Aggregate Expenditure Outline Components of aggregate expenditure Planned

![Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures [Y] [C] [I] [G] [X] [M] [AE Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures [Y] [C] [I] [G] [X] [M] [AE](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1e25a4d7c24fbe080902207c55f58f6d/image-23.jpg)

![Now solve for Y [4] Now rearrange [4] [5] Divide both sides of [5] Now solve for Y [4] Now rearrange [4] [5] Divide both sides of [5]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1e25a4d7c24fbe080902207c55f58f6d/image-42.jpg)

- Slides: 47

Aggregate Expenditure Outline • Components of aggregate expenditure • Planned and unplanned expenditure • The consumption function • Imports and GDP • Equilibrium expenditure • The expenditure multiplier

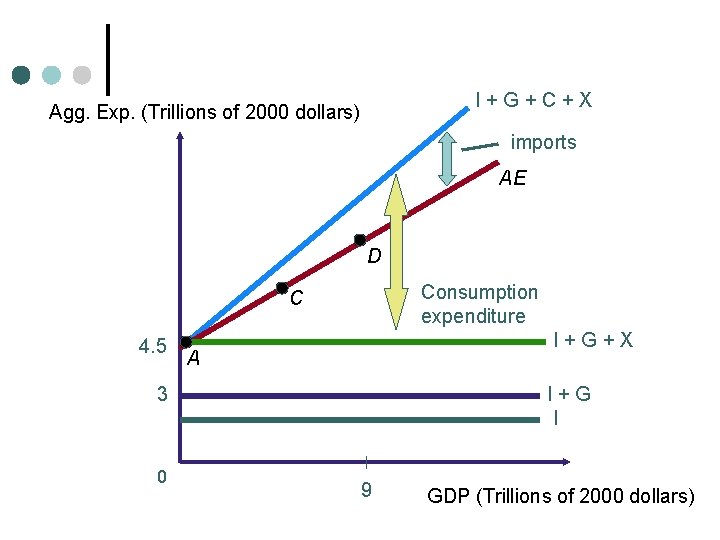

Components of Aggregate Expenditure Recall from Chapter 5 that aggregate expenditure for final goods and services equals the sum of • Consumption expenditure, C • Investment, I • Government purchases of goods and services, G • Net exports, NX Thus: Aggregate expenditure = C + I + G + NX

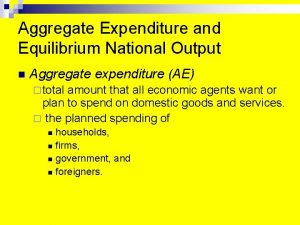

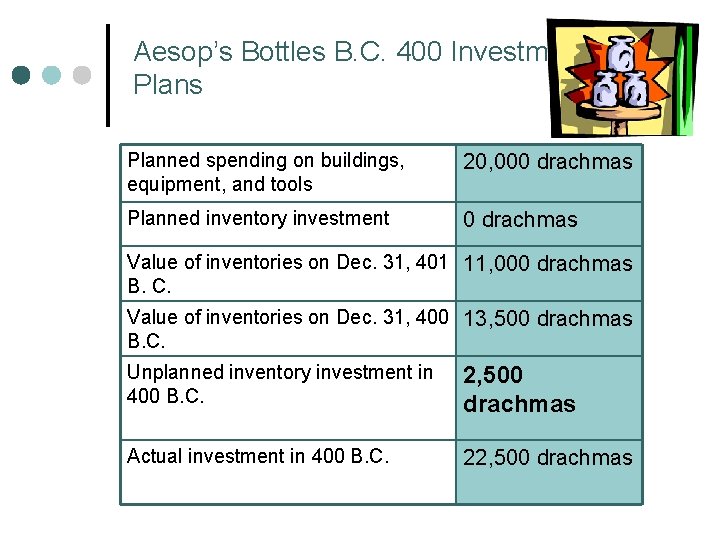

Planned and Unplanned Expenditures Aggregate expenditure equals aggregate income and real GDP. But aggregate planned expenditure might not equal real GDP because firms can end up with larger or smaller inventories than they had intended.

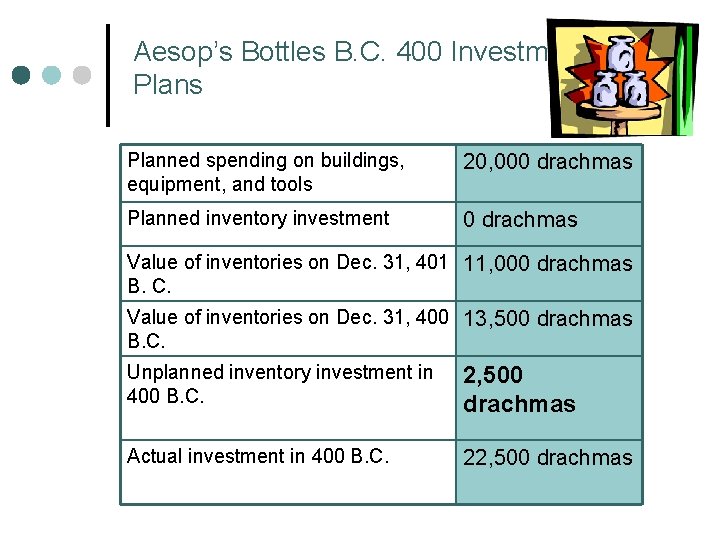

Aesop’s Bottles B. C. 400 Investment Plans Planned spending on buildings, equipment, and tools 20, 000 drachmas Planned inventory investment 0 drachmas Value of inventories on Dec. 31, 401 11, 000 drachmas B. C. Value of inventories on Dec. 31, 400 13, 500 drachmas B. C. Unplanned inventory investment in 400 B. C. 2, 500 drachmas Actual investment in 400 B. C. 22, 500 drachmas

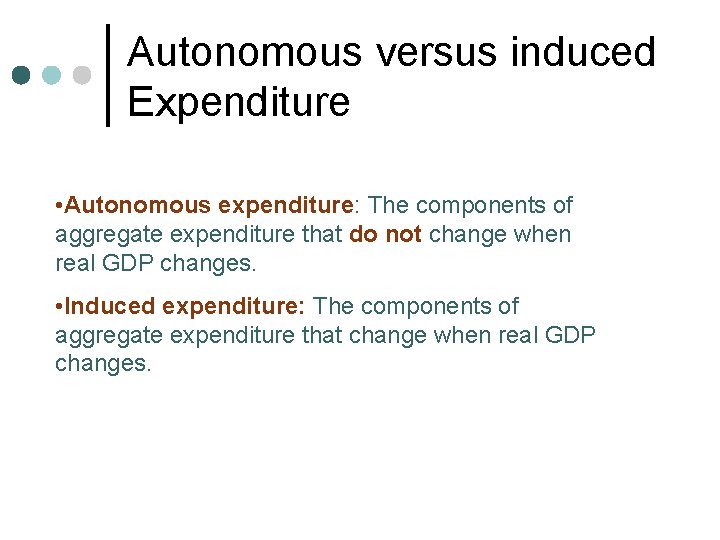

Autonomous versus induced Expenditure • Autonomous expenditure: The components of aggregate expenditure that do not change when real GDP changes. • Induced expenditure: The components of aggregate expenditure that change when real GDP changes.

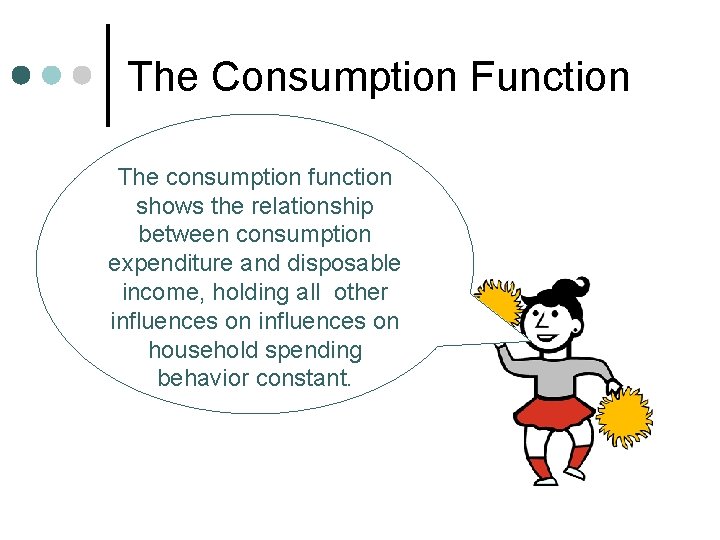

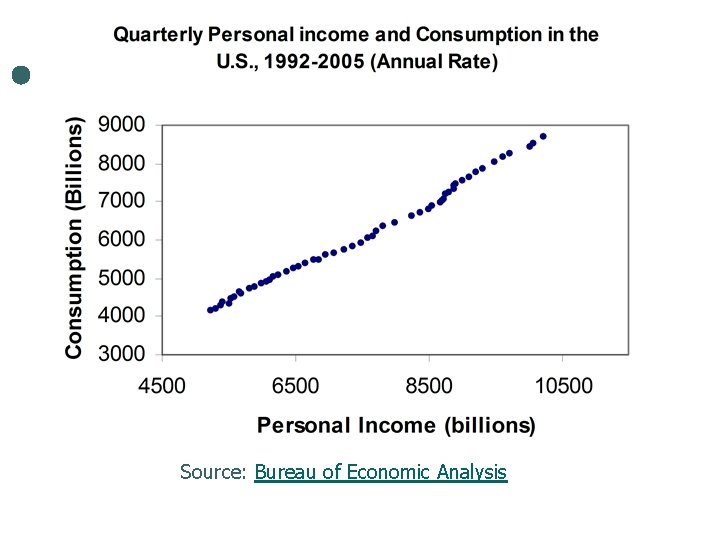

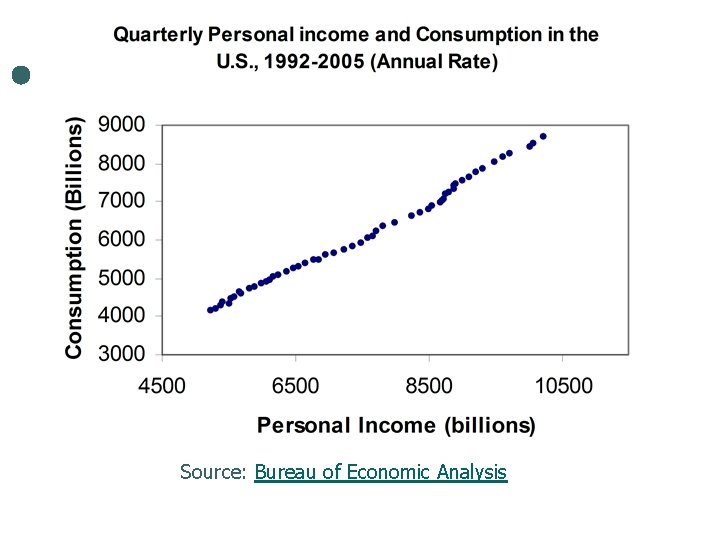

The Consumption Function The consumption function shows the relationship between consumption expenditure and disposable income, holding all other influences on household spending behavior constant.

