Claims Evidence Analysis Across the Secondary MSHS Curriculum

- Slides: 27

Claims, Evidence, Analysis Across the Secondary (MS/HS) Curriculum Preparing students to write text-based arguments

The Power of a School-wide Focus Claims, Evidence, Analysis • The thinking that supports argumentation is new and complex; we can’t wait till we write “the argument piece” to learn how to think like an opinion writer. It needs to be part of the knowledge we BRING to the piece, not new skills that we must orchestrate while we are researching and writing about a topic. • We therefore must layer the teaching of these skills in smaller ways, through notebook entries and quick drafts, providing feedback to students that helps them master a few skills at a time rather than expecting them to integrate multiple new skills simultaneously. • Through Mini-units, we are not trying to teach THE argument paper, but rather teach and practice discrete argument moves. Students may later select from several of these short drafts to develop and revise a longer argument piece. Standards tell us what students must be able to do, but not how to do that; standards are missing the techniques that get us to claim and evidence. These mini-units provide those techniques. • We also must teach and practice making claims and using evidence in every content area, all year long, if students are to become proficient in argument writing.

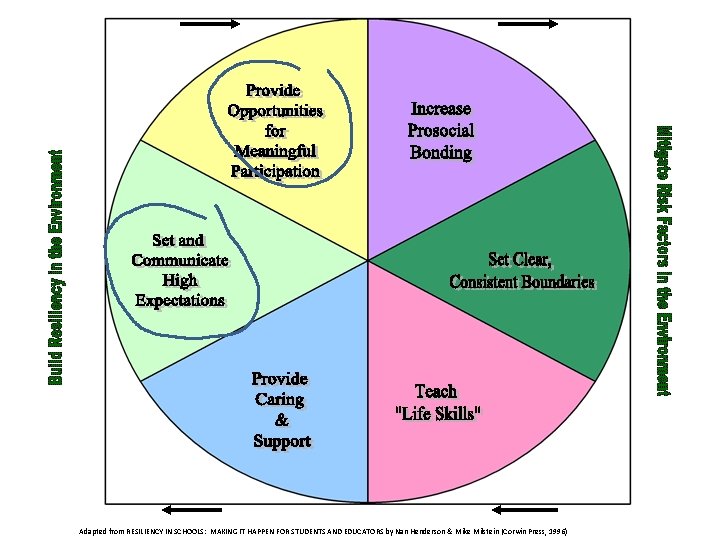

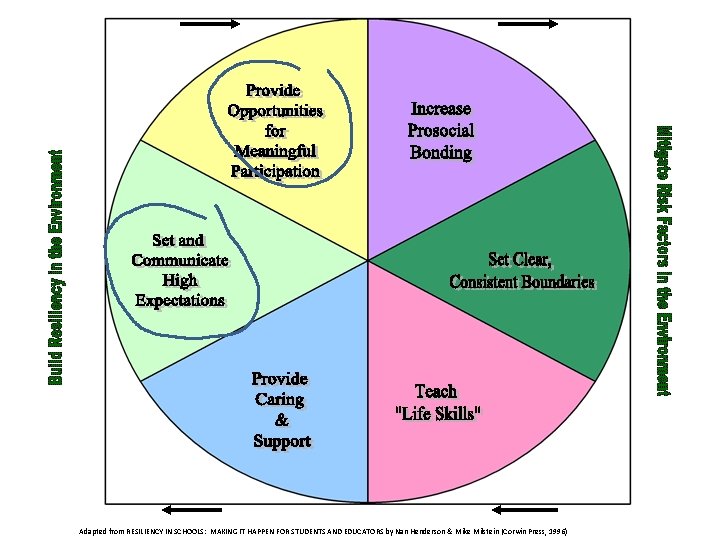

The Power of a School-wide Focus Resiliency/Stamina • In a school where writing scores have been persistently low or stagnant, resiliency research provides an effective lens through which to plan work with students and teachers. • Students and teachers must believe to achieve. – School work is hard, but we can build our stamina as readers and writers through multiple short drafts. – High standards + support is feasible in our classrooms. Formative assessment and focused feedback lifts the quality of student work.

Adapted from RESILIENCY IN SCHOOLS: MAKING IT HAPPEN FOR STUDENTS AND EDUCATORS by Nan Henderson & Mike Milstein (Corwin Press, 1996)

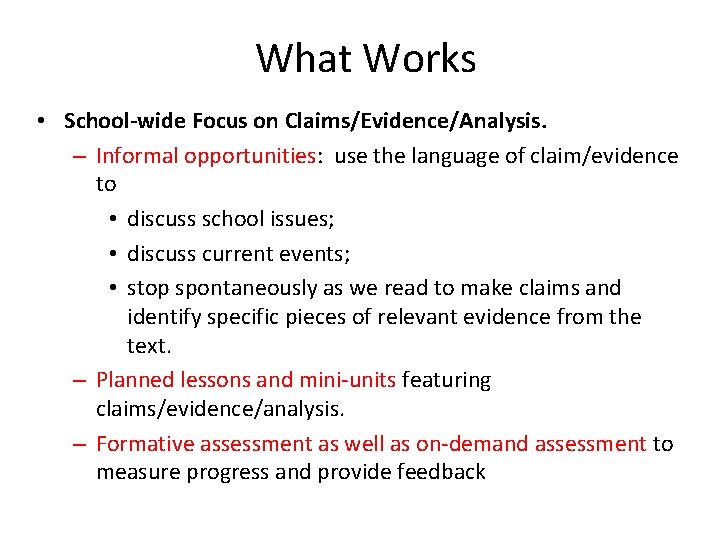

What Works • School-wide Focus on Claims/Evidence/Analysis. – Informal opportunities: use the language of claim/evidence to • discuss school issues; • discuss current events; • stop spontaneously as we read to make claims and identify specific pieces of relevant evidence from the text. – Planned lessons and mini-units featuring claims/evidence/analysis. – Formative assessment as well as on-demand assessment to measure progress and provide feedback

