Part Three TQM The Tools and the Improvement

- Slides: 33

Part Three TQM – The Tools and the Improvement Cycle Chapter # 8 Tools and techniques for quality improvement Greg Baker © 2004 1

Greg Baker © 2004 Chapter Outline l l 2 8. 1 A systematic approach 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) 8. 5 Quality improvement techniques in nonmanufacturing

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 1 A systematic approach l l 3 In addition to the basic elements of a quality system that provide a framework for recording, there exists a set of methods the Japanese quality guru Ishikawa has called the seven basic tools. These should be used to interpret and derive the maximum use from data.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 1 A systematic approach l Ø Ø Ø Ø 4 The simple methods listed below, of which there are clearly more than seven, will offer any organization means of collecting, presenting, and analyzing most of its data: Process flowcharting – what is done? Check sheets/tally charts – how often is it done? Histograms – what do overall variations look like? Scatter diagrams – what are the relationships between factors? Pareto analysis – which are the big problems? Cause and effect analysis and Brainstorming – what causes the problems? Control charts – which variations to control and how?

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 1 A systematic approach l l l 5 The effective use of the tools requires their application by the people who actually work on the process. Managers must show they are serious by establishing a systematic approach and providing the training and implementation support required. A focus on improvement opportunities leads to the creation of teams whose membership is determined by their work on and detailed knowledge of the process, and their ability to take improvement action.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 1 A systematic approach l l 6 By using reliable methods, creating a favorable environment for team based problem solving, and continuing to improve using systematic techniques, the never-ending improvement helix will be engaged. This approach requires a change in the language of many organizations from percentage defects, percentage 'prime' product, and number of errors, to process capability.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 1 A systematic approach l l 7 The traditional approach 'If it meets the specification, there are no problems and no further improvements are necessary'. The driving force for this will be the need for better internal and external customer satisfaction levels, which will lead to the continuous improvement question, 'Could we do the job better? '.

