Ways of Acquiring Word Meanings I Sources of

- Slides: 34

Ways of Acquiring Word Meanings I. Sources of information about a word’s meaning: A. Syntax B. Linguistic context C. Nonlinguistic context D. Speaker’s behavior (e. g. , eyegaze, gestures) E. Prior Knowledge F. Intonation II. Many such sources are weak or unavailable to children first acquiring language III. The problem of induction IV. Constraints as a partial solution A. The whole object assumption B. The taxonomic assumption C. Mutual exclusivity

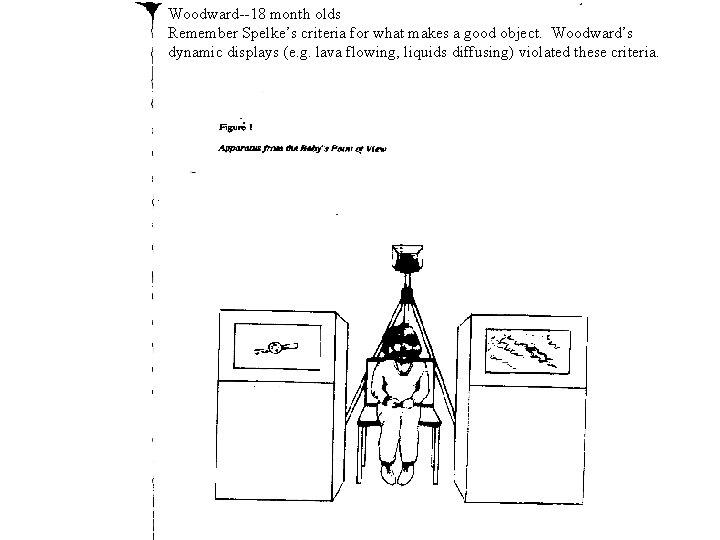

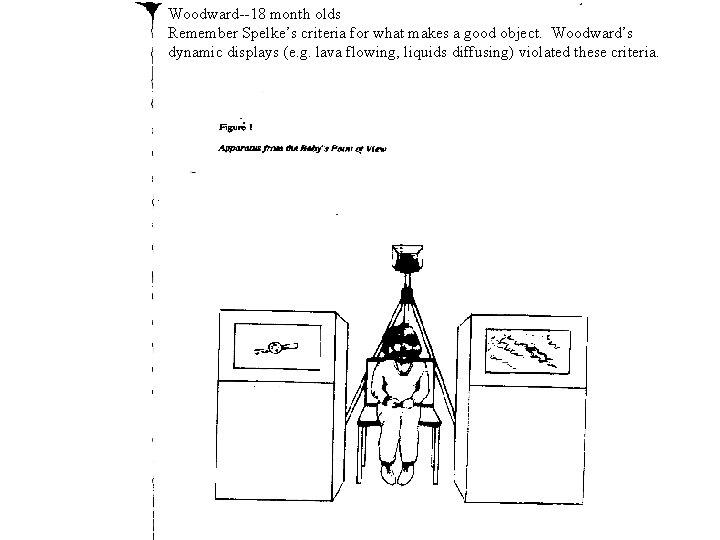

Woodward--18 month olds Remember Spelke’s criteria for what makes a good object. Woodward’s dynamic displays (e. g. lava flowing, liquids diffusing) violated these criteria. .

The taxonomic assumption: Children extend a novel term to entities of the same kind. They extend object labels to other similar objects, rather than to objects that are thematically related. Why is there a need for such an assumption?

Mututal exclusivity: children prefer to have only one category label for each object. children should resist second labels for objects indirect word learning possible: children can infer the appropriate referent for an object helps overcome the whole object assumption freeing children to learn terms for parts, substance, color, etc.

Indirect word learning results: Evidence for a lexical or pragmatic constraint? Pragmatic principles suggested as alternatives to mutual exclusivity: Lexical gap filling If she meant “x, ” she would have said “x”.