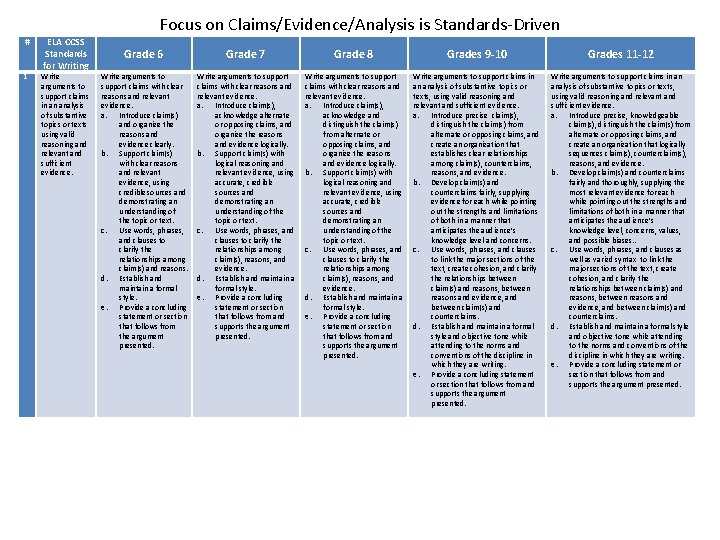

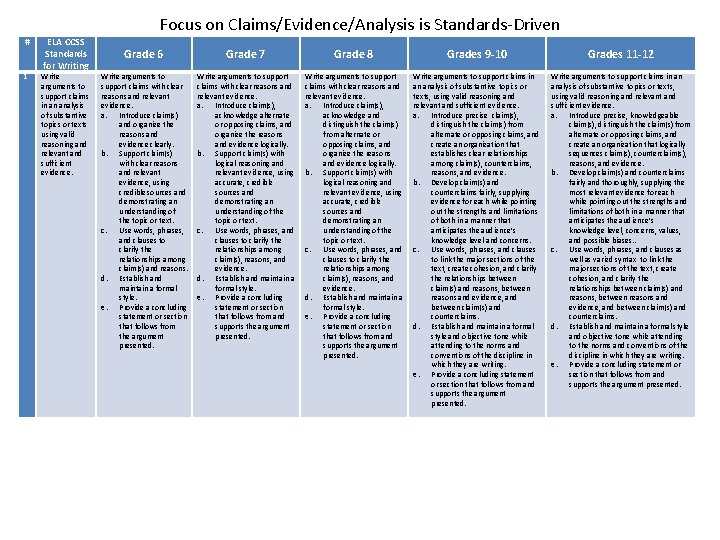

Focus on Claims/Evidence/Analysis is Standards-Driven # 1 ELA CCSS Standards for Writing Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Grades 9 -10 Grades 11 -12 Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. a. Introduce claim(s) and organize the reasons and evidence clearly. b. Support claim(s) with clear reasons and relevant evidence, using credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to clarify the relationships among claim(s) and reasons. d. Establish and maintain a formal style. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from the argument presented. Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. a. Introduce claim(s), acknowledge alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically. b. Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to clarify the relationships among claim(s), reasons, and evidence. d. Establish and maintain a formal style. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. a. Introduce claim(s), acknowledge and distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically. b. Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to clarify the relationships among claim(s), reasons, and evidence. d. Establish and maintain a formal style. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. a. Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. b. Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level and concerns. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims. d. Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. a. Introduce precise, knowledgeable claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that logically sequences claim(s), counterclaim(s), reasons, and evidence. b. Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly and thoroughly, supplying the most relevant evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases. . c. Use words, phrases, and clauses as well as varied syntax to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims. d. Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented.