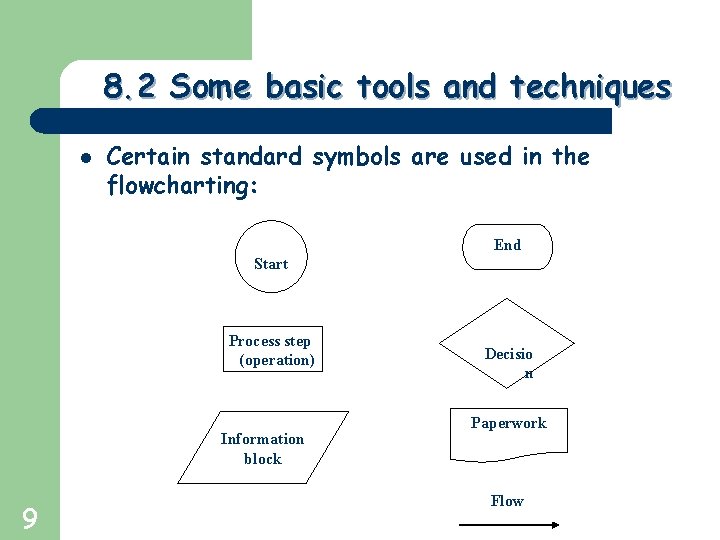

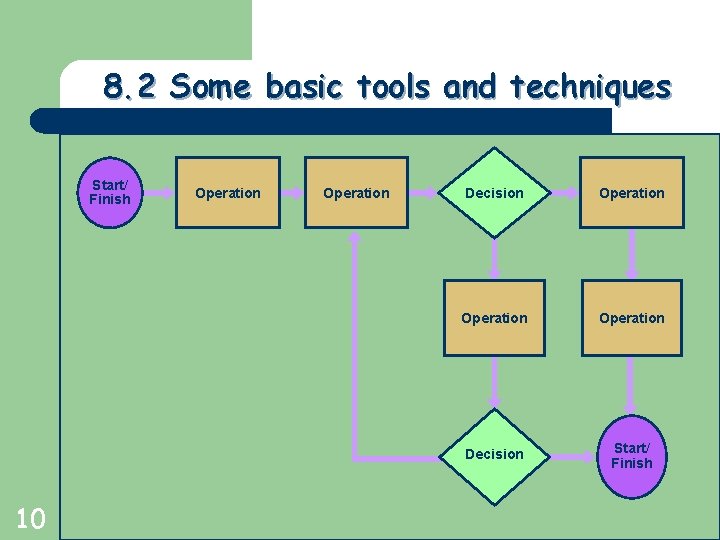

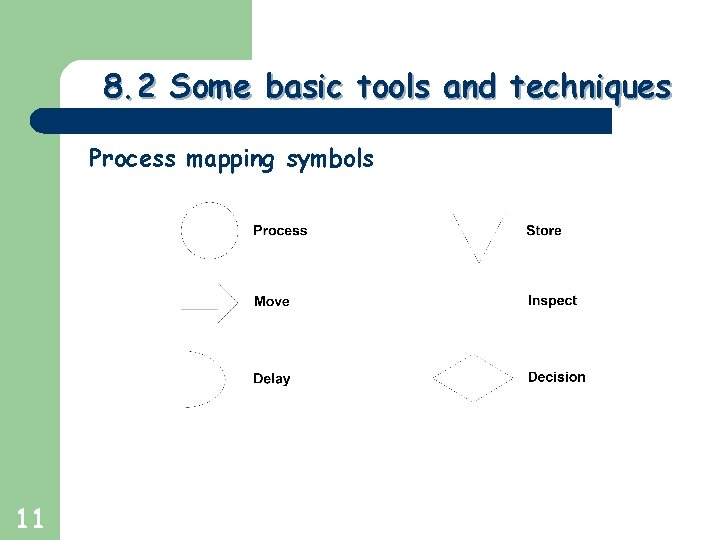

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Process flowcharting l l 8 To ensure a full understanding of the inputs and flow of the process. The process chart lists every step that is involved in the manufacturing of a product or the delivery of a service. It is a good idea to draw the process chart using the standard symbols because this aids clarity. A flow chart is similar to process chart and is often used when there are decisions involved.

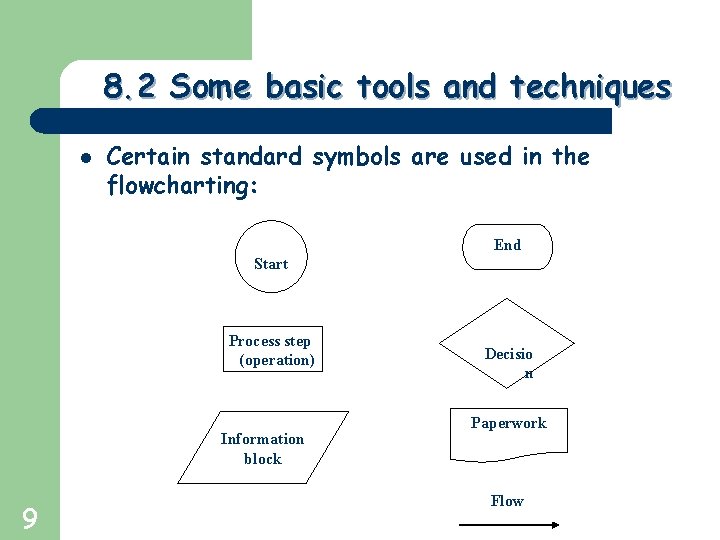

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques l Certain standard symbols are used in the flowcharting: End Start Process step (operation) Information block 9 Decisio n Paperwork Flow

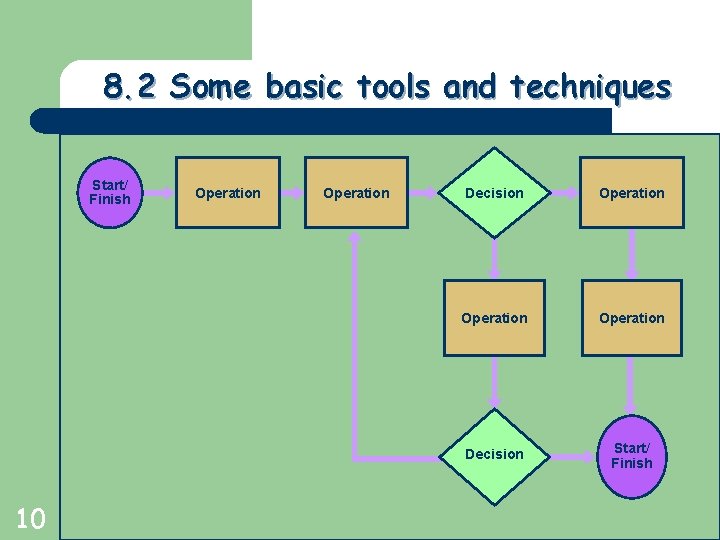

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Start/ Finish 10 Operation Decision Operation Decision Start/ Finish