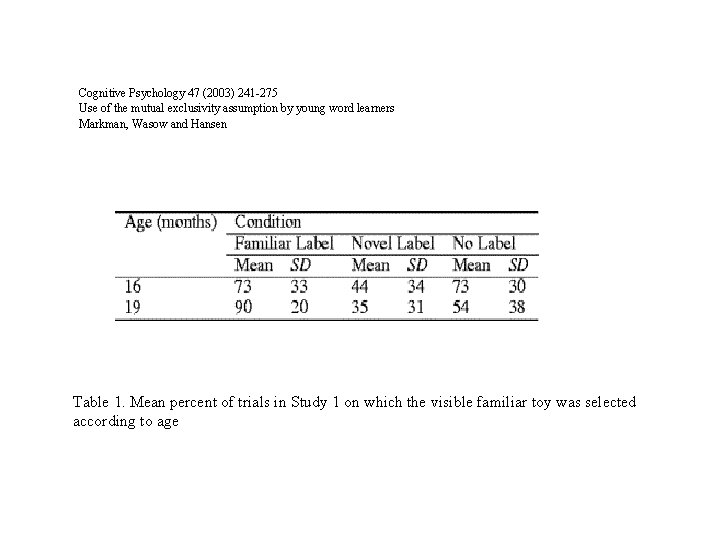

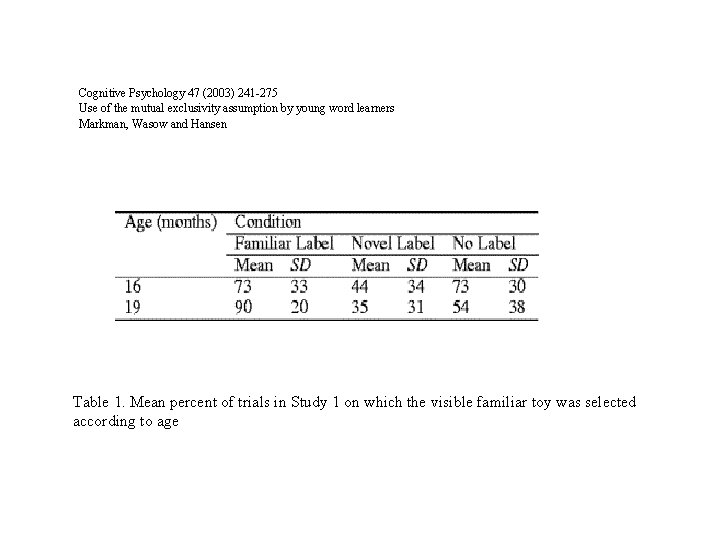

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 1. Mean percent of trials in Study 1 on which the visible familiar toy was selected according to age

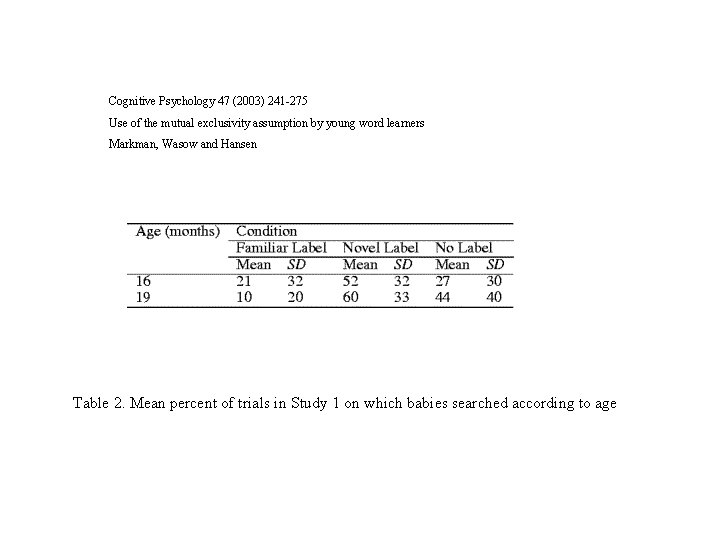

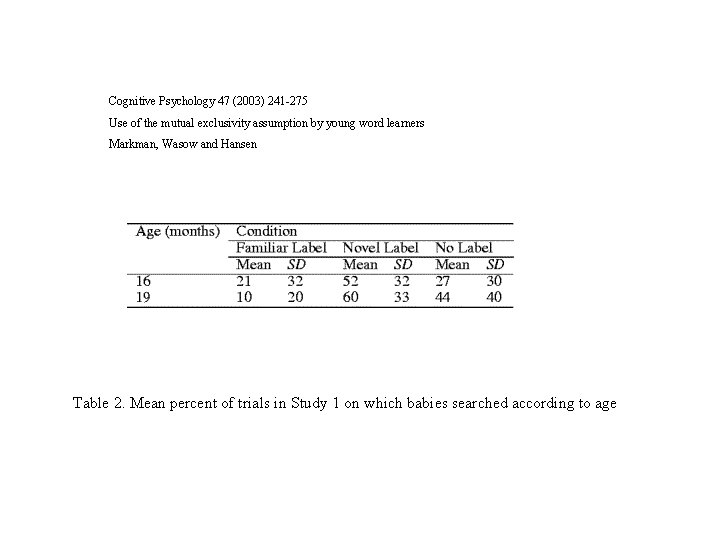

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 2. Mean percent of trials in Study 1 on which babies searched according to age

