Tutorial Workshop DDSA Discrete Dynamical Systems and Applications

- Slides: 22

Tutorial Workshop DDSA Discrete Dynamical Systems and Applications Urbino June 30 – July 3, 2010 CREDIT MARKET IMPERFECTIONS AND DETERMINACY Anna Agliari Catholic University – Piacenza e-mail: anna. agliari@unicatt. it

MOTIVATION • Financial factors may play a central role in the emergence of development/poverty traps (Azariadis & Drazen (1997), Aghion & Bolton (1997), Matsuyama (2007), Glavan (2008)) • Failure of coordination among agents’ expectations too may be a reason behind underdevelopment trap (Woodford (1986), Grandmont (1998) Cazzavillan et al. (1998), Barinci & Cheron (2001)) • We modify an OLG growth model with credit market imperfections proposed by Matsuyama (2004) including agents’ endogeneous labor supply decision • We show that multiple equilibria may exist, due to self-fulfilling expectations

OUTLINE • Introduction of the model • Digression on determinacy and indeterminacy • Local and global analysis of the model • Global indeterminacy obtained via heteroclinic and homoclinic connections

THE OLG MODEL • The time is discrete and extends from zero to infinity • In each period t, there are two generations alive, young and old agents • Each generation consists of a continuum of homogeneous agents with unit mass • Young agents are endowed with one unit of labor, do not consume and save their entire wage income • Old agents allocate their wealth in order to finance their consumption

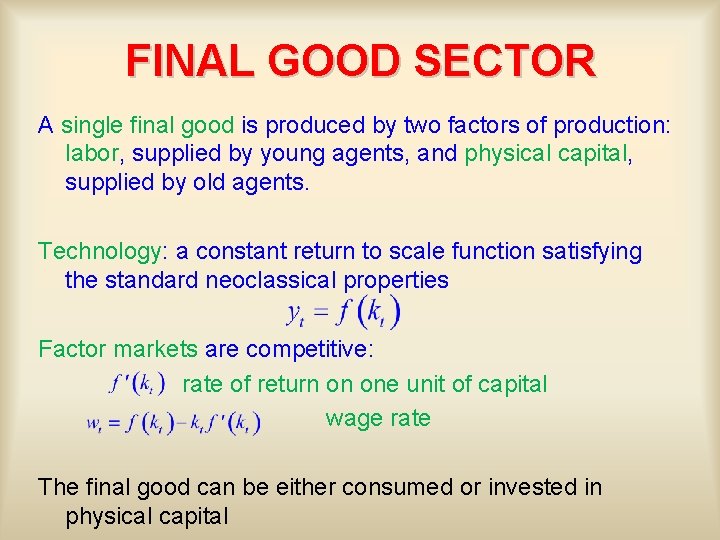

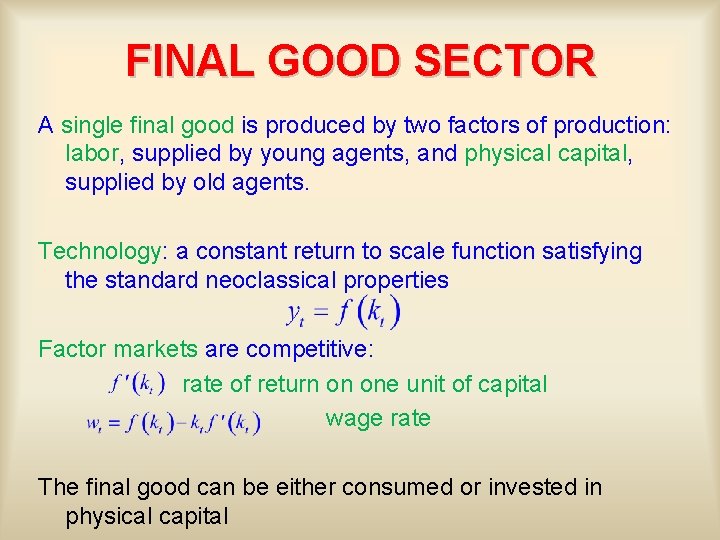

FINAL GOOD SECTOR A single final good is produced by two factors of production: labor, supplied by young agents, and physical capital, supplied by old agents. Technology: a constant return to scale function satisfying the standard neoclassical properties Factor markets are competitive: rate of return on one unit of capital wage rate The final good can be either consumed or invested in physical capital

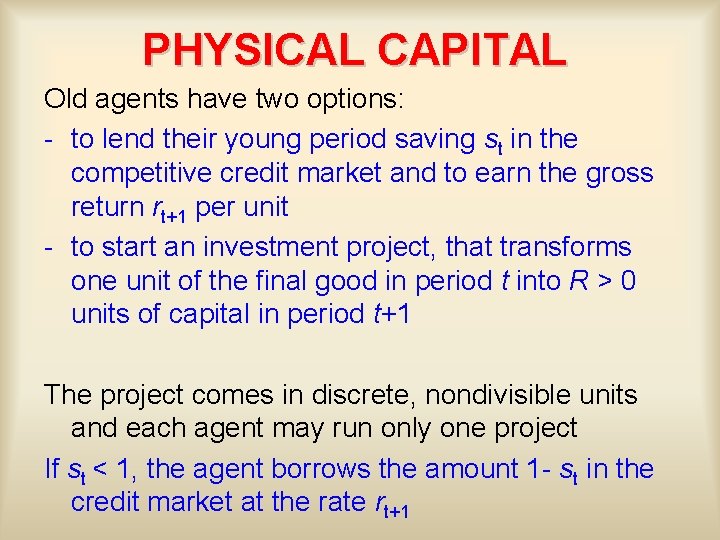

PHYSICAL CAPITAL Old agents have two options: - to lend their young period saving st in the competitive credit market and to earn the gross return rt+1 per unit - to start an investment project, that transforms one unit of the final good in period t into R > 0 units of capital in period t+1 The project comes in discrete, nondivisible units and each agent may run only one project If st < 1, the agent borrows the amount 1 - st in the credit market at the rate rt+1

