Supreme Court and Third Circuit Update With special

- Slides: 52

Supreme Court and Third Circuit Update With special ethics bonus Clients’ Social Media Posts and BOP Emails Keith M. Donoghue, AFD (Appeals Unit) Federal Community Defender Office November 10, 2016 Slides to be posted at: http: //pae. fd. org/CJA. html

SUPREME COURT June 2016 Decisions

Utah v. Strieff, 136 S. Ct. 2056 (June 20, 2016) (Thomas, J. ) • Held, outstanding arrest warrant unknown to officer at time of unlawfully stopping the wanted person, but then discovered by warrants check, sufficiently attenuated link between initial stop and subsequent search incident to arrest to permit admission of evidence recovered in search.

Utah v. Strieff, 136 S. Ct. 2056 (Thomas, J. ) • “First, we look to the ‘temporal proximity’ between the unconstitutional conduct and the discovery of evidence to determine how closely the discovery of evidence followed the unconstitutional search. Second, we consider ‘the presence of intervening circumstances. ’ Third, and ‘particularly’ significant, we examine ‘the purpose and flagrancy of the official misconduct. ’ ” • “The outstanding arrest warrant for Strieff’s arrest is a critical intervening circumstance that is wholly independent of the illegal stop. … And, it is especially significant that there is no evidence that Officer Fackrell’s illegal stop reflected flagrantly unlawful police misconduct. ”

Utah v. Strieff, 136 S. Ct. 2056 (Thomas, J. ) • Sotomayor, J. , dissenting: “We must not pretend that the countless people who are routinely targeted by police are ‘isolated. ’ They are the canaries in the coal mine whose deaths, civil and literal, warn us that no one can breath in this atmosphere. They are the ones who recognize that unlawful police stops corrode all our civil liberties and threaten all our lives. ” • Alice Goffman, On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City (Picador 2015). • Potential distinctions (from majority opinion): • “There is no indication that this unlawful stop was part of any systemic or recurrent police misconduct. ” • “The stop was an isolated instance of negligence that occurred in connection with a bona fide investigation of a suspected drug house. ” • “This was not a suspicionless fishing expedition ‘in the hope that something would turn up. ’ “

Birchfield v. North Dakota, 136 S. Ct. 2160 (June 23, 2016) (Alito, J. ) • Whether “motorists lawfully arrested for drunk driving may be convicted of a crime or otherwise penalized for refusing to take a warrantless test measuring the alcohol in their bloodstream. ” • In one recent national survey, the NHTSA found that more than 20% of drivers do not consent to BAC testing. • Breath test: no warrant required • • “Physical intrusion is almost negligible. ” • “Capable of revealing only one bit of information. ” • Not likely to cause additional embarrassment Blood test: warrant required • “Require piercing the skin and extract a part of the subject’s body. ” • Sample can be preserved and used to extract additional information

Taylor v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2074 (June 20, 2016) (Alito, J. ) • Held, government satisfies Hobbs Act’s interstate commerce element if it shows that the defendant “robbed or attempted to rob a drug dealer of drugs or drug proceeds. ” • Government need not show that drugs traveled across state lines. • “As a matter of law, the market for illegal drugs is ‘commerce over which the United States has jurisdiction. ’ “ • Possible ground for distinction: your client did not deliberately target drug dealer or drug proceeds.

Commonwealth of Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle, 136 S. Ct. 1863 (June 9, 2016) (Kagan, J. ) • Held, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and United States not “separate sovereigns” for purposes of double jeopardy bar on successive prosecutions. • Justice Ginsburg joined by Justice Thomas: separate sovereign doctrine “warrants further attention in a future case in which a defendant faces successive prosecutions by parts of the whole USA. ” • Dual sovereignty doctrine diverges from original meaning of Double Jeopardy Clause (cert petition): http: //www. volokh. com/wpcontent/uploads/2013/06/Roach. Petition. pdf