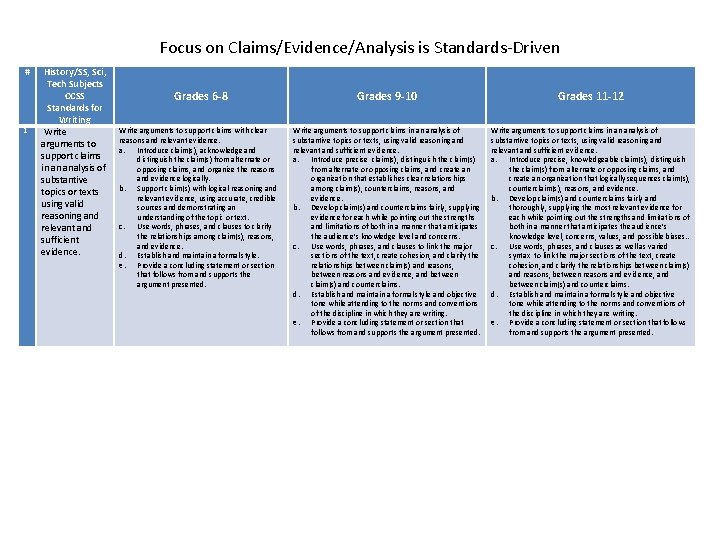

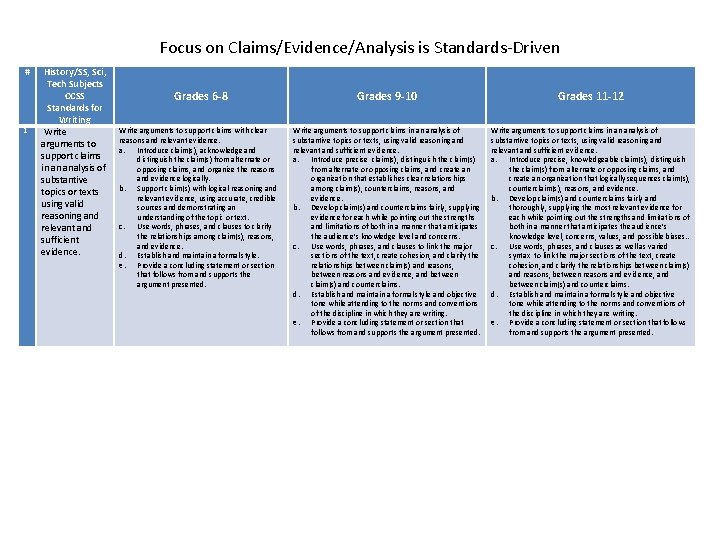

Focus on Claims/Evidence/Analysis is Standards-Driven # 1 History/SS, Sci, Tech Subjects CCSS Standards for Writing Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. Grades 6 -8 Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. a. Introduce claim(s), acknowledge and distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and organize the reasons and evidence logically. b. Support claim(s) with logical reasoning and relevant evidence, using accurate, credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to clarify the relationships among claim(s), reasons, and evidence. d. Establish and maintain a formal style. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. Grades 9 -10 Grades 11 -12 Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. a. Introduce precise claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that establishes clear relationships among claim(s), counterclaims, reasons, and evidence. b. Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly, supplying evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level and concerns. c. Use words, phrases, and clauses to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims. d. Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented. Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence. a. Introduce precise, knowledgeable claim(s), distinguish the claim(s) from alternate or opposing claims, and create an organization that logically sequences claim(s), counterclaim(s), reasons, and evidence. b. Develop claim(s) and counterclaims fairly and thoroughly, supplying the most relevant evidence for each while pointing out the strengths and limitations of both in a manner that anticipates the audience’s knowledge level, concerns, values, and possible biases. . c. Use words, phrases, and clauses as well as varied syntax to link the major sections of the text, create cohesion, and clarify the relationships between claim(s) and reasons, between reasons and evidence, and between claim(s) and counterclaims. d. Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing. e. Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from and supports the argument presented.