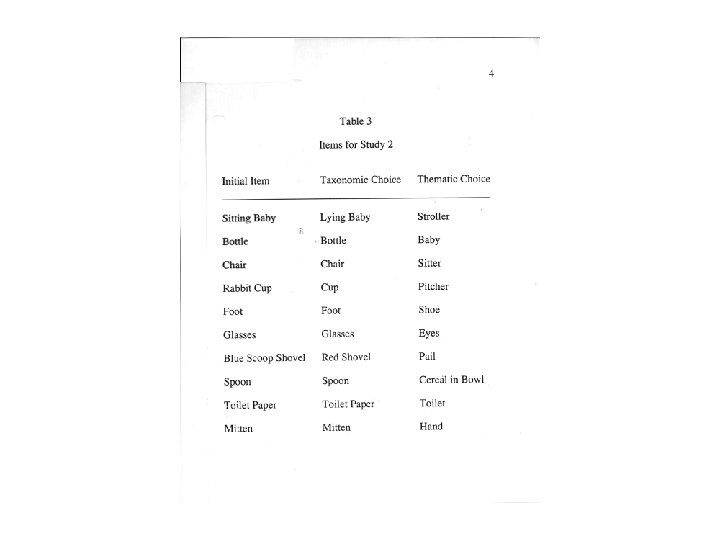

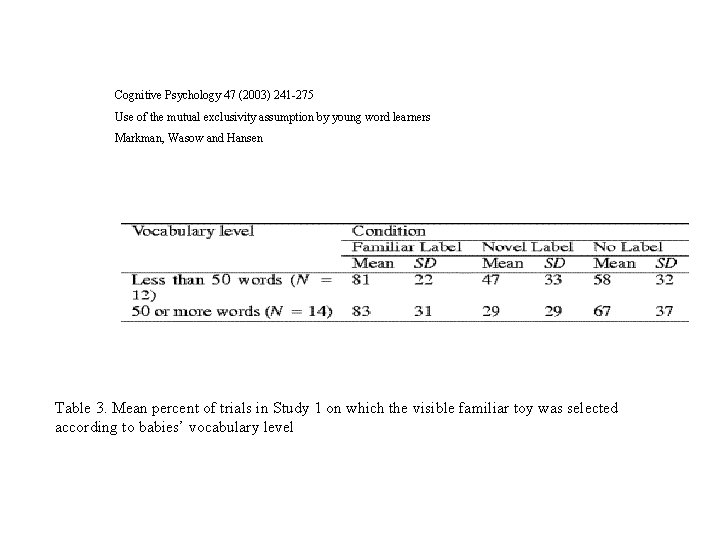

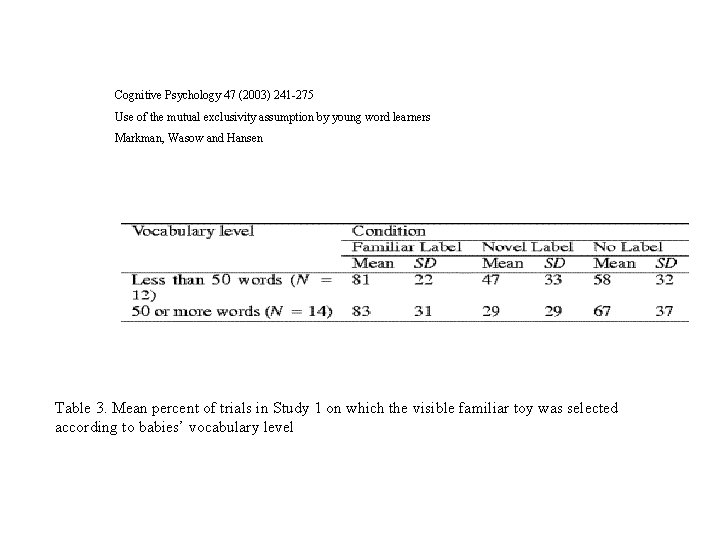

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 3. Mean percent of trials in Study 1 on which the visible familiar toy was selected according to babies’ vocabulary level

