NANTAI NVERSTES HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY ktisadi dari ve Sosyal

- Slides: 19

NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY İktisadi, İdari ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi iisbf. nisantasi. edu. tr NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ ©

LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of this chapter, you should have an understanding of: • cognitive-behavioural and mindfulness approaches to stress management • ways of intervening at a population or organisational level to reduce work stress • interventions of value in helping people to cope with the stress associated with a surgical operation

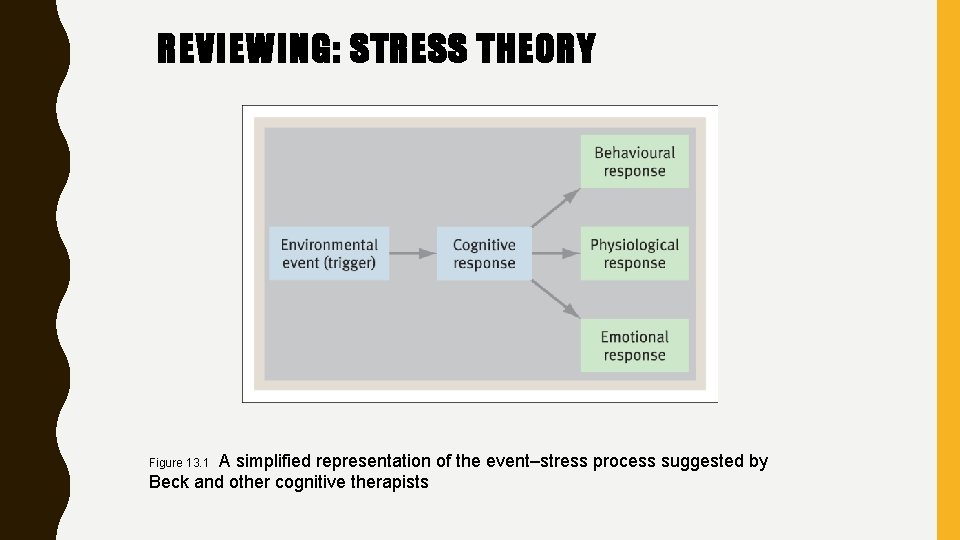

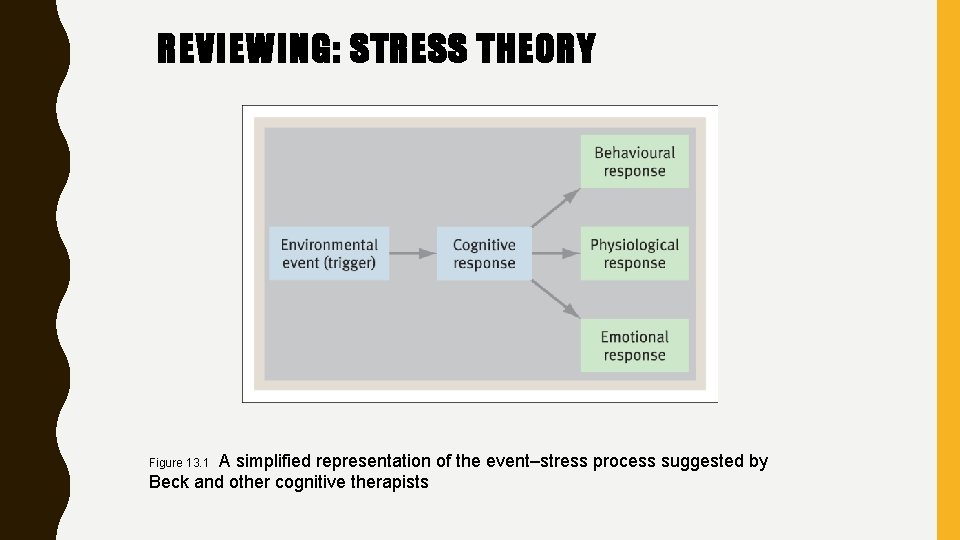

REVIEWING: STRESS THEORY A simplified representation of the event–stress process suggested by Beck and other cognitive therapists Figure 13. 1

