UTI Ref Management of Urological Emergencies 2004 Taylor

- Slides: 29

UTI 梅健泰 Ref. : Management of Urological Emergencies, 2004, Taylor & Francies

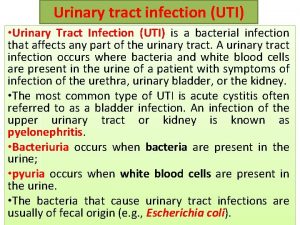

UTI - DEFINITIONS • Bacteriuria : the presence of bacteria in the urine from upper and lower urinary tract sources with the presence or absence of both pyuria and symptoms. • Urinary tract infection (UTI) : occurs when a microbial agent, usually bacterial, invades and colonizes the urinary tract. – Uncomplicated UTIs (simple UTIs) : in a structurally and functionally normal urinary tract, when the patient is not pregnant, and when there is no history of recent antimicrobial use. • eg. most isolated or recurrent lower UTIs and acute pyelonephritis in female patients. • Uncomplicated pyelonephritis, as an example, accounts for approximately 25% of all UTI-related admissions for inpatient treatment. – Complicated UTIs : in a structurally and/or functionally abnormal urinary tract. • eg. secondary to urinary tract catheterization, urolithiasis, obstructive uropathy, instrumentation, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, immunosuppression and congenital or secondary variations of urinary tract anatomy such as prune belly syndrome, ileal conduits and bladder augmentation

UTI - INCIDENCE • Female : Male = ~30: 1 • Young children : M > F ( up to approximately 6 months of age). • In female : the incidence of UTIs increases with advancing age. – Approximately 1% of girls 5 -15 years of age (bacteriuria). – 5% in early adulthood (bacteriuria). – Up to 30% between 20 and 40 years : experience an acute bacterial UTI requiring treatment. • Approximately 20% of women and 10% of men over 70 years of age will have bacteriuria upon culture of their urine.

UTI - PATHOGENESIS • Ascending route : most commonly, bacteria enter the bladder via the urethra. – Large bowel commensal organisms colonizing the perineum, the perianal region – the prepuce in the male • Hematogenous and lymphatic pathways : far less common, the spread of bacteria from adjacent organs.

RISK FACTORS FOR URINARY TRACT INFECTION • Host factors – urinary stasis, local trauma, abnormal urinary tract anatomy and function, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, debility, poor hygiene and aging. • Factors specific to females – deficient estrogen status and short urethral length. • Mechanical and other factors mediate the ability of the enterobacteria to colonize, invade and damage the urinary tract. – In women • sexual intercourse, especially with a new partner, unusually vigorous intercourse, delayed postcoital micturition, history of previous UTIs, and the use of spermicide and contraceptive diaphragms. – Elderly patients have an increased incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and UTI • • reduced urogenital estrogen, reduced nutritional status, an inability to maintain body homeostasis, poorer bowel function, increased comorbidities and a greater incidence of dysfunctional voiding. Foreign bodies - breaching natural defense mechanisms – external urinary drainage devices such as indwelling urethral catheters, suprapubic catheters and nephrostomy drainage tubes. • Dysfunctional voiding in the male – high voiding pressures and grossly elevated residual volumes • Augmentation or substitution of the lower urinary tract with bowel segments

DM & UTI • • A common multisystem disease with potentially serious effects on urinary tract anatomy and function. Complications – diabetic nephropathy, papillary necrosis, renal artery stenosis, and diabetic cystopathy. • • • Bacteriuria is twice as common in glycosuric and diabetic patients. A higher incidence of complicated upper and lower UTIs, such as renal and perinephric abscesses, emphysematous pyelonephritis, emphysematous cystitis, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and fungal infections. A strong association with Fournier's gangrene, a life-threatening synergistic infection. Morbidity and potential mortality is greater in diabetic patients with UTIs. Added risk of contrast nephropathy, – especially in those patients with reduced renal function, dehydration, sepsis or treat with metformin (Glucophage or Glucomine). • The clinical condition of the diabetic patient may deteriorate rapidly and response may be suboptimal with more conservative treatment strategies.

COMMON ORGANISMS - UTI • • Commensal organisms in the large bowel , aerobic Gram-negative rods- most common. Community or hospital acquired - different pathogenic organism and antibiotic sensitivity. – Community-acquired infections: • • • Most commonly: Escherichia coli (80%). Other enterobacteria: Proteus mirabilis and Klebsiela spp. Gram-positive organisms: Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus saprophyticus. – Nosocomial infections: • • • E. coli (50%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiela spp. , Enterobacter spp. , Citrobacter, Serratia marcescens, Providencia stuartii and S. epidermidis Often more resistant to frequently prescribed antibiotics. Less common causative organisms in the presence of a grossly abnormal urinary tract, immunosuppression or a foreign body. – Fungi such as Candida albicans, Mycoplasma species including Ureaplasma urealyticum, and viral organisms such as Adenovirus in immunosuppressed bone marrow transplant recipients. • Urethral infections – Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, U. urealyticum, and occasionally Gardnerella vaginalis.

Indwelling urinary catheters & UTI • Indwelling urinary catheters: the most common source of nosocomial infections and Gram-negative bacteremia in the hospital environment. – Approximately 1— 2% risk of infection with a single catheter passage – Directly related to the duration of catheterization, with the risk of bacteriuria increasing by • ~10% per day postinsertion in women • ~3 -4% per day in men. • Source of this infection – – via the catheter, the periurethral region, the drainage bag, or connector disruption with contamination. • Catheterization < 5 days - bacteriuria from short-term catheterization usually clears quickly. • Long-term catheterization – – Breach in the natural defense mechanisms – Direct reservoir for bacteria due to adherence to the catheter surface – Upon removal of a long-term catheter, clearance of bacteriuria may be improved by administering a short course of antimicrobials.