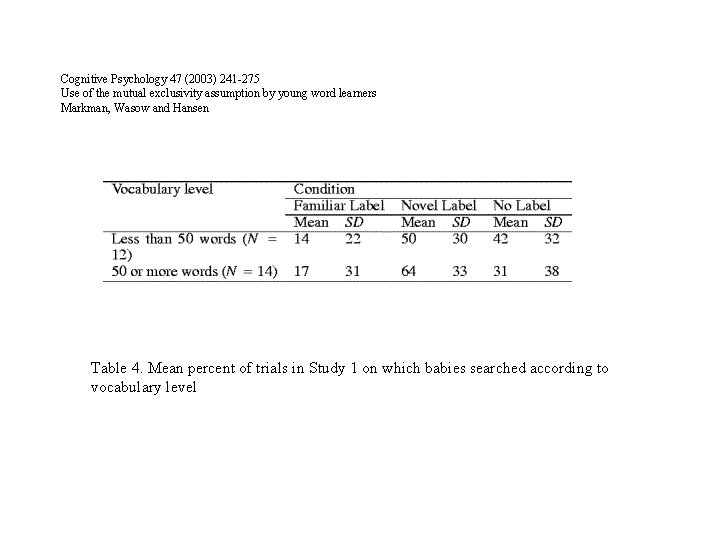

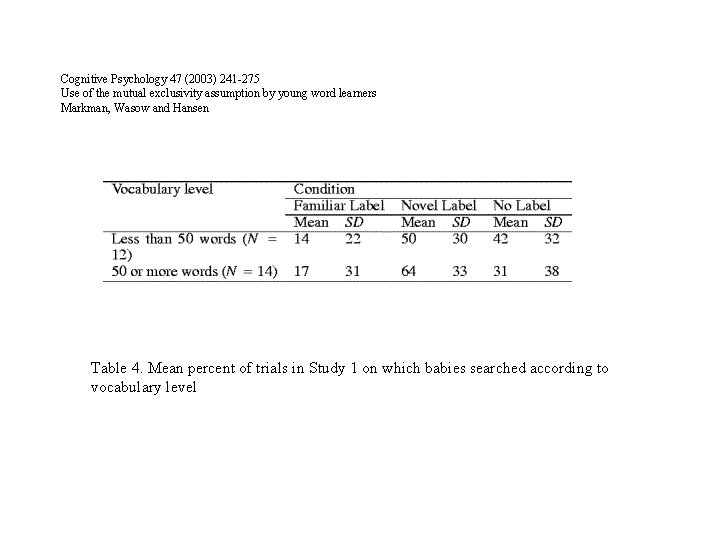

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 4. Mean percent of trials in Study 1 on which babies searched according to vocabulary level

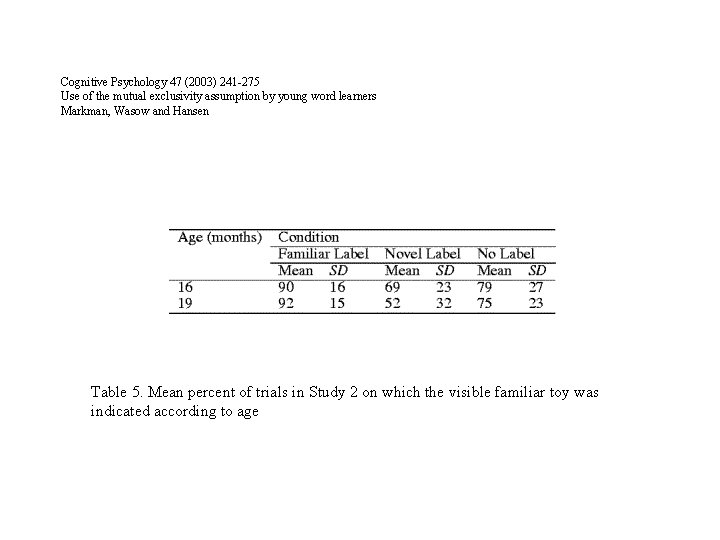

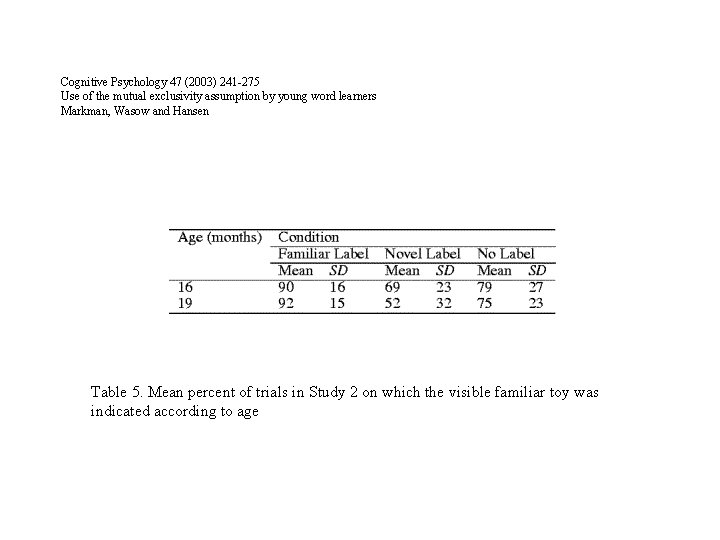

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 5. Mean percent of trials in Study 2 on which the visible familiar toy was indicated according to age