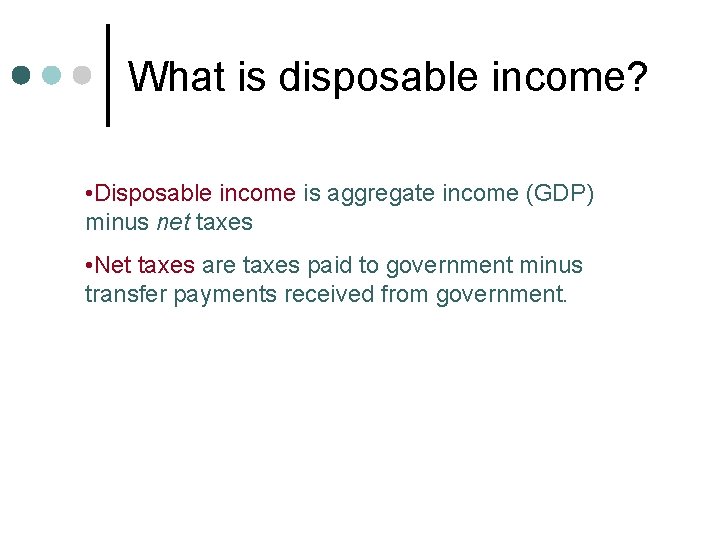

What is disposable income? • Disposable income is aggregate income (GDP) minus net taxes • Net taxes are taxes paid to government minus transfer payments received from government.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

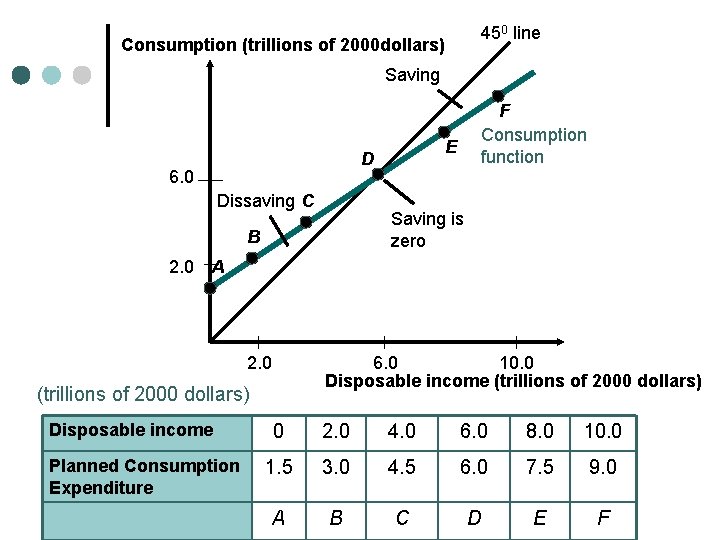

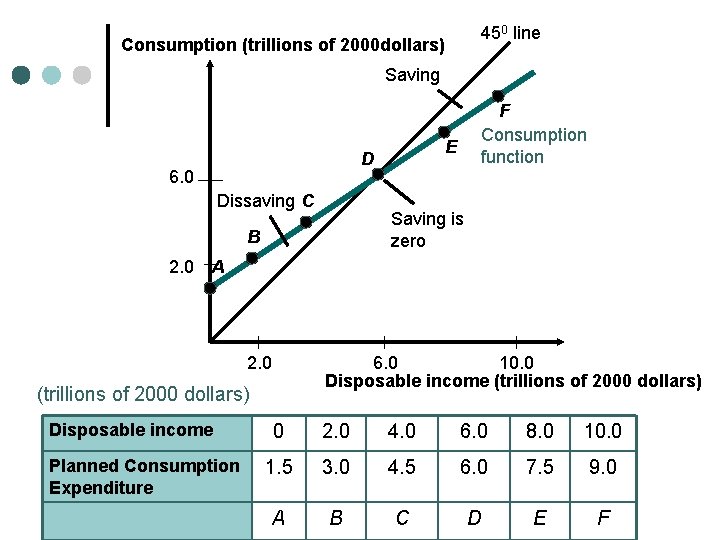

450 line Consumption (trillions of 2000 dollars) Saving E D 6. 0 Dissaving C F Consumption function Saving is zero B 2. 0 A 2. 0 6. 0 10. 0 Disposable income (trillions of 2000 dollars) Disposable income Planned Consumption Expenditure 0 2. 0 4. 0 6. 0 8. 0 10. 0 1. 5 3. 0 4. 5 6. 0 7. 5 9. 0 A B C D E F

Notice that autonomous consumption is given by point A. This is planned consumption expenditure when disposable income is zero ($1. 5 trillion). This spending must be financed by past saving or by borrowing

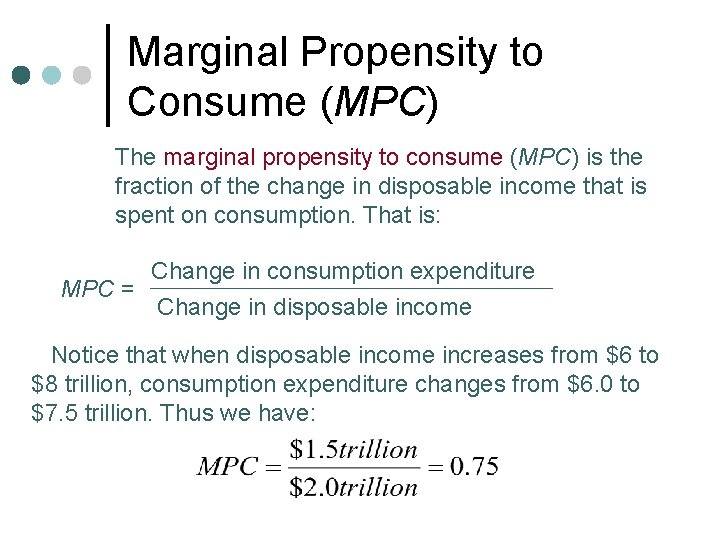

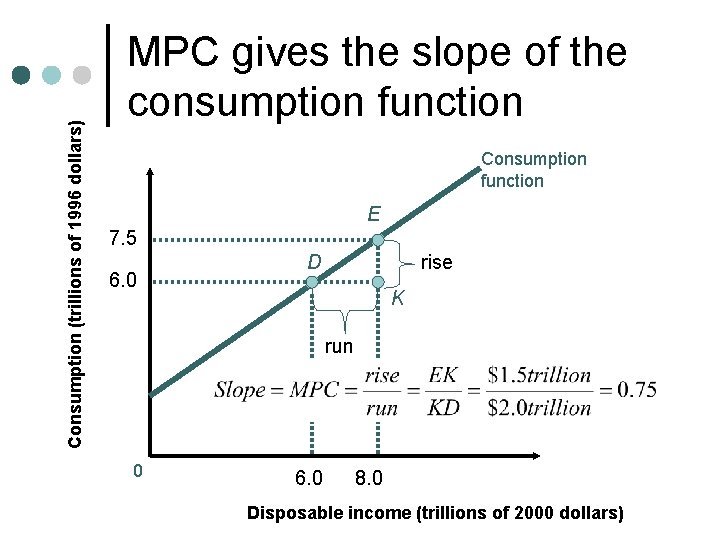

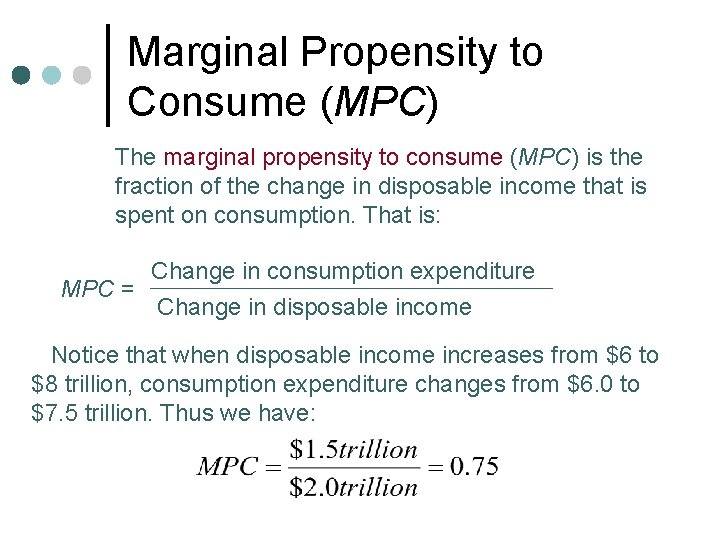

Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction of the change in disposable income that is spent on consumption. That is: Change in consumption expenditure MPC = Change in disposable income Notice that when disposable income increases from $6 to $8 trillion, consumption expenditure changes from $6. 0 to $7. 5 trillion. Thus we have:

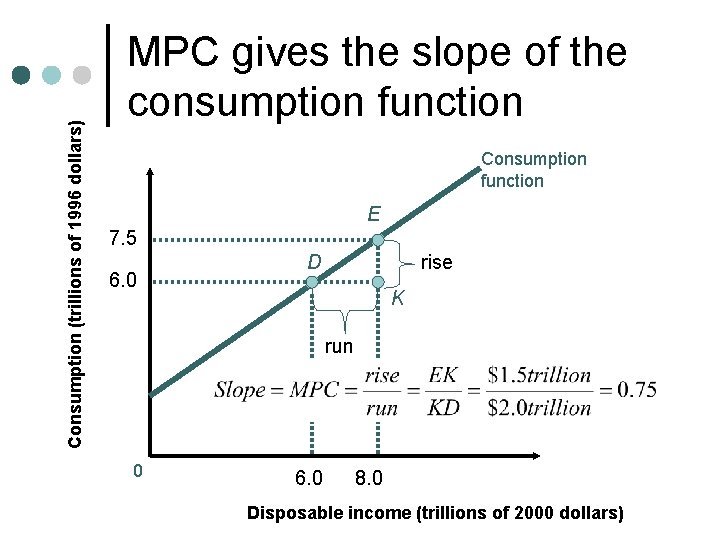

Consumption (trillions of 1996 dollars) MPC gives the slope of the consumption function Consumption function E 7. 5 6. 0 D rise K run 0 6. 0 8. 0 Disposable income (trillions of 2000 dollars)

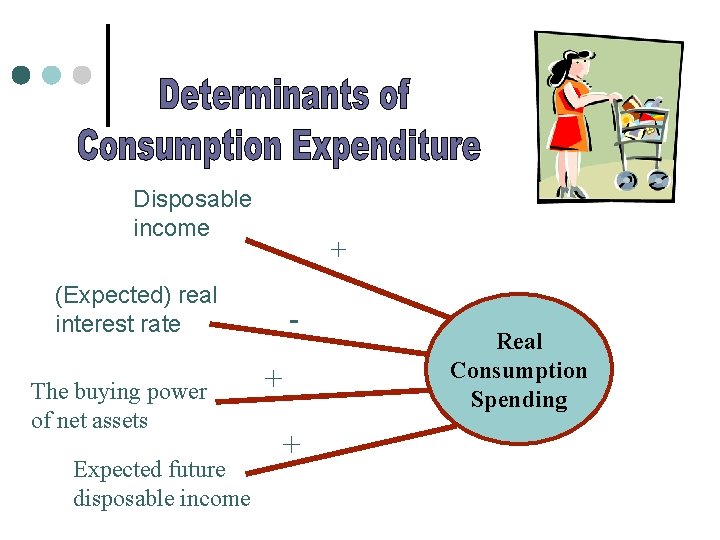

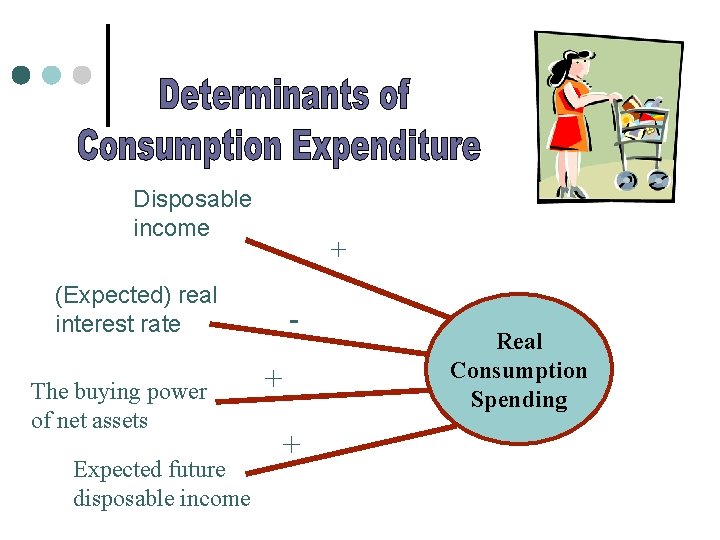

Disposable income + (Expected) real interest rate The buying power of net assets Expected future disposable income + + Real Consumption Spending