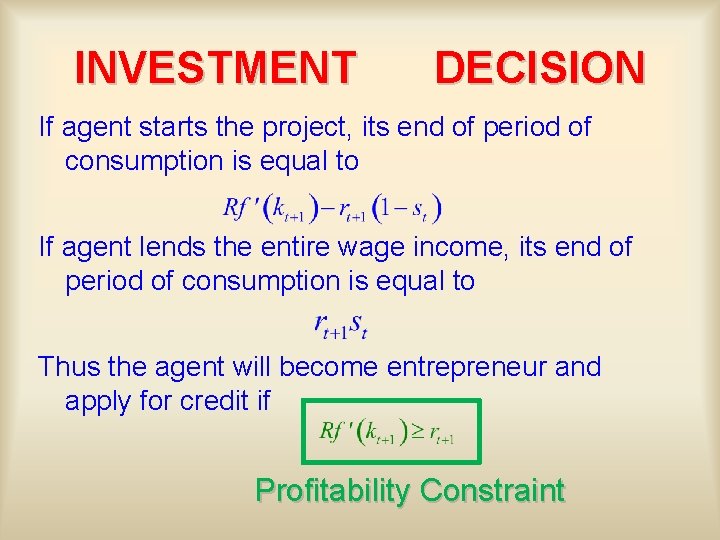

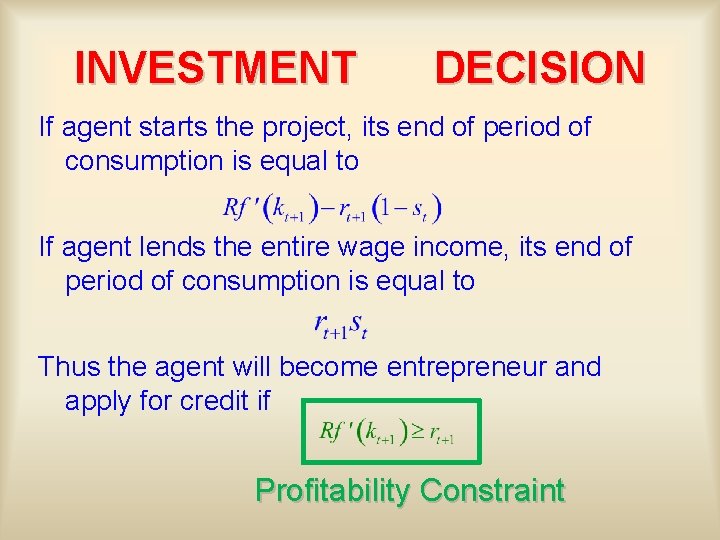

INVESTMENT DECISION If agent starts the project, its end of period of consumption is equal to If agent lends the entire wage income, its end of period of consumption is equal to Thus the agent will become entrepreneur and apply for credit if Profitability Constraint

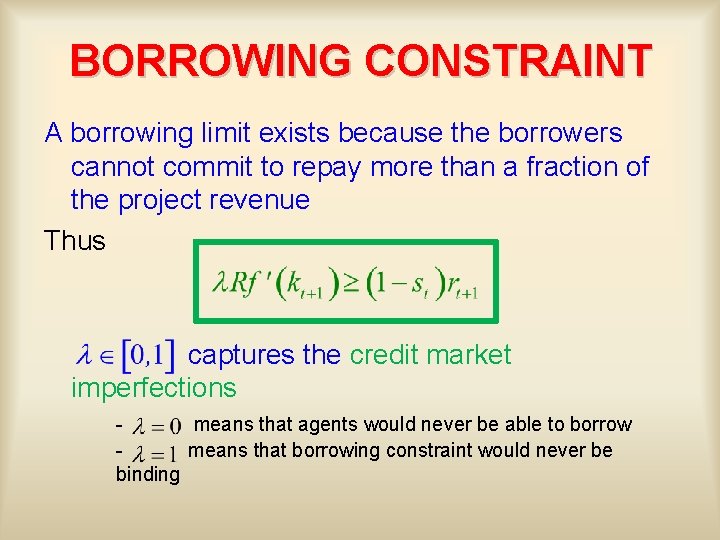

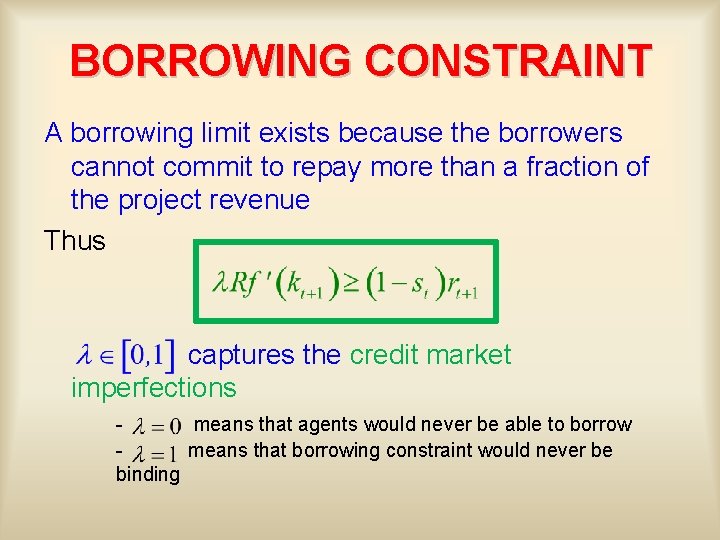

BORROWING CONSTRAINT A borrowing limit exists because the borrowers cannot commit to repay more than a fraction of the project revenue Thus captures the credit market imperfections means that agents would never be able to borrow means that borrowing constraint would never be binding

