated as serious or interesting contributions. ” (1993: 15)

§ Clip: Kate Fleetwood as Lady Macbeth in Rupert Goold’s TV film of Macbeth (BBC Four, 2010). https: //learningonscreen. ac. uk/ondemand/index. php/clip/161448

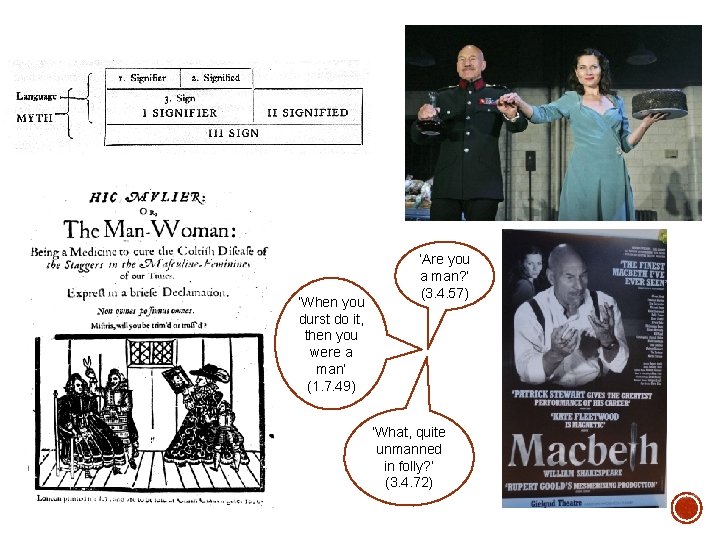

‘When you durst do it, then you were a man’ (1. 7. 49) ‘Are you a man? ’ (3. 4. 57) ‘What, quite unmanned in folly? ’ (3. 4. 72)

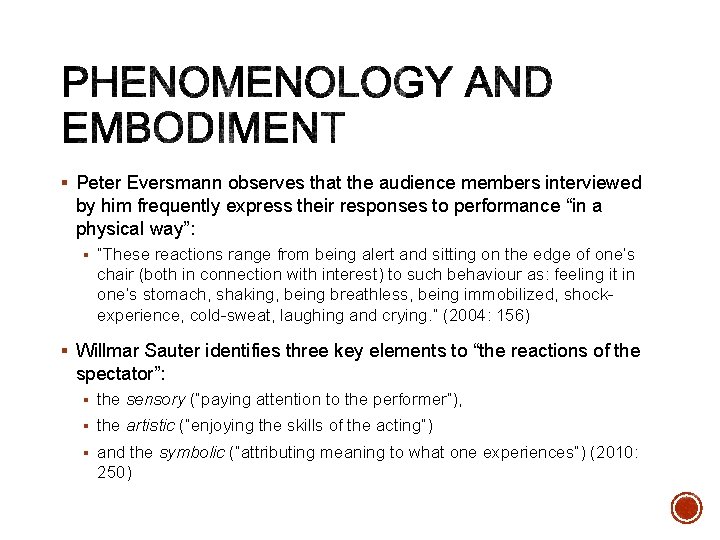

§ Peter Eversmann observes that the audience members interviewed by him frequently express their responses to performance “in a physical way”: § “These reactions range from being alert and sitting on the edge of one’s chair (both in connection with interest) to such behaviour as: feeling it in one’s stomach, shaking, being breathless, being immobilized, shockexperience, cold-sweat, laughing and crying. ” (2004: 156) § Willmar Sauter identifies three key elements to “the reactions of the spectator”: § the sensory (“paying attention to the performer”), § the artistic (“enjoying the skills of the acting”) § and the symbolic (“attributing meaning to what one experiences”) (2010: 250)

Edmund Husserl (18591938) § Bert O. States: § “The phenomenological approach offers a critique of what cosmological physics might call “the first four seconds” of the perceptual explosion. It is beside the point to claim that the first four seconds are always tainted by a lifetime of perceptual habit within a narrow cultural frame. It is only the moment of absorption that counts: what conditions the moment and what follows it are somebody else’s business. ” (2007: 27)