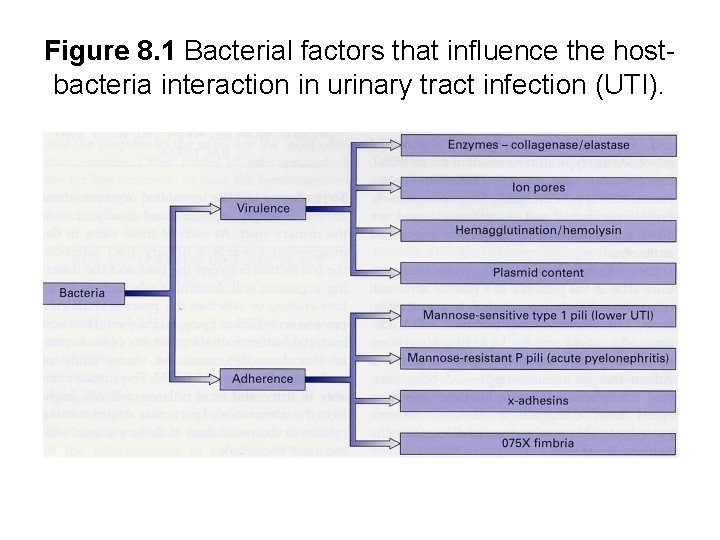

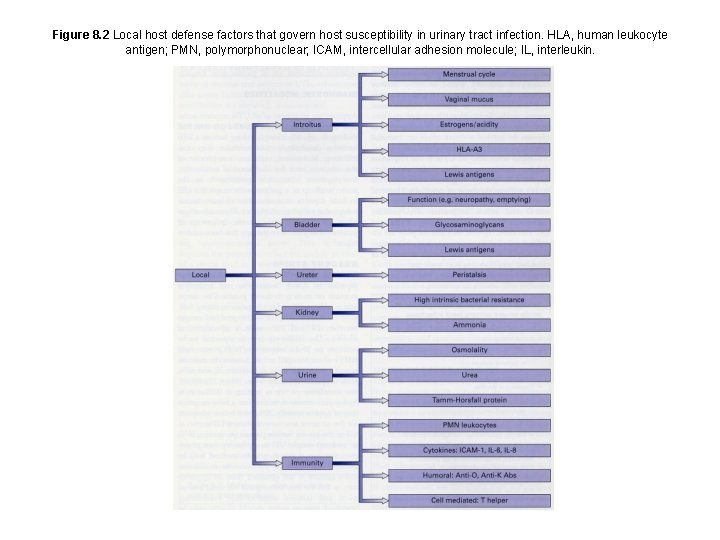

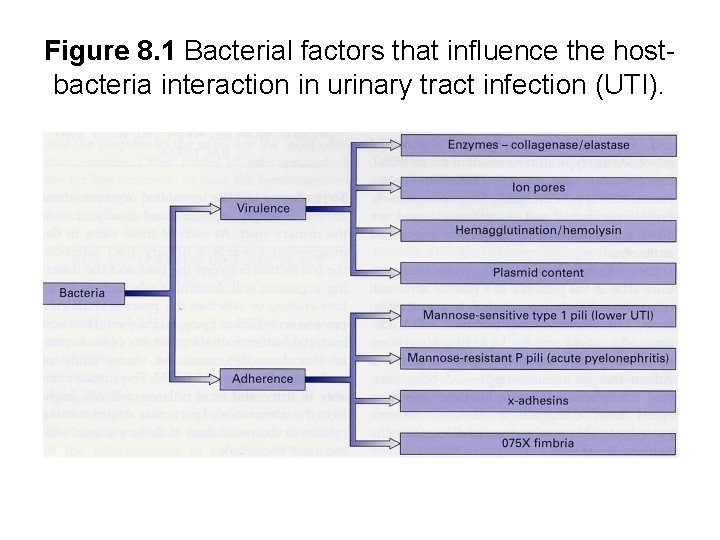

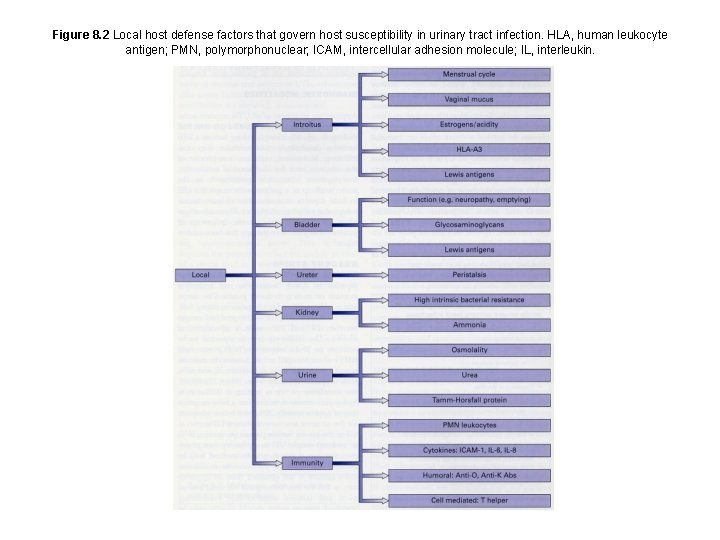

INTERACTION BETWEEN THE HOST AND BACTERIA • To produce a UTI – Adhere – Multiply – Colonize – Invade the urinary tract • BACTERIAL FACTORS (FIGURE 8. 1) • HOST DEFENSE (FIGURE 8. 2)

Figure 8. 1 Bacterial factors that influence the hostbacteria interaction in urinary tract infection (UTI).

Figure 8. 2 Local host defense factors that govern host susceptibility in urinary tract infection. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; PMN, polymorphonuclear; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin.

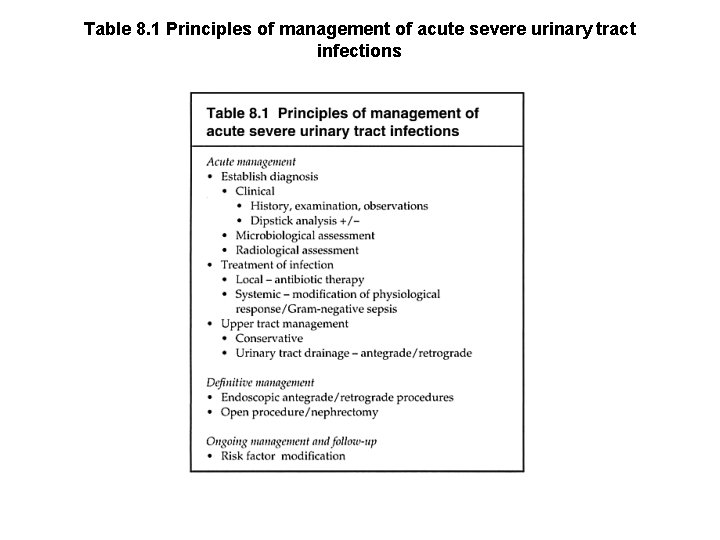

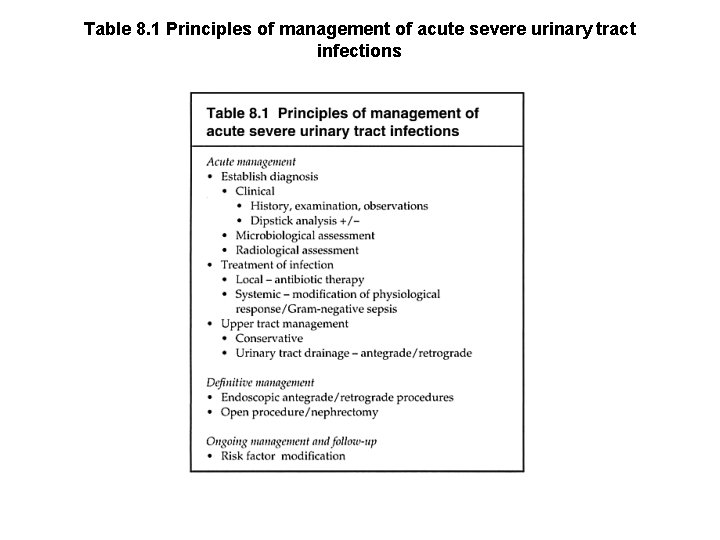

Table 8. 1 Principles of management of acute severe urinary tract infections

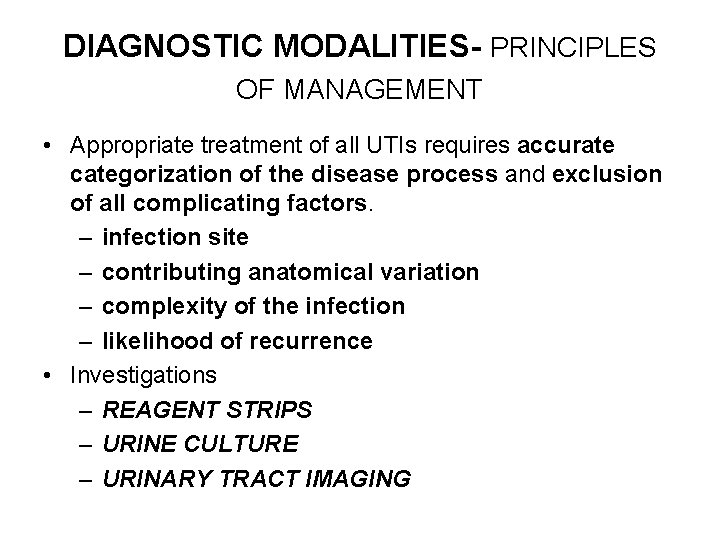

DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT • Appropriate treatment of all UTIs requires accurate categorization of the disease process and exclusion of all complicating factors. – infection site – contributing anatomical variation – complexity of the infection – likelihood of recurrence • Investigations – REAGENT STRIPS – URINE CULTURE – URINARY TRACT IMAGING