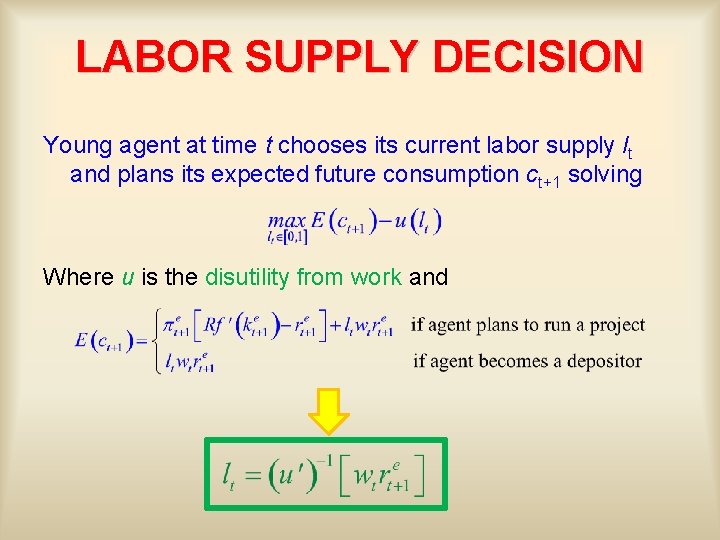

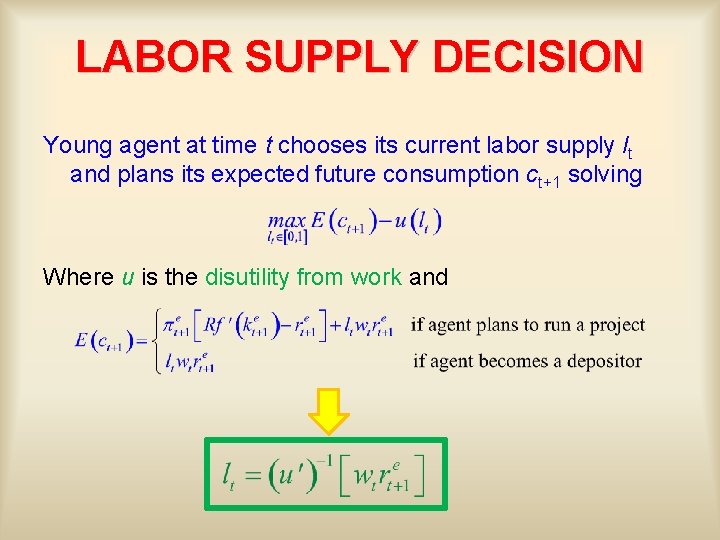

LABOR SUPPLY DECISION Young agent at time t chooses its current labor supply lt and plans its expected future consumption ct+1 solving Where u is the disutility from work and

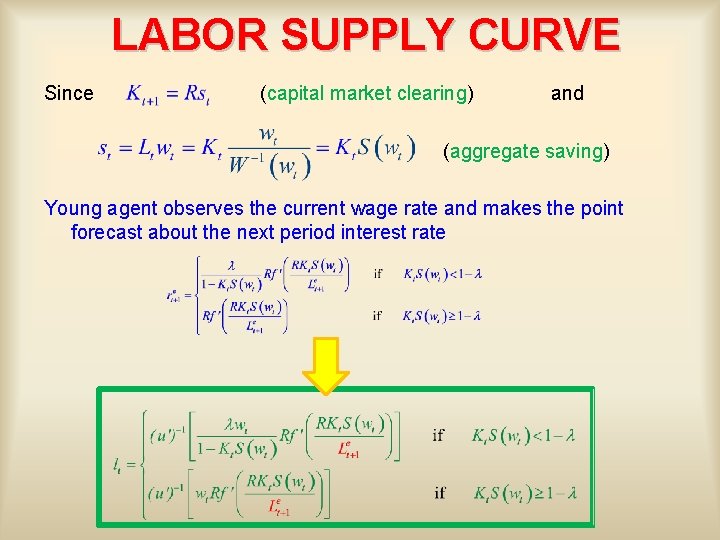

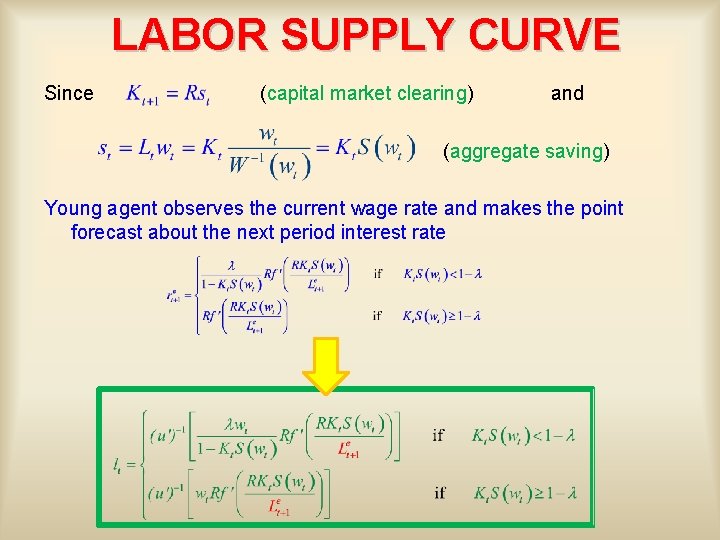

LABOR SUPPLY CURVE Since (capital market clearing) and (aggregate saving) Young agent observes the current wage rate and makes the point forecast about the next period interest rate