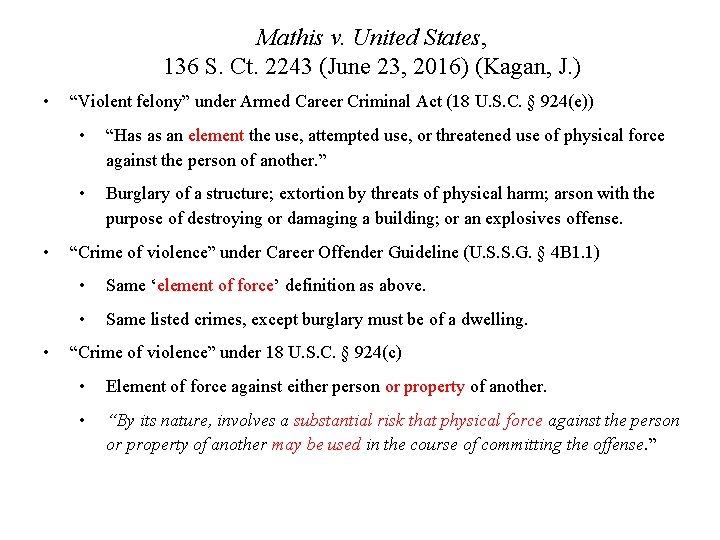

Mathis v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2243 (June 23, 2016) (Kagan, J. ) • • • “Violent felony” under Armed Career Criminal Act (18 U. S. C. § 924(e)) • “Has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another. ” • Burglary of a structure; extortion by threats of physical harm; arson with the purpose of destroying or damaging a building; or an explosives offense. “Crime of violence” under Career Offender Guideline (U. S. S. G. § 4 B 1. 1) • Same ‘element of force’ definition as above. • Same listed crimes, except burglary must be of a dwelling. “Crime of violence” under 18 U. S. C. § 924(c) • Element of force against either person or property of another. • “By its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in the course of committing the offense. ”

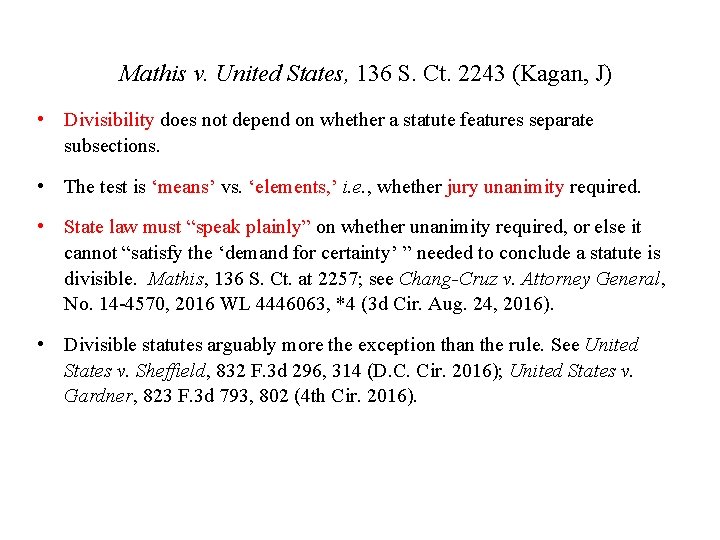

Mathis v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2243 (Kagan, J) • Divisibility does not depend on whether a statute features separate subsections. • The test is ‘means’ vs. ‘elements, ’ i. e. , whether jury unanimity required. • State law must “speak plainly” on whether unanimity required, or else it cannot “satisfy the ‘demand for certainty’ ” needed to conclude a statute is divisible. Mathis, 136 S. Ct. at 2257; see Chang-Cruz v. Attorney General, No. 14 -4570, 2016 WL 4446063, *4 (3 d Cir. Aug. 24, 2016). • Divisible statutes arguably more the exception than the rule. See United States v. Sheffield, 832 F. 3 d 296, 314 (D. C. Cir. 2016); United States v. Gardner, 823 F. 3 d 793, 802 (4 th Cir. 2016).

Mathis v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2243 (Kagan, J) • Divisibility does not depend on whether a statute features separate subsections. • Issue is ‘means’ vs. ‘elements, ’ i. e. , whether jury unanimity required. • State law must “speak plainly” on whether unanimity required, or else it cannot “satisfy [the] ‘demand for certainty’ ” needed to conclude a statute is divisible. Mathis, 136 S. Ct. at 2257; see Chang-Cruz v. Attorney General, No. 14 -4570, 2016 WL 4446063, *4 (3 d Cir. Aug. 24, 2016). • Divisible statutes arguably more the exception than the rule. See United States v. Sheffield, 832 F. 3 d 296, 314 (D. C. Cir. 2016); United States v. Gardner, 823 F. 3 d 793, 802 (4 th Cir. 2016).

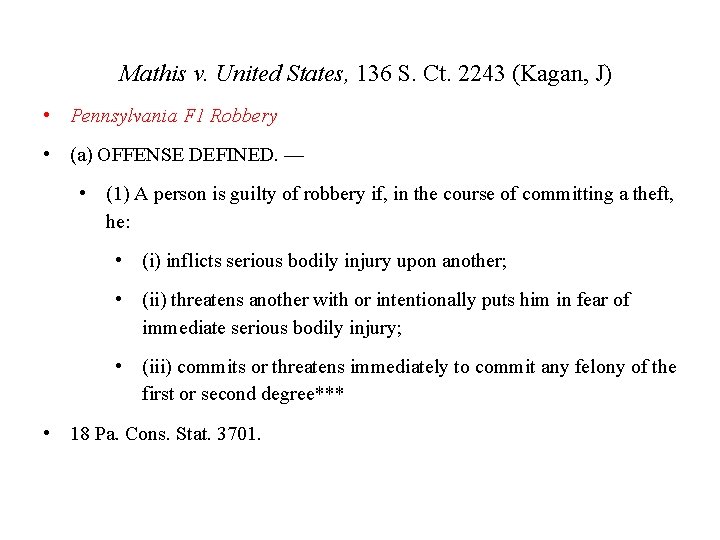

Mathis v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2243 (Kagan, J) • Pennsylvania F 1 Robbery • (a) OFFENSE DEFINED. — • (1) A person is guilty of robbery if, in the course of committing a theft, he: • (i) inflicts serious bodily injury upon another; • (ii) threatens another with or intentionally puts him in fear of immediate serious bodily injury; • (iii) commits or threatens immediately to commit any felony of the first or second degree*** • 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. 3701.