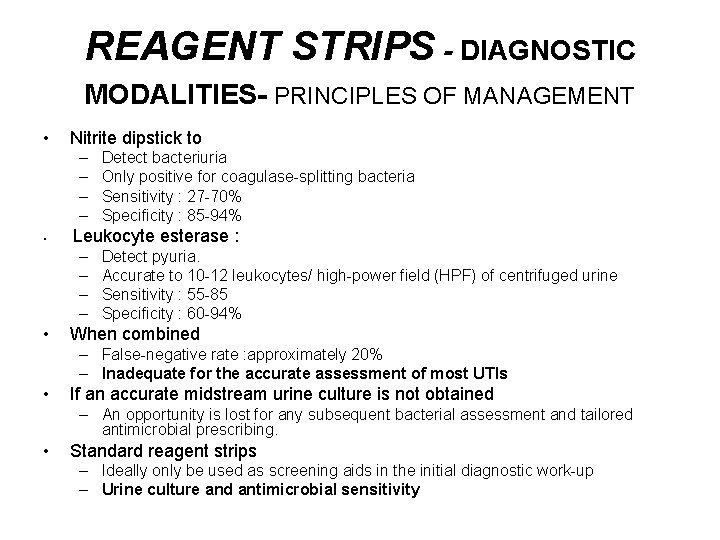

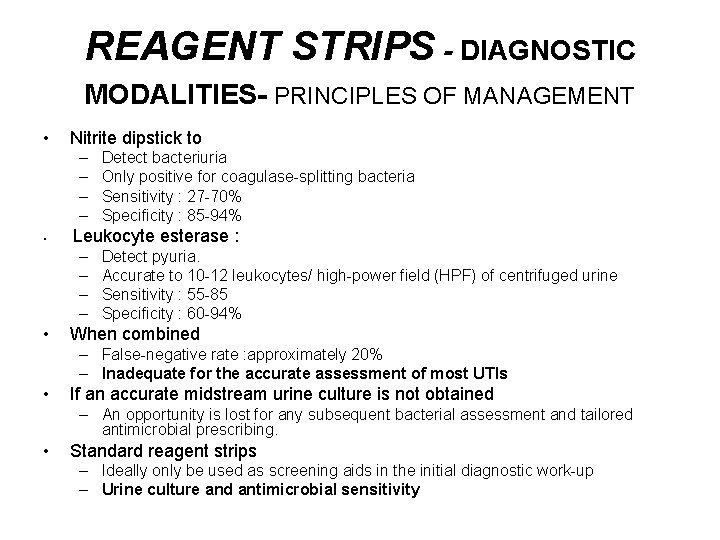

REAGENT STRIPS - DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT • Nitrite dipstick to – – • Leukocyte esterase : – – • Detect bacteriuria Only positive for coagulase-splitting bacteria Sensitivity : 27 -70% Specificity : 85 -94% Detect pyuria. Accurate to 10 -12 leukocytes/ high-power field (HPF) of centrifuged urine Sensitivity : 55 -85 Specificity : 60 -94% When combined – False-negative rate : approximately 20% – Inadequate for the accurate assessment of most UTIs • If an accurate midstream urine culture is not obtained – An opportunity is lost for any subsequent bacterial assessment and tailored antimicrobial prescribing. • Standard reagent strips – Ideally only be used as screening aids in the initial diagnostic work-up – Urine culture and antimicrobial sensitivity

