The Predictive Validity of Ideal Partner Preferences in

- Slides: 27

The Predictive Validity of Ideal Partner Preferences in Relationship Formation Lorne Campbell The University of Western Ontario In collaboration with Sarah C. E. Stanton

Research on Partner Preferences • Vast—over 48 k Google Scholar hits to various keywords associated with interpersonal attraction • Largely self-report – Provide people a list of qualities to rate on importance – Ask people to list qualities they are looking for in a partner

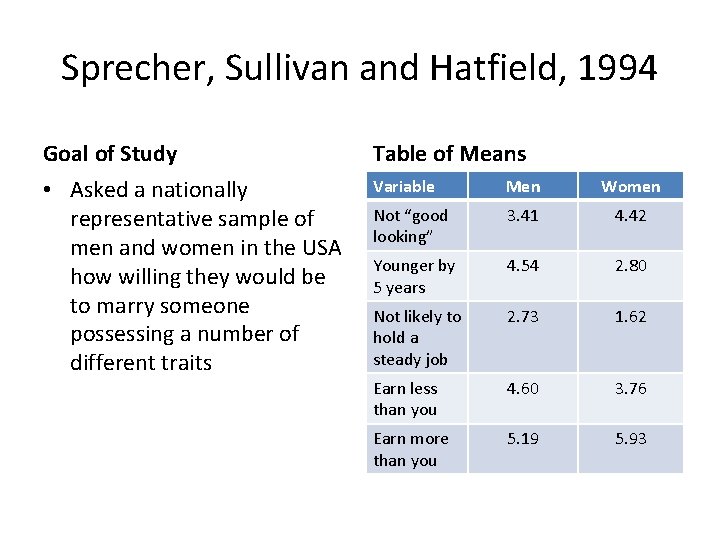

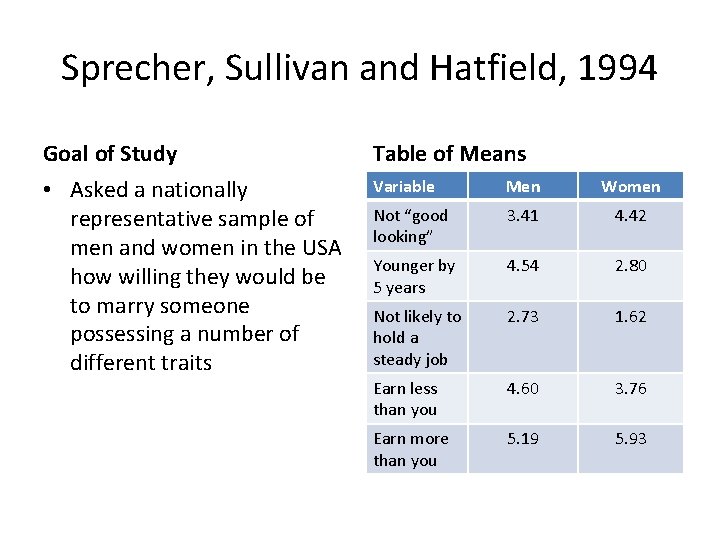

Sprecher, Sullivan and Hatfield, 1994 Goal of Study Table of Means • Asked a nationally representative sample of men and women in the USA how willing they would be to marry someone possessing a number of different traits Variable Men Women Not “good looking” 3. 41 4. 42 Younger by 5 years 4. 54 2. 80 Not likely to hold a steady job 2. 73 1. 62 Earn less than you 4. 60 3. 76 Earn more than you 5. 19 5. 93

Important Assumption • What people say they want in a future partner should be associated with the actual characteristics of their future partners – i. e. , partner preferences somehow implicated in actual mate search/mate choice

Research Support: “Yes” • Buriss et al (2011) – When women prefer more masculine men as partners, they are with more masculine-looking men • Kenrick & Keefe (1992) – Age preferences for long-term partners – Age of actual marriages in diverse samples