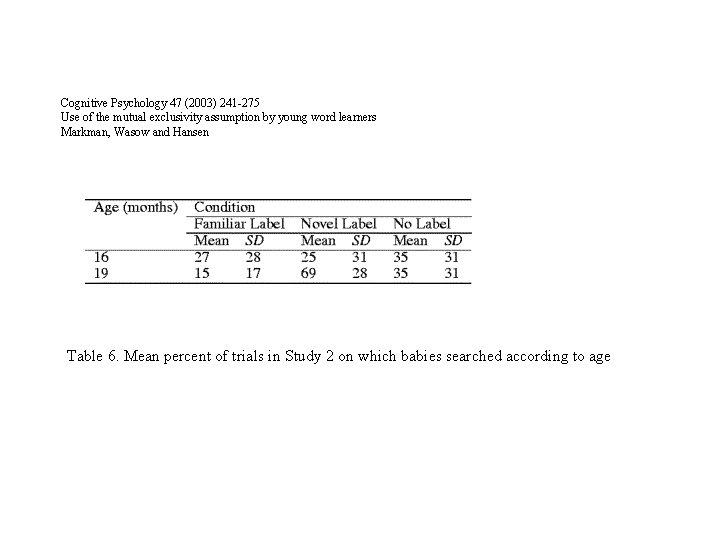

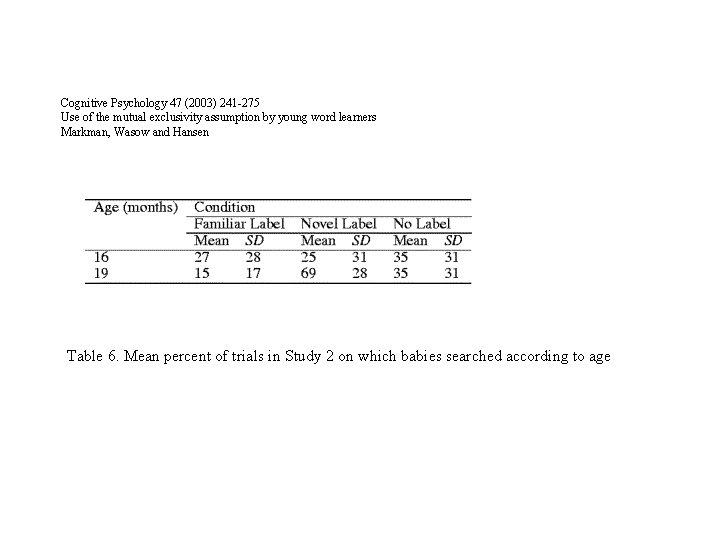

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 6. Mean percent of trials in Study 2 on which babies searched according to age

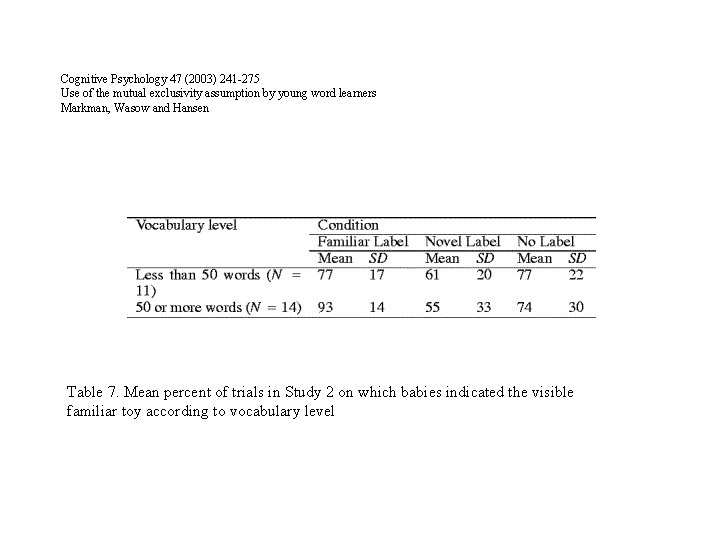

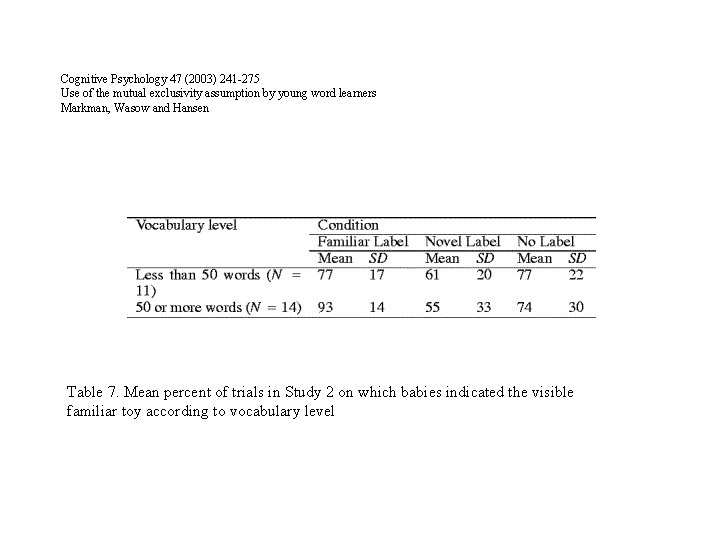

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 7. Mean percent of trials in Study 2 on which babies indicated the visible familiar toy according to vocabulary level

