NANTAI NVERSTES HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY ktisadi dari ve Sosyal

- Slides: 24

NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY İktisadi, İdari ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi iisbf. nisantasi. edu. tr NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ ©

PART I BEING AND STAYING HEALTHY CHAPTER 1 WHAT IS HEALTH?

LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of this chapter, you should have an understanding of: • key perspectives on health, illness and disability, including the biomedical and biopsychosocial models • the influence of lifestage, culture and health status on health and illness concepts • a range of influences on the domains of health considered important • the role of psychology, and specifically the discipline of health psychology, in understanding health, illness and disability • how health is more than simply the absence of physical disease or disability

MODELS OF HEALTH AND ILLNESS Mind–body relationships Disease attributed to evil spirits and punishment from the gods Hippocrates (circa 460– 377 BC) – Humoural theory Descartes (1596– 1650) – Dualism • Mechanistic view, underpins the biomedical model Biomedical model Diseases and symptoms have underlying pathological cause • Reductionist Biopsychosocial model Disease and symptoms are explained by a combination of physical, cultural, psychological and social factors

CHALLENGING DUALISM Dualism – the idea that the mind and body are separate entities (cf. Descartes) vs. Monoism – viewing them as one unit; one type of ‘stuff’ Psychology has played a significant role in altering both of these perspectives – due to an increased understanding of the bidirectional relationship between body and mind.

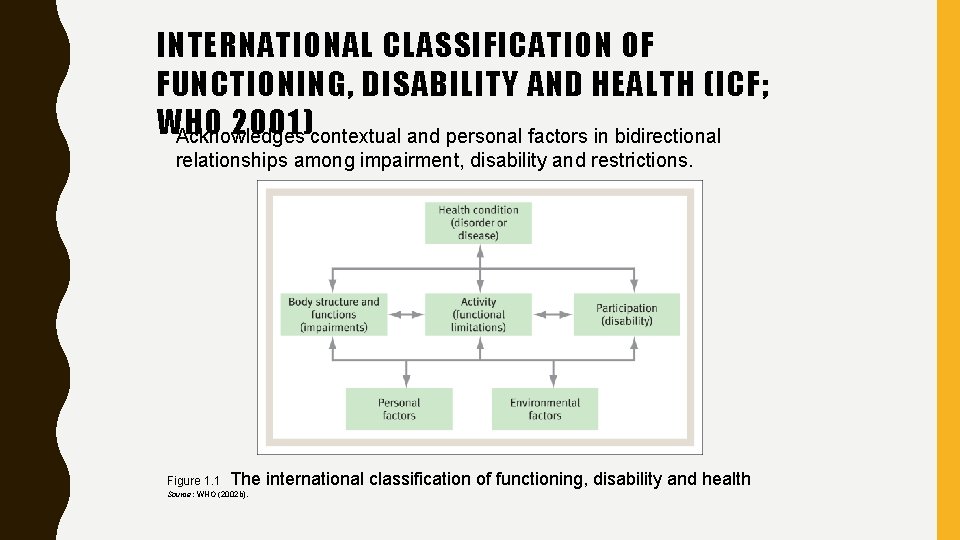

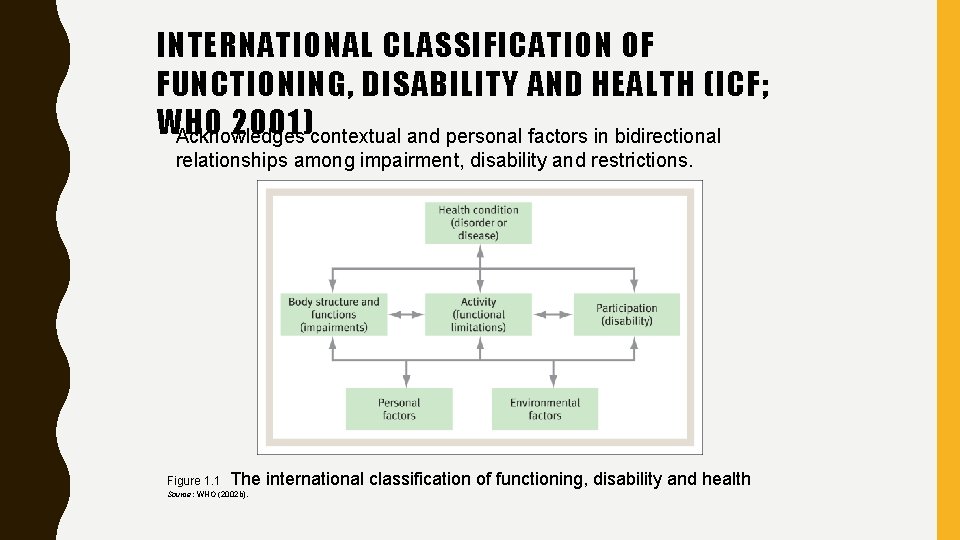

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTIONING, DISABILITY AND HEALTH (ICF; WHO 2001)contextual and personal factors in bidirectional Acknowledges relationships among impairment, disability and restrictions. Figure 1. 1 The international classification of functioning, disability and health Source: WHO (2002 b).