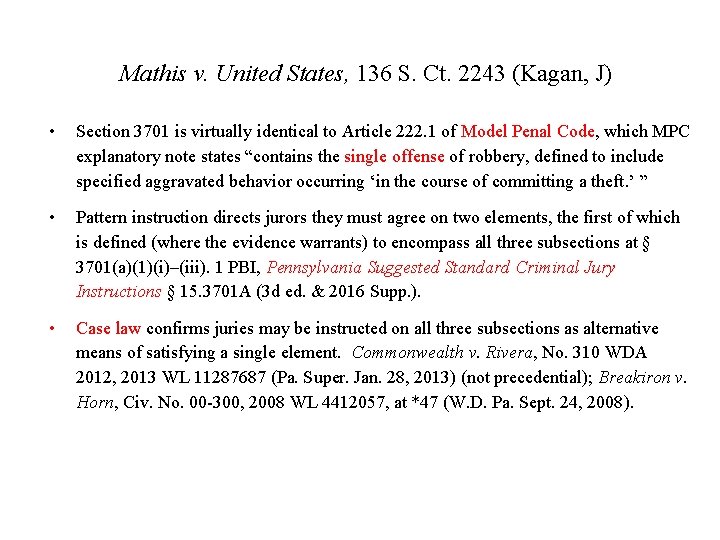

Mathis v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2243 (Kagan, J) • Section 3701 is virtually identical to Article 222. 1 of Model Penal Code, which MPC explanatory note states “contains the single offense of robbery, defined to include specified aggravated behavior occurring ‘in the course of committing a theft. ’ ” • Pattern instruction directs jurors they must agree on two elements, the first of which is defined (where the evidence warrants) to encompass all three subsections at § 3701(a)(1)(i)–(iii). 1 PBI, Pennsylvania Suggested Standard Criminal Jury Instructions § 15. 3701 A (3 d ed. & 2016 Supp. ). • Case law confirms juries may be instructed on all three subsections as alternative means of satisfying a single element. Commonwealth v. Rivera, No. 310 WDA 2012, 2013 WL 11287687 (Pa. Super. Jan. 28, 2013) (not precedential); Breakiron v. Horn, Civ. No. 00 -300, 2008 WL 4412057, at *47 (W. D. Pa. Sept. 24, 2008).

Voisine v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2272 (June 27, 2016) (Kagan, J. ) • Felony punishable by up to 10 years’ imprisonment to possess firearm after conviction of a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. ” 18 U. S. C. § 922(g)(9). • “Congress’s definition of a ‘misdemeanor crime of violence’ contains no exclusion for convictions based on reckless behavior. ” • Different rule for ACCA, career offender guideline, 924(c): Felony ‘crime of violence’ limited to “offenses committed though intentional use of force against another rather than reckless or grossly negligent conduct. ” United States v. Otero, 502 F. 3 d 331, 335 (3 d Cir. 2007).

Foster v. Chatman, 136 S. Ct. 1737 (May 23, 2016) (Roberts, C. J. ) • Held, petitioner entitled to pursue habeas relief based on showing that government exercised purposeful discrimination in use peremptory strikes, in violation of Batson v. Kentucky. • Certain explanations “given by the prosecution, while not explicitly contradicted by the record, are difficult to credit because … ” • Prosecution “willingly accepted white jurors with the same traits. ” • The “prosecution’s principal reasons for the strike shifted over time, suggesting that those reasons may be pretextual. ”

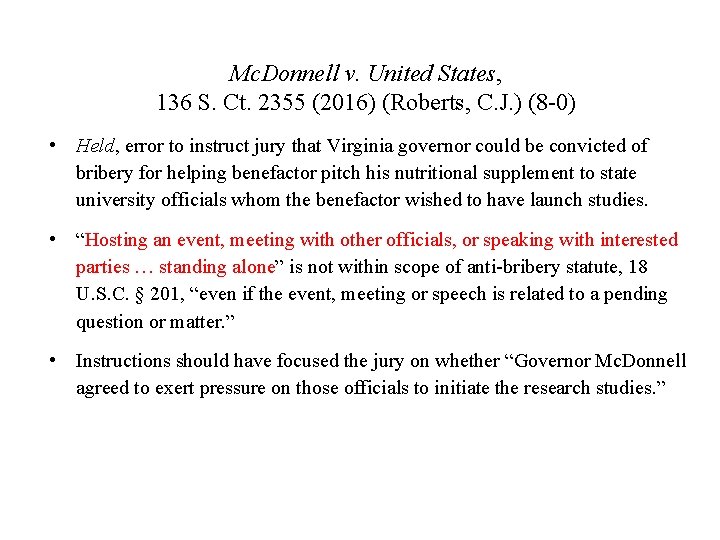

Mc. Donnell v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2355 (2016) (Roberts, C. J. ) (8 -0) • Held, error to instruct jury that Virginia governor could be convicted of bribery for helping benefactor pitch his nutritional supplement to state university officials whom the benefactor wished to have launch studies. • “Hosting an event, meeting with other officials, or speaking with interested parties … standing alone” is not within scope of anti-bribery statute, 18 U. S. C. § 201, “even if the event, meeting or speech is related to a pending question or matter. ” • Instructions should have focused the jury on whether “Governor Mc. Donnell agreed to exert pressure on those officials to initiate the research studies. ”