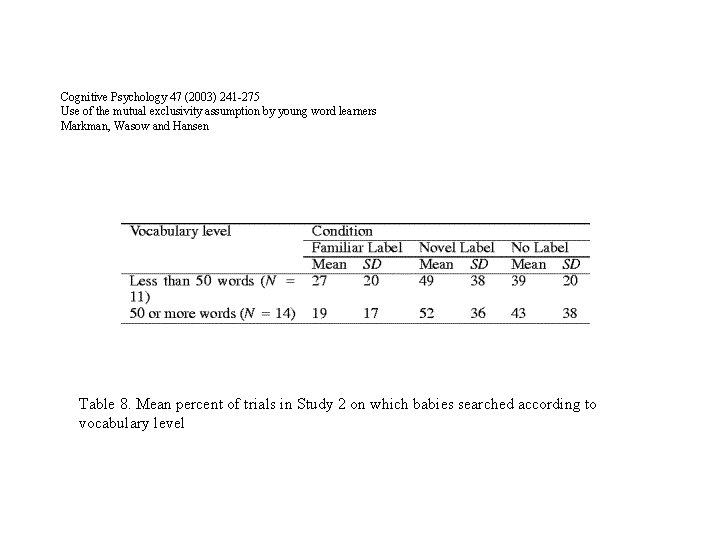

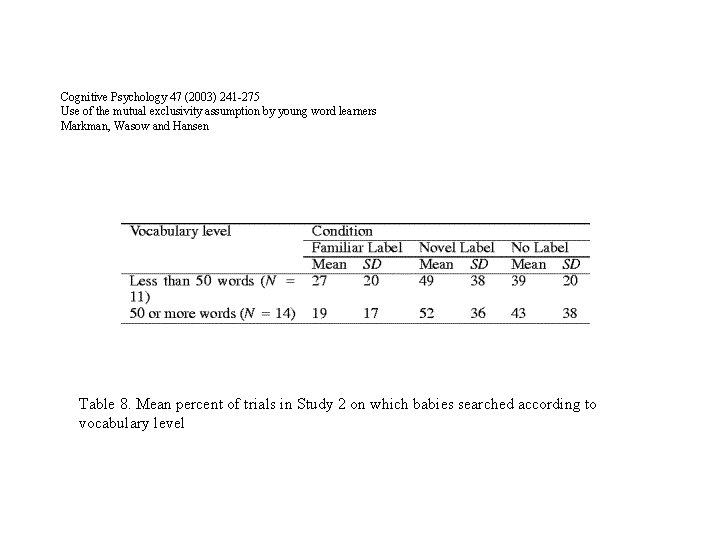

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 8. Mean percent of trials in Study 2 on which babies searched according to vocabulary level