§ Clip: Roger Morlidge as Launce and Mossup as Crab in Simon Godwin’s production of The Two Gentlemen of Verona (Royal Shakespeare Company, 2014). https: //www. digitaltheatreplus. com/education/collections/rsc/the-two-gentlemen-of-verona#production-videos-key -scene [Act 2 scene 3]

§ Bert O. States, Great Reckonings in Little Rooms: § “In productions of The Two Gentlemen of Verona Launce’s dog Crab usually steals the show by simply being itself. Anything the dog does – ignoring Launce, yawning, wagging its tail, forgetting its “lines” – becomes hilarious or cute because it is doglike. … We have an intersection of two independent and self-contained phenomenal chains – natural animal behaviour and culturally programmed human behaviour. The “flash” at the intersection, equivalent to the punch line of a joke, comes in our attributing human qualities to the dog (a wagging tail is a signal that the dog has understood; a yawn is a signal that it is bored); but beneath this is our conscious awareness that the dog is a real dog reacting to what, for it, is simply another event in its dog’s life. ” (1985: 33) § “…one feels the shudder of its refusal to settle into the illusion. One might say that the force of its significations, felt all at once, overloads the artistic circuit, as in the filaments of those early light bulbs that glowed intensely with the first surge of power; it is perceived not as a signifier but as a signified, though phenomenologically speaking these words now pertain to an alien vocabulary…” (1985: 37)

§ Bert O. States, ‘The Phenomenological Attitude’: § “It is my sense that as long as semiotics holds the notion that all things (on a stage, for example) can be fully treated as signs – that is, as transparent codes of socialized meaning – it cannot adopt the phenomenological attitude in any “eminent” way. Husserl is quite plain on this point: “The spatial thing which we see is … perceived, we are consciously aware of it as given in its embodied form. We are not given an image or a sign in its place. We must not substitute the consciousness of a sign or an image for a perception. ” Of course, Husserl is not talking here about perception as it occurs in theater where we are confronted by images and signs. But in theater something is also itself as well … though the bird in the feeder may be a sign of spring, it is not the sign of a bird. ” (2007: 31 -2)

§ Bruce R. Smith, Phenomenal Shakespeare: § “Theatrical phenomena versus social facts, appearance versus reality, imaginative joy versus rational analysis: must we choose between these binaries? Why can’t we embrace both? ” (2010: 6) § “It is my sense of touch that allows me to project what I can feel with my body here onto his body there and, reversing direction, to take what I see happening to his body there and feel it with my body here. ” (2010: 151)

§ Paula M. Niedenthal, Lawrence W. Barsalou, François Ric and Silvia Krauth-Gruber, ‘Embodiment in the Acquisition and Use of Emotion Knowledge’: § (1) Individuals embody other people’s emotional behaviour; § (2) embodied emotions produce corresponding subjective emotional states in the individual; § (3) imagining other people and events also produces embodied emotions and corresponding feelings; and § (4) embodied emotions mediate cognitive responses. (2005: 22)

§ Pierre Jacob and Marc Jeannerod on visual percepts and visuomotor representations: § “The former serves as input to higher human cognitive processes, including memory, categorization, conceptual thought and reasoning. The latter is at the service of human action. From the standpoint of our version of the ‘two visual systems’ hypothesis, vision serves two masters: thinking about, and acting upon, the world. ” (2003: 45)

§ Bruce Mc. Conachie, Engaging Audiences: § “Having borrowed the assumptions (if not always the methodology) of semiotics, many academic critics and historians of theatre describe audience experience as a version of “reading. ” From the point of view of cognitive studies, however, there are fundamental differences between readers making sense of signs on a printed page and the mostly non-symbolic activity of spectator cognition. ” (2008: 3)

S Si gi n g ni fi fi ei d e r( (t ht e h e m e p n h yt a s li c c a ol n c m e a pr kt c o rr e a s ot e u d n d b y u s et h d e f s o ri g