THIRD CIRCUIT

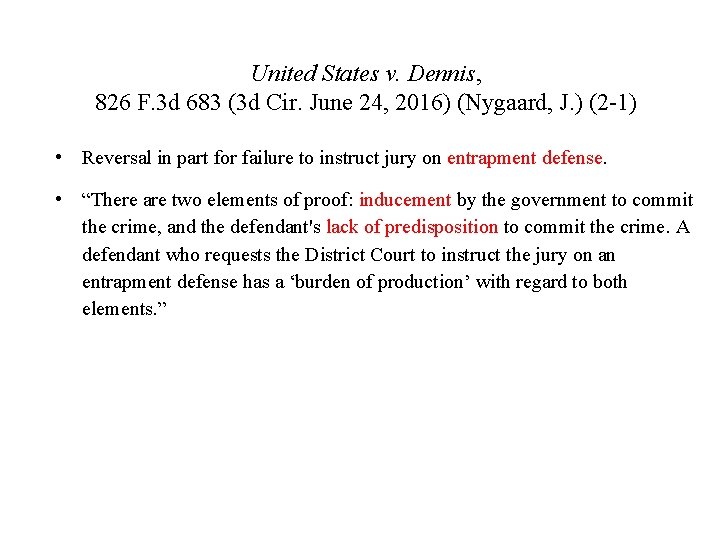

United States v. Dennis, 826 F. 3 d 683 (3 d Cir. June 24, 2016) (Nygaard, J. ) (2 -1) • Reversal in part for failure to instruct jury on entrapment defense. • “There are two elements of proof: inducement by the government to commit the crime, and the defendant's lack of predisposition to commit the crime. A defendant who requests the District Court to instruct the jury on an entrapment defense has a ‘burden of production’ with regard to both elements. ”

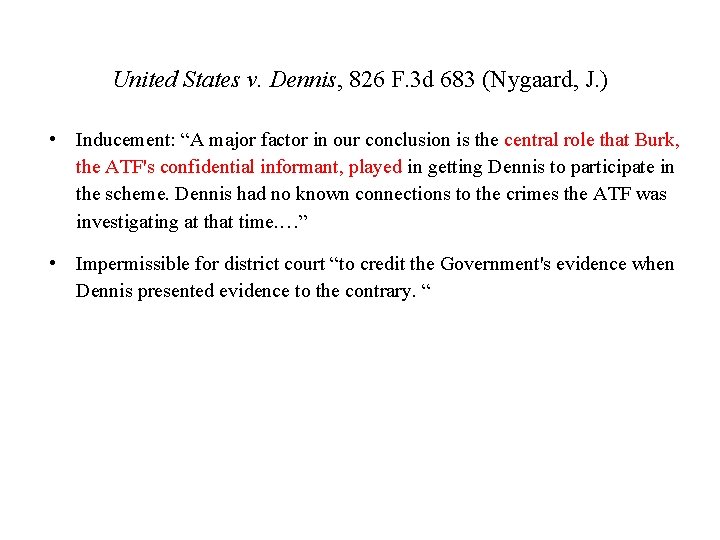

United States v. Dennis, 826 F. 3 d 683 (Nygaard, J. ) • Inducement: “A major factor in our conclusion is the central role that Burk, the ATF's confidential informant, played in getting Dennis to participate in the scheme. Dennis had no known connections to the crimes the ATF was investigating at that time. …” • Impermissible for district court “to credit the Government's evidence when Dennis presented evidence to the contrary. “

United States v. Dennis, 826 F. 3 d 683 (Nygaard, J. ) • Opinion of Judge Ambro, concurring in part: “The Government. … created from whole cloth a fictitious crime … to prosecute someone for a robbery that could not have been committed. … We are judges and not policymakers, and our lodestar is outrageousness and not imprudence. … ‘Although we cannot say that such conduct in and of itself violates the Constitution, it may illustrate the necessity for greater oversight so that questionable police practices can be curbed before they violate our most fundamental laws. ’ “ • Statistical analysis of racial discrimination in ATF stash house prosecutions, and helpful filings: http: //www. law. uchicago. edu/news/federal-criminal-justice-clinic-moves -dismiss-cases-because-atf-discriminated-basis-race