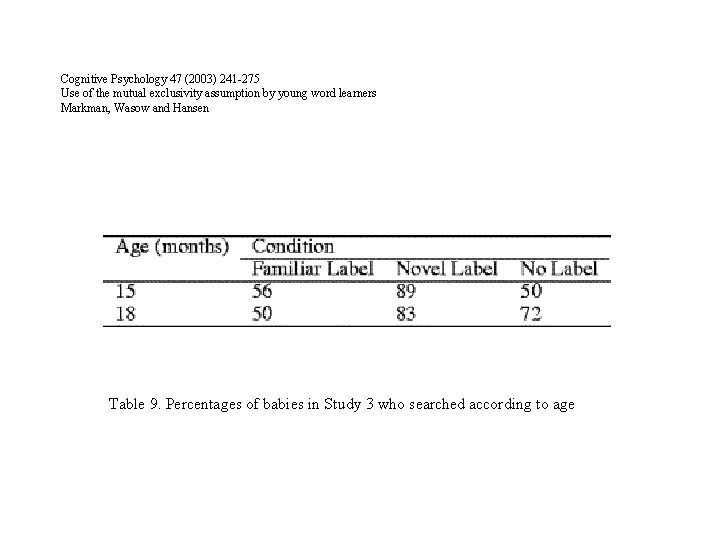

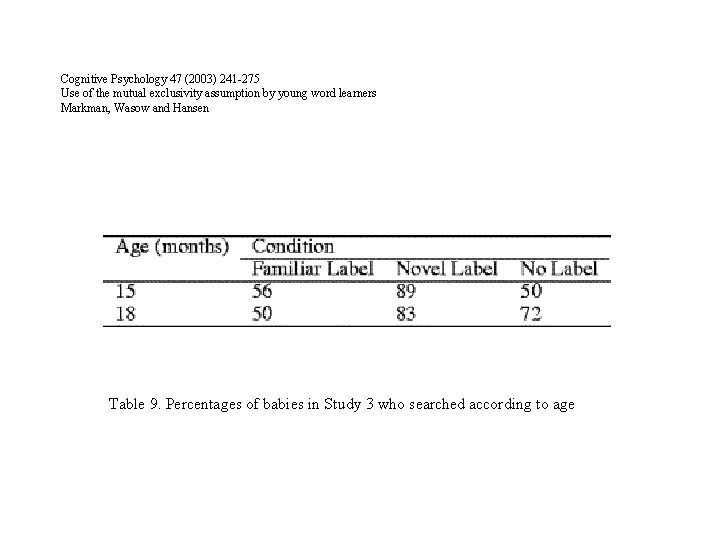

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 9. Percentages of babies in Study 3 who searched according to age

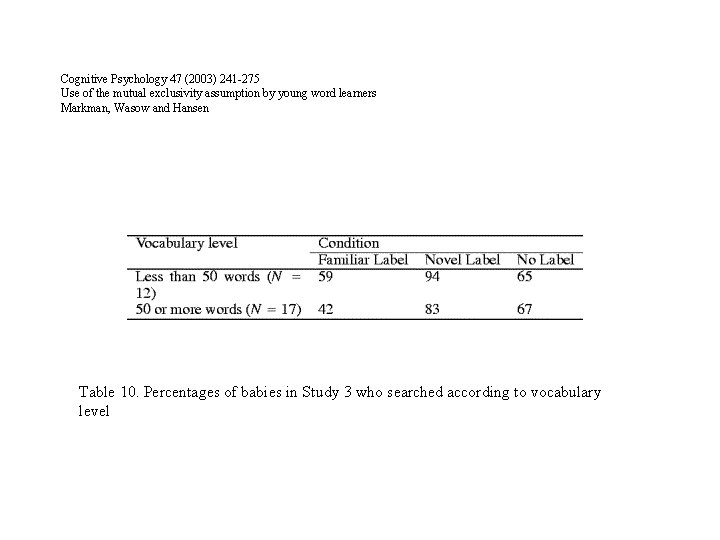

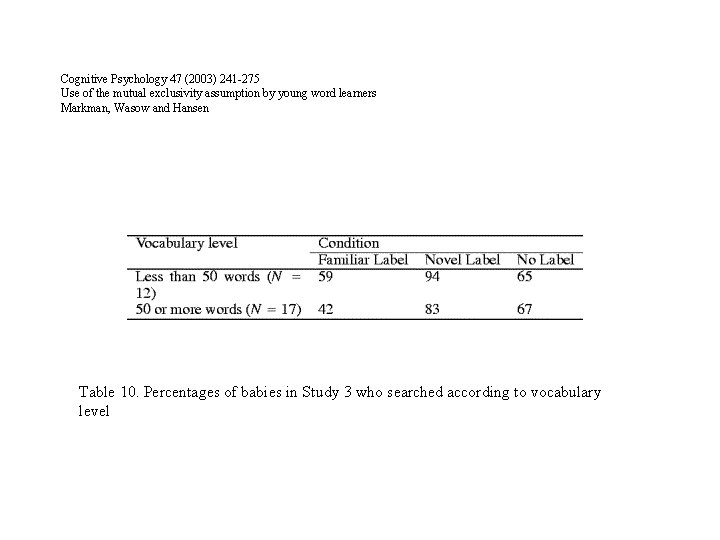

Cognitive Psychology 47 (2003) 241 -275 Use of the mutual exclusivity assumption by young word learners Markman, Wasow and Hansen Table 10. Percentages of babies in Study 3 who searched according to vocabulary level

Rejection of second labels

Enables children to reject a second label for the whole object, thereby freeing them to learn terms for parts, substances, color etc.