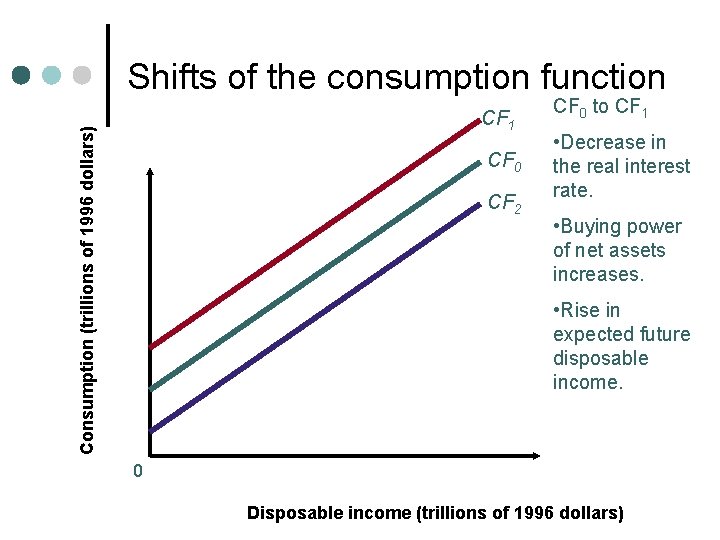

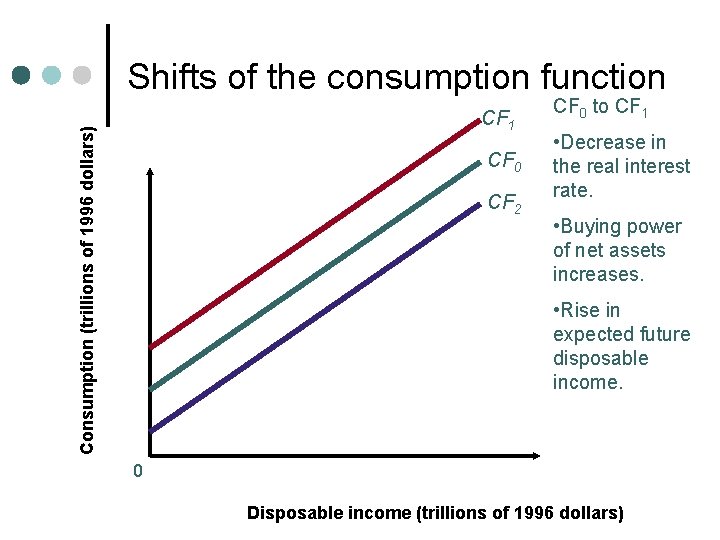

Shifts of the consumption function Consumption (trillions of 1996 dollars) CF 1 CF 0 CF 2 CF 0 to CF 1 • Decrease in the real interest rate. • Buying power of net assets increases. • Rise in expected future disposable income. 0 Disposable income (trillions of 1996 dollars)

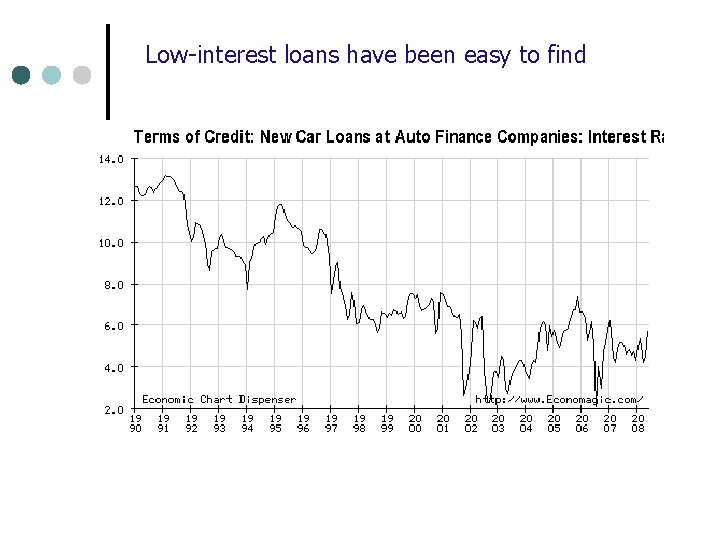

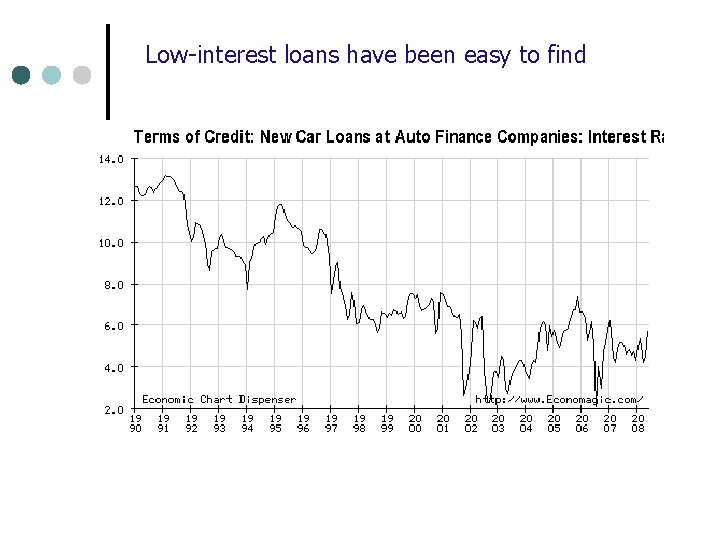

Low-interest loans have been easy to find

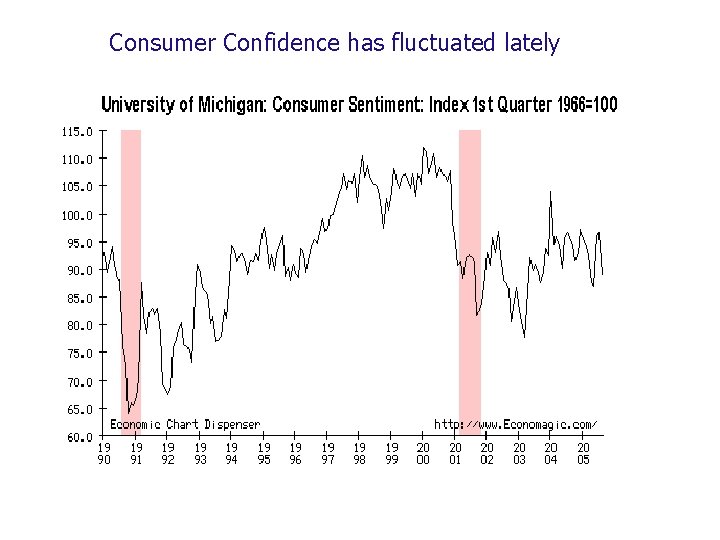

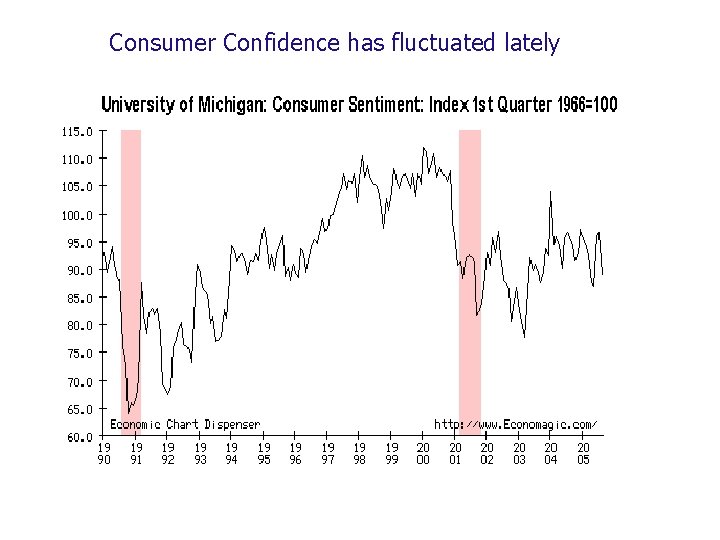

Consumer Confidence has fluctuated lately

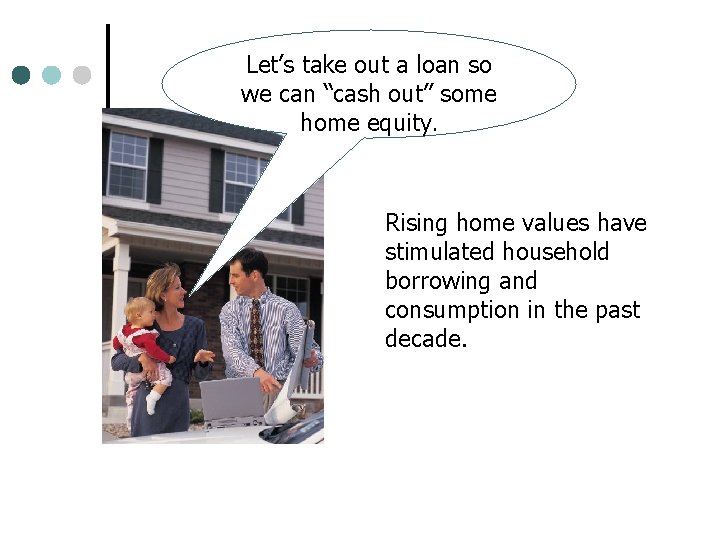

Let’s take out a loan so we can “cash out” some home equity. Rising home values have stimulated household borrowing and consumption in the past decade.

