NANTAI NVERSTES HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY ktisadi dari ve Sosyal

- Slides: 25

NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY İktisadi, İdari ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi iisbf. nisantasi. edu. tr NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ ©

CHAPTER 5 EXPLAINING HEALTH BEHAVIOUR

Learning Outcomes By the end of this chapter, you should understand be able to describe: • how demographic, social, cognitive and motivational factors influence the uptake of health or risk behaviour • key psychosocial models of health behaviour and health behaviour change • how ‘continuum’ or ‘static’ models differ from ‘stage’ models in terms of how they consider behaviour change processes • the research evidence that supports or refutes the models in terms of which factors are predictive of health behaviour and change

Explaining Health Behaviour: Demographic Influences • Social class: those with lower socio-economic status, drink and smoke more, exercise less, and have poorer diets; • Age: Behaviours either positively or negatively associated with health tend to commence in childhood or adolescence; • Gender: Males tend to engage in behaviours that project masculinity e. g. drink more, but paradoxically, also engage in more physical activity to project fitness and strength; • Ethnicity: For Muslim males, religion exerted stronger influences on their behaviour than the need to look ‘masculine’. Differences in illness beliefs and attitudes may in part explain the above.

EXPLAINING HEALTH BEHAVIOUR: PERSONALITY Mc. Crae and Costa’s (1987, 1990) Five Factor Model The ‘Big 5’ personality traits and their associations with health behaviours: • Neuroticism (N): associated with negative health behaviours, e. g. neophobia. Conversely, greater health care use • Extroversion (E): associated with increased risk-taking • Openness (O): associated with willingness to try new healthier foods; yet increased risk-taking • Agreeableness (A): associated with less risk-taking • Conscientiousness (C): associated with health-protective behaviour, i. e. reported self-motivations to safe sex Deci and Ryan (2000) Self-determination theory • Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation for behaviour ‒ (i. e. personal satisfaction vs. peer approval)

EXPLAINING HEALTH BEHAVIOUR: PERSONALITY (CONT. ) Locus of Control (Rotter 1966); Health Locus of Control (Wallston et al. 1978). Health Lo. C dimensions: • Internal: individuals as the prime determinant of their health state. Internal beliefs associate with health-protective behaviour and selfefficacy. • External/chance: external forces such as luck, fate or chance determine an individual’s health state, rather than their own behaviour. • Powerful others: health state to be determined by the actions of powerful others such as health and medical professionals. NB: These dimensions are only relevant if an individual values their health. Mixed empirical evidence as to predictive utility of control belief and health protection.

EXPLAINING HEALTH BEHAVIOUR – GOALS AND SELF-REGULATION Social cognition theory assumes that behaviour is motivated by outcome expectancies and short- and long-term goals. Goals: • • • focus our attention; directs our efforts; encourage persistence even when faced with set-backs. Self-regulatory processes (cognitive, emotional and behavioural) help us achieve our goals. Attentional control is also required, so that we can focus on activities necessary to achieve goals, and can avoid being distracted by competing goals, demands, or negative thoughts or emotions.

HUMANS ARE INCONSISTENT • Different health behaviours are controlled by different external factors (i. e. smoking is discouraged yet more readily available than exercise and leisure facilities). • Attitudes towards health behaviour vary within and between individuals. • Within individuals, health behaviours may be motivated by different expectations. • Individuals differ in their goals and motivations regarding behaviour (i. e. teens diet to look good, elders diet to improve health). • Motivating factors may change over one’s lifespan. • Triggers and barriers to behaviour are influenced by

SOCIOCOGNITIVE MODELS OF HEALTH BEHAVIOUR – ATTITUDES Attitudes are relatively enduring and generalisable and made up of three components: • Cognitive: thoughts and beliefs about the attitude-object – e. g. cigarette smoking is a good way to relieve stress; cigarette smoking is a sign of weakness. • Emotional: feelings towards the attitude-object – e. g. Cigarette smoking is disgusting/pleasurable. • Behavioural (or intentional): intended action towards the attitudeobject – e. g. I am not going to smoke. NB: Direct association between these 3 components and behaviour is not as straightforward as you might think!