Research Support: “Yes” • Elder (1969); Taylor & Glenn (1976) – More physically attractive women marry men with higher occupational status • Perusse (1993; 1994) – Large samples of men and women report on recent sexual behavior • Men: social status linked to sexual opportunities • Women: age linked to sexual opportunities

Research Support: “No” • Eastwick & Finkel (2008) – Speed-dating study: 4 -minute “dates” – Provide preferences before “dates”; rate appeal of each “date”; answer questions 10 different times over a 30 day period following event – Match between self-evaluations of “dates” and one’s own stated preferences did not predict romantic attraction – Conclusion: people lack introspective awareness of what influence their mate choices

Research Support: “No” • Eastwick et al. (2011) – Match between preferences and profile of opposite-sex other predicted attraction – After interaction with this person (confederate), that association went away – Conclusion: properties of the interactions are particularly important for attraction

Footnote • But see Li et al. , (2013) and Fletcher, Kerr, Li, & Valentine, (2014) for data suggesting that individuals’ preferences do predict actual choices using similar “get acquainted” paradigms

Meta-Analysis • Eastwick et al. (2014) • Conclusions: – (1) individuals are more satisfied with current romantic partners who more closely match their ideal preferences – (2) single individuals are more attracted to hypothetical partners who more closely match their preferences

Meta-Analysis • Eastwick et al. (2014) • Conclusions: – (3) preferences of single individuals, however, do not appear to predict how attracted those individuals were to actual potential partners following live interactions with them • “…just because participants claim to value particular qualities in a mate does not mean that they will preferentially pursue partners who possess such qualities” (p. 647).

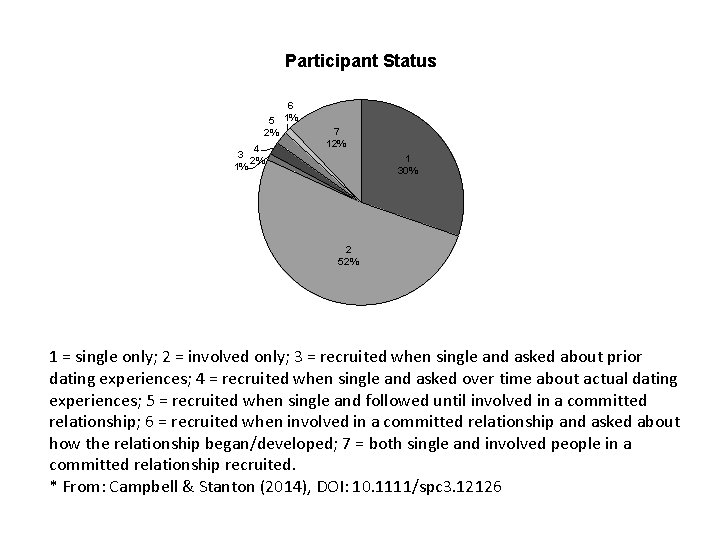

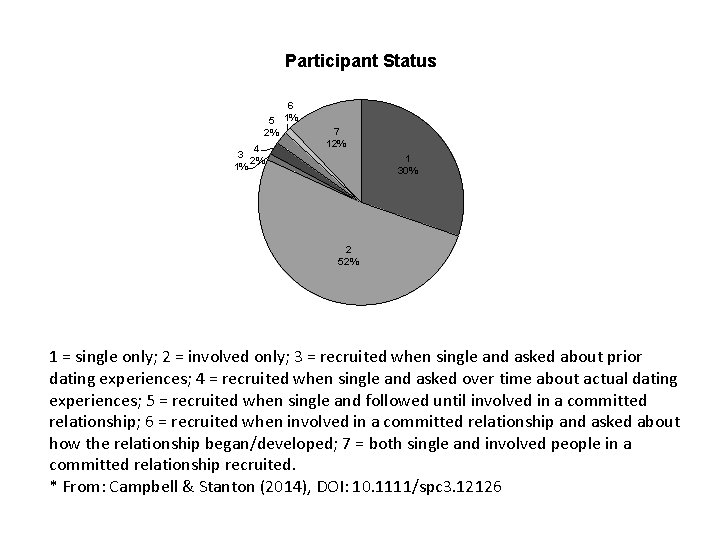

Participant Status 6 5 1% 2% 4 3 2% 1% 7 12% 1 30% 2 52% 1 = single only; 2 = involved only; 3 = recruited when single and asked about prior dating experiences; 4 = recruited when single and asked over time about actual dating experiences; 5 = recruited when single and followed until involved in a committed relationship; 6 = recruited when involved in a committed relationship and asked about how the relationship began/developed; 7 = both single and involved people in a committed relationship recruited. * From: Campbell & Stanton (2014), DOI: 10. 1111/spc 3. 12126