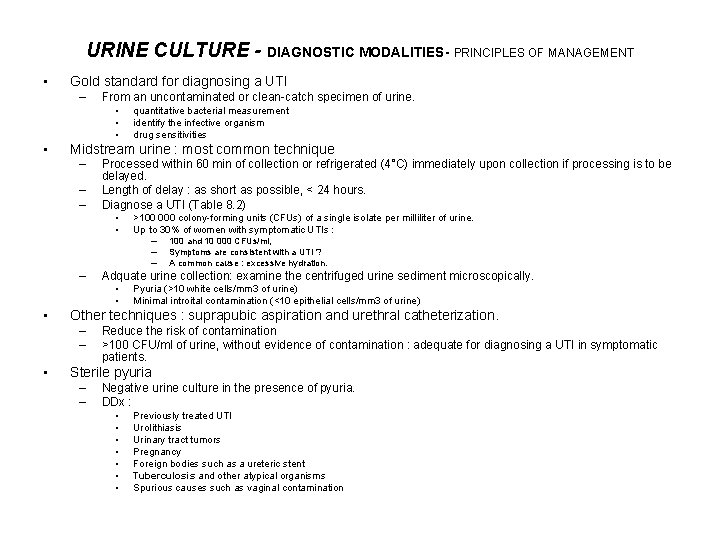

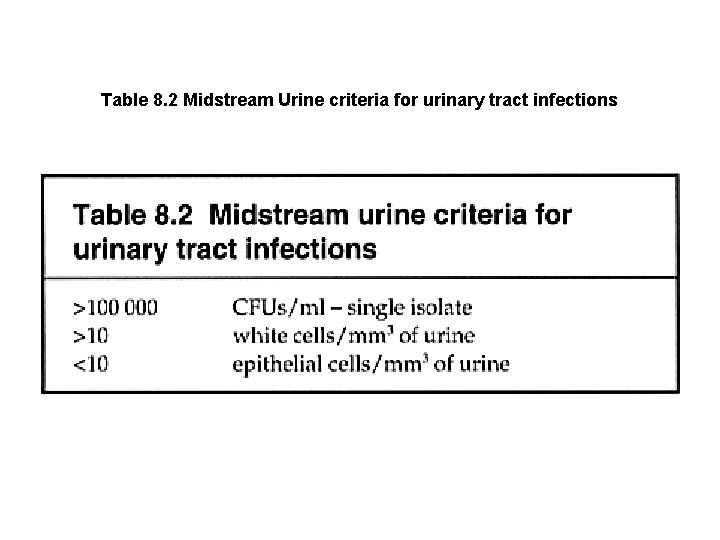

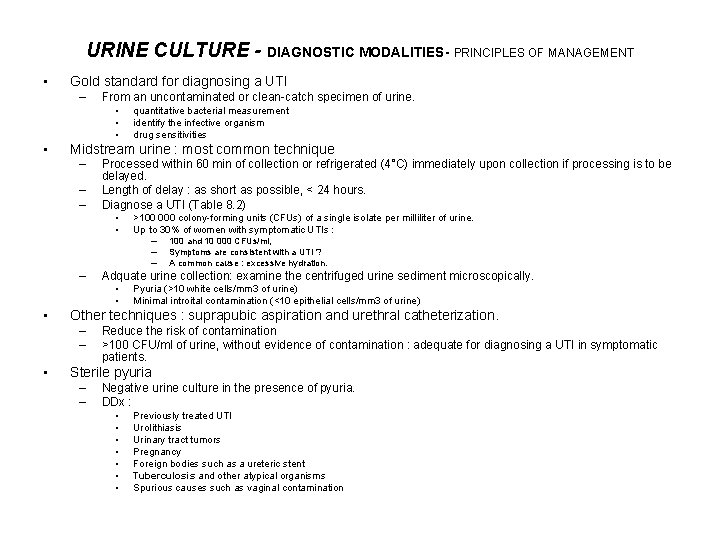

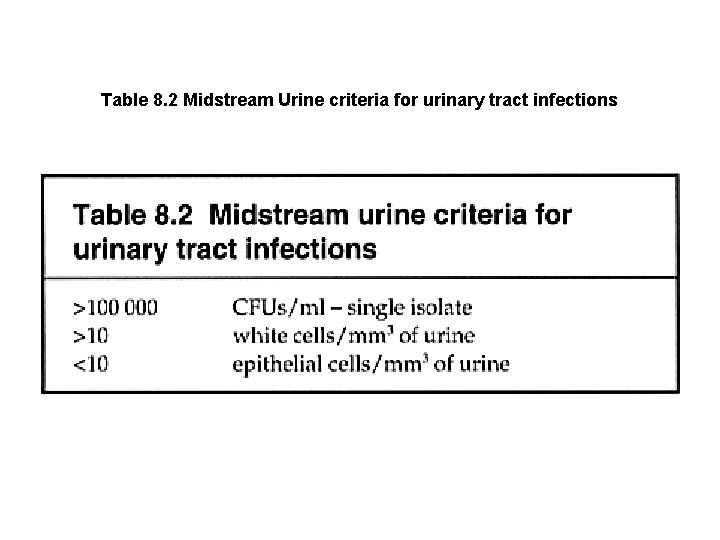

URINE CULTURE - DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT • Gold standard for diagnosing a UTI – From an uncontaminated or clean-catch specimen of urine. • • quantitative bacterial measurement identify the infective organism drug sensitivities Midstream urine : most common technique – – – Processed within 60 min of collection or refrigerated (4°C) immediately upon collection if processing is to be delayed. Length of delay : as short as possible, < 24 hours. Diagnose a UTI (Table 8. 2) • • >100 000 colony-forming units (CFUs) of a single isolate per milliliter of urine. Up to 30% of women with symptomatic UTIs : – – Adquate urine collection: examine the centrifuged urine sediment microscopically. • • • Pyuria (>10 white cells/mm 3 of urine) Minimal introital contamination (<10 epithelial cells/mm 3 of urine) Other techniques : suprapubic aspiration and urethral catheterization. – – • 100 and 10 000 CFUs/ml, Symptoms are consistent with a UTI ? A common cause : excessive hydration. Reduce the risk of contamination >100 CFU/ml of urine, without evidence of contamination : adequate for diagnosing a UTI in symptomatic patients. Sterile pyuria – – Negative urine culture in the presence of pyuria. DDx : • • Previously treated UTI Urolithiasis Urinary tract tumors Pregnancy Foreign bodies such as a ureteric stent Tuberculosis and other atypical organisms Spurious causes such as vaginal contamination