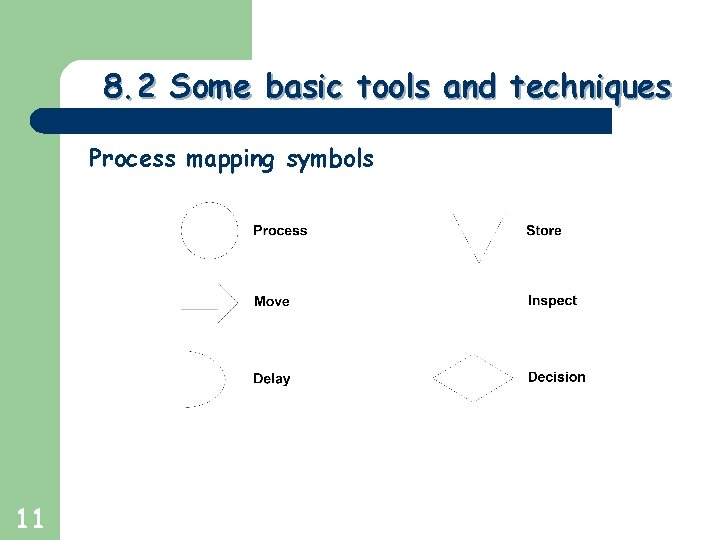

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Process mapping symbols 11

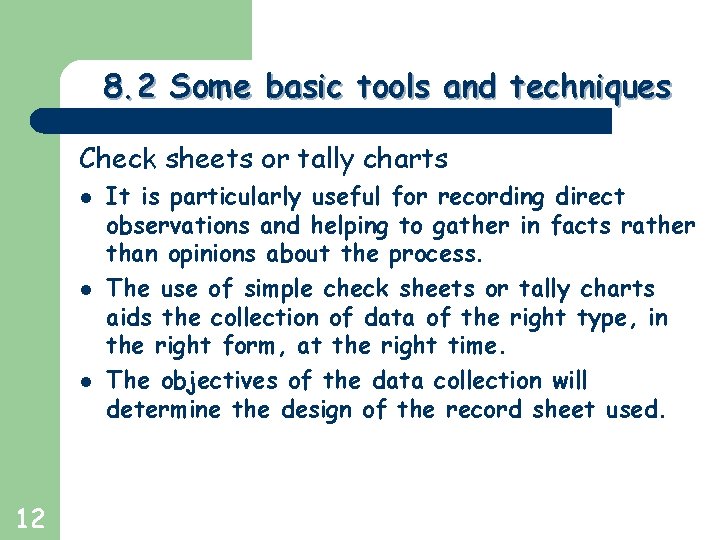

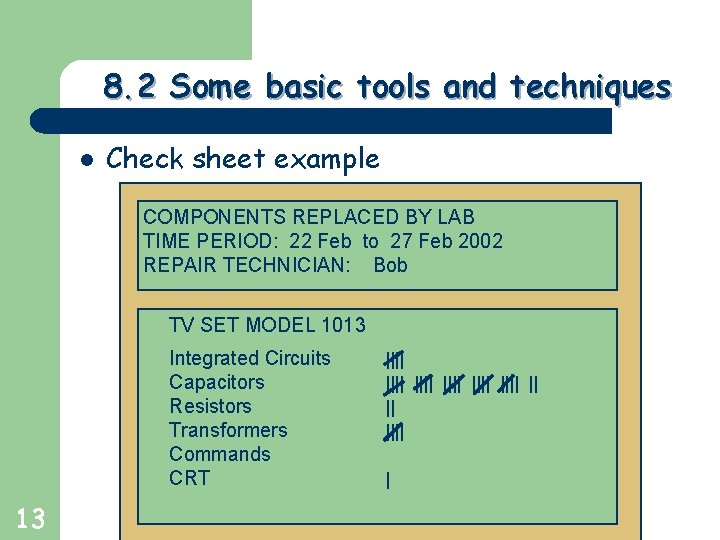

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Check sheets or tally charts l l l 12 It is particularly useful for recording direct observations and helping to gather in facts rather than opinions about the process. The use of simple check sheets or tally charts aids the collection of data of the right type, in the right form, at the right time. The objectives of the data collection will determine the design of the record sheet used.

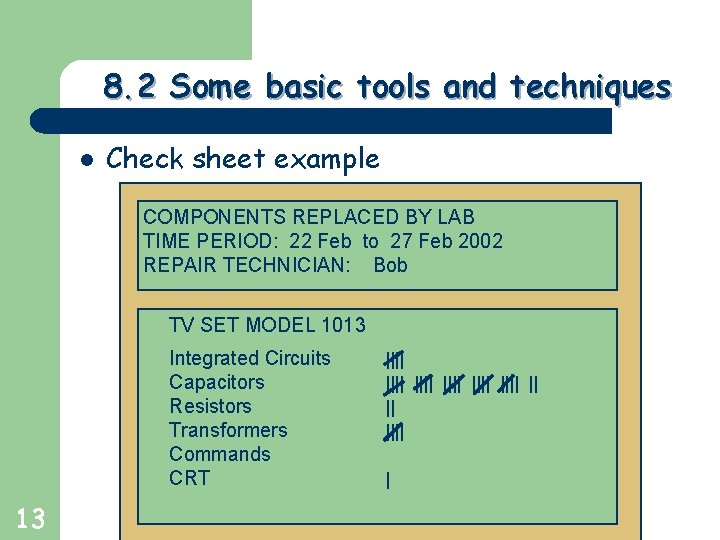

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques l Check sheet example COMPONENTS REPLACED BY LAB TIME PERIOD: 22 Feb to 27 Feb 2002 REPAIR TECHNICIAN: Bob TV SET MODEL 1013 Integrated Circuits Capacitors Resistors Transformers Commands CRT 13 |||| |||| |||| |

