NANTAI NVERSTES HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY ktisadi dari ve Sosyal

- Slides: 22

NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY İktisadi, İdari ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi iisbf. nisantasi. edu. tr NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ ©

ILLNESS OR DISEASE? Disease: something of the organ, cell or tissue that suggests a physical disorder or underlying pathology. Illness: ‘what the patient feels when he goes to the doctor’ Cassell (1976); experience of not feeling right. How do you know when you are getting ill? Three stages of response: • perceiving symptoms; • interpreting symptoms as illness; • planning and taking action.

CHAPTER 10 THE CONSULTATION AND BEYOND

LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of the chapter, you should have an understanding of: • the process of the medical consultation • the movement towards ‘shared decision making’ and the issues it creates • factors that contribute to effective and ineffective consultations with health professionals • issues related to ‘breaking bad news’ and medical decision making • factors that influence adherence to medical treatments and behavioural change programmes • interventions to improve adherence to medication and behavioural regimens

THE MEDICAL CONSULTATION Consultations typically include five phases: 1. The doctor establishes a relationship with the patient. 2. The doctor attempts to discover the reason for the patient's attendance. 3. The doctor conducts a verbal and/or physical examination. 4. The doctor, or the doctor and the patient, or the patient (in that order of probability) considers the condition. 5. The doctor, and occasionally the patient, considers further treatment or further investigation. Byrne and Long (1976)

‘GOOD’ MEDICAL CONSULTATION Six factors considered to be important to ‘good’ medical consultation by a variety of informants including GPs, hospital staff and lay people: 1. having a good knowledge of research or medical information and being able to communicate this to the patient; 2. achieving a good relationship with the patient; 3. establishing the nature of the patient’s medical problem; 4. gaining an understanding of the patient’s understanding of their problem and its ramifications; 5. engaging the patient in any decision-making process – treatment choices, for example, are discussed with the patient; 6. managing time so that the consultation does not appear rushed.

WHO HAS THE POWER? The Professional-Centred Approach • The health professional keeps control over the interview. • They ask questions in order to gain information. ‒ These are direct, closed (allow yes/no answers), and refer to medical or other relevant facts. • The health professional makes the decision. • The patient passively accepts this decision.

WHO HAS THE POWER? (CONT. ) The Patient-Centred Approach • The professional identifies and works with the patient’s agenda as well as their own. • The health professional actively listens to the patient and responds appropriately. • Communication is characterised by the professional encouraging patient engagement in their ideas about what is wrong with them and how their condition may be treated. • The patient is an active participant in the process.

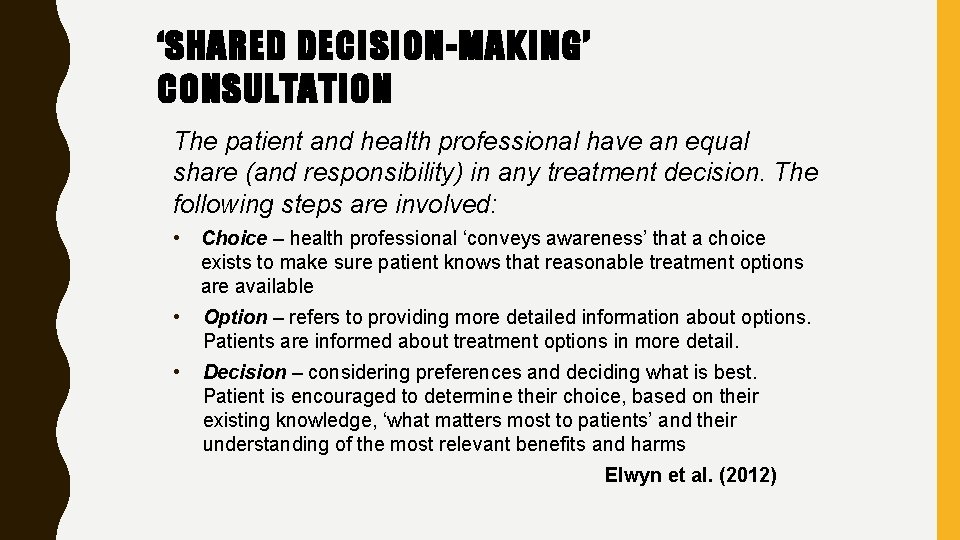

‘SHARED DECISION-MAKING’ CONSULTATION The patient and health professional have an equal share (and responsibility) in any treatment decision. The following steps are involved: • Choice – health professional ‘conveys awareness’ that a choice exists to make sure patient knows that reasonable treatment options are available • Option – refers to providing more detailed information about options. Patients are informed about treatment options in more detail. • Decision – considering preferences and deciding what is best. Patient is encouraged to determine their choice, based on their existing knowledge, ‘what matters most to patients’ and their understanding of the most relevant benefits and harms Elwyn et al. (2012)