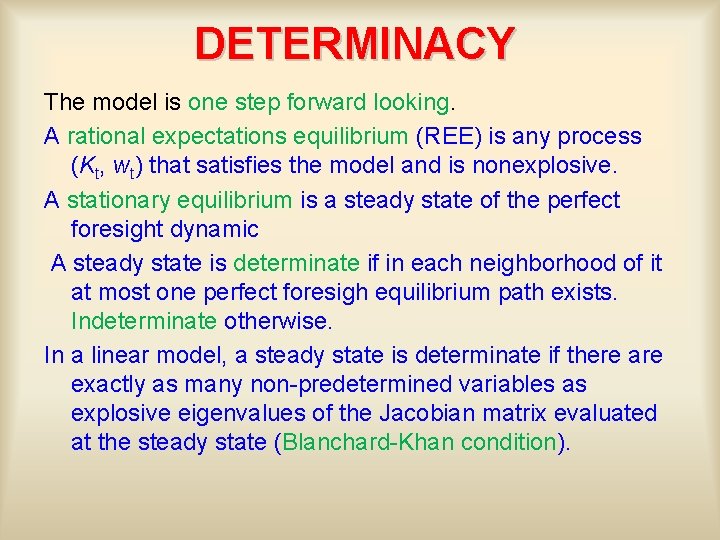

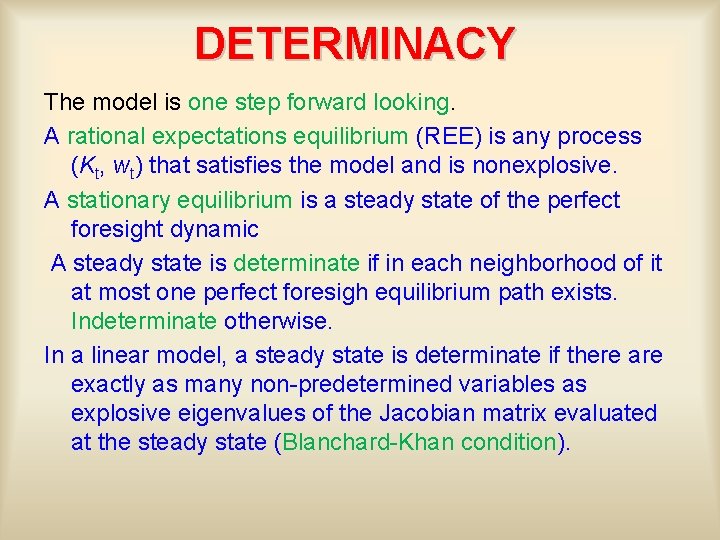

DETERMINACY The model is one step forward looking. A rational expectations equilibrium (REE) is any process (Kt, wt) that satisfies the model and is nonexplosive. A stationary equilibrium is a steady state of the perfect foresight dynamic A steady state is determinate if in each neighborhood of it at most one perfect foresigh equilibrium path exists. Indeterminate otherwise. In a linear model, a steady state is determinate if there are exactly as many non-predetermined variables as explosive eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix evaluated at the steady state (Blanchard-Khan condition).

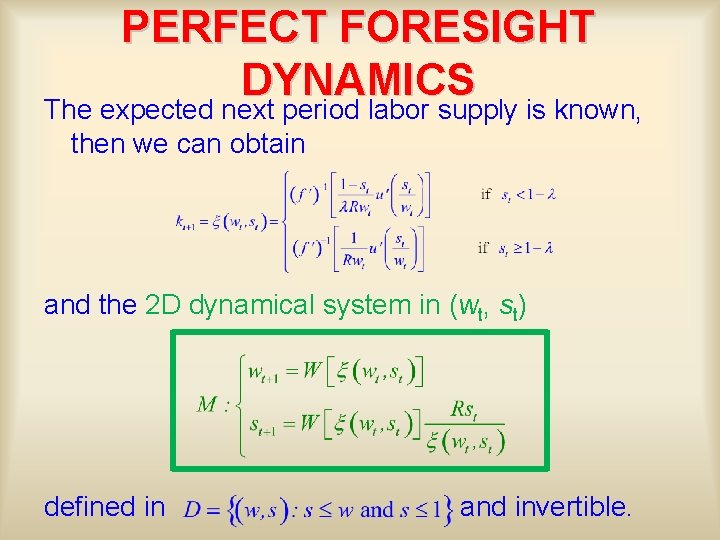

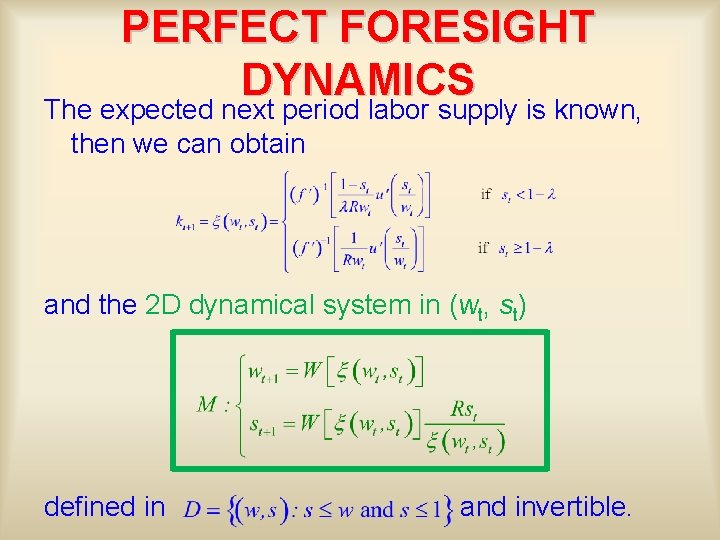

PERFECT FORESIGHT DYNAMICS The expected next period labor supply is known, then we can obtain and the 2 D dynamical system in (wt, st) defined in and invertible.

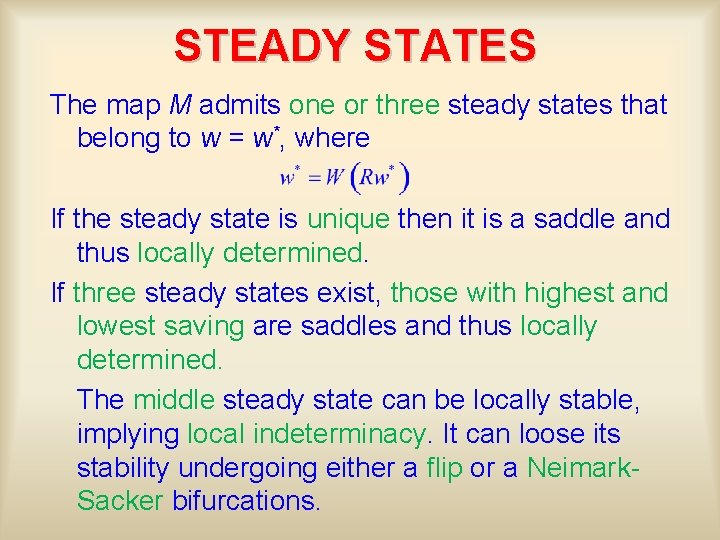

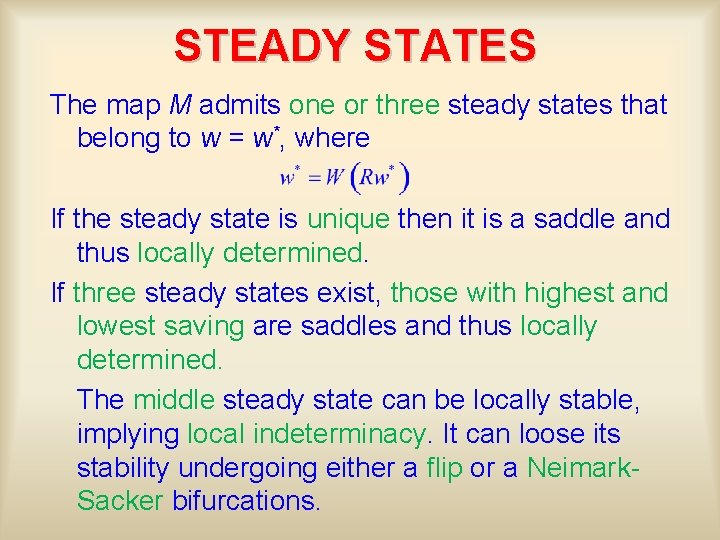

STEADY STATES The map M admits one or three steady states that belong to w = w*, where If the steady state is unique then it is a saddle and thus locally determined. If three steady states exist, those with highest and lowest saving are saddles and thus locally determined. The middle steady state can be locally stable, implying local indeterminacy. It can loose its stability undergoing either a flip or a Neimark. Sacker bifurcations.