Table 8. 2 Midstream Urine criteria for urinary tract infections

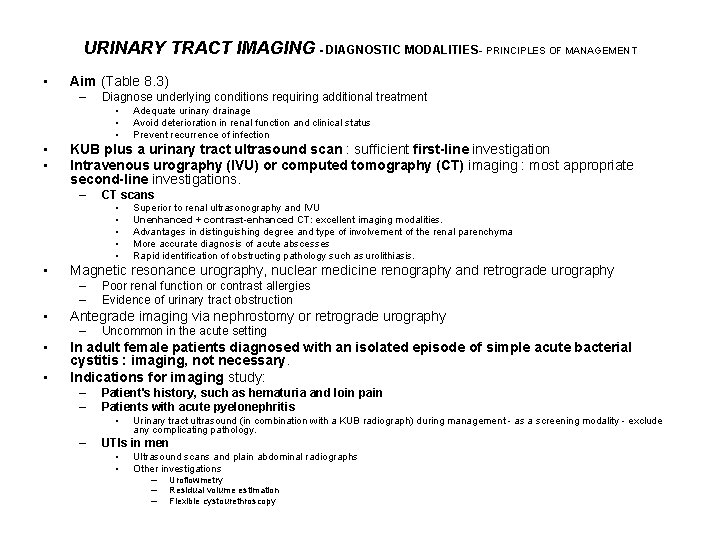

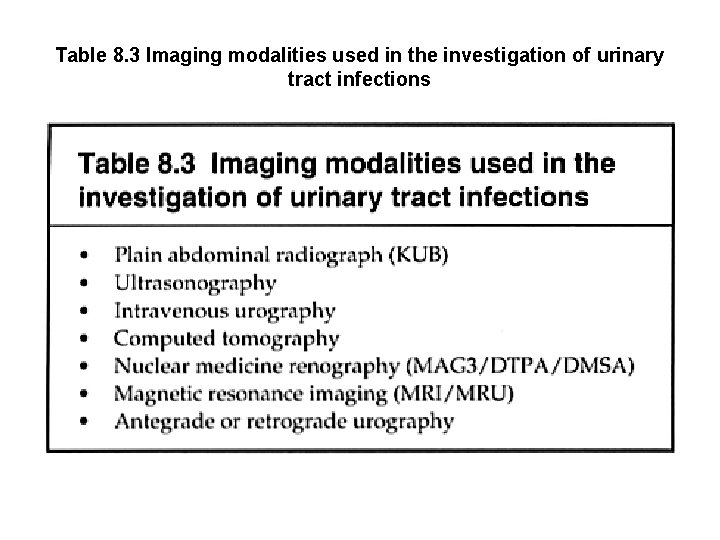

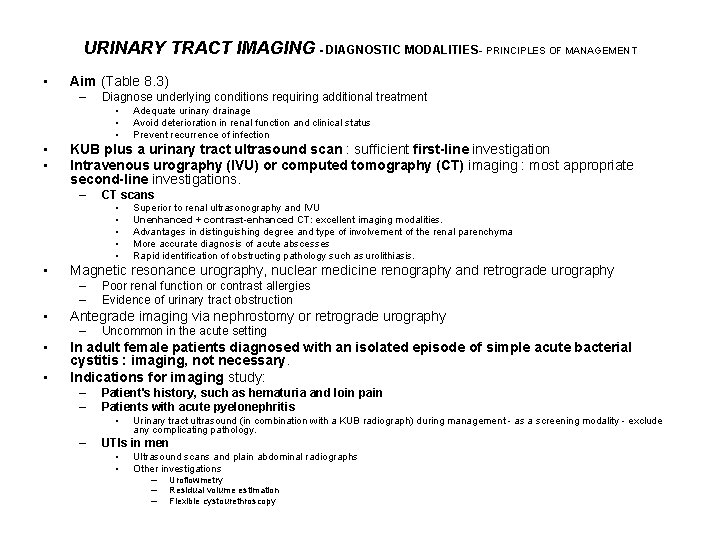

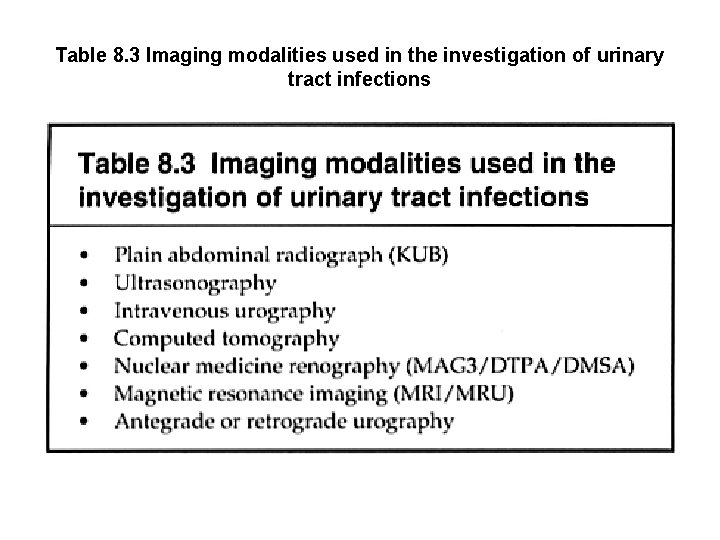

URINARY TRACT IMAGING - DIAGNOSTIC MODALITIES- PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT • Aim (Table 8. 3) – Diagnose underlying conditions requiring additional treatment • • • KUB plus a urinary tract ultrasound scan : sufficient first-line investigation Intravenous urography (IVU) or computed tomography (CT) imaging : most appropriate second-line investigations. – CT scans • • Poor renal function or contrast allergies Evidence of urinary tract obstruction Antegrade imaging via nephrostomy or retrograde urography – • Superior to renal ultrasonography and IVU Unenhanced + contrast-enhanced CT: excellent imaging modalities. Advantages in distinguishing degree and type of involvement of the renal parenchyma More accurate diagnosis of acute abscesses Rapid identification of obstructing pathology such as urolithiasis. Magnetic resonance urography, nuclear medicine renography and retrograde urography – – • Adequate urinary drainage Avoid deterioration in renal function and clinical status Prevent recurrence of infection Uncommon in the acute setting In adult female patients diagnosed with an isolated episode of simple acute bacterial cystitis : imaging, not necessary. Indications for imaging study: – – Patient's history, such as hematuria and loin pain Patients with acute pyelonephritis • – Urinary tract ultrasound (in combination with a KUB radiograph) during management - as a screening modality - exclude any complicating pathology. UTIs in men • • Ultrasound scans and plain abdominal radiographs Other investigations – – – Uroflowmetry Residual volume estimation Flexible cystourethroscopy

Table 8. 3 Imaging modalities used in the investigation of urinary tract infections