LAY THEORIES OF HEALTH Bauman (1961) asked ‘What does being healthy mean? ’ The three main types of response were: • a ‘general sense of well-being’; • identified with ‘the absence of symptoms of disease’; • seen in ‘the things that a person who is physically fit is able to do’. She argued that these three types of response reveal health to be related to: • feeling • symptom orientation • performance.

SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF HEALTH The Health and Lifestyles survey (Cox et al. 1993) The categories of health identified were as follows: Health as not ill (i. e. no symptoms, no doctor visits, therefore I’m healthy) Health as reserve (i. e. come from strong family; recover quickly from operation) Health as behaviour (i. e. usually applied to others rather than self; e. g. they are healthy because they look after themselves, exercise, etc. ) Health as physical fitness and vitality (used more often by younger respondents, and often in reference to males) Health as psychosocial wellbeing (health defined in terms of mental state; e. g. in harmony, feeling proud, or more specifically, enjoying others) Health as function (idea of health as the ability to perform one’s duties; i. e. being able to do what you want when you want without being handicapped by ill health or physical limitation)

DEFINITION OF HEALTH? According to the World Health Organization. . . ‘State of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and. . . not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (1947) • does not address socio-economic and cultural influences on health, illness and health decisions; • omits the major role of the ‘psyche’ in the experience of health and illness.

CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES ON HEALTH Cultures vary in their health belief systems. Holistic explanations Westernised treatment divides mind, body and soul whereas non-Westerners integrate these ‘three elements of human nature’ Spiritual explanations Uncommon in Western civilisations e. g. faith, God’s reward • supernatural forces such as ‘hexes’ and ‘evil eye’ Collectivist vs. individualistic Eastern communities locate health and illness in the social world vs. Westernised behaviour driven by individual needs

LIFESPAN, AGEING AND BELIEFS ABOUT HEALTH AND ILLNESS Growing older may be associated with decreased functioning, increased disability or dependence, however it is not only older people who live with chronic illness. There are developmental issues that health professionals should be aware of. Developmental theories The developmental process is a function of interaction among three factors: Learning: a relatively permanent change in knowledge, skill or ability as a result of experience. Experience: what we do, see, hear, feel, think. Maturation: thought, behaviour or physical growth, attributed to ageing and development rather than to experience.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Piaget (1930, 1970) proposed a staged structure to cognitive development which all individuals follow in sequence. Sensorimotor (birth– 2 years): understands the world through sensations and movement Preoperational (2– 7 years): symbolic thought develops, as does simple logic and language Concrete operational (7– 11 years): abstract thought and logic develops hugely, performs mental operations and manipulation Formal operational (age 12 to adulthood): abstract thought, imagination and deductive reasoning develops

DEVELOPMENT OF AN ILLNESS PERCEPTION BIBACE AND WALSH (1980) Illness concepts gradually develop by asking questions. Children aged 3– 13 years were asked questions about health and illness as follows: • ‘What is a cold? ’ – knowledge • ‘Were you ever sick? ’ – experience • ‘How does someone get a cold? ’ – attributions • ‘How does someone get better? ’ – recovery Themes of explanation can be attached to Piaget’s developmental stages.

ILLNESS CONCEPT IN SENSORIMOTOR AND PREOPERATIONAL STAGE CHILDREN Under-7 s generally explain illness on a ‘magical’ level – often based on association. Incomprehension: child gives irrelevant answers (e. g. ‘sun causes heart attacks’) or evades questions Phenomenonism: illness is usually a sign that the child has at some time associated with the illness, with little cause and effect (e. g. ‘a cold is when you sniff a lot’) Contagion: illness is from a person or object that is close by; or can be attributed to an activity that occurred before illness (e. g. ‘you get measles from people’. If asked ‘how? ’, ‘just by walking near them’)

ILLNESS CONCEPT IN CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE CHILDREN Explanations of illness at around 8– 11 years are more concrete and based on a causal sequence: Contamination: children learn illnesses can have multiple symptoms • recognise germs and their own behaviour can cause illness • (e. g. ‘get a cold if you take your jacket off outside, it gets into your body’) Internalisation: illness is within the body, but the process by which symptoms occur can be partially understood • (e. g. ‘cold caused from germs that I inhaled/swallowed’) At this stage, children can differentiate between body organs and understand simple illness information. They also identify that treatment and/or personal actions improve health.

ILLNESS CONCEPT IN FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE ADOLESCENTS Illness concepts at this stage are abstract – explanations based on interactions between the person and their environment: Physiological: A stage of physiological understanding is reached whereby illness can be defined in terms of specific bodily organs or functions. They begin to appreciate multiple physical causes (e. g. genes + pollution + behaviour). Psychophysiological: From 14+, many people understand body– mind interaction and accept the role of stress, worry, etc. in the exacerbation and cause of illness. – NB: Many adults may not achieve this level of understanding and continue with cognitively simplistic explanations.