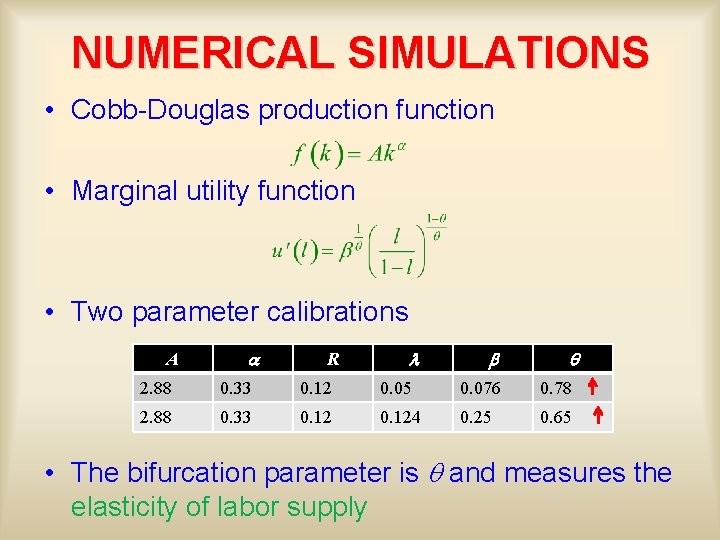

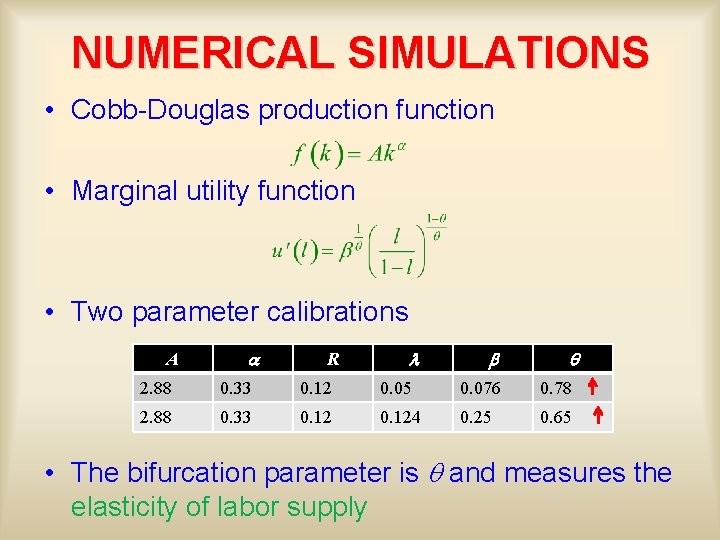

NUMERICAL SIMULATIONS • Cobb-Douglas production function • Marginal utility function • Two parameter calibrations A a R l b q 2. 88 0. 33 0. 12 0. 05 0. 076 0. 78 2. 88 0. 33 0. 124 0. 25 0. 65 • The bifurcation parameter is q and measures the elasticity of labor supply

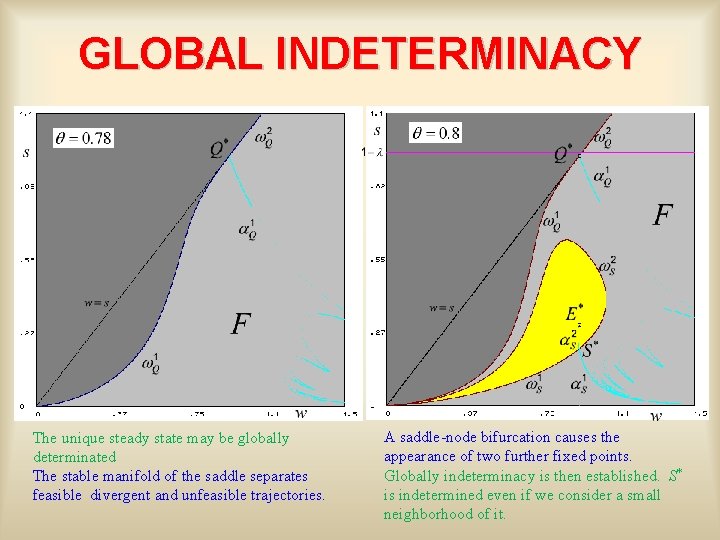

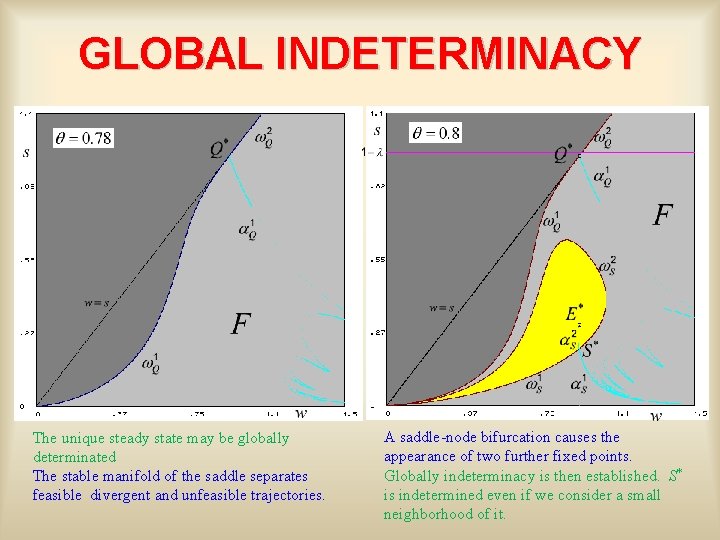

GLOBAL INDETERMINACY The unique steady state may be globally determinated The stable manifold of the saddle separates feasible divergent and unfeasible trajectories. A saddle-node bifurcation causes the appearance of two further fixed points. Globally indeterminacy is then established. S* is indetermined even if we consider a small neighborhood of it.