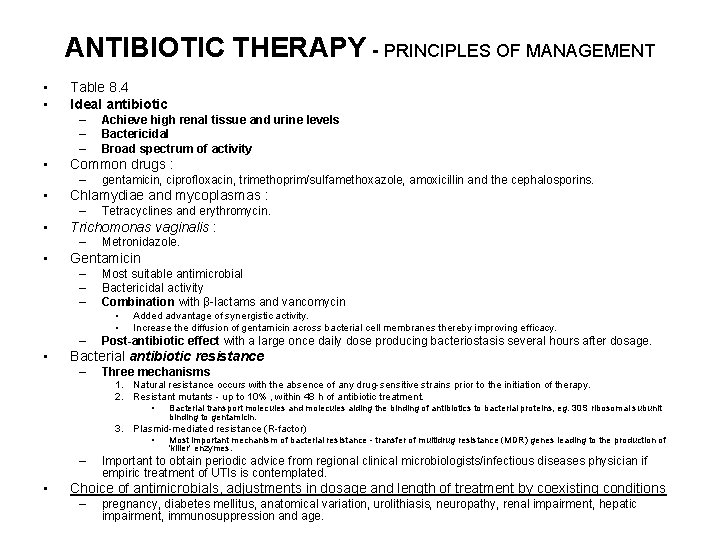

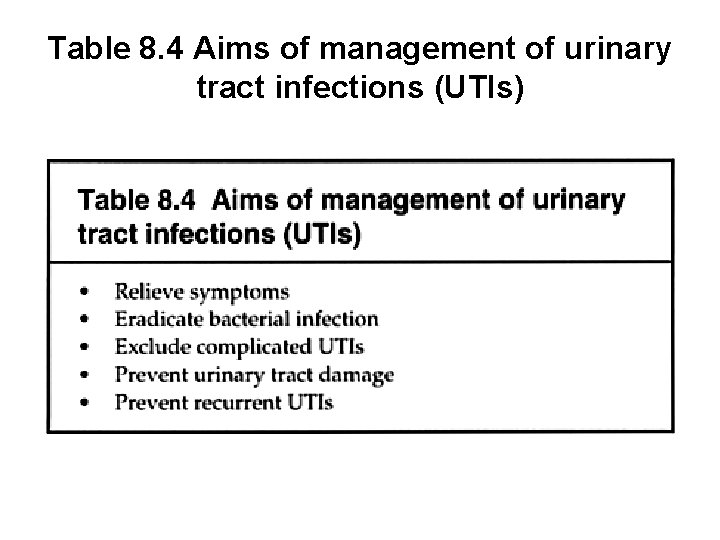

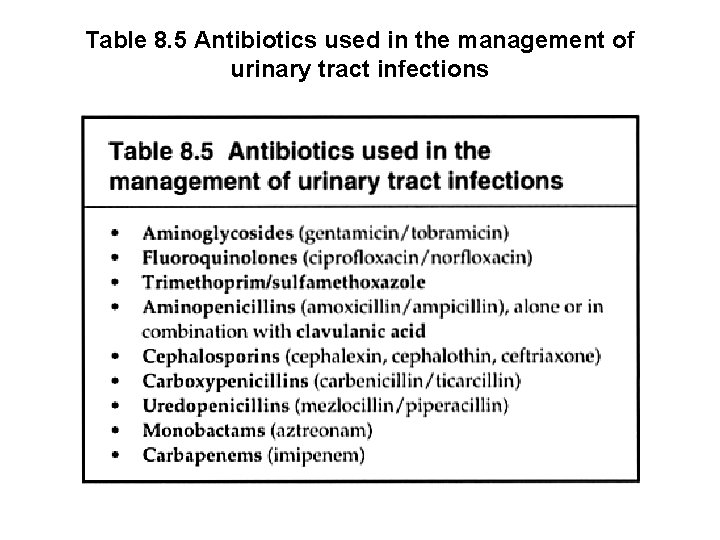

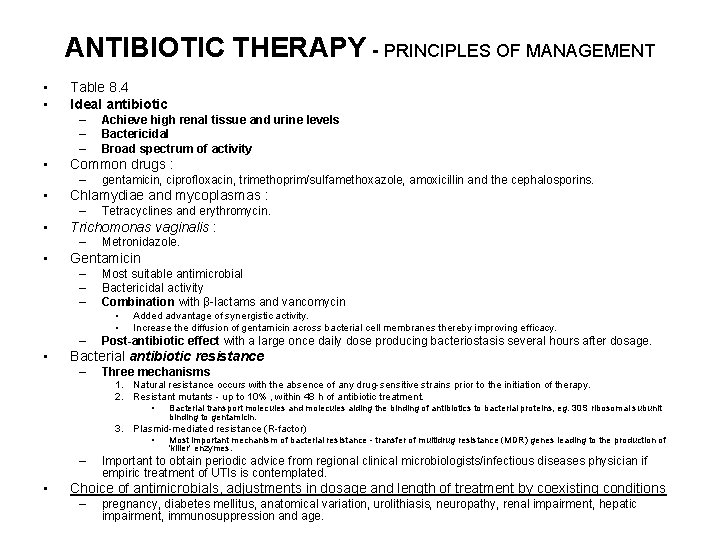

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT • • Table 8. 4 Ideal antibiotic – – – • Common drugs : – • Tetracyclines and erythromycin. Trichomonas vaginalis : – • gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin and the cephalosporins. Chlamydiae and mycoplasmas : – • Achieve high renal tissue and urine levels Bactericidal Broad spectrum of activity Metronidazole. Gentamicin – – – Most suitable antimicrobial Bactericidal activity Combination with β-lactams and vancomycin • • – • Added advantage of synergistic activity. Increase the diffusion of gentamicin across bacterial cell membranes thereby improving efficacy. Post-antibiotic effect with a large once daily dose producing bacteriostasis several hours after dosage. Bacterial antibiotic resistance – Three mechanisms 1. Natural resistance occurs with the absence of any drug-sensitive strains prior to the initiation of therapy. 2. Resistant mutants - up to 10% , within 48 h of antibiotic treatment. • Bacterial transport molecules and molecules aiding the binding of antibiotics to bacterial proteins, eg. 30 S ribosomal subunit binding to gentamicin. 3. Plasmid-mediated resistance (R-factor) • – • Most important mechanism of bacterial resistance - transfer of multidrug resistance (MDR) genes leading to the production of 'killer' enzymes. Important to obtain periodic advice from regional clinical microbiologists/infectious diseases physician if empiric treatment of UTIs is contemplated. Choice of antimicrobials, adjustments in dosage and length of treatment by coexisting conditions – pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, anatomical variation, urolithiasis, neuropathy, renal impairment, hepatic impairment, immunosuppression and age.

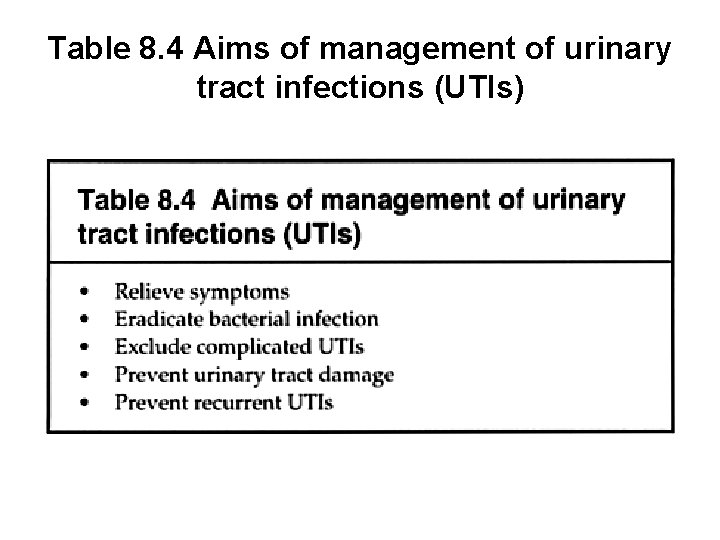

Table 8. 4 Aims of management of urinary tract infections (UTIs)