SOCIOCOGNITIVE MODELS OF HEALTH BEHAVIOUR (CONT. ) Risk Perceptions and Unrealistic Optimism Weinstein (1987) identified four factors that are associated with unrealistic optimism: • a lack of personal experience with the behaviour or problem; • a belief that their individual actions can prevent the problem; • the belief that if the problem is unlikely to emerge if it hasn’t done so already; e. g. ‘I have smoked for years and my health is fine, so why would it change now? ’; • the belief that the problem is rare; e. g. ‘Cancer is rare compared to smoking, so it is pretty unlikely I’ll develop it’.

SOCIOCOGNITIVE MODELS OF HEALTH BEHAVIOUR – SELF-EFFICACY Bandura (1986) “beliefs about whether one can produce certain actions” e. g. Believing that a future action is within your capabilities is likely to generate other cognitive and emotional activity, such as setting high personal goals, positive outcome expectancies and reduced anxiety about future. Self-efficacy beliefs often emerge as an important strong predictor of individual health behaviour (Morrison et al. 2015) and behaviour change (Eccles et al. 2014).

THE HEALTH BELIEF MODEL Figure 5. 1 The health belief model (original, plus additions in italics)

THE HEALTH BELIEF MODEL (CONT. ) Rosenstock 1974; Becker et al. 1977; Strecher et al. 1997. Perception of threat: • I believe that coronary heart disease is a serious illness contributed to being overweight: perceived severity. • I believe that I am overweight: perceived susceptibility. Behavioural evaluation: • • If I lose weight, my health will improve: perceived benefits (of change). Changing my cooking and dietary habits when I also have a family to feed will be difficult, and possibly more expensive: perceived barriers (to change). Cues to action (added in 1975, Becker and Maiman): • • That recent TV programme on the health risks of obesity worried me (external). I regularly feel breathless on exertion, maybe I should lose some weight (internal). Health motivation (added in 1977, Becker et al. ): • It is important to me to maintain my health.

THE HEALTH BELIEF MODEL (CONT. ) Applications: • HBM is widely used for predicting breast self-examination; • Perceived benefits of self-examination and few barriers to its performance are most consistently and most highly correlated; • Other factors are predictive of BSE; perceived seriousness of breast cancer, perceived susceptibility and being motivated towards health (e. g. actively seeking health information). Limitations: • HBM components are more relevant in predicting health preventive behaviour, rather than reducing risk-behaviour. • Overestimates the role of ‘threat’ – e. g. overuse of fear arousal can be counter-productive in behaviour change; • Static model – does not allow for staged or dynamic processes such as changing or oscillating beliefs over time.

THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR (AJZEN 1985; 1991) Figure 5. 2 The theory of planned behaviour

THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR Previously the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen and Fishbein 1970; Fishbein and Ajzen 1985) The TPB assumes that: • individuals behave in a goal-directed manner; • the implications of actions (outcome expectancies) are weighed up in a rational manner. The TPB aims to explore and develop the psychological processes involved in making a link between attitude and behaviour, by including: • social influences on behaviour; • beliefs in perceived behavioural control; • and the necessity of intention formation.

THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR (CONT. ) Applications: • eating breakfast (Wong and Mullan 2009) • breastfeeding intentions (Giles et al. 2014) • chlamydia testing intentions (Booth et al. 2014) • medication adherence (Morrison et al. 2015) • mothers behaviours to encourage an active versus a sedentary lifestyle in their children (Hamilton et al. 2013) Limitations: • TPB does not acknowledge likely transactions between predictor variables (attitudes and subjective norms) and outcome variables, either intention or behaviour. • Assumes that the same factors and processes predict the initiation of a behaviour and the maintenance of that behaviour/change.

POTENTIAL ADDITIONS TO THE TPB? ‘Moral norms’ – it has been recognised that some intentions and behaviours may be partially motivated by moral norms, not just social norms (e. g. drink driving; Evans and Norman 2002) Anticipatory regret – anticipating that regret will result if a certain behavioural decision is made/not made which influences both future behavioural intentions and behaviour (e. g. not using a condom; Richard et al. 1996) Self-identity – how one perceives and labels oneself may influence intention above and beyond the effect of core TPB variables (e. g. self as being ‘green’ and subsequent dietary change; Sparks and Shepherd 1992) Implementation intention (II) – forming an II is thought to be part of the process involved in turning an intention into action