Dennis v. Sec’y Pa. Dep’t of Corrections, 834 F. 3 d 263 (3 d Cir. Aug. 23, 2016) (en banc) • Held, habeas petitioner entitled to new trial due to prosecution’s failure to disclose evidence supporting alibi defense and undermining Commonwealth’s key witness, in violation of Brady v. Maryland. • “To prove a Brady violation, a defendant must show the evidence at issue meets three critical elements. First, the evidence ‘must be favorable to the accused, either because it is exculpatory, or because it is impeaching. ’ Second, it ‘must have been suppressed by the State, either willfully or inadvertently. ’ Third, the evidence must have been material such that prejudice resulted from its suppression. “ • “The mere fact that a witness has been heavily cross-examined or impeached at trial does not preclude a determination that additional impeachment evidence is material under Brady. ”

Dennis, 834 F. 3 d 263 (Mc. Kee, C. J. , concurring) • Numerous grounds on which ID procedures may be challenged: ‘nonblinded’ procedures, insufficiently cautionary instructions to witnesses, feedback to witnesses. • “Jury instructions must educate jurors on the relevant scientific findings regarding eyewitness reliability in order to mitigate the dangers associated with inaccurate eyewitness identifications. The standard instructions, which were used here, are not only insufficient, they are misleading. ” • United States v. Stevens, 935 F. 2 d 1380, 1392, 1407 (3 d Cir. 1991); Moore v. Morton, 255 F. 3 d 95, 121 (3 d Cir. 2001) (Rendell, J. , concurring); see also State v. Henderson, 27 A. 3 d 872, 879 (N. J. 2011), holding modified by State v. Chen, 27 A. 3 d 930 (2011).

Lambert v. Superintendent Greene SCI, 834 F. 3 d 506 (3 d Cir. Aug. 22, 2016) (Ambro, J. ) • Bruton v. United States, 391 U. S. 123 (1968): Confrontation Clause requires exclusion of codefendant’s confession due to “the cognitive dissonance that results from asking jurors to consider a confession only against one defendant. ” • Richardson v. Marsh, 481 U. S. 200 (1987): codefendant’s statement admissible if “redacted to omit all reference” to defendant. • Gray v. Maryland, 523 U. S. 185 (1998): statement not admissible if defendant’s name replaced with an “obvious indication of deletion. ” • Codefendant’s account of shooting: “One of the guys said, ‘She wouldn’t give up her pocketbook, so I banged her. ‘ I told the first guy, ‘You didn’t tell me you had a burner. ’ ”

Binderup v. Attorney General, 836 F. 3 d 336 (3 d Cir. Sept. 17, 2016) (en banc) (Ambro, J. ) • • Held, § 922(g)(1)’s prohibition upon firearm possession violates Second Amendment as applied to two plaintiffs with aged convictions for offenses that were punishable by more than one year of imprisonment but designated as misdemeanors under state law. • 1998 conviction for corruption of a minor, in violation of 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 6301(a)(1)(i), stemming from 41 -year-old man’s “consensual sexual relationship with a 17 -year-old female employee at his bakery. ” • 1990 conviction for carrying a handgun without a license, in violation of Md. Code Ann. Art. 27, § 36 B(b) (1990). Dissenting opinion: “No [other] federal appellate court has yet upheld a challenge, facial or as-applied, to the felon-in-possession statute. ” Decision will require district courts to “make fine-grained distinctions about whether individual felon-inpossession prosecutions can proceed. ”

United States v. Fulton, –F. 3 d–, 2016 WL 4978360 (3 d Cir. Sept. 19, 2016) (Mc. Kee, C. J. ). • Fed. R. Evid. 701 (lay opinion): • If a witness is not testifying as an expert, testimony in the form of an opinion is limited to one that is: • (a) rationally based on the witness’s perception; • (b) helpful to clearly understanding the witness’s testimony or to determining a fact in issue*** • Rule “protects against testimony that usurps the jury’s role as fact finder. ” An agent’s testimony to “an ultimate issue” reserved for the jury “is barred when its primary value is to dictate a certain conclusion. ” • Prosecutor is “free during closing to ask the jury to draw the inference the witness has drawn. But Rule 701(b) prohibits the government from calling a witness to offer this inference through opinion testimony. ”

United States v. Fulton, 2016 WL 4978360 (Mc. Kee, C. J. ) • Motion in limine to exclude witness from offering lay opinion testimony • United States v. Dicker, 853 F. 2 d 1103, 1108 (3 d Cir. 1988) (agent not qualified as expert may not testify to meaning of “code words” in intercepted communications). • United States v. Anderskow, 88 F. 3 d 245, 250 -51 (3 d Cir. 1996) (cooperating witness not permitted to testify that defendant would have known document was fraudulent).