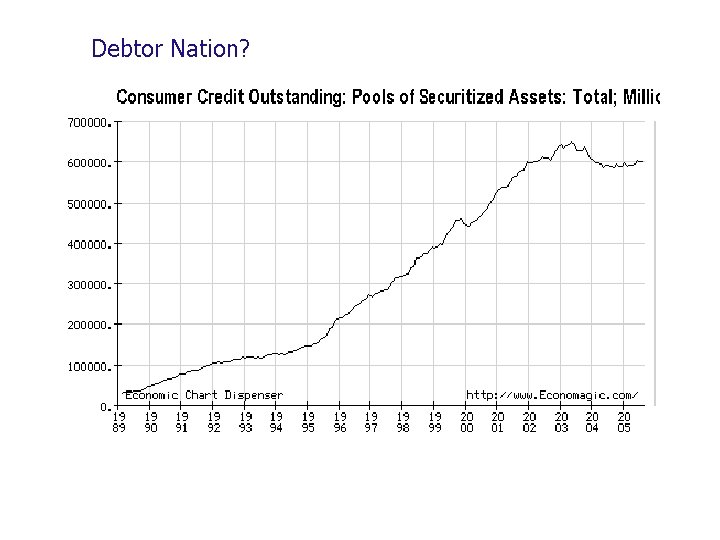

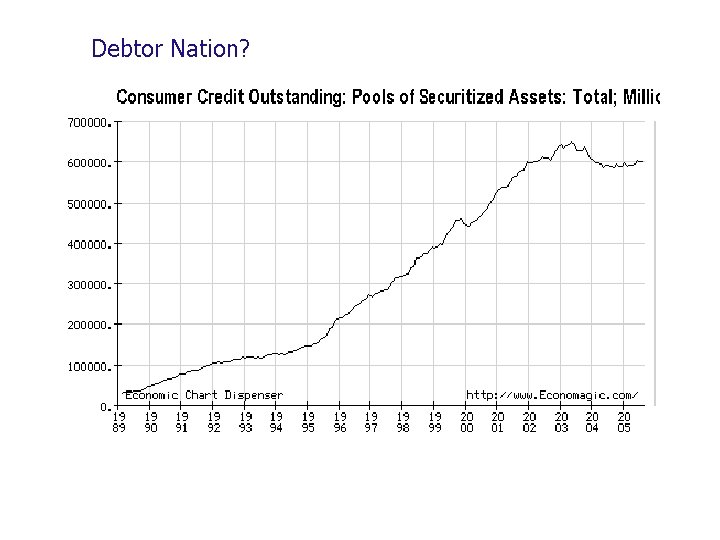

Debtor Nation?

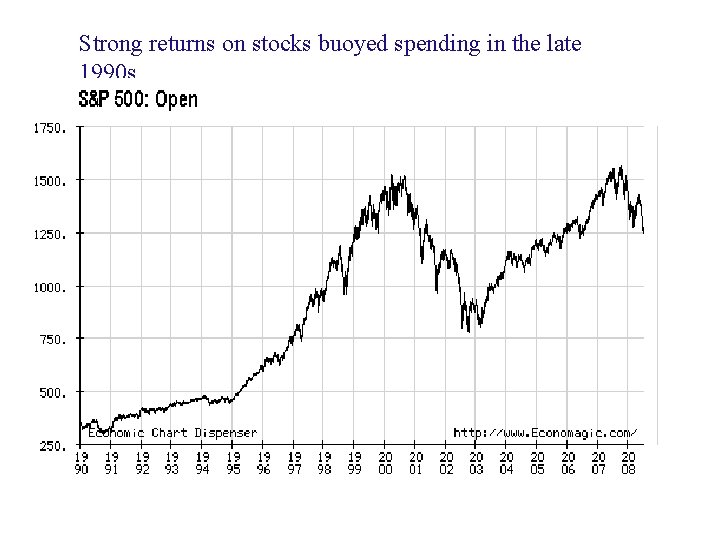

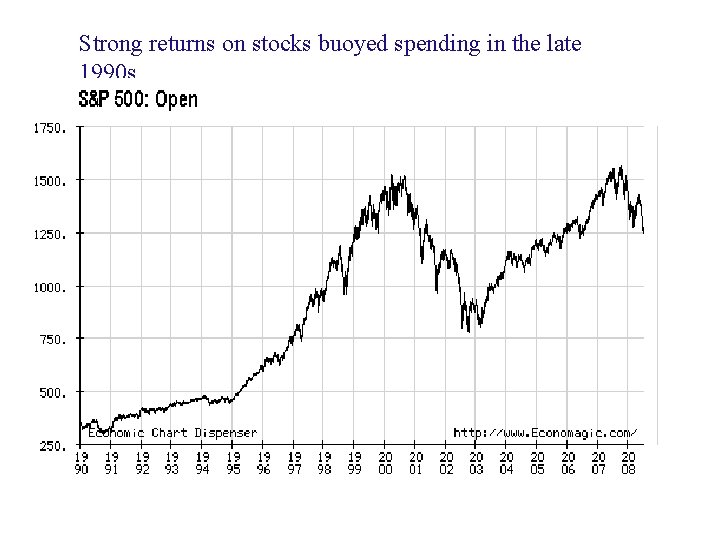

Strong returns on stocks buoyed spending in the late 1990 s.

Complete Exercise #1 on p. 402

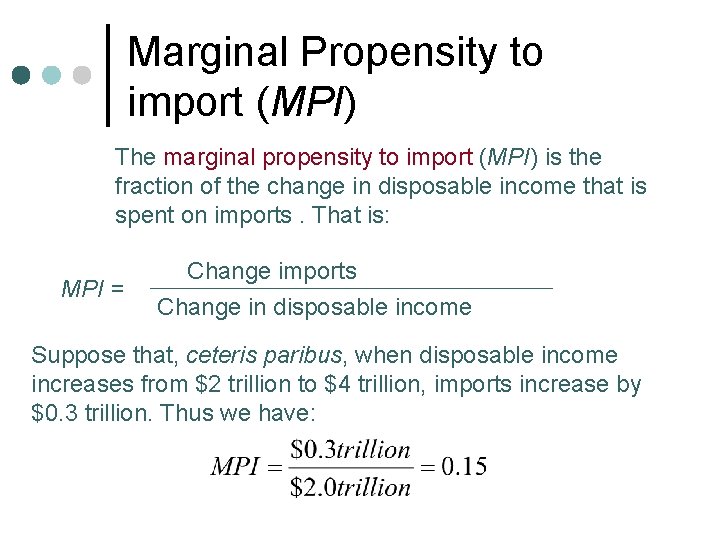

Imports and GDP Imports are a component of induced expenditure. Imports depend partly on the health of the domestic economy.

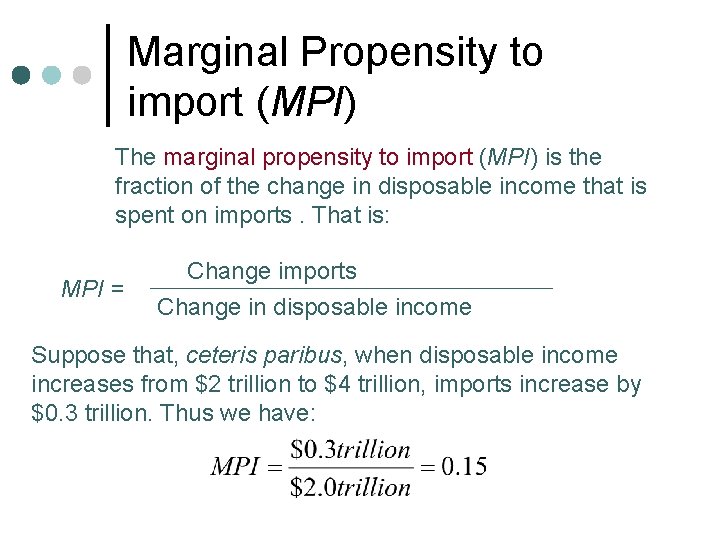

Marginal Propensity to import (MPI) The marginal propensity to import (MPI) is the fraction of the change in disposable income that is spent on imports. That is: MPI = Change imports Change in disposable income Suppose that, ceteris paribus, when disposable income increases from $2 trillion to $4 trillion, imports increase by $0. 3 trillion. Thus we have:

![Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures Y C I G X M AE Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures [Y] [C] [I] [G] [X] [M] [AE](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1e25a4d7c24fbe080902207c55f58f6d/image-23.jpg)

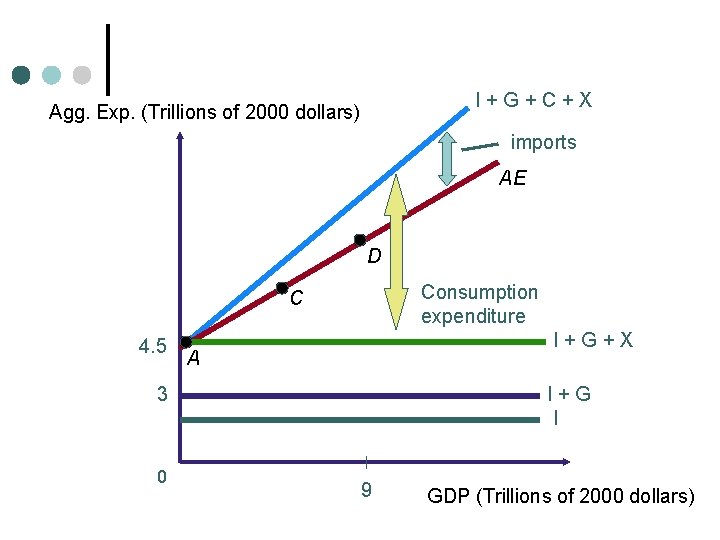

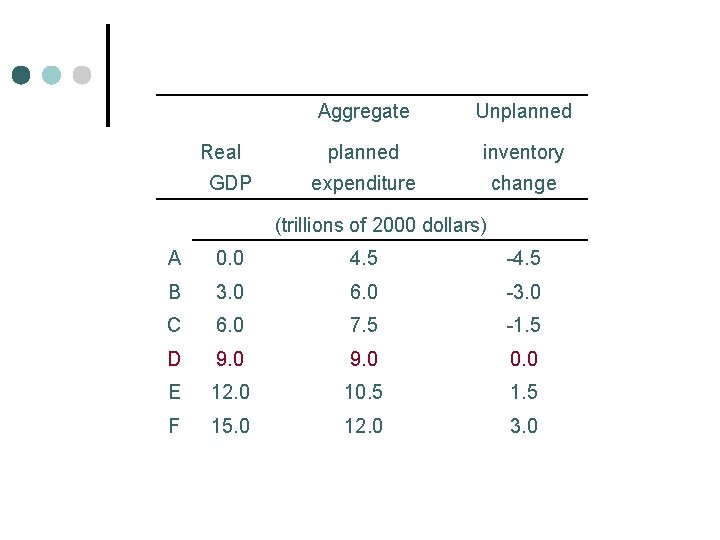

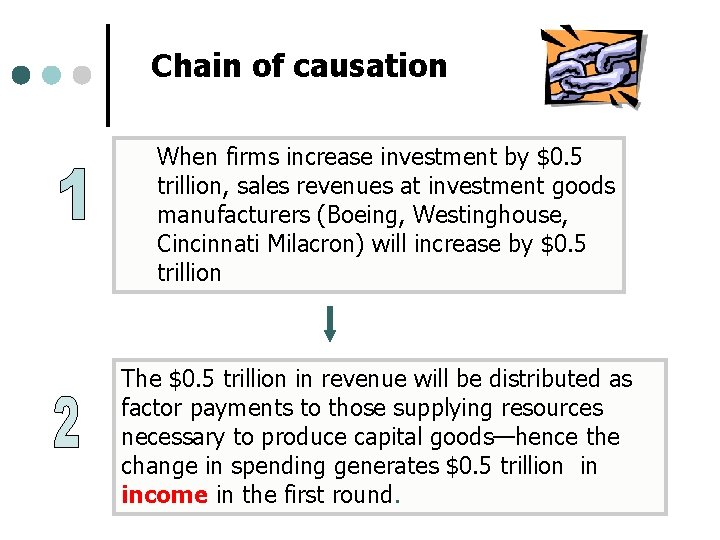

Aggregate Expenditure and Real GDP Planned Expenditures [Y] [C] [I] [G] [X] [M] [AE = C + I + G +X - M] (trillions of 2000 dollars) A 0. 00 2. 00 1. 50 0. 00 4. 50 B 3. 00 2. 25 2. 00 1. 50 0. 75 6. 00 C 6. 00 4. 50 2. 00 1. 50 7. 50 D 9. 00 6. 75 2. 00 1. 50 2. 25 9. 00 E 12. 00 9. 00 2. 00 1. 50 3. 00 10. 50 F 15. 00 11. 25 2. 00 1. 50 3. 75 12. 00 Note: Y is real GDP