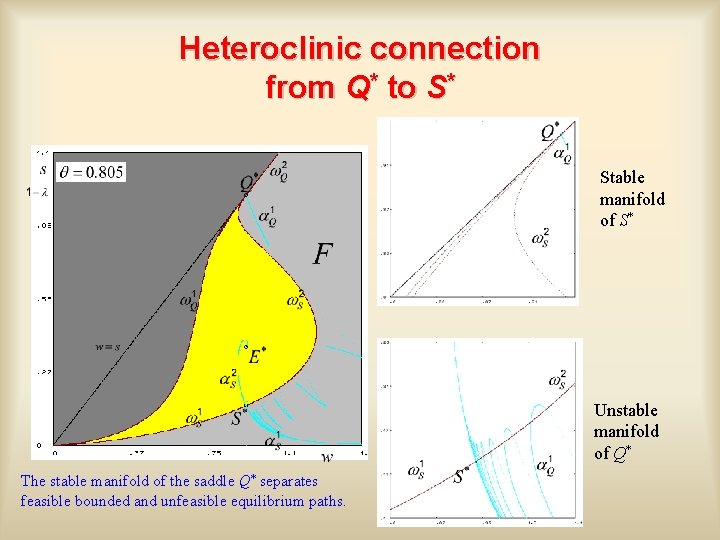

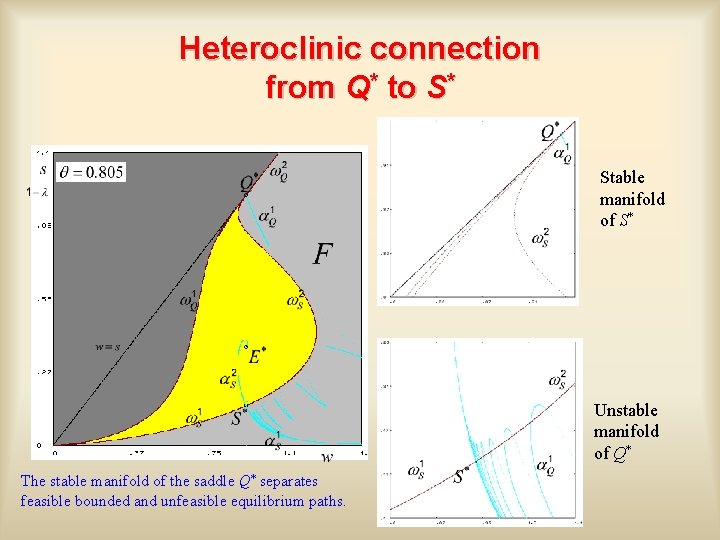

Heteroclinic connection from Q* to S* Stable manifold of S* Unstable manifold of Q* The stable manifold of the saddle Q* separates feasible bounded and unfeasible equilibrium paths.

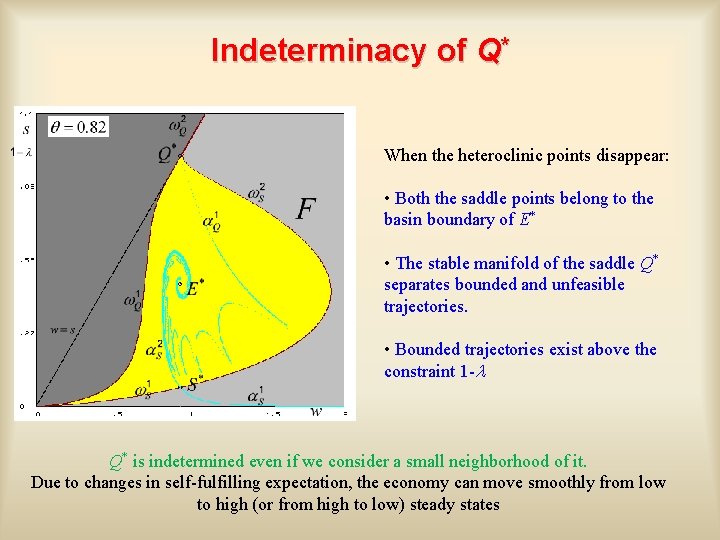

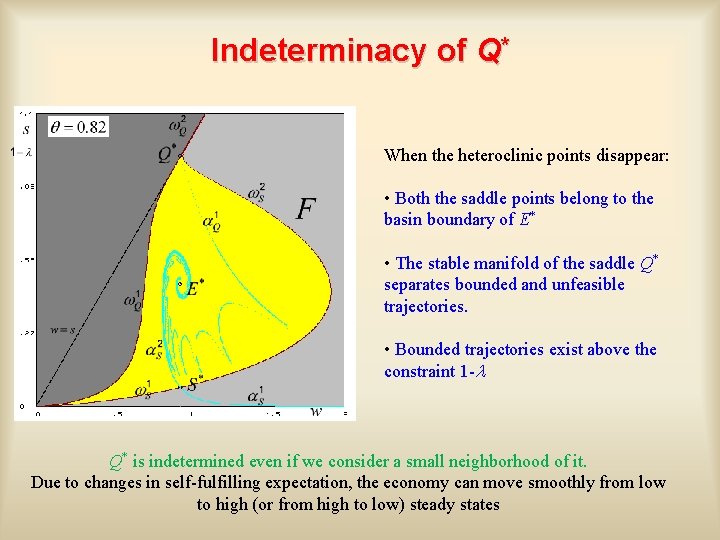

Indeterminacy of Q* When the heteroclinic points disappear: • Both the saddle points belong to the basin boundary of E* • The stable manifold of the saddle Q* separates bounded and unfeasible trajectories. • Bounded trajectories exist above the constraint 1 -l Q* is indetermined even if we consider a small neighborhood of it. Due to changes in self-fulfilling expectation, the economy can move smoothly from low to high (or from high to low) steady states