THOUGHTS LEADING TO EMOTIONS Beck (1976) identified a number of automatic thoughts that lead to negative emotions, including: • Catastrophic thinking: considering an event as completely negative, and potentially disastrous: ‘That’s it - I’ve had a heart attack. I’m going to lose my job, and I won’t be able to afford to pay the rent. ’ • Over-generalisation: drawing a general (negative) conclusion on the basis of a single incident: ‘That’s it - my pain stopped me going to the cinema that’s something else I can’t do. ’ • Arbitrary inference: drawing a conclusion without sufficient evidence to support it: ‘The pain means I have a tumour. I just know it. ’ • Selective abstraction: focusing on a detail taken out of context: ‘OK, I know I was able to cope with going out, but my joints ached all the time, and I know that will stop me going out in future. ’

SCHEMATA IN TYPE A BEHAVIOUR Price’s (1988) schema underlying Type A behaviour: – low self-esteem; – a belief that one can gain the esteem of others only by continually proving oneself as an ‘achiever’ and a capable individual. Surface cognitions associated with Type A behaviour include: – Time-urgent thoughts: ‘Come on, we haven’t got all day. I’m going to be late! Why is he so slow? ’; – Hostile thoughts: ‘That person cuts me up deliberately! I’ll sort him out. Why is everyone else so incompetent. . . ’ Deeper (unconscious) schema include: – ‘I can’t say no to her or I will look incompetent and lose her respect. ’ – ‘People only respect me for what I do for them, not for who I am. ’

STRESS MANAGEMENT TRAINING Factors can be changed to reduce individual stress including: • Environmental events that trigger the stress response – or series of triggers to longer-term stress; • Inappropriate behavioural, physiological, or cognitive responses that occur in response to this event. Accordingly, • Triggers can be identified and edited via problem-solving strategies. Cognitive distortions can be identified and changed through a number of cognitive techniques, such as cognitive restructuring. • High levels of muscular tension and other signs of physiological arousal can be reduced through relaxation techniques. • ‘Stressed’ behaviour can be changed through consideration and rehearsal of alternative behavioural responses.

CHANGING TRIGGERS Problem-focused counselling involves three phases: 1. Problem exploration and clarification: what are the triggers to stress? 2. Goal setting: which stress triggers does the individual want to change? 3. Facilitating action: how do they set about changing these stress triggers? Egan (1998)

RELAXATION TRAINING The goal of relaxation is to enable one to relax as much as possible, particularly in stress events. Relaxation skills are best learned through three phases: 1. learning basic relaxation skills; 2. monitoring tension in daily life; 3. using relaxation at times of stress.

COGNITIVE INTERVENTIONS Two strategies for changing cognitions are frequently employed. Self-instruction training (Meichenbaum 1985): • targets surface cognitions; • involves interrupting the flow of stress-provoking thoughts; • replaces them with stress-reducing thoughts or positive ‘self-talk’; - reminders of techniques, i. e. ‘take it easy, relax, deep breathe’ - reassurance, i. e. ‘keep calm, you’ve dealt with this before’. Cognitive restructuring: • identifies and challenges the accuracy of stress-provoking thoughts; • considers them as hypotheses, not facts; • assesses their validity without bias; • asks key questions such as: - What evidence is there that supports or denies my assumption? - Are there any other ways I can think about this situation? - Could I be making a mistake in the way I am thinking?

STRESS INOCULATION TRAINING Various strands of cognitive therapy could be combined so that, when an individual is facing a stressor, they concentrate on: • checking that their behaviour is appropriate to the circumstances; • maintaining relaxation; • giving themselves appropriate self-talk. Meichenbaum (1985)

3 RD WAVE THERAPIES: MINDFULNESS-BASED INTERVENTIONS Bishop et al. (2004) proposed a two-component model of mindfulness: Self-regulation of attention: being fully aware of current experience – observing and attending to thoughts, feelings and sensation as they occur. Leads to being very alert and ‘alive’. An orientation towards one’s experiences in the present moment characterised by curiosity, openness and acceptance: lack of cognitive effort given to the elaboration on the meanings and associations of our various experiences allows the individual to focus more on their present experience.