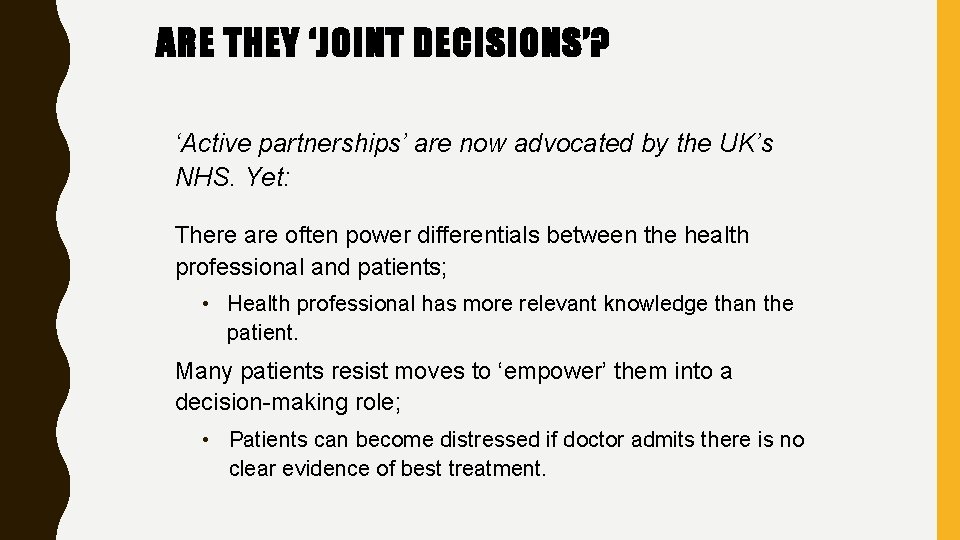

ARE THEY ‘JOINT DECISIONS’? ‘Active partnerships’ are now advocated by the UK’s NHS. Yet: There are often power differentials between the health professional and patients; • Health professional has more relevant knowledge than the patient. Many patients resist moves to ‘empower’ them into a decision-making role; • Patients can become distressed if doctor admits there is no clear evidence of best treatment.