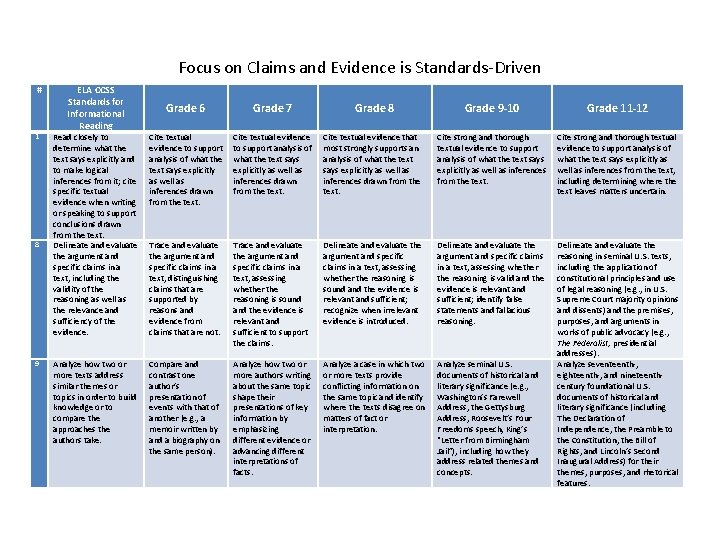

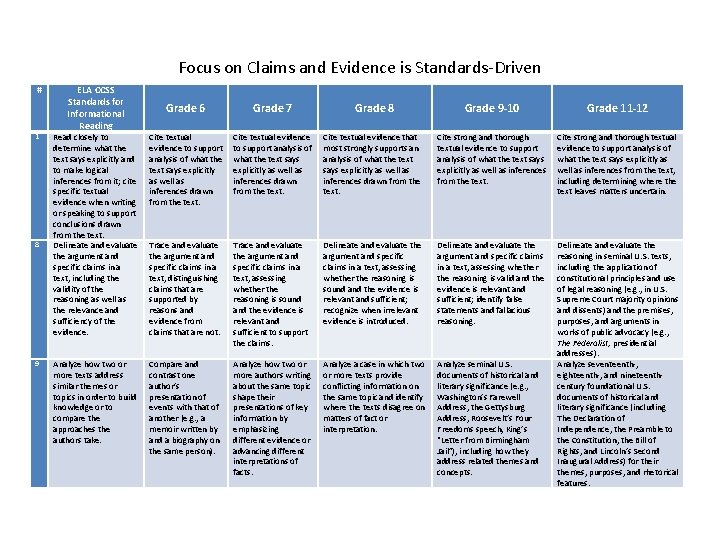

Focus on Claims and Evidence is Standards-Driven # 1 8 9 ELA CCSS Standards for Informational Reading Grade 6 Grade 7 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, distinguishing claims that are supported by reasons and evidence from claims that are not. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with that of another (e. g. , a memoir written by and a biography on the same person). Grade 8 Grade 9 -10 Grade 11 -12 Cite textual evidence that most strongly supports an analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences from the text, including determining where the text leaves matters uncertain. Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient to support the claims. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is sound and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; recognize when irrelevant evidence is introduced. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, assessing whether the reasoning is valid and the evidence is relevant and sufficient; identify false statements and fallacious reasoning. Analyze how two or more authors writing about the same topic shape their presentations of key information by emphasizing different evidence or advancing different interpretations of facts. Analyze a case in which two or more texts provide conflicting information on the same topic and identify where the texts disagree on matters of fact or interpretation. Analyze seminal U. S. documents of historical and literary significance (e. g. , Washington’s Farewell Address, the Gettysburg Address, Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms speech, King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail”), including how they address related themes and concepts. Delineate and evaluate the reasoning in seminal U. S. texts, including the application of constitutional principles and use of legal reasoning (e. g. , in U. S. Supreme Court majority opinions and dissents) and the premises, purposes, and arguments in works of public advocacy (e. g. , The Federalist, presidential addresses). Analyze seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenthcentury foundational U. S. documents of historical and literary significance (including The Declaration of Independence, the Preamble to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address) for their themes, purposes, and rhetorical features.

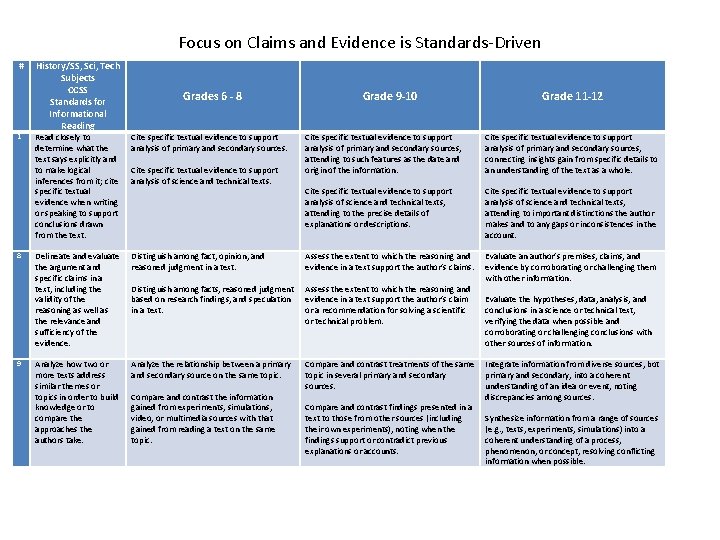

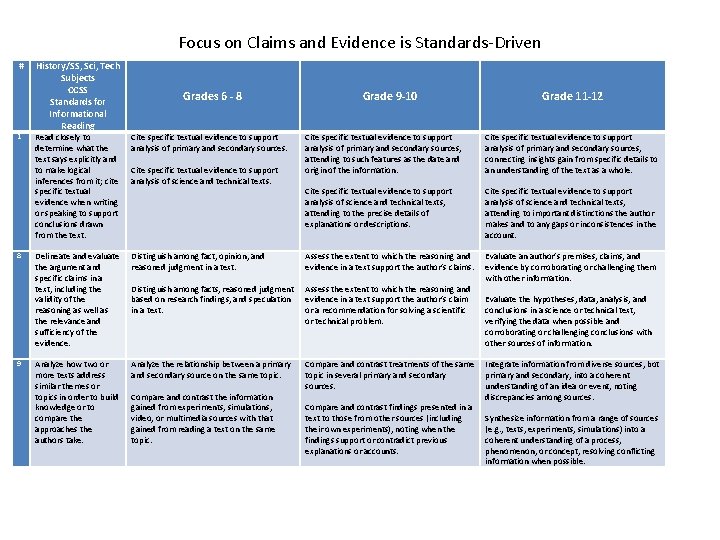

Focus on Claims and Evidence is Standards-Driven # 1 8 9 History/SS, Sci, Tech Subjects CCSS Standards for Informational Reading Grades 6 - 8 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take. Grade 9 -10 Grade 11 -12 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, attending to such features as the date and origin of the information. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gain from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of science and technical texts, attending to the precise details of explanations or descriptions. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of science and technical texts, attending to important distinctions the author makes and to any gaps or inconsistences in the account. Distinguish among fact, opinion, and reasoned judgment in a text. Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claims. Distinguish among facts, reasoned judgment based on research findings, and speculation in a text. Assess the extent to which the reasoning and evidence in a text support the author’s claim or a recommendation for solving a scientific or technical problem. Evaluate an author’s premises, claims, and evidence by corroborating or challenging them with other information. Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources. Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of science and technical texts. Compare and contrast the information gained from experiments, simulations, video, or multimedia sources with that gained from reading a text on the same topic. Compare and contrast findings presented in a text to those from other sources (including their own experiments), noting when the findings support or contradict previous explanations or accounts. Evaluate the hypotheses, data, analysis, and conclusions in a science or technical text, verifying the data when possible and corroborating or challenging conclusions with other sources of information. Integrate information from diverse sources, bot primary and secondary, into a coherent understanding of an idea or event, noting discrepancies among sources. Synthesize information from a range of sources (e. g. , texts, experiments, simulations) into a coherent understanding of a process, phenomenon, or concept, resolving conflicting information when possible.