MINDFULNESS+ Wells’ (2000) Self-Regulatory Executive Function model focuses on content of cognitions and processes associated with them. The goals of therapy include: – teaching individuals to develop more flexible coping strategies to use in stressful situations; – encouraging participants to engage in feared situations in a graduated process, using skills (i. e. mindfulness) to help them cope with difficult thoughts or emotions; – teaching individuals a ‘higher metacognitive mode’ which allows information processing so not to trigger high distress.

ACCEPTANCE AND COMMITMENT THERAPY (ACT) (HAYES ET AL. 2004) ACT uses acceptance, mindfulness, commitment and behaviour change processes to increase psychological flexibility, established through focus on five related core processes: – Acceptance: allowing oneself to be aware of thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations as they occur; – Cognitive defusion: seeing that thoughts are simply thoughts, feelings are feelings, memories are memories, sensations are sensations; – Contact with the present moment: 1) observe and notice present environment and in private experience (i. e. thoughts and emotions) 2) label and describe the present, without excessive judgement; – Values: relate to the motivation for change; – Committed action: developing strategies for achieving desired goals. Clients are then encouraged to define goals in specific areas and to progress towards them.

PREVENTING STRESS Differing stress management programmes are effective in reducing perceived stress and levels of stress hormone, cortisol (Hammerfald et al. 2006; Storch et al. 2007). Increasing evidence that mindfulness-based interventions can also reduce stress: Mindfulness was more effective in changing measures of wellbeing, perceived stress, and exhaustion than no-treatment control (Nyklicek and Kuijpers 2008). Mindfulness was most effective by achieving same benefits as CBT in well-being, perceived stress and depression, and performing better in mindfulness, energy and pain (Smith et al. 2008).

STRESS IN THE WORKPLACE Jones et al. (2003) • over half a million UK individuals reported experiencing workrelated stress that was making them ill, while nearly 1 in 5 thought their job was very or extremely stressful; • work-related stress, depression or anxiety accounts for an estimated 13. 5 million lost working days per year in UK; • levels of work stress are rising; • teachers and nurses have particularly high prevalence of workrelated stress.

MANAGING WORK STRESS An example of how to reduce stress in a group of hospitals: – identify causes of stress in the working environment; – identify solutions to this stress from those most involved; – develop a process of change to address the issues raised. Problems raised included major systemic problems such as: – a poor computer network system; – poor hospital bus provision (not fitting with shift times); – very poor parking facilities; – inadequate crèche facilities; – organisation of wards in hospital that compete rather than cooperate; – working culture where people who did not work significant overtime were punished.