I+G+C+X Agg. Exp. (Trillions of 2000 dollars) imports AE D Consumption expenditure C 4. 5 I+G+X A 3 0 I+G I 9 GDP (Trillions of 2000 dollars)

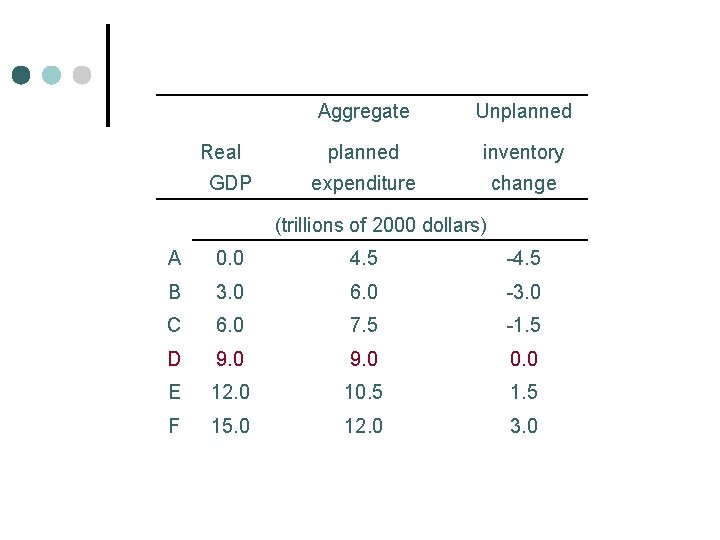

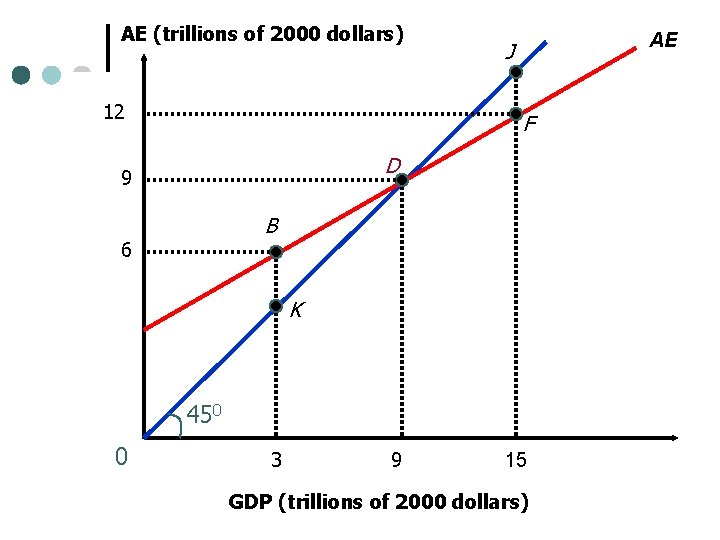

Real GDP Aggregate Unplanned inventory expenditure change (trillions of 2000 dollars) A 0. 0 4. 5 -4. 5 B 3. 0 6. 0 -3. 0 C 6. 0 7. 5 -1. 5 D 9. 0 0. 0 E 12. 0 10. 5 1. 5 F 15. 0 12. 0 3. 0

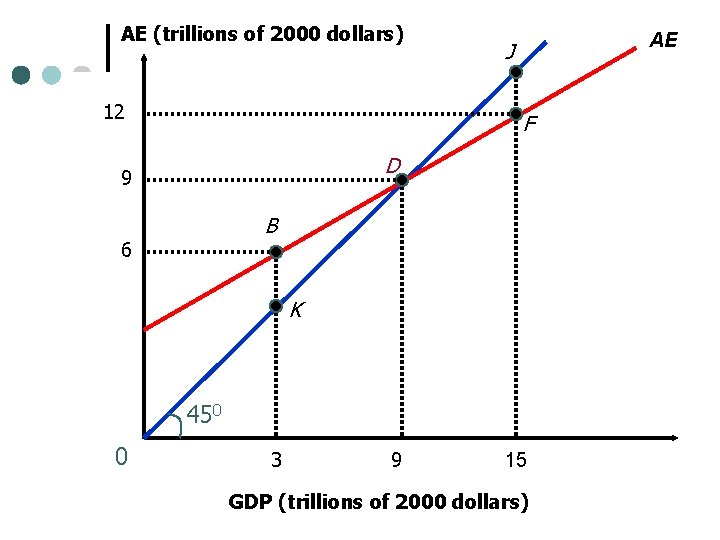

AE (trillions of 2000 dollars) 12 AE J F D 9 B 6 K 450 0 3 9 15 GDP (trillions of 2000 dollars)

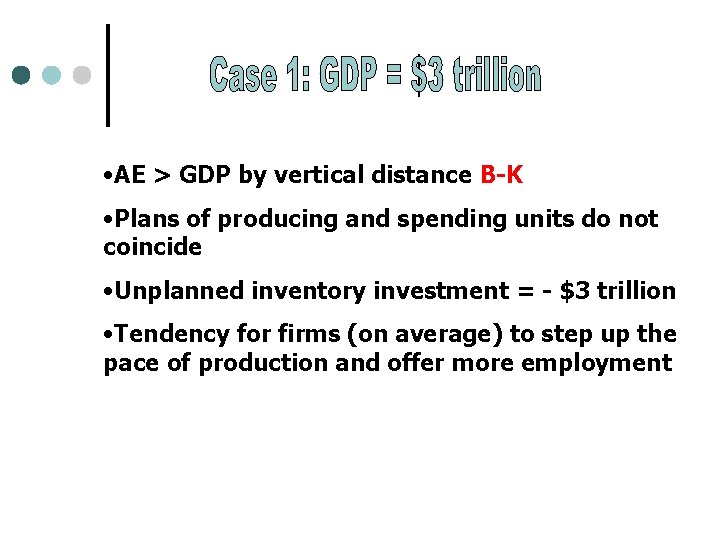

• AE > GDP by vertical distance B-K • Plans of producing and spending units do not coincide • Unplanned inventory investment = - $3 trillion • Tendency for firms (on average) to step up the pace of production and offer more employment

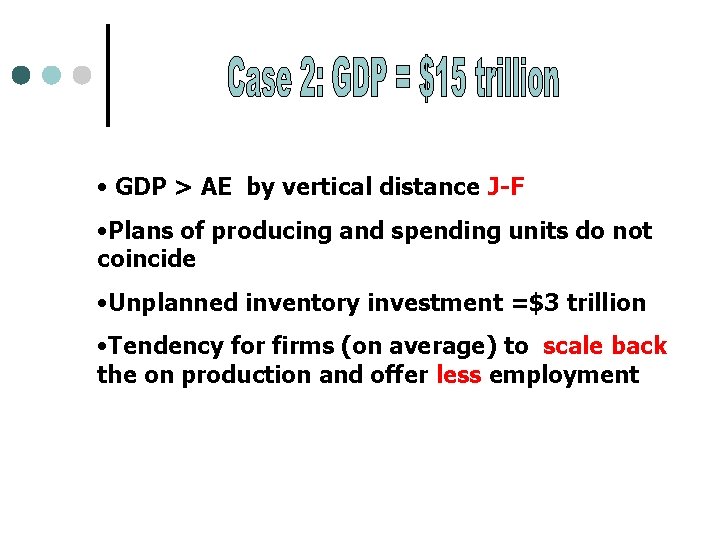

• GDP > AE by vertical distance J-F • Plans of producing and spending units do not coincide • Unplanned inventory investment =$3 trillion • Tendency for firms (on average) to scale back the on production and offer less employment

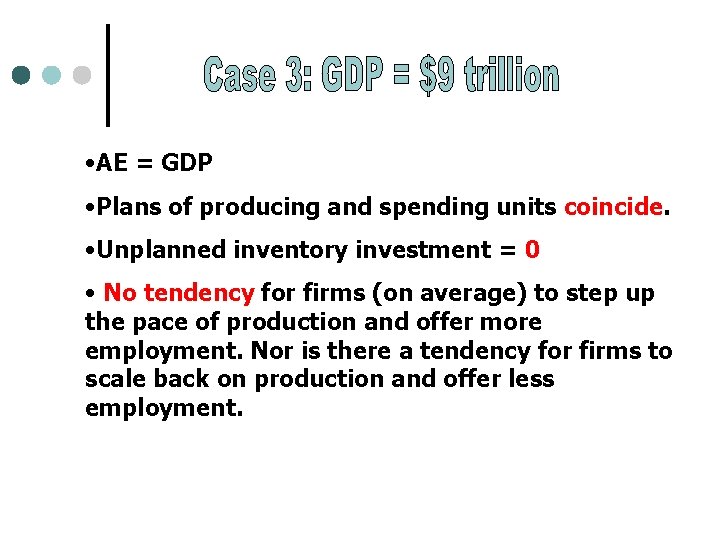

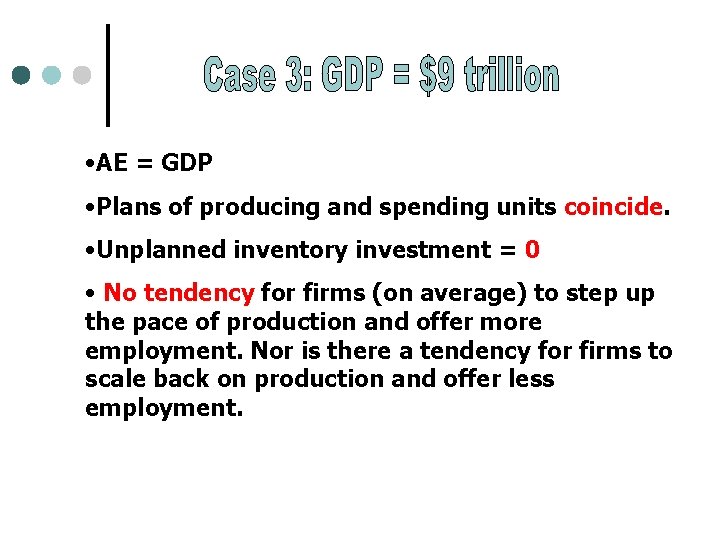

• AE = GDP • Plans of producing and spending units coincide. • Unplanned inventory investment = 0 • No tendency for firms (on average) to step up the pace of production and offer more employment. Nor is there a tendency for firms to scale back on production and offer less employment.