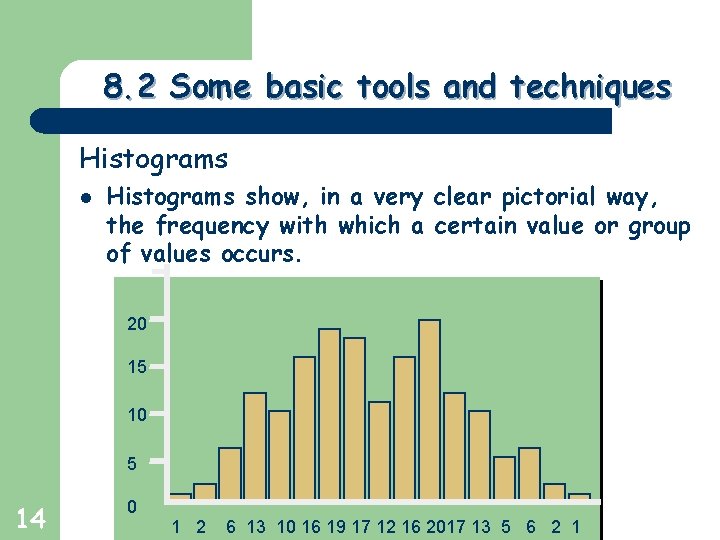

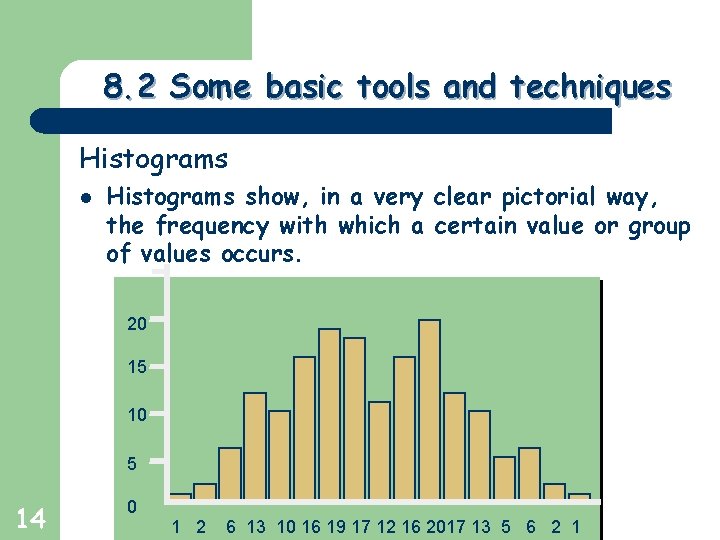

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Histograms l Histograms show, in a very clear pictorial way, the frequency with which a certain value or group of values occurs. 20 15 10 5 14 0 1 2 6 13 10 16 19 17 12 16 2017 13 5 6 2 1

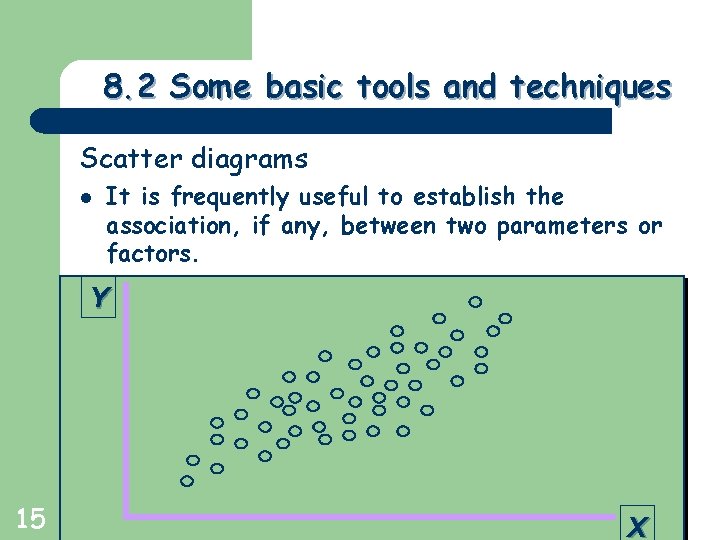

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Scatter diagrams l It is frequently useful to establish the association, if any, between two parameters or factors. Y 15 X