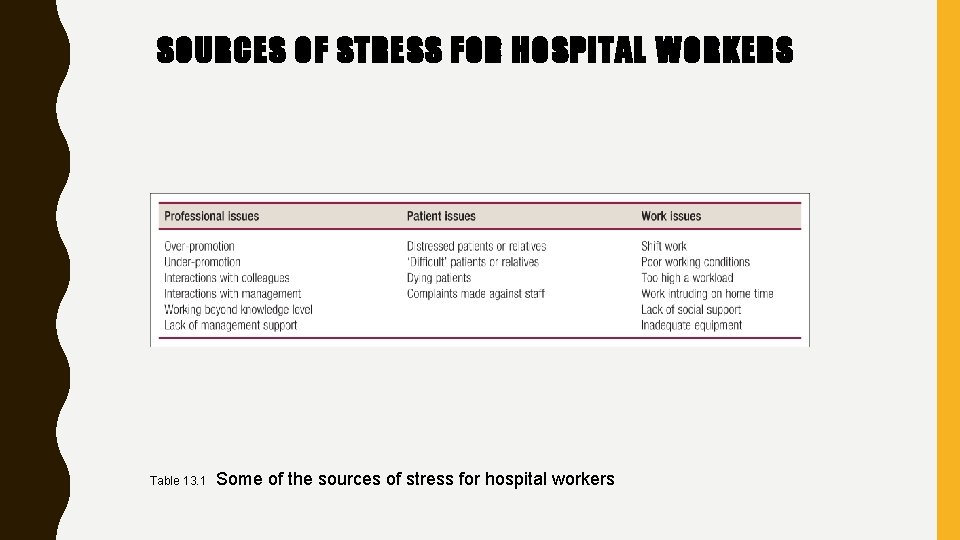

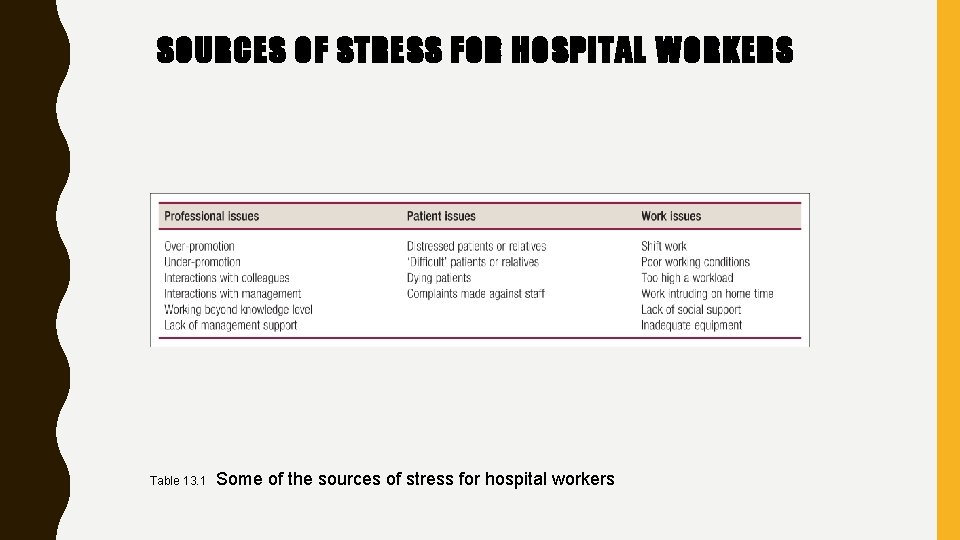

SOURCES OF STRESS FOR HOSPITAL WORKERS Table 13. 1 Some of the sources of stress for hospital workers

DO ORGANISATIONAL INTERVENTIONS WORK? Montano, Hoven and Siegrist (2014): • Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve physical and mental health of workers (39 studies). • 19 studies reported significant benefits of the interventions. • Reasons for failure were often organisational constraints on change (e. g. lack of enthusiasm, failure in establishing the intervention, organisational restructuring etc). Dababneh et al. (2001): • Introduced short rest breaks on productivity and well-being in a meat processing factory: adding four 9 -minute break schedules distributed evenly through the day or twelve 3 -minute breaks. • Neither lowered production levels. Both resulted in significant reductions in psychological discomfort.

MINIMISING STRESS IN HOSPITAL SETTINGS: PREOPERATIONAL PREPARATION Reducing anxiety by minimising the fear of the unknown. Information is provided in two ways: 1. Procedural information: telling patients about the events that will occur before and after surgery; having a premedication injection, walking in the recovery room and having a drip in their arm, etc. 2. Sensory information: telling patients what they may feel before and after surgery i. e. it is normal to feel some pain following surgery or feel confused when they come round from the anaesthetic, etc. (Johnston and Vogele 1993)

Nantai cash

Nantai cash Nantai 37

Nantai 37 Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik

Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik Health psychology definition ap psychology

Health psychology definition ap psychology Positive psychology ap psychology definition

Positive psychology ap psychology definition Group thinking psychology

Group thinking psychology Social psychology ap psychology

Social psychology ap psychology Introspection method in psychology

Introspection method in psychology Social psychology is the scientific study of

Social psychology is the scientific study of Aim of health psychology

Aim of health psychology Introduction to health psychology

Introduction to health psychology Physical disorders and health psychology

Physical disorders and health psychology Psychology, mental health and distress

Psychology, mental health and distress Stress management mcqs

Stress management mcqs Health psychology associates

Health psychology associates Enrich health and psychology

Enrich health and psychology Health psychology quiz

Health psychology quiz Saptama nedr

Saptama nedr Rol dağıtım tekniği

Rol dağıtım tekniği Ibretlik sözler

Ibretlik sözler