Research Focus 3 3% 1 37% 2 60% 1 = interpersonal attraction/liking 2 = later relationship processes 3 = formation/initiation of new relationships. * From: Campbell & Stanton (2014), DOI: 10. 1111/spc 3. 12126

Little Research Focuses on Relationship Formation • Three studies in the meta-analysis focused on relationship formation to some degree: – (1) Eastwick et al. (2008) – (2) Asendorpf et al. (2011) – the probabilities for various kinds of contact in their sample was “… 6. 6% for a developing romantic relationship 6 weeks after speed-dating, 5. 8% for sexual intercourse at any time in the year following speed-dating, and 4. 4% for reports of romantic relationships 1 year after speed-dating. ” – (3) Sprecher & Duck (1994) • Very few, if any, matched couples had a second date

Eastwick et al. (2014) • “If theoretical account of a particular finding contains the assumption (explicit or implicit) that the stated preference for a specific attribute translates into a revealed preference for that same attribute, theoretical account could be in need of revision. ” (Eastwick et al. , 2014, p. 648; italics added)

This Conclusion Gaining Traction • Gildersleeve et al. (2014), in meta-analysis on the ovulatory shift hypothesis: • “…given that several studies have found that stated preferences are only weakly predictive of real-life dating behavior (see, e. g. , Eastwick & Finkel, 2008; Eastwick, Luchies, Finkel, & Hunt, 2013; Todd, Penke, Fasolo, & Lenton, 2007), it remains an open question whether women have explicit knowledge of and can accurately report on the mate preferences that influence their real-life attractions” (p. 32) • Joel et al. (2014) – First line of abstract: “Mate preferences often fail to correspond with actual mate choices. ”

Too Early to Make Definitive Conclusions • No systematic empirical literature on predictive validity of ideal partner preferences in relationship formation • Cannot make conclusions in the absence of data • But, studying actual relationship formation is hard

Our First Empirical Effort • Assumption: preferences when single should be positively associated with the self-reported qualities of new romantic partners • Study design: obtain preferences from a lot of single people, follow them over time, try to recruit new partner when relationship forms • First original research I pre-registered: https: //osf. io/9 gf 4 q/

Participants • Started with 450 single people, excluded 24, left with 426 – Over 5 months, 167 entered new relationships • 85 provided us contact information of new partner – 45 accepted the invitation » 38 new partners completed the survey

Materials • Ideal partner preferences and self-perceptions were assessed across 38 qualities (e. g. , “understanding, ” “good lover, ” “ambitious, ”) used extensively in prior research • Murray et al’s 20 -item Interpersonal Qualities Scale (IQS) • Fletcher et al’s 18 -item Ideal Standards Scale (ISS) • All study materials etc can be found here: https: //osf. io/me 7 jp/

Primary Analyses • Multilevel Modeling – Preferences and self-evaluations nested within dyad • Allows for assessing within-dyad associations (averaged across dyads)