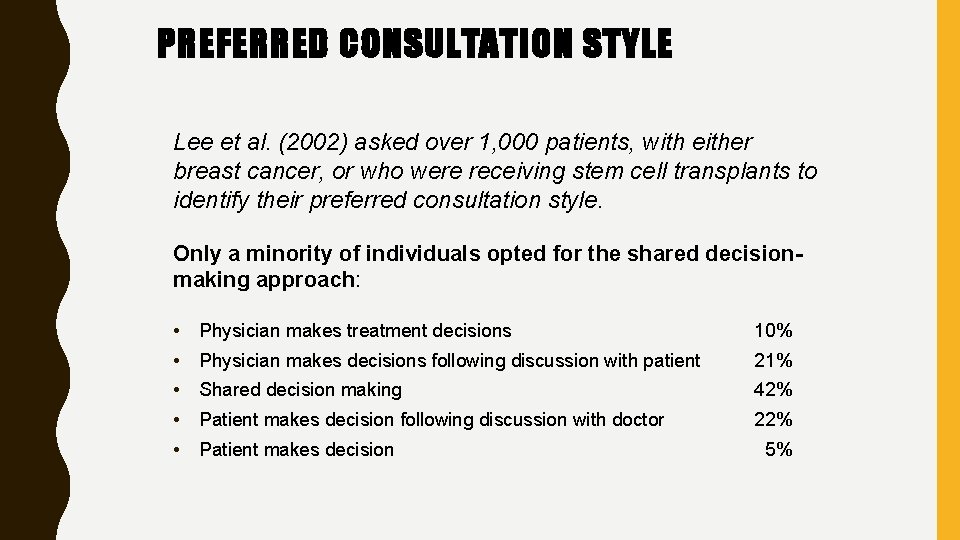

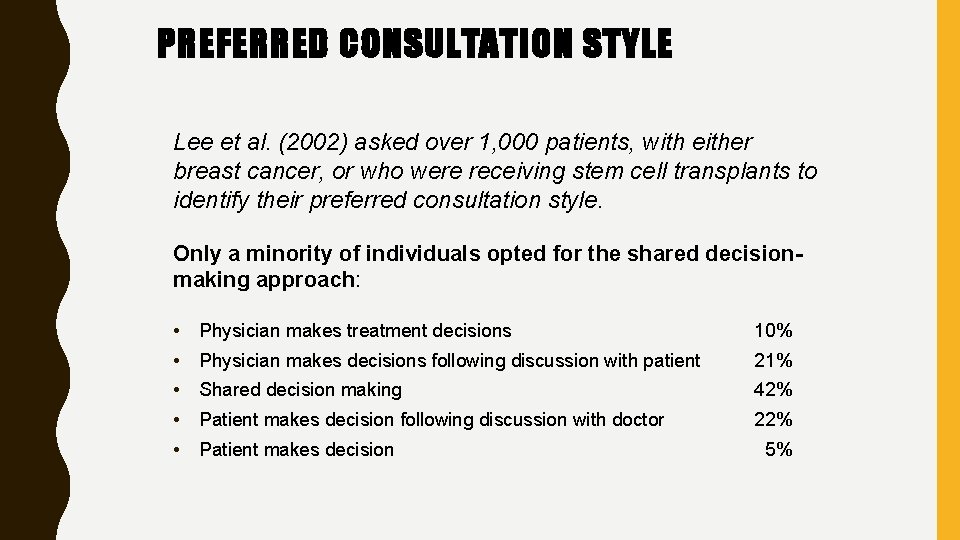

PREFERRED CONSULTATION STYLE Lee et al. (2002) asked over 1, 000 patients, with either breast cancer, or who were receiving stem cell transplants to identify their preferred consultation style. Only a minority of individuals opted for the shared decisionmaking approach: • Physician makes treatment decisions 10% • Physician makes decisions following discussion with patient 21% • Shared decision making 42% • Patient makes decision following discussion with doctor 22% • Patient makes decision 5%