United States v. Calabretta, 831 F. 3 d 128 (3 d Cir. Sept. 15, 2016) (Chagares, J. ) • The term “crime of violence” means any offense under federal or state law, punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year, that— • (1) has as element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another; or • (2) is burglary of a dwelling, arson, or extortion, [or] involves use of explosives, or otherwise involves conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another. • U. S. S. G. § 4 B 1. 2(a) (Nov. 2015). • “It is apparent that if ACCA’s residual clause ‘invites arbitrary enforcement, ’ [Johnson v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 2551, 2557 (2015)], so does the residual clause in § 4 B 1. 2. ”

United States v. Jones, 833 F. 3 d 341 (3 d Cir. Aug. 17, 2016) (Hardiman, J. ) • After considering factors at 18 U. S. C. § 3553(a), court may revoke supervised release and impose imprisonment of not “more than 5 years in prison if the offense that resulted in the term of supervised release is a class A felony … [or] more than 2 years in prison if such offense is a class C or D felony[. ]” 18 U. S. C. § 3583(e)(3). • Held, Johnson does not permit reclassification of offense even if original ACCA sentence was based on priors that no longer qualify as violent felonies. • Validity of “an underlying conviction or sentence may not be collaterally attacked in a supervised release revocation proceeding and may be challenged only on direct appeal or through a habeas corpus proceeding. ”

Staruh v. Superintendent Cambridge Springs SCI, 827 F. 3 d 251 (3 d Cir. June 30, 2016) (Smith, J. ) • Statement Against Interest. A statement that: • (A) a reasonable person in the declarant’s position would have made only if the person believed it to be true because, when made, it … had so great a tendency to … to expose the declarant to … criminal liability; and • (B) is supported by corroborating circumstances that clearly indicate its trustworthiness. … • Pa. R. Evid. / Fed. R. Evid. 804(b)(3). • Grandmother’s “statements had no indicia of credibility. … She was hoping to prevent her daughter from being convicted of murder by confessing to the crime, while at the same time avoiding criminal liability herself. ”

United States v. Dahl, 833 F. 3 d 345 (3 d Cir. Aug. 18, 2016) (Scirica, J. ) • U. S. S. G. § 4 B 1. 5: Enhancement for defendants convicted of a covered sex crime who have at least one prior “sex offense conviction, ” defined to mean “any offense described in 18 U. S. C. § 2426(b)(1)(A) or (B), if the offense was perpetrated against a minor, ” excluding child pornography offenses. • Categorical approach: “If the relevant state or federal statute sweeps more broadly than the generic crime, a conviction under that law cannot count as a predicate, even if the defendant actually committed the offense in its generic form. In other words, we look to the elements of the prior offense to ascertain the least culpable conduct hypothetically necessary to sustain a conviction under the statute. The elements, not the facts, are key. ” • “Applying the categorical approach avoids possible unfairness to defendants” in “recidivist sentencing by avoiding inquiries into the factual circumstances underlying prior convictions. ”

United States v. Stevenson, 832 F. 3 d 412 (3 d Cir. Aug. 9, 2016) (Hardiman, J. ) • Speedy Trial Act directs court to consider three factors, “among others, ” in determining whether to dismiss with or without prejudice: • “the seriousness of the offense” • “the facts and circumstances of the case which led to the dismissal” • “the impact of a reprosecution on the administration of this chapter and on the administration of justice” 18 U. S. C. § 3162(a)(2). • Favoring dismissal with prejudice: • Government has engaged in a “pattern of neglect” • “Sheer length” of delay • Defendant makes affirmative showing of harm caused by delay.

United States v. Rengifo, 832 F. 3 d 220 (3 d Cir. Aug. 5, 2016) (Roth, J. ) Revocations of Probation, Parole, Mandatory Release, or Supervised Release (1) In the case of a prior revocation of probation, parole, supervised release, special parole, or mandatory release, add the original term of imprisonment to any term of imprisonment imposed upon revocation. … (2) Revocation of [supervision] may affect the time period under which certain sentences are counted …. For the purposes of determining the applicable time period, use the following: [a] in the case of an adult term of imprisonment totaling more than one year and one month, the date of last release from incarceration on such sentence … [b] in any other [non-juvenile] case, the date of the original sentence. …” U. S. S. G. § 4 A 1. 2(k).

United States v. Browne, 834 F. 3 d 403 (3 d Cir. Aug. 25, 2016) (Krause, J. ) • “Authentication of social media evidence … presents some special challenges because of the great ease with which a social media account may be falsified or a legitimate account may be accessed by an imposter. ” • “No witness identified the Facebook chat logs on the stand; nothing in the contents of the messages was uniquely known to Browne; and Browne was not the only individual with access to the Button account. ”

United States v. Browne, 834 F. 3 d 403 (Krause, J. ) • Rule 902(11): “The following items of evidence are self-authenticating: … “The original or a copy of a domestic record that meets the requirements of Rule 803(6)(A)-(C) [business records exception to rule against hearsay], as shown by a certification of the custodian. ” • “The relevance of the Facebook records hinges on the fact of authorship. To authenticate the messages, the Government was therefore required to introduce enough evidence that the jury could reasonably find, by a preponderance of the evidence, that Browne and the victims authored the Facebook messages. ” • Records custodian “employed by the social media platform can attest to the accuracy of only certain aspects of the communications, ” i. e. , “that the depicted communications took place between certain Facebook accounts, on particular dates, or at particular times. ”

United States v. Browne, 834 F. 3 d 403 (Krause, J. ) • It is “no less proper to consider a wide range of evidence for the authentication of social media records than it is for more traditional documentary evidence. ” • Held, extrinsic evidence sufficient to establish authorship by preponderance. • Victims’ testimony detailing exchanges was consistent with messages’ content. • Victims testified defendant was the man with whom they met following exchanges. • Defendant admitted he had communicated with some of the victims. • Personal information admitted by defendant consistent with personal details interspersed in Facebook messages.