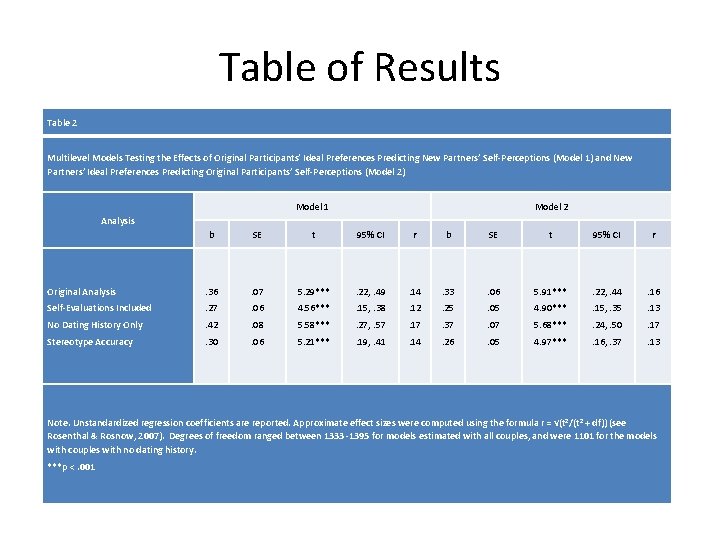

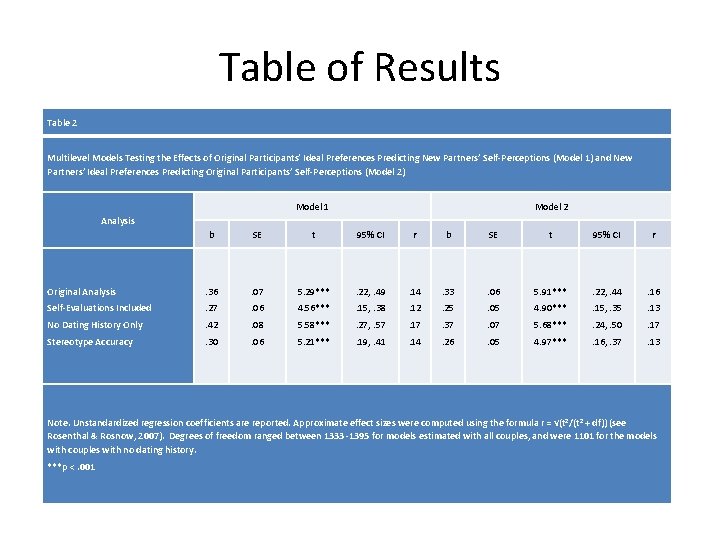

Models • Model 1: • DV = new partners’ self-evaluations across 38 traits • IV = original participants’ partner preferences assessed when single • Model 2: • DV = original participants’ self-evaluations across 38 traits assessed when single • IV = new partners’ partner preferences

Table of Results Table 2 Multilevel Models Testing the Effects of Original Participants’ Ideal Preferences Predicting New Partners’ Self-Perceptions (Model 1) and New Partners’ Ideal Preferences Predicting Original Participants’ Self-Perceptions (Model 2) Model 1 Model 2 Analysis b SE t 95% CI r Original Analysis . 36 . 07 5. 29*** . 22, . 49 . 14 . 33 . 06 5. 91*** . 22, . 44 . 16 Self-Evaluations Included . 27 . 06 4. 56*** . 15, . 38 . 12 . 25 . 05 4. 90*** . 15, . 35 . 13 No Dating History Only . 42 . 08 5. 58*** . 27, . 57 . 17 . 37 . 07 5. 68*** . 24, . 50 . 17 Stereotype Accuracy . 30 . 06 5. 21*** . 19, . 41 . 14 . 26 . 05 4. 97*** . 16, . 37 . 13 Note. Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Approximate effect sizes were computed using the formula r = √(t 2/(t 2 + df)) (see Rosenthal & Rosnow, 2007). Degrees of freedom ranged between 1333 -1395 for models estimated with all couples, and were 1101 for the models with couples with no dating history. ***p <. 001

Thoughts • What the data imply: – In our sample, participants entered relationships with others that had qualities (self-reported) positively corresponding their preferences when single • What the data do not imply: – How this happened

What is Needed • (1) Replication with larger sample • (2) Larger sample would also allow for tests of between-dyad associations • E. g. , predicting relationship quality, stability • (3) Exactly how might preferences influence mate choice? • New research approaches needed – Go beyond attraction in the lab – But manage to assess variability in potential partner options as well as actual mate choices given these options