Why Mini-Units? i 3 College Ready Writers Program National Writing Project The US Department of Education’s program, Investing in Innovation, funded the College-Ready Writers Program. The innovation that NWP proposed was to provide professional development to rural secondary schools in new ways of teaching of argument. Innovation requires trying something new, taking risks, and diving in. This approach is showing promise in many schools and districts that are participating in the project. This year the Kentucky Writing Project has been adapting these materials to expand the project to elementary classrooms and to use the frameworks to develop additional mini-units on other topics and for all contents. Trying a mini-unit approach (instead of a traditional, lengthy unit) is new for many teachers and may feel risky.

What are the Mini-Units? From NWP CRWP i 3 College Ready Writers Program The mini-units are short teaching units (3 -8 class periods or less) that result in students writing arguments using sources as evidence. These mini-units are engaging for students. They are designed to be layered, with new mini-units being taught periodically over the course of the year. • They typically start with readings using strategies that support students in understanding an issue. • They then move quickly to support students’ argument writing. • They don’t intend to teach students everything they need to know about writing arguments, but rather to focus a few key skills. • The design requires we use a succession of mini-units, building on the students’ work each time.

Why Non-Fiction? From NWP CRWP i 3 College Ready Writers Program During a mini-unit, students assemble evidence from non-fiction texts that offer a variety of perspectives and, often, a variety of genres, too. The thinking students have to do in these units is to understand multiple approaches to a single topic or issue and stake out a position for themselves. They do this by citing the readings and then building a case for their own claim. Reading strategies are introduced to help students work with non-fiction, to assist in comprehension and to support selecting and using evidence. Why? • Develop Critical Reading Skills: These mini-units help students gain control over information, even, or especially, information that may communicate conflicting points of view. • Develop Abilities to Use Sources: College teachers identify this as THE essential skill in college. In the mini-units, students writing from the mini-units place themselves in a current conversation about an issue or idea and argument for the consequence, the validity, or the “rightness” of their position by citing multiple texts. This conflict of purposes is why we haven’t mixed literary and non-literary texts in these units, running the risk of reducing the impact of literature and confusing the purpose of writing argument from sources. • Prepare Students for College and Career: This kind of writing is what students will experience in college writing programs and in their majors. Academic work is nearly all about assessing existing information and finding one’s place in it. College writing programs have changed. Set aside notions of grueling college writing. These materials have been reviewed by college writing teachers for authenticity of purpose.

What are the Common Components? From NWP CRWP i 3 College Ready Writers Program • A progression of work in text-based argument writing around a common topic – – – Close reading that includes writing about the readings. Focus on a particular skill or move that writers use in order to make arguments. Revisiting the readings to draft an argument. Focused feedback provided on students’ use of the skill. Students are supported in making revisions based on that feedback. Such a process layers over time the complex array of skills that students will eventually need to orchestrate in order to demonstrate competence in argument writing. • A text set – – To connect students to issues that will invite them—even incite them—to write. Informational texts that will provide information for students as they seek to understand the topic and then later, will serve as evidence for students as they take positions on the topic. OR Opinion pieces that introduce different perspectives on the topic, allowing students to consider their own stances and then select the most compelling pieces of evidence to support and extend their own thinking. While we encourage you to first try the mini-units with these original texts—because we know these texts work with real students—reteaching the mini-unit may be helpful in developing students’ expertise. A second or third text set could be substituted at this point.

Common Components, cont. From NWP CRWP i 3 College Ready Writers Program • Close reading and exploratory writing – Strategies slow students down enough to really think about the facts, the issues, and the perspectives involved. – Guidance in identifying evidence that could be used to support a claim. – Writing to learn and to discover so that students see the complexities in taking a stand on an issue as well as have opportunities to carefully consider their own stances. • Argumentation focus – Emphasis on at least one particular element of argumentation—a skill or writing move that helps students make effective arguments. – The intent is to work more intensely on a particular aspect of argument writing, master it, and then take up another mini-unit that will focus on a different, but equally important move that argument writers make. – A chart is provided that identifies some of these elements that students will be learning. – Mini-units allow teachers to layer the instruction of argument so that students are learning one or two key moves in a single mini-unit that they will then be expected to take up more independently in subsequent writing opportunities. • Writing Processes – Students draft their own texts AND revise them after feedback from peers and/or teacher. • Sense-making and Transfer/ Processing – We need to name what we are learning in order to be able to access it later. Student self-assessment, peer assessment, and/or reflection are part of most mini-units.

Mini-units feature tools to support students in learning how to write arguments • Harris Moves: To help students learn to use sources effectively • Bernabei Kernel Essays: To help students learn to consider purpose as they organize their arguments • Organizers and partner/small group activities to scaffold student writers as they learn new skills

Harris Moves: Ways to Use Sources A t e m r Illustrating – When writers use specific examples or facts from a text to support what they want to say. o h p a Examples: The 18 -wheeler carries lots of cargo, representing “material to think about: anecdotes, images, scenarios, data. ” (Harris) ● ● ● ● “_____ argues that ______. ” “_____ claims that ______” “_____ acknowledges that ______” “_____ emphasizes that ______” “_____ tells the story of ______ “ “_____ reports that ______” “_____ believes that ______” Leeanne Bordelon, NSU Writing Project, 2014