ADDITIONAL GUIDELINES CASES • United States v. Miller, 833 F. 3 d 274 (Aug. 12, 2016): Broad definition of “investment advisor” as used in fraud guideline, U. S. S. G. § 2 B 1. 1(b)(19), for purposes of 4 -level enhancement where offense involves a violation of securities law. • United States v. Adeolu, 836 F. 3 d 330 (Sept. 12, 2016): No showing of actual harm required to apply “vulnerable victim” enhancement at U. S. S. G. § 3 A 1. 1(b)(1). • United States v. Free, No. 15 -2939, 2016 WL 5845701 (Oct. 6, 2016): In bankruptcy fraud case, loss is not amount of assets the debtor hides from the trustee and creditors; sentencing court must determine the “pecuniary harm, actual or intended, to [the defendant’s] creditors, or what he sought to gain from committing the crime. ” • Slides to be posted at: http: //pae. fd. org/CJA_Materials. html#

CERT GRANTS / PENDING SCOTUS CASES • Shaw v. United States. Whether bank fraud statute at 18 U. S. C. § 1344 requires proof of specific intent to (1) deceive a bank and (2) cheat a bank (as opposed to its customer). • Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado. Whether rule limiting post-verdict inquiry into jury’s deliberations may bar evidence of racial bias offered to prove violation of Sixth Amendment right to impartial jury. • Dean v. United States. Whether Pepper v. United States (2011) overruled decisions limiting a district court’s discretion to consider the mandatory consecutive sentence under 18 U. S. C. § 924(c) when determining appropriate sentence for underlying crime of violence or drug trafficking crime.

CERT GRANTS / PENDING SCOTUS CASES • Salman v. United States. Nature of personal benefit to insider that government must show to sustain conviction under insider trading laws. • Bravo-Fernandez v. United States. In case of inconsistent verdict, whether acquittal portion of the verdict retains preclusive effect under Double Jeopardy Clause where conviction portion of verdict is reversed on appeal. • Pending Johnson progeny: Lynch v. Dimaya (constitutionality of language of Section 924(c)’s “residual clause” defining “crime of violence”); Beckles v. United States (whether Johnson’s due process holding, striking Armed Career Criminal Act’s residual clause as void for vagueness, also invalidates same language in career offender guideline).

ETHICS: NOVEL TECHNOLOGICAL ISSUES CLIENTS’ COMMUNICATIONS VIA SOCIAL MEDIA AND EMAIL

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content Rule 1. 1. Competence. A lawyer shall provide competent representation to a client. Competent representation requires the legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation. Comment: *** Maintaining Competence (8) To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education and comply with all continuing legal education requirements to which the lawyer is subject.

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content • Philadelphia Bar Ass’n, Professional Guidance Committee, Informal Op. No. 2014 -5 (July 1, 2014): http: //www. philadelphiabar. org/Web. Objects/ • PBARead. Only. woa/Contents/Web. Server. Resources/CMSResources/Opinion 20145 Final. pdf • “[A] lawyer should … have a basic knowledge of how social media websites work. ” • See also Pa. Bar Ass’n, Formal Opinion 2014 -300 (“Ethical Obligations for Attorneys Using Social Media”).

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content Philadelphia Bar Ass’n, Professional Guidance Committee, Informal Op. No. 2014 -5 (July 1, 2014). (1) Whether a lawyer may advise a client to change the privacy settings on a Facebook page so that only the client or the client's “friends” may access the content. (2) Whether a lawyer may instruct a client to remove a photo, link or other content that the lawyer believes is damaging. (3) Whether a lawyer who receives a Request for Production of Documents must obtain and produce a copy of a photograph posted by the client, which the lawyer previously saw on the client’s Facebook page, but which the lawyer did not previously print or download.

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content • Fed. R. Crim. P. 26. 2 (third-party witnesses): on government’s motion, court “must order … the defendant and the defendant’s attorney to produce … any statement of the witness that is in their possession and that relates to the subject matter of the witness’s testimony. ” • Advisory committee note: rule is “designed to place the disclosure of prior relevant statements of a defense witness in the possession of the defense on the same legal footing as is the disclosure of prior statements of prosecution witnesses in the hands of the government under the Jencks Act. ”

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content Pa. Rule 3. 4. Fairness to Opposing Party and Counsel. A lawyer shall not … unlawfully obstruct another party’s access to evidence or unlawfully alter, destroy or conceal a document or other material having potential evidentiary value or assist another person to do any such act. Comment: (2) Paragraph (a) applies to evidentiary material generally, including computerized information. Philadelphia Bar Ass’n: “A lawyer may advise a client to change the privacy settings on the client’s Facebook Page, but may not instruct or knowingly allow a client to delete/destroy a relevant photo, link, text or other content. ”