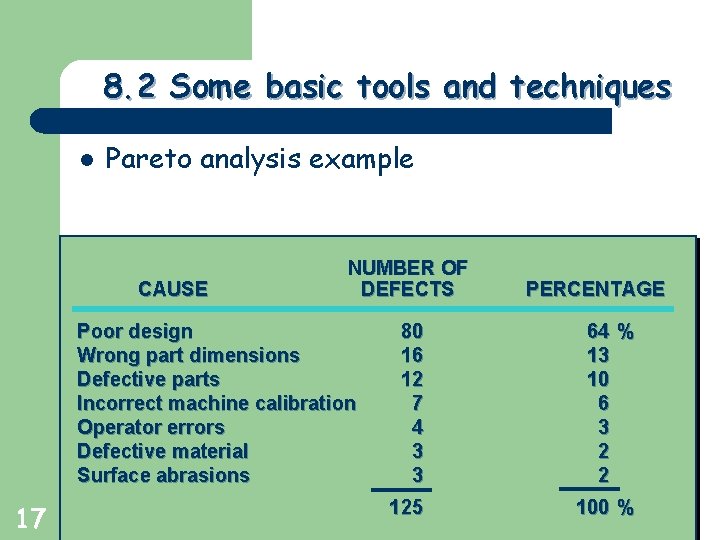

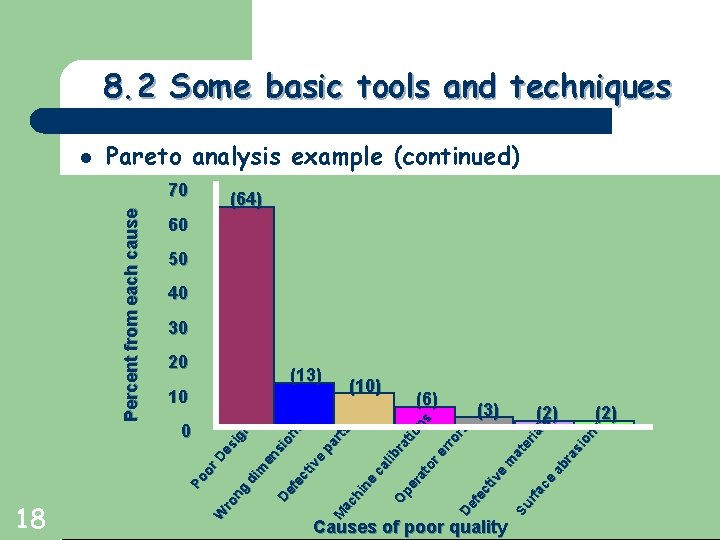

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Pareto analysis l l 16 If symptoms or causes of defective output or some other 'effect' are identified and recorded, it will be possible to determine what percentage can be attributed to any cause, and the probable results will be that the bulk (typically 80 per cent) of errors, waste, or 'effects' derive from a few of the causes (typically 20 per cent). Pareto analysis begins by ranking problems from highest to lowest.

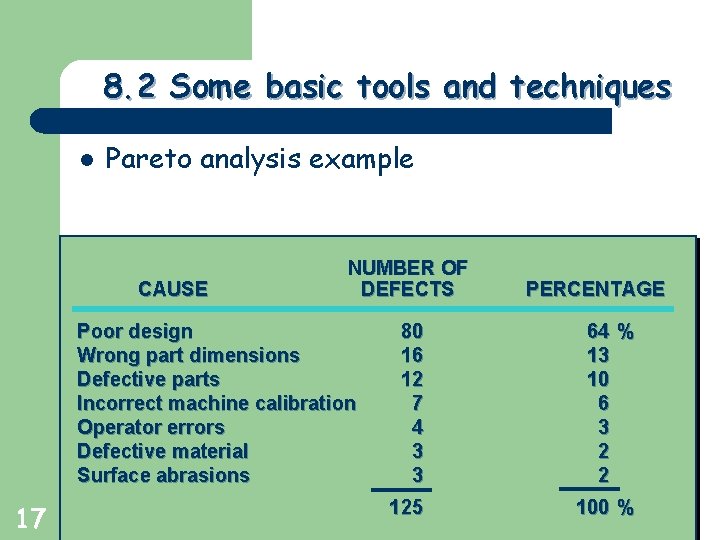

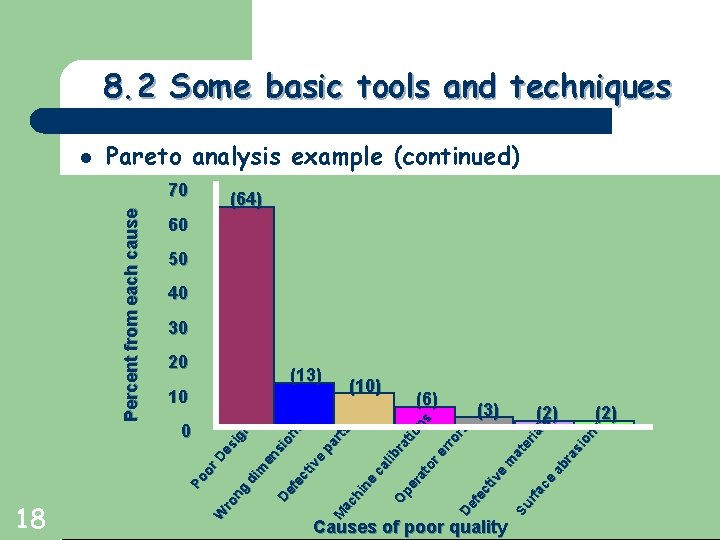

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques l Pareto analysis example CAUSE NUMBER OF DEFECTS Poor design Wrong part dimensions Defective parts Incorrect machine calibration Operator errors Defective material Surface abrasions 17 PERCENTAGE 80 16 12 7 4 3 3 64 % 13 10 6 3 2 2 125 100 %

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques l Pareto analysis example (continued) 18 (64) 60 50 40 30 20 10 (13) (10) (6) (3) (2) Po or W De ro si ng gn di m en si De on fe s ct iv e pa rts M ac hi ne ca lib O ra pe tio ra ns to re rr or s De fe ct iv e m at Su er rfa ia ls ce ab ra si on s Percent from each cause 70 0 Causes of poor quality