IMPLEMENTATION INTENTION (II) People may not always translate their intentions into action as they have not made adequate plans as to how, when and where they will implement their intention i. e. : • Goal intention: ‘I intend to go on a diet’ (motivational, TPB); • Implementation intention: ‘I intend to go on a diet on Monday after my party weekend’ (planning, not TPB). Applications: • Significant higher rate of BSE in those that formed II (Orbell et al. 1997) • Long-term effects – forming II to take vitamin pills persisted over 3 weeks (Sheeran and Orbell 1999)

STAGE MODELS OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE According to Weinstein (Weinstein et al. 1998; Weinstein and Sandman 2002) a stage theory has four properties: A classification system to define stages: • Stage classifications are theoretical constructs and although a prototype is defined for each stage, few people will perfectly match this ideal. Ordering of stages: • People must pass through all the stages to reach the end point of action or maintenance, but progression to the endpoint is neither inevitable nor irreversible. Common barriers to change facing people within the same stage: • This idea would be helpful in encouraging progression through the stages. Different barriers to change facing people in different stages: • If the factors producing movement to the next stage were the same, regardless of the stage (e. g. self-efficacy), the same intervention could be used for all, and the stages would be redundant.

THE TRANSTHEORETICAL MODEL (PROCHASKA AND DI CLEMENTE 1984) Pre-contemplation: no current thoughts of dieting, no intention of changing diet within next 6 months, may not consider that they have a weight problem. Contemplation: e. g. ‘I think I need to lose a bit of weight, but not quite yet’ reflects awareness and consideration to do so. Generally plan to change within next 6 months. Preparation: ready to change and set goals such as planning a start date for diet (within 3 months); includes thoughts and action, by specific plans for change. Action: e. g. person starts eating fruit instead of biscuits – overt behaviour change. Maintenance: keeps up with the dietary change, resists temptation. The above stages are the 5 most commonly referred to, there also other stages: Termination: behaviour change has maintained for adequate time and feels no temptation to lapse, believe in their total self-efficacy to maintain the change. Relapse: di Clemente and Velicer (1997) acknowledged that relapse (where a

TARGETS OF INTERVENTION (TTM) Pre-contemplation stage: individuals are likely to use denial, report lower selfefficacy (to change) and more barriers to change. Contemplation stage: likely to seek information; report reduced barriers to change and increased benefits; yet still underestimate their susceptibility to the health threat concerned. Preparation stage: start goal-setting, making concrete plans (see also implementation intentions) and small behaviour changes (i. e. joining a gym). Some may set unrealistic goals or underestimate their own ability. Motivation and self-efficacy are crucial if action is to be elicited. Action stage: realistic goal setting is crucial. Social support provides reinforcement for changed behaviour and to maintain lifestyle change. Many individuals, for example, up to 80% of smokers who quit, will not succeed in maintaining behavioural change and will relapse or ‘recycle’ back to contemplating a future attempt to change.