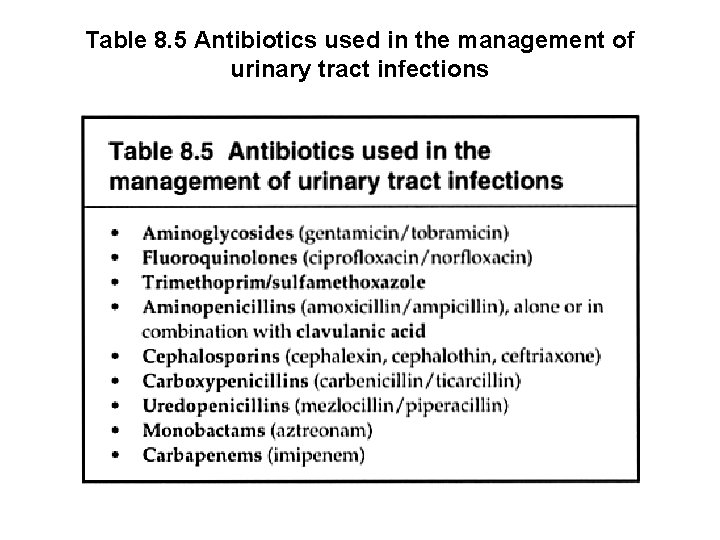

Table 8. 5 Antibiotics used in the management of urinary tract infections

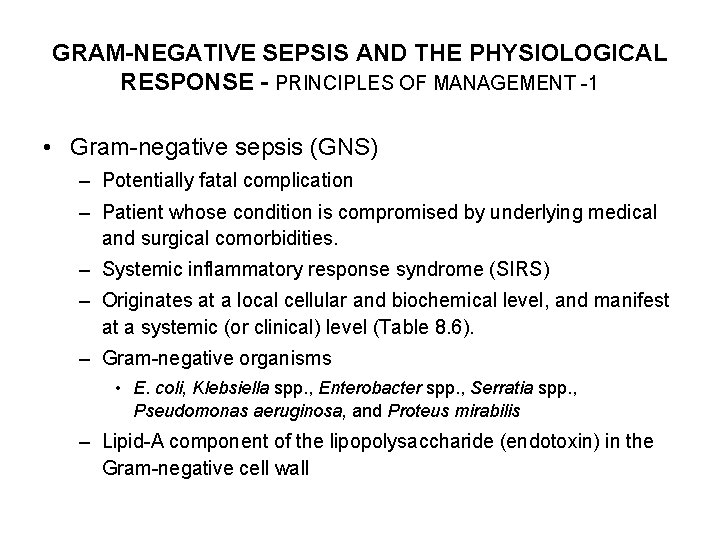

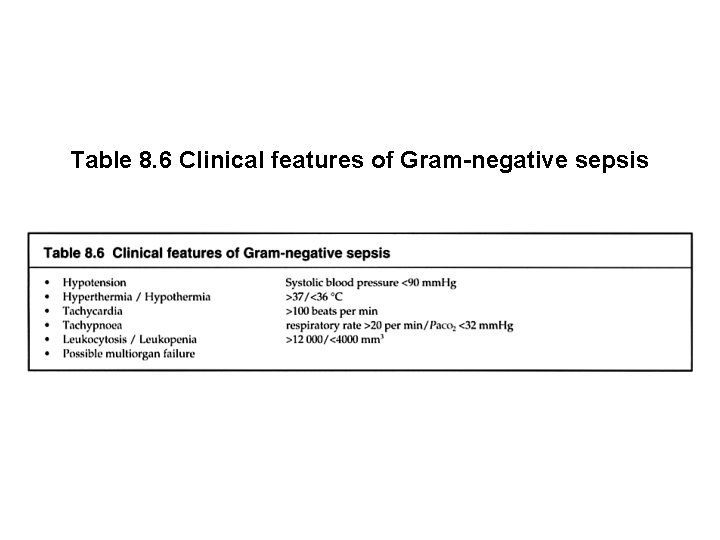

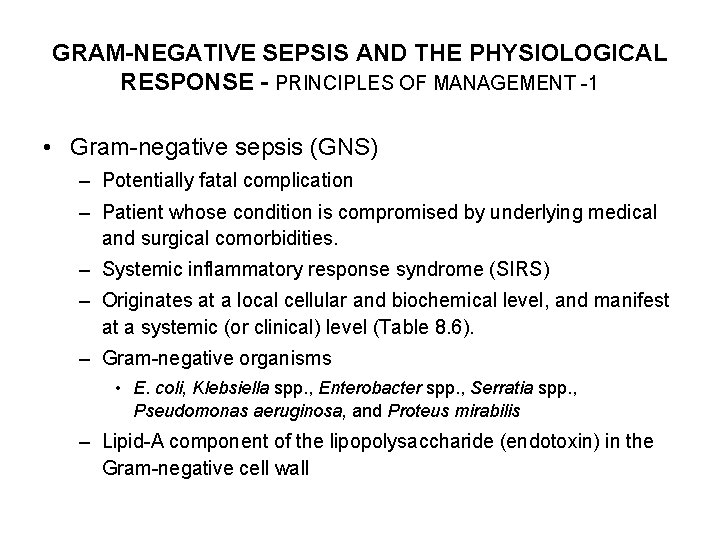

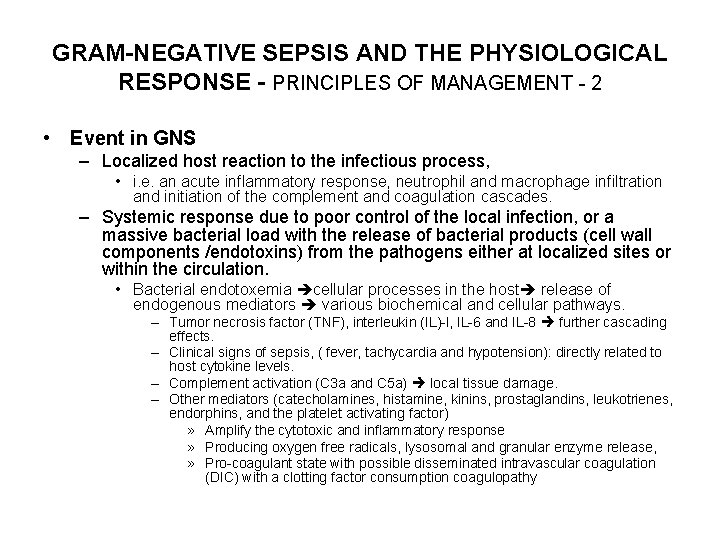

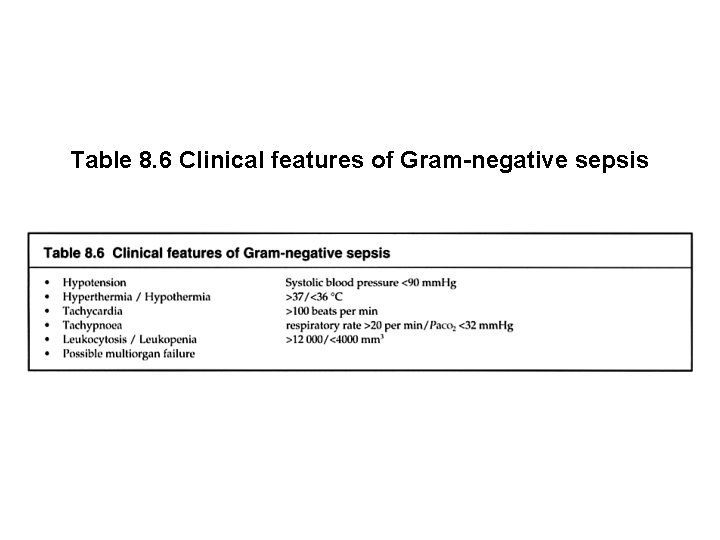

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT -1 • Gram-negative sepsis (GNS) – Potentially fatal complication – Patient whose condition is compromised by underlying medical and surgical comorbidities. – Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) – Originates at a local cellular and biochemical level, and manifest at a systemic (or clinical) level (Table 8. 6). – Gram-negative organisms • E. coli, Klebsiella spp. , Enterobacter spp. , Serratia spp. , Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis – Lipid-A component of the lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) in the Gram-negative cell wall

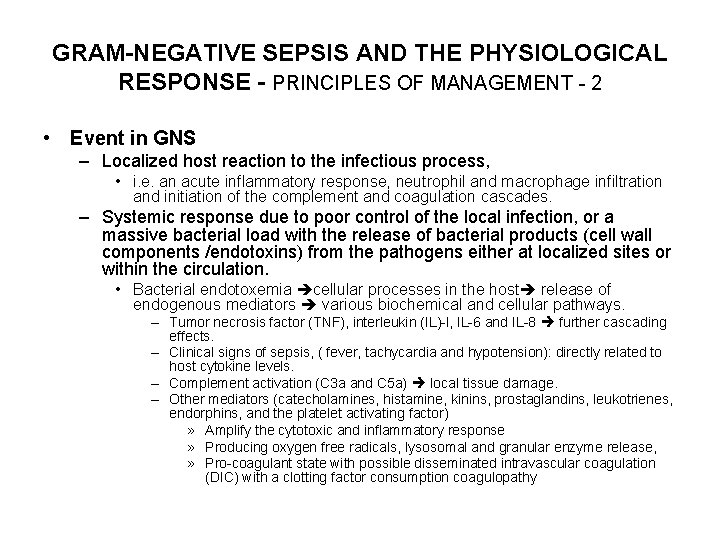

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT - 2 • Event in GNS – Localized host reaction to the infectious process, • i. e. an acute inflammatory response, neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and initiation of the complement and coagulation cascades. – Systemic response due to poor control of the local infection, or a massive bacterial load with the release of bacterial products (cell wall components /endotoxins) from the pathogens either at localized sites or within the circulation. • Bacterial endotoxemia cellular processes in the host release of endogenous mediators various biochemical and cellular pathways. – Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-l, IL-6 and IL-8 further cascading effects. – Clinical signs of sepsis, ( fever, tachycardia and hypotension): directly related to host cytokine levels. – Complement activation (C 3 a and C 5 a) local tissue damage. – Other mediators (catecholamines, histamine, kinins, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, endorphins, and the platelet activating factor) » Amplify the cytotoxic and inflammatory response » Producing oxygen free radicals, lysosomal and granular enzyme release, » Pro-coagulant state with possible disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with a clotting factor consumption coagulopathy