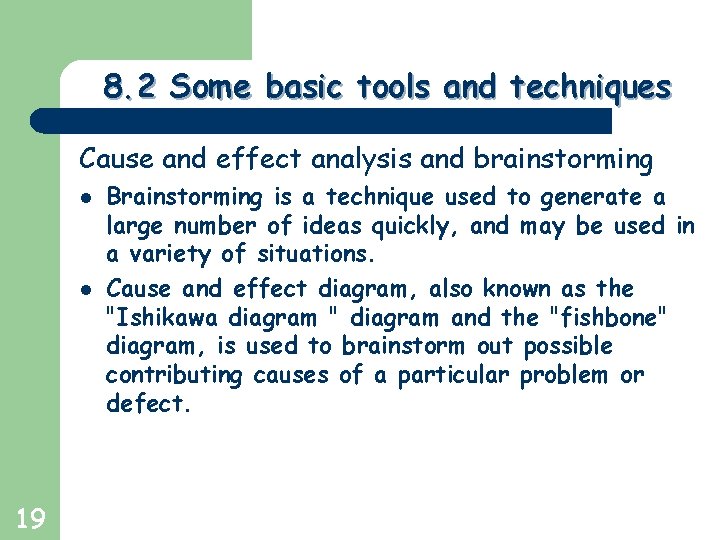

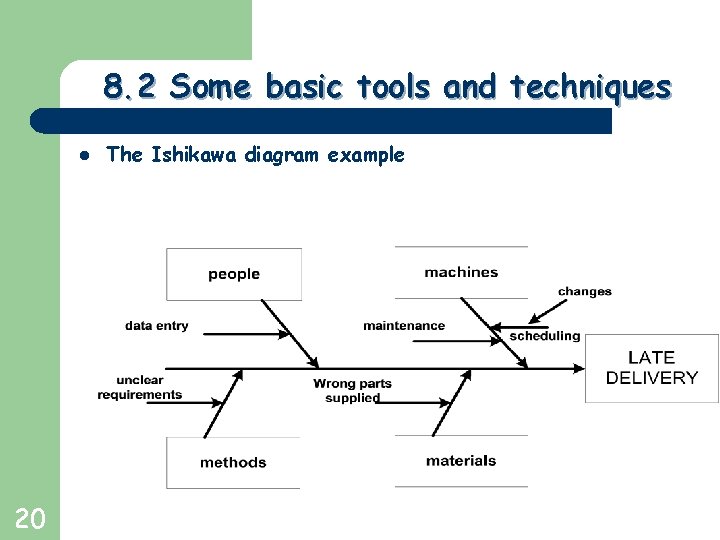

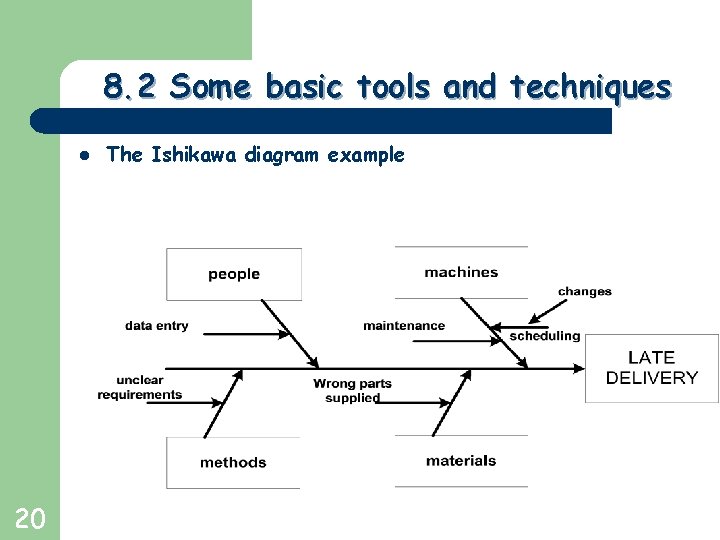

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Cause and effect analysis and brainstorming l l 19 Brainstorming is a technique used to generate a large number of ideas quickly, and may be used in a variety of situations. Cause and effect diagram, also known as the "Ishikawa diagram " diagram and the "fishbone" diagram, is used to brainstorm out possible contributing causes of a particular problem or defect.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques l 20 The Ishikawa diagram example