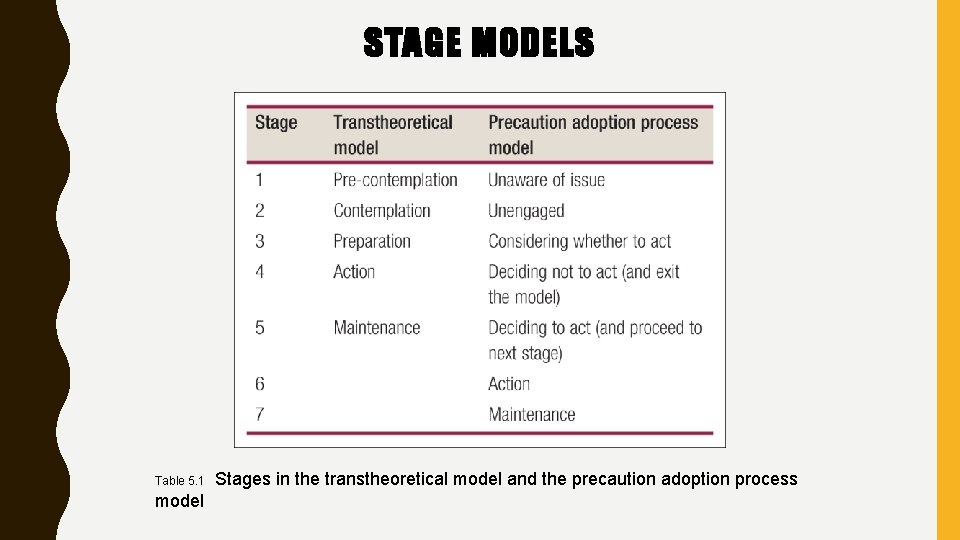

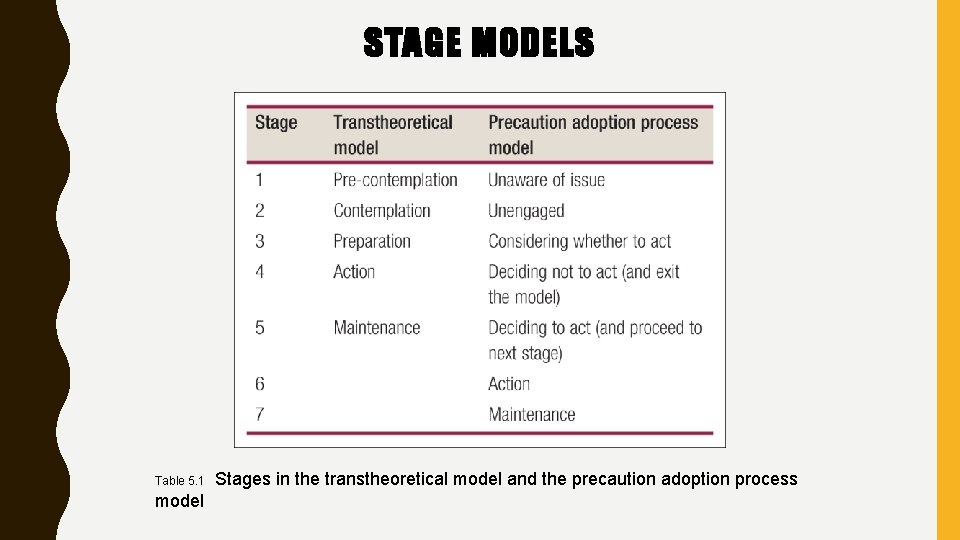

STAGE MODELS Table 5. 1 model Stages in the transtheoretical model and the precaution adoption process

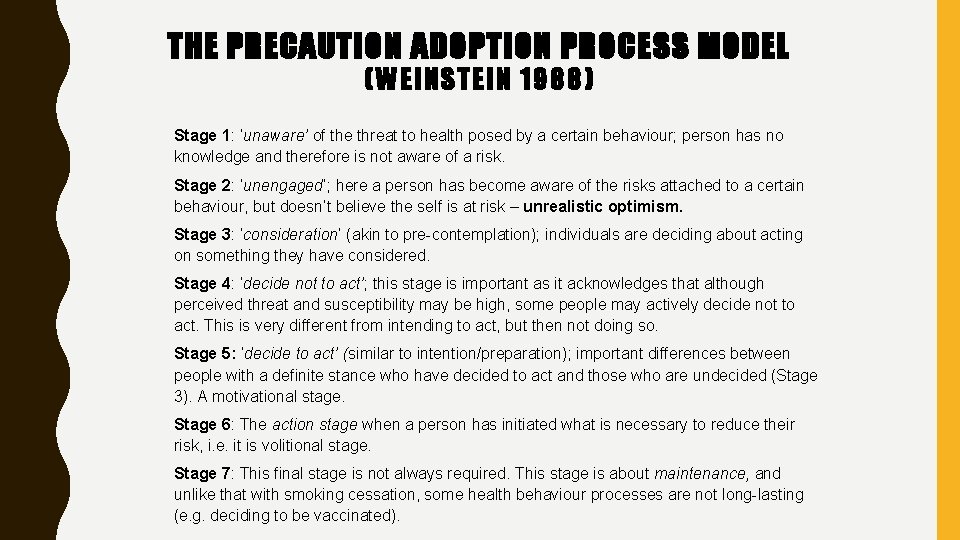

THE PRECAUTION ADOPTION PROCESS MODEL (WEINSTEIN 1988) Stage 1: ‘unaware’ of the threat to health posed by a certain behaviour; person has no knowledge and therefore is not aware of a risk. Stage 2: ‘unengaged’; here a person has become aware of the risks attached to a certain behaviour, but doesn’t believe the self is at risk – unrealistic optimism. Stage 3: ‘consideration’ (akin to pre-contemplation); individuals are deciding about acting on something they have considered. Stage 4: ‘decide not to act’; this stage is important as it acknowledges that although perceived threat and susceptibility may be high, some people may actively decide not to act. This is very different from intending to act, but then not doing so. Stage 5: ‘decide to act’ (similar to intention/preparation); important differences between people with a definite stance who have decided to act and those who are undecided (Stage 3). A motivational stage. Stage 6: The action stage when a person has initiated what is necessary to reduce their risk, i. e. it is volitional stage. Stage 7: This final stage is not always required. This stage is about maintenance, and unlike that with smoking cessation, some health behaviour processes are not long-lasting (e. g. deciding to be vaccinated).