§ Abercrombie, Nicholas & Brian Longhurst (1998) Audiences: A Sociological Theory of Performance and Imagination, London: Sage Publications. § Barthes, Roland (1972) ‘Literature and Signification: Answers to a Questionnaire in Tel Quel’, in Critical Essays, trans. Richard Howard, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 261 -79. § Bennett, Susan (1997) Theatre Audiences: A Theory of Production and Reception, London: Routledge. § Case, Sue-Ellen (1988) Feminism and Theatre, New York: Methuen. § De Marinis, Marco (1993) The Semiotics of Performance, trans. Áine O’Healy, Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. § Eco, Umberto (1977) ‘Semiotics of Theatrical Performance’, The Drama Review 21: 1, 107 -17. § Elam, Keir (2002) The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama, London: Methuen. § Eversmann, Peter (2004) ‘The Experience of the Theatrical Event’ in Vicky Ann Cremona, Peter Eversmann, Hans van Maanen, Willmar Sauter & John Tulloch [eds] Theatrical Events: Borders, Dynamics, Frames, Amsterdam & New York: Rodopi, 139 -74. § Fauconnier, Gilles & Mark Turner (2002) The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, New York: Basic Books.

§ Fish, Stanley (1980) Is There a Text in this Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities, Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press. § Gallese, Vittorio, Luciano Fadiga, Leonardo Fogassi & Giacomo Rizzolatti (1996) ‘Action Recognition in the Premotor Cortex’, Brain 119, 593 -609. § Hall, Stuart (1980) ‘Encoding/Decoding’, in Stuart Hall, Dorothy Hobson, Andrew Lowe & Paul Willis [eds] Culture, Media, Language, London: Hutchinson, 128 -38. § Jacob, Pierre & Marc Jeannerod (2003) Ways of Seeing: The Scope and Limits of Visual Cognition, Oxford: Oxford University Press. § Jardine, Lisa (1983) Still Harping on Daughters, Women and Drama in the Age of Shakespeare, Brighton: Harvester Press. § Kowzan, Tadeusz (1968) ‘The Sign in the Theatre: An Introduction to the Semiology of the Art of the Spectacle’, trans. Simon Pleasance, Diogenes 16, 52 -80. § Mc. Conachie, Bruce (2008) Engaging Audiences: A Cognitive Approach to Spectating in the Theatre, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. § Niedenthal, Paula M. , Lawrence W. Barsalou, François Ric & Silvia Krauth-Gruber (2005) ‘Embodiment in the Acquisition and Use of Emotion Knowledge’ in Lisa Feldman Barrett, Paula M. Niedenthal & Piotr Winkielman [eds] Emotion and Consciousness, New York & London: Guilford Press, 21 -50.

§ Ralley, Richard & Roy Connolly (2010) ‘In Front of Our Eyes: Presence and the Cognitive Audience’, About Performance 10, 51 -66. § Rebellato, Dan (2009) ‘When We Talk of Horses: Or, what do we see when we see a play? ’, Performance Research 14: 1, 17 -28. § Saussure, Ferdinand de (1959) Course in General Linguistics, ed. Charles Bally, Albert Sechehaye & Albert Riedlinger, trans. Wade Baskin, New York: Mc. Graw-Hill. § Sauter, Willmar (2010) ‘Thirty Years of Reception Studies: Empirical, Methodological and Theoretical Advances’, About Performance 10, 241 -63. § Smith, Bruce R. (2010) Phenomenal Shakespeare, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. § States, Bert O. (1985) Great Reckonings in Little Rooms: On the Phenomenology of Theatre, Berkeley: University of California Press. § States, Bert O. (2007) ‘The Phenomenological Attitude’, in Janelle G. Reinelt & Joseph R. Roach [eds] Critical Theory and Performance (2 nd edn. ), Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 26 -36. § This lecture is based on Chapter 2 of my own 2013 book, Shakespeare and Audience in Practice, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 27 -42.