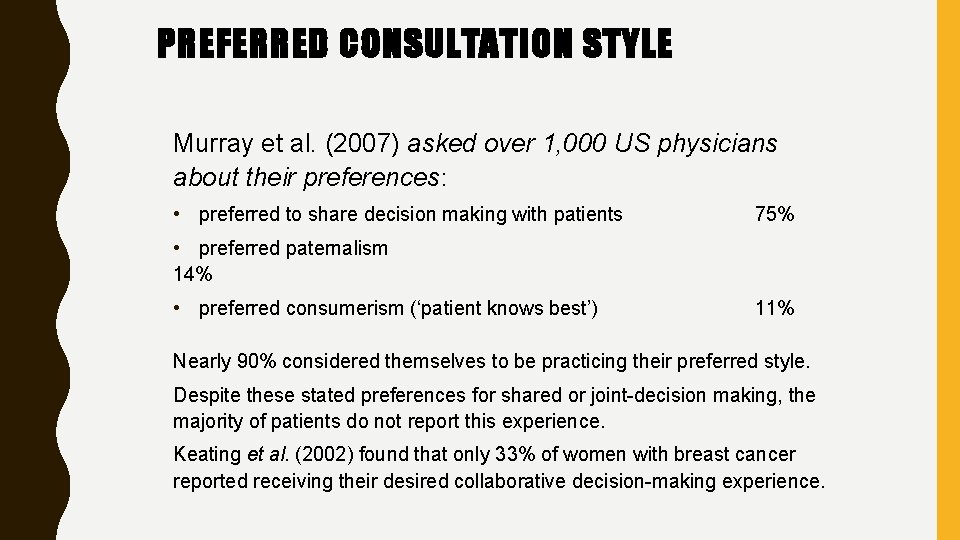

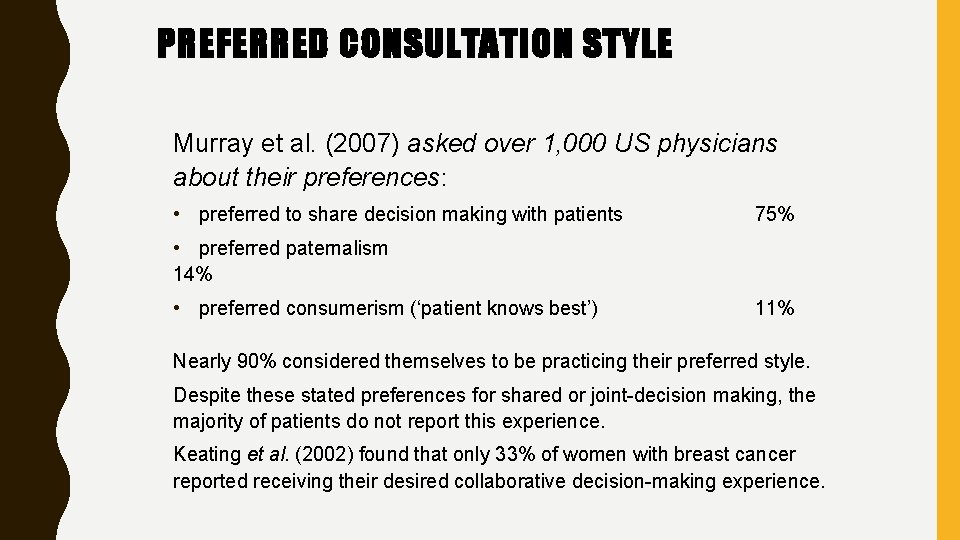

PREFERRED CONSULTATION STYLE Murray et al. (2007) asked over 1, 000 US physicians about their preferences: • preferred to share decision making with patients 75% • preferred paternalism 14% • preferred consumerism (‘patient knows best’) 11% Nearly 90% considered themselves to be practicing their preferred style. Despite these stated preferences for shared or joint-decision making, the majority of patients do not report this experience. Keating et al. (2002) found that only 33% of women with breast cancer reported receiving their desired collaborative decision-making experience.

INFLUENCING THE CONSULTATION: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL FACTORS Health professional behaviour Patients’ ratings of the doctor’s understanding of their feelings and the quality of their contact with the doctor are as important as their confidence in the doctor’s ability to cope with their illness, and distress (Zachariae et al. 2003). The type of health professional Nurses are generally seen as more nurturing, easier to talk to and better listeners than doctors (e. g. Nichols 2003). Gender of the health professional Patients may speak to female physicians more than male physicians, report more medical and personal information. Patients are more likely to report being treated disrespectfully by doctors of opposite gender (Beran et al. 2007).

INFLUENCING THE CONSULTATION: ADDITIONAL FACTORS Culture and language In the UK, South Asians fluent in English have shortest consultations; South Asians not fluent in English had the longest (Neal et al. 2006). In contrast, immigrant patients receive briefer consultations in the Netherlands. The way information is given A positive spin, may make the patient more likely to engage in risky health -care options than when it is given in a more negative manner (Berenbaum and Latimer-Cheung 2014). The patient’s contribution High levels of anxiety or distress during the interview and a lack of familiarity with the information discussed may minimise the patients’ level of engagement.

BREAKING ‘BAD NEWS’ Baile et al. (2000) suggested a six stage SPIKES model for the process: • • • SETTING UP the interview assessing the patient’s PERCEPTION obtaining the patient’s INVITATION giving KNOWLEDGE and information to the patient addressing the patient’s EMOTIONS with empathy STRATEGY and SUMMARY NB: Many senior doctors receive no formal training on delivering bad news and as such is stressful for both patient and doctor.

‘BAD NEWS’ STRESS The timescale of stress experienced by health-care professionals and patients in relation to the bad news interview Figure 10. 1 Source: adapted from Ptacek and Eberhardt (1996).