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content • Philadelphia Bar Ass’n: “A lawyer may … instruct a client to delete information that may be damaging from the client’s page, but must take appropriate action to preserve the information in the event it should prove to be relevant and discoverable. ” • In the Matter of Matthew B. Murray, Va. State B. Nos. 11 -070 -088405 and 11 -070 -088422 (June 9, 2013). Five-year suspension and $700 K-plus in sanctions for instructing client to delete damaging photos from Facebook account, withholding photos from opposing counsel, and withholding emails discussing deletion from court.

Removing / Preserving Social Media Content • Philadelphia Bar Ass’n: “A lawyer must make reasonable efforts to obtain a photograph, link or other content about which the lawyer is aware if the lawyer knows or reasonably believes it has not been produced by the client. ”

Email Communications via BOP ‘Corrlinks’ • BOP Program Statement 4500. 11 (Apr. 9, 2015): • “Emails sent/received by inmates are stored and are subject to monitoring for content by trained staff. If it is determined locally that workload permits, all staff may be assigned to monitor emails. ” • “Inmates identified as ‘required monitoring’ in SENTRY shall have their emails monitored and reviewed. ” • “[T]o the extent that defendant engaged in telephone conversations with attorneys on the monitored line the communications were not privileged. Defendant had no expectation of privacy in these conversations. They were knowingly made in the presence of the Bureau of Prisons through its taping and monitoring procedures. This constitutes a waiver of any privilege that might otherwise have existed. ” United States v. Pelullo, 5 F. Supp. 2 d 285, 289 (D. N. J. 1998), aff’d, 185 F. 3 d 863 (3 d Cir. 1999) (tbl. ).

Email Communications via BOP ‘Corrlinks’ • Pa. R. Prof’l Conduct 1. 6. • (d) A lawyer shall make reasonable efforts to prevent the inadvertent or unauthorized disclosure of, or unauthorized access to, information relating to the representation of a client. • *** • Comment (26): “When transmitting a communication that includes information relating to the representation of a client, the lawyer must take reasonable precautions to prevent the information from coming into the hands of unintended recipients. . … A client … may give informed consent to the use of a means of communication that would otherwise be prohibited by this Rule. ”

Email Communications via BOP ‘Corrlinks’ Pa. R. Prof’l Conduct 1. 4 (a) A lawyer shall: *** (3) keep the client reasonably informed about the status of the matter; (4) promptly comply with reasonable requests for information; (b) A lawyer shall explain a matter to the extent reasonably necessary to permit the client to make informed decisions regarding the representation.

ABA Formal Opinion No. 11 -459: Duty to Protect Confidentiality of Email Communications with One’s Client • “A lawyer sending or receiving substantive communications with a client via e-mail or other electronic means ordinarily must warn the client about the risk of sending or receiving electronic communications using a computer or other device, or e-mail account, where there is a significant risk that a third party might gain access. ” • “The lawyer must take reasonable care to protect the confidentiality of the communications by giving appropriately tailored advice to the client. ”

Email Communications via BOP ‘Corrlinks’ • American Bar Association, House of Delegates, Resolution No. 10 A (Feb. 8, 2016), at http: //www. americanbar. org/news/reporter_resources/midyear-meeting-2016/house-ofdelegates-resolutions. htmld • “RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Prisons to amend their policies with respect to monitoring emails between attorneys and their incarcerated clients to permit attorneys and their incarcerated clients to communicate confidentially via email and thereby maintain the attorney-client privilege. ” • Accompanying report: “[T]raditional postal mail, unmonitored telephone calls, [and] inperson visits are not adequate alternatives to unmonitored emails. ” • See also United State v. Ahmed, Crim. No. 14 -277 (E. D. N. Y. June 27, 2014) (minute entry); United States v. Saade, Crim. No. 11 -111 (S. D. N. Y. Sept. 26, 2011) (minute entry) (both barring government from viewing attorney-client emails sent over Corrlinks).

Johnson Litigation Update • Baptiste v. Attorney General, –F. 3 d–, 2016 WL 6595943 (3 d Cir. Nov. 8, 2016). Language identical to “residual clause” at Section 924(c)(3) held unconstitutionally vague, at least as used in definition of “crime of violence” codified at 18 U. S. C. § 16(b). Circuit split. • Lynch v. Dimaya, Sup. Ct. No. 15 -1498 (cert granted Sept. 29): Whether 18 U. S. C. 16(b) … is unconstitutionally vague. • Beckles v. United States, Sup. Ct. No. 15 -8544 (to be argued Nov. 28): Whether Johnson applies to the career offender guideline. • United States v. Robinson, 3 d Cir. No. 15 -1402 (argued Apr. 18): Whether Hobbs Act robbery qualifies as predicate crime of violence supporting prosecution under 924(c).