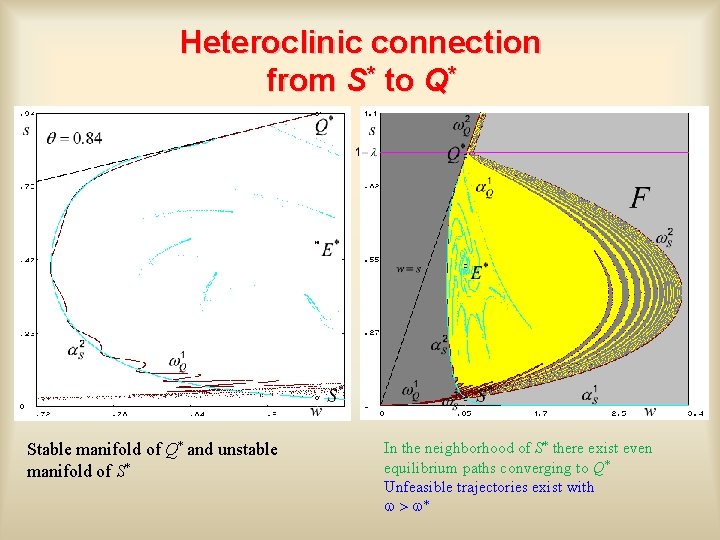

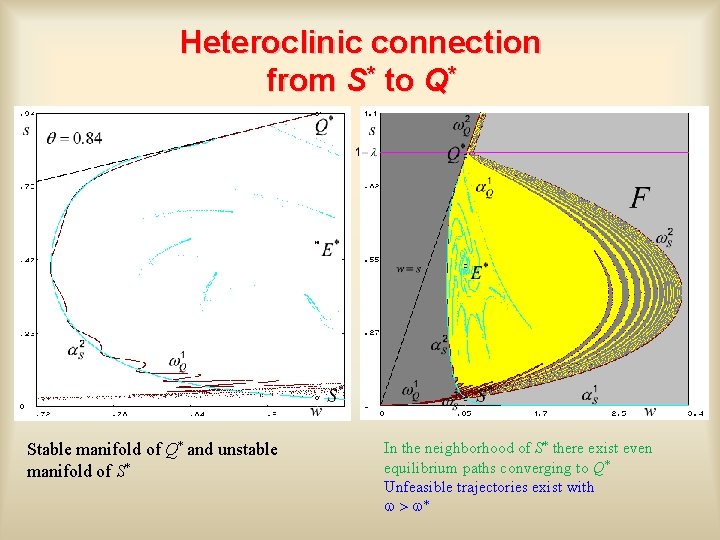

Heteroclinic connection from S* to Q* Stable manifold of Q* and unstable manifold of S* In the neighborhood of S* there exist even equilibrium paths converging to Q* Unfeasible trajectories exist with w > w*

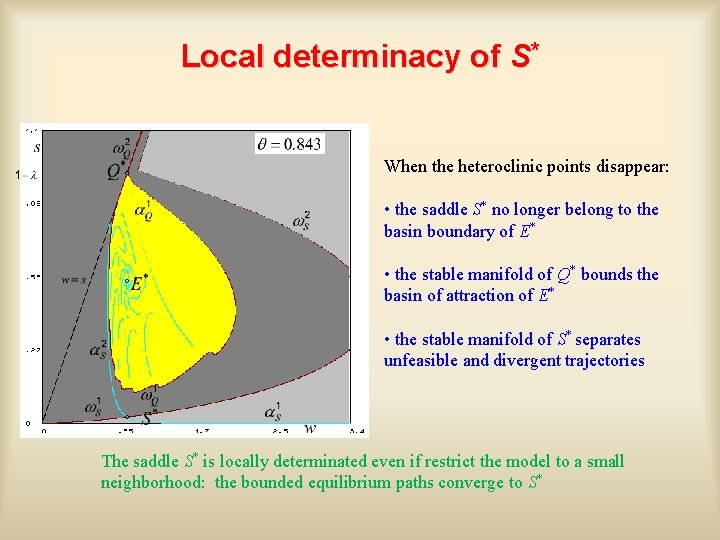

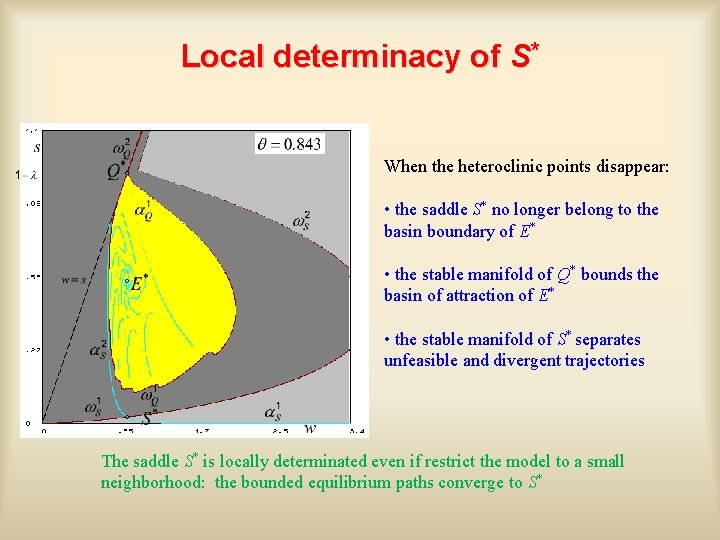

Local determinacy of S* When the heteroclinic points disappear: • the saddle S* no longer belong to the basin boundary of E* • the stable manifold of Q* bounds the basin of attraction of E* • the stable manifold of S* separates unfeasible and divergent trajectories The saddle S* is locally determinated even if restrict the model to a small neighborhood: the bounded equilibrium paths converge to S*