MEDICAL DECISION MAKING Given the importance of medical decisions, it is important to determine how they are achieved. Elstein and Schwarz (2002) identified a number of ways that doctors arrive at a diagnosis: • Hypothesis testing – the ‘gold star’ level of decision making. Involves a logical sequencing of establishing and testing hypotheses about the nature of the diagnosis. They are established, tested, and when they fail, are replaced by further hypotheses until a final ‘correct’ hypothesis is established. • Pattern recognition – compares patterns of symptoms with disease prototypes. Perhaps a good way of reaching easy diagnoses, with the hypothesis testing approach being utilised for more complex decisions. • Opinion revision or ‘heuristics and biases’ – perhaps the least reliable approach to making diagnoses – involves making decisions based on partial evidence as a result of using rules of thumb or heuristics.

DIAGNOSIS HEURISTICS A key problem with the use of heuristics is that they limit thinking through the full diagnostic possibilities, and may be biased by a number of factors (Marewski and Gigerenzer 2012) including: Availability – diseases that receive media attention or doctor’s knowledge of previous diagnoses given by colleagues can lead to diseases being diagnosed in error. Representativeness – comparing a patient’s symptoms to symptom prototypes of different conditions. The closer to prototype, the more likely the diagnosis. Errors can be made here. The potential ‘pay off’ of differing diagnoses – when unclear, the assigned diagnosis may be the one that carries least cost and most benefit for the individual.

TAKE THE TABLETS A wide range of other factors have also been found to predict poor adherence to medication (e. g. Kreuger, Berger and Felkey 2005): • Social factors: ‒ including low levels of education, unemployment, and concomitant drug use and low levels of social support; • Psychological factors: ‒ including high levels of anxiety and depression, use of emotion-focused coping strategies, such as denial, a belief that continued use of a drug will reduce its effectiveness; • Treatment factors: ‒ including misunderstandings regarding treatment, complexity of the treatment regimen, high numbers of side-effects, little obvious benefit from taking medication, poor communication and relationship between patient and health-care provider.

. . . CONSULTATION FACTORS IN IMPROVING ADHERENCE. . . Chances of an individual taking medication can be increased by a few strategies within the consultation. • Achieving concordance ‒ both patient and prescriber have discussed various treatment options and agreed to follow one treatment regimen. Shared-decision making and good communication enhance this process. • Maximising understanding ‒ of the condition and its treatment - problems arise if the health professional ‘leads’ the consultation, and patient does not ask questions to meet their information needs. • Maximising memory ‒ for example, the most important information should be given early or late in the flow of information to maximise primacy and recency effects, and its importance should be emphasised.

. . . KEEP TAKING THE TABLETS The most effective interventions to maximise adherence in chronic disease were generally complex and involved combinations of: • convenient timing of drug taking; • relevant information; • reminders to take medications; • self-monitoring (i. e. noting down when and where medication is taken); • reinforcement of appropriate use of medication; • family therapy. Mc. Donald et al. (2002)

REASONS FOR NON-ADHERENCE Adherence to behavioural programmes is also far from maximal. The key theoretical variables associated with adherence to behavioural programmes are: • • • confidence in the ability to exercise; intentions to exercise; perceived control over exercise; belief in the benefits of previous physical activity; perceived barriers to exercise; action planning. Petter et al. (2009)

Nantai cash

Nantai cash Nantai 37

Nantai 37 Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik

Sosyal statik ve sosyal dinamik Health psychology definition ap psychology

Health psychology definition ap psychology Positive psychology ap psychology definition

Positive psychology ap psychology definition Group polarization example

Group polarization example Social psychology ap psychology

Social psychology ap psychology Introspection method of psychology

Introspection method of psychology Social psychology definition psychology

Social psychology definition psychology Psychology lecture for medical students

Psychology lecture for medical students Health psychology definition

Health psychology definition Physical disorders and health psychology

Physical disorders and health psychology Psychology, mental health and distress

Psychology, mental health and distress Stress and coping mcqs

Stress and coping mcqs Health psychology associates

Health psychology associates Enrich health and psychology

Enrich health and psychology Health psychology quiz

Health psychology quiz Toplumla sosyal hizmet nedir

Toplumla sosyal hizmet nedir Sosyal uzaklık ölçeği

Sosyal uzaklık ölçeği Ibretlik sözler

Ibretlik sözler Rasyonalizm nedir

Rasyonalizm nedir Sosyal psikoloji araştırma yöntemleri

Sosyal psikoloji araştırma yöntemleri Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek

Sosyal hizmete muhtaç hastaya psikolojik destek