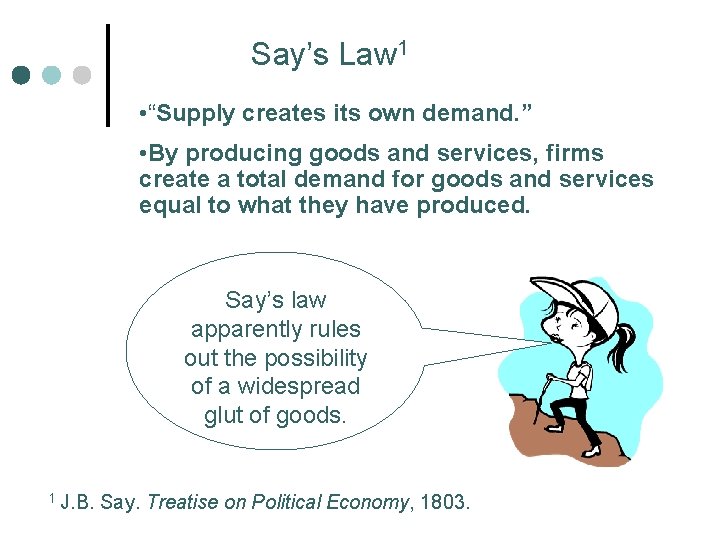

Say’s Law 1 • “Supply creates its own demand. ” • By producing goods and services, firms create a total demand for goods and services equal to what they have produced. Say’s law apparently rules out the possibility of a widespread glut of goods. 1 J. B. Say. Treatise on Political Economy, 1803.

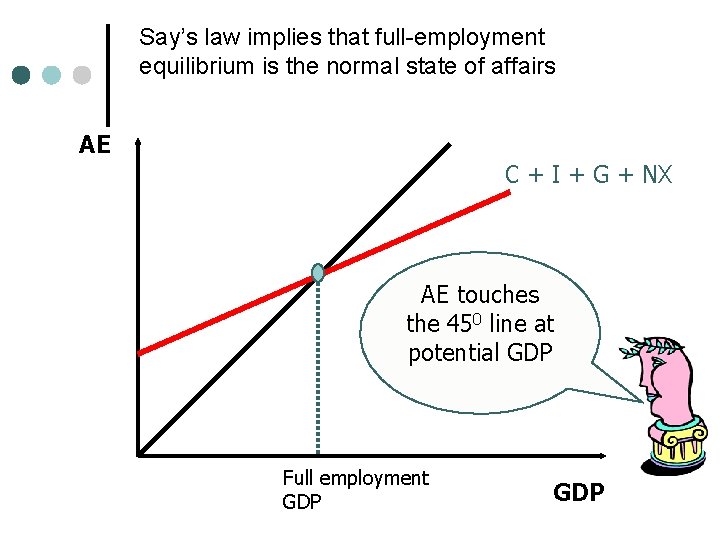

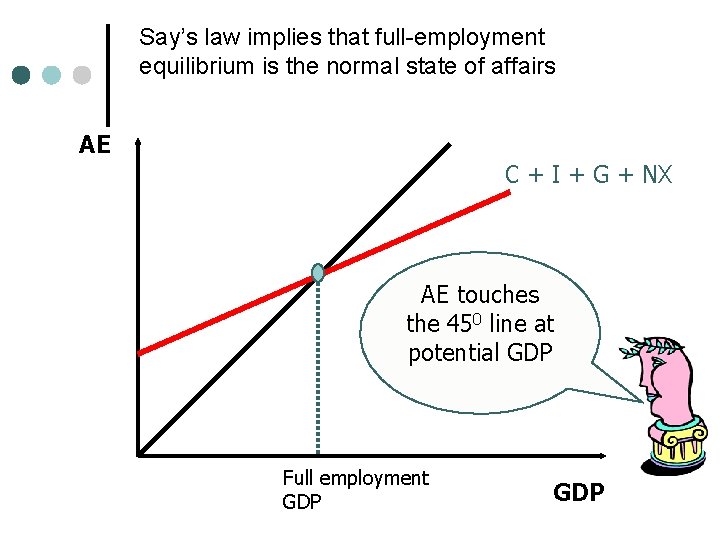

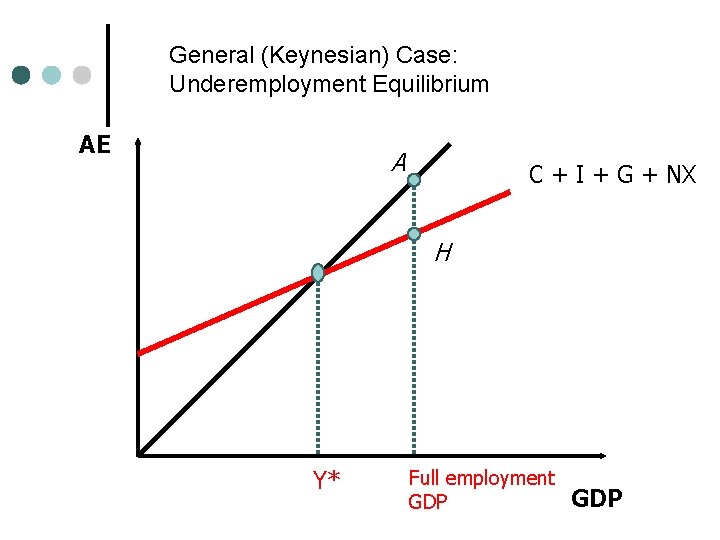

Say’s law implies that full-employment equilibrium is the normal state of affairs AE C + I + G + NX AE touches the 450 line at potential GDP Full employment GDP

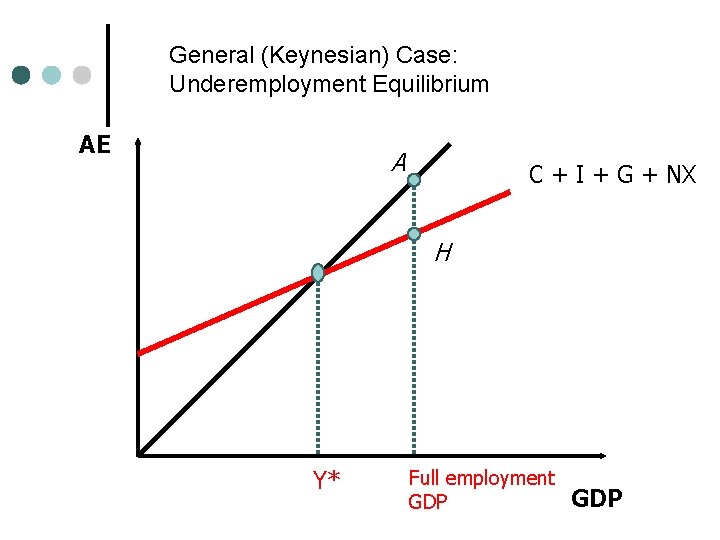

General (Keynesian) Case: Underemployment Equilibrium AE A C + I + G + NX H Y* Full employment GDP

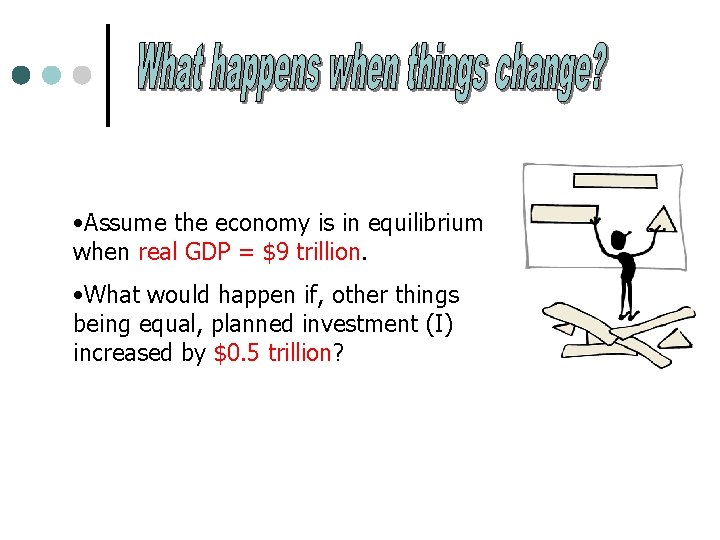

• Assume the economy is in equilibrium when real GDP = $9 trillion. • What would happen if, other things being equal, planned investment (I) increased by $0. 5 trillion?

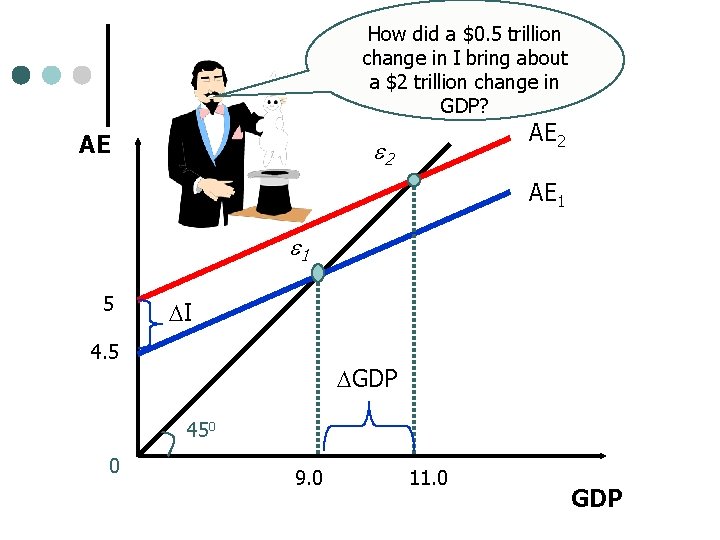

How did a $0. 5 trillion change in I bring about a $2 trillion change in GDP? AE AE 2 2 AE 1 1 5 I 4. 5 GDP 450 0 9. 0 11. 0 GDP

It’s a bird It’s a plane No, it’s the multiplier effect!

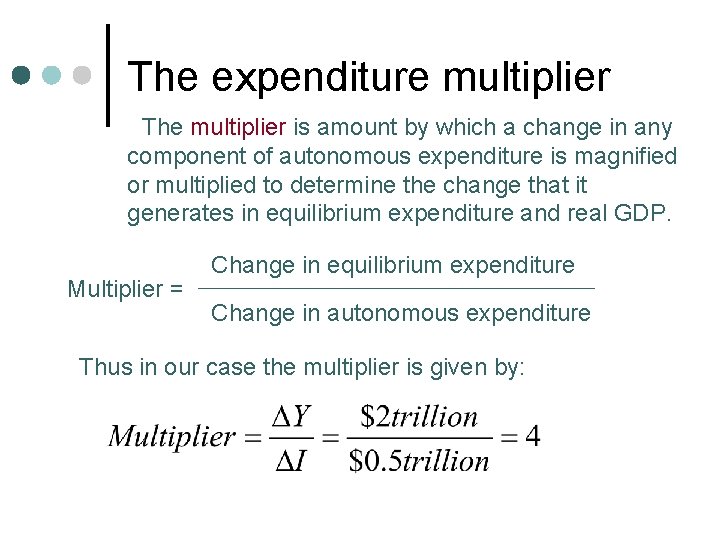

The expenditure multiplier The multiplier is amount by which a change in any component of autonomous expenditure is magnified or multiplied to determine the change that it generates in equilibrium expenditure and real GDP. Multiplier = Change in equilibrium expenditure Change in autonomous expenditure Thus in our case the multiplier is given by:

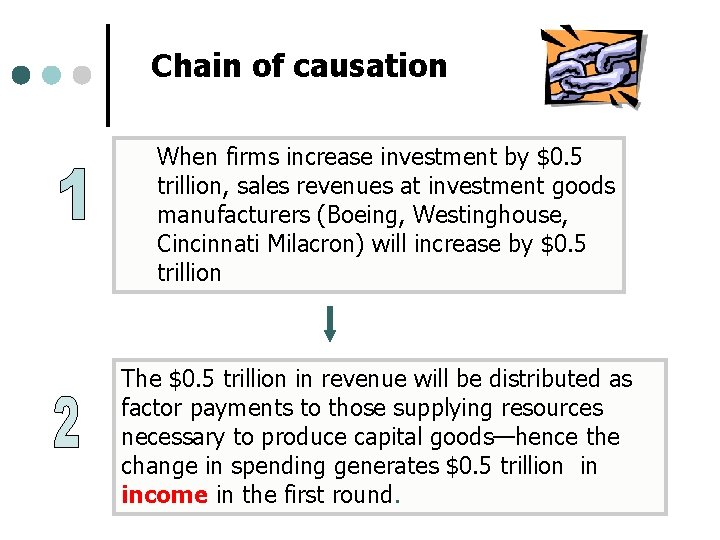

Chain of causation When firms increase investment by $0. 5 trillion, sales revenues at investment goods manufacturers (Boeing, Westinghouse, Cincinnati Milacron) will increase by $0. 5 trillion The $0. 5 trillion in revenue will be distributed as factor payments to those supplying resources necessary to produce capital goods—hence the change in spending generates $0. 5 trillion in income in the first round.