Example of Illustrating from “The Early Bird Gets the Bad Grade” by Nancy Kalish: “When high schools in Fayette County in Kentucky delayed their start times to 8: 30 a. m. , the number of teenagers involved in car crashes dropped, even as is a h t s i y a w t a they rose in the state. ” In wh t? c a f r o e l p m specific exa laim might c f o d n i k t a h W rt? o p p u s o t d e it be us Linda Denstaedt, i 3 Leadership Team, National Writing Project

Harris Moves: Ways to Use Sources A t e m r o h p a ● Authorizing – When writers quote an expert or use the credibility or status of a source to support their claims. ords w t a Wh each Joseph Bauxbaum, a researcher at the Mount Sinai make n seem perso le? School of Medicine, found … credib According to Susan Smith, principal of a school which claim t a h W ach encourages student cell phone use, … e t h g mi elp h e t A study conducted by the Gulf Coast Center for Law & quo rt? Policy Center, a non-profit organization which monitors suppo environmental issues, revealed that … Leeanne Bordelon, NSU Writing Project, 2014

Example of Authorizing from “High schools with late start times help teens but bus schedules and after-school can conflict” [“T]he focus on logistics is frustrating for Heather Macintosh, spokeswoman for a national organization called Start School Later…. “What is the priority? ” she said. “It should be education, health and safety. ” Linda Denstaedt, i 3 Leadership Team, National Writing Project ds r o w What her make seem le? credib aim l c t a Wh this t h g i m help e t o qu rt? o p p u s

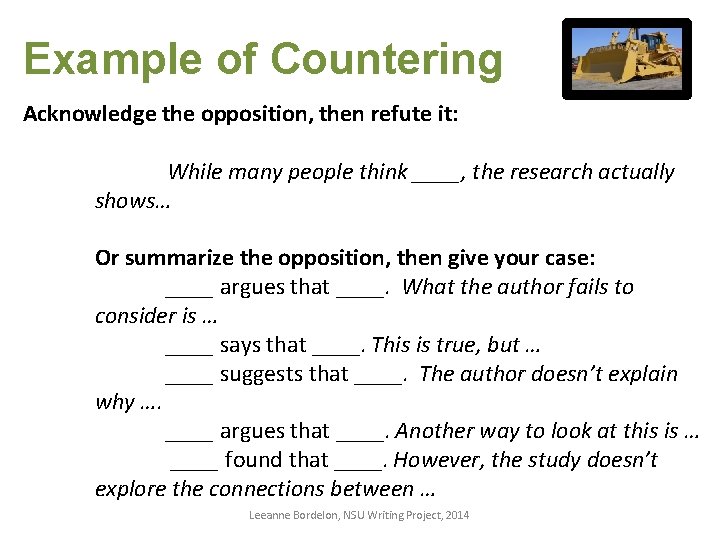

Harris Moves: Ways to Use Sources A r t e m o h p a ● Countering – Countering--When a writer “pushes back” against the text in some way, by disagreeing with it, challenging something it says, or interpreting it differently than the author does. e are th While parent groups often portray gaming negatively, recent brain research indicates there are positive effects. Leeanne Bordelon, NSU Writing Project, 2014 What ements l key e od o of a g ter”? “coun

Example of Countering Acknowledge the opposition, then refute it: While many people think ____, the research actually shows… Or summarize the opposition, then give your case: ____ argues that ____. What the author fails to consider is … ____ says that ____. This is true, but … ____ suggests that ____. The author doesn’t explain why …. ____ argues that ____. Another way to look at this is … ____ found that ____. However, the study doesn’t explore the connections between … Leeanne Bordelon, NSU Writing Project, 2014

Bernabei’s Kernal Essay Templates First I thought… Overview of the Issue Some people think ___ because… Then I learned… Others think ___ because… Now I think… The most compelling evidence is ____; it has made me think… In the end, I say…