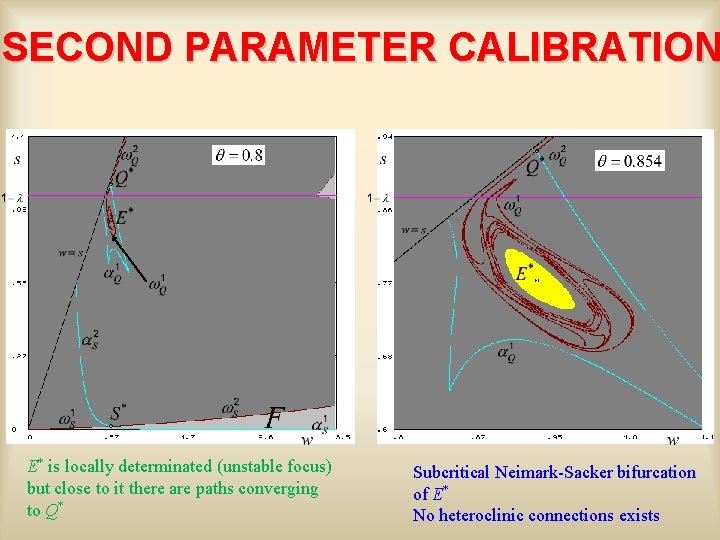

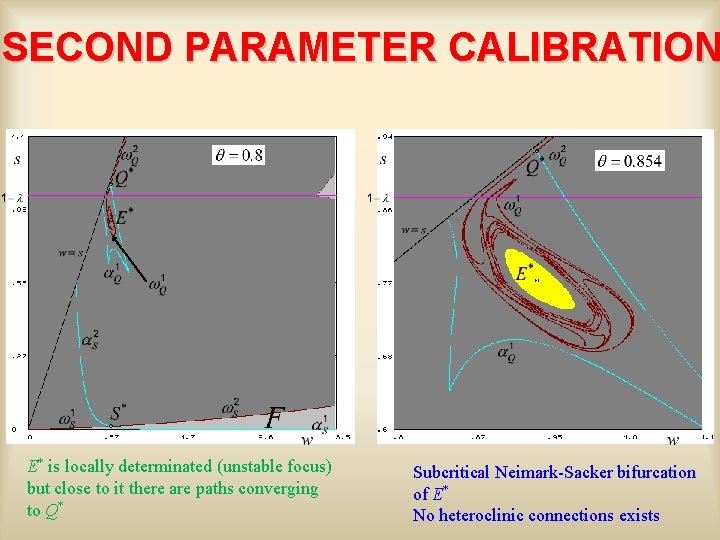

SECOND PARAMETER CALIBRATION E* is locally determinated (unstable focus) but close to it there are paths converging to Q* Subcritical Neimark-Sacker bifurcation of E* No heteroclinic connections exists

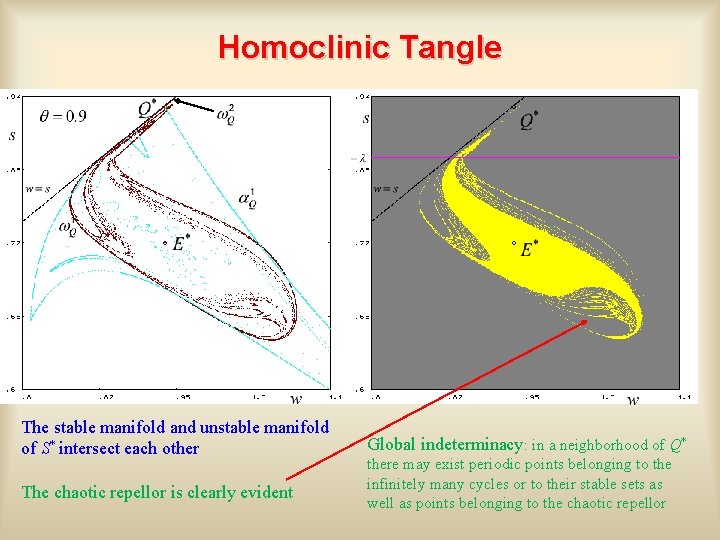

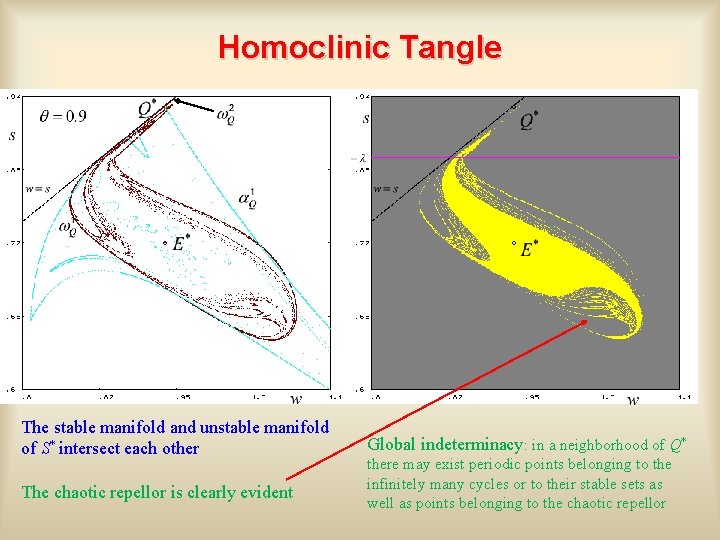

Homoclinic Tangle The stable manifold and unstable manifold of S* intersect each other The chaotic repellor is clearly evident Global indeterminacy: in a neighborhood of Q* there may exist periodic points belonging to the infinitely many cycles or to their stable sets as well as points belonging to the chaotic repellor

REFERENCES Working paper available at http: //econpapers. repec. org/paper/ctcserie 2/dises 1059. htm • • • Matsuyama, K. (2004): Financial Market Globalization, Symmetry-Breaking and Endogenous Inequality of Nations", Econometrica, 72, 853 -84. Aghion, P. & Bolton, P. (1997): A Theory of Trickle-Down Growth and Development", Review of Economic Studies, 64, 151 -72. Azariadis, C. & Drazen, A. (1990): Threshold Externalities in Economic Development", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105, 501 -26. Barinci, J. -P. & Cheron, A. (2001): Sunspots and the Business Cycle in a Finance Constrained Economy", Journal of Economic Theory, 97, 30 -49. Cazzavillan, G. , Lloyd-Braga, T. & Pintus, P. A. (1998): Multiple Steady States and Endogenous Fluctuations with Increasing Returns to Scale in Production", Journal of Economic Theory, 80, 60 -107. Glavan, B. (2008): Coordination Economics, Poverty Traps, and the Market Process: A New Case for Industrial Policy? , Independent Review, 13, 225 -43. Grandmont, J. -M. (1998): Introduction to Market Psychology and Nonlinear Endogenous Business Cycles", Journal of Economic Theory, 80, 1 -13. Matsuyama, K. (2007): Credit Traps and Credit Cycles", American Economic Review, 97, 503 -516. Woodford, Michael; (1986): Stationary Sunspot Equilibria in a Finance Constrained Economy", Journal of Economic Theory, 40, 128 -37.