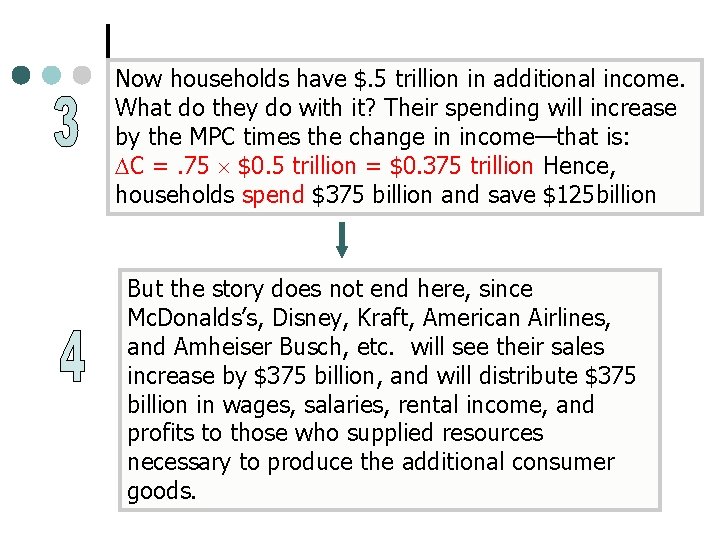

Now households have $. 5 trillion in additional income. What do they do with it? Their spending will increase by the MPC times the change in income—that is: C =. 75 $0. 5 trillion = $0. 375 trillion Hence, households spend $375 billion and save $125 billion But the story does not end here, since Mc. Donalds’s, Disney, Kraft, American Airlines, and Amheiser Busch, etc. will see their sales increase by $375 billion, and will distribute $375 billion in wages, salaries, rental income, and profits to those who supplied resources necessary to produce the additional consumer goods.

Those who earned additional income in consumer goods industries will now increase their spending. By how much? C =. 75 $375 = $281. 85. This will result in additional production and factor payments. Spending will then increase. And so on.

Why is the multiplier greater than 1? As we see from the preceding illustration, a change in autonomous expenditure (in this case, I) induces a change in consumption expenditure.

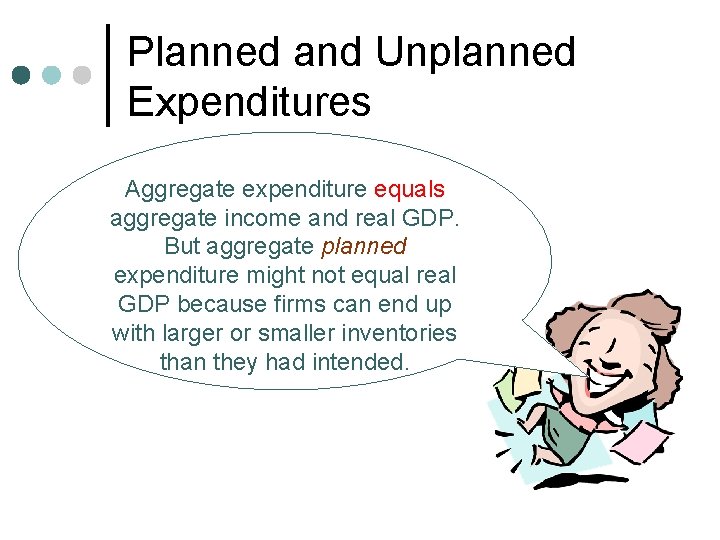

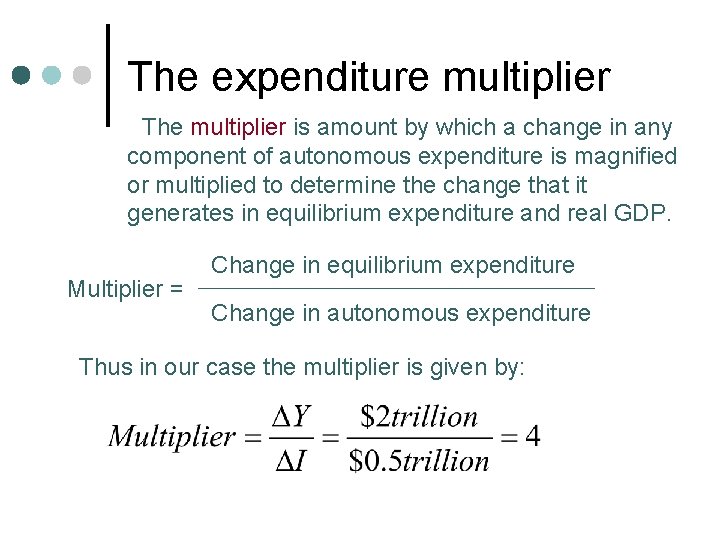

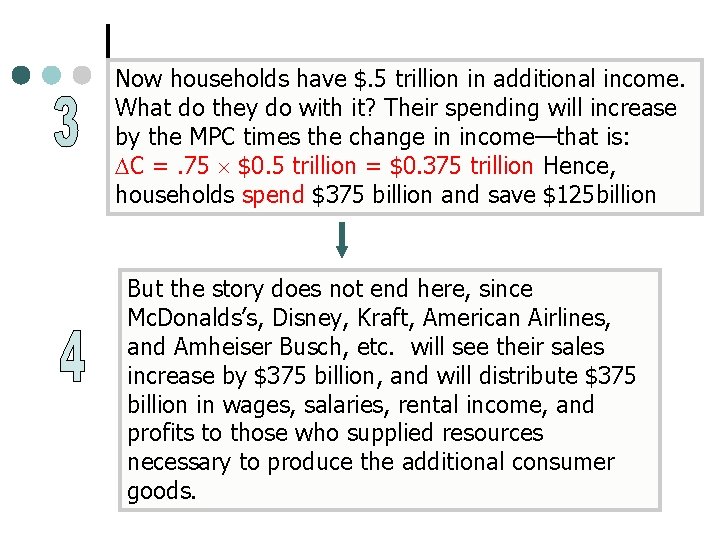

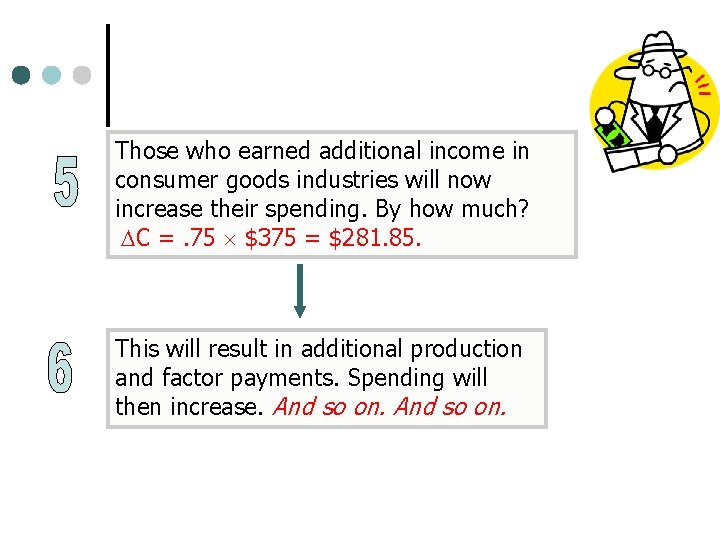

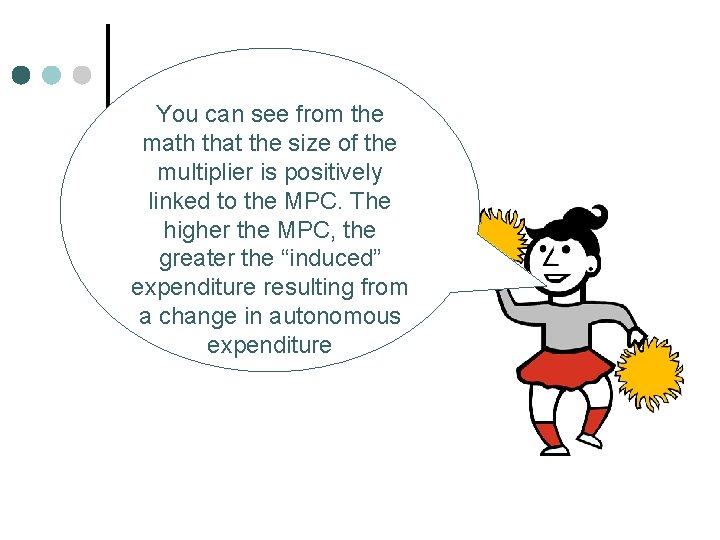

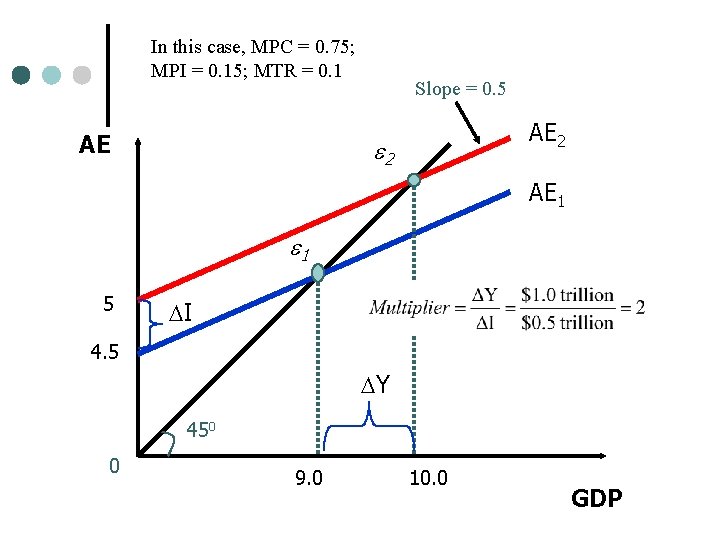

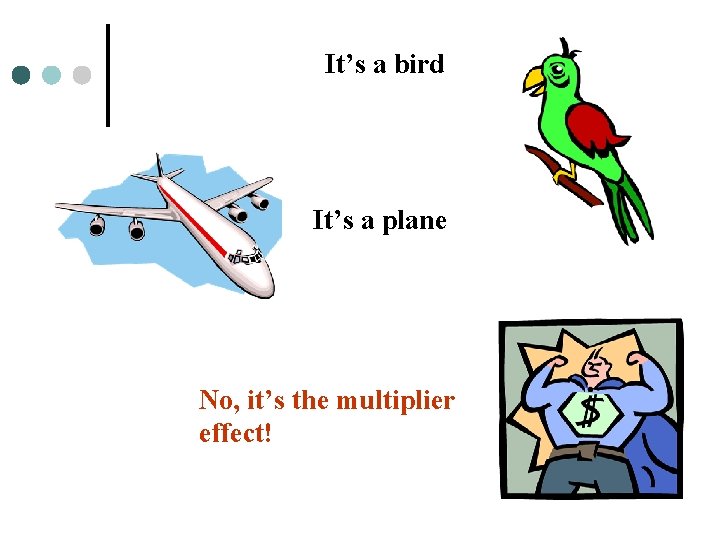

The Multiplier and the MPC We will now illustrate why the magnitude of the multiplier depends on the MPC. For the moment, assume no imports, exports, or taxes. Thus: [1] Where: [2] Now substitute [2] into [1] to obtain: [1]