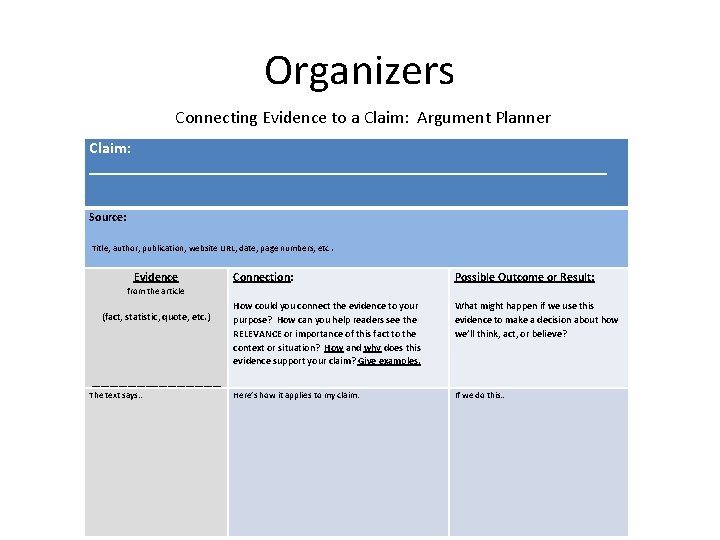

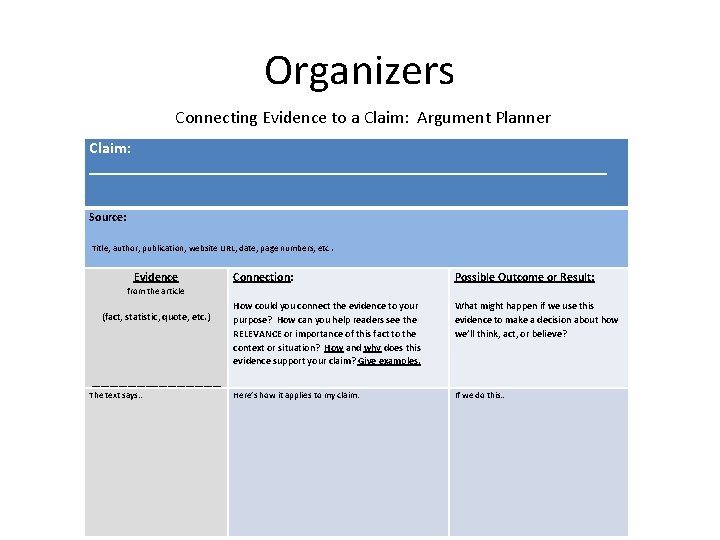

Organizers Connecting Evidence to a Claim: Argument Planner Claim: _________________________________ Source: Title, author, publication, website URL, date, page numbers, etc. Evidence Connection: Possible Outcome or Result: How could you connect the evidence to your purpose? How can you help readers see the RELEVANCE or importance of this fact to the context or situation? How and why does this evidence support your claim? Give examples. What might happen if we use this evidence to make a decision about how we’ll think, act, or believe? Here’s how it applies to my claim: If we do this… from the article (fact, statistic, quote, etc. ) _______________ The text says…

What Might a Year Look Like? August September Baseline On. Analysis of First Demand & Analysis mini-unit drafts of work October November-December Analysis of Second mini-unit drafts Analysis of 3 rd mini-unit drafts Writing into the Day activities to introduce Thinking Like an Argument Writer --------Initial Mini-Unit Selection & teaching nd teaching of 2 mini of 3 rd mini-unit Focus/feedback/revi. Focus/feedback/re- sion on Commentary vision on Evidence Selection and Harris Moves Focus/feedback/re- (illustrating, vision on Claim authorizing, countering) Examples: Reality TV, Teen Brain, What Should We Eat Nutrition in Schools, School Start Time, Gaming Fast Food, Recycling, Online Privacy Review of drafts from first 3 mini-units. Selection of one to develop further (more research, with students searching for additional credible sources), feedback and revision (claim, evidence, commentary), edit, and publish

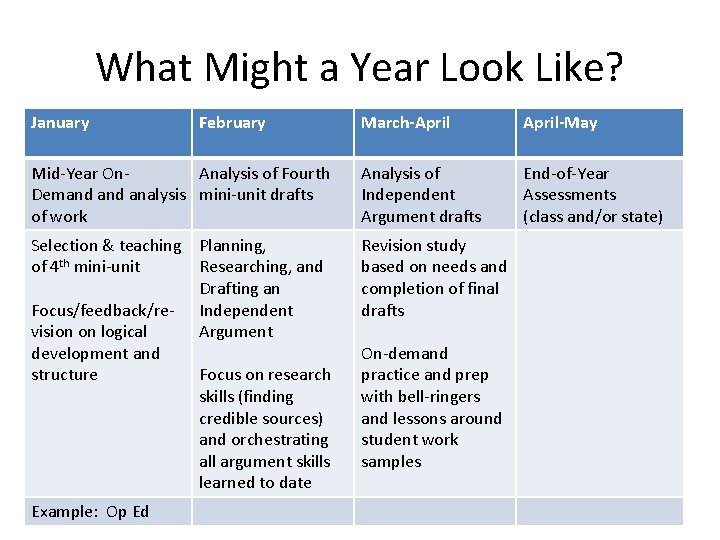

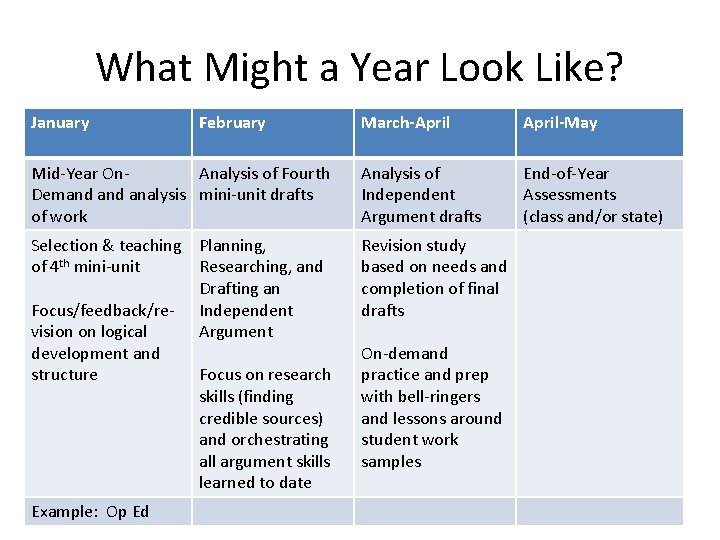

What Might a Year Look Like? January March-April-May Mid-Year On. Analysis of Fourth Demand analysis mini-unit drafts of work Analysis of Independent Argument drafts End-of-Year Assessments (class and/or state) Selection & teaching Planning, of 4 th mini-unit Researching, and Drafting an Focus/feedback/re- Independent vision on logical Argument development and structure Focus on research skills (finding credible sources) and orchestrating all argument skills learned to date Revision study based on needs and completion of final drafts Example: Op Ed February On-demand practice and prep with bell-ringers and lessons around student work samples