Table 8. 6 Clinical features of Gram-negative sepsis

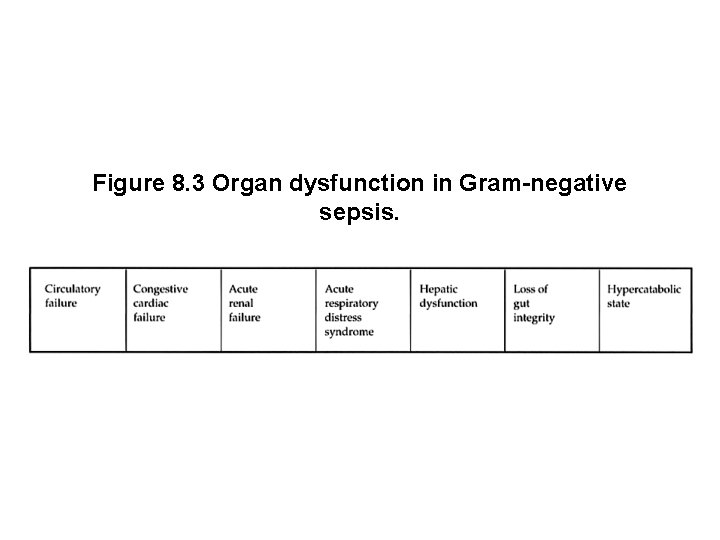

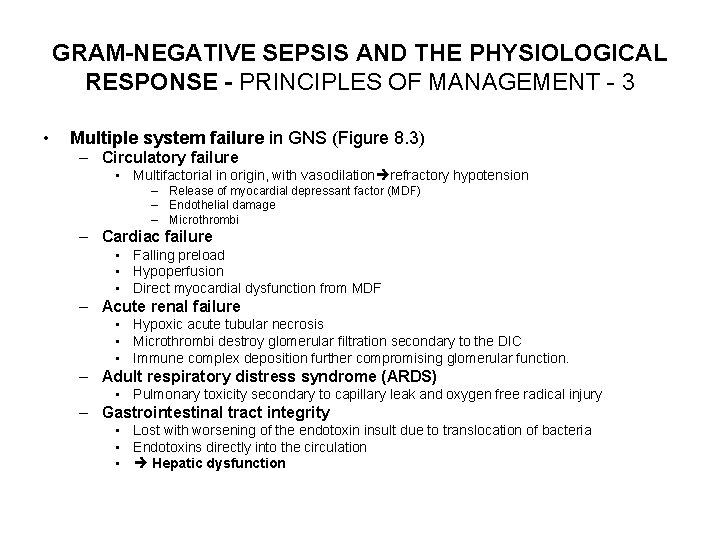

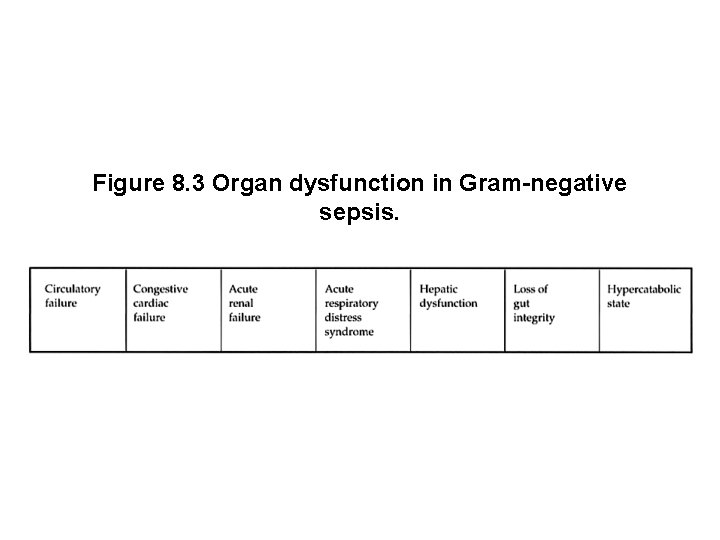

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT - 3 • Multiple system failure in GNS (Figure 8. 3) – Circulatory failure • Multifactorial in origin, with vasodilation refractory hypotension – Release of myocardial depressant factor (MDF) – Endothelial damage – Microthrombi – Cardiac failure • Falling preload • Hypoperfusion • Direct myocardial dysfunction from MDF – Acute renal failure • Hypoxic acute tubular necrosis • Microthrombi destroy glomerular filtration secondary to the DIC • Immune complex deposition further compromising glomerular function. – Adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) • Pulmonary toxicity secondary to capillary leak and oxygen free radical injury – Gastrointestinal tract integrity • Lost with worsening of the endotoxin insult due to translocation of bacteria • Endotoxins directly into the circulation • Hepatic dysfunction

Figure 8. 3 Organ dysfunction in Gram-negative sepsis.

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT - 4 • Hypercatabolic state due to hypermetabolism – Difficult to overcome despite aggressive nutritional support. – Ongoing endothelial cell damage produces worsening DIC – Blood pressure and urine output fall – Tachycardia – Lactate rises

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT - 5 • Management of GNS – Physiological support • • • Fluid resuscitation Oxygen therapy Ventilatory support Dialysis Vasoactive drugs Metabolic and nutritional therapy – Antibiotic therapy • Initially broad spectrum with a β-lactam and aminoglycoside, or third -generation cephalosporin until positive blood or urine cultures – Removal of the source of sepsis • Emergent basis as necessary • Drainage of an obstructed renal unit • Debridement of an infective focus

GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS AND THE PHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE - PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT - 6 • Mortality from GNS – High in severe cases – Factors for reducing motality: • Early diagnosis • Aggressive therapy • Appropriate intensive care unit (ICU) referral – Other measures : • • • Antiendotoxin antibodies Anticytokine antibodies Monoclonal antibodies targeting leukocyte receptors Nitric oxide synthase inhibition Steroid therapy – To date, despite promising results in animal models of sepsis, no dramatic clinical benefit in human disease has been shown.

Knight-taylor brace indications

Knight-taylor brace indications Tujuan akuntansi adalah

Tujuan akuntansi adalah Ref 2021 twitter

Ref 2021 twitter Post ref accounting example

Post ref accounting example Mekanisme debit kredit

Mekanisme debit kredit Twitter ref 2021

Twitter ref 2021 Hockey unsportsmanlike conduct signal

Hockey unsportsmanlike conduct signal Ref criteria

Ref criteria Linesman positioning hockey

Linesman positioning hockey Ice hockey signals

Ice hockey signals Ref et idaho

Ref et idaho Katholische kirche rothrist

Katholische kirche rothrist Packages_display.php?ref=

Packages_display.php?ref= Unnecessary delay in volleyball

Unnecessary delay in volleyball Ref divider

Ref divider Bakla typings

Bakla typings Ref 2026

Ref 2026 X ref

X ref Ref impact case studies

Ref impact case studies Ref

Ref Ergun equation derivation

Ergun equation derivation Ref jur

Ref jur Ref-qualified member functions

Ref-qualified member functions Felvi középiskolai bizonyítvány feltöltése

Felvi középiskolai bizonyítvány feltöltése Post. ref. accounting

Post. ref. accounting I should take a local orientation dive whenever i

I should take a local orientation dive whenever i Chapter 16 respiratory emergencies

Chapter 16 respiratory emergencies Major nutritional deficiency diseases in emergencies

Major nutritional deficiency diseases in emergencies Lesson 6: cardiac emergencies and using an aed

Lesson 6: cardiac emergencies and using an aed Environmental emergencies emt

Environmental emergencies emt