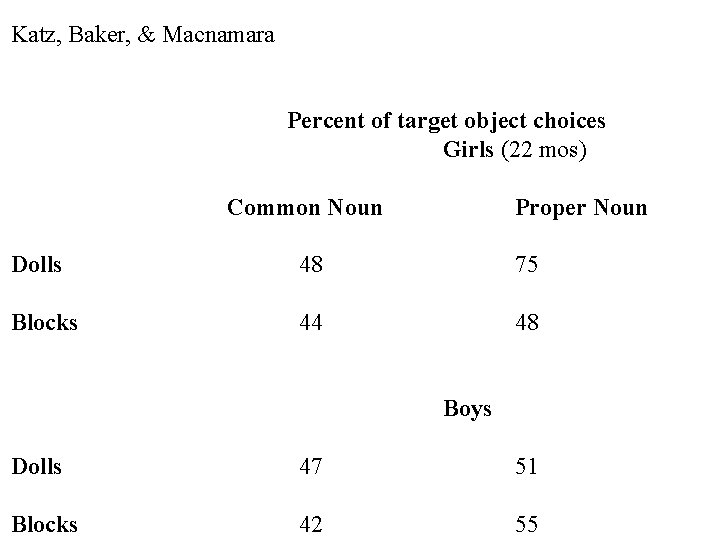

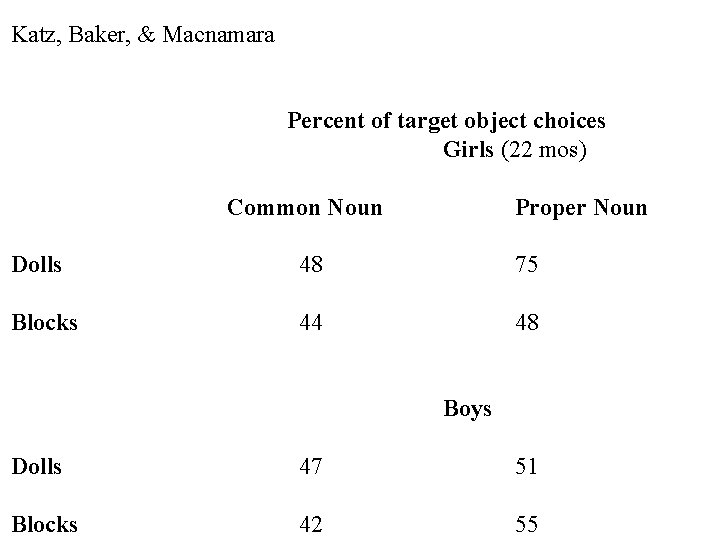

Katz, Baker, & Macnamara Percent of target object choices Girls (22 mos) Common Noun Proper Noun Dolls 48 75 Blocks 44 48 Boys Dolls 47 51 Blocks 42 55

What are the different methods of acquiring knowledge

What are the different methods of acquiring knowledge Print sources of information

Print sources of information Importance of water resource management

Importance of water resource management Armadillo roadkill writing

Armadillo roadkill writing Gods ways are not our ways

Gods ways are not our ways Naylor meaning

Naylor meaning Nuance vs subtle

Nuance vs subtle The process of acquiring through experience new

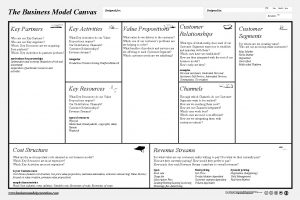

The process of acquiring through experience new Key partners in business model

Key partners in business model Three principles of acquiring spiritual knowledge

Three principles of acquiring spiritual knowledge Acquiring capital to implement strategies

Acquiring capital to implement strategies Strategies for acquiring it applications

Strategies for acquiring it applications Acquiring the reflectance field of a human face

Acquiring the reflectance field of a human face Acquire spiritual knowledge

Acquire spiritual knowledge Platt amendment significance

Platt amendment significance Acquiring new lands section 3

Acquiring new lands section 3 Business model canvas examples

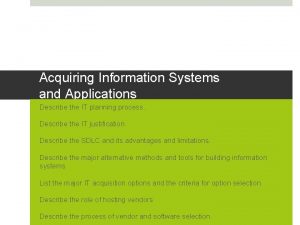

Business model canvas examples Acquiring information systems and applications

Acquiring information systems and applications Process of acquiring training appraising and compensating

Process of acquiring training appraising and compensating 1. the ability to produce valued outcomes in a novel way

1. the ability to produce valued outcomes in a novel way Means acquiring goods and or services

Means acquiring goods and or services Acquiring information systems and applications

Acquiring information systems and applications Methods of acquiring information

Methods of acquiring information What factors did you consider in acquiring territories?

What factors did you consider in acquiring territories? Learning means acquiring knowledge

Learning means acquiring knowledge Acquiring spiritual knowledge

Acquiring spiritual knowledge Acquiring information systems and applications

Acquiring information systems and applications Weather map symbols and meanings

Weather map symbols and meanings Venn diagram of vector and scalar

Venn diagram of vector and scalar Green true colors

Green true colors Tlingit totem pole meanings

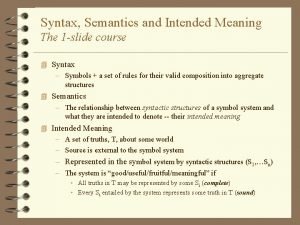

Tlingit totem pole meanings Syntax symbols and meanings

Syntax symbols and meanings What is symbol in literature

What is symbol in literature Espn fantasy baseball symbol meanings

Espn fantasy baseball symbol meanings Statistical symbols and meanings

Statistical symbols and meanings