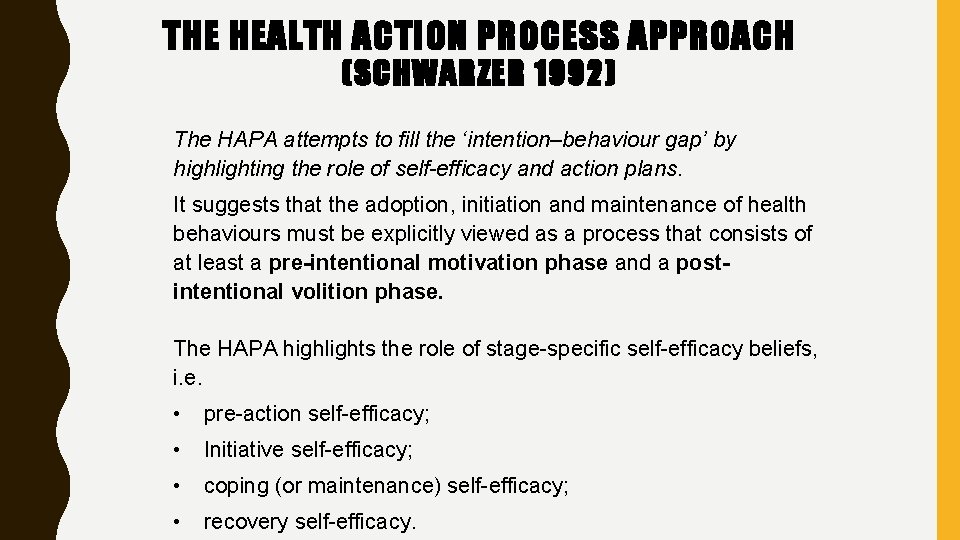

THE HEALTH ACTION PROCESS APPROACH (SCHWARZER 1992) The HAPA attempts to fill the ‘intention–behaviour gap’ by highlighting the role of self-efficacy and action plans. It suggests that the adoption, initiation and maintenance of health behaviours must be explicitly viewed as a process that consists of at least a pre-intentional motivation phase and a postintentional volition phase. The HAPA highlights the role of stage-specific self-efficacy beliefs, i. e. • pre-action self-efficacy; • Initiative self-efficacy; • coping (or maintenance) self-efficacy; • recovery self-efficacy.

Nantai cash

Nantai cash Nantai 37

Nantai 37 Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik nedir

Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik nedir Health psychology definition ap psychology

Health psychology definition ap psychology Positive psychology ap psychology definition

Positive psychology ap psychology definition Mere exposure effect psychology

Mere exposure effect psychology Fundamental attribution error ap psychology

Fundamental attribution error ap psychology Scope of psychology

Scope of psychology Social psychology definition psychology

Social psychology definition psychology Aims of health psychology

Aims of health psychology Introduction to health psychology

Introduction to health psychology Physical disorders and health psychology

Physical disorders and health psychology Psychology, mental health and distress

Psychology, mental health and distress Mcq on stress in psychology

Mcq on stress in psychology Health psychology associates

Health psychology associates Enrich health and psychology

Enrich health and psychology Health psychology quiz

Health psychology quiz Toplumla sosyal hizmet

Toplumla sosyal hizmet Sosyal uzaklık ölçeği

Sosyal uzaklık ölçeği Ibretlik sözler

Ibretlik sözler Amprisizm

Amprisizm Sosyal psikoloji araştırma konuları

Sosyal psikoloji araştırma konuları Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek

Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek Sosyal hizmetin temelleri

Sosyal hizmetin temelleri Sosyal güvenlik teorisi ders notları

Sosyal güvenlik teorisi ders notları Uyma davranışını etkileyen ortamsal faktörler

Uyma davranışını etkileyen ortamsal faktörler