![Now solve for Y 4 Now rearrange 4 5 Divide both sides of 5 Now solve for Y [4] Now rearrange [4] [5] Divide both sides of [5]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1e25a4d7c24fbe080902207c55f58f6d/image-42.jpg)

Now solve for Y [4] Now rearrange [4] [5] Divide both sides of [5] by I to obtain the multiplier The expenditure multiplier

You can see from the math that the size of the multiplier is positively linked to the MPC. The higher the MPC, the greater the “induced” expenditure resulting from a change in autonomous expenditure

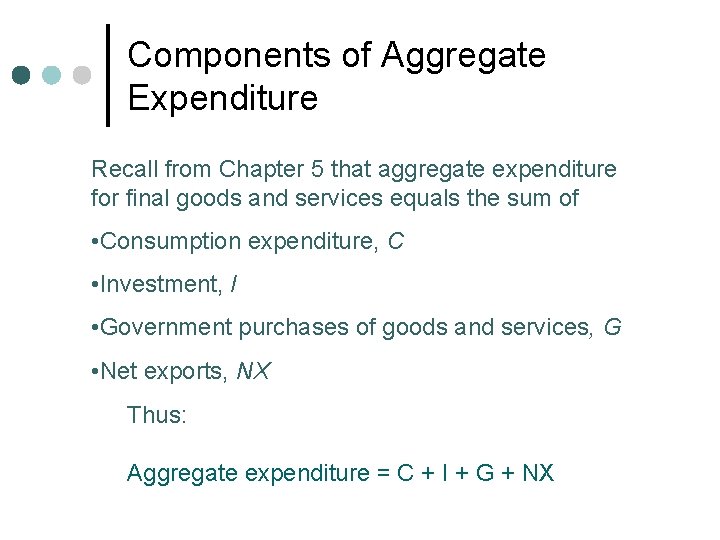

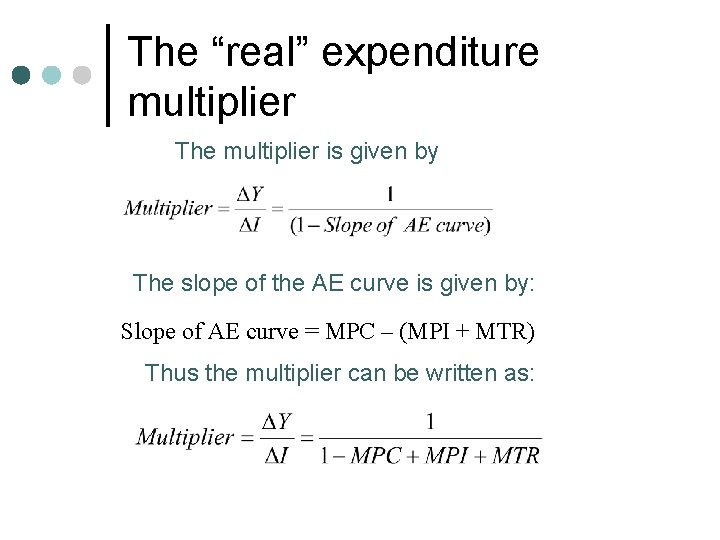

Taxes, Imports, and the Multiplier Once we allow for imports and taxes, the multiplier depends not only on the MPC, but also on the marginal propensity to import (MPI) and the marginal tax rate (MTR)

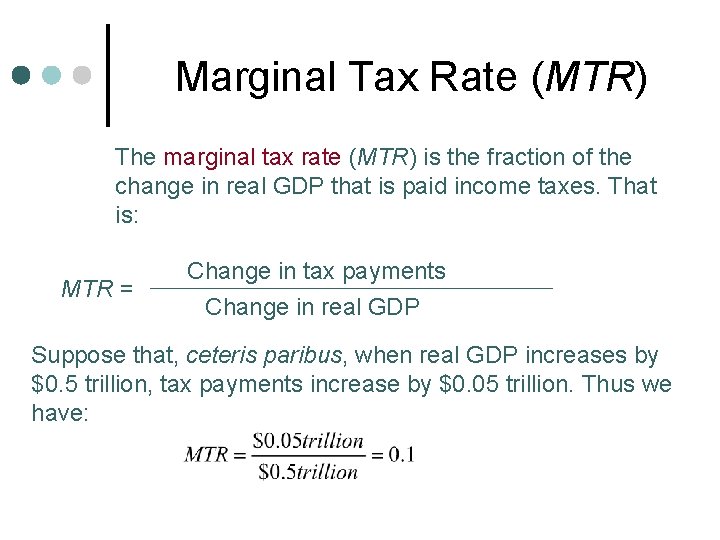

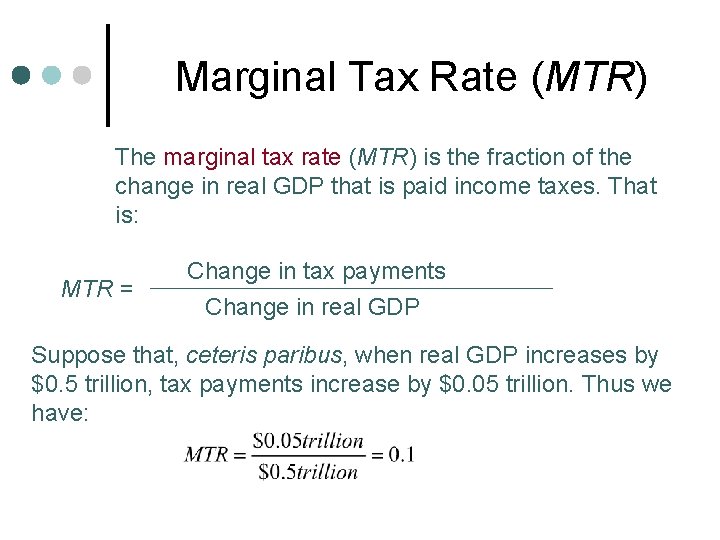

Marginal Tax Rate (MTR) The marginal tax rate (MTR) is the fraction of the change in real GDP that is paid income taxes. That is: MTR = Change in tax payments Change in real GDP Suppose that, ceteris paribus, when real GDP increases by $0. 5 trillion, tax payments increase by $0. 05 trillion. Thus we have:

The “real” expenditure multiplier The multiplier is given by The slope of the AE curve is given by: Slope of AE curve = MPC – (MPI + MTR) Thus the multiplier can be written as:

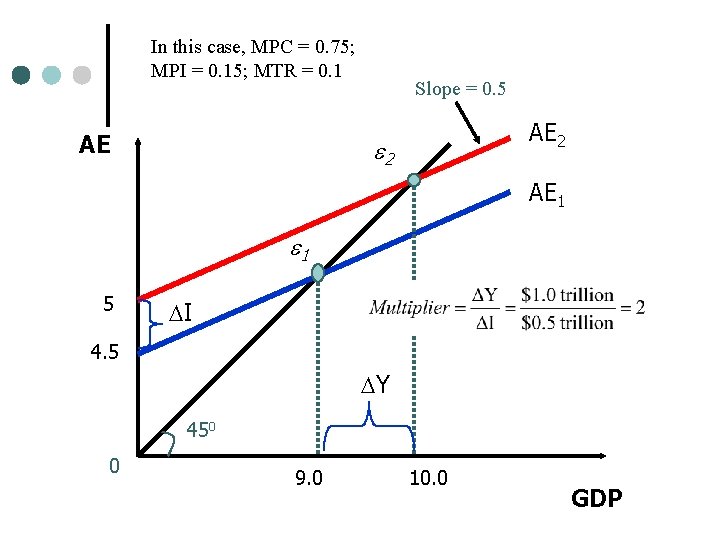

In this case, MPC = 0. 75; MPI = 0. 15; MTR = 0. 1 AE Slope = 0. 5 AE 2 2 AE 1 1 5 I 4. 5 Y 450 0 9. 0 10. 0 GDP

A wise economist asks a question

A wise economist asks a question Revenue expenditure vs capital expenditure

Revenue expenditure vs capital expenditure Meaning of revenue expenditure

Meaning of revenue expenditure What is capital and revenue expenditure

What is capital and revenue expenditure Capital and revenue expenditure

Capital and revenue expenditure Calculate aggregate expenditure

Calculate aggregate expenditure Aggregate expenditure model

Aggregate expenditure model Aggregate expenditure and equilibrium output

Aggregate expenditure and equilibrium output Aggregate line

Aggregate line Aggregate expenditures model

Aggregate expenditures model Aggregate expenditure model

Aggregate expenditure model Ad curve graph

Ad curve graph Tableau cannot mix aggregate and non aggregate

Tableau cannot mix aggregate and non aggregate Tax multiplier formula

Tax multiplier formula Unit 3 aggregate demand and aggregate supply

Unit 3 aggregate demand and aggregate supply Sras lras

Sras lras Unit 3 aggregate demand aggregate supply and fiscal policy

Unit 3 aggregate demand aggregate supply and fiscal policy Topic sentence outline example

Topic sentence outline example Outline two roles of extracellular components

Outline two roles of extracellular components Internal public relations definition

Internal public relations definition Types of planned maintenance

Types of planned maintenance Centrally planned economy

Centrally planned economy Critique of planned change

Critique of planned change Planned comparisons

Planned comparisons Planned economy

Planned economy Office 365 planned maintenance

Office 365 planned maintenance Planned maintenance system onboard ship

Planned maintenance system onboard ship Grandfolkie planned change theory

Grandfolkie planned change theory Planned giving certification

Planned giving certification Phil purcell planned giving

Phil purcell planned giving The nature of planned change

The nature of planned change Planned capacity

Planned capacity Principles of health education

Principles of health education 104-r planned academic worksheet

104-r planned academic worksheet Medfusion planned parenthood

Medfusion planned parenthood Keuntungan bagi peritel dengan lokasi yang berdiri sendiri

Keuntungan bagi peritel dengan lokasi yang berdiri sendiri Is the end result of an activity

Is the end result of an activity Planned economy

Planned economy Guided reading planned cities on the indus

Guided reading planned cities on the indus 7 step planned change process

7 step planned change process Chapter 2 section 3 centrally planned economies answer key

Chapter 2 section 3 centrally planned economies answer key Perceived obsolescence

Perceived obsolescence Planned giving and trust services

Planned giving and trust services Difference between planned and unplanned presentation

Difference between planned and unplanned presentation Disadvantages of a planned economy

Disadvantages of a planned economy Planned comparisons example

Planned comparisons example Lift slab operations must be designed and planned by

Lift slab operations must be designed and planned by Types of admission hospital

Types of admission hospital