ADULTHOOD 17/18+ While Piaget did not describe further cognitive developments in adulthood, new perspectives develop from experience, and are applied with a view to achieving life goals. Young adulthood: Less likely to adopt new health-risk behaviour and more likely to engage in protective behaviour (e. g. screening, exercise etc. ) for health reasons. Middle age: Identified as a period of doubts, anxiety and change; some triggered by • uncertainty of role when children leave home i. e. ‘empty nest’ syndrome • awareness of physical changes e. g. greying hair, weight gain, stiff joints.

AGEING AND HEALTH The ageing population has burgeoned, and living longer. The United Nations (2013) predict that those aged 65+ will double to 10% of the world population by 2025. Implications for health and social care clear given the epidemiology of illness: Increased prevalence of chronic disease Increased prevalence of disability and dependence • 85% of the elderly may have a chronic condition (Woods 2008)

SUCCESSFUL AGEING Ageing is not necessarily a negative experience: • Self-concept is relatively stable through ageing. • Successful ageing is possible and includes medical, psychological, socio-economic and broader social influences. Bowling and Iliffe (2006) Lay model of successful ageing (i. e. medical, psychological, social and socio-economic influences) strongest predictor of Quality of Life • 5 x more likely to rate Qo. L as ‘Good’ • Holistic models of health are ‘better’ • However, 98% of sample were white

SUBJECTIVE HEALTH STATUS Our perception of our own ‘health status’ is usually measured by single items (self-ratings of health; SRH) Deeg and Kriegsman (2003) • • 2000 Australian adults (aged 65+) 3 different measures of SRH on 7 occasions (1992– 2004) ‒ SRH ‒ Self vs. previous self ‒ Self vs. others of same age • All 3 ratings worsened over time ‒ Highlights the measures we employ can influence findings and interpretations

PSYCHOLOGY Psychology aims to describe, explain, predict, and where possible, intervene to control or modify behavioural and mental processes, from language, memory, attention and perception to emotions, social behaviour and health behaviour, to name just a few. The key to scientific methods employed by psychologists is the basic principle that the world may be known through observation = empiricism. • we observe • we define a problem • we collect data • we analyse data • we develop a theory • we test theory by return to data collection.

HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY Health psychology takes a biopsychosocial approach to health and illness. Its main goals (derived from Matarazzo’s definition, 1980) are to develop our understanding of biopsychosocial factors involved in: • the promotion and maintenance of health; • improving health-care systems and health policy; • the prevention and treatment of illness; • the causes of illness, e. g. vulnerability/risk factors.

CONTRASTING DISCIPLINES Psychosomatic Medicine: previously psychoanalytical – now addresses mixed psychological, social and biological explanations of illnesses; Behavioural Medicine: behavioural principles (e. g. operant conditioning) are employed with focus on rehab and treatment; Medical Psychology: generally assigned to profession rather than discipline. Use mechanistic medical model to treat/cure for ‘normality’; Medical Sociology: exemplifies close relationship between psychology and sociology, with health and illness considered in terms of social factors that may influence individuals; Clinical Psychology: concerned with mental health and the diagnosis and treatment of mental health problems (e. g. phobias, anxiety, eating disorders etc. ).

HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY APPROACHES (MARKS 2002) Clinical health psychology merges clinical psychology’s focus on assessment and treatment with a broader biopsychosocial approach; Public health psychology addresses issues such as immunisation, epidemics, and implications for health education and promotion; Critical health psychology arose from criticism that health psychology was too individualistic in focus, too concerned with individual aspects at the expense of social; Academic health psychology focuses on research, teaching and supervision conducted from academic base; Professional health psychology action research to facilitate the growth of healthy groups and healthy communities.

Nantai cash

Nantai cash Nantai 37

Nantai 37 Ncler

Ncler Health psychology definition ap psychology

Health psychology definition ap psychology Positive psychology ap psychology definition

Positive psychology ap psychology definition Psychology experiment

Psychology experiment Social psychology ap psychology

Social psychology ap psychology Explain methods of psychology

Explain methods of psychology Social psychology definition psychology

Social psychology definition psychology Psychology lecture for medical students

Psychology lecture for medical students Introduction to health psychology

Introduction to health psychology Physical disorders and health psychology

Physical disorders and health psychology Psychology, mental health and distress

Psychology, mental health and distress Mcq on stress in psychology

Mcq on stress in psychology Health psychology associates

Health psychology associates Enrich health and psychology

Enrich health and psychology Health psychology quiz

Health psychology quiz Toplumla sosyal hizmet nedir

Toplumla sosyal hizmet nedir Rol dağıtım tekniği nedir

Rol dağıtım tekniği nedir Ibretlik sözler

Ibretlik sözler Amprisizm

Amprisizm Sosyal psikoloji kuramları

Sosyal psikoloji kuramları Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek

Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek Sosyal hizmetin değer temeli

Sosyal hizmetin değer temeli Sosyal güvenlik teorisi ders notları

Sosyal güvenlik teorisi ders notları