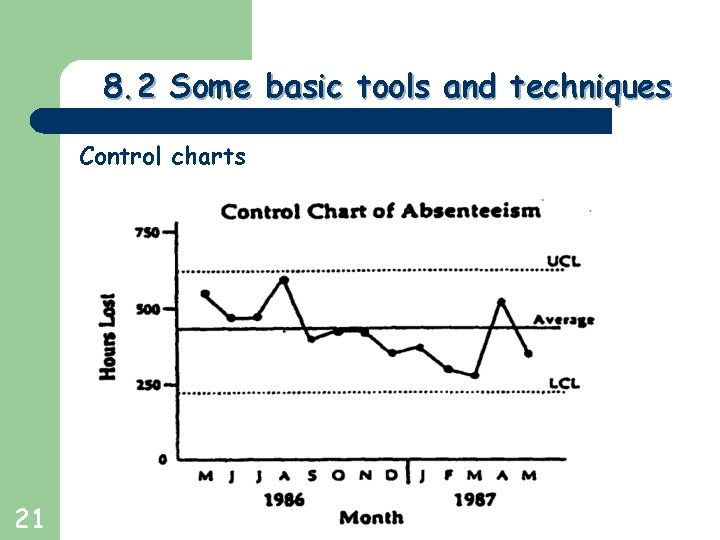

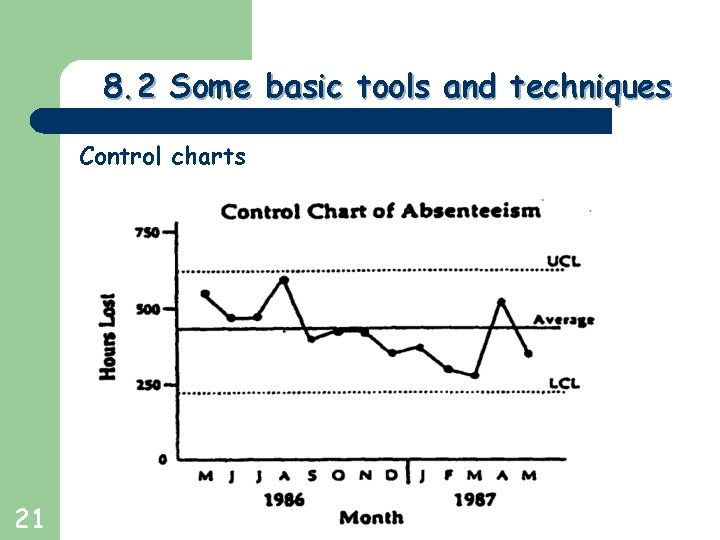

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 2 Some basic tools and techniques Control charts 21

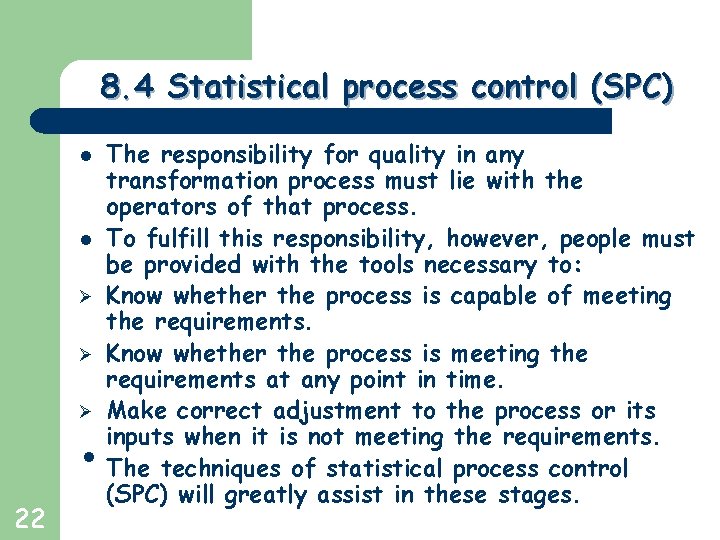

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l l Ø Ø Ø • 22 The responsibility for quality in any transformation process must lie with the operators of that process. To fulfill this responsibility, however, people must be provided with the tools necessary to: Know whether the process is capable of meeting the requirements. Know whether the process is meeting the requirements at any point in time. Make correct adjustment to the process or its inputs when it is not meeting the requirements. The techniques of statistical process control (SPC) will greatly assist in these stages.

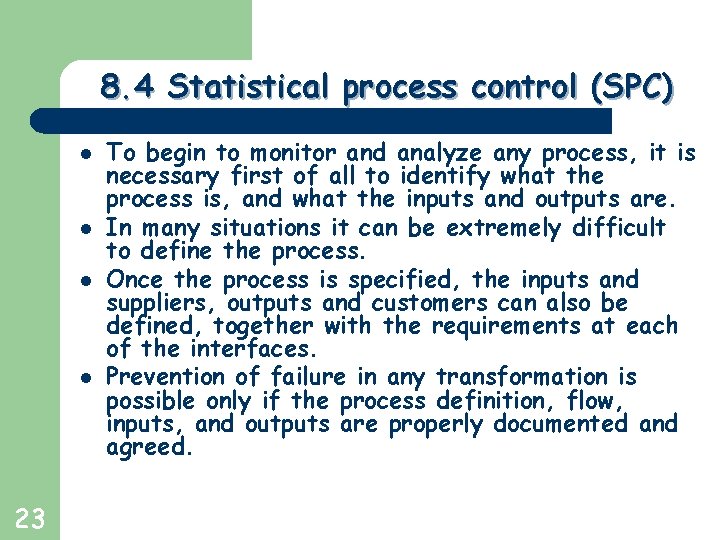

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l l 23 To begin to monitor and analyze any process, it is necessary first of all to identify what the process is, and what the inputs and outputs are. In many situations it can be extremely difficult to define the process. Once the process is specified, the inputs and suppliers, outputs and customers can also be defined, together with the requirements at each of the interfaces. Prevention of failure in any transformation is possible only if the process definition, flow, inputs, and outputs are properly documented and agreed.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l l 24 The documentation of procedures will allow reliable data about the process itself to be collected, analysis to be performed, and action to be taken to improve the process and prevent failure or non-conformance with the requirements. SPC methods, backed by management commitment and good organization, provide objective means of controlling quality in any transformation process, whether used in the manufacture of artefacts, the provision of services, or the transfer of information.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l l 25 SPC is not only a toolkit, it is a strategy for reducing variability, the cause of most quality problems: variation in products, in times of deliveries, in ways of doing things, in materials, in people's attitudes, in equipment and its use, in maintenance practices, in every thing. Total quality management requires that the processes should be improved continually by reducing variability.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l It is worth repeating that SPC is not only about plotting charts on the walls of a plant or office, it must become part of the company-wide adoption of TQM and act as the focal point of never-ending improvement. The SPC system Ø Ø Ø 26 A systematic study of any process though answering the questions: Are we capable of doing the job correctly? Do we continue to do the job correctly? Have we done the job correctly? Could we do the job more consistently and on target?

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 4 Statistical process control (SPC) l l l 27 SPC techniques may be used to measure and control the degree of variation of any purchased materials, services, processes, and products, and to compare this, if required, to previously agreed specifications. In essence, SPC techniques select a representative, simple, random sample from the 'population', which can be an input to or an output from a process. From an analysis of the sample it is possible to make decisions regarding the current performance of the process.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 5 Quality improvement techniques in non-manufacturing l l 28 Organizations that embrace the TQM concepts should recognize the value of SPC techniques in areas such as sales, purchasing, invoicing, finance, distribution, training, and in the service sector generally. Theses are outside the traditional areas for SPC use, but SPC needs to be seen as an organization -wide approach to reducing variation with the specific techniques integrated into a program of change throughout.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 5 Quality improvement techniques in non-manufacturing l Ø Ø Ø 29 Ø Some of the most exciting applications of SPC have emerged from organizations and departments which, when first introduced to the methods, could see little relevance in them to their own activities. Following appropriate training, however, they have learned how to, for example: Pareto analyze errors on invoices to customers. Brainstorm and cause and effect analyze reasons for late payment. Histogram defects in invoice matching and arrival of trucks at certain times during the day. Control chart the weekly demand of a product.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 5 Quality improvement techniques in non-manufacturing l l l 30 Distribution staff have used control charts to monitor the proportion of late deliveries, and Pareto analyses to look at complaints about the distribution system. Those organizations that have made most progress in implementing continuous improvement have recognized at an early stage that SPC is for the whole organization. Applying the methods and techniques outside manufacturing will make it easier, not harder, to gain maximum benefit from an SPC program.

Greg Baker © 2004 8. 5 Quality improvement techniques in non-manufacturing l l 1. 2. l 31 Sales, marketing and customer-service areas often resistant to SPC training on the basis that it is difficult to apply. Personnel in these vital functions need to be educated in SPC methods for two reasons: They need to understand the way the manufacturing or service producing processes in their organizations work. They will be able to improve the marketing processes and activities. SPC has considerable applications for nonmanufacturing organizations, including universities, hospitals, schools……

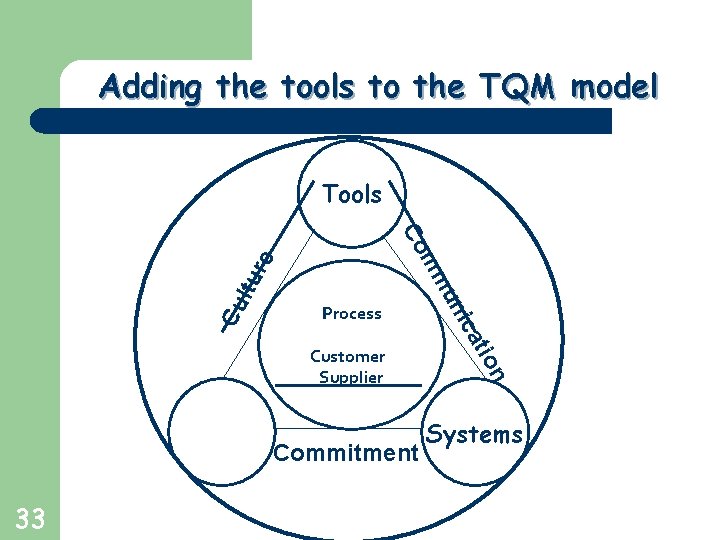

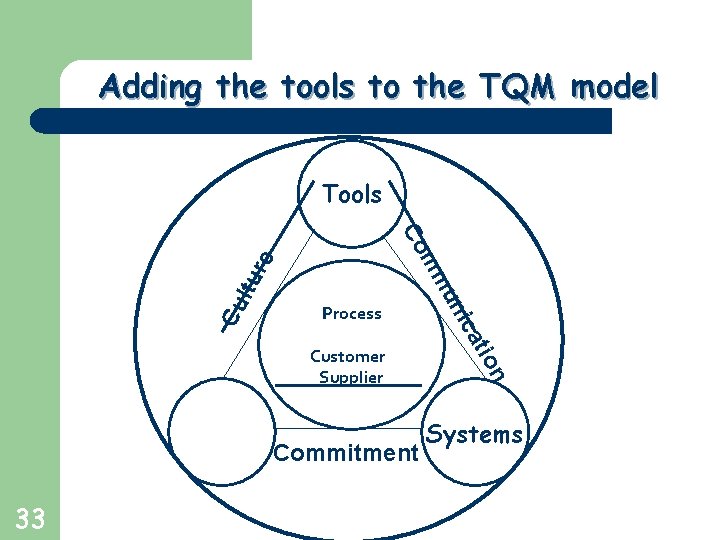

Greg Baker © 2004 Adding the tools to the TQM model l l 32 Having looked at some of the many tools and techniques of measurement and improvement, we see that the generic term ‘tools’ may be added, as the second hard management necessity, to the TQM model. The systems manage the processes, and the tools are used to progress further round the improvement cycle by creating better customersupplier relationships, both externally and internally.

Greg Baker © 2004 Adding the tools to the TQM model Tools n Cu ltu 33 tio Commitment ica Customer Supplier un mm re Co Process Systems