Using Mini-Units in PD From NWP CRWP i 3 College Ready Writers Program Things to look for you read and write your way through this mini-unit: – Ways a lesson supports students’ engagement with and access to texts and topics; – How the unit builds enough knowledge to write a short argument by recursive reading and writing. Post-demonstration questions for debriefing: – How does the design of this lesson support students in trying new ways of thinking? How do these experiences support students in writing arguments? How often should such a lesson be repeated to develop processes that become habits? – How close is what you just did as a learner/reader/writer to what your students are currently doing in argumentation? What will get them ready to do this work? What kinds of things will you consider in adapting these materials for your students and your classroom? – What are the key components of this mini-unit? Where should this unit be positioned in a year of learning? How do we use this framework to design and plan OTHER writing experiences with different materials or topics? – What are the challenges and opportunities in teaching this mini-unit? What shifts will you need to make to do this work? What kinds of support might you/your fellow teachers need as you take up or adapt the miniunit’s lessons and materials?

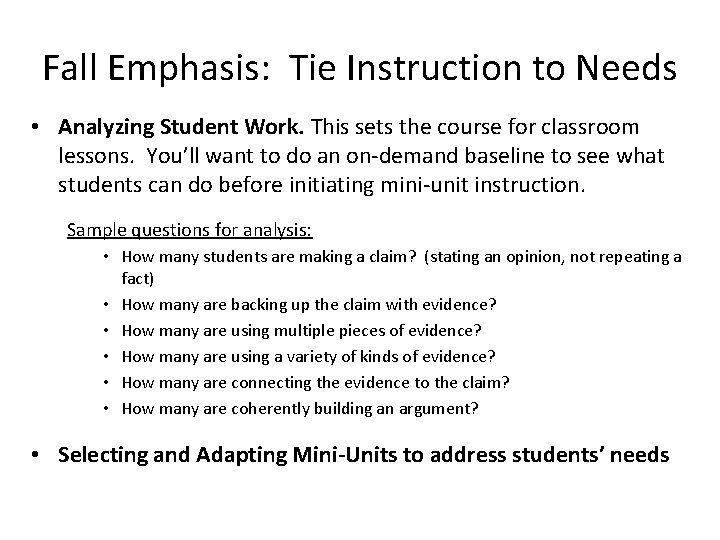

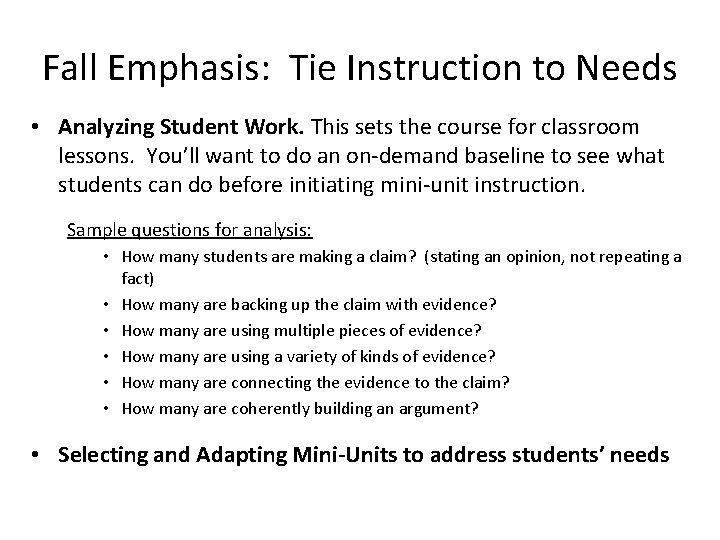

Fall Emphasis: Tie Instruction to Needs • Analyzing Student Work. This sets the course for classroom lessons. You’ll want to do an on-demand baseline to see what students can do before initiating mini-unit instruction. Sample questions for analysis: • How many students are making a claim? (stating an opinion, not repeating a fact) • How many are backing up the claim with evidence? • How many are using multiple pieces of evidence? • How many are using a variety of kinds of evidence? • How many are connecting the evidence to the claim? • How many are coherently building an argument? • Selecting and Adapting Mini-Units to address students’ needs

What is primary sources

What is primary sources Primary evidence vs secondary evidence

Primary evidence vs secondary evidence Secondary sources

Secondary sources Primary evidence vs secondary evidence

Primary evidence vs secondary evidence Jobs vancouver

Jobs vancouver Unlike routine claims, persuasive claims:

Unlike routine claims, persuasive claims: Zack furness

Zack furness Language across the curriculum conclusion

Language across the curriculum conclusion Numeracy across the curriculum audit

Numeracy across the curriculum audit Fiber evidence can have probative value.

Fiber evidence can have probative value. Class evidence vs individual evidence

Class evidence vs individual evidence Class evidence can have probative value.

Class evidence can have probative value. Individual vs class evidence

Individual vs class evidence Red herring fallacy

Red herring fallacy Content analysis secondary data

Content analysis secondary data Defect of present curriculum

Defect of present curriculum What is health and family life education

What is health and family life education New secondary curriculum

New secondary curriculum Cca

Cca Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Lp html

Lp html Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Gấu đi như thế nào

Gấu đi như thế nào Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton

Chụp phim tư thế worms-breton Hát lên người ơi alleluia

Hát lên người ơi alleluia Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất